Chapter 8. Arrays

An array contains objects of a given type, stored consecutively in a continuous memory block. The individual objects are called the elements of an array. The elements’ type can be any object type. No other types are permissible: array elements may not have a function type or an incomplete type (see “Typology”).

An array is also an object itself, and its type is derived from its elements’ type. More specifically, an array’s type is determined by the type and number of elements in the array. If an array’s elements have type T, then the array is called an “array of T.” If the elements have type int, for example, then the array’s type is “array of int.” The type is an incomplete type, however, unless it also specifies the number of elements. If an array of int has 16 elements, then it has a complete object type, which is “array of 16 int elements.”

Defining Arrays

The definition of an array determines its name, the type of its elements, and the number of elements in the array. An array definition without any explicit initialization has the following syntax:

type name[ number_of_elements ];

The number of elements, between square brackets ([]), must be an integer expression whose value is greater than zero. Here is an example:

charbuffer[4*512];

This line defines an array with the name buffer, which consists of 2,048 elements of type char.

You can determine the size of the memory block that an array occupies using the sizeof operator. The array’s size in memory is always equal to the size of one element times the number of elements in the array. Thus, for the array buffer in our example, the expression sizeof(buffer) yields the value of 2048 * sizeof(char); in other words, the array buffer occupies 2,048 bytes of memory because sizeof(char) always equals one.

In an array definition, you can specify the number of elements as a constant expression or, under certain conditions, as an expression involving variables. The resulting array is accordingly called a fixed-length or a variable-length array.

Fixed-Length Arrays

Most array definitions specify the number of array elements as a constant expression. An array so defined has a fixed length. Thus, the array buffer defined in the previous example is a fixed-length array.

Fixed-length

arrays can have any storage class: you can define them outside all functions or within a block, and with or without the storage class specifier static. The only restriction is that no function parameter can be an array. An array argument passed to a function is always converted into a pointer to the first array element (see “Arrays as Function Parameters”).

The four array definitions in the following example are all valid:

inta[10];// a has external linkage.staticintb[10];// b has static storage duration and file scope.voidfunc(){staticintc[10];// c has static storage duration and block scope.intd[10];// d has automatic storage duration./* ... */}

Variable-Length Arrays

C99 also allows you to define an array using a nonconstant expression for the number of elements if the array has automatic storage duration—in other words, if the definition occurs within a block and does not have the specifier static. Such an array is then called a variable-length array.

Furthermore, the name of a variable-length array must be an ordinary identifier (see “Identifier Name Spaces”). Members of structures or unions cannot be variable-length arrays. In the following examples, only the definition of the array vla is a permissible definition:

voidfunc(intn){intvla[2*n];// OK: storage duration is automatic.staticinte[n];// Illegal: a variable length array cannot// have static storage duration.structS{intf[n];};// Illegal: f is not an ordinary identifier./* ... */}

Like any other automatic variable, a variable-length array is created anew each time the program flow enters the block containing its definition. As a result, the array can have a different length at each such instantiation. Once created, however, even a variable-length array cannot change its length during its storage duration.

Storage for automatic objects is allocated on the stack, and is released when the program flow leaves the block. For this reason, variable-length array definitions are useful only for small, temporary arrays. To create larger arrays dynamically, you should generally allocate storage space explicitly using the standard functions, malloc() and calloc(). The storage duration of such arrays then ends with the end of the program or when you release the allocated memory by calling the function free() (see Chapter 12).

Accessing Array Elements

The subscript operator, [], provides an easy way to address the individual elements of an array by index. If myArray is the name of an array and i is an integer, then the expression myArray[i] designates the array element with the index i. Array elements are indexed beginning with 0. Thus, if len is the number of elements in an array, the last element of the array has the index len-1 (see “Memory Addressing Operators”).

