Chapter 7. Reading Documents

It is tempting to think of the internet primarily as a collection of text-based websites interspersed with newfangled web 2.0 multimedia content that can mostly be ignored for the purposes of web scraping. However, this ignores what the internet most fundamentally is: a content-agnostic vehicle for transmitting files.

Although the internet has been around in some form or another since the late 1960s, HTML didn’t debut until 1992. Until then, the internet consisted mostly of email and file transmission; the concept of web pages as we know them today didn’t exist. In other words, the internet is not a collection of HTML files. It is a collection of many types of documents, with HTML files often being used as a frame to showcase them. Without being able to read a variety of document types, including text, PDF, images, video, email, and more, we are missing out on a huge part of the available data.

This chapter covers dealing with documents, whether you’re downloading them to a local folder or reading them and extracting data. You’ll also take a look at dealing with various types of text encoding, which can make it possible to even read foreign-language HTML pages.

Document Encoding

A document’s encoding tells applications—whether they are your computer’s operating system or your own Python code—how to read it. This encoding can usually be deduced from its file extension, although this file extension is not mandated by its encoding. I could, for example, save myImage.jpg as myImage.txt with no problems—at least until my text editor tried to open it. Fortunately, this situation is rare, and a document’s file extension is usually all you need to know in order to read it correctly.

On a fundamental level, all documents are encoded in 0s and 1s. On top of that, encoding algorithms define things such as “how many bits per character” or “how many bits represent the color for each pixel” (in the case of image files). On top of that, you might have a layer of compression, or some space-reducing algorithm, as is the case with PNG files.

Although dealing with non-HTML files might seem intimidating at first, rest assured that with the right library, Python will be properly equipped to deal with any format of information you want to throw at it. The only difference between a text file, a video file, and an image file is how their 0s and 1s are interpreted. This chapter covers several commonly encountered types of files: text, CSV, PDFs, and Word documents.

Notice that these are all, fundamentally, files that store text. For information about working with images, I recommend that you read through this chapter in order to get used to working with and storing different types of files, and then head to Chapter 13 for more information on image processing!

Text

It is somewhat unusual to have files stored as plain text online, but it is popular among bare-bones or old-school sites to have large repositories of text files. For example, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) stores all of its published documents as HTML, PDF, and text files (see https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc1149.txt as an example). Most browsers will display these text files just fine, and you should be able to scrape them with no problem.

For most basic text documents, such as the practice file located at http://www.pythonscraping.com/pages/warandpeace/chapter1.txt, you can use the following method:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopentextPage=urlopen('http://www.pythonscraping.com/'\'pages/warandpeace/chapter1.txt')(textPage.read())

Normally, when you retrieve a page using urlopen, you turn it into a BeautifulSoup object in order to parse the HTML. In this case, you can read the page directly. Turning it into a BeautifulSoup object, while perfectly possible, would be counterproductive—there’s no HTML to parse, so the library would be useless. Once the text file is read in as a string, you merely have to analyze it as you would any other string read into Python. The disadvantage here, of course, is that you don’t have the ability to use HTML tags as context clues, pointing you in the direction of the text you actually need, versus the text you don’t want. This can present a challenge when you’re trying to extract certain information from text files.

Text Encoding and the Global Internet

Remember earlier when I said a file extension was all you needed to read a file correctly? Well, strangely enough, that rule doesn’t apply to the most basic of all documents: the .txt file.

Nine times out of 10, reading in text by using the previously described methods will work just fine. However, dealing with text on the internet can be a tricky business. Next, we’ll cover the basics of English and foreign-language encoding, from ASCII to Unicode to ISO, and how to deal with them.

A history of text encoding

ASCII was first developed in the 1960s, when bits were expensive and there was no reason to encode anything besides the Latin alphabet and a few punctuation characters. For this reason, only 7 bits were used to encode a total of 128 capitals, lowercase letters, and punctuation. Even with all that creativity, they were still left with 33 non-printing characters, some of which were used, replaced, and/or became obsolete as technologies changed over the years. Plenty of space for everyone, right?

