Chapter 23. Introduction to HTML5

HTML5 represents a substantial leap forward in web design, layout, and usability. It provides a simple way to manipulate graphics in a web browser without resorting to plug-ins such as Flash, offers methods to insert audio and video into web pages (again without plug-ins), and irons out several annoying inconsistencies that crept into HTML during its evolution.

In addition, HTML5 includes numerous other enhancements such as geolocation handling, web workers to manage background tasks, improved form handling, and access to bundles of local storage (far in excess of the limited capabilities of cookies).

What’s interesting about HTML5, though, is that it has been an ongoing evolution, in which browsers have adopted different features at different times. Fortunately, all the biggest and most popular HTML5 additions are now supported by all major browsers (those with more than 1 percent or so of the market, such as Chrome, Internet Explorer, Edge, Firefox, Safari, Opera, and the Android and iOS browsers).

The Canvas

Originally introduced by Apple for the WebKit rendering engine (which had itself originated in the KDE HTML layout engine) for its Safari browser (and now also implemented in the iOS, Android, Kindle, Chrome, BlackBerry, Opera, and Tizen browsers), the canvas element enables us to draw graphics in a web page without having to rely on a plug-in such as Java or Flash. After being standardized, the canvas was adopted by all other browsers and is now a mainstay of modern web development.

Like other HTML elements, a canvas is simply an element within a web page with defined dimensions, and within which you can use JavaScript to insert content—in this case, to draw graphics. You create a canvas by using the <canvas> tag, to which you must assign an ID so that JavaScript will know which canvas it is accessing (as you can have more than one canvas on a page).

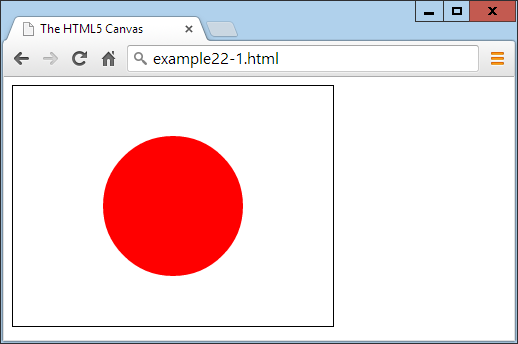

In Example 23-1 I’ve created a canvas element, with the ID mycanvas, that contains some text that is displayed only in browsers that don’t support the canvas. Beneath this there is a section of JavaScript that draws the Japanese flag on the canvas (as shown in Figure 23-1).

Example 23-1. Using the HTML5 canvas element

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>The HTML5 Canvas</title>

<script src='OSC.js'></script>

</head>

<body>

<canvas id='mycanvas' width='320' height='240'>

This is a canvas element given the ID <i>mycanvas</i>

This text is visible only in non-HTML5 browsers

</canvas>

<script>

canvas = O('mycanvas')

context = canvas.getContext('2d')

context.fillStyle = 'red'

S(canvas).border = '1px solid black'

context.beginPath()

context.moveTo(160, 120)

context.arc(160, 120, 70, 0, Math.PI * 2, false)

context.closePath()

context.fill()

</script>

</body>

</html>

Figure 23-1. Drawing the Japanese flag using an HTML5 canvas

At this point, it’s not necessary to detail exactly what is going on—I explain that in Chapter 24—but you should already see that using the canvas is not hard, although it does require learning a few new JavaScript functions. Note that this example draws on the OSC.js set of functions from Chapter 20 to help keep the code neat and compact.

Geolocation

Using geolocation, your browser can return information to a web server about your location. This information can come from a GPS chip in the computer or mobile device you’re using, from your IP address, or from analysis of nearby WiFi hotspots. For security purposes, the user is always in control and can refuse to provide this information on a one-off basis, or can enable settings to either permanently block or allow access to this data from one or all websites.

There are numerous uses for this technology, including giving you turn-by-turn navigation; providing local maps; notifying you of nearby restaurants, WiFi hotspots, or other places; letting you know which friends are near you; directing you to the nearest gas station; and more.

