Chapter 7. Functions

All the instructions of a C program are contained in functions. Each function performs a certain task. A special function name is main()—the function with this name is the first one to run when the program starts. All other functions are subroutines of the main() function (or otherwise dependent procedures, such as call-back functions), and can have any names you wish.

Every function is defined exactly once. A program can declare and call a function as many times as necessary.

Function Definitions

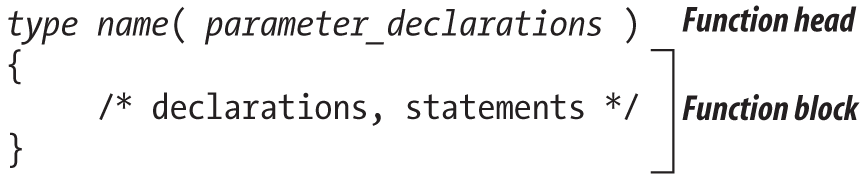

The definition of a function consists of a function head (or the declarator), and a function block. The function head specifies the name of the function, the type of its return value, and the types and names of its parameters, if any. The statements in the function block specify what the function does. The general form of a function definition is as follows:

In the function head, name is the function’s name, while type consists of at least one type specifier, which defines the type of the function’s return value. The return type may be void or any object type except array types. Furthermore, type may include one of the function specifiers inline or _Noreturn, and/or one of the storage class specifiers extern or static.

A function cannot return a function or an array. However, you can define a function that returns a pointer to a function or a pointer to an array.

The parameter declarations are contained in a comma-separated list of declarations of the function’s parameters. If the function has no parameters, this list is either empty or contains merely the word void.

The type of a function specifies not only its return type but also the types of all its parameters. Example 7-1 is a simple function to calculate the volume of a cylinder.

Example 7-1. Function cylinderVolume()

// The cylinderVolume() function calculates the volume of a cylinder.// Arguments: Radius of the base circle; height of the cylinder.// Return value: Volume of the cylinder.externdoublecylinderVolume(doubler,doubleh){constdoublepi=3.1415926536;// pi is constantreturnpi*r*r*h;}

This function has the name cylinderVolume, and has two parameters, r and h, both with type double. It returns a value with the type double.

Functions and Storage Class Specifiers

The function in Example 7-1 is declared with the storage class specifier extern. This is not strictly necessary, as extern is the default storage class for functions. An ordinary function definition that does not contain a static or inline specifier can be placed in any source file of a program. Such a function can be called in all of the program’s source files because its name is an external identifier (or in strict terms, an identifier with external linkage; see “Linkage of Identifiers”). You merely have to declare the function before its first use in a given translation unit (see “Function Declarations”). Furthermore, you can arrange functions in any order you wish within a source file. The only restriction is that you cannot define one function within another. C does not allow you to define “local functions” in this way.

You can hide a function from other source files. If you declare a function as static, its name identifies it only within the source file containing the function definition. Because the name of a static function is not an external identifier, you cannot use it in other source files. If you try to call such a function by its name in another source file, the linker will issue an error message, or the function call might refer to a different function with the same name elsewhere in the program.

The function printArray() in Example 7-2 might well be defined using static because it is a special-purpose helper function, providing formatted output of an array of float variables.

Example 7-2. Function printArray()

// The static function printArray() prints the elements of an array// of float to standard output, using printf() to format them.// Arguments: An array of float, and its length.// Return value: None.staticvoidprintArray(constfloatarray[],intn){for(inti=0;i<n;++i){printf("%12.2f",array[i]);// Field width: 12; decimal places: 2.if(i%5==4)putchar('\n');// New line after every 5 numbers.}if(n%5!=0)putchar('\n');// New line at the end of the output.}

If your program contains a call to the printArray() function before its definition, you must first declare it using the static keyword:

staticvoidprintArray(constfloat[],int);intmain(){floatfarray[123];/* ... */printArray(farray,123);/* ... */}

K&R-Style Function Definitions

In the early Kernighan-Ritchie standard, the names of function parameters were separated from their type declarations. Function declarators contained only the names of the parameters, which were then declared by type between the function declarator and the function block. For example, the cylinderVolume() function from Example 7-1 would have been written as follows:

doublecylinderVolume(r,h)doubler,h;// Parameter declarations{constdoublepi=3.1415926536;// pi is constantreturnpi*r*r*h;}

This notation, called a “K&R-style” or “old-style” function definition, is deprecated, although compilers still support it. In new C source code, use only the prototype notation for function definitions, as shown in Example 7-1.

