Chapter 9. Pointers

A pointer is a reference to a data object or a function. Pointers have many uses, such as defining “call-by-reference” functions and implementing dynamic data structures such as linked lists and trees, to name just two examples.

Very often the only efficient way to manage large volumes of data is to manipulate not the data itself but pointers to the data. For example, if you need to sort a large number of large records, it is often more efficient to sort a list of pointers to the records, rather than moving the records themselves around in memory. Similarly, if you need to pass a large record to a function, it’s more economical to pass a pointer to the record than to pass the record contents, even if the function doesn’t modify the contents.

Declaring Pointers

A pointer represents both the address and the type of an object or function. If an object or function has the type T, then a pointer to it has the derived type pointer to T. For example, if var is a float variable, then the expression &var—whose value is the address of the float variable—has the type pointer to float, or in C notation, the type float *. A pointer to any type T is also called a T pointer for short. Thus, the address operator in &var yields a float pointer.

Because var doesn’t move around in memory, the expression &var is a constant pointer. However, C also allows you to define variables with pointer types. A pointer variable stores the address of another object or a function. We describe pointers to arrays and functions a little further on. To start out, the declaration of a pointer to an object that is not an array has the following syntax:

type * [type-qualifier-list] name [= initializer];

In declarations, the asterisk (*) means “pointer to.” The identifier name is declared as an object with the type type *, or pointer to type. The optional type qualifier list may contain any combination of the type qualifiers const, volatile, and restrict. For details about qualified pointer types, see “Pointers and Type Qualifiers”.

Here is a simple example:

int*iPtr;// Declare iPtr as a pointer to int.

The type int is the type of object that the pointer iPtr can point to. To make a pointer refer to a certain object, assign it the address of the object. For example, if iVar is an int variable, then the following assignment makes iPtr point to the variable iVar:

iPtr=&iVar;// Let iPtr point to the variable iVar.

The general form of a declaration consists of a comma-separated list of declarators, each of which declares one identifier (see Chapter 11). In a pointer declaration, the asterisk (*) is part of an individual declarator. We can thus define and initialize the variables iVar and iPtr in one declaration, as follows:

intiVar=77,*iPtr=&iVar;// Define an int variable and// a pointer to it.

The second of these two declarations initializes the pointeriPtr with the address of the variable iVar, so that iPtr points to iVar.

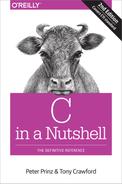

Figure 9-1 illustrates one possible arrangement of the variables iVar and iPtr in memory. The addresses shown are purely fictitious examples. As Figure 9-1 shows, the value stored in the pointer iPtr is the address of the object iVar.

Figure 9-1. A pointer and another object in memory

It is often useful to output addresses for verification and debugging purposes. The printf() functions provide a format specifier for pointers: %p. The following statement prints the address and value of the variable iPtr:

printf("Value of iPtr (i.e. the address of iVar): %p\n""Address of iPtr: %p\n",iPtr,&iPtr);

The size of a pointer in memory—given by the expression sizeof(iPtr), for example—is the same regardless of the type of object addressed. In other words, a char pointer takes up just as much space in memory as a pointer to a large structure. On 32-bit computers, pointers are usually four bytes long.

Null Pointers

A null pointer is what results when you convert a null pointer constant to a pointer type. A null pointer constant is an integer constant expression with the value of 0, or such an expression cast as the type void * (see “Null pointer constants”). The macro NULL is defined in stdlib.h, stdio.h, and other header files as a null pointer constant.

