In this chapter we will step away from the basics of IDA and dive straight into applying our knowledge. This is a good starting point for the average computer or security professional with a general knowledge of security, assembly basics and programming. We will begin by figuring out exactly what our first example binary does, and then move to applying this knowledge in common practices within the security industry. Specifically, we’ll see if we can find the password it’s asking for when it first starts and then leverage this knowledge in order to find vulnerability within the binary. Applying these two approaches, we’ll finally be able to understand the steps needed to actually exploit the application.

The example code and binaries we will be using for this chapter are available for download from the Syngress website. The download file is called StaticPasswordOverflow.zip.

The first step in reversing any binary on the planet is determining exactly what it is doing and how it is doing it. Let’s jump into the immediate task of following the instructions of our application step by step, and take notes on the general operations within the binary. To begin, let’s go straight ahead into the first useful chunk of code. Although it’s personal preference, I prefer using a notepad or notebook of some sort so I can keep my thoughts as I move along, write down addresses, and generally keep track of everything. You never know when you might need a note from the beginning of your reversing, and typing numbers has, for me, always been much slower than writing them down. Plus, it’s much easier to draw pictures on paper!

.text:00401270 ; int __cdecl main(int argc,const char **argv,const char *envp) .text:00401270 Dst = byte ptr -80h .text:00401270 argc = dword ptr 8 .text:00401270 argv = dword ptr 0Ch .text:00401270 envp = dword ptr 10h .text:00401270 push ebp .text:00401271 mov ebp, esp .text:00401273 sub esp, 80h .text:00401279 push offset aReverseEnginee .text:0040127E call sub_401554 .text:00401283 add esp, 4 .text:00401286 push offset aPleaseProvideT .text:0040128B call sub_401554 .text:00401290 add esp, 4 .text:00401293 push 80h ; Size .text:00401298 push 0 ; Val .text:0040129A lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:0040129D push eax ; Dst .text:0040129E call _memset .text:004012A3 add esp, 0Ch .text:004012A6 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004012A9 push ecx .text:004012AA push offset a127s ; "%127s" .text:004012AF call _scanf .text:004012B4 add esp, 8 .text:004012B7 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004012BA push edx ; Str2 .text:004012BB call sub_4011C0 .text:004012C0 add esp, 4 .text:004012C3 movsx eax, al .text:004012C6 test eax, eax .text:004012C8 jge short loc_4012D9 .text:004012CA push offset aYouFailed_ .text:004012CF call sub_401554 .text:004012D4 add esp, 4 .text:004012D7 jmp short loc_4012E6 .text:004012D9 loc_4012D9: ; CODE XREF: _main+58 .text:004012D9 push offset aYouWon_Goodbye .text:004012DE call sub_401554 .text:004012E3 add esp, 4 ..text:004012E6 loc_4012E6: ; CODE XREF: _main+67 .text:004012E6 mov eax, 1 .text:004012EB mov esp, ebp .text:004012ED pop ebp .text:004012EE retn .text:004012EE _main endp

At a glance, we can see that the main function doesn’t really do much of anything. It has a few calls and a few conditional statements. Also, just from the strings within some of these statements, it looks like we can assume there is a success/failure statement within this code; thus, the strings containing “YouFailed” and “YouWon”. We could switch over to the graph view right away to determine how these conditionals work, but first we will get an understanding for how this entire function works, so we have no surprises later on.

.text:00401279 push offset aReverseEnginee .text:0040127E call sub_401554 .text:00401283 add esp, 4 .text:00401286 push offset aPleaseProvideT .text:0040128B call sub_401554

Here we can see that, after setting up the stack, it’s pushing some static strings into the buffer and calling a function. By looking at the strings, it’s safe to assume this is some sort of startup header printing. However, it looks like IDA cannot determine exactly what function this binary is calling. Let’s go ahead and follow the call and see where it’s going; select the call instruction and press Enter to jump to that location.

