2

Extended Introductory Examples

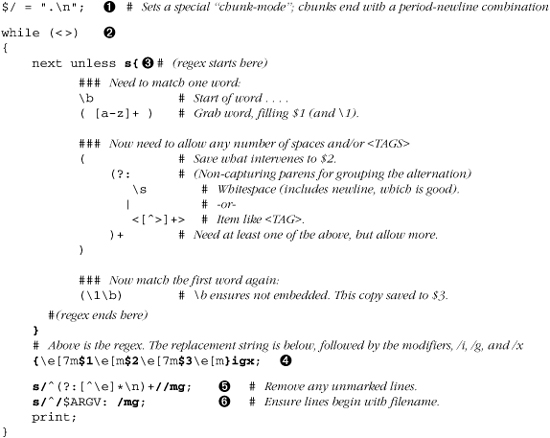

Remember the doubled-word problem from the first chapter? I said that a full solution could be written in just a few lines in a language like Perl. Such a solution might look like:

$/ = ".\n";

while (<>) {

next if !s/\b([a-z]+)((?:\s|<[^>]+>)+)(\1\b)/\e[7m$1\e[m$2\e[7m$3\e[m/ig;

s/^(?:[^\e]*\n)+//mg; # Remove any unmarked lines.

s/^/$ARGV: /mg; # Ensure lines begin with filename.

print;

}

Yup, that’s the whole program.

Even if you’re familiar with Perl, I don’t expect you to understand it (yet!). Rather, I wanted to show an example beyond what egrep can allow, and to whet your appetite for the real power of regular expressions.

Most of this program’s work revolves around its three regular expressions:

- ⌈

\b([a-z]+)((?:\s|<[^>]+>)+)(\1\b)⌋ - ⌈

^(?:[^\e]*\n)+⌋ - ⌈

^⌋

Though this is a Perl example, these three regular expressions can be used verbatim (or with only a few changes) in many other languages, including PHP, Python, Java, VB.NET, Tcl, and more.

Now, looking at these, that last ⌈^⌋ is certainly recognizable, but the other expressions have items unfamiliar to our egrep-only experience. This is because Perl’s regex flavor is not the same as egrep’s. Some of the notations are different, and Perl (as well as most modern tools) tends to provide a much richer set of metacharacters than egrep. We’ll see many examples throughout this chapter.

About the Examples

This chapter takes a few sample problems — validating user input; working with email headers; converting plain text to HTML — and wanders through the regular expression landscape with them. As I develop them, I’ll “think out loud” to offer a few insights into the thought processes that go into crafting a regex. During our journey, we’ll see some constructs and features that egrep doesn’t have, and we’ll take plenty of side trips to look at other important concepts as well.

Toward the end of this chapter, and in subsequent chapters, I’ll show examples in a variety of languages including PHP, Java, and VB.NET, but the examples throughout most of this chapter are in Perl. Any of these languages, and most others for that matter, allow you to employ regular expressions in much more complex ways than egrep, so using any of them for the examples would allow us to see interesting things. I choose to start with Perl primarily because it has the most ingrained, easily accessible regex support among the popular languages. Also, Perl provides many other concise data-handling constructs that alleviate much of the “dirty work” of our example tasks, letting us concentrate on regular expressions.

Just to quickly demonstrate some of these powers, recall the file-check example from page 2, where I needed to ensure that each file contained ‘ResetSize’ exactly as many times as ‘SetSize’. The utility I used was Perl, and the command was:

% perl -One 'print "$ARGV\n" if s/ResetSize//ig != s/SetSize//ig' *

(I don’t expect that you understand this yet — I hope merely that you’ll be impressed with the brevity of the solution.)

I like Perl, but it’s important not to get too caught up in its trappings here. Remember, this chapter concentrates on regular expressions. As an analogy, consider the words of a computer science professor in a first-year course: “You’re going to learn computer-science concepts here, but we’ll use Pascal to show you.”†

Since this chapter doesn’t assume that you know Perl, I’ll be sure to introduce enough to make the examples understandable. (Chapter 7, which looks at all the nitty-gritty details of Perl, does assume some basic knowledge.) Even if you have experience with a variety of programming languages, normal Perl may seem quite odd at first glance because its syntax is very compact and its semantics thick. In the interest of clarity, I won’t take advantage of much that Perl has to offer, instead presenting programs in a more generic, almost pseudo-code style. While not “bad,” the examples are not the best models of The Perl Way of programming. But, we will see some great uses of regular expressions.

A Short Introduction to Perl

Perl is a powerful scripting language first developed in the late 1980s, drawing ideas from many other programming languages and tools. Many of its concepts of text handling and regular expressions are derived from two specialized languages called awk and sed, both of which are quite different from a “traditional” language such as C or Pascal.

Perl is available for many platforms, including DOS/Windows, MacOS, OS/2, VMS, and Unix. It has a powerful bent toward text handling, and is a particularly common tool used for Web-related processing. See www.perl.com for information on how to get a copy of Perl for your system.

This book addresses the Perl language as of Version 5.8, but the examples in this chapter are written to work with versions as early as Version 5.005.

Let’s look at a simple example:

$celsius = 30;

$fahrenheit = ($celsius * 9 / 5) + 32; # calculate Fahrenheit

print "$celsius C is $fahrenheit F.\n"; # report both temperatures

When executed, this produces:

30 C is 86 F.

Simple variables, such as $fahrenheit and $celsius, always begin with a dollar sign, and can hold a number or any amount of text. (In this example, only numbers are used.) Comments begin with # and continue for the rest of the line.

If you’re used to languages such as C, C#, Java, or VB.NET, perhaps most surprising is that in Perl, variables can appear within a double-quoted string. With the string “$celsius C is $fahrenheit F.\n”, each variable is replaced by its value. In this case, the resulting string is then printed. (The \n represents a newline.)

Perl offers control structures similar to other popular languages:

$celsius = 20;

while ($celsius <= 45)

{

$fahrenheit = ($celsius * 9 / 5) + 32; # calculate Fahrenheit

print "$celsius C is $fahrenheit F.\n";

$celsius = $celsius + 5;

}

The body of the code controlled by the while loop is executed repeatedly so long as the condition (the $celsius <= 45 in this case) is true. Putting this into a file, say temps, we can run it directly from the command line.

% perl -w temps

20 C is 68 F.

25 C is 77 F.

30 C is 86 F.

35 C is 95 F.

40 C is 104 F.

45 C is 113 F.

The -w option is neither necessary nor has anything directly to do with regular expressions. It tells Perl to check your program more carefully and issue warnings about items it thinks to be dubious, (such as using uninitialized variables and the like — variables do not normally need to be predeclared in Perl). I use it here merely because it is good practice to always do so.

Well, that’s it for the general introduction to Perl. We’ll move on now to see how Perl allows us to use regular expressions.

Matching Text with Regular Expressions

Perl uses regular expressions in many ways, the simplest being to check if a regex matches text (or some part thereof) held in a variable. This snippet checks the string held in variable $reply and reports whether it contains only digits:

if ($reply =~ m/^[0-9]+$/) {

print "only digits\n";

} else {

print "not only digits\n";

}

The mechanics of the first line might seem a bit strange: the regular expression is ⌈^[0-9]+$⌋, while the surrounding m/···/ tells Perl what to do with it. The m means to attempt a regular expression match, while the slashes delimit the regex itself.† The preceding =~ links m/···/ with the string to be searched, in this case the contents of the variable $reply.

Don’t confuse =~ with = or ==. The operator == tests whether two numbers are the same. (The operator eq, as we will soon see, is used to test whether two strings are the same.) The = operator is used to assign a value to a variable, as with $celsius = 20. Finally, =~ links a regex search with the target string to be searched. In the example, the search is m/^[0-9]+$/ and the target is $reply. Other languages approach this differently, and we’ll see examples in the next chapter.

It might be convenient to read =~ as “matches,” such that

if ($reply =~ m/^[0-9]+$/)

becomes:

if the text contained in the variable $reply matches the regex ⌈^[0-9]+$⌋, then ...

The whole result of $reply =~ m/^[0-9]+$/ is a true value if the ⌈^[0-9]+$⌋ matches the string held in $reply, a false value otherwise. The if uses this true or false value to decide which message to print.

Note that a test such as $reply =~ m/[0-9]+/ (the same as before except the wrapping caret and dollar have been removed) would be true if $reply contained at least one digit anywhere. The surrounding ⌈^···$⌋ ensures that the entire $reply contains only digits.

