Chapter 9. Reading and Writing Natural Languages

So far, the data you have worked with generally has been in the form of numbers or countable values. In most cases, you’ve simply stored the data without conducting any analysis after the fact. This chapter attempts to tackle the tricky subject of the English language.1

How does Google know what you’re looking for when you type “cute kitten” into its Image Search? Because of the text that surrounds the cute kitten images. How does YouTube know to bring up a certain Monty Python sketch when you type “dead parrot” into its search bar? Because of the title and description text that accompanies each uploaded video.

In fact, even typing in terms such as “deceased bird monty python” immediately brings up the same “Dead Parrot” sketch, even though the page itself contains no mention of the words “deceased” or “bird.” Google knows that a “hot dog” is a food and that a “boiling puppy” is an entirely different thing. How? It’s all statistics!

Although you might not think that text analysis has anything to do with your project, understanding the concepts behind it can be extremely useful for all sorts of machine learning, as well as the more general ability to model real-world problems in probabilistic and algorithmic terms.

For instance, the Shazam music service can identify audio as containing a certain song recording, even if that audio contains ambient noise or distortion. Google is working on automatically captioning images based on nothing but the image itself.2 By comparing known images of, say, hot dogs to other images of hot dogs, the search engine can gradually learn what a hot dog looks like and observe these patterns in additional images it is shown.

Summarizing Data

In Chapter 8, you looked at breaking up text content into n-grams, or sets of phrases that are n words in length. At a basic level, this can be used to determine which sets of words and phrases tend to be most commonly used in a section of text. In addition, it can be used to create natural-sounding data summaries by going back to the original text and extracting sentences around some of these most popular phrases.

One piece of sample text you’ll be using to do this is the inauguration speech of the ninth president of the United States, William Henry Harrison. Harrison’s presidency sets two records in the history of the office: one for the longest inauguration speech, and another for the shortest time in office, 32 days.

You’ll use the full text of this speech as the source for many of the code samples in this chapter.

Slightly modifying the n-gram used to find code in Chapter 8, you can produce code that looks for sets of 2-grams and returns a Counter object with all 2-grams:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportreimportstringfromcollectionsimportCounterdefcleanSentence(sentence):sentence=sentence.split(' ')sentence=[word.strip(string.punctuation+string.whitespace)forwordinsentence]sentence=[wordforwordinsentenceiflen(word)>1or(word.lower()=='a'orword.lower()=='i')]returnsentencedefcleanInput(content):content=content.upper()content=re.sub('\n',' ',content)content=bytes(content,"UTF-8")content=content.decode("ascii","ignore")sentences=content.split('. ')return[cleanSentence(sentence)forsentenceinsentences]defgetNgramsFromSentence(content,n):output=[]foriinrange(len(content)-n+1):output.append(content[i:i+n])returnoutputdefgetNgrams(content,n):content=cleanInput(content)ngrams=Counter()ngrams_list=[]forsentenceincontent:newNgrams=[' '.join(ngram)forngramingetNgramsFromSentence(sentence,2)]ngrams_list.extend(newNgrams)ngrams.update(newNgrams)return(ngrams)content=str(urlopen('http://pythonscraping.com/files/inaugurationSpeech.txt').read(),'utf-8')ngrams=getNgrams(content,2)(ngrams)

The output produces, in part:

Counter({'OF THE': 213, 'IN THE': 65, 'TO THE': 61, 'BY THE': 41,

'THE CONSTITUTION': 34, 'OF OUR': 29, 'TO BE': 26, 'THE PEOPLE': 24,

'FROM THE': 24, 'THAT THE': 23,...

Of these 2-grams, “the constitution” seems like a reasonably popular subject in the speech, but “of the,” “in the,” and “to the” don’t seem especially noteworthy. How can you automatically get rid of unwanted words in an accurate way?

