Email and the Internet

Unlike most proprietary email solutions, where a single software package does everything, Internet email is built from several standards and protocols that define how messages are composed and transferred from a sender to a recipient. There are many different pieces of software involved, each one handling a different step in message delivery. Postfix handles only a portion of the whole process. Most email users are only familiar with the software they use for reading and composing messages, known as a mail user agent (MUA). Examples of some common MUAs include mutt, elm, Pine, Netscape Communicator, and Outlook Express. MUAs are good for reading and composing email messages, but they don’t do much for mail delivery. That’s where Postfix fits in.

Email Components

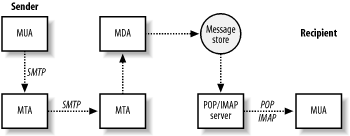

When you tell your MUA to send a message, it simply hands off the message to a mail server running a mail transfer agent (MTA). Figure 1-1 shows the components involved in a simple email transmission from sender to recipient. MTAs (like Postfix) do the bulk of the work in getting a message delivered from one system to another. When it receives a request to accept an email message, the MTA determines if it should take the message or not. An MTA generally accepts messages for its own local users; for other systems it knows how to forward to; or for messages from users, systems, or networks that are allowed to relay mail to other destinations. Once the MTA accepts a message, it has to decide what to do with it next. It might deliver the message to a user on its system, or it might have to pass the message along to another MTA. Messages bound for other networks will likely pass through many systems. If the MTA cannot deliver the message or pass it along, it bounces the message back to the original sender or notifies a system administrator. MTA servers are usually managed by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) for individuals or by corporate Information Systems departments for company employees.

Ultimately, a message arrives at the MTA that is the final destination. If the message is destined for a user on the system, the MTA passes it to a message delivery agent (MDA) for the final delivery. The MDA might store the message as a plain file or pass it along to a specialized database for email. The term message store applies to persistent message storage regardless of how or where it is kept.

Once the message has been placed in the message store, it stays there until the intended recipient is ready to pick it up. The recipient uses an MUA to retrieve the message and read it. The MUA contacts the server that provides access to the message store. This server is separate from the MTA that delivered the message and is designed specifically to provide access for retrieving messages. After the server successfully authenticates the requester, it can transfer that user’s messages to her MUA.

Because Internet email standards are open, there are many different software packages available to handle Internet email. Different packages that implement the same protocols can interoperate regardless of who wrote them or the type of system they are running on. If you are putting together a complete email system, most likely the software that handles SMTP will be a different package than the software that handles POP/IMAP, and there are many different software choices for each aspect of your complete email system.

Major Email Protocols

The communications that occur between each of these email system components are defined by standards and protocols. The standards documents are maintained by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and are published as Request For Comments (RFC) documents, which are numbered documents that explain a particular technology or protocol.

The Simple Mail Transport Protocol (SMTP) is used for sending messages, and either the Post Office Protocol ( POP) or Internet Mail Application Protocol ( IMAP) is used for retrieving messages. SMTP, defined in RFC 2821, describes the conversation that takes place between two hosts across a network to exchange email messages. The IMAP (RFC 2060) and POP (RFC 1939) protocols describe how to retrieve messages from a message store. The IMAP protocol was developed after POP and offers additional features. In both protocols, email messages are kept on a central server for message recipients who generally retrieve them across a network.

Note that the MUA does not necessarily use the same system for POP/IMAP as it does for SMTP, which is why email clients have to be configured separately for POP/IMAP and SMTP. An ISP might provide separate servers for each function to their customers, and corporate users who are away from the office often retrieve their messages from the company POP/IMAP server, but use the SMTP server of a dial-up ISP to send messages. MTA software running on SMTP servers constantly listens for requests to accept messages for delivery. Requests might come from MUAs or other MTA servers.

SMTP and email submission

SMTP is commonly used for email submission and for transmissions of email messages between MTAs. When an MUA contacts an MTA to have a message delivered, it uses SMTP. SMTP is also used when one MTA contacts another MTA to relay or deliver a message. Originally, SMTP had no means to authenticate users, but extensions to the protocol provide the capability, if required. See Chapter 7 for more information on authenticating SMTP users.

POP/IMAP and mailbox access

When users want to retrieve their messages, they use their MUA to connect to a POP or IMAP server to retrieve them. POP users generally take all their messages from the server and manage their mail locally. IMAP provides features that make it easier to manage mail on the server itself. (See Chapter 12 for more information on using Postfix with POP and IMAP servers.) Many servers now offer both protocols, so I will refer to them as POP/IMAP servers. POP and IMAP have nothing to do with sending email. These protocols deal only with how users retrieve previously delivered and stored messages.

Not all users need POP/IMAP access to the message store. Users with shell access on a Unix machine, for example, might have their MUA configured to read their email messages directly from the mail file that resides on the same machine.