Chapter 25. HTML5 Audio and Video

One of the biggest driving forces behind the growth of the internet has been the insatiable demand from users for ever more multimedia in the form of audio and video. Initially, bandwidth was so precious that there was no such thing as live streaming, and it could take minutes or even hours to download an audio track, let alone a video.

The high cost of bandwidth and limited availability of fast modems drove the development of faster and more efficient compression algorithms, such as MP3 audio and MPEG video, but even then the only way to download files in any reasonable length of time was to drastically reduce their quality.

One of my earlier internet projects, back in 1997, was the UK’s first online radio station licensed by the music authorities. Actually, it was more of a podcast (before the term was coined) because we made a daily half-hour show and then compressed it down to 8-bit, 11 KHz mono using an algorithm originally developed for telephony, and it sounded like phone quality, or worse. Still, we quickly gained thousands of listeners who would download the show and then listen to it as they surfed to the sites discussed in it by means of a pop-up browser window containing a plug-in.

Thankfully for us, and everyone publishing multimedia, it soon became possible to offer greater audio and video quality, but still only by asking the user to download and install a plug-in player. Flash became the most popular of these players, after beating rivals such as RealAudio, but it gained a bad reputation as the cause of many a browser crash, and constantly required upgrading when new versions were released.

So, it was generally agreed that the way ahead was to come up with some web standards for supporting multimedia directly within the browser. Of course, browser developers such as Microsoft and Google had differing visions of what these standards should look like, but when the dust settled, they had agreed on a subset of file types that all browsers should play natively, and these were introduced into the HTML5 specification.

Finally, it is possible (as long as you encode your audio and video in a few different formats) to upload multimedia to a web server, place a couple of HTML tags in a web page, and play the media on any major desktop browser, smartphone, or tablet device, without the user having to download a plug-in or make any other changes.

Note

There are still a lot of older browsers out there, so Flash remains important to support them. In this chapter, I show you how to add code to use Flash as a backup to HTML5 audio and video, to cover as many hardware and software combinations as possible.

About Codecs

The term codec stands for encoder/decoder. It describes the functionality provided by software that encodes and decodes media such as audio and video. In HTML5 there are a number of different sets of codecs available, depending on the browser used.

One complication around audio and video, which rarely applies to graphics and other traditional web content, is the licensing carried by the formats and codecs. Many formats and codecs are provided for a fee, because they were developed by a single company or consortium of companies that chose a proprietary license. Some free and open source browsers don’t support the most popular formats and codecs because it is unfeasible to pay for them, or because the developers oppose proprietary licenses in principle. Because copyright laws vary from country to country and because licenses are hard to enforce, the codecs can usually be found on the web for no cost, but they might technically be illegal to use where you live.

Following are the codecs supported by the HTML5 <audio> tag (and also when audio is attached to HTML5 video):

- AAC

- This audio codec, which stands for Advanced Audio Encoding, is used by Apple’s iTunes store and is a proprietary patented technology supported by Apple, Google, and Microsoft. It generally uses the .aac file extension. Its MIME type is

audio/aac. - MP3

- This audio codec, which stands for MPEG Audio Layer 3, has been available for many years. Although the term is often (incorrectly) used to refer to any type of digital audio, it is a proprietary patented technology that is supported by Apple, Google, Mozilla Firefox, and Microsoft. The file extension it uses is .mp3. Its mime type is

audio/mpeg. - PCM

- This audio codec, which stands for Pulse Coded Modulation, stores the full data as encoded by an analog-to-digital converter, and is the format used for storing data on audio CDs. Because it does not use compression, it is called a lossless codec and its files are generally many times larger than AAC or MP3 files. It is supported by Apple, Mozilla Firefox, Microsoft, and Opera. Usually this type of file has the extension .wav. Its MIME type is

audio/wav, but you may also seeaudio/wave. - Vorbis

- Sometimes referred to as Ogg Vorbis—because it generally uses the .ogg file extension—this audio codec is unencumbered by patents and free of royalty payments. It is supported by Google, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera. Its MIME type is

audio/ogg, or sometimesaudio/oga.

The following list summarizes the major operating systems and browsers, along with the audio types their latest versions support:

-

Apple iOS: AAC, MP3, PCM

-

Apple Safari: AAC, MP3, PCM

-

Google Android: 2.3+ AAC, MP3, Vorbis

-

Google Chrome: AAC, MP3, Vorbis

-

Microsoft Internet Explorer: AAC, MP3, PCM

-

Microsoft Edge: AAC, MP3, PCM

-

Mozilla Firefox: MP3, PCM, Vorbis

-

Opera: PCM, Vorbis

The outcome of these different levels of codec support is that you always need at least two versions of each audio file to ensure it will play on all platforms. These could be PCM and AAC, PCM and MP3, PCM and Vorbis, AAC and Vorbis, or MP3 and Vorbis.