Fortunately, there are people out there who carefully study the differences between “interesting” words and “uninteresting” words, and their work can help us do just that. Mark Davies, a linguistics professor at Brigham Young University, maintains the Corpus of Contemporary American English, a collection of over 450 million words from the last decade or so of popular American publications.

The list of 5,000 most frequently found words is available for free, and fortunately, this is far more than enough to act as a basic filter to weed out the most common 2-grams. Just the first 100 words vastly improves the results, with the addition of an isCommon function:

defisCommon(ngram):commonWords=['THE','BE','AND','OF','A','IN','TO','HAVE','IT','I','THAT','FOR','YOU','HE','WITH','ON','DO','SAY','THIS','THEY','IS','AN','AT','BUT','WE','HIS','FROM','THAT','NOT','BY','SHE','OR','AS','WHAT','GO','THEIR','CAN','WHO','GET','IF','WOULD','HER','ALL','MY','MAKE','ABOUT','KNOW','WILL','AS','UP','ONE','TIME','HAS','BEEN','THERE','YEAR','SO','THINK','WHEN','WHICH','THEM','SOME','ME','PEOPLE','TAKE','OUT','INTO','JUST','SEE','HIM','YOUR','COME','COULD','NOW','THAN','LIKE','OTHER','HOW','THEN','ITS','OUR','TWO','MORE','THESE','WANT','WAY','LOOK','FIRST','ALSO','NEW','BECAUSE','DAY','MORE','USE','NO','MAN','FIND','HERE','THING','GIVE','MANY','WELL']forwordinngram:ifwordincommonWords:returnTruereturnFalse

This produces the following 2-grams that were found more than twice in the text body:

Counter({'UNITED STATES': 10, 'EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT': 4,

'GENERAL GOVERNMENT': 4, 'CALLED UPON': 3, 'CHIEF MAGISTRATE': 3,

'LEGISLATIVE BODY': 3, 'SAME CAUSES': 3, 'GOVERNMENT SHOULD': 3,

'WHOLE COUNTRY': 3,...

Appropriately enough, the first two items in the list are “United States” and “executive department,” which you would expect for a presidential inauguration speech.

It’s important to note that you are using a list of common words from relatively modern times to filter the results, which might not be appropriate given that the text was written in 1841. However, because you’re using only the first 100 or so words on the list—which you can assume are more stable over time than, say, the last 100 words—and you appear to be getting satisfactory results, you can likely save yourself the effort of tracking down or creating a list of the most common words from 1841 (although such an effort might be interesting).

Now that some key topics have been extracted from the text, how does this help you write text summaries? One way is to search for the first sentence that contains each “popular” n-gram, the theory being that the first instance will yield a satisfactory overview of the body of the content. The first five most popular 2-grams yield these bullet points:

-

The Constitution of the United States is the instrument containing this grant of power to the several departments composing the Government.

-

Such a one was afforded by the executive department constituted by the Constitution.

-

The General Government has seized upon none of the reserved rights of the States.

-

Called from a retirement which I had supposed was to continue for the residue of my life to fill the chief executive office of this great and free nation, I appear before you, fellow-citizens, to take the oaths which the constitution prescribes as a necessary qualification for the performance of its duties; and in obedience to a custom coeval with our government and what I believe to be your expectations I proceed to present to you a summary of the principles which will govern me in the discharge of the duties which I shall be called upon to perform.

-

The presses in the necessary employment of the Government should never be used to “clear the guilty or to varnish crime.”

Sure, it might not be published in CliffsNotes any time soon, but considering that the original document was 217 sentences in length, and the fourth sentence (“Called from a retirement...”) condenses the main subject down fairly well, it’s not too bad for a first pass.

With longer blocks of text, or more varied text, it may be worth looking at 3-grams or even 4-grams when retrieving the “most important” sentences of a passage. In this case, only one 3-gram is used multiple times and that is “exclusive metallic currency”—hardly a defining phrase for a presidential inauguration speech. With longer passages, using 3-grams may be appropriate.