Function Parameters

The parameters of a function are ordinary local variables. The program creates them and initializes them with the values of the corresponding arguments when a function call occurs. Their scope is the function block. A function can change the value of a parameter without affecting the value of the argument in the context of the function call. In Example 7-3, the factorial() function, which computes the factorial of a whole number, modifies its parameter n in the process.

Example 7-3. Function factorial()

// factorial() calculates n!, the factorial of a non-negative number n.// For n > 0, n! is the product of all integers from 1 to n inclusive.// 0! equals 1.// Argument: A whole number, with type unsigned int.// Return value: The factorial of the argument, with type long double.longdoublefactorial(registerunsignedintn){longdoublef=1;while(n>1)f*=n--;returnf;}

Although the factorial of an integer is always an integer, the function uses the type long double in order to accommodate very large results. As Example 7-3 illustrates, you can use the storage class specifier register in declaring function parameters. The register specifier is a request to the compiler to make a variable as quickly accessible as possible. (The compiler may ignore it.) No other storage class specifiers are permitted on function parameters.

Arrays as Function Parameters

If you need to pass an array as an argument to a function, you would generally declare the corresponding parameter in the following form:

type name[ ]

Because array names are automatically converted to pointers when you use them as function arguments, this statement is equivalent to the declaration:

type *name

When you use the array notation in declaring function parameters, any constant expression between the brackets ([ ]) is ignored. In the function block, the parameter name is a pointer variable, and can be modified. Thus, the function addArray() in Example 7-4 modifies its first two parameters as it adds pairs of elements in two arrays.

Example 7-4. Function addArray()

// addArray() adds each element of the second array to the corresponding// element of the first (i.e., "array1 += array2", so to speak).// Arguments: Two arrays of float and their common length.// Return value: None.voidaddArray(registerfloata1[],registerconstfloata2[],intlen){registerfloat*end=a1+len;for(;a1<end;++a1,++a2)*a1+=*a2;}

An equivalent definition of the addArray() function, using a different notation for the array parameters, would be:

voidaddArray(registerfloat*a1,registerconstfloat*a2,intlen){/* Function body as earlier. */}

An advantage of declaring the parameters with brackets ([ ]) is that human readers immediately recognize that the function treats the arguments as pointers to an array, and not just to an individual float variable. But the array-style notation also has two peculiarities in parameter declarations:

-

In a parameter declaration—and only there—C99 allows you to place any of the type qualifiers

const,volatile, andrestrictinside the square brackets. This ability allows you to declare the parameter as a qualified pointer type. -

Furthermore, in C99 you can also place the storage class specifier

static, together with a integer constant expression, inside the square brackets. This approach indicates that the number of elements in the array at the time of the function call must be at least equal to the value of the constant expression.

Here is an example that combines both of these possibilities:

intfunc(longarray[conststatic5]){/* ... */}

In the function defined here, the parameter array is a constant pointer to long, and so cannot be modified. It points to the first of at least five array elements.

C99 also lets you declare array parameters as variable-length arrays (see Chapter 8). To do so, place a nonconstant integer expression with a positive value between the square brackets. In this case, the array parameter is still a pointer to the first array element. The difference is that the array elements themselves can also have a variable length. In Example 7-5, the maximum() function’s third parameter is a two-dimensional array of variable dimensions.

Example 7-5. Function maximum()

// The function maximum() obtains the greatest value in a// two-dimensional matrix of double values.// Arguments: The number of rows, the number of columns, and the matrix.// Return value: The value of the greatest element.doublemaximum(intnrows,intncols,doublematrix[nrows][ncols]){doublemax=matrix[0][0];for(intr=0;r<nrows;++r)for(intc=0;c<ncols;++c)if(max<matrix[r][c])max=matrix[r][c];returnmax;}

The parameter matrix is a pointer to an array with ncols elements.

The main() Function

C makes a distinction between two possible execution environments:

- Freestanding

-

A program in a freestanding environment runs without the support of an operating system, and therefore only has minimal capabilities of the standard library available to it (see Part II).

- Hosted

-

In a hosted environment, a C program runs under the control, and with the support, of an operating system. The full capabilities of the standard library are available.

