8

Java

Java has had a native regex package, java.util.regex, since the early-2002 release of Java 1.4.0. It provides powerful and innovative functionality with an uncluttered (if somewhat simplistic) API. It has fairly good Unicode support, clear documentation, and fast execution. It matches against CharSequence objects, so it can be quite flexible in its application.

The original release of java.util.regex was impressive. Its feature set, speed, and relative lack of bugs were all of the highest caliber, especially considering that it was an initial release. The final 1.4 release was Java 1.4.2. As of this writing, Java 1.5.0 (also called Java 5.0) has been released, and Java 1.6.0 (also called Java 6.0 and “Mustang”) is in its second beta release. Officially, this book covers Java 1.5.0, but I’ll note important differences from Java 1.4.2 and the second 1.6 beta where appropriate. (The differences are also summarized at the end of this chapter  401.)†

401.)†

Reliance on Earlier Chapters Before looking at what’s in this chapter, it’s important to mention that it doesn’t restate everything from Chapters 1 through 6. I understand that some readers interested only in Java may be inclined to start their reading with this chapter, and I want to encourage them not to miss the benefits of the preface and the earlier chapters: Chapters 1, 2, and 3 introduce basic concepts, features, and techniques involved with regular expressions, while Chapters 4, 5, and 6 offer important keys to regex understanding that apply directly to java.util.regex. Among the important concepts covered in earlier chapters are the base mechanics of how an NFA regex engine goes about attempting a match, greediness, backtracking, and efficiency concerns.

Sorted alphabetically, with page numbers |

||

380 |

373 |

379 |

381 |

376 |

390 |

372 |

395 |

392 |

377 |

393 |

395 |

375 |

394 |

377 |

394 |

395 |

394 |

377 |

379 |

377 |

377 |

386 |

393 |

388 |

386 |

394 |

387 |

386 |

388 |

390 |

378 |

393 |

376 |

382 |

387 |

This table has been placed here for easy reference. The regex API discussion starts on page 371. |

||

Along those lines, let me emphasize that despite convenient tables such as the one in this chapter on page 367, or, for example, ones in Chapter 3 such as those on pages 114 and 123, this book’s foremost intention is not to be a reference, but a detailed instruction on how to master regular expressions.

We’ve seen examples of java.util.regex in earlier chapters ( 81, 95, 98, 217, 235), and we’ll see more in this chapter when we look at its classes and how to actually put it to use. First, though, we’ll take a look at the regex flavor it supports, as well as the modifiers that influence that flavor.

81, 95, 98, 217, 235), and we’ll see more in this chapter when we look at its classes and how to actually put it to use. First, though, we’ll take a look at the regex flavor it supports, as well as the modifiers that influence that flavor.

Java’s Regex Flavor

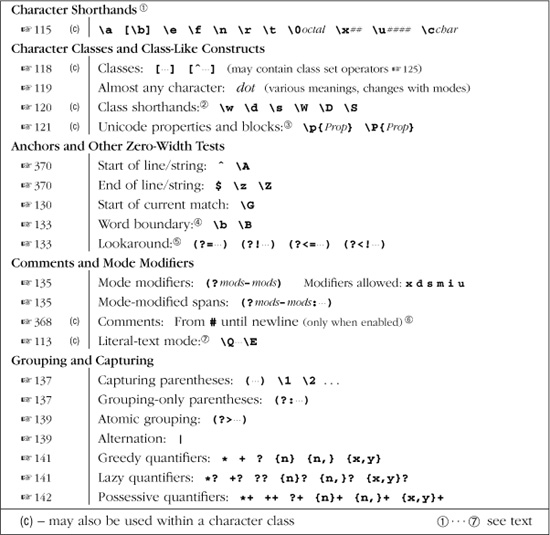

java.util.regex is powered by a Traditional NFA, so the rich set of lessons from Chapters 4, 5, and 6 apply. Table 8-2 on the facing page summarizes its metacharacters. Certain aspects of the flavor are modified by a variety of match modes, turned on via flags to the various methods and factories, or turned on and off via ⌈(?mods-mods)⌋ and ⌈(?mods-mods: ...)⌋ modifiers embedded within the regular expression itself. The modes are listed in Table 8-3 on page 368.

These notes augment Table 8-2:

\b is a character shorthand for backspace only within a character class. Outside of a character class, \b matches a word boundary ( 133).

133).

The table shows “raw” backslashes, not the doubled backslashes required when regular expressions are provided as Java string literals. For example, ⌈\n⌋ in the table must be written as "\\n" as a Java string. See “Strings as Regular Expressions” ( 101).

101).

\x## allows exactly two hexadecimal digits, e.g., ⌈\xFCber⌋ matches ‘über’.

Table 8-2: Overview of Sun’s java.util.regex Flavor

\u#### allows exactly four hexadecimal digits, e.g., ⌈\u00FCber⌋ matches ‘über’, and ⌈\u20AC⌋ matches ‘€’.

\0octal requires a leading zero, followed by one to three octal digits.

\cchar is case sensitive, blindly xoring the ordinal value of the following character with 0x40. This bizarre behavior means that, unlike any other flavor I’ve ever seen, \cA and \ca are different. Use uppercase letters to get the traditional meaning of \x01. As it happens, \ca is the same as \x21, matching ‘!’.

\w, \d, and \s (and their uppercase counterparts) match only ASCII characters, and don’t include the other alphanumerics, digits, or whitespace in Unicode. That is, \d is exactly the same as [0-9], \w is the same as [0-9a-zA-z_], and \s is the same as [•\t\n\f\r\x0B] (\x0B is the little-used ASCII VT character). For full Unicode coverage, you can use Unicode properties ( 121): use

121): use \p{L} for \w, use \p{Nd} for \d, and use \p{Z} for \s. (Use the \P{···} version of each for \W, \D, and \S.)

\p{···} and \P{···} support Unicode properties and blocks, and some additional “Java properties.” Unicode scripts are not supported. Details follow on the facing page.

The

The \b and \B word boundary metacharacters’ idea of a “word character” is not the same as that of \w and \W. The word boundaries understand the properties of Unicode characters, while \w and \W match only ASCII characters.

Lookahead constructs can employ arbitrary regular expressions, but lookbehind is restricted to subexpressions whose possible matches are finite in length. This means, for example, that ⌈?⌋ is allowed within lookbehind, but ⌈*⌋ and ⌈+⌋ are not. See the description in Chapter 3, starting on page 133.

Lookahead constructs can employ arbitrary regular expressions, but lookbehind is restricted to subexpressions whose possible matches are finite in length. This means, for example, that ⌈?⌋ is allowed within lookbehind, but ⌈*⌋ and ⌈+⌋ are not. See the description in Chapter 3, starting on page 133.

#... sequences are taken as comments only under the influence of the x modifier, or when the

sequences are taken as comments only under the influence of the x modifier, or when the Pattern.COMMENTS option is used ( 368). (Don’t forget to add newlines to multiline string literals, as in the example on page 401.) Unescaped ASCII whitespace is ignored. Note: unlike most regex engines that support this type of mode, comments and free whitespace are recognized within character classes.

368). (Don’t forget to add newlines to multiline string literals, as in the example on page 401.) Unescaped ASCII whitespace is ignored. Note: unlike most regex engines that support this type of mode, comments and free whitespace are recognized within character classes.

\Q...\E has always been supported, but its use entirely within a character class was buggy and unreliable until Java 1.6.

Table 8-3: The java.util.regex Match and Regex Modes

Compile-Time Option |

( |

Description |

|

|

Changes how dot and ⌈^⌋ match ( |

|

|

Causes dot to match any character ( |

|

|

Expands where ⌈^⌋ and ⌈$⌋ can match ( |

|

|

Free-spacing and comment mode ( |

|

|

Case-insensitive matching for ASCII characters |

|

|

Case-insensitive matching for non-ASCII characters |

|

|

Unicode “canonical equivalence” match mode (different encodings of the same character match as identical |

|

|

Treat the regex argument as plain, literal text instead of as a regular expression |

Java Support for \p{···} and \P{···}

The ⌈\p{···}⌋ and ⌈\P{···}⌋ constructs support Unicode properties and blocks, as well as special “Java” character properties. Unicode support is as of Unicode Version 4.0.0. (Java 1.4.2’s support is only as of Unicode Version 3.0.0.)