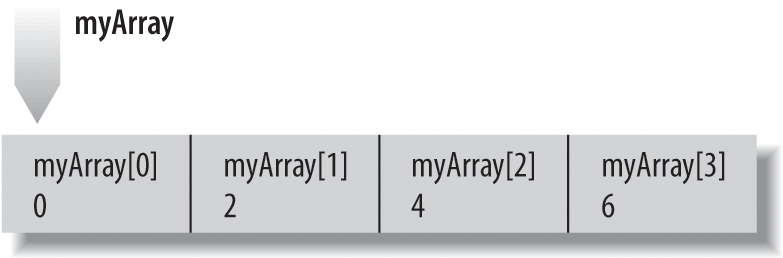

The following code fragment defines the array myArray and assigns a value to each element.

#define A_SIZE 4longmyArray[A_SIZE];for(inti=0;i<A_SIZE;++i)myArray[i]=2*i;

The diagram in Figure 8-1 illustrates the result of this assignment loop.

Figure 8-1. Values assigned to elements by index

An array index can be any integer expression desired. The subscript operator, [], does not bring any range checking with it; C gives priority to execution speed in this regard. It is up to you, the programmer, to ensure that an index does not exceed the range of permissible values. The following incorrect example assigns a value to a memory location outside the array:

longmyArray[4];myArray[4]=8;// Error: subscript must not exceed 3.

Such “off-by-one” errors can easily cause a program to crash (or, worse still, can cause silent data corruption), and are not always as easy to recognize as they are in this simple example.

Another way to address array elements, as an alternative to the subscript operator, is to use pointer arithmetic. After all, the name of an array is implicitly converted into a pointer to the first array element in all expressions except sizeof operations. For example, the expression myArray+i yields a pointer to the element with the index i, and the expression *(myArray+i) is equivalent to myArray[i] (see “Pointer arithmetic”).

The following loop statement uses a pointer instead of an index to step through the array myArray, and doubles the value of each element:

for(long*p=myArray;p<myArray+A_SIZE;++p)*p*=2;

Initializing Arrays

If you do not explicitly initialize an array variable, the usual rules apply: if the array has automatic storage duration, then its elements have undefined values. Otherwise, all elements are initialized by default to the value 0. (If the elements are pointers, they are initialized to NULL.) For more details, see “Initialization”.

Writing Initialization Lists

To initialize an array explicitly when you define it, you must use an initialization list: this is a comma-separated list of initializers, or initial values for the individual array elements, enclosed in braces. Here is an example:

inta[4]={1,2,4,8};

This definition gives the elements of the array a the following initial values:

a[0] = 1, a[1] = 2, a[2] = 4, a[3] = 8

When you initialize an array, observe the following rules:

-

You cannot include an initialization in the definition of a variable-length array.

-

If the array has static storage duration, then the array initializers must be constant expressions. If the array has automatic storage duration, then you can use variables in its initializers.

-

You may omit the length of the array in its definition if you supply an initialization list. The array’s length is then determined by the index of the last array element for which the list contains an initializer. For example, the definition of the array

ain the previous example is equivalent to this:inta[]={1,2,4,8};// An array with four elements. -

If the definition of an array contains both a length specification and an initialization list, then the length is that specified by the expression between the square brackets. Any elements for which there is no initializer in the list are initialized to zero (or

NULL, for pointers). If the list contains more initializers than the array has elements, the superfluous initializers are simply ignored. -

A superfluous comma after the last initializer is also ignored.

As a result of these rules, all of the following definitions are equivalent:

inta[4]={1,2};inta[]={1,2,0,0};inta[]={1,2,0,0,};inta[4]={1,2,0,0,5};

In the final definition, the initializer 5 is ignored. Most compilers generate a warning when such a mismatch occurs.

Array initializers must have the same type as the array elements. If the array elements’ type is a union, structure, or array type, then each initializer is generally another initialization list. Here is an example:

typedefstruct{unsignedlongpin;charname[64];/* ... */}Person;Personteam[6]={{1000,"Mary"},{2000,"Harry"}};

The other four elements of the array team are initialized to 0, or in this case, to { 0, "" }.

