Chapter 17. Functions at a Glance

This chapter lists the functions in the standard library according to their respective areas of application, describing shared features of the functions and their relationships to one another. This compilation might help you to find the right function for your purposes while programming.

Tip

The individual functions are described in detail in Chapter 18, which explains them in alphabetical order, with examples.

The alternative functions with bounds-checking introduced in C11, also called the secure functions, are listed in Tables 17-1 and 17-2. The names of these functions end with the suffix _s (s for “secure”), as in scanf_s(). Note that C implementations are not required to support the secure functions. For more information on using the secure functions, see “Functions with Bounds-Checking”.

Input and Output

We have dealt with this topic in detail in Chapter 13, which contains sections on I/O streams, sequential and random file access, formatted I/O, and error handling. A tabular list of the I/O functions will therefore suffice here. Table 17-1 lists general file access functions declared in the header stdio.h.

| Purpose | Functions |

|---|---|

Rename a file, delete a file |

|

Create and/or open a file |

|

Close a file |

|

Generate a unique filename |

|

Query or clear file access flags |

|

Query the current file access position |

|

Change the current file access position |

|

Write buffer contents to file |

|

Control file buffering |

|

There are two complete sets of functions for input and output of characters and strings: the byte-character and the wide-character I/O functions (see “Byte-Oriented and Wide-Oriented Streams” for more information). The wide-character functions operate on characters with the type wchar_t, and are declared in the header wchar.h. Table 17-2 lists both sets.

| Purpose | Functions in stdio.h | Functions in wchar.h |

|---|---|---|

Get/set stream orientation |

|

|

Write characters |

|

|

Read characters |

|

|

Put back characters read |

|

|

Write lines |

|

|

Read lines |

|

|

Write blocks |

|

|

Read blocks |

|

|

Write formatted strings |

|

|

Read formatted strings |

|

|

For each function in the printf and scanf families, there is a secure alternative function whose name ends in the suffix _s.

Mathematical Functions

The standard library provides many mathematical functions. Most of them operate on real or complex floating-point numbers. However, there are also several functions with integer types, such as the functions to generate random numbers.

The functions to convert numeral strings into arithmetic types are listed in “String Processing”. The remaining math functions are described in the following subsections.

Mathematical Functions for Integer Types

The math functions for the integer types are declared in the header stdlib.h. Two of these functions, abs() and div(), are declared in three variants to operate on the three signed integer types int, long, and long long. As Table 17-3 shows, the functions for the type long have names beginning with the letter l; those for long long begin with ll. Furthermore, the header inttypes.h declares function variants for the type intmax_t, with names that begin with imax.

| Purpose | Functions declared in stdlib.h | Functions declared in stdint.h |

|---|---|---|

Absolute value |

|

|

Division |

|

|

Random numbers |

|

Floating-Point Functions

The functions for real floating-point types are declared in the header math.h, and those for complex floating-point types are declared in complex.h. Table 17-4 lists the functions that are available for both real and complex floating-point types. The complex versions of these functions have names that start with the prefix c. Table 17-5 lists the functions that are only defined for the real types; and Table 17-6 lists the functions that are specific to complex types.

For the sake of readability, Tables 17-4 through 17-6 show only the names of the functions for the types double and double _Complex. Each of these functions also exists in variants for the types float (or float _Complex) and long double (or long double _Complex). The names of these variants end in the suffix f for float or l for long double. For example, the functions sin() and csin() listed in Table 17-4 also exist in the variants sinf(), sinl(), csinf(), and csinl() (but see also “Type-generic macros”).

| Mathematical function | C functions in math.h | C functions in complex.h |

|---|---|---|

Trigonometry |

|

|

Hyperbolic trigonometry |

|

|

Exponential function |

|

|

Natural logarithm |

|

|

Powers, square root |

|

|

Absolute value |

|

|

| Mathematical function | C function |

|---|---|

Arctangent of a quotient |

|

Exponential functions |

|

Logarithmic functions |

|

Roots |

|

Error functions for normal distributions |

|

Gamma function |

|

Remainder |

|

Separate integer and fractional parts |

|

Next integer |

|

Next representable number |

|

Rounding functions |

|

Positive difference |

|

Multiply and add |

|

Minimum and maximum |

|

Assign one number’s sign to another |

|

Generate a NaN |

|

| Mathematical function | C function |

|---|---|

Isolate real and imaginary parts |

|

Argument (the angle in polar coordinates) |

|

Conjugate |

|

Project onto the Riemann sphere |

|

Function-Like Macros

The standard headers math.h and tgmath.h define a number of function-like macros that can be invoked with arguments of different floating-point types. Variable argument types in C are supported only in macros, not in function calls.

