7

Perl

Perl has been featured prominently in this book, and with good reason. It is popular, extremely rich with regular expressions, freely and readily obtainable, easily approachable by the beginner, and available for a remarkably wide variety of platforms, including pretty much all flavors of Windows, Unix, and the Mac.

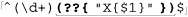

Some of Perl’s programming constructs superficially resemble those of C or other traditional programming languages, but the resemblance stops there. The way you wield Perl to solve a problem—The Perl Way—is different from traditional languages. The overall layout of a Perl program often uses traditional structured and object-oriented concepts, but data processing often relies heavily on regular expressions. In fact, I believe it is safe to say that regular expressions play a key role in virtually all Perl programs. This includes everything from huge 100,000-line systems, right down to simple one-liners, like

% perl -pi -e 's{([-+]?\d+(\.\d*)?)F\b}{sprintf "%.0fC",($1-32)*5/9)eg' *.txt

which goes through *.txt files and replaces Fahrenheit values with Celsius ones (reminiscent of the first example from Chapter 2).

In This Chapter

This chapter looks at everything regex about Perl,† including details of its regex flavor and the operators that put them to use. This chapter presents the regex-relevant details from the ground up, but I assume that you have at least a basic familiarity with Perl. (If you’ve read Chapter 2, you’re already familiar enough to at least start using this chapter.) I’ll often use, in passing, concepts that have not yet been examined in detail, and I won’t dwell much on non-regex aspects of the language. It might be a good idea to keep the Perl documentation handy, or perhaps O’Reilly’s Programming Perl.

Perhaps more important than your current knowledge of Perl is your desire to understand more. This chapter is not light reading by any measure. Because it’s not my aim to teach Perl from scratch, I am afforded a luxury that general books about Perl do not have: I don’t have to omit important details in favor of weaving one coherent story that progresses unbroken through the whole chapter. Some of the issues are complex, and the details thick; don’t be worried if you can’t take it all in at once. I recommend first reading the chapter through to get the overall picture, and returning in the future to use it as a reference as needed.

To help guide your way, here’s a quick rundown of how this chapter is organized:

- “Perl’s Regex Flavor” (

286) looks at the rich set of metacharacters supported by Perl regular expressions, along with additional features afforded to raw regex literals.

286) looks at the rich set of metacharacters supported by Perl regular expressions, along with additional features afforded to raw regex literals. - Regex Related Perlisms” (

293) looks at some aspects of Perl that are of particular interest when using regular expressions. Dynamic scoping and expression context are covered in detail, with a strong bent toward explaining their relationship with regular expressions.

293) looks at some aspects of Perl that are of particular interest when using regular expressions. Dynamic scoping and expression context are covered in detail, with a strong bent toward explaining their relationship with regular expressions. - Regular expressions are not useful without a way to apply them, so the following sections provide all the details to Perl’s sometimes magical regex controls:

“The

qr/···/Operator and Regex Objects” ( 303)

303)“The Match Operator” (

306)

306)“The Substitution Operator” (

318)

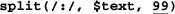

318)“The Split Operator” (

321)

321) - “Fun with Perl Enhancements” (

326) goes over a few Perl-only enhancements to Perl’s regular-expression repertoire, including the ability to execute arbitrary Perl code during the application of a regular expression.

326) goes over a few Perl-only enhancements to Perl’s regular-expression repertoire, including the ability to execute arbitrary Perl code during the application of a regular expression. - “Perl Efficiency Issues” (

347) delves into an area close to every Perl programmer’s heart. Perl uses a Traditional NFA match engine, so you can feel free to start using all the techniques from Chapter 6 right away. There are, of course, Perl-specific issues that can greatly affect in what way, and how quickly, Perl applies your regexes. We’ll look at them here.

347) delves into an area close to every Perl programmer’s heart. Perl uses a Traditional NFA match engine, so you can feel free to start using all the techniques from Chapter 6 right away. There are, of course, Perl-specific issues that can greatly affect in what way, and how quickly, Perl applies your regexes. We’ll look at them here.

Perl in Earlier Chapters

Perl is touched on throughout most of this book:

- Chapter 2 contains an introduction to Perl, with many regex examples.

- Chapter 3 contains a section on Perl history (

88), and touches on numerous regex-related issues that apply to Perl, such as character-encoding issues (including Unicode

88), and touches on numerous regex-related issues that apply to Perl, such as character-encoding issues (including Unicode  105), match modes (

105), match modes ( 110), and a long overview of metacharacters (

110), and a long overview of metacharacters ( 113).

113). - Chapter 4 is a key chapter that demystifies the Traditional NFA match engine found in Perl. Chapter 4 is extremely important to Perl users.

- Chapter 5 contains many examples, discussed in the light of Chapter 4. Many of the examples are in Perl, but even those not presented in Perl apply to Perl.

- Chapter 6 is an important chapter to the user of Perl interested in efficiency.

In the interest of clarity for those not familiar with Perl, I often simplified Perl examples in these earlier chapters, writing in as much of a self-documenting pseudo-code style as possible. In this chapter, I’ll try to present examples in a more Perlish style of Perl.

Regular Expressions as a Language Component

An attractive feature of Perl is that regex support is so deftly built in as part of the language. Rather than providing stand-alone functions for applying regular expressions, Perl provides regular-expression operators that are meshed well with the rich set of other operators and constructs that make up the Perl language.

With as much regex-wielding power as Perl has, one might think that it’s overflowing with different operators and such, but actually, Perl provides only four regex-related operators, and a small handful of related items, shown in Table 7-1.

Table 7-1: Overview of Perl’s Regex-Related Items

Regex-Related Operators

|

Modifiers Modify How ...

|

Related Pragmas

|

After-Match Variables (

(best to avoid—see “Perl Efficiency Issues” |

Related Functions

|

Related Variables

|

Perl is extremely powerful, but all that power in such a small set of operators can be a dual-edged sword.

Perl’s Greatest Strength

The richness of variety and options among Perl’s operators and functions is perhaps its greatest feature. They can change their behavior depending on the context in which they’re used, often doing just what the author naturally intends in each differing situation. In fact, O’Reilly’s Programming Perl goes so far as to boldly state “In general, Perl operators do exactly what you want....” The regex match operator m/regex/, for example, offers an amazing variety of different functionality depending upon where, how, and with which modifiers it is used.

Perl’s Greatest Weakness

This concentrated richness in expressive power is also one of Perl’s least-attractive features. There are innumerable special cases, conditions, and contexts that seem to change out from under you without warning when you make a subtle change in your code—you’ve just hit another special case you weren’t aware of.† The Programming Perl quote in the previous paragraph continues “...unless you want consistency.” Certainly, when it comes to computer science, there is a certain appreciation to boring, consistent, dependable interfaces. Perl’s power can be a devastating weapon in the hands of a skilled user, but it sometimes seems with Perl, you become skilled by repeatedly shooting yourself in the foot.

Perl’s Regex Flavor

Table 7-2 on the facing page summarizes Perl’s regex flavor. It used to be that Perl had many metacharacters that no other system supported, but over the years, other systems have adopted many of Perl’s innovations. These common features are covered by the overview in Chapter 3, but there are a few Perl-specific items discussed later in this chapter. (Table 7-2 has references to where each item is discussed.)

The following notes supplement the table:

\b is a character shorthand for backspace only within a character class. Outside of a character class, \b matches a word boundary ( 133).

133).

Octal escapes accept two- and three-digit numbers.

The ⌈\xnum⌋ hex escape accepts two-digit numbers (and one-digit numbers, but with a warning if warnings are turned on). The ⌈\x{num}⌋ syntax accepts a hexadecimal number of any length.

