Chapter 12. Dynamic Memory Management

When you’re writing a program, you often don’t know how much data it will have to process, or you can anticipate that the amount of data to process will vary widely. In these cases, efficient resource use demands that you allocate memory only as you actually need it at runtime, and release it again as soon as possible. This is the principle of dynamic memory management, which also has the advantage that a program doesn’t need to be rewritten in order to process larger amounts of data on a system with more available memory.

This chapter describes dynamic memory management in C, and demonstrates the most important functions involved using a general-purpose binary tree implementation as an example.

The standard library provides the following four functions for dynamic memory management:

malloc(),calloc()-

Allocate a new block of memory.

realloc()-

Resize an allocated memory block.

free()-

Release allocated memory.

All of these functions are declared in the header file stdlib.h. The size of an object in memory is specified as a number of bytes. Various header files, including stdlib.h, define the type size_t specifically to hold information of this kind. The sizeof operator, for example, yields a number of bytes with the type size_t.

Allocating Memory Dynamically

The two functions for allocating memory, malloc() and calloc(), have slightly different parameters:

void *malloc( size_tsize);-

The

malloc()function reserves a contiguous memory block whose size in bytes is at leastsize. When a program obtains a memory block throughmalloc(), its contents are undetermined. void *calloc( size_tcount, size_tsize);-

The

calloc()function reserves a block of memory whose size in bytes is at leastcount×size. In other words, the block is large enough to hold an array ofcountelements, each of which takes upsizebytes. Furthermore,calloc()initializes every byte of the memory with the value 0.

Both functions return a pointer to void, also called a typeless pointer. The pointer’s value is the address of the first byte in the memory block allocated, or a null pointer if the memory requested is not available.

When a program assigns the void pointer to a pointer variable of a different type, the compiler implicitly performs the appropriate type conversion. Some programmers prefer to use an explicit type conversion, however.1 When you access locations in the allocated memory block, the type of the pointer you use determines how the contents of the location are interpreted.

Here are some examples:

#include <stdlib.h>// Provides function prototypes.typedefstruct{longkey;/* ... more members ... */}Record;// A structure type.float*myFunc(size_tn){// Reserve storage for an object of type double.double*dPtr=malloc(sizeof(double));if(dPtr==NULL)// Insufficient memory.{/* ... Handle the error ... */returnNULL;}else// Got the memory: use it.{*dPtr=0.07;/* ... */}// Get storage for two objects of type Record.Record*rPtr;if((rPtr=malloc(2*sizeof(Record))==NULL){/* ... Handle the insufficient-memory error ... */returnNULL;}// Get storage for an array of n elements of type float.float*fPtr=malloc(n*sizeof(float));if(fPtr==NULL){/* ... Handle the error ... */returnNULL;}/* ... */returnfPtr;}

It is often useful to initialize every byte of the allocated memory block to zero, which ensures that not only the members of a structure object have the default value zero but also any padding between the members. In such cases, the calloc() function is preferable to malloc(), although it may be slower, depending on the implementation. The size of the block to be allocated is expressed differently with the calloc() function. We can rewrite the statements in the previous example as follows:

// Get storage for an object of type double.double*dPtr=calloc(1,sizeof(double));// Get storage for two objects of type Record.Record*rPtr;if((rPtr=calloc(2,sizeof(Record))==NULL){/* ... Handle the insufficient-memory error ... */}// Get storage for an array of n elements of type float.float*fPtr=calloc(n,sizeof(float));

Characteristics of Allocated Memory

A successful memory allocation call yields a pointer to the beginning of a memory block. “The beginning” means that the pointer’s value is equal to the lowest byte address in the block. The allocated block is aligned so that any type of object can be stored at that address.

An allocated memory block stays reserved for your program until you explicitly release it by calling free() or realloc(). In other words, the storage duration of the block extends from its allocation to its release, or to end of the program.

The arrangement of memory blocks allocated by successive calls to malloc(), calloc(), and/or realloc() is unspecified.

It is also unspecified whether a request for a block of size zero results in a null pointer or an ordinary pointer value. In any case, however, there is no way to use a pointer to a block of zero bytes, except perhaps as an argument to realloc() or free().

