10

PHP

PHP’s popularity exploded during the early phases of the late-90s web boom and remains wildly popular today. One reason for this popularity is that even non-engineers can start using its basic features with very little preparation. Yet, despite this approachability, PHP also provides a vast cornucopia of advanced features and functions sure to please the seasoned engineer. PHP supports regular expressions, of course, and does so with no less than three separate, unrelated regex engines.

The three regex engines in PHP are the “preg,” “ereg,” and “mb_ereg” engines. This book covers the preg suite of functions. It’s backed by an NFA engine that is generally superior, in both features and speed, to the other two. (“preg” is normally pronounced “p-reg.”)

Reliance on Early Chapters Before looking at what’s in this chapter, it’s important to emphasize that it relies heavily on the base material in Chapters 1 through 6. Readers interested only in PHP may be inclined to start their reading with this chapter, but I want to encourage them not to miss the benefits of the preface (in particular, the typographical conventions) and the earlier chapters: Chapters 1, 2, and 3 introduce basic concepts, features, and techniques involved with regular expressions, while Chapters 4, 5, and 6 offer important keys to regex understanding that directly apply to PHP’s preg engine. Among the important concepts covered in earlier chapters are the base mechanics of how an NFA regex engine goes about attempting a match, greediness, backtracking, and efficiency concerns.

Along those lines, let me emphasize that despite convenient tables such as the one in this chapter on page 441, or, say, ones in earlier chapters such as those on pages 114 and 123, this book’s foremost intention is not to be a reference, but a detailed instruction on how to master regular expressions.

This chapter starts with a few words on the history of the preg engine, followed by a look at the regex flavor it provides. Later sections cover in detail the preg function interface, followed by preg-specific efficiency concerns, and finally, extended examples.

preg Background and History The “preg” name comes from the prefix used with all of the interface function names, and stands for “Perl Regular Expressions.” This engine was added by Andrei Zmievski, who was frustrated with the limitations of the then-current standard ereg suite. (“ereg” stands for “extended regular expressions,” a POSIX-compliant package that is “extended” compared to the most simple regex flavors, but is considered fairly minimalistic by today’s standards.)

Andrei created the preg suite by writing an interface to PCRE (“Perl Compatible Regular Expressions”), an excellent NFA-based regular-expression library that closely mimics the regular-expression syntax and semantics of Perl, and provides exactly the power Andrei sought.

Before finding PCRE, Andrei had first looked at the Perl source code to see whether it might be borrowed for use in PHP. He was undoubtedly not the first to examine Perl’s regex source code, nor the first to come to the quick realization that it is not for the faint of heart. As powerful and fast as Perl regexes are for the user, the source code itself had been worked and reworked by many people over the years and had become something rather beyond human understanding.

Luckily, Philip Hazel at the University of Cambridge in England had been befuddled by Perl’s regex source code as well, so to fulfil his own needs, he created the PCRE library (introduced on page 91). Philip had the luxury of starting from scratch with a known semantics to mimic, and so it was with great relief that several years later Andrei found a well-written, well-documented, high-performance library he could tie in to PHP.

Following Perl’s changes over the years, PCRE has itself evolved, and with it, PHP. This book covers PHP Versions 4.4.3 and 5.1.4, both of which incorporate PCRE Version 6.6.†

In case you are not familiar with PHP’s version-numbering scheme, note that both the 4.x and 5.x tracks are maintained in parallel, with the 5.x versions being a much-expanded rewrite. Because both are maintained and released independently, it’s possible for a 5.x version to contain an older version of PCRE than a more-modern 4.x version.

PHP’s Regex Flavor

Table 10-1: Overview of PHP’s preg Regular-Expression Flavor

Character Shorthands |

|

|

|

Character Classes and Class-Like Constructs |

|

Classes: |

|

Any character except newline: dot (with s pattern modifier, any character at all) |

|

|

Unicode combining sequence: |

|

Class shorthands: |

|

Unicode properties and scripts: |

Exactly one byte (can be dangerous): |

|

Anchors and Other Zero-Width Tests |

|

Start of line/string: |

|

End of line/string: |

|

Start of current match: |

|

Word boundary: |

|

Lookaround: |

|

Comments and Mode Modifiers |

|

Mode modifiers: |

|

Mode-modified spans: |

|

Comments: |

|

Grouping, Capturing, Conditional, and Control |

|

Capturing parentheses: |

|

Named capture: |

|

Grouping-only parentheses: |

|

Atomic grouping: |

|

Alternation: |

|

Recursion: |

|

Conditional: |

|

Greedy quantifiers: |

|

Lazy quantifiers: |

|

Possessive quantifiers: |

|

|

Literal (non-metacharacter) span: |

(c) – may also be used within a character class (u) – only in conjunction with the u pattern modifier (This table also serves to describe PCRE, the regex library behind PHP’s preg functions |

|

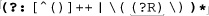

Table 10-1 on the previous page summarizes the preg engine’s regex flavor. The following notes supplement the table:

\b is a character shorthand for backspace only within a character class. Outside of a character class, \b matches a word boundary ( 133).

133).

Octal escapes are limited to two- and three-digit 8-bit values. The special one-digit ⌈\0⌋ sequence matches a NUL byte.

⌈\xhex⌋ allows one- and two-digit hexadecimal values, while ⌈\x{hex}⌋ allows any number of digits. Note, however, that values greater than \X{FF} are valid only with the u pattern modifier ( 447). Without the u pattern modifier, values larger than

447). Without the u pattern modifier, values larger than \x{FF} result in an invalid-regex error.

Even in UTF-8 mode (via the u pattern modifier), word boundaries and class shorthands such as ⌈

Even in UTF-8 mode (via the u pattern modifier), word boundaries and class shorthands such as ⌈\w⌋ work only with ASCII characters. If you need to consider the full breadth of Unicode characters, consider using ⌈\pL⌋ ( 121) instead of ⌈

121) instead of ⌈\w⌋, using ⌈\pN⌋ instead of ⌈\d⌋, and ⌈\pZ⌋ instead of ⌈\s⌋.

Unicode support is as of Unicode Version 4.1.0.

Unicode support is as of Unicode Version 4.1.0.

Unicode scripts ( 122) are supported without any kind of ‘

122) are supported without any kind of ‘Is’ or ‘In’ prefix, as with ⌈\p{Cyrillic}⌋.

One- and two-letter Unicode properties are supported, such as ⌈\p{Lu}⌋, ⌈\p{L}⌋, and the ⌈\pL⌋ shorthand for one-letter property names ( 121). Long names such as ⌈

121). Long names such as ⌈\p{Letter}⌋ are not supported.

The special ⌈\p{L&}⌋ ( 121) is also supported, as is ⌈

121) is also supported, as is ⌈\p{Any}⌋ (which matches any character).

By default, preg-suite regular expressions are byte oriented, and as such, ⌈

By default, preg-suite regular expressions are byte oriented, and as such, ⌈\C⌋ defaults to being the same as ⌈(?s:.)⌋, an s-modified dot. However, with the u modifier, preg-suite regular expressions become UTF-8 oriented, which means that a character can be composed of up to six bytes. Even so, \C still matches only a single byte. See the caution on page 120.

⌈

⌈\z⌋ and ⌈\Z⌋ can both match at the very end of the subject string, while ⌈\Z⌋ can also match at a final-character newline.

The meaning of ⌈$⌋ depends on the m and D pattern modifiers ( 446) as follows: with neither pattern modifier, ⌈

446) as follows: with neither pattern modifier, ⌈$⌋ matches as ⌈\Z⌋ (before string-ending newline, or at the end of the string); with the m pattern modifier, it can also match before an embedded newline; with the D pattern modifier, it matches as ⌈\z⌋ (only at the end of the string). If both the m and D pattern modifiers are used, D is ignored.

Lookbehind is limited to subexpressions that match a fixed length of text, except that top-level alternatives of different fixed lengths are allowed (

Lookbehind is limited to subexpressions that match a fixed length of text, except that top-level alternatives of different fixed lengths are allowed ( 133).

133).

The x pattern modifier (free spacing and comments) recognizes only ASCII whitespace, and does not recognize other whitespace found in Unicode.

The x pattern modifier (free spacing and comments) recognizes only ASCII whitespace, and does not recognize other whitespace found in Unicode.

