Understanding the essentials of dealing with packed and encrypted malware is paramount when dealing with real world malware. In tandem, you should also be able to follow malware activity as it goes to and fro between the user mode and the kernel mode, or tries nifty tricks to be as stealthy or destructive as it can be. In this chapter, you will learn the following:

- The process of unpacking packed binaries

- Kernel mode debugging with IDA Pro, Virtual KD, and VMWare

- Windows internals concepts

The current populous malwares are mostly obfuscated, packed, or encrypted to thwart detection and impede reverse engineering, usually as way to buy more time so that analysis will be made redundant if the malware has achieved its goals. However, while packed/encrypted malwares have telltale signs, such as high entropy or PE format anomalies, obfuscation can be trickier to detect in the first place – undocumented function calls, singular call gates, environment aware malware, and ingenious methods to bypass both static and automated dynamic analysis, among various other techniques, are very much in vogue. Some foundational unpacking skills are certainly a necessity that every malware analyst must be well acquainted with.

Packers such as Ultimate Packer for Executables (UPX) are more of executable compressors as size reduction is the primary goal, not obfuscation, which can be a byproduct of customizing the open source code to create altered variants. Think of a packer as a bag where you tightly pack a pliable executable. After packing, all you get to see is the bag and its properties, not the executable. However, the executable is still intact. Minor obfuscation is a side effect of any kind of compression algorithm. For UPX using the -d <UPX_packed_file> switch is all you need to get the original executable. However, for other packers and even a UPX manipulated file, such simple measures will not be enough; headers can be corrupted even as the packed executable runs properly, multi-layered encryption can be employed, process memory can be spliced, and imports can be destroyed and fragmented in the memory. The other variant or approach is a complete virtual machine or a bytecode interpreter that can run an intermediate language that further translates to the native instructions of the original executable. The majority of simple to intermediate packers mainly deal with an unpacking stub in which the entire executable is rebuilt from scratch with no semblance to the original binary. This file image, when run, will reconstruct the code sections and the imports, and transfer the control flow to the OEP, normally done by an unpacking stub so that the memory image works flawlessly.

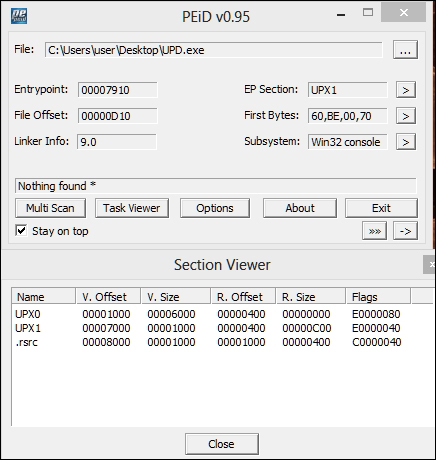

Some of the tell-tale signs of a packed file are a reduced number of sections, section raw sizes with a zero value but a discrepancy of virtual size > 0 indicating a container for the unpacked code in memory, multiple section characteristics with executable settings, high entropy (discussed in Chapter 1, Down the Rabbit Hole) in particular sections, high entropy overlays, strange names or that of expected packers, spaghetti code, very few imports and only the ones used for dynamic linking in Windows normally versions of LoadLibrary().

HMODULE WINAPI LoadLibrary( _In_ LPCTSTR lpFileName ); HMODULE WINAPI LoadLibraryEx( _In_ LPCTSTR lpFileName, _Reserved_ HANDLE hFile, _In_ DWORD dwFlags );

And GetProcAddress

FARPROC WINAPI GetProcAddress( _In_ HMODULE hModule, _In_ LPCSTR lpProcName );

These occur in sequential pairs or ShellExecute.

HINSTANCE ShellExecute( _In_opt_ HWND hwnd, _In_opt_ LPCTSTR lpOperation, _In_ LPCTSTR lpFile, _In_opt_ LPCTSTR lpParameters, _In_opt_ LPCTSTR lpDirectory, _In_ INT nShowCmd );

Or WinExec

UINT WINAPI WinExec( _In_ LPCSTR lpCmdLine, _In_ UINT uCmdShow );

And msvcrt system command among a few.

