Chapter 12. Crawling Through APIs

JavaScript has traditionally been the bane of web crawlers everywhere. At one point in the ancient history of the internet, you could be guaranteed that the request you made to the web server would fetch the same data that the user saw in their web browser when they made that same request.

As JavaScript and Ajax content generation and loading become more ubiquitous, this situation is becoming less common. In Chapter 11, you looked at one way of solving this: using Selenium to automate a browser and fetch the data. This is an easy thing to do. It works almost all of the time.

The problem is that, when you have a “hammer” as powerful and effective as Selenium, every web scraping problem starts to look a lot like a nail.

In this chapter, you’ll look at cutting through the JavaScript entirely (no need to execute it or even load it!) and getting straight to the source of the data: the APIs that generate it.

A Brief Introduction to APIs

Although countless books, talks, and guides have been written about the intricacies of REST, GraphQL, JSON, and XML APIs, at their core they are based on a simple concept. An API defines a standardized syntax that allows one piece of software to communicate with another piece of software, even though they might be written in different languages or otherwise structured differently.

This section focuses on web APIs (in particular, APIs that allow a web server to communicate to a browser) and uses the term API to refer specifically to that type. But you may want to keep in mind that, in other contexts, API is also a generic term that can be used to, say, allow a Java program to communicate with a Python program running on the same machine. An API does not always have to be “across the internet” and does not necessarily involve any web technologies.

Web APIs are most often used by developers who are using a well-advertised and documented public service. For example, ESPN provides APIs for athlete information, game scores, and more. Google has dozens of APIs in its Developers section for language translations, analytics, and geolocation.

The documentation for these APIs typically describes routes or endpoints, as URLs that you can request, with variable parameters, either in the path of the URL or as GET parameters.

For example, the following provides pathparam as a parameter in the route path:

http://example.com/the-api-route/pathparam

And this provides pathparam as the value for the parameter param1:

http://example.com/the-api-route?param1=pathparam

Both methods of passing variable data to the API are frequently used, although, like many topics in computer science, philosophic debate has raged on when and where variables should be passed through the path or through the parameters.

The response from the API is usually returned in a JSON or XML format. JSON is far more popular in modern times than XML, but you may still see some XML responses. Many APIs allow you to change the response type, usually with the use of another parameter to define which type of response you would like.

Here’s an example of a JSON-formatted API response:

{"user":{"id":123,"name":"Ryan Mitchell","city":"Boston"}}

Here’s an example of an XML-formatted API response:

<user><id>123</id><name>Ryan Mitchell</name><city>Boston</city></user>

ip-api.com provides an easy-to-use and simple API that translates IP addresses to actual physical addresses. You can try a simple API request by entering the following in your browser:1

http://ip-api.com/json/50.78.253.58

This should produce a response like the following:

{"ip":"50.78.253.58","country_code":"US","country_name":"United States","region_code":"MA","region_name":"Massachusetts","city":"Boston","zip_code":"02116","time_zone":"America/New_York","latitude":42.3496,"longitude":-71.0746,"metro_code":506}

Notice that the request contains the parameter json in the path. You can request an XML or CSV response by changing this parameter accordingly:

http://ip-api.com/xml/50.78.253.58 http://ip-api.com/csv/50.78.253.58

HTTP Methods and APIs

In the previous section, you looked at APIs making a GET request to the server for information. There are four main ways (or methods) to request information from a web server via HTTP:

-

GET -

POST -

PUT -

DELETE

Technically, more than these four exist (such as HEAD, OPTIONS, and CONNECT), but they are rarely used in APIs, and it is unlikely that you will ever see them. The vast majority of APIs limit themselves to these four methods, or even a subset of these four methods. It is common to see APIs that use only GET, or use only GET and POST.

GET is what you use when you visit a website through the address bar in your browser. GET is the method you are using when you make a call to http://ip-api.com/json/50.78.253.58. You can think of GET as saying, “Hey, web server, please retrieve/get me this information.”

A GET request, by definition, makes no changes to the information in the server’s database. Nothing is stored; nothing is modified. Information is only read.

