There are many more things we can do with image files. One thing we can do is use steganography to conceal messages inside image files. As image files are large, complex, and relatively noisy, adding a few extra bits of data won't make much of a visible change to the image or the file.

Sometimes this is summarized as adding a digital watermark to an image. We're going to subtly alter the image in a way that we can recognize and recover it later.

Adding a message can be seen as a lossy modification to the image. Some of the original pixels will be unrecoverable. As the JPEG compression, in general, already involves minor losses, tweaking the image as part of steganography will be a similar level of image corruption.

Speaking of losses, the JPEG format can, and will, tweak some of the bits in our image. Consequently, it's difficult to perform steganography with JPEG. Rather than wrestle with JPEG details, we'll use the TIFF format for our concealed messages.

There are two common approaches to concealing a message in an image:

- Using a color channel: If we overwrite some bytes in just one color channel, we'll be shifting a part of the color of a few pixels in the area we overwrote. It will only be a few of millions of pixels, and it will only be one of the three (or four) colors. If we confine the tweaking to the edge, it's not too noticeable.

- Using the least significant bits (LSBs) of each byte: If we overwrite the least significant bit in a series of bytes, we'll make an extremely minor shift in the image. We have to limit the size of our message because we can only encode one byte per pixel. A small picture that's 432 * 161 = 69,552 pixels can encode 8,694 bytes of data. If we use the UTF-8 encoding for our characters, we should be able to cram an 8 K message into that image. If we use UTF-16, we'd only get a 4 K message. This technique works even for grayscale images where there's only one channel.

In addition to the JPEG compression problem, there are some color encoding schemes that don't work out well with either of these steganography approaches. The modes, known as P, I, and F, present a bit of a problem. These color modes involve mapping a color code to a palette. In these cases, the byte is not the level of gray or the level of a color; when using a palette, the bytes are a reference to a color. Making a 1-bit change might lead to a profound change in the color selected from the underlying palette. The color 5 might be a pleasant sea-foam green, the color 4 might be an awful magenta. A 1-bit change between 5 and 4 may be a noticeable out-of-place dot.

For our purposes, we can switch the source image to RGB (or CMYK) before applying our steganography encoding. The basic change to the color mode might be visible to someone who had access to the original image. However, the hidden message will remain obscured unless they also know our steganography algorithm.

Our strategy works like this:

- Get the bytes from the pixels of the image.

- Transform our secret message from a Unicode string into a sequence of bits.

- For each bit of our secret message, adulterate 1 byte of the original image. As we're tweaking the least significant bit, one of two things will happen.

- We'll make an image pixel value into an even number to encode a 0 bit from our secret message

- We'll make an image pixel value into an odd number to encode a 1 bit from our secret message

We'll work with two parallel sequences of values:

- The bytes from the image (ideally enough to encode our entire message)

- The bits from our secret message

The idea is to step through each byte of the image and incorporate 1 bit of the secret message into that image byte. The cool feature of this is that some pixel values might not need to actually change. If we're encoding a byte in a pixel that's already odd, we won't change the image at all.

This means that we need to perform the following important steps:

- Get the bytes in the red channel of the image

- Get the bytes from a Unicode message

- Get the bits from the message bytes

- Tweak the image pixel byte using a message bit, and update the image

We'll tackle these one at a time, then we'll weld it all together at the end.

Let's look at encoding our message in an image using the red channel LSB encoding. Why red? Why not? Men may have some degree of red-green color blindness; if they're less likely to see a shift in this channel, then we've further concealed our image from a few prying eyes.

The first question is this: how do we tinker with the bytes of the original image?

The PIL Image object has the getpixel() and putpixel() methods that allow us to get the various color band values.

We can peel out individual pixels from the image like this:

>>> y = 0 >>> for x in range(64): ... print(ship.getpixel( (x,y) )) ... (234, 244, 243) (234, 244, 243) (233, 243, 242) (233, 243, 242) etc.

