Beyond the fundamentals of computing including number systems and Boolean operators, most computer programs make use of constructs that enable us to convey logic in source code and build algorithms that work with and on data structures. This section explains the most essential language constructs in C that should set the tone for how the rest of the book progresses. When analyzing malware, much of your time will be spent in front of the disassembler and debugger, and reading as well as writing assembly code will be a routine activity. The commonly used code constructs for native binary-compiled languages once written to source code are digested by the compiler and linker to produce the final binary executable. To what end the code constructs are compiled is a natural point of interest for the analyst. Since most of the time, the source code of the malware binary is not available, it is mandatory that recognizing code constructs in assembly be practiced to a good level of understanding.

Let us look at some code constructs and how they look inside the binary when disassembled. A lot of startup boilerplate code is inserted into the final binary, and hence, our focus for now is on the code lines of interest. Various security mechanism options and optimizations result in quirky looking assembly code of relatively simple source code. This will not be a primer on native languages such as C nor an in-depth introduction to assembly language, but a warm-up session for the rest of the book. You are recommended to learn C programming if you do not already know it. We will discuss the nuts and bolts of assembly programming essentials and deciphering high-level language constructs from assembly text in the chapters ahead, so do not fret if you do not get this at this stage. You can always revisit this section later on and solidify your understanding as you progress with this book. You will focus on conditional constructs and data structures such as structs and linked lists. Let's see some C/C++ in action in Visual Studio 2008 and IDA Pro 6.1.

#include "stdafx.h"

#include<conio.h>

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

for (int i=0; i<10 ; i++) {

printf("%d\n",i);

}

getche();

return 0;

}Some disassembly excerpts from IDA Pro are as follows:

mov edi,ds:__imp__printf ; store address of printf to edi from imports xor esi, esi ;set value of int i=0 using esi register LOOP_START: push esi ;push the value of esi to the stack push offset Format ;push the format string for printf call edi:__imp_printf ; call to printf via import table address at edi inc esi ; increment counter variable at esi by one add esp,8 ; restore the call stack (clear 2 parameters pushed) cmp esi, 0Ah ;if esi < 10 then jump to start of loop label jl LOOP_START

Let us look at the while loop:

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

int i=0;

while (true){

printf("%d\n",i);

if (i>=10) {

break;

}

else {

++i;

}

}

getche();

return 0;

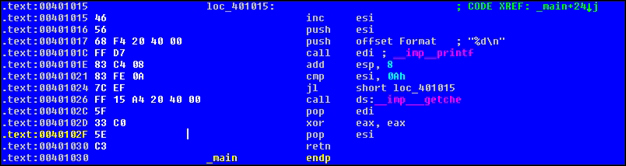

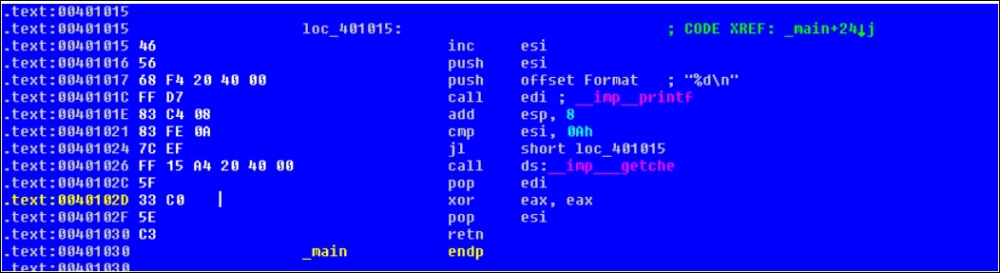

}This how an IDA Pro listing can look:

The while loop assembly code is eerily similar to that of the for loop; notice how the return 0 code line is compiled as xor eax, eax. The return values of all function calls normally end up in the eax register.