Table 7-2: Overview of Perl’s Regular-Expression Flavor

Character Shorthands |

|

|

|

Character Classes and Class-Like Constructs |

|

Classes: |

|

Any character except newline: dot (with |

|

Unicode combining sequence: |

|

Exactly one byte (can be dangerous): |

|

|

Class shorthands: |

|

Unicode properties, scripts, and blocks: |

Anchors and Other Zero-Width Tests |

|

Start of line/string: |

|

End of line/string: |

|

End of previous match: |

|

Word boundary: |

|

Lookaround: |

|

Comments and Mode Modifiers |

|

Mode modifiers: |

|

Mode-modified spans: |

|

Comments: |

|

Grouping, Capturing, Conditional, and Control |

|

Capturing parentheses: |

|

Grouping-only parentheses: |

|

Atomic grouping: |

|

Alternation: |

|

Conditional: |

|

Greedy quantifiers: |

|

Lazy quantifiers: |

|

Embedded code: |

|

Dynamic regex: |

|

In Regex Literals Only |

|

|

Variable interpolation: |

|

Fold next character’s case: |

|

Case-folding span: |

|

Literal-text span: |

|

Named Unicode character: |

(c) – may also be used within a character class |

|

\w, \d, \s, etc., fully support Unicode.

Perl’s \s does not match an ASCII vertical tab character ( 115).

115).

Perl’s Unicode support is for Unicode Version 4.1.0.

Perl’s Unicode support is for Unicode Version 4.1.0.

Unicode Scripts are supported. Script and property names may have the ‘Is’ prefix, but they don’t require it ( 125). Block names may have the ‘

125). Block names may have the ‘In’ prefix, but require it only when a block name conflicts with a script name.

The ⌈\p{L&}⌋ pseudo-property is supported, as well as ⌈\p{Any},⌋ ⌈\p{All}⌋, ⌈\p{Assigned}⌋, and ⌈\p{Unassigned}⌋.

The long property names like ⌈\p{Letter}⌋ are supported. Names may have a space, underscore, or nothing between the word parts of a name (for example ⌈\p{Lowercase_Letter}⌋ may also be written as⌈\p{LowercaseLetter}⌋ or ⌈\p{Lowercase•Letter}⌋.) For consistency, I recommend using the long names as shown in the table on page 123.

⌈\p{^···}⌋ is the same as ⌈\P{···}⌋.

Word boundaries fully support Unicode.

Word boundaries fully support Unicode.

Lookaround may have capturing parentheses.

Lookaround may have capturing parentheses.

Lookbehind is limited to subexpressions that always match fixed-width text.

The

The /x modifier recognizes only ASCII whitespace. The /m modifier affects only newlines, and not the full list of Unicode line terminators.

The /i modifier works properly with Unicode.

Not all metacharacters are created equal. Some “regex metacharacters” are not even supported by the regex engine, but by the preprocessing Perl gives to regex literals.

Regex Operands and Regex Literals

The final items in Table 7-2 are marked “regex literals only.” A regex literal is the “regex” part of m/regex/, and while casual conversation refers to that as “the regular expression,” the part between the ‘/’ delimiters is actually parsed using its own unique rules. In Perl jargon, a regex literal is treated as a “regex-aware double-quoted string,” and it’s the result of that processing that’s passed to the regex engine. This regex-literal processing offers special functionality in building the regular expression.

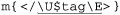

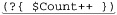

For example, a regex literal offers variable interpolation. If the variable $num contains 20, the code m/:.{$num}:/ produces the regex ⌈: .{20} :⌋. This way, you can build regular expressions on the fly. Another service given to regex literals is automatic case folding, as with \U···\E to ensure letters are uppercased. As a silly example, m/abc\Uxyz\E/ creates the regex ⌈abcXYZ⌋. This example is silly because if someone wanted ⌈abcXYZ⌋ they could just type m/abcXYZ/ directly, but its value becomes apparent when combined with variable interpolation: if the variable $tag contains the string “title” the code  produces

produces  .

.

What’s the opposite of a regex literal? You can also use a string (or any expression) as a regex operand. For example:

$MatchField = "^Subject:"; # Normal string assignment

*

*

*

if ($text =~ $MatchField) {

*

*

*

When $MatchField is used as an operand of =~, its contents are interpreted as a regular expression. That “interpretation” is as a plain vanilla regex, so variable interpolation and things like \Q···\E are not supported as they would be for a regex literal.

Here’s something interesting: if you replace

$text =~ $MatchField

with

$text =~ m/$MatchField/

the result is exactly the same. In this case, there’s a regex literal, but it’s composed of just one thing — the interpolation of the variable $MatchField. The contents of a variable interpolated by a regex literal are not treated as a regex literal, and so things like \U···\E and $var within the value interpolated are not recognized. (Details on exactly how regex literals are processed are covered on page 292.)

If used more than once during the execution of a program, there are important efficiency issues with regex operands that are raw strings, or that use variable interpolation. These are discussed starting on page 348.

Features supported by regex literals

The following features are offered by regex literals:

- Variable Interpolation Variable references beginning with

$and@are interpolated into the value to use for the regex. Those beginning with$insert a simple scalar value. Those beginning with@insert an array or array slice into the value, with elements separated by spaces (actually, by the contents of the$"variable, which defaults to a space).In Perl, ‘

%’ introduces a hash variable, but inserting a hash into a string doesn’t make much sense, so interpolation via%is not supported. - Named Unicode Characters If you have “

use charnames ':full';” in the program, you can refer to Unicode characters by name using the\N{name}sequence. For instance,\N{LATIN SMALL LETTER SHARP S}matches “ß” The list of Unicode characters that Perl understands can be found in Perl’s unicore directory, in the file UnicodeData.txt. This snippet shows the file’s location:use Config;

print "$Config{privlib}/unicore/UnicodeData.txt\n";It’s easy to forget “

use charnames ':full';” or the colon before ‘full’, but if you do,\N{···}won’t work. Also,\N{···}doesn’t work if you use regex overloading, described later in this list. - Case-Folding Prefix The special sequences

\land\ucause the character that follows to be made lowercase and uppercase, respectively. This is usually used just before variable interpolation to force the case on the first character brought in from the variable. For example, if the variable$titlecontains “mr.” the codem/···\u$title···/creates the regex ⌈···Mr.···⌋. The same functionality is provided by the Perl functionslcfirst()anducfirst(). - Case-Folding Span The special sequences

\Land\Ucause characters that follow to be made lowercase and uppercase, respectively, until the end of the regex literal, or until the special sequence\E. For example, with the same$titleas before, the codem/···\u$title\E···/creates the regex ⌈···MR.···⌋ . The same functionality is provided by the Perl functionslc()anduc().You can combine a case-folding prefix with a case-folding span: the code

m/···\L \u$title\E···/ensures ⌈···Mr.···⌋ regardless of the original capitalization. - Literal-Text Span The sequence

\Q“quotes” regex metacharacters (i.e., puts a backslash in front of them) until the end of the string, or until a\Esequence. It quotes regex metacharacters, but not quote regex-literal items like variable interpolation,\U,and, of course, the\Eitself. Oddly, it also does not quote backslashes that are part of an unknown sequence, such as in\For\H. Even with\Q···\E, such sequences still produce “unrecognized escape” warnings.In practice, these restrictions are not that big a drawback, as

\Q···\Eis normally used to quote interpolated text, where it properly quotes all metacharacters. For example, if$titlecontains “Mr.,“ the codem/···\Q$title\E···/creates the regex ⌈···Mr\.···⌋, which is what you’d want if you wanted to match the text in$title, rather than the regex in$title.This is particularly useful if you want to incorporate user input into a regex. For example,

m/\Q$Userlnput\E/idoes a case-insensitive search for the characters (as a string, not a regex) in$Userlnput.The

\Q···\Efunctionality is also provided by the Perl functionquotemeta(). - Overloading You can pre-process the literal parts of a regex literal in any way you like with overloading. It’s an interesting concept, but one with severe limitations as currently implemented. Overloading is covered in detail, starting on page 341.

Picking your own regex delimiters

One of the most bizarre (yet, most useful) aspects of Perl’s syntax is that you can pick your own delimiters for regex literals. The traditional delimiter is a forward slash, as with m/···/, s/···/···/, and qr/···/, but you can actually pick any non-alphanumeric, non-whitespace character. Some commonly used examples include:

m!···! m{···}

m,···, m<···>

s|···|···| m[···]

qr#···# m(···)

The four on the right are among the special-case delimiters:

- The four examples on the right side of the list above have different opening and closing delimiters, and may be nested (that is, may contain copies of the delimiters so long as the opens and closes pair up properly). Because parentheses and square brackets are so prevalent in regular expressions,

m(···)andm[···]are probably not as appealing as the others. In particular, with the/xmodifier, something such as the following becomes possible:m{

regex # comments

here # here

}x;If one of these pairs is used for the regex part of a substitute, another pair (the same as the first, or, if you like, different) is used for the replacement string. Examples include:

s{···}{···}

s{···}!···!

s<···>(···)

s[···]/···/If this is done, you can put whitespace and comments between the two pairs of delimiters. More on the substitution operator’s replacement string operand can be found on page 319.