As any programmer knows, 7 is a strange number. It’s not a nice power of 2, but it’s temptingly close. Computer scientists in the 1960s fought over whether an extra bit should be added for the convenience of having a nice round number versus the practicality of files requiring less storage space. In the end, 7 bits won. However, in modern computing, each 7-bit sequence is padded with an extra 0 at the beginning,1 leaving us with the worst of both worlds—14% larger files, and the lack of flexibility of only 128 characters.

In the early 1990s, people realized that more languages than just English existed, and that it would be really nice if computers could display them. A nonprofit named The Unicode Consortium attempted to bring about a universal text encoder by establishing encodings for every character that needs to be used in any text document, in any language. The goal was to include everything from the Latin alphabet this book is written in, to Cyrillic (кириллица), Chinese pictograms (象形), math and logic symbols (⨊, ≥), and even emoticons and miscellaneous symbols, such as the biohazard sign (☣) and peace symbol (☮).

The resulting encoder, as you might already know, was dubbed UTF-8, which stands for, confusingly, “Universal Character Set—Transformation Format 8 bit.” The 8 bit here refers, not to the size of every character, but to the smallest size that a character requires to be displayed.

The actual size of a UTF-8 character is flexible. They can range from 1 byte to 4 bytes, depending on where they are placed in the list of possible characters (more-popular characters are encoded with fewer bytes, more-obscure ones require more bytes).

How is this flexible encoding achieved? The use of 7 bits with an eventual useless leading 0 looked like a design flaw in ASCII at first, but proved to be a huge advantage for UTF-8. Because ASCII was so popular, Unicode decided to take advantage of this leading 0 bit by declaring all bytes starting with a 0 to indicate that only one byte is used in the character, and making the two encoding schemes for ASCII and UTF-8 identical. Therefore, the following characters are valid in both UTF-8 and ASCII:

01000001 - A 01000010 - B 01000011 - C

And the following characters are valid only in UTF-8, and will be rendered as nonprintable if the document is interpreted as an ASCII document:

11000011 10000000 - À 11000011 10011111 - ß 11000011 10100111 - ç

In addition to UTF-8, other UTF standards exist, such as UTF-16, UTF-24, and UTF-32, although documents encoded in these formats are rarely encountered except in unusual circumstances, which are outside the scope of this book.

While this original “design flaw” of ASCII had a major advantage for UTF-8, the disadvantage has not entirely gone away. The first 8 bits of information in each character can still encode only 128 characters, and not a full 256. In a UTF-8 character requiring multiple bytes, additional leading bits are spent, not on character encoding, but on check bits used to prevent corruption. Of the 32 (8 x 4) bits in 4-byte characters, only 21 bits are used for character encoding, for a total of 2,097,152 possible characters, of which, 1,114,112 are currently allocated.

The problem with all universal language-encoding standards, of course, is that any document written in a single foreign language may be much larger than it has to be. Although your language might consist only of 100 or so characters, you will need 16 bits for each character rather than just 8 bits, as is the case for the English-specific ASCII. This makes foreign-language text documents in UTF-8 about twice the size of English-language text documents, at least for foreign languages that don’t use the Latin character set.

ISO solves this problem by creating specific encodings for each language. Like Unicode, it has the same encodings that ASCII does, but uses the padding 0 bit at the beginning of every character to allow it to create 128 special characters for all languages that require them. This works best for European languages that also rely heavily on the Latin alphabet (which remain in positions 0–127 in the encoding), but require additional special characters. This allows ISO-8859-1 (designed for the Latin alphabet) to have symbols such as fractions (e.g., ½) or the copyright sign (©).

Other ISO character sets, such as ISO-8859-9 (Turkish), ISO-8859-2 (German, among other languages), and ISO-8859-15 (French, among other languages) can also be found on the internet with some regularity.

Although the popularity of ISO-encoded documents has been declining in recent years, about 9% of websites on the internet are still encoded with some flavor of ISO,2 making it essential to know about and check for encodings before scraping a site.

Encodings in action

In the previous section, you used the default settings for urlopen to read text documents you might encounter on the internet. This works great for most English text. However, the second you encounter Russian, Arabic, or even a word like “résumé,” you might run into problems.