Type-generic macros

Each floating-point math function exists in three or six different versions: one for each of the three real types, or for each of the three complex types, or for both real and complex types. The header tgmath.h defines the type-generic macros, which allow you to call any version of a given function under a uniform name. The compiler detects the appropriate function from the arguments’ type. Thus, you do not need to edit the math function calls in your programs when you change an argument’s type from double to long double, for example. The type-generic macros are described in “tgmath.h”.

Categories of floating-point values

C99 defines five kinds of values for the real floating-point types, with distinct integer macros to designate them (see the section on math.h in Chapter 16):

FP_ZERO FP_NORMAL FP_SUBNORMAL FP_INFINITE FP_NAN

These classification macros, and the function-like macros listed in Table 17-7, are defined in the header math.h. The argument of each of the function-like macros must be an expression with a real floating-point type.

| Purpose | Function-like macros |

|---|---|

Get the category of a floating-point value |

|

Test whether a floating-point value belongs to a certain category |

|

For example, the following two tests are equivalent:

if(fpclassify(x)==FP_INFINITE)/* ... */;if(isinf(x))/* ... */;

Comparison macros

Any two real, finite floating-point numbers can be compared. In other words, one is always less than, equal to, or greater than the other. However, if one or both operands of a comparative operator is a NaN—a floating-point value that is not a number—for example, then the operands are not comparable. In this case, the operation yields the value 0, or “false,” and may raise the floating-point exception FE_INVALID.

In practice, you may want to avoid risking an exception when comparing floating-point objects. For this reason, the header math.h defines the function-like macros listed in Table 17-8. These macros yield the same results as the corresponding expressions with comparative operators, but perform a “quiet” comparison; that is, they never raise exceptions, but simply return false if the operands are not comparable. The two arguments of each macro must be expressions with real floating-point types.

| Comparison | Function-like macro |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Test for comparability |

|

a Unlike the corresponding operator expression, the function-like macro | |

Pragmas for Arithmetic Operations

The following two standard pragmas influence the way in which arithmetic expressions are compiled:

#pragma STDC FP_CONTRACT on_off_switch #pragma STDC CX_LIMITED_RANGE on_off_switch

The value of on_off_switch must be ON, OFF, or DEFAULT. If switched ON, the first of these pragmas, FP_CONTRACT, allows the compiler to contract floating-point expressions with several C operators into fewer machine operations, if possible. Contracted expressions are faster in execution. However, because they also eliminate rounding errors, they may not yield precisely the same results as uncontracted expressions. Furthermore, an uncontracted expression may raise floating-point exceptions that are not raised by the corresponding contracted expression. It is up to the compiler to determine how contractions are performed, and whether expressions are contracted by default.

The second pragma, CX_LIMITED_RANGE, affects the multiplication, division, and absolute values of complex numbers. These operations can cause problems if their operands are infinite, or if they result in invalid overflows or underflows. When switched ON, the pragma CX_LIMITED_RANGE instructs the compiler that it is safe to use simple arithmetic methods for these three operations, as only finite operands will be used, and no overflows or underflows need to be handled. By default, this pragma is switched OFF.

In source code, these pragma directives can be placed outside all functions, or at the beginning of a block, before any declarations or statements. The pragmas take effect from the point where they occur in the source code. If a pragma directive is placed outside all functions, its effect ends with the next directive that invokes the same pragma, or at the end of the translation unit. If the pragma directive is placed within a block, its effect ends with the next directive that invokes the same pragma in a nested block, or at the end of the containing block. At the end of a block, the compiler behavior returns to the state that was in effect at the beginning of the block.

The Floating-Point Environment

The floating-point environment consists of system variables for floating-point status flags and control modes. Status flags are set by operations that raise floating-point exceptions, such as division by zero. Control modes are features of floating-point arithmetic behavior that programs can set, such as the way in which results are rounded to representable values. Support for floating-point exceptions and control modes is optional.

All of the declarations involved in accessing the floating-point environment are contained in the header fenv.h (see Chapter 16).

Programs that access the floating-point environment should inform the compiler beforehand by means of the following standard pragma:

#pragma STDC FENV_ACCESS ONThis directive prevents the compiler from applying optimizations, such as changes in the order in which expressions are evaluated, that might interfere with querying status flags or applying control modes.

FENV_ACCESS can be applied in the same ways as FP_CONTRACT and CX_LIMITED_RANGE: outside all functions, or locally within a block (see the preceding section). It is up to the compiler whether the default state of FENV_ACCESS is ON or OFF.