Cracker tools and debuggers can be used to both identify and unpack them. PEiD and ExeInfo are great for detecting a vast majority of packers. Import Reconstructor, commonly known ImpRec, is a tool developed for rebuilding import tables from process memory of a packed executable. You have to use a debugger such as OllyDbg to get the memory dump and save it to a file image, after which ImpRec will rebuild the imports and add a new section to get the binary running. For memory dumping, the OllyDump plugin is very well recommended. The logic is to run the malware or the packed binary till it reaches its OEP, after which the imports are recalculated based on the in memory code pages and their import references rebuilt by the unpacking stub. Thereafter, a select number of executable memory pages are written to disk and the PE headers are adapted to re-accommodate the built file. The other approach is to reverse the packing algorithm if it can be done by study of its algorithm, which can mean writing an unpacker from scratch. This approach can be undertaken by using APIs such as TitanEngine (Reversing Labs) for extensive PE manipulation (PackerBreaker is a freeware that also claims to work with a lot of packers). Most of the time you will have to figure out the OEP yourself, though a number of techniques such as section hop detection (the OllyBone plugin) are available to automate some parts of the process. Unfortunately, this is an AI intensive job that humans do a lot better than any tool currently, though the process can be labor intensive. You can script a debugger to break at the OEP and then further add to the script to dump the sections in memory and automatically run the imports gathering algorithm, which can then save the final unpacked binary.

A certain number of patterns emerge after looking at various packers. For instance, in UPX you have something called a tail jump where the OEP is referenced in an ending jmp <hardcoded> instruction after the unpakcing stub has run its course. With other packers, jmp eax is more prevalent. UPX also starts with PUSHAD and ends with POPAD sequence, which are some of the more commonly used assembly instructions to save the registers on the stack and restore them. Setting breakpoints at specific APIs like the GetProcAddress in order to find the exported API function or variables addresses. Enabling breakpoints on commonly placed APIs such as:

GetCommandline:LPTSTR WINAPI GetCommandLine(void);

GetVersion:DWORD WINAPI GetVersion(void);

- Or

GetModuleHandle:HMODULE WINAPI GetModuleHandle( _In_opt_ LPCTSTR lpModuleName );

This can result in a successful detection of the OEP, as most commonly and regularly compiled code contains such boilerplates. Remember the points discussed in earlier chapters and things such as DLL Characteristics bit (0x2000) in PE headers for DLLs and function prologues and epilogues that should help you deal with and enable finding the OEP a lot easier. However, since we would be dealing with malware, do not be too surprised to see sequences such as Loadlibrary(svchost.exe), which is obviously suspicious in a general malware scenario, and in this particular malware sample svchost.exe was being prepped for process hollowing right after the decryption layers. Conditional breakpoints are very useful for trapping address range changes and classic techniques such as Run Trace in OllyDbg can be setup to break at the OEP by trial and error. Be prepared to deal with the various anti-debugging tricks embedded in the malware code while dealing with unpacking.

Windows virtual memory manager APIs VirtualAlloc (allocation of memory in a specified process, region is set to zero by default unless specified otherwise).

LPVOID WINAPI VirtualAlloc( _In_opt_ LPVOID lpAddress, _In_ SIZE_T dwSize, _In_ DWORD flAllocationType, _In_ DWORD flProtect );

VirtualAllocEx (allocation of memory in another process)

LPVOID WINAPI VirtualAllocEx( _In_ HANDLE hProcess, _In_opt_ LPVOID lpAddress, _In_ SIZE_T dwSize, _In_ DWORD flAllocationType, _In_ DWORD flProtect );

VirtualProtect (to specify the memory page protection level for the calling process)

BOOL WINAPI VirtualProtect( _In_ LPVOID lpAddress, _In_ SIZE_T dwSize, _In_ DWORD flNewProtect, _Out_ PDWORD lpflOldProtect );

VirtualProtectEx (to specify the memory page protection level in any process)

BOOL WINAPI VirtualProtectEx( _In_ HANDLE hProcess, _In_ LPVOID lpAddress, _In_ SIZE_T dwSize, _In_ DWORD flNewProtect, _Out_ PDWORD lpflOldProtect );

And VirtualFree (frees the allocated memory)

BOOL WINAPI VirtualFree( _In_ LPVOID lpAddress, _In_ SIZE_T dwSize, _In_ DWORD dwFreeType );

These are especially important in terms of memory packing and unpacking as a host of malicious processes are enabled using these APIs (in addition to ancillary API's such as WriteProcessMemory, ReadProcessMemory, CreateRemoteThread, and other well documented API pattern constituents that are usually found in malware) from code injection to process injection and process hollowing, polymorphism as well as a bevy of malware packing algorithms make use of this family. Of course, you still have to be on the lookout for alternate APIs and undocumented native interfaces that can be used as they get discovered. Keep a sharp eye on malware code that makes use of the aforementioned.