A null pointer is always unequal to any valid pointer to an object or function. For this reason, functions that return a pointer type usually use a null pointer to indicate a failure condition. One example is the standard function fopen(), which returns a null pointer if it fails to open a file in the specified mode:

#include <stdio.h>/* ... */FILE*fp=fopen("demo.txt","r");if(fp==NULL)// Also written as: if ( !fp ){// Error: unable to open the file demo.txt for reading.}

Null pointers are implicitly converted to other pointer types as necessary for assignment operations or for comparisons using == or !=. Hence, no cast operator is necessary in the previous example. (See also “Implicit Pointer Conversions”.)

void Pointers

A pointer to void, or void pointer for short, is a pointer with the type void *. As there are no objects with the type void, the type void * is used as the all-purpose pointer type. In other words, a void pointer can represent the address of any object—but not its type. To access an object in memory, you must always convert a void pointer into an appropriate object pointer.

To declare a function that can be called with different types of pointer arguments, you can declare the appropriate parameters as pointers to void. When you call such a function, the compiler implicitly converts an object pointer argument into a void pointer. A common example is the standard function memset(), which is declared in the header file string.h with the following prototype:

void*memset(void*s,intc,size_tn);

The memset() function assigns the value of c to each of the n bytes of memory in the block beginning at the address s. For example, the following function call assigns the value 0 to each byte in the structure variable record:

structData{/* ... */}record;memset(&record,0,sizeof(record));

The argument &record has the type struct Data *. In the function call, the argument is converted to the parameter’s type, void *.

The compiler likewise converts void pointers into object pointers where necessary. For example, in the following statement, the malloc() function returns a void pointer whose value is the address of the allocated memory block. The assignment operation converts the void pointer into a pointer to int:

int*iPtr=malloc(1000*sizeof(int));

For a more thorough illustration, see Example 2-3.

Initializing Pointers

Pointer variables with automatic storage duration start with an undefined value, unless their declaration contains an explicit initializer. All variables defined within any block have automatic storage duration unless they are defined with the storage class specifier static. All other pointers defined without an initializer have the initial value of a null pointer.

You can initialize a pointer with the following kinds of initializers:

-

A null pointer constant

-

A pointer to the same type, or to a less qualified version of the same type (see “Pointers and Type Qualifiers”)

-

A

voidpointer, if the pointer being initialized is not a function pointer (here again, the pointer being initialized can be a pointer to a more qualified type)

Pointers that do not have automatic storage duration must be initialized with a constant expression such as the result of an address operation or the name of an array or function.

When you initialize a pointer, no implicit type conversion takes place except in the cases just listed. However, you can explicitly convert a pointer value to another pointer type. For example, to read any object byte by byte, you can convert its address into a char pointer to the first byte of the object:

doublex=1.5;char*cPtr=&x;// Error: type mismatch; no implicit conversion.char*cPtr=(char*)&x;// OK: cPtr points to the first byte of x.

For more details and examples of pointer type conversions, see “Explicit Pointer Conversions”.

Operations with Pointers

This section describes the operations that can be performed using pointers. The most important of these operations is accessing the object or function that the pointer refers to. You can also compare pointers, and use them to iterate through a memory block. For a complete description of the individual operators in C with their precedence and permissible operands, see Chapter 5.

Using Pointers to Read and Modify Objects

The indirection operator * yields the location in memory whose address is stored in a pointer. If ptr is a pointer, then *ptr designates the object (or function) that ptr points to. Using the indirection operator is sometimes called dereferencing a pointer. The type of the pointer determines the type of object that is assumed to be at that location in memory. For example, when you access a given location using an int pointer, you read or write an object of type int.

Unlike the multiplication operator *, the indirection operator * is a unary operator; that is, it has only one operand. In Example 9-1, ptr points to the variable x. Hence, the expression *ptr is equivalent to the variable x itself.

Example 9-1. Dereferencing a pointer

doublex,y,*ptr;// Two double variables and a pointer to double.ptr=&x;// Let ptr point to x.*ptr=7.8;// Assign the value 7.8 to the variable x.*ptr*=2.5;// Multiply x by 2.5.y=*ptr+0.5;// Assign y the result of the addition x + 0.5.

Do not confuse the asterisk (*) in a pointer declaration with the indirection operator. The syntax of the declaration can be seen as an illustration of how to use the pointer. Here is an example:

double*ptr;

As declared here, ptr has the type double * (read: “pointer to double”). Hence the expression *ptr would have the type double.