POST is what you use when you fill out a form or submit information, presumably to a backend script on the server. Every time you log into a website, you are making a POST request with your username and (hopefully) encrypted password. If you are making a POST request with an API, you are saying, “Please store this information in your database.”

PUT is less commonly used when interacting with websites, but is used from time to time in APIs. A PUT request is used to update an object or information. An API might require a POST request to create a new user, for example, but it might need a PUT request if you want to update that user’s email address.2

DELETE is used, as you might imagine, to delete an object. For instance, if you send a DELETE request to http://myapi.com/user/23, it will delete the user with the ID 23. DELETE methods are not often encountered in public APIs, which are primarily created to disseminate information or allow users to create or post information, rather than allow users to remove that information from their databases.

Unlike GET requests, POST, PUT, and DELETE requests allow you to send information in the body of a request, in addition to the URL or route from which you are requesting data.

Just like the response that you receive from the web server, this data in the body is typically formatted as JSON or, less commonly, as XML, and the format of this data is defined by the syntax of the API. For example, if you are using an API that creates comments on blog posts, you might make a PUT request to

http://example.com/comments?post=123

with the following request body:

{"title":"Great post about APIs!","body":"Very informative. Really helped meout with a tricky technical challenge I was facing. Thanks for taking the timeto write such a detailed blog post about PUT requests!","author":{"name":"RyanMitchell","website":"http://pythonscraping.com","company":"O'Reilly Media"}}

Note that the ID of the blog post (123) is passed as a parameter in the URL, where the content for the new comment you are making is passed in the body of the request. Parameters and data may be passed in both the parameter and the body. Which parameters are required and where they are passed is determined, again, by the syntax of the API.

More About API Responses

As you saw in the ip-api.com example at the beginning of the chapter, an important feature of APIs is that they have well-formatted responses. The most common types of response formatting are eXtensible Markup Language (XML) and JavaScript Object Notation (JSON).

In recent years, JSON has become vastly more popular than XML for a couple of major reasons. First, JSON files are generally smaller than well-designed XML files. Compare, for example, the following XML data, which clocks in at 98 characters:

<user><firstname>Ryan</firstname><lastname>Mitchell</lastname><username>Kludgist</username></user>

And now look at the same data in JSON:

{"user":{"firstname":"Ryan","lastname":"Mitchell","username":"Kludgist"}}

This is only 73 characters, or a whopping 36% smaller than the equivalent XML.

Of course, one could argue that the XML could be formatted like this:

<userfirstname="ryan"lastname="mitchell"username="Kludgist"></user>

But this is considered bad practice because it doesn’t support deep nesting of data. Regardless, it still requires 71 characters, about the same length as the equivalent JSON.

Another reason JSON is quickly becoming more popular than XML is due to a shift in web technologies. In the past, it was more common for a server-side script such as PHP or .NET to be on the receiving end of an API. Nowadays, it is likely that a framework, such as Angular or Backbone, will be sending and receiving API calls. Server-side technologies are somewhat agnostic as to the form in which their data comes. But JavaScript libraries like Backbone find JSON easier to handle.

Although APIs are typically thought of as having either an XML response or a JSON response, anything is possible. The response type of the API is limited only by the imagination of the programmer who created it. CSV is another typical response output (as seen in the ip-api.com example). Some APIs may even be designed to generate files. A request may be made to a server to generate an image with some particular text overlaid on it, or request a particular XLSX or PDF file.

Some APIs return no response at all. For example, if you are making a request to a server to create a new blog post comment, it may return only an HTTP response code 200, meaning “I posted the comment; everything is great!” Others may return a minimal response like this:

{"success":true}

If an error occurs, you may get a response like this:

{"error":{"message":"Something super bad happened"}}

Or if the API is not particularly well configured, you may get a nonparsable stack trace or some plain English text. When making a request to an API, it’s usually wise to first check that the response you get is actually JSON (or XML, or CSV, or whatever format you’re expecting back).

