Chapter 16. Web Crawling in Parallel

Web crawling is fast. At least, it’s usually much faster than hiring a dozen interns to copy data from the internet by hand! Of course, the progression of technology and the hedonic treadmill demand that at a certain point even this will not be “fast enough.” That’s the point at which people generally start to look toward distributed computing.

Unlike most other technology fields, web crawling cannot often be improved simply by “throwing more cycles at the problem.” Running one process is fast; running two processes is not necessarily twice as fast. Running three processes might get you banned from the remote server you’re hammering on with all your requests!

However, in some situations parallel web crawling, or running parallel threads/processes, can still be of benefit:

-

Collecting data from multiple sources (multiple remote servers) instead of just a single source

-

Performing long/complex operations on the collected data (such as doing image analysis or OCR) that could be done in parallel with fetching the data

-

Collecting data from a large web service where you are paying for each query, or where creating multiple connections to the service is within the bounds of your usage agreement

Processes versus Threads

Python supports both multiprocessing and multithreading. Both multiprocessing and multithreading achieve the same ultimate goal: performing two programming tasks at the same time instead of running the program in a more traditional linear way.

In computer science, each process running on an operating system can have multiple threads. Each process has its own allocated memory, which means that multiple threads can access that same memory, while multiple processes cannot and must communicate information explicitly.

Using multithreaded programming to execute tasks in separate threads with shared memory is often considered easier than multiprocess programming. But this convenience comes at a cost.

Python’s global interpreter lock (or GIL) acts to prevent threads from executing the same line of code at once. The GIL ensures that the common memory shared by all processes does not become corrupted (for instance, bytes in memory being half written with one value and half written with another value). This locking makes it possible to write a multithreaded program and know what you’re getting, within the same line, but it also has the potential to create bottlenecks.

Multithreaded Crawling

Python 3.x uses the _thread module; the thread module is deprecated.

The following example illustrates using multiple threads to perform a task:

import_threadimporttimedefprint_time(threadName,delay,iterations):start=int(time.time())foriinrange(0,iterations):time.sleep(delay)seconds_elapsed=str(int(time.time())-start)("{} {}".format(seconds_elapsed,threadName))try:_thread.start_new_thread(print_time,('Fizz',3,33))_thread.start_new_thread(print_time,('Buzz',5,20))_thread.start_new_thread(print_time,('Counter',1,100))except:('Error: unable to start thread')while1:pass

This is a reference to the classic FizzBuzz programming test, with a somewhat more verbose output:

1 Counter 2 Counter 3 Fizz 3 Counter 4 Counter 5 Buzz 5 Counter 6 Fizz 6 Counter

The script starts three threads, one that prints “Fizz” every three seconds, another that prints “Buzz” every five seconds, and a third that prints “Counter" every second.

After the threads are launched, the main execution thread hits a while 1 loop that keeps the program (and its child threads) executing until the user hits Ctrl-C to stop execution.

Rather than printing fizzes and buzzes, you can perform a useful task in the threads, such as crawling a website:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportreimportrandomimport_threadimporttimedefget_links(thread_name,bs):('Getting links in {}'.format(thread_name))returnbs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$'))# Define a function for the threaddefscrape_article(thread_name,path):html=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(path))time.sleep(5)bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')title=bs.find('h1').get_text()('Scraping {} in thread {}'.format(title,thread_name))links=get_links(thread_name,bs)iflen(links)>0:newArticle=links[random.randint(0,len(links)-1)].attrs['href'](newArticle)scrape_article(thread_name,newArticle)# Create two threads as followstry:_thread.start_new_thread(scrape_article,('Thread 1','/wiki/Kevin_Bacon',))_thread.start_new_thread(scrape_article,('Thread 2','/wiki/Monty_Python',))except:('Error: unable to start threads')while1:pass

Note the inclusion of this line:

time.sleep(5)

Because you are crawling Wikipedia almost twice as fast as you would with just a single thread, the inclusion of this line prevents the script from putting too much of a load on Wikipedia’s servers. In practice, when running against a server where the number of requests is not an issue, this line should be removed.

