Copyright © 2019 Amy E. Hodler and Mark Needham. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492047681 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Graphic Algorithms, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the authors have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the authors disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-04761-2

The world is driven by connections—from financial and communication systems to social and biological processes. Revealing the meaning behind these connections drives breakthroughs across industries in areas such as identifying fraud rings and optimizing recommendations to evaluating the strength of a group and predicting cascading failures.

As connectedness continues to accelerate, it’s not surprising that interest in graph algorithms has exploded because they are based on mathematics explicitly developed to gain insights from the relationships between data. Graph analytics can uncover the workings of intricate systems and networks at massive scales— for any organization.

We are passionate about the utility and importance of graph analytics as well as the joy of uncovering the inner workings of complex scenarios. Until recently, adopting graph analytics required significant expertise and determination since tools and integrations were difficult and few knew how to apply graph algorithms to their quandaries. It is our goal to help change this. We wrote this book to help organizations better leverage graph analytics so that they can make new discoveries and develop intelligent solutions faster.

We’ve chosen to focus practical examples on graph algorithms in Apache Spark and the Neo4j platform. However, this guide is helpful for understanding more general graph concepts regardless of what graph technology you use.

This book is written as a practical guide to getting started with graph algorithms for developers and data scientists who have Apache Spark or Neo4j experience. The first two chapters provide an introduction to graph analytics, algorithms, and theory. The third chapter briefly covers the platforms used in this book before we dive into three chapters focusing on classic graph algorithms: pathfinding, centrality, and community detections. We wrap up the book with two chapters showing how graph algorithms are used within workflows: one for general analysis and one for machine learning.

At the beginning of each category of algorithms, there is a reference table to help you quickly jump to the relevant algorithm. For each algorithm, you’ll find:

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant widthUsed for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width boldShows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italicShows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element signifies a general note.

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at https://github.com/oreillymedia/graph_algorithms.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Graph Algorithms by Amy E. Hodler and Mark Needham (O’Reilly). Copyright 2019 Amy E. Hodler and Mark Needham, 978-1-492-04768-1.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Learning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including O’Reilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

We’ve thoroughly enjoyed putting together the material for this book and thank all those who assisted. We’d especially like to thank Michael Hunger for his guidance, Jim Webber for his valuable edits, and Tomaz Bratanic for his keen research. Finally, we greatly appreciate Yelp permitting us to use its rich dataset for powerful examples.

Today’s most pressing data challenges center around relationships, not just tabulating discrete data. Graph technologies and analytics provide powerful tools for connected data that are used in research, social initiatives, and business solutions such as:

As data becomes increasingly interconnected and systems increasingly sophisticated, it’s essential to make use of the rich and evolving relationships within our data.

This chapter provides an introduction to graph analysis and graph algorithms. We’ll start with a brief refresher about the origin of graphs, before introducing graph algorithms and explaining the difference between graph databases and graph processing. We’ll explore the nature of modern data itself, and how the information contained in connections is far more sophisticated than basic statistical methods permit. The chapter will conclude with a look at use cases where graph algorithms can be employed.

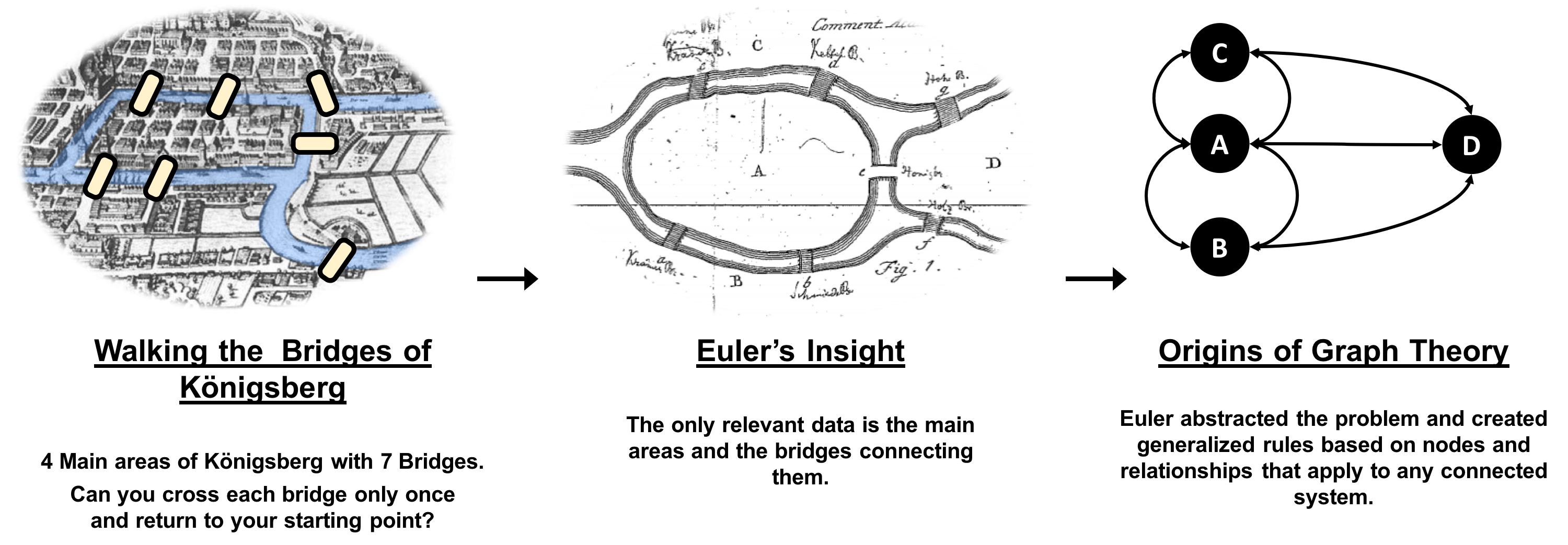

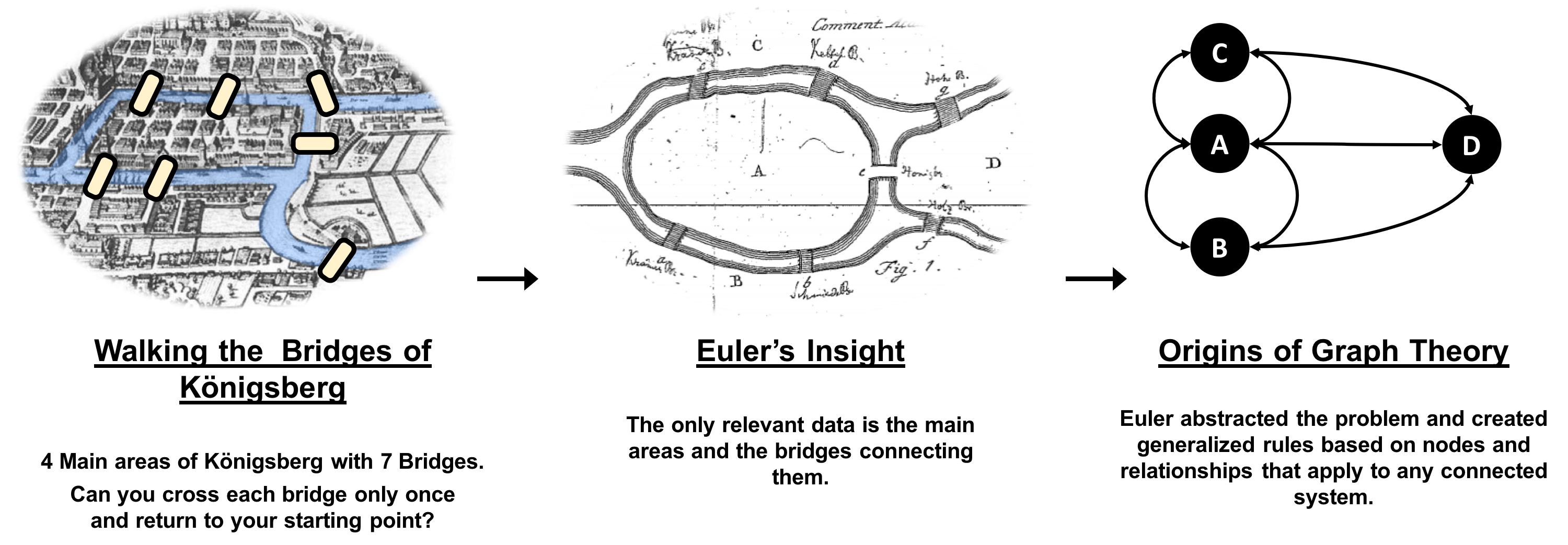

Graphs have a history dating back to 1736 when Leonhard Euler solved the “Seven Bridges of Königsberg” problem. The problem asked whether it was possible to visit all four areas of a city, connected by seven bridges, while only crossing each bridge once. It wasn’t.

With the insight that only the connections themselves were relevant, Euler set the groundwork for graph theory and its mathematics. Figure 1-1 depicts Euler’s progression with one of his original sketches, from the paper ‘Solutio problematis ad geometriam situs pertinentis‘.

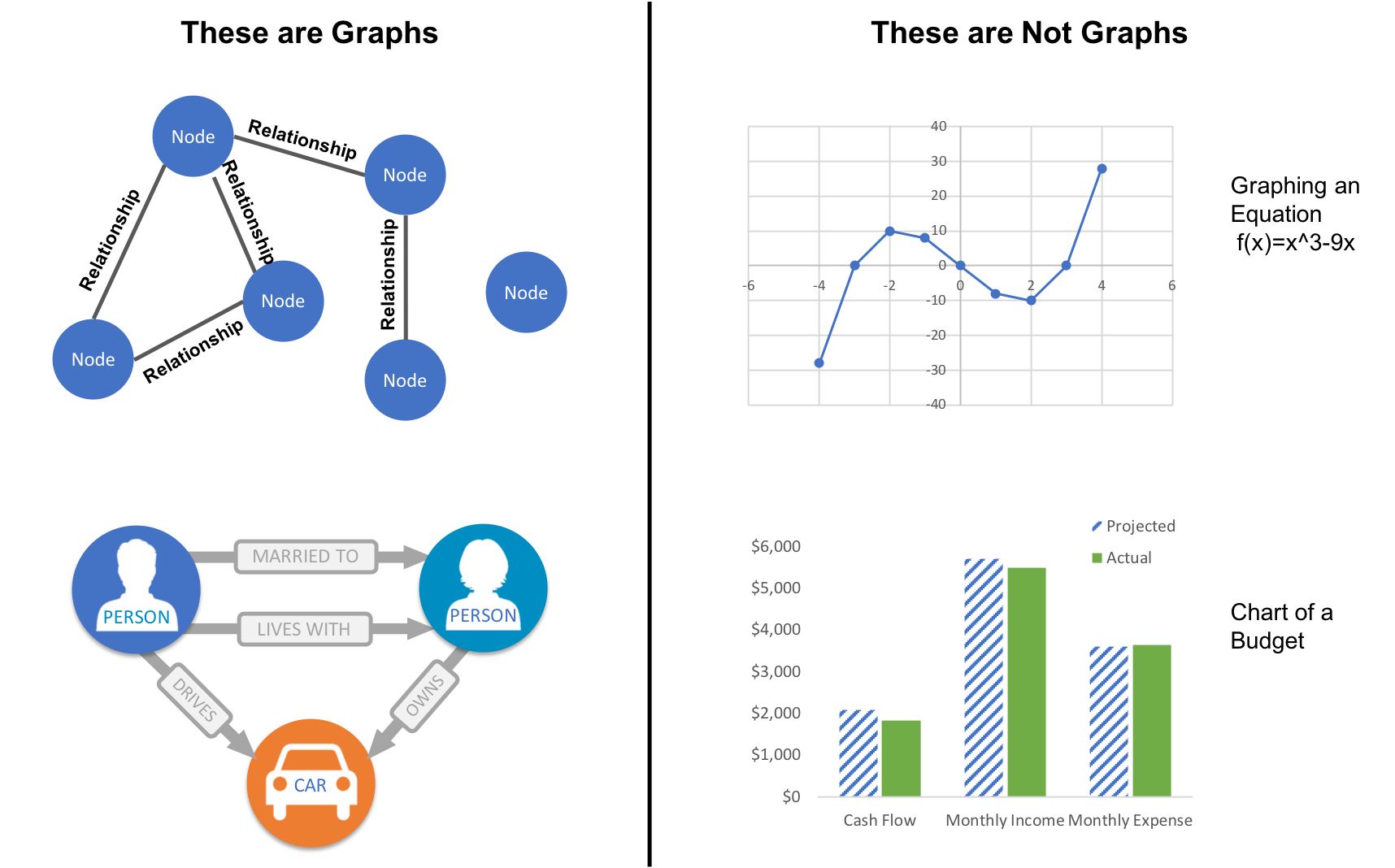

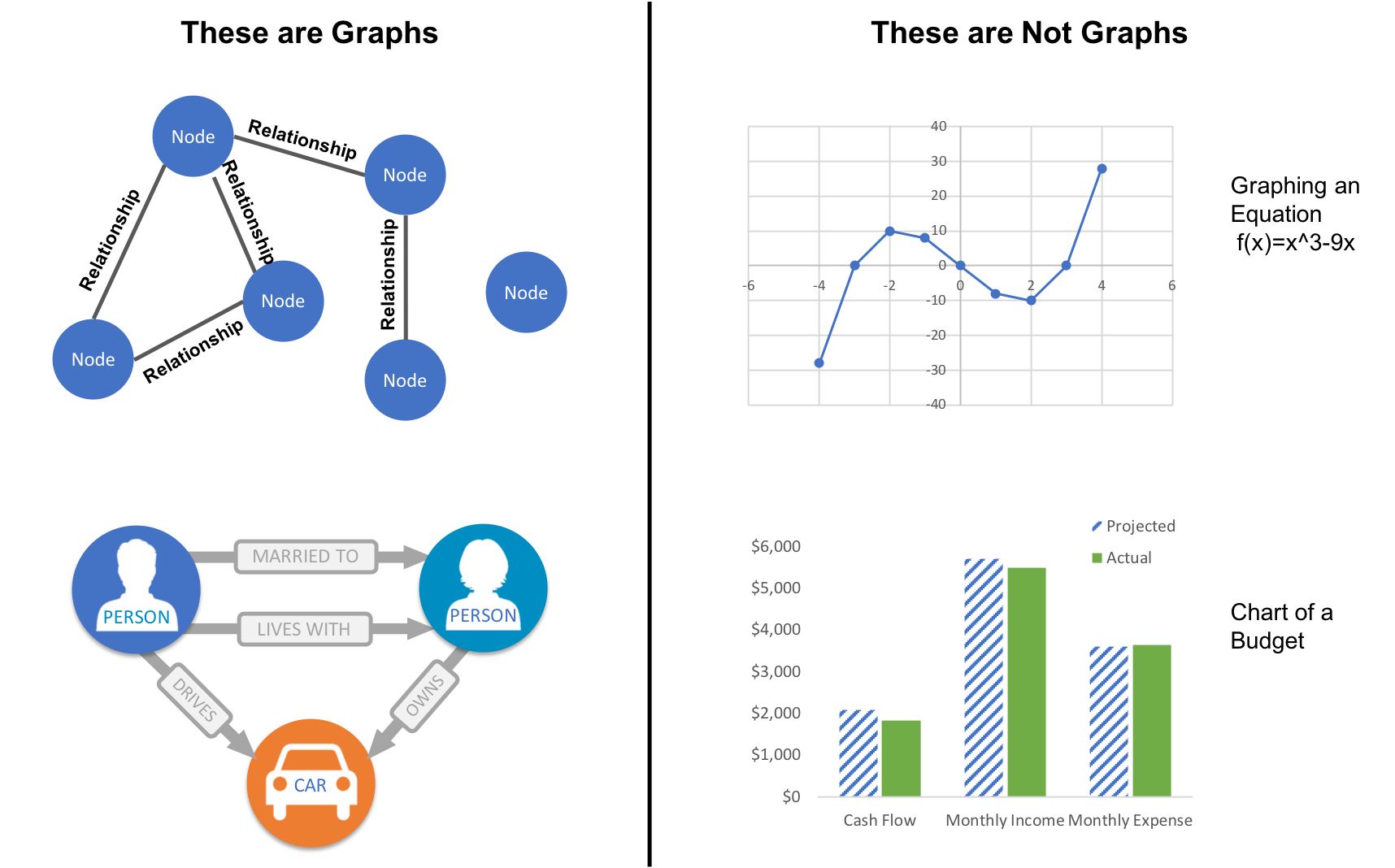

While graphs came from mathematics, they are also a pragmatic and high fidelity way of modeling and analyzing data. The objects that make up a graph are called nodes or vertices and the links between them are known as relationships, links, or edges. We use the term node in this book and you can think of nodes as the nouns in sentences. We use the term relationships and think of those as verbs giving context to the nodes. To avoid any confusion, the graphs we talk about in this book have nothing to do with graphing an equation, graphics, or charts as in Figure 1-2.

Looking at the person graph in Figure 1-2, we can easily construct several sentences which describe it. For example, person A lives with person B who owns a car and person A drives a car that person B owns. This modeling approach is compelling because it maps easily to the real world and is very “whiteboard friendly.” This helps align data modeling and algorithmic analysis.

But modeling graphs is only half the story. We might also want to process them to reveal insight that isn’t immediately obvious. This is the domain of graph algorithms.

Graph algorithms are a subset of tools for graph analytics. Graph analytics is something we do–it’s the use of any graph-based approach to analyzing connected data. There are various methods we could use: We might query the graph data, use basic statistics, visually explore the graph, or incorporate graphs into our machine learning tasks. Graph algorithms provide one of the most potent approach to analyzing connected data because their mathematical calculations are specifically built to operate on relationships.

Graph algorithms describe steps to be taken to process a graph to discover its general qualities or specific quantities. Based on the mathematics of graph theory (also known as network science), graph algorithms use the relationships between nodes to infer the organization and dynamics of complex systems. Network scientists use these algorithms to uncover hidden information, test hypotheses, and make predictions about behavior.

For example, we might like to discover neighborhoods in the graph which correspond to congestion in a transport system. Or we might want to score particular nodes that could correspond to overload conditions in a power system. In fact graph algorithms have widespread potential: from preventing fraud and optimizing call routing to predicting the spread of the flu.

