Now that you’ve gotten the feel for how programming happens on the computer, it’s time to stop and consider how projects get from concept to code. In the previous chapters, this book has dictated what you programmed, and each time you ended up with exactly what the book proscribed.

In the real world, though, you have to plan what you’re going to program before you sit down to write code. If you fail to do that, you generally end up with a game that’s so poorly coded that you have to throw it out and start from scratch, or else it runs slowly and inefficiently. Planning reduces your time fumbling around with code and increases the time you get to spend on successful programming, graphics, sound, and other non-essential additions to your game.

The good news is that the planning process is still programming, only instead of writing code, you’re using logic and mental equations to program with pen and paper. Any good system can be implemented on paper, so don’t fool yourself into thinking that computers are unique. It’s just as important to understand programming and game design in the physical world as it is to understand how those concepts get translated into digital bytes.

Game Theory

What is a game? Most of us play games in some form, but few of us stop to consider what makes a game feel like a game. You have now programmed at least two games, and if you think about what you have learned, you will likely detect a few common elements not only in what you have made but also in other games you may have played.

You might think, at first, that a game requires competition. While some games do require players to compete against one another, other games require them to work together to defeat a common threat. In some games, a player is just trying to beat his or her own best score. So in broad terms, a game requires a win condition .

Once a win condition is declared, it’s natural to add obstacles that block players from making the win condition true. In some games, the obstacles are other players or a computer playing the part of other players. In other games, the obstacles are forces of nature, physics, or time itself.

Since most games are intended to be played more than once, the obstacles also must change from play to play. Games that don’t change are predictable and eventually cease to challenge the player, which is usually considered the thing that makes games fun.

In fact, if you think about the most enduring games, there are ones that are never the same, like chess, poker, and Dungeons & Dragons, and those that have had their challenges completely redefined, as speed runners have done for Super Mario Bros. and other relatively stagnate games.

You already learned about randomness in the previous two games you made, so creating obstacles that change with each play-through is familiar to you.

The next game that you program in this book is a fantasy card game inspired by games like Magic: The Gathering, Hearthstone, Pathfinder Adventure Card Game, and other trading card games. It will teach you the concepts necessary for all kinds of games, including collision detection, saved game states, graphics, and more. But first, the game must be designed—keeping the game theory principles that you just learned in mind.

Experimental Design

Step away from your Raspberry Pi for this section. If you have a deck of playing cards, you can use that during this exercise; otherwise, find some blank index cards or a few sheets of paper cut down to approximate playing-card size.

Tip

At minimum, a game designer’s toolkit should contain a deck of playing cards and some dice. Neither are items that you will necessarily use in your final version, but they both provide important templates for common game elements; the cards are quick and easy representations of different game elements, and dice produce randomness.

You’re going to invent a new game that modernizes the game that you just programmed, Blackjack. Although the initial design uses a standard deck of cards as a tool, ultimately, you will style the game as a battle scenario, so the game’s name is Battlejack.

There will be several iterations of this new game, and while this book proscribes much of the game to you, you are encouraged to add your own variations along the way. There are no right or wrong answers here. Any idea is worth trying. And if something breaks the game, then you can adapt it or throw it out as needed.

Iteration One

The goal in Blackjack is to be the player with cards adding up to 21, so the goal of Battlejack is the same, only in Battlejack, it’s the dealer trying to get to 21 while the player attempts to prevent it. The player may cancel out a card that the dealer attempts to use in the journey to 21 with a card of an equal or greater number. For example, if the dealer puts down a 5 of clubs, the player can “kill” that card with a 5 of hearts or greater.

Each player takes a suit: the dealer is clubs, and the player is hearts. The player starts with a hand of three cards. On the player’s turn, one action may be taken: either a card may be drawn from the deck, or a card may be played against the dealer. On the dealer’s turn, a card from the deck is revealed and placed on the table. If the card is a club, then it counts toward the dealer’s goal of 21. If it is a heart, it is discarded.

- 1.

Player: draws initial hand: 2♣, 3♣, 5♣.

- 2.

Dealer: 9♣. Total score is now 9.

- 3.

Player: draws Ace♣.