Of course, the indirection operator * must be used only with a pointer that contains a valid address. This usage requires careful programming! Without the assignment ptr = &x in Example 9-1, all of the statements containing *ptr would be senseless—dereferencing an undefined pointer value—and might cause the program to crash.

A pointer variable is itself an object in memory, which means that a pointer can point to it. To declare a pointer to a pointer, you must use two asterisks, as in the following example:

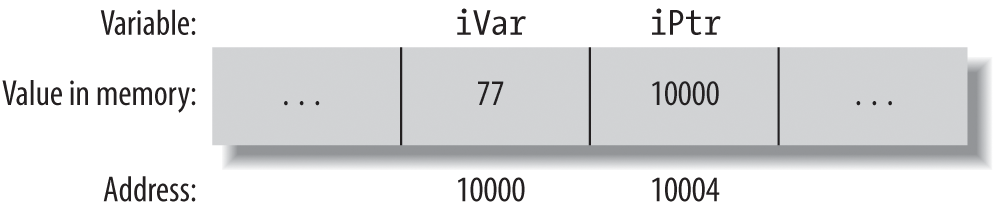

charc='A',*cPtr=&c,**cPtrPtr=&cPtr;

The expression *cPtrPtr now yields the char pointer cPtr, and the value of **cPtrPtr is the char variable c. Figure 9-2 illustrates these references.

Figure 9-2. A pointer to a pointer

Pointers to pointers are not restricted to the two-stage indirection illustrated here. You can define pointers with as many levels of indirection as you need. However, you cannot assign a pointer-to-a-pointer its value by mere repetitive application of the address operator:

charc='A',**cPtrPtr=&(&c);// Wrong!

The second initialization in this example is illegal: the expression (&c) cannot be the operand of &, because it is not an lvalue. In other words, there is no pointer to char in this example for cPtrPtr to point to.

If you pass a pointer to a function by reference so that the function can modify its value, then the function’s parameter is a pointer to a pointer. The following simple example is a function that dynamically creates a new record and stores its address in a pointer variable:

#include <stdlib.h>// The record type:typedefstruct{longkey;/* ... */}Record;_BoolnewRecord(Record**ppRecord){*ppRecord=malloc(sizeof(Record));if(*ppRecord!=NULL){/* ... Initialize the new record's members ... */return1;}elsereturn0;}

The following statement is one possible way to call the newRecord() function:

Record*pRecord=NULL;if(newRecord(&pRecord)){/* ... pRecord now points to a new Record object ... */}

The expression *pRecord yields the new record, and (*pRecord).key is the member key in that record. The parentheses in the expression (*pRecord).key are necessary because the dot operator (.) has higher precedence than the indirection operator (*).

Instead of this combination of operators and parentheses, you can also use the arrow operator -> to access structure or union members. If p is a pointer to a structure or union with a member m, then the expression p->m is equivalent to (*p).m. Thus, the following statement assigns a value to the member key in the structure that pRecord points to:

pRecord->key=123456L;

Modifying and Comparing Pointers

Besides using assignments to make a pointer refer to a given object or function, you can also modify an object pointer using arithmetic operations. When you perform pointer arithmetic, the compiler automatically adapts the operation to the size of the objects referred to by the pointer type.

You can perform the following operations on pointers to objects:

-

Adding an integer to, or subtracting an integer from, a pointer.

-

Subtracting one pointer from another.

-

Comparing two pointers.

When you subtract one pointer from another, the two pointers must have the same basic type, although you can disregard any type qualifiers. Furthermore, you may compare any pointer with a null pointer constant using the equality operators (== and !=), and you may compare any object pointer with a pointer to void.