Another approach is to look for sentences that contain the most popular n-grams. These will, of course, tend to be longer sentences, so if that becomes a problem, you can look for sentences with the highest percentage of words that are popular n-grams, or create a scoring metric of your own, combining several techniques.

Markov Models

You might have heard of Markov text generators. They’ve become popular for entertainment purposes, as in the “That can be my next tweet!” app, as well as their use for generating real-sounding spam emails to fool detection systems.

All of these text generators are based on the Markov model, which is often used to analyze large sets of random events, where one discrete event is followed by another discrete event with a certain probability.

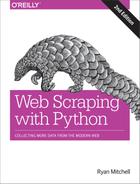

For example, you might build a Markov model of a weather system, as illustrated in Figure 9-1.

Figure 9-1. Markov model describing a theoretical weather system

In this model, each sunny day has a 70% chance of the following day also being sunny, with a 20% chance of the following day being cloudy with a mere 10% chance of rain. If the day is rainy, there is a 50% chance of rain the following day, a 25% chance of sun, and a 25% chance of clouds.

You might note several properties in this Markov model:

-

All percentages leading away from any one node must add up to exactly 100%. No matter how complicated the system, there must always be a 100% chance that it can lead somewhere else in the next step.

-

Although there are only three possibilities for the weather at any given time, you can use this model to generate an infinite list of weather states.

-

Only the state of the current node you are on influences where you will go to next. If you’re on the Sunny node, it doesn’t matter if the preceding 100 days were sunny or rainy—the chances of sun the next day are exactly the same: 70%.

-

It might be more difficult to reach some nodes than others. The math behind this is reasonably complicated, but it should be fairly easy to see that Rainy (with less than “100%” worth of arrows pointing toward it) is a much less likely state to reach in this system, at any given point in time, than Sunny or Cloudy.

Obviously, this is a simple system, and Markov models can grow arbitrarily large. Google’s page-rank algorithm is based partly on a Markov model, with websites represented as nodes and inbound/outbound links represented as connections between nodes. The “likelihood” of landing on a particular node represents the relative popularity of the site. That is, if our weather system represented an extremely small internet, “rainy” would have a low page rank, while “cloudy” would have a high page rank.

With all of this in mind, let’s bring it back down to a more concrete example: analyzing and writing text.

Again using the inauguration speech of William Henry Harrison analyzed in the previous example, you can write the following code that generates arbitrarily long Markov chains (with the chain length set to 100) based on the structure of its text:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfromrandomimportrandintdefwordListSum(wordList):sum=0forword,valueinwordList.items():sum+=valuereturnsumdefretrieveRandomWord(wordList):randIndex=randint(1,wordListSum(wordList))forword,valueinwordList.items():randIndex-=valueifrandIndex<=0:returnworddefbuildWordDict(text):# Remove newlines and quotestext=text.replace('\n',' ');text=text.replace('"','');# Make sure punctuation marks are treated as their own "words,"# so that they will be included in the Markov chainpunctuation=[',','.',';',':']forsymbolinpunctuation:text=text.replace(symbol,' {} '.format(symbol));words=text.split(' ')# Filter out empty wordswords=[wordforwordinwordsifword!='']wordDict={}foriinrange(1,len(words)):ifwords[i-1]notinwordDict:# Create a new dictionary for this wordwordDict[words[i-1]]={}ifwords[i]notinwordDict[words[i-1]]:wordDict[words[i-1]][words[i]]=0wordDict[words[i-1]][words[i]]+=1returnwordDicttext=str(urlopen('http://pythonscraping.com/files/inaugurationSpeech.txt').read(),'utf-8')wordDict=buildWordDict(text)#Generate a Markov chain of length 100length=100chain=['I']foriinrange(0,length):newWord=retrieveRandomWord(wordDict[chain[-1]])chain.append(newWord)(' '.join(chain))

The output of this code changes every time it is run, but here’s an example of the uncannily nonsensical text it will generate:

I sincerely believe in Chief Magistrate to make all necessary sacrifices and oppression of the remedies which we may have occurred to me in the arrangement and disbursement of the democratic claims them , consolatory to have been best political power in fervently commending every other addition of legislation , by the interests which violate that the Government would compare our aboriginal neighbors the people to its accomplishment . The latter also susceptible of the Constitution not much mischief , disputes have left to betray . The maxim which may sometimes be an impartial and to prevent the adoption or

So what’s going on in the code?

