Chapter 3. Writing Web Crawlers

So far, you’ve seen single static pages with somewhat artificial canned examples. In this chapter, you’ll start looking at real-world problems, with scrapers traversing multiple pages and even multiple sites.

Web crawlers are called such because they crawl across the web. At their core is an element of recursion. They must retrieve page contents for a URL, examine that page for another URL, and retrieve that page, ad infinitum.

Beware, however: just because you can crawl the web doesn’t mean that you always should. The scrapers used in previous examples work great in situations where all the data you need is on a single page. With web crawlers, you must be extremely conscientious of how much bandwidth you are using and make every effort to determine whether there’s a way to make the target server’s load easier.

Traversing a Single Domain

Even if you haven’t heard of Six Degrees of Wikipedia, you’ve almost certainly heard of its namesake, Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon. In both games, the goal is to link two unlikely subjects (in the first case, Wikipedia articles that link to each other, and in the second case, actors appearing in the same film) by a chain containing no more than six total (including the two original subjects).

For example, Eric Idle appeared in Dudley Do-Right with Brendan Fraser, who appeared in The Air I Breathe with Kevin Bacon.1 In this case, the chain from Eric Idle to Kevin Bacon is only three subjects long.

In this section, you’ll begin a project that will become a Six Degrees of Wikipedia solution finder: You’ll be able to take the Eric Idle page and find the fewest number of link clicks that will take you to the Kevin Bacon page.

You should already know how to write a Python script that retrieves an arbitrary Wikipedia page and produces a list of links on that page:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSouphtml=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_Bacon')bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')forlinkinbs.find_all('a'):if'href'inlink.attrs:(link.attrs['href'])

If you look at the list of links produced, you’ll notice that all the articles you’d expect are there: “Apollo 13,” “Philadelphia,” “Primetime Emmy Award,” and so on. However, there are some things that you don’t want as well:

//wikimediafoundation.org/wiki/Privacy_policy //en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Contact_us

In fact, Wikipedia is full of sidebar, footer, and header links that appear on every page, along with links to the category pages, talk pages, and other pages that do not contain different articles:

/wiki/Category:Articles_with_unsourced_statements_from_April_2014 /wiki/Talk:Kevin_Bacon

Recently a friend of mine, while working on a similar Wikipedia-scraping project, mentioned he had written a large filtering function, with more than 100 lines of code, in order to determine whether an internal Wikipedia link was an article page. Unfortunately, he had not spent much time upfront trying to find patterns between “article links” and “other links,” or he might have discovered the trick. If you examine the links that point to article pages (as opposed to other internal pages), you’ll see that they all have three things in common:

-

They reside within the

divwith theidset tobodyContent. -

The URLs do not contain colons.

-

The URLs begin with /wiki/.

You can use these rules to revise the code slightly to retrieve only the desired article links by using the regular expression ^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$"):

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportrehtml=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_Bacon')bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')forlinkinbs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$')):if'href'inlink.attrs:(link.attrs['href'])

If you run this, you should see a list of all article URLs that the Wikipedia article on Kevin Bacon links to.

Of course, having a script that finds all article links in one, hardcoded Wikipedia article, while interesting, is fairly useless in practice. You need to be able to take this code and transform it into something more like the following:

-

A single function,

getLinks, that takes in a Wikipedia article URL of the form/wiki/<Article_Name>and returns a list of all linked article URLs in the same form. -

A main function that calls

getLinkswith a starting article, chooses a random article link from the returned list, and callsgetLinksagain, until you stop the program or until no article links are found on the new page.

Here is the complete code that accomplishes this:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportdatetimeimportrandomimportrerandom.seed(datetime.datetime.now())defgetLinks(articleUrl):html=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(articleUrl))bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')returnbs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$'))links=getLinks('/wiki/Kevin_Bacon')whilelen(links)>0:newArticle=links[random.randint(0,len(links)-1)].attrs['href'](newArticle)links=getLinks(newArticle)

The first thing the program does, after importing the needed libraries, is set the random-number generator seed with the current system time. This practically ensures a new and interesting random path through Wikipedia articles every time the program is run.