Resizing and Releasing Memory

When you no longer need a dynamically allocated memory block, you should give it back to the operating system. You can do this by calling the function free(). Alternatively, you can increase or decrease the size of an allocated memory block by calling the function realloc(). The prototypes of these functions are as follows:

void free( void *ptr);-

The

free()function releases the dynamically allocated memory block that begins at the address inptr. A null pointer value for theptrargument is permitted, and such a call has no effect. void *realloc( void *ptr, size_tsize);-

The

realloc()function releases the memory block addressed byptrand allocates a new block ofsizebytes, returning its address. The new block may start at the same address as the old one.realloc()also preserves the contents of the original memory block—up to the size of whichever block is smaller. If the new block doesn’t begin where the original one did, thenrealloc()copies the contents to the new memory block. If the new memory block is larger than the original, then the values of the additional bytes are unspecified.It is permissible to pass a null pointer to

realloc()as the argumentptr. If you do, thenrealloc()behaves similarly tomalloc(), and reserves a new memory block of the specified size.The

realloc()function returns a null pointer if it is unable to allocate a memory block of the size requested. In this case, it does not release the original memory block or alter its contents.

The pointer argument that you pass to either of the functions free() and realloc()—if it is not a null pointer—must be the starting address of a dynamically allocated memory block that has not yet been freed. In other words, you may pass these functions only a null pointer or a pointer value obtained from a prior call to malloc(), calloc(), or realloc(). If the pointer argument passed to free() or realloc() has any other value, or if you try to free a memory block that has already been freed, the program’s behavior is undefined.

The memory management functions keep internal records of the size of each allocated memory block. This is why the functions free() and realloc() require only the starting address of the block to be released, and not its size. There is no way to test whether a call to the free() function is successful, because it has no return value.

The function getLine() in Example 12-1 is another variant of the function defined with the same name in Example 9-4. It reads a line of text from standard input and stores it in a dynamically allocated buffer. The maximum length of the line to be stored is one of the function’s parameters. The function releases any memory it doesn’t need. The return value is a pointer to the line read.

Example 12-1. The getLine() function

// Read a line of text from stdin into a dynamically allocated buffer.// Replace the newline character with a string terminator.//// Arguments: The maximum line length to read.// Return value: A pointer to the string read, or// NULL if end-of-file was read or if an error occurred.char*getLine(unsignedintlen_max){char*linePtr=malloc(len_max+1);// Reserve storage for "worst case."if(linePtr!=NULL){// Read a line of text and replace the newline characters with// a string terminator:intc=EOF;unsignedinti=0;while(i<len_max&&(c=getchar())!='\n'&&c!=EOF)linePtr[i++]=(char)c;linePtr[i]='\0';if(c==EOF&&i==0)// If end-of-file before any{// characters were read,free(linePtr);// release the whole buffer.linePtr=NULL;}else// Otherwise, release the unused portion.linePtr=realloc(linePtr,i+1);// i is the string length.}returnlinePtr;}

The following code shows how you might call the getLine() function:

char*line;if((line=getLine(128))!=NULL)// If we can read a line,{/* ... */// process the line,free(line);// then release the buffer.}

An All-Purpose Binary Tree

Dynamic memory management is fundamental to the implementation of dynamic data structures such as linked lists and trees. In Chapter 10, we presented a simple linked list (see Figure 10-1). The advantage of linked lists over arrays is that new elements can be inserted and existing members removed quickly. However, they also have the drawback that you have to search through the list in sequential order to find a specific item.

A binary search tree (BST), on the other hand, makes linked data elements more quickly accessible. The data items must have a key value that can be used to compare and sort them. A binary search tree combines the flexibility of a linked list with the advantage of a sorted array, in which you can find a desired data item using the binary search algorithm.

Characteristics

A binary tree consists of a number of nodes that contain the data to be stored (or pointers to the data), and the following structural characteristics:

-

Each node has up to two direct child nodes.

-

There is exactly one node, called the root of the tree, that has no parent node. All other nodes have exactly one parent.

-

Nodes in a binary tree are placed according to this rule: the value of a node is greater than or equal to the values of any descendant in its left branch, and less than or equal to the value of any descendant in its right branch.