Parsing JSON

In this chapter, you’ve looked at various types of APIs and how they function, and you’ve looked at sample JSON responses from these APIs. Now let’s look at how to parse and use this information.

At the beginning of the chapter you saw the example of the ip-api.com API, which resolves IP addresses to physical addresses:

http://ip-api.com/json/50.78.253.58

You can take the output of this request and use Python’s JSON-parsing functions to decode it:

importjsonfromurllib.requestimporturlopendefgetCountry(ipAddress):response=urlopen('http://ip-api.com/json/'+ipAddress).read().decode('utf-8')responseJson=json.loads(response)returnresponseJson.get('country_code')(getCountry('50.78.253.58'))

This prints the country code for the IP address 50.78.253.58.

The JSON parsing library used is part of Python’s core library. Just type in import json at the top, and you’re all set! Unlike many languages that might parse JSON into a special JSON object or JSON node, Python uses a more flexible approach and turns JSON objects into dictionaries, JSON arrays into lists, JSON strings into strings, and so forth. In this way, it is extremely easy to access and manipulate values stored in JSON.

The following gives a quick demonstration of how Python’s JSON library handles the values that might be encountered in a JSON string:

importjsonjsonString='{"arrayOfNums":[{"number":0},{"number":1},{"number":2}],"arrayOfFruits":[{"fruit":"apple"},{"fruit":"banana"},{"fruit":"pear"}]}'jsonObj=json.loads(jsonString)(jsonObj.get('arrayOfNums'))(jsonObj.get('arrayOfNums')[1])(jsonObj.get('arrayOfNums')[1].get('number')+jsonObj.get('arrayOfNums')[2].get('number'))(jsonObj.get('arrayOfFruits')[2].get('fruit'))

Here is the output:

[{'number': 0}, {'number': 1}, {'number': 2}]

{'number': 1}

3

pear

Line 1 is a list of dictionary objects, line 2 is a dictionary object, line 3 is an integer (the sum of the integers accessed in the dictionaries), and line 4 is a string.

Undocumented APIs

So far in this chapter, we’ve discussed only APIs that are documented. Their developers intend them to be used by the public, publish information about them, and assume that the APIs will be used by other developers. But the vast majority of APIs don’t have any published documentation at all.

But why would you create an API without any public documentation? As mentioned in the beginning of this chapter, it all has to do with JavaScript.

Traditionally, the web servers for dynamic websites had several tasks whenever a user requested a page:

-

Handle

GETrequests from users requesting a page of a website -

Retrieve the data from the database that appears on that page

-

Format the data into the HTML template for the page

-

Send that formatted HTML to the user

As JavaScript frameworks became more ubiquitous, many of the HTML creation tasks handled by the server moved into the browser. The server might send a hardcoded HTML template to the user’s browser, but separate Ajax requests would be made to load the content and place it in the correct slots in that HTML template. All this would happen on the browser/client side.

This was initially a problem for web scrapers. They were used to making a request for an HTML page and getting back exactly that—an HTML page with all of the content already in place. Instead, they now got an HTML template without any content.

Selenium was used to solve this problem. Now the programmer’s web scraper could become the browser, request the HTML template, execute any JavaScript, allow all the data to load in its place, and only then scrape the page for data. Because the HTML was all loaded, it was essentially reduced to a previously solved problem—the problem of parsing and formatting existing HTML.

However, because the entire content management system (that used to reside only in the web server) had essentially moved to the browser client, even the simplest websites could balloon into several megabytes of content and a dozen HTTP requests.

In addition, when Selenium is used, all of the “extras” that the user doesn’t necessarily care about are loaded. Calls to tracking programs, loading sidebar ads, calls to tracking programs for the sidebar ads. Images, CSS, third-party font data—all of it needs to be loaded. This may seem great when you’re using a browser to browse the web, but if you’re writing a web scraper that needs to move fast, collect specific data, and place as little of a load on the web server as possible, you can be loading a hundred times more data than you need.

But there’s a silver lining to all of this JavaScript, Ajax, and web modernization: because servers are no longer formatting the data into HTML, they often act as thin wrappers around the database itself. This thin wrapper simply extracts data from the database, and returns it to the page via an API.