The function buildWordDict takes in the string of text, which was retrieved from the internet. It then does some cleaning and formatting, removing quotes and putting spaces around other punctuation so it is effectively treated as a separate word. After this, it builds a two-dimensional dictionary—a dictionary of dictionaries—that has the following form:

{word_a:{word_b:2,word_c:1,word_d:1},word_e:{word_b:5,word_d:2},...}

In this example dictionary, “word_a” was found four times, two instances of which were followed by “word_b,” one instance followed by “word_c,” and one instance followed by “word_d.” “Word_e” was followed seven times, five times by “word_b” and twice by “word_d.”

If we were to draw a node model of this result, the node representing word_a would have a 50% arrow pointing toward “word_b” (which followed it two out of four times), a 25% arrow pointing toward “word_c,” and a 25% arrow pointing toward “word_d.”

After this dictionary is built up, it can be used as a lookup table to see where to go next, no matter which word in the text you happen to be on.3 Using the sample dictionary of dictionaries, you might currently be on “word_e,” which means that you’ll pass the dictionary {word_b : 5, word_d: 2} to the retrieveRandomWord function. This function in turn retrieves a random word from the dictionary, weighted by the number of times it occurs.

By starting with a random starting word (in this case, the ubiquitous “I”), you can traverse through the Markov chain easily, generating as many words as you like.

These Markov chains tend to improve in their “realism” as more text is collected, especially from sources with similar writing styles. Although this example used 2-grams to create the chain (where the previous word predicts the next word) 3-grams or higher-order n-grams can be used, where two or more words predict the next word.

Although entertaining, and a great use for megabytes of text that you might have accumulated during web scraping, applications like these can make it difficult to see the practical side of Markov chains. As mentioned earlier in this section, Markov chains model how websites link from one page to the next. Large collections of these links as pointers can form weblike graphs that are useful to store, track, and analyze. In this way, Markov chains form the foundation for both how to think about web crawling, and how your web crawlers can think.

Six Degrees of Wikipedia: Conclusion

In Chapter 3, you created a scraper that collects links from one Wikipedia article to the next, starting with the article on Kevin Bacon, and in Chapter 6, stored those links in a database. Why am I bringing it up again? Because it turns out the problem of choosing a path of links that starts on one page and ends up on the target page (i.e., finding a string of pages between https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_Bacon and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Idle) is the same as finding a Markov chain where both the first word and last word are defined.

These sorts of problems are directed graph problems, where A → B does not necessarily mean that B → A. The word “football” might often be followed by the word “player,” but you’ll find that the word “player” is much less often followed by the word “football.” Although Kevin Bacon’s Wikipedia article links to the article on his home city, Philadelphia, the article on Philadelphia does not reciprocate by linking back to him.

In contrast, the original Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon game is an undirected graph problem. If Kevin Bacon starred in Flatliners with Julia Roberts, then Julia Roberts necessarily starred in Flatliners with Kevin Bacon, so the relationship goes both ways (it has no “direction”). Undirected graph problems tend to be less common in computer science than directed graph problems, and both are computationally difficult to solve.

Although much work has been done on these sorts of problems and multitudes of variations on them, one of the best and most common ways to find shortest paths in a directed graph—and thus find paths between the Wikipedia article on Kevin Bacon and all other Wikipedia articles—is through a breadth-first search.

