Chapter 10. Structures, Unions, and Bit-Fields

The pieces of information that describe the characteristics of objects, such as information on companies or customers, are generally grouped together in records. Records make it easy to organize, present, and store information about similar objects.

A record is composed of fields that contain the individual details, such as the name, address, and legal form of a company. In C, you determine the names and types of the fields in a record by defining a structure type. The fields are called the members of the structure.

A union is defined in the same way as a structure. Unlike the members of a structure, all the members of a union start at the same address. Hence you define a union type when you want to use the same location in memory for different types of objects.

In addition to the basic and derived types, the members of structures and unions can also include bit-fields. A bit-field is an integer variable composed of a specified number of bits. By defining bit-fields, you can break down an addressable memory unit into groups of individual bits that you can address by name.

Structures

A structure type is a type defined within the program that specifies the format of a record, including the names and types of its members, and the order in which they are stored. Once you have defined a structure type, you can use it like any other type in declaring objects, pointers to those objects, and arrays of such structure elements.

Defining Structure Types

The definition of a structure type begins with the keyword struct, and contains a list of declarations of the structure’s members, in braces:

struct [tag_name] { member_declaration_list };

A structure must contain at least one member. The following example defines the type struct Date, which has three members of type short:

structDate{shortmonth,day,year;};

The identifier Date is this structure type’s tag. The identifiers year, month, and day are the names of its members. The tags of structure types are a distinct name space: the compiler distinguishes them from variables or functions whose names are the same as a structure tag. Likewise, the names of structure members form a separate name space for each structure type. In this book, we have generally capitalized the first letter in the names of structure, union, and enumeration types: this is merely a common convention to help programmers distinguish such names from those of variables.

The members of a structure may have any desired complete type, including previously defined structure types. They must not be variable-length arrays, or pointers to such arrays.

The following structure type, struct Song, has five members to store five pieces of information about a music recording. The member published has the type struct Date, defined in the previous example:

structSong{chartitle[64];charartist[32];charcomposer[32];shortduration;// Playing time in seconds.structDatepublished;// Date of publication.};

A structure type cannot contain itself as a member, as its definition is not complete until the closing brace (}). However, structure types can and often do contain pointers to their own type. Such self-referential structures are used in implementing linked lists and binary trees, for example. The following example defines a type for the members of a singly linked list:

structCell{structSongsong;// This record's data.structCell*pNext;// A pointer to the next record.};

If you use a structure type in several source files, you should place its definition in an included header file. Typically, the same header file will contain the prototypes of the functions that operate on structures of that type. Then you can use the structure type and the corresponding functions in any source file that includes the given header file.

Structure Objects and typedef Names

Within the scope of a structure type definition, you can declare objects of that type:

structSongsong1,song2,*pSong=&song1;

This example defines song1 and song2 as objects of type struct Song, and pSong as a pointer that points to the object song1. The keyword struct must be included whenever you use the structure type. You can also use typedef to define a one-word name for a structure type:

typedefstructSongSong_t;// Song_t is now a synonym for// struct Song.Song_tsong1,song2,*pSong=&song1;// Two struct Song objects and a// struct Song pointer.

Objects with a structure type, such as song1 and song2 in our example, are called structure objects (or structure variables) for short.

You can also define a structure type without a tag. This approach is practical only if you define objects at the same time and don’t need the type for anything else, or if you define the structure type in a typedef declaration so that it has a name after all. Here is an example:

typedefstruct{structCell*pFirst,*pLast;}SongList_t;

This typedef declaration defines SongList_t as a name for the structure type whose members are two pointers to struct Cell named pFirst and pLast.

Incomplete Structure Types

You can define pointers to a structure type even when the structure type has not yet been defined. Thus, the definition of SongList_t in the previous example would be permissible and correct even if struct Cell had not yet been defined. In such a case, the definition of SongList_t would implicitly declare the name Cell as a structure tag. However, the type struct Cell would remain incomplete until explicitly defined. The pointers pFirst and pLast, whose type is struct Cell *, cannot be used to access objects until the type struct Cell is completely defined, with declarations of its structure members between braces.