In a freestanding environment, the name and type of the first function invoked when the program starts is determined by the given implementation. Unless you program embedded systems, your C programs generally run in a hosted environment. A program compiled for a hosted environment must define a function with the name main, which is the first function invoked on program start. You can define the main() function in one of the following two forms:

int main( void ) { /* … */ }-

A function with no parameters, returning

int int main( int argc, char *argv[ ] ) { /* … */ }-

A function with two parameters whose types are

intandchar **, returningint

These two approaches conform to the C standard. In addition, many C implementations support a third, nonstandard syntax as well:

int main( int argc, char *argv[ ], char *envp[ ] ) { /* … */ }-

A function returning

int, with three parameters, the first of which has the typeint, while the other two have the typechar **

In all cases, the main() function returns its final status to the operating system as an integer. A return value of 0 or EXIT_SUCCESS indicates that the program was successful; any nonzero return value, and in particular the value of EXIT_FAILURE, indicates that the program failed in some way. The constants EXIT_SUCCESS and EXIT_FAILURE are defined in the header file stdlib.h. The function block of main() need not contain a return statement. In the C99 and later standards, if the program flow reaches the closing brace } of main()’s function block, the status value returned to the execution environment is 0. Ending the main() function is equivalent to calling the standard library function exit(), whose argument becomes the return value of main().

The parameters argc and argv (which you may give other names if you wish) represent your program’s command-line arguments. This is how they work:

-

argc(short for argument count) is either 0 or the number of string tokens in the command line that started the program. The name of the program itself is included in this count. -

argv(short for arguments vector) is an array of pointers tocharthat point to the individual string tokens received on the command line:-

The number of elements in this array is one more than the value of

argc; the last element,argv[argc], is always a null pointer. -

If

argcis greater than 0, then the first string,argv[0], contains the name by which the program was invoked. If the execution environment does not supply the program name, the string is empty. -

If

argcis greater than 1, then the stringsargv[1]throughargv[argc - 1]contain the program’s command-line arguments.

-

-

envp(short for environment pointer) in the nonstandard, three-parameter version ofmain()is an array of pointers to the strings that make up the program’s environment. Typically, these strings have the formname=value. In standard C, you can access the environment variables using thegetenv()function.

The sample program in Example 7-6, args.c, prints its own name and command-line arguments as received from the operating system.

Example 7-6. The command line

#include <stdio.h>intmain(intargc,char*argv[]){if(argc==0)puts("No command line available.");else{// Print the name of the program.printf("The program now running: %s\n",argv[0]);if(argc==1)puts("No arguments received on the command line.");else{puts("The command-line arguments:");for(inti=1;i<argc;++i)// Print each argument on// a separate line.puts(argv[i]);}}}

Suppose we run the program on a Unix system by entering the following command:

$ ./args one two "and three"

The output is then as follows:

The program now running: ./args The command-line arguments: one two and three

Function Declarations

By declaring a function before using it, you inform the compiler of its type: in other words, a declaration describes a function’s interface. A declaration must indicate at least the type of the function’s return value, as the following example illustrates:

intrename();

This line declares rename() as a function that returns a value with type int. Because function names are external identifiers by default, that declaration is equivalent to this one:

externintrename();

As it stands, this declaration does not include any information about the number and the types of the function’s parameters. As a result, the compiler cannot test whether a given call to this function is correct. If you call the function with arguments that are different in number or type from the parameters in its definition, the result will be a critical runtime error. To prevent such errors, you should always declare a function’s parameters as well. In other words, your declaration should be a function prototype. The prototype of the standard library function rename(), for example, which changes the name of a file, is as follows:

intrename(constchar*oldname,constchar*newname);

This function takes two arguments with type pointer to const char. In other words, the function uses the pointers only to read char objects. The arguments may thus be string literals.

The identifiers of the parameters in a prototype declaration are optional. If you include the names, their scope ends with the prototype itself. Because they have no meaning to the compiler, they are practically no more than comments telling programmers what each parameter’s purpose is. In the prototype declaration of rename(), for example, the parameter names oldname and newname indicate that the old filename goes first and the new filename second in your rename() function calls. To the compiler, the prototype declaration would have exactly the same meaning without the parameter names:

intrename(constchar*,constchar*);

The prototypes of the standard library functions are contained in the standard header files. If you want to call the rename() function in your program, you can declare it by including the file stdio.h in your source code. Usually you will place the prototypes of functions you define yourself in a header file as well so that you can use them in any source file simply by adding the appropriate include directive.