Let’s combine the last two examples. We’ll prompt the user to enter a value, accept that value, and then verify it with a regular expression to make sure it’s a number. If it is, we calculate and display the Fahrenheit equivalent. Otherwise, we issue a warning message:

print "Enter a temperature in Celsius:\n";

$celsius = <STDIN>; # this reads one line from the user

chomp($celsius); # this removes the ending newline from $celsius

if ($celsius =~ m/^[0-9]+$/) {

$fahrenheit = ($celsius * 9 / 5) + 32; # calculate Fahrenheit

print "$celsius C is $fahrenheit F\n";

} else {

print "Expecting a number, so I don't understand \"$celsius\".\n";

}

Notice in the last print how we escaped the quotes to be printed, to distinguish them from the quotes that delimit the string? As with literal strings in most languages, there are occasions to escape some items, and this is very similar to escaping a metacharacter in a regex. The relationship between a string and a regex isn’t quite as important with Perl, but is extremely important with languages like Java, Python, and the like. The section “A short aside — metacharacters galore” ( 44) discusses this in a bit more detail. (One notable exception is VB.NET, which requires ‘

44) discusses this in a bit more detail. (One notable exception is VB.NET, which requires ‘""’ rather than ‘\"’ to get a double quote into a string literal.)

If we put this program into the file c2f, we might run it and see:

% perl -w c2f

Enter a temperature in Celsius:

22

22 C is 71.599999999999994316 F

Oops. As it turns out (at least on some systems), Perl’s simple print is not always so good when it comes to floating-point numbers.

I don’t want to get bogged down describing all the details of Perl in this chapter, so I’ll just say without further comment that you can use printf (“print formatted”) to make this look better:

printf "%.2f C is %.2f F\n", $celsius, $fahrenheit;

The printf function is similar to the C language’s printf, or the format of Pascal, Tcl, elisp, and Python. It doesn’t change the values of the variables, but merely how they are displayed. The result is now much nicer:

Enter a temperature in Celsius:

22

22.00 C is 71.60 F

Toward a More Real-World Example

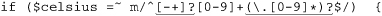

Let’s extend this example to allow negative and fractional temperature values. The math part of the program is fine — Perl normally makes no distinction between integers and floating-point numbers. We do, however, need to modify the regex to let negative and floating-point values pass. We can insert a leading ⌈-?⌋ to allow a leading minus sign. In fact, we may as well make that ⌈[-+] ?⌋ to allow a leading plus sign, too.

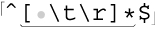

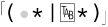

To allow an optional decimal part, we add ⌈(\.[0-9]*)?⌋. The escaped dot matches a literal period, so ⌈\.[0-9]*⌋ is used to match a period followed by any number of optional digits. Since ⌈\.[0-9]*⌋ is enclosed by ⌈(···)?⌋, the whole subexpression becomes optional. (Realize that this is very different from  , which incorrectly allows additional digits to match even if ⌈

, which incorrectly allows additional digits to match even if ⌈\.⌋ does not match.)

Putting this all together, we get

as our check line. It allows numbers such as 32, -3.723, and +98.6. It is actually not quite perfect: it doesn’t allow a number that begins with a decimal point (such as .357). Of course, the user can just add a leading zero to allow it to match (e.g., 0.357), so I don’t consider it a major shortcoming. This floating-point problem can have some interesting twists, and I look at it in detail in Chapter 5 ( 194).

194).

Side Effects of a Successful Match

Let’s extend the example further to allow someone to enter a value in either Fahrenheit or Celsius. We’ll have the user append a C or F to the temperature entered. To let this pass our regular expression, we can simply add ⌈[CF]⌋ after the expression to match a number, but we still need to change the rest of the program to recognize which kind of temperature was entered, and to compute the other.

In Chapter 1, we saw how some versions of egrep support ⌈\1⌋, ⌈\2⌋, ⌈\3⌋, etc. as metacharacters to refer to the text matched by parenthesized subexpressions earlier within the regex ( 21). Perl and most other modern regex-endowed languages support these as well, but also provide a way to refer to the text matched by parenthesized subexpressions from code outside of the regular expression, after a match has been successfully completed.

21). Perl and most other modern regex-endowed languages support these as well, but also provide a way to refer to the text matched by parenthesized subexpressions from code outside of the regular expression, after a match has been successfully completed.

We’ll see examples of how other languages do this in the next chapter ( 137), but Perl provides the access via the variables

137), but Perl provides the access via the variables $1, $2, $3, etc., which refer to the text matched by the first, second, third, etc., parenthesized subexpression. As odd as it might seem, these are variables. The variable names just happen to be numbers. Perl sets them every time the application of a regex is successful.

To summarize, use the metacharacter ⌈\1⌋ within the regular expression to refer to some text matched earlier during the same match attempt, and use the variable $1 in subsequent code to refer to that same text after the match has been successfully completed.

To keep the example uncluttered and focus on what’s new, I’ll remove the fractional-value part of the regex for now, but we’ll return to it again soon. So, to see $1 in action, compare:

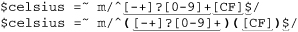

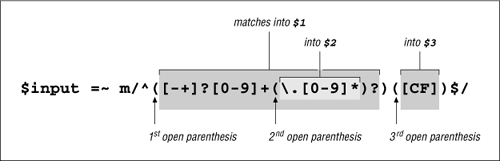

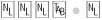

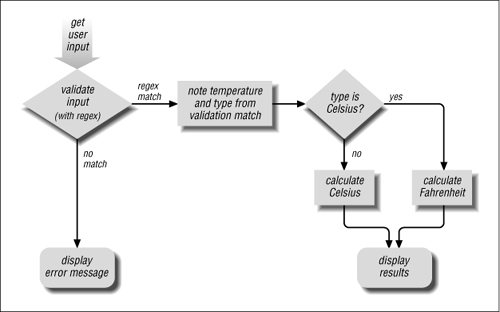

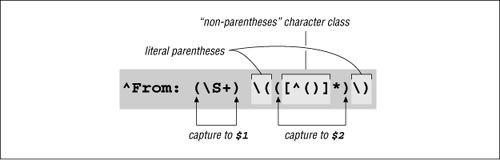

Do the added parentheses change the meaning of the expression? Well, to answer that, we need to know whether they provide grouping for star or other quantifiers, or provide an enclosure for ⌈|⌋. The answer is no on both counts, so what matches remains unchanged. However, they do enclose two subexpressions that match “interesting” parts of the string we are checking. As Figure 2-1 illustrates, $1 will receive the number entered, and $2 will receive the C or F entered. Referring to the flowchart in Figure 2-2 on the next page, we see that this allows us to easily decide how to proceed after the match.

Figure 2-1: Capturing parentheses

Figure 2-2: Temperature-conversion program’s logic flow

Temperature-conversion program

print "Enter a temperature (e.g., 32F, 100C):\n";

$input = <STDIN>; # This reads one line from the user.

chomp($input); # This removes the ending newline from $input.

if ($input =~ m/^([-+]?[0-9]+)([CF])$/)

{

# If we get in here, we had a match. $1 is the number, $2 is "C" or "F".

$InputNum = $1; # Save to named variables to make the ...

$type = $2; # ... rest of the program easier to read.

if ($type eq "C") { # 'eq' tests if two strings are equal

# The input was Celsius, so calculate Fahrenheit

$celsius = $InputNum;

$fahrenheit = ($celsius * 9 / 5) + 32;

} else {

# If not "C", it must be an "F", so calculate Celsius

$fahrenheit = $InputNum;

$celsius = ($fahrenheit - 32) * 5 / 9;

}

# At this point we have both temperatures, so display the results:

printf "%.2f C is %.2f F\n", $celsius, $fahrenheit;

} else {

# The initial regex did not match, so issue a warning.

print "Expecting a number followed by \"C\" or \"F\",\n";

print "so I don't understand \"$input\".\n";

}

If the program shown on the facing page is named convert, we can use it like this:

% perl -w convert

Enter a temperature (e.g., 32F, 100C):

39F

3.89 C is 39.00 F

% perl -w convert

Enter a temperature (e.g., 32F, 100C):

39C

39.00 C is 102.20 F

% perl -w convert

Enter a temperature (e.g., 32F, 100C):

oops

Expecting a number followed by "C" or "F",

so I don't understand "oops".

Intertwined Regular Expressions

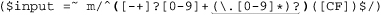

With advanced programming languages like Perl, regex use can become quite intertwined with the logic of the rest of the program. For example, let’s make three useful changes to our program: allow floating-point numbers as we did earlier, allow for the f or c entered to be lowercase, and allow spaces between the number and letter. Once all these changes are done, input such as ‘98.6•f’ will be allowed.

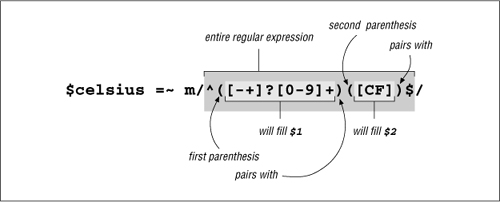

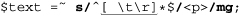

Earlier, we saw how we can allow floating-point numbers by adding ⌈(\.[0-9]*)?⌋ to the expression:

if

Notice that it is added inside the first set of parentheses. Since we use that first set to capture the number to compute, we want to make sure that they capture the fractional portion as well. However, the added set of parentheses, even though ostensibly used only to group for the question mark, also has the side effect of capturing into a variable. Since the opening parenthesis of the pair is the second (from the left), it captures into $2. This is illustrated in Figure 2-3.