The <audio> Element

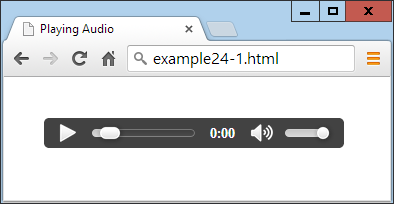

To cater to all platforms, you need to record or convert your content using multiple codecs and then list them all within <audio> and </audio> tags, as in Example 25-1. The nested <source> tags then contain the various media you wish to offer to a browser. Because the controls attribute is supplied, the result looks like Figure 25-1.

Example 25-1. Embedding three different types of audio files

<audio controls> <source src='audio.m4a' type='audio/aac'> <source src='audio.mp3' type='audio/mp3'> <source src='audio.ogg' type='audio/ogg'> </audio>

Figure 25-1. Playing an audio file

In this example I included three different audio types, because that’s perfectly acceptable, and can be a good idea if you wish to ensure that each browser can locate its preferred format rather than just one it knows how to handle. However, you can drop either (but not both) of the MP3 or the AAC files and still be confident that the example will play on all platforms.

The <audio> element and its partner <source> tag support several attributes:

autoplay- Causes the audio to start playing as soon as it is ready

controls- Causes the control panel to be displayed

loop- Sets the audio to play over and over

preload- Causes the audio to begin loading even before the user selects Play

src- Specifies the source location of an audio file

type- Specifies the codec used in creating the audio

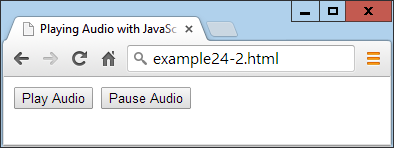

If you don’t supply the controls attribute to the <audio> tag, and don’t use the autoplay attribute either, the sound will not play and there won’t be a Play button for the user to click to start playback. This would leave you no option other than to offer this functionality in JavaScript, as in Example 25-2 (with the additional code required highlighted in bold), which provides the ability to play and pause the audio, as shown in Figure 25-2.

Example 25-2. Playing audio using JavaScript

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Playing Audio with JavaScript</title>

<script src='OSC.js'></script>

</head>

<body>

<audio id='myaudio'>

<source src='audio.m4a' type='audio/aac'>

<source src='audio.mp3' type='audio/mp3'>

<source src='audio.ogg' type='audio/ogg'>

</audio>

<button onclick='playaudio()'>Play Audio</button>

<button onclick='pauseaudio()'>Pause Audio</button>

<script>

function playaudio()

{

O('myaudio').play()

}

function pauseaudio()

{

O('myaudio').pause()

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

Figure 25-2. HTML5 audio can be controlled with JavaScript

This works by calling the play or pause methods of the myaudio element when the buttons are clicked.

Supporting Non-HTML5 Browsers

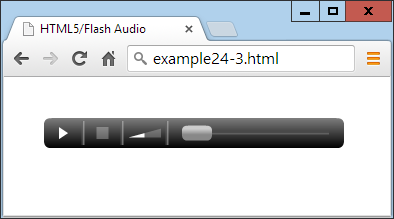

In very rare cases (such as when developing web pages for in-house intranets that are using older browsers), it may be necessary for you to fall back to Flash for handling audio. Example 25-3 shows how you can do this using a Flash plug-in called audioplayer.swf that’s available, along with all the examples, in the archive file on the book’s companion website. The code to add is highlighted in bold.

Example 25-3. Providing a Flash fallback for non-HTML5 browsers

<audio controls>

<object type="application/x-shockwave-flash"

data="audioplayer.swf" width="300" height="30">

<param name="FlashVars"

value="mp3=audio.mp3&showstop=1&showvolume=1">

</object>

<source src='audio.m4a' type='audio/aac'>

<source src='audio.mp3' type='audio/mp3'>

<source src='audio.ogg' type='audio/ogg'>

</audio>

Here we take advantage of the fact that non-HTML5 browsers read and act on anything inside the <audio> tag (other than the <source> elements, which are ignored). Therefore, by placing an <object> element there that calls up a Flash player, we ensure that any non-HTML5 browsers will at least have a chance of playing the audio, as long as they have Flash installed, as shown in Figure 25-3.

Figure 25-3. The Flash audio player has been loaded

The particular audio player used in this example, audioplayer.swf, takes the following arguments and values to the FlashVars attribute of the <param> element:

mp3- The URL of an MP3 audio file.

showstop- If

1, the display shows the Stop button; otherwise, it is not displayed. showvolume- If

1, the display shows the volume bar; otherwise, it is not displayed.