Take the following code, for example:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopentextPage=urlopen('http://www.pythonscraping.com/'\'pages/warandpeace/chapter1-ru.txt')(textPage.read())

This reads in the first chapter of the original War and Peace (written in Russian and French) and prints it to the screen. This screen text reads, in part:

b"\xd0\xa7\xd0\x90\xd0\xa1\xd0\xa2\xd0\xac \xd0\x9f\xd0\x95\xd0\xa0\xd0\x92\xd0\ x90\xd0\xaf\n\nI\n\n\xe2\x80\x94 Eh bien, mon prince.

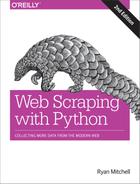

In addition, visiting this page in most browsers results in gibberish (see Figure 7-1).

Figure 7-1. French and Cyrillic text encoded in ISO-8859-1, the default text document encoding in many browsers

Even for native Russian speakers, that might be a bit difficult to make sense of. The problem is that Python is attempting to read the document as an ASCII document, whereas the browser is attempting to read it as an ISO-8859-1 encoded document. Neither one, of course, realizes it’s a UTF-8 document.

You can explicitly define the string to be UTF-8, which correctly formats the output into Cyrillic characters:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopentextPage=urlopen('http://www.pythonscraping.com/'\'pages/warandpeace/chapter1-ru.txt')(str(textPage.read(),'utf-8'))

Using this concept in BeautifulSoup and Python 3.x looks like this:

html=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Python_(programming_language)')bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')content=bs.find('div',{'id':'mw-content-text'}).get_text()content=bytes(content,'UTF-8')content=content.decode('UTF-8')

Python 3.x encodes all characters into UTF-8 by default. You might be tempted to leave this alone and use UTF-8 encoding for every web scraper you write. After all, UTF-8 will also handle ASCII characters as well as foreign languages smoothly. However, it’s important to remember the 9% of websites out there that use some version of ISO encoding as well, so you can never avoid this problem entirely.

Unfortunately, in the case of text documents, it’s impossible to concretely determine what encoding a document has. Some libraries can examine the document and make a best guess (using a little logic to realize that “раÑÑказє is probably not a word), but many times it’s wrong.

Fortunately, in the case of HTML pages, the encoding is usually contained in a tag found in the <head> section of the site. Most sites, particularly English-language sites, have this tag:

<metacharset="utf-8"/>

Whereas the ECMA International’s website has this tag:3

<METAHTTP-EQUIV="Content-Type"CONTENT="text/html; charset=iso-8859-1">

If you plan on doing a lot of web scraping, particularly of international sites, it might be wise to look for this meta tag and use the encoding it recommends when reading the contents of the page.

CSV

When web scraping, you are likely to encounter either a CSV file or a coworker who likes data formatted in this way. Fortunately, Python has a fantastic library for both reading and writing CSV files. Although this library is capable of handling many variations of CSV, this section focuses primarily on the standard format. If you have a special case you need to handle, consult the documentation!

Reading CSV Files

Python’s csv library is geared primarily toward working with local files, on the assumption that the CSV data you need is stored on your machine. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case, especially when you’re web scraping. There are several ways to work around this:

- Download the file locally by hand and point Python at the local file location.

- Write a Python script to download the file, read it, and (optionally) delete it after retrieval.

- Retrieve the file as a string from the web, and wrap the string in a

StringIOobject so that it behaves like a file.

Although the first two options are workable, taking up hard drive space with files when you could easily keep them in memory is bad practice. It’s much better to read the file in as a string and wrap it in an object that allows Python to treat it as a file, without ever saving the file. The following script retrieves a CSV file from the internet (in this case, a list of Monty Python albums at http://pythonscraping.com/files/MontyPythonAlbums.csv) and prints it, row by row, to the terminal:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfromioimportStringIOimportcsvdata=urlopen('http://pythonscraping.com/files/MontyPythonAlbums.csv').read().decode('ascii','ignore')dataFile=StringIO(data)csvReader=csv.reader(dataFile)forrowincsvReader:(row)

The output looks like this:

['Name', 'Year'] ["Monty Python's Flying Circus", '1970'] ['Another Monty Python Record', '1971'] ["Monty Python's Previous Record", '1972'] ...