Figure 2-3: Nesting parentheses

Figure 2-3 illustrates how closing parentheses nest with opening ones. Adding a set of parentheses earlier in the expression doesn’t influence the meaning of ⌈[CF]⌋ directly, but it does so indirectly because the parentheses surrounding it have now become the third pair. Becoming the third pair means that we need to change the assignment to $type to refer to $3 instead of $2 (but see the sidebar on the facing page for an alternative approach).

Next, allowing spaces between the number and letter is easier. We know that an unadorned space in a regex requires exactly one space in the matched text, so ⌈•*⌋ can be used to allow any number of spaces (but still not require any):

if

This does give a limited amount of flexibility to the user of our program, but since we are trying to make something useful in the real world, let’s construct the regex to also allow for other kinds of whitespace as well. Tabs, for instance, are quite common. Writing  , of course, doesn’t allow for spaces, so we need to construct a character class to match either one:

, of course, doesn’t allow for spaces, so we need to construct a character class to match either one:  .

.

Compare that with  and see if you can recognize how they are fundamentally different?

and see if you can recognize how they are fundamentally different? ![]() After considering this, turn the page to check your thoughts.

After considering this, turn the page to check your thoughts.

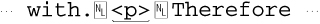

In this book, spaces and tabs are easy to notice because of the • and  typesetting conventions I’ve used. Unfortunately, it is not so on-screen. If you see something like

typesetting conventions I’ve used. Unfortunately, it is not so on-screen. If you see something like [ ]*, you can guess that it is probably a space and a tab, but you can’t be sure until you check. For convenience, Perl regular expressions provide the ⌈\t⌋ metacharacter. It simply matches a tab — its only benefit over a literal tab is that it is visually apparent, so I use it in my expressions. Thus,  becomes ⌈

becomes ⌈[•\t]*⌋.

Some other Perl convenience metacharacters are ⌈\n⌋ (newline), ⌈\f⌋ (ASCII form feed), and ⌈\b⌋ (backspace). Well, actually, ⌈\b⌋ is a backspace in some situations, but in others, it matches a word boundary. How can it be both? The next section tells us.

A short aside—metacharacters galore

We saw \n in earlier examples, but in those cases, it was in a string, not a regular expression. Like most languages, Perl strings have metacharacters of their own, and these are completely distinct from regular expression metacharacters. It is a common mistake for new programmers to get them confused. (VB.NET is a notable language that has very few string metacharacters.) Some of these string metacharacters conveniently look exactly the same as some comparable regex metacharacters. You can use the string metacharacter \t to get a tab into your string, while you can use the regex metacharacter ⌈\t⌋ to insert a tab-matching element into your regex.

The similarity is convenient, but I can’t stress enough how important it is to maintain the distinction between the different types of metacharacters. It may not seem important for such a simple example as \t, but as we’ll later see when looking at numerous different languages and tools, knowing which metacharacters are being used in each situation is extremely important.

We have already seen multiple sets of metacharacters conflict. In Chapter 1, while working with egrep, we generally wrapped our regular expressions in single quotes. The whole egrep command line is written at the command-shell prompt, and the shell recognizes several of its own metacharacters. For example, to the shell, the space is a metacharacter that separates the command from the arguments and the arguments from each other. With many shells, single quotes are metacharacters that tell the shell to not recognize other shell metacharacters in the text between the quotes. (DOS uses double quotes.)

Using the quotes for the shell allows us to use spaces in our regular expression. Without the quotes, the shell would interpret the spaces in its own way instead of passing them through to egrep to interpret in its way. Many shells also recognize metacharacters such as $, *, ?, and so on—characters that we are likely to want to use in a regex.

Now, all this talk about other shell metacharacters and Perl’s string metacharacters has nothing to do with regular expressions themselves, but it has everything to do with using regular expressions in real situations. As we move through this book, we’ll see numerous (sometimes complex) situations where we need to take advantage of multiple levels of simultaneously interacting metacharacters.

And what about this ⌈\b⌋ business? This is a regex thing: in Perl regular expressions, ⌈\b⌋ normally matches a word boundary, but within a character class, it matches a backspace. A word boundary would make no sense as part of a class, so Perl is free to let it mean something else. The warnings in the first chapter about how a character class’s “sub language” is different from the main regex language certainly apply to Perl (and every other regex flavor as well).

Generic “whitespace” with \s

While discussing whitespace, we left off with ⌈[•\t]*⌋. This is fine, but many regex flavors provide a useful shorthand: ⌈\s⌋. While it looks similar to something like ⌈\t⌋ which simply represents a literal tab, the metacharacter ⌈\s⌋ is a shorthand for a whole character class that matches any “whitespace character” This includes (among others) space, tab, newline, and carriage return. With our example, the newline and carriage return don’t really matter one way or the other, but typing ⌈\s*⌋ is easier than ⌈[•\t]*⌋. After a while, you get used to seeing it, and ⌈\s*⌋ becomes easy to read even in complex regular expressions.

Our test now looks like:

Lastly, we want to allow a lowercase letter as well as uppercase. This is as easy as adding the lowercase letters to the class: ⌈[CFcf]⌋. However, I’d like to show another way as well:

The added i is called a modifier, and placing it after the m/···/ instructs Perl to do the match in a case-insensitive manner. It’s not actually part of the regex, but part of the m/···/ syntactic packaging that tells Perl what you want to do (apply a regex), and which regex to do it with (the one between the slashes). We’ve seen this type of thing before, with egrep’s -i option ( 15).

15).

It’s a bit too cumbersome to say “the i modifier” all the time, so normally “/i” is used even though you don’t add an extra / when actually using it. This /i notation is one way to specify modifiers in Perl — in the next chapter, we’ll see other ways to do it in Perl, and also how other languages allow for the same functionality. We’ll also see other modifiers as we move along, including /g (“global match”) and /x (“free-form expressions”) later in this chapter.

Well, we’ve made a lot of changes. Let’s try the new program:

% perl -w convert

Enter a temperature (e.g., 32F, 100C):

32 f

0.00 C is 32.00 F

% perl -w convert

Enter a temperature (e.g., 32F, 100C):

50 c

10.00 C is 50.00 F

Oops! Did you notice that in the second try we thought we were entering 50° Celsius, yet it was interpreted as 50° Fahrenheit? Looking at the program’s logic, do you see why?

Let’s look at that part of the program again:

if ($input =~ m/^([-+]?[0-9]+(\.[0-9]*)?)\s*([CF])$/i)

{

*

*

*

$type = $3; # save to a named variable to make rest of program more readable

if ($type eq "C") { # 'eq' tests if two strings are equal

*

*

*

} else {

*

*

*

Although we modified the regex to allow a lowercase f, we neglected to update the rest of the program appropriately. As it is now, if $type isn’t exactly ‘C', we assume the user entered Fahrenheit. Since we now also allow ‘c’ to mean Celsius, we need to update the $type test:

if ($type eq "C" or $type eq "c") {

Actually, since this is a book on regular expressions, perhaps I should use:

if ($type =~ m/c/i) {

In either case, it now works as we want. The final program is shown below. These examples show how the use of regular expressions can become intertwined with the rest of the program.

Temperature-conversion program – final listing

print "Enter a temperature (e.g., 32F, 100C):\n";

$input = <STDIN>; # This reads one line from the user.

chomp($input); # This removes the ending newline from $input.

if ($input =~ m/^([-+]?[0-9]+(\.[0-9]*)?)\s*([CF])$/i)

{

# If we get in here, we had a match. $1 is the number, $3 is "C" or "F".

$InputNum = $1; # Save to named variables to make the ...

$type = $3; # ... rest of the program easier to read.

if ($type =~ m/c/i) { # Is it "c" or "C"?

# The input was Celsius, so calculate Fahrenheit

$celsius = $InputNum;

$fahrenheit = ($celsius * 9 / 5) + 32;

} else {

# If not "C", it must be an "F", so calculate Celsius

$fahrenheit = $InputNum;

$celsius = ($fahrenheit - 32) * 5 / 9;

}

# At this point we have both temperatures, so display the results:

printf "%.2f C is %.2f F\n", $celsius, $fahrenheit;

} else {

# The initial regex did not match, so issue a warning.

print "Expecting a number followed by \"C\" or \"F\",\n";

print "so I don't understand \"$input\".\n";

}

Intermission

Although we have spent much of this chapter coming up to speed with Perl, we’ve encountered a lot of new information about regexes:

- Most tools have their own particular flavor of regular expressions. Perl’s appear to be of the same general type as egrep’s, but has a richer set of metacharacters. Many other languages, such as Java, Python, the .NET languages, and Tcl, have flavors similar to Perl’s.