A breadth-first search is performed by first searching all links that link directly to the starting page. If those links do not contain the target page (the page you are searching for), then a second level of links—pages that are linked by a page that is linked by the starting page—is searched. This process continues until either the depth limit (6 in this case) is reached or the target page is found.

A complete solution to the breadth-first search, using a table of links as described in Chapter 6, is as follows:

importpymysqlconn=pymysql.connect(host='127.0.0.1',unix_socket='/tmp/mysql.sock',user='',passwd='',db='mysql',charset='utf8')cur=conn.cursor()cur.execute('USE wikipedia')defgetUrl(pageId):cur.execute('SELECT url FROM pages WHERE id =%s',(int(pageId)))returncur.fetchone()[0]defgetLinks(fromPageId):cur.execute('SELECT toPageId FROM links WHERE fromPageId =%s',(int(fromPageId)))ifcur.rowcount==0:return[]return[x[0]forxincur.fetchall()]defsearchBreadth(targetPageId,paths=[[1]]):newPaths=[]forpathinpaths:links=getLinks(path[-1])forlinkinlinks:iflink==targetPageId:returnpath+[link]else:newPaths.append(path+[link])returnsearchBreadth(targetPageId,newPaths)nodes=getLinks(1)targetPageId=28624pageIds=searchBreadth(targetPageId)forpageIdinpageIds:(getUrl(pageId))

getUrl is a helper function that retrieves URLs from the database given a page ID. Similarly, getLinks takes a fromPageId representing the integer ID for the current page, and fetches a list of all integer IDs for pages it links to.

The main function, searchBreadth, works recursively to construct a list of all possible paths from the search page and stops when it finds a path that has reached the target page:

-

It starts with a single path,

[1], representing a path in which the user stays on the target page with the ID 1 (Kevin Bacon) and follows no links. -

For each path in the list of paths (in the first pass, there is only one path, so this step is brief), it gets all of the links that link out from the page represented by the last page in the path.

-

For each of these outbound links, it checks whether they match the

targetPageId. If there’s a match, that path is returned. -

If there’s no match, a new path is added to a new list of (now longer) paths, consisting of the old path + the new outbound page link.

-

If the

targetPageIdis not found at this level at all, a recursion occurs andsearchBreadthis called with the sametargetPageIdand a new, longer, list of paths.

After the list of page IDs containing a path between the two pages is found, each ID is resolved to its actual URL and printed.

The output for searching for a link between the page on Kevin Bacon (page ID 1 in this database) and the page on Eric Idle (page ID 28624 in this database) is as follows:

/wiki/Kevin_Bacon /wiki/Primetime_Emmy_Award_for_Outstanding_Lead_Actor_in_a_ Miniseries_or_a_Movie /wiki/Gary_Gilmore /wiki/Eric_Idle

This translates into the relationship of links: Kevin Bacon → Primetime Emmy Award → Gary Gilmore → Eric Idle.

In addition to solving Six Degree problems and modeling which words tend to follow which other words in sentences, directed and undirected graphs can be used to model a variety of situations encountered in web scraping. Which websites link to which other websites? Which research papers cite which other research papers? Which products tend to be shown with which other products on a retail site? What is the strength of this link? Is the link reciprocal?

Recognizing these fundamental types of relationships can be extremely helpful for making models, visualizations, and predictions based on scraped data.

Natural Language Toolkit

So far, this chapter has focused primarily on the statistical analysis of words in bodies of text. Which words are most popular? Which words are unusual? Which words are likely to come after which other words? How are they grouped together? What you are missing is understanding, to the extent that you can, what the words represent.

The Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) is a suite of Python libraries designed to identify and tag parts of speech found in natural English text. Its development began in 2000, and over the past 15 years, dozens of developers around the world have contributed to the project. Although the functionality it provides is tremendous (entire books are devoted to NLTK), this section focuses on just a few of its uses.

