Chapter 1. An introduction to D3.js

- The basics of HTML, CSS, and the Document Object Model (DOM)

- The principles of Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG)

- Node and ES2015 functionality

- Data-binding and selections with D3

- Different data types and their data visualization methods

D3 is behind nearly all the most innovative and exciting information visualization on the web today. D3 stands for data-driven documents. It’s a brand name, but also a class of applications that have been offered on the web in one form or another for years. In my career, I’ve made many things that could be considered data-driven documents. These include everything from one-off dynamic maps or social network diagrams to robust visual explorations of time and place. You’ll be using D3 whether you’re building data visualization prototypes for research or big data dashboards at the top tech companies.

1.1. What is D3.js?

D3.js was created to fill a pressing need for web-accessible, sophisticated data visualization. Let’s say your company has used Business Intelligence tools for a while, but they don’t show you the kind of patterns in the data that your team needs. You need to build a custom dashboard that shows exactly how your customers are behaving, tailored for your specific domain. That dashboard needs to be fast, interactive, and shareable around the organization. You’re going to use D3 for that.

D3.js’s creator, Mike Bostock, originally created D3 to take advantage of emerging web standards, which, as he puts it, “avoids proprietary representation and affords extraordinary flexibility, exposing the full capabilities of web standards such as CSS3, HTML5, and SVG” (http://d3js.org). D3.js version 4, the latest iteration of this popular library, continues this trend by modularizing the various pieces of D3 to make it more useful in modern application development.

D3 provides developers with the ability to create rich interactive and animated content based on data and tie that content to existing web page elements. It gives you the tools to create high-performance data dashboards and sophisticated data visualization, and to dynamically update traditional web content.

You might have already experimented with D3 and found that it isn’t easy to get into. Maybe that’s because you expected it to be a simple charting library. A case in point is the pie chart layout, which you’ll see in chapter 5. D3 doesn’t have one single function to create a pie chart. Rather, it has a function that processes your dataset with the necessary angles so that if you pass the dataset to D3’s arc function, you get the drawing code necessary to represent those angles. And you need to use yet another function to create the paths necessary for that code. It’s a much longer process than using dedicated charting libraries, but the explicit manner in which D3 deals with data and graphics is also its strength. Although other charting libraries conveniently allow you to make line graphs and pie charts, they quickly break down when you want to make something different than that. Not D3, which allows you to build whatever data-driven graphics and interactivity you can imagine.

1.2. How D3 works

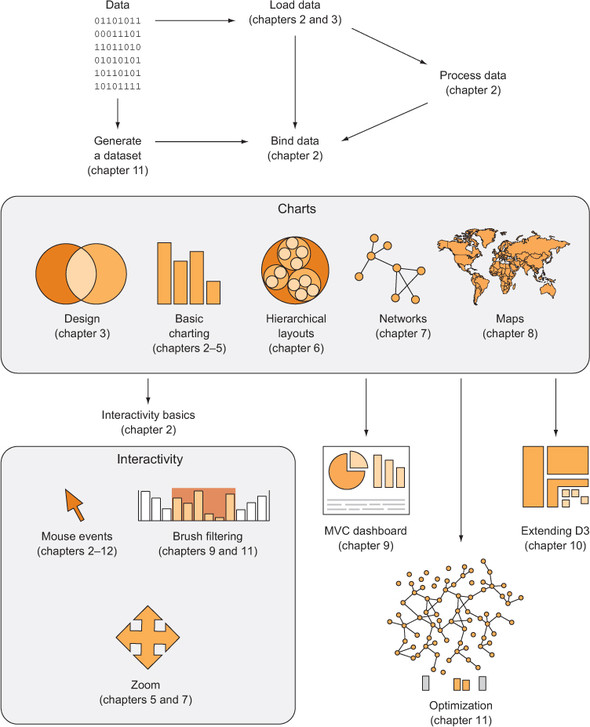

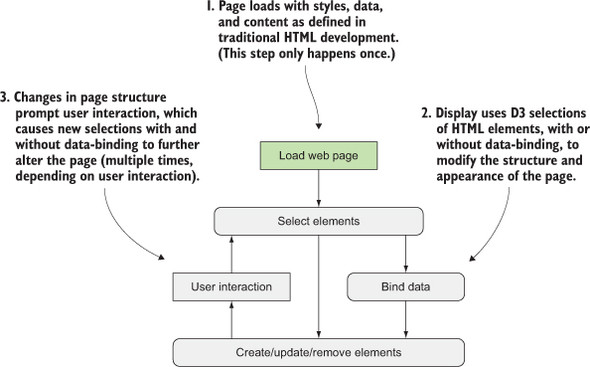

Let’s look at the principles of data visualization, as well as how D3 works in general. In figure 1.1 you see a rough map of how you might start with data and use D3 to process and represent that data, as well as add interactivity and optimize the data visualization you’ve created. In this chapter, we’ll start by establishing the principles of how D3 selections and data-binding work and learning how D3 interacts with SVG and HTML in the DOM. Then we’ll look at data types that you’ll commonly encounter. Finally, we’ll use D3 to create simple DOM and SVG elements.

Figure 1.1. A map of how to approach data visualization with D3.js that highlights the approach in this book. Start at the top with data and then follow the path depending on the type of data and the needs you’re addressing.

1.2.1. Data visualization is more than charts

You may think of data visualization as limited to pie charts, line charts, and the variety of charting methods popularized by Edward Tufte and deployed in research. It’s much more than that. One of the core strengths of D3.js is that it allows for the creation of vector graphics for traditional charting, but also the creation of geospatial and network visualizations, as well as rich animation and interactivity. This broad-based approach to data visualization, where a map or a network graph or a table is another kind of representation of data, is the core of the D3.js library’s appeal for application development.

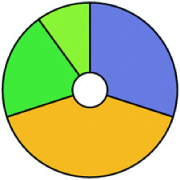

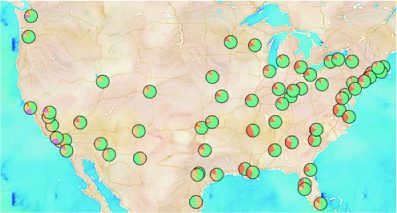

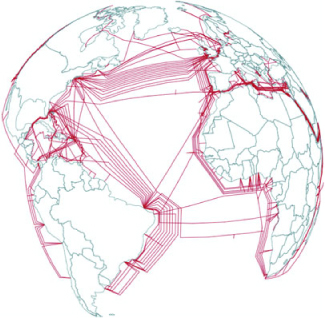

Figures 1.2 through 1.8 show data visualization pieces that I’ve created with D3. They include maps and networks, along with more traditional pie charts and completely custom data visualization layouts based on the specific needs of my clients.

Figure 1.2. D3 can be used for simple charts, such as this donut chart (explained in chapter 5).

Figure 1.3. D3 can also be used to create web maps (see chapter 8), such as this map showing the ethnic makeup of major metropolitan areas in the United States.

Figure 1.4. Maps in D3 aren’t limited to traditional Mercator web maps. They can be interactive globes, like this map of undersea communication cables, or other, more

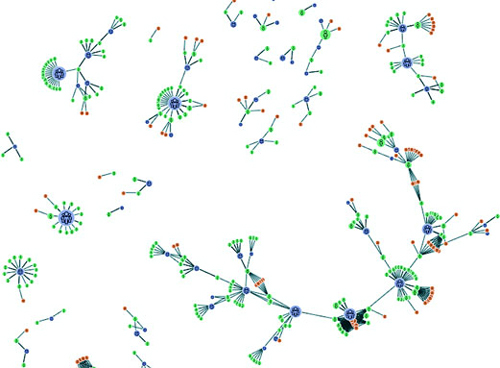

Figure 1.5. D3 also provides robust capacities to create interactive network visualizations (see chapter 7). Here you see the social and coauthorship network of archaeologists working at the same dig for nearly 25 years.

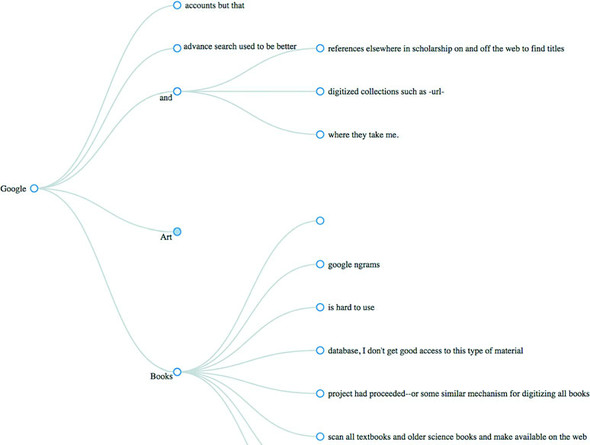

Figure 1.6. D3 includes a library of common data visualization layouts, such as the dendrogram (explained in chapter 6), that let you represent data, such as this word tree.

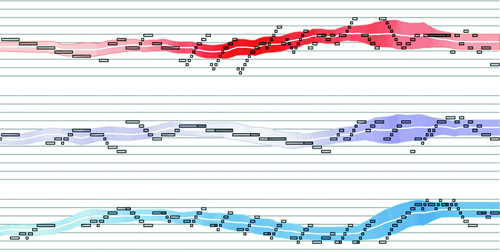

Figure 1.7. D3 has SVG and canvas drawing functions (see chapter 4) so you can create your own custom visualizations, such as this representation of musical scores.

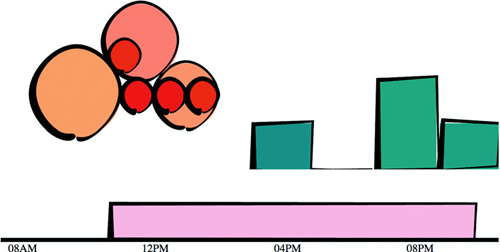

Figure 1.8. You can combine these layouts and functions to create a data dashboard like we’ll do in chapter 9. You can also use the drawing functions to make your bar charts look distinctive, such as this “sketchy” style.