Now, let's look at the do-while loop:

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

int i=0;

do{

printf("%d\n",i);

if (i>=10){

break;

}

else{

++i;

}

}while(true);

getche();

return 0;

}

Notice how jl short loc_401015 implies that for the instruction cmp esi, 0Ah, if the value of esi is less than 10 decimal, then redirect the control to the instruction at address 0x401015, which is inc esi, or increment the value in the esi register. Thereafter, the value is pushed to the stack as the second parameter and the format string to printf as the first parameter, and printf is called. The stack is restored as a __cdecl call convention as well; note that the 8h bytes or 8h/4h = 2 parameter spaces are being cleared off the stack. The process repeats till esi is greater than or equal to 10, after which getche() waits for user input, and then the program ends.

Next, let us look at the if-then-else loop:

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

int i=0;

if (i!=2) {i=2;}

start:

if (i==2) {

printf("%d is true \n",i);

i=9;

}else if (i==10) {

printf("%d is true \n",i);

}else if (i==11) {

printf("%d is true \n",i);

getche();}

++i;

goto start;

getche();

return 0;

}

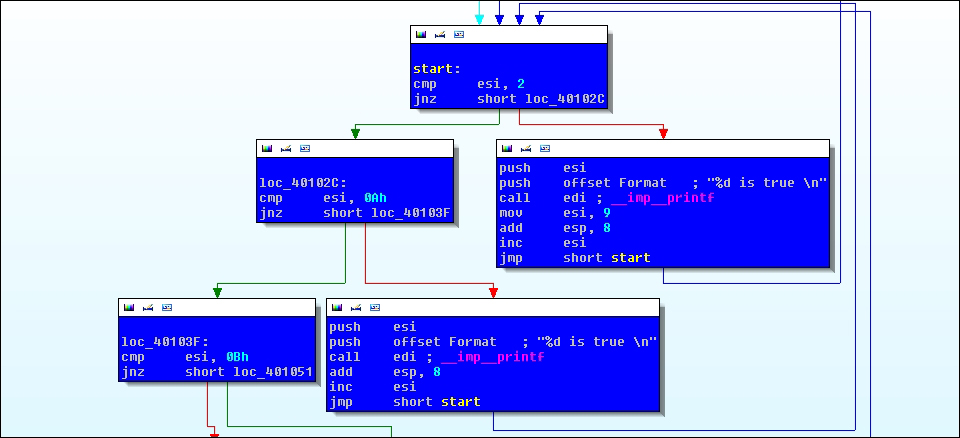

From the preceding exhibit, the cmp esi,2 instruction is evaluated as the zero flag is set or not and jnz will evaluate to true if the zero flag is not set or esi !=2 and proceeds to the left-side graph node to check whether the value of esi compares with 0Ah or 10 decimal. If esi == 2 from the start: label, then the string "2 is true" is printed. If esi != 10 decimal, then it proceeds to check whether esi is equal to 11 decimal or 0xB. If true, getche() waits for user input (the Enter key). Notice the inc esi instruction in most of the blocks that coincide with the ++i source code line. This will eventually overflow the data range, the value of esi will return to 2, and the loop will start again. Variable i is declared as a signed int (implicitly), meaning that there will be a negative sequence of numbers as well. You can verify this in the debugger via the Edit-and-Continue feature in VC++ by changing the counter value to 0x80000000 (-2^31) to 0xFFFFFFFE (-2) and using printf() to see the signed numbers in the stdout console. This continues over and over again, and you can exit by pressing Ctrl + C in the console.

Let us have a look at a switch case:

int i=0;

switch (i){

case 1: printf ("1\n");break;

case 2: printf ("2\n"); break;

default : printf("default case\n");With compiler optimization enabled for small code (/Os in VC++), the code is relatively short and the data flow and conditionals are precomputed by the compiler.

Tip

For more information on this, have a look at this link https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/k1ack8f1(v=vs.90).aspx.