- 4.

Dealer: draws a 3♥, which is discarded.

- 5.

Player: draws 7♥.

- 6.

Dealer: draws 10♣. Total score is now 19.

- 7.

Player: draws Ace♥.

- 8.

Dealer: draws 8♣. Total score is now 27. Game over.

Regardless of how your own play test went, you probably see some problems with the game’s current state. The central mechanic of canceling out a card with a more powerful one never even had a chance to be used, so that’s a clear indication that something is amiss. The player’s initial hand consisted entirely of cards from the dealer’s suit, which didn’t make for a very empowering start. And finally, the likelihood of the dealer reaching exactly 21 is extremely low. In Blackjack, a game can end without anyone reaching 21 because the closest one wins; but in this game, only one side is trying to reach 21, leaving no basis for comparison.

Before proceeding to the next section, take a moment to modify some of the rules and play another hand of Battlejack to see how your changes affect the game.

Iteration Two

Instead of limiting the total deck to just two suits, use all four available suits. The player uses all red cards and the dealer uses all black cards.

The player and the dealer get separate decks, such that the player always draws from a red deck, and the dealer always draws from a black deck.

The first option adds variety, but it doesn’t actually change game play. The second option helps, but it alienates the two players from one another. Each player has a unique deck, both players know exactly what one another’s deck contains, and it more or less turns into a matching game or a reverse game of Go Fish.

Another serious problem with the game is that there’s actually no win condition for the player. The dealer wins by reaching 21. Since the probability of the dealer hitting exactly 21 is so low, you might loosen the constraints and declare the winner at 21 or more, but there’s still no way for the player to win until the dealer runs out of cards. In effect, that does emulate a survival game, so maybe this is a path you want to explore. You could design some cards with common survival themes, such that what is now the black deck consists of various zombies and related threats, and what is now the red deck contains the usual anti-zombie measures.

But even with a cool survival game theme, the game is still very much limited to action and reaction. The game does have some randomness, because the decks are shuffled, but interestingly, the knowledge of what each deck contains lessens the effectiveness of the randomness. Even though the player doesn’t know the order of the cards in the dealer’s deck, the player knows exactly what it contains. When deciding which cards to “spend” to kill a black card, the player can budget using their knowledge of the enemy deck. And worse still, sometimes the order of the cards creates an unbeatable game for the player, so the player has no sense of control over the game, and the stakes are always exactly the same.

- 1.

Split a standard deck of cards into a red deck and a black deck. Place one Joker in each deck.

- 2.

Take six black cards from the black deck and shuffle them into the red deck. These are, effectively, penalties that add unpredictable randomness in the player’s deck.

- 3.

The player draws three cards at the start of the game.

- 4.

On the dealer’s turn, one card from the dealer’s deck is drawn and placed face up on the table. This is the dealer’s “stash.” When a dealer’s stash adds up to 21 or more, the dealer wins.

If the player has a black card in their hand, then the dealer compels that card from the player’s hand into the dealer’s stash.

- 5.

On the player’s turn, the player draws one card from the player deck. There is no hand limit. If a black card is drawn, the player must hold it; it cannot be played or discarded.

The player may then either “stash” a card by placing one card face up in front of them. When a player’s stash reaches 21 or more, the player wins.

Alternatively, a player may “attack” the dealer by eliminating one card in the dealer’s stash. To eliminate a card in the dealer’s stash, the player must sacrifice one or more cards that add up to the face value of the dealer’s card. Jacks, Kings, and Queens all count as 10, and Aces as 1.

Only one card may be eliminated per turn.

At the end of the player’s turn, they draw enough cards to bring their hand back to three.

- 6.

If a Joker is drawn, it destroys all cards in the dealer’s stash.

A few play tests reveal that the game is in much better shape. Even if you can’t express why, you probably find that the game feels better. It feels better because the choices and calculations that the player has to make are now subjective. The player has no way of knowing which six cards from the black deck are in their own deck, so there’s true randomness in the decks at play. There are moments of surprise when a black card is drawn. And each player’s strategy is inherently different: the dealer uses brute force, marching heedlessly onward toward 21, while the player is forced to choose on each turn whether to fight or bolster their own stash. Sometimes, a player has the perfect hand to achieve 21 but needs two turns to stash, and so must gamble that the dealer’s stash, hovering though it may be at 17, won’t reach 21 on the dealer’s next turn.