Although the ability to create rich and varied graphics is one of D3’s strong points, more important for modern web development is the ability to embed the high level of interactivity that users expect. With D3, every element of every chart, from a spinning globe to a single, thin slice of a pie chart, is made interactive in the same way. And because D3 was written by someone well versed in data visualization practice, it includes interactive components and behaviors that are standard in data visualization and web development.

You don’t invest your time learning D3 so that you can deploy Excel-style charts on the web. For that, easier, more convenient libraries exist. You learn D3 because it gives you the ability to implement almost every major data visualization technique. It also gives you the power to create your own data visualization techniques, something a more general library can’t do. To see the variety of possibilities available with D3, look at http://blockbuilder.org/search.

D3.js affords developers the capacity to make not only richly interactive applications but also applications that are styled and served like traditional web content. This makes them more portable, more amenable to the growing, linked data web, and more easily maintained by large teams where other team members don’t know the specific syntax of D3 but, for instance, can use CSS to style the data visualization elements.

The decision on Bostock’s part to deal broadly with data and to create a library capable of presenting maps as easily as charts, as easily as networks, as easily as ordered lists, also means that a developer doesn’t need to try to understand the abstractions and syntax of one library for maps, and another for dynamic text content, and another for data visualization. Instead, the code for running an interactive, force-directed network layout is close to pure JavaScript and also similar to the code representing dynamic points of interest (POIs) on a D3.js map. Not only are the methods the same, but the data also could be the same, formulated in one way for lists and paragraphs and spans, while formulated in another way for geospatial representation.

1.2.2. D3 is about selecting and binding

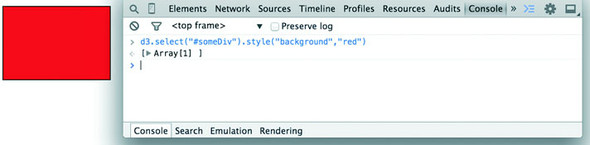

Throughout this chapter, you’ll see code snippets that you can run in your browser to make changes to the graphical appearance of elements on your website. At the end of the chapter is an application written in D3 that explains the basics of the code we’re running in JavaScript. But before that we’ll explore the principles of web development using D3, and you’ll see this pattern of code over and over again: selecting.

Imagine we have a set of data, such as the price and size of a few houses, and a set of web page elements, whether graphics or <div> elements, and that we want to represent the dataset, whether with text or through size and color. A selection is the group of the data and elements together. We perform actions on the elements in the group, such as moving them or changing their color. We can likewise update the values in the data. Though we can work with the data and the web page elements separately, the real power of D3 comes from using selections to combine data and web page elements.

Here’s a selection without any data:

d3.selectAll("circle.a").style("fill", "red").attr("cx", 100);

This takes each circle on our page with the CSS class of a, turns it red, and moves it so that its center is 100 pixels to the right of the left side of our <svg> canvas. Likewise, this code turns every div on our web page red and changes its class to b:

d3.selectAll("div").style("background", "red").attr("class", "b");

But before we can change our circles and divs, we’ll need to create them, and before we do that, it’s best to understand what’s happening in this pattern.

Later in chapter 11 you’ll see how to use D3 with React, a view renderer. Typically, MVC libraries like Angular or view rendering libraries like React are responsible for creating and destroying HTML elements and associating them with certain data-points. In those cases, you might stop using D3 to create and update elements and use it purely as a visualization kernel for your application.

The first part of that line of code, d3.selectAll(), is part of the core functionality necessary for understanding D3: selections. Selections can be made with d3.select(), which selects the first single element found, but more often you’ll use d3.select-All(), which can be used to select multiple elements. Selections are groups of one or more web page elements that may be associated with a set of data, like the following code, which binds the elements in the array [1,5,11,3] to <div> elements with the class of market:

d3.selectAll("div.market").data([1,5,11,3])

This association is known in D3 as binding data, and you can think of a selection as a set of web page elements and a corresponding, associated set of data. Sometimes more data elements exist than DOM elements, or vice versa, in which case D3 has functions designed to create or remove elements that you can use to generate content. Chapter 2 covers selections and data binding in detail. Selections might not include any data binding, and won’t for most of the examples in this chapter, but the inclusion allows the powerful information visualization techniques of D3. You can make a selection on any elements in a web page, including items in a list, circles, or even regions on a map of Africa. The same way the elements can take a number of shapes, the data associated with those elements (where applicable) can take many forms.

1.2.3. D3 is about deriving the appearance of web page elements from bound data

After you have a selection, you can then use D3 to modify the appearance of web page elements to reflect differences in the data. You may want to make the length of a line equal to the value of the data, or change the color to one that corresponds to a class of data. You may want to hide or show elements as they correspond to a user’s navigation of a dataset. As you can see in figure 1.9, after the page has loaded, you use D3 to select elements and bind data for creating, removing, or changing DOM elements. You continue to use this process in response to user interaction.

Figure 1.9. An application created with D3 can use selections and data binding over and over again, together and separately, to update the content of the data visualization based on interaction.

You modify the appearance of elements by using selections to reference the data bound to an element in a selection. D3 iterates through the elements in your selection and performs the same action using the bound data, which results in different graphical effects. Although the action you perform is the same, the effect is different because it’s based on the variation in the data. You’ll see data binding first at the end of this chapter, and in much more detail throughout this book.

1.2.4. Web page elements can now be divs, countries, and flowcharts

We’ve grown accustomed to thinking of web pages as consisting of text elements with containers for pictures, videos, or embedded applications. But as you grow more familiar with D3, you’ll begin to recognize that every element on the page can be treated with the same high-level abstractions. The most basic element on a web page, a <div> that represents a rectangle into which you can drop paragraphs, lists, and tables, can be selected and modified in the same way you can select and modify a country on a web map, or individual circles and lines that make up a complex data visualization.

1.3. The power of HTML5

We’ve come a long way from the days when animated GIFs and frames were the pinnacle of dynamic content on the web. In figure 1.10, you can see why GIFs never caught on for robust data visualization on the web. GIFs, like the infoviz libraries designed to use VML, were necessary for earlier browsers, but D3 is designed for the modern browsers that no longer need backward compatibility.

Figure 1.10. Before GIFs were weaponized to share cute animal behavior, they were your only hope for animated data visualization on the web. Few examples from the 1990s like dpgraph.com still exist, but this page has more than enough GIFs to remind us of their dangers.

Note

SVG knowledge is foundational to understanding D3.js, but if you’re already experienced with the DOM, SVG, and CSS, you can skim this section to refresh your memory, or skip ahead to section 1.3.6 or 1.4.

A modern browser typically can not only display SVG graphics and obey CSS3 rules, but also has great performance. Along with Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), the other elements you need to know about for web development are the DOM (Document Object Model) and JavaScript. The following sections deal with each of them broadly and include code you can run to see how D3 uses their functionality to create interactive and dynamic web content.

1.3.1. The DOM

A web page is structured according to the DOM. You need a passing familiarity with the DOM to do web development, so we’ll take a quick look at DOM elements and structure in a simple web page in your browser and touch on the basics of the DOM. To get started, you’ll need a web server that you can access from the computer that you’re using to code. With that in place, you can download the D3 library from d3js.org (d3.js or d3.min.js for the minified version) and place that in the directory where you’ll make your web page. You’ll create a page called d3ia.html in the text editor with the contents in the following listing.

Listing 1.1. A simple web page demonstrating the DOM

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <script src="d3.v4.min.js"></script> 1 </head> 1 <body> 1 <div id="someDiv" style="width:200px;height:100px;border:black 1px solid;"> 2 <input id="someCheckbox" type="checkbox" /> 3 </div> </body> </html>

Basic HTML like this follows the DOM. It defines a set of nested elements, starting with an <html> element with all its child elements and their child elements and so on. In this example, the <script> and <body> elements are children of the <html> element, and the <div> element is a child of the <body> element. The <script> element loads the D3 library here, or it can have inline JavaScript code, whereas any content in the <body> element shows up onscreen when you navigate to this page.

Three categories of information about each element determine its behavior and appearance: styles, attributes, and properties. Styles can determine transparency, color, size, borders, and so on. Attributes include classes, IDs, and interactive behavior, though certain attributes can also determine appearance, depending on which type of element you’re dealing with. Properties typically refer to states, such as the “checked” property of a check box, which is true if the box is checked and false if the box is unchecked. D3 has three corresponding functions to modify these values. If we wanted to modify the HTML elements in the previous example, we could use D3 functions that abstract this process:

d3.select("#someDiv").style("border", "5px darkgray dashed");

d3.select("#someDiv").attr("id", "newID");

d3.select("#someCheckbox").property("checked", true);

Like many D3 functions of this kind, if you don’t signify a new value, then the function returns the existing value. This way of exposing getter/setter behavior in JavaScript was popularized in JQuery and shows up in most of the D3 examples. You’ll see this in action throughout this book, and later in the chapter as you write more code, but for now remember that these three functions allow you to change how an element appears and interacts.

The DOM also determines the onscreen drawing order of elements, with child elements drawn after and inside parent elements. Although you have partial control over drawing elements above or below each other with traditional HTML using z-index, this won’t be available with SVG elements until the SVG2 spec is implemented.

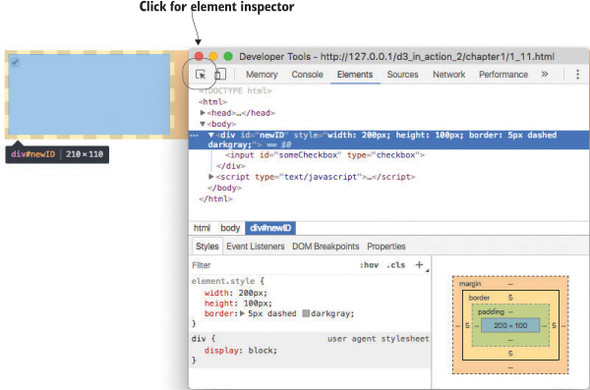

Examining the DOM in the console

Navigate to d3ia.html, and you can get exposure to how D3 works. The page isn’t too impressive, with only a single, black-outlined rectangle. You could modify the look and feel of this web page by updating d3ia.html, but you’ll find that it’s easy to modify the page by using your web browser’s developer console. This is useful for testing changes to classes or elements before implementing them in your code. Open the developer console, and you’ll have two useful screens, shown in figures 1.11 and 1.12, which we’ll go back to again and again.