We've provided an (x,y) two-tuple to the getpixel() method. This shows us that each pixel in the image is a three-tuple. It's not obvious what the three numbers are. We can use ship.getbands() to get this information, as shown in the following snippet:

>>> ship.getbands()

('R', 'G', 'B')There was little doubt in our minds that the three pixel values were red level, green level, and blue level. We've used the getband() method to get confirmation from Pillow that our assumption about the image encoding band was correct.

We now have access to the individual bytes of the image. The next steps are to get the bits from our secret message and then adulterate the image bytes with our secret message bits.

In order to encode our secret message into the bytes of an image, we'll need to transform our Unicode message into bytes. Once we have some bytes, we can then make one more transformation to get a sequence of bits.

The second question, is how do we get the individual bits of the message text? Another form of this question is, how do we turn a string of Unicode characters into a string of individual bits?

Here's a Unicode string we can work with: http://www.kearsarge.navy.mil. We'll break the transformation into two steps: first to bytes and then to bits. There are a number of ways to encode strings as bytes. We'll use the UTF-8 encoding as that's very popular:

>>> message="http://www.kearsarge.navy.mil"

>>> message.encode("UTF-8")

b'http://www.kearsarge.navy.mil'It doesn't look like too much happened there. This is because the UTF-8 encoding happens to match the ASCII encoding that Python byte literals use. This means that the bytes version of a string, which happens to use only US-ASCII characters, will look very much like the original Python string. The presence of special b' ' quotes is the hint that the string is only bytes, not full Unicode characters.

If we had some non-ASCII Unicode characters in our string, then the UTF-8 encoding would become quite a bit more complex.

Just for reference, here's the UTF-16 encoding of our message:

>>> message.encode("UTF-16")

b'\xff\xfeh\x00t\x00t\x00p\x00:\x00/\x00/\x00w\x00w\x00w\x00.\x00k\x00e\x00a\x00r

\x00s\x00a\x00r\x00g\x00e\x00.\x00n\x00a\x00v\x00y\x00.\x00m\x00i\x00l\x00'The previous encoded message looks to be a proper mess. As expected, it's close to twice as big as UTF-8.

Here's another view of the individual bytes in the message:

>>> [ hex(c) for c in message.encode("UTF-8") ]

['0x68', '0x74', '0x74', '0x70', '0x3a', '0x2f', '0x2f', '0x77', '0x77', '0x77', '0x2e', '0x6b', '0x65', '0x61', '0x72', '0x73', '0x61', '0x72', '0x67', '0x65', '0x2e', '0x6e', '0x61', '0x76', '0x79', '0x2e', '0x6d', '0x69', '0x6c']We've used a generator expression to apply the hex() function to each byte. This gives us a hint as to how we're going to proceed. Our message was transformed into 29 bytes, which is 232 bits; we want to put these bits into the first 232 pixels of our image.

As we'll be fiddling with individual bits, we need to know how to transform a Python byte into a tuple of 8 bits. The inverse is a technique to transform an 8-bit tuple back into a single byte. If we expand each byte into an eight-tuple, we can easily adjust the bits and confirm that we're doing the right thing.

We'll need some functions to expand a list of byte into bits and contract the bits back to the original list of bytes. Then, we can apply these functions to our sequence of bytes to create the sequence of individual bits.

The essential computer science is explained next:

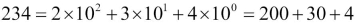

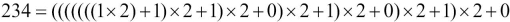

A number,  , is a polynomial in some particular base. Here's the polynomial for the value of 234 with base 10:

, is a polynomial in some particular base. Here's the polynomial for the value of 234 with base 10:

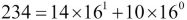

In base 16, we have  . When writing hex, we use letters for the 14 and 10 digits:

. When writing hex, we use letters for the 14 and 10 digits: 0xea.