- For the match operator only, a question mark as a delimiter has a little-used special meaning (suppress additional matches) discussed in the section on the match operator (

308).

308). - As mentioned on page 288, a regex literal is parsed like a “regex-aware double-quoted string.” If a single quote is used as the delimiter, however, those features are inhibited. With

m'···', variables are not interpolated, and the constructs that modify text on the fly (e.g.,\Q···\E) do not work, nor does the\N{···}construct.m'···'might be convenient for a regex that has many@, to save having to escape them.

For the match operator only, the m may be omitted if the delimiter is a slash or a question mark. That is,

$text =~ m/···/;

$text =~ /···/;

are the same. My preference is to always explicitly use the m.

How Regex Literals Are Parsed

For the most part, one “just uses” the regex-literal features just discussed, without the need to understand the exact details of how Perl converts them to a raw regular expression. Perl is very good at being intuitive in this respect, but there are times when a more detailed understanding can help. The following lists the order in which processing appears to happen:

- The closing delimiter is found, and the modifiers (such as

/i, etc.) are read. The rest of the processing then knows if it’s in/xmode. - Variables are interpolated.

- If regex overloading is in effect, each part of the literal is given to the overload routine for processing. Parts are separated by interpolated variables; the values interpolated are not made available to overloading.

If regex overloading is not in effect,

\N{···}sequences are processed. - Case-folding constructs (e.g.,

\Q···\E)are applied. - The result is presented to the regex engine.

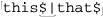

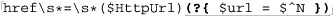

This describes how the processing appears to the programmer, but in reality, the internal processing done by Perl is quite complicated. Even step #2 must understand the regular-expression metacharacters, so as not to, for example, treat the underlined portion of  as a variable reference.

as a variable reference.

Regex Modifiers

Perl’s regex operators allow regex modifiers, placed after the closing delimiter of the regex literal (like the i in m/···/i, s/···/···/i, or qr/···/i). There are five core modifiers that all regex operators support, shown in Table 7-3.

The first four, described in Chapter 3, can also be used within a regex itself as a mode-modifier ( 135) or mode-modified span (

135) or mode-modified span ( 135). When used both within the regex, and as part of one of the match operators, the in-regex versions take precedence for the part of the regex they control. (Another way to look at it is that once a modifier has been applied to some part of a regex, nothing can “unmodify” that part of a regex.)

135). When used both within the regex, and as part of one of the match operators, the in-regex versions take precedence for the part of the regex they control. (Another way to look at it is that once a modifier has been applied to some part of a regex, nothing can “unmodify” that part of a regex.)

Table 7-3: The Core Modifiers Available to All Regex Operators

|

Ignore letter case during match |

|

|

Free-spacing and comments regex mode |

|

|

Dot-matches-all match mode |

|

|

Enhanced line anchor match mode |

|

|

Compile only once |

The fifth core modifier, /o, has mostly to do with efficiency. It is discussed later in this chapter, starting on page 348.

If you need more than one modifier, group the letters together and place them in any order after the closing delimiter, whatever it might be.† Keep in mind that the slash is not part of the modifier—you can write m/<title>/i as m|<title>|i, or perhaps m{<title>}i, or even m<<title>>i. Nevertheless, when discussing modifiers, it’s common to always write them with a slash, e.g., “the /i modifier.”

Regex-Related Perlisms

A variety of general Perl concepts pertain to our study of regular expressions. The next few sections discuss:

- Context An important concept in Perl is that many functions and operators respond to the context they’re used in. For example, Perl expects a scalar value as the conditional of a

whileloop, but a list of values as the arguments to aprintstatement. Since Perl allows expressions to “respond” to the context in which they’re in, identical expressions in each case might produce wildly different results. - Dynamic Scope Most programming languages support the concept of

localand global variables, but Perl provides an additional twist with something known as dynamic scoping. Dynamic scoping temporarily “protects” a global variable by saving a copy of its value and automatically restoring it later. It’s an intriguing concept that’s important for us because it affects$1and other match-related variables.

Expression Context

The notion of context is important throughout Perl, and in particular, to the match operator. An expression might find itself in one of three contexts, list, scalar, or void, indicating the type of value expected from the expression. Not surprisingly, a list context is one where a list of values is expected of an expression. A scalar context is one where a single value is expected. These two are very common and of great interest to our use of regular expressions. Void context is one in which no value is expected.

Consider the two assignments:

$s = expression one;

@a = expression two;

Because $s is a simple scalar variable (it holds a single value, not a list), it expects a simple scalar value, so the first expression, whatever it may be, finds itself in a scalar context. Similarly, because @a is an array variable and expects a list of values, the second expression finds itself in a list context. Even though the two expressions might be exactly the same, they might return completely different values, and cause completely different side effects while they’re at it. Exactly what happens depends on each expression.

For example, the localtime function, if used in a list context, returns a list of values representing the current year, month, date, hour, etc. But if used in a scalar context, it returns a textual version of the current time along the lines of ‘Mon Jan 20 22:05:15 2003’.

As another example, an I/O operator such as <MYDATA> returns the next line of the file in a scalar context, but returns a list of all (remaining) lines in a list context.

Like localtime and the I/O operator, many Perl constructs respond to their context. The regex operators do as well — the match operator m/···/, for example, sometimes returns a simple true/false value, and sometimes a list of certain match results. All the details are found later in this chapter.

Contorting an expression

Not all expressions are natively context-sensitive, so Perl has rules about what happens when a general expression is used in a context that doesn’t exactly match the type of value the expression normally returns. To make the square peg fit into a round hole, Perl “contorts” the value to make it fit. If a scalar value is returned in a list context, Perl makes a list containing the single value on the fly. Thus, @a = 42 is the same as @a = (42).

On the other hand, there’s no general rule for converting a list to a scalar. If a literal list is given, such as with

$var = ($this, &is, 0xA, 'list');

the comma-operator returns the last element, ‘list’, for $var. If an array is given, as with $var = @array, the length of the array is returned.

Some words used to describe how other languages deal with this issue are cast, promote, coerce, and convert, but I feel they are a bit too consistent (boring?) to describe Perl’s attitude in this respect, so I use “contort.”

Dynamic Scope and Regex Match Effects

Perl’s two types of storage (global and private variables) and its concept of dynamic scoping are important to understand in their own right, but are of particular interest to our study of regular expressions because of how after-match information is made available to the rest of the program. The next sections describe these concepts, and their relation to regular expressions.

Global and private variables

On a broad scale, Perl offers two types of variables: global and private. Private variables are declared using my(···). Global variables are not declared, but just pop into existence when you use them. Global variables are always visible from anywhere and everywhere within the program, while private variables are visible, lexically, only to the end of their enclosing block. That is, the only Perl code that can directly access the private variable is the code that falls between the my declaration and the end of the block of code that encloses the my.

The use of global variables is normally discouraged, except for special cases, such as the myriad of special variables like $1, $_, and @ARGV. Regular user variables are global unless declared with my, even if they might “look” private. Perl allows the names of global variables to be partitioned into groups called packages, but the variables are still global. A global variable $Debug within the package Acme::Widget has a fully qualified name of $Acme::Widget::Debug, but no matter how it’s referenced, it’s still the same global variable. If you use strict;, all (non-special) globals must either be referenced via fully-qualified names, or via a name declared with our (our declares a name, not a new variable — see the Perl documentation for details).

Dynamically scoped values

Dynamic scoping is an interesting concept that few programming languages provide. We’ll see the relevance to regular expressions soon, but in a nutshell, you can have Perl save a copy of the value of a global variable that you intend to modify within a block, and restore the original copy automatically at the time when the block ends. Saving a copy is called creating a new dynamic scope, or localizing.