What if you want to rewrite this slightly to keep track of the articles the threads have collectively seen so far, so that no article is visited twice? You can use a list in a multithreaded environment in the same way that you use it in a single-threaded environment:

visited=[]defget_links(thread_name,bs):('Getting links in {}'.format(thread_name))links=bs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$'))return[linkforlinkinlinksiflinknotinvisited]defscrape_article(thread_name,path):visited.append(path)

Note that you are appending the path to the list of visited paths as the first action that scrape_article takes. This reduces, but does not entirely eliminate, the chances that it will be scraped twice.

If you are unlucky, both threads might still stumble across the same path at the same instant, both will see that it is not in the visited list, and both will subsequently add it to the list and scrape at the same time. However, in practice this is unlikely to happen because of the speed of execution and the number of pages that Wikipedia contains.

This is an example of a race condition. Race conditions can be tricky to debug, even for experienced programmers, so it is important to evaluate your code for these potential situations, estimate their likelihood, and anticipate the seriousness of their impact.

In the case of this particular race condition, where the scraper goes over the same page twice, it may not be worth writing around.

Race Conditions and Queues

Although you can communicate between threads with lists, lists are not specifically designed for communication between threads, and their misuse can easily cause slow program execution or even errors resulting from race conditions.

Lists are great for appending to or reading from, but not so great for removing items at arbitrary points, especially from the beginning of the list. Using a line like

myList.pop(0)

actually requires Python to rewrite the entire list, slowing program execution.

More dangerous, lists also make it convenient to accidentally write in a line that isn’t thread-safe. For instance

myList[len(myList)-1]

may not actually get you the last item in the list in a multithreaded environment, or it may even throw an exception if the value for len(myList)-1 is calculated immediately before another operation modifies the list.

One might argue that the preceding statement can be more “Pythonically” written as myList[-1], and of course, no one has ever accidentally written non-Pythonic code in a moment of weakness (especially not Java developers thinking back to their days of patterns like myList[myList.length-1] )! But even if your code is beyond reproach, consider these other forms of non-thread-safe lines involving lists:

my_list[i]=my_list[i]+1my_list.append(my_list[-1])

Both of these may result in a race condition that can cause unexpected results. So let’s abandon lists and pass messages to threads using nonlist variables!

# Read the message in from the global listmy_message=global_message# Write a message backglobal_message='I'veretrievedthemessage'# do something with my_message

That seems nice until you realize that you might have inadvertently overwritten another message coming in from another thread, in the instant between the first and second lines, with the text “I’ve got your message.” So now you just need to construct an elaborate series of personal message objects for each thread with some logic to figure out who gets what...or you could use the Queue module built for this exact purpose.

Queues are list-like objects that operate on either a First In First Out (FIFO) approach or a Last In First Out (LIFO) approach. A queue receives messages from any thread via queue.put('My message') and can transmit the message to any thread that calls queue.get().

Queues are not designed to store static data, but to transmit it in a thread-safe way. After it’s retrieved from the queue, it should exist only in the thread that retrieved it. For this reason, they are commonly used to delegate tasks or send temporary notifications.

This can be useful in web crawling. For instance, let’s say that you want to persist the data collected by your scraper into a database, and you want each thread to be able to persist its data quickly. A single shared connection for all threads might cause issues (a single connection cannot handle requests in parallel), but it makes no sense to give every single scraping thread its own database connection. As your scraper grows in size (you may be collecting data from a hundred different websites in a hundred different threads eventually), this might translate into a lot of mostly idle database connections doing only an occasional write after a page loads.

Instead, you can have a smaller number of database threads, each with its own connection, sitting around taking items from a queue and storing them. This provides a much more manageable set of database connections.