Unicode properties

Unicode properties are referenced via short names such as \p{Lu}. (See the list on page 122.) One-letter property names may omit the braces: \pL is the same as \p{L}. The long names such as \p{Lowercase_Letter} are not supported.

In Java 1.5 and earlier, the Pi and Pf properties are not supported, and as such, characters with that property are not matched by \p{P}. (Java 1.6 supports them.)

The “other stuff” property \p{C} doesn’t match code points matched by the “unassigned code points” property \p{Cn}.

The \p{L&} composite property is not supported.

The pseudo-property \p{all} is supported and is equivalent to ⌈(?s:.)⌋. The \p{assigned} and \p{unassigned} pseudo-properties are not supported, but you can use \P{Cn} and \p{Cn} instead.

Unicode blocks

Unicode blocks are supported, requiring an ‘In’ prefix. See page 402 for version-specific details on how block names can appear within ⌈\p{···}⌋ and ⌈\P{···}⌋.

For backward compatibility, two Unicode blocks whose names changed between Unicode Versions 3.0 and 4.0 are accessible by either name as of Java 1.5. The extra non-Unicode-4.0 names Combining Marks for Symbols and Greek can now be used in addition to the Unicode 4.0 standard names Combining Diacritical Marks for Symbols and Greek and Coptic.

A Java 1.4.2 bug involving the Arabic Presentation Forms-B and Latin Extended-B block names has been fixed as of Java 1.5 ( 403).

403).

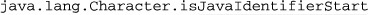

Special Java character properties

Starting in Java 1.5.0, the \p{···} and \P{···} constructs include support for the non-deprecated isSomething methods in java.lang.Character. To access the method functionality within a regex, replace the method name’s leading ‘is’ with ‘java’, and use that within ⌈\p{···}⌋ or ⌈\P{···}⌋. For example, characters matched by  can be matched from with in a regex by

can be matched from with in a regex by  . (See the

. (See the java.lang.Character class documentation for a complete list of applicable methods.)

Unicode Line Terminators

In traditional pre-Unicode regex flavors, a newline (ASCII LF character) is treated specially by dot, ^, $, and \Z. In Java, most Unicode line terminators ( 109) also receive this special treatment.

109) also receive this special treatment.

Java normally considers the following as line terminators:

Character Codes |

Nicknames |

Description |

|

U |

LF |

|

ASCII Line Feed (“newline”) |

U |

CR |

|

ASCII Carriage Return |

U |

CR/LF |

|

ASCII Carriage Return / Line Feed sequence |

U |

NEL |

|

Unicode NEXT LINE |

U |

LS |

|

Unicode LINE SEPARATOR |

U |

PS |

|

Unicode PARAGRAPH SEPARATOR |

The characters and situations that are treated specially by dot, ^, $, and \Z change depending on which match modes ( 368) are in effect:

368) are in effect:

Match Mode |

Affects |

Description |

|

|

Revert to traditional newline-only line-terminator semantics. |

|

|

Add embedded line terminators to list of locations after which |

|

|

Line terminators no longer special to dot; it matches any character. |

The two-character CR/LF line-terminator sequence deserves special mention. By default, when the full complement of line terminators is recognized (that is, when UNIX_LINES is not used), a CR/LF sequence is treated as an atomic unit by the line-boundary metacharacters, and they can’t match between the sequence’s two characters.

For example, $ and \Z can normally match just before a line terminator. LF is a line terminator, but $ and \Z can match before a string-ending LF only when it is not part of a CR/LF sequence (that is, when the LF is not preceded by a CR).

This extends to $ and ^ in MULTILINE mode, where ^ can match after an embedded CR only when that CR is not followed by a LF, and $ can match before an embedded LF only when that LF is not preceded by a CR.

To be clear, DOTALL has no effect on how CR/LF sequences are treated (DOTALL affects only dot, which always considers characters individually), and UNIX_LINES removes the issue altogether (it renders LF and all the other non-newline line terminators unspecial).

Using java.util.regex

The mechanics of wielding regular expressions with java.util.regex are fairly simple, with the functionality provided by only two classes, an interface, and an unchecked exception:

java.util.regex.Pattern

java.util.regex.Matcher

java.util.regex.MatchResult

java.util.regex.PatternSyntaxException

Informally, I’ll refer to the first two simply as “pattern” and “matcher,” and in many cases, these are the only classes we’ll use. A Pattern object is, in short, a compiled regular expression that can be applied to any number of strings, and a Matcher object is an individual instance of that regex being applied to a specific target string.

New in Java 1.5, MatchResult encapsulates the data from a successful match. Match data is available from the matcher itself until the next match attempt, but can be saved by extracting it as a MatchResult.

PatternSyntaxException is thrown when an attempt is made to use an ill-formed regular expression (one such as ⌈[oops)⌋ that’s not syntactically correct). It extends java.lang.IllegalAgumentException and is unchecked.

Here’s a complete, verbose example showing a simple match:

public class SimpleRegexTest {

public static void main(String[] args)

{

String myText = "this is my 1st test string";

String myRegex = "\\d+\\w+"; // This provides for ⌈\d+\w+⌋

java.util.regex.Pattern p = java.util.regex.Pattern.compile(myRegex);

java.util.regex.Matcher m = p.matcher(myText);

if (m.find()) {

String matchedText = m.group();

int matchedFrom = m.start();

int matchedTo = m.end();

System.out.println("matched [" + matchedText + "] " +

"from " + matchedFrom +

" to " + matchedTo + ".");

} else {

System.out.println("didn't match");

}

}

}

This prints 'matched [1st] from 12 to 15.'. As with all examples in this chapter, names I’ve chosen are italicized. The parts shown in bold can be omitted if

import java.util.regex.*;

is inserted at the head of the program, as with the examples in Chapter 3 ( 95). Doing so is the standard approach, and makes the code more manageable. The rest of this chapter assumes the

95). Doing so is the standard approach, and makes the code more manageable. The rest of this chapter assumes the import statement is always supplied.

The object model used by java.util.regex is a bit different from most. In the previous example, notice that the Matcher object m, after being created by associating a Pattern object and a target string, is used to launch the actual match attempt (with its find method), and to query the results (with its group, start, and end methods).

This approach may seem a bit odd at first glance, but you’ll quickly get used to it.

The Pattern.compile() Factory

A regular-expression Pattern object is created with Pattern.compile. The first argument is a string to be interpreted as a regular expression ( 101). The compile-time options shown in Table 8-3 on page 368 can be provided as a second argument. Here’s a snippet that creates a pattern from the string in the variable

101). The compile-time options shown in Table 8-3 on page 368 can be provided as a second argument. Here’s a snippet that creates a pattern from the string in the variable myRegex, to be applied in a case-insensitive manner:

Pattern pat = Pattern.compile(myRegex,

Pattern.CASERINSENSITIVE | Pattern.UNICODERCASE);

The predefined pattern constants used to specify the compile options (such as Pattern.CASE_INSENSITIVE) can be a bit unwieldy,† so I tend to use inline mode modifiers ( 110) when practical. Examples include

110) when practical. Examples include ⌈(?x)⌋ on page 378, and ⌈(?s)⌋ and several ⌈(?i)⌋ on page 399.

However, keep in mind that the same verbosity that makes these predefined constants “unwieldy” can make them easier to understand to the novice. Were I to have unlimited page width, I might use

Pattern.UNIX_LINES | Pattern.CASE_INSENSITIVE

as the second argument to the Pattern.compile on page 384, rather than prepend the possibly unclear ⌈(?id)⌋ at the start of the regex.

As the method name implies, this is the step in which a regular expression is analyzed and compiled into an internal form. Chapter 6 looks at this in great detail ( 241), but in short, the pattern compilation can often be the most time-consuming step in the whole check-a-string-with-a-regex process. That’s why there are separate compile and apply steps in the first place—it allows you to precompile a regex for later use over and over.