Next, the program defines the getLinks function, which takes in an article URL of the form /wiki/..., prepends the Wikipedia domain name, http://en.wikipedia.org, and retrieves the BeautifulSoup object for the HTML at that domain. It then extracts a list of article link tags, based on the parameters discussed previously, and returns them.

The main body of the program begins with setting a list of article link tags (the links variable) to the list of links in the initial page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_Bacon. It then goes into a loop, finding a random article link tag in the page, extracting the href attribute from it, printing the page, and getting a new list of links from the extracted URL.

Of course, there’s a bit more to solving a Six Degrees of Wikipedia problem than building a scraper that goes from page to page. You must also be able to store and analyze the resulting data. For a continuation of the solution to this problem, see Chapter 6.

Handle Your Exceptions!

Although these code examples omit most exception handling for the sake of brevity, be aware that many potential pitfalls could arise. What if Wikipedia changes the name of the bodyContent tag, for example? When the program attempts to extract the text from the tag, it throws an AttributeError.

So although these scripts might be fine to run as closely watched examples, autonomous production code requires far more exception handling than can fit into this book. Look back to Chapter 1 for more information about this.

Crawling an Entire Site

In the previous section, you took a random walk through a website, going from link to link. But what if you need to systematically catalog or search every page on a site? Crawling an entire site, especially a large one, is a memory-intensive process that is best suited to applications for which a database to store crawling results is readily available. However, you can explore the behavior of these types of applications without running them full-scale. To learn more about running these applications by using a database, see Chapter 6.

When might crawling an entire website be useful, and when might it be harmful? Web scrapers that traverse an entire site are good for many things, including the following:

- Generating a site map

- A few years ago, I was faced with a problem: an important client wanted an estimate for a website redesign, but did not want to provide my company with access to the internals of their current content management system, and did not have a publicly available site map. I was able to use a crawler to cover the entire site, gather all internal links, and organize the pages into the actual folder structure used on the site. This allowed me to quickly find sections of the site I wasn’t even aware existed, and accurately count how many page designs would be required and how much content would need to be migrated.

- Gathering data

- Another client of mine wanted to gather articles (stories, blog posts, news articles, etc.) in order to create a working prototype of a specialized search platform. Although these website crawls didn’t need to be exhaustive, they did need to be fairly expansive (we were interested in getting data from only a few sites). I was able to create crawlers that recursively traversed each site and collected only data found on article pages.

The general approach to an exhaustive site crawl is to start with a top-level page (such as the home page), and search for a list of all internal links on that page. Every one of those links is then crawled, and additional lists of links are found on each one of them, triggering another round of crawling.

Clearly, this is a situation that can blow up quickly. If every page has 10 internal links, and a website is 5 pages deep (a fairly typical depth for a medium-size website), then the number of pages you need to crawl is 105, or 100,000 pages, before you can be sure that you’ve exhaustively covered the website. Strangely enough, although “5 pages deep and 10 internal links per page” are fairly typical dimensions for a website, very few websites have 100,000 or more pages. The reason, of course, is that the vast majority of internal links are duplicates.

To avoid crawling the same page twice, it is extremely important that all internal links discovered are formatted consistently, and kept in a running set for easy lookups, while the program is running. A set is similar to a list, but elements do not have a specific order, and only unique elements will be stored, which is ideal for our needs. Only links that are “new” should be crawled and searched for additional links:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportrepages=set()defgetLinks(pageUrl):globalpageshtml=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(pageUrl))bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')forlinkinbs.find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)')):if'href'inlink.attrs:iflink.attrs['href']notinpages:#We have encountered a new pagenewPage=link.attrs['href'](newPage)pages.add(newPage)getLinks(newPage)getLinks('')

To show you the full effect of how this web crawling business works, I’ve relaxed the standards of what constitutes an internal link (from previous examples). Rather than limit the scraper to article pages, it looks for all links that begin with /wiki/, regardless of where they are on the page, and regardless of whether they contain colons. Remember: article pages do not contain colons, but file-upload pages, talk pages, and the like do contain colons in the URL.