.text:00401554 ; int printf(const char *,...) .text:00401554_printf proc near ; CODE XREF: sub_401000+65 .text:00401554; sub_401000+C0

Whoops! It looks like IDA didn’t want to identify what exactly this function was; it’s just a statically compiled printf. It’s fairly safe to assume this function isn’t doing anything odd or funky right now, so we’ll chalk that one up as a simple print function and get on with it. Let’s press the Backspace key in order to get back to our entry point and continue.

Note

Some functions may not always be what they appear to be; always give such obviously named static functions a good look before assuming the name is real. You never know what the bad guys might be trying to hide with clever names.

Since we know what that routine is, we should quickly rename it within IDA so we don’t have to worry about it confusing us later. The easiest way to accomplish this is to simply click the name of the instruction, and press the N key, which will pop up the rename dialog box. For the sake of ease, we’ll rename this function printf, since that is what it really is. Now that we have that out of the way and have confirmed that it is just printing strings as a sort of startup process, we’ll continue down the code.

.text:00401290 add esp, 4 .text:00401293 push 80h ; Size .text:00401298 push 0 ; Val .text:0040129A lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:0040129D push eax ; Dst .text:0040129E call _memset .text:004012A3 add esp, 0Ch .text:004012A6 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004012A9 push ecx .text:004012AA push offset a127s ; ";%127s" .text:004012AF call _scanf

Stepping through this set of instructions, it seems obvious that it is calling memset( ) to fill a buffer, and then using scanf( ) in order to read into a buffer. Specifically, we can see that the memset( ) call is filling the first 0×80, or 128, bytes of the Dst stack buffer with 0×00, or NULL. This can be deduced by seeing the values being pushed prior to the call, where we see the following four instructions:

.text:00401293 push 80h ; Size .text:00401298 push 0 ; Val .text:0040129A lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:0040129D push eax ; Dst

We can see here that the binary is pushing a size of 0×80, a value of 0 and finally pushing a pointer to the address of [ebp+Dst], our stack variable. Finally, we can also see that these same operations are being used for the scanf( ) call. Specifically, the instruction to load a pointer to the Dst buffer (lea ecx, [ebp+Dst]) is performed again, and the result of scanf( ) is saved within this buffer. We can also see that the scanf( ) call is correctly filling the buffer, with the %127s definition for its format string; thus only saving a maximum of 127 bytes to the buffer.

Note

If you don’t feel comfortable enough with 16-base hex numbers yet, you can always right-click a numerical value within IDA and view or select a different base type for the numeral. Although IDA’s default is hex values, you can click the value and press the H key in order to switch it to standard 10-base numbers.

Momentarily going back to the stack initialization portion of this function, we can check to make sure these sizes correspond with the actual size of the operations being performed on this variable. We can see IDA has already determined that this function did have a variable, and its size was 0×80 bytes long. Additionally, we can see the stack initialization calls performing this, thus confirming that this is the hard set size of this stack variable.

.text:00401270 Dst = byte ptr −80h ...... .text:00401273 sub esp, 80h

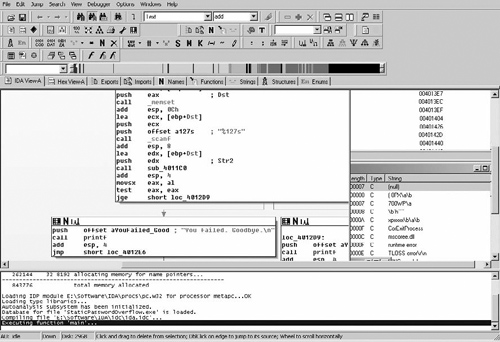

Now we have the uninteresting portions of the code out of the way and we understand what it all does. We can finally move forward to the interesting conditionals we saw within the code, which seem to be where all the magic must be happening. If you switch over to the graphing view now (press the Spacebar) you can see the conditional jumps that occur right after the sprintf( ) call, as shown in Figure 4.1. Additionally, you can see the mini-graph window, which becomes extremely useful with larger functions with many conditional jumps.