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportreimportrandomimport_threadfromqueueimportQueueimporttimeimportpymysqldefstorage(queue):conn=pymysql.connect(host='127.0.0.1',unix_socket='/tmp/mysql.sock',user='root',passwd='',db='mysql',charset='utf8')cur=conn.cursor()cur.execute('USE wiki_threads')while1:ifnotqueue.empty():article=queue.get()cur.execute('SELECT * FROM pages WHERE path =%s',(article["path"]))ifcur.rowcount==0:("Storing article {}".format(article["title"]))cur.execute('INSERT INTO pages (title, path) VALUES (%s,%s)',\(article["title"],article["path"]))conn.commit()else:("Article already exists: {}".format(article['title']))visited=[]defgetLinks(thread_name,bs):('Getting links in {}'.format(thread_name))links=bs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$'))return[linkforlinkinlinksiflinknotinvisited]defscrape_article(thread_name,path,queue):visited.append(path)html=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(path))time.sleep(5)bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')title=bs.find('h1').get_text()('Added {} for storage in thread {}'.format(title,thread_name))queue.put({"title":title,"path":path})links=getLinks(thread_name,bs)iflen(links)>0:newArticle=links[random.randint(0,len(links)-1)].attrs['href']scrape_article(thread_name,newArticle,queue)queue=Queue()try:_thread.start_new_thread(scrape_article,('Thread 1','/wiki/Kevin_Bacon',queue,))_thread.start_new_thread(scrape_article,('Thread 2','/wiki/Monty_Python',queue,))_thread.start_new_thread(storage,(queue,))except:('Error: unable to start threads')while1:pass

This script creates three threads: two to scrape pages from Wikipedia in a random walk, and a third to store the collected data in a MySQL database. For more information about MySQL and data storage, see Chapter 6.

The threading Module

The Python _thread module is a fairly low-level module that allows you to micromanage your threads but doesn’t provide a lot of higher-level functions that make life easier. The threading module is a higher-level interface that allows you to use threads cleanly while still exposing all of the features of the underlying _thread.

For example, you can use static functions like enumerate to get a list of all active threads initialized through the threading module without needing to keep track of them yourself. The activeCount function, similarly, provides the total number of threads. Many functions from _thread are given more convenient or memorable names, like currentThread instead of get_ident to get the name of the current thread.

This is a simple threading example:

importthreadingimporttimedefprint_time(threadName,delay,iterations):start=int(time.time())foriinrange(0,iterations):time.sleep(delay)seconds_elapsed=str(int(time.time())-start)('{} {}'.format(seconds_elapsed,threadName))threading.Thread(target=print_time,args=('Fizz',3,33)).start()threading.Thread(target=print_time,args=('Buzz',5,20)).start()threading.Thread(target=print_time,args=('Counter',1,100)).start()

It produces the same “FizzBuzz” output as the previous simple _thread example.

One of the nice things about the threading module is the ease of creating local thread data that is unavailable to the other threads. This might be a nice feature if you have several threads, each scraping a different website, and each keeping track of its own local list of visited pages.

This local data can be created at any point within the thread function by calling threading.local():

importthreadingdefcrawler(url):data=threading.local()data.visited=[]# Crawl sitethreading.Thread(target=crawler,args=('http://brookings.edu')).start()

This solves the problem of race conditions happening between shared objects in threads. Whenever an object does not need to be shared it should not be, and should be kept in local thread memory. To safely share objects between threads the Queue from the previous section can still be used.

The threading module acts as a thread babysitter as sorts, and can be highly customized to define what that babysitting entails. The isAlive function by default looks to see if the thread is still active. It will be true until a thread completes crawling (or crashes).

Often, crawlers are designed to run for a very long time. The isAlive method can ensure that, if a thread crashes, it restarts:

threading.Thread(target=crawler)t.start()whileTrue:time.sleep(1)ifnott.isAlive():t=threading.Thread(target=crawler)t.start()

Other monitoring methods can be added by extending the threading.Thread object:

importthreadingimporttimeclassCrawler(threading.Thread):def__init__(self):threading.Thread.__init__(self)self.done=FalsedefisDone(self):returnself.donedefrun(self):time.sleep(5)self.done=TrueraiseException('Something bad happened!')t=Crawler()t.start()whileTrue:time.sleep(1)ift.isDone():('Done')breakifnott.isAlive():t=Crawler()t.start()

This new Crawler class contains an isDone method that can be used to check if the crawler is done crawling. This may be useful if there are some additional logging methods that need to be finished so the thread cannot close, but the bulk of the crawling work is done. In general, isDone can be replaced with some sort of status or progress measure—how many pages logged, or the current page, for example.