Figure 1.11. The developer tools in Chrome place the JavaScript console on the rightmost tab, labeled Console, with the element inspector available using the arrow in a rectangle (circled above) on the top left or by browsing the DOM in the Elements tab.

Figure 1.12. You can run JavaScript code in the console and call global variables or declare new ones as necessary. Any code you write in the console and changes made to the web page are lost as soon as you reload the page.

Note

You’ll see the console in this first chapter, but in chapter 2, once you’re familiar with it, I’ll show only the output.

The element inspector allows you to look at the elements that make up your web page by navigating through the DOM (represented as nested text, where each child element is shown indented). You can also select an element onscreen graphically, typically represented as a magnifying glass or cursor icon.

The other screen you’ll want to use quite often is the console (figure 1.12), which allows you to write and run JavaScript code right on your web page. The developer tools have other valuable features, such as setting breakpoints and the ability to inspect network calls, but we’re going to focus on using the console to change elements and run code.

The examples in this book use Google Chrome and its developer console, but you could use Safari’s or Firefox’s developer tools with the same functionality and slightly different look-and-feel, or use your code editor and refresh the page. You can see and manipulate DOM elements such as <div> or <body> by clicking the element inspector or looking at the DOM as represented in HTML. You can click one of these elements and change its appearance by modifying it in the console.

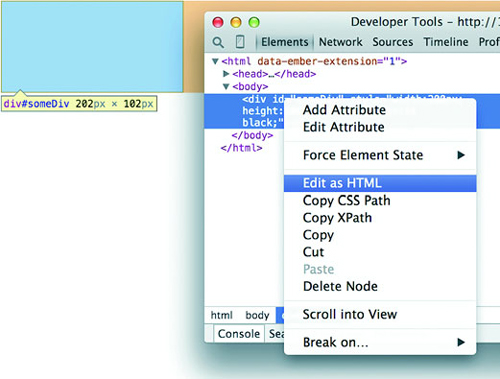

You can even delete elements in the console. Give it a try: select the div either in the DOM or visually and press Delete. Now your web page is lonely. Press Refresh so your page reloads the HTML and your div comes back. You can adjust the size and color of your div by adding new styles or changing the existing one, so you can increase the width of the border and make it dashed by changing the border style to Black 5px Dashed. You can add content to the div in the form of other elements, or you can add text by right-clicking on the element and selecting Edit as HTML, as shown in figures 1.13 and 1.14.

Figure 1.13. Rather than adding or modifying individual styles and attributes, you can rewrite the HTML code as you would in a text editor. As with any changes, these only last until you reload the page.

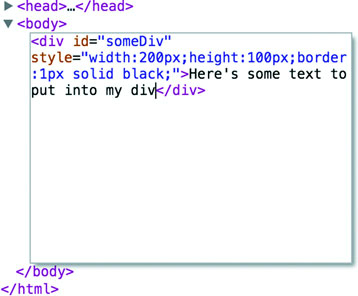

Figure 1.14. Changing the content of a DOM element is as simple as adding text between the opening and ending brackets of the element.

You can then write whatever you like in between the opening and closing HTML.

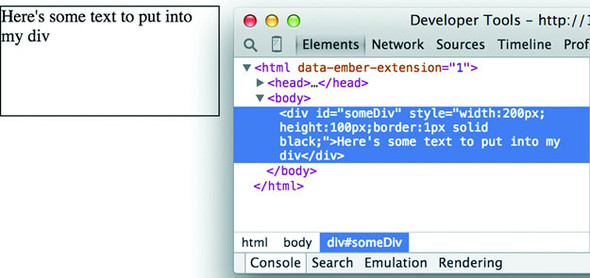

Any changes you make, regardless of whether they’re well structured or not, will be reflected on the web page. In figure 1.15 you see the results of modifying the HTML, which is rendered immediately on your page.

Figure 1.15. The page is updated as soon as you finish making your changes. Writing HTML manually in this way is only useful for planning how you might want to dynamically update the content.

In this way, you could slowly and painstakingly create a web page in the console. We’re not going to do that. Instead, we’ll use D3 to create elements on the fly with size, position, shape, and content based on our data.

1.3.2. Coding in the console

You’ll do most your coding in the IDE or text editor of your choice, but one of the great things about web development is that you can test JavaScript code changes by using your console. Later you’ll focus on writing JavaScript, but for now, to demonstrate how the console works, copy the following code into your console and press Enter:

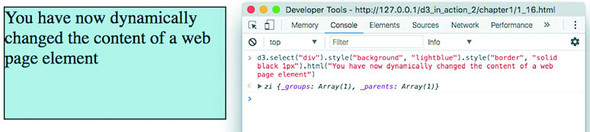

d3.select("div").style("background", "lightblue").style("border", "solid

black 1px").html("You have now dynamically changed the content of a web page

element");

You should see the effect shown in figure 1.16.

Figure 1.16. The D3 select syntax modifies style using the .style() function, and traditional HTML content using the .html() function.

You’ll see a few more uses of traditional HTML elements in this chapter, and then again in chapter 3, but then you won’t see traditional DOM elements again in great detail. You can use D3 to create complex, data-driven spreadsheets and galleries using <div>, <table>, and <select> elements, but that’s not a common use case in the real world. If all D3 could do was select HTML elements and change their style and content like this, then it wouldn’t be that useful for data visualization. To do more, we have to move away from traditional HTML and focus on a special type of element in the DOM: SVG.

1.3.3. SVG

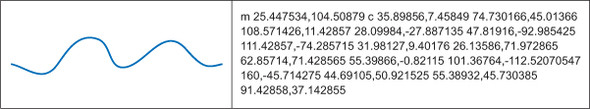

A major value of HTML5 is the integrated support for Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG). SVG allows for simple mathematical representation of images that scale and are amenable to animation and interaction. Part of the attractiveness of D3 is that it provides an abstraction layer for drawing SVG, because SVG drawing can be a little confusing. SVG drawing instructions for complex shapes, known as <path> elements, are written a bit like the old LOGO programming language. You start at a point on a canvas and draw a line from that point to another. If you want it to curve, you can give the SVG drawing code coordinates on which to make that curve. If you want to draw the line on the left, you’d create a <path> element in an <svg> canvas element in your web page, and all those drawing instructions (that’s what they look like on the left of figure 1.17) go into the d attribute of that <path> element.

Figure 1.17. The commands to draw an SVG path (right) and the resulting graphic (left)

But you’d almost never want to create SVG by manually writing drawing instructions like this. Instead, you’ll want to use D3 to do the drawing with a variety of helper functions, or rely on other SVG elements that represent simple shapes (known as geometric or graphical primitives) using more readable attributes. You’ll start doing that in chapter 4, where you’ll use d3.svg.line and d3.svg.area to create line and area charts. For now, you’ll update d3ia.html to look like the following listing, which includes the necessary code for displaying SVG, as well as examples of the various shapes you might use.

Listing 1.2. A sample web page with SVG elements

<!doctype html>

<html>

<script src="d3.v4.min.js">

</script>

<body>

<div id="infovizDiv">

<svg style="width:500px;height:500px;border:1px lightgray solid;">

<path d="M 10,60 40,30 50,50 60,30 70,80"

style="fill:black;stroke:gray;stroke-width:4px;" />

<polygon style="fill:gray;"

points="80,400 120,400 160,440 120,480 60,460" />

<g>

<line x1="200" y1="100" x2="450" y2="225"

style="stroke:black;stroke-width:2px;"/>

<circle cy="100" cx="200" r="30"/>

<rect x="410" y="200" width="100" height="50"

style="fill:pink;stroke:black;stroke-width:1px;" />

</g>

</svg>

</div>

</body>

</html>

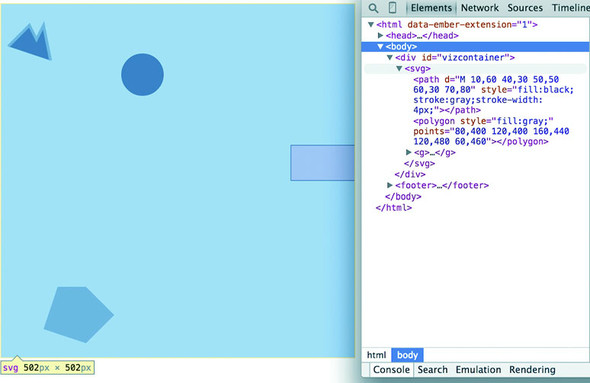

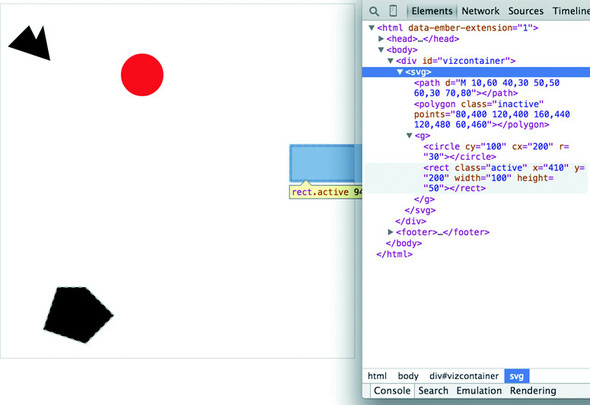

You can inspect the elements like you would the traditional elements we looked at earlier, as you can see in figure 1.18, and you can manipulate these elements using traditional JavaScript selectors like document.getElementById or with D3, removing them or changing the style like so.

d3.select("circle").remove() 1

d3.select("rect").style("fill", "purple") 2

- 1 Deletes the circle

- 2 Changes the rectangle color to purple

Figure 1.18. Inspecting the DOM of a web page with an SVG canvas reveals the nested graphical elements as well as the style and attributes that determine their position. Notice that the circle and rectangle exist as child elements of a group.