The three pointer operations described here are generally useful only for pointers that refer to the elements of an array. To illustrate the effects of these operations, consider two pointers p1 and p2, which point to elements of an array a:

-

If

p1points to the array elementa[i], andnis an integer, then the expressionp2 = p1 + nmakesp2point to the array elementa[i+n](assuming thati+nis an index within the arraya). -

The subtraction

p2 − p1yields the number of array elements between the two pointers, with the typeptrdiff_t. The typeptrdiff_tis defined in the stddef.h header file, usually asint. After the assignmentp2 = p1 + n, the expressionp2 − p1yields the value ofn. -

The comparison

p1 < p2yieldstrueif the element referenced byp2has a greater index than the element referenced byp1. Otherwise, the comparison yieldsfalse.

Because the name of an array is implicitly converted into a pointer to the first array element wherever necessary, you can also substitute pointer arithmetic for array subscript notation:

-

The expression

a + iis a pointer toa[i], and the value of*(a+i)is the elementa[i]. -

The expression

p1 − ayields the indexiof the element referenced byp1.

In Example 9-2, the selection_sortf() function sorts an array of float elements using the selection-sort algorithm. This is the pointer version of the selection_sortf() function in Example 7-7; in other words, this function does the same job but uses pointers instead of indices. The helper function swapf() remains unchanged.

Example 9-2. Pointer version of the selection_sortf() function

// The swapf() function exchanges the values of two float variables.// Arguments: Two pointers to float.inlinevoidswapf(float*p1,float*p2){floattmp=*p1;*p1=*p2;*p2=tmp;// Swap *p1 and *p2.}// The function selection_sortf() uses the selection-sort// algorithm to sort an array of float elements.// Arguments: An array of float, and its length.voidselection_sortf(floata[],intn)// Sort an array a of// n float elements.{if(n<=1)return;// Nothing to sort.registerfloat*last=a+n-1,// A pointer to the last element.*p,// A pointer to a selected element.*minPtr;// A pointer to the current minimum.for(;a<last;++a)// Walk pointer a through the array.{minPtr=a;// Find the smallest elementfor(p=a+1;p<=last;++p)// between a and the last element.if(*p<*minPtr)minPtr=p;swapf(a,minPtr);// Swap the smallest element}// with the element at a.}

The pointer version of such a function is generally more efficient than the index version because accessing the elements of the array a using an index i, as in the expression a[i] or *(a+i), involves adding the address a to the value i*sizeof(element_type) to obtain the address of the corresponding array element. The pointer version requires less arithmetic because the pointer is incremented instead of the index, and points to the required array element

directly.

Pointers and Type Qualifiers

The declaration of a pointer may contain the type qualifiers const, volatile, and/or restrict. The const and volatile type qualifiers may qualify either the pointer type itself, or the type of object it points to. The difference is important. Those type qualifiers that occur in the pointer’s declarator—that is, between the asterisk and the pointer’s name—qualify the pointer itself. Here is an example:

shortconstvolatile*restrictptr;

In this declaration, the keyword restrict qualifies the pointer ptr. This pointer can refer to objects of type short that may be qualified with const or volatile, or both.

An object whose type is qualified with const is constant: the program cannot modify it after its definition. The type qualifier volatile is a hint to the compiler that the object so qualified may be modified not only by the present program, but also by other processes or events (see Chapter 11).

Tip

The most common use of qualifiers in pointer declarations is in pointers to constant objects, especially as function parameters. For this reason, the following description refers to the type qualifier const. The same rules govern the use of the volatile type qualifier with pointers.

Constant Pointers and Pointers to Constant Objects

When you define a constant pointer, you must also initialize it because you can’t modify it later. As the following example illustrates, a constant pointer is not the same thing as a pointer to a constant object:

intvar;// An object with type int.int*constc_ptr=&var;// A constant pointer to int.*c_ptr=123;// OK: we can modify the object referenced.++c_ptr;// Error: we can't modify the pointer.