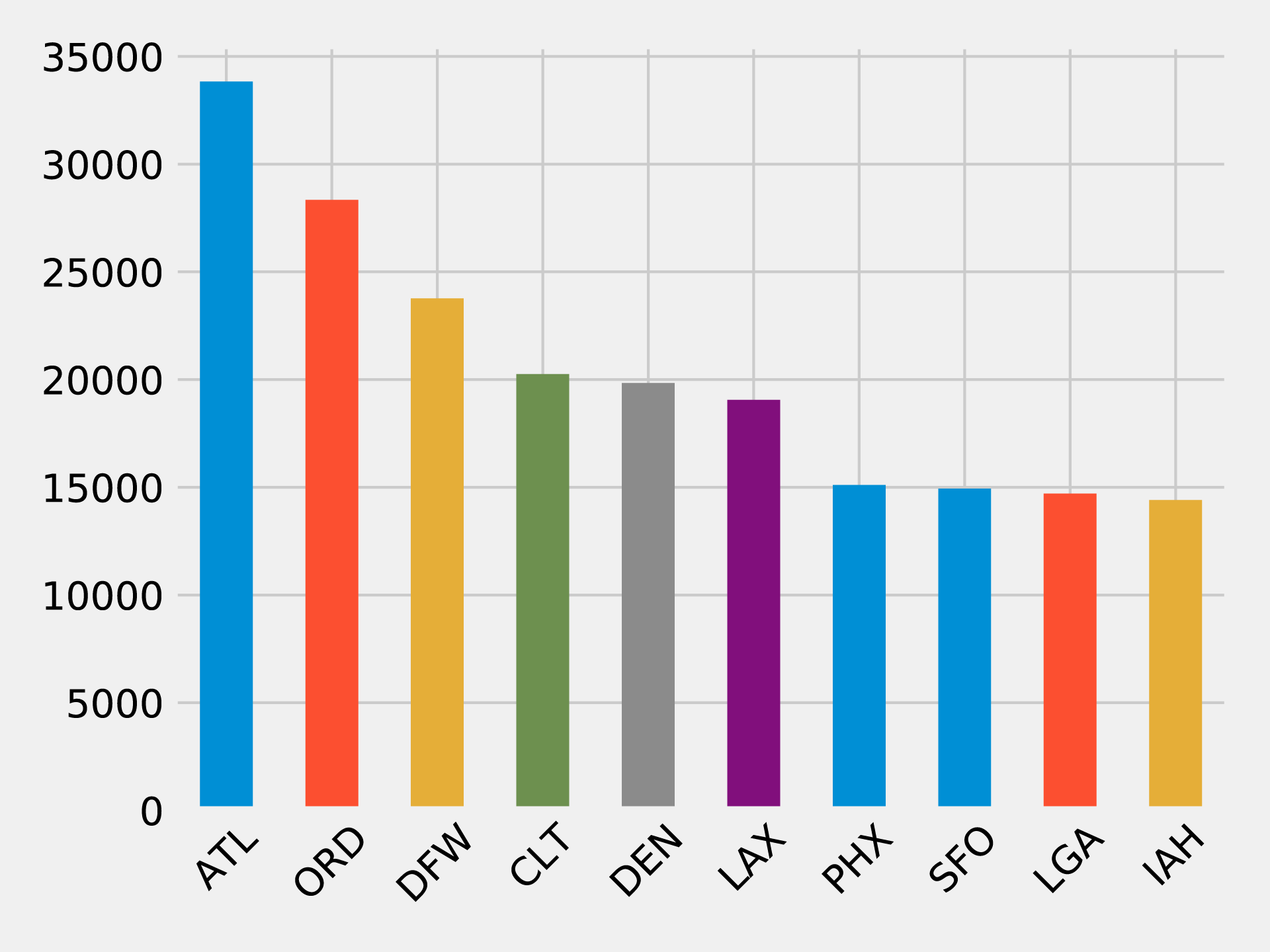

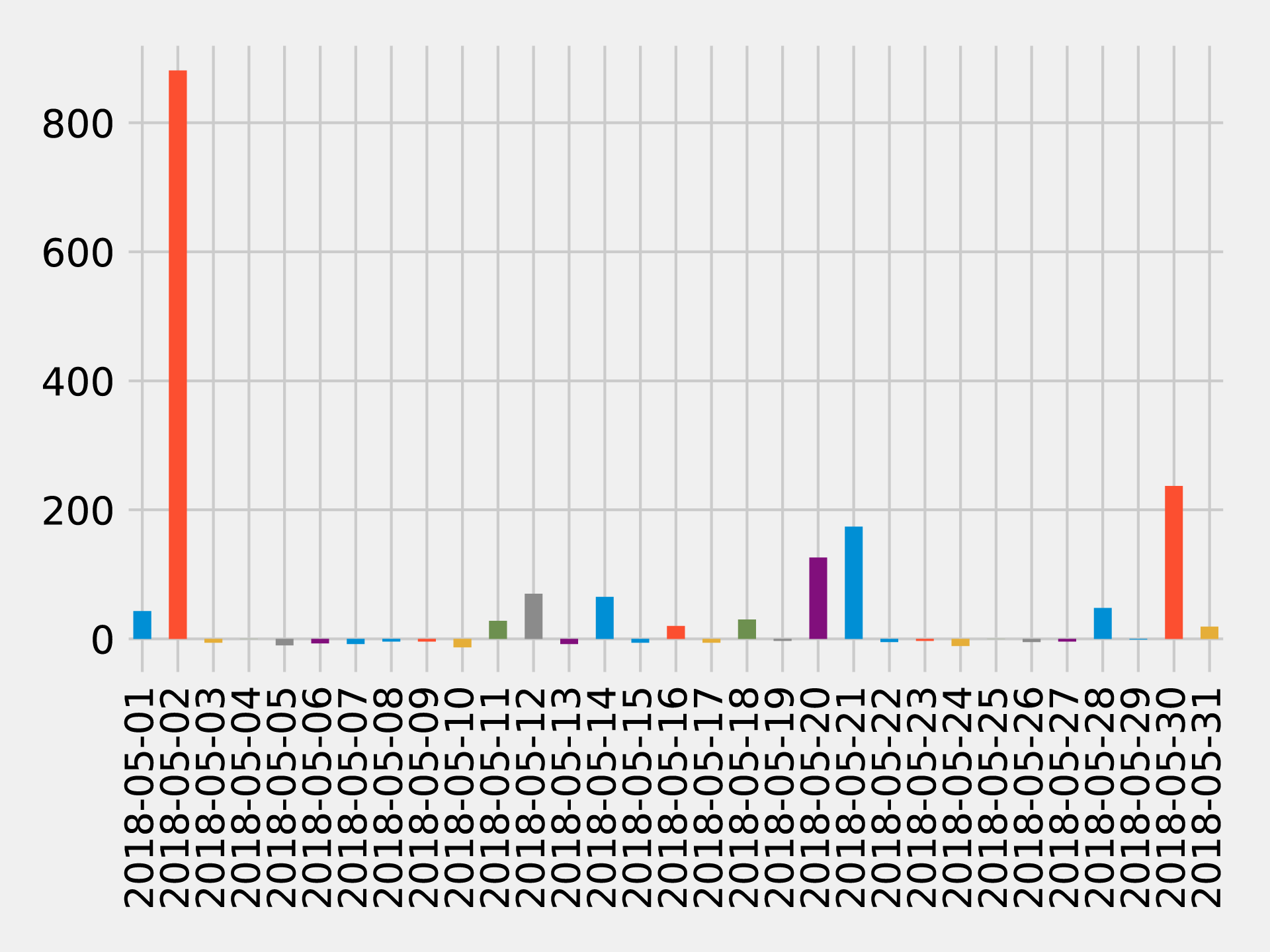

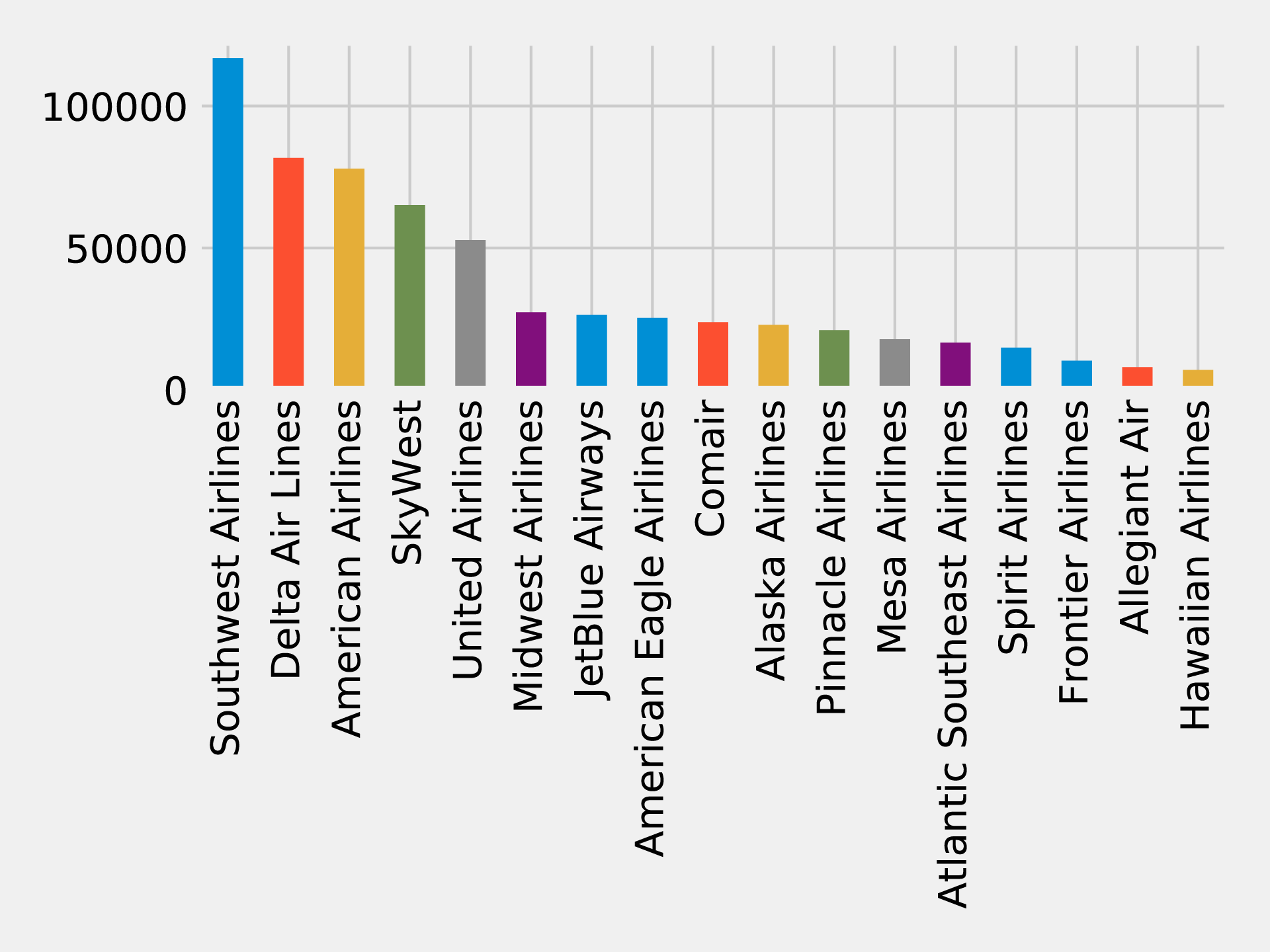

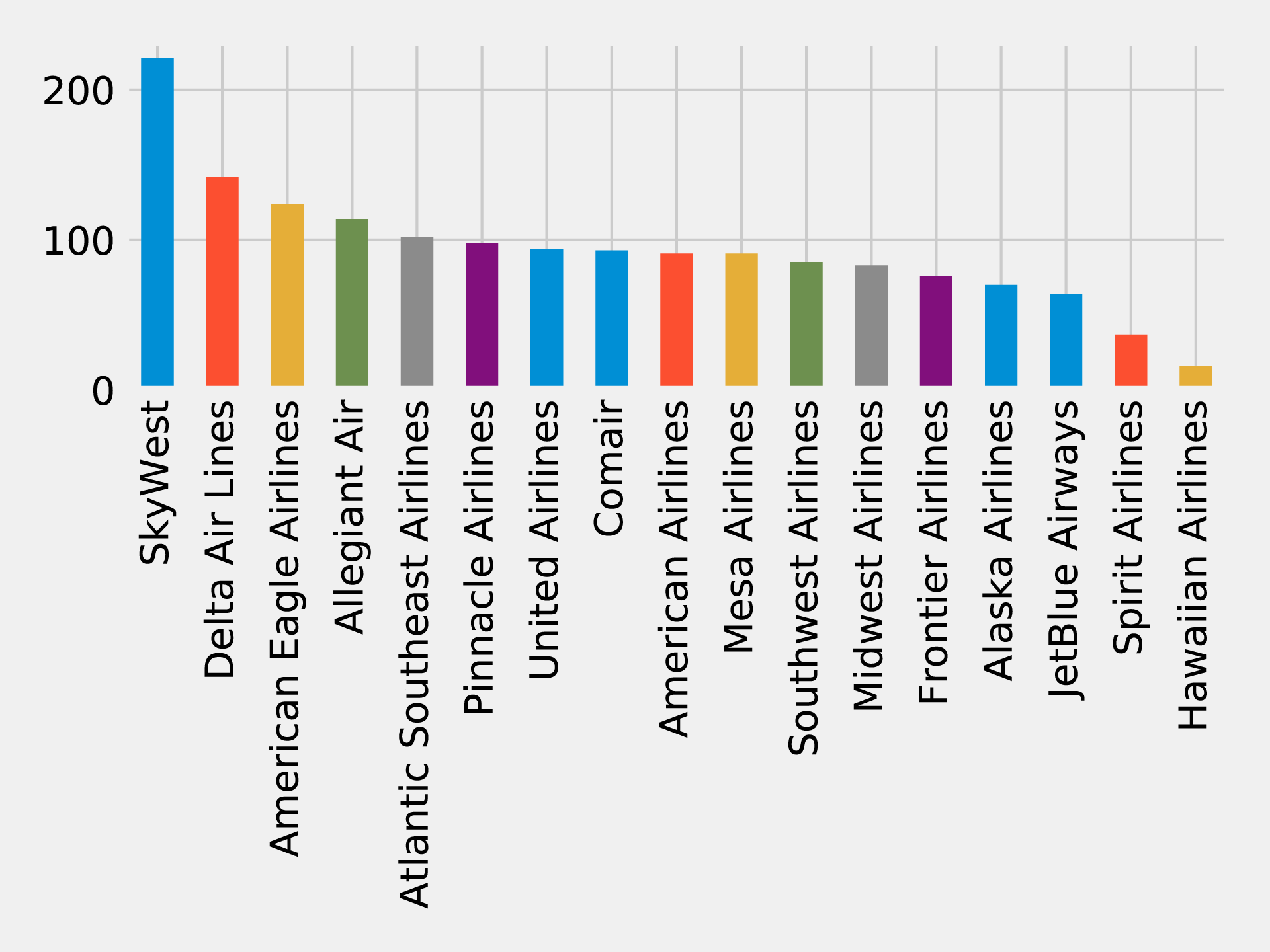

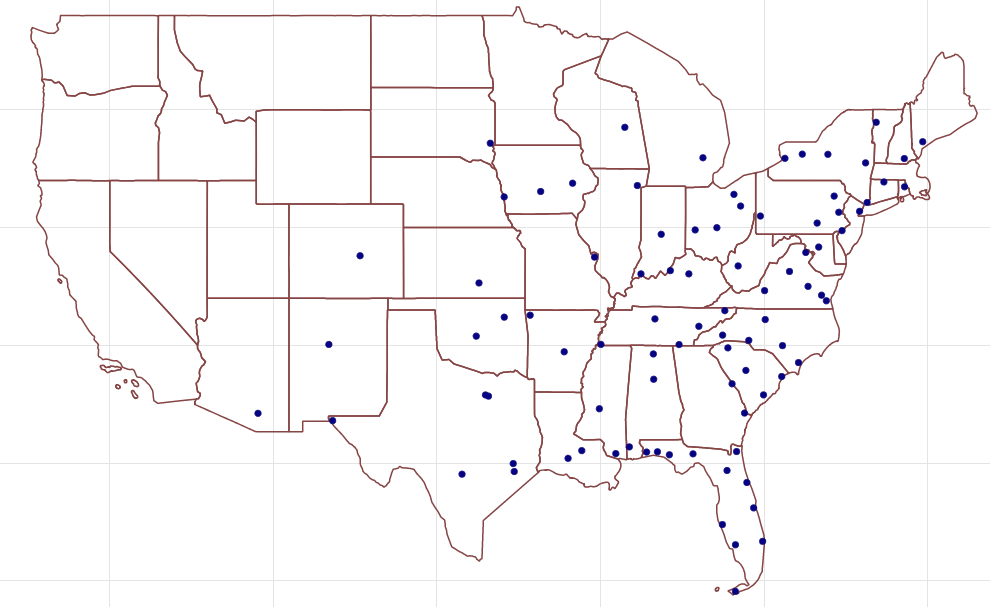

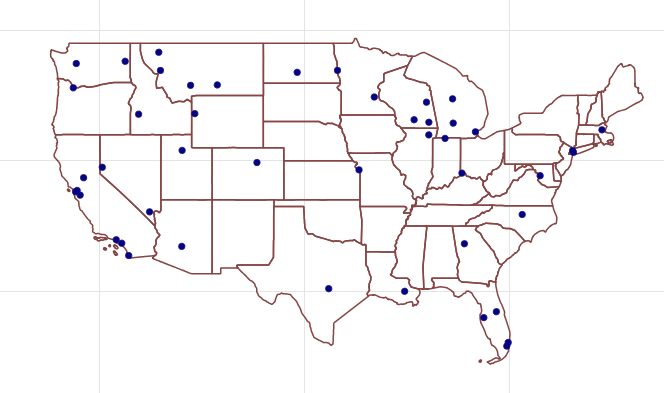

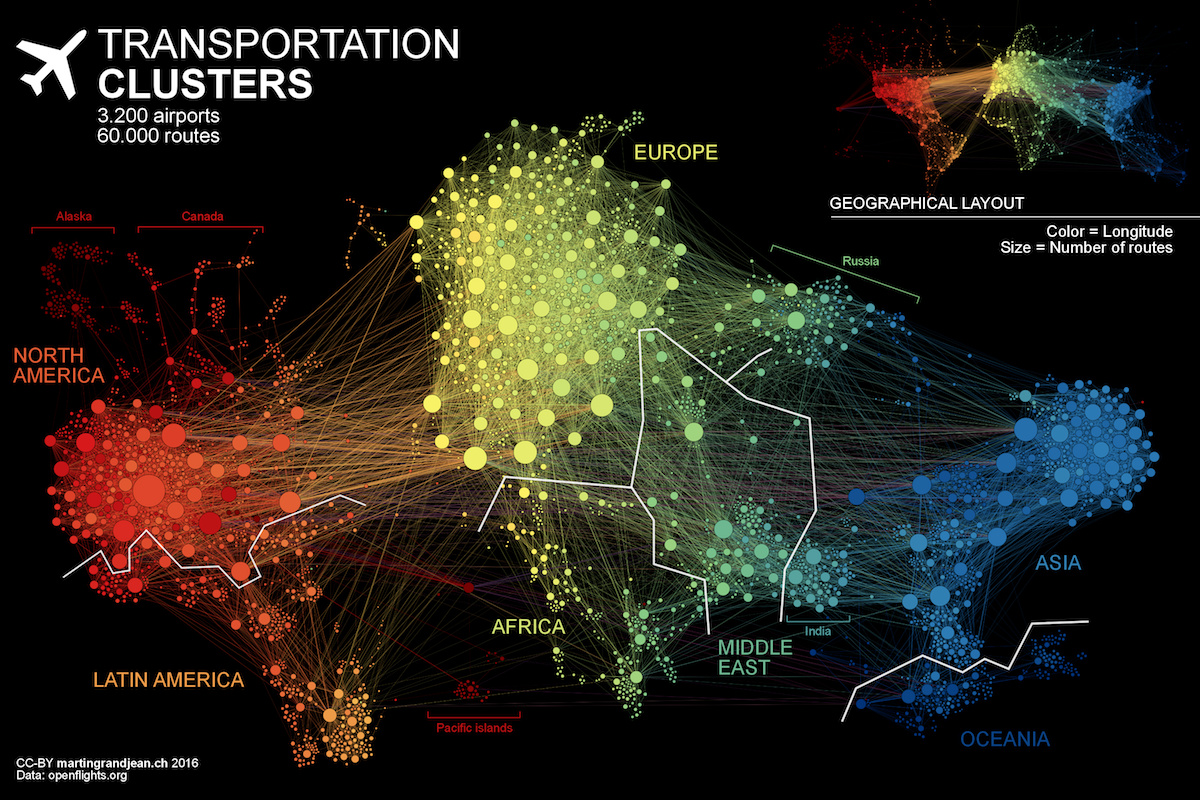

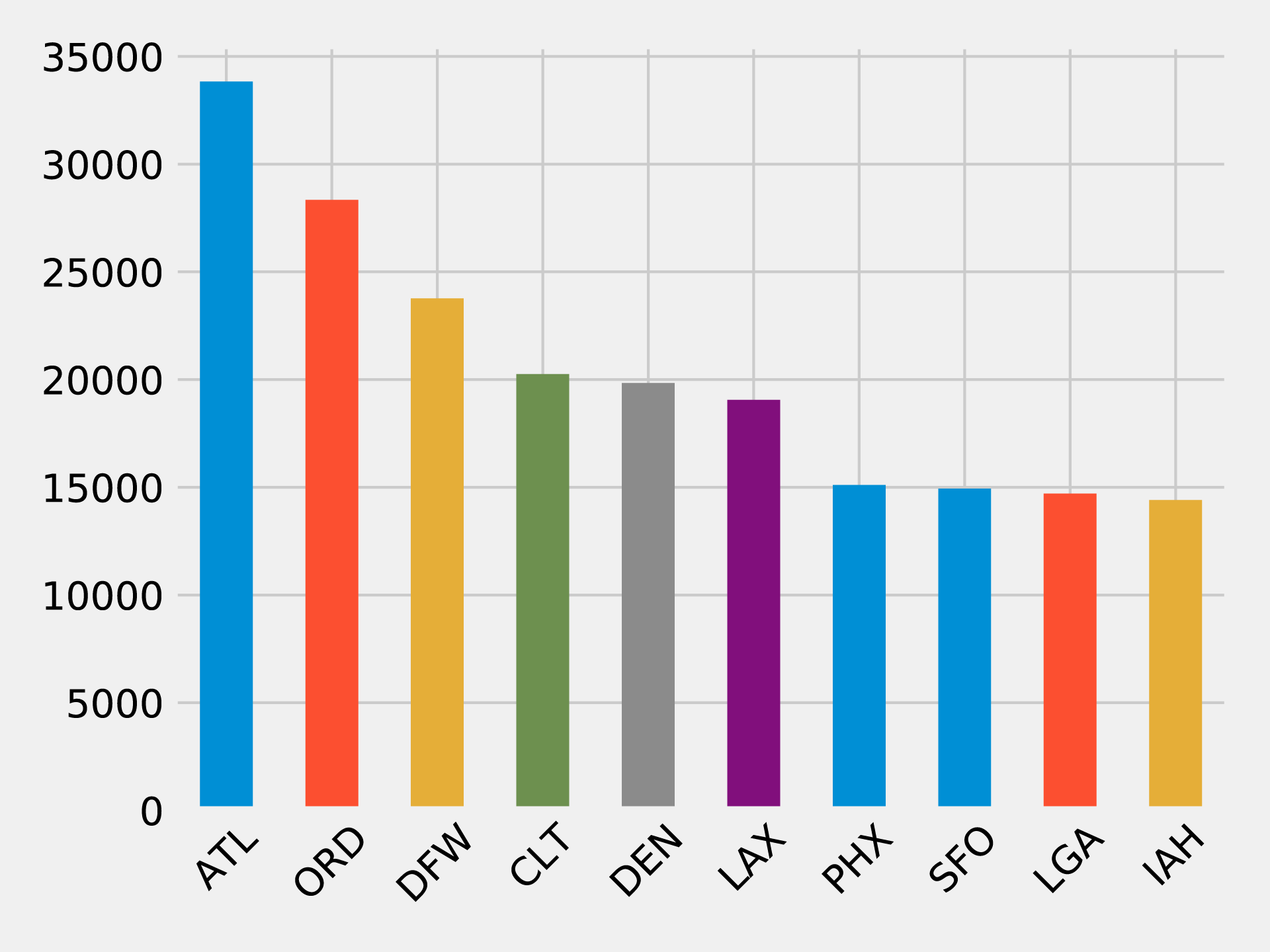

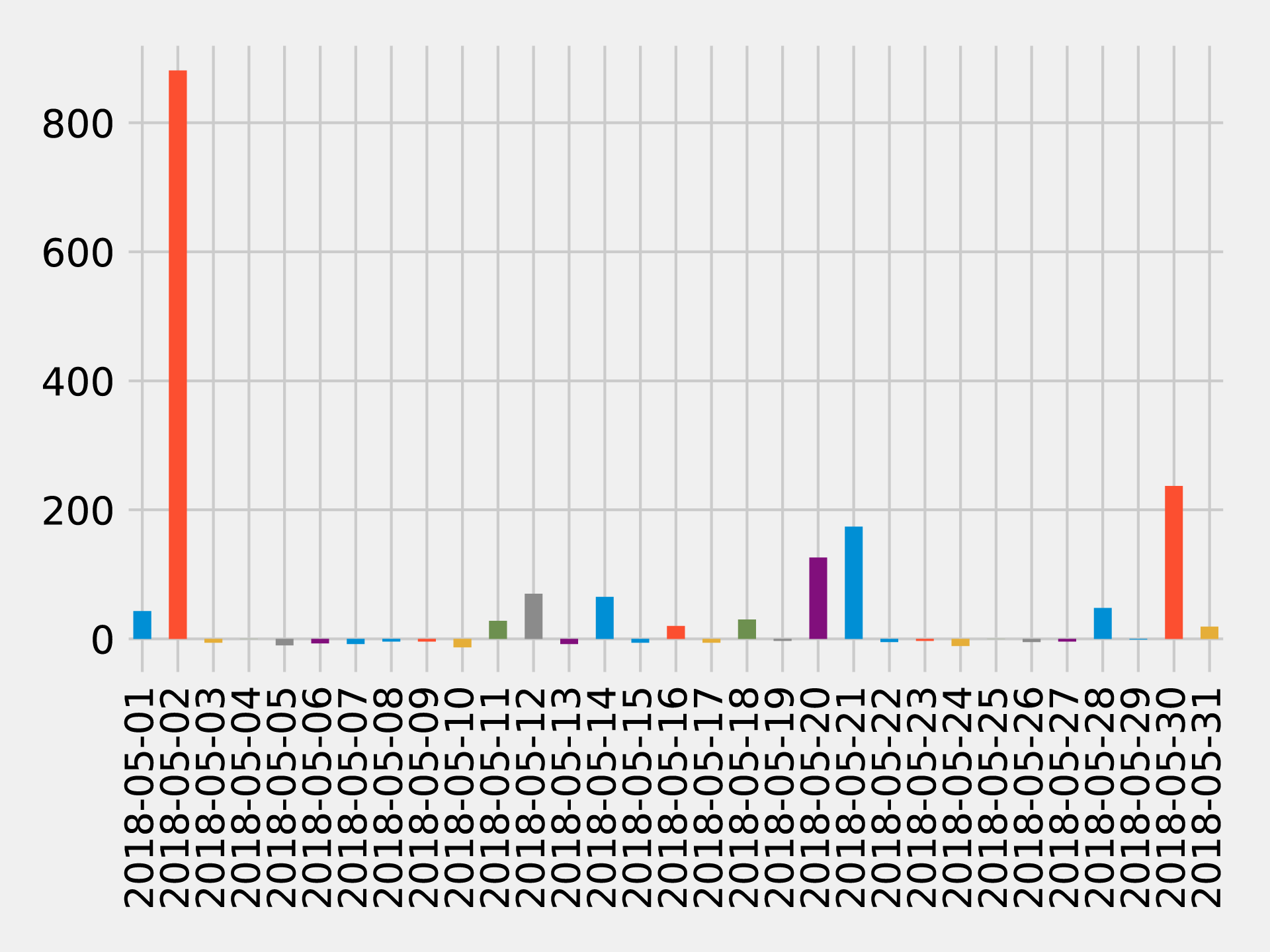

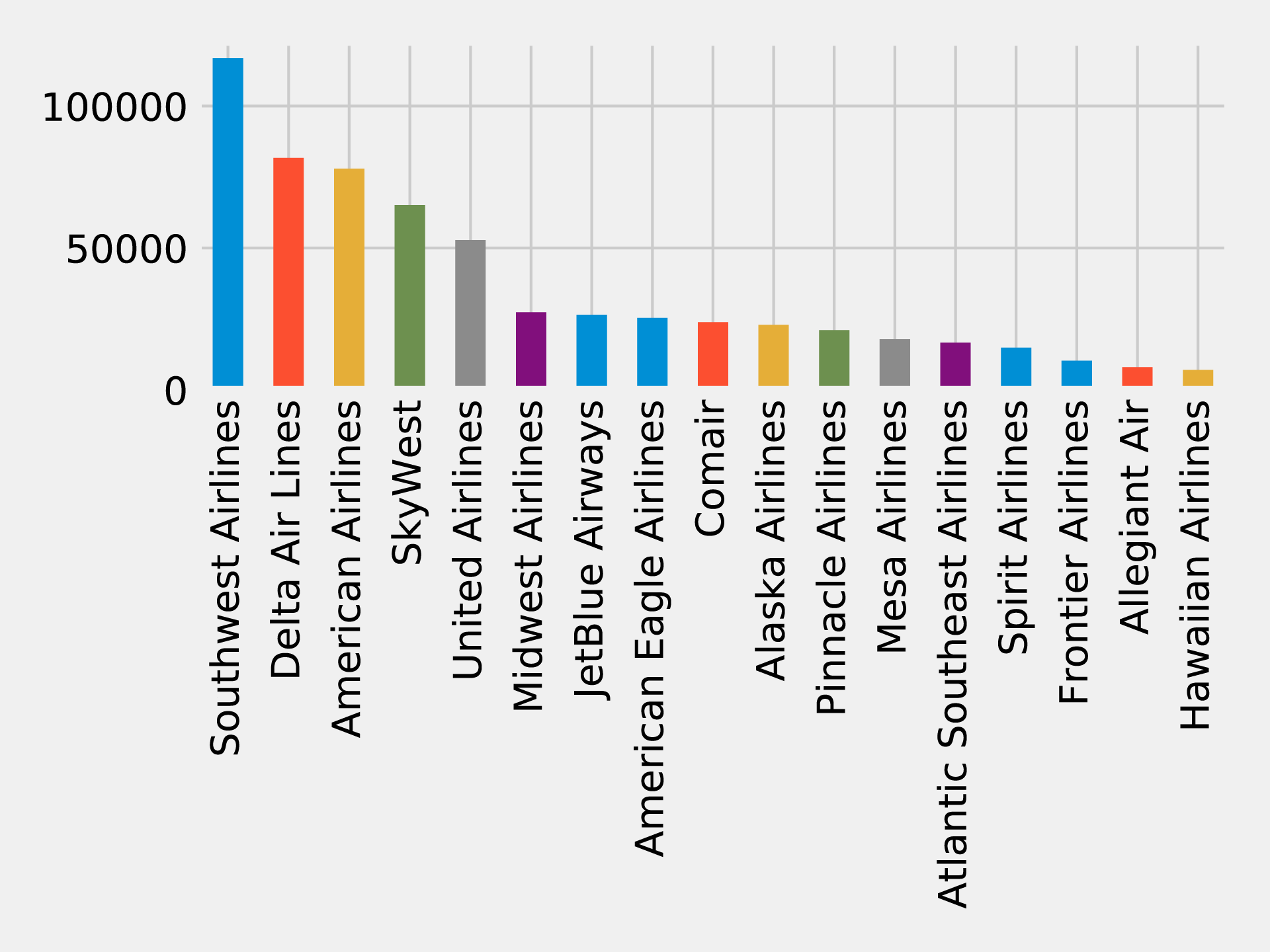

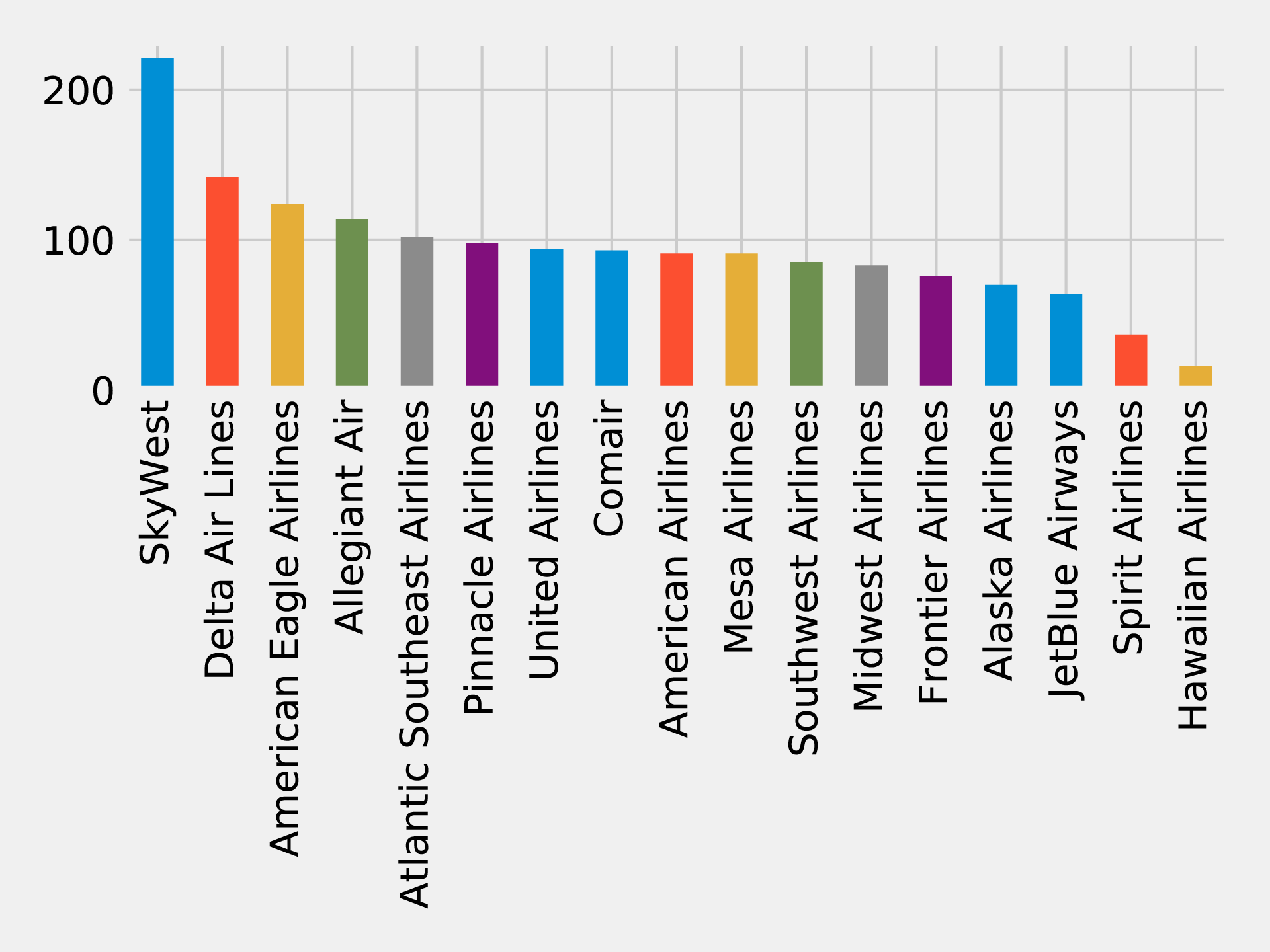

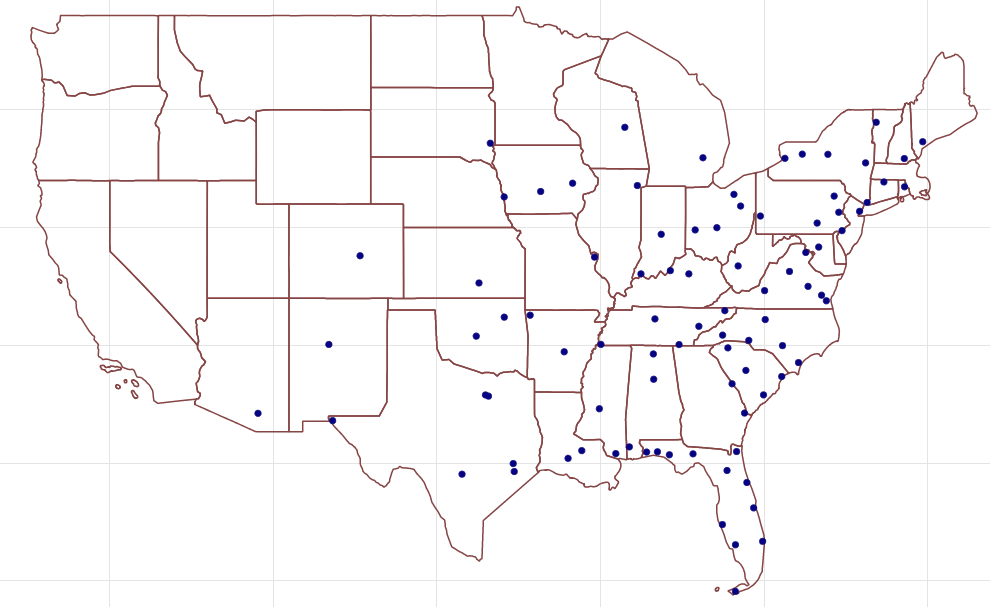

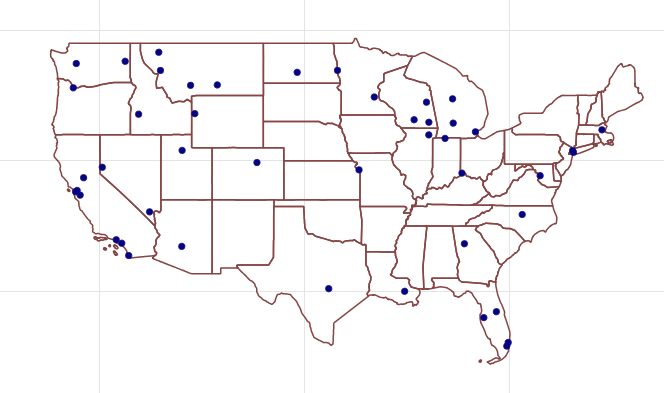

In 2010 U.S. air travel systems experienced two serious events involving multiple congested airports. Network scientists were able to use graph algorithms to confirm the events as part of systematic cascading delays and use this information for corrective advice. 1

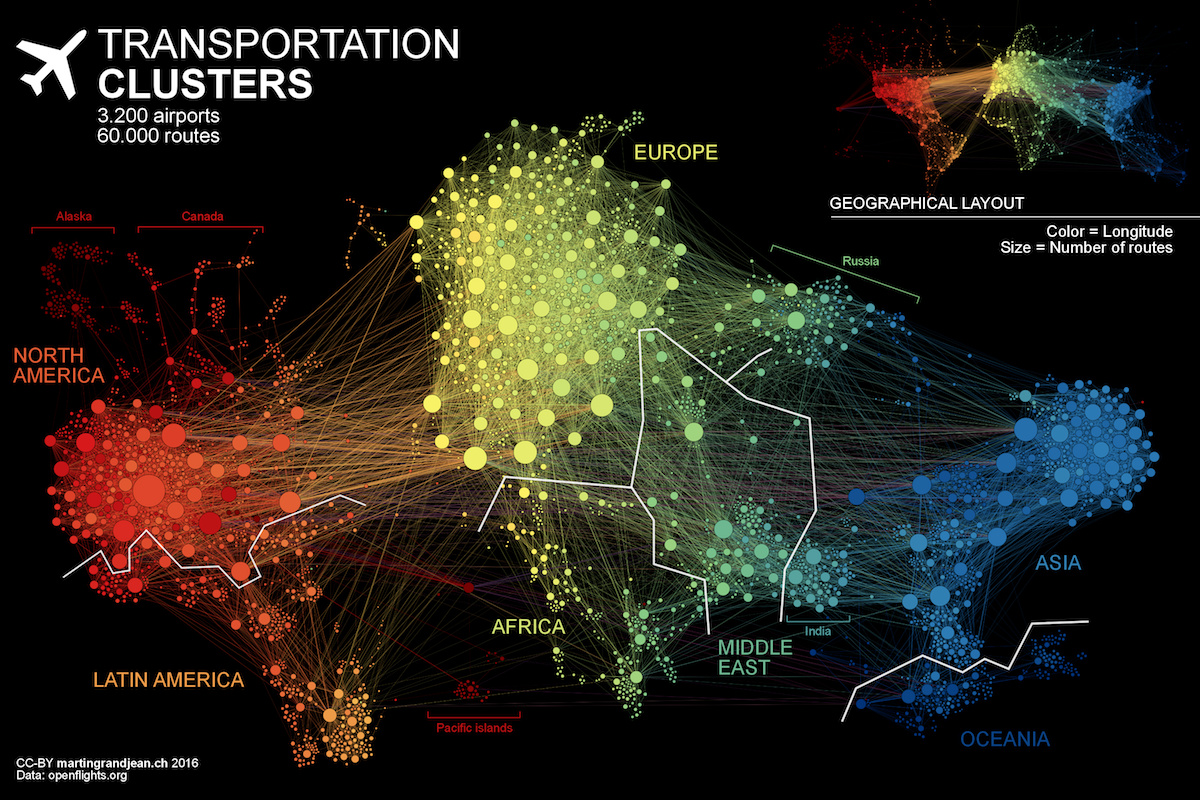

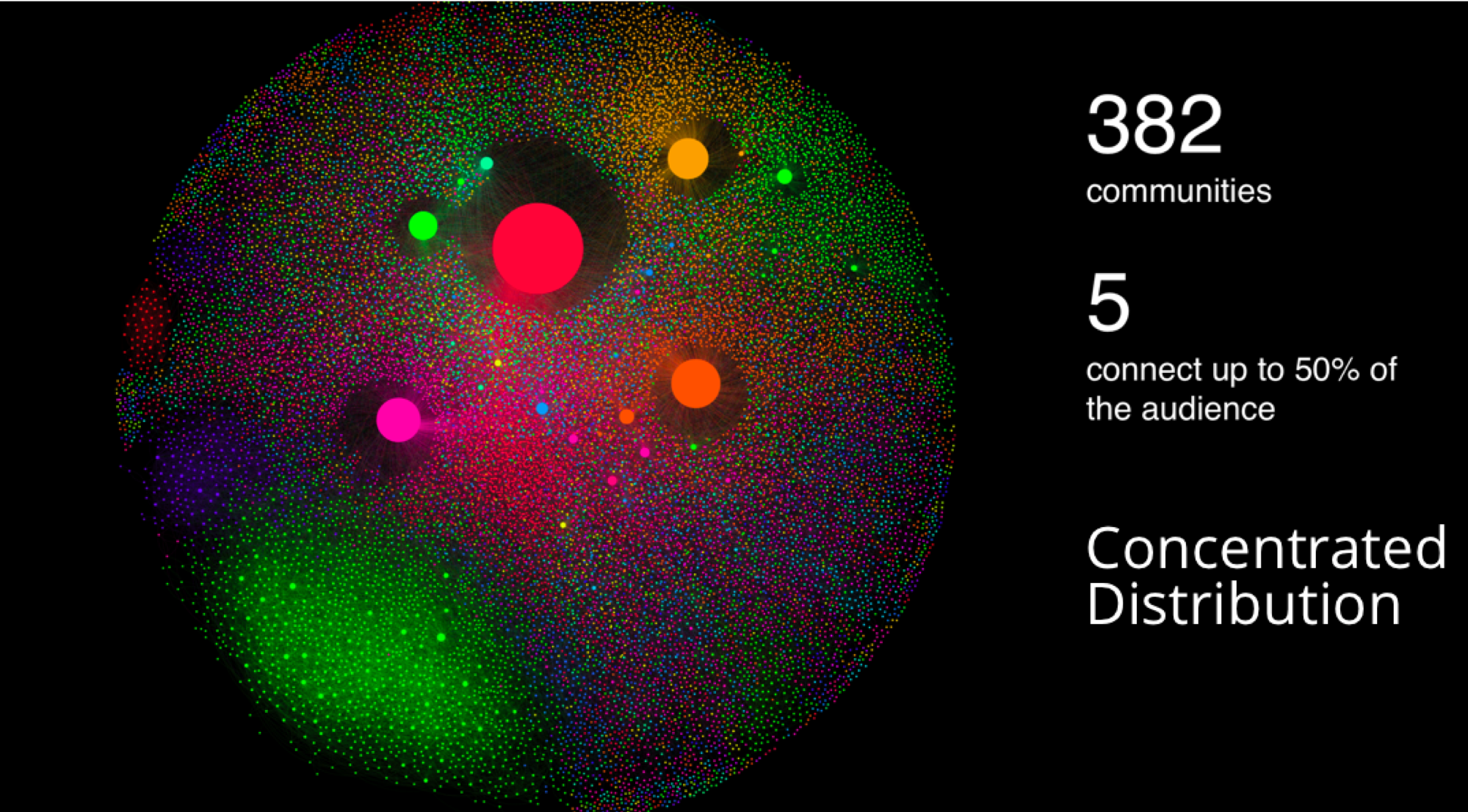

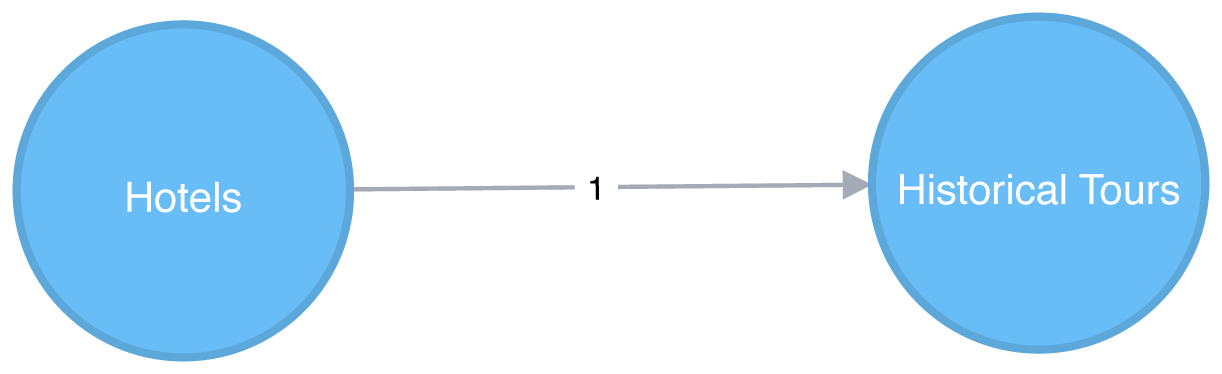

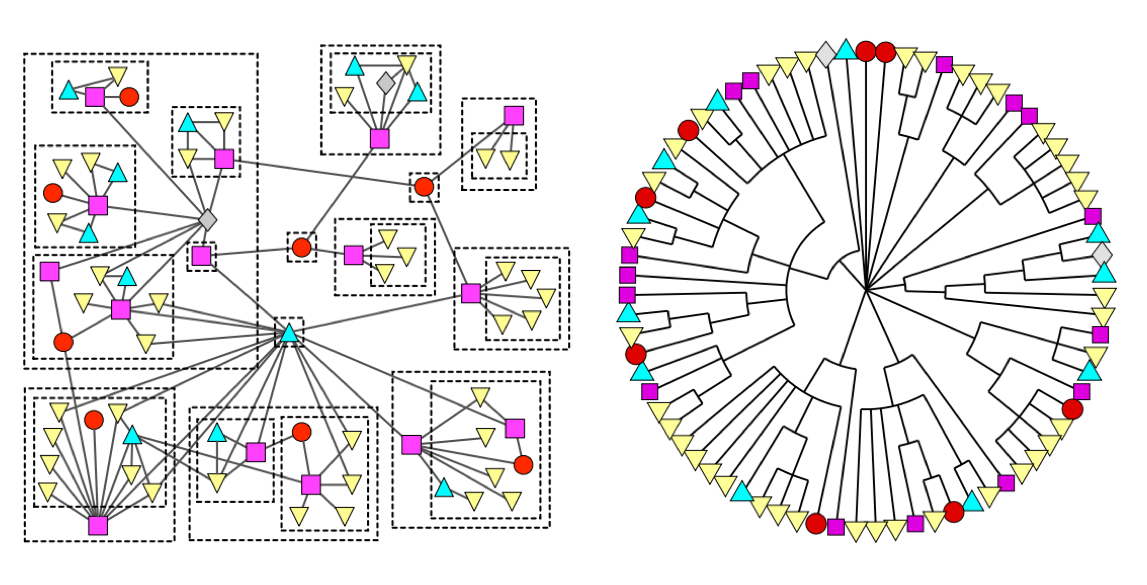

Figure 1-3 illustrates the highly connected structure of air transportation clusters. Many transportation systems exhibit a concentrated distribution of links with clear hub-and-spoke patterns that influence delays.

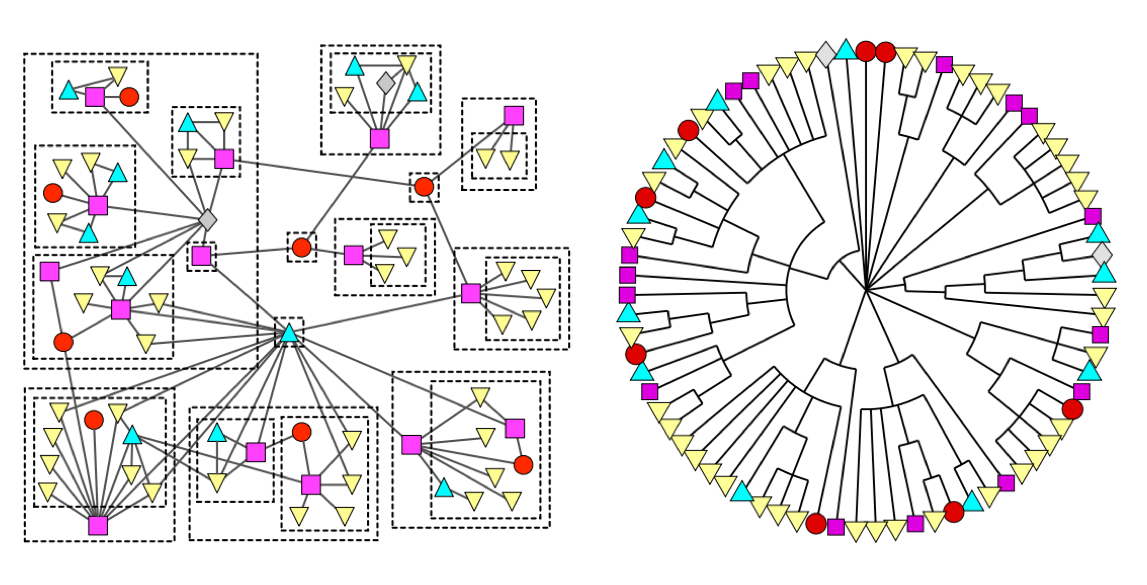

Graphs help to uncover how very small interactions and dynamics lead to global mutations. They tie together the micro- and macro-scales by representing exactly which things are interacting with each other within global structures. These associations are used to forecast behavior and determine missing links. Figure 1-4 shows a food web of grassland species interactions that used graph analysis to evaluate the hierarchical organization and species interactions and then predict missing relationships.2