Installation and Setup

The nltk module can be installed in the same way as other Python modules, either by downloading the package through the NLTK website directly or by using any number of third-party installers with the keyword “nltk.” For complete installation instructions, see the NLTK website.

After installing the module, it’s a good idea to download its preset text repositories so you can try the features more easily. Type this on the Python command line:

>>>importnltk>>>nltk.download()

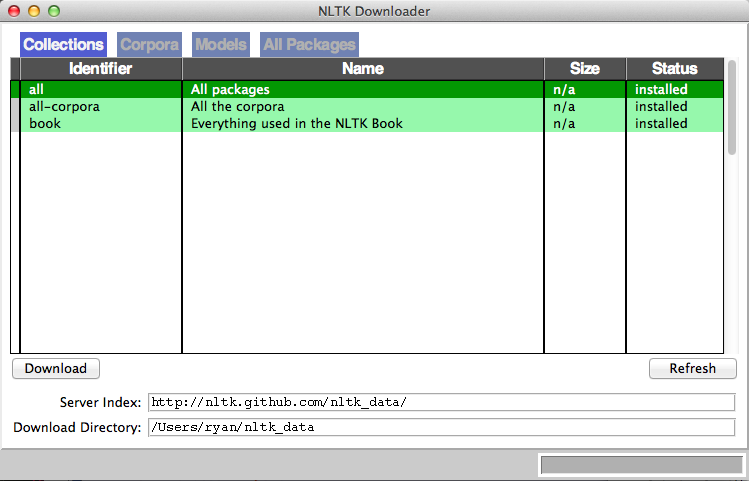

This opens the NLTK Downloader (Figure 9-2).

I recommend installing all of the available packages when first trying out the NLTK corpus. You can easily uninstall packages at any time.

Figure 9-2. The NLTK Downloader lets you browse and download optional packages and text libraries associated with the nltk module

Statistical Analysis with NLTK

NLTK is great for generating statistical information about word counts, word frequency, and word diversity in sections of text. If all you need is a relatively straightforward calculation (e.g., the number of unique words used in a section of text), importing nltk might be overkill—it’s a large module. However, if you need to do relatively extensive analysis of a text, you have functions at your fingertips that will give you just about any metric you want.

Analysis with NLTK always starts with the Text object. Text objects can be created from simple Python strings in the following way:

fromnltkimportword_tokenizefromnltkimportTexttokens=word_tokenize('Here is some not very interesting text')text=Text(tokens)

The input for the word_tokenize function can be any Python text string. If you don’t have any long strings handy but still want to play around with the features, NLTK has quite a few books already built into the library, which can be accessed using the import function:

fromnltk.bookimport*

This loads the nine books:

*** Introductory Examples for the NLTK Book *** Loading text1, ..., text9 and sent1, ..., sent9 Type the name of the text or sentence to view it. Type: 'texts()' or 'sents()' to list the materials. text1: Moby Dick by Herman Melville 1851 text2: Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen 1811 text3: The Book of Genesis text4: Inaugural Address Corpus text5: Chat Corpus text6: Monty Python and the Holy Grail text7: Wall Street Journal text8: Personals Corpus text9: The Man Who Was Thursday by G . K . Chesterton 1908

You will be working with text6, “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” (the screenplay for the 1975 movie), in all of the following examples.

Text objects can be manipulated much like normal Python arrays, as if they were an array containing words of the text. Using this property, you can count the number of unique words in a text and compare it against the total number of words (remember that a Python set holds only unique values):

>>>len(text6)/len(set(text6))7.833333333333333

The preceding shows that each word in the script was used about eight times on average. You can also put the text into a frequency distribution object to determine some of the most common words and the frequencies for various words:

>>>fromnltkimportFreqDist>>>fdist=FreqDist(text6)>>>fdist.most_common(10)[(':',1197),('.',816),('!',801),(',',731),("'",421),('[',319),(']',312),('the',299),('I',255),('ARTHUR',225)]>>>fdist["Grail"]34

Because this is a screenplay, some artifacts of how it is written can pop up. For instance, “ARTHUR” in all caps crops up frequently because it appears before each of King Arthur’s lines in the script. In addition, a colon (:) appears before every single line, acting as a separator between the name of the character and the character’s line. Using this fact, we can see that there are 1,197 lines in the movie!