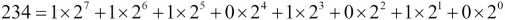

This kind of polynomial representation is true in base 2. A number,  , is a polynomial in base 2. Here's the polynomial for the value of 234:

, is a polynomial in base 2. Here's the polynomial for the value of 234:

Here's a way to extract the lower 8 bits from a numeric value:

def to_bits( v ):

b= []

for i in range(8):

b.append( v & 1 )

v >>= 1

return tuple(reversed(b))The v&1 expression applies a bitwise operation to extract the rightmost bit of a number. We'll append the calculated bit value to the b variable. The v >>= 1 statement is the same as v = v>>1; the v>>1 expression will shift the value, v, one bit to the right. After doing this eight times, we've extracted the lowest bits of the v value. We've assembled this sequence of bits in a list object, b.

The results are accumulated in the wrong order, so we reverse them and create a tidy little eight-tuple object. We can compare this with the built-in bin() function:

>>> to_bits(234) (1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0) >>> bin(234) '0b11101010'

For a value over 127, both the bin() and to_bits() functions produce 8-bit results. For smaller values, we'll see that the bin() function doesn't produce 8 bits; it produces just enough bits.

The opposite transformation evaluates the polynomial. We can do a little algebra to optimize the number of multiplications:

Because of the grouping, the leftmost 1 winds up multiplied by  . As shifting bits to the left is the same as multiplying by 2, we can reconstruct the a byte value from a tuple of bits as follows:

. As shifting bits to the left is the same as multiplying by 2, we can reconstruct the a byte value from a tuple of bits as follows:

def to_byte( b ):

v= 0

for bit in b:

v = (v<<1)|bit

return vThe (v<<1)|bit expression will shift v to the left 1 bit, effectively performing a *2 operation. An OR operation will fold the next bit into the value being accumulated.

We can test these two functions with a loop like this:

for test in range(256):

b = to_bits(test)

v = to_byte(b)

assert v == testIf all 256 byte values are converted to bits and back to bytes, we are absolutely sure that we can convert bytes to bits. We can use this to see the expansion of our message:

message_bytes = message.encode("UTF-8")

print( list(to_bits(c) for c in message_bytes) )This will show us a big list of 8-tuples:

[(1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1), (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0), (0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0), ... (0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)]

Each byte of the secret message has become an eight-tuple of individual bits.

At this point, we've got two parallel sequences of values:

The idea is to step through each byte of the image and incorporate one bit of the secret message into that byte.

Before we can fully tweak the various image bytes with our message bits, we need to assemble a long sequence of individual bits. We have two choices to do this. We can create a list object with all of the bit values. This wastes a bit of memory, and we can do better.

We can also create a generator function that will appear to be a sequence object with all of the bits.

Here's a generator function that we can use to emit the entire sequence of bits from the message:

def bit_sequence( list_of_tuples ):

for t8 in list_of_tuples:

for b in t8:

yield bWe've stepped through each individual eight-tuple in the list-of-tuples values that can be created by our to_bits() function. For each bit in the 8-tuple, we've used the yield statement to provide the individual bit values. Any expression or statement that expects an iterable sequence will be able to use this function.

Here's how we can use this to accumulate a sequence of all 232 bits from a message:

print( list( bit_sequence(

(to_bits(c) for c in message_bytes)

) ) )This will apply the to_bits() function to each byte of the message, creating a sequence of 8-tuples. Then it will apply the bit_sequence() generator to that sequence of eight-tuples. The output is a sequence of individual bits, which we collected into a list object. The resulting list looks like this:

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ... 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

We can see the list of 232 individual bits built from our original message.

Here's the inverse to the bit_sequence() function. This will group a sequence of bits into eight-tuples:

def byte_sequence( bits ):

byte= []

for n, b in enumerate(bits):

if n%8 == 0 and n != 0:

yield to_byte(byte)

byte= []

byte.append( b )

yield to_byte(byte)We've used the built-in enumerate() generator function to provide a number for each individual bit in the original sequence. The output from the enumerate(bits) expression is a sequence of two-tuples; each two-tuple has the enumerated bit number (from 0 to 231) and the bit value itself (0 or 1).