As with many elements, you can easily resize the object to (for example) 300 × 30 pixels by providing these values to its width and height attributes.

The <video> Element

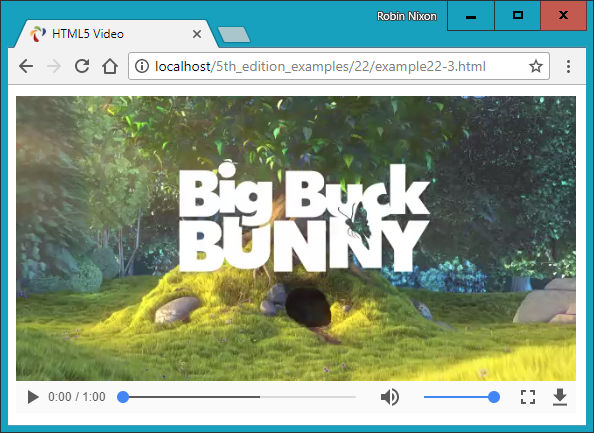

Playing video in HTML5 is quite similar to audio; you just use the <video> tag and provide <source> elements for the media you are offering. Example 25-4 shows how to do this with three different video codec types, as displayed in Figure 25-4.

Example 25-4. Playing HTML5 video

<video width='560' height='320' controls> <source src='movie.mp4' type='video/mp4'> <source src='movie.webm' type='video/webm'> <source src='movie.ogv' type='video/ogg'> </video>

Figure 25-4. Playing HTML5 video

The Video Codecs

As with audio, there are a number of video codecs available, with differing support across multiple browsers. These codecs come in different containers, as follows:

- MP4

- A license-encumbered, multimedia container format standard specified as a part of MPEG-4, supported by Apple, Microsoft, and to a lesser extent Google (which has its own WebM container format). Its MIME type is

video/mp4. - Ogg

- A free, open container format maintained by the Xiph.Org Foundation. The creators of the Ogg format state that it is unrestricted by software patents and is designed to provide for efficient streaming and manipulation of high-quality digital multimedia. Its MIME type is

video/ogg, or sometimesvideo/ogv. - WebM

- An audio-video format designed to provide a royalty-free, open video compression format for use with HTML5 video. The project’s development is sponsored by Google. There are two versions: VP8 and the newer VP9. Its MIME type is

video/webm.

These may then contain one of the following video codecs:

- H.264

- A patented, proprietary video codec that can be played back for free by the end user, but which may incur royalty fees for all parts of the encoding and transmission process. At the time of writing, all of the Apple, Google, Mozilla Firefox, and Microsoft browsers support this codec, while Opera (the remaining major browser) doesn’t.

- Theora

- A video codec that is unencumbered by patents and free of royalty payments at all levels of encoding, transmission, and playback. This codec is supported by Google, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera.

- VP8

- A video codec that is similar to Theora but is owned by Google, which has published it as open source, making it royalty-free. It is supported by Google, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera.

- VP9

- The same as VP8 but more powerful, using half the bitrate.

The following list details the major operating systems and browsers, along with the video types their latest versions support:

-

Apple iOS: MP4/H.264

-

Apple Safari: MP4/H.264

-

Google Android: MP4, Ogg, WebM/H.264, Theora, VP8

-

Google Chrome: MP4, Ogg, WebM/H.264, Theora, VP8, VP9

-

Microsoft Internet Explorer: MP4/H.264

-

Microsoft Edge: MP4/H.264, WebM/H.264

-

Mozilla Firefox: MP4, Ogg, WebM/H.264, Theora, VP8, VP9

-

Opera: Ogg, WebM/Theora, VP8

Looking at this list, it’s clear that MP4/H.264 is almost unanimously supported, except by the Opera browser. So, to reach over 96% of users, you only need to supply your video using that one file type. But for maximum viewing, you really ought to encode in Ogg/Theora or Ogg/VP8 as well.

Therefore, the movie.webm file in Example 25-4 isn’t strictly needed, but it shows how you can add all the different file types you like, to give browsers the opportunity to play back the formats they prefer.