Any exceptions raised by Crawler.run will cause the class to be restarted until isDone is True and the program exits.

Extending threading.Thread in your crawler classes can improve their robustness and flexibility, as well as your ability to monitor any property of many crawlers at once.

Multiprocess Crawling

The Python Processing module creates new process objects that can be started and joined from the main process. The following code uses the FizzBuzz example from the section on threading processes to demonstrate.

frommultiprocessingimportProcessimporttimedefprint_time(threadName,delay,iterations):start=int(time.time())foriinrange(0,iterations):time.sleep(delay)seconds_elapsed=str(int(time.time())-start)(threadNameifthreadNameelseseconds_elapsed)processes=[]processes.append(Process(target=print_time,args=('Counter',1,100)))processes.append(Process(target=print_time,args=('Fizz',3,33)))processes.append(Process(target=print_time,args=('Buzz',5,20)))forpinprocesses:p.start()forpinprocesses:p.join()

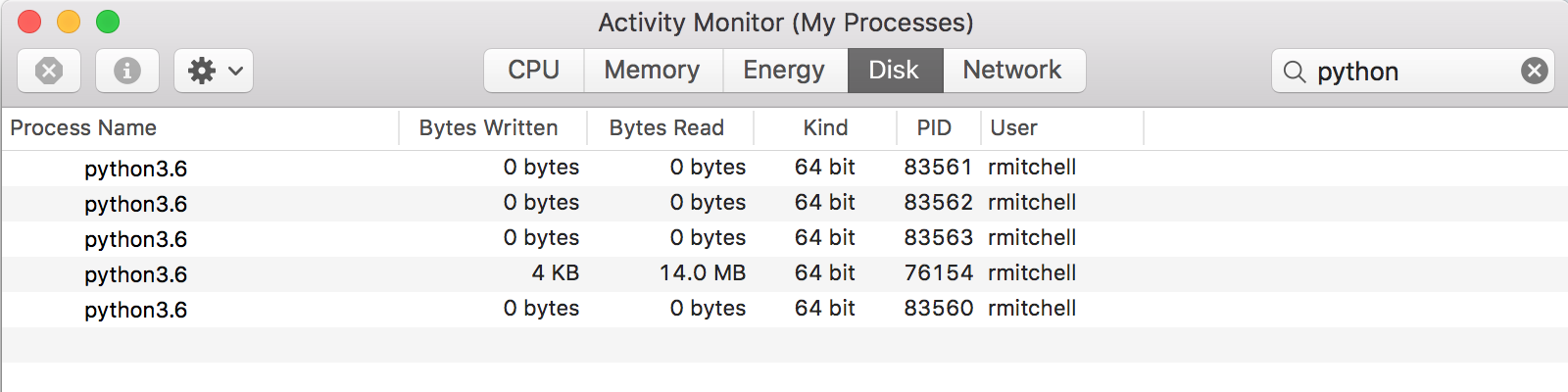

Remember that each process is treated as an individual independent program by the OS. If you view your processes through your OS’s activity monitor or task manager, you should see this reflected, as shown in Figure 16-1.

Figure 16-1. Five Python processes running while running FizzBuzz

The fourth process with PID 76154 is a running Jupyter notebook instance, which should appear if you are running this from the iPython notebook. The fifth process, 83560, is the main thread of execution, which starts up when the program is first executed. The PIDs are allocated by the OS sequentially. Unless you happen to have another program that quickly allocates a PID while the FizzBuzz script is running, you should see three more sequential PIDs—in this case 83561, 83562, and 83563.

These PIDs can also be found in code by using the os module:

importos...# prints the child PIDos.getpid()# prints the parent PIDos.getppid()

Each process in your program should print a different PID for the line os.getpid(), but will print the same parent PID on os.getppid().