Accessing status flags

The functions in Table 17-9 allow you to access the exception status flags. One argument to these functions indicates the kind or kinds of exceptions to operate on. The following integer macros are defined in the header fenv.h to designate the individual exception types:

FE_DIVBYZERO FE_INEXACT FE_INVALID FE_OVERFLOW FE_UNDERFLOW

Each of these macros is defined only if the implementation supports the corresponding exception. The macro FE_ALL_EXCEPT designates all the supported exception types.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Test floating-point exceptions |

|

Clear floating-point exceptions |

|

Raise floating-point exceptions |

|

Save floating-point exceptions |

|

Restore floating-point exceptions |

|

Rounding modes

The floating-point environment also includes the rounding mode currently in effect for floating-point operations. The header fenv.h defines a distinct integer macro for each supported rounding mode. Each of the following macros is defined only if the implementation supports the corresponding rounding direction:

FE_DOWNWARD FE_TONEAREST FE_TOWARDZERO FE_UPWARD

Implementations may also define other rounding modes and macro names for them. The values of these macros are used as return values or as argument values by the functions listed in Table 17-10.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Get the current rounding mode |

|

Set a new rounding mode |

|

Saving the whole floating-point environment

The functions listed in Table 17-11 operate on the floating-point environment as a whole, allowing you to save and restore the floating-point environment’s state.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Save the floating-point environment |

|

Restore the floating-point environment |

|

Save the floating-point environment and switch to nonstop processing |

|

Restore a saved environment and raise any exceptions that are currently set |

|

a In the nonstop processing mode activated by a call to | |

Error Handling

C99 defines the behavior of the functions declared in math.h in cases of invalid arguments or mathematical results that are out of range. The value of the macro math_errhandling, which is constant throughout a program’s runtime, indicates whether the program can handle errors using the global error variable errno, or the exception flags in the floating-point environment, or both.

Domain errors

A domain error occurs when a function is mathematically not defined for a given argument value. For example, the real square root function sqrt() is not defined for negative argument values. The domain of each function in math.h is indicated in the description of the function in Chapter 18.

In the case of a domain error, functions return a value determined by the implementation. In addition, if the expression math_errhandling & MATH_ERRNO is not equal to zero—in other words, if the expression is true—then a function incurring a domain error sets the error variable errno to the value of EDOM. If the expression math_errhandling & MATH_ERREXCEPT is true, then the function raises the floating-point exception FE_INVALID.

Range errors

A range error occurs if the mathematical result of a function is not representable in the function’s return type without a substantial rounding error. An overflow occurs if the range error is due to a mathematical result whose magnitude is finite, but too large to be represented by the function’s return type. If the default rounding mode is in effect when an overflow occurs, or if the exact result is infinity, then the function returns the value of HUGE_VAL (or HUGE_VALF or HUGE_VALL, if the function’s type is float or long double) with the appropriate sign. In addition, if the expression math_errhandling & MATH_ERRNO is true, then the function sets the error variable errno to the value of ERANGE. If the expression math_errhandling & MATH_ERREXCEPT is true, then an overflow raises the exception FE_OVERFLOW if the mathematical result is finite, or FE_DIVBYZERO if it is infinite.

An underflow occurs when a range error is due to a mathematical result whose magnitude is nonzero, but too small to be represented by the function’s return type. When an underflow occurs, the function returns a value that is defined by the implementation but less than or equal to the value of DBL_MIN (or FLT_MIN, or LDBL_MIN, depending on the function’s type). The implementation also determines whether the function sets the error variable errno to the value of ERANGE if the expression math_errhandling & MATH_ERRNO is true. Furthermore, the implementation defines whether an underflow raises the exception FE_UNDERFLOW if the expression math_errhandling & MATH_ERREXCEPT is true.

Character Classification and Conversion

The standard library provides a number of functions to classify characters and to perform conversions on them. The header ctype.h declares such functions for byte characters, with character codes from 0 to 255. The header wctype.h declares similar functions for wide characters, which have the type wchar_t. These functions are commonly implemented as macros.

The results of these functions, except for isdigit() and isxdigit(), depends on the current locale setting for the locale category LC_CTYPE. You can query or change the locale using the setlocale() function.

Character Classification

The functions listed in Table 17-12 test whether a character belongs to a certain category. Their return value is nonzero, or true, if the argument is a character code in the given category.

| Category | Functions in ctype.h | Functions in wctype.h |

|---|---|---|

Letters |

|

|

Lowercase letters |

|

|

Uppercase letters |

|

|

Decimal digits |

|

|

Hexadecimal digits |

|

|

Letters and decimal digits |

|

|

Printable characters (including whitespace) |

|

|

Printable, non-whitespace characters |

|

|

Whitespace characters |

|

|

Whitespace characters that separate words in a line of text |

|

|

Punctuation marks |

|

|

Control characters |

|

|

The functions isgraph() and iswgraph() behave differently if the execution character set contains other byte-coded, printable, whitespace characters (that is, whitespace characters that are not control characters) in addition to the space character (' '). In that case, iswgraph() returns false for all such printable whitespace characters, while isgraph() returns false only for the space character (' ').

