9

.NET

Microsoft’s .NET Framework, usable with Visual Basic, C#, and C++ (among other languages), offers a shared regular-expression library that unifies regex semantics among the languages. It’s a full-featured, powerful engine that allows you the maximum flexibility in balancing speed and convenience.†

Each language has a different syntax for handling objects and methods, but those underlying objects and methods are the same regardless of the language, so even complex examples shown in one language directly translate to the other languages of the .NET language suite. Examples in this chapter are shown with Visual Basic.

Reliance on Earlier Chapters Before looking at what’s in this chapter, it’s important to emphasize that it relies heavily on the base material in Chapters 1 through 6. I understand that some readers interested only in .NET may be inclined to start their reading with this chapter, and I want to encourage them not to miss the benefits of the preface (in particular, the typographical conventions) and the earlier chapters: Chapters 1, 2, and 3 introduce basic concepts, features, and techniques involved with regular expressions, while Chapters 4, 5, and 6 offer important keys to regex understanding that directly apply to .NET’s regex engine. Among the important concepts covered in earlier chapters are the base mechanics of how an NFA regex engine goes about attempting a match, greediness, backtracking, and efficiency concerns.

Along those lines, let me emphasize that despite convenient tables such as the one in this chapter on page 407, or, for example, ones in Chapter 3 such as those on pages 114 and 123, this book’s foremost intention is not to be a reference, but a detailed instruction on how to master regular expressions.

This chapter first looks at .NET’s regex flavor, including which metacharacters are supported and how, as well as the special issues that await the .NET programmer. Next is a quick overview of .NET’s regex-related object model, followed by a detailed look at each of the core regex-related classes. It ends with an example of how to build a personal regex library by encapsulating prebuilt regular expressions into a shared assembly.

.NET’s Regex Flavor

.NET has been built with a Traditional NFA regex engine, so all the important NFA-related lessons from Chapters 4, 5, and 6 are applicable. Table 9-1 on the facing page summarizes .NET’s regex flavor, most of which is discussed in Chapter 3.

Certain aspects of the flavor can be modified by match modes ( 110), turned on via option flags to the various functions and constructors that accept regular expressions, or in some cases, turned on and off within the regex itself via ⌈(?mods–mods)⌋ and ⌈(?mods–mods:···)⌋ constructs. The modes are listed in Table 9-2 on page 408.

110), turned on via option flags to the various functions and constructors that accept regular expressions, or in some cases, turned on and off within the regex itself via ⌈(?mods–mods)⌋ and ⌈(?mods–mods:···)⌋ constructs. The modes are listed in Table 9-2 on page 408.

In the table, “raw” escapes like ⌈\w⌋ are shown. These can be used directly in VB.NET string literals ("\w"), and in C# verbatim strings (@"\w"). In languages without regex-friendly string literals, such as C++, each backslash in the regex requires two in the string literal ("\\w"). See “Strings as Regular Expressions” ( 101).

101).

The following additional notes augment Table 9-1:

\b is a character shorthand for backspace only within a character class. Outside of a character class, \b matches a word boundary ( 133).

133).

\x## allows exactly two hexadecimal digits, e.g., ⌈\xFCber⌋ matches ‘über’.

\u#### allows exactly four hexadecimal digits, e.g., ⌈\u00FCber⌋ matches ‘über’, and ⌈\u20AC⌋ matches ‘€’.

As of Version 2.0, .NET Framework character classes support class subtraction, such as ⌈

As of Version 2.0, .NET Framework character classes support class subtraction, such as ⌈[a–z– [aeiou] ]⌋ for non-vowel lowercase ASCII letters ( 125). Within a class, a hyphen followed by a class-like construct subtracts the characters specified by the latter from those specified before the hyphen.

125). Within a class, a hyphen followed by a class-like construct subtracts the characters specified by the latter from those specified before the hyphen.

\w, \d, and \s (and their uppercase counterparts) normally match the full range of appropriate Unicode characters, but change to an ASCII-only mode with the RegexOptions.ECMAScript option ( 412).

412).

In its default mode, \w matches the Unicode properties \p{Ll}, \p{Lu}, \p{Lt}, \p{Lo}, \p{Nd}, and \p{Pc}. Note that this does not include the \p{Lm} property. (See the table on page 123 for the property list.)

Table 9-1: Overview of .NET’s Regular-Expression Flavor

Character Shorthands |

|

|

|

Character Classes and Class-Like Constructs |

|

Classes: |

|

Any character except newline: dot (sometimes any character at all) |

|

|

Class shorthands: |

|

Unicode properties and blocks: |

Anchors and Other Zero-Width Tests |

|

Start of line/string: |

|

End of line/string: |

|

End of previous match: |

|

Word boundary: |

|

Lookaround: |

|

Comments and Mode Modifiers |

|

Mode modifiers: |

|

Mode-modified spans: |

|

Comments: |

|

Grouping, Capturing, Conditional, and Control |

|

Capturing parentheses: |

|

Balanced grouping: |

|

Named capture, backreference: |

|

Grouping-only parentheses: |

|

Atomic grouping: |

|

Alternation: | |

|

Greedy quantifiers: |

|

Lazy quantifiers: |

|

Conditional: |

|

(c) – may also be used within a character class ··· ···  see text see text |

|

In its default mode, \s matches ⌈[ • \f\n\r\t\v\x85\p{Z}]⌋. U+0085 is the Unicode NEXT LINE control character, and \p{Z} matches Unicode “separator” characters ( 122).

122).

\p{···} and \P{···} support standard Unicode properties and blocks, as of Unicode version 4.0.1. Unicode scripts are not supported.

Block names require the 'Is' prefix (see the table on page 125), and only the raw form unadorned with spaces and underscores may be used. For example, \p{Is_Greek_Extended} and \p{Is Greek Extended} are not allowed; \p{IsGreekExtended} is required.

Only the short property names like \p{Lu} are supported — long names like \p{Lowercase_Letter} are not supported. Single-letter properties do require the braces (that is, the \pL shorthand for \p{L} is not supported). See the tables on pages 122 and 123.

The special composite property \p{L&} is not supported, nor are the special properties \p{All}, \p{Assigned}, and \p{Unassigned}. Instead, you might use ⌈(?s: . )⌋, ⌈\P{Cn}⌋, and \p{Cn} respectively.

\G matches the end of the previous match, despite the documentation’s claim that it matches at the beginning of the current match ( 130).

130).

Both lookahead and lookbehind can employ arbitrary regular expressions. As of this writing, the .NET regex engine is the only one that I know of that allows lookbehind with a subexpression that can match an arbitrary amount of text (

Both lookahead and lookbehind can employ arbitrary regular expressions. As of this writing, the .NET regex engine is the only one that I know of that allows lookbehind with a subexpression that can match an arbitrary amount of text ( 133).

133).

The

The RegexOptions.ExplicitCapture option (also available via the (?n) mode modifier) turns off capturing for raw ⌈(···)⌋ parentheses. Explicitly named captures like ⌈(?< num> \d+)⌋ still work ( 138). If you use named captures, this option allows you to use the visually more pleasing ⌈(···)⌋ for grouping instead of ⌈

138). If you use named captures, this option allows you to use the visually more pleasing ⌈(···)⌋ for grouping instead of ⌈(?:···)⌋.