One reason that you might want to do this is to temporarily update some kind of global state that’s maintained in a global variable. Let’s say that you’re using a package, Acme::Widget, and it provides a debugging flag via the global variable $Acme::Widget::Debug. You can temporarily ensure that debugging is turned on with code like:

*

*

*

{

local($Acme::Widget::Debug) = 1; # Ensure it's turned on

# work with Acme::Widget while debugging is on

*

*

*

}

# $Acme::Widget::Debug is now back to whatever it had been before

*

*

*

It’s that extremely ill-named function local that creates a new dynamic scope. Let me say up front that the call to local does not create a new variable. local is an action, not a declaration. Given a global variable, local does three things:

- Saves an internal copy of the variable’s value

- Copies a new value into the variable (either

undef, or a value assigned to thelocal) - Slates the variable to have its original value restored when execution runs off the end of the block enclosing the

local

This means that “local” refers only to how long any changes to the variable will last. The localized value lasts as long as the enclosing block is executing. Even if a subroutine is called from within that block, the localized value is seen. (After all, the variable is still a global variable.) The only difference from a non-localized global variable is that when execution of the enclosing block finally ends, the previous value is automatically restored.

An automatic save and restore of a global variable’s value is pretty much all there is to local. For all the misunderstanding that has accompanied local, it’s no more complex than the snippet on the right of Table 7-4 illustrates.

As a matter of convenience, you can assign a value to local($SomeVar), which is exactly the same as assigning to $SomeVar in place of the undef assignment. Also, the parentheses can be omitted to force a scalar context.

As a practical example, consider having to call a function in a poorly written library that generates a lot of “Use of uninitialized value” warnings. You use Perl’s -w option, as all good Perl programmers should, but the library author apparently didn’t. You are exceedingly annoyed by the warnings, but if you can’t change the library, what can you do short of stop using -w altogether? Well, you could set a local value of $^W, the in-code debugging flag (the variable name ^W can be either the two characters, caret and ‘W’, or an actual control-w character):

Table 7-4: The Meaning of local

Normal Perl |

Equivalent Meaning |

{ |

{ |

{

local $^W = 0; # Ensure warnings are off.

UnrulyFunction(···);

}

# Exiting the block restores the original value of $^W.

The call to local saves an internal copy of the value of the global variable $^w, whatever it might be. Then that same $^w receives the new value of zero that we immediately scribble in. When UnrulyFunction is executing, Perl checks $^W and sees the zero we wrote, so doesn’t issue warnings. When the function returns, our value of zero is still in effect.

So far, everything appears to work just as if local isn’t used. However, when the block is exited right after the subroutine returns, the original value of $^w is restored. Your change of the value was local, in time, to the life of the block. You’d get the same effect by making and restoring a copy yourself, as in Table 7-4, but local conveniently takes care of it for you.

For completeness, let’s consider what happens if I use my instead of local.† Using my creates a new variable with an initially undefined value. It is visible only within the lexical block it is declared in (that is, visible only by the code written between the my and the end of the enclosing block). It does not change, modify, or in any other way refer to or affect other variables, including any global variable of the same name that might exist. The newly created variable is not visible elsewhere in the program, including from within UnrulyFunction. In our example snippet, the new $^w is immediately set to zero but is never again used or referenced, so it’s pretty much a waste of effort. (While executing UnrulyFunction and deciding whether to issue warnings, Perl checks the unrelated global variable $^w.)

A better analogy: clear transparencies

A useful analogy for local is that it provides a clear transparency (like used with an overhead projector) over a variable on which you scribble your own changes. You (and anyone else that happens to look, such as subroutines and signal handlers) will see the new values. They shadow the previous value until the point in time that the block is finally exited. At that point, the transparency is automatically removed, in effect, removing any changes that might have been made since the local.

This analogy is actually much closer to reality than saying “an internal copy is made.” Using local doesn’t actually make a copy, but instead puts your new value earlier in the list of those checked whenever a variable’s value is accessed (that is, it shadows the original). Exiting a block removes any shadowing values added since the block started. Values are added manually, with local, but here’s the whole reason we’ve been looking localization: regex side-effect variables have their values dynamically scoped automatically.

Regex side effects and dynamic scoping

What does dynamic scoping have to do with regular expressions? A lot. A number of variables like $& (refers to the text matched) and $1 (refers to the text matched by the first parenthesized subexpression) are automatically set as a side effect of a successful match. They are discussed in detail in the next section. These variables have their value dynamically scoped automatically upon entry to every block.

To see the benefit of this design choice, realize that each call to a subroutine involves starting a new block, which means a new dynamic scope is created for these variables. Because the values before the block are restored when the block exits (that is, when the subroutine returns), the subroutine can’t change the values that the caller sees.

As an example, consider:

if (m/(···)/)

{

DoSomeOtherStuff();

print "the matched text was $1.\n";

}

Because the value of $1 is dynamically scoped automatically upon entering each block, this code snippet neither cares, nor needs to care, whether the function DoSomeOtherStuff changes the value of $1 or not. Any changes to $1 by the function are contained within the block that the function defines, or perhaps within a sub-block of the function. Therefore, they can’t affect the value this snippet sees with the print after the function returns.

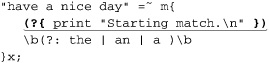

The automatic dynamic scoping is helpful even when not so apparent:

if ($result =~ m/ERROR=(.*)/) {

warn "Hey, tell $Config{perladmin} about $1!\n";

}

The standard library module Config defines an associative array %Config, of which the member $Config{perladmin} holds the email address of the local Perlmaster. This code could be very surprising if $1 were not automatically dynamically scoped, because %Config is actually a tied variable. That means any reference to it involves a behind-the-scenes subroutine call, and the subroutine within Config that fetches the appropriate value when $Config{···} is used invokes a regex match. That match lies between your match and your use of $1, so if $1 were not dynamically scoped, it would be destroyed before you used it. As it is, any changes in $1 during the $Config{···} processing are safely hidden by dynamic scoping.

Dynamic scoping versus lexical scoping

Dynamic scoping provides many rewards if used effectively, but haphazard dynamic scoping with local can create a maintenance nightmare, as readers of a program find it difficult to understand the increasingly complex interactions among the lexically disperse local, subroutine calls, and references to localized variables.

As I mentioned, the my(···) declaration creates a private variable with lexical scope. A private variable’s lexical scope is the opposite of a global variable’s global scope, but it has little to do with dynamic scoping (except that you can’t local the value of a my variable). Remember, local is just an action, while my is both an action and, importantly, a declaration.

Special Variables Modified by a Match

A successful match or substitution sets a variety of global, read-only variables that are always automatically dynamically scoped. These values never change if a match attempt is unsuccessful, and are always set when a match is successful. When appropriate, they are set to the empty string (a string with no characters in it), or undefined (a “no value” value, similar to, yet testably distinct from, an empty string). Table 7-5 shows examples.

In more detail, here are the variables set after a match:

|

A copy of the text successfully matched by the regex. This variable (along with |

Table 7-5: Example Showing After-Match Special Variables

After the match of

the following special variables are given the values shown. |

||

Variable |

Meaning |

Value |

|

Text before match |

|

|

Text matched |

|

|

Text after match |

|

|

Text matched within 1st set of parentheses |

|

|

Text matched within 2nd set of parentheses |

undef |

|

Text matched within 3rd set of parentheses |

|

|

Text matched within 4th set of parentheses |

|

|

Text from highest-numbered |

|

|

Text from most recently closed |

|

|

Array of match-start indices into target text |

|

|

Array of match-end indices into target text |

|

|

A copy of the target text in front of (to the left of) the match’s start. When used in conjunction with the |

|

A copy of the target text after (to the right of) the successfully matched text. |

$1, $2, $3, etc.

The text matched by the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc., set of capturing parentheses. (Note that $0 is not included here—it is a copy of the script name and not related to regular expressions.) These are guaranteed to be undefined if they refer to a set of parentheses that doesn’t exist in the regex, or to a set that wasn’t actually involved in the match.

