The dice game in Chapter 2 was created in one file. Small programs, usually called scripts, are often only one file, but the larger an application gets, the less convenient it is to write it all in one monolithic file. After all, most large applications aren’t written by just one developer but a whole team, and only one person can work on a file at a time. Game engines are pieces in a modular system, since the engine is useless to users without a game. Additionally, if you keep your code modular, you might be able to reuse a file from one project in the next project.

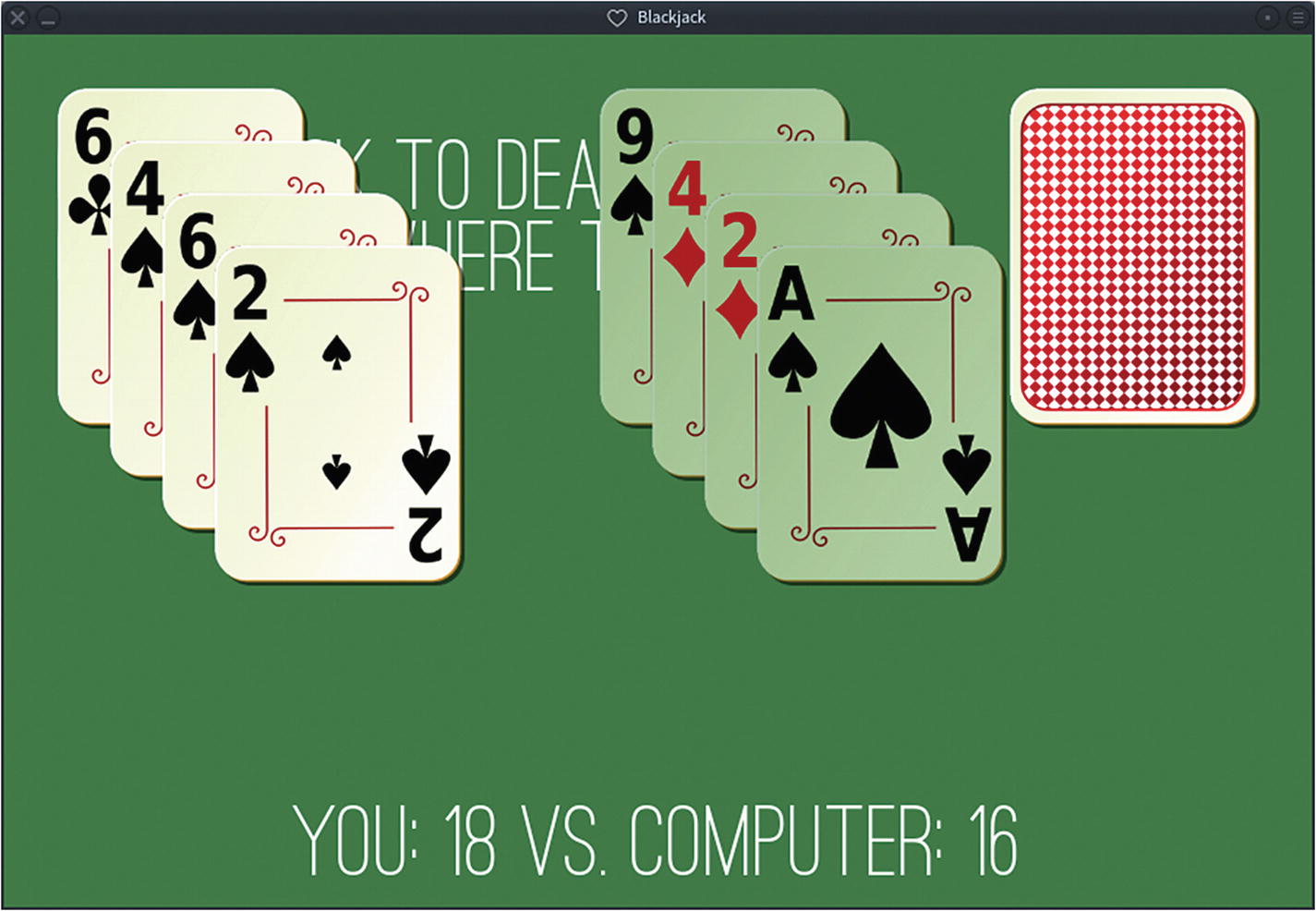

The card game you’re about to make with Lua

Project Directory

There is no rule for how you organize your code, but there is a general convention, especially within the open source software world. You can get a feel for this convention if you browse a few open source projects online, and you’ve already implemented some principles as you created your dice game.

That takes care of the obvious folders, but there are also a few files that most people expect to find in a software source directory: README and LICENSE.

The LICENSE file tells anyone looking at your source how they may use your code. There are several varieties of open source licenses, listed in detail at gnu.org/licenses/license-list.html.