Initially, getLinks is called with an empty URL. This is translated as “the front page of Wikipedia” as soon as the empty URL is prepended with http://en.wikipedia.org inside the function. Then, each link on the first page is iterated through and a check is made to see whether it is in the global set of pages (a set of pages that the script has encountered already). If not, it is added to the list, printed to the screen, and the getLinks function is called recursively on it.

A Warning Regarding Recursion

This is a warning rarely seen in software books, but I thought you should be aware: if left running long enough, the preceding program will almost certainly crash.

Python has a default recursion limit (the number of times a program can recursively call itself) of 1,000. Because Wikipedia’s network of links is extremely large, this program will eventually hit that recursion limit and stop, unless you put in a recursion counter or something to prevent that from happening.

For “flat” sites that are fewer than 1,000 links deep, this method usually works well, with a few unusual exceptions. For instance, I once encountered a bug in a dynamically generated URL that depended on the address of the current page to write the link on that page. This resulted in infinitely repeating paths like /blogs/blogs.../blogs/blog-post.php.

For the most part, however, this recursive technique should be fine for any typical website you’re likely to encounter.

Collecting Data Across an Entire Site

Web crawlers would be fairly boring if all they did was hop from one page to the other. To make them useful, you need to be able to do something on the page while you’re there. Let’s look at how to build a scraper that collects the title, the first paragraph of content, and the link to edit the page (if available).

As always, the first step to determine how best to do this is to look at a few pages from the site and determine a pattern. By looking at a handful of Wikipedia pages (both articles and nonarticle pages such as the privacy policy page), the following things should be clear:

-

All titles (on all pages, regardless of their status as an article page, an edit history page, or any other page) have titles under

h1→spantags, and these are the onlyh1tags on the page. -

As mentioned before, all body text lives under the

div#bodyContenttag. However, if you want to get more specific and access just the first paragraph of text, you might be better off usingdiv#mw-content-text→p(selecting the first paragraph tag only). This is true for all content pages except file pages (for example, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Orbit_of_274301_Wikipedia.svg), which do not have sections of content text. -

Edit links occur only on article pages. If they occur, they will be found in the

li#ca-edittag, underli#ca-edit→span→a.

By modifying our basic crawling code, you can create a combination crawler/data-gathering (or, at least, data-printing) program:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportrepages=set()defgetLinks(pageUrl):globalpageshtml=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(pageUrl))bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')try:(bs.h1.get_text())(bs.find(id='mw-content-text').find_all('p')[0])(bs.find(id='ca-edit').find('span').find('a').attrs['href'])exceptAttributeError:('This page is missing something! Continuing.')forlinkinbs.find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)')):if'href'inlink.attrs:iflink.attrs['href']notinpages:#We have encountered a new pagenewPage=link.attrs['href']('-'*20)(newPage)pages.add(newPage)getLinks(newPage)getLinks('')

The for loop in this program is essentially the same as it was in the original crawling program (with the addition of printed dashes for clarity, separating the printed content).

Because you can never be entirely sure that all the data is on each page, each print statement is arranged in the order that it is likeliest to appear on the site. That is, the h1 title tag appears on every page (as far as I can tell, at any rate) so you attempt to get that data first. The text content appears on most pages (except for file pages), so that is the second piece of data retrieved. The Edit button appears only on pages in which both titles and text content already exist, but it does not appear on all of those pages.

Different Patterns for Different Needs

Obviously, some dangers are involved with wrapping multiple lines in an exception handler. You cannot tell which line threw the exception, for one thing. Also, if for some reason a page contains an Edit button but no title, the Edit button would never be logged. However, it suffices for many instances in which there is an order of likeliness of items appearing on the site, and inadvertently missing a few data points or keeping detailed logs is not a problem.

You might notice that in this and all the previous examples, you haven’t been “collecting” data so much as “printing” it. Obviously, data in your terminal is hard to manipulate. You’ll look more at storing information and creating databases in Chapter 5.