Table 9-2: The .NET Match and Regex Modes

|

|

Description |

|

|

Causes dot to match any character ( |

|

|

Expands where ⌈^⌋ and ⌈$⌋ can match ( |

|

|

Sets free-spacing and comment mode ( |

|

|

Turns on case-insensitive matching. |

|

|

Turns capturing off for ⌈ |

|

|

Restricts ⌈ |

|

|

The transmission applies the regex normally, but in the opposite direction (starting at the end of the string and moving toward the start). Unfortunately, buggy ( |

|

|

Spends extra time up front optimizing the regex so it matches more quickly when applied ( |

Additional Comments on the Flavor

A few issues merit longer discussion than a bullet point allows.

Named capture

.NET supports named capture ( 138), through the ⌈

138), through the ⌈(?< name> ···)⌋ or ⌈(?'name’···)⌋ syntax. Both syntaxes mean the same thing and you can use either freely, but I prefer the syntax with < ···>, as I believe it will be more widely used.

You can backreference the text matched by a named capture within the regex with ⌈\k< name> ⌋ or ⌈\k' name'⌋.

After the match (once a Match object has been generated; an overview of .NET’s object model follows, starting on page 416), the text matched within the named capture is available via the Match object’s Groups (name) property. (C# requires Groups [name] instead.)

Within a replacement string ( 424), the results of named capture are available via a

424), the results of named capture are available via a $ {name} sequence.

In order to allow all groups to be accessed numerically, which may be useful at times, named-capture groups are also given numbers. They receive their numbers after all the non-named ones receive theirs:

1 1 3 3 2 2

⌈(\w) (?< Num> \d+)(\s+)⌋

The text matched by the ⌈\d+⌋ part of this example is available via both Groups ("Num") and Groups (3). It’s still just one group, but with two names.

An unfortunate consequence

It’s not recommended to mix normal capturing parentheses and named captures, but if you do, the way the capturing groups are assigned numbers has important consequences that you should be aware of. The ordering becomes important when capturing parentheses are used with Split ( 425), and for the meaning of ‘

425), and for the meaning of ‘$+’ in a replacement string ( 424).

424).

Conditional tests

The if part of an ⌈(?if then | else)⌋ conditional ( 140) can be any type of lookaround, or a captured group number or captured group name in parentheses. Plain text (or a plain regex) in this location is automatically treated as positive lookahead (that it, it has an implicit ⌈

140) can be any type of lookaround, or a captured group number or captured group name in parentheses. Plain text (or a plain regex) in this location is automatically treated as positive lookahead (that it, it has an implicit ⌈(?=···) wrapped around it). This can lead to an ambiguity: for instance, the ⌈(Num)⌋ of ⌈···(?(Num) then | else) ····⌋ is turned into ⌈(?=Num)⌋ (lookahead for ‘Num’) if there is no ⌈(?< Num> ··· )⌋ named capture elsewhere in the regex. If there is such a named capture, whether it was successful is the result of the if.

I recommend not relying on “auto-lookaheadification.” Use the explicit ⌈(?=···)⌋ to make your intentions clearer to the human reader, and also to avert a surprise if some future version of the regex engine adds additional if syntax.

“Compiled” expressions

In earlier chapters, I use the word “compile” to describe the pre-application work any regex system must do to check that a regular expression is valid, and to convert it to an internal form suitable for its actual application to text. For this, .NET regex terminology uses the word “parsing.” It uses two versions of “compile” to refer to optimizations of that parsing phase.

Here are the details, in order of increasing optimization:

- Parsing The first time a regex is seen during the run of a program, it must be checked and converted into an internal form suitable for actual application by the regex engine. This process is referred to as “compile” elsewhere in this book (

241).

241). - On-the-Fly Compilation

RegexOptions.Compiledis one of the options available when building a regex. Using it tells the regex engine to go further than simply converting to the default internal form, but to compile it to low-level MSIL (Microsoft Intermediate Language) code, which itself is then amenable to being optimized even further into even faster native machine code by the JIT (“Just-In-Time” compiler) when the regex is actually applied.It takes more time and memory to do this, but it allows the resulting regular expression to work faster. These tradeoffs are discussed later in this section.

- Pre-Compiled Regexes A

Regexobject (or objects) can be encapsulated into an assembly written to disk in a DLL (a Dynamically Loaded Library, i.e., a shared library). This makes it available for general use in other programs. This is called “compiling the assembly.” For more, see “Regex Assemblies” ( 434).

434).

When considering on-the-fly compilation with RegexOptions.Compiled, there are important tradeoffs among initial startup time, ongoing memory usage, and regex match speed:

Metric |

Without |

With |

Startup time |

Faster |

Slower (by 60x) |

Memory usage |

Low |

High (about 5-15k each) |

Memory usage |

Not as fast |

Up to 10× faster |

The initial regex parsing (the default kind, without RegexOptions.Compiled) that must be done the first time each regex is seen in the program is relatively fast. Even on my clunky old 550MHz NT box, I benchmark about 1,500 complex compilations/second. When RegexOptions.Compiled is used, that goes down to about 25/second, and increases memory usage by about 10k bytes per regex.

More importantly, that memory remains used for the life of the program — there’s no way to unload it.

It definitely makes sense to use RegexOptions.Compiled in time-sensitive areas where processing speed is important, particularly for expressions that work with a lot of text. On the other hand, it makes little sense to use it on simple regexes that aren’t applied to a lot of text. It’s less clear which is best for the multitude of situations in between—you’ll just have to weight the benefits and decide on a case-by-case basis.

In some cases, it may make sense to encapsulate an application’s compiled expressions into its own DLL, as pre-compiled Regex objects. This uses less memory in the final program (the loading of the whole regex compilation package is bypassed), and allows faster loading (since they’re compiled when the DLL is built, you don’t have to wait for them to be compiled when you use them). A nice byproduct of this is that the expressions are made available to other programs that might wish to use them, so it’s a great way to make a personal regex library. See “Creating Your Own Regex Library With an Assembly” on page 435.

Right-to-left matching

The concept of “backwards” matching (matching from right to left in a string, rather than from left to right) has long intrigued regex developers. Perhaps the biggest issue facing the developer is to define exactly what “right-to-left matching” really means. Is the regex somehow reversed? Is the target text flipped? Or is it just that the regex is applied normally from each position within the target string, with the difference being that the transmission starts at the end of the string instead of at the beginning, and moves backwards with each bump-along rather than forward?

Just to think about it in concrete terms for a moment, consider applying ⌈\d+⌋ to the string ‘123 • and • 456’. We know a normal application matches ‘123’, and instinct somehow tells us that a right-to-left application should match ‘456’. However, if the regex engine uses the semantics described at the end of the previous paragraph, where the only difference is the starting point of the transmission and the direction of the bump-along, the results may be surprising. In these semantics, the regex engine works normally (“looking” to the right from where it’s started), so the first attempt of ⌈\d+⌋, at ‘ ’, doesn’t match. The second attempt, at ‘

’, doesn’t match. The second attempt, at ‘ ’ does match, as the bump-along has placed it “looking at” the ‘

’ does match, as the bump-along has placed it “looking at” the ‘6’, which certainly matches ⌈\d+⌋. So, we have a final match of only the final ‘6’.

One of .NET’s regex options is RegexOptions.RightToLeft. What are its semantics? The answer is: “that’s a good question.” The semantics are not documented, and my own tests indicate only that I can’t pin them down. In many cases, such as the ‘123 • and • 456’ example, it acts surprisingly intuitively (it matches ‘456’).

