Chapter 17. Scraping Remotely

In the last chapter, you looked at running web scrapers across multiple threads and processes, where communication between them was somewhat limited or had to be carefully planned. This chapter brings this concept to its logical conclusion—running crawlers not just in separate processes, but on entirely separate machines.

That this is the last technical chapter is the book is somewhat appropriate. Until now you have been running all the Python applications from the command line, within the confines of your home computer. Sure, you might have installed MySQL in an attempt to replicate the environment of a real-life server. But it’s just not the same. As the saying goes: “If you love something, set it free.”

This chapter covers several methods for running scripts from different machines, or even just different IP addresses on your own machine. Although you might be tempted to put this step off as something you don’t need right now, you might be surprised at how easy it is to get started with the tools you already have (such as a personal website on a paid hosting account), and how much easier your life becomes when you stop trying to run Python scrapers from your laptop.

Why Use Remote Servers?

Although using a remote server might seem like an obvious step when launching a web app intended for use by a wide audience, more often than not the tools we build for our own purposes are left running locally. People who decide to push onto a remote platform usually base their decision on two primary motivations: the need for greater power and flexibility, and the need to use an alternative IP address.

Avoiding IP Address Blocking

When building web scrapers, the rule of thumb is: almost everything can be faked. You can send emails from addresses you don’t own, automate mouse-movement data from a command line, or even horrify web administrators by sending their website traffic from Internet Explorer 5.0.

The one thing that cannot be faked is your IP address. Anyone can send you a letter with the return address: “The President, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest, Washington, DC 20500.” However, if the letter is postmarked from Albuquerque, NM, you can be fairly certain you’re not corresponding with the President of the United States.1

Most efforts to stop scrapers from accessing websites focus on detecting the difference between humans and bots. Going so far as to block IP addresses is a little like a farmer giving up spraying pesticides in favor of just torching the field. It’s a last-ditch but effective method of discarding packets sent from troublesome IP addresses. However, there are problems with this solution:

-

IP address access lists are painful to maintain. Although large websites most often have their own programs automating some of the routine management of these lists (bots blocking bots!), someone has to occasionally check them, or at least monitor their growth for problems.

-

Each address adds a tiny amount of processing time to receive packets, as the server must check received packets against the list to decide whether to approve them. Many addresses multiplied by many packets can add up quickly. To save on processing time and complexity, admins often group these IP addresses into blocks and make rules such as “all 256 addresses in this range are blocked” if there are a few tightly clustered offenders. Which leads us to the third point.

-

IP address blocking can lead to blocking the “good guys” as well. For example, while I was an undergrad at Olin College of Engineering, one student wrote some software that attempted to rig votes for popular content on http://digg.com (this was before Reddit was in vogue). A single blocked IP address led to an entire dormitory being unable to access the site. The student simply moved his software to another server; in the meantime, Digg lost page visits from many regular users in its prime target demographic.

Despite its drawbacks, IP address blocking remains an extremely common method for server administrators to stop suspected web scrapers from accessing servers. If an IP address is blocked, the only real solution is to scrape from a different IP address. This can be accomplished by moving the scraper to a new server or routing your traffic through a different server using a service such as Tor.

Portability and Extensibility

Some tasks are too large for a home computer and internet connection. Although you don’t want to put a large load on any single website, you might be collecting data across a wide range of sites, and require a lot more bandwidth and storage than your current setup can provide.

Moreover, by offloading computationally intensive processing, you can free up your home machine’s cycles for more important tasks (World of Warcraft, anyone?). You don’t have to worry about maintaining power and an internet connection (launch your app at a Starbucks, pack up your laptop, and leave, knowing that everything’s still running safely), and you can access your collected data anywhere there’s an internet connection.

If you have an application that requires so much computing power that a single Amazon extra-large computing instance won’t satisfy you, you can also look into distributed computing. This allows multiple machines to work in parallel to accomplish your goals. As a simple example, you might have one machine crawl one set of sites and another crawl a second set of sites, and have both of them store collected data in the same database.

Of course, as noted in previous chapters, many can replicate what Google search does, but few can replicate the scale at which Google search does it. Distributed computing is a large field of computer science that is outside the scope of this book. However, learning how to launch your application onto a remote server is a necessary first step, and you might be surprised at what computers are capable of these days.