These variables are available after a match, including in the replacement operand of s/···/···/. They can also be used within the code parts of an embedded-code or dynamic-regex construct ( 327). Otherwise, it makes little sense to use them within the regex itself. (That’s what ⌈

327). Otherwise, it makes little sense to use them within the regex itself. (That’s what ⌈\1⌋ and friends are for.) See “Using $1 Within a Regex?” on page 303.

The difference between ⌈(\w+)⌋ and ⌈(\w)+⌋ can be seen in how $1 is set. Both regexes match exactly the same text, but they differ in what subexpression falls within the parentheses. Matching against the string ‘tubby’, the first one results in $1 having the full ‘tubby’, while the latter one results in it having only ‘y’: with ⌈(\w)+⌋, the plus is outside the parentheses, so each iteration causes them to start capturing anew, leaving only the last character in $1.

Also, note the difference between ⌈(x)?⌋ and ⌈(x?)⌋. With the former, the parentheses and what they enclose are optional, so $1 would be either ‘x’ or undefined. But with ⌈(x?)⌋, the parentheses enclose a match — what is optional are the contents. If the overall regex matches, the contents matches something, although that something might be the nothingness ⌈x?⌋ allows. Thus, with ⌈(x?)⌋ the possible values of $1 are ‘x’ and an empty string. The following table shows some examples:

Sample Match |

Resulting |

Sample Match |

Resulting |

|

empty string |

|

empty string |

|

undefined |

|

undefined |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When adding parentheses just for capturing, as was done here, the decision of which to use is dependent only upon the semantics you want. In these examples, since the added parentheses have no affect on the overall match (they all match the same text), the only differences among them is in the side effect of how $1 is set.

|

This is a copy of the highest numbered $url =~ m{ to access the value of the If there are no capturing parentheses in the regex (or none are used during the match), it becomes undefined. |

|

A copy of the most-recently-closed |

These are arrays of starting and ending offsets (string indices) into the target text. They might be a bit confusing to work with, due to their odd names. The first element of each refers to the overall match. That is, the first element of @-, accessed with $-[0], is the offset from the beginning of the target string to where the match started. Thus, after

$text = "Version 6 coming soon?";

*

*

*

$text =~ m/\d+/;

the value of $-[0] is 8, indicating that the match started eight characters into the target string. (In Perl, indices are counted started at zero.)

The first element of @+, accessed with $+[0], is the offset to the end of the match. With this example, it contains 9, indicating that the overall match ended nine characters from the start of the string. So, using them together, substr($text, $-[0], $+[0] - $-[0]) is the same as $& if $text has not been modified, but doesn’t have the performance penalty that $& has ( 356). Here’s an example showing a simple use of

356). Here’s an example showing a simple use of @-:

1 while $line =~ s/\t/' ' x (8 - $-[0] % 8)/e;

Given a line of text, it replaces tabs with the appropriate number of spaces.†

Subsequent elements of each array are the starting and ending offsets for captured groups. The pair $-[1] and $+[1] are the offsets into the target text where $1 was taken, $-[2] and $+[2] for $2, and so on.

|

This variable holds the resulting value of the most recently executed embedded-code construct, except that an embedded-code construct used as the if of a ⌈ |

When a regex is applied repeatedly with the /g modifier, each iteration sets these variables afresh. That’s why, for instance, you can use $1 within the replacement operand of s/···/···/g and have it represent a new slice of text with each match.

Using $1 within a regex?

The Perl man page makes a concerted effort to point out that ⌈\1⌋ is not available as a backreference outside of a regex. (Use the variable $1 instead.) The variable $1 refers to a string of static text matched during some previously completed successful match. On the other hand, ⌈\l⌋ is a true regex metacharacter that matches text similar to that matched within the first parenthesized subexpression at the time that the regex-directed NFA reaches the ⌈\1⌋. What it matches might change over the course of an attempt as the NFA tracks and backtracks in search of a match.

The opposite question is whether $1 and other after-match variables are available within a regex operand. They are commonly used within the code parts of embedded-code and dynamic-regex constructs ( 327), but otherwise make little sense within a regex. A

327), but otherwise make little sense within a regex. A $1 appearing in the “regex part” of a regex operand is treated exactly like any other variable: its value is interpolated before the match or substitution operation even begins. Thus, as far as the regex is concerned, the value of $1 has nothing to do with the current match, but rather is left over from some previous match.

The qr/···/ Operator and Regex Objects

Introduced briefly in Chapter 2 and Chapter 6 ( 76; 277),

76; 277), qr/···/ is a unary operator that takes a regex operand and returns a regex object. The returned object can then be used as a regex operand of a later match, substitution, or split, or can be used as a sub-part of a larger regex.

Regex objects are used primarily to encapsulate a regex into a unit that can be used to build larger expressions, and for efficiency (to gain control over exactly when a regex is compiled, discussed later).

As described on page 291, you can pick your own delimiters, such as qr{···} or qr!···!. It supports the core modifiers /i, /x, /s, /m, and /o.

Building and Using Regex Objects

Consider the following, with expressions adapted from Chapter 2 ( 76):

76):

my $HostnameRegex = qr/[-a-z0-9]+(?:\.[-a-z0-9]+)*\.(?:com;edu;info)/i;

my $HttpUrl = qr{

http:// $HostnameRegex \b # Hostname

(?:

/ [-a-z0-9R:\@&?=+,.!/~*'%\$]* # Optional path

(?<![.,?!]) # Not allowed to end with [.,?!]

)?

}ix;

The first line encapsulates our simplistic hostname-matching regex into a regular expression object, and saves it to the variable $HostnameRegex. The next lines then use that in building a regex object to match an HTTP URL, saved to the variable $HttpUrl. Once constructed, they can be used in a variety of ways, such as

if ($text =~ $HttpUrl) {

print "There is a URL\n";

}

to merely inspect, or perhaps

while ($text =~ m/($HttpUrl)/g) {

print "Found URL: $1\n";

}

to find and display all HTTP URLs.

Now, consider changing the definition of $HostnameRegex to this, derived from Chapter 5 ( 205):

205):

my $HostnameRegex = qr{

# One or more dot-separated parts···

(?: [a-z0-9]\. | [a-z0-9][-a-z0-9]{0,61}[a-z0-9]\. )*

# Followed by the final suffix part···

(?: com|edu|gov|int|mil|net|org|biz|info|···|aero|[a-z][a-z] )

}xi;

This is intended to be used in the same way as our previous version (for example, it doesn’t have a leading ⌈^⌋ and trailing ⌈$⌋, and has no capturing parentheses), so we’re free to use it as a drop-in replacement. Doing so gives us a stronger $HttpUrl.

Match modes (or lack thereof) are very sticky

qr/···/ supports the core modifiers described on page 292. Once a regex object is built, the match modes of the regex it represents can’t be changed, even if that regex object is used inside a subsequent m/···/ that has its own modifiers. For example, the following does not work:

my $WordRegex = qr/\b \w+ \b/; # Oops, missing the /x modifier!

*

*

*

if ($text =~ m/^($WordRegex)/x) {

print "found word at start of text: $1\n";

}

The /x modifiers are used here ostensibly to modify how $WordRegex is applied, but this does not work because the modifiers (or lack thereof) are locked in by the qr/···/ when $WordRegex is created. So, the appropriate modifiers must be used at that time.

Here’s a working version of the previous example:

my $WordRegex = qr/\b \w+ \b/x; # This works!

*

*

*

if ($text =~ m/^($WordRegex)/) {

print "found word at start of text: $1\n";

}

Now, contrast the original snippet with the following:

my $WordRegex = '\b \w+ \b'; # Normal string assignment

*

*

*

if ($text =~ m/^($WordRegex)/x) {

print "found word at start of text: $1\n";

}

Unlike the original, this one works even though no modifiers are associated with $WordRegex when it is created. That’s because in this case, $WordRegex is a normal variable holding a simple string that is interpolated into the m/···/ regex literal. Building up a regex in a string is much less convenient than using regex objects, for a variety of reasons, including the problem in this case of having to remember that this $WordRegex must be applied with /x to be useful.