.text:00401000 ; int __cdecl main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp) .text:00401000 _main proc near ; CODE XREF: __tmainCRTStartup+10Ap .text:00401000 .text:00401000 argc = dword ptr 4 .text:00401000 argv = dword ptr 8 .text:00401000 envp = dword ptr 0Ch .text:00401000 .text:00401000 push offset Format ; "default case\n" .text:00401005 call ds:__imp__printf .text:0040100B add esp, 4 .text:0040100E call ds:__imp___getche .text:00401014 xor eax, eax .text:00401016 retn

The code is quite compact as the compiler has precalculated the value of i as 0, and hence, the default case is the only case required, with the other two cases omitted. The full disassembly text is taken from IDA Pro, which is something you will have to get used to even as we deal with excerpts for now. The various items that you get to read in one line from the left are as follows: the section name of the current code (referring to the PE file), the virtual memory address of the process of the current set of opcodes, the opcodes represented as a hex sequence in the little-endian format, various labels inserted by IDA Pro such as variable names and their stack offsets, as well as the function names and symbol data, and the disassembly text. During malware analysis sessions of x86 binaries, disassembly is pretty much the main interface that you have to work with.

Now, consider the compiler optimization disabled:

.text:00401000 ; int __cdecl main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp) .text:00401000 _main proc near ; CODE XREF: __tmainCRTStartup+10Ap .text:00401000 .text:00401000 var_8 = dword ptr -8 .text:00401000 i = dword ptr -4 .text:00401000 argc = dword ptr 8 .text:00401000 argv = dword ptr 0Ch .text:00401000 envp = dword ptr 10h .text:00401000 .text:00401000 push ebp .text:00401001 mov ebp, esp .text:00401003 sub esp, 8 .text:00401006 mov [ebp+i], 0 .text:0040100D mov eax, [ebp+i] .text:00401010 mov [ebp+var_8], eax .text:00401013 cmp [ebp+var_8], 1 .text:00401017 jz short loc_401021 .text:00401019 cmp [ebp+var_8], 2 .text:0040101D jz short loc_401031 .text:0040101F jmp short loc_401041 .text:00401021 ; --------------------------------------------------------------------------- .text:00401021 .text:00401021 loc_401021: ; CODE XREF: _main+17j .text:00401021 push offset Format ; "1\n" .text:00401026 call ds:__imp__printf .text:0040102C add esp, 4 .text:0040102F jmp short loc_40104F .text:00401031 ; --------------------------------------------------------------------------- .text:00401031 .text:00401031 loc_401031: ; CODE XREF: _main+1Dj .text:00401031 push offset a2 ; "2\n" .text:00401036 call ds:__imp__printf .text:0040103C add esp, 4 .text:0040103F jmp short loc_40104F .text:00401041 ; --------------------------------------------------------------------------- .text:00401041 .text:00401041 loc_401041: ; CODE XREF: _main+1Fj .text:00401041 push offset aDefaultCase ; "default case\n" .text:00401046 call ds:__imp__printf .text:0040104C add esp, 4 .text:0040104F .text:0040104F loc_40104F: ; CODE XREF: _main+2Fj

Follow the pushed parameter strings to printf and try to reconstruct the switch case segments from the preceding disassembly:

mov [ebp+i], 0 mov eax, [ebp+i] mov [ebp+var_8], eax cmp [ebp+var_8], 1

The preceding code sequence has the value 0 moved to variable i in the stack. From the variable offsets at the start of the function, you see that i is located at a negative offset from the base pointer of the current stack frame, which means that it is a local variable. Hence, [ebp+i] is also [ebp-4], and the brackets dereference the address with 0 that is stored here. This value is then copied to eax and moved to the next offset for comparisons on the stack at ebp-8, which is then compared to 1 and then 2.

#include "stdafx.h"

#include <conio.h> //requisite VC++ and C standard library

//headers

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct _sequence { //defining the struct

char * seqname;

unsigned int range;

unsigned int fib []; //uninitialized array;

}Seq;

Seq *ptrSeq; //declaring a pointer variable

/* the Fibonacci sequence function with declared pointer variable

as argument */

void fibonacciNumbers(Seq* ptrSeq){

(*ptrSeq).fib[0]=0;

(*ptrSeq).fib[1]=1;

printf("%d \n",(*ptrSeq).fib[0]);

printf("%d \n",(*ptrSeq).fib[1]);

for (int i=2; i<ptrSeq->range;i++) {

ptrSeq->fib[i]=(ptrSeq->fib[i-1]+ptrSeq->fib[i-2]);

printf("%d \n",(*ptrSeq).fib[i]);