You can also initialize arrays of char, wchar_t, char16_t or char32_t with string literals (see “Strings”).

Initializing Specific Elements

C99 has introduced element designators to allow you to associate initializers with specific elements. To specify a certain element to initialize, place its index in square brackets. In other words, the general form of an element designator for array elements is:

[constant_expression]

The index must be an integer constant expression. In the following example, the element designator is [A_SIZE/2]:

#define A_SIZE 20inta[A_SIZE]={1,2,[A_SIZE/2]=1,2};

This array definition initializes the elements a[0] and a[10] with the value 1, and the elements a[1] and a[11] with the value 2. All other elements of the array will be given the initial value 0. As this example illustrates, initializers without an element designator are associated with the element following the last one initialized.

If you define an array without specifying its length, the index in an element designator can have any non-negative integer value. As a result, the following definition creates an array of 1,001 elements:

inta[]={[1000]=-1};

All of the array’s elements have the initial value of 0 except the last element, which is initialized to the value -1.

Strings

A string is a continuous sequence of characters terminated by '\0', the null character. The length of a string is considered to be the number of characters excluding the terminating null character. There is no string type in C, and consequently there are no operators that accept strings as operands.

Instead, strings are stored in arrays whose elements have the type char or a wide-character type—that is, one of the types wchar_t, char16_t, or char32_t. Strings of wide characters are also called wide strings. The C standard library provides numerous functions to perform basic operations on strings such as comparing, copying, and concatenating them. In addition to the traditional string functions, C11 has also introduced “secure” versions, which ensure that string operations do not exceed the bounds of an array (see “String Processing”).

You can initialize arrays of any character type using string literals. For example, the following two array definitions are equivalent:

charstr1[30]="Let's go";// String length: 8; array length: 30.charstr1[30]={'L','e','t','\'','s',' ','g','o','\0'};

An array holding a string must always be at least one element longer than the string length to accommodate the terminating null character. The array str1 can store strings up to a maximum length of 29. It would be a mistake to define the array with a length of 8 rather than 30 because then it wouldn’t contain the terminating null character.

If you define a character array without an explicit length and initialize it with a string literal, the array created is one element longer than the string length. Here is an example:

charstr2[]=" to London!";// String length: 11 (note leading space);// array length: 12.

The following statement uses the standard function strcat() to append the string in str2 to the string in str1 (the array str1 must be large enough to hold all the characters in the concatenated string):

#include <string.h>charstr1[30]="Let's go";charstr2[]=" to London!";/* ... */strcat(str1,str2);puts(str1);

The output printed by the puts() call is the new content of the array str1:

Let's go to London!

The names str1 and str2 are pointers to the first character of the string stored in each array. Such a pointer is called a pointer to a string, or a string pointer for short. String manipulation functions such as strcat() and puts() receive the beginning addresses of strings as their arguments. Such functions generally process a string character by character until they reach the terminator, '\0'. The function in Example 8-1 is one possible implementation of the standard function strcat(). It uses pointers to step through the strings referenced by its arguments.

Example 8-1. Function strcat()

// The function strcat() appends a copy of the second string// to the end of the first string.// Arguments: Pointers to the two strings.// Return value: A pointer to the first string, now// concatenated with the second string.char*strcat(char*restricts1,constchar*restricts2){char*rtnPtr=s1;while(*s1!='\0')// Find the end of string s1.++s1;while((*s1++=*s2++)!='\0')// The first character from s2;// replaces the terminator of s1.returnrtnPtr;}

The char array beginning at the address s1 must be at least as long as the sum of the two strings’ lengths, plus one for the terminating null character. To test for this condition before calling strcat(), you might use the standard function strlen(), which returns the length of the string referenced by its argument:

if(sizeof(str1)>=(strlen(str1)+strlen(str2)+1))strcat(str1,str2);

A wide-string literal is identified by one of the prefixes L, u, or U (see “String Literals”). Accordingly, the initialization of a wchar_t array looks like this:

#include <stddef.h>// Definition of the type wchar_t/* ... */wchar_tdinner[]=L"chop suey";// String length: 10;// array length: 11;// array size: 11 * sizeof(wchar_t)

Multidimensional Arrays

A multidimensional array in C is merely an array whose elements are themselves arrays. The elements of an n-dimensional array are (n-1)-dimensional arrays. For example, each element of a two-dimensional array is a one-dimensional array. The elements of a one-dimensional array, of course, do not have an array type.