241), but in short, the pattern compilation can often be the most time-consuming step in the whole check-a-string-with-a-regex process. That’s why there are separate compile and apply steps in the first place—it allows you to precompile a regex for later use over and over.

Of course, if a regex is going to be compiled and used only once, it doesn’t matter when it’s compiled, but when applying a regex many times (for example, to each line read from a file), it makes a lot of sense to precompile into a Pattern object.

A call to Pattern.compile can throw two kinds of exceptions: an invalid regular expression throws PatternSyntaxException, and an invalid option value throws IllegalArgumentException.

Pattern’s matcher method

Patterns offer some convenience methods that we’ll look at in a later section ( 394), but for the most part, all the work is done through just one method:

394), but for the most part, all the work is done through just one method: matcher. It accepts a single argument: the string to search.† It doesn’t actually apply the regex, but prepares the pattern to be applied to a specific string. The matcher method returns a Matcher object.

The Matcher Object

Once you’ve associated a regular expression with a target string by creating a matcher, you can instruct it to apply the regex to the target in various ways, and query the results of that application. For example, given a matcher m, the call m.find() actually applies m’s regex to its string, returning a Boolean indicating whether a match is found. If a match is found, the call m.group() returns a string representing the text actually matched.

Before looking in detail at a matcher’s various methods, it’s useful to have an overview of what information it maintains. To serve as a better reference, the following lists are sprinkled with page references to details about each item. Items in the first list are those that the programmer can set or modify, while items in the second list are read-only.

Items that the programmer can set or update:

• The Pattern object provided by the programmer when the matcher is created. It can be changed by the programmer with the usePattern() method ( 393). The current pattern can be retrieved with the

393). The current pattern can be retrieved with the pattern() method.

• The target-text string (or other CharSequence) provided by the programmer when the matcher is created. It can be changed by the programmer with the reset (text) method ( 392).

392).

• The region of the target text ( 384). The region defaults to the whole of the target text, but can be changed by the programmer to delimit some smaller subset of the target text via the

384). The region defaults to the whole of the target text, but can be changed by the programmer to delimit some smaller subset of the target text via the region method. This constrains some (but not all) of the match methods to looking for a match only within the region.

The current region start and end character offsets are available via the regionStart and regionEnd methods ( 386). The

386). The reset method ( 392) resets the region to the full-text default, as do any of the methods that call

392) resets the region to the full-text default, as do any of the methods that call reset internally ( 392).

392).

• An anchoring bounds flag. If the region is set to something other than the full text, you can control whether the moved edges of the region are considered “start of text” and “end of text” with respect to the line-boundary metacharacters (\A ^ $ \z \Z).

This flag defaults to true, but the value can be changed and inspected with the useAnchoringBounds ( 388) and

388) and hasAnchoringBounds methods, respectively. The reset method does not change this flag.

• A transparent bounds flag. When the region is a subset of the full target text, turning on “transparent bounds” allows the characters beyond the edge of the range to be inspected by “looking” constructs (lookahead, lookbehind, and word boundaries), despite being outside the current range.

This flag defaults to false, but the value can be changed and inspected with the useTransparentBounds ( 387) and

387) and hasTransparentBounds methods, respectively. The reset method does not change this flag.

The following are the read-only data maintained by the matcher:

• The number of sets of capturing parentheses in the current pattern. This value is reported via the groupCount method ( 377).

377).

• A match pointer or current location in the target text, used to support a “find next match” operation (via the find method  375).

375).

• An append pointer location in the target text, used to support the copying of unmatched regions of text during a search-and-replace operation ( 380).

380).

• A flag indicating whether the previous match attempt hit the end of the target string on its way to its eventual success or failure. The value of the flag is reported by the hitEnd method ( 390).

390).

• The match result. If the most recent match attempt was successful, various data about the match is collectively called the match result ( 376). It includes the span of text matched (via the

376). It includes the span of text matched (via the group () method), the indices within the target text of that span’s start and end (via the start() and end() methods), and information regarding what was matched by each set of capturing parentheses (via the group(num), start(num), and end(num) methods).

The encapsulated match-result data is available via its own MatchResult object, returned via the toMatchResult method. A MatchResult object has its own group, start, and end methods comparable to those of a matcher ( 377).

377).

• A flag indicating whether longer target text could have rendered the match unsuccessful (also available only after a successful match). The flag is true for any match where a boundary metacharacter plays a part in the conclusion of the match. The value of the flag is available via the requireEnd method ( 390).

390).

These lists are a lot to absorb, but they are easier to grasp when discussing the methods grouped by functionality. The next few sections do so. Also, the list of methods at the start of the chapter ( 366) will help you to find your way around when using this chapter as a reference.

366) will help you to find your way around when using this chapter as a reference.

Applying the Regex

Here are the main Matcher methods for actually applying the matcher’s regex to its target text:

boolean find()

This method applies the matcher’s regex to the current region ( 384) of the matcher’s target text, returning a Boolean indicating whether a match is found. If called multiple times, the next match is returned each time. This no-argument form of

384) of the matcher’s target text, returning a Boolean indicating whether a match is found. If called multiple times, the next match is returned each time. This no-argument form of find respects the current region ( 384).

384).

Here’s a simple example:

String regex = "\\w+"; // !\w+"

String text = "Mastering Regular Expressions";

Matcher m = Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(text);

if (m.find())

System.out.println("match [" + m.group() + "]");

It produces:

match [Mastering]

If, however, the if control construct is changed to while, as in

while (m.find())

System.out.println("match [" + m.group() + "]");

it then walks through the string reporting all matches:

match [Mastering]

match [Regular]

match [Expressions]

boolean find (int offset)

If find is given an integer argument, the match attempt starts at that offset number of characters from the beginning of the matcher’s target text. It throws IndexOutOfBoundsException if the offset is negative or larger than the length of the target text.

This form of the find method does not respect the current region, going so far as to first reset the region to its “whole text” default (when it internally invokes the reset method  392).

392).

An excellent example of this form of find in action can be found in the sidebar on page 400 (which itself is the answer to a question posed on page 399).

boolean matches()

This method returns a Boolean indicating whether the matcher’s regex exactly matches the current region of the target text ( 384). That is, a match must start at the beginning of the region and finish at the end of the region (which defaults to cover the entire target). When the region is set at its “all text” default,

384). That is, a match must start at the beginning of the region and finish at the end of the region (which defaults to cover the entire target). When the region is set at its “all text” default, matches provides little advantage over simply using ⌈\A(?:···)\z⌋ around the regex, other than perhaps a measure of simplicity or convenience.

However, when the region is set to something other than the default ( 384),

384), matches allows you to check for a full-region match without having to rely on the state of the anchoring-bounds flag ( 388).

388).

For example, imagine using a CharBuffer to hold text being edited by the user within your application, with the region set to whatever the user has selected with the mouse. If the user then clicks on the selection, you might use m.usePattern(urlPattern).matches() to see whether the selected text is a URL (and if so, then perform some URL-related action appropriate to the application).

String objects also support a matches method:

"1234".matches(“\\d+”); // true

"123!".matches(“\\d+”); // false

boolean lookingAt()

This method returns a Boolean indicating whether the matcher’s regex matches within the current region of the target text, starting from the beginning of the region. This is similar to the matches method except that the entire region doesn’t need to be matched, just the beginning.

Querying Match Results

The matcher methods in the following list return information about a successful match. They throw IllegalStateException if the matcher’s regex hasn’t yet been applied to its target text, or if the previous application was not successful. The methods that accept a num argument (referring to a set of capturing parentheses) throw IndexOutOfBoundsException when an invalid num is given.

Note that the start and end methods, which return character offsets, do so without regard to the region — their return values are offsets from the start of the text, not necessarily from the start of the region.

Following this list of methods is an example illustrating many of them in action.