}

printf("%s \n",ptrSeq->seqname);

}

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

ptrSeq=(Seq*)malloc(sizeof(Seq));

ptrSeq->range=15; //user can set this to any value

ptrSeq->seqname=(char*)malloc(strlen("Fibonacci")+1);

strcpy(ptrSeq->seqname,"Fibonacci");

fibonacciNumbers(ptrSeq); //call to Fibonacci function

getchar();

return 0;

}If you load the debug build in IDA Pro, you have all the symbols needed for the file, which can greatly help in any debugging scenario. Symbols are in a proprietary database format, *.pdb, for the program database, which essentially contains name and address pairs to help the debugger translate constructs such as function names and variable names, and other data structures such as classes. You may need to demangle them by using the Options | Demangled Names menu and choose Names to get a cleaner set of names in place. Name mangling is a compiler-specific method to implement features such as polymorphism and inheritance in object-oriented C++ code, so that the function name remains the same even if the signatures are changed.

The disassembly of the Fibonacci function:

.text:013F365E mov eax, [ebp+ptrSeq] .text:013F3661 mov dword ptr [eax+8], 0 .text:013F3668 mov eax, [ebp+ptrSeq] .text:013F366B mov dword ptr [eax+0Ch], 1 .text:013F3672 mov esi, esp

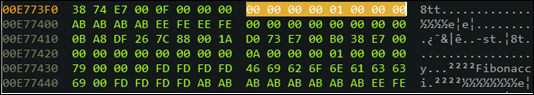

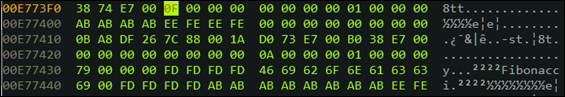

Here, we see the base address of the structure loaded to eax. You can examine the memory in the IDA Hex view and look at the values of 0 and 1 stored at offset 8h and Ch from the base. You can also see the zero-terminated string for "Fibonacci" that is at address E77438h. Is not the offset stored at the beginning of the structure in the little endian order of 38h 74h E7h?

.text:013F36AE mov [ebp+i], 2

For the preceding instruction, you can see the start value of the loop value dereferenced at [ebp+i] set to 2:

.text:013F36C0 mov eax, [ebp+ptrSeq] .text:013F36C3 mov ecx, [ebp+i] .text:013F36C6 cmp ecx, [eax+4]

The final count for the loop is 0xF, referenced by [eax+4] or 15 decimals, which you can see in the following memory view. At this point, the compare instruction compares between ecx, which has the value of 2 and the value at [eax+4], which has the value of 15.

.text:013F36CB mov eax, [ebp+i] .text:013F36CE mov ecx, [ebp+ptrSeq] .text:013F36D1 mov edx, [ecx+eax*4+4]

Here, the counter from the loop variable is stored at eax.

The base of the structure is stored at ecx.

[ecx+eax*4+4] refers to the deferenced value at the Base + Index * Scale + Displacement of the structure.

Integers have a size of 4 for this program environment and hence, are the scale factor to the counter variable used as an index to the fib[] array in the source code. The displacement is an added offset that refers to the next element from the current index. This would be fib[i-1]. [ecx+eax*4] would then be fib[i-2]. Remember that the count subtracted or added to an array element moves by the size of the data type, hence, the difference of 4:

.text:013F36CB mov eax, [ebp+i] .text:013F36CE mov ecx, [ebp+ptrSeq] .text:013F36D1 mov edx, [ecx+eax*4+4] ; fib[i-1] .text:013F36D5 mov eax, [ebp+i] .text:013F36D8 mov ecx, [ebp+ptrSeq] .text:013F36DB add edx, [ecx+eax*4] ; +fib[i-1]+fib[i-2] .text:013F36DE mov eax, [ebp+i] .text:013F36E1 mov ecx, [ebp+ptrSeq] .text:013F36E4 mov [ecx+eax*4+8], edx

Here, [ecx+eax*4+8] denotes the current element in the array as per the current index, which is fib[i]. This has to be a linear arrangement and hence, is right after fib[i-1] and hence the 8 as displacement:

.text:013F36E8 mov esi, esp ; storing stack pointer for integrity check

.text:013F36EA mov eax, [ebp+i] ; store current index again to eax

.text:013F36ED mov ecx, [ebp+ptrSeq] ; store the base address of ptrSeq

.text:013F36F0 mov edx, [ecx+eax*4+8] ;store fib[i] to edx

.text:013F36F4 push edx

.text:013F36F5 push offset Format ; "%d \n"

.text:013F36FA call ds:__imp__printf ;print out the value

.text:013F3700 add esp, 8 ; destroy the stack frame

.text:013F3703 cmp esi, esp ;check stack integrity

.text:013F3705 call j___RTC_CheckEsp

.text:013F370A jmp short loc_13F36B7

.text:013F36B7 loc_13F36B7: ; CODE XREF: fibonacciNumbers(_sequence *)+CAj

.text:013F36B7 mov eax, [ebp+i] ;load counter

.text:013F36BA add eax, 1 ;increment counter

.text:013F36BD mov [ebp+i], eax ; store back to the counter stack variable

;

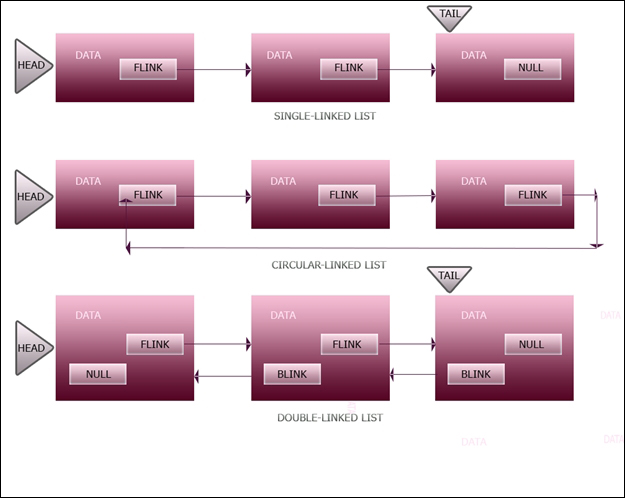

from here moving on to 013F36C0h at the top of the loop.Linked lists are an essential data structure used by the Windows OS internally to manage system data structures such as heaps. Linked lists are composed of nodes that store the data to be referenced and links (forward/backward pointers) that point to the address of the next or the previous node in the chain-like structure. There are three main types of linked lists given in the following exhibit—a single-linked list, circular-linked list, and double-linked list. The head and tail members implicitly point to the head and the tail, respectively.

Let us write a simple single-linked list as an example and understand how it functions behind the scenes. We will define some data structures and then write some methods to work on them:

#include "stdafx.h"

#include <conio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct _node {

void * data;

struct _node *next;

} Node;

typedef struct _linkedList {

Node *head;

Node *tail;

Node *current;

} LinkedList;

typedef struct _malwareinfo{

int sno;

char name[40];

char hash[70];

}MalwareInfo;

void resetLinkedList(LinkedList *list) {

list->head =NULL;

list->tail =NULL;

list ->current = NULL;

}

void appendToHead (LinkedList *list, void *info) {

Node *node=(Node *)malloc (sizeof(Node));

node->data =info;

if (list->head == NULL) {

list->tail =node;

node->next =NULL;

}else {

node->next = list->head;

}

list->head = node;

}

void renderInfo(MalwareInfo *mal){

printf("%d, %s, %s\n",mal->sno,mal->name,mal->hash);

}

void traverseList(LinkedList *list){

Node *seeker = list->head;

while(seeker!=NULL) {

renderInfo((MalwareInfo*)seeker->data);

seeker =seeker->next;

}}

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[])

{

LinkedList lister;

MalwareInfo *mal1=(MalwareInfo *)malloc (sizeof(MalwareInfo));

MalwareInfo *mal2=(MalwareInfo *)malloc (sizeof(MalwareInfo));