Crawling Across the Internet

Whenever I give a talk on web scraping, someone inevitably asks, “How do you build Google?” My answer is always twofold: “First, you get many billions of dollars so that you can buy the world’s largest data warehouses and place them in hidden locations all around the world. Second, you build a web crawler.”

When Google started in 1996, it was just two Stanford graduate students with an old server and a Python web crawler. Now that you know how to scrape the web, you officially have the tools you need to become the next tech multibillionaire!

In all seriousness, web crawlers are at the heart of what drives many modern web technologies, and you don’t necessarily need a large data warehouse to use them. To do any cross-domain data analysis, you do need to build crawlers that can interpret and store data across the myriad of pages on the internet.

Just as in the previous example, the web crawlers you are going to build will follow links from page to page, building out a map of the web. But this time, they will not ignore external links; they will follow them.

Unknown Waters Ahead

Keep in mind that the code from the next section can go anywhere on the internet. If we’ve learned anything from Six Degrees of Wikipedia, it’s that it’s entirely possible to go from a site such as http://www.sesamestreet.org/ to something less savory in just a few hops.

Kids, ask your parents before running this code. For those with sensitive constitutions or with religious restrictions that might prohibit seeing text from a prurient site, follow along by reading the code examples but be careful when running them.

Before you start writing a crawler that follows all outbound links willy-nilly, you should ask yourself a few questions:

-

What data am I trying to gather? Can this be accomplished by scraping just a few predefined websites (almost always the easier option), or does my crawler need to be able to discover new websites I might not know about?

-

When my crawler reaches a particular website, will it immediately follow the next outbound link to a new website, or will it stick around for a while and drill down into the current website?

-

Are there any conditions under which I would not want to scrape a particular site? Am I interested in non-English content?

-

How am I protecting myself against legal action if my web crawler catches the attention of a webmaster on one of the sites it runs across? (Check out Chapter 18 for more information on this subject.)

A flexible set of Python functions that can be combined to perform a variety of types of web scraping can be easily written in fewer than 60 lines of code:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfromurllib.parseimporturlparsefrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportreimportdatetimeimportrandompages=set()random.seed(datetime.datetime.now())#Retrieves a list of all Internal links found on a pagedefgetInternalLinks(bs,includeUrl):includeUrl='{}://{}'.format(urlparse(includeUrl).scheme,urlparse(includeUrl).netloc)internalLinks=[]#Finds all links that begin with a "/"forlinkinbs.find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/|.*'+includeUrl+')')):iflink.attrs['href']isnotNone:iflink.attrs['href']notininternalLinks:if(link.attrs['href'].startswith('/')):internalLinks.append( includeUrl+link.attrs['href'])else:internalLinks.append(link.attrs['href'])returninternalLinks#Retrieves a list of all external links found on a pagedefgetExternalLinks(bs,excludeUrl):externalLinks=[]#Finds all links that start with "http" or "www" that do#not contain the current URLforlinkinbs.find_all('a', href=re.compile('^(http|www)((?!'+excludeUrl+').)*$')):iflink.attrs['href']isnotNone:iflink.attrs['href']notinexternalLinks:externalLinks.append(link.attrs['href'])returnexternalLinksdefgetRandomExternalLink(startingPage):html=urlopen(startingPage)bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')externalLinks=getExternalLinks(bs, urlparse(startingPage).netloc)iflen(externalLinks)==0:('No external links, looking around the site for one')domain='{}://{}'.format(urlparse(startingPage).scheme, urlparse(startingPage).netloc)internalLinks=getInternalLinks(bs,domain)returngetRandomExternalLink(internalLinks[random.randint(0,len(internalLinks)-1)])else:returnexternalLinks[random.randint(0,len(externalLinks)-1)]deffollowExternalOnly(startingSite):externalLink=getRandomExternalLink(startingSite)('Random external link is: {}'.format(externalLink))followExternalOnly(externalLink)followExternalOnly('http://oreilly.com')

The preceding program starts at http://oreilly.com and randomly hops from external link to external link. Here’s an example of the output it produces:

http://igniteshow.com/ http://feeds.feedburner.com/oreilly/news http://hire.jobvite.com/CompanyJobs/Careers.aspx?c=q319 http://makerfaire.com/

External links are not always guaranteed to be found on the first page of a website. To find external links in this case, a method similar to the one used in the previous crawling example is employed to recursively drill down into a website until it finds an external link.