The Preg Function Interface

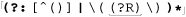

PHP’s interface to its regex engine is purely procedural ( 95), provided by the six functions shown at the top of Table 10-2. For reference, the table also shows four useful functions that are presented later in this chapter.

95), provided by the six functions shown at the top of Table 10-2. For reference, the table also shows four useful functions that are presented later in this chapter.

Table 10-2: Overview of PHP’s Preg Functions

Function |

Use |

|

Check whether regex can match in a string, and pluck data from a string |

|

Pluck data from a string |

|

Replace matched text within a copy of a string |

|

Call a function for each match of regex within a string |

|

Partition a string into an array of substrings |

|

Cull elements from an array that do/don’t match regex |

|

Escape regex metacharacters in a string |

The following functions, developed in this chapter, are included here for easy reference. |

|

|

Non-participatory-parens aware version of |

|

Create a preg pattern string from a regex string |

|

Check a preg pattern string for syntax errors |

|

Check a regex string for syntax errors |

What each function actually does is greatly influenced by the type and number of arguments provided, the function flags, and the pattern modifiers used with the regex. Before looking at all the details, let’s see a few examples to get a feel for how regexes look and how they are handled in PHP:

/* Check whether HTML tag is a <table> tag */

if (preg_match('/^<table\b/i', $tag))

print "tag is a table tag\n";

---------------------------

/* Check whether text is an integer */

if (preg_match('/^-?\d+$/', $user_input))

print "user input is an integer\n";

---------------------------

/* Pluck HTML title from a string */

if (preg_match('{<title>(.*?)</title>}si', $html, $matches))

print "page title: $matches[1]\n";

---------------------------

/* Treat numbers in string as Fahrenheit values and replace with Celsius values */

$metric = preg_replace('/(-?\d+(?:\.\d+)?)/e', /* pattern */

'floor(($1-32)*5/9 + 0.5)', /* replacement code */

$string);

---------------------------

/* Create an array of values from a string filled with simple comma-separated values */

$values_array = preg_split('!\s*,\s*!', $comma_separated_values);

The last example, when given a string such as ‘Larry, •Curly, •Moe’, produces an array with three elements: the strings ‘Larry’, ‘Curly’, and ‘Moe’.

“Pattern” Arguments

The first argument to any of the preg functions is a pattern argument, which is the regex wrapped by a pair of delimiters, possibly followed by pattern modifiers. In the first example above, the pattern argument is '/<table\b/i', which is the regex ⌈<table\b⌋ wrapped by a pair of slashes (the delimiters), followed by the i (case-insensitive match) pattern modifier.

PHP single-quoted strings

Because of a regex’s propensity to include backslashes, it’s most convenient to use PHP’s single-quoted strings when providing these pattern arguments as string literals. PHP’s string literals are also covered in Chapter 3 ( 103), but in short, you don’t need to add many extra escapes to a regular expression when rendering it within a single-quoted string literal. PHP single-quoted strings have only two string metasequences, ‘

103), but in short, you don’t need to add many extra escapes to a regular expression when rendering it within a single-quoted string literal. PHP single-quoted strings have only two string metasequences, ‘\'’ and ‘\\’, which include a single quote and a backslash into the string’s value, respectively.

One common exception requiring extra escapes is when you want ⌈\\⌋ within the regex, which matches a single backslash character. Within a single-quoted string literal, each ⌈\⌋ requires \\, so ⌈\\⌋ requires \\\\. All this to match one backslash. Phew!

(You can see an extreme example of this kind of backslash-itis on page 473.)

As a concrete example, consider a regex to match a Windows disk’s root path, such as ‘C:\’. An expression for that is ⌈^[A-Z]:\\$⌋, which — when included within a single-quoted string literal—appears as '^[A-Z]:\\\\$'.

In a Chapter 5 example on page 190, we saw that ⌈^.*\\⌋ required a pattern argument string of '/^.*\\\/', with three backslashes. With that in mind, I find the following examples to be illustrative:

print '/^.*\/'; prints: /^.*\/

print '/^.*\\/'; prints: /^.*\/

print '/^.*\\\/'; prints: /^.*\\/

print '/^.*\\\\/'; prints: /^.*\\/

The first two examples yield the same result through different means. In the first, the ‘\/’ sequence at the end is not special to a single-quoted string literal, so the sequence appears verbatim in the string’s value. In the second example, the ‘\\’ sequence is special to the string literal, yielding a single ‘\’ in the string’s value. This, when combined with the character that follows (the slash), yields the same ‘\/’ in the value as in the first example. The same logic applies to why the third and fourth examples yield the same result.

You may use PHP double-quoted string literals, of course, but they’re much less convenient. They support a fair number of string metasequences, all of which must be coded around when trying to render a regex as a string literal.

Delimiters

The preg engine requires delimiters around the regex because the designers wanted to provide a more Perl-like appearance, especially with respect to pattern modifiers. Some programmers may find it hard to justify the hassle of required delimiters compared to providing pattern modifiers in other ways, but for better or worse, this is the way it is. (For one example of “worse,” see the sidebar on page 448.)

It’s common to use slashes as the delimiters in most cases, but you may use any non-alphanumeric, non-whitespace ASCII character except a backslash. A pair of slashes are most common, but pairs of ‘!’ and ‘#’ are used fairly often as well.

If the first delimiter is one of the “opening” punctuations:

{ ( < [

the closing delimiter becomes the appropriate matching closing punctuation:

} ) > ]

When using one of these “paired” delimiters, the delimiters may be nested, so it’s actually possible to use something like '((\d+))' as the pattern-argument string. In this example, the outer parentheses are the pattern-argument delimiters, and the inner parentheses are part of the regular expression those delimiters enclose. In the interest of clarity, though, I’d avoid relying on this and use the plain and simple '/(\d+)/' instead.

Delimiters may be escaped within the regex part of the pattern-argument string, so something like '/<B>(.*?)<\/B>/i' is allowed, although again, a different delimiter may appear less cluttered, as with '!<B>(.*?)</B>!i' which uses ‘!···!’ as the delimiters, or '{<B>(.*?)</B>}i', which uses ‘{···}’.

Pattern modifiers

A variety of mode modifiers (called pattern modifiers in the PHP vernacular) may be placed after the closing delimiter, or in some cases, within the regex itself, to modify certain aspects of a pattern’s use. We’ve seen the case-insensitive i pattern modifier in some of the examples so far. Here’s a summary of all pattern modifiers allowed:

Modifier |

Inline |

Description |

|

i |

⌈ |

Ignore letter case during match |

|

m |

⌈ |

Enhanced line anchor match mode |

|

s |

⌈ |

Dot-matches-all match mode |

|

x |

⌈ |

Free-spacing and comments regex mode |

|

u |

|

Consider regex and target strings as encoded in UTF-8 |

|

X |

⌈ |

Enable PCRE “extra stuff” |

|

e |

|

Execute replacement as PHP code ( |

|

S |

|

Invoke PCRE’s “study” optimization attempt |

|

The following are rarely used |

|||

U |

⌈ |

Swap greediness of ⌈ |

|

A |

|

Anchor entire match to the attempt’s initial starting position |

|

D |

|

⌈ (Ignored if the m pattern modifier is used.) |

|

Pattern modifiers within the regex

When embedded within a regex, pattern modifiers can appear standalone to turn a feature on or off (such as ⌈(?i)⌋ to turn on case-insensitive matching, and ⌈(?-i)⌋ to turn it off  135). Used this way, they remain in effect until the end of the enclosing set of parentheses, if any, or otherwise, until the end of the regular expression.

135). Used this way, they remain in effect until the end of the enclosing set of parentheses, if any, or otherwise, until the end of the regular expression.

They can also be used as mode-modified spans ( 135), such as ⌈

135), such as ⌈(?i:···)⌋ to turn on case-insensitive matching for the duration of the span, or ⌈(?-sm:···)⌋ to turn off s and m modes for the duration of the span.

Mode modifiers outside the regex

Modifiers can be combined, in any order, after the final delimiter, as with this example’s ‘si’, which enables both case-insensitive and dot-matches-all modes:

if (preg_match('{<title>(.*?)</title>}si', $html, $captures))

PHP-specific modifiers

The first four pattern modifiers listed in the table are fairly standard and are discussed in Chapter 3 ( 110). The e pattern modifier is used only with

110). The e pattern modifier is used only with preg_replace, and it is covered in that section ( 459).