The ability to declare pointers to incomplete structure types allows you to define structure types that refer to each other. Here is a simple example:

structA{structB*pB;/* ... other members of struct A ... */};structB{structA*pA;/* ... other members of struct B ... */};

These declarations are correct and behave as expected, except in the following case: if they occur within a block, and the structure type struct B has already been defined in a larger scope, then the declaration of the member pB in structure A declares a pointer to the type already defined, and not to the type struct B defined after struct A. To preclude this interference from the outer scope, you can insert an “empty” declaration of struct B before the definition of struct A:

structB;structA{structB*pB;/* ... */};structB{structA*pA;/* ... */};

This example declares B as a new structure tag that hides an existing structure tag from the larger scope, if there is one.

Accessing Structure Members

Two operators allow you to access the members of a structure object: the dot operator (.) and the arrow operator (->). Both of them are binary operators whose right operand is the name of a member.

The left operand of the dot operator is an expression that yields a structure object. Here are a few examples using the structure struct Song:

#include <string.h>// Prototypes of string functions.Song_tsong1,song2,// Two objects of type Song_t,*pSong=&song1;// and a pointer to Song_t.// Copy a string to the title of song1:strcpy(song1.title,"Havana Club");// Likewise for the composer member:strcpy(song1.composer,"Ottmar Liebert");song1.duration=251;// Playing time.// The member published is itself a structure:song1.published.year=1998;// Year of publication.if((*pSong).duration>180)printf("The song %s is more than 3 minutes long.\n",(*pSong).title);

Because the pointer pSong points to the object song1, the expression *pSong denotes the object song1, and (*pSong).duration denotes the member duration in song1. The parentheses are necessary because the dot operator has a higher precedence than the indirection operator (see Table 5-4).

If you have a pointer to a structure, you can use the arrow operator -> to access the structure’s members instead of the indirection and dot operators (* and .). In other words, an expression of the form p->m is equivalent to (*p).m. Thus, we might rewrite the if statement in the previous example using the arrow operator as follows:

if(pSong->duration>180)printf("The song %s is more than 3 minutes long.\n",pSong->title);

You can use an assignment to copy the entire contents of a structure object to another object of the same type:

song2=song1;

After this assignment, each member of song2 has the same value as the corresponding member of song1. Similarly, if a function parameter has a structure type, then the contents of the corresponding argument are copied to the parameter when you call the function. This approach can be rather inefficient unless the structure is small, as in Example 10-1.

Example 10-1. The function dateAsString()

// The function dateAsString() converts a date from a structure of type// struct Date into a string of the form mm/dd/yyyy.// Argument: A date value of type struct Date.// Return value: A pointer to a static buffer containing the date string.constchar*dateAsString(structDated){staticcharstrDate[12];sprintf(strDate,"%02d/%02d/%04d",d.month,d.day,d.year);returnstrDate;}

Larger structures are generally passed by reference. In Example 10-2, the function call copies only the address of a Song object, not the structure’s contents. Furthermore, as the function does not modify the structure object, the parameter is a read-only pointer. Thus, you can also pass this function a pointer to a constant object.

Example 10-2. The function printSong()

// The printSong() function prints out the contents of a structure// of type Song_t in a tabular format.// Argument: A pointer to the structure object to be printed.// Return value: None.voidprintSong(constSong_t*pSong){intm=pSong->duration/60,// Playing time in minutess=pSong->duration%60;// and seconds.printf("------------------------------------------\n""Title: %s\n""Artist: %s\n""Composer: %s\n""Playing time: %d:%02d\n""Date: %s\n",pSong->title,pSong->artist,pSong->composer,m,s,dateAsString(pSong->published));}

The song’s playing time is printed in the format m:ss. The function dateAsString() converts the publication date from a structure to string format.

Initializing Structures

When you define structure objects without explicitly initializing them, the usual initialization rules apply: if the structure object has automatic storage class, then its members have indeterminate initial values. If, on the other hand, the structure object has static storage duration, then the initial value of its members is zero, or if they have pointer types, a null pointer (see “Initialization”).

To initialize a structure object explicitly when you define it, you must use an initialization list: this is a comma-separated list of initializers, or initial values for the individual structure members, enclosed in braces. The initializers are associated with the members in the order of their declarations: the first initializer is associated with the first member, the second initializer goes with the second member, and so forth. Of course, each initializer must have a type that matches (or can be implicitly converted into) the type of the corresponding member. Here is an example:

Song_tmySong={"What It Is","Aubrey Haynie; Mark Knopfler","Mark Knopfler",297,{9,26,2000}};

This list contains an initializer for each member. Because the member published has a structure type, its initializer is another initialization list.

You may also specify fewer initializers than the number of members in the structure. In this case, any remaining members are initialized to zero.