When the bit number is a multiple of 8 (n%8 == 0), we've seen a complete batch of eight bits. We can convert these eight bits to a byte with to_byte(), yield the byte value, and reset our temporary accumulator, byte, to be empty.

The enumerate() function will assign the very first byte number 0; since 0%8 == 0, it looks like we've just accumulated eight bits to make a byte. We've avoided this complication by assuring that n is not 0; it's not the first bit value. We could also have used the len(byte) != 0 expression to avoid the first-time complication.

The final yield statement is critical for success. The final batch of bits will have n%8 values of 0 to 7. The n%8 test won't be used when the collection of bits is exhausted, but we'll still have eight bits accumulated in the byte variable. We yield this final batch of eight bits as an extra step.

Here's what it looks like:

>>> list(byte_sequence(bits)) [255, 254, 104, 0, 116, 0, 116, 0, 112, 0, 58, 0, 47, 0, 47, 0, 119, 0, 119, 0, 119, 0, 46, 0, 107, 0, 101, 0, 97, 0, 114, 0, 115, 0, 97, 0, 114, 0, 103, 0, 101, 0, 46, 0, 110, 0, 97, 0, 118, 0, 121, 0, 46, 0, 109, 0, 105, 0, 108, 0]

We've taken the sequence of individual bits and collected each batch of eight bits into bytes.

Now that we can transform any Unicode string into bits, we can encode a message into an image. The final nuance is how to delimit the message. We don't want to accidentally decode each byte in the entire image. If we did this, our message will be padded with random characters. We need to know when to stop decoding.

One common technique is to include a terminator character. Another common technique is to provide a length in front of the string. We're going to include a length in front of the string so that we aren't constrained by the contents of the string or the encoded bytes that are produced from that string.

We'll use a 2-byte length in front of the string; we can encode it into bytes and bits like this:

len_H, len_L = divmod( len(message), 256 ) size = [to_bits(len_H), to_bits(len_L)]

We've used the Python divmod() function to compute the quotient and remainder after division. The results of the divmod( len(message), 256 ) expression will be len(message)//256 and len(message)%256. We can recover the original value from the len_H*256+len_L expression.

The size variable is set to a short sequence composed of two eight-tuples built from the len_H and len_L values.

The complete sequence of bytes, including the length, looks like this:

message_bytes= message.encode("UTF-8")

bits_list = list(to_bits(c) for c in message_bytes )

len_h, len_l = divmod( len(message_bytes), 256 )

size_list = [to_bits(len_h), to_bits(len_l)]

bit_sequence( size_list+bits_list ) First, we encoded the message into bytes. Depending on the Unicode characters involved and the encoding used, this may be longer than the original message. The bits_list variable is a sequence of eight-tuples built from the various bytes of the encoded message.

Then, we created two more bytes with the length information and converted them to bits. The size_list variable is a sequence of eight-tuples built from the bytes of the encoded size.

The size_list+bits_list expression shows how to concatenate the two sequences to create a long sequence of individual bits that we can embed into our image.

Here's how we use the putpixel() and getpixel() methods to update the image:

w, h = ship.size

for p,m in enumerate( bit_sequence(size_list+bits_list) ):

y, x = divmod( p, w )

r, g, b = ship.getpixel( (x,y) )

r_new = (r & 0xfe) | m

print( (r, g, b), m, (r_new, g, b) )

ship.putpixel( (x,y), (r_new, g, b) )We've extracted the size of the original image; this tells us how long the x axis is so that we can use multiple rows of the image if necessary. If our image only has 128 pixels on a row, we'll need more than one row for a 292-bit message.

We've applied the enumerate() function to the bit_sequence(size_list+bits_list) value. This will provide both a sequence number and an individual bit from the original message. The sequence number can be converted to a row and column using the divmod() function. We'll set y to sequence // width; we'll set x to sequence % width.