String group()

Returns the text matched by the previous regex application.

int groupCount()

Returns the number of sets of capturing parentheses in the regex associated with the matcher. Numbers up to this value can be used as the num argument to the group, start, and end methods, described next.†

String group(int num)

Returns the text matched by the numth set of capturing parentheses, or null if that set didn’t participate in the match. A num of zero indicates the entire match, so group(0) is the same as group().

int start(int num)

This method returns the absolute offset, in characters, from the start of the string to the start of where the numth set of capturing parentheses matched. Returns -1 if the set didn’t participate in the match.

int start()

This method returns the absolute offset to the start of the overall match. start() is the same as start(0).

int end(int num)

This method returns the absolute offset, in characters, from the start of the string to the end of where the numth set of capturing parentheses matched. Returns -1 if the set didn’t participate in the match.

int end()

This method returns the absolute offset to the end of the overall match. end() is the same as end(0).

MatchResult toMatchResult()

Added in Java 1.5.0, this method returns a MatchResult object encapsulating data about the most recent match. It has the same group, start, end, and groupCount methods, listed above, as the Matcher class.

A call to toMatchResult throws IllegalStateException if the matcher hasn’t attempted a match yet, or if the previous match attempt was not successful.

Match-result example

Here’s an example that demonstrates many of these match-result methods. Given a URL in a string, the code identifies and reports on the URL’s protocol (’http' or ‘https’), hostname, and optional port number:

String url = "http://regex.info/blog";

String regex = "(?x) ^(https?):// ([^/:]+) (?:(\\d+))?";

Matcher m = Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(url);

if (m.find())

{

System.out.print(

"Overall [" + m.group() + "]" +

" (from " + m.start() + " to " + m.end() + ")\n" +

"Protocol [" + m.group(1) + "]" +

" (from " + m.start(1) + " to " + m.end(1) + ")\n" +

"Hostname [" + m.group(2) + "]" +

" (from " + m.start(2) + " to " + m.end(2) + ")\n"

);

// Group #3 might not have participated, so we must be careful here

if (m.group(3) == null)

System.out.println("No port; default of '80' is assumed");

else {

System.out.print("Port is [" + m.group(3) + "] " +

"(from " + m.start(3) + " to " + m.end(3) + ")\n");

}

}

When executed, it produces:

Overall [http://regex.info] (from 0 to 17)

Protocol [http] (from 0 to 4)

Hostname [regex.info] (from 7 to 17)

No port; default of '80' is assumed

Simple Search and Replace

You can implement search-and-replace operations using just the methods mentioned so far, if you don’t mind doing a lot of housekeeping work yourself, but a matcher offers convenient methods to do simple search and replace for you:

String replaceAll (String replacement)

Returns a copy of the matcher’s string with spans of text matched by its regex replaced by replacement, as per the special processing discussed on page 380.

This method does not respect the region (it invokes reset internally), although page 382 describes a homemade version that does.

This functionality is available via the String class replaceAll method, so

string.replaceAll(regex, replacement)

is equivalent to:

Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(string).replaceAll(replacement)

String replaceFirst(String replacement)

This method is similar to replaceAll, but only the first match (if any) is replaced.

This functionality is available via the String class replaceFirst method.

static String quoteReplacement(String text)

This static method, available since Java 1.5, returns a string for use as a replacement argument such that the literal value of text is used as the replacement. It does this by adding escapes to a copy of text that defeat the special processing discussed in the section on the next page. (That section also includes an example of Matcher.quoteReplacement, as well.)

Simple search and replace examples

This simple example replaces every occurrence of “Java 1.5” with “Java 5.0,” to convert the nomenclature from engineering to marketing:

String text = “Before Java 1.5 was Java 1.4.2. After Java 1.5 is Java 1.6";

String regex = “\\bJava\\s*1\\.5\\b";

Matcher m = Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(text);

String result = m.replaceAll(“Java 5.0”);

System.out.println(result);

It produces:

Before Java 5.0 was Java 1.4.2. After Java 5.0 is Java 1.6

If you won’t need the pattern and matcher further, you can chain everything together, setting result to:

Pattern.compile("\\bJava\\s*1\\.5\\b").matcher(text).replaceAll("Java 5.0")

(If the regex is used many times within the same thread, it’s most efficient to precompile the Pattern object  372.)

372.)

You can convert “Java 1.6” to “Java 6.0” as well, by making a small adjustment to the regex (and a corresponding adjustment to the replacement string, as per the discussion on the next page).

Pattern.compile("\\bJava\\s*1\\.([56])\\b").matcher(text).replaceAll("Java $1.0")

which, when given the same text as earlier, produces:

Before Java 5.0 was Java 1.4.2. After Java 5.0 is Java 6.0

You can use replaceFirst instead of replaceAll with any of these examples to replace only the first match. You should use replaceFirst when you want to forcibly limit the matcher to only one replacement, of course, but it also makes sense from an efficiency standpoint to use it when you know that only one match is possible. (You might know this because of your knowledge of the regex or the data, for example.)

The replacement argument

The replacement argument to the replaceAll and replaceFirst methods (and to the next section’s appendReplacement method, for that matter) receives special treatment prior to being inserted in place of a match, on a per-match basis:

• Instances of '$1', '$2', etc., within the replacement string are replaced by the text matched by the associated set of capturing parentheses. ($0 is replaced by the entire text matched.)

IllegalArgumentException is thrown if the character following the ‘$’ is not an ASCII digit.

Only as many digits after the ‘$’ as “make sense” are used. For example, if there are three capturing parentheses, '$25' in the replacement string is interpreted as $2 followed by the character '5'. However, in the same situation, '$6' in the replacement string throws IndexOutOfBoundsException.

• A backslash escapes the character that follows, so use ‘\$’ in the replacement string to include a dollar sign in it. By the same token, use ‘\\’ to get a backslash into the replacement value. (And if you’re providing the replacement string as a Java string literal, that means you need “ \ \ \ \” to get a backslash into the replacement value.) Also, if there are, say, 12 sets of capturing parentheses and you’d like to include the text matched by the first set, followed by '2', you can use a replacement value of '$1\2'.

If you have a string of unknown content that you intend to use as the replacement text, it’s best to use Matcher.quoteReplacement to ensure that any replacement metacharacters it might contain are rendered inert. Given a user’s regex in uRegex and replacement text in uRepl, this snippet ensures that the replaced text is exactly that given:

Pattern.compile(uRegex).matcher(text).replaceAll(Matcher.quoteReplacement(uRepl))

Advanced Search and Replace

Two methods provide raw access to a matcher’s search-and-replace mechanics. Together, they build a result in a StringBuffer that you provide. The first, called after each match, fills the result with the replacement string and the text between the matches. The second, called after all matches have been found, tacks on whatever text remains after the final match.

Matcher appendReplacement(StringBuffer result, String replacement)

Called immediately after a regex has been successfully applied (usually with find), this method appends two strings to the given result: first, it copies in the text of the original target string prior to the match. Then, it appends the replacement string, as per the special processing described in the previous section.

For example, let’s say we have a matcher m that associates the regex ⌈\w+⌋ with the string '-->one+test<--'. The first time through this while loop,

while (m.find())

m.appendReplacement(sb, "XXX")

the find matches the underlined portion of ‘ ’.

’.

The first call, then, to appendReplacement fills the result string buffer sb with the text before the match, ‘-->’, then bypasses whatever matched, instead appending the replacement string, 'XXX', to sb.

The second time through the loop, find matches ‘ ’. The call to

’. The call to appendReplacement appends the text before the match, ‘+’, then again appends the replacement string, 'XXX'.

This leaves sb with '-->XXX+XXX', and the original target string within the m object marked at  .

.

We’re now in a position to use the appendTail method, presented next.

StringBuffer appendTail(StringBuffer result)

Called after all matches have been found (or, at least, after the desired matches have been found — you can stop early if you like), this method appends the remaining text from the matcher’s target text to the provided stringbuffer.

Continuing the previous example,

m.appendTail(sb)

appends ‘<--’ to sb. This leaves it with ‘ -->XXX+XXX<--’, completing the search and replace.