Moving past what seems to be the setup portion of this function, we can see that the function is calling a few subroutines prior to the conditional jump that has become our goal. Specifically, we can see that, prior to the conditional, the subroutine is calling another routine that is statically within the binary, and then immediately shifting the stack and performing the conditional.

.text:004012A9 push ecx .text:004012AA push offset a127s ; "%127s" .text:004012AF call _scanf .text:004012B4 add esp, 8 .text:004012B7 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004012BA push edx ; Str2 .text:004012BB call sub_4011C0 .text:004012C0 add esp, 4 .text:004012C3 movsx eax, al .text:004012C6 test eax, eax .text:004012C8 jge short loc_4012D9

We can move through the code immediately after the scanf( ) function call, which seems to handle the return value of scanf( ) and then prepare the stack to call this mysterious subroutine. Assuming you already have a good understanding of the stack structure and function call methods, let’s move through this again as review. Two values are pushed just prior to the scanf( ) call, one of which is a static string within our binary. Using documentation available from many sources, we can easily deduce not only that these are the variables for scanf( ) being pushed, but also what they mean. This is extremely useful when reversing binaries that use less-common library functions. It will always be a generally good idea to look up library functions prior to attempting to reverse them; if they aren’t critical to our goal, it can save lots of time to assume they perform as advertised. Below, you can see that scanf( ) is structured as such.

int scanf(const char *format, ...);

Noting this, we can now see that what is actually being loaded and passed is first the pointer to a buffer, and then the format string (always remember, variables are pushed into the stack “backwards”). Next, the stack is shifted 8 bytes, and then the pointer to our buffer [ebp+Dst] is loaded into edx and then pushed onto the stack. After this, our magical subroutine is simply called. It will be safe to assume now that this function is performing some sort of mystical processing on the buffer being filled by scanf( ), and returning an integer value which is then compared. This can be deduced by the instructions immediately after the call: movsx eax, al and test eax, eax. These instructions tell us that this portion of code is taking the return value of the called subroutine, call sub_4011C0, and conditionally jumping if it is greater than or equal to (the return value of calls are generally provided within the eax register).

So, as review, we now know that this mysterious subroutine is performing some sort of operation on our input value and providing the value that controls our conditional jump. We are getting closer to our goal! Now if we can discover what sort of operation this routine is performing and how to provide it with the correct value, we can control the conditional jump operation. For reference, let’s label the call statement input_process and then switch our IDA Pro view to that function by double-clicking its name.

Now that we know this function is going to be what inevitably controls our success or failure within the application, let’s step through the code in detail in order to understand what may be going on here. Additionally, looking at the code below, we will need to jump around a bit in order to truly understand what is happening. Not all reverse engineering can be performed by analyzing the executable from start to finish; analyzing end processing can sometimes yield a faster understanding of how everything got there.