Of course, these APIs aren’t meant to be used by anyone or anything besides the webpage itself, and so developers leave them undocumented and assume (or hope) that no one will notice them. But they do exist.

The New York Times website, for example, loads all of its search results via JSON. If you visit the link

https://query.nytimes.com/search/sitesearch/#/python

this will reveal recent news articles for the search term “python.” If you scrape this page using urllib or the Requests library, you won’t find any search results. These are loaded separately via an API call:

https://query.nytimes.com/svc/add/v1/sitesearch.json ?q=python&spotlight=true&facet=true

If you were to load this page with Selenium, you would be making about 100 requests and transferring 600–700 kB of data with each search. Using the API directly, you make only one request and transfer approximately only the 60 kb of nicely formatted data that you need.

Finding Undocumented APIs

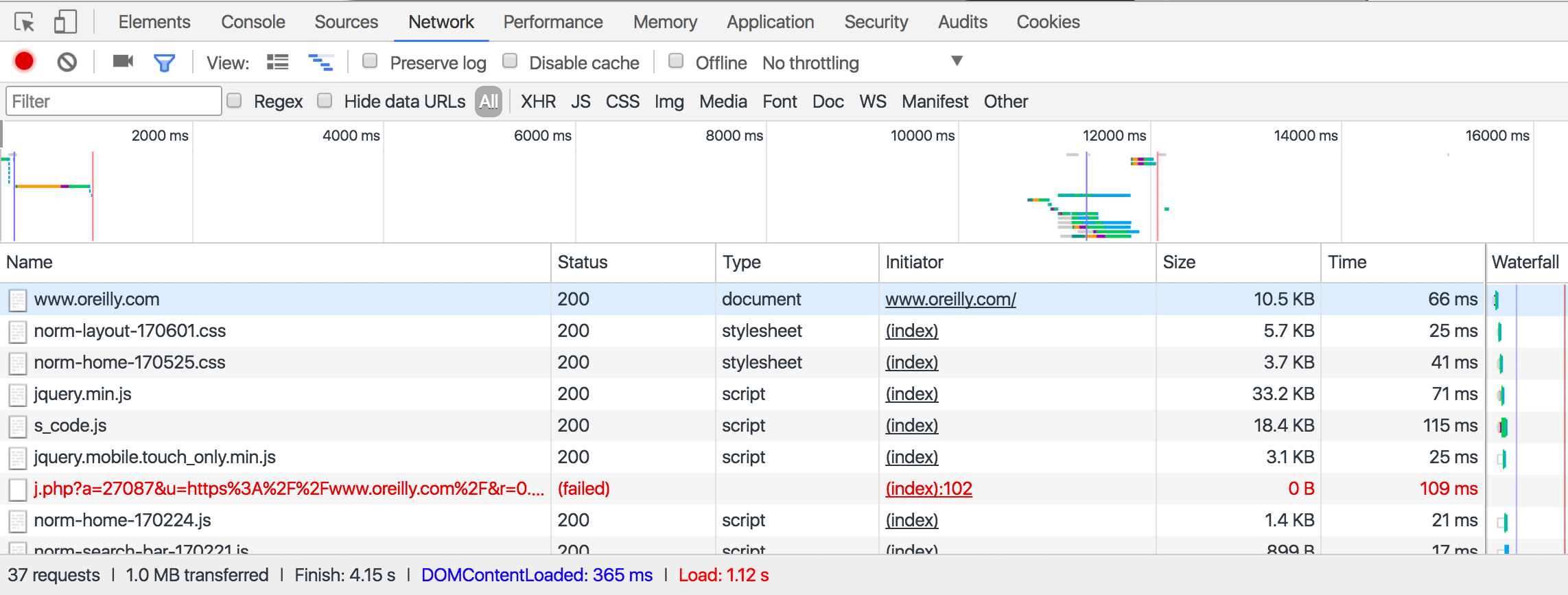

You’ve used the Chrome inspector in previous chapters to examine the contents of an HTML page, but now you’ll use it for a slightly different purpose: to examine the requests and responses of the calls that are used to construct that page.