Tor

The Onion Router network, better known by the acronym Tor, is a network of volunteer servers set up to route and reroute traffic through many layers (hence the onion reference) of different servers in order to obscure its origin. Data is encrypted before it enters the network so that if any particular server is eavesdropped on, the nature of the communication cannot be revealed. In addition, although the inbound and outbound communications of any particular server can be compromised, one would need to know the details of inbound and outbound communication for all the servers along the path of communication in order to decipher the true start and endpoints of a communication—a near-impossible feat.

Tor is commonly used by human rights workers and political whistleblowers to communicate with journalists, and receives much of its funding from the US government. Of course, it is also commonly used for illegal activities as well, and so remains a constant target for government surveillance (although to date, the surveillance has had only mixed success).

Limitations of Tor Anonymity

Although the reason you are using Tor in this book is to change your IP address, not achieve complete anonymity per se, it is worth taking a moment to address some of the strengths and limitations of Tor’s ability to anonymize traffic.

Although you can assume when using Tor that the IP address you are coming from, according to a web server, is not an IP address that can be traced back to you, any information you share with that web server might expose you. For instance, if you log into your own Gmail account and then make incriminating Google searches, those searches can now be tied back to your identity.

Beyond the obvious, however, even the act of logging into Tor might be hazardous to your anonymity. In December 2013, a Harvard undergraduate student, in an attempt to get out of final exams, emailed a bomb threat to the school through the Tor network, using an anonymous email account. When the Harvard IT team looked at their logs, they found traffic going out to the Tor network from only a single machine, registered to a known student, during the time that the bomb threat was sent. Although they could not identify the eventual destination of this traffic (only that it was sent across Tor), the fact that the times matched up and only a single machine was logged in at the time was damning enough to prosecute the student.

Logging into Tor is not an automatic invisibility cloak, nor does it give you free reign to do as you please on the internet. Although it is a useful tool, be sure to use it with caution, intelligence, and, of course, morality.

Having Tor installed and running is a requirement for using Python with Tor, as you will see in the next section. Fortunately, the Tor service is extremely easy to install and start running with. Just go to the Tor downloads page and download, install, open, and connect. Keep in mind that your internet speed might appear to be slower while using Tor. Be patient—it might be going around the world several times!

PySocks

PySocks is a remarkably simple Python module that is capable of routing traffic through proxy servers and that works fantastically in conjunction with Tor. You can download it from its website or use any number of third-party module managers to install it.

Although not much in the way of documentation exists for this module, using it is extremely straightforward. The Tor service must be running on port 9150 (the default port) while running this code:

importsocksimportsocketfromurllib.requestimporturlopensocks.set_default_proxy(socks.SOCKS5,"localhost",9150)socket.socket=socks.socksocket(urlopen('http://icanhazip.com').read())

The website http://icanhazip.com displays only the IP address for the client connecting to the server and can be useful for testing purposes. When this script is run, it should display an IP address that is not your own.

If you want to use Selenium and ChromeDriver with Tor, you don’t need PySocks at all—just make sure that Tor is currently running and add the optional proxy-server chrome option, specifying that Selenium should connect on the socks5 protocol on port 9150:

fromseleniumimportwebdriverfromselenium.webdriver.chrome.optionsimportOptionschrome_options=Options()chrome_options.add_argument("--headless")chrome_options.add_argument("--proxy-server=socks5://127.0.0.1:9150")driver=webdriver.Chrome(executable_path='drivers/chromedriver',options=chrome_options)driver.get('http://icanhazip.com')(driver.page_source)driver.close()

Again, this should print out an IP address that is not your own but the one that your running Tor client is currently using.

Remote Hosting

Although complete anonymity is lost after you pull out your credit card, hosting your web scrapers remotely may dramatically improve their speed. This is both because you’re able to purchase time on much larger machines than you likely own, but also because the connection no longer has to bounce through layers of a Tor network in order to reach its destination.

Running from a Website-Hosting Account

If you have a personal or business website, you might already likely have the means to run your web scrapers from an external server. Even with relatively locked-down web servers, where you have no access to the command line, it is possible to trigger scripts to start and stop through a web interface.