.text:004011C0 ; int __cdecl input_process(char *Str2) .text:004011C0 input_process proc near ; CODE XREF: _main+4B .text:004011C0 Dst = byte ptr -80h .text:004011C0 var_7F= byte ptr -7Fh .text:004011C0 var_7E= byte ptr -7Eh .text:004011C0 var_7D= byte ptr -7Dh .text:004011C0 var_7C= byte ptr -7Ch .text:004011C0 var_7B= byte ptr -7Bh .text:004011C0 var_7A= byte ptr -7Ah .text:004011C0 var_79= byte ptr -79h .text:004011C0 var_78= byte ptr -78h .text:004011C0 var_77= byte ptr -77h .text:004011C0 var_76= byte ptr -76h .text:004011C0 var_75= byte ptr -75h .text:004011C0 var_74= byte ptr -74h .text:004011C0 var_73= byte ptr -73h .text:004011C0 var_72= byte ptr -72h .text:004011C0 var_71= byte ptr -71h .text:004011C0 var_70= byte ptr -70h .text:004011C0 Str2 = dword ptr 8 .text:004011C0 push ebp .text:004011C1 mov ebp, esp .text:004011C3 sub esp, 80h .text:004011C9 push 80h ; Size .text:004011CE push 0 ; Val .text:004011D0 lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:004011D3 push eax ; Dst .text:004011D4 call _memset .text:004011D9 add esp, 0Ch .text:004011DC mov [ebp+var_70], 0 .text:004011E0 mov [ebp+var_75], 73h .text:004011E4 mov [ebp+Dst], 74h .text:004011E8 mov [ebp+var_76], 73h .text:004011EC mov [ebp+var_7F], 68h .text:004011F0 mov [ebp+var_7A], 6Dh .text:004011F4 mov [ebp+var_7C], 69h .text:004011F8 mov [ebp+var_7B], 73h .text:004011FC mov [ebp+var_71], 64h .text:00401200 mov [ebp+var_74], 77h .text:00401204 mov [ebp+var_7E], 69h .text:00401208 mov [ebp+var_7D], 73h .text:0040120C mov [ebp+var_78], 70h .text:00401210 mov [ebp+var_73], 6Fh .text:00401214 mov [ebp+var_72], 72h .text:00401218 mov [ebp+var_79], 79h .text:0040121C mov [ebp+var_77], 61h .text:00401220 mov ecx, [ebp+Str2] .text:00401223 push ecx ; Str2 .text:00401224 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:00401227 push edx ; Str1 .text:00401228 call _strcmp .text:0040122D add esp, 8 .text:00401230 test eax, eax .text:00401232 jz short loc_401247 .text:00401234 push offset aInvalidPasswor ; "\n******* INVALID PASSWORD *******\n" .text:00401239 call printf .text:0040123E add esp, 4 .text:00401241 or al, 0FFh .text:00401243 jmp short loc_40125D .text:00401245 jmp short loc_40125D .text:00401247 loc_401247: ; CODE XREF: input_process+72 .text:00401247 mov eax, [ebp+Str2] .text:0040124A push eax .text:0040124B push offset aSIsCorrect_ ; "%s is correct.\n\n" .text:00401250 call printf .text:00401255 add esp, 8 .text:00401258 call sub_401000 .text:0040125D loc_40125D: ; CODE XREF: input_process+83 .text:0040125D; input_process+85 .text:0040125D mov esp, ebp .text:0040125F pop ebp .text:00401260 retn .text:00401260 input_process endp

We can see here that this function is a bit larger than the entrypoint, but it appears that IDA Pro has helped that to an extent. Briefly looking at the code, something immediately jumps out as an important portion of the function and as something we should begin to look at. At the address 00401228, there is a strcmp( ) call.

.text:00401220 mov ecx, [ebp+Str2] .text:00401223 push ecx ; Str2 .text:00401224 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:00401227 push edx ; Str1 .text:00401228 call _strcmp

Not only does it appear to be a strcmp( ) call to compare strings, but it is using the buffer that stores the input from scanf( ), ebp+Dst. This looks promising for our goal: a string comparison against our input value, followed by a conditional statement that determines success or failure. But what can it be comparing against? Let’s step back a bit in the code and take a look. In this string comparison, we can see the function is comparing the pointers in ecx and edx, which are respectively ebp+Str2 and ebp+Dst. Before actually determining what Str2 is, let’s rename it for reference to StrPassword.

Just prior to the comparison, there is a major chunk of mov instructions being performed on what appears to be a sequential segment of memory, which is actually within our preallocated buffers. A 128-byte buffer, or 0×80 bytes, is being allocated on the stack and being NULLed out by the memset( ) function.

.text:004011C0 push ebp .text:004011C1 mov ebp, esp .text:004011C3 sub esp, 80h .text:004011C9 push 80h ; Size .text:004011CE push 0 ; Val .text:004011D0 lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:004011D3 push eax ; Dst .text:004011D4 call _memset

After this buffer is prepared, it is sequentially filled with these static variables. Upon closer inspection, however, it seems all these values are relatively close to each other numerically as well. Not only that, but they actually appear to be within the ASCII range of characters, which would make sense since they are being used in a string comparison. Now, let’s figure out what this value actually is! Sadly, when statically analyzing a binary we do not have the option of popping it open in a debugger and waiting for the value to be filled, so it will be best to just break apart the values by hand and determine what they are.