Search-and-replace examples

Here’s an example showing how you might implement your own version of replaceAll. (Not that you’d want to, but it’s illustrative.)

public static String replaceAll(Matcher m, String replacement)

{

m.reset(); // Be sure to start with a fresh Matcher object

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer(); // We'll build the updated copy here

while (m.find())

m.appendReplacement(result, replacement);

m.appendTail(result);

return result.toString(); // Convert result to a string and return

}

As with the real replaceAll method, this code does not respect the region ( 384), but rather resets it prior to the search-and-replace operation.

384), but rather resets it prior to the search-and-replace operation.

To remedy that deficiency, here is a version of replaceAll that does respect the region. Changed or added sections of code are highlighted:

public static String replaceAllRegion(Matcher m, String replacement)

{

Integer start = m.regionStart();

Integer end = m.regionEnd();

m.reset().region(start, end); // Reset the matcher, but then restor e the region

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer(); // We'll build the updated copy here

while (m.find())

m.appendReplacement(result, replacement);

m.appendTail(result);

return result.toString(); // Convert to a String and return

}

The combination of the reset and region methods in one expression is an example of method chaining, which is discussed starting on page 389.

This next example is sightly more involved; it prints a version of the string in the variable metric, with Celsius temperatures converted to Fahrenheit:

// Build a matcher to find numbers followed by "C" within the variable "Metric"

// The following regex is: ⌈( \d+(?:\.\d+)? )C\b⌋

Matcher m = Pattern.compile("(\\d+(?:\\.\\d+)?)C\\b").matcher(metric);

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer(); // We'll build the updated copy here

while (m.find())

{

float celsius = Float.parseFloat(m.group(1)); // Get the number, as a number

int fahrenheit = (int) (celsius + 9/5 + 32); // Convert to a Fahrenheit value

m.appendReplacement(result, fahrenheit + "F"); // Insert it

}

m.appendTail(result);

System.out.println(result.toString()); // Display the result

For example, if the variable metric contains 'from 3 6.3C to 40.1C.', it displays 'from 97F to 104F.'.

In-Place Search and Replace

So far, we’ve applied java.util.regex to only String objects, but since a matcher can be created with any object that implements the CharSequence interface, we can actually work with text that we can modify directly, in place, and on the fly.

StringBuffer and StringBuilder are commonly used classes that implement CharSequence, the former being multithread safe but less efficient. Both can be used like a String object, but, unlike a String, they can also can be modified. Examples in this book use StringBuilder, but feel free to use StringBuffer if coding for a multithreaded environment.

Here’s a simple example illustrating a search through a StringBuilder object, with all-uppercase words being replaced by their lowercase counterparts†

StringBuilder text = new StringBuilder("It's SO very RUDE to shout!");

Matcher m = Pattern.compile("\\b[\\p{Lu}\\p{Lt}]+\\b").matcher(text);

while (m.find())

text.replace(m.start(), m.end(), m.group().toLowerCase());

System.out.println(text);

This produces:

It's so very rude to shout!

Two matches result in two calls to text.replace. The first two arguments indicate the span of characters to be replaced (we pass the span that the regex matched), followed by the text to use as the replacement (the lowercase version of what was matched).

As long as the replacement text is the same length as the text being replaced, as is the case here, an in-place search and replace is this simple. Also, the approach remains this simple if only one search and replace is done, rather than the iterative application shown in this example.

Using a different-sized replacement

Processing gets more complicated if the replacement text is a different length than what it replaces. The changes we make to the target are done “behind the back” of the matcher, so its idea of the match pointer (where in the target to begin the next find) can become incorrect.

We can get around this by maintaining the match pointer ourselves, passing it to the find method to have it explicitly begin the search where we know it should. That’s what we do in the following modification of the previous example, where we add <b>···</b> tags around the newly lowercased text:

StringBuilder text = new StringBuilder("It's SO very RUDE to shout!");

Matcher m = Pattern.compile("\\b[\\p{Lu}\\p{Lt}]+\\b").matcher(text);

int matchPointer = 0;// First search begins at the start of the string

while (m.find(matchPointer)) {

matchPointer = m.end(); // Next search starts from wherethis one ended

text.replace(m.start(), m.end(), "<b>"+ m.group().toLowerCase() +"</b>");

matchPointer += 7; // Account for having added '<b>' and '</b>'

}

System.out.println(text);

This produces:

It's <b>so</b> very <b>rude</b> to shout!

The Matcher’s Region

Since Java 1.5, a matcher supports the concept of a changeable region with which you can restrict match attempts to some subset of the target string. Normally, a matcher’s region encompasses the entire target text, but it can be changed on the fly with the region method.

The next example inspects a string of HTML, reporting image tags without an ALT attribute. It uses two matchers that work on the same text (the HTML), but with different regular expressions: one finds image tags, while the other finds ALT attributes.

Although the two matchers are applied to the same string, they’re independent objects that are related only because we use the result of each image-tag match to explicitly isolate the ALT search to the image tag’s body. We do this by using the start- and end-method data from the just-completed image-tag match to set the ALT-matcher’s region, prior to invoking the ALT-matcher’s find.

By isolating the image tag’s body in this way, the ALT search tells us whether the image tag we just found, and not the whole HTML string in general, contains an ALT attribute.

// Matcher to find an image tag. The 'html' variable contains the HTML in question

Matcher mImg = Pattern.compile("(?id)<IMG\\s+(.+?)/?>").matcher(html);

// Matcher to find an ALT attribute (to be applied to an IMG tag's body within the same 'html' variable)

Matcher mAlt = Pattern.compile("(?ix)\\b ALT \\s+ =").matcher(html);

// For each image tag within the html . . .

while (mImg.find()) {

// Restrict the next ALT search to the body of the just-found image tag

mAlt.region( mImg.start(1), mImg.end(1) );

// Report an error if no ALT found, showing the whole image tag found above

if (! mAlt.find())

System.out.println("Missing ALT attribute in: " + mImg.group());

}

It may feel odd to indicate the target text in one location (when the mAlt matcher is created) and its range in another (the mAlt.region call). If so, another option is to create mAlt with a dummy target (an empty string, rather than html) and change the region call to mAlt.reset(html).region(...). The extra call to reset is slightly less efficient, but keeping the setting of the target text in the same spot as the setting of the region may be clearer.

In any case, let me reiterate that if we hadn’t restricted the ALT matcher by setting its region, its find would end up searching the entire string, reporting the useless fact of whether the HTML contained 'ALT=' anywhere at all.

Let’s extend this example so that it reports the line number within the HTML where the offending image tag starts. We’ll do so by isolating our view of the HTML to the text before the image tag, then count how many newlines we can find.

// Matcher to find an image tag. The 'html' variable contains the HTML in question

Matcher mImg = Pattern.compile("(?id)<IMG\\s+(.+?)/?>").matcher(html);

// Matcher to find an ALT attribute (to be applied to an IMG tag's body within the same 'html' variable)

Matcher mAlt = Pattern.compile("(?ix)\\b ALT \\s+ =").matcher(html);

// Matcher to find a newline

Matcher mLine = Pattern.compile("\\n").matcher(html);

// For each image tag within the html . . .

while (mImg.find())

{

// Restrict the next ALT search to the body of the just-found image tag

mAlt.region( mImg.start(1), mImg.end(1) );

// Report an error if no ALT found, showing the whole image tag found above

if (! mAlt.find()) {

// Restrict counting of newlines to the text before the start of the image tag

mLine.region(0, mImg.start());

int lineNum = 1; // The first line is numbered 1

while (mLine.find())

lineNum++; // Each newline bumps up the line number

System.out.println("Missing ALT attribute on line " + lineNum);

}

}

As before, when setting the region for the ALT matcher, we use the start(1) method of the image matcher to identify where in the HTML string the body of the image tag starts. Conversely, when setting the end of the newline-matching region, we use start () because it identifies where the whole image tag begins (which is where we want the newline counting to end).

Points to keep in mind

It’s important to remember that not only do some search-related methods ignore the region, they actually invoke the reset method internally and so revert the region to its “entire text” default.