The header wctype.h also declares the two additional functions listed in Table 17-13 to test wide characters. These are called the extensible classification functions, which you can use to test whether a wide-character value belongs to an implementation-defined category designated by a string.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Map a string argument that designates a character class to a scalar value that can be used as the second argument to |

|

Test whether a wide character belongs to the class designated by the second argument |

|

The two functions in Table 17-13 can be used to perform at least the same tests as the functions listed in Table 17-12. The strings that designate the character classes recognized by wctype() are formed from the name of the corresponding test functions, minus the prefix isw. For example, the string "alpha", like the function name iswalpha(), designates the category “letters.” Thus, for a wide-character value wc, the following tests are equivalent:

iswalpha(wc)iswctype(wc,wctype("alpha"))

Implementations may also define other such strings to designate locale-specific character classes.

Case Mapping

The functions listed in Table 17-14 yield the uppercase letter that corresponds to a given lowercase letter, and vice versa. All other argument values are returned unchanged.

| Conversion | Functions in ctype.h | Functions in wctype.h |

|---|---|---|

Upper- to lowercase |

|

|

Lower- to uppercase |

|

|

Here again, as in the previous section, the header wctype.h declares two additional extensible functions to convert wide characters. These are described in Table 17-15. Each kind of character conversion supported by the given implementation is designated by a string.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Map a string argument that designates a character conversion to a scalar value that can be used as the second argument to |

|

Perform the conversion designated by the second argument on a given wide character |

|

The two functions in Table 17-15 can be used to perform at least the same conversions as the functions listed in Table 17-14. The strings that designate those conversions are "tolower" and "toupper". Thus, for a wide-character wc, the following two calls have the same result:

towupper(wc);towctrans(wc,wctrans("toupper"));

Implementations may also define other strings to designate locale-specific character conversions.

String Processing

A string is a continuous sequence of characters terminated by '\0', the string terminator character. The length of a string is considered to be the number of characters before the string terminator. Strings can be either byte strings, which consist of byte characters, or wide strings, which consist of wide characters. Byte strings are stored in arrays of char, and wide strings are stored in arrays whose elements have one of the wide-character types: wchar_t, char16_t, or char32_t.

C does not have a basic type for strings, and hence has no operators to concatenate, compare, or assign values to strings. Instead, the standard library provides numerous functions, listed in Table 17-16, to perform these and other operations with strings. The header string.h declares the functions for conventional strings of char. The names of these functions begin with str. The header wchar.h declares the corresponding functions for strings of wide characters, with names beginning with wcs.

Like any other array, a string that occurs in an expression is implicitly converted into a pointer to its first element. Thus, when you pass a string as an argument to a function, the function receives only a pointer to the first character, and can determine the length of the string only by the position of the string terminator character.

| Purpose | Functions in string.h | Functions in wchar.h |

|---|---|---|

Find the length of a string |

|

|

Copy a string |

|

|

Concatenate strings |

|

|

Compare strings |

|

|

Transform a string so that a comparison of two transformed strings using |

|

|

In a string, find: |

||

… the first or last occurrence of a given character |

|

|

… the first occurrence of another string |

|

|

… the first occurrence of any of a given set of characters |

|

|

… the first character that is not a member of a given set |

|

|

Parse a string into tokens |

|

|

Multibyte Characters

In multibyte character sets, each character is coded as a sequence of one or more bytes (see “Wide Characters and Multibyte Characters”). While each wide character is represented by one object of the type wchar_t, char16_t, or char32_t, the number of bytes necessary to represent a given character in a multibyte encoding is variable. However, the number of bytes that represent a multibyte character, including any necessary state-shift sequences, is never more than the value of the macro MB_CUR_MAX, which is defined in the header stdlib.h.

Standard library functions allow you to obtain the character code of the wide character corresponding to any multibyte character, and the multibyte representation of any wide character. Some multibyte encoding schemes are stateful; the interpretation of a given multibyte sequence may depend on its position with respect to control characters, called shift sequences, that are used in the multibyte stream or string. In such cases, the conversion of a multibyte character to a wide character, or the conversion of a multibyte string into a wide string, depends on the current shift state at the point where the first multibyte character is read. For the same reason, converting a wide character to a multibyte character, or a wide string to a multibyte string, may entail inserting appropriate shift sequences in the output. An example of a multibyte-encoding that uses shift sequences is BOCU-1, a MIME-compatible, compressed Unicode encoding that takes up less space than UTF-8. UTF-8 itself, on the other hand, does not use shift sequences.

Conversions between wide and multibyte characters or strings may be necessary when you read or write characters from a wide-oriented stream (see “Byte-Oriented and Wide-Oriented Streams”).

