When we decode a GeoRef code, we have to separate the two parts: the four characters at the beginning and the numeric details at the end. Once we've split off the first four characters, we can divide the number of remaining characters in half. One half of the digits will be longitude and the rest will be latitude.

The first four characters must be looked up in our special GeoRef alphabet. We'll find each character's position in the ABCDEFGHJKLMNPQRSTUVWXYZ string to get a numeric value. An expression such as georef_uppercase.find('Q') gives us 14: the position of Q in that alphabet. We can then multiply one position by 15° and add the other position number to translate two characters to the degrees portion of GeoRef.

The remaining digits are simply minutes, which are 1/60 of a degree. During conversion there is a matter of creating a number and possibly dividing it by 10 or 100. The final step is to take out the offsets that were used to avoid signed arithmetic.

The whole thing looks like this:

def georef_2_ll( grid ):

lon_0, lat_0, lon_1, lat_1= grid[:4]

rest= grid[4:]

pos= len(rest)//2

if pos:

scale= { 4: 100, 3: 10, 2: 1 }[pos]

lon_frac, lat_frac = float(rest[:pos])/scale, float(rest[pos:])/scale

else:

lon_frac, lat_frac = 0, 0

lat= georef_uppercase.find(lat_0)*15+georef_uppercase.find(lat_1)+lat_frac/60

lon= georef_uppercase.find(lon_0)*15+georef_uppercase.find(lon_1)+lon_frac/60

return lat-90, lon-180This works by separating the first four positions of the code into four longitude and latitude characters. Note that the positions are interleaved: longitude first, latitude second.

The rest of the string is divided in half. If there are any characters in the second half, then the first half (two, three, or four characters) will be longitude minutes; the second half will be latitude minutes.

We've used a simple literal mapping from the length (two, three, or four) to the scaling values (1, 10, and 100). We defined a dictionary with the mapping from the position to scale factor and applied the number of positions, pos, to that dictionary. We could have done this using an arithmetic calculation, too: 10**(pos-1); this calculation also works to convert pos to a power of 10.

We will take the string of characters, convert them to float and then scale them to create a proper value for minutes. Here is an example of what the scaling looks like:

>>> float("5063")/100

50.63The else condition handles the case where there are only four positions in the grid code. If this is true, then the letters are all we have and the minutes will be zero.

We can calculate the offset values using one letter scaled by 15°, the next letter scaled by 1°, and the minutes by the 60th of a degree. The final step, of course, is to remove the offsets to create the expected signed numbers.

Consider that we use this:

print( georef_2_ll( "GJPG425506" ) )

We'll see an output like this:

(36.843333333333334, -76.29166666666667)

We chopped the longer GeoRef down to a 10-digit code. This has two 3-digit encodings of the minutes. We have elected to lose some accuracy, but this can also simplify the transmission of secret information.

As compared to relatively simple grid codes covered previously, we have an alternative notation called the Maidenhead system. This is used by Ham radio operators to exchange information about the locations of their stations. Maidenhead is a town in England; the Maidenhead code is IO91PM.

For more information, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maidenhead_Locator_System.

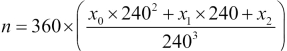

The Maidenhead algorithms involve somewhat more sophisticated math based on creating a base 240 representation of the latitude and longitude numbers. We can encode each digit of a base 240 number using a letter-digit combination. We'll show a common technique to convert a floating-point number to an integer using a series of steps.

The Maidenhead system slices the world map into a 180 × 180 grid of quadrangles; each quadrangle has 1° in the N-S direction and 2° in the E-W direction. We can encode these quadrangles using a base 240 numbering system where a letter and digit are used to denote each of the digits of the base 240 system. Since the grid is only 180×180, we don't need the full range of our base 240 numbers.

To specify a position more accurately, we can slice each cell of the grid into 240 x 240 smaller cells. This means that an eight-position code gets us within .25 nautical miles in the N-S direction and .5 nautical miles in the E-W direction. For Ham radio purposes, this may be sufficient. For our address-level geocoding, we'll need more accuracy.

We can apply the same letter-number operation a third time, dividing each tiny rectangle into 240 even smaller pieces. This gets us more than the accuracy we need.

We are creating a three-digit number in a 240-number system where each base 240 digit is represented by a letter-number pair. We're performing the following calculation to create the three digits  that encode a number,

that encode a number,  :

:

Here's the whole process:

def ll_2_mh( lat, lon ):

def let_num( v ):

l, n = divmod( int(v), 10 )

return string.ascii_uppercase[l], string.digits[n]

f_lat= lat+90

f_lon= (lon+180)/2

y0, y1 = let_num( f_lat )

x0, x1 = let_num( f_lon )

f_lat= 240*(f_lat-int(f_lat))

f_lon= 240*(f_lon-int(f_lon))

y2, y3 = let_num( f_lat )

x2, x3 = let_num( f_lon )

f_lat= 240*(f_lat-int(f_lat))

f_lon= 240*(f_lon-int(f_lon))

y4, y5 = let_num( f_lat )

x4, x5 = let_num( f_lon )

return "".join( [

x0, y0, x1, y1, x2, y2, x3, y3, x4, y4, x5, y5 ] )We've defined an internal function, let_num(), inside our ll_2_mh() function. The internal let_num() function translates a number in the 0 to 240 range into a letter and a digit. It uses the divmod() function to decompose the number into a quotient from 0 to 24 and a remainder from 0 to 9. This function then uses these two numeric values as indices in the string.ascii_uppercase and string.digits strings to return two characters. Each letter-number pair is a representation for a single digit of the base 240 number system. Rather than invent 240-digit symbols, we've repurposed a letter-digit pair to write the 240 distinct values.