You can modify a pointer that points to an object that has a const-qualified type (also called a pointer to const). However, you can only use such a pointer to read the referenced object, not to modify it. For this reason, pointers to const are commonly called read-only pointers. The referenced object itself may or may not be constant. Here is an example:

intvar;// An object with type int.constintc_var=100,// A constant int object.*ptr_to_const;// A pointer to const int: the pointer// itself is not constant!ptr_to_const=&c_var;// OK: Let ptr_to_const point to c_var.var=2**ptr_to_const;// OK. Equivalent to: var = 2 * c_var;ptr_to_const=&var;// OK: Let ptr_to_const point to var.if(c_var<*ptr_to_const)// OK: "read-only" access.*ptr_to_const=77;// Error: we can't modify var using// ptr_to_const, even though var is// not constant.

Type specifiers and type qualifiers can be written in any order. Thus, the following is permissible:

intconstc_var=100,*ptr_to_const;

The assignment ptr_to_const = &var entails an implicit conversion: the int pointer value &var is automatically converted to the left operand’s type, pointer to const int. For any operator that requires operands with like types, the compiler implicitly converts a pointer to a given type T into a more qualified version of the type T. If you want to convert a pointer into a pointer to a less-qualified type, you must use an explicit type conversion. The following code fragment uses the variables declared in the previous example:

int*ptr=&var;// An int pointer that points to var.*ptr=77;// OK: ptr is not a read-only pointer.ptr_to_const=ptr;// OK: implicitly converts ptr from "pointer to// int" into "pointer to const int".*ptr_to_const=77;// Error: can't modify a variable through a// read-only pointer.ptr=&c_var;// Error: can't implicitly convert "pointer to// const int" into "pointer to int".ptr=(int*)&c_var;// OK: Explicit pointer conversions are always// possible.*ptr=200;// Attempt to modify c_var: possible runtime// error.

The final statement causes a runtime error if the compiler has placed the constant object c_var in a read-only section in memory.

You can also declare a constant pointer to const, as the parameter declaration in the following function prototype illustrates:

voidfunc(constint*constc_ptr_to_const);

The function’s parameter is a read-only pointer that is initialized when the function is called and remains constant within the function.

Restricted Pointers

C99 introduced the type qualifier restrict, which is applicable only to object pointers. A pointer qualified with restrict is called a restricted pointer. There is a special relationship between a restrict-qualified pointer and the object it points to: during the lifetime of the pointer, either the object is not modified or the object is not accessed except through the restrict-qualified pointer. Here is an example:

typedefstruct{longkey;// Define a structure type./* ... other members ... */}Data_t;Data_t*restrictrPtr=malloc(sizeof(Data_t));// Allocate a// structure.

This example illustrates one way to respect the relationship between the restricted pointer and its object: the return value of malloc()—the address of an anonymous Data_t object—is assigned only to the pointer rPtr, so the program won’t access the object in any other way.

It is up to you, the programmer, to make sure that an object referenced by a restrict-qualified pointer is accessed only through that pointer. For example, if your program modifies an object through a restricted pointer, it must not access the object by name or through another pointer for as long as the restricted pointer exists.

The restrict type qualifier is a hint to the compiler that allows it to apply certain optimization techniques that might otherwise introduce inconsistencies. However, the restrict qualifier does not mandate any such optimization, and the compiler may ignore it. The program’s outward behavior is the same in either case.

The restrict type qualifier is used in the prototypes of many standard library functions. For example, the memcpy() function is declared in the string.h header file as follows:

void*memcpy(void*restrictdest,// Destinationconstvoid*restrictsrc,// Sourcesize_tn);// Number of bytes to copy

This function copies a memory block of n bytes, beginning at the address src, to the location beginning at dest. Because the pointer parameters are both restricted, you must make sure that the function will not use them to access the same objects; in other words, make sure that the source and destination blocks do not overlap. The following example contains one correct and one incorrect memcpy() call:

chara[200];/* ... */memcpy(a+100,a,100);// OK: copy the first half of the array// to the second half; no overlap.memcpy(a+1,a,199);// Error: move the whole array contents// upward by one index; large overlap.