Graph algorithms provide a rich and varied set of analytical tools for distilling insight from connected data. Typically, graph algorithms are employed to find global patterns and structures. The input to the algorithm is the whole graph and the output can be an enriched graph or some aggregate values such as a score. We categorize such processing as Graph Global and it implies (iteratively) processing a graph’s structure. This approach sheds light on the overall nature of a network through its connections. Organizations tend to use graph algorithms to model systems and predict behavior based on how things disseminate, important components, group identification, and the overall robustness of a system.

Conversely, for most graph queries the input is specific parts of the graph (e.g. a starting node) and the work is usually focused in the surrounding subgraph. We term this Graph Local and it implies (declaratively) querying a graph’s structure (as our colleagues explain in O’Reilly’s Graph Databases book3). There may be some overlap in these definitions: sometimes we can use processing to answer a query and querying to perform processing, but simplistically speaking whole-graph operations are processed by algorithms and subgraph operations are queried in databases.

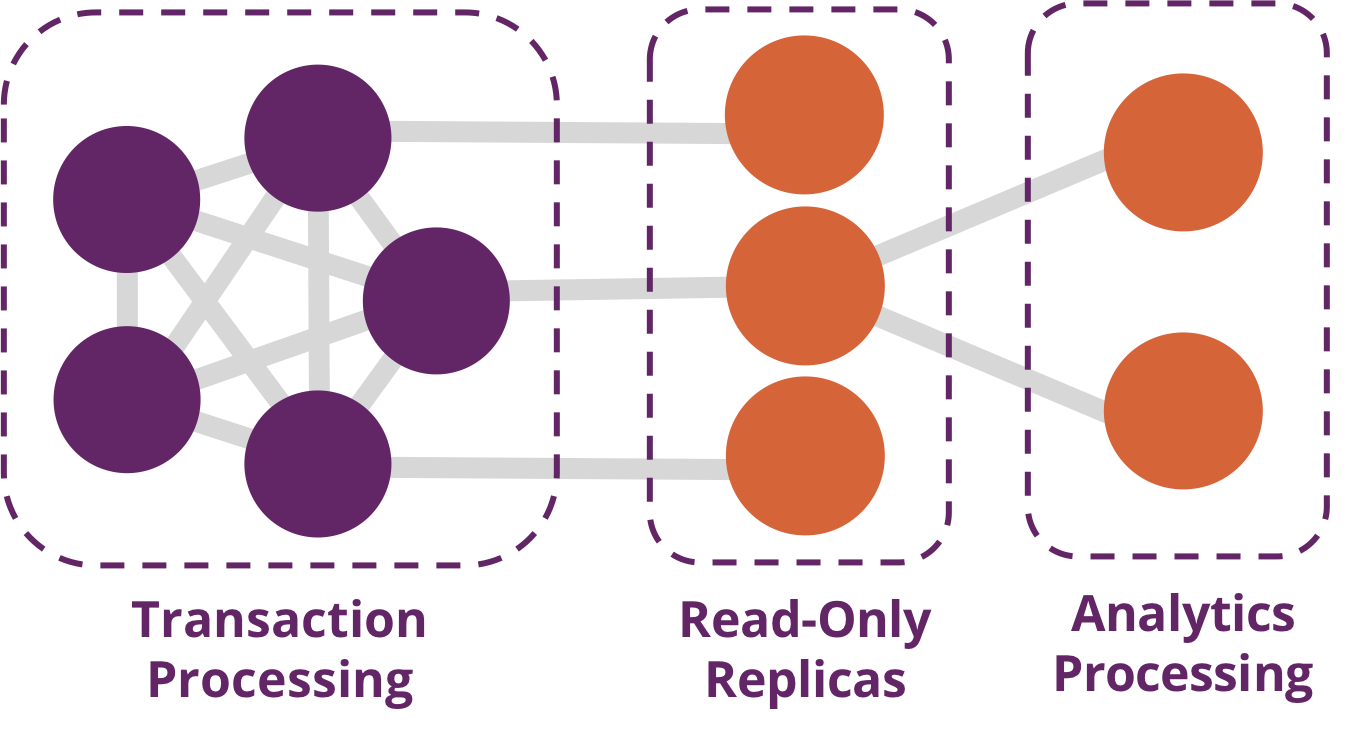

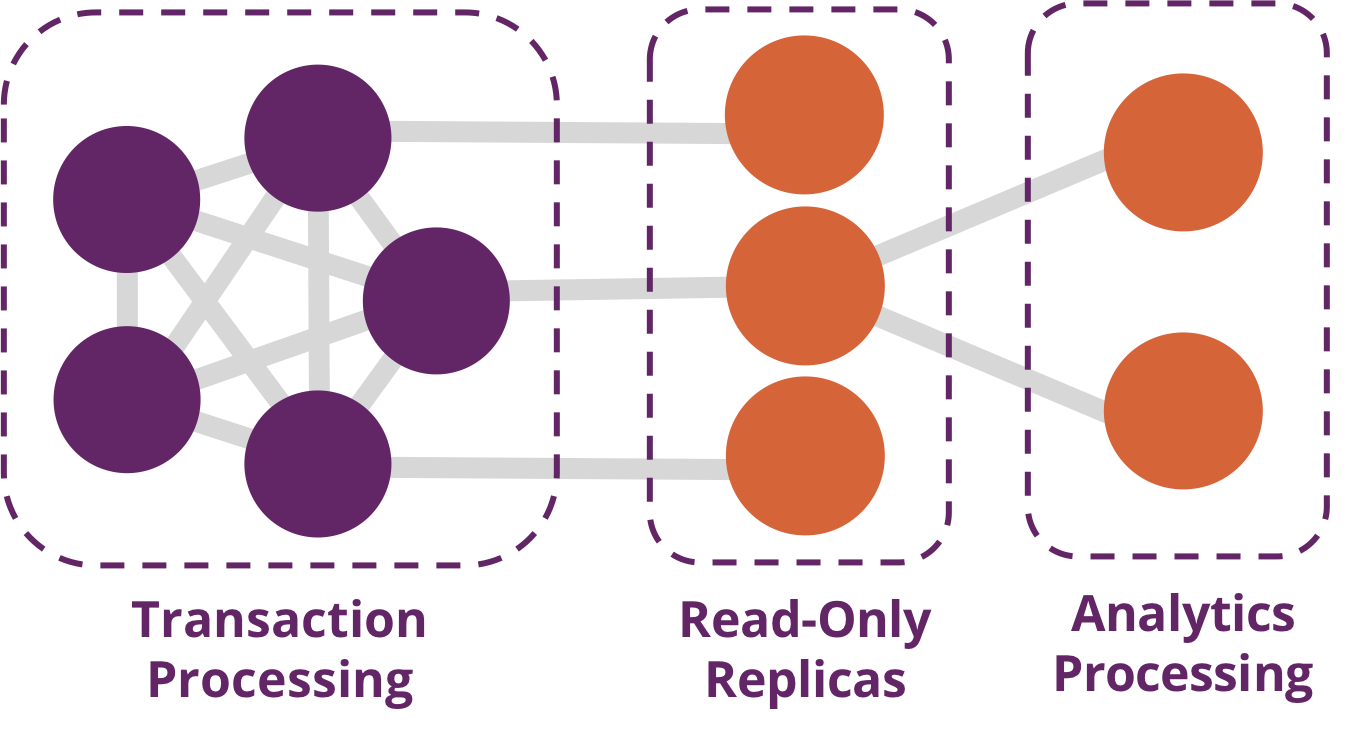

Traditionally transaction processing and analysis have been siloed. This was an unnatural split based on technology limitations. Our view is that graph analytics drives smarter transactions, which creates new data and opportunities for further analysis. More recently there has been a trend to integrate these silos for real-time decision making.