To do this, open the Chrome inspector window and click the Network tab, shown in Figure 12-1.

Figure 12-1. The Chrome network inspector tool provides a view into all calls your browser is making and receiving

Note that you need to open this window before the page loads. It does not track network calls while it’s closed.

While the page is loading, you’ll see a line appear in real time whenever your browser makes a call back to the web server for additional information to render the page. This may include an API call.

Finding undocumented APIs can take a little detective work (to take the detective work out of this, see “Finding and Documenting APIs Automatically”), especially with larger sites with lots of network calls. Generally, though, you’ll know it when you see it.

API calls tend to have several features that are useful for locating them in the list of network calls:

-

They often have JSON or XML in them. You can filter the list of requests by using the search/filter field.

-

With

GETrequests, the URL will contain the parameter values passed to them. This will be useful if, for example, you’re looking for an API call that returns the results of a search or is loading data for a specific page. Simply filter the results with the search term you used, page ID, or other identifying information. -

They will usually be of the type XHR.

APIs may not always be obvious, especially in large sites with lots of features that may make hundreds of calls while loading a single page. However, spotting the metaphorical needle in the haystack becomes much easier with a little practice.

Documenting Undocumented APIs

After you’ve found an API call being made, it’s often useful to document it to some extent, especially if your scrapers will rely heavily on the call. You may want to load several pages on the website, filtering for the target API call in the inspector console network tab. By doing this, you can see how the call changes from page to page, and identify the fields that it accepts and returns.

Every API call can be identified and documented by paying attention to the following fields:

-

HTTP method used

-

Inputs

-

Path parameters

-

Headers (including cookies)

-

Body content (for

PUTandPOSTcalls)

-

-

Outputs

-

Response headers (including cookies set)

-

Response body type

-

Response body fields

-

Finding and Documenting APIs Automatically

The work of locating and documenting APIs can seem somewhat tedious and algorithmic. This is mostly because it is. While some websites may attempt to obfuscate how the browser is getting its data, which makes the task a little trickier, finding and documenting APIs is mostly a programmatic task.

I’ve created a GitHub repository at https://github.com/REMitchell/apiscraper that attempts to take some of the grunt work out of this task.

It uses Selenium, ChromeDriver, and a library called BrowserMob Proxy to load pages, crawl pages within a domain, analyze the network traffic that occurs during page load, and organize these requests into readable API calls.

Several moving parts are required to get this project running. The first, is the software itself.

Clone the apiscraper GitHub project. The cloned project should contain the following files:

- apicall.py

- Contains attributes that define an API call (path, parameters, etc.) as well as logic to decide whether two API calls are the same.

- apiFinder.py

- Main crawling class. Used by webservice.py and consoleservice.py to kick off the process of finding APIs.

- browser.py

- Has only three methods—

initialize,get, andclose—but encompasses relatively complicated functionality to tie together the BrowserMob Proxy server and Selenium. Scrolls through pages to ensure that the entire page is loaded, saves HTTP Archive (HAR) files to the appropriate location for processing. - consoleservice.py

- Handles commands from the console and kicks off the main

APIFinderclass. - harParser.py

- Parses HAR files and extracts API calls.

- html_template.html

- Provides a template to display API calls in the browser.

- README.md

- Git readme page.

Download the BrowserMob Proxy binary files from https://bmp.lightbody.net/ and place the extracted files in the apiscraper project directory.

As of this writing, the current version of BrowserMob Proxy is 2.1.4, so this script will assume that the binary files are at browsermob-proxy-2.1.4/bin/browsermob-proxy relative to the root project directory. If this is not the case, you can provide a different directory at runtime, or (perhaps easier) modify the code in apiFinder.py.

Download ChromeDriver and place this in the apiscraper project directory.