Tip

Most reverse engineering experts will frequently use pencil and paper when actually diving into a binary. Taking notes, quickly mapping paths or values, and many other things are always going to be faster on paper as long as we still have keyboards on computers. Try to always keep a pencil and paper next to you so you can quickly note addresses, values and other random items; our memories are never going to be perfect.

However, before we get further into it, here is a small anomaly within IDA’s interpretation of this chunk of code that is interesting. In the middle of all our mov instructions, there is one mov that IDA has determined is writing to our input buffer.

.text:004011E4 mov [ebp+Dst], 74h

How could this be? Peeking back at the variables IDA has determined this function has, we can see it has attempted to automatically assign a different variable reference for every single mov instruction except for this anomaly. At a glance, this really does make the binary seem more complex and confusing. Because of the way IDA Pro disassembles functions, it sometimes has difficulty internally determining the actual structure of memory. Furthermore, it is a generally good rule of thumb not to totally rely on IDA Pro’s dissemination of variables and arguments; instead, use them as references at a glance when required. This anomaly is due to these types of issues that IDA has; it hasn’t appropriately taken into account stack alignment adjustments in its dissemination of the variables. So, ebp+dst, as IDA has determined it to be, would also be var_80 if IDA named it as such. We know a pointer was pushed into the stack prior to the function being called, and because of this IDA has not appropriately accounted for the stack shift inherent in this operation, thus rendering this misleading piece of code. Knowing how the stack is structured, we can determine how it looks as follows:

[Buffer Created]

[Pointer to Our Input String]

[Stack Pointer Save and Return Address]

[Real Input String]

Therefore, this instruction, which IDA says is overwriting our pointer, is actually writing the first byte of our character array, and thus is the first character of our password string. Now that we have taken note of that small problem and can appropriately account for it, we can sit down and figure out what this character array actually contains and what the password is. See Table 4.1.

Note

When performing static analysis on binaries, it never hurts to map out the stack in a table on paper as you work through a function. Especially in more complex functions, we can’t completely rely on IDA to get it right every time. This is why understanding actual execution and stack structure is even more important in static analysis. We have to infer how the executable is going to behave every step of the way without having the ability to test and verify our assumptions.

We can see now that this is in fact a valid ASCII string that is being compared against our input buffer. Since this is a generic ×86 binary, of course it is being assigned backwards in code. Therefore, our password is “thisismypassword”. Going back and looking at the code, we can see that the conditional within this function is using the result of strcmp( ) in order to determine whether we provided the correct password or not. We have now passed the first hurdle in determining what this application does and how it is protecting itself.

Moving forward in the code, we can see that there is actually a check for the correct password using a conditional jump, followed by a final call to an external function prior to returning. Even more interesting, it seems that the return value of the called function, sub_40100, is passed through as the return value for this function as well.

.text:00401255 add esp, 8 .text:00401258 call sub_401000 .text:0040125Dloc_40125D: ; CODE XREF: input_process+83 .text:0040125D; input_process+85j .text:0040125D mov esp, ebp .text:0040125F pop ebp .text:00401260 retn

How is this determined? Just prior to the call to the function sub_401000, the stack is actually shifted by 8 bytes. More specifically, ESP is incremented. This moves the stack appropriately so that the actual stack location of both functions’ return values will be the same, thus passing the value through.

Stepping back for a moment, we now know a few new bits of information about the binary. First, we now know we need a password in order to progress anywhere. Secondly, if we do enter the correct password, it will progress to a second function, which is the final return value given to the entrypoint main function. In order to get a successful response, then, we will be required to meet whatever conditions exist within the third function as well. On that note, let’s rename the call to SecondCheck and double-click it to view it.