Online Transaction Processing (OLTP) operations are typically short activities like booking a ticket, crediting an account, booking a sale and so forth. OLTP implies voluminous low latency query processing and high data integrity. Although OLTP may involve only a smaller number of records per transaction, systems process many transactions concurrently.

Online Analytical Processing (OLAP) facilitates more complex queries and analysis over historical data. These analyses may include multiple data sources, formats, and types. Detecting trends, conducting “what-if” scenarios, making predictions, and uncovering structural patterns are typical OLAP use cases. Compared to OLTP, OLAP systems process fewer but longer-running transactions over many records. OLAP systems are biased towards faster reading without the expectation of transactional updates found in OLTP and batch-oriented operation is common.

Recently, however, the line between OLTP and OLAP started to blur. Modern data-intensive applications now combine real-time transactional operations with analytics. This merging of processing has been spurred by several advances in software such as more scalable transaction management, incremental stream processing, and in lower-cost, large-memory hardware.

Bringing together analytics and transactions enables continual analysis as a natural part of regular operations. As data is gathered–from point-of-sale (POS) machines, from manufacturing systems, or from IoT devices–analytics now supports the ability to make real-time recommendations and decisions while processing. This trend was observed several years ago, and terms to describe this merging include “Transalytics” and Hybrid Transactional and Analytical Processing (HTAP). Figure 1-5 illustrates how read-only replicas can be used to bring together these different types of processing.

“[HTAP] could potentially redefine the way some business processes are executed, as real-time advanced analytics (for example, planning, forecasting and what-if analysis) becomes an integral part of the process itself, rather than a separate activity performed after the fact. This would enable new forms of real-time business-driven decision-making process. Ultimately, HTAP will become a key enabling architecture for intelligent business operations.” –Gartner

OLTP and OLAP become more integrated and support functionality previously offered in only one silo, it’s no longer necessary to use different data products or systems for these workloads–we can simplify our architecture by using the same platform for both. This means our analytical queries can take advantage of real-time data and we can streamline the iterative process of analysis.

Graph algorithms are used to help make sense of connected data. We see relationships within real-world systems from protein interactions to social networks, from communication systems to power grids, and from retail experiences to Mars mission planning. Understanding networks and the connections within them offers incredible potential for insight and innovation.

Graph algorithms are uniquely suited to understanding structures and revealing patterns in datasets that are highly connected. Nowhere is the connectivity and interactivity so apparent than in big data. The amount of information that has been brought together, commingled, and dynamically updated is impressive. This is where graph algorithms can help make sense of our volumes of data: for both sophisticated analytics of the graph and to improve artificial intelligence by fuelling our models with structural context.

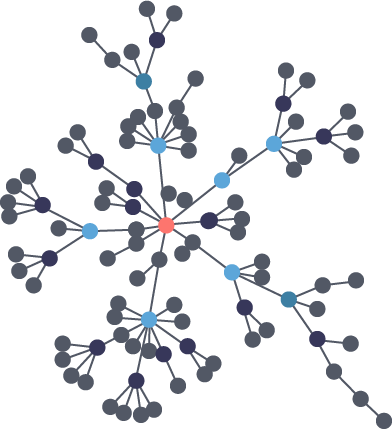

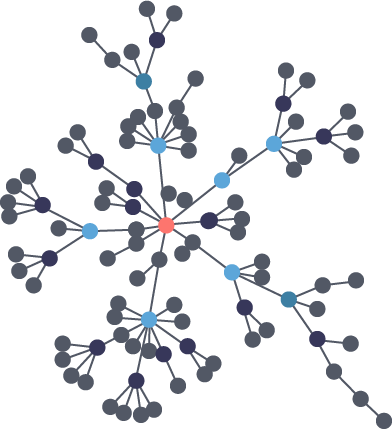

Scientists that study the growth of networks have noted that connectivity increases over time, but not uniformly. Preferential attachment is one theory on how the dynamics of growth impact structure. This idea, illustrated in Figure 1-6, describes the tendency of a node to link to other nodes that already have a lot of connections.

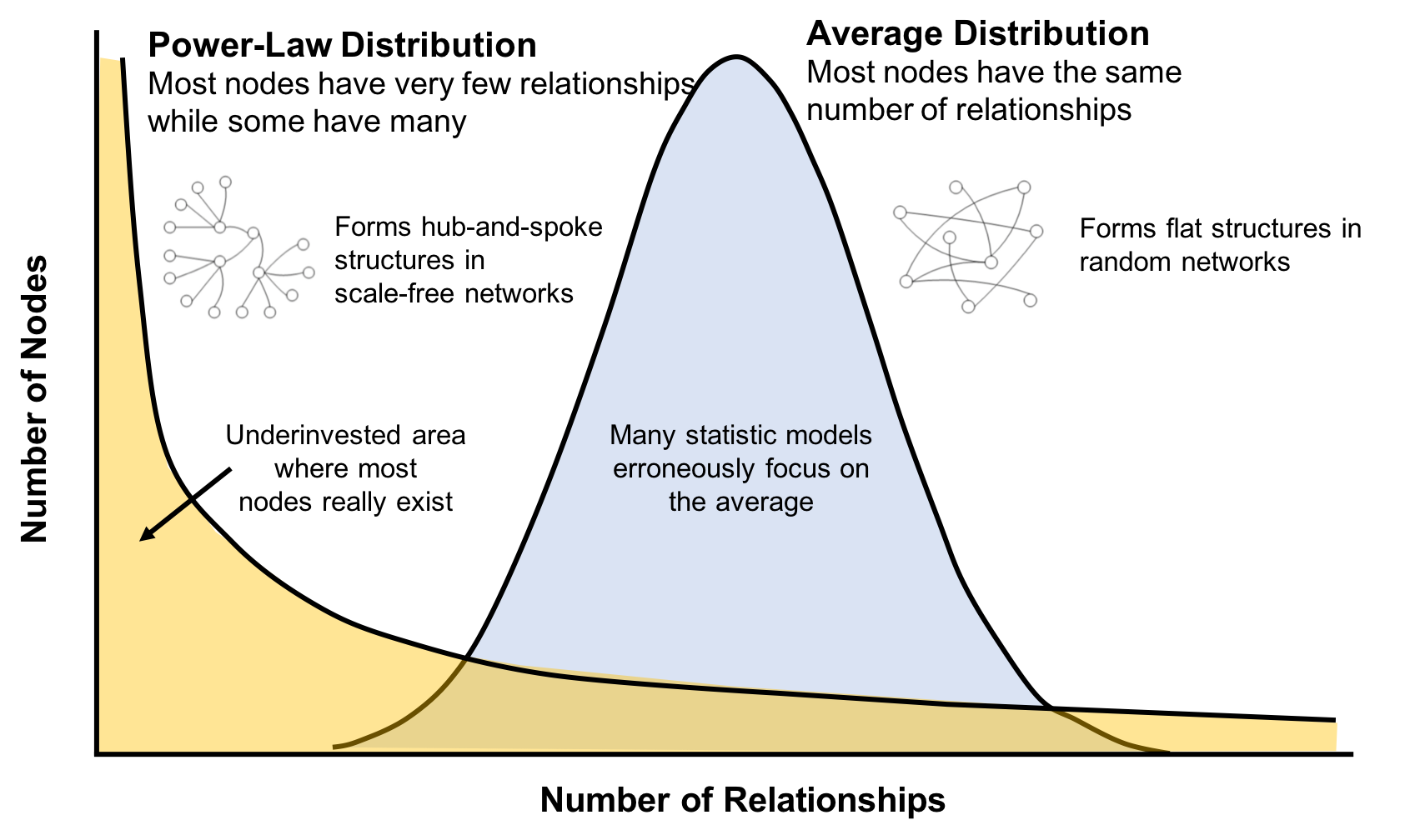

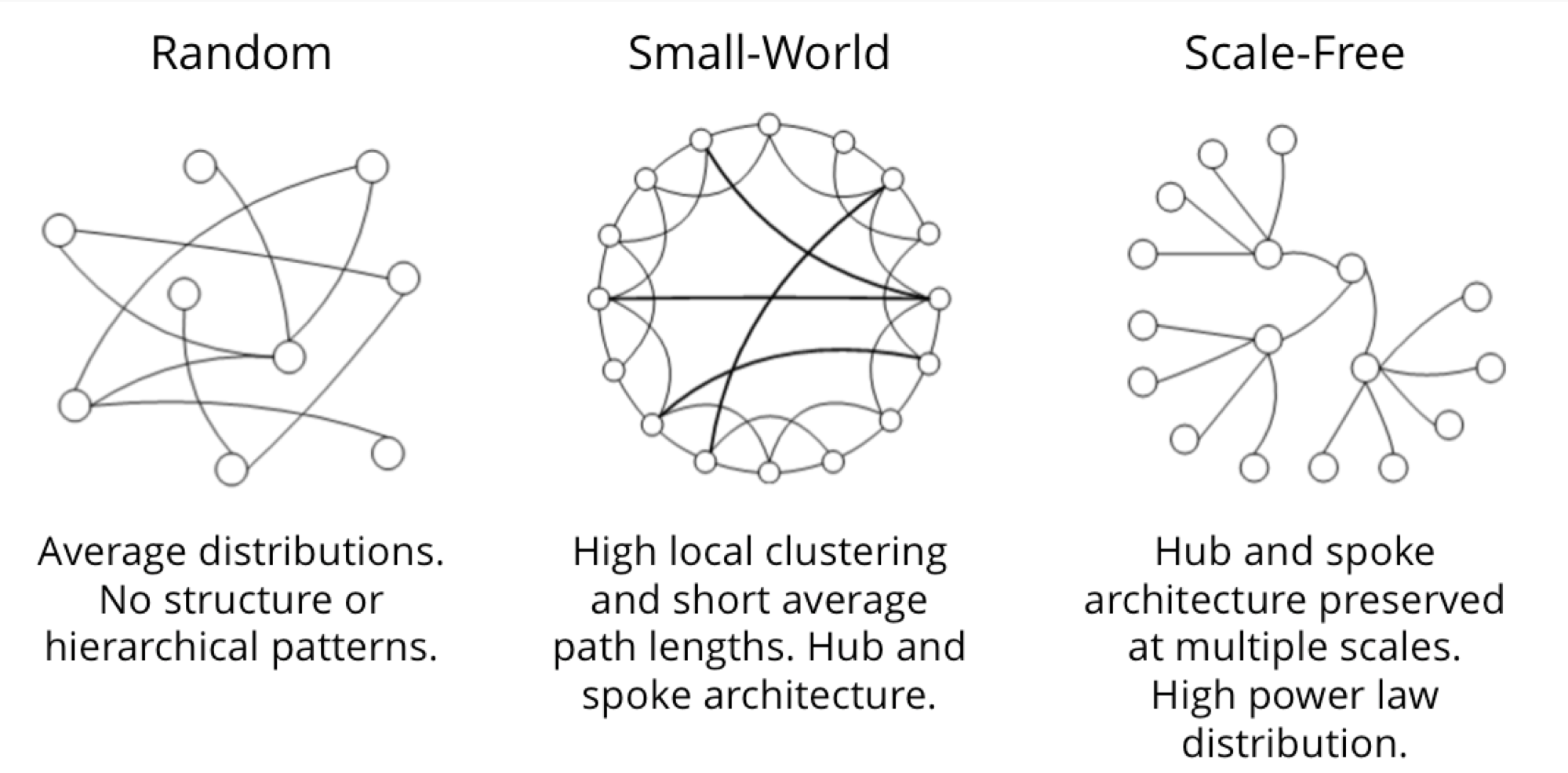

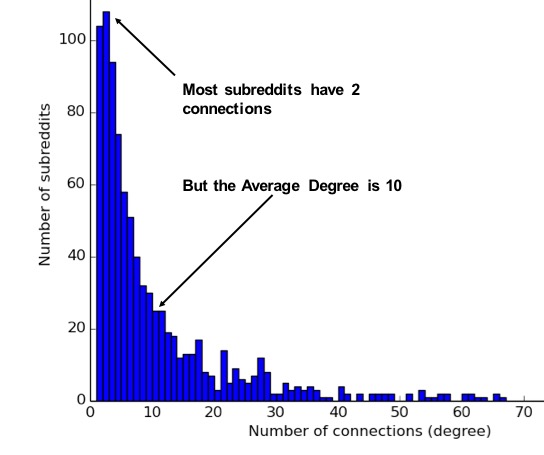

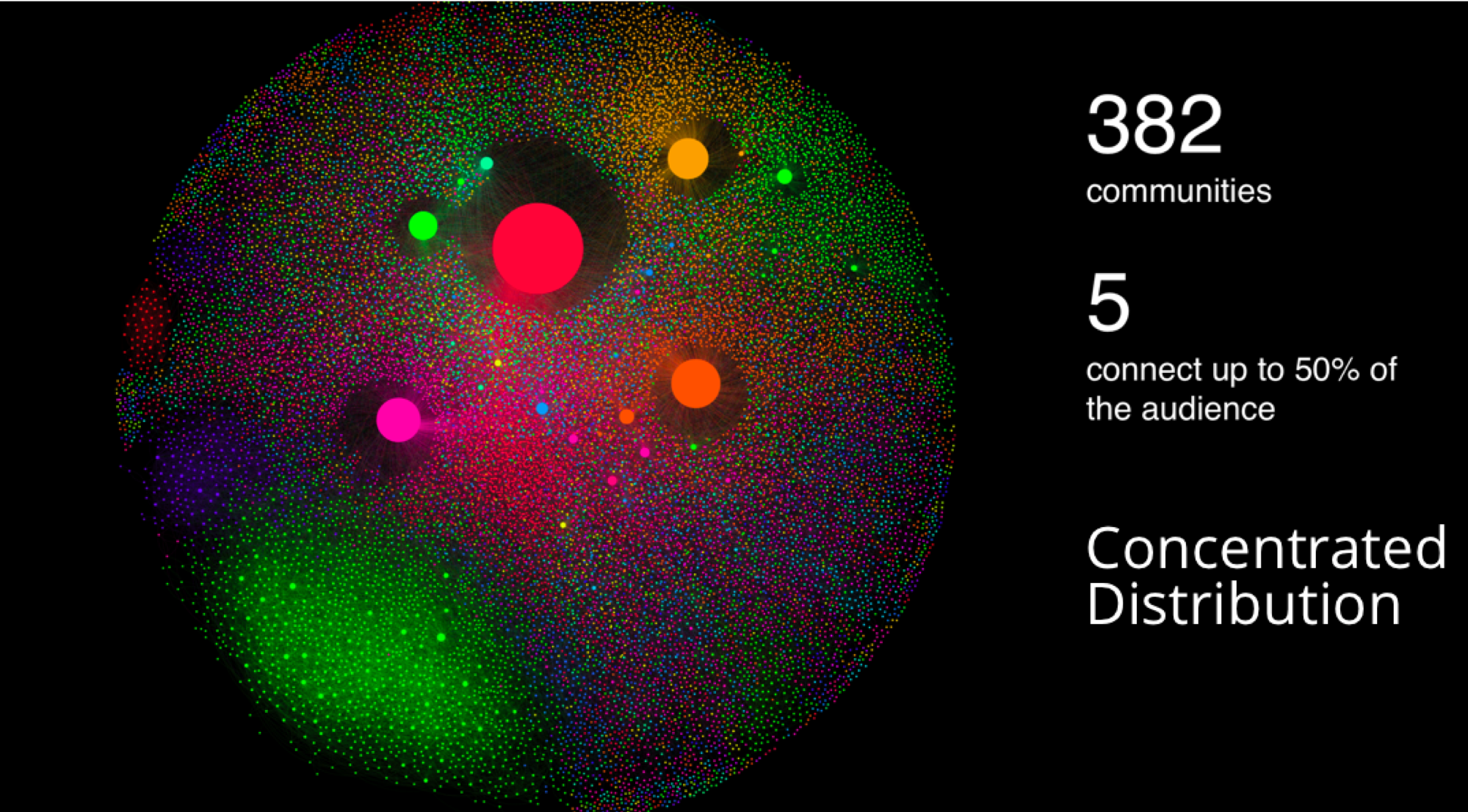

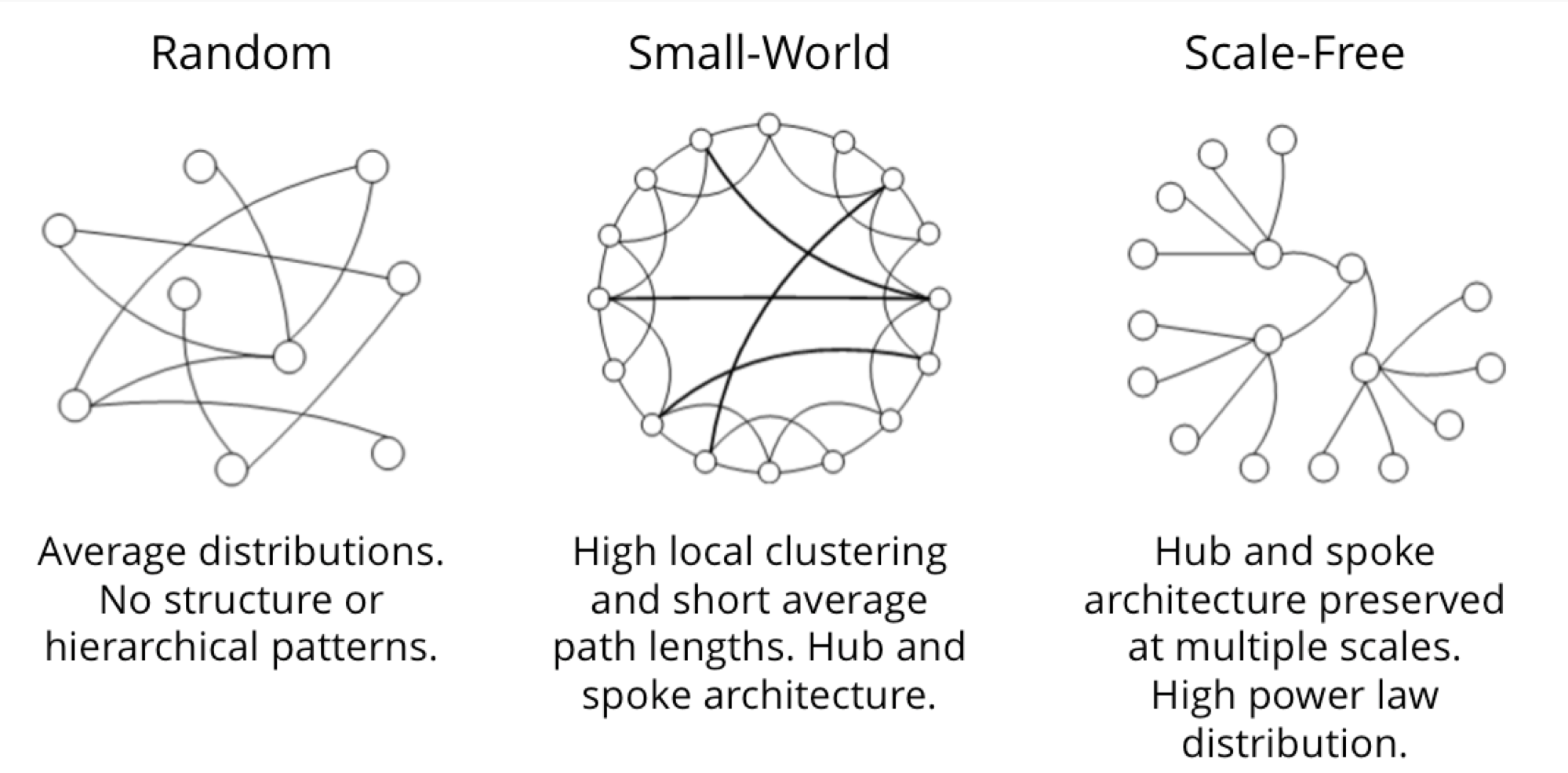

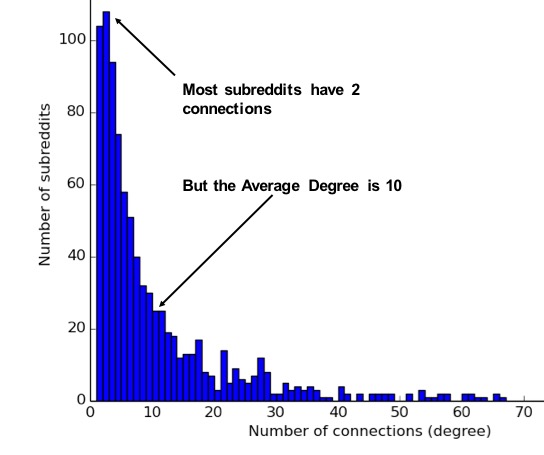

Regardless of the underlying causes, many researchers believe that how a network develops is inseparable from their resulting shapes and hierarchies. Highly dense groups and lumpy data networks tend to develop, in effect growing both data size and its complexity. Trying to “average out” the network, in general, won’t work well for investigating relationships. We see this clustering of relationships in most real-world networks today from the internet to social networks such as a gaming community shown in Figure 1-7.