459).

The u pattern modifier tells the preg regex engine to consider the bytes of the regular expression and subject string to be encoded in UTF-8. The use of this modifier doesn’t change the bytes, but merely how the regex engine considers them. By default (that is, without the u pattern modifier), the preg engine considers data passed to it as being in the current 8-bit locale ( 87). If you know the data is encoded in UTF-8, use this modifier; otherwise, do not. Non-ASCII characters with UTF-8-encoded text are encoded with multiple bytes, and using this u modifier ensures that those multiple bytes are indeed taken as single characters.

87). If you know the data is encoded in UTF-8, use this modifier; otherwise, do not. Non-ASCII characters with UTF-8-encoded text are encoded with multiple bytes, and using this u modifier ensures that those multiple bytes are indeed taken as single characters.

The X pattern modifier turns on PCRE “extra stuff,” which currently has only one effect: to generate an error when a backslash is used in a situation other than as part of a known metasequence. For example, by default, ⌈\k⌋ has no special meaning to PCRE, and it’s treated as ⌈k⌋ (the backslash, not being part of a known metasequence, is ignored). Using the X modifier causes this situation to result in an “unrecognized character follows \” fatal error.

Future versions of PHP may include versions of PCRE that ascribe special meaning to currently unspecial backslash-letter combinations, so in the interest of future compatibility (and general readability), it’s best not to escape letters unless they currently have special meaning. In this regard, the use of the X pattern modifier makes a lot of sense, because it can point out typos or similar mistakes.

The S pattern modifier invokes PCRE’s “study” feature, which pre-analyzes the regular expression, and in some well-defined cases, can result in a substantially faster match attempt. It’s covered in this chapter’s section on efficiency, starting on page 478.

The remaining pattern modifiers are esoteric and rarely used:

- The A pattern modifier anchors the match to where the match attempt is first started, as if the entire regex leads off with ⌈

\G⌋. Using the car analogy from Chapter 4, this is akin to turning off the “bump-along” by the transmission ( 148).

148). - The D pattern modifier effectively turns each ⌈

$⌋ into ⌈\z⌋ ( 112), which means that ⌈

112), which means that ⌈$⌋ matches right at the end of the string as always, but not before a string-ending newline. - The U pattern modifier swaps metacharacter greediness: ⌈

*⌋ is treated as ⌈*?⌋ and vice versa, ⌈+⌋ is treated as ⌈*?⌋ and vice versa, etc. I would guess that the primary effect of this pattern modifier is to create confusion, so I certainly don’t recommend it.

The Preg Functions

This section covers each function in detail, starting with the most basic “does this regex match within this text?” function: preg_match.

preg_match

Usage

preg_match(pattern, subject [, matches [, flags [, offset ]]])

Argument Summary

pattern |

The pattern argument: a regex in delimiters, with optional modifiers ( |

subject |

Target string in which to search. |

matches |

Optional variable to receive match data. |

flags |

Optional flags that influence overall function behavior. There is only one flag allowed, PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE ( |

offset |

Optional zero-based offset into subject at which the match attempt will begin ( |

Return Value

A true value is returned if a match is found, a false value if not.

Discussion

At its simplest,

preg_match($pattern, $subject)

returns true if $pattern can match anywhere within $subject. Here are some simple examples:

if (preg_match('/\.(jpe?g|png|gif|bmp)$/i', $url)) {

/* URL seems to be of an image */

}

------------------------

if (preg_match('{^https?://}', $uri)) {

/* URI is http or https */

}

------------------------

if (preg_match('/\b MSIE \b/x', $_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'])) {

/* Browser is IE */

}

Capturing match data

An optional third argument to preg_match is a variable to receive the resulting information about what matched where. You can use any variable you like, but the name $matches seems to be commonly used. In this book, when I discuss “$matches” outside the context of a specific example, I’m really talking about “whatever variable you put as the third argument to preg_match.”

After a successful match, preg_match returns true and $matches is set as follows:

$matches[0] is the entire text matched by the regex

$matches[1] is the text matched by the first set of capturing parentheses

$matches[2] is the text matched by the second set of capturing parentheses

·

·

·

If you’ve used named captures, corresponding elements are included as well (there’s an example of this in the next section).

Here’s a simple example seen in Chapter 5 ( 191):

191):

/* Given a full path, isolate the filename */

if (preg_match('{ / ([^/]+) $}x', $WholePath, $matches))

$FileName = $matches[1];

It’s safe to use $matches (or whatever variable you use for the captured data) only after preg_match returns a true value. False is returned if matching is not successful, or upon error (bad pattern or function flags, for example). While some errors do leave $matches cleared out to an empty array, some errors actually leave it with whatever value it had before, so you can’t assume that $matches is valid after a call to preg_match simply because it’s not empty.

Here’s a somewhat more involved example with three sets of capturing parentheses:

/* Pluck the protocol, hostname, and port number from a URL */

if (preg_match('{^(https?):// ([^/:]+) (?: :(\d+) )? }x', $url, $matches))

{

$proto = $matches[1];

$host = $matches[2];

$port = $matches[3] ? $matches[3] : ($proto == "http" ? 80 : 443);

print "Protocol: $proto\n";

print "Host :$host\n";

print "Port :$port\n";

}

Trailing “non-participatory” elements stripped

A set of parentheses that doesn’t participate in the final match yields an empty string† in the corresponding $matches element. One caveat is that elements for trailing non-participating captures are not even included in $matches. In the previous example, if the ⌈(\d+)⌋ participated in the match, $matches[3] gets a number. If it didn’t participate, $matches[3] doesn’t even exist in the array.

Named capture

Let’s look at the previous example rewritten using named capture ( 138). It makes the regex a bit longer, but also makes the code more self-documenting:

138). It makes the regex a bit longer, but also makes the code more self-documenting:

/* Pluck the protocol, hostname, and port number from a URL */

if (preg_match('{^(?P<proto> https? )://

(?P<host> [^/:]+ )

(?: : (?P<port> \d+ ))?}x', $url, $matches))

{

$proto = $matches['proto'];

$host = $matches['host'];

$port = $matches['port'] ? $matches['port'] : ($proto == "http" ? 80 : 443);

print "Protocol: $proto\n";

print "Host : $host\n";

print "Port : $port\n";

}

The clarity that named capture brings can obviate the need to copy out of $matches into separate variables. In such a case, it may make sense to use a variable name other than $matches, such as in this rewritten version:

/* Pluck the protocol, hostname, and port number from a URL */

if (preg_match('{^(?P<proto> https? )://

(?P<host> [^/:]+ )

(?: : (?P<port> \d+ ) )? }x', $url, $UrlInfo))

{

if (! $UrlInfo['port'])

$UrlInfo['port'] = ($UrlInfo['proto'] == "http" ? 80 : 443);

echo "Protocol: ", $UrlInfo['proto'], "\n";

echo "Host :",$UrlInfo['host'], "\n";

echo "Port :",$UrlInfo['port'], "\n";

}

When using named capture, numbered captures are still inserted into $matches. For example, after matching against a $url of ‘http://regex.info/’, the previous example’s $UrlInfo contains:

array

(

0 => 'http://regex.info',

'proto' => 'http',

1 => 'http',

'host' => 'regex.info',

2 => 'regex.info'

)

This repetition is somewhat wasteful, but that’s the price the current implementation makes you pay for the convenience and clarity of named captures. For clarity, I would not recommend using both named and numeric references to elements of $matches, except for $matches[0] as the overall match.

Note that the 3 and ‘port’ entries in this example are not included because that set of capturing parentheses didn’t participate in the match and was trailing (so the entries were stripped  450).

450).

By the way, although it’s not currently an error to use a numeric name, e.g., ⌈(?P<2>···)⌋, it’s not at all recommended. PHP 4 and PHP 5 differ in how they treat this odd situation, neither of which being what anyone might expect. It’s best to avoid numeric named-capture names altogether.

Getting more details on the match: PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE

If preg_match’s fourth argument, flags, is provided and contains PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE (which is the only flag value allowed with preg_match) the values placed in $matches change from simple strings to subarrays of two elements each. The first element of each subarray is the matched text, while the second element is the offset from the start of the string where the matched text was actually matched (or -1 if the parentheses didn’t participate in the match).