You’ll need to have the following Python libraries installed:

-

tldextract -

selenium -

browsermob-proxy

When this setup is done, you’re ready to start collecting API calls. Typing

$ python consoleservice.py -h

will present you with a list of options to get started:

usage: consoleservice.py [-h] [-u [U]] [-d [D]] [-s [S]] [-c [C]] [-i [I]] [--p] optional arguments: -h, --help show this help message and exit -u [U] Target URL. If not provided, target directory will be scanned for har files. -d [D] Target directory (default is "hars"). If URL is provided, directory will store har files. If URL is not provided, directory will be scanned. -s [S] Search term -c [C] File containing JSON formatted cookies to set in driver (with target URL only) -i [I] Count of pages to crawl (with target URL only) --p Flag, remove unnecessary parameters (may dramatically increase runtime)

You can search for API calls made on a single page for a single search term. For example, you can search a page on http://target.com for an API returning product data to populate the product page:

$python consoleservice.py -u https://www.target.com/p/rogue-one-a-star-wars-\story-blu-ray-dvd-digital-3-disc/-/A-52030319 -s"Rogue One: A Star Wars Story"

This returns information, including a URL, for an API that returns product data for that page:

URL: https://redsky.target.com/v2/pdp/tcin/52030319

METHOD: GET

AVG RESPONSE SIZE: 34834

SEARCH TERM CONTEXT: c":"786936852318","product_description":{"title":

"Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (Blu-ray + DVD + Digital) 3 Disc",

"long_description":...

Using the -i flag, multiple pages can be crawled (this defaults to just one page), starting from the provided URL. This can be useful for searching all network traffic for particular keywords, or, by omitting the -s search term flag, collecting all API traffic that occurs when loading each page.

All collected data is stored as a HAR file, in the default directory /har in the project root, although this directory can be changed with the -d flag.

If no URL is provided, you can also pass in a directory of precollected HAR files for searching and analysis.

This project provides many other features, including the following:

-

Unnecessary parameter removal (removing

GETorPOSTparameters that do not influence the return value of the API call) -

Multiple API output formats (command line, HTML, JSON)

-

Distinguishing between path parameters that indicate a separate API route, and path parameters that act merely as

GETparams for the same API route

Further development is also planned as I, and others, continue to use it for web scraping and API collection.

Combining APIs with Other Data Sources

Although the raison d'être of many modern web applications is to take existing data and format it in a more appealing way, I would argue that this isn’t an interesting thing to do in most instances. If you’re using an API as your only data source, the best you can do is merely copy someone else’s database that already exists, and which is, essentially, already published. What can be far more interesting is to take two or more data sources and combine them in a novel way, or use an API as a tool to look at scraped data from a new perspective.

Let’s look at one example of how data from APIs can be used in conjunction with web scraping to see which parts of the world contribute the most to Wikipedia.