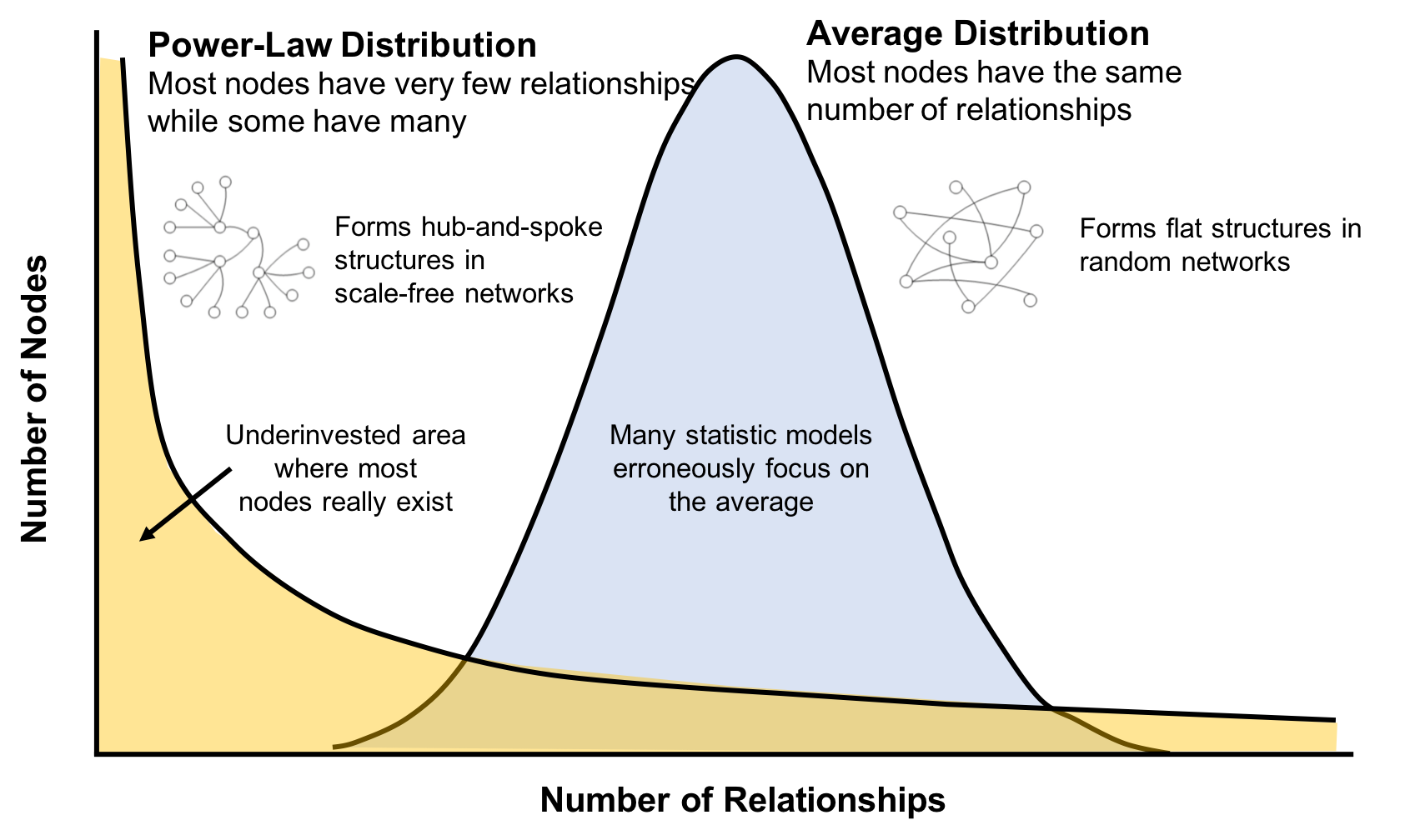

This is significantly different than what an average distribution model would predict, where most nodes would have the same number of connections. For instance, if the World Wide Web had an average distribution of connections, all pages would have about the same number of links coming in and going out. Average distribution models assert that most nodes are equally connected but many types of graphs and many real networks exhibit concentrations. The Web, in common with graphs like travel and social networks, has a power-law distribution with few nodes being highly connected and most nodes being modestly connected.

We can readily see in Figure 1-8; how using an average of characteristics for data that is uneven, would lead to incorrect results.

This is important to recognize as most graph data does not adhere to an average distribution. Network scientists use graph analytics to search for and interpret structures and relationship distributions in real-world data.

There is no network in nature that we know of that would be described by the random network model. —Albert-László Barabási, director, Center for Complex Network Research Northeastern University, and author of numerous network science books

The challenge is that densely yet unevenly connected data is troublesome to analyze with traditional analytical tools. There might be a structure there but it’s hard to find. So, it’s tempting to take an averages approach to messy data but doing so will conceal patterns and ensure our results are not representing any real groups. For instance, if you average the demographic information of all your customers and offer an experience based solely on averages, you’d be guaranteed to miss most communities: communities tend to cluster around related factors like age and occupation or marital status and location.

Furthermore, dynamic behavior, particularly around sudden events and bursts, can’t be seen with a snapshot. To illustrate, if you imagine a social group with increasing relationships, you’d also expect increased communications. This could lead to a tipping point of coordination and a subsequent coalition or, alternatively, subgroup formation and polarization in, for example, elections. Sophisticated methods are required to forecast a network’s evolution over time but we can infer behavior if we understand the structures and interactions within our data. Graph analytics are used to predict group resiliency because of the focus on relationships.

At the most abstract level, graph analytics is applied to forecast behavior and prescribe action for dynamic groups. Doing this requires understanding the relationships and structure within that group. Graph algorithms accomplish this by examining the overall nature of networks through their connections. With this approach, you can understand the topology of connected systems and model their processes.

There are three general buckets of question that indicate graph analytics and algorithms are warranted, as shown in Figure 1-9.

Below are a few types of challenges where graph algorithms are employed. Are your challenges similar?

In this chapter, we’ve looked at how data today is extremely connected. Analysis of group dynamics and relationships has robust scientific practices, yet those tools are not always commonplace in businesses. As we evaluate advanced analytics techniques, we should consider the nature of our data and whether we need to understand community attributes or predict complex behavior. If our data represents a network, we should avoid the temptation to reduce factors to an average. Instead, we should use tools that match our data and the insights we’re seeking.

In the next chapter, we’ll cover graph concepts and terminology.

In this chapter, we go into more detail on the terminology of graph algorithms. The basics of graph theory are explained with a focus on the concepts that are most relevant to a practitioner.

We’ll describe how graphs are represented and then explain the different types of graphs and their attributes. This will be important later as our graph’s characteristics will inform our algorithm choices and help interpret results. We’ll finish the chapter with the types of graph algorithms available to us.