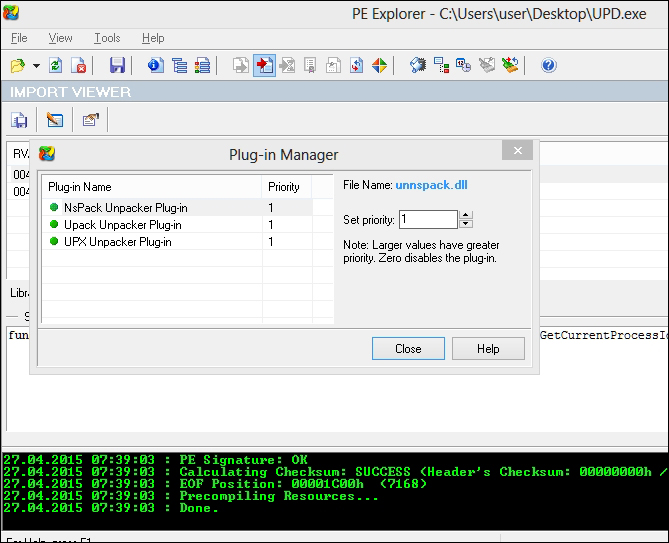

PE Explorer deserves a special mention as it automatically unpacks three of the most common packers and its plugin framework can be leveraged for writing the unpackers. You simply drag and drop the binary and start analyzing the sample unpacked right at the outset. Nice!

Let us look at manual UPX unpacking as an example:

- Write the following code in VC++:

#include "stdafx.h" #include <conio.h> int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[]) { printf("Hello World UPX!"); getchar(); return 0} - Name the file as

HelloWorldUPX.exe. - Download UPX from http://upx.sourceforge.net/#downloadupx.

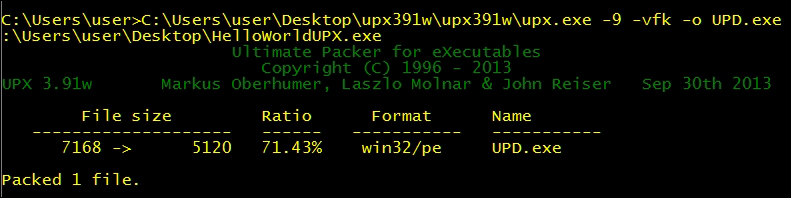

- Unzip UPX and run with the following options, given UPX and the original binary are in the same directory:

Upx.exe -9 -vfk -o UPD.exe HelloWorldUPX.exe

- Run the UPX'd version to check if it works. Now we can start the unpacking process.

The

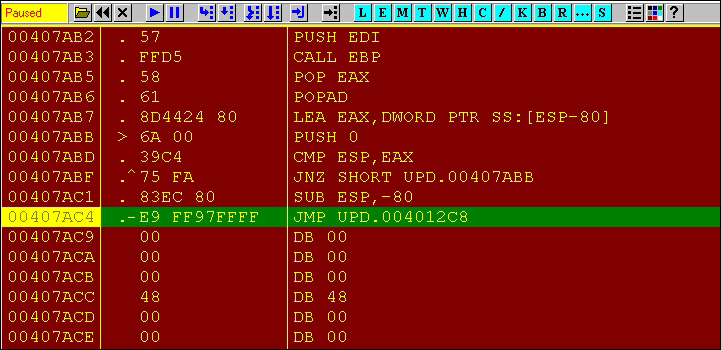

-9enables best compression and while the section names and the imports are reconstructed, PEiD does not detectupx.exeas such. - Open the binary in OllyDbg and set a breakpoint at the following location (scroll down from the entry point to reach):

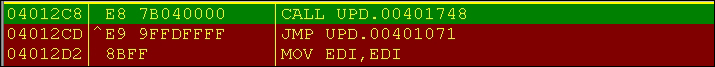

- Next, press F7 to step in to the OEP.