.text:00401000 SecondCheck proc near ; CODE XREF: input_process+98 .text:00401000 Dst = byte ptr -4D0h .text:00401000 var_450 = byte ptr -450h .text:00401000 Dest = byte ptr -400h .text:00401000 push ebp .text:00401001 mov ebp, esp .text:00401003 sub esp, 4D0h .text:00401009 push esi .text:0040100A push edi .text:0040100B mov ecx, 13h .text:00401010 mov esi, offset aPleaseSelectAn ; "Please select an option from the follow"... .text:00401015 lea edi, [ebp+var_450] .text:0040101B rep movsd .text:0040101D movsw .text:0040101F movsb .text:00401020 push 80h ; Size .text:00401025 push 0 ; Val .text:00401027 lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:0040102D push eax ; Dst .text:0040102E call _memset .text:00401033 add esp, 0Ch .text:00401036 push 80h ; Size .text:0040103B push 0 ; Val .text:0040103D lea ecx, [ebp+Dest] .text:00401043 push ecx ; Dst .text:00401044 call _memset .text:00401049 add esp, 0Ch .text:0040104C loc_40104C: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+1AB .text:0040104C mov edx, 1 .text:00401051 test edx, edx .text:00401053 jz loc_4011B0 .text:00401059 lea eax, [ebp+var_450] .text:0040105F push eax .text:00401060 push offset aS ; "%s" .text:00401065 call printf .text:0040106A add esp, 8 .text:0040106D lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] .text:00401073 push ecx .text:00401074 push offset a127s_0 ; "%127s" .text:00401079 call _scanf .text:0040107E add esp, 8 .text:00401081 push 80h ; Count .text:00401086 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:0040108C push edx ; Source .text:0040108D lea eax, [ebp+Dest] .text:00401093 push eax ; Dest .text:00401094 call _strncat .text:00401099 add esp, 0Ch .text:0040109C push offset Str2 ; "Exit" .text:004010A1 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004010A7 push ecx ; Str1 .text:004010A8 call _strcmp .text:004010AD add esp, 8 .text:004010B0 test eax, eax .text:004010B2 jnz short loc_4010CD .text:004010B4 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004010BA push edx .text:004010BB push offset aOperationSComp ; "Operation: %s: Completed\n" .text:004010C0 call printf .text:004010C5 add esp, 8 .text:004010C8 jmp loc_401195 .text:004010CD loc_4010CD: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+B2 .text:004010CD push offset aSelect ; "Select" .text:004010D2 lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:004010D8 push eax ; Str1 .text:004010D9 call _strcmp .text:004010DE add esp, 8 .text:004010E1 test eax, eax .text:004010E3 jnz short loc_4010FE .text:004010E5 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004010EB push ecx .text:004010EC push offset aOperationSCo_0 ; "Operation: %s: Completed\n" .text:004010F1 call printf .text:004010F6 add esp, 8 .text:004010F9 jmp loc_401195 .text:004010FE loc_4010FE: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+E3 .text:004010FE push offset aDrop ; "Drop" .text:00401103 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:00401109 push edx ; Str1 .text:0040110A call _strcmp .text:0040110F add esp, 8 .text:00401112 test eax, eax .text:00401114 jnz short loc_40112C .text:00401116 lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:0040111C push eax .text:0040111D push offset aOperationSCo_1 ; "Operation: %s: Completed\n" .text:00401122 call printf .text:00401127 add esp, 8 .text:0040112A jmp short loc_401195 .text:0040112C loc_40112C: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+114 .text:0040112C push offset aCreate ; "Create" .text:00401131 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] .text:00401137 push ecx ; Str1 .text:00401138 call _strcmp .text:0040113D add esp, 8 .text:00401140 test eax, eax .text:00401142 jnz short loc_40115A .text:00401144 lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:0040114A push edx .text:0040114B push offset aOperationSCo_2 ; "Operation: %s: Completed\n" .text:00401150 call printf .text:00401155 add esp, 8 .text:00401158 jmp short loc_401195 .text:0040115A loc_40115A: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+142 .text:0040115A push offset aExit_0 ; "Exit" .text:0040115F lea eax, [ebp+Dst] .text:00401165 push eax ; Str1 .text:00401166 call _strcmp .text:0040116B add esp, 8 .text:0040116E test eax, eax .text:00401170 jnz short loc_401188 .text:00401172 lea ecx, [ebp+Dst] .text:00401178 push ecx .text:00401179 push offset aOperationSCo_3 ; "Operation: %s: Completed\n" .text:0040117E call printf .text:00401183 add esp, 8 .text:00401186 jmp short loc_401195 .text:00401188 loc_401188: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+170 .text:00401188 push offset aInvalidCommand ; "Invalid command failure. Please try aga"... .text:0040118D call printf .text:00401192 add esp, 4 .text:00401195 loc_401195: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+C8, SecondCheck+F9 .text:00401195 push 80h ; Size .text:0040119A push 0 ; Val .text:0040119C lea edx, [ebp+Dst] .text:004011A2 push edx ; Dst .text:004011A3 call _memset .text:004011A8 add esp, 0Ch .text:004011AB jmp loc_40104C .text:004011B0 loc_4011B0: ; CODE XREF: SecondCheck+53 .text:004011B0 mov al, 1 .text:004011B2 pop edi .text:004011B3 pop esi .text:004011B4 mov esp, ebp .text:004011B6 pop ebp .text:004011B7 retn .text:004011B7 SecondCheck endp