The offsets reported are zero-based counts relative to the start of the string, even if a fifth-argument $offset is provided to have preg_match begin its match attempt from somewhere within the string. They are always reported in bytes, even when the u pattern modifier was used ( 447).

447).

As an example, consider plucking the HREF attribute from an anchor tag. An HTML’s attribute value may be presented within double quotes, single quotes, or without quotes entirely; such values are captured in the following regex’s first, second, and third set of capturing parentheses, respectively:

preg_match('/href \s*=\s* (?: "([^"]*)" | \'([^\']*)\' | ([^\s\'">]+) )/ix',

$tag,

$matches,

PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE);

If $tag contains

<a name=bloglink href='http://regex.info/blog/' rel="nofollow">

the match succeeds and $matches is left containing:

array

(

/* Data for the overall match */

0 => array ( 0 => "href='http://regex.info/blog/'",

1 => 17 ),

/* Data for the first set of parentheses */

1 => array ( 0 => "",

1 => -1 ),

/* Data for the second set of parentheses */

2 => array ( 0 => "http://regex.info/blog/",

1 => 23 )

)

$matches[0][0] is the overall text matched by the regex, with $matches[0][1] being the byte offset into the subject string where that text begins.

For illustration, another way to get the same string as $matches[0][0] is:

substr($tag, $matches[0][1], strlen($matches[0][0]));

$matches[1][1] is -1, reflecting that the first set of capturing parentheses didn’t participate in the match. The third set didn’t either, but as mentioned earlier ( 450), data on trailing non-participating sets is not included in

450), data on trailing non-participating sets is not included in $matches.

The offset argument

If an offset argument is given to preg_match, the engine starts the match attempt that many bytes into the subject (or, if the offset is negative, starts checking that far from the end of the subject). The default is equivalent to an offset of zero (that is, the match attempt starts at the beginning of the subject string).

Note that the offset must be given in bytes even if the u pattern modifier is used. Using an incorrect offset (one that starts the engine “inside” a multibyte character) causes the match to silently fail.

Starting at a non-zero offset doesn’t make that position the ⌈^⌋-matching “start of the string” to the regex engine — it’s simply where, in the overall string, the regex engine begins its match attempt. Lookbehind, for example, can look to the left of the starting offset.

preg_match_all

Usage

preg_match_all(pattern, subject, matches [, flags [, offset ]])

Argument Summary

pattern |

The pattern argument: a regex in delimiters, with optional modifiers ( |

subject |

Target string in which to search. |

matches |

Variable to receive match data (required). |

flags |

Optional flags that influence overall function behavior: PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE ( and/or one of: PREG_PATTERN_ORDER ( PREG_SET_ORDER ( |

offset |

Optional zero-based offset into subject at which the match attempt will begin (the same as |

Return Value

preg_match_all returns the number of matches found.

Discussion

preg_match_all is similar to preg_match, except that after finding the first match in a string, it continues along the string to find subsequent matches. Each match creates an array’s worth of match data, so in the end, the matches variable is filled with an array of arrays, each inner array representing one match.

Here’s a simple example:

if (preg_match_all('/<title>/i', $html, $all_matches) > 1)

print "whoa, document has more than one <title>!\n";

The third argument (the variable to be assigned the accumulated information about successful matches) is required by preg_match_all; it’s not optional as it is with preg_match. That’s why, even though it is otherwise unused in this example, it appears in the preg_match_all call.

Collecting match data

Another difference — the primary difference — from preg_match is the data placed in that third-argument variable. preg_match performs at most one match, so it places one match’s worth of data into its matches variable. On the other hand, preg_match_all can match many times, so it may place the data from many such matches into its third-argument variable. To highlight the difference, I use $all_matches as the name of the variable with preg_match_all, rather than the $matches name commonly used with preg_match.

You can have preg_match_all arrange the data it places in $all_matches in one of two ways, selected by one of these mutually-exclusive fourth-argument flags:

PREG_PATTERN_ORDER or PREG_SET_ORDER.

The default PREG_PATTERN_ORDER arrangement

Here’s an example showing the PREG_PATTERN_ORDER arrangement (which I call “collated” — more on that in a bit). This is also the default arrangement if neither flag is specified, which is the case in this example:

$subject = "

Jack A. Smith

Mary B. Miller";

/* No order-related flag implies PREG_PATTERN_ORDER */

preg_match_all('/^(\w+) (\w\.) (\w+)$/m', $subject, $all_matches);

This leaves $all_matches with:

array

(

/* $all_matches[0] is an array of full matches */

0 => array ( 0 => "Jack A. Smith", /* full text from first match */

1 => "Mary B. Miller" /* full text from second match */ ),

/* $all_matches[1] is an array of strings captured by 1st set of parens */

1 => array ( 0 => "Jack", /* first match's 1st capturing parens */

1 => "Mary" /* second match's 1st capturing parens */ ),

/* $all_matches[2] is an array of strings captured by 2nd set of parens */

2 => array ( 0 => "A.", /* first match's 2nd capturing parens */

1 => "B." /* second match's 2nd capturing parens */),

/* $all_matches[3] is an array of strings captured by 3rd set of parens */

3 => array ( 0 => "Smith", /* first match's 3rd capturing parens */

1 => "Miller" /* second match's 3rd capturing parens */)

)

There were two matches, each of which resulted in one “overall match” string, and three substrings via capturing parentheses. I call this “collated” because all of the overall matches are grouped together in one array (in $all_matches[0]), all the strings captured by the first set of parentheses are grouped together in another array ($all_matches[1]), and so on.

By default, elements in $all_matches are collated, but you can change this with the PREG_SET_ORDER flag.

The PREG_SET_ORDER arrangement

The alternative data arrangement is “stacked,” selected with the PREG_SET_ORDER flag. It keeps all the data from the first match in $all_matches[0], all the data from the second match in $all_matches[1], etc. It’s exactly what you’d get if you walked the string yourself, pushing the $matches from each successful preg_match onto a $all_matches array.

Here’s the PREG_SET_ORDER version of the previous example:

$subject = "

Jack A. Smith

Mary B. Miller";

preg_match_all('/^(\w+) (\w\.) (\w+)$/m', $subject, $all_matches, PREG_SET_ORDER);

It leaves $all_matches with:

array

(

/* $all_matches[0] is just like a preg_match's entire $matches */

0 => array ( 0 => "Jack A. Smith", /* first match's full match */

1 => "Jack", /* first match's 1st capturing parens */

2 => "A.", /* first match's 2nd capturing parens */

3 => "Smith" /* first match's 3rd capturing parens */ ),

/* $all_matches[1] is also just like a preg_match's entire $matches */

1 => array ( 0 => "Mary B. Miller", /* second match's full match */

1 => "Mary", /* second match's 1st capturing parens */

2 => "B.", /* second match's 2nd capturing parens */

3 => "Miller" /* second match's 3rd capturing parens */ ),

)

Here’s a short summary of the two arrangements:

Type |

Flag |

Description and Example |

Collated |

PREG_PATTERN_ORDER |

Comparable parts from each match grouped.

|

Stacked |

PREG_SET_ORDER |

All per-match data kept together.

|

preg_match_all and the PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE flag

You can use PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE with preg_match_all just as you can with preg_match, turning each leaf element of $all_matches into a two-element array (matched text plus byte offset). This means that $all_matches becomes an array of arrays of arrays, which is quite a mouthful. If you wish to use both PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE and PREG_SET_ORDER, use a binary “or” operator to combine them:

preg_match_all($pattern, $subject, $all_matches,

PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE | PREG_SET_ORDER);

preg_match_all with named capture

If named captures are used, additional elements are added to $all_matches based on the names (just as with preg_match  451). After

451). After

$subject = "

Jack A. Smith

Mary B. Miller";

/* No order-related flag implies PREG_PATTERN_ORDER */

preg_match_all('/^(?P<Given>\w+) (?P<Middle>\w\.) (?P<Family>\w+)$/m',

$subject, $all_matches);