If your website is hosted on a Linux server, the server likely already runs Python. If you’re hosting on a Windows server, you might be out of luck; you’ll need to check specifically to see if Python is installed, or if the server administrator is willing to install it.

Most small web-hosting providers come with software called cPanel, used to provide basic administration services and information about your website and related services. If you have access to cPanel, you can make sure that Python is set up to run on your server by going to Apache Handlers and adding a new handler (if it is not already present):

Handler: cgi-script Extension(s): .py

This tells your server that all Python scripts should be executed as a CGI-script. CGI, which stands for Common Gateway Interface, is any program that can be run on a server and dynamically generate content that is displayed on a website. By explicitly defining Python scripts as CGI scripts, you’re giving the server permission to execute them, rather than just display them in a browser or send the user a download.

Write your Python script, upload it to the server, and set the file permissions to 755 to allow it to be executed. To execute the script, navigate to the place you uploaded it to through your browser (or even better, write a scraper to do it for you). If you’re worried about the general public accessing and executing the script, you have two options:

-

Store the script at an obscure or hidden URL and make sure to never link to the script from any other accessible URL to avoid search engines indexing it.

-

Protect the script with a password, or require that a password or secret token be sent to it before it can execute.

Of course, running a Python script from a service that is specifically designed to display websites is a bit of a hack. For instance, you’ll probably notice that your web scraper-cum-website is a little slow to load. In fact, the page doesn’t actually load (complete with the output of all print statements you might have written in) until the entire scrape is complete. This might take minutes, hours, or never complete at all, depending on how it is written. Although it certainly gets the job done, you might want more real-time output. For that, you’ll need a server that’s designed for more than just the web.

Running from the Cloud

Back in the olden days of computing, programmers paid for or reserved time on computers in order to execute their code. With the advent of personal computers, this became unnecessary—you simply write and execute code on your own computer. Now, the ambitions of the applications have outpaced the development of the microprocessor to such a degree that programmers are once again moving to pay-per-hour computing instances.

This time around, however, users aren’t paying for time on a single, physical machine but on its equivalent computing power, often spread among many machines. The nebulous structure of this system allows computing power to be priced according to times of peak demand. For instance, Amazon allows for bidding on “spot instances” when low costs are more important than immediacy.

Compute instances are also more specialized, and can be selected based on the needs of your application, with options like “high memory,” “fast computing,” and “large storage.” Although web scrapers don’t usually use much in the way of memory, you may want to consider large storage or fast computing in lieu of a more general-purpose instance for your scraping application. If you’re doing large amounts of natural language processing, OCR work, or path finding (such as with the Six Degrees of Wikipedia problem), a fast computing instance might work well. If you’re scraping large amounts of data, storing files, or doing large-scale analytics, you might want to go for an instance with storage optimization.

Although the sky is the limit as far as spending goes, at the time of this writing, instances start at just 1.3 cents an hour (for an Amazon EC2 micro instance), and Google’s cheapest instance is 4.5 cents an hour, with a minimum of just 10 minutes. Thanks to the economies of scale, buying a small compute instance with a large company is about the same as buying your own physical, dedicated machine—except that now, you don’t need to hire an IT guy to keep it running.

Of course, step-by-step instructions for setting up and running cloud computing instances are somewhat outside the scope of this book, but you will likely find that step-by-step instructions are not needed. With both Amazon and Google (not to mention the countless smaller companies in the industry) vying for cloud computing dollars, they’ve made setting up new instances as easy as following a simple prompt, thinking of an app name, and providing a credit card number. As of this writing, both Amazon and Google also offer hundreds of dollars’ worth of free computing hours to further tempt new clients.

Once you have an instance set up, you should be the proud new owner of an IP address, username, and public/private keys that can be used to connect to your instance through SSH. From there, everything should be the same as working with a server that you physically own—except, of course, you no longer have to worry about hardware maintenance or running your own plethora of advanced monitoring tools.