Table 17-17 lists all of the standard library functions for handling multibyte characters.

| Purpose | Functions in stdlib.h | Functions in wchar.h | Functions in uchar.h |

|---|---|---|---|

Find the length of a multibyte character |

|

|

|

Find the wide character corresponding to a given multibyte character |

|

|

|

Find the multibyte character corresponding to a given wide character |

|

|

|

Convert a multibyte string into a wide string |

|

|

|

Convert a wide string into a multibyte string |

|

|

|

Convert between byte characters and wide characters |

|

||

Test for the initial shift state |

|

The letter r in the names of functions declared in wchar.h stands for “restartable.” The restartable functions—in contrast to those declared in stdlib.h, without the r in their names—take an additional argument, which is a pointer to an object that stores the shift state of the multibyte character or string argument.

Converting Between Numbers and Strings

The standard library provides a variety of functions to interpret a numeral string and return a numeric value. These functions are listed in Table 17-18. The numeral conversion functions differ both in their target types and in the string types they interpret. The functions for char strings are declared in the header stdlib.h, and those for wide strings in wchar.h. Furthermore, C99 introduced four functions to convert a string into a number of the widest available signed or unsigned integer type, intmax_t or uintmax_t. These four functions are declared in inttypes.h.

| Conversion | Functions in stdlib.h | Functions in wchar.h | Functions in inttypes.h |

|---|---|---|---|

String to |

|

||

String to |

|

|

|

String to |

|

|

|

String to |

|

|

|

String to |

|

|

|

String to |

|

||

String to |

|

||

String to |

|

|

|

String to |

|

|

|

String to |

|

|

The functions strtol(), strtoll(), and strtod() can be more practical to use than the corresponding functions atol(), atoll(), and atof(), as they return the position of the next character in the source string after the character sequence that was interpreted as a numeral.

In addition to the functions listed in Table 17-18, you can also perform string-to-number conversions using one of the sscanf() functions with an appropriate format string. Similarly, you can use the sprintf() functions to perform the reverse conversion, generating a numeral string from a numeric argument. These functions are declared in the header stdio.h. Once again, the corresponding functions for wide strings are declared in the header wchar.h. Both sets of functions are listed in Table 17-19.

| Conversion | Functions in stdio.h | Functions in wchar.h |

|---|---|---|

String to number |

|

|

Number to string |

|

|

For each of these functions, there is a secure alternative function whose name ends in the suffix _s.

Searching and Sorting

Table 17-20 lists the standard library’s four general searching and sorting functions, which are declared in the header stdlib.h. The functions to search the contents of a string are listed in “String Processing”.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Sort an array |

|

Search a sorted array |

|

These functions feature an abstract interface that allows you to use them for arrays of any element type. One parameter of the qsort() and qsort_s() functions is a pointer to a call-back function that qsort() and qsort_s() can use to compare pairs of array elements. Usually you will need to define this function yourself. The bsearch() and bsearch_s() functions, which find the array element designated by a “key” argument, use the same technique, calling a user-defined function to compare array elements with the specified key.

The bsearch() and bsearch_s() functions use the binary search algorithm, and therefore require that the array be sorted beforehand. Although the names of the qsort() and qsort_s() functions suggest that they implement the quick-sort algorithm, the standard does not specify which sorting algorithm they use.

Memory Block Handling

The functions listed in Table 17-21 initialize, copy, search, and compare blocks of memory. The functions declared in the header string.h access a memory block byte by byte, and those declared in wchar.h read and write units of the type wchar_t. Accordingly, the size parameter of each function indicates the size of a memory block as a number of bytes, or as a number of wide characters.

| Purpose | Functions in string.h | Functions in wchar.h |

|---|---|---|

| Copy a memory block, where source and destination do not overlap | memcpy(), memcpy_s() |

wmemcpy(), wmemcpy_s() |

| Copy a memory block, where source and destination may overlap | memmove(), memmove_s() |

wmemmove(), wmemmove_s() |

| Compare two memory blocks | memcmp() |

wmemcmp() |

| Find the first occurrence of a given character | memchr() |

wmemchr() |

| Fill the memory block with a given character value | memset(), memset_s() |

wmemset(), wmemset_s() |

Dynamic Memory Management

Many programs, including those that work with dynamic data structures, for example, depend on the ability to allocate and release blocks of memory at runtime. C programs can do that by means of the four dynamic memory management functions declared in the header stdlib.h, which are listed in Table 17-22. The use of these functions is described in detail in Chapter 12.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Allocate a block of memory |