Now refresh your page and let’s look at the new elements. You’re familiar with divs, and it’s useful to put an SVG canvas in a div so you can access the parent container for layout and styling. Let’s look at each of the elements we’ve added.

<svg> container

This is your canvas on which everything is drawn. The top-left corner is 0,0, and the canvas clips anything drawn beyond its defined height and width of 500,500 (the rectangle in our example). An <svg> element can be styled with CSS to have different borders and backgrounds. The <svg> element can also be dynamically resized using the viewBox attribute, which is more complex and beyond the scope of the overview here.

You can use CSS (which we’ll touch on later in this chapter) to style your SVG canvas or use D3 to add inline styles like this:

d3.select("svg").style("background", "darkgray"); 1

- 1 Infoviz is always cooler on a dark background

Note

The x-axis is drawn left to right, but the y-axis is drawn top-to-bottom, so you’ll see that the circle is set 200 pixels to the right and 100 pixels down.

There’s a second mode of drawing available with HTML5 using <canvas> elements to draw bitmaps. We won’t go into detail here, but you’ll see this method used in chapter 11 for its rendering performance. The <canvas> element creates static graphics drawn in a manner similar to SVG that can then be saved as images. Here are three main reasons to use canvas:

- Creating static images— You can draw your data visualization with canvas to save views as snapshots for thumbnail and gallery views.

- Large amounts of data— SVG creates individual elements in the DOM, and although this is great for attaching events and styling, it can overwhelm a browser and cause significant slowdown (this is what we’ll use canvas for in chapter 11).

WebGL—The <canvas> element allows you to use WebGL to draw, so that you can create 3D objects. You can also create 3D objects like globes and polyhedrons using SVG, which we’ll get into a bit in chapter 8 as we examine geospatial information visualization.

<circle>, <rect>, <line>, <polygon> shape primitives

SVG provides a set of common shapes, each of which has attributes that determine their size and position to make them easier to deal with than the generic d attribute you saw earlier. These attributes vary depending on the element you’re dealing with, so that <rect> has x and y attributes that determine the shape’s top-left corner, as well as height and width attributes that determine its overall form. In comparison, the <circle> element has cx and cy attributes that determine the center of the circle, and an r attribute that determines the radius of the circle. The <line> element has x1 and y1 attributes that determine the starting point of the line and x2 and y2 attributes that determine its end point. Other simple shapes are similar to these, such as the <ellipse>, and other more complex shapes, like the <polygon> with a points attribute that holds a set of comma-separated xy coordinates, in clockwise order, determine the area bounded by the polygon.

Accomplished artists can draw anything with vector graphics, but you’re probably not looking at D3 because you’re an artist. Instead, you’re dealing with graphics and have more pragmatic goals in mind. From that perspective, it’s important to understand the concept of geometric primitives (also known as graphical primitives). Geometric primitives are simple shapes such as points, lines, circles, and rectangles. These shapes, which can be combined to make more complex graphics, are particularly useful for visually displaying information.

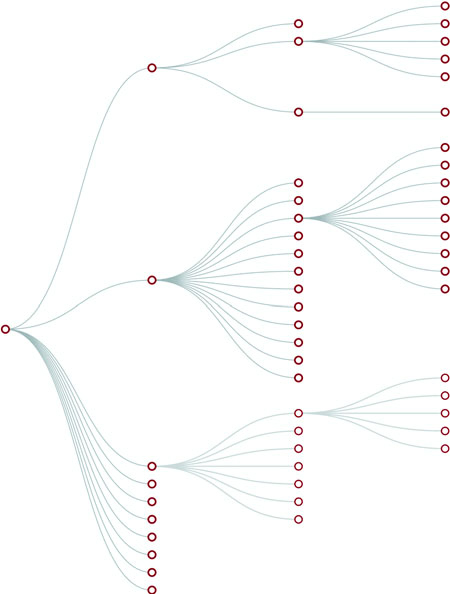

Primitives are also useful for understanding complex information visualizations that you see out in the real world. Dendrograms, like the one shown in figure 1.20, are far less intimidating when you realize they’re only circles and lines. Interactive timelines are easier to understand and create when you think of them as collections of rectangles and points. Even geographic data, which primarily comes in the form of polygons, points, and lines, is less confusing when you break it down into its most basic graphical structures.

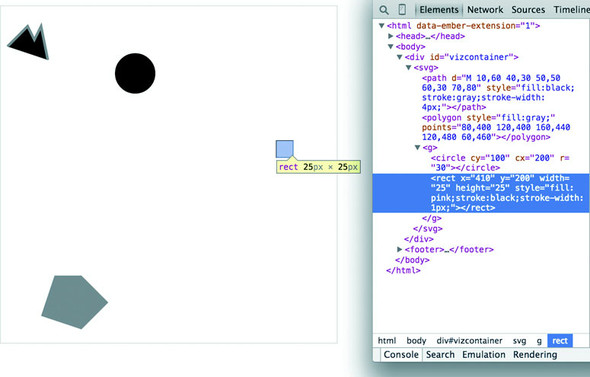

Each of these attributes can be hand-edited in HTML to adjust its size, form, and position. Open your element inspector and click the <rect>. Change its width to 25 and its height to 25, as shown in figure 1.19.

Figure 1.19. Modifying the height and width attributes of a <rect> element changes the appearance of that element. Inspecting the element also shows how the stroke adds to the computed size of the element.

Now you’ve learned why there’s no SVG <square>. The color, stroke, and transparency of any shape can be changed by adjusting the style of the shape, with fill determining the color of the area of the shape and stroke, stroke-width, stroke-dasharray determining its outline.

Notice, though, that the inspected element has a measurement of 27 px x 27 px. That’s because the 1-px stroke is drawn on the outside of the shape. That makes sense, once you know the rule, but if you change the stroke-width to 2px it will still be 27 px x 27 px. That’s because the stroke is drawn evenly over the inside and outside borders, as seen in figure 1.20. This may not seem too big a deal, but it’s something to remember when you’re trying to line up your shapes later.

Figure 1.20. The same 25 x 25 <rect> with no, 1-px, 2-px, 3-px, 4-px, and 5-px strokes. Though these are drawn on a retina screen using half-pixels, the second and third report the same width and height (27 px x 27 px) as the fourth and fifth (29 px x 29 px).

Change the style parameters of the rectangle to the following:

"fill:purple;stroke-width:5px;stroke:cornflowerblue;"

Congratulations! You’ve now successfully visualized the complex and ambiguous phenomenon known as “ugly.”

<text>

SVG provides the capacity to write text as well as shapes. SVG text, though, doesn’t have the formatting support found in HTML elements, so it’s primarily used for labels. If you do want to do basic formatting, you can nest <tspan> elements in <text>

<g> grouping element

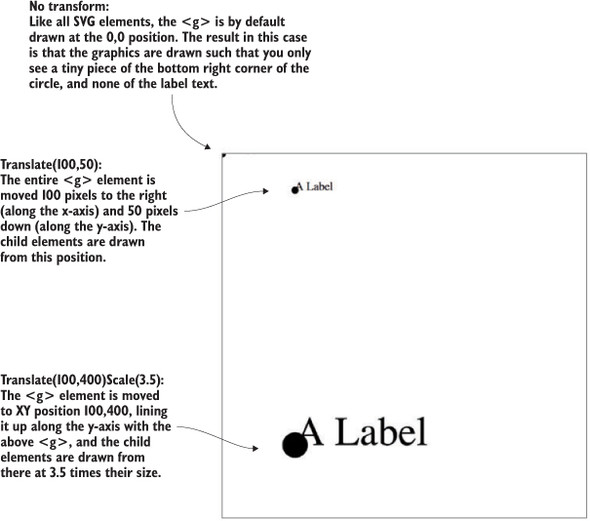

The <g> or group element is distinct from the SVG elements we’ve discussed in that it has no graphical representation and doesn’t exist as a bounded space. Instead, it’s a logical grouping of elements. You’ll want to use <g> elements extensively when creating graphical objects that are made up of several shapes and text. For instance, if you wanted to have a circle with a label above it and move the label and the circle at the same time, then you’d place them inside a <g> element:

<g> <circle r="2"/> <text>This circle's Label</text> </g>

Moving a <g> around your canvas requires you to adjust the transform attribute of the <g> element. The transform attribute is more intimidating than the various xy attributes of shapes because it accepts a structured description in text of how you want to transform a shape. One of those structures is translate(), which accepts a pair of coordinates that move the element to the xy position defined by the values in translate (x,y). If you want to move a <g> element 100 pixels to the right and 50 pixels down, then you need to set its transform attribute to transform="translate (100,50)". The transform attribute also accepts a scale() setting so you can change the rendered scale of the shape as you can see in the example in listing 1.3. You can see these settings in action by modifying the previous example with the results shown in figure 1.21.

Figure 1.21. All SVG elements can be affected by the transform attribute, but this is particularly salient when working with <g> elements, which require this approach to adjust their position. The child elements are drawn by using the position of their parent <g> as their relative 0,0 position. The scale() setting in the transform attribute then affects the scale of any of the size and position attributes of the child elements.