A multidimensional array declaration has a pair of brackets for each dimension:

charscreen[10][40][80];// A three-dimensional array

The array screen consists of the 10 elements screen[0] to screen[9]. Each of these elements is a two-dimensional array consisting in turn of 40 one-dimensional arrays of 80 characters each. All in all, the array screen contains 32,000 elements of the type char.

To access a char element in the three-dimensional array screen, you must specify three indices. For example, the following statement writes the character Z in the last char element of the array:

screen[9][39][79]='Z';

Matrices

Two-dimensional arrays are also called matrices. Because they are so frequently used, they merit a closer look. It is often helpful to think of the elements of a matrix as being arranged in rows and columns. Thus, the matrix mat in the following definition has three rows and five columns:

floatmat[3][5];

The three elements mat[0], mat[1], and mat[2] are the rows of the matrix mat. Each of these rows is an array of five float elements. Thus, the matrix contains a total of 3 × 5 = 15 float elements, as the following table illustrates:

[0] |

[1] |

[2] |

[3] |

[4] |

|

mat[0] |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

mat[1] |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

mat[2] |

2.0 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

The values specified in the diagram can be assigned to the individual elements by a nested loop statement. The first index specifies a row, and the second index addresses a column in the row:

for(introw=0;row<3;++row)for(intcol=0;col<5;++col)mat[row][col]=row+(float)col/10;

In memory, the three rows are stored consecutively, as they are the elements of the array mat. As a result, the float values in this matrix are all arranged consecutively in memory in ascending order.

Declaring Multidimensional Arrays

In an array declaration that is not a definition, the array type can be incomplete; you can declare an array without specifying its length. Such a declaration is a reference to an array that you must define with a specified length elsewhere in the program. However, you must always declare the complete type of an array’s elements. For a multidimensional array declaration, only the first dimension can have an unspecified length. All other dimensions must have a magnitude. In declaring a two-dimensional matrix, for example, you must always specify the number of columns.

If the array mat in the previous example has external linkage, for example—that is, if its definition is placed outside all functions—then it can be used in another source file after the following declaration:

externfloatmat[][5];// External declaration

The external object so declared has an incomplete two-dimensional array type.

Initializing Multidimensional Arrays

You can initialize multidimensional arrays using an initialization list according to the rules described in “Initializing Arrays”. There are some peculiarities, however: you do not have to show all the braces for each dimension, and you may use multidimensional element designators.

To illustrate the possibilities, we will consider the array defined and initialized as follows:

inta3d[2][2][3]={{{1,0,0},{4,0,0}},{{7,8,0},{0,0,0}}};

This initialization list includes three levels of list-enclosing braces, and initializes the elements of the two-dimensional arrays a3d[0] and a3d[1] with the following values:

[0] |

[1] |

[2] |

|

a3d[0][0] |

1 |

0 |

0 |

a3d[0][1] |

4 |

0 |

0 |

[0] |

[1] |

[2] |

|

a3d[1][0] |

7 |

8 |

0 |

a3d[1][1] |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Because all elements that are not associated with an initializer are initialized by default to 0, the following definition has the same effect:

inta3d[][2][3]={{{1},{4}},{{7,8}}};

This initialization list also shows three levels of braces. You do not need to specify that the first dimension has a size of 2, as the outermost initialization list contains two initializers.