The first real step is to convert the raw, signed latitude and longitude to our maidenhead grid version. The f_lat variable is the original latitude with an offset of 90 to make it strictly positive, in the range 0 to 180. The f_lon variable is the original longitude offset by 180 and divided by 2 to make it strictly positive, in the range 0 to 180. We created the initial letter-number pairs from these initial values of degrees: f_lat and f_lon.

This works nicely for degrees. What about the fractions of a degree? Here's a common technique to work with representations of floating-point values.

If we use something like lat-int(lat), we'll compute the fractional portion of the latitude. If we scale that by 240, we'll get a number that we can use with divmod() to get one of the 240-letter positions and a digit. The expression 240*(f_lat-int(f_lat)) will expand the fractional part of f_lat to a scale of 0 to 240. Here's an example of how this scaling works:

>>> f_lat= 36.84383 >>> 240*(f_lat-int(f_lat)) 202.51919999999927 >>> 240*.84383 202.51919999999998

The original latitude is 36.84383. The value of f_lat-int(f_lat) will be the fractional portion of that value, which is .84383. We multiply this by 240 to get the value, with an approximate result of 202.5192.

We used the let_num() function to create a letter-and-digit pair. The remaining fractional value (0.5192) can be scaled again by 240 to get yet another letter-and-digit pair.

At this point, the details have reached the limit of relevance. 1/240/240 of a degree is about 6 feet. Most civilian GPS instruments are only accurate to about 16 feet.

The final step is to interleave longitude and latitude characters. We've done this by creating a list of characters in the desired order. The string.join() method uses the given string as a separator when assembling a list of strings. It's common to use ", ".join(some_list) to create comma-separated items. We have used "".join() to assemble the final string with no separator characters.

Here's a more complete example of the output. We'll encode 36°50.63′N 076°17.49′W:

lat, lon = 36+50.63/60, -(76+17.49/60) print( lat, lon ) print( ll_2_mh( lat, lon ) )

We converted degrees and minutes to degrees. Then, we applied our Maidenhead conversion to the values in degrees. The output looks like this:

36.843833333333336 -76.28333333333333 FM16UU52AM44

We can use portions of this to encode with varying degrees of accuracy. FM16 is pretty coarse, whereas FM16UU is more accurate.

To decode the Maidenhead codes, we need to reverse the procedure we used to create the codes from latitudes and longitudes. We'll need to take all the even positions as a sequence of digits to create the longitude and all the odd positions as a sequence of digits to create the latitude. By looking up against string.ascii_uppercase and string.digits, we can transform characters into numbers.

Once we have a sequence of numbers, we can apply a sequence of weighing factors and add up the results. The whole thing looks like this:

def mh_2_ll( grid ):

lon= grid[0::2] # even positions

lat= grid[1::2] # odd positions

assert len(lon) == len(lat)

# Lookups will alternate letters and digits

decode = [ string.ascii_uppercase, string.digits,

string.ascii_uppercase, string.digits,

string.ascii_uppercase, string.digits,

]

lons= [ lookup.find(char.upper()) for char, lookup in zip( lon, decode ) ]

lats= [ lookup.find(char.upper()) for char, lookup in zip( lat, decode ) ]

weights = [ 10.0, 1.0,

1/24, 1/240,

1/240/24, 1/240/240, ]

lon = sum( w*d for w,d in zip(lons, weights) )

lat = sum( w*d for w,d in zip(lats, weights) )

return lat-90, 2*lon-180We used Python's very elegant slice notation to take the string apart into even and odd positions. The expression grid[0::2] specifies a slice of the grid string. The [0::2] slice starts at position 0, extends to the very end, and increments by 2. The [1::2] slice starts at position 1, extends to the very end, and also increments by 2.

The decode list contains six strings that will be used to translate each character into a numeric value. The first character will be found in string.ascii_uppercase and the second character will be found in string.digits. The positions at which the characters are found in these strings will become the numeric values that we can use to compute latitudes and longitudes.

For example, the value of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'.find('M') is 12.

We've used a generator expression and the zip() function to do the real work of the translation. The zip() function will produce a sequence of pairs; each pair will have one character chosen from the input grid code and one lookup string chosen from the decode lists. We can then use lookup.find(char.upper()) to locate the given character in the given lookup string. The result will be a sequence of integer positions.

Once we have a sequence of the numeric values, we can apply the sequence of weightings to convert each position to a degree or a fraction of a degree. Again, we used zip() to create two-tuples from the digits and the weights. The generator then multiplied the numeric value by the weight. The built-in sum() function created the final value from the numbers and weights.

For example, we might have a value in the lons variable of [5, 1, 20, 6, 0, 0]. The weights are [10.0, 1.0, 0.0416, 0.00416, 0.00017361, 1.7361e-05]. When we use zip() to zip these two sequences, we'll get pairs like this:

[(5, 10.0), (1, 1.0), (20, 0.0416), (6, 0.00416), (0, 0.00017361), (0, 1.7361e-05)]

The products look like this:

[50.0, 1.0, 0.832, 0.024959999999999996, 0.0, 0.0]

The sum is 51.85696.

The final step is to undo the offsets we used to force the latitudes to be positive and the longitudes to have values between 0 and 180 instead of -180 to +180. The intermediate longitude result 51.85696 becomes -76.28608.

Consider that we evaluate this:

print( mh_2_ll( "FM16UU62" ) )

We get the following decoded positions:

(36.84166666666667, -76.28333333333333)

This nicely decodes the values we encoded in the previous section.