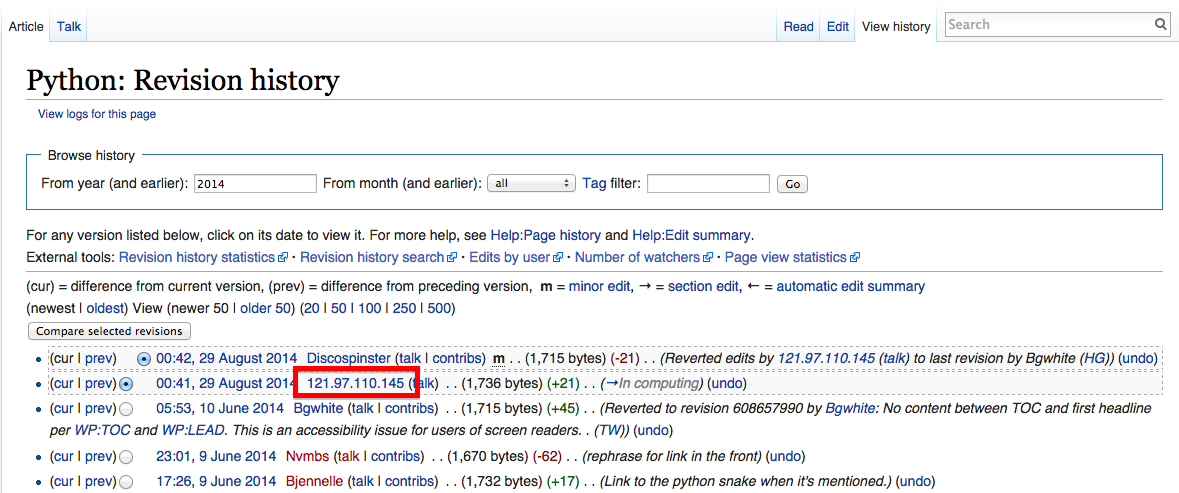

If you’ve spent much time on Wikipedia, you’ve likely come across an article’s revision history page, which displays a list of recent edits. If users are logged into Wikipedia when they make the edit, their username is displayed. If they are not logged in, their IP address is recorded, as shown in Figure 12-2.

Figure 12-2. The IP address of an anonymous editor on the revision history page for Wikipedia’s Python entry

The IP address provided on the history page is 121.97.110.145. By using the ip-api.com API, that IP address is from Quezon, Philippines as of this writing (IP addresses can occasionally shift geographically).

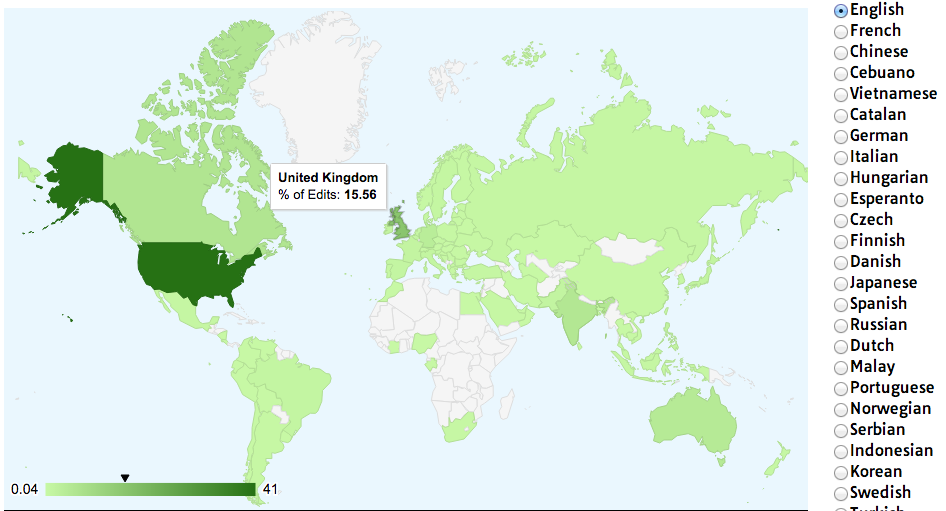

This information isn’t all that interesting on its own, but what if you could gather many points of geographic data about Wikipedia edits and where they occur? A few years ago, I did just that and used Google’s GeoChart library to create an interesting chart that shows where edits on the English-language Wikipedia, along with the Wikipedias written in other languages, originate from (Figure 12-3).

Figure 12-3. Visualization of Wikipedia edits created using Google’s GeoChart library

Creating a basic script that crawls Wikipedia, looks for revision history pages, and then looks for IP addresses on those revision history pages isn’t difficult. Using modified code from Chapter 3, the following script does just that:

fromurllib.requestimporturlopenfrombs4importBeautifulSoupimportjsonimportdatetimeimportrandomimportrerandom.seed(datetime.datetime.now())defgetLinks(articleUrl):html=urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(articleUrl))bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')returnbs.find('div',{'id':'bodyContent'}).find_all('a',href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)((?!:).)*$'))defgetHistoryIPs(pageUrl):#Format of revision history pages is:#http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Title_in_URL&action=historypageUrl=pageUrl.replace('/wiki/','')historyUrl='http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title={}&action=history'.format(pageUrl)('history url is: {}'.format(historyUrl))html=urlopen(historyUrl)bs=BeautifulSoup(html,'html.parser')#finds only the links with class "mw-anonuserlink" which has IP addresses#instead of usernamesipAddresses=bs.find_all('a',{'class':'mw-anonuserlink'})addressList=set()foripAddressinipAddresses:addressList.add(ipAddress.get_text())returnaddressListlinks=getLinks('/wiki/Python_(programming_language)')while(len(links)>0):forlinkinlinks:('-'*20)historyIPs=getHistoryIPs(link.attrs['href'])forhistoryIPinhistoryIPs:(historyIP)newLink=links[random.randint(0,len(links)-1)].attrs['href']links=getLinks(newLink)