However, it sometimes fails to find any match, and at other times finds a match that seems to make no sense when compared with other results.

If you have a need for it, you may find that RegexOptions.RightToLeft seems to work exactly as you wish, but in the end, you use it at your own risk.

Backslash-digit ambiguities

When a backslash is followed by a number, it’s either an octal escape or a backreference. Which of the two it’s interpreted as, and how, depends on whether the RegexOptions.ECMAScript option has been specified. If you don’t want to have to understand the subtle differences, you can always use ⌈\k<num>⌋ for a backreference, or start the octal escape with a zero (e.g., ⌈\08⌋) to ensure it’s taken as one. These work consistently, regardless of RegexOptions.ECMAScript being used or not.

If RegexOptions.ECMAScript is not used, single-digit escapes from ⌈\1⌋ through ⌈\9⌋ are always backreferences, and an escaped number beginning with zero is always an octal escape (e.g., ⌈\012⌋ matches an ASCII linefeed character). If it’s not either of these cases, the number is taken as a backreference if it would “make sense” to do so (i.e., if there are at least that many capturing parentheses in the regex). Otherwise, so long as it has a value between \000 and \377, it’s taken as an octal escape. For example, ⌈\12⌋ is taken as a backreference if there are at least 12 sets of capturing parentheses, or an octal escape otherwise.

The semantics for when RegexOptions.ECMAScript is specified is described in the next section.

ECMAScript mode

ECMAScript is a standardized version of JavaScript† with its own semantics of how regular expressions should be parsed and applied. A .NET regex attempts to mimic those semantics if created with the RegexOptions.ECMAScript option. If you don’t know what ECMAScript is, or don’t need compatibility with it, you can safely ignore this section.

When RegexOptions.ECMAScript is in effect, the following apply:

- Only the following may be combined with

RegexOptions.ECMAScript:RegexOptions.IgnoreCase

RegexOptions.Multiline

RegexOptions.Compiled \w,\d, and\s(and\W,\D, and\S) change to ASCII-only matching.- When a backslash-digit sequence is found in a regex, the ambiguity between backreference and octal escape changes to favor a backreference, even if that means having to ignore some of the trailing digits. For example, with ⌈(···)

\10⌋, the ⌈\10⌋ is taken as a backreference to the first group, followed by a literal ‘0’.

Using .NET Regular Expressions

.NET regular expressions are powerful, clean, and provided through a complete and easy-to-use class interface. But as wonderful a job that Microsoft did building the package, the documentation is just the opposite — it’s horrifically bad. It’s woefully incomplete, poorly written, disorganized, and sometimes even wrong. It took me quite a while to figure the package out, so it’s my hope that the presentation in this chapter makes the use of .NET regular expressions clear for you.

Regex Quickstart

You can get quite a bit of use out of the .NET regex package without even knowing the details of its regex class model. Knowing the details lets you get more information more efficiently, but the following are examples of how to do simple operations without explicitly creating any classes. These are just examples; all the details follow shortly.

Any program that uses the regex library must have the line

Imports System.Text.RegularExpressions

at the beginning of the file ( 415), so these examples assume that’s there.

415), so these examples assume that’s there.

The following examples all work with the text in the String variable TestStr. As with all examples in this chapter, names I’ve chosen are in italic.

Quickstart: Checking a string for match

This example simply checks to see whether a regex matches a string:

If Regex.IsMatch(TestStr, "^\s+$")

Console.WriteLine("line is empty")

Else

Console.WriteLine("line is not empty")

End If

This example uses a match option:

If Regex.IsMatch(TestStr, "^subject:", RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)

Console.WriteLine("line is a subject line")

Else

Console.WriteLine("line is not a subject line")

End If

Quickstart: Matching and getting the text matched

This example identifies the text actually matched by the regex. If there’s no match, TheNum is set to an empty string.

Dim TheNum as String = Regex.Match (TestStr, "\d+").Value

If TheNum < > ""

Console.WriteLine("Number is: " & TheNum)

End If

This example uses a match option:

Dim ImgTag as String = Regex.Match(TestStr, "< img\b[^> ]*> ", _

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase).Value

If ImgTag < > ""

Console.WriteLine("Image tag: " & ImgTag)

End If

Quickstart: Matching and getting captured text

This example gets the first captured group (e.g., $1) as a string:

Dim Subject as String = _

Regex.Match(TestStr, "^Subject: (.+)").Groups(1).Value

If Subject < > ""

Console.WriteLine("Subject is: " & Subject)

End If

Note that C# uses Groups[1] instead of Groups(1).

Here’s the same thing, using a match option:

Dim Subject as String = _

Regex.Match(TestStr, "^subject: (.*)", _

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase).Groups(1).Value

If Subject < > ""

Console.WriteLine("Subject is: " & Subject)

End If

This example is the same as the previous, but using named capture:

Dim Subject as String = _

Regex.Match(TestStr, "^subject: (?< Subj> .*)", _

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase).Groups("Subj").Value

If Subject < > ""

Console.WriteLine("Subject is: " & Subject)

End If

Quickstart: Search and replace

This example makes our test string “safe” to include within HTML, converting characters special to HTML into HTML entities:

TestStr = Regex.Replace(TestStr, "& ", "& amp")

TestStr = Regex.Replace(TestStr, "< ", "& lt")

TestStr = Regex.Replace(TestStr, "> ", "& gt")

Console.WriteLine("Now safe in HTML: " & TestStr)

The replacement string (the third argument) is interpreted specially, as described in the sidebar on page 424. For example, within the replacement string, ‘$& ‘is replaced by the text actually matched by the regex. Here’s an example that wraps <B> ···< /B> around capitalized words:

TestStr = Regex.Replace(TestStr, "\b> [A-Z]\w*", "<B> $& < /B> ")

Console.WriteLine("Modified string: " & TestStr)

This example replaces <B> ···< /B> (in a case-insensitive manner) with "< I> ···< /I>:

TestStr = Regex.Replace(TestStr, "< b> (.*?)< /b> ", "< I> $1< /I> ", _

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)

Console.WriteLine("Modified string: " & TestStr)

Package Overview

You can get the most out .NET regular expressions by working with its rich and convenient class structure. To give us an overview, here’s a complete console application that shows a simple match using explicit objects:

Option Explicit On ' These are not specifically required to use regexes,

Option Strict On ' but their use is good general practice.

' Make regex-related classes easily available.

Imports System.Text.RegularExpressions

Module SimpleTest

Sub Main()

Dim SampleText as String = "this is the 1st test string"

Dim R as Regex = New Regex("\d+\w+") 'Compile the pattern.

Dim M as Match = R.match(SampleText) 'Check against a string.

If not M.Success

Console.WriteLine("no match")

Else

Dim MatchedText as String = M.Value'Query the results . . .

Dim MatchedFrom as Integer = M.Index

Dim MatchedLen as Integer = M.Length

Console.WriteLine("matched [" & MatchedText & "]" & _

" from char#" & MatchedFrom.ToString() & _

" for " & MatchedLen.ToString() & " chars.")

End If

End Sub

End Module

When executed from a command prompt, it applies ⌈\d+\w+⌋ to the sample text and displays:

matched [1st] from char#12 for 3 chars.

Importing the regex namespace

Notice the Imports System.Text.RegularExpressions line near the top of the program? That’s required in any VB program that wishes to access the .NET regex objects, to make them available to the compiler.