Declaring Optional Parameters

C allows you to define functions so that you can call them with a variable number of arguments (for more information on writing such functions, see “Variable Numbers of Arguments”). The best-known example of such a function is printf(), which has the following prototype:

intprintf(constchar*format,...);

As this example shows, the list of parameter types ends with an ellipsis (…) after the last comma. The ellipsis represents optional arguments. The first argument in a printf function call must be a pointer to char. This argument may be followed by others. The prototype contains no information about what number or types of optional arguments the function expects.

Declaring Variable-Length Array Parameters

When you declare a function parameter as a variable-length array elsewhere than in the head of the function definition, you can use the asterisk character (*) to represent the array-length specification. If you specify the array length using a nonconstant integer expression, the compiler will treat it the same as an asterisk. For example, all of the following declarations are permissible prototypes for the maximum() function defined

in Example 7-5:

doublemaximum(intnrows,intncols,doublematrix[nrows][ncols]);doublemaximum(intnrows,intncols,doublematrix[][ncols]);doublemaximum(intnrows,intncols,doublematrix[*][*]);doublemaximum(intnrows,intncols,doublematrix[][*]);

How Functions Are Executed

The instruction to execute a function—the function call—consists of the function’s name and the operator () (see “Other Operators”). For example, the following statement calls the function maximum() to compute the maximum of the matrix mat, which has r rows and c columns:

maximum(r,c,mat);

The program first allocates storage space for the parameters, and then copies the argument values to the corresponding locations. Then the program jumps to the beginning of the function, and execution of the function begins with first variable definition or statement in the function block.

If the program reaches a return statement or the closing brace (}) of the function block, execution of the function ends and the program jumps back to the calling function. If the program “falls off the end” of the function by reaching the closing brace, the value returned to the caller is undefined. For this reason, you must use a return statement to stop any function that does not have the type void. The value of the return expression is returned to the calling function (see “The return Statement”).

Pointers as Arguments and Return Values

C is inherently a call by value language, as the parameters of a function are local variables initialized with the argument values. This type of language has the advantage that any expression desired can be used as an argument as long as it has the appropriate type. On the other hand, the drawback is that copying large data objects to begin a function call can be expensive. Moreover, a function has no way to modify the originals—that is, the caller’s variables—as it knows how to access only the local copy.

However, a function can directly access any variable visible to the caller if one of its arguments is that variable’s address. In this way, C also provides call by reference functions. A simple example is the standard function scanf(), which reads the standard input stream and places the results in variables referenced by pointer arguments that the caller provides:

intvar;scanf("%d",&var);

This function call reads a string as a decimal numeral, converts it to an integer, and stores the value in the location of var.

In the following example, the initNode() function initializes a structure variable. The caller passes the structure’s address as an argument.

#include <string.h>// Prototypes of memset() and strcpy()structNode{longkey;charname[32];/* ... more structure members ... */structNode*next;};voidinitNode(structNode*pNode)// Initialize the structure *pNode{memset(pNode,0,sizeof(*pNode));strcpy(pNode->name,"XXXXX");}

Even if a function needs only to read and not to modify a variable, it still may be more efficient to pass the variable’s address rather than its value. That’s because passing by address avoids the need to copy the data; only the variable’s address is pushed onto the stack. If the function does not modify such a variable, then you should declare the corresponding parameter as a read-only pointer, as in the following example:

voidprintNode(conststructNode*pNode);{printf("Key: %ld\n",pNode->key);printf("Name: %s\n",pNode->name);/* ... */}

You are also performing a “call by reference” whenever you call a function using an array name as an argument, because the array name is automatically converted into a pointer to the array’s first element. The addArray() function defined in Example 7-4 has two such pointer parameters.

Often functions need to return a pointer type as well, as the mkNode() function does in the following example. This function dynamically creates a new Node object and gives its address to the caller:

#include <stdlib.h>structNode*mkNode(){structNode*pNode=malloc(sizeof(structNode));if(pNode!=NULL)initNode(pNode);returnpNode;}

The mkNode() function returns a null pointer if it fails to allocate storage for a new Node object. Functions that return a pointer usually use a null pointer to indicate a failure condition. For example, a search function may return the address of the desired object, or a null pointer if no such object is available.