The <video> element and accompanying <source> tag support the following attributes:

autoplay- Causes the video to start playing as soon as it is ready

controls- Causes the control panel to be displayed

height- Specifies the height at which to display the video

loop- Sets the video to play over and over

muted- Mutes the audio output

poster- Lets you choose an image to display where the video will play

preload- Causes the video to begin loading before the user selects Play

src- Specifies the source location of a video file

type- Specifies the codec used in creating the video

width- Specifies the width at which to display the video

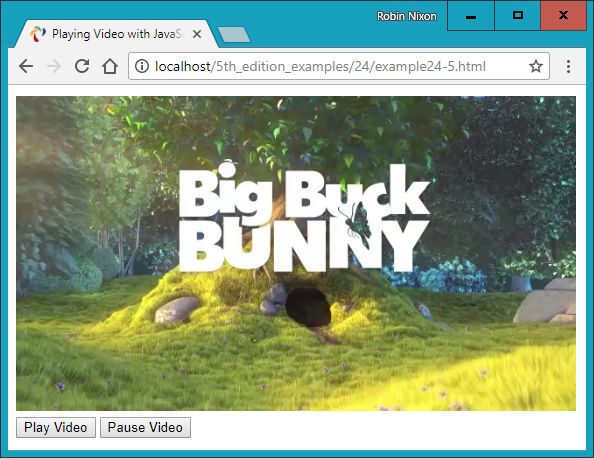

If you wish to control video playback from JavaScript, you can do so using code such as that in Example 25-5 (with the additional code required highlighted in bold), with the results shown in Figure 25-5.

Example 25-5. Controlling video playback from JavaScript

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Playing Video with JavaScript</title>

<script src='OSC.js'></script>

</head>

<body>

<video id='myvideo' width='560' height='320'>

<source src='movie.mp4' type='video/mp4'>

<source src='movie.webm' type='video/webm'>

<source src='movie.ogv' type='video/ogg'>

</video><br>

<button onclick='playvideo()'>Play Video</button>

<button onclick='pausevideo()'>Pause Video</button>

<script>

function playvideo()

{

O('myvideo').play()

}

function pausevideo()

{

O('myvideo').pause()

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

This code is just like that for controlling audio from JavaScript. Simply call the play and/or pause methods of the myvideo object to play and pause the video.

Supporting Older Browsers

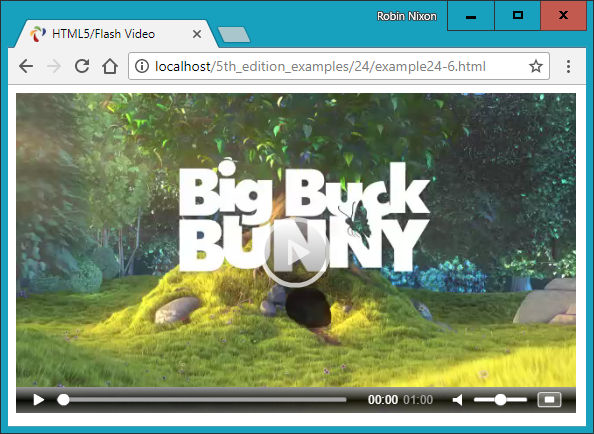

If you find yourself having to develop for non-HTML5–capable browsers, Example 25-6 shows you how to do this (highlighted in bold) using the flowplayer.swf file (included with the example archive available on the book’s companion website). Figure 25-6 shows how it displays in a browser that doesn’t support HTML5 video.

Example 25-6. Providing Flash as a fallback video player

<video width='560' height='320' controls>

<object width='560' height='320'

type='application/x-shockwave-flash'

data='flowplayer.swf'>

<param name='movie' value='flowplayer.swf'>

<param name='flashvars'

value='config={"clip": {

"url": "movie.mp4",

"autoPlay":false, "autoBuffering":true}}'>

</object>

<source src='movie.mp4' type='video/mp4'>

<source src='movie.webm' type='video/webm'>

<source src='movie.ogv' type='video/ogg'>

</video>

Figure 25-6. Flash provides a handy fallback for non-HTML5 browsers

This Flash video player is particular about security; it won’t play videos from a local filesystem, only from a web server, so I have supplied a file on the book’s companion website for this example to play.

Here are the arguments to supply to the flashvars attribute of the <param> element:

urlA URL of an .mp4 file to play (must be on a web server)

autoPlayIf

true, plays automatically; otherwise, waits for the Play button to be clickedautoBufferingIf

true, in order to minimize buffering later on with slow connections, preloads the video sufficiently for the available bandwidth before it starts playing

Note

For more information on the Flash flowplayer program (and an HTML5 version), check out flowplayer.org.

Using the information in this chapter, you will be able to embed any audio and video you like on almost all browsers and platforms without worrying about whether users may or may not be able to play it.

In the following chapter, I’ll demonstrate the use of a number of other HTML5 features, including geolocation and local storage.

Questions

-

Which two HTML element tags are used to insert audio and video into an HTML5 document?

-

How many audio codecs should you use to guarantee maximum playability on all platforms?

-

Which methods can you call to play and pause HTML5 media playback?

-

How can you support media playback in a non-HTML5 browser?

-

Which two video codecs should you use to guarantee maximum playability on all platforms?

See “Chapter 25 Answers” in Appendix A for the answers to these questions.