The second memcpy() call in this example violates the restrict condition, because the function must modify 198 locations that it accesses using both pointers.

The standard function memmove(), unlike memcpy(), allows the source and destination blocks to overlap. Accordingly, neither of its pointer parameters has the restrict qualifier:

void*memmove(void*dest,constvoid*src,size_tn);

Example 9-3 illustrates the second way to fulfill the restrict condition: the program may access the object pointed to using other names or pointers if it doesn’t modify the object for as long as the restricted pointer exists. This simple function calculates the scalar product of two arrays.

Example 9-3. The function scalar_product()

// This function calculates the scalar product of two arrays.// Arguments: Two arrays of double, and their length.// The two arrays need not be distinct.doublescalar_product(constdouble*restrictp1,constdouble*restrictp2,intn){doubleresult=0.0;for(inti=0;i<n;++i)result+=p1[i]*p2[i];returnresult;}

Assuming an array named P with three double elements, you could call this function using the expression scalar_products( P, P, 3 ). The function accesses objects through two different restricted pointers, but as the const keyword in the first two parameter declarations indicates, it doesn’t modify them.

Pointers to Arrays and Arrays of Pointers

Pointers occur in many C programs as references to arrays, and also as elements of arrays. A pointer to an array type is called an array pointer for short, and an array whose elements are pointers is called a pointer array.

Array Pointers

For the sake of example, the following description deals with an array of int. The same principles apply for any other array type, including multidimensional arrays.

To declare a pointer to an array type, you must use parentheses, as the following example illustrates:

int(*arrPtr)[10]=NULL;// A pointer to an array of// ten elements with type int.

Without the parentheses, the declaration int * arrPtr[10]; would define arrPtr as an array of 10 pointers to int. Arrays of pointers are described in the next section.

In the example, the pointer to an array of 10 int elements is initialized with NULL. However, if we assign it the address of an appropriate array, then the expression *arrPtr yields the array, and (*arrPtr)[i] yields the array element with the index i. According to the rules for the subscript operator, the expression (*arrPtr)[i] is equivalent to *((*arrPtr)+1) (see “Memory Addressing Operators”). Hence, **arrPtr yields the first element of the array, with the index 0.

In order to demonstrate a few operations with the array pointer arrPtr, the following example uses it to address some elements of a two-dimensional array—that is, some rows of a matrix (see “Matrices”):

intmatrix[3][10];// Array of three rows, each with 10 columns.// The array name is a pointer to the first// element; i.e., the first row.arrPtr=matrix;// Let arrPtr point to the first row of// the matrix.(*arrPtr)[0]=5;// Assign the value 5 to the first element of// the first row.//arrPtr[2][9]=6;// Assign the value 6 to the last element of// the last row.//++arrPtr;// Advance the pointer to the next row.(*arrPtr)[0]=7;// Assign the value 7 to the first element// of the second row.

After the initial assignment, arrPtr points to the first row of the matrix, just as the array name matrix does. At this point, you can use arrPtr in the same way as matrix to access the elements. For example, the assignment (*arrPtr)[0] = 5 is equivalent to arrPtr[0][0] = 5 or matrix[0][0] = 5.

However, unlike the array name matrix, the pointer name arrPtr does not represent a constant address, as the operation ++arrPtr shows. The increment operation increases the address stored in an array pointer by the size of one array—in this case, one row of the matrix, or ten times the number of bytes in an int element.

If you want to pass a multidimensional array to a function, you must declare the corresponding function parameter as a pointer to an array type. For a full description and an example of this use of pointers, see “Arrays as Arguments of Functions”.

One more word of caution: if a is an array of ten int elements, then you cannot make the pointer from the previous example, arrPtr, point to the array a by this assignment:

arrPtr=a;// Error: mismatched pointer types.