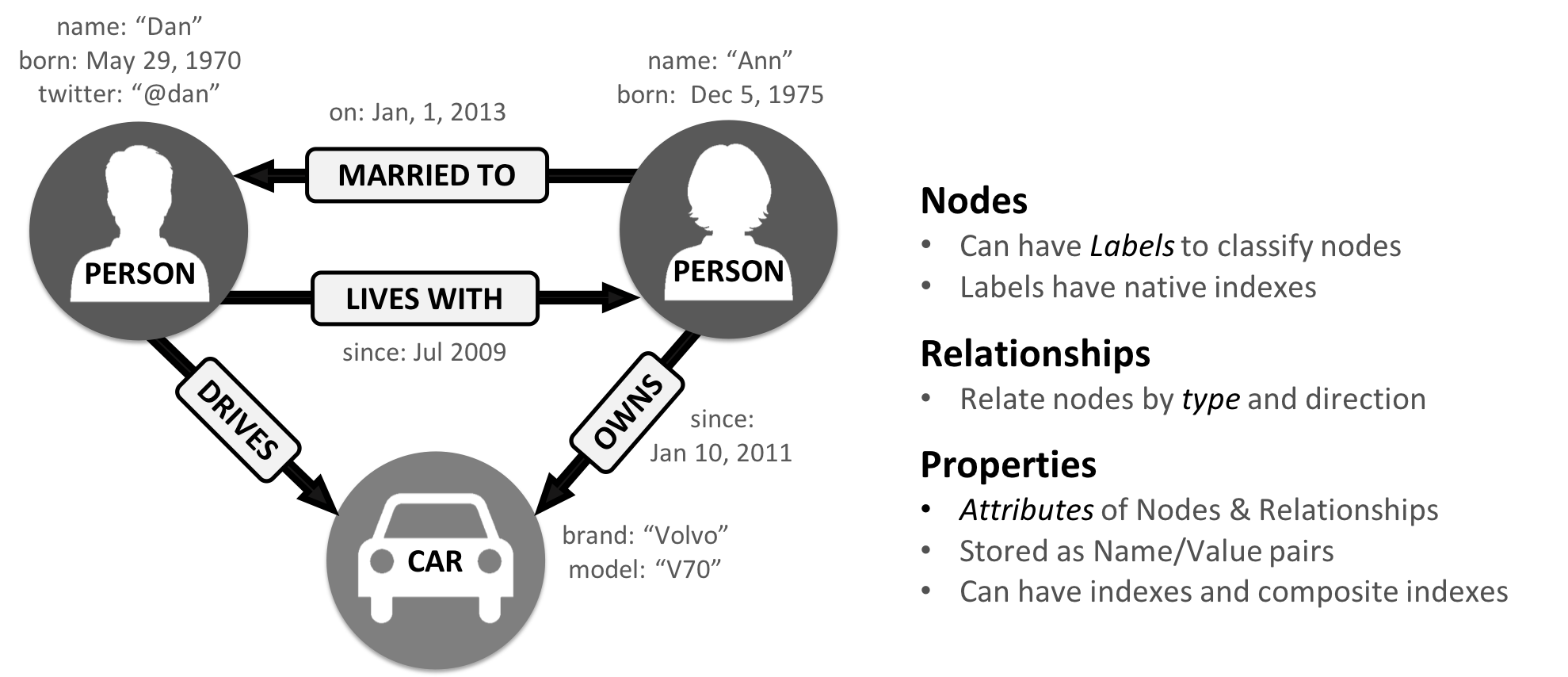

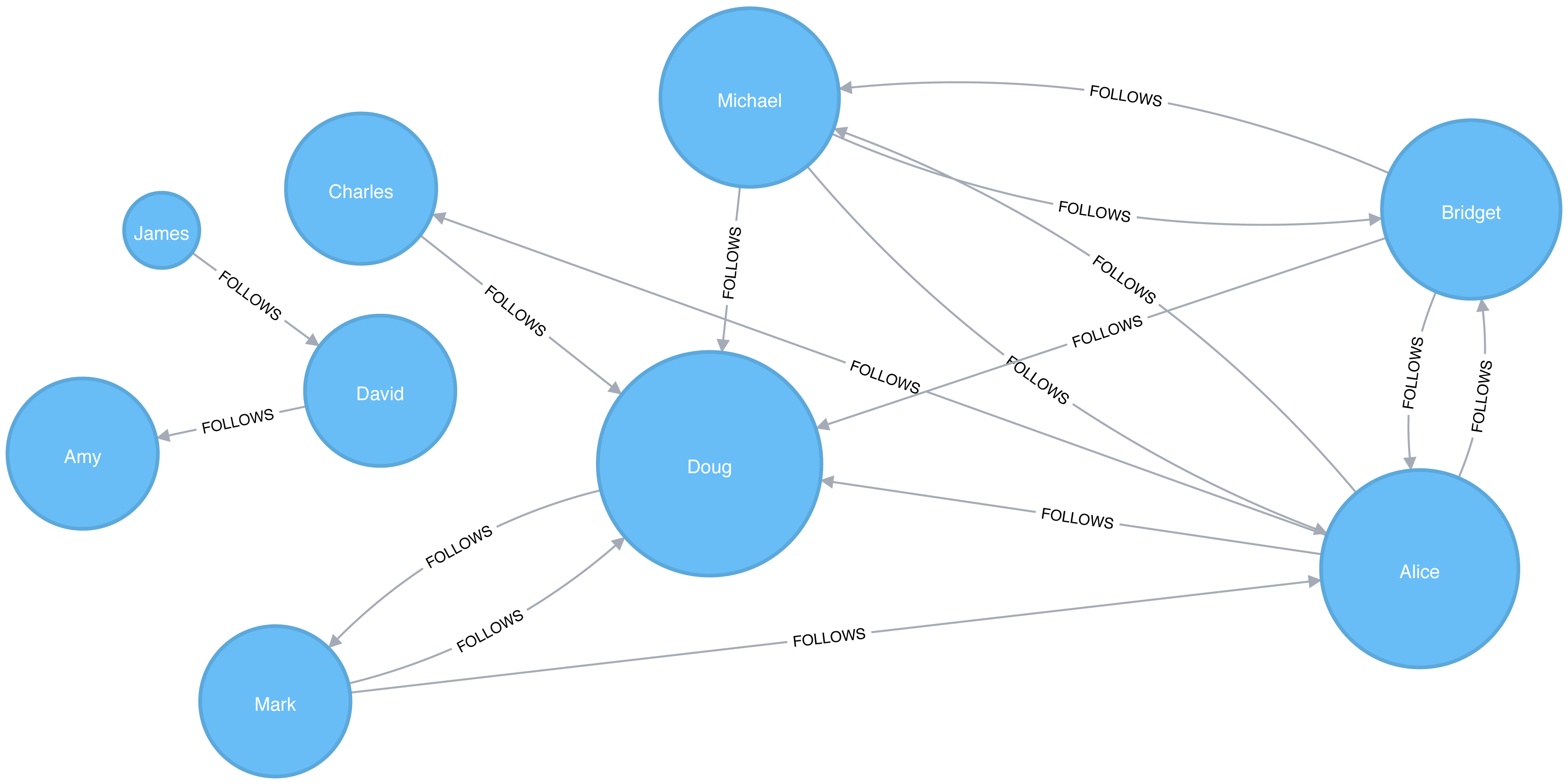

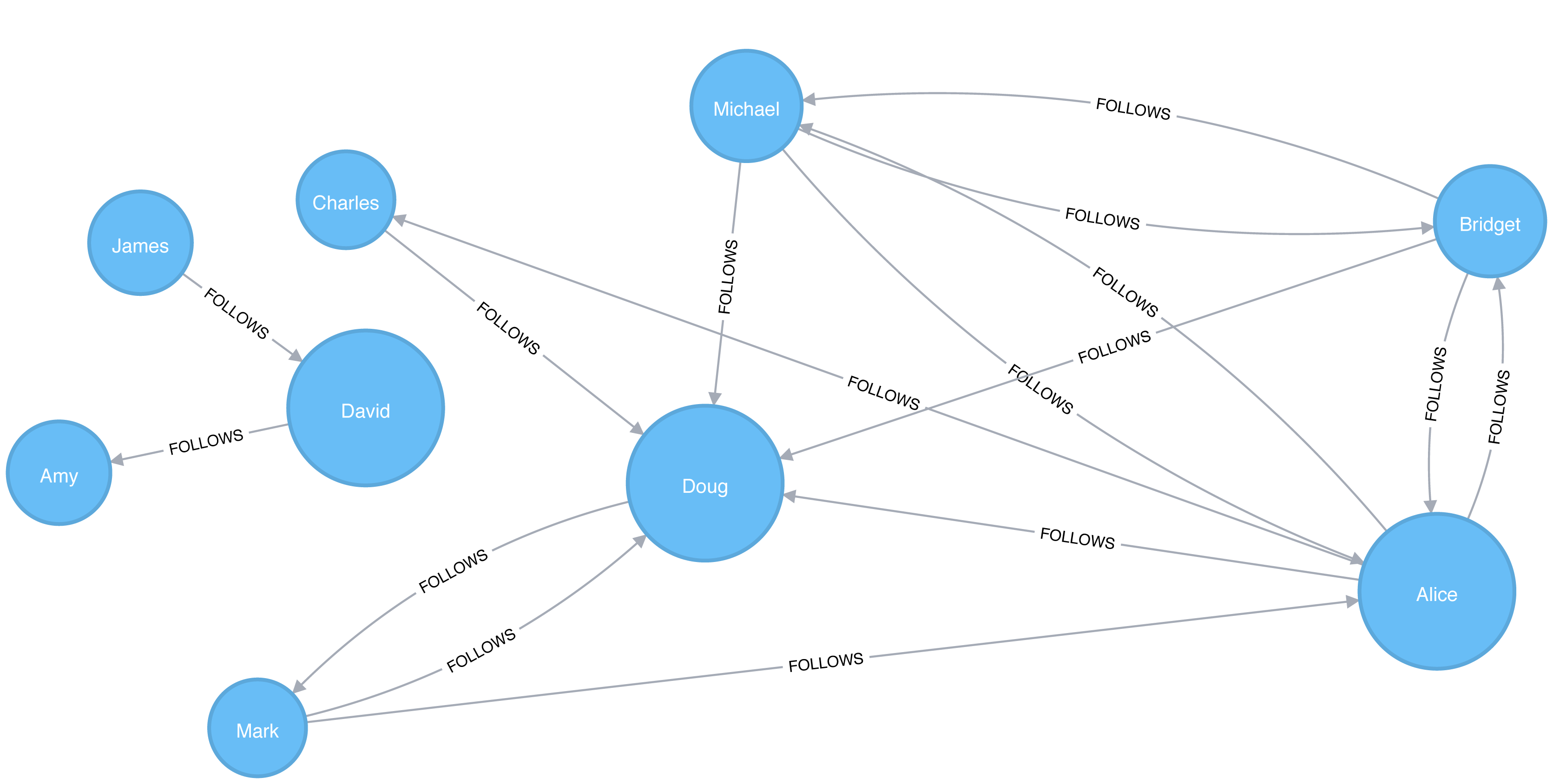

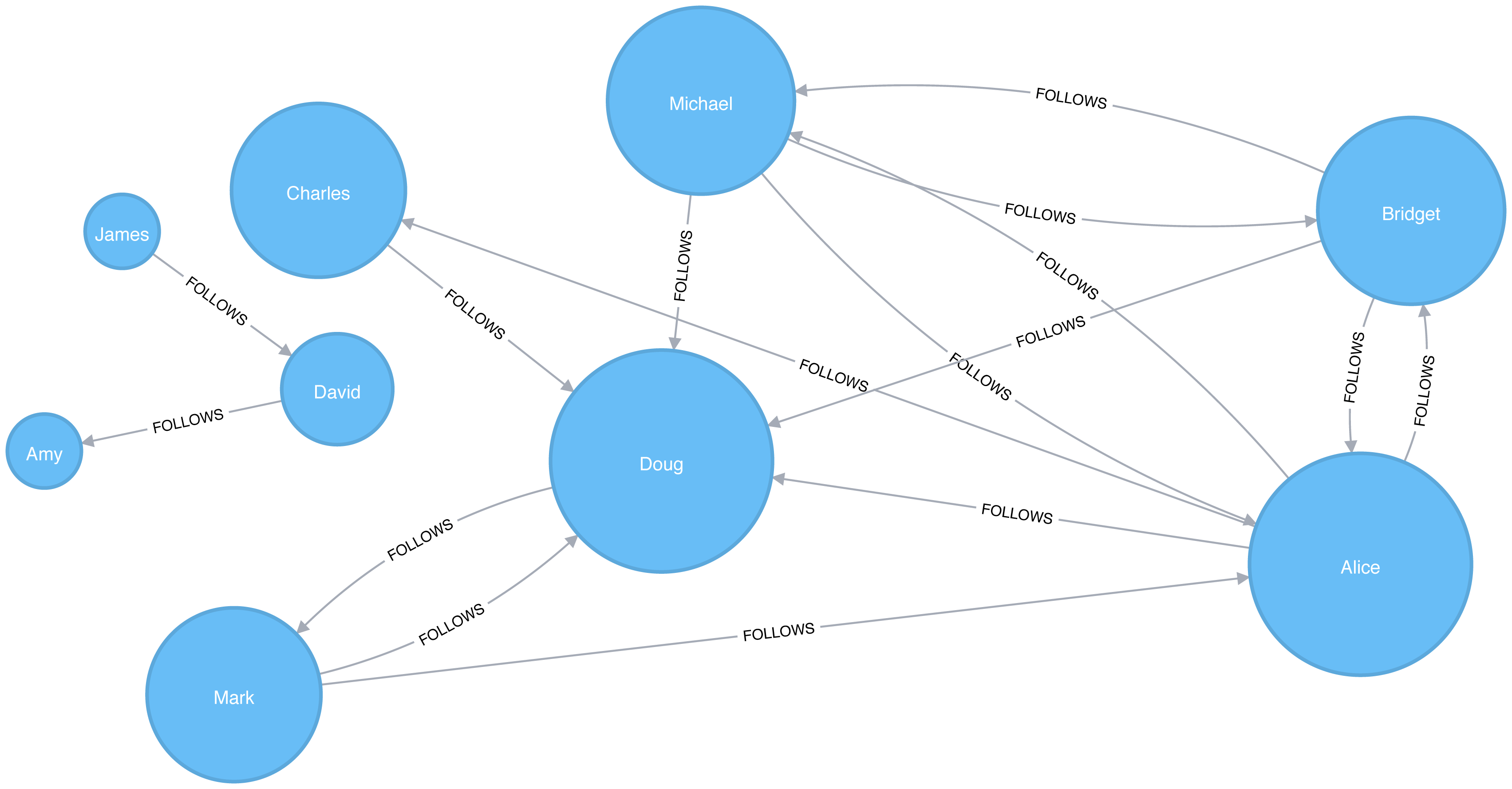

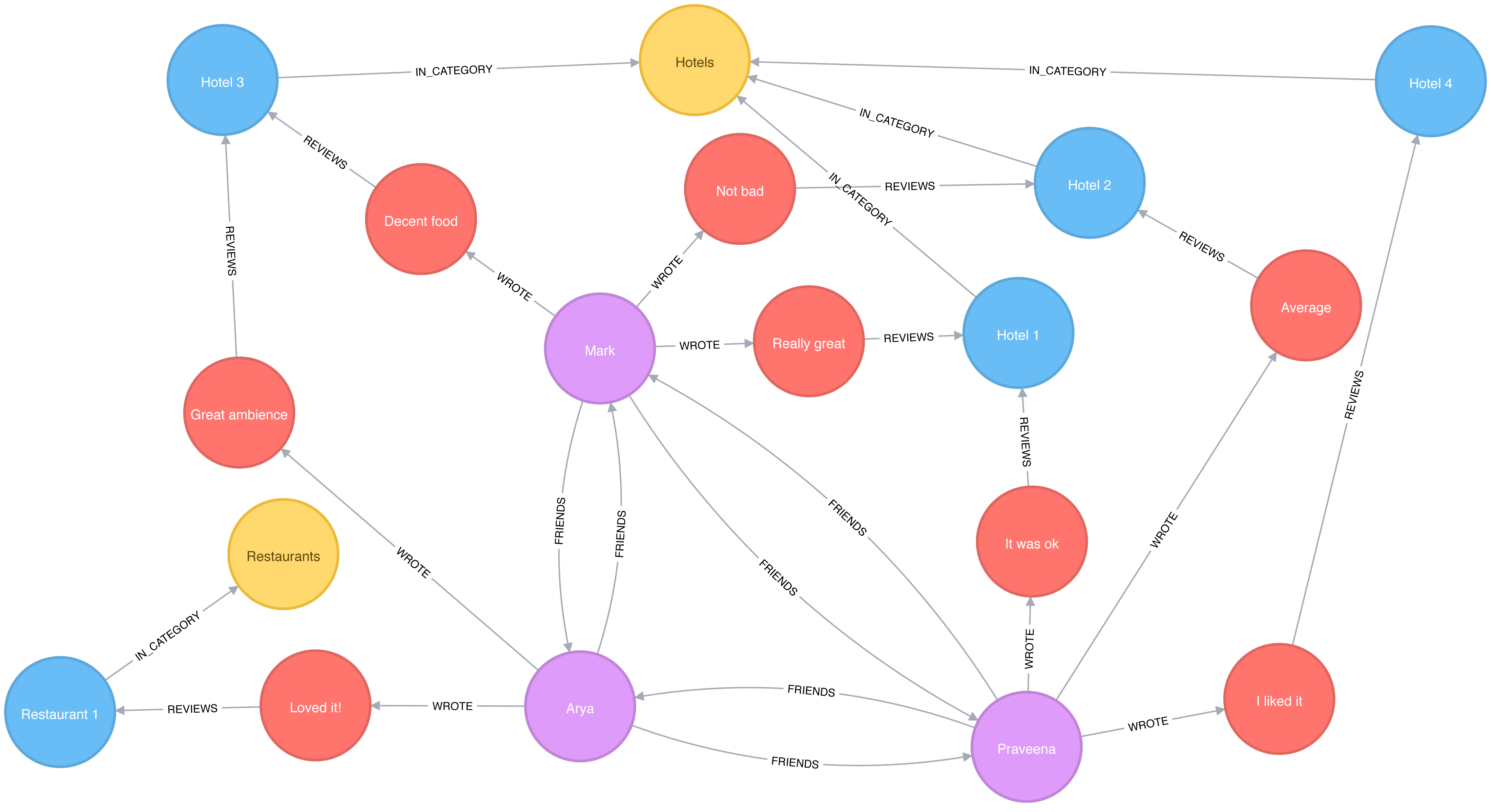

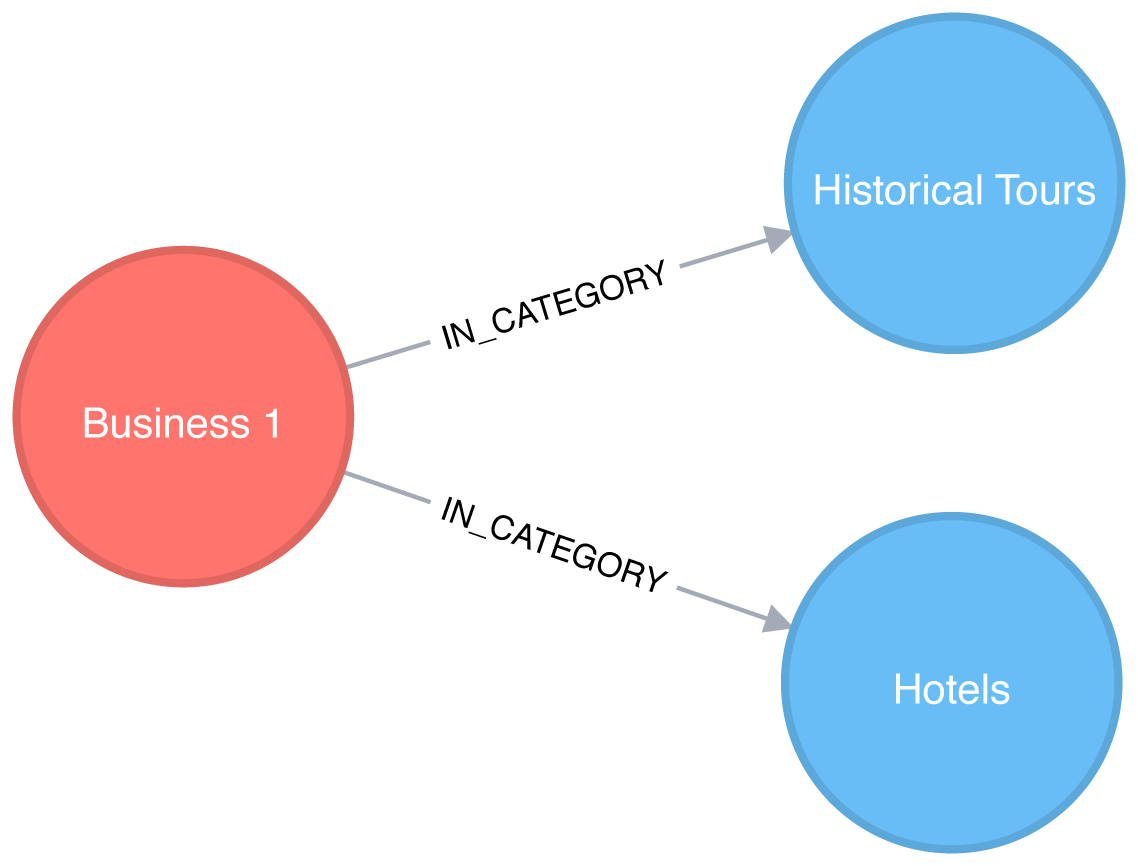

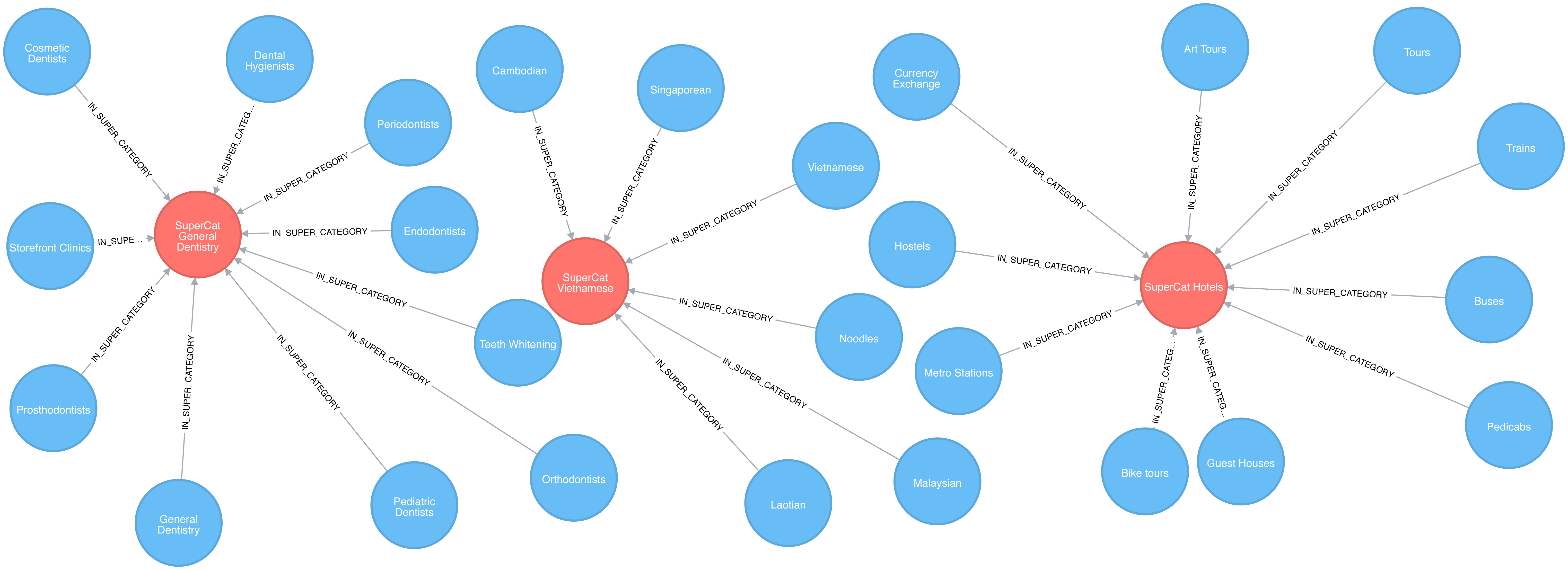

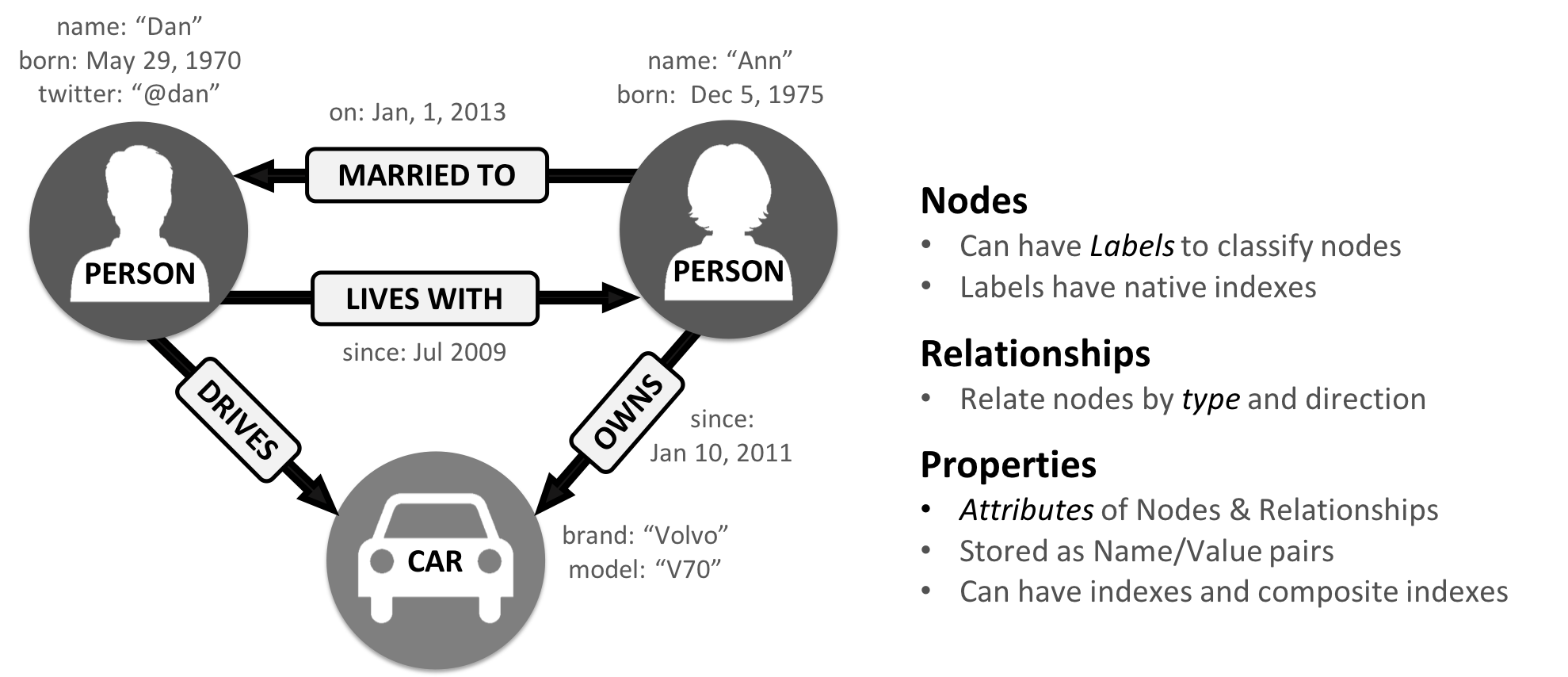

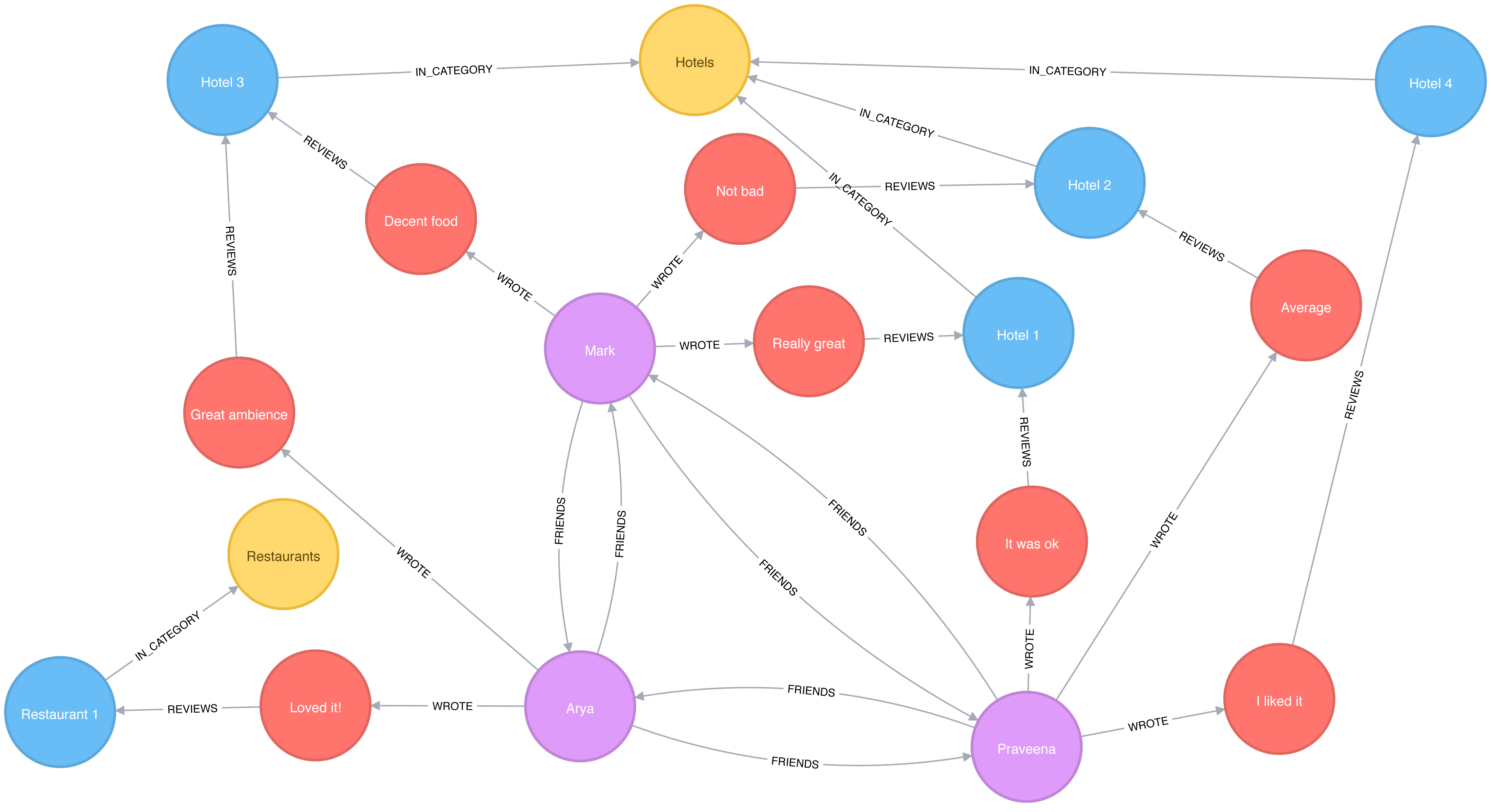

The labeled property graph is the dominant way of modeling graph data. An example can be seen in Figure 2-1.

A label marks a node as part of a group. Here we have two groups of nodes: Person and Car. (Although in classic graph theory, a label applies to a single node, it’s now commonly used to mean a node group.)

Relationships are classified based on relationship-type. Our example includes the relationship types of DRIVES, OWNS, LIVES_WITH, and MARRIED_TO.

Properties are synonymous with attributes and can contain a variety of data types from numbers and strings to spatial and temporal data. In Figure 2-1 , we assigned the properties as named value pairs where the name of the property comes first and then its value. For example, the Person node on the left has a property name: Dan and the MARRIED_TO relationship as a property of on: Jan, 1, 2013 .

A subgraph is a graph within a larger graph. Subgraphs are useful as a filter for our graph such as when we need a subset with particular characteristics for focused analysis.

A path is a group of nodes and their connecting relationships. An example of a simple path, based on Figure 2-1, could contain the nodes Dan, Ann and Car and the LIVES_WITH and OWNS relationships.

Graphs vary in type, shape and size as well the kind of attributes that can be used for analysis. In the next section, we’ll describe the kinds of graphs most suited for graph algorithms. Keep in mind that these explanations apply to graphs as well as subgraphs.

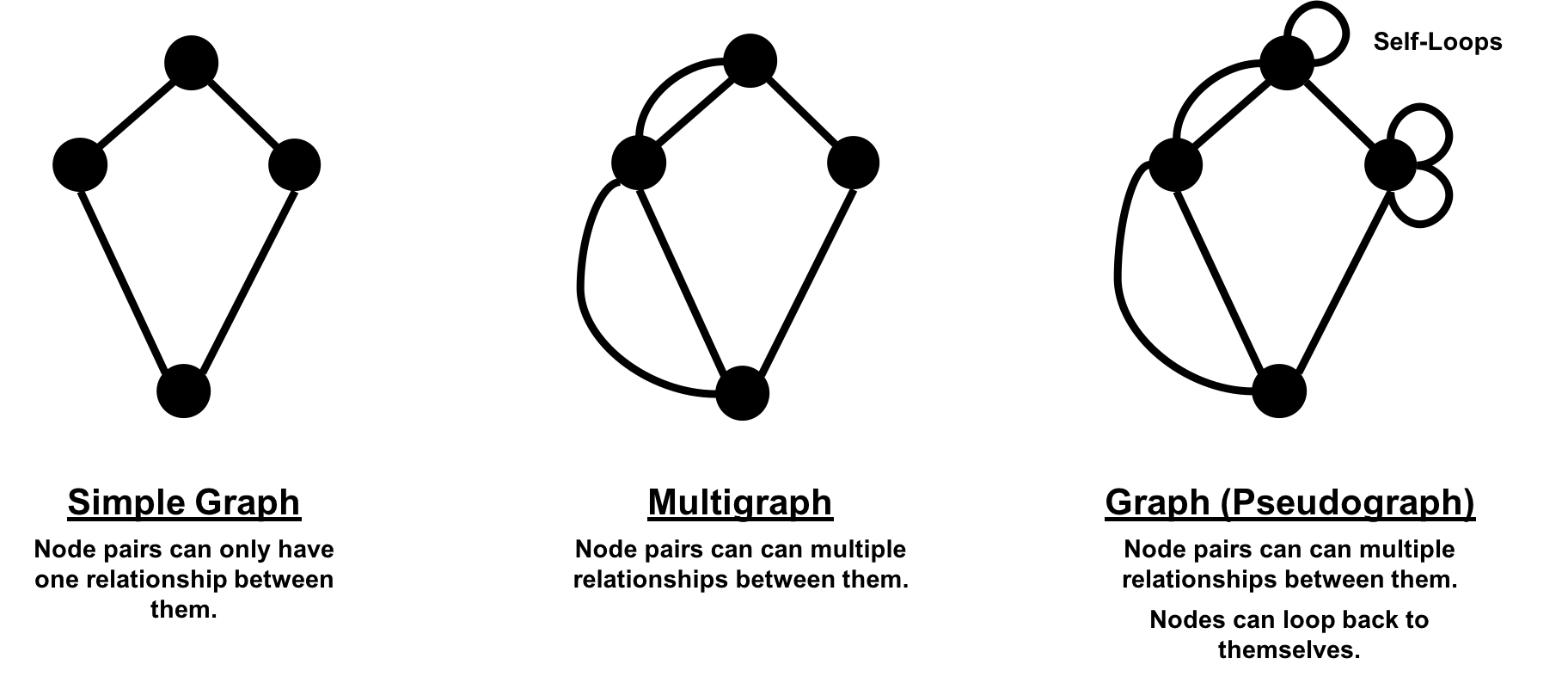

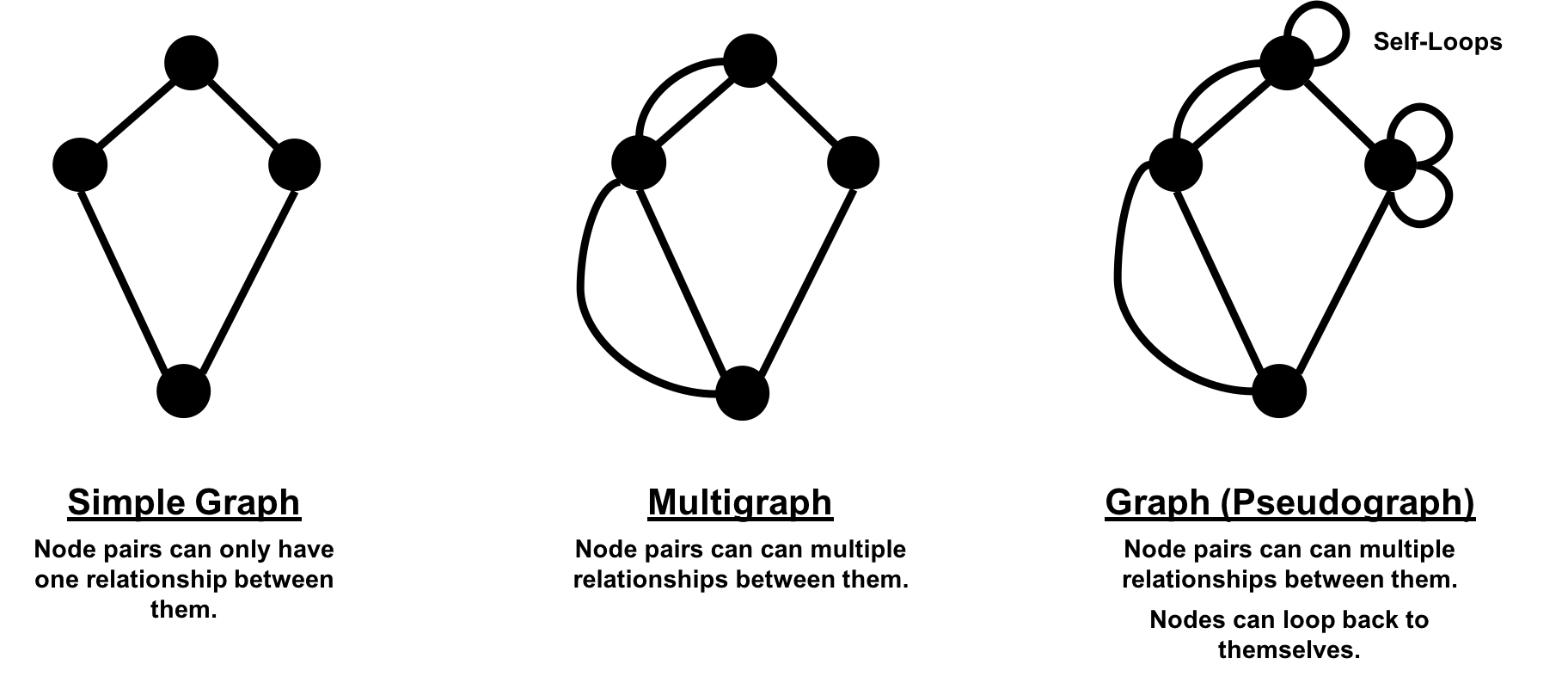

In classic graph theory, the term graph is equated with a simple (or strict) graph where nodes only have one relationship between them, as shown on the left side of Figure 2-2. Most real-world graphs, however, has many relationships between nodes and even self-referencing relationships. Today, the term graph is commonly used for all three graph types in Figure 2-2 and so we also use the term inclusively.

Graphs take on a variety of shapes. Figure 2-3 illustrates three representative network types:

These network types produce graphs with distinctive structures, distributions, and behaviors.

To get the most out of graph algorithms, it’s important to familiarize ourselves with the most characteristic graphs we’ll encounter.

| Graph Attributes | Key Factor | Algorithm Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Connected versus Disconnected | Whether or not there is a path between any two nodes in the graph, irrespective of distance. | Islands of nodes can cause unexpected behavior such as getting stuck in or failing to process disconnected components. |

| Weighted versus Unweighted | Whether there are (domain-specific) values on relationships or nodes. | Many algorithms expect weights and we’ll see significant differences in performance and results when ignored. |

| Directed versus Undirected | Whether or not relationships explicitly define a start and end node. |

Adds rich context to infer additional meaning. In some algorithms, you can explicitly set the use of one, both, or no direction. |

| Cyclic versus Acyclic | Paths start and end at the same node | Cyclic is common but algorithms must be careful (typically by storing traversal state) or cycles may prevent termination. Acyclic graphs (or spanning trees) are the basis for many graph algorithms. |

| Sparse versus Dense | Relationship to node ratio | Extremely dense or extremely sparsely connected graphs can cause divergent results. Data modeling may help, assuming the domain is not inherently dense or sparse. |

| Monopartite, Bipartite, and K-Partite | Nodes connect to only one other node type (users like movies) versus many other node types (users like users who like movies) | Helpful for creating relationships to analyze and projecting more useful graphs. |

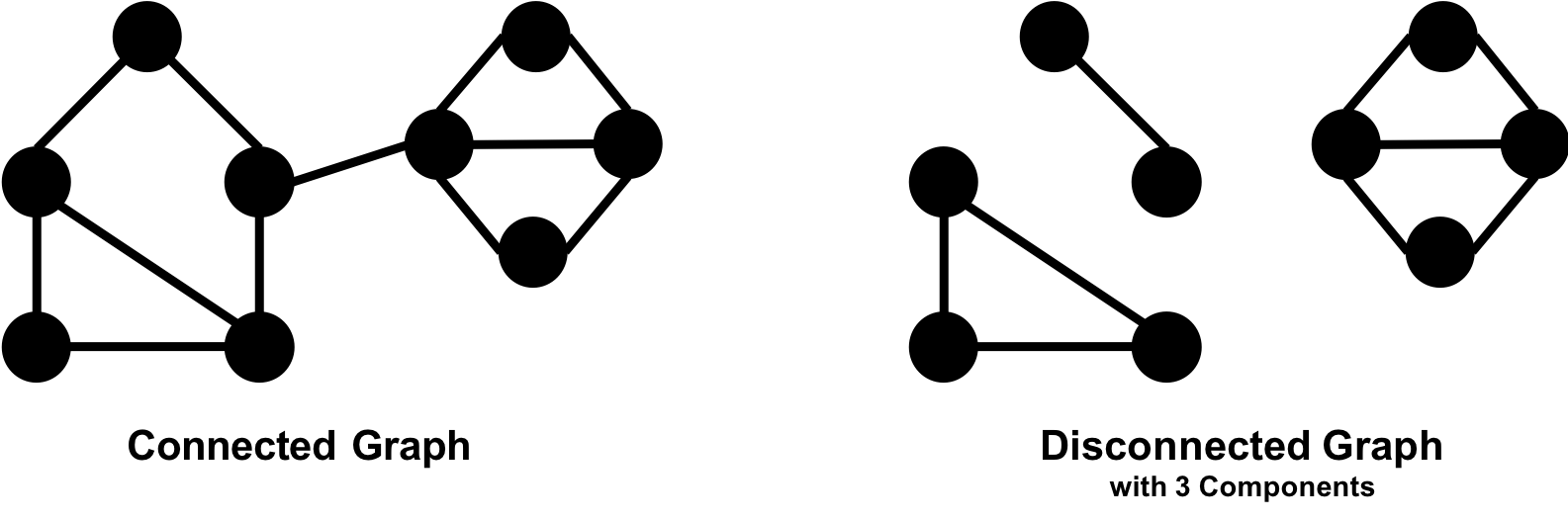

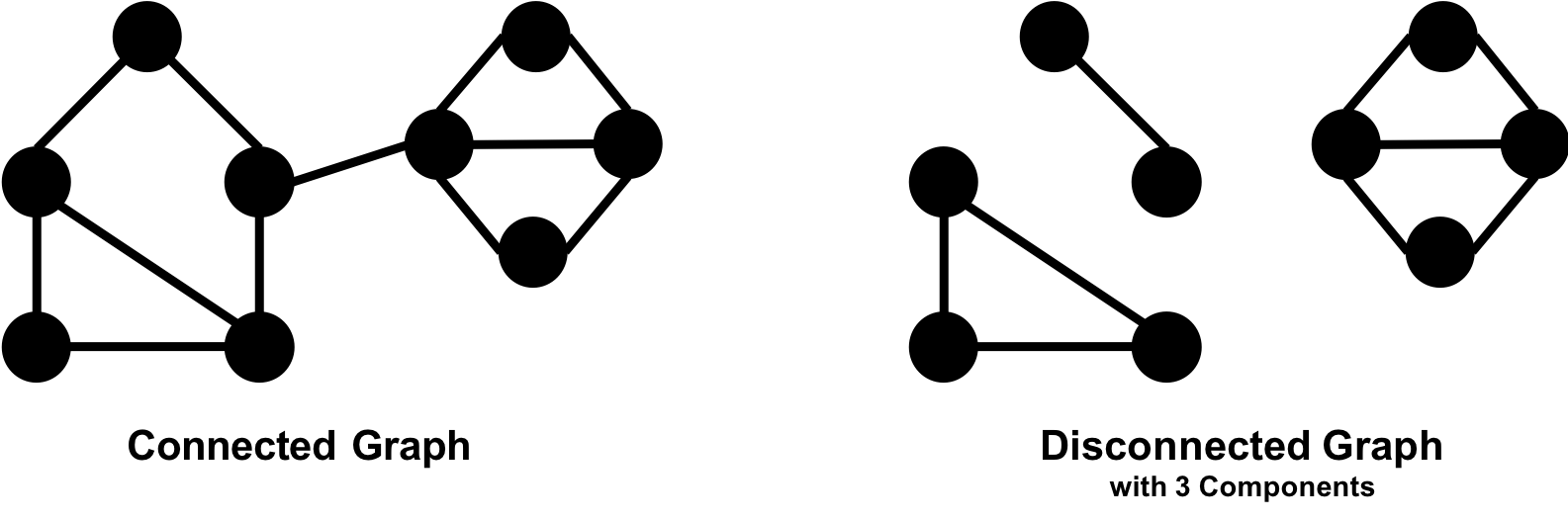

A graph is connected if there is a path from any node to every node and disconnected if there is not. If we have islands in our graph, it’s disconnected. If the nodes in those islands are connected, they are called components (or sometimes clusters) as shown in Figure 2-4.