Actually, you can solve that problem even when using strings by putting the regex into a mode-modified span ( 135) when creating the string:

135) when creating the string:

my $WordRegex = '(?x:\b \w+ \b)'; # Normal string assignment

*

*

*

if ($text =~ m/^($WordRegex)/) {

print "found word at start of text: $1\n";

}

In this case, after the m/···/ regex literal interpolates the string, the regex engine is presented with ⌈^{(?x:\b•\w+•\b))⌋, which works the way we want.

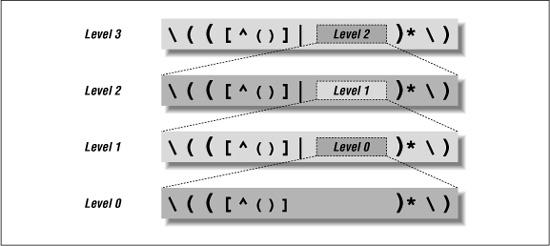

In fact, this is what logically happens when a regex object is created, except that a regex object always explicitly defines the “on” or “off” for each of the /i, /x, /m, and /s modes. Using qr/\b•\w+•\b/x creates ⌈(?x-ism:\b•\w+•\b)⌋. Notice how the mode-modified span,⌈(?x-ism:···)⌋, has /x turned on, while /i, /s, and /m are turned off. Thus, qr/···/ always “locks in” each mode, whether given a modifier or not.

Viewing Regex Objects

The previous paragraph talks about how regex objects logically wrap their regular expression with mode-modified spans like ⌈(?x-ism:···)⌋. You can actually see this for yourself, because if you use a regex object where Perl expects a string, Perl kindly gives a textual representation of the regex it represents. For example:

% perl -e 'print qr/\b \w+ \b/x, "\n"'

(?x-ism:\b \w+ \b)

Here’s what we get when we print the $HttpUrl from page 304:

(?ix-sm:

http:// (?ix-sm:

# One or more dot-separated parts···

(?: [a-z0-9]\. | [a-z0-9][-a-z0-9]{0,61}[a-z0-9]\. )*

# Followed by the final suffix part···

(?: com|edu|gov|int|mil|net|org|biz|info|···|aero|[a-z][a-z] )

) \b # hostname

(?:

/ [-a-z0-9R:\@&?=*,.!/~*'%\$]* # Optional path

(?<![.,?!]) # Not allowed to end with [.,?!]

)?

)

The ability to turn a regex object into a string is very useful for debugging.

Using Regex Objects for Efficiency

One of the main reasons to use regex objects is to gain control, for efficiency reasons, of exactly when Perl compiles a regex to an internal form. The general issue of regex compilation was discussed briefly in Chapter 6, but the more complex Perl-related issues, including regex objects, are discussed in “Regex Compilation, the /o Modifier, qr/···/, and Efficiency” ( 348).

348).

The Match Operator

The basic match

$text =~ m/regex/

is the core of Perl regular-expression use. In Perl, a regular-expression match is an operator that takes two operands, a target string operand and a regex operand, and returns a value.

How the match is carried out, and what kind of value is returned, depend on the context the match is used in ( 294), and other factors. The match operator is quite flexible — it can be used to test a regular expression against a string, to pluck data from a string, and even to parse a string part by part in conjunction with other match operators. While powerful, this flexibility can make mastering it more complex. Some areas of concern include:

294), and other factors. The match operator is quite flexible — it can be used to test a regular expression against a string, to pluck data from a string, and even to parse a string part by part in conjunction with other match operators. While powerful, this flexibility can make mastering it more complex. Some areas of concern include:

- How to specify the regex operand

- How to specify match modifiers, and what they mean

- How to specify the target string to match against

- A match’s side effects

- The value returned by a match

- Outside influences that affect the match

The general form of a match is:

StringOperand =~ RegexOperand

There are various shorthand forms, and it’s interesting to note that each part is optional in one shorthand form or another. We’ll see examples of all forms throughout this section.

Match’s Regex Operand

The regex operand can be a regex literal or a regex object. (Actually, it can be a string or any arbitrary expression, but there is little benefit to that.) If a regex literal is used, match modifiers may also be specified.

Using a regex literal

The regex operand is most often a regex literal within m/···/ or just /···/. The leading m is optional if the delimiters for the regex literal are forward slashes or question marks (delimiters of question marks are special, discussed in a bit). For consistency, I prefer to always use the m, even when it’s not required. As described earlier, you can choose your own delimiters if the m is present ( 291).

291).

When using a regex literal, you can use any of the core modifiers described on page 292. The match operator also supports two additional modifiers, /g and /c, discussed in a bit.

Using a regex object

The regex operand can also be a regex object, created with qr/···/. For example:

my $regex = qr/regex/;

*

*

*

if ($text =~ $regex) {

*

*

*

You can use m/···/ with a regex object. As a special case, if the only thing within the “regex literal” is the interpolation of a regex object, it’s exactly the same as using the regex object alone. This example’s if can be written as:

if ($text =~ m/$regex/) {

*

*

*

This is convenient because it perhaps looks more familiar, and also allows you to use the /g modifier with a regex object. (You can use the other modifiers that m/···/ supports as well, but they’re meaningless in this case because they can never override the modes locked in a regex object  304.)

304.)

The default regex

If no regex is given, such as with m// (or with m/$SomeVar/ where the variable $SomeVar is empty or undefined), Perl reuses the regular expression most recently used successfully within the enclosing dynamic scope. This used to be useful for efficiency reasons, but is now obsolete with the advent of regex objects ( 303).

303).

Special match-once ?···?

In addition to the special cases for the regex-literal delimiters described earlier, the match operator treats the question mark as a special delimiter. The use of a question mark as the delimiter (as with m?···?) enables a rather esoteric feature such that after the successfully m?···? matches once, it cannot match again until the function reset is called in the same package. Quoting from the Perl Version 1 manual page, this features was “a useful optimization when you only want to see the first occurrence of something in each of a set of files,” but for whatever reason, I have never seen it used in modern Perl.

The question mark delimiters are a special case like the forward slash delimiters, in that the m is optional: ?···? by itself is treated as m?···?.

Specifying the Match Target Operand

The normal way to indicate “this is the string to search” is using =~, as with $text =~ m/···/. Remember that =~ is not an assignment operator, nor is it a comparison operator. It is merely a funny-looking way of linking the match operator with one of its operands. (The notation was adapted from awk.)

Since the whole “expr =~ m/···/” is an expression itself, you can use it wherever an expression is allowed. Some examples (each separated by a wavy line):

$text =~ m/···/; # Just do it, presumably, for the side effects.

---------------------------

if ($text =~ m/··· /) {

# Do code if match is successful

*

*

*

---------------------------

$result = ( $text =~ m/··· / ); # Set $result to result of match against $text

$result = $text =~ m/··· / ; # Same thing; =~ has higher precedence than =

---------------------------

$copy = $text; # Copy $text to $copy ...

$copy =~ m/··· /; # ... and perform match on $copy

( $copy = $text ) =~ m/··· /; # Same thing in one expression

The default target

If the target string is the variable $_, you can omit the “$_ =~” parts altogether. In other words, the default target operand is $_.

$text =~ m/regex/;

means “Apply regex to the text in $text, ignoring the return value but doing the side effects.” If you forget the ‘~’, the resulting

$text = m/regex/;

becomes “Apply regex to the text in $_, do the side effects, and return a true or false value that is then assigned to $text.” In other words, the following are the same:

$text = m/regex/;

$text = ($_ =~ m/regex/);

Using the default target string can be convenient when combined with other constructs that have the same default (as many do). For example, this is a common idiom:

while (<>)

{

if (m/···/) {

*

*

*

} elsif (m/···/) {

*

*

*

In general, though, relying on default operands can make your code less approachable by less experienced programmers.

Negating the sense of the match

You can also use !~ instead of =~ to logically negate the sense of the return value. (Return values and side effects are discussed soon, but with !~, the return value is always a simple true or false value.) The following are identical:

if ($text !~ m/···/)

if (not $text =~ m/···/)

unless ($text =~ m/···/)

Personally, I prefer the middle form. With any of them, the normal side effects, such as the setting of $1 and the like, still happen. !~ is merely a convenience in an “if this doesn’t match” situation.