As the author of the code, I license the program that you are about to copy and learn from under the GNU Public License version 3 (GPLv3). This grants you permission to redistribute, or even sell, and modify it as you wish, as long as you give everyone else permission to do the same. As open source licenses go, this is a common and sensible agreement: you get to do whatever you want to do with the code as long as you let the next person in line do whatever they want.

That takes care of all the bureaucracy and preparation. Now you need to build a virtual card deck.

Classes and Objects

In the dice game, you had two dice “objects” to code. An object in code is a little bit like a mold in real life: the code defines the basic properties of an object, and usually allows customization, as needed. Object-oriented programming (OOP) is the prevailing means of developing software today, so learning to structure your code into objects is important, and by the end of this book, it’s something you’ll do naturally.

For the dice game, you coded each object separately because there were only two die. This time, you are writing a game involving 52 playing cards, so it doesn’t make sense to code each card separately, just as programmers in major game studios don’t manually code every single enemy you have to fight.

When a program requires lots of different objects with basically the same properties, you can use a class. A class is a snippet of code—usually stored in its own unique file—that your main program uses as a template when building an object in your game. This template not only generates an object for your program, it creates a whole infrastructure with variables and other properties unique to that one instance of the object.

Open Geany and create a new, empty file called card.lua . Technically, Lua doesn’t have classes, but it has tables that can be treated like classes. You’ve already created a table for the dice game, so some of this process may seem familiar to you.

Next, create a function called Card.init (the word init is a common programming term meaning initialize or create). For the dice game, you used functions, such as math.random()and love.load() , included in Lua. This time, you are creating your own function.

In this Card.init function , you establish a local variable called self, which uses a special Lua extension called a metatable, as a kind of container for all the properties about that individual instance of a card. A card’s self variable ensures that each card can keep track of whatever makes it unique.

Since each card created gets unique memory out of your computer’s RAM, each one can track properties such as its suit and value. At the end of the creation process, the Card class alerts your main program of its self data, which you can use in your game.

Save the card.lua file and create a new one called main.lua .

This prompts Lua to search the current directory for a library called card.

To create a card using your function, create a new variable and invoke your function, along with two arguments: one for the suit you want your new card to belong to and one for the face value.

Your class produces, upon request, a card “object.” It’s not a physical object, but it’s a virtual playing card with unique properties from the next. Each “object” is produced by filling a variable with a table containing preset variables that you have defined as an inherent attribute of the object. This is an important principle in modern programming because it lets you make templates for constructs in your program that you want to use over and over again.

Randomized Cards

Now that you have a card-producing Lua library, you must use it in a way that is useful in a game of Blackjack.

Blackjack is a simple game of chance and calculated risk. Each player draws a card and adds it to their hand until they are as close to 21 as possible. When both players are satisfied, they compare their hands. The player closest to 21 wins. If a player goes over 21, they lose.

It’s important for Blackjack to be random. Your dice game also used random numbers, so you know that when producing a random number, you constrain Lua with a minimum and a maximum value. But Lua has no knowledge of playing cards, so you can’t just tell it to randomly pick a suit or a face card. However, you can create a table listing each suit and a table listing each possible face value and then tell the computer to pick from those numbered lists.

This sets up a LÖVE window, an empty table to represent the player and their computer opponent, and a basic skeleton for your code.

Since you already know how to get a random value from Lua, you can use your card generator library to produce a card object with a random suit and value.

This function creates a temporary variable called c and gives it a random number between 1 and 4. Then it creates another temporary variable called s and uses c to select one item from the suits table. It does basically the same thing with the values table for a variable called v, and then it calls your card generator library to create a new card with whatever random results are in the s and v variables.

At the end of the function, there is a return statement. This means that after the function runs, it outputs information, which can be assigned to a variable.

Like your dice game, user interaction is a simple mouse click. The mousereleased function of LÖVE sends a variety of information, including where on the screen the mouse was released, and which physical button on the mouse was released. You don’t have to use the information, but it lets you be precise about what input you want your game to respond to.

In this code, the left mouse button triggers the creation of a new card object by creating a variable called var, which is assigned the output of your card generator function. Your card generator function, of course, calls your card library so that var contains a table detailing the suit and value of a card.

Once the card has been created, the var variable containing the card is copied into the player’s hand. When you add an item to a table, you must add it to the end of the list; so to specify where in the table the new card goes, you use the #hand shorthand to get the current length of the table plus 1.

After the card has been added to the player’s hand, tally up the current total score for the player. The value of each card is contained in the card’s table. The current card is still going by the name var, so you add whatever is contained in total to var.value.

There are still no graphics being drawn, so add some text to help you see that your application is working up to this point. You can use whatever font you want, but this sample code uses Ostrich from TheLeagueofMoveableType.com.

Note

As a courtesy to the person who created the font you use, credit the font in your README file.

The problem lies in how the cards are scored. Some cards are listed as numbers, but others are face cards. Lua can’t very well add “Jack” to the total score, so it crashes.

The obvious solution to this problem is to change the King, Queen, and Jack values to 10, and the Ace value to 1. However, if the King and Queen and Jack are all changed to 10, there’s no way to tell them apart when randomly choosing which to display.