$all_matches is left with:

array

(

0 => array ( 0 => "Jack A. Smith", 1 => "Mary B. Miller" ),

"Given" => array ( 0 => "Jack", 1 => "Mary" ),

1 => array ( 0 => "Jack", 1 => "Mary" ),

"Middle" => array ( 0 => "A.", 1 => "B." ),

2 => array ( 0 => "A.", 1 => "B." ),

"Family" => array ( 0 => "Smith", 1 => "Miller" ),

3 => array ( 0 => "Smith", 1 => "Miller" )

)

The same example with PREG_SET_ORDER:

$subject = "

Jack A. Smith

Mary B. Miller";

preg_match_all('/^(?P<Given>\w+) (?P<Middle>\w\.) (?P<Family>\w+)$/m',

$subject, $all_matches, PREG_SET_ORDER);

leaves $all_matches with:

array

(

0 => array ( 0 => "Jack A. Smith",

Given => "Jack",

1 => "Jack",

Middle => "A.",

2 => "A.",

Family => "Smith",

3 => "Smith" ),

1 => array ( 0 => "Mary B. Miller",

Given => "Mary",

1 => "Mary",

Middle => "B.",

2 => "B.",

Family => "Miller",

3 => "Miller" )

)

Personally, I would prefer that the numerical keys be omitted when named capture is used because it would keep things cleaner and more efficient, but since they retained, you can simply ignore them if you don’t need them.

preg_replace

Usage

preg_replace(pattern, replacement, subject [, limit [, count ]])

Argument Summary

pattern |

The pattern argument: a regex in delimiters, with optional modifiers. Pattern may also be an array of pattern-argument strings. |

replacement |

The replacement string, or, if pattern is an array, replacement may be an array of replacement strings. The string (or strings) are interpreted as PHP code if the e pattern-modifier is used ( |

subject |

Target string in which to search. It may also be an array of strings (each processed in turn). |

limit |

Optional integer to limit the number of replacements ( |

count |

Optional variable to receive the count of replacements actually done (PHP 5 only |

Return Value

If subject is a single string, the return value is also a string (a possibly changed copy of subject). If subject is an array of strings, the return value is also an array (which contains possibly changed elements of subject).

Discussion

PHP offers a number of ways to search and replace on text. If the search part can be described as simple strings, str_replace or str_ireplace are the most appropriate, but if the content to be searched is more complicated, preg_replace is the right tool.

As a simple example, let’s visit a common web experience: entering a credit card or phone number in a form. How many times have you seen “no spaces or dashes” instructions in this situation? Doesn’t it seem lazy to place such a silly (but admittedly small) burden on the user when it would be so easy for the programmer to allow the user to enter the information naturally, with spaces, dashes, or other punctuation?† After all, it’s trivial to “clean up” such input:

$card_number = preg_replace('/\D+/', '', $card_number);

/* $card_number now has only digits, or is empty */

This uses preg_replace to remove nondigits. Described more literally, it uses preg_replace to make a copy of $card_number, replacing any sequences of non-digits with nothingness (an empty string), and assign that possibly changed copy back into $card_number.

Basic one-string, one-pattern, one-replacement preg_replace

The first three arguments (pattern, replacement, and subject) can be either strings or arrays of strings. In the common case where all three are simply strings, preg_replace makes a copy of the subject, finds the first match of the pattern within it, replaces the text matched with a copy of the replacement, and then continues along doing the same with subsequent matches in the subject until it reaches the end of the string.

Within the replacement string, ‘$0’ refers to the full text of the match at hand, ‘$1’ refers to the text matched within the first set of capturing parentheses, ‘$2’ the second set, and so on. Note that these dollar-sign/number sequences are not references to variables as they are in some languages, but simply sequences that preg_replace recognizes for special treatment. You can also use a form with braces around the number, as with ‘${0}’ and ‘${1}’, which is necessary to disambiguate the reference when a number immediately follows it.

Here’s a simple example that wraps HTML bold tags around words in all caps:

$html = preg_replace('/\b[A-Z]{2,}\b/', '<b>$0</b>', $html);

If the e pattern modifier is used (it is allowed only with preg_replace), the replacement string is taken as PHP code and executed after each match, the result of which is used as the replacement string. Here’s an extension of the previous example that lowercases the word being wrapped in bold tags:

$html = preg_replace('/\b[A-Z]{2,}\b/e',

'strtolower("<b>$0</b>")',

$html);

If, for example, the text matched by the regex is ‘HEY’, that word is substituted in the replacement string for the ‘$0’ capture reference. This results in the string ‘strtolower("<b>HEY</b>")’, which is then executed as PHP code, yielding, finally, ‘<b>hey</b>’ as the replacement text.

With the e pattern modifier, capture references in the replacement string are interpolated in a special manner: quotation marks (single or double) within interpolated values are escaped. Without this special processing, a quote within the interpolated value could render the resulting string invalid as PHP code.

If using the e pattern modifier and making references to external variables in the replacement string, it’s best to use singlequotes for the replacement string literal so the variables are note interpolated at the wrong time.

This example is similar to PHP’s built in htmlspecialchars() function:

$replacement = array ('&' => '&',

'<' => '<',

'>' => '>',

'"' => '"');

$new_subject = preg_replace('/[&<">]/eS', '$replacement["$0"]', $subject);

It’s important in this example for replacement to be a single-quoted string, to hide the $replacement variable interpolation until it is processed by preg_replace as PHP code. Were it a double-quoted string, it would be processed by PHP before being passed to preg_replace.

The S pattern modifier is used for extra efficiency ( 478).

478).

If a fourth argument, limit, is passed to preg_replace, it dictates the maximum number of replacements that will be made (on a per-regex, per-string basis; see the next section). The default is -1, which means “no limit.”

If a fifth argument, count, is passed (not allowed with PHP 4), it’s a variable into which preg_replace writes the number of replacements actually done. If you want to know only whether replacements were done, you can compare the original subject with the result, but it’s much more efficient to check the count argument.

Multiple subjects, patterns, and replacements

As mentioned in the previous section, the subject argument is often just a simple string, which is what we’ve seen in all the examples so far. However, the subject may also be an array of strings, in which case the search and replace is conducted on each string in turn. The return value is then the array of resulting strings.

Independent of whether the subject is a string or an array of strings, the pattern and replacement arguments may also be arrays of strings. Here are the pairings and their meanings:

Pattern |

Replacement |

Action |

string |

string |

Apply pattern, replacing each match with replacement |

array |

string |

Apply each pattern in turn, replacing each match with the replacement |

array |

array |

Apply each pattern in turn, replacing matches with the pattern’s corresponding replacement |

string |

array |

(not allowed) |

Again, if the subject argument is an array, the action is performed on each subject element in turn, and the return value is an array of strings as well.

Note that the limit argument is per pattern, per subject. It’s not an overall limit across patterns or subject strings. The $count that is returned, however, is the overall total for all patterns and subject strings.

Here’s an example of preg_replace where both the pattern and the replacement are arrays. Its result is similar to PHP’s built-in htmlspecialchars() function, which “cooks” text so that it’s safe to use within HTML:

$cooked = preg_replace(

/* Match with these . . . */ array('/&/', '/</', '/>/', '/"/' ),

/* Replace with these . . . */ array('&', '<', '>', '"'),

/* ...in a copy of this */ $text

);

When this snippet is given $text such as:

AT&T --> "baby Bells"

it sets $cooked to:

AT&T --> "baby Bells"

You can, of course, build the argument arrays ahead of time; this version works identically (and produces identical results):

$patterns = array('/&/', '/</', '/>/', '/"/' );

$replacements = array('&', '<', '>', '"');

$cooked = preg_replace($patterns, $replacements, $text);

It’s convenient that preg_replace accepts array arguments (it saves you from having to write loops to iterate through patterns and subject strings yourself), but it doesn’t actually add any extra functionality. Patterns are not processed “in parallel,” for example. However, the built-in processing is more efficient than writing the loops yourself in PHP-level code, and is likely more readable as well.

To illustrate, consider an example in which all arguments are arrays:

$result_array = preg_replace($regex_array, $replace_array, $subject_array);

This is comparable to:

$result_array = array();

foreach ($subject_array as $subject)

{

reset($regex_array); // Prepare to walk through these two arrays

reset($replace_array); // in their internal array orders.

while (list(,$regex) = each($regex_array))

{

list(,$replacement) = each($replace_array);

// The regex and replacemnet are ready, so apply to the subject . . .