Different Uses of the Match Operator

You can always use the match operator as if it returns a simple true/false indicating the success of the match, but there are ways you can get additional information about a successful match, and to work in conjunction with other match operators. How the match operator works depends primarily on the context in which it’s used ( 294), and whether the

294), and whether the /g modifier has been applied.

Normal “does this match?”—scalar context without /g

In a scalar context, such as the test of an if, the match operator returns a simple true or false:

if ($target =~ m/···/) {

# ... processing after successful match ...

*

*

*

} else {

# ... processing after unsuccessful match ...

*

*

*

}

You can also assign the result to a scalar for inspection later:

my $success = $target =~ m/···/;

*

*

*

if ($success) {

*

*

*

}

Normal “pluck data from a string”—list context, without /g

A list context without /g is the normal way to pluck information from a string. The return value is a list with an element for each set of capturing parentheses in the regex. A simple example is processing a date of the form 69/8/31, using:

my ($year, $month, $day) = $date =~ m{^ (\d+) / (\d+) / (\d+) $}x;

The three matched numbers are then available in the three variables (and $1, $2, and $3 as well). There is one element in the return-value list for each set of capturing parentheses, or an empty list upon failure.

It is possible for a set of capturing parentheses to not participate in the final success of a match. For example, one of the sets in m/(this)|(that)/ is guaranteed not to be part of the match. Such sets return the undefined value undef. If there are no sets of capturing parentheses to begin with, a successful list-context match without /g returns the list (1).

A list context can be provided in a number of ways, including assigning the results to an array, as with:

my @parts = $text =~ m/^(\d+)-(\d+)-(\d+)$/;

If you’re assigning to just one scalar variable, take care to provide a list context to the match if you want the captured parts instead of just a Boolean indicating the success. Compare the following tests:

my ($word) = $text =~ m/(\w+)/;

my $success = $text =~ m/(\w+)/;

The parentheses around the variable in the first example cause its my to provide a list context to the assignment (in this case, to the match). The lack of parentheses in the second example provides a scalar context to the match, so $success merely gets a true/false result.

This example shows a convenient idiom:

if ( my ($year, $month, $day) = $date =~ m{^ (\d+) / (\d+) / (\d+) $}x ) {

# Process for when we have a match: $year and such are available

} else {

# here if no match ...

}

The match is in a list context (provided by the “my (···) =”), so the list of variables is assigned their respective $1, $2, etc., if the match is successful. However, once that’s done, since the whole combination is in the scalar context provided by the if conditional, Perl must contort the list to a scalar. To do that, it takes the number of items in the list, which is conveniently zero if the match wasn’t successful, and non-zero (i.e., true) if it was.

“Pluck all matches”–list context, with the /g modifier

This useful construct returns a list of all text matched within capturing parentheses (or if there are no capturing parentheses, the text matched by the whole expression), not only for one match, as in the previous section, but for all matches in the string.

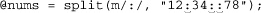

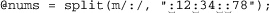

A simple example is the following, to fetch all integers in a string:

my @nums = $text =~ m/\d+/g;

If $text contains an IP address like ‘64.156.215.240’, @nums then receives four elements, ‘64’, ‘156’, ‘215’, and ‘240’. Combined with other constructs, here’s an easy way to turn an IP address into an eight-digit hexadecimal number such as ‘409cd7f0’, which might be convenient for creating compact log files:

my $hex_ip = join '', map { sprintf("%02x", $_) } $ip =~ m/\d+/g;

You can convert it back with a similar technique:

my $ip = join '.', map { hex($_) } $hex_ip =~ m/../g

As another example, to match all floating-point numbers on a line, you might use:

my @nums = $text =~ m/\d+(?:\.\d+)?|\.\d+/g;

The use of non-capturing parentheses here is very important, since adding capturing ones changes what is returned. Here’s an example showing how one set of capturing parentheses can be useful:

my @Tags = $Html =~ m/<(\w+)/g;

This sets @Tags to the list of HTML tags, in order, found in $Html, assuming it contains no stray ‘<’ characters.

Here’s an example with multiple sets of capturing parentheses: consider having the entire text of a Unix mailbox alias file in a single string, where logical lines look like:

alias Jeff jfriedl@regex.info

alias Perlbug perl5-porters@perl.org

alias Prez president@whitehouse.gov

To pluck an alias and full address from one of the logical lines, you can use m/^alias\s+(\S+)\s+(.+)/m (without /g). In a list context, this returns a list of two elements, such as ('Jeff', 'jfriedl@regex.info'). Now, to match all such sets, add /g. This returns a list like:

( 'Jeff', 'jfriedl@regex.info', 'Perlbug',

'perl5-porters@perl.org', 'Prez', 'president@whitehouse.gov' )

If the list happens to fit a key/value pair pattern as in this example, you can actually assign it directly to an associative array. After running

my %alias = $text =~ m/~alias\s+(\S+)\s+(.+)/mg;

you can access the full address of ‘Jeff’ with $alias{Jeff}.

Iterative Matching: Scalar Context, with /g

A scalar-context m/···/g is a special construct quite different from the others. Like a normal m/···/, it does just one match, but like a list-context m/···/g, it pays attention to where previous matches occurred. Each time a scalar-context m/···/g is reached, such as in a loop, it finds the “next” match. If it fails, it resets the “current position,” causing the next application to start again at the beginning of the string.

Here’s a simple example:

$text = "WOW! This is a SILLY test.";

$text =~ m/\b([a-z]+\b)/g;

print "The first all-lowercase word: $1\n";

$text =~ m/\b([A-Z]+\b)/g;

print "The subsequent all-uppercase word: $1\n";

With both scalar matches using the /g modifier, it results in:

The first all-lowercase word: is

The subsequent all-uppercase word: SILLY

The two scalar-/g matches work together: the first sets the “current position” to just after the matched lowercase word, and the second picks up from there to find the first uppercase word that follows. The /g is required for either match to pay attention to the “current position,” so if either didn’t have /g, the second line would refer to ‘WOW’.

A scalar context /g match is quite convenient as the conditional of a while loop. Consider:

while ($ConfigData =~ m/^(\w+)=(.*)/mg) {

my($key, $value) = ($1, $2);

*

*

*

}

All matches are eventually found, but the body of the while loop is executed between the matches (well, after each match). Once an attempt fails, the result is false and the while loop finishes. Also, upon failure, the /g state is reset, which means that the next /g match starts over at the start of the string.

Compare

while ($text =~ m/(\d+)/) { # dangerous!

print "found: $1\n";

}

and:

while ($text =~ m/(\d+)/g) {

print "found: $1\n";

}

The only difference is /g, but it’s a huge difference. If $text contained, say, our earlier IP example, the second prints what we want:

found: 64

found: 156

found: 215

found: 240

The first, however, prints “found: 64” over and over, forever. Without the /g, the match is simply “find the first ⌈(\d+)⌋ in $text,” which is ‘64’ no matter how many times it’s checked. Adding the /g to the scalar-context match turns it into “find the next ⌈(\d+)⌋ in $text,” which finds each number in turn.

The “current match location” and the pos() function

Every string in Perl has associated with it a “current match location” at which the transmission first attempts the match. It’s a property of the string, and not associated with any particular regular expression. When a string is created or modified, the “current match location” starts out at the beginning of the string, but when a /g match is successful, it’s left at the location where the match ended. The next time a /g match is applied to the string, the match begins inspecting the string at that same “current match location.”

You have access to the target string’s “current match location” via the pos(···) function. For example:

my $ip = "64.156.215.240";

while ($ip =~ m/(\d+)/g) {

printf "found '$1' ending at location %d\n", pos($ip);

}

This produces:

found '64' ending at location 2

found '156' ending at location 6

found '215' ending at location 10

found '240' ending at location 14

(Remember, string indices are zero-based, so “location 2” is just before the 3rd character into the string.) After a successful /g match, $+[0] (the first element of @+  302) is the same as the pos of the target string.

302) is the same as the pos of the target string.

The default argument to the pos() function is the same default argument for the match operator: the $_ variable.