Song_tyourSong={"El Macho"};

After this definition, all members of yourSong have the value zero, except for the first member. The char arrays contain empty strings, and the member published contains the invalid date { 0, 0, 0 }.

The initializers may be nonconstant expressions if the structure object has automatic storage class. You can also initialize a new, automatic structure variable with a existing object of the same type:

Song_tyourSong=mySong;// Valid initialization within a block

Initializing Specific Members

The C99 standard allows you to explicitly associate an initializer with a certain member. To do so, you must prefix a member designator with an equal sign to the initializer. The general form of a designator for the structure member member is:

.member // Member designator

The declaration in the following example initializes a Song_t object using the member designators .title and .composer:

Song_taSong={.title="I've Just Seen a Face",.composer="John Lennon; Paul McCartney",127};

The member designator .title is actually superfluous here because title is the first member of the structure. An initializer with no designator is associated with the first member, if it is the first initializer, or with the member that follows the last member initialized. Thus, in the previous example, the value 127 initializes the member duration. All other members of the structure have the initial value 0.

Structure Members in Memory

The members of a structure object are stored in memory in the order in which they are declared in the structure type’s definition. The address of the first member is identical with the address of the structure object itself. The address of each member declared after the first one is greater than those of members declared earlier.

Sometimes it is useful to obtain the offset of a member from the beginning address of the structure. This offset, as a number of bytes, is given by the macro offsetof, defined in the header file stddef.h. The macro’s arguments are the structure type and the name of the member:

offsetof(structure_type, member )

The result has the type size_t. As an example, if pSong is a pointer to a Song_t structure, then we can initialize the pointer ptr with the address of the first character in the member composer:

char*ptr=(char*)pSong+offsetof(Song_t,composer);

The compiler may align the members of a structure on certain kinds of addresses, such as 32-bit boundaries, to ensure fast access to the members. This step results in gaps, or unused bytes between the members. The compiler may also add extra bytes, commonly called padding, to the structure after the last member. As a result, the size of a structure can be greater than the sum of its members’ sizes. You should always use the sizeof operator to obtain a structure’s size, and the offsetof macro to obtain the positions of its members.

You can control the compiler’s alignment of structure members—to avoid gaps between members, for example—by means of compiler options, such as the -fpack-struct flag for GCC, or the /Zp1 command-line option or the pragma pack(1) for Visual C/C++. However, you should use these options only if your program places special requirements on the alignment of structure elements (for conformance to hardware interfaces, for example).

Programs need to determine the sizes of structures when allocating memory for objects, or when writing the contents of structure objects to a binary file. In the following example, fp is the FILE pointer to a file opened for writing binary data:

#include <stdio.h>// Prototype of fwrite()./* ... */if(fwrite(&aSong,sizeof(aSong),1,fp)<1)fprintf(stderr,"Error writing\"%s\".\n",aSong.title);

If the function call is successful, fwrite() writes one data object of size sizeof(aSong), beginning at the address &aSong, to the file opened with the FILE pointer fp.

Flexible Structure Members

C99 allows the last member of a structure with more than one member to have an incomplete array type—that is, the last member may be declared as an array of unspecified length. Such a structure member is called a flexible array member. In the following example, array is the name of a flexible member:

typedefstruct{intlen;floatarray[];}DynArray_t;

There are only two cases in which the compiler gives special treatment to a flexible member:

-

The size of a structure that ends in a flexible array member is equal to the offset of the flexible member. In other words, the flexible member is not counted in calculating the size of the structure (although any padding that precedes the flexible member is counted). For example, the expressions

sizeof(DynArray_t)andoffsetof( DynArray_t, array )yield the same value. -

When you access the flexible member using the dot or arrow operator (

.or->), you the programmer must make sure that the object in memory is large enough to contain the flexible member’s value. You can do this by allocating the necessary memory dynamically. Here is an example:DynArray_t*daPtr=malloc(sizeof(DynArray_t)+10*sizeof(float));This initialization reserves space for ten elements in the flexible array member. Now you can perform the following operations:

daPtr->len=10;for(inti=0;i<daPtr->len;++i)daPtr->array[i]=1.0F/(i+1);Because you have allocated space for only ten array elements in the flexible member, the following assignment is not permitted:

daPtr->array[10]=0.1F// Invalid array index.Although some implementations of the C standard library are aimed at making programs safer from such array index errors, you should avoid them by careful programming. In all other operations, the flexible member of the structure is ignored, as in this structure assignment, for example:

DynArray_tda1;da1=*daPtr;

This assignment copies only the member len of the object addressed by daPtr, not the elements of the object’s array member. In fact, the left operand, da1, doesn’t even have storage space for the array. But even when the left operand of the assignment has sufficient space available, the flexible member is still ignored.