As you can see from the code sample, the reader object returned by csv.reader is iterable and composed of Python list objects. Because of this, each row in the csvReader object is accessible in the following way:

forrowincsvReader:('The album "'+row[0]+'" was released in '+str(row[1]))

Here is the output:

The album "Name" was released in Year The album "Monty Python's Flying Circus" was released in 1970 The album "Another Monty Python Record" was released in 1971 The album "Monty Python's Previous Record" was released in 1972 ...

Notice the first line: The album "Name" was released in Year. Although this might be an easy-to-ignore result when writing example code, you don’t want this getting into your data in the real world. A lesser programmer might simply skip the first row in the csvReader object, or write in a special case to handle it. Fortunately, an alternative to the csv.reader function takes care of all of this for you automatically. Enter DictReader:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfromioimportStringIOimportcsvdata=urlopen('http://pythonscraping.com/files/MontyPythonAlbums.csv').read().decode('ascii','ignore')dataFile=StringIO(data)dictReader=csv.DictReader(dataFile)(dictReader.fieldnames)forrowindictReader:(row)

csv.DictReader returns the values of each row in the CSV file as dictionary objects rather than list objects, with field names stored in the variable dictReader.fieldnames and as keys in each dictionary object:

['Name', 'Year']

{'Name': 'Monty Python's Flying Circus', 'Year': '1970'}

{'Name': 'Another Monty Python Record', 'Year': '1971'}

{'Name': 'Monty Python's Previous Record', 'Year': '1972'}

The downside, of course, is that it takes slightly longer to create, process, and print these DictReader objects as opposed to csvReader, but the convenience and usability is often worth the additional overhead. Also keep in mind that, when it comes to web scraping, the overhead required for requesting and retrieving website data from an external server will almost always be the unavoidable limiting factor in any program you write, so worrying about which technique might shave microseconds off your total runtime is often a moot point!

As a Linux user, I know the pain of being sent a .docx file that my non-Microsoft software mangles and struggling trying to find the codecs to interpret some new Apple media format. In some ways, Adobe was revolutionary in creating its Portable Document Format in 1993. PDFs allowed users on different platforms to view image and text documents in exactly the same way, regardless of the platform they were viewing it on.

Although storing PDFs on the web is somewhat passé (why store content in a static, slow-loading format when you could write it up as HTML?), PDFs remain ubiquitous, particularly when dealing with official forms and filings.

In 2009, a Briton named Nick Innes made the news when he requested public student test result information from the Buckinghamshire City Council, which was available under the United Kingdom’s version of the Freedom of Information Act. After some repeated requests and denials, he finally received the information he was looking for—in the form of 184 PDF documents.

Although Innes persisted and eventually received a more properly formatted database, had he been an expert web scraper, he likely could have saved himself a lot of time in the courts and used the PDF documents directly, with one of Python’s many PDF-parsing modules.

Unfortunately, many of the PDF-parsing libraries built for Python 2.x were not upgraded with the launch of Python 3.x. However, because the PDF is a relatively simple and open source document format, many decent Python libraries, even in Python 3.x, can read them.

PDFMiner3K is one such relatively easy-to-use library. It is flexible, allowing for command-line usage or integration into existing code. It can also handle a variety of language encodings—again, something that often comes in handy on the web.

You can install as usual using pip, or download this Python module and install it by unzipping the folder and running the following:

$ python setup.py install

The documentation is located at /pdfminer3k-1.3.0/docs/index.html within the extracted folder, although the current documentation tends to be geared more toward the command-line interface than integration with Python code.