The reason is that an array name, such as a, is implicitly converted into a pointer to the array’s first element, not a pointer to the whole array. The pointer to int is not implicitly converted into a pointer to an array of int. The assignment in the example requires an explicit type conversion, specifying the target type int (*)[10] in the cast operator:

arrPtr=(int(*)[10])a;// OK

You can derive this notation for the array pointer type from the declaration of arrPtr by removing the identifier (see “Type Names”). However, for more readable and more flexible code, it is a good idea to define a simpler name for the type using typedef:

typedefintARRAY_t[10];// A type name for// "array of ten int elements".ARRAY_ta,// An array of this type,*arrPtr;// and a pointer to this array type.arrPtr=(ARRAY_t*)a;// Let arrPtr point to a.

Pointer Arrays

Pointer arrays—that is, arrays whose elements have a pointer type—are often a handy alternative to two-dimensional arrays. Usually the pointers in such an array point to dynamically allocated memory blocks.

For example, if you need to process strings, you could store them in a two-dimensional array whose row size is large enough to hold the longest string that can occur:

#define ARRAY_LEN 100#define STRLEN_MAX 256charmyStrings[ARRAY_LEN][STRLEN_MAX]={// Several corollaries of Murphy's law:"If anything can go wrong, it will.","Nothing is foolproof, because fools are so ingenious.","Every solution breeds new problems."};

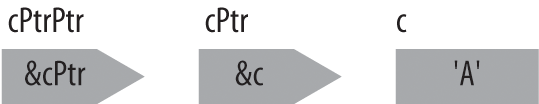

However, this technique wastes memory, as only a small fraction of the 25,600 bytes devoted to the array is actually used. For one thing, a short string leaves most of a row empty; for another, memory is reserved for whole rows that may never be used. A simple solution in such cases is to use an array of pointers that reference the objects—in this case, the strings—and to allocate memory only for the pointer array and for objects that actually exist (unused array elements are null pointers):

#define ARRAY_LEN 100char*myStrPtr[ARRAY_LEN]=// Array of pointers to char{// Several corollaries of Murphy's law:"If anything can go wrong, it will.","Nothing is foolproof, because fools are so ingenious.","Every solution breeds new problems."};

The diagram in Figure 9-3 illustrates how the objects are stored in memory.

Figure 9-3. Pointer array

The pointers not yet used can be made to point to other strings at runtime. The necessary storage can be reserved dynamically in the usual way. The memory can also be released when it is no longer needed.

The program in Example 9-4 is a simple version of the filter utility sort. It reads text from the standard input stream, sorts the lines alphanumerically, and prints them to standard output. This routine does not move any strings; it merely sorts an array of pointers.

Example 9-4. A simple program to sort lines of text

#include <stdio.h>#include <stdlib.h>#include <string.h>char*getLine(void);// Reads a line of textintstr_compare(constvoid*,constvoid*);#define NLINES_MAX 1000// Maximum number of text lines.char*linePtr[NLINES_MAX];// Array of pointers to char.intmain(){// Read lines:intn=0;// Number of lines read.for(;n<NLINES_MAX&&(linePtr[n]=getLine())!=NULL;++n);if(!feof(stdin))// Handle errors.{if(n==NLINES_MAX)fputs("sorttext: too many lines.\n",stderr);elsefputs("sorttext: error reading from stdin.\n",stderr);}else// Sort and print.{qsort(linePtr,n,sizeof(char*),str_compare);// Sort.for(char**p=linePtr;p<linePtr+n;++p)// Print.puts(*p);}return0;}// Reads a line of text from stdin; drops the terminating// newline character.// Return value: A pointer to the string read, or// NULL at end-of-file, or if an error occurred.#define LEN_MAX 512// Maximum length of a line.char*getLine(){charbuffer[LEN_MAX],*linePtr=NULL;if(fgets(buffer,LEN_MAX,stdin)!=NULL){size_tlen=strlen(buffer);if(buffer[len-1]=='\n')// Trim the newline character.buffer[len-1]='\0';else++len;if((linePtr=malloc(len))!=NULL)// Get memory for the line.strcpy(linePtr,buffer);// Copy the line to the allocated block.}returnlinePtr;}// Comparison function for use by qsort().// Arguments: Pointers to two elements in the array being sorted:// here, two pointers to pointers to char (char **).intstr_compare(constvoid*p1,constvoid*p2){returnstrcmp(*(char**)p1,*(char**)p2);}

The maximum number of lines that the program in Example 9-4 can sort is limited by the constant NLINES_MAX. However, we could remove this limitation by creating the array of pointers to text lines dynamically as well.