Inline Functions

Ordinarily, calling a function causes the computer to save its current instruction address, jump to the function called and execute it, and then make the return jump to the saved address. With small functions that you need to call often, this can degrade the program’s runtime behavior substantially. As a result, C99 has introduced the option of defining inline functions. The keyword inline is a request to the compiler to insert the function’s machine code wherever the function is called in the program. The result is that the function is executed as efficiently as if you had inserted the statements from the function body in place of the function call in the source code.

To define a function as an inline function, use the function specifier inline in its definition. In Example 7-7, swapf() is defined as an inline function that exchanges the values of two float variables, and the function selection_sortf() calls the inline function swapf().

Example 7-7. Function swapf()

// The function swapf() exchanges the values of two float variables.// Arguments: Two pointers to float.// Return value: None.inlinevoidswapf(float*p1,float*p2)// An inline function.{floattmp=*p1;*p1=*p2;*p2=tmp;}// The function selection_sortf() uses the selection-sort// algorithm to sort an array of float elements.// Arguments: An array of float, and its length.// Return value: None.voidselection_sortf(floata[],intn)// Sort an array a of length n.{registerinti,j,mini;// Three index variables.for(i=0;i<n-1;++i){mini=i;// Search for the minimum starting at index i.for(j=i+1;j<n;++j)if(a[j]<a[mini])mini=j;swapf(a+i,a+mini);// Swap the minimum with the element at index i.}}

It is generally not a good idea to define a function containing loops, such as selection_sortf(), as inline. Example 7-7 uses inline instead to speed up the instructions inside a for loop.

The inline specifier is not imperative: the compiler may ignore it. Recursive functions, for example, are usually not compiled inline. It is up to the given compiler to determine when a function defined with inline is actually inserted inline.

Unlike other functions, you must repeat the definitions of inline functions in each translation unit in which you use them. The compiler must have the function definition at hand in order to insert the inline code. For this reason, function definitions with inline are customarily written in header files.

If all the declarations of a function in a given translation unit have the inline specifier but not the extern specifier, then the function has an inline definition. An inline definition is specific to the translation unit; it does not constitute an external definition, and therefore another translation unit may contain an external definition of the function. If there is an external definition in addition to the inline definition, then the compiler is free to choose which of the two function definitions to use.

If you use the storage class specifier, extern, outside all other functions in a declaration of a function that has been defined with inline, then the function’s definition is external. For example, the following declaration, if placed in the same translation unit with the definition of swapf() in Example 7-7, would produce an external definition:

externvoidswapf(float*p1,float*p2);

Once the function swapf() has an external definition, other translation units only need to contain an ordinary declaration of the function in order to call it. However, calls to the function from other translation units will not be compiled inline.

Inline functions are ordinary functions except for the way they are called in machine code. Like ordinary functions, an inline function has a unique address. If macros are used in the statements of an inline function, the preprocessor expands them with their values as defined at the point where the function definition occurs in the source code. However, you should not define modifiable objects with static storage duration in an inline function that is not likewise declared as static.

Non-Returning Functions

Not all functions return control to their caller. Examples of functions that do not return include the standard functions abort(), exit(), _Exit(), quick_exit() and thread_exit(); these functions do not return because their purpose is to end the execution of a thread or of the whole program. Another example of a non-returning function is the standard function longjmp(), which does not end the program, but continues at the point defined by a prior call to the macro setjmp.

The function specifier _Noreturn is new in C11. It informs the compiler that the function in question does not return, so that the compiler can further optimize the code: on a call to a non-returning function, there is no need to push the return address or the contents of the CPU registers onto the stack. The compiler can also issue an “unreachable code” warning if there are other instructions in the same block after the non-returning function call.

The following example illustrates a user-defined function that does not return:

_NoreturnvoidmyAbort(){/* ... Instructions to clean up and save data ... */abort();}

It is important that you only declare a function with _Noreturn if it absolutely cannot return. If a function declared with _Noreturn does return, the program’s behavior is undefined, and the standard requires that the compiler issue a diagnostic message.

If your program includes the header file stdnoreturn.h, you can also use the synonym noreturn instead of the keyword _Noreturn.

Recursive Functions

A recursive function is one that calls itself, directly or indirectly. Indirect recursion means that a function calls another function (which may call a third function, and so on), which in turn calls the first function. Because a function cannot continue calling itself endlessly, recursive functions must always have an exit condition.