In other words, there’s some skill, there’s risk, and there are some good turns of luck and some bad turns of luck. And every game is different.

Iteration Three

The game is functional now, and fun too. For the third iteration, try to think abstractly about the game. It has been designed with a standard set of playing cards, but think about your favorite genre and imagine how that might be applied to this game. Instead of just playing by numbers, the player could take the role of a barbarian chieftain battling an onslaught of orcs, or a doctor fighting the spread of a global pandemic, or a starbase captain deploying star fighters against an invading empire.

There may also be an opportunity to add more resource variety. Right now, all cards drawn by the player are cards that get stashed or played, and they are all basically the same. For a few play tests, use all red Jacks, Kings, and Queens as powerup cards: they don’t count as 10, but as a +1, +2, and +3, respectively. In this version of the game, the player can beat a 9 in the dealer’s stash with a 6 and a +3 Queen powerup, or a 4 with a 2 and a +2 powerup, and so on. This could potentially cause a balance problem, because now the dealer has six cards worth 10 points that the player doesn’t have, but it adds flexibility to play, so it may be worth the imbalance. Try it out and see what you think.

Try out other changes of your own design, too. Some changes will break the game, making it too easy or impossible to win, but other changes will make the game uniquely yours.

Pseudo Code for Battlejack

Once you’re happy with a game concept, it’s time to write what’s called pseudo code. Pseudo code is an informal but structured method of planning out a program without worrying about syntax and other details. It’s purely an exercise in logic and planning. Pseudo code doesn’t have to be right, it can be changed later, but it serves as a good guide for you when you sit down at a blank screen to start writing code.

At just 20 lines , this is obviously a very simplified picture of what the game requires, but it’s a good “big picture” view of what is needed. Having it as a guide will help you stay focused when it comes time to write the actual code.

Documentation

It’s just as useful for you as a programmer, and even more useful for your players, if you document your game before you even begin writing code. In big companies, this step is typically done by the UX (user experience) team. They literally draw out what a program is intended to look like, where buttons and menus appear, and what each button or widget does. This is helpful to you while coding because you know where to put your interface elements, and it’s good for your users because you can usually repurpose the design specs as user-facing documentation explaining how to play the game.