You can also omit some of the braces. If a given pair of braces contains more initializers than the number of elements in the corresponding array dimension, then the excess initializers are associated with the next array element in the storage sequence. Hence these two definitions are equivalent:

inta3d[2][2][3]={{1,0,0,4},{7,8}};inta3d[2][2][3]={1,0,0,4,0,0,7,8};

Finally, you can achieve the same initialization pattern using element designators as follows:

inta3d[2][2][3]={1,[0][1][0]=4,[1][0][0]=7,8};

Again, this definition is equivalent to the following:

inta3d[2][2][3]={{1},[0][1]={4},[1][0]={7,8}};

Using element designators is a good idea if only a few elements need to be initialized to a value other than 0.

Arrays as Arguments of Functions

When the name of an array appears as a function argument, the compiler implicitly converts it into a pointer to the array’s first element. Accordingly, the corresponding parameter of the function is always a pointer to the same object type as the type of the array elements.

You can declare the parameter either in array form or in pointer form: type name[ ] or type *name. The strcat() function defined in Example 8-1 illustrates the pointer notation. For more details and examples, see “Arrays as Function Parameters”. Here, however, we’ll take a closer look at the case of multidimensional arrays.

When you pass a multidimensional array as a function argument, the function receives a pointer to an array type. Because this array type is the type of the elements of the outermost array dimension, it must be a complete type. For this reason, you must specify all dimensions of the array elements in the corresponding function parameter declaration.

For example, the type of a matrix parameter is a pointer to a “row” array, and the length of the rows (i.e., the number of “columns”) must be included in the declaration. More specifically, if NCOLS is the number of columns, then the parameter for a matrix of float elements can be declared as follows:

#define NCOLS 10// The number of columns./* ... */voidsomefunction(float(*pMat)[NCOLS]);// A pointer to a row array.

This declaration is equivalent to the following:

voidsomefunction(floatpMat[][NCOLS]);

The parentheses in the parameter declaration float (*pMat)[NCOLS] are necessary in order to declare a pointer to an array of float. Without them, float *pMat[NCOLS] would declare the identifier pMat as an array whose elements have the type float*, or pointer to float. See “Complex Declarators”.

In C99, parameter declarations can contain variable-length arrays. Thus, in a declaration of a pointer to a matrix, the number of columns need not be constant but can be another parameter of the function. For example, you can declare a function as follows:

voidsomeVLAfunction(intncols,floatpMat[][ncols]);

Example 7-5 shows a function that uses a variable-length matrix as a parameter.

If you use multidimensional arrays in your programs, it is a good idea to define a type name for the (n-1)-dimensional elements of an n-dimensional array. Such typedef names can make your programs more readable and your arrays easier to handle. For example, the following typedef statement defines a type for the row arrays of a matrix of float elements (see also “typedef Declarations”):

typedeffloatROW_t[NCOLS];// A type for the "row" arrays.

Example 8-2 illustrates the use of an array type name such as ROW_t. The function printRow() provides formatted output of a row array. The function printMatrix() prints all the rows in the matrix.

Example 8-2. Functions printRow() and printMatrix()

// Print one "row" array.voidprintRow(constROW_tpRow){for(intc=0;c<NCOLS;++c)printf("%6.2f",pRow[c]);putchar('\n');}// Print the whole matrix.voidprintMatrix(constROW_t*pMat,intnRows){for(intr=0;r<nRows;++r)printRow(pMat[r]);// Print each row.}

The parameters pRow and pMat are declared as pointers to const arrays because the functions do not modify the matrix. Because the number of rows is variable, it is passed to the function printMatrix() as a second argument.

The following code fragment defines and initializes an array of rows with type ROW_t, and then calls the function printMatrix():

ROW_tmat[]={{0.0F,0.1F},{1.0F,1.1F,1.2F},{2.0F,2.1F,2.2F,2.3F}};intnRows=sizeof(mat)/sizeof(ROW_t);printMatrix(mat,nRows);