- Perl can check a string in a variable against a regex using the construct

$variable =~ m/regex/.Themindicates that a match is requested, while the slashes delimit (and are not part of) the regular expression. The whole test, as a unit, is either true or false. - The concept of metacharacters — characters with special interpretations — is not unique to regular expressions. As discussed earlier about shells and double-quoted strings, multiple contexts often vie for interpretation. Knowing the various contexts (shell, regex, and string, among others), their metacharacters, and how they can interact becomes more important as you learn and use Perl, PHP, Java, Tcl, GNU Emacs, awk, Python, or other advanced languages. (And of course, within regular expressions, character classes have their own mini language with a distinct set of metacharacters.)

- Among the more useful shorthands that Perl and many other flavors of regex provide (some of which we haven’t seen yet) are:

\ta tab character

\na newline character

\ra carriage-return character

\smatches any “whitespace” character (space, tab, newline, formfeed, and such)

\Sanything not ⌈

\s⌋\w⌈

[a-zA-Z0-9_]⌋ (useful as in ⌈\w+⌋, ostensibly to match a word)\Wanything not ⌈

\w⌋, i.e., ⌈[^a-zA-Z0-9_]⌋\d⌈

[0-9]⌋, i.e., a digit\Danything not ⌈

\d⌋, i.e., ⌈[^0-9]⌋ - The

/imodifier makes the test case-insensitive. Although written in prose as “/i” only “i” is actually appended after the match operator’s closing delimiter. - The somewhat unsightly ⌈

(?:···)⌋ non-capturing parentheses can be used for grouping without capturing. - After a successful match, Perl provides the variables

$1, $2, $3,etc., which hold the text matched by their respective ⌈(···)⌋ parenthesized subexpressions in the regex. In concert with these variables, you can use a regex to pluck information from a string. (Other languages provide the same type of information in other ways; we’ll see many examples in the next chapter.)Subexpressions are numbered by counting open parentheses from the left, starting with one. Subexpressions can be nested, as in ⌈

(Washington(•DC)?)⌋. Raw ⌈(···)⌋ parentheses can be intended for grouping only, but as a byproduct, they still capture into one of the special variables.

Modifying Text with Regular Expressions

So far, the examples have centered on finding, and at times, “plucking out” information from a string. Now we look at substitution (also called search and replace), a regex feature that Perl and many tools offer.

As we have seen, $var =~ m/regex/ attempts to match the given regular expression to the text in the given variable, and returns true or false appropriately. The similar construct $var =~ s/regex/replacement/ takes it a step further: if the regex is able to match somewhere in the string held by $var, the text actually matched is replaced by replacement. The regex is the same as with m/···/, but the replacement (between the middle and final slash) is treated as a double-quoted string. This means that you can include references to variables, including $1, $2, and so on to refer to parts of what was just matched.

Thus, with $var =~ s/···/···/ the value of the variable is actually changed. (If there is no match to begin with, no replacement is made and the variable is left unchanged.) For example, if $var contained Jeff•Friedl and we ran

$var =~ s/Jeff/Jeffrey/;

$var would end up with Jeffrey•Friedl. And if we did that again, it would end up with Jeffreyrey•Friedl. To avoid that, perhaps we should use a word-boundary metacharacter. As mentioned in the first chapter, some versions of egrep support ⌈\<⌋ and ⌈\>⌋ for their start-of-word and end-of-word metacharacters. Perl, however, provides the catch-all ⌈\b⌋, which matches either:

$var =~ s/\bJeff\b/Jeffrey/;

Here’s a slightly tricky quiz: like m/···/, the s/···/···/ operation can use modifiers, such as the /i from page 47. (The modifier goes after the replacement.) Practically speaking, what does

$var =~ s/\bJeff\b/Jeff/i;

accomplish? ![]() Flip the page to check your answer.

Flip the page to check your answer.

Example: Form Letter

Let’s look at a rather humorous example that shows the use of a variable in the replacement string. I can imagine a form-letter system that might use a letter template with markers for the parts that must be customized for each letter.

Dear =FIRST=,

You have been chosen to win a brand new =TRINKET=! Free!

Could you use another =TRINKET= in the =FAMILY= household?

Yes =SUCKER=, I bet you could! Just respond by.....

To process this for a particular recipient, you might have the program load:

$given = "Tom";

$family = "Cruise";

$wunderprize = "100% genuine faux diamond";

Once prepared, you could then “fill out the form” with:

$letter =~ s/=FIRST=/$given/g;

$letter =~ s/=FAMILY=/$family/g;

$letter =~ s/=SUCKER=/$given $family/g;

$letter =~ s/=TRINKET=/fabulous $wunderprize/g;

Each substitution’s regex looks for a simple marker, and when found, replaces it with the text wanted in the final message. The replacement part is actually a Perl string in its own right, so it can reference variables, as each of these do. For example, the marked portion of  is interpreted just like the string

is interpreted just like the string "fabulous $wunderprize". If you just had the one letter to generate, you could forego using variables in the replacement string altogether, and just put the desired text directly. But, using this method makes automation possible, such as when reading names from a list.

We haven’t seen the /g “global replacement” modifier yet. It instructs the s/···/···/ to continue trying to find more matches, and make more replacements, after (and from where) the first substitution completes. This is needed if each string we check could contain multiple instances of the text to be replaced, and we want each substitution to replace them all, not just one.

The results are predictable, but rather humorous:

Dear Tom,

You have been chosen to win a brand new fabulous 100% genuine faux diamond! Free!

Could you use another fabulous 100% genuine faux diamond in the Cruise household?

Yes Tom Cruise, I bet you could! Just respond by.....

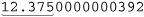

Example: Prettifying a Stock Price

As another example, consider a problem I faced while working on some stock-pricing software with Perl. I was getting prices that looked like “9.0500000037272” The price was obviously 9.05, but because of how a computer represents the number internally, Perl sometimes prints them this way unless special formatting is used. Normally, I would just use printf to display the price with exactly two decimal digits as I did in the temperature-conversion example, but that was not appropriate in this case. At the time, stock prices were still given as fractions, and a price that ended with, say, ⅛, should be shown with three decimals (“.125”), not two.

I boiled down my needs to “always take the first two digits after the decimal point, and take the third digit only if it is not zero. Then, remove any other digits.” The result is that  or the already correct

or the already correct  is returned as “12.375”, yet

is returned as “12.375”, yet  is reduced to “37.50”. Just what I wanted.

is reduced to “37.50”. Just what I wanted.

So, how would we implement this? The variable $price contains the string in question, so let’s use:

$price =~ s/(\.\d\d[1-9]?)d*/$1/

(Reminder: ⌈\d⌋ was introduced on page 49, and matches a digit.)

The initial ⌈\.⌋ causes the match to start at the decimal point. The subsequent ⌈\d\d⌋ then matches the first two digits that follow. The ⌈[1-9]?⌋ matches an additional non-zero digit if that’s what follows the first two. Anything matched so far is what we want to keep, so we wrap it in parentheses to capture to $1. We can then use $1 in the replacement string. If this is the only thing that matches, we replace exactly what was matched with itself — not very useful. However, we go on to match other items outside the $1 parentheses. They don’t find their way to the replacement string, so the effect is that they’re removed. In this case, the “to be removed” text is any extra digits, the ⌈\d*⌋ at the end of the regex.

Keep this example in mind, as we’ll come back to it in Chapter 4 when looking at the important mechanics of just what goes on behind the scenes during a match. Some very interesting lessons can be learned by playing with this example.

Automated Editing

I encountered another simple yet real-world example while working on this chapter. I was logged in to a machine across the Pacific, but the network was particularly slow. Just getting a response from hitting RETURN took more than a minute, but I needed to make a few small changes to a file to get an important program going. In fact, all I wanted to do was change every occurrence of sysread to read. There were only a few such changes to make, but with the slow response, the idea of starting up a full-screen editor was impractical.

Here’s all I did to make all the changes I needed:

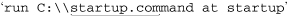

% perl -p -i -e 's/sysread/read/g' file

This runs the Perl program s/sysread/read/g. (Yes, that’s the whole program — the -e flag indicates that the entire program follows right there on the command line.) The -p flag results in the substitution being done for every line of the named file, and the -i flag causes any changes to be written back to the file when done.

Note that there is no explicit target string for the substitute command to work on (that is, no $var =~ ···) because conveniently, the -p flag implicitly applies the program, in turn, to each line of the file. Also, because I used the /g modifier, I’m sure to replace multiple occurrences that might be in a line.

Although I applied this to only one file, I could have easily listed multiple files on the command line and Perl would have applied my substitution to each line of each file. This way, I can do mass editing across a huge set of files, all with one simple command. The particular mechanics with which this was done are unique to Perl, but the moral of the story is that regular expressions as part of a scripting language can be very powerful, even in small doses.

A Small Mail Utility

Let’s work on another example tool. Let’s say we have an email message in a file, and we want to prepare a file for a reply. During the preparation, we want to quote the original message so we can easily insert our own reply to each part. We also want to remove unwanted lines from the header of the original message, as well as prepare the header of our own reply.