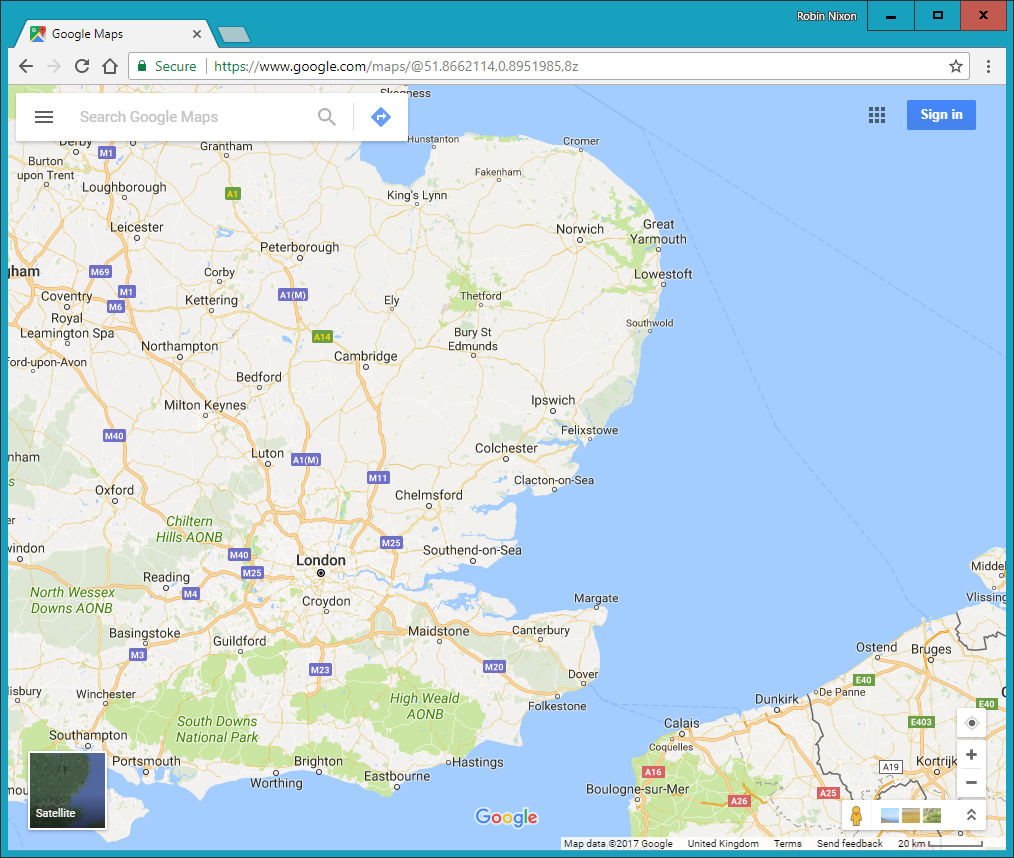

Example 23-2 will display a Google map of the user’s location, as long as the browser supports geolocation and the user grants access to location data (as shown in Figure 23-2). Otherwise, it will display an error.

Example 23-2. Displaying a map of the user’s location

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Geolocation Example</title>

</head>

<body>

<script>

if (typeof navigator.geolocation == 'undefined')

alert("Geolocation not supported.")

else

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(granted, denied)

function granted(position)

{

var lat = position.coords.latitude

var lon = position.coords.longitude

alert("Permission Granted. You are at location:\n\n"

+ lat + ", " + lon +

"\n\nClick 'OK' to load Google Maps with your location")

window.location.replace("https://www.google.com/maps/@"

+ lat + "," + lon + ",14z")

}

function denied(error)

{

var message

switch(error.code)

{

case 1: message = 'Permission Denied'; break;

case 2: message = 'Position Unavailable'; break;

case 3: message = 'Operation Timed Out'; break;

case 4: message = 'Unknown Error'; break;

}

alert("Geolocation Error: " + message)

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

Figure 23-2. The user’s location has been used to display a map

Again, here is not the place to describe how this all works; I will detail that in Chapter 26. For now, though, this example serves to show you how easy managing geolocation can be.