What we have called 2-grams in previous chapters, NLTK refers to as bigrams (from time to time, you might also hear 3-grams referred to as trigrams, but I prefer 2-gram and 3-gram rather than bigram or trigram). You can create, search, and list 2-grams extremely easily:

>>>fromnltkimportbigrams>>>bigrams=bigrams(text6)>>>bigramsDist=FreqDist(bigrams)>>>bigramsDist[('Sir','Robin')]18

To search for the 2-grams “Sir Robin,” you need to break it into the tuple (“Sir”, “Robin”), to match the way the 2-grams are represented in the frequency distribution. There is also a trigrams module that works in the exact same way. For the general case, you can also import the ngrams module:

>>>fromnltkimportngrams>>>fourgrams=ngrams(text6,4)>>>fourgramsDist=FreqDist(fourgrams)>>>fourgramsDist[('father','smelt','of','elderberries')]1

Here, the ngrams function is called to break a text object into n-grams of any size, governed by the second parameter. In this case, you’re breaking the text into 4-grams. Then, you can demonstrate that the phrase “father smelt of elderberries” occurs in the screenplay exactly once.

Frequency distributions, text objects, and n-grams also can be iterated through and operated on in a loop. The following prints out all 4-grams that begin with the word “coconut,” for instance:

fromnltk.bookimport*fromnltkimportngramsfourgrams=ngrams(text6,4)forfourgraminfourgrams:iffourgram[0]=='coconut':(fourgram)

The NLTK library has a vast array of tools and objects designed to organize, count, sort, and measure large swaths of text. Although we’ve barely scratched the surface of their uses, most of these tools are well designed and operate rather intuitively for someone familiar with Python.

Lexicographical Analysis with NLTK

So far, you’ve compared and categorized all the words you’ve encountered based only on the value they represent by themselves. There is no differentiation between homonyms or the context in which the words are used.

Although some people might be tempted to dismiss homonyms as rarely problematic, you might be surprised at how frequently they crop up. Most native English speakers probably don’t often register that a word is a homonym, much less consider that it might be confused for another word in a different context.

“He was objective in achieving his objective of writing an objective philosophy, primarily using verbs in the objective case” is easy for humans to parse but might make a web scraper think the same word is being used four times and cause it to simply discard all the information about the meaning behind each word.

In addition to sussing out parts of speech, being able to distinguish a word being used in one way versus another might be useful. For example, you might want to look for company names made up of common English words, or analyze someone’s opinions about a company. “ACME Products is good” and “ACME Products is not bad” can have the same basic meaning, even if one sentence uses “good” and the other uses “bad.”

In addition to measuring language, NLTK can assist in finding meaning in the words based on context and its own sizable dictionaries. At a basic level, NLTK can identify parts of speech:

>>>fromnltk.bookimport*>>>fromnltkimportword_tokenize>>>text=word_tokenize('Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords'\'is no basis for a system of government.')>>>fromnltkimportpos_tag>>>pos_tag(text)[('Strange','NNP'),('women','NNS'),('lying','VBG'),('in','IN'),('ponds','NNS'),('distributing','VBG'),('swords','NNS'),('is','VBZ'),('no','DT'),('basis','NN'),('for','IN'),('a','DT'),('system','NN'),('of','IN'),('government','NN'),('.','.')]