Pre-setting a string’s pos

The real power of pos() is that you can write to it, to tell the regex engine where to start the next match (if that next match uses /g, of course). For example, the web server logs I worked with at Yahoo! were in a custom format containing 32 bytes of fixed-width data, followed by the page being requested, followed by other information. One way to pick out the page is to use ⌈^.{32}⌋ to skip over the fixed-width data:

if ($logline =~ m/^.{32}(\S+)/) {

$RequestedPage = $1;

}

This brute-force method isn’t elegant, and forces the regex engine to work to skip the first 32 bytes. That’s less efficient and less clear than doing it explicitly ourself:

pos($logline) = 32; # The page starts at the 32nd character, so start the next match there . . .

if ($logline =~ m/(\S+)/g) {

$RequestedPage = $1;

}

This is better, but isn’t quite the same. It has the regex start where we want it to start, but doesn’t require a match at that position the way the original does. If for some reason the 32nd character can’t be matched by ⌈\S⌋, the original version correctly fails, but the new version, without anything to anchor it to a particular position in the string, is subject to the transmission’s bump-along. Thus, it could return, in error, a match of ⌈\S+⌋ from later in the string. Luckily, the next section shows that this is an easy problem to fix.

Using \G

⌈\G⌋ is the “anchor to where the previous match ended” metacharacter. It’s exactly what we need to solve the problem in the previous section:

pos($logline) = 32; # The page starts at the 32nd character, so start the next match there . . .

if ($logline =~ m/\G(\S+)/g) {

$RequestedPage = $1;

}

⌈\G⌋ tells the transmission “don’t bump-along with this regex — if you can’t match successfully right away, fail.”

There are discussions of ⌈\G⌋ in previous chapters: see the general discussion in Chapter 3 ( 130), and the extended example in Chapter 5 (

130), and the extended example in Chapter 5 ( 212).

212).

Note that Perl’s ⌈\G⌋ is restricted in that it works predictably only when it is the first thing in the regex, and there is no top-level alternation. For example, in Chapter 6 when the CSV example is being optimized ( 271), the regex begins with ⌈

271), the regex begins with ⌈\G(?: ^ | , )···⌋. Because there’s no need to check for ⌈\G⌋ if the more restrictive ⌈^⌋ matches, you might be tempted to change this to ⌈(?: ^| \G,)···⌋. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work in Perl; the results are unpredictable.†

“Tag-team” matching with /gc

Normally, a failing m/···/g match attempt resets the target string’s pos to the start of the string, but adding the /c modifier to /g introduces a special twist, causing a failing match to not reset the target’s pos. (/c is never used without /g, so I tend to refer to it as /gc.)

m/····/gc is most commonly used in conjunction with ⌈\G⌋ to create a “lexer” that tokenizes a string into its component parts. Here’s a simple example to tokenize the HTML in variable $html:

while (not $html =~ m/\G\z/gc) # While we haven't worked to the end . . .

{

if ($html =~ m/\G( <[^>]+> )/xgc) { print "TAG: $1\n" }

elsif ($html =~ m/\G( &\w+; )/xgc) { print "NAMED ENTITY: $1\n" }

elsif ($html =~ m/\G( &\#\d+; )/xgc) { print "NUMERIC ENTITY: $1\n" }

elsif ($html =~ m/\G( [^<>&\n]+ )/xgc) { print "TEXT: $1\n" }

elsif ($html =~ m/\G \n /xgc) { print "NEWLINE\n" }

elsif ($html =~ m/\G( . )/xgc) { print "ILLEGAL CHAR: $1\n" }

else {

die "$0: oops, this shouldn't happen!";

}

}

The bold part of each regex matches one type of HTML construct. Each is checked in turn starting from the current position (due to /gc), but can match only at the current position (due to ⌈\G⌋). The regexes are checked in order until the construct at that current position has been found and reported. This leaves $html’s pos at the start of the next token, which is found during the next iteration of the loop.

The loop ends when m/\G\z/gc is able to match, which is when the current position (⌈\G⌋) has worked its way to the very end of the string (⌈\z⌋).

An important aspect of this approach is that one of the tests must match each time through the loop. If one doesn’t (and if we don’t abort), there would be an infinite loop, since nothing would be advancing or resetting $html’s pos. This example has a final else clause that will never be invoked as the program stands now, but if we were to edit the program (as we will soon), we could perhaps introduce a mistake, so keeping the else clause is prudent. As it is now, if the data contains a sequence we haven’t planned for (such as ‘<>’), it generates one warning message per unexpected character.

Another important aspect of this approach is the ordering of the checks, such as the placement of ⌈\G(.)⌋ as the last check. Or, consider extending this application to recognize <script> blocks with:

$html =~ m/\G ( <script[^>]*>.*?</script>)/xgcsi

(Wow, we’ve used five modifiers!) To work properly, this must be inserted into the program before the currently-first ⌈<[^>]+>⌋. Otherwise, ⌈<[^>]+>⌋ would match the opening <script> tag “out from under” us.

There’s a somewhat more advanced example of /gc in Chapter 3 ( 132).

132).

Pos-related summary

Here’s a summary of how the match operator interacts with the target string’s pos:

Type of match |

Where match starts |

|

|

|

start of string ( |

reset to |

reset to |

|

starts at target’s |

set to end of match |

reset to |

|

starts at target’s |

set to end of match |

left unchanged |

Also, modifying a string in any way causes its pos to be reset to undef (which is the initial value, meaning the start of the string).

The Match Operator’s Environmental Relations

The following sections summarize what we’ve seen about how the match operator influences the Perl environment, and vice versa.

The match operator’s side effects

Often, the side effects of a successful match are more important than the actual return value. In fact, it is quite common to use the match operator in a void context (i.e., in such a way that the return value isn’t even inspected), just to obtain the side effects. (In such a case, it acts as if given a scalar context.) The following summarizes the side effects of a successful match attempt:

- After-match variables like

$1and@+are set for the remainder of the current scope ( 299).

299). - The default regex is set for the remainder of the current scope (

308).

308). - If

m?···?matches, it (the specificm?···?operator) is marked as unmatchable, at least until the next call ofresetin the same package ( 308).

308).

Again, these side effects occur only with a match that is successful—an unsuccessful match attempt has no influence on them. However, the following side effects happen with any match attempt:

- pos is set or reset for the target string (

313).

313). - If

/ois used, the regex is “fused” to the operator so that re-evaluation does not occur ( 352).

352).

Outside influences on the match operator

What a match operator does is influenced by more than just its operands and modifiers. This list summarizes the outside influences on the match operator:

context

The context that a match operator is applied in (scalar, array, or void) has a large influence on how the match is performed, as well as on its return value and side effects.

pos(···)

The pos of the target string (set explicitly or implicitly by a previous match) indicates where in the string the next /g-governed match should begin. It is also where ⌈\G⌋ matches.

default regex

The default regex is used if the provided regex is empty ( 308).

308).

study

It has no effect on what is matched or returned, but if the target string has been studied, the match might be faster (or slower). See “The Study Function” ( 359).

359).

m?···? and reset

The invisible “has/hasn’t matched” status of m?···? operators is set when m?···? matches or reset is called ( 308).

308).

Keeping your mind in context (and context in mind)

Before leaving the match operator, I’ll put a question to you. Particularly when changing among the while, if, and foreach control constructs, you really need to keep your wits about you. What do you expect the following to print?

while ("Larry Curly Moe" =~ m/\w+/g) {

print "WHILE stooge is $&.\n";

}

print "\n";

if ("Larry Curly Moe" =~ m/\w+/g) {

print "IF stooge is $&.\n";

}

print "\n";

foreach ("Larry Curly Moe" =~ m/\w+/g) {

print "FOREACH stooge is $&.\n";

}

It’s a bit tricky. ![]() Turn the page to check your answer.

Turn the page to check your answer.

The Substitution Operator

Perl’s substitution operator s/···/···/ extends a match to a full match-and-replace. The general form is:

$text =~ s/regex/replacement/modifiers

In short, the text first matched by the regex operand is replaced by the value of the replacement operand. If the /g modifier is used, the regex is repeatedly applied to the text following the match, with additional matched text replaced as well.

As with the match operator, the target text operand and the connecting =~ are optional if the target is the variable $_. But unlike the match operator’s m, the substitution’s s is never optional.