Audio and Video

Another great addition to HTML5 is support for in-browser audio and video. While playing these types of media can be a little complicated due to the variety of encoding types and licenses, the <audio> and <video> elements provide the flexibility you need to display the types of media you have available.

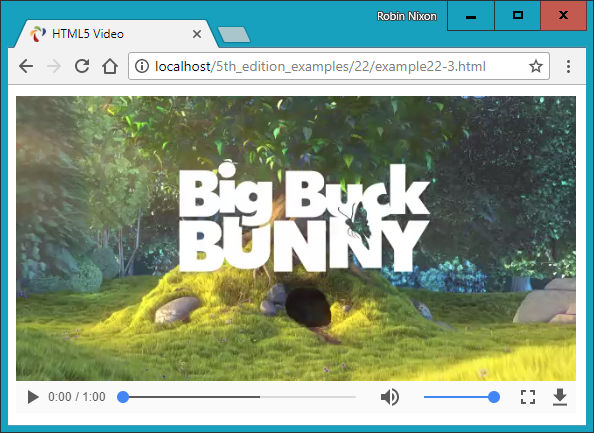

In Example 23-3, the same video file has been encoded in different formats to ensure that all major browsers are accounted for. Browsers will simply select the first type they recognize and play it, as shown in Figure 23-3.

Example 23-3. Playing a video with HTML5

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>HTML5 Video</title>

</head>

<body>

<video width='560' height='320' controls>

<source src='movie.mp4' type='video/mp4'>

<source src='movie.webm' type='video/webm'>

<source src='movie.ogv' type='video/ogg'>

</video>

</body>

</html>

Figure 23-3. Displaying video using HTML5

Inserting audio into a web page is just as easy, as you will discover in Chapter 25.

Forms

As you already saw in Chapter 11, HTML5 forms are in the process of being enhanced, but support across all browsers remains patchy. What you can safely use today has been detailed in Chapter 11.

Local Storage

With local storage, the amount and complexity of data you can save on a local device is substantially increased from the meager space provided by cookies. This opens up the possibility of using web apps to work on documents offline and then syncing them with the web server only when an internet connection is available. It also raises the prospect of storing small databases locally for access with WebSQL, perhaps for keeping a copy of your music collection’s details, or all your personal statistics as part of a diet or weight loss plan, for example. In Chapter 26, I show you how to make the most of this new facility in your web projects.

Web Workers

It has been possible to run interrupt-driven applications in the background using JavaScript for many years, but only through a clumsy and inefficient process. It makes much more sense to let the underlying browser technology run background tasks on your behalf, which it can do far more quickly than you can by continuously interrupting the browser to check how things are going.

Instead, with web workers you set everything up and pass your code to the web browser, which then runs it. When anything significant occurs, your code simply has to notify the browser, which then reports back to your main code. In the meantime, your web page can be doing nothing or a number of other tasks, and can forget about the background task until it makes itself known.

In Chapter 26, I demonstrate how you can use web workers to create a simple clock and to calculate prime numbers.

Microdata

In Chapter 26, I also show how you can mark up your code with microdata to make it totally understandable to any browser or other technology that needs to access it. Microdata is sure to become more and more important to search engine optimization too, so it’s important that you begin to incorporate it or at least understand what information it can provide about your websites.

As you can see, there’s quite a lot to HTML5—many people have waited a long time for these goodies, but they’re finally here. Starting with the canvas, the following few chapters will explain these features to you in glorious detail, so you can be up and running with them, and enhancing your websites, in no time.

Questions

-

What new HTML5 element enables drawing of graphics in web pages?

-

What programming language is required to access many of the advanced HTML5 features?

-

Which HTML5 tags would you use to incorporate audio and video in a web page?

-

What feature is new in HTML5 and offers greater capability than cookies?

-

Which HTML5 technology supports running background JavaScript tasks?

See “Chapter 23 Answers” in Appendix A for the answers to these questions.