If we use the thumbnail image, which is 128-pixels wide, the first 128 bits go to row 0. The next 128 bits go to row 1. The balance of the 292 bits will wind up on row 3.

We got the RGB values from the pixel using ship.getpixel( (x,y) ).

We've highlighted the bit-fiddling part: r_new = (r & 0xfe) | m. This uses a

mask value of 0xfe, which is 0b11111110. This works because the & operator has a handy feature. When we use b&1, the value of b is preserved. When we use b&0, the result is 0.

Try it, as shown in the following code:

>>> 1 & 1 1 >>> 0 & 1 0

The value of b (either 1 or 0) was preserved. Similarly, 1 & 0 and 0 & 0 are both 0.

Using a mask value in (r & 0xfe) means that the leftmost seven bits of r will be preserved; the rightmost bit will be set to 0. When we use (r & 0xfe) | m, we'll be folding the value of m into the rightmost position. We've printed out the old and new pixel values to provide some details on how this works. Here are two rows from the output:

(245, 247, 246) 0 (244, 247, 246) (246, 248, 247) 1 (247, 248, 247)

We can see that the old value of the red channel was 245:

>>> 245 & 0xfe 244 >>> (245 & 0xfe) | 0 244

The value 244 shows how the rightmost bit was removed from 245. When we fold in a new bit value 0, the result remains 244. An even value encodes a 0 bit from our secret message.

In this case, the old value of the red channel was 246:

>>> 246 & 0xfe 246 >>> (246 & 0xfe) | 1 247

The value remains 246 when we remove the rightmost bit. When we fold in a new bit value of 1, the result becomes 247. An odd value encodes a one bit from our secret message.

After all, we've only tweaked the level of the red in the image by plus or minus 1 on a scale of 256, less than half percent change.

We will decode a message concealed with steganography in two steps. The first step will decode just the first two bytes of length information, so we can recover our embedded message. Once we know how many bytes we're looking for, we can decode the right number of bits, recovering just our embedded characters, and nothing more.

As we'll be dipping into the message twice, it will help to write a bit extractor. Here's the function that will strip bits from the red channel of an image:

def get_bits( image, offset= 0, size= 16 ):

w, h = image.size

for p in range(offset, offset+size):

y, x = divmod( p, w )

r, g, b = image.getpixel( (x,y) )

yield r & 0x01We've defined a function with three parameters: an image, an offset into the image, and a number of bits to extract. The length information is an offset zero and has a length of 16 bits. We set those as default values.

We used the a common divmod() calculation to transform a position into y and x coordinates based on the overall width of the image. The y value is position//width; the x value is position%width. This matches the calculation carried out when embedding bits into the message.

We used the image's getpixel() method to extract the three channels of color information. We used r & 0x01 to calculate just the rightmost bit of the red channel.

As the value was returned with a yield statement, this is a generator function: it provides a sequence of values. As our byte_sequence() function expects a sequence of values, we can combine the two to extract the size, as shown in the following code:

size_H, size_L = byte_sequence( get_bits( ship, 0, 16 ) ) size= size_H*256+size_L

We grabbed 16 bits from the image using the get_bits() function. This sequence of bits was provided to the byte_sequence() function. The bits were grouped into eight-tuples and the eight-tuples transformed into single values. We can then multiply and add these values to recover the original message size.

Now that we know how many bytes to get, we also know how many bits to extract. The extraction looks like this:

message= byte_sequence(get_bits(ship, 16, size*8))

We've used the

get_bits() function to extract bits starting from position 16 and extending until we've found a total of size*8 individual bits. We grouped the bits into eight-tuples and converted the eight-tuples to individual values.

Given a sequence of bytes, we can create a bytes object and use Python's decoder to recover the original string. It looks like this:

print( bytes(message).decode("UTF-8") )This will properly decode bytes into characters using the UTF-8 encoding.