Here is a basic implementation that allows you to read arbitrary PDFs to a string, given a local file object:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrompdfminer.pdfinterpimportPDFResourceManager,process_pdffrompdfminer.converterimportTextConverterfrompdfminer.layoutimportLAParamsfromioimportStringIOfromioimportopendefreadPDF(pdfFile):rsrcmgr=PDFResourceManager()retstr=StringIO()laparams=LAParams()device=TextConverter(rsrcmgr,retstr,laparams=laparams)process_pdf(rsrcmgr,device,pdfFile)device.close()content=retstr.getvalue()retstr.close()returncontentpdfFile=urlopen('http://pythonscraping.com/''pages/warandpeace/chapter1.pdf')outputString=readPDF(pdfFile)(outputString)pdfFile.close()

This gives the familiar plain-text output:

CHAPTER I "Well, Prince, so Genoa and Lucca are now just family estates of the Buonapartes. But I warn you, if you don't tell me that this means war, if you still try to defend the infamies and horrors perpetrated by that Antichrist- I really believe he is Antichrist- I will

The nice thing about this PDF reader is that if you’re working with files locally, you can substitute a regular Python file object for the one returned by urlopen and use this line:

pdfFile=open('../pages/warandpeace/chapter1.pdf','rb')

The output might not be perfect, especially for PDFs with images, oddly formatted text, or text arranged in tables or charts. However, for most text-only PDFs, the output should be no different than if the PDF were a text file.

Microsoft Word and .docx

At the risk of offending my friends at Microsoft: I do not like Microsoft Word. Not because it’s necessarily a bad piece of software, but because of the way its users misuse it. It has a particular talent for turning what should be simple text documents or PDFs into large, slow, difficult-to-open beasts that often lose all formatting from machine to machine, and are, for whatever reason, editable when the content is often meant to be static.

Word files are designed for content creation, not content sharing. Nevertheless, they are ubiquitous on certain sites, containing important documents, information, and even charts and multimedia; in short, everything that can and should be created with HTML.

Before about 2008, Microsoft Office products used the proprietary .doc file format. This binary-file format was difficult to read and poorly supported by other word processors. In an effort to get with the times and adopt a standard that was used by many other pieces of software, Microsoft decided to use the Open Office XML-based standard, which made the files compatible with open source and other software.

Unfortunately, Python’s support for this file format, used by Google Docs, Open Office, and Microsoft Office, still isn’t great. There is the python-docx library, but this only gives users the ability to create documents and read only basic file data such as the size and title of the file, not the actual contents. To read the contents of a Microsoft Office file, you’ll need to roll your own solution.

The first step is to read the XML from the file:

fromzipfileimportZipFilefromurllib.requestimporturlopenfromioimportBytesIOwordFile=urlopen('http://pythonscraping.com/pages/AWordDocument.docx').read()wordFile=BytesIO(wordFile)document=ZipFile(wordFile)xml_content=document.read('word/document.xml')(xml_content.decode('utf-8'))

This reads a remote Word document as a binary file object (BytesIO is analogous to StringIO, used earlier in this chapter), unzips it using Python’s core zipfile library (all .docx files are zipped to save space), and then reads the unzipped file, which is XML.

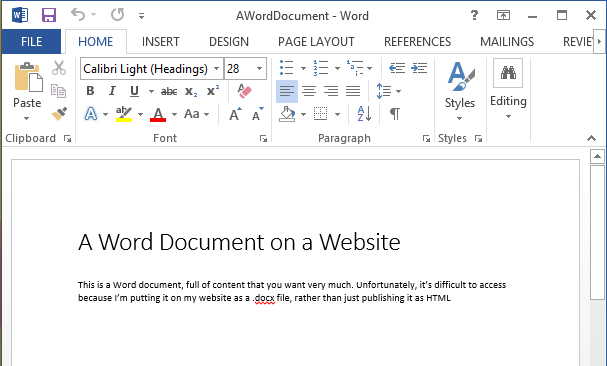

The Word document at http://pythonscraping.com/pages/AWordDocument.docx is shown in Figure 7-2.