Listing 1.3. Grouping SVG elements

<g> <circle r="2"/> <text>This circle's Label</text> </g> <g transform="translate(100,50)"> <circle r="2" /> <text>This circle's Label</text> </g> <g transform="translate(100,400) scale(2.5)"> <circle r="2"/> <text>This circle's Label</text> </g>

<path>

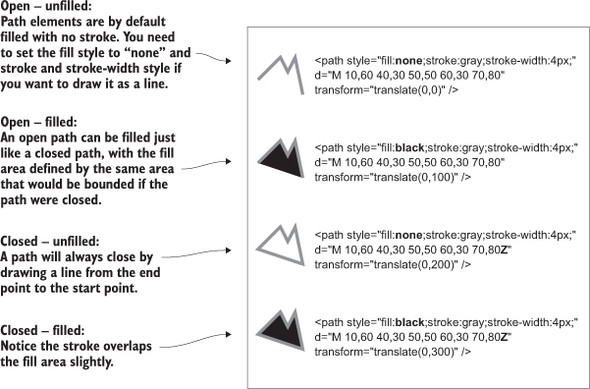

A path is an area determined by its d attribute. Paths can be open or closed, meaning the last point connects to the first if closed and doesn’t if open. The open or closed nature of a path is determined by the absence or presence of the letter Z at the end of the text string in the d attribute. It can still be filled either way. You can see the difference in figure 1.22 (the code for which is shown in the following listing).

Figure 1.22. Each path shown here uses the same coordinates in its d attribute, with the only differences between them being the presence or absence of the letter Z at the end of the text string defining the d attribute, the settings for fill and stroke, and the position via the transform attribute.

Listing 1.4. SVG path fill and closing

<path style="fill:none;stroke:gray;stroke-width:4px;"

d="M 10,60 40,30 50,50 60,30 70,80" transform="translate(0,0)" />

<path style="fill:black;stroke:gray;stroke-width:4px;"

d="M 10,60 40,30 50,50 60,30 70,80" transform="translate(0,100)" />

<path style="fill:none;stroke:gray;stroke-width:4px;"

d="M 10,60 40,30 50,50 60,30 70,80Z" transform="translate(0,200)" />

<path style="fill:black;stroke:gray;stroke-width:4px;"

d="M 10,60 40,30 50,50 60,30 70,80Z" transform="translate(0,300)" />

Although sometimes you may want to write that d attribute yourself, it’s more likely that your experience crafting SVG will come in one of three ways: using geometric primitives such as circles, rectangles, or polygons, drawing SVG using a vector graphics editor like Adobe Illustrator or Inkscape, or drawing SVG parametrically using handwritten constructors or built-in constructors in D3. Most of this book focuses on using D3 to create SVG, but don’t overlook the possibility of creating SVG using an external application or another library and then manipulating them using D3, like we’ll do using d3.html in chapter 3.

1.3.4. CSS

CSS are used to style the elements in the DOM. A style sheet can exist as a separate .css file that you include in your HTML page or can be embedded directly in the HTML page. Style sheets refer to an ID, class, or type of element and determine the appearance of that element. The terminology used to define the style is a CSS selector and is the same type of selector used in the d3.select() syntax. You can set inline styles (that are applied to only a single element) by using d3.select(#someElement).style(opacity, .5) to set the opacity of an element to 50%. Let’s update your d3ia.html to include a style sheet, as shown in the following listing.

Listing 1.5. A sample web page with a style sheet

<!doctype html>

<html>

<script src="d3.v4.min.js"></script> 1

<style>

.inactive, .tentative { 2

stroke: darkgray;

stroke-width: 2px;

stroke-dasharray: 5 5;

}

.tentative {

opacity: .5;

}

.active {

stroke: black;

stroke-width: 4px;

stroke-dasharray: 1;

}

circle {

fill: red;

}

rect {

fill: darkgray;

}

</style>

<body> 3

<div id="infovizDiv">

<svg style="width:500px;height:500px;border:1px lightgray solid;">

<path d="M 10,60 40,30 50,50 60,30 70,80" />

<polygon class="inactive" points="80,400 120,400 160,440 120,480 60,460" />

<g>

<circle class="active tentative" cy="100" cx="200" r="30"/>

<rect class="active" x="410" y="200" width="100" height="50" />

</g>

</svg>

</div>

</body>

</html>

- 1 The reference to the D3 library so we can use that code in our app

- 2 CSS rules for our elements

- 3 The fixed content of our page (we’ll work on adding more content dynamically later)

The results stack on each other, so when you examine the rectangle element, as shown in figure 1.23, you see that its style is set by the reference to rect in the style sheet as well as the class attribute of active.

Figure 1.23. Examining an SVG rectangle in the console shows that it inherits its fill style from the CSS style applied to <rect> types and its stroke style from the .active class.

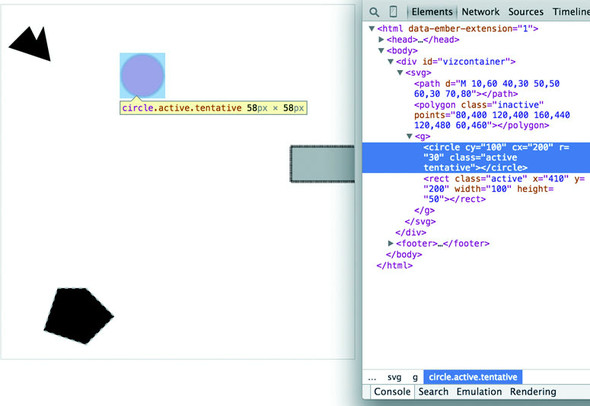

Style sheets can also refer to a state of the element, so with :hover you can change the way an element looks when the user mouses over that element. You can learn about other complex CSS selectors in more detail in a book devoted to that subject. For this book, we’ll focus mostly on using CSS classes and IDs for selection and to change style. The most useful way to do this is to have CSS classes associated with particular stylistic changes and then change the class of an element. You can change the class of an element, which is an attribute of an element, by selecting and modifying the class attribute. The circle shown in figure 1.24 is affected by two overlapping classes: .active and .tentative.

Figure 1.24. The SVG circle has its fill value set by its type in the style sheet, with its opacity set by its membership in the .tentative class and its stroke set by its membership in the .active class. Notice that the stroke settings from the .tentative class are overwritten by the stroke settings in the later declared .active class.

In listing 1.5 we see a couple of possibly overlapping classes, with tentative, active, and inactive all applying different style changes to your shape (such as the highlighted circle in figure 1.23). When an element needs only be assigned to one of these classes, you can overwrite the class attribute entirely:

d3.select("circle").attr("class", "tentative");

The results, as shown in figure 1.25, are what we’d expect. This overwrites the entire class attribute to the value you set. But elements can have multiple classes, and sometimes an element is both active and tentative or inactive and tentative, so let’s reload the page and take advantage of the helper function d3.classed(), which allows you to add or remove a class from the classes in an element.

d3.select("circle").classed("active", true);

Figure 1.25. An SVG circle with fill style determined by its type and its opacity and stroke settings determined by its membership in the tentative class

By using .classed(), you don’t overwrite the existing attribute, but rather append or remove the named class from the list. You can see the results of two classes with conflicting styles defined. The active style overwrites the tentative style because it occurs later in the style sheet. Another rule to remember is that more specific rules overwrite more general rules. There’s more to CSS, but this book won’t go into that.

By defining style in your style sheet and changing appearance based on class membership, you create code that’s more maintainable and readable. You’ll need to use inline styles to set the graphical appearance of a set of elements to a variety of different values, for example, changing the fill color to correspond to a color ramp based on the data bound to that set of elements. You’ll see that functionality in action later when you deal with bound data. But as a general rule, setting inline styles should only be used when you can’t use traditional classes and states defined in a style sheet.

1.3.5. JavaScript

D3, like many information visualization libraries in JavaScript, provides functions to abstract the process of creating and modifying web page elements. On top of that, it provides mechanisms to link data and web page elements in a way that makes the drawing and updating of these SVG elements reusable and maintainable. But these mechanisms are also applicable to more traditional HTML elements such as paragraphs and divs.

When writing JavaScript with D3, you should familiarize yourself with two subjects: method chaining and arrays.

Method chaining

D3 examples, like many examples written in JavaScript, use method chaining extensively. Method chaining, also known as function chaining, is facilitated by returning the method itself with the successful completion of functions associated with a method. One way to think of method chaining is to think of how we talk and refer to each other. Imagine you were talking to someone at a party, and you asked about another guest:

“What’s her name?”

“Her name is Lindsay.”

“Where does she work?”

“She works at Tesla.”

“Where does she live?”

“She lives in Cupertino.”

“Does she have any children?”

“Yes, she has a daughter.”

“What’s her name?”

Do you think the answer to that last question would be “Lindsay”? Of course not. You’d expect the answer to refer to Lindsay’s daughter, even though all the previous questions referred to Lindsay. Method chaining is like that. It returns the same function as long as you use getter and setter methods of that function and returns the new function when you call a method that creates something new. Method chaining is used a lot in D3 examples, which means you’ll see something like this written on one line or formatted (but functionally identical) to something written on multiple lines:

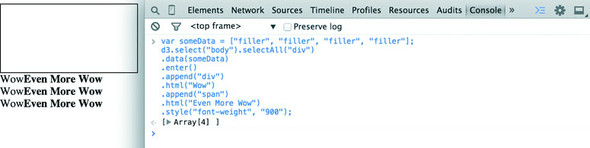

d3.selectAll("div").data(someData).enter().append("div").html("Wow").append("span").html("Even More Wow").style("font-weight", "900");

That line is the same as the following code. The only change is in the use of line breaks, which JavaScript ignores:

d3.selectAll("div") 1

.data(someData) 2

.enter() 3

.append("div") 4

.html("Wow") 5

.append("span") 6

.html("Even More Wow") 7

.style("font-weight", "900"); 8

- 1 Returns a selection, an object with various functions available

- 2 Sets the data on the selection and returns the selection

- 3 Returns the selection.enter() object

- 4 Sets .append() behavior on the selection.enter object and returns the selection.enter object

- 5 Sets .html() for the selection.enter object and returns the selection.enter object

- 6 Sets the append() behavior on the selection.enter object and returns the enter.append object

- 7 Sets the html() for the enter.append object and returns the enter.append object

- 8 Sets the font-weight style on the enter.append object and returns the enter.append object

You could write each line separately, declaring the different variables as you go, and achieve the same effect. That might make more sense if you haven’t been exposed to method chaining before:

var function1 = d3.selectAll("div");

var function1withData = function1.data(someData);

var function2 = function1withData.enter();

var function3 = function2.append("div");

function3.html("Wow");

var function4 = function3.append("span");

function4.html("Even More Wow");

function4.style("font-weight", "900");

You can see this when you run the code in your console. This is the first time you’ve used the .data() function, which along with .select() is at the core of developing with D3. When you use .data(array), you bind each element in your selection to each item in an array (if you don’t pass anything to .data() you get back the items bound to your selection). When binding data, if you have more items in your array than elements in your selection, then you can use the .enter() function to define what to do with each extra element. In the previous function, you select all the <div> elements in the <body> and the .enter() function tells D3 to .append() a new div when there are more elements in the array than elements in the selection. Given that your d3ia.html page already has one div, if you bind an array with more than one value, D3 appends, or adds, a div for each value in the array beyond the first.