The sidebar shows an example. The header has interesting fields — date, subject, and so on—but also much that we are not interested in that we’ll want to remove. If the script we’re about to write is called mkreply, and the original message is in the file king.in, we would make the reply template with:

% perl -w mkreply king.in > king.out

(In case you’ve forgotten, the -w option enables extra Perl warnings  38.)

38.)

We want the resulting file, king.out, to contain something like:

To: elvis@hh.tabloid.org (The King)

From: jfriedl@regex.info (Jeffrey Friedl)

Subject: Re: Be seein' ya around

On Thu, Feb 29 2007 11:15 The King wrote:

|> Sorry I haven't been around lately. A few years back I checked

|> into that ole heartbreak hotel in the sky, ifyaknowwhatImean.

|> The Duke says "hi".

|> Elvis

Let’s analyze this. To print out our new header, we need to know the destination address (in this case elvis@hh.tabloid.org, derived from the Reply-To field of the original), the recipient’s real name (The King), our own address and name, as well as the subject. Additionally, to print out the introductory line for the message body, we need to know the message date.

The work can be split into three phases:

- Extract information from the message header.

- Print out the reply header.

- Print out the original message, indented by ‘

|>•’.

I’m getting a bit ahead of myself — we can’t worry about processing the data until we determine how to read the data into the program. Fortunately, Perl makes this a breeze with the magic “< >” operator. This funny-looking construct gives you the next line of input when you assign from it to a normal $variable, as with "$variable = <>". The input comes from files listed after the Perl script on the command line (from king.in in the previous example).

Don’t confuse the two-character operator < > with the shell’s “> filename” redirection or Perl’s greater-than/less-than operators. It is just Perl’s funny way to express a kind of a getline ( ) function.

Once all the input has been read, < > conveniently returns an undefined value (which is interpreted as a Boolean false), so an entire file can be processed with:

while ($line = < >) {

... work with $line here ...

}

We’ll use something similar for our email processing, but the nature of email means we need to process the header specially. The header includes everything before the first blank line; the body of the message follows. To read only the header, we might use:

# Process the header

while ($line = < >) {

if ($line =~ m/^\s*$/) {

last; # stop processing within this while loop, continue below

}

... process header line here ...

}

... processing for the rest of the message follows ...

*

*

*

We check for the header-ending blank line with the expression ⌈^\s*$⌋. It checks to see whether the target string has a beginning (as all do), followed by any number of whitespace characters (although we aren’t really expecting any except the newline character that ends each line), followed by the end of the string.† The keyword last breaks out of the enclosing while loop, stopping the header-line processing.

So, inside the loop, after the blank-line check, we can do whatever work we like with each header line. In this case, we need to extract information, such as the subject and date of the message.

To pull out the subject, we can employ a popular technique we’ll use often:

if ($line =~ m/^Subject: (.*)/i) {

$subject = $1;

}

This attempts to match a string beginning with ‘Subject:•’, having any capitalization. Once that much of the regex matches, the subsequent ⌈.*⌋ matches whatever else is on the rest of the line. Since the ⌈.*⌋ is within parentheses, we can later use $1 to access the text of the subject. In our case, we just save it to the variable $subject. Of course, if the regex doesn’t match the string (as it won’t with most), the result for the if is false and $subject isn’t set for that line.

Similarly, we can look for the Date and Reply-To fields:

if ($line =~ m/^Date: (.*)/i) {

$date = $1;

}

if ($line =~ m/^Reply-To: (.*)/i) {

$reply_address = $1;

}

The From: line involves a bit more work. First, we want the one that begins with  , not the more cryptic first line that begins with

, not the more cryptic first line that begins with  . We want:

. We want:

From: elvis@tabloid.org (The King)

It has the originating address, as well as the name of the sender in parentheses; our goal is to extract the name.

To match up through the address, we can use ⌈^From:•(\S+)⌋. As you might guess, ⌈\S⌋ matches anything that’s not whitespace ( 49), so ⌈

49), so ⌈\S+⌋ matches up until the first whitespace (or until the end of the target text). In this case, that’s the originating address. Once that’s matched, we want to match whatever is in parentheses. Of course, we also need to match the parentheses themselves. This is done using ⌈\(⌋ and ⌈\)⌋, escaping the parentheses to remove their special metacharacter meaning. Inside the parentheses, we want to match anything — anything except another parenthesis! That’s accomplished with ⌈[^()]*⌋. Remember, the character-class metacharacters are different from the “normal” regex metacharacters; inside a character class, parentheses are not special and do not need to be escaped.

So, putting this all together we get:

⌈^From:•(\S+)•\(([^()]*)\)⌋.

At first it might be a tad confusing with all those parentheses, so Figure 2-4 on the facing page shows it more clearly.

Figure 2-4: Nested parentheses; $1 and $2

When the regex from Figure 2-4 matches, we can access the sender’s name as $2, and also have $1 as a possible return address:

if ($line =~ m/^From: (\S+) \(([^()]*)\)/i) {

$reply_address = $1;

$from_name = $2;

}

Since not all email messages come with a Reply-To header line, we use $1 as a provisional return address. If there turns out to be a Reply-To field later in the header, we’ll overwrite $reply_address at that point. Putting this all together, we end up with:

while ($line = < >)

{

if ($line =~ m/^\s*$/ ) { # If we have an empty line...

last; # this immediately ends the 'while' loop.

}

if ($line =~ m/^Subject: (.*)/i) {

$subject = $1;

}

if ($line =~ m/^Date: (.*)/i) {

$date = $1;

}

if ($line =~ m/^Reply-To: (\S+)/i) {

$reply_address = $1;

}

if ($line =~ m/^From: (\S+) \(([^()]*)\)/i) {

$reply_address = $1;

$from_name = $2;

}

}

Each line of the header is checked against all the regular expressions, and if it matches one, some appropriate variable is set. Many header lines won’t be matched by any of the regular expressions, and so end up being ignored.

Once the while loop is done, we are ready to print out the reply header:†

print "To: $reply_address ($from_name)\n";

print "From: jfriedl\@regex.info (Jeffrey Friedl)\n";

print "Subject: Re: $subject\n";

print "\n" ; # blank line to separate the header from message body.

Notice how we add the Re: to the subject to informally indicate that it is a reply. Finally, after the header, we can introduce the body of the reply with:

print "On $date $from_name wrote:\n";

Now, for the rest of the input (the body of the message), we want to print each line with ‘|>•’ prepended:

while ($line = <>) {

print "|> $line";

}

Here, we don’t need to provide a newline because we know that $line contains one from the input.

It is interesting to see that we can rewrite the code to prepend the quoting marker using a regex construct:

$line =~ s/^/|> /;

print $line;

The substitute searches for ⌈^⌋, which of course immediately matches at the beginning of the string. It doesn’t actually match any characters, though, so the substitute “replaces” the “nothingness” at the beginning of the string with ‘|>•’. In effect, it inserts ‘|>•’ at the beginning of the string. It’s a novel use of a regular expression that is gross overkill in this particular case, but we’ll see similar (but much more useful) examples later in this chapter.

Real-world problems, real-world solutions

It’s hard to present a real-world example without pointing out its real-world shortcomings. First, as I have commented, the goal of these examples is to show regular expressions in action, and the use of Perl is simply a vehicle to do so. The Perl code I’ve used here is not necessarily the most efficient or even the best approach, but, hopefully, it clearly shows the regular expressions at work.

Also, real-world email messages are far more complex than indicated by the simple problem addressed here. A From: line can appear in various different formats, only one of which our program can handle. If it doesn’t match our pattern exactly, the $from_name variable never gets set, and so remains undefined (which is a kind of “no value” value) when we attempt to use it. The ideal fix would be to update the regex to handle all the different address/name formats, but as a first step, after checking the original message (and before printing the reply template), we can put:

if ( not defined($reply_address)

or not defined($from_name)

or not defined($subject)

or not defined($date) )

{

die "couldn't glean the required information!";

}

Perl’s defined function indicates whether the variable has a value, while the die function issues an error message and exits the program.

Another consideration is that our program assumes that the From: line appears before any Reply-To: line. If the From: line comes later, it overwrites the $reply_address we took from the Reply-To: line.

The “real” real world

Email is produced by many different types of programs, each following their own idea of what they think the standard is, so email can be tricky to handle. As I discovered once while attempting to write some code in Pascal, it can be extremely difficult without regular expressions. So much so, in fact, that I found it easier to write a Perl-like regex package in Pascal than attempt to do everything in raw Pascal! I had taken the power and flexibility of regular expressions for granted until I entered a world without them. I certainly didn’t want to stay in that world long.

Adding Commas to a Number with Lookaround

Presenting large numbers with commas often makes reports more readable. Something like

print "The US population is $pop\n";

might print out “The US population is 298444215,” but it would look more natural to most English speakers to use “298,444,215” instead. How might we use a regular expression to help?