Some algorithms struggle with disconnected graphs and can produce misleading results. If we have unexpected results, checking the structure of our graph is a good first step.

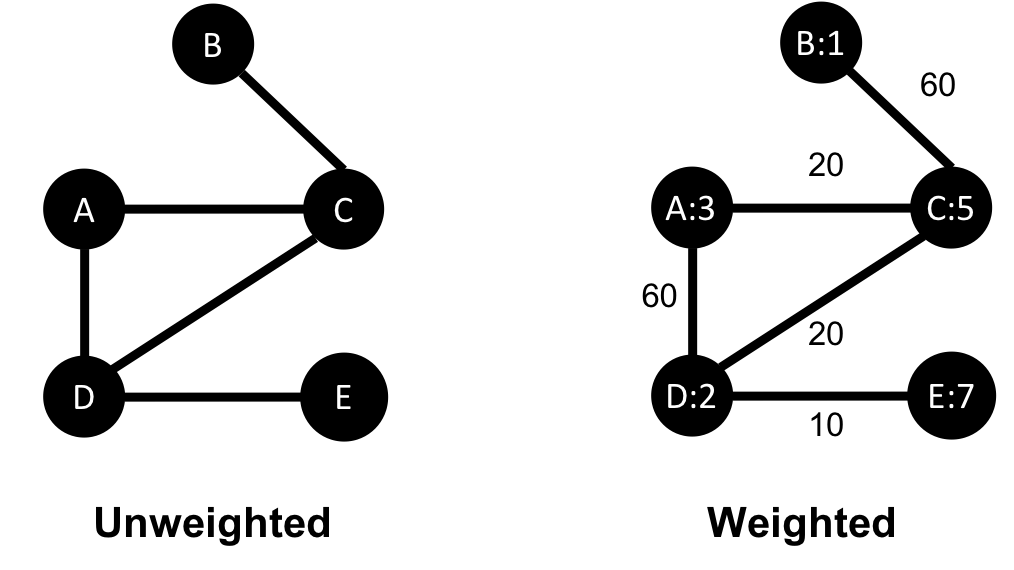

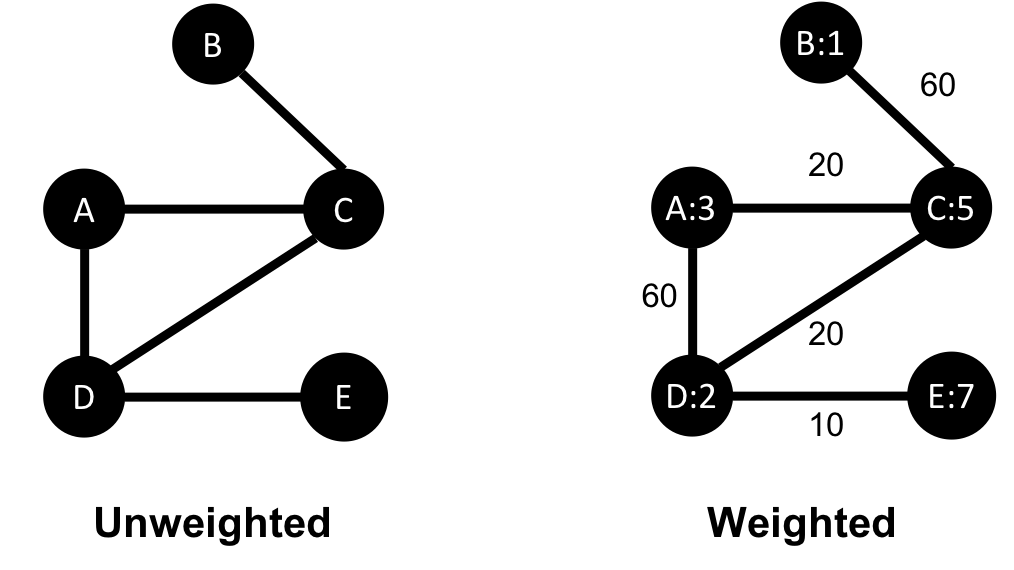

Unweighted graphs have no weight values assigned to their nodes or relationships. For weighted graphs, these values can represent a variety of measures such as cost, time, distance, capacity, or even a domain-specific prioritization. Figure 2-5 visualizes the difference.

Basic graph algorithms can use weights for processing as a representation for the strength or value of relationships. Many algorithms compute metrics which then can be used as weights for follow-up processing. Some algorithms update weight values as they proceed to find cumulative totals, lowest values, or optimums.

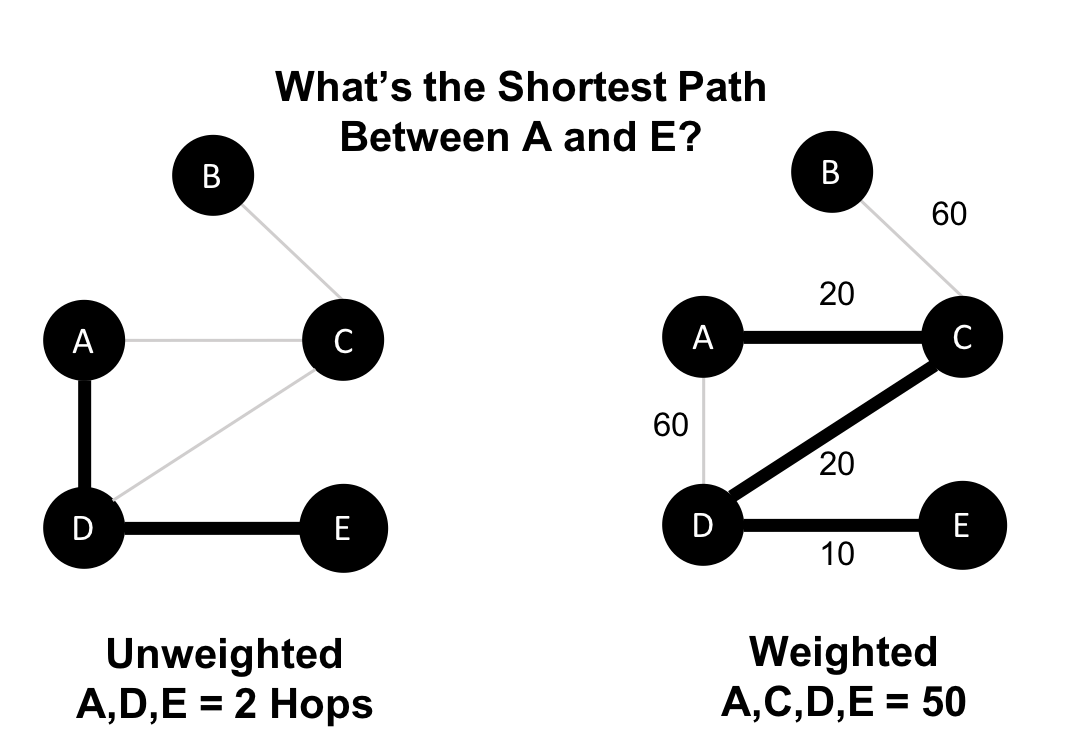

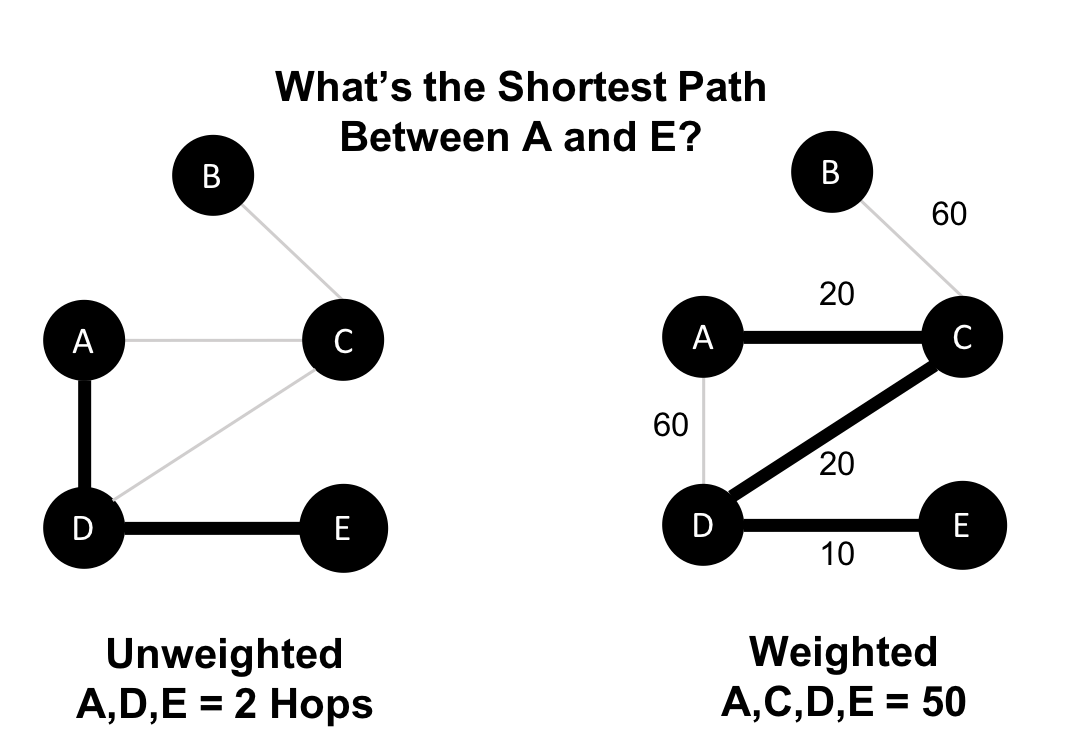

The classic use for weighted graphs is in pathfinding algorithms. Such algorithms underpin the mapping applications on our phones and compute the shortest/cheapest/fastest transport routes between locations. For example, Figure 2-6 uses two different methods of computing the shortest route.

Without weights, our shortest route is calculated in terms of the number of relationships (commonly called hops). A and E have a 2 hop shortest path, which indicates only 1 city (D) between them. However, the shortest weighted path from A to E takes us from A to C to D to E. If weights represent a physical distance in kilometers the total distance would be 50 km. In this case, the shortest path in terms of the number of hops would equate to a longer physical route of 70 km.

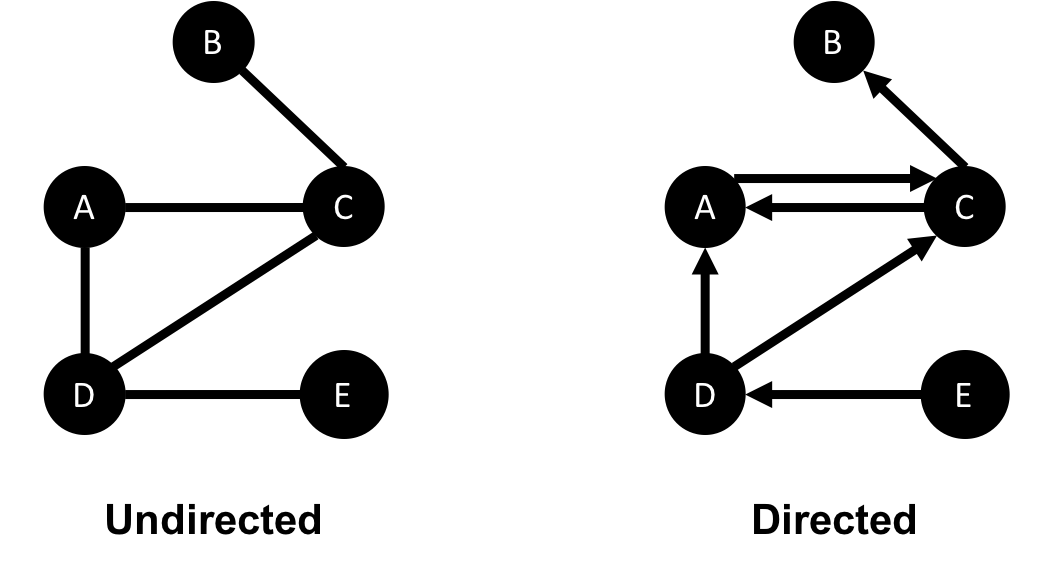

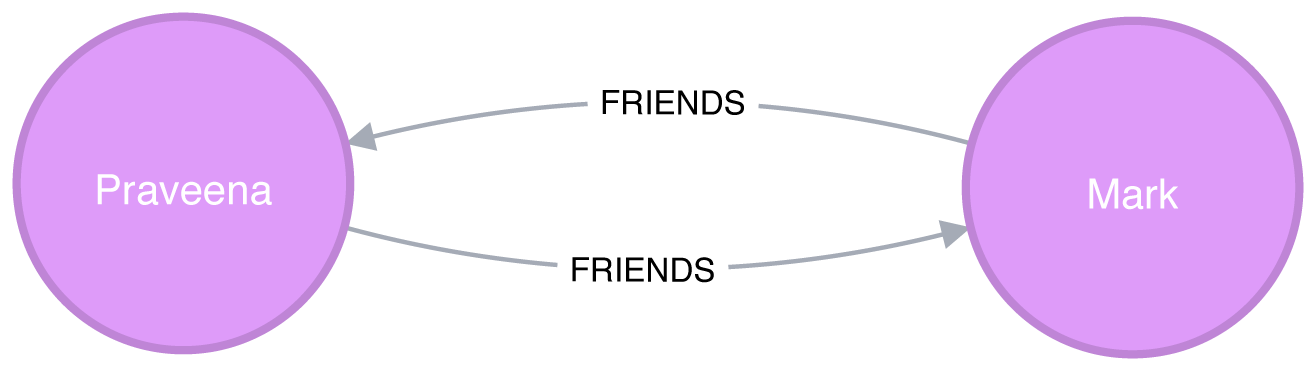

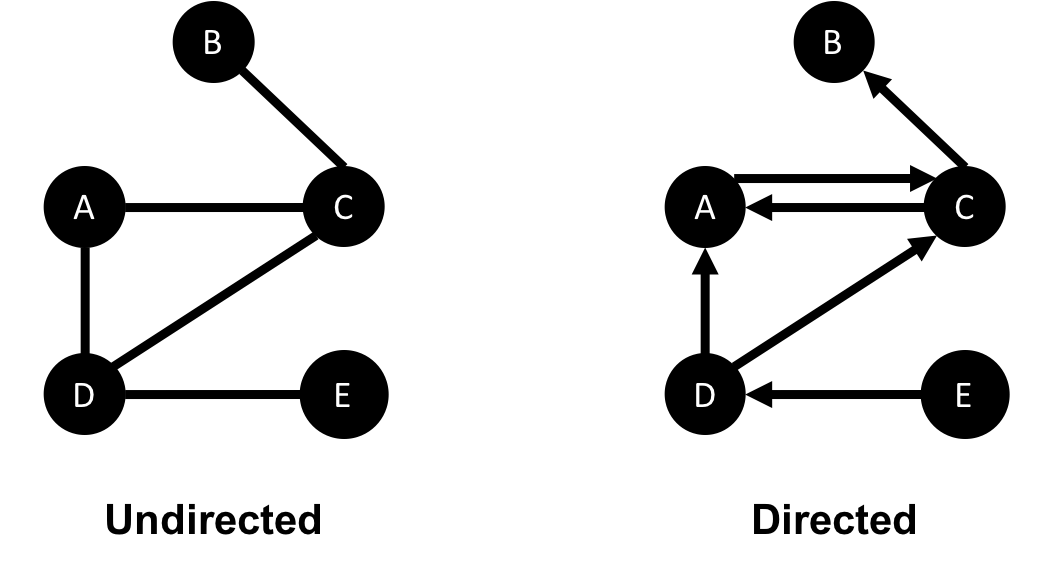

In an undirected graph, relationships are considered bi-directional, such as commonly used for friendships. In a directed graph, relationships have a specific direction. Relationships pointing to a node are referred to as in-links and, unsurprisingly, out-links are those originating from a node.

Direction adds another dimension of information. Relationships of the same type but in opposing directions carry different semantic meaning, as it expresses a dependency or indicates a flow. This may then be used as an indicator of credibility or group strength. Personal preferences and social relations are expressed very well with direction.

For example, if we assumed in Figure 2-7 that the directed graph was a network of students and the relationships were “likes” then we’d calculate that A and C are more popular.

Road networks illustrate why we might want to use both types of graphs. For example, highways between cities are often traveled in both directions. However, within cities, some roads are one-way streets. (The same is true for some information flows!)

We get different results running algorithms in an undirected fashion compared to directed. If we want an undirected graph, for example, we would assume highways or friendship always go both ways.

If we reimagine Figure 2-7 as a directed road network, you can drive to A from C and D but you can only leave through C. Furthermore if there were no relationships from A to C, that would indicate a dead-end. Perhaps that’s less likely for a one-way road network but not for a process or a webpage.

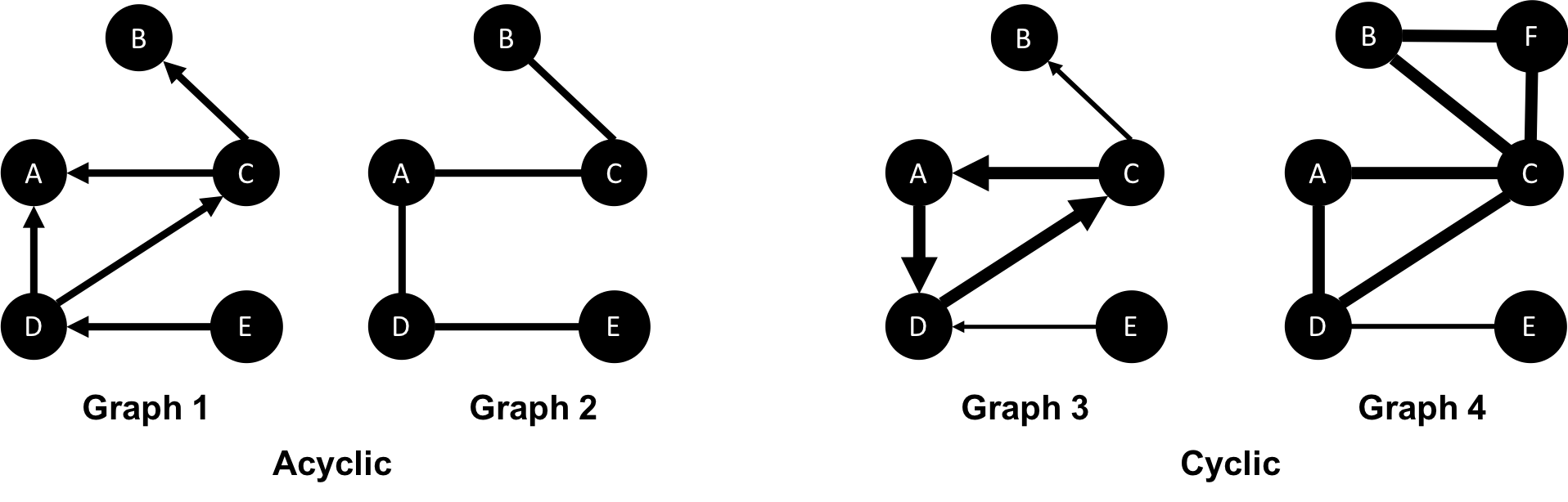

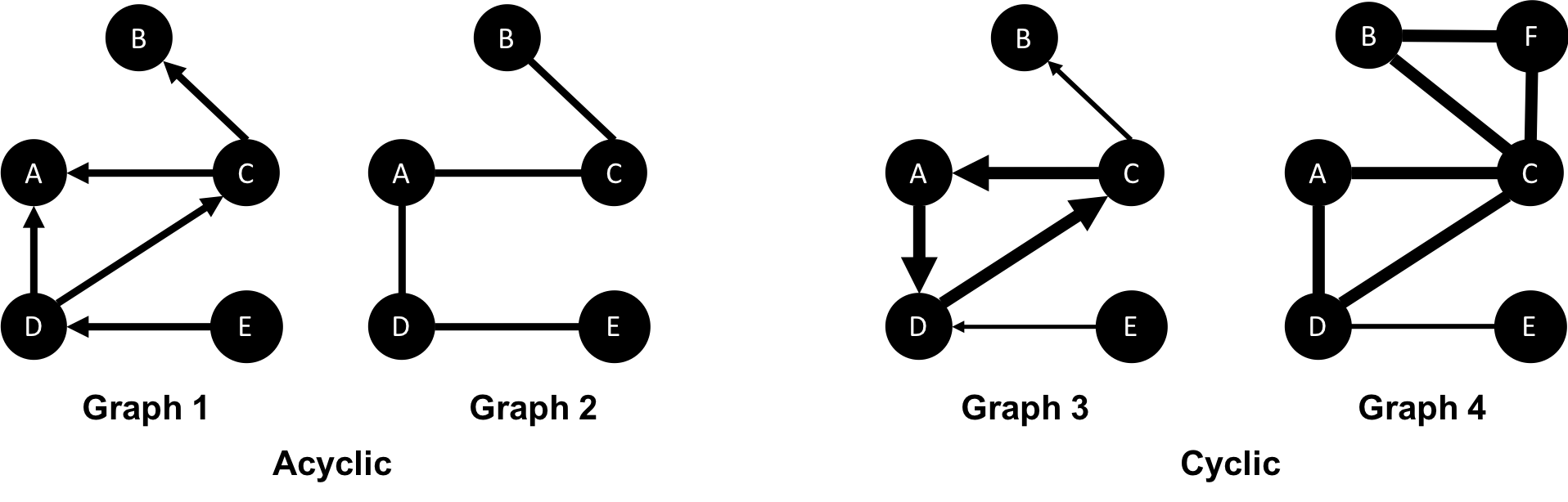

In graph theory, cycles are paths through relationships and nodes which start and end at the same node. An acyclic graph has no such cycles. As shown in Figure 2-8, directed and undirected graphs can have cycles but when directed, paths follow the relationship direction. A directed acyclic graph (DAG), shown in Graph 1, will by definition always have dead ends (leaf nodes).

Graphs 1 and 2 have no cycles as there’s no way to start and end on the same node without repeating a relationship. You might remember from chapter 1 that not repeating relationships was the Königsberg bridges problem that started graph theory! Graph 3 in Figure 2-8 shows a simple cycle with no repeated nodes of A-D-C-A. In graph 4, the undirected cyclic graph has been made more interesting by adding a node and relationship. There’s now a closed cycle with a repeated node (C), following B-F-C-D-A-C-B. There are actually multiple cycles in graph 4.