A corresponding .exit() function defines how to respond when an array has fewer values than a selection. For now, you’ll run the code as it appears in the examples, and in later chapters we’ll get into much more detail on the way selections and binding work.

With this example, you’re not doing anything with the data in the array and only creating elements based on the size of the array (one <div> for each element in the array). This example assumes that you already have a <div> in your HTML with a gray border (as seen in figure 1.25). Here’s the HTML that would get that done:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<script src="d3.v4.min.js"></script>

<style>

#borderdiv {

width: 200px;

height: 50px;

border: 1px solid gray;

}

</style>

<body>

<div id="borderdiv"></div>

</body>

</html>

For this to work, you need to give someData a value. With that in place, you can run your code:

var someData = ["filler", "filler", "filler", "filler"];

d3.select("body").selectAll("div")

.data(someData)

.enter()

.append("div")

.html("Wow")

.append("span")

.html("Even More Wow")

.style("font-weight", "900");

The result, as shown in figure 1.26, is the addition of three lines of text. It might surprise you that this code is three lines, given that the array has four values. Although the data was bound to the existing <div> element on the page, the actions that changed the contents were only applied to the .enter() function. This means they were only applied to the newly created <div> elements that were “entering” the DOM for the first time.

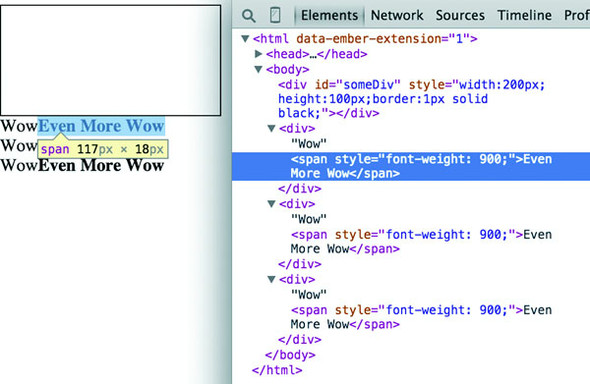

Figure 1.26. By binding an array of four values to a selection of <div> elements on the page, the .enter() function created three new <div> elements to reflect the size mismatch between the data array and the selection.

When you inspect the DOM, as shown in figure 1.27, you see that the method chaining operated in the manner previously described. A <div> was added, and its HTML content was set to Wow. A <span> element with a different style was appended to the <div>, and its HTML content was set to Even More Wow. There’s more you can do, but first you need to examine the array object you’re binding and focus on JavaScript arrays and array functions.

Figure 1.27. Inspecting the DOM shows that the new <div> elements have been created with unformatted content followed by the child <span> element with style and content set by your code.

Arrays and array functions

D3 is all about arrays, and so it’s important to understand the structure of arrays and the options available to you to prepare those arrays for binding to data. Your array might be an array of string or number literals, such as this:

someNumbers = [17, 82, 9, 500, 40]; someColors = ["blue", "red", "chartreuse", "orange"];

Or it may be an array of JavaScript objects, which will become more common as you do more interesting things with D3:

somePeople = [{name: "Peter", age: 27}, {name: "Sulayman", age: 24},

{name: "K.C.", age: 49}];

One example of a useful array function is .filter(), which returns an array whose elements satisfy a test you provide. For instance, here’s how to create an array out of someNumbers that had values greater than 40:

someNumbers.filter(function(d) {return d >= 40});

Likewise, here’s how you could create an array out of someColors with names shorter than five letters:

someColors.filter(function(d) {return d.length < 5});

The function .filter() is a method of an array and accepts a function that iterates through the array with the variable you’ve named. In this function, you name that variable d, and the function runs a test on each value by testing on d. When that test evaluates true, the element is kept in our new array.

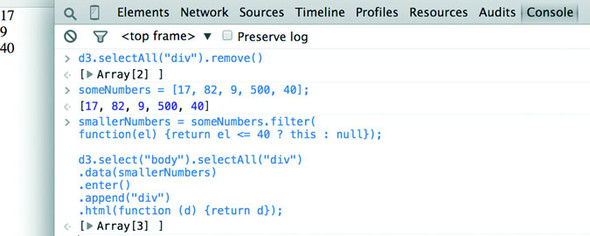

The result of this .filter() function, which you can see in figure 1.28, returns either the element or nothing (depending on if it satisfies the test), building a new array consisting only of the elements that do:

Figure 1.28. Running JavaScript in the console allows you to test your code. Here you’ve created a new array called smallerNumbers that consists of only three values, which you can then use as your data in a selection to update and create new elements.

smallerNumbers = someNumbers.filter(

function(el) {return d <= 40});

d3.select("body").selectAll("div")

.data(smallerNumbers)

.enter()

.append("div")

.html(function (d) {return d});

The resulting code creates two new divs from your three-value array smallerNumbers. (Remember that one div already exists, and so the .enter() function doesn’t trigger even though data is bound to that existing div.) The contents of the div are the values in your array. This is done through an anonymous function (sometimes referred to in D3 examples as an accessor) in your .html() function and is another key aspect of D3. Any anonymous function called when setting the .style(), .attr(), .property(), .html(), or other function of a selection can provide you with the data bound to that selection. As you explore examples, you’ll see this function deployed again and again:

.style("background", function(d) {return d})

.attr("cx", function(d,i) {return i})

.html(function(d) {return d})

In every case, the first variable (typically represented with the letter d, but you can declare it as whatever you want) contains the data value bound to that element, and the second variable returns the array position (known as an index, hence the variable name i) of the value bound to that element. This may seem a bit strange, but you’ll get used to it as you see it used in a variety of ways in the upcoming chapters.

JavaScript has many other array functions, and you can do much more than I’ve covered here, but that’s the subject of several other books. It’s time to look at the kinds of data you’ll work with.

1.3.6. ES2015 and Node

JavaScript has seen some major changes in the last couple years. The two biggest trends in modern JS are the rise of node.js and the broad implementation among browsers and through transpilers for EcmaScript 6 (Known as ES2015). What that means for you is that with Node servers you can write code that runs in the front end or on the server without any changes. This is known as isomorphic or universal Java-Script. We’re not going to do that in this book, but it provides incredible flexibility for JavaScript applications.

For this book, the major Node technology that we want to be aware of is NPM, or Node Package Manager. NPM allows you to install “modules” or small libraries of JS code for use in your applications. You don’t have to include a bunch of <script> tag references to individual files and, if the module has been built so that it’s not one monolithic structure, you can reduce the amount of code you’re including in your applications.

D3.js version 4, which came out in mid-2016, is structured to take advantage of module importing. Throughout this book, you’ll see examples of using D3 in one of two ways. Either we’ll include the entire D3 file, as we have with examples in this chapter, or we’ll include only the individual parts of D3 that we need, as you’ll see in later examples. For the examples in this book, we’ll mostly see this done with script tags, but remember that if you use NPM in your coding, you can require or import individual D3v4 modules into your code as you need them. There isn’t enough space in this book to get into this in detail but it’s considered more and more to be standard practice in JavaScript development, so you’ll need to be familiar with it.

The import syntax is one new piece of ES2015’s advanced functionality. It also includes support for classes, promises, string templating, spread operators, symbols, and a host of new functionality that JS developers should know if they want to succeed. Because ES2015 isn’t yet fully supported, you’ll need to use a transpiler to transform ES2015 code into ES5 code. I’m not going to include much ES2015 in this book, so that if you’re not yet familiar with ES2015 that won’t stop you from learning D3, but one thing you’ll see are arrow functions, which are a more terse way of writing functions. Instead of

function (d) {return d}

an arrow function would be written as follows:

d => d

The parameter after the arrow is returned unless surrounded by brackets, and arrow functions in their cleaner form can be used anywhere, such as in an array forEach:

someArray.forEach(d => {

console.log(d)

})

|

someArray.forEach(function (d) {

console.log(d)

})

|

One thing to remember with arrow functions is that the context of the function (this) is whatever the context it’s created in. If that sounds arcane, don’t worry about it—the important thing to remember is that when you see examples in this book or online where this is being used in a D3 function, typically as a reference to the HTML node to which data is attached, that you won’t have access to the same this in an arrow function as you would with the older function declaration type.

1.4. Data standards

One reason we have the freedom to make so many amazing kinds of data visualization is because we’ve settled on regular ways of representing different kinds of data. Data can be formatted in a variety of manners for a variety of purposes, but it tends to fall into a few recognizable classes: tabular data, nested data, network data, geographic data, raw data, and objects.

1.4.1. Tabular data

Tabular data appears in columns and rows typically found in a spreadsheet or a table in a database. Although you invariably end up creating arrays of objects in D3, it’s often more efficient and easier to pull in data in tabular format. Tabular data is delimited with a particular character, and that delimiter determines its format. You can have Comma-Separated Values (CSV), where the delimiter is a comma, or tab-delimited values, or a semicolon or a pipe symbol acting as the delimiter. For instance, you may have a spreadsheet of user information that includes age and salary. If you export it in a delimited form, it will look like table 1.1. Here a dataset stores name, age, and salary of two people using commas, spaces, or the bar symbol to delimit the different fields.