• Searching methods that respect the region:

matches

lookingAt

find() (the no-argument version)

• Methods that reset the matcher and its region:

find (text) (the one-argument version)

replaceAll

replaceFirst

reset (of course)

Also important to remember is that character offsets in the match-result data (that is, the values reported by start and end methods) are not region-relative values, but always with respect to the start of the entire target.

Setting and inspecting region bounds

Three matcher methods relate to setting and inspecting the region bounds:

Matcher region(int start, int end)

This method sets the matcher’s region to the range of target-text characters between start and end, which are offsets from the beginning of the target text. It also resets the matcher, setting its matchpointer to the start of the region, so the next find invocation begins there.

The region remains in effect until set again, or until one of the reset methods is called (either explicitly, or by one of the methods that invoke it  392).

392).

This method returns the matcher object itself, so it can be used with method chaining ( 389).

389).

This method throws IndexOutOfBoundsException if start or end refer to a point outside the target text, or if start is greater than end.

int regionStart()

Returns the character offset to the start of the matcher’s current region. The default is zero.

int regionEnd()

Returns the character offset to the end of the matcher’s current region. The default is the length of the matcher’s target text.

Because the region method requires both start and end to be explicitly provided, it can be a bit inconvenient when you want to set only one. Table 8-4 offers ways to do so.

Table 8-4: Setting Only One Edge of the Region

Region Start |

Region End |

Java Code |

||||||

set explicitly |

leave unchanged |

|

||||||

leave unchanged |

set explicitly |

|

||||||

set explicitly |

reset to default |

|

||||||

reset to default |

set explicitly |

|

Looking outside the current region

Setting a region to something other than the all-text default normally hides, in every respect, the excluded text from the regex engine. This means, for example, that the start of the region is matched by ⌈^⌋ even though it may not be the start of the target text.

However, it’s possible to open up the areas outside the region to limited inspection. Turning on transparent bounds opens up the excluded text to “looking” constructs (lookahead, lookbehind, and word boundaries), and by turning off anchoring bounds, you can configure the edges of the region to not be considered the start and/or edge of the input (unless they truly are).

The reason one might want to change either of these flags is strongly related to why the region was adjusted from the default in the first place. We had no need to do this in the earlier region examples because of their nature — the region-related searches used neither anchoring nor looking constructs, for example.

But imagine again using a CharBuffer to hold text being edited by the user within your application. If the user does a search or search-and-replace operation, it’s natural to limit the operation to the text after the cursor, so you’d set the region to start at the current cursor position. Imagine further that the user’s cursor is at the marked point in this text:

is much too large to see on foot, so you'll need a car.

is much too large to see on foot, so you'll need a car.

and requests that matches of ⌈\bcar\b⌋ be changed to “automobile.” After setting the region appropriately (to isolate the text to the right of the cursor), you’ll launch the search and perhaps be surprised to find that it matches right there at the start of the region, in ‘ ’. It matches there because the transparent-bounds flag defaults to false, and as such, the ⌈

’. It matches there because the transparent-bounds flag defaults to false, and as such, the ⌈\b⌋ believes that the start of the region is the start of the text. It can’t “see” what comes before the start of the region. Were the transparent-bounds flag set to true, ⌈\b⌋ would see the 's' before the region-starting 'c' and know that ⌈\b⌋ can’t match there.

Transparent bounds

These methods relate to the transparent-bounds flag:

Matcher useTransparentBounds(boolean b)

Sets the matcher’s transparent-bounds flag to true or false, as per the argument. The default is false.

This method returns the matcher object itself, so it can be used with method chaining ( 389).

389).

boolean hasTransparentBounds()

Returns true if transparent bounds are in effect, false otherwise.

The default state of a matcher’s transparent-bounds flag is false, meaning that the region bounds are not transparent to “looking” constructs such as lookahead, lookbehind, and word boundaries. As such, characters that might exist beyond the edges of the region are not seen by the regex engine.† This means that even

though the region start might be placed within a word, ⌈\b⌋ can match at the start of the region — it does not see that a letter exists just before the region-starting letter.

This example illustrates a false (default) transparent-bounds flag:

String regex = "\\bcar\\b"; // ⌈\b car\b\⌋

String text = "Madagascar is best seen by car or bike.";

Matcher m = Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(text);

m.region(7, text.length());

m.find();

System.out.println("Matches starting at character " + m.start());

It produces:

Matches starting at character 7

indicating that a word boundary indeed matched at the start of the region, in the middle of  , despite not being a word boundary at all. The non-transparent edge of the region “spoofed” a word boundary.

, despite not being a word boundary at all. The non-transparent edge of the region “spoofed” a word boundary.

However, adding:

m.useTransparentBounds(true);

before the find call causes the example to produce:

Matches starting at character 27

Because the bounds are now transparent, the engine can see that the character just before the start of the region, 's', is a letter, thereby forbidding ⌈\b⌋ to match there. That’s why a match isn’t found until later, at ‘ .’

.’

Again, the transparent-bounds flag is relevant only when the region has been changed from its “all text” default. Note also that the reset method does not reset this flag.

Anchoring bounds

These methods relate to the anchoring-bounds flag:

Matcher useAnchoringBounds(boolean b)

Sets the matcher’s anchoring-bounds flag to true or false, as per the argument. The default is true.

This method returns the matcher object itself, so it can be used with method chaining ( 389).

389).

boolean hasAnchoringBounds()

Returns true if anchoring bounds are in effect, false otherwise.

The default state of a matcher’s anchoring-bounds flag is true, meaning that the line anchors (^ \A $ \z \z) match at the region boundaries, even if those boundaries have been moved from the start and end of the target string. Setting the flag to false means that the line anchors match only at the true ends of the target string, should the region include them.

One might turn off anchoring bounds for the same kind of reasons that transparent bounds might be turned on, such as to keep the semantics of the region in line with a user’s “the cursor is not at the start of the text” expectations.

As with the transparent-bounds flag, the anchoring-bounds flag is relevant only when the region has been changed from its “all text” default. Note also that the reset method does not reset this flag.

Method Chaining

Consider this sequence, which prepares a matcher and sets some of its options:

Pattern p = Pattern.compile(regex); // Compile regex.

Matcher m = p.matcher(text); // Associate regex with text, creating a Matcher.

m.region(5, text.length()); // Bump start of region five characters forward.

m.useAnchoringBounds(false); // Don't let ⌈^⌋ et al. match at the region start.

m.useTransparentBounds(true); // Let looking constructs see across region edges.

We’ve seen in earlier examples that if we don’t need the pattern beyond the creation of the matcher (which is often the case), we can combine the first two lines:

Matcher m = Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(text);

m.region(5, text.length()); // Bump start of region five characters forward.

m.useAnchoringBounds(false); // Don't let ⌈^⌋ et al. match at the region start.

m.useTransparentBounds(true); // Let looking constructs see across region edges.

However, because the two matcher methods invoked after that are from among those that return the matcher itself, we can combine everything into one line (although presented here on two lines to fit the page):

Matcher m = Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(text).region(5, text.length())

.useAnchoringBounds(false).useTransparentBounds(true);

This doesn’t buy any extra functionality, but it can be quite convenient. This kind of “method chaining” can make action-by-action documentation more difficult to fit in and format neatly, but then, good documentation tends to focus on the why rather than the what, so perhaps this is not such a concern. Method chaining is used to great effect in keeping the code on page 399 clear and concise.

Methods for Building a Scanner

New in Java 1.5 are hitEnd and requireEnd, two matcher methods used primarily in building scanners. A scanner parses a stream of characters into a stream of tokens. For example, a scanner that’s part of a compiler might accept 'var•<•34' and produce the three tokens IDENTIFIER · LESS_THAN · INTEGER.

These methods help a scanner decide whether the results from the just-completed match attempt should be used to decide the proper interpretation of the current input. Generally speaking, a return value of true from either method means that more input is required before a definite decision can be made. For example, if the current input (say, characters being typed by the user in an interactive debugger) is the single character ‘<’, it’s best to wait to see whether the next character is ‘=’ so you can properly decide whether the next token should be LESS_THAN or LESS_THAN_OR_EQUAL.