Technically, there are a couple lines of code that are not needed for this particular program. If the ending join statement is not included

forpinprocesses:p.join()

the parent process will still end and terminate the child processes with it automatically. However, this joining is needed if you wish to execute any code after these child processes complete.

For example:

forpinprocesses:p.start()('Program complete')

If the join statement is not included, the output will be as follows:

Program complete 1 2

If the join statement is included, the program waits for each of the processes to finish before continuing:

forpinprocesses:p.start()forpinprocesses:p.join()('Program complete')

... Fizz 99 Buzz 100 Program complete

If you want to stop program execution prematurely, you can of course use Ctrl-C to terminate the parent process. The termination of the parent process will also terminate any child processes that have been spawned, so using Ctrl-C is safe to do without worrying about accidentally leaving processes running in the background.

Multiprocess Crawling

The multithreaded Wikipedia crawling example can be modified to use separate processes rather than separate threads:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportreimportrandomfrommultiprocessingimportProcessimportosimporttimevisited=[]defget_links(bs):('Getting links in {}'.format(os.getpid()))links=bs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$'))return[linkforlinkinlinksiflinknotinvisited]defscrape_article(path):visited.append(path)html=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(path))time.sleep(5)bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')title=bs.find('h1').get_text()('Scraping {} in process {}'.format(title,os.getpid()))links=get_links(bs)iflen(links)>0:newArticle=links[random.randint(0,len(links)-1)].attrs['href'](newArticle)scrape_article(newArticle)processes=[]processes.append(Process(target=scrape_article,args=('/wiki/Kevin_Bacon',)))processes.append(Process(target=scrape_article,args=('/wiki/Monty_Python',)))forpinprocesses:p.start()

Again, you are artificially slowing the process of the scraper by including a time.sleep(5) so that this can be used for example purposes without placing an unreasonably high load on Wikipedia’s servers.

Here, you are replacing the user-defined thread_name, passed around as an argument, with os.getpid(), which does not need to be passed as an argument and can be accessed at any point.

This produces output like the following:

Scraping Kevin Bacon in process 84275 Getting links in 84275 /wiki/Philadelphia Scraping Monty Python in process 84276 Getting links in 84276 /wiki/BBC Scraping BBC in process 84276 Getting links in 84276 /wiki/Television_Centre,_Newcastle_upon_Tyne Scraping Philadelphia in process 84275

Crawling in separate processes is, in theory, slightly faster than crawling in separate threads for two major reasons:

-

Processes are not subject to locking by the GIL and can execute the same lines of code and modify the same (really, separate instantiations of the same) object at the same time.

-

Processes can run on multiple CPU cores, which may provide speed advantages if each of your processes or threads is processor intensive.

However, these advantages come with one major disadvantage. In the preceding program, all found URLs are stored in a global visited list. When you were using multiple threads, this list was shared among all threads; and one thread, in the absence of a rare race condition, could not visit a page that had already been visited by another thread. However, each process now gets its own independent version of the visited list and is free to visit pages that have already been visited by other processes.

Communicating Between Processes

Processes operate in their own independent memory, which can cause problems if you want them to share information.

Modifying the previous example to print the current output of the visited list, you can see this principle in action:

defscrape_article(path):visited.append(path)("Process {} list is now: {}".format(os.getpid(),visited))

This results in output like the following:

Process 84552 list is now: ['/wiki/Kevin_Bacon'] Process 84553 list is now: ['/wiki/Monty_Python'] Scraping Kevin Bacon in process 84552 Getting links in 84552 /wiki/Desert_Storm Process 84552 list is now: ['/wiki/Kevin_Bacon', '/wiki/Desert_Storm'] Scraping Monty Python in process 84553 Getting links in 84553 /wiki/David_Jason Process 84553 list is now: ['/wiki/Monty_Python', '/wiki/David_Jason']

But there is a way to share information between processes on the same machine through two types of Python objects: queues and pipes.