In Example 7-8, the recursive function binarySearch() implements the binary search algorithm to find a specified element in a sorted array. First, the function compares the search criterion with the middle element in the array. If they are the same, the function returns a pointer to the element found. If not, the function searches in whichever half of the array could contain the specified element by calling itself recursively. If the length of the array that remains to be searched reaches zero, then the specified element is not present, and the recursion is aborted.

Example 7-8. Function binarySearch()

// The binarySearch() function searches a sorted array.// Arguments: The value of the element to find;// the array of long to search; the array length.// Return value: A pointer to the element found,// or NULL if the element is not present in the array.long*binarySearch(longval,longarray[],intn){intm=n/2;if(n<=0)returnNULL;if(val==array[m])returnarray+m;if(val<array[m])returnbinarySearch(val,array,m);elsereturnbinarySearch(val,array+m+1,n-m-1);}

For an array of n elements, the binary search algorithm performs at most 1+log2(n) comparisons. With a million elements, the maximum number of comparisons performed is 20, which means at most 20 recursions of the binarySearch() function.

Recursive functions depend on the fact that a function’s automatic variables are created anew on each recursive call. These variables, and the caller’s address for the return jump, are stored on the stack with each recursion of the function that begins. It is up to the programmer to make sure that there is enough space available on the stack. The binarySearch() function as defined in Example 7-8 does not place excessive demands on the stack size, though.

Recursive functions are a logical way to implement algorithms that are recursive by nature, such as the binary search technique or navigation in tree structures. However, even when recursive functions offer an elegant and compact solution to a problem, simple solutions using loops are often possible as well. For example, you could rewrite the binary search in Example 7-8 with a loop statement instead of a recursive function call. In such cases, the iterative solution is generally faster in execution than the recursive function.

Variable Numbers of Arguments

C allows you to define functions that you can call with a variable number of arguments. These are sometimes called variadic functions. Such functions require a fixed number of mandatory arguments, followed by a variable number of optional arguments. Each such function must have at least one mandatory argument. The types of the optional arguments can also vary. The number of optional arguments is either determined by the values of the mandatory arguments or by a special value that terminates the list of optional arguments.

The best-known examples of variadic functions in C are the standard library functions printf() and scanf(). Each of these two functions has one mandatory argument: the format string. The conversion specifiers in the format string determine the number and the types of the optional arguments.

For each mandatory argument, the function head shows an appropriate parameter, as in ordinary function declarations. These are followed in the parameter list by a comma and an ellipsis (…), which stands for the optional arguments.

Internally, variadic functions access any optional arguments through an object with the type va_list, which contains the argument information. An object of this type—also called an argument pointer—contains at least the position of one argument on the stack. The argument pointer can be advanced from one optional argument to the next, allowing a function to work through the list of optional arguments. The type va_list is defined in the header file stdarg.h.

When you write a function with a variable number of arguments, you must define an argument pointer with the type va_list in order to read the optional arguments. In the following description, the va_list object is named argptr. You can manipulate the argument pointer using four macros, which are defined in the header file stdarg.h:

void va_start(va_list argptr,lastparam);-

The macro

va_startinitializes the argument pointerargptrwith the position of the first optional argument. The macro’s second argument must be the name of the function’s last named parameter. You must call this macro before your function can use the optional arguments. type va_arg(va_list argptr,type);-

The macro

va_argexpands to yield the optional argument currently referenced byargptr, and also advancesargptrto reference the next argument in the list. The second argument of the macrova_argis the type of the argument being read. void va_end(va_list argptr);-

When you have finished using an argument pointer, you should call the macro

va_end. If you want to use one of the macrosva_startorva_copyto reinitialize an argument pointer that you have already used, then you must callva_endfirst. void va_copy(va_list dest, va_list src);-

The macro

va_copyinitializes the argument pointerdestwith the current value ofsrc. You can then use the copy indestto access the list of optional arguments again, starting from the position referenced bysrc.

The function in Example 7-9 demonstrates the use of these macros.

Example 7-9. Function add()

// The add() function computes the sum of the optional arguments.// Arguments: The mandatory first argument indicates the number of// optional arguments. The optional arguments are// of type double.// Return value: The sum, with type double.doubleadd(intn,...){inti=0;doublesum=0.0;va_listargptr;va_start(argptr,n);// Initialize argptr; that is,for(i=0;i<n;++i)// for each optional argument,sum+=va_arg(argptr,double);// read an argument with type// double and accumulate in sum.va_end(argptr);returnsum;}