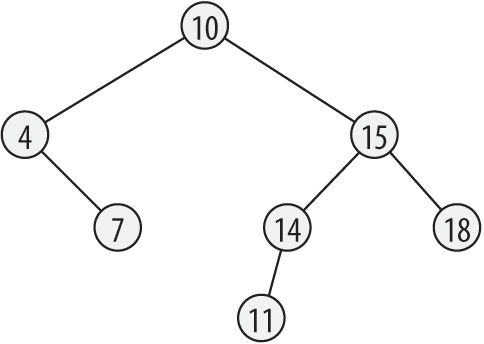

Figure 12-1 illustrates the structure of a binary tree.

Figure 12-1. A binary tree

A leaf is a node that has no children. Each node of the tree is also considered as the root of a subtree, which consists of the node and all its descendants.

An important property of a binary tree is its height. The height is the length of the longest path from the root to any leaf. A path is a succession of linked nodes that form the connection between a given pair of nodes. The length of a path is the number of nodes in the path, not counting the first node. It follows from these definitions that a tree consisting only of its root node has a height of 0, and the height of the tree in Figure 12-1 is 3.

Implementation

The example that follows is an implementation of the principal functions for a binary search tree, and uses dynamic memory management. This tree is intended to be usable for data of any kind. For this reason, the structure type of the nodes includes a flexible member to store the data, and a member indicating the size of the data:

typedefstructNode{structNode*left,// Pointers to the left and*right;// right child nodes.size_tsize;// Size of the data payload.chardata[];// The data itself.}Node_t;

The pointers left and right are null pointers if the node has no left or right child.

As the user of our implementation, you must provide two auxiliary functions. The first of these is a function to obtain a key that corresponds to the data value passed to it, and the second compares two keys. The first function has the following type:

typedefconstvoid*GetKeyFunc_t(constvoid*dData);

The second function has a type like that of the comparison function used by the standard function bsearch():

typedefintCmpFunc_t(constvoid*pKey1,constvoid*pKey2);

The arguments passed on calling the comparison function are pointers to the two keys that you want to compare. The function’s return value is less than zero, if the first key is less than the second; or equal to zero, if the two keys are equal; or greater than zero, if the first key is greater than the second. The key may be the same as the data itself. In this case, you need to provide only a comparison function.

Next, we define a structure type to represent a tree. This structure has three members: a pointer to the root of the tree; a pointer to the function to calculate a key, with the type GetKeyFunc_t; and a pointer to the comparison function, with the type CmpFunc_t:

typedefstruct{structNode*pRoot;// Pointer to the root.CmpFunc_t*cmp;// Compares two keys.GetKeyFunc_t*getKey;// Converts data into a key}BST_t;// value.

The pointer pRoot is a null pointer while the tree is empty.

The elementary operations for a binary search tree are performed by functions that insert, find, and delete nodes, and functions to traverse the tree in various ways, performing a programmer-specified operation on each element if desired.

The prototypes of these functions, and the typedef declarations of GetKeyFunc_t, CmpFunc_t, and BST_t, are placed in the header file BSTree.h. To use this binary tree implementation, you must include this header file in the program’s source code.

The function prototypes in BSTree.h are:

BST_t *newBST( CmpFunc_t *cmp, GetKeyFunc_t *getKey );-

This function dynamically generates a new object with the type

BST_t, and returns a pointer to it. _Bool BST_insert( BST_t *pBST, const void *pData, size_t size );-

BST_insert()dynamically generates a new node, copies the data referenced bypDatato the node, and inserts the node in the specified tree. const void *BST_search( BST_t *pBST, const void *pKey );-

The

BST_search()function searches the tree and returns a pointer to the data item that matches the key referenced by thepKeyargument. _Bool BST_erase( BST_t *pBST, const void *pKey );-

This function deletes the first node whose data contents match the key referenced by

pKey. void BST_clear( BST_t *pBST );-

BST_clear()deletes all nodes in the tree, leaving the tree empty. int BST_inorder( BST_t *pBST, _Bool (*action)( void *pData ));int BST_rev_inorder( BST_t *pBST, _Bool (*action)( void *pData ));int BST_preorder( BST_t *pBST, _Bool (*action)( void *pData ));int BST_postorder( BST_t *pBST, _Bool (*action)( void *pData ));-

Each of these functions traverses the tree in a certain order, and calls the function referenced by

actionto manipulate the data contents of each node. If the action modifies the node’s data, then at least the key value must remain unchanged to preserve the tree’s sorting order.