Well, when we insert commas mentally, we count sets of digits by threes from the right, and insert commas at each point where there are still digits to the left. It’d be nice if we could apply this natural process directly with a regular expression, but regular expressions generally work left-to-right. However, if we distill the idea of where commas should be inserted as “locations having digits on the right in exact sets of three, and at least some digits on the left,” we can solve this problem easily using a set of relatively new regex features collectively called lookaround.

Lookaround constructs are similar to word-boundary metacharacters like ⌈\b⌋ or the anchors ⌈^⌋ and ⌈$⌋ in that they don’t match text, but rather match positions within the text. But, lookaround is a much more general construct than the special-case word boundary and anchors.

One type of lookaround, called lookahead, peeks forward in the text (toward the right) to see if its subexpression can match, and is successful as a regex component if it can. Positive lookahead is specified with the special sequence ⌈(?=···)⌋, such as with ⌈(?=\d)⌋, which is successful at positions where a digit comes next. Another type of lookaround is lookbehind, which looks back (toward the left). It’s given with the special sequence ⌈(?<=···)⌋, such as ⌈(?<=\d)⌋, which is successful at positions with a digit to the left (i.e., at positions after a digit).

Lookaround doesn’t “consume” text

An important thing to understand about lookahead and other lookaround constructs is that although they go through the motions to see if their subexpression is able to match, they don’t actually “consume” any text. That may be a bit confusing, so let me give an example. The regex ⌈Jeffrey⌋ matches

but the same regex within lookahead, ⌈(?=Jeffrey)⌋, matches only the marked location in:

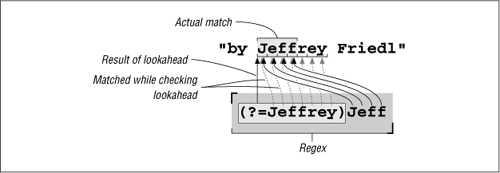

Lookahead uses its subexpression to check the text, but only to find a location in the text at which it can be matched, not the actual text it matches. But, combining it with something that does match text, such as ⌈Jeff⌋, allows us to be more specific than ⌈Jeff⌋ alone. The combined expression, ⌈(?=Jeffrey) Jeff⌋, illustrated in the figure on the facing page, effectively matches “Jeff” only if it is part of “Jeffrey.” It does match:

just like ⌈Jeff⌋ alone would, but it doesn’t match on this line:

... by Thomas Jefferson

By itself, ⌈Jeff⌋ would easily match this line as well, but since there’s no position at which ⌈(?=Jeffrey)⌋ can match, they fail as a pair. Don’t worry too much if the benefit of this doesn’t seem obvious at this point. Concentrate now on the mechanics of what lookahead means — we’ll soon see realistic examples that illustrate their benefit more clearly.

It might be insightful to realize that ⌈(?=Jeffrey)Jeff⌋ is effectively the same as ⌈Jeff(?=rey)⌋. Both match “Jeff” only if it is part of “Jeffrey.”

It’s also interesting to realize that the order in which they’re combined is very important. ⌈Jeff(?=Jeffrey)⌋ doesn’t match any of these examples, but rather matches “Jeff” only if followed immediately by “Jeffrey.”

Figure 2-5: How ⌈(?=Jeffrey)Jeff⌋ is applied

Another important thing to realize about lookaround constructs concerns their somewhat ungainly notation. Like the non-capturing parentheses “(?:···)” introduced on page 45, these constructs use special sequences of characters as their “open parenthesis.” There are a number of such special “open parenthesis” sequences, but they all begin with the two-character sequence “(?”. The character following the question mark tells what special function they perform. We’ve already seen the group-but-don’t-capture “(?:···)”, lookahead “(?=···)”, and lookbehind “(?<=···)” constructs, and we will see more as we go along.

A few more lookahead examples

We’ll get to adding commas to numbers soon, but first let’s see a few more examples of lookaround. We’ll start by making occurrences of “Jeffs” possessive by replacing them with “Jeff’s” This is easy to solve without any kind of lookaround, with s/Jeffs/Jeff's/g. (Remember, the /g is for “global replacement”  51.) Better yet, we can add word-boundary anchors:

51.) Better yet, we can add word-boundary anchors: s/\bJeffs\b/Jeff's/g.

We might even use something fancy like s/\b(Jeff)(s)\b/$1'$2/g, but this seems gratuitously complex for such a simple task, so for the moment we’ll stick with s/\bJeffs\b/Jeff's/g. Now, compare this with:

s/\bJeff(?=s\b)/Jeff'/g

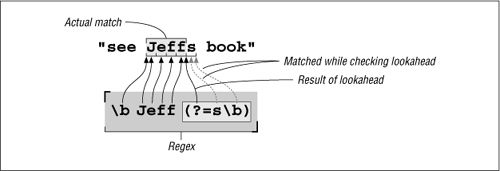

The only change to the regular expression is that the trailing ⌈s\b⌋ is now within lookahead. Figure 2-6 on the next page illustrates how this regex matches. Corresponding to the change in the regex, the ‘s’ has been removed from the replacement string.

After ⌈Jeff⌋ matches, the lookahead is attempted. It is successful only if ⌈s\b⌋ can match at that point (i.e., if ‘s’ and a word boundary is what follows ‘Jeff’). But, because the ⌈s\b⌋ is part of a lookahead subexpression, the ‘s’ it matches isn’t actually considered part of the final match. Remember, while ⌈Jeff⌋ selects text, the lookahead part merely “selects” a position. The only benefit, then, to having the lookahead in this situation is that it can cause the whole regex to fail in some cases where it otherwise wouldn’t. Or, another way to look at it, it allows us to check the entire ⌈Jeffs⌋ while pretending to match only ⌈Jeff⌋.

Figure 2-6: How ⌈\bJeff(?=s\b)⌋ is applied

Why would we want to pretend to match less than we really did? In many cases, it’s because we want to recheck that same text by some later part of the regex, or by some later application of the regex. We see this in action in a few pages when we finally get to the number commafication example. The current example has a different reason: we want to check the whole of ⌈Jeffs⌋ because that’s the situation where we want to add an apostrophe, but if we actually match only ‘Jeff’, that allows the replacement string to be smaller. Since the ‘s’ is no longer part of the match, it no longer needs to be part of what is replaced. That’s why it’s been removed from the replacement string.

So, while both the regular expressions and the replacement string of each example are different, in the end their results are the same. So far, these regex acrobatics may seem a bit academic, but I’m working toward a goal. Let’s take the next step.

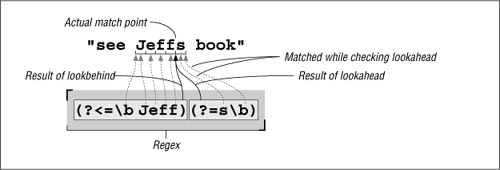

When moving from the first example to the second, the trailing ⌈s⌋ was moved from the “main” regex to lookahead. What if we did something similar with the leading ⌈Jeff⌋, putting it into lookbehind? That would be ⌈(?<=\bJeff) (?=s\b)⌋, which reads as “find a spot where we can look behind to find ‘Jeff’, and also look ahead to find ‘s’.” It exactly describes where we want to insert the apostrophe. So, using this in our substitution gives:

s/(?<=\bJeff)(?=s\b)/'/g

Well, this is getting interesting. The regex doesn’t actually match any text, but rather matches at a position where we wish to insert an apostrophe. At such locations, we then “replace” the nothingness we just matched with an apostrophe. Figure 2-7 illustrates this. We saw this exact type of thing just a few pages ago with the s/^/|>•/ used to prepend ‘|>•’to the line.

Figure 2-7: How ⌈(?<=\bJeff)(?=S\b)⌋ is applied

Would the meaning of the expression change if the order of the two lookaround constructs was switched? That is, what does s/(?=s\b)(?<=\bJeff)/'/g do? ![]() Turn the page to check your answer.

Turn the page to check your answer.

“Jeffs” summary

Table 2-1 summarizes the various approaches we’ve seen to replacing Jeffs with Jeff's.

Table 2-1: Approaches to the “Jeffs” Problem

Solution |

Comments |

|

The simplest, most straightforward, and efficient solution; the one I’d use if I weren’t trying to show other interesting ways to approach the same problem. Without lookaround, the regex “consumes” the entire ‘ |

|

Complex without benefit. Still consumes entire ‘ |

|

Doesn’t actually consume the ‘ |

|

This regex doesn’t actually “consume” any text. It uses both lookahead and lookbehind to match positions of interest, at which an apostrophe is inserted. Very useful to illustrate lookaround. |

|

This is exactly the same as the one above, but the two lookaround tests are reversed. Because the tests don’t consume text, the order in which they’re applied makes no difference to whether there’s a match. |

Before moving back to the adding-commas-to-numbers example, let me ask one question about these expressions. If I wanted to find “Jeffs” in a case-insensitive manner, but preserve the original case after the conversion, which of the expressions could I add /i to and have it work properly? I’ll give you a hint: it won’t work properly with two of them. ![]() Think about which ones would work, and why, and then turn the page to check your answer.

Think about which ones would work, and why, and then turn the page to check your answer.