The analogous statement in C# is:

using System.Text.RegularExpressions; // This is for C#

The example shows the use of the underlying raw regex objects. The two main action lines:

Dim R as Regex = New Regex("\d+\w+") 'Compile the pattern.

Dim M as Match = R.Match(SampleText) 'Check against a string.

can also be combined, as:

Dim M as Match = Regex.Match(SampleText, "\d+\w+") 'Check pattern against string.

The combined version is easier to work with, as there’s less for the programmer to type, and less objects to keep track of. It does, however, come with at a slight efficiency penalty ( 432). Over the coming pages, we’ll first look at the raw objects, and then at the “convenience” functions such as the

432). Over the coming pages, we’ll first look at the raw objects, and then at the “convenience” functions such as the Regex.Match static function, and when it makes sense to use them.

For brevity’s sake, I’ll generally not repeat the following lines in examples that are not complete programs:

Option Explicit On

Option Strict On

Imports System.Text.RegularExpressions

It may also be helpful to look back at some of VB examples earlier in the book, on pages 96, 99, 204, 219, and 237.

Core Object Overview

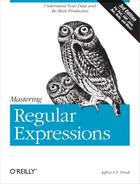

Before getting into the details, let’s first take a step back and look the .NET regex object model. An object model is the set of class structures through which regex functionality is provided. .NET regex functionality is provided through seven highly-interwoven classes, but in practice, you’ll generally need to understand only the three shown visually in Figure 9-1 on the facing page, which depicts the repeated application of ⌈\s+(\d+)⌋ to the string ‘May• 16,• 1998’.

Regex objects

The first step is to create a Regex object, as with:

Dim R as Regex = New Regex("\s+(\d+)")

Here, we’ve made a regex object representing ⌈\s+(\d+)⌋ and stored it in the R variable. Once you’ve got a Regex object, you can apply it to text with its Match (text) method, which returns information on the first match found:

Dim M as Match = R.Match("May 16, 1998")

Figure 9-1: .NET’s Regex-related object model

Match objects

A Regex object’s Match(···) method provides information about a match result by creating and returning a Match object. A Match object has a number of properties, including Success (a Boolean value indicating whether the match was successful) and Value (a copy of the text actually matched, if the match was successful). We’ll look at the full list of Match properties later.

Among the details you can get about a match from a Match object is information about the text matched within capturing parentheses. The Perl examples in earlier chapters used Perl’s $1 variable to get the text matched within the first set of capturing parentheses. .NET offers two methods to retrieve this data: to get the raw text, you can index into a Match object’s Groups property, such as with Groups (1) .Value to get the equivalent of Perl’s $1. (Note: C# requires a different syntax, Groups[1].Value, instead.) Another approach is to use the Result method, which is discussed starting on page 429.

Group objects

The Groups(1) part in the previous paragraph actually references a Group object, and the subsequent .Value references its Value property (the text associated with the group). There is a Group object for each set of capturing parentheses, and a “virtual group,” numbered zero, which holds the information about the overall match.

Thus, MatchObj.Value and MatchObj.Groups(O).Value are the same — a copy of the entire text matched. It’s more concise and convenient to use the first, shorter approach, but it’s important to know about the zeroth group because MatchObj.Groups.Count (the number of groups known to the Match object) includes it. The MatchObj.Groups.Count resulting from a successful match with ⌈\s+ (\d+)⌋ is two (the whole-match “zeroth” group, and the $1 group).

Capture objects

There is also a Capture object. It’s not used often, but it’s discussed starting on page 437.

All results are computed at match time

When a regex is applied to a string, resulting in a Match object, all the results (where it matched, what each capturing group matched, etc.) are calculated and encapsulated into the Match object. Accessing properties and methods of the Match object, including its Group objects (and their properties and methods) merely fetches the results that have already been computed.

Core Object Details

Now that we’ve seen an overview, let’s look at the details. First, we’ll look at how to create a Regex object, followed by how to apply it to a string to yield a Match object, and how to work with that object and its Group objects.

In practice, you can often avoid having to explicitly create a Regex object, but it’s good to be comfortable with them, so during this look at the core objects, I’ll always explicitly create them. We’ll see later what shortcuts .NET provides to make things more convenient.

In the lists that follow, I don’t mention little-used methods that are merely inherited from the Object class.

Creating Regex Objects

The constructor for creating a Regex object is uncomplicated. It accepts either one argument (the regex, as a string), or two arguments (the regex and a set of options). Here’s a one-argument example:

Dim StripTrailWS = new Regex("\s+$") 'for removing trailing whitespace

This just creates the Regex object, preparing it for use; no matching has been done to this point.

Here’s a two-argument example:

Dim GetSubject = new Regex(""subject: (.*)", RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)

That passes one of the RegexOptions flags, but you can pass multiple flags if they’re OR’d together, as with:

Dim GetSubject = new Regex("^subject: (.*)", _

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase OR RegexOptions.Multiline)

Catching exceptions

An ArgumentException error is thrown if a regex with an invalid combination of metacharacters is given. You don’t normally need to catch this exception when using regular expressions you know to work, but it’s important to catch it if using regular expressions from “outside” the program (e.g., entered by the user, or read from a configuration file). Here’s an example:

Dim R As Regex

Try

R = New Regex(SearchRegex)

Catch e As ArgumentException

Console.WriteLine("*ERROR* bad regex: " & e.ToString)

Exit Sub

End Try

Of course, depending on the application, you may want to do something other than writing to the console upon detection of the exception.

Regex options

The following option flags are allowed when creating a Regex object:

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase

This option indicates that when the regex is applied, it should be done in a case-insensitive manner ( 110).

110).

RegexOptions.IgnorePatternWhitespace

This option indicates that the regex should be parsed in a free-spacing and comments mode ( 111). If you use raw ⌈#···⌋ comments, be sure to include a newline at the end of each logical line, or the first raw comment “comments out” the entire rest of the regex.

111). If you use raw ⌈#···⌋ comments, be sure to include a newline at the end of each logical line, or the first raw comment “comments out” the entire rest of the regex.

In VB.NET, this can be achieved with chr(l0), as in this example:

Dim R as Regex = New Regex( _

"# Match a floating-point number ... " & chr(10) & _

" \d+(?:\.\d+)? # with a leading digit... " & chr(10) & _

" ; # or ... " & chr(10) & _

" \.\d+ # with a leading decimal point", _

RegexOptions.IgnorePatternWhitespace)

That’s cumbersome; in VB.NET, ⌈(?#···) comments can be more convenient:

Dim R as Regex = New Regex( _

"(?# Match a floating-point number ... )" & _

" \d+(?:\.\d+)? (?# with a leading digit... )" & _

" | (?# or ... )" & _

" \.\d+ (?# with a leading decimal point )", _

RegexOptions.IgnorePatternWhitespace)

RegexOptions.Multiline

This option indicates that the regex should be applied in an enhanced line-anchor mode ( 112). This allows ⌈

112). This allows ⌈^⌋ and ⌈$⌋ to match at embedded newlines in addition to the normal beginning and end of string, respectively.

RegexOptions.Singleline

This option indicates that the regex should be applied in a dot-matches-all mode ( 111). This allows dot to match any character, rather than any character except a newline.

111). This allows dot to match any character, rather than any character except a newline.