|

Allocate a memory block and fill it with null bytes |

|

Resize an allocated memory block |

|

Release a memory block |

|

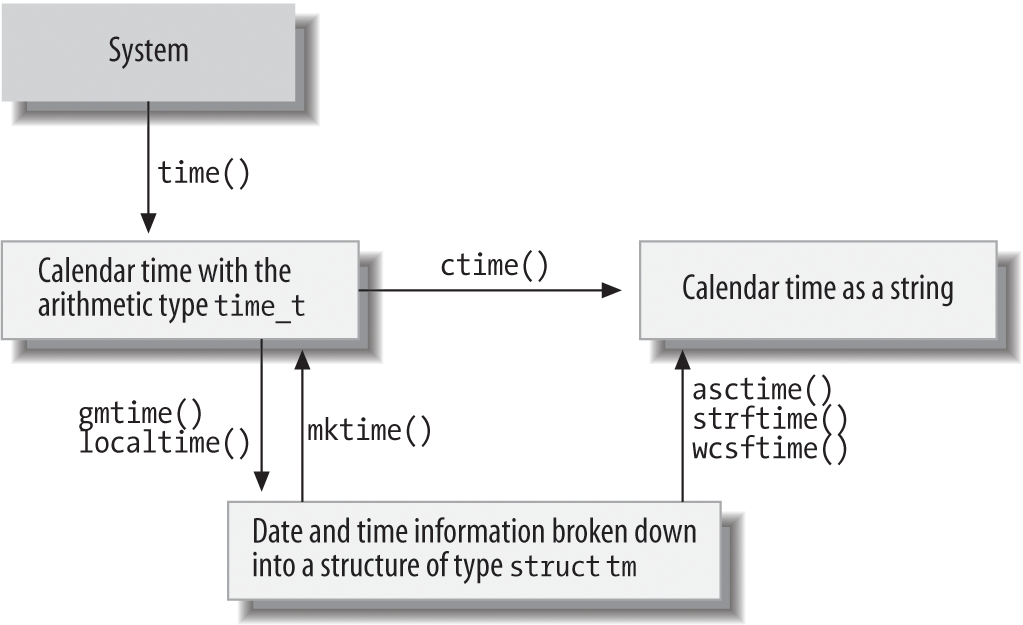

Date and Time

The header time.h declares the standard library functions to obtain the current date and time, to obtain the process’s running time, to perform certain conversions on date and time information, and to format it for output. A key function is time(), which yields the current calendar time in the form of an arithmetic value of the type time_t. This is usually encoded as the number of seconds elapsed since a specified moment in the past, called the epoch. The Unix epoch is 00:00:00 o’clock on January 1, 1970, UTC (Coordinated Universal Time, formerly called Greenwich Mean Time or GMT).

There are also standard functions to convert a calendar time value with the type time_t into a string or a structure of type struct tm. The structure type has members of type int for the second, minute, hour, day, month, year, day of the week, day of the year, and a daylight saving time flag (see the description of the gmtime() function in Chapter 18). Table 17-23 lists all the date and time functions.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Get the amount of CPU time used |

|

Get the current calendar time |

|

Get the difference between two calendar times |

|

Convert calendar time to |

|

Convert calendar time to |

|

Normalize the values of a |

|

Convert calendar time to a string |

|

The extremely flexible strftime() function uses a format string (in a similar way as the printf() functions) and the LC_TIME locale category to generate a date and time string. You can query or change the locale using the setlocale() function. The function wcsftime() is the wide-string version of strftime(), and is declared in the header wchar.h rather than time.h.

The diagram in Figure 17-1 offers an organized summary of the available date and time functions.

Figure 17-1. Date and time functions

Process Control

A process is a program that is being executed. Each process has a number of attributes, such as its open files. The exact attributes of processes are dependent on the given system. The standard library’s process control features can be divided into two kinds: those for communication with the operating system, and those concerned with signals.

Communication with the Operating System

The functions in Table 17-24 are declared in the header stdlib.h, and allow programs to communicate with the operating system.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Query the value of an environment variable |

|

Execute a system command |

|

Register a function to be executed when the program exits |

|

Exit the program normally |

|

Exit the program abruptly |

|

In Unix and Windows, one attribute of a process is the environment, which consists of a list of strings of the form name=value. Usually, a process inherits an environment generated by its parent process. The getenv() function is one way for a program to receive control information, such as the names of directories containing files to use.

In contrast to exit(), the _Exit() function ignores all signals, and does not call any functions registered by atexit(). The quick_exit() function, introduced in C99, first calls all the functions that have been registered by calls to the at_quick_exit() function, and then terminates the program by calling _Exit(). The abort() function causes an abnormal program termination by raising the SIGABRT signal.

Signals

An operating system sends various signals to processes to notify them of unusual events. Such events typically include severe errors, such as illegal memory access, or hardware interrupts such as timer alarms. Signals may also be caused by a user at the console, however, or by the program itself calling the raise() function.

Each program may determine for itself how to react to specific signals. A program can choose to ignore signals, let the default signal handler deal with them, or install its own signal handler function. A signal handler is a function that is executed automatically when the program receives a given type of signal.

The two C functions that deal with signals are declared, along with macros to designate the signal types, in the header signal.h. The functions are listed in Table 17-25.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Set the response to a given signal type |

|

Send a signal to the calling process |

|

Internationalization

The standard library supports the development of C programs that are able to adapt to local cultural conventions. For example, programs may use locale-specific character sets or formats for currency information.