MalwareInfo *mal3=(MalwareInfo *)malloc (sizeof(MalwareInfo));

mal1->sno=1;

strcpy(mal1->name,"regin1");

strcpy(mal1->hash,"4d6cebe37861ace885aa00046e2769b500084cc79750d2bf8c1e290a1c42aaff");

mal2->sno=2;

strcpy(mal2->name,"regin2");

strcpy(mal2->hash,"4e39bc95e35323ab586d740725a1c8cbcde01fe453f7c4cac7cced9a26e42cc9");

mal3->sno=3;

strcpy(mal3->name,"regin3");

strcpy(mal3->hash,"5c81cf8262f9a8b0e100d2a220f7119e54edfc10c4fb906ab7848a015cd12d90");

resetLinkedList(&lister);

appendToHead(&lister,mal1);

appendToHead(&lister,mal2);

appendToHead(&lister,mal3);

traverseList(&lister);

getchar();

return 0;

}3, regin3, 5c81cf8262f9a8b0e100d2a220f7119e54edfc10c4fb906ab7848a015cd12d90 2, regin2, 4e39bc95e35323ab586d740725a1c8cbcde01fe453f7c4cac7cced9a26e42cc9 1, regin1, 4d6cebe37861ace885aa00046e2769b500084cc79750d2bf8c1e290a1c42aaff

Notice how the output is the reverse of the input sequence. In the preceding source code, we have described a struct for the Node and the LinkedList data structures. We have also defined a MalwareInfo struct to hold an example data structure to be inserted into the list. To initialize the linked list, we have a resetLinkedList function that basically sets all the linked list members to NULL or makes an empty list. The appendToHead function takes a list pointer and a void pointer to a data structure, which is used for casting any data type through the function. Here, a Node type is allocated in memory by using malloc, and the data member of the node is set to point to the address of the information parameter, which itself holds the address of the contents of the list data structure. If the list is empty, the list->tail member points to the node and node->next is set to NULL. If the list is not empty, then node->next points to list->head. Finally, list->head points to the node. Done this way, the linked list acts like a stack where list->head points to the last inserted node. Upon regular traversal from the start of the list in the traverseList function, which takes the list pointer to the structure, as a parameter uses the node->next member to find out the last node that points to NULL, you end up reading from the head, which is the last node inserted and hence, the data structure that it points to, thus giving a reverse data sequence output. Open the executable debug build in IDA Pro and navigate to the wmain function to enter the following instructions; note that the addresses might be different on your system:

var_F8= byte ptr -0F8h mal3= dword ptr -34h mal2= dword ptr -28h mal1= dword ptr -1Ch lister= _linkedList ptr -10h argc= dword ptr 8 argv= dword ptr 0Ch

IDA Pro analyzes the code and displays the offsets where the local variables and parameters are accessed in the disassembly, which helps in making the disassembly readable. Here, mal1, mal2, and mal3 are 12 (Ch) bytes apart in the stack.

.text:00413810 push 74h ; Size .text:00413812 call ds:__imp__malloc .text:00413818 add esp, 4

The size 74h or 116 decimals is the compiler-calculated byte-padded value for the struct size of MalwareInfo, which is 4 + 40 + 65 bytes. After the call to malloc, eax holds the address of the allocated region on the heap:

.text:00413822 mov [ebp+mal1], eax .text:00413825 mov eax, [ebp+mal1] .text:00413828 mov dword ptr [eax], 1

Preceding is the value of the first member of the mal1 structure, and the serial number abbreviated as sno is set to 1, as in the source code:

.text:0041382E push offset Source ; "regin1" .text:00413833 mov eax, [ebp+mal1] .text:00413836 add eax, 4

Since the size of an integer data type in a 32-bit x86 machine and in Windows is 4 bytes, 4 is added to the start of the structure offset at eax to store the "regin1" name string, which will take up upto 40 bytes of allocated character space. This is the destination address that acts as a parameter to strcpy:

.text:00413839 push eax ; Dest .text:0041383A call j__strcpy .text:0041383F add esp, 8 .text:00413842 push offset a4d6cebe37861ac ; "4d6cebe37861ace885aa00046e2769b500084cc"... .text:00413847 mov eax, [ebp+mal1] .text:0041384A add eax, 2Ch