This program uses two main functions: getLinks (which was also used in Chapter 3), and the new getHistoryIPs, which searches for the contents of all links with the class mw-anonuserlink (indicating an anonymous user with an IP address, rather than a username) and returns it as a set.

This code also uses a somewhat arbitrary (yet effective for the purposes of this example) search pattern to look for articles from which to retrieve revision histories. It starts by retrieving the histories of all Wikipedia articles linked to by the starting page (in this case, the article on the Python programming language). Afterward, it randomly selects a new starting page, and retrieves all revision history pages of articles linked to by that page. It will continue until it hits a page with no links.

Now that you have code that retrieves IP addresses as a string, you can combine this with the getCountry function from the previous section in order to resolve these IP addresses to countries. You’ll modify getCountry slightly, in order to account for invalid or malformed IP addresses that will result in a 404 Not Found error:

defgetCountry(ipAddress):try:response=urlopen('http://ip-api.com/json/{}'.format(ipAddress)).read().decode('utf-8')exceptHTTPError:returnNoneresponseJson=json.loads(response)returnresponseJson.get('country_code')links=getLinks('/wiki/Python_(programming_language)')while(len(links)>0):forlinkinlinks:('-'*20)historyIPs=getHistoryIPs(link.attrs["href"])forhistoryIPinhistoryIPs:country=getCountry(historyIP)ifcountryisnotNone:('{} is from {}'.format(historyIP,country))newLink=links[random.randint(0,len(links)-1)].attrs['href']links=getLinks(newLink)

------------------- history url is: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Programming_ paradigm&action=history 68.183.108.13 is from US 86.155.0.186 is from GB 188.55.200.254 is from SA 108.221.18.208 is from US 141.117.232.168 is from CA 76.105.209.39 is from US 182.184.123.106 is from PK 212.219.47.52 is from GB 72.27.184.57 is from JM 49.147.183.43 is from PH 209.197.41.132 is from US 174.66.150.151 is from US

More About APIs

This chapter has shown a few ways that modern APIs are commonly used to access data on the web, and how those APIs can be used to build faster and more powerful web scrapers. If you’re looking to build APIs instead of just using them, or if you want to learn more about the theory of their construction and syntax, I recommend RESTful Web APIs by Leonard Richardson, Mike Amundsen, and Sam Ruby (O’Reilly). This book provides a strong overview of the theory and practice of using APIs on the web. In addition, Mike Amundsen has a fascinating video series, Designing APIs for the Web (O’Reilly), that teaches you how to create your own APIs—a useful thing to know if you decide to make your scraped data available to the public in a convenient format.

While some might bemoan the ubiquity of JavaScript and dynamic websites, making traditional “grab and parse the HTML page” practices outdated, I, for one, welcome our new robot overlords. As dynamic websites rely less on HTML pages for human consumption and more on strictly formatted JSON files for HTML consumption, this provides a boon for everyone trying to get clean, well-formatted data.

The web is no longer a collection of HTML pages with occasional multimedia and CSS adornments. It’s a collection of hundreds of file types and data formats, whizzing hundreds at a time to form the pages that you consume through your browser. The real trick is often to look beyond the page in front of you and grab the data at its source.

1 This API resolves IP addresses to geographic locations and is one you’ll be using later in the chapter as well.

2 In reality, many APIs use POST requests in lieu of PUT requests when updating information. Whether a new entity is created or an old one is merely updated is often left to how the API request itself is structured. However, it’s still good to know the difference, and you will often encounter PUT requests in commonly used APIs.