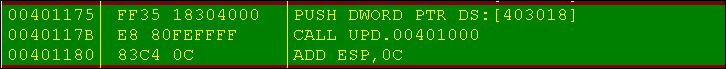

- To get to the

Hello World UPX!string, move to the top of the disassembly at 0x401000 or step in by putting a breakpoint at the same.

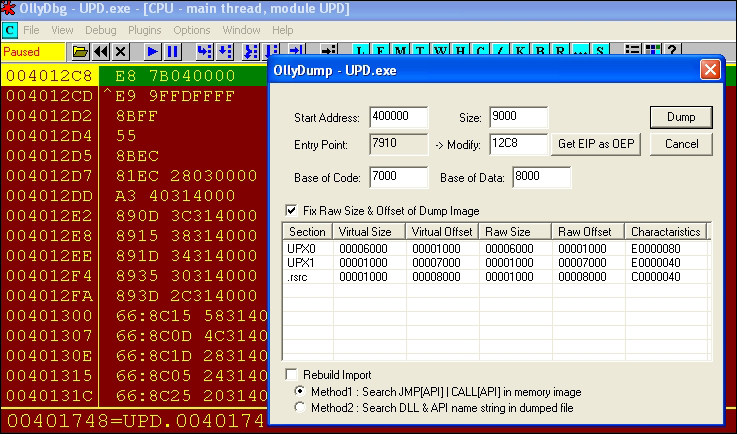

- Restart OllyDbg and break at the OEP; run OllyDump with the following settings:

- Save the file to the disk named

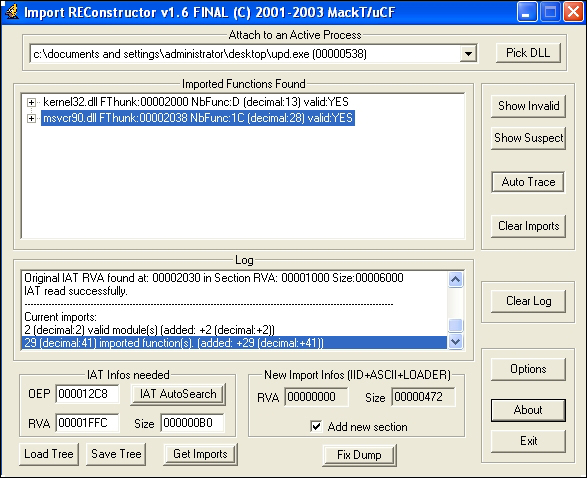

DUMP.exe. Then openImpRecand set the OEP value in the box to your lower left to the OEP RVA (not VA, that is sans ImageBase or else the tool will complain that the address is not in range of the process memory). Press IAT AutoSearch and you should see the imported functions found successfully. Thereafter, press the Fix Dump button and choose the earlierDUMP.exe. You should have a fully dumped and rebuilt binary with a new imports table with the nameDUMP_(notice the extra underscore in the name). Run it and see if it works.

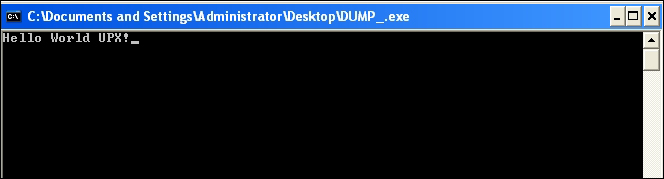

Yes it does!

There will be scenarios and extremely complex packed malware that may employ modern protection mechanisms and packers such as Themida and VMProtect or more lately even Codemeter (still unbroken) might be in utility sooner than we expect. This, logistically speaking will take a lot of time than you have on your hands to fully unpack it byte for byte (analyses and not cracking based work) - given such a situation, do enough to facilitate analyses and focus on the bigger picture. As long as you can get the details out of the malware binary in whatever manner possible, do not get bogged down by such impediments as there will be a point of diminishing returns, wherein no further value will be added to your analyses regardless of how well you reverse the packing algorithm, unless of course you are researching to write a custom unpacker, which would be a very cool thing to do indeed!