2Ch or 44 is added to eax to move to the hash member storage area in the struct in the memory; this is calculated as the offset including the first and second members of the structure:

.text:0041384D push eax ; Dest .text:0041384E call j__strcpy .text:00413853 add esp, 8

You can see the layout in the memory in the Hex view by pressing G and typing the address of the malloc buffer in eax into the dialog box in IDA Pro:

007072B8 01 00 00 00 72 65 67 69 6E 31 00 CD CD CD CD CD ....regin1.----- 007072C8 CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD ---------------- 007072D8 CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD CD 34 64 36 63 ------------4d6c 007072E8 65 62 65 33 37 38 36 31 61 63 65 38 38 35 61 61 ebe37861ace885aa 007072F8 30 30 30 34 36 65 32 37 36 39 62 35 30 30 30 38 00046e2769b50008 00707308 34 63 63 37 39 37 35 30 64 32 62 66 38 63 31 65 4cc79750d2bf8c1e 00707318 32 39 30 61 31 63 34 32 61 61 66 66 00 CD CD CD 290a1c42aaff.--- 00707328 CD CD CD CD FD FD FD FD AB AB AB AB AB AB AB AB ----²²²²½½½½½½½½

The extra CDh bytes towards the end of the structure are the padding bytes.

The preceding sequence continues for the mal2 and mal3 data types:

.text:004138E6 lea eax, [ebp+lister] .text:004138E9 push eax ; list .text:004138EA call resetLinkedList(_linkedList *)

EAX is then set to lister and is passed to the resetLinkedList function. Entering this function, we find that the main lines of interest are as follows:

.text:012813FE mov eax, [ebp+list] .text:01281401 mov dword ptr [eax], 0 .text:01281407 mov eax, [ebp+list] .text:0128140A mov dword ptr [eax+4], 0 .text:01281411 mov eax, [ebp+list] .text:01281414 mov dword ptr [eax+8],0

The members of the list structure are 4 bytes apart (pointer data type), and the offset is calculated from the base of the structure and is set to 0 (NULL):

.text:004138F2 mov eax, [ebp+mal1] .text:004138F5 push eax ; data .text:004138F6 lea ecx, [ebp+lister] .text:004138F9 push ecx ; list .text:004138FA call appendToHead(_linkedList *,void *) .text:004138FF add esp, 8

Now, enter appendToHead:

.text:01281460 push 8 ; Size .text:01281462 call ds:__imp__malloc

The Node instance is created with the malloc parameter value of 8 as there are two pointer types in Node:

.text:01281472 mov [ebp+node], eax .text:01281475 mov eax, [ebp+node] .text:01281478 mov ecx, [ebp+data] .text:0128147B mov [eax], ecx .text:0128147D mov eax, [ebp+list] .text:01281480 cmp dword ptr [eax], 0 .text:01281483 jnz short loc_128149A

eax and ecx are set to node and data, and the data member of Node is set to the information parameter. Finally, the list head is checked for NULL and if the condition is false that is the list is not NULL, then the following is obtained; notice how the condition set in the source code is compiled to its Boolean opposite in the assembly code:

.text:0128149A mov eax, [ebp+node] .text:0128149D mov ecx, [ebp+list] .text:012814A0 mov edx, [ecx] .text:012814A2 mov [eax+4],edx

eax is set to the node and ecx to the list. The value pointed to by the list head is copied to edx and edx is copied to node base offset + 4 or node->next member.

Now, assume that the condition is true or the list is empty:

.text:01281485 mov eax, [ebp+list] . text:01281488 mov ecx, [ebp+node] .text:0128148B mov [eax+4],ecx

eax and ecx are set to the value contained at the base offsets of the list and node structures. The dereferenced node address gives the data pointer of the start of the MalwareInfo structure referenced by the node. This value is copied to the list tail member, and the node's next member is set to 0 or NULL.

.text:0128148E mov eax, [ebp+node] .text:01281491 mov dword ptr [eax+4],0 .text:00413926 call traverseList(_linkedList *) .text:0041392B add esp, 4

Can you analyze the rest in IDA Pro and try to figure out how the traverseList function works? Tip: Remember how NULL is represented in disassembly.