C99 also doesn’t allow you to initialize a flexible structure member:

DynArray_tda1={100},// OK.da2={3,{1.0F,0.5F,0.25F}};// Error.

Nonetheless, many compilers support language extensions that allow you to initialize a flexible structure member and generate an object of sufficient size to contain those elements that you initialize explicitly.

Pointers as Structure Members

To include data items that can vary in size in a structure, it is a good idea to use a pointer rather than including the actual data object in the structure. The pointer then addresses the data in a separate object for which you allocate the necessary storage space dynamically. Moreover, this indirect approach allows a structure to have more than one variable-length “member.”

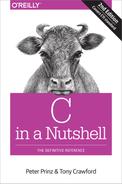

Pointers as structure members are also very useful in implementing dynamic data structures. The structure types SongList_t and Cell_t that we defined earlier in this chapter for the head and items of a list are an example:

// Structures for a list head and list items:typedefstruct{structCell*pFirst,*pLast;}SongList_t;typedefstructCell{structSongsong;// The record data.structCell*pNext;// A pointer to the next// record.}Cell_t;

Figure 10-1 illustrates the structure of a singly linked list made of these structures.

Figure 10-1. A singly linked list

Special attention is required when manipulating such structures. For example, it generally makes little sense to copy structure objects with pointer members, or to save them in files. Usually, the data referenced needs to be copied or saved, and the pointer to it does not. For example, if you want to initialize a new list, named yourList, with the existing list myList, you probably don’t want to do this:

SongList_tyourList=myList;

Such an initialization simply makes a copy of the pointers in myList without creating any new objects for yourList. To copy the list itself, you have to duplicate each object in it. The function cloneSongList(), defined in Example 10-3, does just that:

SongList_tyourList=cloneSongList(&myList);

The function cloneSongList() creates a new object for each item linked to myList, copies the item’s contents to the new object, and links the new object to the new list. cloneSongList() calls appendSong() to do the actual creating and linking. If an error occurs, such as insufficient memory to duplicate all the list items, then cloneSongList() releases the memory allocated up to that point and returns an empty list. The function clearSongList() destroys all the items in a list.

Example 10-3. The functions cloneSongList(), appendSong(), and clearSongList()

// The function cloneSongList() duplicates a linked list.// Argument: A pointer to the list head of the list to be cloned.// Return value: The new list. If insufficient memory is available to// duplicate the entire list, the new list is empty.#include "songs.h"// Contains type definitions (Song_t, etc.) and// function prototypes for song-list operations.SongList_tcloneSongList(constSongList_t*pList){SongList_tnewSL={NULL,NULL};// A new, empty list.Cell_t*pCell=pList->pFirst;// We start with the first list item.while(pCell!=NULL&&appendSong(&newSL,&pCell->song))pCell=pCell->pNext;if(pCell!=NULL)// If we didn't finish the last item,clearSongList(&newSL);// discard any items cloned.returnnewSL;// In either case, return the list head.}// The function appendSong() dynamically allocates a new list item, copies// the given song data to the new object, and appends it to the list.// Arguments: A pointer to a Song_t object to be copied, and a pointer// to a list to add the copy to.// Return value: True if successful; otherwise, false.boolappendSong(SongList_t*pList,constSong_t*pSong){Cell_t*pCell=calloc(1,sizeof(Cell_t));// Create a new list item.if(pCell==NULL)returnfalse;// Failure: no memory.pCell->song=*pSong;// Copy data to the new item.pCell->pNext=NULL;if(pList->pFirst==NULL)// If the list is still empty,pList->pFirst=pList->pLast=pCell;// link a first (and last) item.else{// If not,pList->pLast->pNext=pCell;// insert a new last item.pList->pLast=pCell;}returntrue;// Success.}// The function clearSongList() destroys all the items in a list.// Argument: A pointer to the list head.voidclearSongList(SongList_t*pList){Cell_t*pCell,*pNextCell;for(pCell=pList->pFirst;pCell!=NULL;pCell=pNextCell){pNextCell=pCell->pNext;free(pCell);// Release the memory allocated for each item.}pList->pFirst=pList->pLast=NULL;}

Before the function clearSongList() frees each item, it has to save the pointer to the item that follows; you can’t read a structure object member after the object has been destroyed. The header file songs.h included in Example 10-3 is the place to put all the type definitions and function prototypes needed to implement and use the song list, including declarations of the functions defined in the example itself. The header songs.h must also include the header file stdbool.h because the appendSong() function uses the identifiers bool, true, and false.