The function definitions, along with some recursive helper functions, are placed in the source file BSTree.c. The helper functions are declared with the static specifier because they are for internal use only, and not part of the search tree’s “public” interface. The file BSTree.c also contains the definition of the nodes’ structure type. As the programmer, you do not need to deal with the contents of this file, and may be content to use a binary object file compiled for the given system, adding it to the command line when linking the program.

Generating an Empty Tree

When you create a new binary search tree, you specify how a comparison between two data items is performed. For this purpose, the newBST() function takes as its arguments a pointer to a function that compares two keys, and a pointer to a function that calculates a key from an actual data item. The second argument can be a null pointer if the data itself serves as the key for comparison. The return value is a pointer to a new object with the type BST_t:

constvoid*defaultGetKey(constvoid*pData){returnpData;}BST_t*newBST(CmpFunc_t*cmp,GetKeyFunc_t*getKey){BST_t*pBST=NULL;if(cmp!=NULL)pBST=malloc(sizeof(BST_t));if(pBST!=NULL){pBST->pRoot=NULL;pBST->cmp=cmp;pBST->getKey=(getKey!=NULL)?getKey:defaultGetKey;}returnpBST;}

The pointer to BST_t returned by newBST() is the first argument to all the other binary-tree functions. This argument specifies the tree on which you want to perform a given operation.

Inserting New Data

To copy a data item to a new leaf node in the tree, pass the data to the BST_insert() function. The function inserts the new leaf at a position that is consistent with the binary tree’s sorting condition. The recursive algorithm involved is simple: if the current subtree is empty—that is, if the pointer to its root node is a null pointer—then insert the new node as the root by making the parent point to it. If the subtree is not empty, continue with the left subtree if the new data is less than the current node’s data; otherwise, continue with the right subtree. The recursive helper function insert() applies this algorithm.

The insert() function takes an additional argument, which is a pointer to a pointer to the root node of a subtree. Because this argument is a pointer to a pointer, the function can modify it in order to link a new node to its parent. BST_insert() returns true if it succeeds in inserting the new data; otherwise, false.

static_Boolinsert(BST_t*pBST,Node_t**ppNode,constvoid*pData,size_tsize);_BoolBST_insert(BST_t*pBST,constvoid*pData,size_tsize){if(pBST==NULL||pData==NULL||size==0)returnfalse;returninsert(pBST,&(pBST->pRoot),pData,size);}static_Boolinsert(BST_t*pBST,Node_t**ppNode,constvoid*pData,size_tsize){Node_t*pNode=*ppNode;// Pointer to the root node of the// subtree to insert the new node in.if(pNode==NULL){// There's a place for a new leaf here.pNode=malloc(sizeof(Node_t)+size);if(pNode!=NULL){pNode->left=pNode->right=NULL;// Initialize the new node's// members.memcpy(pNode->data,pData,size);*ppNode=pNode;// Insert the new node.returntrue;}elsereturnfalse;}else// Continue looking for a place ...{constvoid*key1=pBST->getKey(pData),*key2=pBST->getKey(pNode->data);if(pBST->cmp(key1,key2)<0)// ... in the left subtree,returninsert(pBST,&(pNode->left),pData,size);else// or in the right subtree.returninsert(pBST,&(pNode->right),pData,size);}}

Finding Data in the Tree

The function BST_search() uses the binary search algorithm to find a data item that matches a given key. If a given node’s data does not match the key, the search continues in the node’s left subtree if the key is less than that of the node’s data, or in the right subtree if the key is greater. The return value is a pointer to the data item from the first node that matches the key, or a null pointer if no match was found.