All programs start in the default locale, named "C", which contains no country or language-specific information. During runtime, programs can change their locale or query information about the current locale. The information that makes up a locale is divided into categories, which you can query and set individually.

The functions that operate on the current locale are declared, along with the related types and macros, in the header locale.h. They are listed in Table 17-26.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Query or set the locale for a specified category of information |

|

Get information about the local formatting conventions for numeric and monetary strings |

|

Many functions make use of locale-specific information. The standard library function descriptions in Chapter 18 point out whenever a given function accesses locale settings. Such functions include the following:

Nonlocal Jumps

The goto statement in C can be used to jump only within a function. For greater freedom, the header setjmp.h declares a pair of functions that permit jumps to any point in a program. Table 17-27 lists these functions.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Save the current execution context as a jump target for the |

|

Jump to a program context saved by a call to the |

|

When you call the function-like macro setjmp(), it stores a value in its argument with the type jmp_buf that acts as a bookmark to that point in the program. The jmp_buf object holds all the necessary parts of the current execution state (including registers and stack). When you pass a jmp_buf object to longjmp(), longjmp() restores the saved state, and the program continues at the point following the earlier setjmp() call. The longjmp() call must not occur after the function that called setjmp() returns. Furthermore, if any variables with automatic storage duration in the function that called setjmp() were modified after the setjmp() call (and were not declared as volatile), then their values after the longjmp() call are indeterminate.

The return value of setjmp() indicates whether the program has reached that point after the original setjmp() call, or through a longjmp() call: setjmp() itself returns 0. If setjmp() appears to return any other value, then that point in the program was reached by calling longjmp(). If the second argument in the longjmp() call—that is, the requested return value—is 0, it is replaced with 1 as the apparent return value after the corresponding setjmp() call.

Multithreading (C11)

The features provided by the C11 standard for programming multithreaded applications in C are described in detail in Chapter 14. The tables in this section simply present a summary of the C multithreading library. Note that support for multithreading and atomic operations is optional. An implementation that conforms to C11 must simply define the macros __STDC_NO_THREADS__ and __STDC_NO_ATOMICS__ if it does not provide the corresponding features.

Thread Functions

The threads library provides functions for the following kinds of tasks:

-

Managing threads

-

Synchronizing thread execution using mutex objects

-

Using condition variables for communication between threads

-

Thread-specific storage

Accordingly, the names of the multithreading functions begin with one of the prefixes thrd_, mtx_, cnd_, or tss_. The only exception is the function call_once() (see Table 17-28). All of these functions are declared in the header threads.h.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Call a function exactly once |

|

call_once() guarantees that only the first call to the function specified by the argument will be executed. This is useful in initializing data to be shared among several threads, for example.

The functions listed in Table 17-29 perform operations on a program’s threads of execution, such as starting and stopping them.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Create and start a new thread to execute a specified function |

|

Get the ID of the thread performing this function call |

|

Test whether two thread IDs refer to the same thread |

|

Suspend execution of the current thread for a specified time |

|

Advise the system to let other threads run |

|

Terminate the current thread |

|

Wait for another thread to terminate |

|

Disown a thread |

|

C provides the functions listed in Table 17-30 to synchronize different threads’ work using mutexes.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Create and initialize a mutex |

|

Lock a mutex; block until it becomes available |

|

Lock a mutex only if it becomes available within a specified time |

|

Lock a mutex only if it is available now |

|

Destroy a specified mutex |

|

Condition variables are used for communication between a program’s various threads, as when one thread needs to notify others that certain data are available, for example. Table 17-31 lists all the functions provided for working with condition variables.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Initialize a condition variable |

|

Wake up one of the threads waiting for a condition variable |

|

Wake up all the threads waiting for a condition variable |

|

Wait for a condition variable until woken up by another thread |

|

Wait a limited time for a condition variable |

|

Destroy a condition variable |

|

The four functions listed in Table 17-32 operate on thread-specific storage (TSS). Multiple threads use a global key that represents each thread’s pointer to a thread-specific memory block.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Create a TSS key and optionally specify a destructor to be called when a thread exits |

|

Set the memory block for the current thread to access using a given key |

|

Get the pointer to the current thread’s memory block for the given key |

|

Release the resources used by a TSS key |

|

Atomic Operations

The function declarations and the definitions of types and macros for atomic operations are contained in the header stdatomic.h.

The macro ATOMIC_VAR_INIT can be used to initialize atomic objects. The macros of the form _ATOMIC_type_LOCK_FREE indicate whether an atomic object with the corresponding integer type type has the “lock-free” property. (For details, see “stdatomic.h”.). The generic functions listed in Table 17-33 can also be used as an alternative to these macros.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Initialize an atomic object |

|

Test whether an atomic object is lock-free |

|

Reading or writing an atomic object is an atomic operation. “Read-modify-write” operations, like those performed by the increment and decrement operators (++ and --), and by the compound assignment operators (+= etc.) when the left operand is an atomic object, are also atomic operations. Initializing an atomic object is not an atomic operation, however.