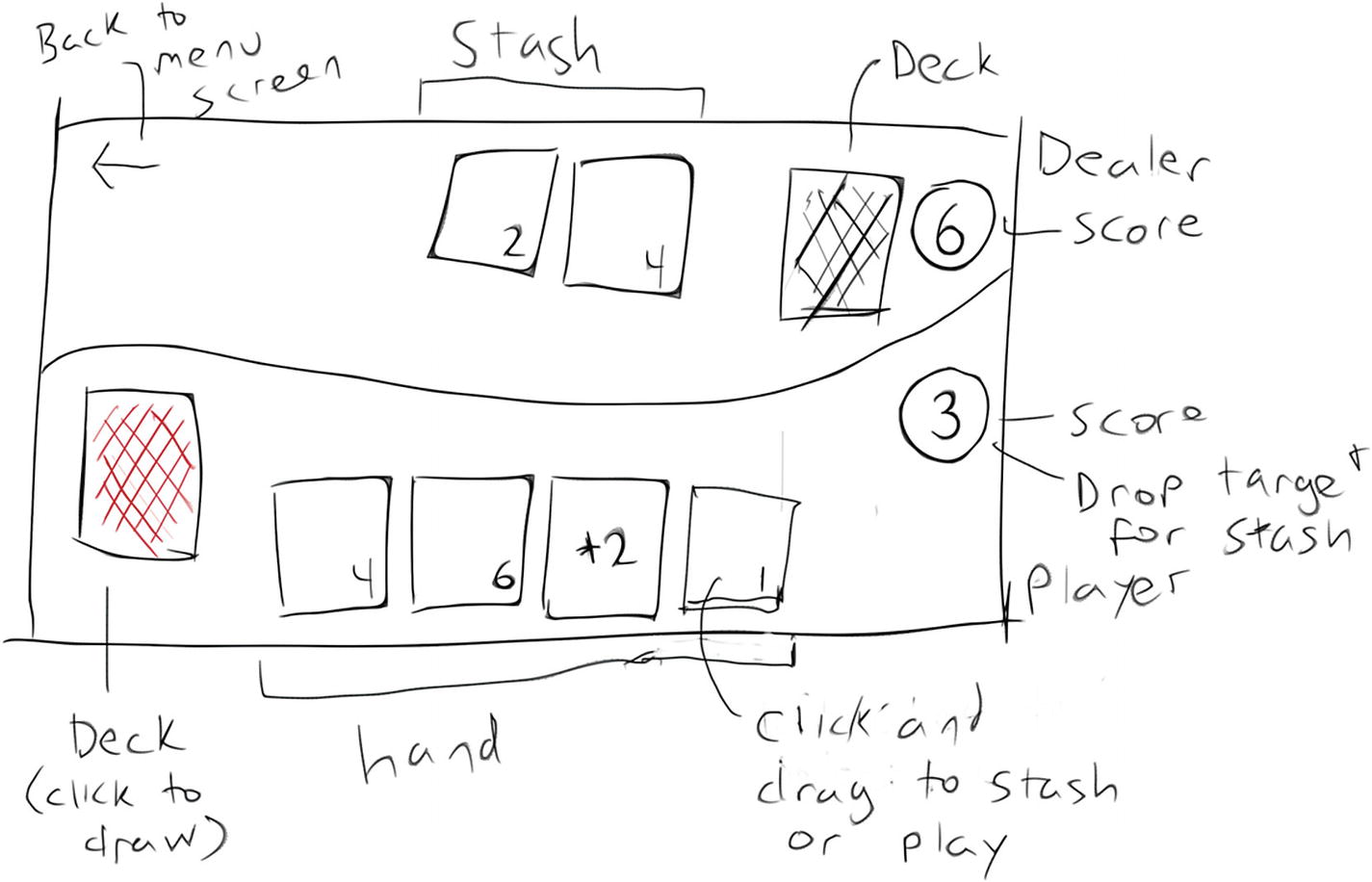

Figure 4-1 shows a sample spec for Battlejack.

When the game launches, the player is greeted with a menu screen that allows the user to resume a saved game or start a new game, adjust settings for full-screen or windowed display, and determine whether or not tutorial tips are displayed during play.

During game play, the user clicks their own deck to draw a card. During their turn, the player clicks and drags cards to either the dealer’s stash to cancel out a card in play, or to their own score box to add their card to their own stash. Onscreen prompts alert the player of their choices.

If a player attempts to cancel a dealer card out with a less powerful card (trying to cancel a five-strength card with a three-strength card, for example), nothing happens. The player may add powerups or additional cards to complete the action, or click and drag the card back into their hand to continue.

Design spec for Battlejack

A spec document doesn’t necessarily have to be followed to the letter, but it serves as a guide and a target while coding. Some adjustments might have to be made. Some features might have to be dropped, others added, and still others changed. If you were hired to program to a specification, changes would have to be negotiated to ensure that you’re not cheating your client out of something you assured them you could do. In this case, however, you are your own client, and so this spec document is just a gentle guide and a helpful map of what needs to get coded and what needs to be produced for the game.

In the next chapter, you’ll learn about code libraries, data storage, and deck definition files, which are essential for a feature-rich video game.

Homework

Even high-tech video games can be reduced down to tabletop mechanics. Learning why games are fun to play is an important part of designing good games.

Take a game that you like to play on the computer or console, and mentally deconstruct it. Determine what its game mechanics are. For instance, in Portal, the mechanic is solving intricate puzzles with fantasy portal physics. In Half Life, the mechanic is to shoot enemies while unraveling elements of a detailed story. In the Fallout series, the mechanic is storytelling and exploration.

Try to come up with a card game version of your favorite game. It doesn’t have to be an exact match, but see how close you can get. Incorporate dice as needed.