The search operation uses the recursive helper function search(). Like insert(), search() takes as its second parameter a pointer to the root node of the subtree to be searched:

staticconstvoid*search(BST_t*pBST,constNode_t*pNode,constvoid*pKey);constvoid*BST_search(BST_t*pBST,constvoid*pKey){if(pBST==NULL||pKey==NULL)returnNULL;returnsearch(pBST,pBST->pRoot,pKey);// Start at the root// of the tree.}staticconstvoid*search(BST_t*pBST,constNode_t*pNode,constvoid*pKey){if(pNode==NULL)returnNULL;// No subtree to search;// no match found.else{// Compare data:intcmp_res=pBST->cmp(pKey,pBST->getKey(pNode->data));if(cmp_res==0)// Found a match.returnpNode->data;elseif(cmp_res<0)// Continue the searchreturnsearch(pBST,pNode->left,pKey);// in the left subtree,elsereturnsearch(pBST,pNode->right,pKey);// or in the right// subtree.}}

Removing Data from the Tree

The BST_erase() function searches for a node that matches the specified key, and deletes it if found. Deleting means removing the node from the tree structure and releasing the memory it occupies. The function returns false if it fails to find a matching node to delete, or true if successful.

The actual searching and deleting is performed by means of the recursive helper function erase(). The node needs to be removed from the tree in such a way that the tree’s sorting condition is not violated. A node that has no more than one child can be removed simply by linking its child, if any, to its parent. If the node to be removed has two children, though, the operation is more complicated: you have to replace the node you are removing with the node from the right subtree that has the smallest data value. This is never a node with two children. For example, to remove the root node from the tree in Figure 12-1, we would replace it with the node that has the value 11. This removal algorithm is not the only possible one, but it has the advantage of not increasing the tree’s height.

The recursive helper function detachMin() plucks the minimum node from a specified subtree, and returns a pointer to the node:

staticNode_t*detachMin(Node_t**ppNode){Node_t*pNode=*ppNode;// A pointer to the current node.if(pNode==NULL)returnNULL;// pNode is an empty subtree.elseif(pNode->left!=NULL)returndetachMin(&(pNode->left));// The minimum is in the left// subtree.else{// pNode points to the minimum node.*ppNode=pNode->right;// Attach the right child to the parent.returnpNode;}}

Now we can use this function in the definition of erase() and BST_erase():

static_Boolerase(BST_t*pBST,Node_t**ppNode,constvoid*pKey);_BoolBST_erase(BST_t*pBST,constvoid*pKey){if(pBST==NULL||pKey==NULL)returnfalse;returnerase(pBST,&(pBST->pRoot),pKey);// Start at the root// of the tree.}static_Boolerase(BST_t*pBST,Node_t**ppNode,constvoid*pKey){Node_t*pNode=*ppNode;// Pointer to the current node.if(pNode==NULL)returnfalse;// No match found.// Compare data:intcmp_res=pBST->cmp(pKey,pBST->getKey(pNode->data));if(cmp_res<0)// Continue the searchreturnerase(pBST,&(pNode->left),pKey);// in the left subtree,elseif(cmp_res>0)returnerase(pBST,&(pNode->right),pKey);// or in the right// subtree.else{// Found the node to be deleted.if(pNode->left==NULL)// If no more than one child,*ppNode=pNode->right;// attach the child to the parent.elseif(pNode->right==NULL)*ppNode=pNode->left;else// Two children: replace the node with{// the minimum from the right subtree.Node_t*pMin=detachMin(&(pNode->right));*ppNode=pMin;// Graft it onto the deleted node's parent.pMin->left=pNode->left;// Graft the deleted node's children.pMin->right=pNode->right;}free(pNode);// Release the deleted node's storage.returntrue;}}

A function in Example 12-2, BST_clear(), deletes all the nodes of a tree. The recursive helper function clear() deletes first the descendants of the node referenced by its argument and then the node itself.

Example 12-2. The BST_clear() and clear() functions

staticvoidclear(Node_t*pNode);voidBST_clear(BST_t*pBST){if(pBST!=NULL){clear(pBST->pRoot);pBST->pRoot=NULL;}}staticvoidclear(Node_t*pNode){if(pNode!=NULL){clear(pNode->left);clear(pNode->right);free(pNode);}}

Traversing a Tree

There are several recursive schemes for traversing a binary tree. They are often designated by abbreviations in which L stands for a given node’s left subtree, R for its right subtree, and N for the node itself:

- In-order or LNR traversal

-

First traverse the node’s left subtree, then visit the node itself, then traverse the right subtree.