RegexOptions.ExplicitCapture

This option indicates that even raw ⌈(···) parentheses, which are normally capturing parentheses, should not capture, but rather behave like ⌈(?:···)⌋ grouping-only non-capturing parentheses. This leaves named-capture ⌈(?<name> ···)⌋ parentheses as the only type of capturing parentheses.

If you’re using named capture and also want non-capturing parentheses for grouping, it makes sense to use normal ⌈(···)⌋ parentheses and this option, as it keeps the regex more visually clear.

RegexOptions.RightToLeft

This option sets the regex to a right-to-left match mode ( 411).

411).

RegexOptions.Compiled

This option indicates that the regex should be compiled, on the fly, to a highly-optimized format, which generally leads to much faster matching. This comes at the expense of increased compile time the first time it’s used, and increased memory use for the duration of the program’s execution.

If a regex is going to be used just once, or sparingly, it makes little sense to use RegexOptions.Compiled, since its extra memory remains used even when a Regex object created with it has been disposed of. But if a regex is used in a time-critical area, it’s probably advantageous to use this flag.

You can see an example on page 237, where this option cuts the time for one benchmark about in half. Also, see the discussion about compiling to an assembly ( 434).

434).

RegexOptions.ECMAScript

This option indicates that the regex should be parsed in a way that’s compatible with ECMAScript ( 412). If you don’t know what ECMAScript is, or don’t need compatibility with it, you can safely ignore this option.

412). If you don’t know what ECMAScript is, or don’t need compatibility with it, you can safely ignore this option.

RegexOptions.None

This is a “no extra options” value that’s useful for initializing a RegexOptions variable, should you need to. As you decide options are required, they can be OR’d in to it.

Using Regex Objects

Just having a regex object is not useful unless you apply it, so the following methods swing it into action.

RegexObj·IsMatch(target) Return type: Boolean

RegexObj·IsMatch(target, offset)

The IsMatch method applies the object’s regex to the target string, returning a simple Boolean indicating whether the attempt is successful. Here’s an example:

Dim R as RegexObj = New Regex("^\s*$")

*

*

*

If R.IsMatch(Line) Then

' Line is blank ...

*

*

*

Endif

If an offset (an integer) is provided, that many characters in the target string are bypassed before the regex is first attempted.

RegexObj·Match(target) Return type: Match object

RegexObj·Match(target, offset)

RegexObj·Match(target, offset, maxlength)

The Match method applies the object’s regex to the target string, returning a Match object. With this Match object, you can query information about the results of the match (whether it was successful, the text matched, etc.), and initiate the “next” match of the same regex in the string. Details of the Match object follow, starting on page 427.

If an offset (an integer) is provided, that many characters in the target string are bypassed before the regex is first attempted.

If you provide a maxlength argument, it puts matching into a special mode where the maxlength characters starting offset characters into the target string are taken as the entire target string, as far as the regex engine is concerned. It pretends that characters outside the range don’t even exist, so, for example, ⌈^⌋ can match at offset characters into the original target string, and r$ can match at maxlength characters after that. It also means that lookaround can’t “see” the characters outside of that range. This is all very different from when only offset is provided, as that merely influences where the transmission begins applying the regex — the engine still “sees” the entire target string.

This table shows examples that illustrate the meaning of offset and maxlength:

|

Results when RegexObj is built with ... |

||

Method call |

⌈ |

⌈ |

⌈ |

RegexObj |

match ‘ |

fail |

fail |

RegexObj |

match ‘ |

fail |

fail |

RegexObj |

match ‘ |

match ‘ |

match ‘ |

RegexObj·Matches (target) Return type: MatchCollection

RegexObj·Matches (target, offset)

The Matches method is similar to the Match method, except Matches returns a collection of Match objects representing all the matches in the target, rather than just one Match object representing the first match. The returned object is a MatchCollection.

For example, after this initialization:

Dim R as New Regex("Xw+")

Dim Target as String = "a few words"

this code snippet

Dim BunchOfMatches as MatchCollection = R.Matches(Target)

Dim I as Integer

For I = 0 to BunchOfMatches.Count - 1

Dim MatchObj as Match = BunchOfMatches.Item(I)

Console.WriteLine("Match: " & MatchObj.Value)

Next

produces this output:

Match: a

Match: few

Match: words

The following example, which produces the same output, shows that you can dispense with the MatchCollection object altogether:

Dim MatchObj as Match

For Each MatchObj in R.Matches(Target)

Console.WriteLine("Match: " & MatchObj.Value)

Next

Finally, as a comparison, here’s how you can accomplish the same thing another way, with the Match (rather than Matches) method:

Dim MatchObj as Match = R.Match(Target)

While MatchObj.Success

Console.WriteLine("Match: " & MatchObj.Value)

MatchObj = MatchObj.NextMatch()

End While

RegexObj·Replace(target, replacement) Return type: String

RegexObj·Replace(target, replacement, count)

RegexObj·Replace(target, replacement, count, offset)

The Replace method does a search and replace on the target string, returning a (possibly changed) copy of it. It applies the Regex object’s regular expression, but instead of returning a Match object, it replaces the matched text. What the matched text is replaced with depends on the replacement argument. The replacement argument is overloaded; it can be either a string or a MatchEvaluator delegate. If replacement is a string, it is interpreted according to the sidebar on the next page. For example,

Dim R_CapWord as New Regex("\b[A-Z]\w*")

*

*

*

Text = R_CapWord.Replace(Text, "< B> $0< /B>")

wraps each capitalized word with <B> ...</B> .

If count is given, only that number of replacements is done. (The default is to do all replacements). To replace just the first match found, for example, use a count of one. If you know that there will be only one match, using an explicit count of one is more efficient than letting the Replace mechanics go through the work of trying to find additional matches. A count of -1 means “replace all” (which, again, is the default when no count is given).

If an offset (an integer) is provided, that many characters in the target string are bypassed before the regex is applied. Bypassed characters are copied through to the result unchanged.

For example, this canonicalizes all whitespace (that is, reduces sequences of whitespace down to a single space):

Dim AnyWS as New Regex("\s+")

*

*

*

Target = AnyWS.Replace(Target, " ")

This converts 'some• • • • • random• • • • • spacing' to 'some• random• spacing'. The following does the same, except it leaves any leading whitespace alone:

Dim AnyWS as New Regex("\s+")

Dim LeadingWS as New Regex(""\s+")

*

*

*

Target = AnyWS.Replace(Target, " ", -1, LeadingWS.Match(Target).Length)

This converts ‘• • • • • some• • • random• • • • • spacing' to ‘• • • • some• random• spacing'. It uses the length of what’s matched by LeadingWS as the offset (as the count of characters to skip) when doing the search and replace. It uses a convenient feature of the Match object, returned here by LeadingWS.Match(Target), that its Length property may be used even if the match fails. (Upon failure, the Length property has a value of zero, which is exactly what we need to apply AnyWS to the entire target.)

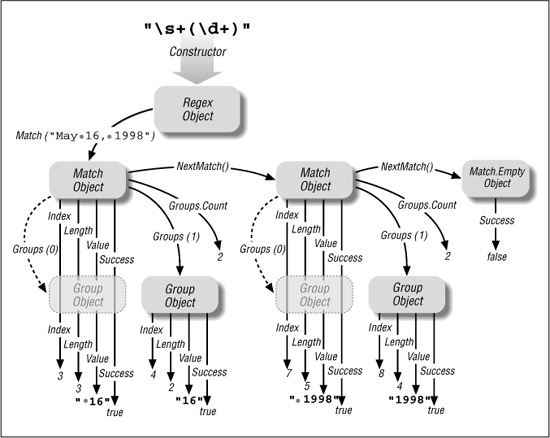

Using a replacement delegate

The replacement argument isn’t limited to a simple string. It can be a delegate (basically, a pointer to a function). The delegate function is called after each match to generate the text to use as the replacement. Since the function can do any processing you want, it’s an extremely powerful replacement mechanism.