Unions

Unlike structure members, which all have distinct locations in the structure, the members of a union all share the same location in memory; that is, all members of a union start at the same address. Thus, you can define a union with many members, but only one member can contain a value at any given time. Unions are an easy way for programmers to use a location in memory in different ways.

Defining Union Types

The definition of a union is formally the same as that of a structure, except for the keyword union in place of struct:

union [tag_name] { member_declaration_list };

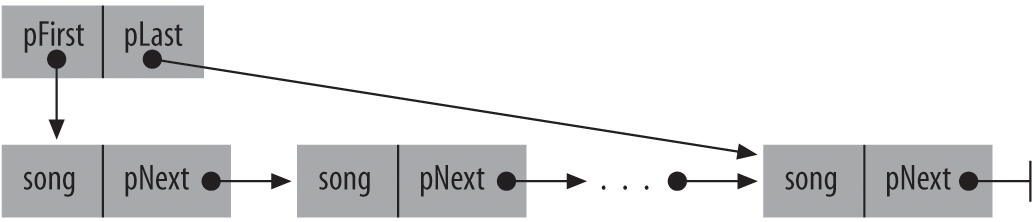

The following example defines a union type named Data which has the three members i, x, and str:

unionData{inti;doublex;charstr[16];};

An object of this type can store an integer, a floating-point number, or a short string. This declaration defines var as an object of type union Data, and myData as an array of 100 elements of type union Data (a union is at least as big as its largest member):

unionDatavar,myData[100];

To obtain the size of a union, use the sizeof operator. Using our example, sizeof(var) yields the value 16, and sizeof(myData) yields 1,600.

As Figure 10-2 illustrates, all the members of a union begin at the same address in memory.

Figure 10-2. An object of the type union Data in memory

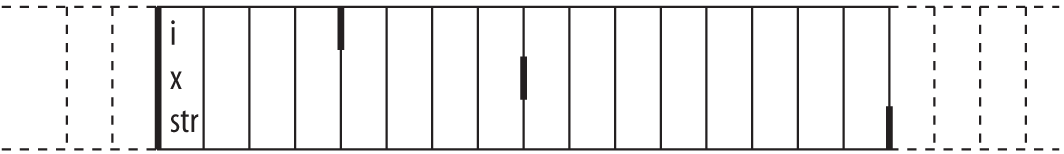

To illustrate how unions are different from structures, consider an object of the type struct Record with members i, x, and str, defined as follows:

structRecord{inti;doublex;charstr[16];};

As Figure 10-3 shows, each member of a structure object has a separate location in memory.

Figure 10-3. An object of the type struct Record in memory

You can access the members of a union in the same ways as structure members. The only difference is that when you change the value of a union member, you modify all the members of the union. Here are a few examples using the union objects var and myData:

var.x=3.21;var.x+=0.5;strcpy(var.str,"Jim");// Occupies the place of var.x.myData[0].i=50;for(inti=0;i<50;++i)myData[i].i=2*i;

As for structures, the members of each union type form a name space unto themselves. Hence, in the last of these statements, the index variable i and the union member i identify two distinct objects.

You, the programmer, are responsible for making sure that the momentary contents of a union object are interpreted correctly. The different types of the union’s members allow you to interpret the same collection of byte values in different ways. For example, the following loop uses a union to illustrate the storage of a double value in memory:

var.x=1.25;for(inti=sizeof(double)−1;i>=0;--i)printf("%02X ",(unsignedchar)var.str[i]);

This loop begins with the highest byte of var.x, and generates the following output:

3F F4 00 00 00 00 00 00

Initializing Unions

Like structures, union objects are initialized by an initialization list. For a union, though, the list can only contain one initializer. As for structures, C99 allows the use of a member designator in the initializer to indicate which member of the union is being initialized. Furthermore, if the initializer has no member designator, then it is associated with the first member of the union. A union object with automatic storage class can also be initialized with an existing object of the same type. Here are some examples:

unionDatavar1={77},var2={.str="Mary"},var3=var1,myData[100]={{.x=0.5},{1},var2};

The array elements of myData for which no initializer is specified are implicitly initialized to the value 0.