- Pre-order or NLR traversal

-

First visit the node itself, then traverse its left subtree, then its right subtree.

- Post-order or LRN traversal

-

First traverse the node’s left subtree, then the right subtree, then visit the node itself.

An in-order traversal visits all the nodes in their sorting order, from least to greatest. If you print each node’s data as you visit it, the output appears sorted.

It’s not always advantageous to process the data items in their sorting order, though. For example, if you want to store the data items in a file and later insert them in a new tree as you read them from the file, you might prefer to traverse the tree in pre-order. Then reading each data item in the file and inserting it will reproduce the original tree structure. And the clear() function in Example 12-2 uses a post-order traversal to avoid destroying any node before its children.

Each of the traversal functions takes as its second argument a pointer to an “action” function that it calls for each node visited. The action function takes as its argument a pointer to the current node’s data, and returns true to indicate success and false on failure. This functioning enables the tree-traversal functions to return the number of times the action was performed successfully.

The following example contains the definition of the BST_inorder() function, and its recursive helper function inorder() (the other traversal functions are similar):

staticintinorder(Node_t*pNode,_Bool(*action)(void*pData));intBST_inorder(BST_t*pBST,_Bool(*action)(void*pData)){if(pBST==NULL||action==NULL)return0;elsereturninorder(pBST->pRoot,action);}staticintinorder(Node_t*pNode,_Bool(*action)(void*pData)){intcount=0;if(pNode==NULL)return0;count=inorder(pNode->left,action);// L: Traverse the left// subtree.if(action(pNode->data))// N: Visit the current++count;// node itself.count+=inorder(pNode->right,action);// R: Traverse the right// subtree.returncount;}

A Sample Application

To illustrate one use of a binary search tree, the filter program in Example 12-3, sortlines, presents a simple variant of the Unix utility sort. It reads text line by line from the standard input stream, and prints the lines in sorted order to standard output. A typical command line to invoke the program might be:

sortlines<demo.txt

This command prints the contents of the file demo.txt to the console.

Example 12-3. The sortlines program

// This program reads each line of text into a node of a binary tree,// and then prints the text in sorted order.#include <stdio.h>#include <string.h>#include <stdlib.h>#include "BSTree.h"// Prototypes of the BST functions.#define LEN_MAX 1000// Maximum length of a line.charbuffer[LEN_MAX];// Action to perform for each line:_BoolprintStr(void*str){returnprintf("%s",str)>=0;}intmain(){BST_t*pStrTree=newBST((CmpFunc_t*)strcmp,NULL);intn;while(fgets(buffer,LEN_MAX,stdin)!=NULL)// Read each line.{size_tlen=strlen(buffer);// Length incl.// newline character.if(!BST_insert(pStrTree,buffer,len+1))// Insert the line inbreak;// the tree.}if(!feof(stdin)){// If unable to read// the entire text:fprintf(stderr,"sortlines: ""Error reading or storing text input.\n");exit(EXIT_FAILURE);}n=BST_inorder(pStrTree,printStr);// Print each line,// in sorted order.fprintf(stderr,"\nsortlines: Printed %d lines.\n",n);BST_clear(pStrTree);// Discard all nodes.return0;}

The loop that reads input lines breaks prematurely if a read error occurs, or if there is insufficient memory to insert a new node in the tree. In such cases, the program exits with an error message.

An in-order traversal visits every node of the tree in sorted order. The return value of BST_inorder() is the number of lines successfully printed. sortlines prints the error and success information to the standard error stream, so that it is separate from the actual data output. Redirecting standard output to a file or a pipe affects the sorted text but not these messages.

The BST_clear() function call is technically superfluous, as all of the program’s dynamically allocated memory is automatically released when the program exits.

The binary search tree presented in this chapter can be used for any kind of data. Most applications require the BST_search() and BST_erase() functions in addition to those used in Example 12-3. Furthermore, more complex programs will no doubt require functions not presented here, such as one to keep the tree’s left and right branches balanced.

1 Perhaps in part for historic reasons: in early C dialects, malloc() returned a pointer to char.