Each word is separated into a tuple containing the word and a tag identifying the part of speech (see the preceding sidebar for more information about these tags). Although this might seem like a straightforward lookup, the complexity needed to perform the task correctly becomes apparent with the following example:

>>>text=word_tokenize('The dust was thick so he had to dust')>>>pos_tag(text)[('The','DT'),('dust','NN'),('was','VBD'),('thick','JJ'),('so','RB'),('he','PRP'),('had','VBD'),('to','TO'),('dust','VB')]

Notice that the word “dust” is used twice in the sentence: once as a noun, and again as a verb. NLTK identifies both usages correctly, based on their context in the sentence. NLTK identifies parts of speech by using a context-free grammar defined by the English language. Context-free grammars are sets of rules that define which things are allowed to follow which other things in ordered lists. In this case, they define which parts of speech are allowed to follow which other parts of speech. Whenever an ambiguous word such as “dust” is encountered, the rules of the context-free grammar are consulted, and an appropriate part of speech that follows the rules is selected.

What’s the point of knowing whether a word is a verb or a noun in a given context? It might be neat in a computer science research lab, but how does it help with web scraping?

A common problem in web scraping deals with search. You might be scraping text off a site and want to be able to search it for instances of the word “google,” but only when it’s being used as a verb, not a proper noun. Or you might be looking only for instances of the company Google and don’t want to rely on people’s correct use of capitalization in order to find those instances. Here, the pos_tag function can be extremely useful:

fromnltkimportword_tokenize,sent_tokenize,pos_tagsentences=sent_tokenize('Google is one of the best companies in the world.'\' I constantly google myself to see what I\'m up to.')nouns=['NN','NNS','NNP','NNPS']forsentenceinsentences:if'google'insentence.lower():taggedWords=pos_tag(word_tokenize(sentence))forwordintaggedWords:ifword[0].lower()=='google'andword[1]innouns:(sentence)

This prints only sentences that contain the word “google” (or “Google”) as some sort of a noun, not a verb. Of course, you could be more specific and demand that only instances of Google tagged with “NNP” (a proper noun) are printed, but even NLTK makes mistakes at times, and it can be good to leave yourself a little wiggle room, depending on the application.

Much of the ambiguity of natural language can be resolved using NLTK’s pos_tag function. By searching text not just for instances of your target word or phrase but instances of your target word or phrase plus its tag, you can greatly increase the accuracy and effectiveness of your scraper’s searches.

Additional Resources

Processing, analyzing, and understanding natural language by machine is one of the most difficult tasks in computer science, and countless volumes and research papers have been written on the subject. I hope that the coverage here will inspire you to think beyond conventional web scraping, or at least give some initial direction about where to begin when undertaking a project that requires natural language analysis.

Many excellent resources are available on introductory language processing and Python’s Natural Language Toolkit. In particular, Steven Bird, Ewan Klein, and Edward Loper’s book Natural Language Processing with Python (O’Reilly) presents both a comprehensive and introductory approach to the topic.

In addition, James Pustejovsky and Amber Stubbs’ Natural Language Annotations for Machine Learning (O’Reilly) provides a slightly more advanced theoretical guide. You’ll need knowledge of Python to implement the lessons; the topics covered work perfectly with Python’s Natural Language Toolkit.

1 Although many of the techniques described in this chapter can be applied to all or most languages, it’s okay for now to focus on natural language processing in English only. Tools such as Python’s Natural Language Toolkit, for example, focus on English. Fifty-six percent of the internet is still in English (with German following at a mere 6%, according to W3Techs). But who knows? English’s hold on the majority of the internet will almost certainly change in the future, and further updates may be necessary in the next few years.

2 Oriol Vinyals et al, “A Picture Is Worth a Thousand (Coherent) Words: Building a Natural Description of Images”, Google Research Blog, November 17, 2014.

3 The exception is the last word in the text, because nothing follows the last word. In our example text, the last word is a period (.), which is convenient because it has 215 other occurrences in the text and so does not represent a dead-end. However, in real-world implementations of the Markov generator, the last word of the text might be something you need to account for.