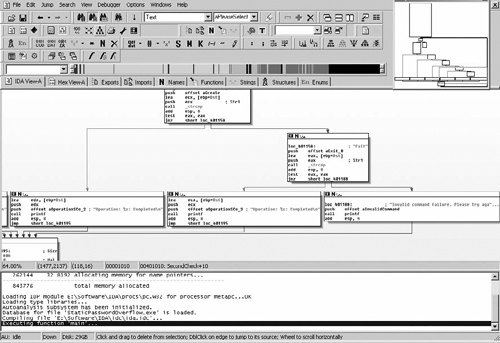

As you can see, this function is larger than all the others. Although our techniques so far are promising, we are moving into a more complicated function and, as such, need to shift our method of analysis a bit. When diving into a function a bit more complex, it is better to get an overall picture of the function calls made and different conditionals that may exist prior to actually getting down and dirty with its operations. On that note, let’s begin by mapping out the series of function calls made within this function. Specifically, we want to go into the graph view and see what IDA Pro has determined the layout of conditionals to be for us, allowing us to dissect much more information about the call structure between these functions, as shown in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2. Functions

memset() | Fills both stack buffers within the function with nulls (0×00) |

printf() | Outputs command request header text |

scanf() | Receives and stores user input in the first buffer |

strncat() | Copies the received data from the first buffer to the second |

strcmp() | Compares the input provided by the user against a static command string |

printf() | Outputs the appropriate command result |

As you can see, the overall structure of the function isn’t as complicated as it seems, except for the multiple conditional statements that exist within it. However, from a glance at the graph view, reading the output that printf is specified to give on different conditions, it becomes obvious that this method is some form of a command parsing engine; it takes commands with scanf, parses to check for them, and then outputs the appropriate results. Additionally, when looking at this in greater detail, we can see by the graph view that this is in fact an infinite loop as well. Although we would be able to see this if we analyzed the jump statements within this binary long enough, IDA Pro provides us with this information by showing an extra overall wrapping connection from the final step of the function to the beginning. It becomes obvious that this is, in fact, a simple parsing loop for command strings. (See Figure 4.2.)

IDA has many tools and views, such as the graph view, which assist in rapidly assessing the actual operations within a binary. | |

Always review the overall flow of a function or set of functions prior to diving into complete dissections of the entire block of code. | |

It will help in the long run to obtain a level of comfort with other number sets; specifically with base-16 hex. The faster you are able to determine a value in your head, the less time you will spend with calculator open. | |

Compilers will do funny things to binaries during compile time; these can sometimes be convoluted or pointless, but the differences are generally minimal in most optimization cases. |