Launch your game again. You can keep drawing cards endlessly. No bugs!

Graphics

A game of cards using names and numbers is effective, but not pretty. To make this a real people-pleasing game, you need graphics. Then again, 52 cards are a lot of graphics to come up with. Luckily, a few people on OpenClipArt.org have already done the work for you, posting them as free assets with no recompense required. Download the cards from this book’s code repository, or make your own.

Note

While OpenClipArt.org requires nothing in return, it’s considered good form to credit those who have helped you make a project. For this reason, you should open your README file in Geany and thank the OpenClipArt.org artists whose work you are using: mariotomo, nicubunu, and notklaatu.

Place the .png files in the img folder of your code directory. They must be named in the Value-of-suit.png format; for example, 2-of-hearts.png.

Now whenever a new card is created, the card object is assigned a graphic with a filename corresponding to its randomly selected suit and name.

Since your game will draw multiple cards on the screen, it’s helpful to have a variable representing the size of a virtual card. In the preceding code, the slot variable is assigned to the results of the getWidth function performed on the playback card multiplied by the current scale. This allows you to use slot to represent any space occupied by a card. In the real world, you would use inches or centimeters, but those don’t mean much on screens, so for this game, you use slot instead.

In addition to creating the deck and a variable for one unit of card measure, this code sample sets the background of the game window to green.

Launch your project. The deck should appear in the upper-right corner; the instructions are on the right. If you click the green tabletop, nothing happens, but if you click the card deck, you are dealt a new card. This happens until the cards flow right off the screen.

Competition

Blackjack can be a solitaire game in real life, but people playing competitive computer games usually expect a definitive win and lose condition. That means you need to program an opponent.

According to the Internet, the prevailing opinion on Blackjack is to hold at around 17. This being the only real “strategy” (such as it is), programming an AI is a simple conditional: if the computer’s hand is 17 or higher, then the computer must hold. To make the game a little more exciting, you can make the computer more reckless than popular strategy dictates by setting its hold tolerance to 16 or 15.

Notice that the computer takes its turn before the player. This means that whether or not the player is drawing a card or holding, the computer still has the opportunity to take a turn.

Just because the computer chooses to hold doesn’t necessarily mean that the player is going to hold, so a hold flag can only be set by the player, which is currently the else statement in the player’s mousereleased action.

Once a player chooses to hold, the game is over. At that point, you could program a pop-up box to ask if the player wants to play another hand. However, when designing an interface, it’s better to default to success as often as possible. A player knows how to exit the game, so there’s no reason to bother them with prompts. That means if the player has decided to hold, the game should just start over. For that to happen, you need a reset function.

A reset is called when two things are true: the player has decided to hold, but the player has clicked somewhere on the screen. However, since clicking the table is also a sign to hold, some safeguards need to be introduced to prevent clicking the table from both starting a new game and signaling the end of that new game. A simple way to prevent a premature endgame signal is to ensure that the player has at least one card on the table before flagging a hold or a reset.

Launch the game to verify that it’s working and to see what’s missing.

Winning

All that’s left now is to detect and declare a winner. Sometimes, it’s easier to detect failure than success, so the first thing you can do is add a watcher function to check whether or not the player has exceeded 21. If ever a player’s hand exceeds 21, then there’s no way for the player to win, so the hold flag can be set immediately to bring the game to an end.

The Lua tonumber method is a safeguard to ensure that the content of total is definitely treated as a number and not a string. It’s not very likely that LÖVE would get confused about that, or that total would contain a string, but since it’s a math operation, it doesn’t hurt to ensure that both sides of the equation are numbers.

Their hand is less than or equal to 21

But also greater than the computer’s hand

If the computer’s hand is greater than 21

It’s a tie if both hands are equal

It’s a bust if both hands are greater than 21

There can be no win condition unless a hold has either been chosen or imposed, so it’s safe to only call the winner function if hold is true. You can check this in the love.draw() section of your code, using this as an opportunity to display on screen a running total of each hand until a winner is announced.

The game is complete. Launch it to try it out.

Open a desktop window to your blackjack folder and double-click blackjack.love. Your game launches just like any normal application. You can send this file to anyone you want to, and as long as they install LÖVE, they can play your game.

Homework

The computer only gets one final turn if the player holds. Introduce a second hold variable, such as aihold, to detect when the computer has decided to hold, regardless of what the player has done. Calculate the winner only after both the computer and the player have decided to hold.

Ostensibly, your deck of cards should only have one of each card in it, but in the current state of the code, there is a chance that the same card could be generated twice. Can you come up with a way to ensure that once a card has been drawn, there is no chance of it being drawn again until the next round? Hint: the answer may involve another set of tables.

The Planter application at https://gitlab.com/planter/planter allows you to create project directory templates so that you don’t have to manually set up a project’s skeleton every time you start something new. Try to install it, and then try to use it.