Anonymous Structures and Unions

Anonymous structures and unions are a new feature of the C11 standard that permits still greater flexibility in defining structure and union types. A structure or union is called anonymous if it is defined as an unnamed member of a structure or union type and has no tag name. In the following example, the second member of the union type WordByte is an anonymous structure type:

unionWordByte{shortw;struct{charb0,b1};// Anonymous structure};

The members of an anonymous structure or union are treated as members of the structure or union type that contains the anonymous type.

unionWordBytewb={256};charlowByte=wb.b0;

This rule is applied recursively if the containing structure or union is also anonymous. The following example shows members in a nested anonymous type:

structDemo{union// Anonymous union{struct{longa,b;};// Anonymous structurestruct{floatx,y;}fl;// Named member, not anonymous}}dObj;

After this definition, the assignment dObj.a = 100; would be correct. However, you could not directly address x and y as members of dObj; they must be identified as members of dObj.fl:

dObj.a=100;// RightdObj.y=1.0;// Wrong!dObj.fl.y=1.0;// Right

Bit-Fields

Members of structures or unions can also be bit-fields. A bit-field is an integer variable that consists of a specified number of bits. If you declare several small bit-fields in succession, the compiler packs them into a single machine word. This permits very compact storage of small units of information. Of course, you can also manipulate individual bits using the bitwise operators, but bit-fields offer the advantage of handling bits by name, like any other structure or union member.

The declaration of a bit-field has the form:

type [member_name] : width ;

The parts of this syntax are as follows:

type-

An integer type that determines how the bit-field’s value is interpreted. The type may be

_Bool,int,signed int,unsigned int, or another type defined by the given implementation. The type may also include type qualifiers.Bit-fields with type

signed intare interpreted as signed; bit-fields whose type isunsigned intare interpreted as unsigned. Bit-fields of typeintmay be signed or unsigned, depending on the compiler. member_name-

The name of the bit-field, which is optional. If you declare a bit-field with no name, though, there is no way to access it. Nameless bit-fields can serve only as padding to align subsequent bit-fields to a certain position in a machine word.

width-

The number of bits in the bit-field. The width must be a constant integer expression whose value is non-negative, and must be less than or equal to the bit width of the specified type.

Nameless bit-fields can have zero width. In this case, the next bit-field declared is aligned at the beginning of a new addressable storage unit.

When you declare a bit-field in a structure or union, the compiler allocates an addressable unit of memory that is large enough to accommodate it. Usually, the storage unit allocated is a machine word whose size is that of the type int. If the following bit-field fits in the rest of the same storage unit, then it is defined as being adjacent to the previous bit-field. If the next bit-field does not fit in the remaining bits of the same unit, then the compiler allocates another storage unit, and may place the next bit-field at the start of new unit, or wrap it across the end of one storage unit and the beginning of the next.

The following example redefines the structure type struct Date so that the members month and day occupy only as many bits as necessary. To demonstrate a bit-field of type _Bool, we have also added a flag for daylight saving time. This code assumes that the target machine uses words of at least 32 bits:

structDate{unsignedintmonth:4;// 1 is January; 12 is December.unsignedintday:5;// The day of the month (1 to 31).signedintyear:22;// (-2097152 to +2097151)_BoolisDST:1;// True if daylight saving time is in effect.};

A bit-field of n bits can have 2n distinct values. The structure member month now has a value range from 0 to 15; the member day has the value range from 0 to 31; and the value range of the member year is from -2097152 to +2097151. We can initialize an object of type struct Date in the normal way, using an initialization list:

structDatebirthday={5,17,1982};

The object birthday occupies the same amount of storage space as a 32-bit int object. Unlike other structure members, bit-fields generally do not occupy an addressable location in memory. You cannot apply the address operator (&) or the offsetof macro to a bit-field.

In all other respects, however, you can treat bit-fields the same as other structure or union members; use the dot and arrow operators to access them, and perform arithmetic with them as with int or unsigned int variables. As a result, the new definition of the Date structure using bit-fields does not necessitate any changes in the dateAsString() function:

constchar*dateAsString(structDated){staticcharstrDate[12];sprintf(strDate,"%02d/%02d/%04d",d.month,d.day,d.year);returnstrDate;}

The following statement calls the dateAsString() function for the object birthday, and prints the result using the standard function puts():

puts(dateAsString(birthday));