D3 provides three different functions to pull in tabular data: d3.csv(), d3.tsv(), and d3.dsv(). The only difference between them is that d3.csv() is built for comma-delimited files, d3.tsv() is built for tab-delimited files, and d3.dsv() allows you to declare the delimiter. You’ll see them in action throughout the book.

Table 1.1. Delimited data can be expressed in different forms

|

Name Age Salary |

Name|Age|Salary |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1.1.1 d3.csv | 1.1.2 d3.tsv | 1.1.3 d3.dsv |

| 1.1.4 Sal,34,50000 | 1.1.5 Sal 34 50000 | 1.1.6 Sal|34|50000 |

| 1.1.7 Nan,22,75000 | 1.1.8 Nan 22 75000 | 1.1.9 Nan|22|75000 |

1.4.2. Nested data

Data that’s nested, with objects existing as children of objects recursively, is common. Many of the most intuitive layouts in D3 are based on nested data, which can be represented as trees, such as the one in figure 1.29, or packed in circles or boxes. Data isn’t often output in such a format, and requires a bit of scripting to organize it as such, but the flexibility of this representation is worth the effort. You’ll see hierarchical data in detail in chapter 6.

Figure 1.29. Nested data represents parent/child relationships of objects, typically with each object having an array of child objects, and is represented in a number of forms, such as this dendrogram. Notice that each object can have only one parent.

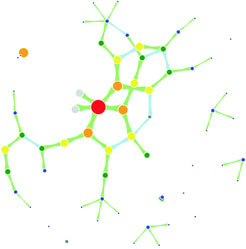

1.4.3. Network data

Networks are everywhere. Whether they’re the raw output of social networking streams, transportation networks, or a flowchart, networks are a powerful method of delivering an understanding of complex systems. Networks are often represented as node-link diagrams, as shown in figure 1.30. Like geographic data, network data has many standards, but this text focuses only on two forms: node/edge lists and connected arrays. Network data can also be easily transformed into these data types by using a freely available network analysis tool like Gephi (available at gephi.org). We’ll examine network data and network data standards when we deal with network visualization in chapter 7.

Figure 1.30. Network data consists of objects and the connections between them. The objects are typically referred to as nodes or vertices, and the connections are referred to as edges or links. Networks are often represented using force-directed algorithms, such as the example here, that arrange the network in such a way as to pull connected nodes toward each other.

1.4.4. Geographic data

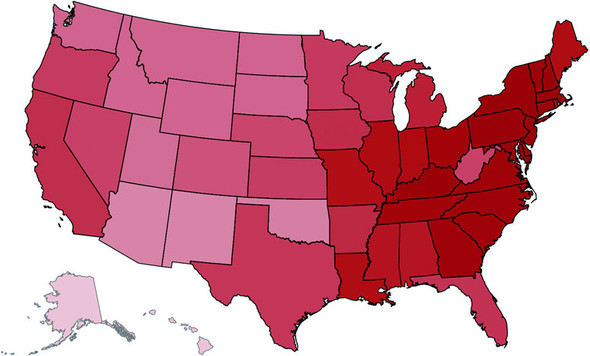

Geographic data refers to locations either as points or shapes, and is used to create the variety of online maps seen on the web today, such as the map of the United States in figure 1.31. The incredible popularity of web mapping means that you can get access to a massive amount of publicly accessible geodata for any project. Geographic data has a few standards, but the focus in this book is on two: the GeoJSON and Topo-JSON standards. Although geodata may come in many forms, readily available geographic information systems (GIS) tools such as Quantum GIS allow developers to transform it into GIS format for ready delivery to the web. We’ll look at geographic data closely in chapter 8.

Figure 1.31. Geographic data stores the spatial geometry of objects, such as states. Each of the states in this image is represented as a separate feature with an array of values indicating its shape. Geographic data can also consist of points, such as for cities, or lines, such as for roads.

1.4.5. Raw data

As you’ll see in chapter 2, everything is data, including images or blocks of text. Although information visualization typically uses shapes encoded by color and size to represent data, sometimes the best way to represent it in D3 is with linear narrative text, an image, or a video. If you develop applications for an audience that needs to understand complex systems, but you consider the manipulation of text or images to be somehow separate from the representation of numerical or categorical data as shapes, then you arbitrarily reduce your capability to communicate. The layouts and formatting used when dealing with text and images, typically tied to older modes of web publication, are possible in D3, and we’ll deal with that throughout this book.

1.4.6. Objects

You’ll use two types of data points with D3: literals and objects. A literal, such as a string literal like Apple or beer or a number literal like 64273 or 5.44, is straightforward. A JavaScript object, or the equivalent JSON (JavaScript Object Notation—a way of expressing data similar to JavaScript objects), isn’t so straightforward, but is something that you need to understand if you plan to do sophisticated data visualization.

Let’s say you have a dataset that consists of individuals from an insurance database, and you need to know how old someone is, whether they’re employed, their name, and their children, if any. A JavaScript object that represents each individual in such a database would be expressed as follows:

{name: "Charlie", age: 55, employed: true, childrenNames: ["Ruth", "Charlie Jr."]}

Each object is surround by braces {}, and has attributes that have a string, number, array, Boolean, or object as their value. You can assign an object to a variable and access its attributes by referring to them, like so:

var person = {name: "Charlie", age: 55, employed: true, childrenNames: ["Ruth", "Charlie Jr."]};

person.name // Charlie

person["name"] // Charlie

person.name = "Charles" // Sets name to Charles

person["name"] = "Charles" // Sets name to Charles

person.age < 65 // true

person.childrenNames // ["Ruth", "Charlie Jr."]

person.childrenNames[0] // "Ruth"

Objects can be stored in arrays and associated with elements using d3.select() syntax. But objects can also be iterated through like arrays using a for loop:

for (x in person) {console.log(x); console.log(person[x]);}

The x in the loop represents each attribute in the person object. Each x will be one of the attributes such as name, age, and so on This allows you to iterate through the attributes using person[x] to show the value of that attribute of the object.

Another way to access keys would be to use Object.keys(person) and then iterate through that array.

If your data is stored as JSON, then you can import it using d3.json(), which you’ll see many times in later chapters. But remember that whenever you use d3.csv(), D3 imports the data as an array of JSON objects. We’ll look at objects more extensively as we use them later.

1.5. Infoviz standards expressed in D3

Information visualization (infoviz) has never been so popular as it is today. The wealth of maps, charts, and complex representations of systems and datasets isn’t present only in the workplace, but also in our entertainment and our everyday lives. With this popularity comes a growing library of classes and subclasses of representation of data and information using visual means, as well as aesthetic rules to promote legibility and comprehension. Your audience, whether the general public, academics, or decision makers, has grown accustomed to what we once considered incredibly abstract and complicated representations of trends in data. This makes libraries such as D3 popular not only among data scientists, but also among journalists, artists, scholars, IT professionals, and even fan communities.

But the wealth of options can seem overwhelming, and the relative ease of modifying a dataset to appear in a streamgraph, treemap, or histogram tends to promote the idea that information visualization is more about style than substance. Fortunately, well-established rules dictate what charts and methods to use for different types of data from different systems. Although I can’t cover every rule in the book, I’ll touch on ones that are useful to consider as we create more complicated information visualizations. Although developers use D3 to revolutionize the use of color and layout, most want to create visual representations of data that support practical concerns. Because D3 is being developed in this mature information visualization environment, it contains numerous helper functions to let developers worry about interface and design rather than color and axes.

Still, to properly deploy information visualization, you should know what to do and what not to do. The best way to learn this is to review the work of established designers and information visualization practitioners, and you need to have a firm understanding not only of your data but of your audience. Although an entire library of works deals with these issues, here are a few that I’ve found useful and can get you oriented on the basics:

- The Visual Display of Quantitative Information Envisioning Information, Edward Tufte

- Designing for Information, Isabel Meirelles

- Pattern Recognition, Christian Swinehart

- Visualization Analysis and Design, Tamara Munzner

These are by no means the only texts for learning data visualization, but I’ve found them useful for getting started. You should pare down and establish fundamental, even basic, data visualization practices that clearly represent the trends that are salient to your audience. When in doubt, simplify—it’s often better to present a histogram than a streamgraph, or a hierarchical network layout (like a dendrogram) than a force-directed one. The more visually complex methods of displaying data tend to inspire more excitement, but can also lead an audience to see what they want to see or focus on the aesthetics of the graphics rather than the data.

One of the best pieces of advice when it comes to working in information visualization comes from the practice of writing: “Kill your darlings.” The same way writers may become enamored of certain scenes or characters, you can become enamored of a particularly elegant or sophisticated-looking graphic. Your love of a cool chart or animation can distract you from the goal of communicating the structure and patterns in the data. Remember to save your harshest criticism for your most beloved pieces, because you may find, much to your chagrin, that they’re not as useful and informative as you think they are.

One thing to keep in mind while reading about data visualization is that the literature is often focused on static charts. With D3 you’ll be making interactive and dynamic visualizations and not only static ones. You’ll make a dynamic (or animated) data visualization before you finish this chapter, and using D3 to make a chart interactive is incredibly simple. A few interactive touches can make a visualization not only more readable but significantly more engaging. Users who feel like they’re exploring rather than reading, even if only with a few mouseover events or a simple click to zoom, will find the content of the visualization more compelling than in a static page. But this added complexity requires an investment in learning principles of interface design and user experience. We’ll get into this in more detail in chapter 9.

1.6. Your first D3 app

Throughout this chapter, you’ve seen various lines of code and the effect of those lines of code on the growing d3ia.html sample page you’ve been building. But I’ve avoided explaining the code in too much detail so that you could concentrate on the principles at work in D3. It’s simple to build an application from scratch that uses D3 to create and modify elements. Let’s put it all together and see how it works. First, let’s start with a clean HTML page that doesn’t have any defined styles or existing divs, as shown in the following listing.