These methods will likely be of little use to the vast majority of regex-related projects, but when they’re at all useful, they’re invaluable. This occasional invaluableness makes it all the more lamentable that hitEnd has a bug that renders it unreliable in Java 1.5. Luckily, it appears to have been fixed in Java 1.6, and for Java 1.5, there’s an easy workaround described at the end of this section.

The subject of building a scanner is quite beyond the scope of this book, so I’ll limit the coverage of these specialized methods to their definitions and some illustrative examples. (By the way, if you’re in need of a scanner, you might be interested in java.util.Scanner as well.)

boolean hitEnd()

(This method is unreliable in Java 1.5; a workaround is presented on page 392.)

This method indicates whether the regex engine tried to inspect beyond the trailing end of the input during the previous match attempt (regardless of whether that attempt was ultimately successful). This includes the inspection done by boundaries such as ⌈\b⌋ and ⌈$⌋.

If hitEnd returns true, more input could have changed the result (changed failure to success, changed success to failure, or changed the span of text matched). On the other hand, false means that the results from the previous attempt were derived solely from the input the regex engine had to work with, and, as such, appending additional text could not have changed the result.

The common application is that if you have a successful match after which hitEnd is true, you need to wait for more input before committing to a decision. If you have a failed match attempt and hitEnd is true, you’ll want to allow more input to come in, rather than aborting with a syntax error.

boolean requireEnd()

This method, which is meaningful only after a successful match, indicates whether the regex engine relied on the location of the end of the input to achieve that success. Put another way, if requireEnd returns true, additional input could have caused the attempt to fail. If it returns false, additional input could have changed the details of success, but could not have turned success into failure.

Its common application is that if requireEnd is true, you should accept more input before committing to a decision about the input.

Both hitEnd and requireEnd respect the region.

Examples illustrating hitEnd and requireEnd

Table 8-5 shows examples of hitEnd and requireEnd after a lookingAt search. Two expressions are used that, although unrealistically simple on their own, are useful in illustrating these methods.

Table 8-5: hitEnd and requireEnd after a lookingAt search

|

Regex |

Text |

Match |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

true |

true |

2 |

|

|

|

false |

false |

3 |

|

’ |

’ |

true |

false |

4 |

|

|

|

false |

false |

5 |

|

’ |

’ |

false |

false |

6 |

|

|

|

false |

false |

7 |

|

|

no match |

false |

|

8 |

|

|

no match |

true |

|

9 |

|

|

|

true |

true |

10 |

|

|

no match |

true |

|

11 |

|

|

|

true |

true |

12 |

|

|

|

false |

false |

13 |

|

|

|

false |

false |

14 |

|

|

no match |

false |

|

15 |

|

|

no match |

false |

|

The regex in the top half of Table 8-5 looks for a non-negative integer and four comparison operators: greater than, less than, greater-than-or-equal, and less-than-or-equal. The bottom-half regex is even simpler, looking for the words set and setup. Again, these are simple examples, but illustrative.

For example, notice in test 5 that even though the entire target was matched, hitEnd remains false. The reason is that, although the last character in the target was matched, the engine never had to inspect beyond that character (to check for another character or for a boundary).

The hitEnd bug and its workaround

The “hitEnd bug” in Java 1.5 (fixed in Java 1.6)† causes unreliable results from the hitEnd method in one very specific situation: when an optional, single-character regex component is attempted in case-insensitive mode (specifically, when such an attempt fails).

For example, the expression ⌈>=?⌋ in case-insensitive mode (by itself, or as part of a larger expression) tickles the bug because ‘=’ is an optional, single-character component. Another example, ⌈a|an|the⌋ in case-insensitive mode (again, alone or as part of a larger expression) tickles the bug because the ⌈a⌋ alternative is a single character, and being one of several alternatives, is optional.

Other examples include ⌈values?⌋ and ⌈\r?\n\r?\n⌋

The workaround

The workaround is to remove the offending condition, either by turning off case-insensitive mode (at least for the offending subexpression), or to replace the single character with something else, such as a character class.

Using the first approach, ⌈>=?⌋ might become ⌈(?-i:>=? )⌋, which uses a mode-modified span ( 110) to ensure that insensitivity does not apply to the subexpression (which doesn’t benefit from a case insensitivity to begin with, so the workaround is “free” in this case).

110) to ensure that insensitivity does not apply to the subexpression (which doesn’t benefit from a case insensitivity to begin with, so the workaround is “free” in this case).

Using the second approach, ⌈a|an|the⌋ becomes ⌈[aA] |an|the⌋, which preserves any case insensitivity applied via the Pattern.CASE_INSENSITIVE flag.

Other Matcher Methods

These remaining matcher methods don’t fit into the categories already presented:

Matcher reset()

This method reinitializes most aspects of the matcher, throwing away any information about a previously successful match, resetting the position in the input to the start of its text, and resetting its region ( 384) to its “entire text” default. Only the anchoring-bounds and transparent-bounds flags (

384) to its “entire text” default. Only the anchoring-bounds and transparent-bounds flags ( 388) are left unchanged.

388) are left unchanged.

Three matcher methods call reset internally, having the side effect of resetting the region: replaceAll, replaceFirst, and the one-argument form of find.

This method returns the matcher itself, so it can be used with method chaining ( 389).

389).

Matcher reset(CharSequence text)

This method resets the matcher just as reset() does, but also changes the target text to the new String (or any object implementing a CharSequence).

When you want to apply the same regex to multiple chunks of text (for example, to each line while reading a file), it’s more efficient to reset with the new text than to create a new matcher.

This method returns the matcher itself, so it can be used with method chaining ( 389).

389).

Pattern pattern()

A matcher’s pattern method returns the Pattern object associated with the matcher. To see the regular expression itself, use m.pattern().pattern(), which invokes the Pattern object’s (identically named, but quite different) pattern method ( 394).

394).

Matcher usePattern(Pattern p)

Available since Java 1.5, this method replaces the matcher’s associated Pattern object with the one provided. This method does not reset the matcher, thereby allowing you to cycle through different patterns looking for a match starting at the “current position” within the matcher’s text. See the discussion starting on page 399 for an example of this in action.

This method returns the matcher itself, so it can be used with method chaining ( 389).

389).

String toString()

Also added in Java 1.5, this method returns a string containing some basic information about the matcher, which is useful for debugging. The content and format of the string are subject to change, but as of the Java 1.6 beta release, this snippet:

Matcher m = Pattern.compile("(\\w+)").matcher("ABC 123");

System.out.println(m.toString());

m.find();

System.out.println(m.toString());

results in:

java.util.regex.Matcher[pattern=(\w+) region=0,7 lastmatch=]

java.util.regex.Matcher[pattern=(\w+) region=0,7 lastmatch=ABC]

Java 1.4.2’s Matcher class does have a generic toString method inherited from java.lang.Object, but it returns a less useful string along the lines of 'java.util.regex.Matcher@480457'.

Querying a matcher’s target text

The Matcher class doesn’t provide a method to query the current target text, so here’s something that attempts to fill that gap:

// This pattern, used in the function below, is compiled and saved here for efficiency.

static final Pattern pNeverFail = Pattern.compile("^");

// Return the target text associated with a matcher object.

public static String text(Matcher m)

{

// Remember these items so that we can restore them later.

Integer regionStart = m.regionStart();

Integer regionEnd = m.regionEnd();

Pattern pattern = m.pattern();

// Fetch the string the only way the class allows.

String text = m.usePattern(pNeverFail).replaceFirst("");

// Put back what we changed (or might have changed).

m.usePattern(pattern).region(regionStart, regionEnd);

// Return the text

return text;

}

This query uses replaceFirst with a dummy pattern and replacement string to get an unmodified copy of the target text, as a String. In the process, it resets the matcher, but at least takes care to restore the region. It’s not a particularly elegant solution (it’s not particularly efficient, and always returns a String object even though the matcher’s target text might be of a different class), but it will have to suffice until Sun provides a better one.

Other Pattern Methods

In addition to the main compile factories, the Pattern class contains some helper methods:

split

The two forms of this method are covered in detail, starting on the facing page.