Figure 7-2. This is a Word document that’s full of content you might want very much, but it’s difficult to access because I’m putting it on my website as a .docx file instead of publishing it as HTML

The output of the Python script reading my simple Word document is the following:

<!--?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?--><w:documentmc:ignorable="w14 w15 wp14"xmlns:m="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/math"xmlns:mc="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/markup-compatibility/2006"xmlns:o="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office"xmlns:r="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships"xmlns:v="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:vml"xmlns:w="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/wordprocessingml/2006/main"xmlns:w10="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:word"xmlns:w14="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2010/wordml"xmlns:w15="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2012/wordml"xmlns:wne="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2006/wordml"xmlns:wp="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/drawingml/2006/wordprocessingDrawing"xmlns:wp14="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2010/wordprocessingDrawing"xmlns:wpc="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2010/wordprocessingCanvas"xmlns:wpg="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2010/wordprocessingGroup"xmlns:wpi="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2010/wordprocessingInk"xmlns:wps="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2010/wordprocessingShape"><w:body><w:pw:rsidp="00764658"w:rsidr="00764658"w:rsidrdefault="00764658"><w:ppr><w:pstylew:val="Title"></w:pstyle></w:ppr><w:r><w:t>A Word Document on a Website</w:t></w:r><w:bookmarkstartw:id="0"w:name="_GoBack"></w:bookmarkstart><w:bookmarkendw:id="0"></w:bookmarkend></w:p><w:pw:rsidp="00764658"w:rsidr="00764658"w:rsidrdefault="00764658"></w:p><w:pw:rsidp="00764658"w:rsidr="00764658"w:rsidrdefault="00764658"w:rsidrpr="00764658"><w:r><w:t>This is a Word document, full of content that you want ve ry much. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to access because I’m putting it on my website as a .</w:t></w:r><w:prooferrw:type="spellStart"></w:prooferr><w:r><w:t>docx</w:t></w:r><w:prooferrw:type="spellEnd"></w:prooferr><w:r><w:txml:space="preserve">file, rather than just p ublishing it as HTML</w:t></w:r></w:p><w:sectprw:rsidr="00764658"w:rsidrpr="00764658"><w:pgszw:h="15840"w:w="12240"></w:pgsz><w:pgmarw:bottom="1440"w:footer="720"w:gutter="0"w:header="720"w:left="1440"w:right="1440"w:top="1440"></w:pgmar><w:colsw:space="720"></w:cols&g;<w:docgridw:linepitch="360"></w:docgrid></w:sectpr></w: body></w:document>

There’s clearly a lot of metadata here, but the actual text content you want is buried. Fortunately, all of the text in the document, including the title at the top, is contained in w:t tags, which makes it easy to grab:

fromzipfileimportZipFilefromurllib.requestimporturlopenfromioimportBytesIOfrombs4importBeautifulSoupwordFile=urlopen('http://pythonscraping.com/pages/AWordDocument.docx').read()wordFile=BytesIO(wordFile)document=ZipFile(wordFile)xml_content=document.read('word/document.xml')wordObj=BeautifulSoup(xml_content.decode('utf-8'),'xml')textStrings=wordObj.find_all('w:t')fortextElemintextStrings:(textElem.text)

Note that instead of the html.parser parser that you normally use with BeautifulSoup, you’re passing it the xml parser. This is because colons are nonstandard in HTML tag names like w:t and html.parser does not recognize them.

The output isn’t perfect but it’s getting there, and printing each w:t tag on a new line makes it easy to see how Word is splitting up the text:

A Word Document on a Website This is a Word document, full of content that you want very much. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to access because I’m putting it on my website as a . docx file, rather than just publishing it as HTML

Notice that the word “docx” is on its own line. In the original XML, it is surrounded with the tag <w:proofErr w:type="spellStart"/>. This is Word’s way of highlighting “docx” with the red squiggly underline, indicating that it believes there’s a spelling error in the name of its own file format.

The title of the document is preceded by the style descriptor tag <w:pstyle w:val="Title">. Although this doesn’t make it extremely easy for us to identify titles (or other styled text) as such, using BeautifulSoup’s navigation features can be useful:

textStrings=wordObj.find_all('w:t')fortextElemintextStrings:style=textElem.parent.parent.find('w:pStyle')ifstyleisnotNoneandstyle['w:val']=='Title':('Title is: {}'.format(textElem.text))else:(textElem.text)

This function can be easily expanded to print tags around a variety of text styles or label them in some other way.