$subject = preg_replace($regex, $replacement, $subject);

}

// Having now been processed by all the regexes, we're done with this subject . . .

$result_array[] = $subject; // ... so append to the results array.

}

Ordering of array arguments

When pattern and replacement are both arrays, they are paired via the arrays’ internal order, which is generally the order the elements were added to the arrays (the first element added to the pattern array is paired with the first element added to the replacement array, and so forth). This means that the ordering works properly with “literal arrays” created and populated with array(), as with this example:

$subject = "this has 7 words and 31 letters";

$result = preg_replace(array('/[a-z]+/', '/\d+/'),

array('word<$0>', 'num<$0>'),

$subject);

print "result: $result\n";

The ⌈[a-z]+⌋ is paired with ‘word<$0>’, and then ⌈\d+⌋ is paired with ‘num<$0>’, all of which results in:

result: word<this> word<has> num<7> word<words> word<and> num<31> word<letters>

On the other hand, if the pattern or replacement arrays are built piecemeal over time, the arrays’ internal order may become different from the apparent order of the keys (that is, from the ordering implied by the numeric value of the keys). That’s why the snippet on the previous page that mimics preg_replace with array arguments is careful to use each to walk the arrays in the internal array order, whatever their keys might be.

If your pattern or replacement arrays might have internal ordering different from the apparent ordering by which you want to pair them, you may want to use the ksort() function to ensure that each array’s actual and apparent orderings are the same.

When both pattern and replacement are arrays, but there are more pattern elements than replacement elements, an empty string is used as the replacement string for patterns without a corresponding element in the replacement array.

The order in which the elements of pattern are arranged can matter significantly, because they are processed in the order found in the array. What, for example, would be the result if the element order of this example’s pattern (and, in conjunction, its replacement array) was reversed? That is, what’s the result of the following?

$subject = "this has 7 words and 31 letters";

$result = preg_replace(array('/\d+/', '/[a-z]+/'),

array('num<\0>', 'word<\0>'),

$subject);

print "result: $result\n";

![]() Flip the page to check your answer.

Flip the page to check your answer.

preg_replace_callback

Usage

preg_replace_callback(pattern, callback, subject [, limit [, count ]])

Argument Summary

pattern |

The pattern argument: a regex in delimiters, with optional modifiers ( |

callback |

A PHP callback, to be invoked upon each successful match to generate the replacement text. |

subject |

Target string in which to search. It may also be an array of strings (each processed in turn). |

limit |

Optional limit on number of replacements ( |

count |

Optional variable to receive the count of replacements actually done (since PHP 5.1.0 only |

Return Value

If subject is a single string, the return value is a string (a possibly changed copy of subject). If subject is an array of strings, the return value is an array (of possibly changed elements of subject).

Discussion

preg_replace_callback is similar to preg_replace, except that the replacement argument is a PHP callback rather than a string or array of strings. It’s similar to preg_replace with the e pattern modifier ( 459), but more efficient (and likely easier to read, for that matter, when the replacement expression is complicated).

459), but more efficient (and likely easier to read, for that matter, when the replacement expression is complicated).

See the PHP documentation for more on callbacks, but in short, a PHP callback refers (in one of several ways) to a function that is invoked in a predetermined situation, with predetermined arguments, to produce a value for a predetermined use. In the case of preg_replace_callback, the invocation happens with each successful regex match, with one predetermined argument (the match’s $matches array). The function’s return value is used by preg_replace_callback as the replacement text.

A callback can refer to its function in one of three ways. In one, the callback is simply a string containing the name of a function to be called. In another, the callback is an anonymous function produced by PHP’s create_function builtin. We’ll see examples using both these callback forms soon. The third callback form, which is not otherwise mentioned in this book, is designed for object-oriented programming, and consists of a two-element array (a class name and a method within it to invoke).

Here’s the example from page 460 rewritten using preg_replace_callback and a support function. The callback is a string containing the support function’s name:

$replacement = array ('&' => '&',

'<' => '<',

'>' => '>',

'"' => '"');

/*

* Given a $matches from a successful match in which $matches[0] is the text character in need of

* conversion to HTML, return the appropriate HTML string. Because this function is used under only

* carefully controlled conditions, we feel safe blindly using the arguments.

*/

function text2html_callback($matches)

{

global $replacement;

return $replacement[$matches[0]];

}

$new_subject = preg_replace_callback('/[&<">]/S', /* pattern */

"text2html_callback", /* callback */

$subject);

When called with a $subject of, say,

"AT&T" sounds like "ATNT"

the variable $new_subject is left with:

"AT&T" sounds like "ATNT"

This example’s text2html_callback is a normal PHP function designed to be used as a callback for preg_replace_callback, which calls its callback with one argument, the $matches array (which, of course, you’re free to name as you like when creating the function, but I follow convention by using $matches).

For completeness, I’d like to show this example using an anonymous function (created with PHP’s built-in create_function function). This version assumes the same $replacement variable as above. The function’s content is exactly the same, but this time it’s not a named function, and it can be called only from within preg_replace_callback:

$new_subject = preg_replace_callback('/[&<">]/S',

create_function('$matches',

'global $replacement;

return $replacement[$matches[0]];'),

$subject);

A callback versus the e pattern modifier

For simple tasks, a e pattern modifier with preg_replace may be more readable than preg_replace_callback. However, when efficiency is important, remember that the e pattern modifier causes the replacement argument to be reinterpreted as PHP code, from scratch, upon each successful match. That could create a lot of overhead that preg_replace_callback does not entail (with a callback, the PHP code is evaluated only once).

preg_split

Usage

preg_split(pattern, subject [, limit,[ flags ]])

Argument Summary

pattern |

The pattern argument: a regex in delimiters, with optional modifiers ( |

subject |

Target string to partition. |

limit |

Optional integral value used to limit the number of elements the subject is split into. |

flags |

Optional flags that influence overall behavior; any combination of: PREG_SPLIT_NO_EMPTY PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE PREG_SPLIT_OFFSET_CAPTURE These are discussed starting on page 468. Combine multiple flags with a binary “or” operator (as in the example on page 456) |

Return Value

An array of strings is returned.

Discussion

preg_split splits a copy of a string into multiple parts, returning them in an array. The optional limit argument allows the number of parts to be capped at the given maximum (with the last part becoming an “everything else” part, if needed). With the various flags, you can adjust which parts are returned, and how.

In one sense, preg_split is the opposite of preg_match_all in that preg_split isolates parts of a string that don’t match a regular expression. Described more traditionally, preg_split returns parts of a string that remain after the regex-matched sections are removed. preg_split is the more powerful regular-expression equivalent of PHP’s simple explode built-in function.

As a simple example, consider a financial site’s search form accepting a space-separated list of stock tickers. To isolate the tickers, you could use explode:

$tickers = explode(' ', $input);

but this does not allow for sloppy typists who may add more than one space between stock tickers. A better approach is to use ⌈\s+⌋ as a preg_split separator:

$tickers = preg_split('/\s+/', $input);

Yet, despite having clear “separated by spaces” instructions, users often intuitively separate multiple items with commas (or commas and spaces), entering something such as ‘YHOO, MSFT, GOOG’. You can easily allow for these situations with:

$tickers = preg_split('/[\s,]+/', $input);

With our example input, this leaves $tickers with an array of three elements: ‘YHOO’, ‘MSFT’, and ‘GOOG’.

Along different lines, if the input is comma-separated “tags” (à la “Web 2.0,” such as photo tagging), you might want to use ⌈\s*,\s*⌋ to allow for spacing around the commas:

$tags = preg_split('/\s*,\s*/', $input);

It’s illustrative to compare ⌈\s*,\s*⌋ with ⌈[\s,]+⌋ in these examples. The former splits on commas (a comma is required for the split), but also removes any whitespace that may be on either side of the comma. With $input of ‘123,,,456’, it matches three times (one comma each), returning four elements: ‘123’, two empty elements, and ‘456’.

On the other hand, ⌈[\s,]+⌋ splits on any comma, sequence of commas, whitespace, or combination thereof. With our example of ‘123,,,456’, it matches the three commas together, returning just two elements: ‘123’ and ‘456’.

preg_split’s limit argument

The limit argument tells preg_split that it shouldn’t split the input string into more than a certain number of parts. If the limit number of parts is reached before the end of the string is reached, whatever remains is put into the final element.