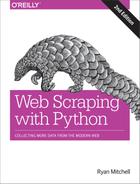

Figure 3-1 illustrates the operation as a flowchart.

Figure 3-1. Flowchart for our script that crawls through sites on the internet

Don’t Put Example Programs into Production

I keep bringing this up, but for the sake of space and readability, the example programs in this book do not always contain the necessary checks and exception handling required for production-ready code. For example, if an external link is not found anywhere on a site that this crawler encounters (unlikely, but it’s bound to happen at some point if you run it for long enough), this program will keep running until it hits Python’s recursion limit.

One easy way to increase the robustness of this crawler would be to combine it with the connection exception-handling code in Chapter 1. This would allow the code to choose a different URL to go to if an HTTP error or server exception was encountered when retrieving the page.

Before running this code for any serious purpose, make sure that you are putting checks in place to handle potential pitfalls.

The nice thing about breaking up tasks into simple functions such as “find all external links on this page” is that the code can later be easily refactored to perform a different crawling task. For example, if your goal is to crawl an entire site for external links, and make a note of each one, you can add the following function:

# Collects a list of all external URLs found on the siteallExtLinks=set()allIntLinks=set()defgetAllExternalLinks(siteUrl):html=urlopen(siteUrl)domain='{}://{}'.format(urlparse(siteUrl).scheme, urlparse(siteUrl).netloc)bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')internalLinks=getInternalLinks(bs,domain)externalLinks=getExternalLinks(bs,domain)forlinkinexternalLinks:iflinknotinallExtLinks:allExtLinks.add(link)(link)forlinkininternalLinks:iflinknotinallIntLinks:allIntLinks.add(link)getAllExternalLinks(link)allIntLinks.add('http://oreilly.com')getAllExternalLinks('http://oreilly.com')

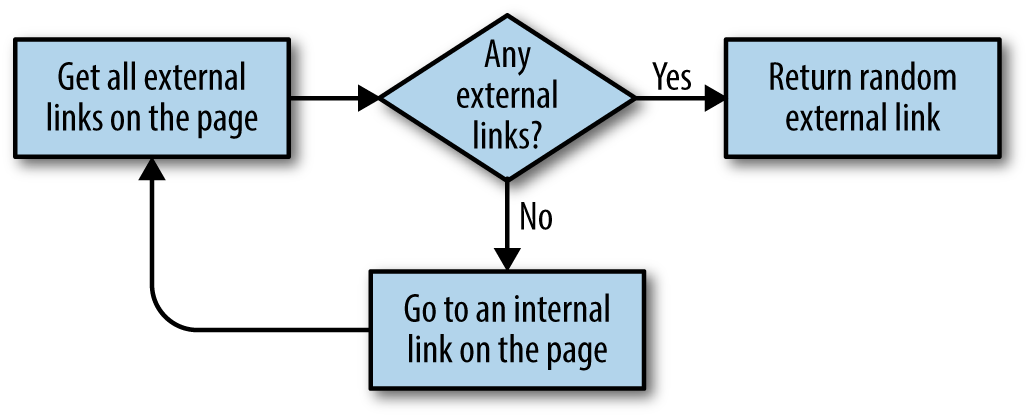

This code can be thought of as two loops—one gathering internal links, one gathering external links—working in conjunction with each other. The flowchart looks something like Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2. Flow diagram for the website crawler that collects all external links

Jotting down or making diagrams of what the code should do before you write the code itself is a fantastic habit to get into, and one that can save you a lot of time and frustration as your crawlers get more complicated.

1 Thanks to The Oracle of Bacon for satisfying my curiosity about this particular chain.

2 See “Exploring a ‘Deep Web’ that Google Can’t Grasp” by Alex Wright.

3 See “Hacker Lexicon: What is the Dark Web?” by Andy Greenberg.