Pointers to Functions

There are a variety of uses for function pointers in C. For example, when you call a function, you might want to pass it not only the data for it to process but also pointers to subroutines that determine how it processes the data. We have just seen an example of this use: the standard function qsort(), used in Example 9-4, takes a pointer to a comparison function as one of its arguments in addition to the information about the array to be sorted. qsort() uses the pointer to call the specified function whenever it has to compare two array elements.

You can also store function pointers in arrays, and then call the functions using array index notation. For example, a keyboard driver might use a table of function pointers whose indices correspond to the key numbers. When the user presses a key, the program would jump to the corresponding function.

Like declarations of pointers to array types, function pointer declarations require parentheses. The examples that follow illustrate how to declare and use pointers to functions. This declaration defines a pointer to a function type with two parameters of type double and a return value of type double:

double(*funcPtr)(double,double);

The parentheses that enclose the asterisk and the identifier are important. Without them, the declaration double *funcPtr(double, double); would be the prototype of a function, not the definition of a pointer.

Wherever necessary, the name of a function is implicitly converted into a pointer to the function. Thus, the following statements assign the address of the standard function pow() to the pointer funcPtr, and then call the function using that pointer:

doubleresult;funcPtr=pow;// Let funcPtr point to the function pow().// The expression *funcPtr now yields the// function pow().result=(*funcPtr)(1.5,2.0);// Call the function referenced by// funcPtr.result=funcPtr(1.5,2.0);// The same function call.

As the last line in this example shows, when you call a function using a pointer, you can omit the indirection operator because the left operand of the function call operator (i.e., the parentheses enclosing the argument list) has the type “pointer to function” (see “Function calls”).

The simple program in Example 9-5 prompts the user to enter two numbers, and then performs some simple calculations with them. The mathematical functions are called by pointers that are stored in the array funcTable.

Example 9-5. Simple use of function pointers

#include <stdio.h>#include <stdlib.h>#include <math.h>doubleAdd(doublex,doubley){returnx+y;}doubleSub(doublex,doubley){returnx−y;}doubleMul(doublex,doubley){returnx*y;}doubleDiv(doublex,doubley){returnx/y;}// Array of 5 pointers to functions that take two double parameters// and return a double:double(*funcTable[5])(double,double)={Add,Sub,Mul,Div,pow};// Initializer list.// An array of pointers to strings for output:char*msgTable[5]={"Sum","Difference","Product","Quotient","Power"};intmain(){inti;// An index variable.doublex=0,y=0;printf("Enter two operands for some arithmetic:\n");if(scanf("%lf %lf",&x,&y)!=2)printf("Invalid input.\n");for(i=0;i<5;++i)printf("%10s: %6.2f\n",msgTable[i],funcTable[i](x,y));return0;}

The expression funcTable[i](x,y) calls the function whose address is stored in the pointer funcTable[i]. The array name and subscript do not need to be enclosed in parentheses because the function call operator () and the subscript operator [] both have the highest precedence and left-to-right associativity (see Table 5-4).

Once again, complex types such as arrays of function pointers are easier to manage if you define simpler type names using typedef. For example, you could define the array funcTable as follows:

typedefdoublefunc_t(double,double);// The functions' type is// now named func_t.func_t*funcTable[5]={Add,Sub,Mul,Div,pow};

This approach is certainly more readable than the array definition in Example 9-5.