As an example, consider parsing an HTTP response from a server by hand. The standard indicates that the header is separated from the body by the four-character sequence ‘\r\n\r\n’, but unfortunately, in practice some servers use only ‘\n\n’ to separate the two. Luckily, preg_split makes it easy to handle either situation. Assuming that the entire HTTP response is in $response,

$parts = preg_split('/\r? \n \r? \n/x', $response, 2);

leaves the header in $parts[0] and the body in $parts[1]. (The S pattern modifier is used for efficiency  478.)

478.)

That third argument, 2, is the limit, meaning that the subject string is to be split into no more than two parts. If a match is indeed found, the part before the match (what we know to be the header) becomes the first element of the return value. Since “the rest of the string” would make the second element, thereby reaching the limit, it (what we know to be the body) is left unsearched and intact as the final, limit-reaching second element of the return value.

Without a limit (or with a limit of -1, which means the same thing), preg_split splits the subject as many times as it can, which would likely break the body into many parts. Setting a limit does not guarantee that the result array will have that many entries, but merely guarantees that it will not have more than that number (although see the section on PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE below for situation where even this is not necessarily true).

There are two situations where it makes sense to set an artificial limit. We’ve already seen the first situation: when you want the final element to be an “all the rest” element. In the previous example, once the first part (the header) was isolated, we didn’t want the rest (the body) to be split further. Thus, our use of a 2 limit kept the body intact.

A limit is also efficient in situations where you know you won’t use all the elements that an unlimited split would create. For example, if you had a $data string with many fields separated by ⌈\s*,\s*⌋ (say, “name” and “address” and “age,” etc.) and you needed only the first two, you could use a limit of 3 to let preg_split stop working once the first two items have been isolated:

$fields = preg_split('/ \s* ,\s* /x', $data, 3);

This leaves everything else in the final, third array element, which you could then remove with array_pop or simply ignore.

If you wish to use any of the preg_split flags (discussed in the next section) in the default “no limit” mode, you must provide a placeholder limit argument of -1, which indeed means “no limit.” On the other hand, a limit value of 1 effectively means “don’t split,” so it is not very useful. The meaning of zero and negative values other than -1 are explicitly undefined, so don’t use them.

preg_split’s flag arguments

preg_split supports three flags that influence how it works. They can be used individually or combined with the binary “or” operator (see the example on page 456).

PREG_SPLIT_OFFSET_CAPTURE

As with the PREG_OFFSET_CAPTURE flag used with preg_match and preg_match_all, this flag changes the result array such that each element is itself a string-and-offset array.

PREG_SPLIT_NO_EMPTY

This flag causes preg_split to internally ignore empty strings, not returning them in the result array and not counting them toward the split limit. Empty strings are the result of the regex matching at the very beginning or very end of the subject string, or matching consecutively in a row with nothing in between.

Revisiting the “Web 2.0” tags example from earlier ( 466), if the variable

466), if the variable $input contains the string ‘party,, fun’ then

$tags = preg_split('/ \s* ,\s* /x', $input);

leaves $tags with three strings: ‘party’, an empty string, and ‘fun’. The empty string is the “nothingness” between the two matches of the commas.

If we repeat the same example with the PREG_SPLIT_NO_EMPTY flag,

$tags = preg_split('/ \s* ,\s* /x', $input, -1, PREG_SPLIT_NO_EMPTY);

only ‘party’ and ‘fun’ are returned.

PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE

This flag includes in the result the text matched within capturing parentheses of the regular expression doing the split. As a simple example, let’s say you want to parse a set of search terms where ‘and’ and ‘or’ are used to link terms, such as:

DLSR camera and Nikon D200 or Canon EOS 30D

Without PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE, the code

$parts = preg_split('/ \s+ (and|or) \s+ /x', $input);

results in $parts being assigned this array:

array ('DLSR camera', 'Nikon D200', 'Canon EOS 30D')

Everything matched as the separator has been removed. However, with the addition of the PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE flag (and a -1 placeholder limit argument):

$parts = preg_split('/ \s+ (and|or) \s+ /x', $input, -1,

PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE);

$parts includes sections of the separator matched within capturing parentheses:

array ('DLSR camera', 'and', 'Nikon D200', 'or', 'Canon EOS 30D')

In this case, one element per split is added to the result array, as there’s one set of capturing parentheses in the regular expression. Your processing can then walk the elements of $parts, recognizing the ‘and’ and ‘or’ elements for special treatment.

It’s important to note that if non-capturing parentheses had been used (a pattern argument of '/\s+(?:and|or)\s+/') the PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE flag would have made no difference because it works only with capturing parentheses.

As another example, recall the earlier stock-ticker example from page 466:

$tickers = preg_split('/[\s,]+/', $input);

If we add capturing parentheses and PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE,

$tickers = preg_split('/([\s,]+)/', $input, -1, PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE);

the result is that nothing from $input is thrown away; it’s merely partitioned into the elements of $tickers. When you process the $tickers array, you know that every odd-numbered element was matched by ⌈([\s,]+)⌋. This might be useful, for example, if in the process of displaying an error message to the user, you want to do some processing on the various parts, then stitch them back together to end up with a post-processed version of the original input string.

By the way, elements added to the result array via PREG_SPLIT_DELIM_CAPTURE do not impact the split limit. This is the only case where the resulting array can have more elements than the split limit (many more elements if there are many sets of capturing parentheses in the regex).

Trailing non-participatory capturing parentheses do not contribute to the result array. This mouthful means that pairs of capturing parentheses that do not participate in the final match (see page 450) may or may not add an empty string to the result array. They do if a higher-numbered set of parentheses is part of the final match, and don’t otherwise. Note that the addition of the PREG_SPLIT_NO_EMPTY flag renders this issue moot, because it elides empty strings regardless.

preg_grep

Usage

preg_grep(pattern, input [, flags ])

Argument Summary

pattern |

The pattern argument: a regex in delimiters, with optional modifiers. |

input |

An array whose values are copied to the return-value array if they match pattern. |

flags |

An optional value, PREG_GREP_INVERT or zero. |

An array containing values from input that match pattern (or, conversely, values that do not match pattern if the PREG_GREP_INVERT flag has been used).

Discussion

preg_grep is used to make a copy of an array, input, keeping only elements whose value matches (or, with the PREG_GREP_INVERT flag, doesn’t match) the pattern. The original key associated with the value is kept.

As a simple example, consider

preg_grep('/\s/', $input);

which returns an array populated with elements in the $input array whose value has whitespace. The opposite is:

preg_grep('/\s/', $input, PREG_GREP_INVERT);

which populates the return array with elements whose value does not contain whitespace. Note that this second example is different from:

preg_grep('/^\S+$/', $input);

in that the latter does not include elements with empty (zero-length) values.

preg_quote

Usage

preg_quote(input [, delimiter ])

Argument Summary

input |

A string you’d like to use literally within a preg pattern argument ( |

delimiter |

Optional one-character string indicating the delimiter you intend to use in the construction of the pattern argument. |

Return Value

preg_quote returns a string, a copy of input with regex metacharacters escaped. If delimiter has been specified, instances of it are also escaped.

Discussion

If you have a string that you’d like to use as literal text within a regex, you can pass the string through the built-in preg_quote function to escape any regex metacharacter it may contain. Optionally, you can also specify the delimiter you intend to use when using the result to create a pattern, and occurrences of it will also be escaped.

preg_quote is a highly specialized function that isn’t useful in many situations, but here’s an example:

/* Given $MailSubject, find if $MailMessage is about that subject */

$pattern = '/^Subject:\s+(Re:\s*)*'.preg_quote($MailSubject, '/') . '/mi';

If $MailSubject contains a string such as

**Super Deal** (Act Now!)

$pattern winds up with:

/^Subject:\s+(Re:\s*)*\*\*Super Deal\*\* \(Act Now\!\)/mi

which is suitable for use as a pattern argument with the preg functions.

Specifying ‘{’ or any of the other paired delimiters does not cause the opposing character (e.g., ‘}’) to be escaped, so be sure to stick with the non-paired delimiters.

Also, whitespace and ‘#’ are not escaped, so the result is likely not appropriate for use with the x modifier.