A queue is similar to the threading queue seen previously. Information can be put into it by one process and removed by another process. After this information has been removed, it’s gone from the queue. Because queues are designed as a method of “temporary data transmission,” they’re not well suited to hold a static reference such as a “list of webpages that have already been visited.”

But what if this static list of web pages was replaced with some sort of a scraping delegator? The scrapers could pop off a task from one queue in the form of a path to scrape (for example, /wiki/Monty_Python) and in return, add a list of “found URLs” back onto a separate queue that would be processed by the scraping delegator so that only new URLs were added to the first task queue:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportreimportrandomfrommultiprocessingimportProcess,Queueimportosimporttimedeftask_delegator(taskQueue,urlsQueue):#Initialize with a task for each processvisited=['/wiki/Kevin_Bacon','/wiki/Monty_Python']taskQueue.put('/wiki/Kevin_Bacon')taskQueue.put('/wiki/Monty_Python')while1:# Check to see if there are new links in the urlsQueue# for processingifnoturlsQueue.empty():links=[linkforlinkinurlsQueue.get()iflinknotinvisited]forlinkinlinks:#Add new link to the taskQueuetaskQueue.put(link)defget_links(bs):links=bs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$'))return[link.attrs['href']forlinkinlinks]defscrape_article(taskQueue,urlsQueue):while1:whiletaskQueue.empty():#Sleep 100 ms while waiting for the task queue#This should be raretime.sleep(.1)path=taskQueue.get()html=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(path))time.sleep(5)bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')title=bs.find('h1').get_text()('Scraping {} in process {}'.format(title,os.getpid()))links=get_links(bs)#Send these to the delegator for processingurlsQueue.put(links)processes=[]taskQueue=Queue()urlsQueue=Queue()processes.append(Process(target=task_delegator,args=(taskQueue,urlsQueue,)))processes.append(Process(target=scrape_article,args=(taskQueue,urlsQueue,)))processes.append(Process(target=scrape_article,args=(taskQueue,urlsQueue,)))forpinprocesses:p.start()

Some structural differences exist between this scraper and the ones originally created. Rather than each process or thread following its own random walk from the starting point they were assigned, they work together to do a complete coverage crawl of the website. Each process can pull any “task” from the queue, not just links that they have found themselves.

Multiprocess Crawling—Another Approach

All of the approaches discussed for multithreaded and multiprocess crawling assume that you require some sort of “parental guidance” over the child threads and processes. You can start them all at once, you can end them all at once, and you can send messages or share memory between them.

But what if your scraper is designed in such a way that no guidance or communication is required? There may be very little reason to start going crazy with import _thread just yet.

For example, let’s say you want to crawl two similar websites in parallel. You have a crawler written that can crawl either of these websites, determined by a small configuration change or perhaps a command-line argument. There’s absolutely no reason you can’t simply do the following:

$ python my_crawler.py website1

$ python my_crawler.py website2

And voilà, you’ve just kicked off a multiprocess web crawler, while saving your CPU the overhead of keeping around a parent process to boot!

Of course, this approach has downsides. If you want to run two web crawlers on the same website in this way, you need some way of ensuring that they won’t accidentally start scraping the same pages. The solution might be to create a URL rule (“crawler 1 scrapes the blog pages, crawler 2 scrapes the product pages”) or divide the site in some way.

Alternatively, you may be able to handle this coordination through some sort of intermediate database. Before going to a new link, the crawler may make a request to the database to ask, “Has this page been crawled?” The crawler is using the database as an interprocess communication system. Of course, without careful consideration, this method may lead to race conditions or lag if the database connection is slow (likely only a problem if connecting to a remote database).

You may also find that this method isn’t quite as scalable. Using the Process module allows you to dynamically increase or decrease the number of processes crawling the site, or even storing data. Kicking them off by hand requires either a person physically running the script or a separate managing script (whether a bash script, a cron job, or something else) doing this.

However, this is a method I have used with great success in the past. For small, one-off projects, it is a great way to get a lot of information quickly, especially across multiple websites.