Listing 1.6. A simple webpage

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <script src="d3.v4.min.js"></script> </head> <body> </body> </html>

1.6.1. Hello world with divs

We can use D3 as an abstraction layer for adding traditional content to the page. Although we can write JavaScript inside our .html file or in its own .js file, let’s put code in the console and see how it works. Later, we’ll focus on the various commands in more detail for layouts and interfaces. We can get started with a piece of code that uses D3 to write to our web page, as in the next listing.

Listing 1.7. Using d3.select to set style and HTML content

d3.select("body").append("div")

.style("border", "1px black solid")

.html("hello world");

We can adjust the element on the page and give it interactivity with the inclusion of the .on() function, show in the next listing.

Listing 1.8. Using d3.select to set attributes and event listeners

d3.select("div")

.style("background-color", "pink")

.style("font-size", "24px")

.attr("id", "newDiv")

.attr("class", "d3div")

.on("click", () => {console.log("You clicked a div")});

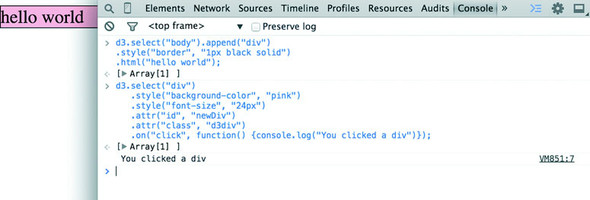

The .on() function allows us to create an event listener for the currently selected element or set of elements. It accepts the variety of events that can happen to an element, such as click, mouseover, mouseout, and so on. If you click your div, you’ll notice that it gives a response in your console, as shown in figure 1.32.

Figure 1.32. Using console.log(), you can test to see if an event is properly firing. Here you create a <div> and assign an onclick event handler using the .on() syntax. When you click that element and fire the event, the action is noted in the console.

1.6.2. Hello World with circles

You didn’t pick up this book to learn how to add divs to a web page, but you likely want to deal with graphics like lines and circles. To append shapes to a page with D3, you need to have an SVG canvas element somewhere in your page’s DOM. You could either add this SVG canvas to the page as you write the HTML, or you could append it using the D3 syntax you’ve learned:

d3.select("body").append("svg");

Let’s adjust our d3ia.html page to start with an SVG canvas, as shown in the following listing.

Listing 1.9. A simple web page with an SVG canvas

<html> <head> <script src="d3.v4.min.js"></script> </head> <body> <div id="vizcontainer"> <svg style="width:500px;height:500px;border:1px lightgray solid;" /> </div> </body> </html>

After we have an SVG canvas on our page, we can append various shapes to it using the same select() and append() syntax we’ve been using in section 1.6.1 for <div> elements, as shown in the following listing.

Listing 1.10. Creating lines and circles with select and append

d3.select("svg")

.append("line")

.attr("x1", 20)

.attr("y1", 20)

.attr("x2",400)

.attr("y2",400)

.style("stroke", "black")

.style("stroke-width","2px");

d3.select("svg")

.append("text")

.attr("x",20)

.attr("y",20)

.text("HELLO");

d3.select("svg")

.append("circle")

.attr("r", 20)

.attr("cx",20)

.attr("cy",20)

.style("fill","red");

d3.select("svg")

.append("circle")

.attr("r", 100)

.attr("cx",400)

.attr("cy",400)

.style("fill","lightblue");

d3.select("svg")

.append("text")

.attr("x",400)

.attr("y",400)

.text("WORLD");

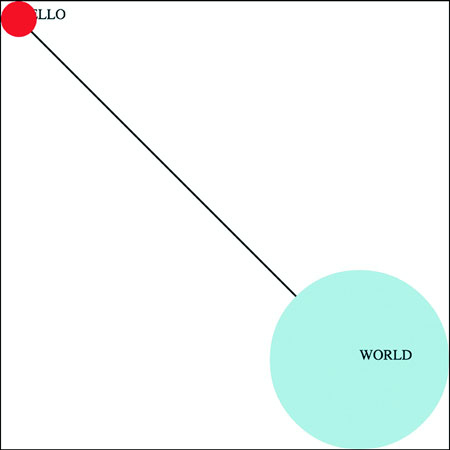

Notice that your circles are drawn over the line, and the text is drawn above or below the circle, depending on the order in which you run your commands, as you can see in figure 1.33. This happened because the draw order of SVG is based on its DOM order. Later you’ll learn methods to adjust that order.

Figure 1.33. The result of running listing 1.10 in the console is the creation of two circles, a line, and two text elements. The order in which these elements are drawn results in the first label covered by the circle drawn later.

1.6.3. A conversation with D3

Writing Hello World with languages is such a common example that I thought we should give the world a chance to respond. Let’s add the same big circle and little circle from before, but this time, when we add text, we’ll include the .style (opacity) setting that makes our text invisible, as shown in the following listing. We’ll also give each text element a .attr(id) setting so that the text near the small circle has an id attribute with the value of a, and the text near the large circle has an id attribute with the value of b.

Listing 1.11. SVG elements with IDs and transparency

d3.select("svg")

.append("circle")

.attr("r", 20)

.attr("cx",20)

.attr("cy",20)

.style("fill","red");

d3.select("svg")

.append("text")

.attr("id", "a")

.attr("x",20)

.attr("y",20)

.style("opacity", 0)

.text("HELLO WORLD");

d3.select("svg")

.append("circle")

.attr("r", 100)

.attr("cx",400)

.attr("cy",400)

.style("fill","lightblue");

d3.select("svg")

.append("text")

.attr("id", "b")

.attr("x",400)

.attr("y",400)

.style("opacity", 0)

.text("Uh, hi.");

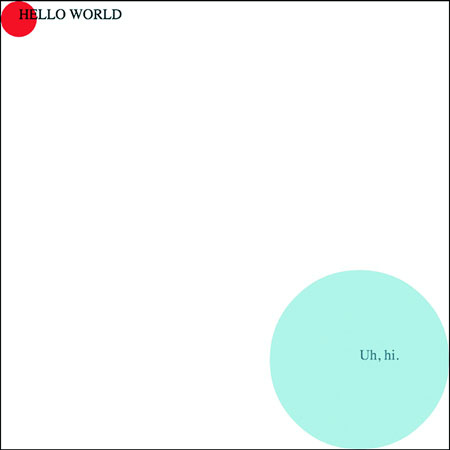

Two circles, no line, and no text. Now you make the text appear using the .transition() method with the .delay() method, and you should have an end state like the one shown in figure 1.34.

Figure 1.34. Transition behavior when associated with a delay results in a pause before the application of the attribute or style.

d3.select("#a").transition().delay(1000).style("opacity", 1);

d3.select("#b").transition().delay(3000).style("opacity", .75);

Congratulations! You’ve made your first dynamic data visualization. The .transition() method indicates that you don’t want your change to be instantaneous. By chaining it with the .delay() method, you indicate how many milliseconds to wait before implementing the style or attribute changes that appear in the chain after that .delay() setting.

We’ll get a bit more ambitious later, but before we finish here, let’s look at another .transition() setting. You can set a .delay() before applying the new style or attribute, but you can also set a .duration() over which the change is applied. The results in your browser should move the shapes in the direction of the arrows in figure 1.35:

Figure 1.35. Transition behavior when associated with position makes the shape graphically move to its new position over the course of the assigned duration. Because you used the same y position for both circles, the first circle moves down and the second circle moves up to the y position you set, which is between the two circles.

d3.selectAll("circle").transition().duration(2000).attr("cy", 200);

The .duration() method, as you can see, adjusts the setting over the course of the amount of time (again, in milliseconds) that you set it for.

That covers the basics of how D3 works and how it’s designed, and these fundamental concepts will surface again and again throughout the following chapters, where you’ll learn more complicated variations on representing and manipulating data.

1.7. Summary

- D3 allows you to create almost any kind of data visualization product you’ve seen in an application or newspaper or online.

- D3 isn’t only for creating the final graphical product; it’s also got functions that allow you to process the data. To get to the more complex data visualization types, like those you see in chapter 6 and later, you’ll have to follow several steps in a process to get to data suitable for graphical display.

- Understanding the DOM, SVG, and CSS is necessary for creating complex data visualization products.

- D3 data binding allows you to create and remove elements on your web page based on data. It also allows you to change the characteristics of those elements—graphical or text content—based on your data.

- Different data types necessitate different approaches to manipulate and visualize them. The main types of data you’ll work with are numerical, hierarchical, topological (network), and textual.

- D3’s built in transitions allow for simple, effective animation right out of the box.

Why learn D3?

— by Jeffrey Heer, associate professor, Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington, former Stanford University PhD advisor of D3 creator Mike Bostock

With a wealth of existing charting libraries and business intelligence tools out there, you might wonder: why learn D3? When you’re first building simple charts and graphs, D3 may feel low-level and verbose, perhaps with some unfamiliar programming constructs to boot! The critical thing to keep in mind is that D3 is not a charting library (though it can be used as such). D3 is a framework for building an expressive range of customized and interactive web-based graphics. D3 provides fundamental building blocks for creating just about any visualization you can imagine. Rather than try to shoehorn your data into a more limited set of application-sanctioned options, by learning D3 you will be able to create interactive web pages tailored to the specifics of your data and use cases.

There are also additional benefits to learning D3. D3 leverages web standards such as the browser Document Object Model (DOM), Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), and Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). These technologies form part of D3’s learning curve but are also invaluable above and beyond D3 itself. Learning D3 thus reaps extra dividends on your time investment, helping you to become a more fluent and seasoned web developer. D3 is also steeped in visualization design concepts and best practices, including facilities for visual encoding, spatial layout, animation, and color design. Rather than limit your consideration to a fixed palette of bar charts, line charts, and scatter plots, the process of learning D3 can help kickstart your journey into the larger world of visualization, introducing you to terms, techniques, and examples that will help you think both more deeply and more creatively about the craft of information visualization.