Besides the operators named, the standard library provides a number of functions to perform atomic operations, such as atomic_load(). By default, atomic operations are performed with the strictest memory-ordering constraint: sequential consistency. To perform atomic operations with lower memory-ordering constraints, another version of each atomic operation function takes an additional argument to explicitly specify a memory-ordering constraint. The latter functions have names that end in _explicit, such as atomic_load_explicit(). For details on these functions, see “Memory Ordering”.

The generic functions listed in Table 17-34 can be used with objects of all the atomic types that are defined in stdatomic.h. For a complete list of these types, see “stdatomic.h”.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

| Get the value of an atomic object | atomic_load(), atomic_load_explicit() |

| Write a value to an atomic object | atomic_store(), atomic_store_explicit() |

| Get the existing value and write a new value | atomic_exchange(), atomic_exchange_explicit() |

| Compare the value of an atomic object with an expected value; if equal, write a new value to the object | atomic_compare_exchange_strong(),atomic_compare_exchange_strong_explicit(),atomic_compare_exchange_weak(),atomic_compare_exchange_weak_explicit() |

| Replace the value of an integer atomic object with the result of an arithmetic operation or a bit operation; unlike the corresponding compound assignments, these functions return the object’s original value before the operation | atomic_fetch_add(), atomic_fetch_add_explicit(), atomic_fetch_sub(), atomic_fetch_sub_explicit(),atomic_fetch_or(), atomic_fetch_or_explicit(),atomic_fetch_xor(), atomic_fetch_xor_explicit(), atomic_fetch_and(), atomic_fetch_and_explicit() |

Objects of the type atomic_flag are guaranteed to be lock-free. The functions listed in Table 17-35 provide the usual flag-operations for atomic_flag objects.

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Clear an atomic flag |

|

Set an atomic flag and return its prior state |

|

Memory fences specify the memory-ordering constraint that must be observed in the synchronization of atomic write and read operations (see “Fences” for more information).

| Purpose | Function |

|---|---|

Insert an acquire, release, or acquire-and-release fence |

|

Insert a fence that applies ordering constraints only between the operations in a thread and in a signal handler executed in that thread |

|

Debugging

Using the macro assert() is a simple way to find logical mistakes during program development. This macro is defined in the header assert.h. It simply tests its scalar argument for a nonzero value. If the argument’s value is zero, assert() prints an error message that lists the argument expression, function, filename, and line number, and then calls abort() to stop the program. In the following example, the assert() calls perform some plausibility checks on the argument to be passed to free():

#include <stdlib.h>#include <assert.h>char*buffers[64]={NULL};// An array of pointersinti;/* ... allocate some memory buffers; work with them ... */assert(i>=0&&i<64);// Index out of range?assert(buffers[i]!=NULL);// Was the pointer used at all?free(buffers[i]);

Rather than trying to free a nonexistent buffer, this code aborts the program (here compiled as assert.c) with the following diagnostic output:

assert: assert.c:14: main: Assertion 'buffers[i] != ((void *)0)' failed. Aborted

When you have finished testing, you can disable all assert() calls by defining the macro NDEBUG before the #include directive for assert.h. The macro does not need to have a replacement value. For example:

#define NDEBUG#include <assert.h>/* ... */

C11 has introduced the capability to test the assertion of an integer constant expression during compiling. This is done using _Static_assert declarations. For details and an example, see “_Static_assert Declarations”.

Error Messages

Various standard library functions set the global variable errno to a value indicating the type of error encountered during execution (see “errno.h”). The functions in Table 17-37 generate an appropriate error message for the current value of errno.

| Purpose | Function | Header |

|---|---|---|

Print an appropriate error message on stderr for the current value of errno |

perror() |

stdio.h |

| Return a pointer to the appropriate error message for a given error number | strerror() |

string.h |

Copy the error message corresponding to a given errno value to an array |

strerror_s() |

string.h |

Find the length of the error message corresponding to a given errno value |

strerrorlen_s() |

string.h |

The function perror() prints the string passed to it as an argument, followed by a colon and the error message that corresponds to the value of errno. This error message is the one that strerror() would return if called with the same value of errno as its argument. Here is an example:

if(remove("test1")!=0)// If we can't delete the file ...perror("Couldn't delete 'test1'");

This perror() call produces the same output as the following statement:

fprintf(stderr,"Couldn't delete 'test1': %s\n",strerror(errno));

In this example, if the file test1 does not exist, a program compiled with GCC prints the following message:

Couldn't delete 'test1': No such file or directory

The error message whose address is provided by the function strerror() may be replaced on a subsequent strerror() call. To avoid data races, multithreaded programs should therefore use the alternative function strerror_s(), which copies the error message to an array provided by the caller.