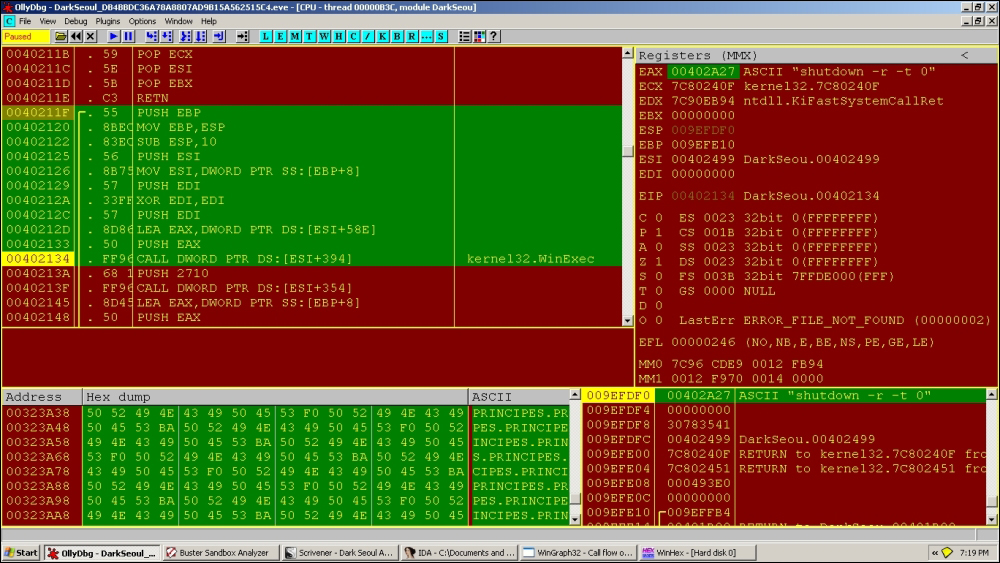

The shutdown function is executed as follows:

0040211F /. 55 PUSH EBP 00402120 |. 8BEC MOV EBP,ESP 00402122 |. 83EC >SUB ESP,10 00402125 |. 56 PUSH ESI 00402126 |. 8B75 >MOV ESI,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8] 00402129 |. 57 PUSH EDI 0040212A |. 33FF XOR EDI,EDI 0040212C |. 57 PUSH EDI 0040212D |. 8D86 >LEA EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+58E] 00402133 |. 50 PUSH EAX 00402134 |. FF96 >CALL DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+394] ;kernel32.WinExec

With parameters:

Nopping that part out (select the code area in the CPU window, press space, type nop in the dialog box, and then press Enter), so that it does not execute, we reach:

0040213A |. 68 10>PUSH 2710 0040213F |. FF96 >CALL DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+354] ; kernel32.Sleep

You can change the value in the stack just before the call to sleep is made to 0 to save time.

Call to LookupPrivilegeValue():

00402164 |. 8D86 >LEA EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+59F] 0040216A |. 50 PUSH EAX 0040216B |. 57 PUSH EDI 0040216C |. FF96 >CALL DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+32C]

Next:

0040217A |. FF75 >PUSH DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8] 0040217D |. C745 >MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-10],1 00402184 |. C745 >MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-4],2 0040218B |. FF96 >CALL DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+330] ; advapi32.AdjustTokenPrivileges 009EFDD0 00402191 /CALL to AdjustTokenPrivileges from DarkSeou.0040218B 009EFDD4 00000058 |hToken = 00000058 (window) 009EFDD8 00000000 |DisableAllPrivileges = FALSE 009EFDDC 009EFE00 |pNewState = 009EFE00 009EFDE0 00000000 |PrevStateSize = 0 009EFDE4 00000000 |pPrevState = NULL 009EFDE8 00000000 \pRetLen = NULL

Finally:

0040219B |. 68 03>PUSH 80020003 004021A0 |. 6A 05 PUSH 5 004021A2 |. FF96 >CALL DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+3D0] ; USER32.ExitWindowsEx

If this fails for some reason, ExitThread() is called from Kernel32.dll and it is the last function to execute.

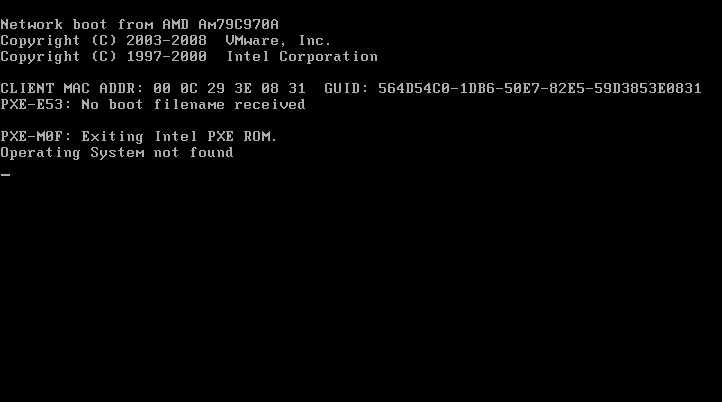

On reboot, you get the following message:

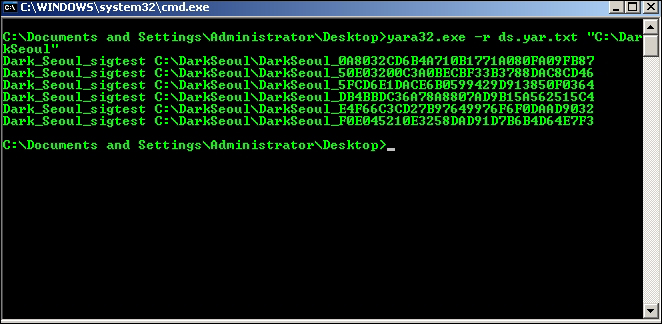

There are six malware samples in the pack collected from Contagio dump, so you can try to write static as well as generic signatures after analyzing each of the malware samples. As a preliminary countermeasure, doing this in Yara is a breeze with its myriad options to combine text and hex strings. After writing the following signature, you can run Yara as:

yara –r <signature file.yar> <path to malware folder>

This detects all the samples in the pack (sans the dropper, which is a separate executable):

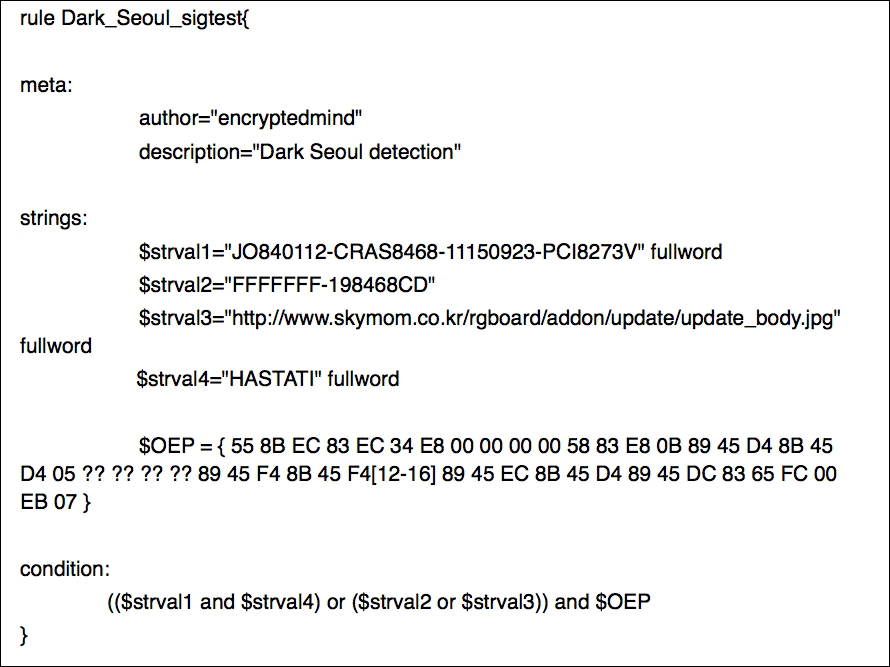

The –r switch is for the recursive search mode and ds.yar.txt is the signature text file, and is shown in the preceding exhibit:

The various parts of the Yara signature are the meta section containing metadata or the unprocessed text that are name value pairs used to annotate the signature and provide additional information to the user. The strings section is where you write textual and hex-based markers as a database of rules, and this is not mandatory if you feel that strings are not needed. The condition section is where the Boolean conditions are implemented taking the data available in the strings section to validate a positive detection.

The $OEP identifier uses wild cards and jumps to accommodate byte level differences in the executable entrypoint code from sample to sample. In the other identifiers, the fullword modifier is used to enable the whole string to be used as a unit or separate word.

You will find that other parameters from the PE headers could also be taken. Timestamp ranges are repetitive in the binary. The file size meanders around 24,000 bytes mark with repeating numbers. Various code sections can be wild carded and jump effected to wrap the whole collection, especially the hashing functions and the payload parts. This can be a good exercise for you to enjoy undertaking.

Finally, while the bulk of the malware has been analyzed, be on the lookout for additional unreachable code regions that might be templates for future variants and double-check the percent of code real estate you have covered. While this will ostensibly take a lot more resources from your end and is very much a trial and error method, you can ideally build a whiltelist (the majority of the AV vendors have this) of legitimate applications and run your generic signatures on them to flag any false positives. This step will help tune your signatures to mark only the malicious code. Just for the sake of interest as to the impact of false positives, you can search the Internet for news related to AV vendors and some of the case stories of how customers had to deal with files getting deleted off their machines because the AV product thinks it is malicious, and the repercussions. Signature testing is a serious business inside an antivirus company as the stakes are high and it can take many hours or even a day or two before they get "released" internally toward the final build, with lots of staged checks and automated testing using machine learning algorithms. The signatures themselves are compiled to the proprietary binary format of the vendor to speed up performance and to prevent IP theft and reversing of the sig-database. All in all, make judicious use of IDA Pro's FLIRT technology and comment out all analyzed code in the IDB database. You could also leverage power tools such as Zynamics Bindiff and BinNavi to do more in-depth analyses if so required and if time permits. The code regions in focus can then be further analyzed to provide conjecture that may be of use in the times ahead. However, remind yourself of the point of diminishing returns to the amount of continued effort needed and know when to call it a day, especially when time is a priced commodity and the major scoops are taken!

Another good habit for a malware analyst to uphold is to take regular backups of your analysis sessions—all samples, notes, screenshots, video recordings, and memory dumps can be collected in a master folder, named after the malware and its hash, annotated and selectively included within Scrivener. If permitting, you should take online cloud backups of all analysis assets for safe storage. This is purely for personal insurance and posterity.