The delegate is of the type MatchEvaluator, and is called once per match. The function it refers to should accept the Match object for the match, do whatever processing you like, and return the text to be used as the replacement.

As examples for comparison, the following two code snippets produce identical results:

Both snippets highlight each match by wrapping the matched text in < < ···> > . The advantage of using a delegate is that you can include code as complex as you like in computing the replacement. Here’s an example that converts Celsius temperatures to Fahrenheit:

Function MatchFunc(ByVal M as Match) as String

' Get numeric temperature from $1, then convert to Fahrenheit

Dim Celsius as Double = Double.Parse(M.Groups(1).Value)

Dim Fahrenheit as Double = Celsius * 9/5 + 32

Return Fahrenheit & "F" 'Append an "F", and return

End Function

Dim Evaluator as MatchEvaluator = New MatchEvaluator(AddressOf MatchFunc)

*

*

*

Dim R_Temp as Regex = New Regex("(\d+)C\b", RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)

Target = R_Temp.Replace(Target, Evaluator)

Given 'Temp is 37C.’ in Target, it replaces it with 'Temp is 98.6F.'.

RegexObj·Split (target) Return type: array of String

RegexObj·Split (target, count)

RegexObj·Split (target, count, offset)

The Split method applies the object’s regex to the target string, returning an array of the strings separated by the matches. Here’s a trivial example:

Dim R as New Regex("\.")

Dim Parts as String() = R.Split("209.204.146.22")

The R.Split returns the array of four strings ('209', '204', '146', and '22') that are separated by the three matches of ⌈\.⌋ in the text.

If a count is provided, no more than count strings will be returned (unless capturing parentheses are used — more on that in a bit). If count is not provided, Split returns as many strings as are separated by matches. Providing a count may mean that the regex stops being applied before the final match, and if so, the last string has the unsplit remainder of the line:

Dim R as New Regex("\.")

Dim Parts as String() = R.Split("209.204.146.22", 2)

This time, Parts receives two strings, '209' and '204.146.22'.

If an offset (an integer) is provided, that many characters in the target string are bypassed before the regex is attempted. The bypassed text becomes part of the first string returned (unless RegexOptions.RightToLeft has been specified, in which case the bypassed text becomes part of the last string returned).

Using Split with capturing parentheses

If capturing parentheses of any type are used, additional entries for captured text are usually inserted into the array. (We’ll see in what cases they might not be inserted in a bit.) As a simple example, to separate a string like '2006-12-31' or '04/12/2007' into its component parts, you might split on ⌈[-/]⌋, as with:

Dim R as New Regex("[-/]")

Dim Parts as String() = R.Split(MyDate)

This returns a list of the three numbers (as strings). However, adding capturing parentheses and using ⌈([-/,])⌋ as the regex causes Split to return five strings: if MyDate contains '2006-12-31', the strings are '2006', '-', '12', '-', and '31'. The extra '-' elements are from the per-capture $1.

If there are multiple sets of capturing parentheses, they are inserted in their numerical ordering (which means that all named captures come after all unnamed captures  409).

409).

Split works consistently with capturing parentheses so long as all sets of capturing parentheses actually participate in the match. However, there’s a bug with the current version of .NET such that if there is a set of capturing parentheses that doesn’t participate in the match, it and all higher-numbered sets don’t add an element to the returned list.

As a somewhat contrived example, consider wanting to split on a comma with optional whitespace around it, yet have the whitespace added to the list of elements returned. You might use ⌈(\s+)?, (\s+)?⌋ for this. When applied with Split to 'this• ,• • that', four strings are returned, 'this', ‘• ', ‘• • ', and 'that'. However, when applied to 'this',·'that', the inability of the first set of capturing parentheses to match inhibits the element for it (and for all sets that follow) from being added to the list, so only two strings are returned, 'this' and 'that'. The inability to know beforehand exactly how many strings will be returned per match is a major shortcoming of the current implementation.

In this particular example, you could get around this problem simply by using ⌈(\s*),(\s*)⌋ (in which both groups are guaranteed to participate in any overall match). However, more complex expressions are not easily rewritten.

RegexObj·GetGroupNames()

RegexObj·GetGroupNumbers()

RegexObj·GroupNameFromNumber(number)

RegexObj·GroupNumberFromName(name)

These methods allow you to query information about the names (both numeric and, if named capture is used, by name) of capturing groups in the regex. They don’t refer to any particular match, but merely to the names and numbers of groups that exist in the regex. The sidebar below shows an example of their use.

RegexObj·ToString()

RegexObj·RightToLeft

RegexObj·Options

These allow you to query information about the Regex object itself (as opposed to applying the regex object to a string). The ToString() method returns the pattern string originally passed to the regex constructor. The RightToLeft property returns a Boolean indicating whether RegexOptions.RightToLeft was specified with the regex. The Options property returns the RegexOptions that are associated with the regex. The following table shows the values of the individual options, which are added together when reported:

0 |

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

4 |

|

8 |

|

16 |

|

32 |

|

64 |

|

256 |

|

The missing 128 value is for a Microsoft debugging option not available in the final product.

The sidebar shows an example these methods in use.

Using Match Objects

Match objects are created by a Regex's Match method, the Regex.Match static function (discussed in a bit), and a Match object’s own NextMatch method. It encapsulates all information relating to a single application of a regex. It has the following properties and methods:

MatchObj.Success

This returns a Boolean indicating whether the match was successful. If not, the object is a copy of the static Match.Empty object ( 433).

433).

MatchObj·Value

MatchObj·ToString()

These return copies of the text actually matched.

MatchObj.Length

This returns the length of the text actually matched.

MatchObj.Index

This returns an integer indicating the position in the target text where the match was found. It’s a zero-based index, so it’s the number of characters from the start (left) of the string to the start (left) of the matched text. This is true even if RegexOptions.RightToLeft had been used to create the regex that generated this Match object.

MatchObj.Groups

This property is a GroupCollection object, in which a number of Group objects are encapsulated. It is a normal collection object, with a Count and Item properties, but it’s most commonly accessed by indexing into it, fetching an individual Group object. For example, M.Groups(3) is the Group object related to the third set of capturing parentheses, and M.Groups("HostName") is the group object for the “Hostname” named capture (e.g., after the use of ⌈(?< HostName> ...)⌋ in a regex).

Note that C# requires M.Groups[3] and M.Groups["HostName"] instead.

The zeroth group represents the entire match itself. Matchobj.Groups(0) .Value, for example, is the same as Matchobj.Value.

MatchObj.NextMatch()

The NextMatch() method re-invokes the original regex to find the next match in the original string, returning a new Match object.