String pattern()

This method returns the regular-expression string argument used to create the pattern.

String toString()

This method, added in Java 1.5, is a synonym for the pattern method.

int flags()

This method returns the flags (as an integer) passed to the compile factory when the pattern was created.

static String quote(String text)

This static method, added in Java 1.5, returns a string suitable for use as a regular-expression argument to Pattern.compile that matches the literal text provided as the argument. For example, Pattern.quote("main() ") returns the string '\Qmain()\E', which, when used as a regular expression, is interpreted as ⌈\Qmain () \E⌋, which matches the original argument: 'main()’.

static boolean matches(String regex, CharSequence text)

This static method returns a Boolean indicating whether the regex can exactly match the text (which, as with the argument to the matcher method, can be a String or any object implementing CharSequence  373). Essentially, this is:

373). Essentially, this is:

Pattern.compile(regex).matcher(text).matches() ;

If you need to pass compile options, or gain access to more information about the match than simply whether it was successful, you’ll have to use the methods described earlier.

If this method will be called many times (for instance, from within a loop or other code invoked frequently), you’ll find it much more efficient to precompile the regex into a Pattern object that you then use each time you actually need to use the regex.

Pattern’s split Method, with One Argument

String[] split(CharSequence text)

This pattern method accepts text (a CharSequence) and returns an array of strings from text that are delimited by matches of the pattern’s regex. This functionality is also available via the String class split method.

This trivial example

String[] result = Pattern.compile("\\.").split("209.204.146.22");

returns an array of the four strings ('209', '204', '146', and '22') that are separated by the three matches of ⌈\.⌋ in the text. This simple example splits on only a single character, but you can split on any regular expression. For example, you might approximate splitting a string into “words” by splitting on non-alphanumerics:

String[] result = Pattern.compile("\\W+").split(Text);

When given a string such as  it returns the four strings

it returns the four strings ('What', 's', 'up', and 'Doc') delimited by the three matches of the regex. (If you had non-ASCII text, you’d probably want to use ⌈\P{L}+⌋, or perhaps ⌈[^\p{L}\p{N}_]⌋, as the regex, instead of ⌈\W+⌋  367.)

367.)

Empty elements with adjacent matches

If the regex can match at the beginning of the text, the first string returned by split is an empty string (a valid string, but one that contains no characters). Similarly, if the regex can match two or more times in a row, empty strings are returned for the zero-length text “separated” by the adjacent matches. For example,

String[] result = Pattern.compile("\\s*,\\s*").split(", one, two , ,, 3");

splits on a comma and any surrounding whitespace, returning an array of five strings: an empty string, 'one', 'two', two empty strings, and '3'.

Finally, any empty strings that might appear at the end of the list are suppressed:

String[] result = Pattern.compile(":").split(":xx:");

This produces only two strings: an empty string and 'xx'. To keep trailing empty elements, use the two-argument version of split, described next.

Pattern’s split Method, with Two Arguments

String[] split(CharSequence text, int limit)

This version of the split method provides some control over how many times the pattern is applied, and what is done with any trailing empty elements that might be produced. It is also available via the String class split method.

The limit argument takes on different meanings depending on whether it’s less than zero, zero, or greater than zero.

Split with a limit less than zero

Any limit less than zero means to keep trailing empty elements in the array. Thus,

String[] result = Pattern.compile(":").split(":xx:", -1);

returns an array of three strings (an empty string, 'xx', and another empty string).

Split with a limit of zero

An explicit limit of zero is the same as if there were no limit given, i.e., trailing empty elements are suppressed.

Split with a limit greater than zero

With a limit greater than zero, split returns an array of, at most, limit elements. This means that the regex is applied at most limit - 1 times. (A limit of three, for example, requests three strings separated by two matches.)

After having matched limit - 1 times, checking stops and the remainder of the string (after the final match) is returned as the limitth and final string in the array.

For example, if you have a string with:

Friedl,Jeffrey,Eric Francis,America,Ohio,Rootstown

and want to isolate only the three name components, you’d split the string into four parts (the three name components, and one final “everything else” string):

String[] NameInfo = Pattern.compile(",").split(Text, 4);

// NameInfo[0] is the family name.

// NameInfo[1] is the given name.

// NameInfo[2] is the middle name (or in my case, middle names).

// NameInfo[3] is everything else, which we don't need, so we'll just ignore it.

The reason to limit split in this way is enhanced efficiency—why bother going through the work of finding the rest of the matches, creating new strings, making a larger array, etc., when the results of that work won’t be used? Supplying a limit allows only the required work to be done.

Additional Examples

Adding Width and Height Attributes to Image Tags

This section presents a somewhat advanced example of in-place search and replace that updates HTML to ensure that all image tags have both WIDTH and HEIGHT attributes. (The HTML must be in a StringBuilder, StringBuffer, or other writable CharSequence.)

Having even one image on a web page without both size attributes can make the page appear to load slowly, since the browser must actually fetch such images before it can position items on the page. Having the size within the HTML itself means that the text and other content can be properly positioned immediately, which makes the page-loading experience seem faster to the user.†

When an image tag is found, the program looks within the tag for SRC, WIDTH, and HEIGHT attributes, extracting their values when present. If either the WIDTH or the HEIGHT is missing, the image is fetched to determine its size, which is then used to construct the missing attribute(s).

If neither the WIDTH nor HEIGHT are present in the original tag, the image’s true size is used in creating both attributes. However, if one of the size attributes is already present in the tag, only the other is inserted, with a value that maintains the image’s proper aspect ratio. (For example, if a WIDTH that’s half the true size of the image is present in the HTML, the added HEIGHT attribute will be half the true height; this solution mimics how modern browsers deal with this situation.)

This example manually maintains a match pointer, as we did in the section starting on page 383. It makes use of regions ( 384) and method chaining (

384) and method chaining ( 389) as well. Here’s the code:

389) as well. Here’s the code:

// Matcher for isolating <img> tags

Matcher mImg = Pattern.compile("(?id)<IMG\\s+(.+?)/?>").matcher(html);

// Matchers that isolate the SRC, WIDTH,and HEIGHT attributes within a tag (with very naïve regexes)

Matcher mSrc = Pattern.compile("(?ix)\\bSRC =(\\S+)").matcher(html);

Matcher mWidth = Pattern.compile("(?ix)\\bWIDTH =(\\S+)").matcher(html);

Matcher mHeight = Pattern.compile("(?ix)\\bHEIGHT=(\\S+)").matcher(html);

int imgMatchPointer = 0; // The first search begins at the start of the string

while (mImg.find(imgMatchPointer))

{

imgMatchPointer = mImg.end(); // Next image search starts from wherethis one ended

// Look for our attributes within the body of the just-found image tag

Boolean hasSrc = mSrc.region( mImg.start(1), mImg.end(1) ).find();

Boolean hasHeight = mHeight.region( mImg.start(1), mImg.end(1) ).find();

Boolean hasWidth = mWidth.region( mImg.start(1), mImg.end(1) ).find();

// If we have a SRC attribute, but aremissing WIDTH and/or HEIGHT ...

if (hasSrc && (! hasWidth || ! hasHeight))

{

java.awt.image.BufferedImage i = // this fetches the image

javax.imageio.ImageIO.read(new java.net.URL(mSrc.group(1)));

String size; // Will hold the missing WIDTH and/or HEIGHT attributes

if (hasWidth)

// We're told the width, so compute the height that maintains the proper aspect ratio

size = "height='" + (int)(Integer.parseInt(mWidth.group(1)) *

i.getHeight() / i.getWidth()) + "' ";

else if (hasHeight)

// We're told the height, so compute the width that maintains the proper aspect ratio

size = "width='" + (int)(Integer.parseInt(mHeight.group(1)) *

i.getWidth() / i.getHeight()) + "' ";

else // We're told neither, so just insert the actual size

size = "width='" + i.getWidth() + "' " +

"height='" + i.getHeight() + "' ";

html.insert(mImg.start(1), size); // Update the HTML in place

imgMatchPointer += size.length(); // Account for the new text in mImg's eyes

}

}