When it comes down to it, preg_quote is only a partial solution for representing arbitrary text as a PHP regular expression. It solves only the “text to regex” part of the problem, but does not follow through with the “regex to pattern argument” step needed to actually use it with any of the preg functions. A solution to that step is covered in the next section.

“Missing” Preg Functions

PHP’s built-in preg functions provide a good range of functionality, but there have been times that I’ve found certain aspects a bit lacking. One example we’ve already seen is my special version of preg_match ( 454).

454).

Another area where I’ve felt the need to build my own support functions involves situations where regular expressions are not provided directly in the program via literal pattern-argument strings, but brought in from outside the program (e.g., read from a file, or provided by a user via a web form). As we’ll see in the next section, converting from a raw regular-expression string to a preg-appropriate pattern-argument can be tricky.

Also, before using such a regular expression, it’s generally a good idea to validate that it’s syntactically correct. We’ll look into that as well.

As with all the code samples in this book, the functions on the coming pages are all available for download at my web site: http://regex.info/.

preg_regex_to_pattern

If you have a raw regular expression in a string (perhaps read from a configuration file, or submitted via a web form) that you’d like to use with a preg function, you must first wrap it in delimiters to make a preg-appropriate pattern argument.

The problem

In many cases, converting a regular expression into a pattern argument is as simple as wrapping the regex with forward slashes. This would convert, for example, a regular-expression string ‘[a-z]+’ to ‘/[a-z]+/’, a string appropriate for use as a preg pattern argument.

However, the conversion becomes more complex if the regular expression actually contains the delimiter in which you choose to wrap it. For example, if the regex string is ‘^http://([^/:]+)’, simply wrapping it in forward slashes yields ‘/^http://([^/:]+)/’, which results in an “Unknown modifier /” error when used as a pattern modifier.

As described in the sidebar on page 448, the odd error message is generated because the first and second forward slashes in the string are taken as the delimiters, and whatever follows (in this case, the third forward slash in the string) is taken as the start of the pattern-modifier list.

The solution

There are two ways to avoid the embedded-delimiter conflict. One is to choose a delimiter character that doesn’t appear within the regular expression, and this is certainly the recommend way when you’re composing a pattern-modifier string by hand. That’s why I used {···} as the delimiters in the examples on pages 444, 449, and 450 (to name only a few).

It may not be easy (or even possible) to choose a delimiter that doesn’t appear in the regex, because the text could contain every delimiter, or you may not know in advance what text you have to work with. This becomes a particular concern when working programatically with a regex in a string, so it’s easier to simply use a second approach: select a delimiter character, then escape any occurrence of that character within the regex string.

It’s actually quite a bit trickier than it might seem at first, because you must pay attention to some important details. For example, an escape at the end of the target text requires special handling so it won’t escape the appended delimiter.

Here’s a function that accepts a regular-expression string and, optionally, a pattern-modifiers string, and returns a pattern string ready for use with preg functions. The code’s cacophony of backslashes (both regex and PHP string escapes) is one of the most complex you’re likely to see; this code is not light reading by any measure. (If you need a refresher in PHP single-quoted string semantics, refer to page 444.)

/*

* Given a raw regex in a string (and, optionally, a pattern-modifiers string), return a string suitable

* for use as a preg pattern. The regex is wrapped in delimiters, with the modifiers (if any) appended.

*/

function preg_regex_to_pattern($raw_regex, $modifiers = "")

{

/*

* To convert a regex to a pattern, we must wrap the pattern in delimiters (we'll use a pair of

* forward slashes) and append the modifiers. We must also be sure to escape any unescaped

* occurrences of the delimiter within the regex, and to escape a regex-ending escape

* (which, if left alone, would end up escaping the delimiter we append).

*

* We can't just blindly escape embedded delimiters, because it would break a regex containing

* an already-escaped delimiter. For example, if the regex is '\/', a blind escape results

* in '\\/' which would not work when eventually wrapped with delimiters: '/\\//'.

*

* Rather, we'll break down the regex into sections: escaped characters, unescaped forward

* slashes (which we'll need to escape), and everything else. As a special case, we also look out

* for, and escape, a regex-ending escape.

*/

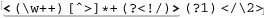

if (! preg_match('{\\\\(?:/|$)}', $raw_regex)) /* '/' followed by '\' or EOS */

{

/* There are no already-escaped forward slashes, and no escape at the end, so it's

* safe to blindly escape forward slashes. */

$cooked = preg_replace('!/!', '\/', $raw_regex);

}

else

{

/* This is the pattern we'll use to parse $raw_regex.

* The two parts whose matches we'll need to escape are within capturing parens. */

$pattern = '{ [^\\\\/]+ | \\\\. | ( / | \\\\$ ) }sx';

/* Our callback function is called upon each successful match of $pattern in $raw-regex.

* If $matches[1] is not empty, we return an escaped version of it.

* Otherwise, we simply return what was matched unmodified. */

$f = create_function('$matches', ' // This long

if (empty($matches[1])) // singlequoted

return $matches[0]; // string becomes

else // our function

return "\\\\" . $matches[1]; // code.

');

/* Actually apply $pattern to $raw_regex, yielding $cooked */

$cooked = preg_replace_callback($pattern, $f, $raw_regex);

}

/* $cooked is now safe to wrap -- do so, append the modifiers, and return */

return "/$cooked/$modifiers";

}

This is a bit more involved than I’d like to recode each time I need it, which is why I’ve encapsulated it into a function (one I’d like to see become part of the built-in preg suite).

It’s instructive to look at the regular expression used in the lower half of the function, with preg_replace_callback, and how it and the callback work to walk through the pattern string, escaping any unescaped forward slashes, yet leaving escaped ones alone.

Syntax-Checking an Unknown Pattern Argument

After wrapping the regex in delimiters, you’ve ensured that it’s in the proper form for a preg pattern argument, but not that the original raw regex is syntactically valid in the first place.

For example, if the original regex string is ‘*.txt’ — perhaps because someone accidentally entered a file glob ( 4) instead of a regular expression — the result from our

4) instead of a regular expression — the result from our preg_regex_to_pattern is /*.txt/. That doesn’t contain a valid regular expression, so it fails with the warning (if warnings are turned on):

Compilation failed: nothing to repeat at offset 0

PHP doesn’t have a built-in function to test whether a pattern argument and its regular expression are syntactically valid, but I have one for you below.

preg_pattern_error tests the pattern argument simply enough, by trying to use it — that’s the one-line preg_match call in the middle of the function. The rest of the function concerns itself with PHP administrative issues of corralling the error message that preg_match might try to display.

/*

* Return an error message if the given pattern argument or its underlying regular expression

* are not syntactically valid. Otherwise (if they are valid), false is returned.

*/

function preg_pattern_error($pattern)

{

/*

* To tell if the pattern has errors, we simply try to use it.

* To detect and capture the error is not so simple, especially if we want to be sociable and not

* tramp on global state (e.g., the value of $php_errormsg). So, if 'track_errors' is on, we preserve

* the $php_errormsg value and restore it later. If' track_errors' is not on, we turn it on (because

* we need it) but turn it off when we're done.

*/

if ($old_track = ini_get("track_errors"))

$old_message = isset($php_errormsg) ? $php_errormsg : false;

else

ini_set('track_errors', 1);

/* We're now sure that track_errors is on. */

unset($php_errormsg);

@ preg_match($pattern, "");/* actually give the pattern a try! */

$return_value = isset($php_errormsg) ? $php_errormsg : false;

/* We've now captured what we need; restore global state to what it was. */

if ($old_track)

$php_errormsg = isset($old_message) ? $old_message : false;

else

ini_set('track_errors', 0);

return $return_value;

}

Syntax-Checking an Unknown Regex

Finally, here’s a function that utilizes what we’ve already developed to test a raw regular expression (one without delimiters and pattern modifiers). It returns an appropriate error string if the regular expression is not syntactically valid, and returns false if it is syntactically valid.

/*

* Return a descriptive error message if the given regular expression is invalid.

* If it's valid, false is returned.

*/

function preg_regex_error($regex)

{

return preg_pattern_error(preg_regex_to_pattern($regex));

}

Recursive Expressions

Most aspects of the preg engine’s flavor are covered as general topics in Chapter 3, but the flavor does offer something new in its interesting way of matching nested constructs: recursive expressions.