MatchObj.Resu1t(string)

Special sequences in the given string are processed as shown in the sidebar on page 424, returning the resulting text. Here’s a simple example:

Dim M as Match = Regex.Match(SomeString, "\w+")

Console.WriteLine(M.Result("The first word is '$& '"))

You can use this to get a copy of the text to the left and right of the match, with

M.Result("$'") 'This is the text to the left of the match

M.Result("$'") 'This is the text to the right of the match

During debugging, it may be helpful to display something along the lines of:

M.Result("[$'< $& > $']"))

Given a Match object created by applying ⌈\d+⌋ to the string 'May 16, 1998', it returns 'May < 16>, 1998', clearly showing the exact match.

MatchObj.Synchronized()

This returns a new Match object that’s identical to the current one, except that it’s safe for multi-threaded use.

MatchObj.Captures

The Captures property is not used often, but is discussed starting on page 437.

Using Group Objects

A Group object contains the match information for one set of capturing parentheses (or, if a zeroth group, for an entire match). It has the following properties and methods:

GroupObj.Success

This returns a Boolean indicating whether the group participated in the match. Not all groups necessarily “participate” in a successful overall match. For example, if ⌈(this)|(that)⌋ matches successfully, one of the sets of parentheses is guaranteed to have participated, while the other is guaranteed to have not. See the footnote on page 139 for another example.

GroupObj·Value

GroupObj·ToString()

These both return a copy of the text captured by this group. If the match hadn’t been successful, these return an empty string.

GroupObj.Length

This returns the length of the text captured by this group. If the match hadn’t been successful, it returns zero.

GroupObj.Index

This returns an integer indicating where in the target text the group match was found. The return value is a zero-based index, so it’s the number of characters from the start (left) of the string to the start (left) of the captured text. (This is true even if RegexOptions.RightToLeft had been used to create the regex that generated this Match object.)

GroupObj.Captures

The Group object also has a Captures property discussed starting on page 437.

Static “Convenience” Functions

As we saw in the “Regex Quickstart” beginning on page 413, you don’t always have to create explicit Regex objects. The following static functions allow you to apply with regular expressions directly:

Regex.IsMatch(target, pattern)

Regex.IsMatch(target, pattern, options)

Regex.Match(target, pattern)

Regex.Match(target, pattern, options)

Regex.Matches(target, pattern)

Regex.Matches(target, pattern, options)

Regex.Replace(target, pattern, replacement)

Regex.Replace(target, pattern, replacement, options)

Regex.Matches(target, pattern)

Regex.Matches(target, pattern, options)

Internally, these are just wrappers around the core Regex constructor and methods we’ve already seen. They construct a temporary Regex object for you, use it to call the method you’ve requested, and then throw the object away. (Well, they don’t actually throw it away—more on this in a bit.)

Here’s an example:

If Regex.IsMatch(Line, "^\s+$")

*

*

*

That’s the same as

Dim TemporaryRegex = New Regex("^\s*$")

If TemporaryRegex.IsMatch(Line)

*

*

*

or, more accurately, as:

If New Regex("^\s*$").IsMatch(Line)

*

*

*

The advantage of using these convenience functions is that they generally make simple tasks easier and less cumbersome. They allow an object-oriented package to appear to be a procedural one ( 95). The disadvantage is that the pattern must be reinspected each time.

95). The disadvantage is that the pattern must be reinspected each time.

If the regex is used just once in the course of the whole program’s execution, it doesn’t matter from an efficiency standpoint whether a convenience function is used. But, if a regex is used multiple times (such as in a loop, or a commonly-called function), there’s some overhead involved in preparing the regex each time ( 241). The goal of avoiding this usually expensive overhead is the primary reason you’d build a

241). The goal of avoiding this usually expensive overhead is the primary reason you’d build a Regex object once, and then use it repeatedly later when actually checking text. However, as the next section shows, .NET offers a way to have the best of both worlds: procedural convenience with object-oriented efficiency.

Regex Caching

Having to always build and manage a separate Regex object for every little regex you’d like to use can be cumbersome and inconvenient, so it’s wonderful that the .NET regex package provides its various static methods. One efficiency downside of the static methods, though, is that each invocation in theory creates a temporary Regex object for you, applies it, and then discards it. That can be a lot of redundant work when done many times for the same regex in a loop.

To avoid that repeated work, the .NET Framework provides caching for the temporary objects created via the static methods. Caching in general is discussed in Chapter 6 ( 244), but in short, this means that if you use the same regex in a static method as you’ve used “recently,” the static method reuses the previously-created regex object rather than building a new one from scratch.

244), but in short, this means that if you use the same regex in a static method as you’ve used “recently,” the static method reuses the previously-created regex object rather than building a new one from scratch.

The default meaning of “recently” is that the most recent 15 regexes are cached. If you use more than 15 regexes in a loop, the benefits of the cache are lost because the 16th regex forces out the first, so that by the time you restart the loop and reapply, the first is no longer in the cache and must be regenerated.

If the default size of 15 is too small for your needs, you can adjust it:

Regex.CacheSize = 123

Should you ever want to disable all caching, you can set the value to zero.

Support Functions

Besides the convenience functions described in the previous section, there are a few other static support functions:

Regex.Escape(string)

Given a string, Regex.Escape(...) returns a copy of the string with regex metacharacters escaped. This makes the original string appropriate for inclusion in a regex as a literal string.

For example, if you have input from the user in the string variable SearchTerm, you might use it to build a regex with:

Dim UserRegex as Regex = New Regex("^" & Regex.Escape(SearchTerm) & "$", _

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)

This allows the search term to contain regular-expression metacharacters without having them treated as such. If not escaped, a SearchTerm value of, say, ':-)' would result in an ArgumentException being thrown ( 419).

419).

Regex.Unescape(string)

This odd little function accepts a string, and returns a copy with certain regex character escape sequences interpreted, and other backslashes removed. For example, if it’s passed '\:\-\)', it returns ': -)'.

Character shorthands are also decoded. If the original string has '\n', it’s actually replaced with a newline in the returned string. Or if it has '\u1234', the corresponding Unicode character will be inserted into the string. All character shorthands listed at the top of page 407 are interpreted.

I can’t imagine a good regex-related use for Regex.Unescape, but it may be useful as a general tool for endowing VB strings with some knowledge of escapes.

Match.Empty

This function returns a Match object that represents a failed match. It is perhaps useful for initializing a Match object that you may or may not fill in later, but do intend to query later. Here’s a simple example:

Dim SubMatch as Match = Match.Empty 'Initialize, in case it's not set in the loop below

*

*

*

Dim Line as String

For Each Line in EmailHeaderLines

'If this is the subject, save the match info for later . . .

Dim ThisMatch as Match = Regex.Match(Line, "^Subject:\s*(.*)", _

RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)

If ThisMatch.Success

SubMatch = ThisMatch

End If

*

*

*

Next

*

*

*

If SubMatch.Success

Console.WriteLine(SubMatch.Result("The subject is: $1"))

Else

Console.WriteLine("No subject!")

End If

If the string array EmailHeaderLines actually has no lines (or no Subject lines), the loop that iterates through them won’t ever set SubMatch, so the inspection of SubMatch after the loop would result in a null reference exception if it hadn’t somehow been initialized. So, it’s convenient to use Match.Empty as the initializer in cases like this.

Regex.CompileToAssembly(...)

This allows you to create an assembly encapsulating a Regex object—see the next section.

Advanced .NET

The following pages cover a few features that haven’t fit into the discussion so far: building a regex library with regex assemblies, using an interesting .NET-only regex feature for matching nested constructs, and a discussion of the Capture object.