Back to the comma example...

You’ve probably already realized that the connection between the “Jeffs” example and the comma example lies in our wanting to insert something at a location that we can describe with a regular expression.

Earlier, we realized that we wanted to insert commas at “locations having digits on the right in exact sets of three, and at least some digits on the left.” The second requirement is simple enough with lookbehind. One digit on the left is enough to fulfill the “some digits on the left” requirement, and that’s ⌈(?<=\d)⌋.

Now for “locations having digits on the right in exact sets of three.” An exact set of three digits is ⌈\d\d\d⌋, of course. We can wrap it with ⌈(···)+⌋ to allow more than one (the “sets” of our requirement), and append ⌈$⌋ to ensure that nothing follows (the “exact” of our requirement). Alone, ⌈(\d\d\d)+$⌋ matches sets of triple digits to the end of the string, but when inserted into the ⌈(?=···)⌋ lookahead construct, it matches at locations that are even sets of triple digits from the end of the string, such as at the marked locations in  . That’s actually more than we want —we don’t want to put a comma before the first digit—so we add ⌈

. That’s actually more than we want —we don’t want to put a comma before the first digit—so we add ⌈(?<=\d)⌋ to further limit the match locations.

$pop =~ s/(?<=\d)(?=(\d\d\d)+$)/,/g;

print "The US population is $pop\n";

indeed prints “The US population is 298,444,215” as we desire. It might, however, seem a bit odd that the parentheses surrounding ⌈\d\d\d⌋ are capturing parentheses. Here, we use them only for grouping, to apply the plus to the set of three digits, and so don’t need their capture-to-$1 functionality.

I could have used ⌈(?:···)⌋, the non-capturing parentheses introduced in the sidebar on page 45. This would leave the regex as ⌈(?<=\d)(?=(?:\d\d\d)+$)⌋. This is “better” in that it’s more specific — someone reading this later won’t have to wonder if or where the $1 associated with capturing parentheses might be used. It’s also just a bit more efficient, since the engine doesn’t have to bother remembering the captured text. On the other hand, even with ⌈(···)⌋ the expression can be a bit confusing to read, and with ⌈(?:···)⌋ even more so, so I chose the clearer presentation this time. These are common tradeoffs one faces when writing regular expressions. Personally, I like to use ⌈(?:···)⌋ everywhere it naturally applies (such as this example), but opt for clarity when trying to illustrate other points (as is usually the case in this book).

Word boundaries and negative lookaround

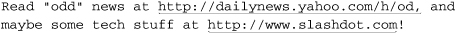

Let’s say that we wanted to extend the use of this expression to commafying numbers that might be included within a larger string. For example:

$text = "The population of 298444215 is growing";

*

*

*

$text =~ s/(?<=\d)(?=(\d\d\d)+$)/,/g;

print "$text\n";

As it stands, this doesn’t work because the ⌈$⌋ requires that the sets of three digits line up with the end of the string. We can’t just remove it, since that would have it insert a comma everywhere that there was a digit on the left, and at least three digits on the right—we’d end up with “.. . of 2,9,8,4,4,4,215 is ...”!

It might seem odd at first, but we could replace ⌈$⌋ with something to match a word boundary, ⌈\b⌋. Even though we’re dealing with numbers only, Perl’s concept of “words” helps us out. As indicated by ⌈\w⌋ ( 49), Perl and most other programs consider alphanumerics and underscore to be part of a word. Thus, any location with those on one side (such as our number) and not those on the other side (e.g., the end of the line, or the space after a number) is a word boundary.

49), Perl and most other programs consider alphanumerics and underscore to be part of a word. Thus, any location with those on one side (such as our number) and not those on the other side (e.g., the end of the line, or the space after a number) is a word boundary.

This “such-and-such on one side, and this-and-that on the other” certainly sounds familiar, doesn’t it? It’s exactly what we did in the “Jeffs” example. One difference here is that one side must not match something. It turns out that what we’ve so far been calling lookahead and lookbehind should really be called positive lookahead and positive lookbehind, since they are successful at positions where their subexpression is able to match. As Table 2-2 shows, their converse, negative lookahead and negative lookbehind, are also available. As their name implies, they are successful as positions where their subexpression is not able to match.

Table 2-2: Four Types of Lookaround

Type |

Regex |

Successful if the enclosed subexpression ... |

Positive Lookbehind |

|

successful if can match to the left |

Negative Lookbehind |

|

successful if can not match to the left |

Positive Lookahead |

|

successful if can match to the right |

Negative Lookahead |

|

successful if can not match to the right |

So, if a word boundary is a position with ⌈\w⌋ on one side and not ⌈\w⌋ on the other, we can use ⌈(?<!\w)(?=\w⌋ as a start-of-word boundary, and its complement ⌈?<=\w)(?!\w)⌋as an end-of-word boundary. Putting them together, we could use ⌈?<!\w)(?=\w)|(?<=\w)(?!\w)⌋ as a replacement for ⌈\b⌋. In practice, it would be silly to do this for languages that natively support \b (\b is much more direct and efficient), but the individual alternatives may indeed be useful ( 134).

134).

For our comma problem, though, we really need only ⌈(?!\d)⌋ to cap our sets of three digits. We use that instead of ⌈\b⌋ or ⌈$⌋, which leaves us with:

This now works on text like “... tone of 12345Hz,” which is good, but unfortunately it also matches the year in “... the 1970s ...” Actually, any of these match “.. . in 1970 ...,” which is not good. There’s no substitute for knowing the data you intend to apply a regex to, and knowing when that application is appropriate (and if your data has year numbers, this regex is probably not appropriate).

Throughout this discussion of boundaries and what we don’t want to match, we used negative lookahead, ⌈(?!\w)⌋ or ⌈(?!\d)⌋. You might remember the “something not a digit” metacharacter ⌈\D⌋ from page 49 and think that perhaps this could be used instead of ⌈(?!\d)⌋. That would be a mistake. Remember, in ⌈\D⌋’s meaning of “something not a digit,” something is required, just something that’s not a digit. If there’s nothing in the text being searched after the digit, ⌈\D⌋ can’t match. (We saw something similar to this back in the sidebar on page 12.)

Commafication without lookbehind

Lookbehind is not as widely supported (nor as widely used) as lookahead. Lookahead support was introduced to the world of regular expressions years before lookbehind, and though Perl now has both, this is not yet true for many languages. Therefore, it might be instructive to consider how to solve the commafication problem without lookbehind. Consider:

The change from the previous example is that the positive lookbehind that had been wrapped around the leading ⌈\d⌋ has been replaced by capturing parentheses, and the corresponding $1 has been inserted into the replacement string, just before the comma.

What about if we don’t have lookahead either? We can put the ⌈\b⌋ back for the ⌈(?!\d)⌋, but does the technique used to eliminate the lookbehind also work for the remaining lookahead? That is, does the following work?

$text =~ s/(\d)((\d\d\d)+\b)/$1,$2/g;

![]() Turn the page to check your answer.

Turn the page to check your answer.

Text-to-HTML Conversion

Let’s write a little tool to convert plain text to HTML. It’s difficult to write a general tool that’s useful for every situation, so for this section we’ll just write a simple tool whose main goal is to be a teaching vehicle.

In all our examples to this point, we’ve applied regular expressions to variables containing exactly one line of text. For this project, it is easier (and more interesting) if we have the entire text we wish to convert available as one big string. In Perl, we can easily do this with:

undef $/; # Enter "file-slurp" mode.

$text = <>; # Slurp up the first file given on the command line.

If our sample file contains the three short lines

This is a sample file.

It has three lines.

That's all

the variable $text will then contain

This is a sample file. It has three lines.

It has three lines. That's all

That's all

although depending on the system, it could instead be

This is a sample file.

It has three lines.

It has three lines.

That's all

That's all

since most systems use a newline to end lines, but some (most notably Windows) use a carriage-return/newline combination. We’ll be sure that our simple tool works with either.

Cooking special characters

Our first step is to make any ‘&’, ‘<’, and ‘>’ characters in the original text “safe” by converting them to their proper HTML encodings, ‘&’, ‘<’, and ‘>’ respectively. Those characters are special to HTML, and not encoding them properly can cause display problems. I call this simple conversion “cooking the text for HTML,” and it’s fairly simple:

$text =~s/&/&/g; # Make the basic HTML...

$text =~s/</</g; # ...characters &,<, and>...

$text =~s/>/>/g; # ...HTML safe.

Here again, we’re using /g so that all of target characters will be converted (as opposed to just the first of each in the string if we didn’t use /g). It’s important to convert & first, since all three have ‘&’ in the replacement.

Separating paragraphs

Next, we’ll mark paragraphs by separating them with the <p> paragraph-separator HTML tag. An easy way to identify paragraphs is to consider them separated by blank lines. There are a number of ways that we might try to identify a blank line. At first you might be tempted to use

$text =~s/^$/<p>/g;

to match a “start-of-line position followed immediately by an end-of-line position.” Indeed, as we saw in the answer on page 10, this would work in a tool like egrep where the text being searched is always considered in chunks containing a single logical line. It would also work in Perl in the context of the earlier email example where we knew that each string contained exactly one logical line.