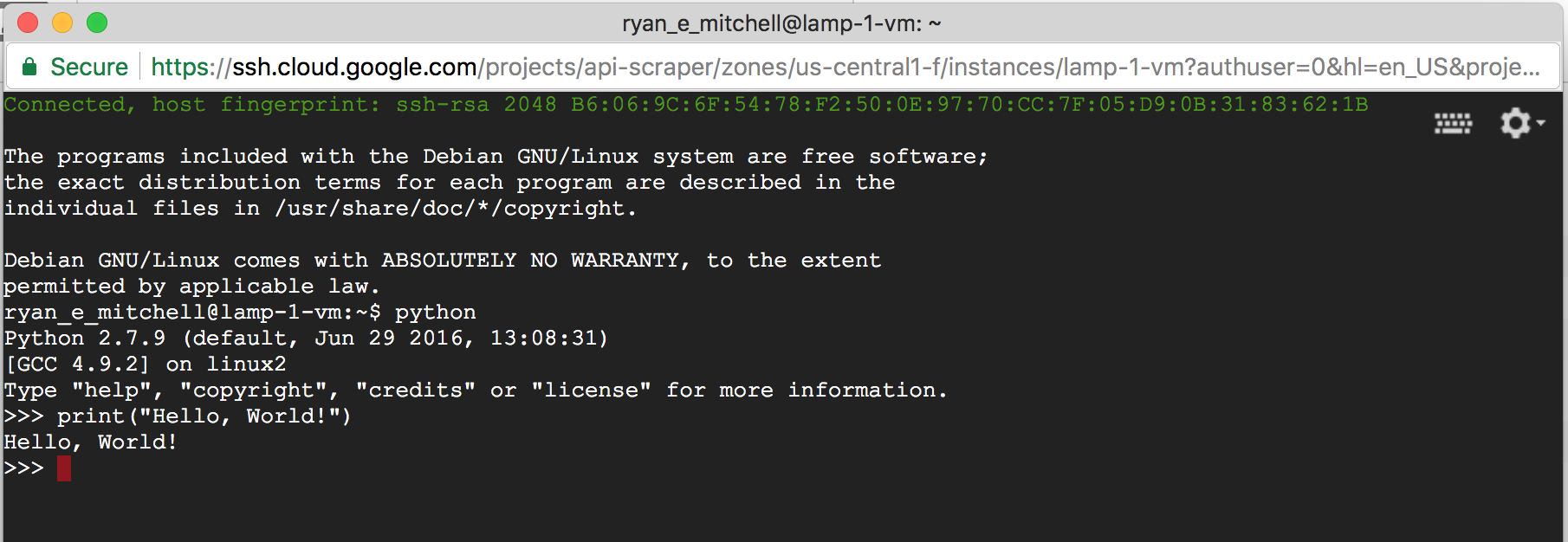

For quick and dirty jobs, especially if you don’t have a lot of experience dealing with SSH and key pairs, I’ve found that Google’s Cloud Platform instances can be easier to get up and running right away. They have a simple launcher and even have a button available after launch to view an SSH terminal right in the browser, as shown in Figure 17-1.

Figure 17-1. Browser-based terminal from a running Google Cloud Platform VM instance

Additional Resources

Many years ago, running “in the cloud” was mostly the domain of those who felt like slogging through the documentation and already had some server administration experience. However, today, the tools have improved dramatically, due to increased popularity and competition among cloud computing providers.

Still, for building large-scale or more-complex scrapers and crawlers, you might want a little more guidance on creating a platform for collecting and storing data.

Google Compute Engine by Marc Cohen, Kathryn Hurley, and Paul Newson (O’Reilly) is a straightforward resource on using Google Cloud Computing with both Python and JavaScript. Not only does it cover Google’s user interface, but also the command-line and scripting tools that you can use to give your application greater flexibility.

If you prefer to work with Amazon, Mitch Garnaat’s Python and AWS Cookbook (O’Reilly) is a brief but extremely useful guide that will get you started with Amazon Web Services and show you how to get a scalable application up and running.

1 Technically, IP addresses can be spoofed in outgoing packets, which is a technique used in distributed denial-of-service attacks, where the attackers don’t care about receiving return packets (which, if sent, will be sent to the wrong address). But web scraping is by definition an activity in which a response from the web server is required, so we think of IP addresses as one thing that can’t be faked.