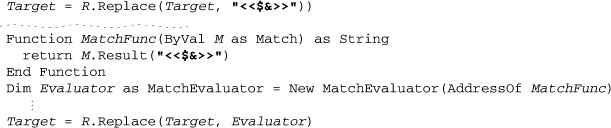

Regex Assemblies

.NET allows you to encapsulate Regex objects into an assembly, which is useful in creating a regex library. The example in the sidebar on the facing page shows how to build one.

When the sidebar example executes, it creates the file JfriedlsRegexLibrary.DLL in the project’s bin directory.

I can then use that assembly in another project, after first adding it as a reference via Visual Studio .NET’s Project > Add Reference dialog.

To make the classes in the assembly available, I first import them:

Imports jfriedl

I can then use them just like any other class, as in this example::

In this example, I chose to import only from the jfriedl namespace, but could have just as easily imported from the jfriedl.CSV namespace, which then would allow the Regex object to be created with:

Dim FieldRegex as GetField = New GetField ' This makes a new Regex object

The difference is mostly a matter of style.

You can also choose to not import anything, but rather use them directly:

Dim FieldRegex as jfriedl.CSV.GetField = New jfriedl.CSV.GetField

This is a bit more cumbersome, but documents clearly where exactly the object is coming from. Again, it’s a matter of style.

Matching Nested Constructs

Microsoft has included an interesting innovation for matching balanced constructs (historically, something not possible with a regular expression). It’s not particularly easy to understand—this section is short, but be warned, it is very dense.

It’s easiest to understand with an example, so I’ll start with one:

Dim R As Regex = New Regex(" \( " & _

" (?> " & _

" [^()]+ " & _

" | " & _

" \( (?< DEPTH> ) " & _

" | " & _

" \) (?< -DEPTH> ) " & _

" )* " & _

" (?(DEPTH)(?!)) " & _

" \) ", _

RegexOptions.IgnorePatternWhitespace)

This matches the first properly-paired nested set of parentheses, such as the underlined portion of 'before (nope

after'. The first parenthesis isn’t matched because it has no associated closing parenthesis.

Here’s the super-short overview of how it works:

- With each ‘(’ matched, ⌈

(?<DEPTH>)⌋ adds one to the regex’s idea of how deep the parentheses are currently nested (at least, nested beyond the initial ⌈\(⌋ at the start of the regex). - With each ‘)’ matched, ⌈

(?<-DEPTH>)subtracts one from that depth. - ⌈

(?(DEPTH)(?!))⌋ ensures that the depth is zero before allowing the final literal ⌈\)to match.

This works because the engine’s backtracking stack keeps track of successfully-matched groupings. ⌈(?<DEPTH>)⌋ is just a named-capture version of ⌈()⌋, which is always successful. Since it has been placed immediately after ⌈\ (⌋, its success (which remains on the stack until removed) is used as a marker for counting opening parentheses.

Thus, the number of successful 'DEPTH' groupings matched so far is maintained on the backtracking stack. We want to subtract from that whenever a closing parentheses is found. That’s accomplished by .NET’s special ⌈(?<-DEPTH>) construct, which removes the most recent “successful DEPTH” notation from the stack. If it turns out that there aren’t any, the ⌈(?<-DEPTH>)⌋ itself fails, thereby disallowing the regex from over-matching an extra closing parenthesis.

Finally, ⌈(?(DEPTH)(?!))⌋ is a normal conditional that applies ⌈(?!)⌋ if the 'DEPTH' grouping is currently successful. If it’s still successful by the time we get here, there was an unpaired opening parenthesis whose success had never been subtracted by a balancing ⌈(?<-DEPTH>)⌋. If that’s the case, we want to exit the match (we don’t want to match an unbalanced sequence), so we apply ⌈(?!)⌋, which is normal negative lookahead of an empty subexpression, and guaranteed to fail.

Phew! That’s how to match nested constructs with .NET regular expressions.

Capture Objects

There’s an additional component to .NET’s object model, the Capture object, which I haven’t discussed yet. Depending on your point of view, it either adds an interesting new dimension to the match results, or adds confusion and bloat.

A Capture object is almost identical to a Group object in that it represents the text matched within a set of capturing parentheses. Like the Group object, it has methods for Value (the text matched), Length (the length of the text matched), and Index (the zero-based number of characters into the target string that the match was found).

The main difference between a Group object and a Capture object is that each Group object contains a collection of Captures representing all the intermediary matches by the group during the match, as well as the final text matched by the group.

Here’s an example with ⌈^(..)+⌋ applied to 'abcdefghijk':

Dim M as Match = Regex.Match("abcdefghijk", "^(..)+")

The regex matches four sets of ⌈(..)⌋, which is most of the string:  . Since the plus is outside of the parentheses, they recapture with each iteration of the plus, and are left with only

. Since the plus is outside of the parentheses, they recapture with each iteration of the plus, and are left with only 'ij' (that is, M.Groups(1).Value is 'ij'). However, that M.Groups(1) also contains a collection of Captures representing the complete 'ab', 'cd', 'ef', 'gh', and 'ij' that ⌈(..)⌋ walked through during the match:

M.Groups(1).Captures(0).Value is 'ab'

M.Groups(1).Captures(1).Value is 'cd'

M.Groups(1).Captures(2).Value is 'ef'

M.Groups(1).Captures(3).Value is 'gh'

M.Groups(1).Captures(4).Value is 'ij'

M.Groups(1).Captures.Count is 5.

You’ll notice that the last capture has the same 'ij' value as the overall match, M.Groups (1) .Value. It turns out that the Value of a Group is really just a shorthand notation for the group’s final capture. M.Groups(1).Value is really:

M.Groups(1).Captures( M.Groups(1).Captures.Count - 1 ).Value

Here are some additional points about captures:

M.Groups(1).Capturesis aCaptureCollection, which, like any collection, hasItemsandCountproperties. However, it’s common to forego theItemsproperty and index directly through the collection to its individual items, as withM.Groups(1) .Captures(3) (M.Groups[1].Captures[3]in C#).- A

Captureobject does not have aSuccessmethod; check theGroup'sSuccessinstead. - So far, we’ve seen that

Captureobjects are available from aGroupobject. Although it’s not particularly useful, aMatchobject also has aCapturesproperty.M.Capturesgives direct access to theCapturesproperty of the zeroth group (that is,M.Capturesis the same asM.Groups(0).Captures). Since the zeroth group represents the entire match, there are no iterations of it “walking through” a match, so the zeroth captured collection always has only oneCapture.Since they contain exactly the same information as the zerothGroup, bothM.CapturesandM.Groups(0).Capturesare not particularly useful.

.NET’s Capture object is an interesting innovation that appears somewhat more complex and confusing than it really is by the way it’s been “overly integrated” into the object model. After getting past the .NET documentation and actually understanding what these objects add, I’ve got mixed feelings about them. On one hand, it’s an interesting innovation that I’d like to get to know. Uses for it don’t immediately jump to mind, but that’s likely because I’ve not had the same years of experience with it as I have with traditional regex features.

On the other hand, the construction of all these extra capture groups during a match, and then their encapsulation into objects after the match, seems an efficiency burden that I wouldn’t want to pay unless I’d requested the extra information. The extra Capture groups won’t be used in the vast majority of matches, but as it is, all Group and Capture objects (and their associated GroupCollection and CaptureCollection objects) are built when the Match object is built. So, you’ve got them whether you need them or not; if you can find a use for the Capture objects, by all means, use them.