But, as I mentioned in the footnote on page 55, ⌈^⌋ and ⌈$⌋ normally refer not to logical line positions, but to the absolute start- and end-of-string positions.† So, now that we have multiple logical lines embedded within our target string, we need to do something different.

Luckily, most regex-endowed languages give us an easy solution, an enhanced line anchor match mode in which the meaning of ⌈^⌋ and ⌈$⌋ to change from string related to the logical-line related meaning we need for this example. With Perl, this mode is specified with the /m modifier:

$text =~ s/^$/<p>/mg;

Notice how /m and /g have been combined. (When using multiple modifiers, you can combine them in any order.) We’ll see how other languages handle modifiers in the next chapter.

Thus, if we start with ‘···chapter.’ in

Thus···

Thus···$text, we will end up with ‘···chapter.’ as we want. <p>

<p> Thus···

Thus···

It won’t work, however, if there are spaces or other whitespace on the “blank” line. To allow for spaces, we can use  , or perhaps

, or perhaps  to allow for spaces, tabs, and the carriage return that some systems have before the line-ending newline. These are fundamentally different from ⌈

to allow for spaces, tabs, and the carriage return that some systems have before the line-ending newline. These are fundamentally different from ⌈^$⌋ alone in that these now match actual characters, while ⌈^$⌋ matches only a position. But, since we don’t need those spaces, tabs, and carriage returns in this case, it’s fine to match them (and then replace them with our paragraph tag).

If you remember ⌈\s⌋ from page 47, you might be inclined to use  , just as we did in the email example on page 55. If we use ⌈

, just as we did in the email example on page 55. If we use ⌈\s⌋ instead of ⌈[•\t\r]⌋, the fact that ⌈\s⌋ can match a newline means that the overall meaning changes from “find lines that are blank except for whitespace” to “find spans of lines that are blank except for whitespace.” This means that if we have several blank lines in a row, ⌈^\s*$⌋ is able to match them all in one shot. The fortunate result is that the replacement leaves just one <p> instead of the several in a row we would otherwise end up with.

Therefore, if we have the string

...with. Therefore ...

Therefore ...

in the variable $text, and we use

we’ll end up with:

But, if we use

we’ll end up instead with the more desirable:

So, we’ll stick with ⌈\s*$⌋ in our final program.

“Linkizing” an email address

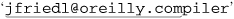

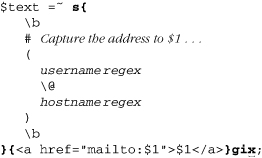

The next step in our text-to-HTML converter is to recognize an email address, and turn it into a “mailto” link. This would convert something like “jfriedl@oreilly.com” to <a•href = "mailto:jfriedl@oreilly.com">jfriedl@oreilly.com</a>.

It’s a common desire to match or validate an email address with a regular expression. The official address specification is quite complex, so to do it exactly is difficult, but we can use something less complex that works for most email addresses we might run into. The basic form of an email address is “username@hostname”. Before looking at just what regular expression to use for each of those parts, let’s look at the context we’ll use them in:

The first things to notice are the two marked backslash characters, one in the regex (‘\@’) and one toward the end of the replacement string. Each is there for a different reason. I’ll defer the discussion of \@ until a bit later ( 77), for the moment merely saying that Perl requires

77), for the moment merely saying that Perl requires @ symbols to be escaped when used in a regex literal.

The backslash before the ‘/’ in the replacement string is a bit more useful to talk about at the moment. We’ve seen that the basic form of a Perl search and replace is s/regex/replacement/modifiers, with the forward slashes delimiting the parts. Now, if we wish to include a forward slash within one of the parts, Perl requires us to escape it to indicate that it should not be taken as a delimiter, but rather included as part of the regex or replacement string. This means that we would need to use  if we wish to get

if we wish to get </a> into the replacement string, which is just what we did here.

This works, but it’s a little ugly, so Perl allows us to pick our own delimiters. For instance, s!regex!string!modifiers or s{regex}{string}modifiers. With either, since the slash in the replacement string no longer conflicts with the delimiter, it no longer needs to be escaped. The delimiters for the regex and string parts pair up nicely in the second example, so I’ll use that form from now on.

Returning to the code snippet, notice how the entire address part is wrapped in ⌈\b···\b⌋. Adding these word boundaries help to avoid an embedded match like in  . Although running into a nonsensical string like that is probably rare, it’s simple enough to use the word boundaries to guard against matching it when we do, so I use them. Notice also that the entire address part is wrapped in parentheses. These are to capture the matched address, making it available to the replacement string ‘

. Although running into a nonsensical string like that is probably rare, it’s simple enough to use the word boundaries to guard against matching it when we do, so I use them. Notice also that the entire address part is wrapped in parentheses. These are to capture the matched address, making it available to the replacement string ‘<a•href="mailto:$1">$1</a>’.

Matching the username and hostname

Now we turn our attention to actually matching an email address by building those username and hostname regular expressions. Hostnames, like regex.info and www.oreilly.com, consist of dot-separated parts ending with ‘com’, ‘edu’, ‘info’, ‘uk’, or other selected sequences. A simplistic approach to matching an email address could be ⌈\w+\@\w+(\.\w+)+⌋, which allows ⌈\w+⌋ for the username and the same for each part of the hostname. In practice, though, you’ll need something a little more specific. For usernames, you’ll run into some with periods and dashes in them (although rarely does a username start with one of these). So, rather than ⌈\w+⌋, we’ll try ⌈\w[-.\w]*⌋. This requires the name to start with a ⌈\w⌋, character, but then allows periods and dashes as well. (Notice how we are sure to put the dash first in the class, to ensure that it’s taken as a literal dash, and not the part of an a-z type of range? With many flavors, a range like .-\w is almost certainly wrong, yielding a fairly random set of letters, numbers, and punctuation that’s dependent on the program and the computer’s native character encoding. Perl handles .-\w in a class just fine, but being careful with dash in a class is a good habit to get into.)

The hostname part is a bit more complex in that the dots are strictly separators, which means that there must be something in between for them to separate. This is why even in the simplistic version earlier, the hostname part uses ⌈\w+(\.\w+)+⌋ instead of ⌈[\w.]+⌋. The latter incorrectly matches ‘..x..’. But, even the former matches in ‘Artichokes ’, so we still need to be more specific.

One approach is to specifically list what the last component can be, along the lines of ⌈\w+(\.\w+)*\.(com|edu|info)⌋. (That list of alternatives really should be com|edu|gov|int|mil|net|org|biz|info|name|museum|coop|aero|[a-z][a-z], but I’ll use the shorter list to keep the example uncluttered.) This allows a leading ⌈\w+⌋ part, along with optional additional ⌈\.\w+⌋ parts, finally followed by one of the specific ending parts we’ve listed.

Actually, ⌈\w⌋ is not quite appropriate. It allows ASCII letters and digits, which is good, but with some systems may allow non-ASCII letters such as à, ç, Ξ, Æ, and with most flavors, an underscore as well. None of these extra characters are allowed in a hostname. So, we probably should use ⌈[a-zA-Z0-9]⌋, or perhaps ⌈[a-z0-9]⌋ with the /i modifier (for a case-insensitive match). Hostnames can also have a dash as well, so we’ll use ⌈[-a-z0-9]⌋ (again, being careful to put the dash first). This leaves us with ⌈[-a-z0-9]+(\.[-a-z0-9]+)*\.(com|edu|info)⌋ for the hostname part.

As with all regex examples, it’s important to remember the context in which they will be used. By itseff, ⌈[-a-z0-9]+(\.[-a-z0-9]+)*\.(com|edu|info)⌋ could match, say  , but once we drop it into the context of our program, we’ll be sure that it matches where we want, and not where we don’t. In fact, I’d like to drop it right into the

, but once we drop it into the context of our program, we’ll be sure that it matches where we want, and not where we don’t. In fact, I’d like to drop it right into the

$text =~ s{\b(usernameregex\@hostnameregex)\b}{<a href="mailto:$1">$1</a>}gi;

form mentioned earlier (updated here with the s{···}{···} delimiters, and the /i modifier), but there’s no way I could get it to fit onto the page. Perl, of course, doesn’t care if it fits nicely or looks pretty, but I do. That’s why I’ll now introduce the /x modifier, which allows us to rewrite that regex as:

Wow, that’s different! The /x modifier appears at the end of that snippet (along with the /g and /i modifiers), and does two simple but powerful things for the regular expression. First, it causes most whitespace to be ignored, so you can “free-format” the expression for readability. Secondly, it allows comments with a leading #.

Specifically, /x turns most whitespace into an “ignore me” metacharacter, and # into an “ignore me, and everything else up to the next newline” metacharacter ( 111). They aren’t taken as metacharacters within a character class (which means that classes are not free-format, even with