Cycles are common and we sometimes need to convert cyclic graphs to acyclic graphs (by cutting relationships) to eliminate processing problems. Directed acyclic graphs naturally arise in scheduling, genealogy, and version histories.

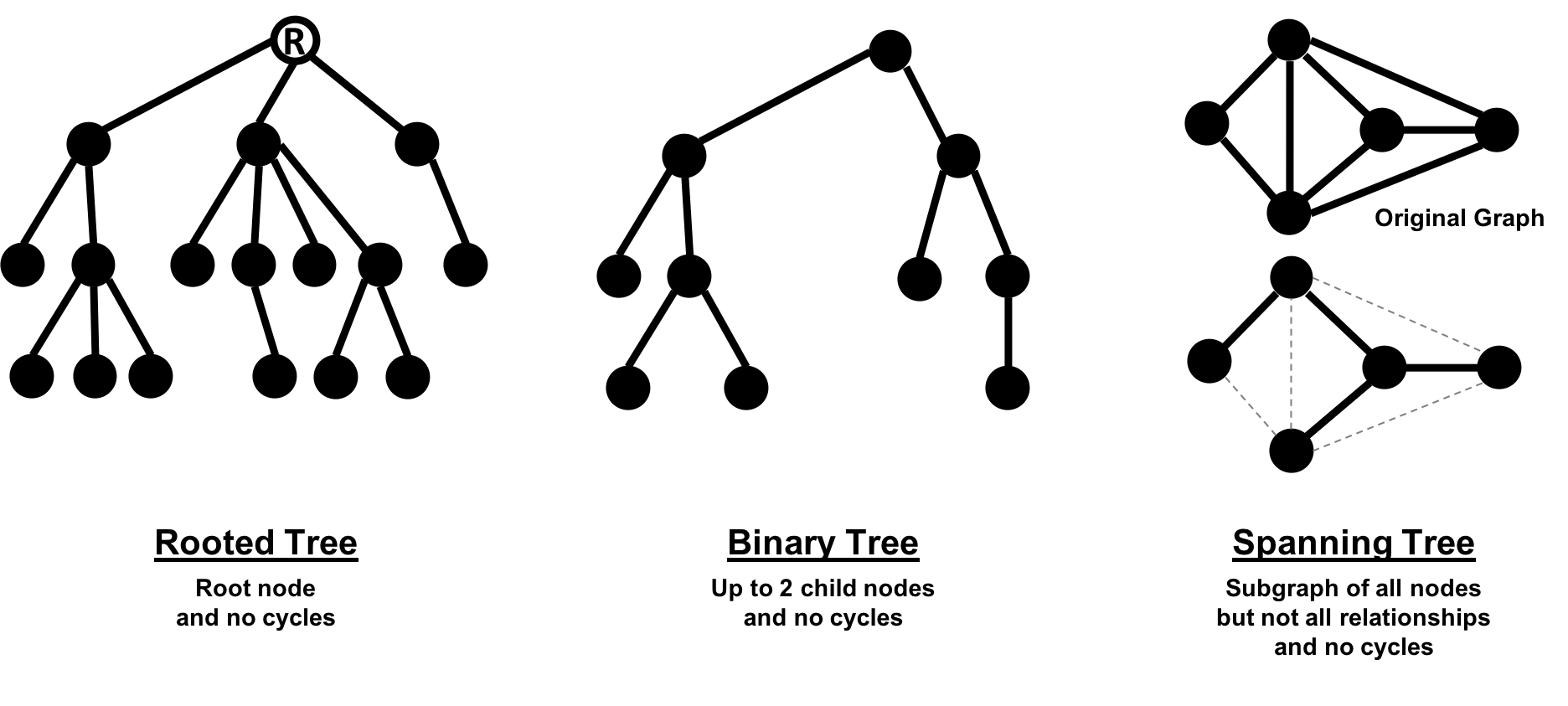

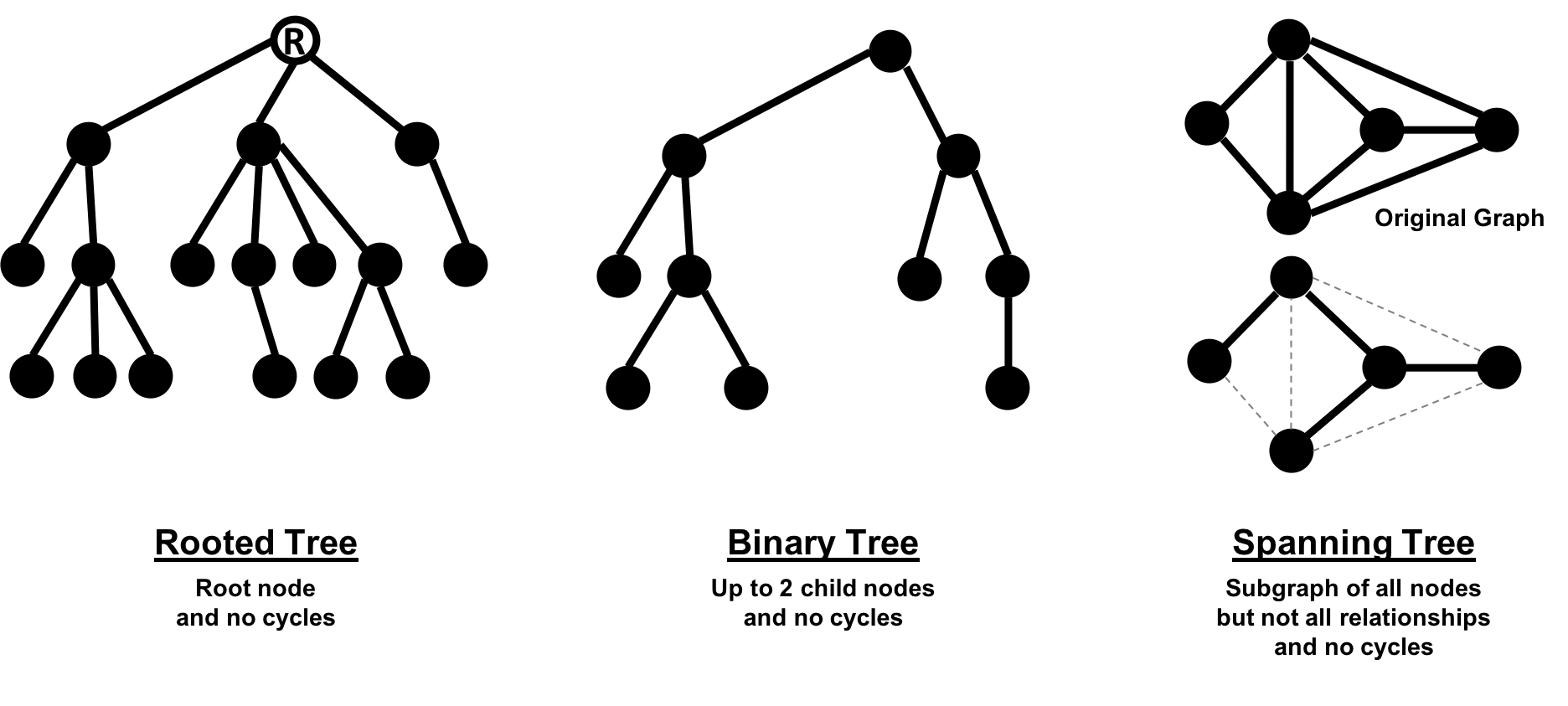

In classic graph theory, an acyclic graph that is undirected is called a tree. While, in computer science, trees can also be directed. A more inclusive definition would be a graph where any two nodes are connected by only one path. Trees are significant for understanding graph structures and many algorithms. They play a key role in designing networks, data structures, and search optimizations to improve categorization or organizational hierarchies.

Much has been written about trees and their variations, Figure 2-9 illustrates the common trees that we’re likely to encounter.

Of these variations, spanning trees are the most relevant for this book. A spanning tree is a subgraph, that includes all the nodes of a larger acyclic graph but not all the relationships. A minimum spanning tree connects all the nodes of a graph with the either the least number of hops or least weighted paths.

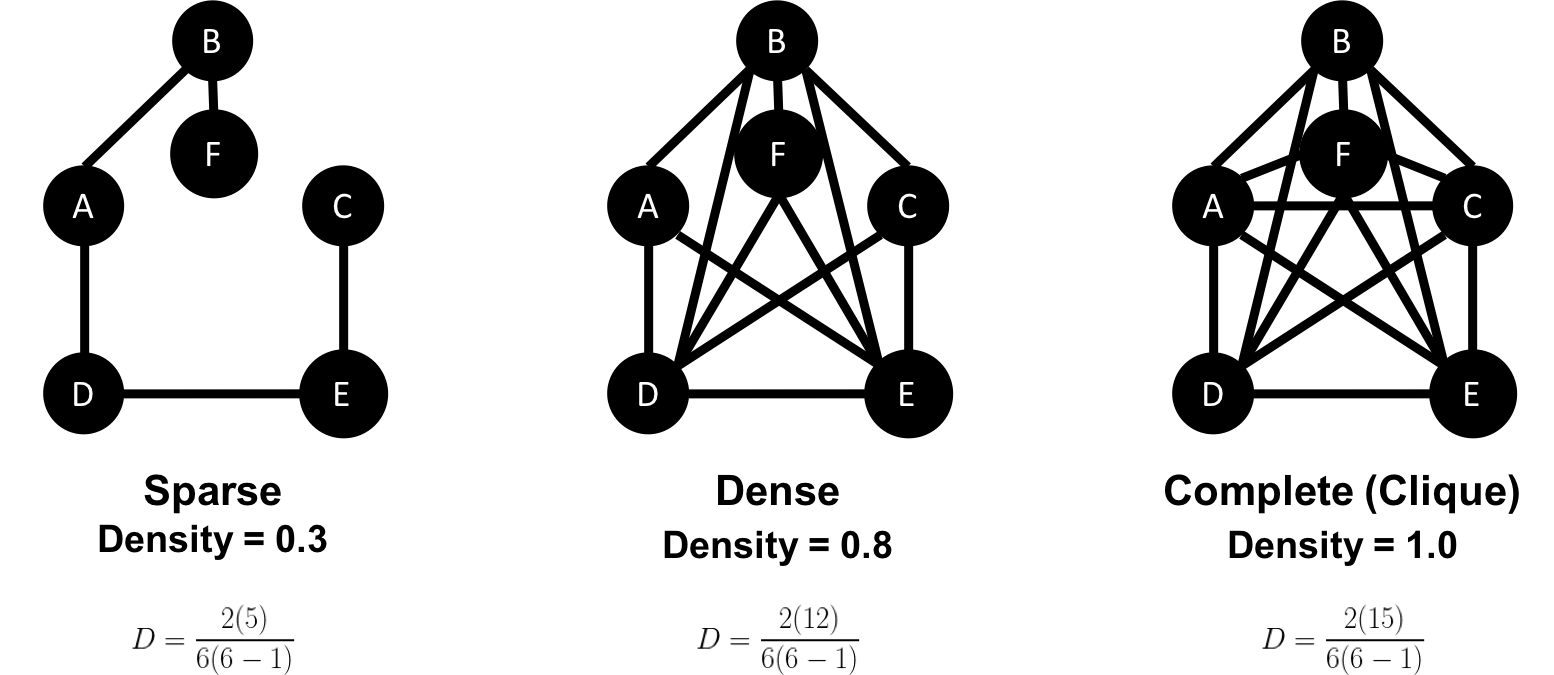

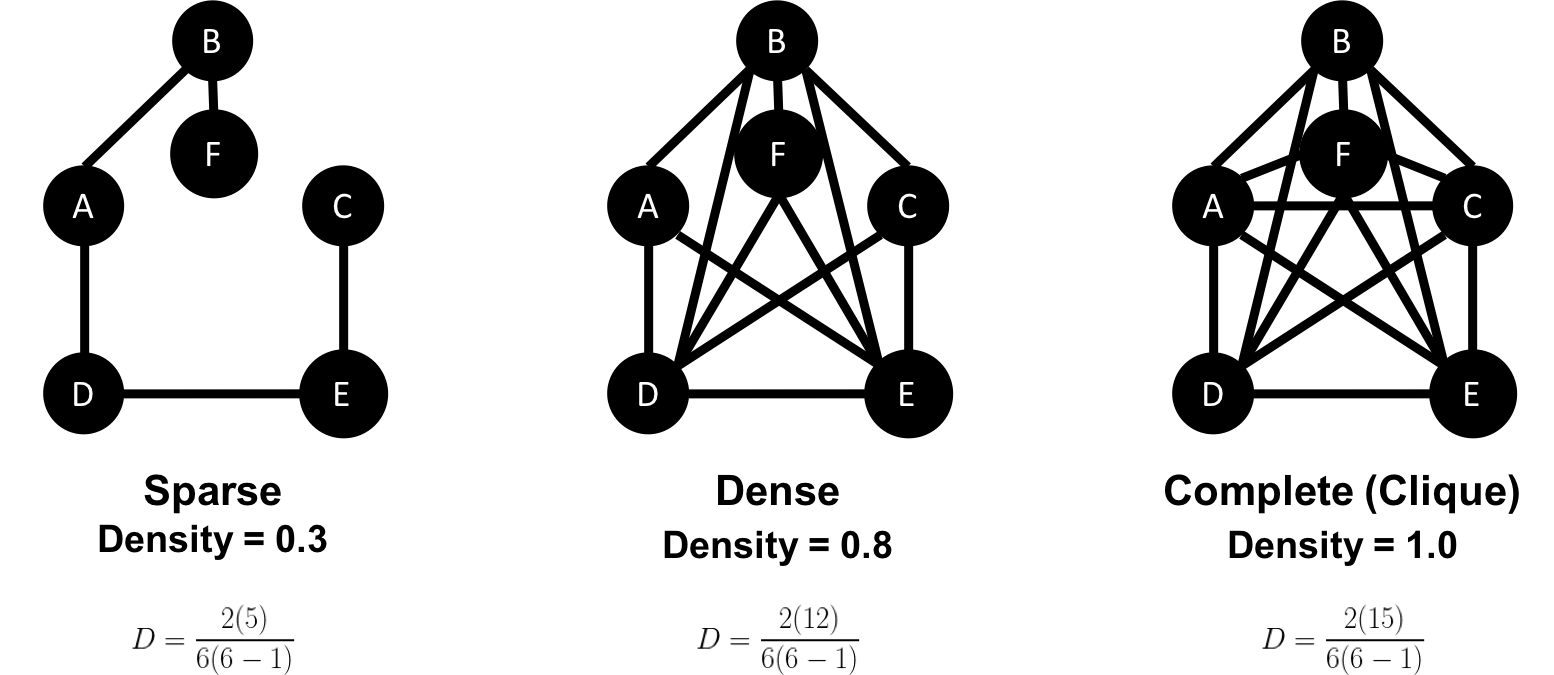

The sparsity of a graph is based on the number of relationships it has compared to the maximum possible number of relationships, which would occur if there was a relationship between every pair of nodes. A graph where every node has a relationship with every other node is called a complete graph, or a clique for components. For instance, if all my friends knew each other, that would be a clique.

The maximum density of a graph is calculated with the formula,[ where N is the number of nodes. Any graph that approaches the maximum density is considered dense, although there is no strict definition. In Figure 2-10 we can see three measures of density for undirected graphs which uses the formula, where R is the number of relationships.

Most graphs based on real networks tend toward sparseness with an approximately linear correlation of total nodes to total relationships. This is especially the case where physical elements come into play such as the practical limitations to how many wires, pipes, roads, or friendships you can join at one point.

Some algorithms will return nonsensical results when executed on very sparse or dense graphs. If a graph is very sparse there may not be enough relationships for algorithms to compute useful results. Alternatively, very densely connected nodes don’t add much additional information since they are so highly connected. Dense nodes may also skew some results or add computational complexity.

Most networks contain data with multiple node and relationship types. Graph algorithms, however, frequently consider only one node type and one relationship type. Graphs with one one node type and relationship type are sometimes referred to as monopartite

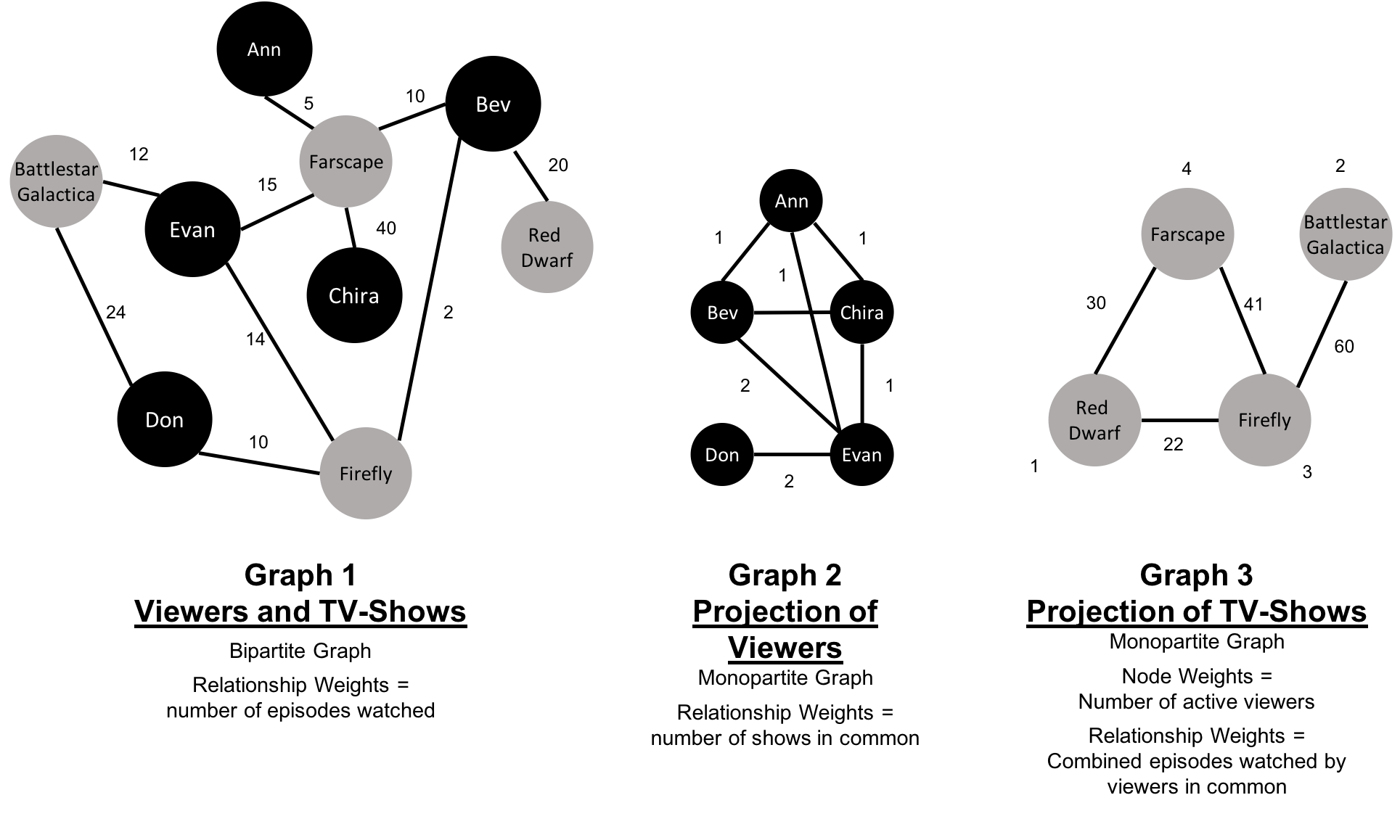

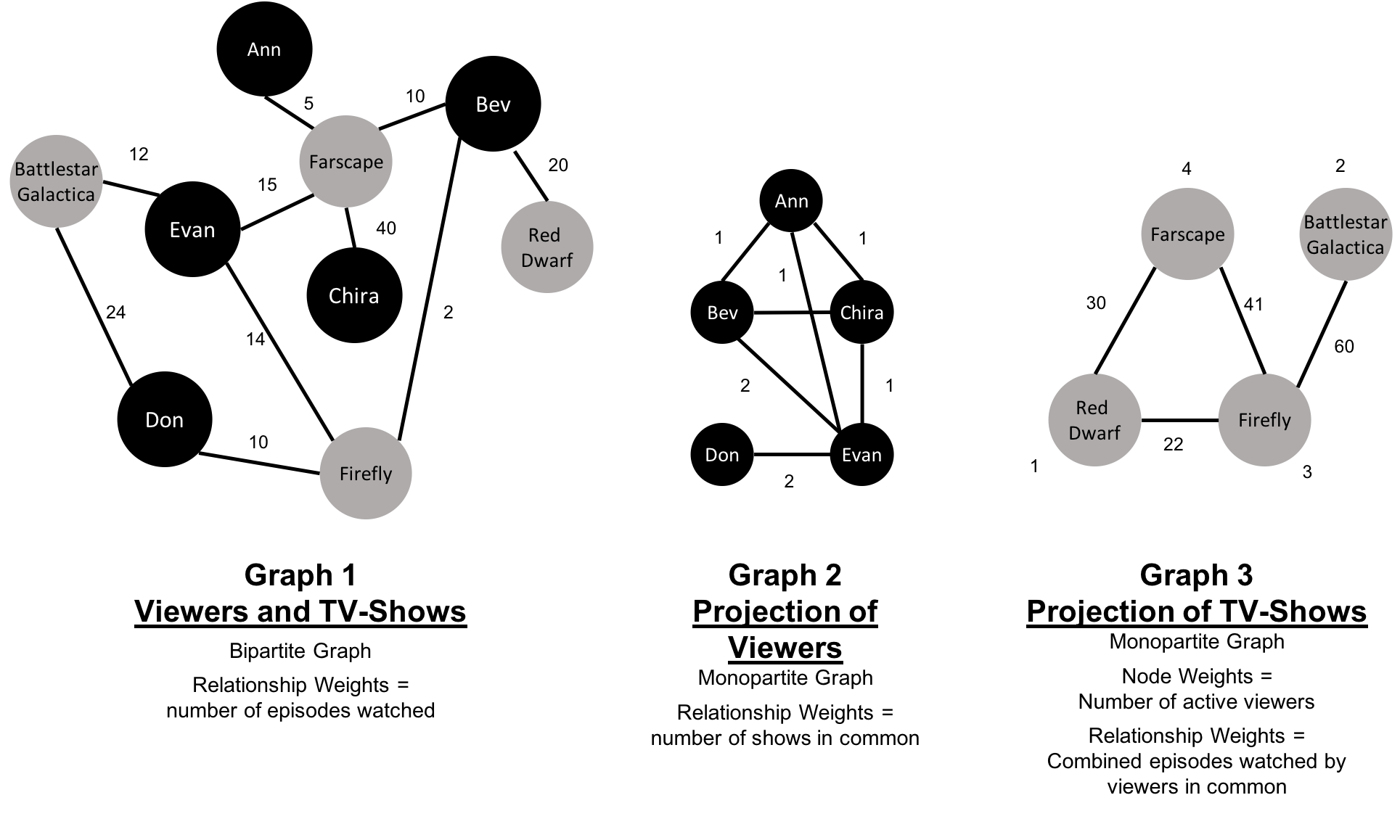

A bipartite graph is a graph whose nodes can be divided into two sets, such that relationships only connect a node from one set to a node from a different set. Figure 2-11 shows an example of such a graph. It has 2 sets of nodes: a viewer set and a TV-show set. There are only relationships between the two sets and no intra-set connections. In other words in Graph 1, TV shows are only related to viewers, not other TV shows and viewers are likewise not directly linked to other viewers.

Starting from our bipartite graph of viewers and TV-shows we created two monopartite projections: Graph 2 of viewer connections based on movies in common and Graph 3 of TV shows based on viewers in common. We can also filter based on relationship type such as watched, rated, or reviewed.

Projecting monopartite graphs with inferred connections is an important part of graph analysis. These type of projections help uncover indirect relationships and qualities. For example, in Figure 2-11 Graph 2, we’ve weighted relationship in the TV show graph by the aggregated views by viewers common. In this case, Bev and Ann have watched only one TV show in common whereas Bev and Evan have two shows in common. This, or other metrics such as similarity, can be used to infer meaning between activities like watching Battlestar Galactica and Firefly. That can inform our recommendation for someone similar to Evan who, in Figure 2-11, just finished watching the last episode of Firefly.

K-partite graphs reference the number of node-types our data has (k). For example, if we have 3 node types, we’d have a tripartite graph. This just extends bipartite and monopartite concepts to account for more node types. Many real-world graphs, especially knowledge graphs, have a large value for k, as they combine many different concepts and types of information. An example of using a larger number of node-types is creating new recipes by mapping a recipe set to an ingredient set to a chemical compound—and then deducing new mixes that connect popular preferences. We could also reduce the number of nodes-types by generalization such as treating many forms of a node, like spinach or collards, as just as a “leafy green.”

Now that we’ve reviewed the types of graphs we’re most likely to work with, let’s learn about the types of graph algorithms we can execute on those graphs.

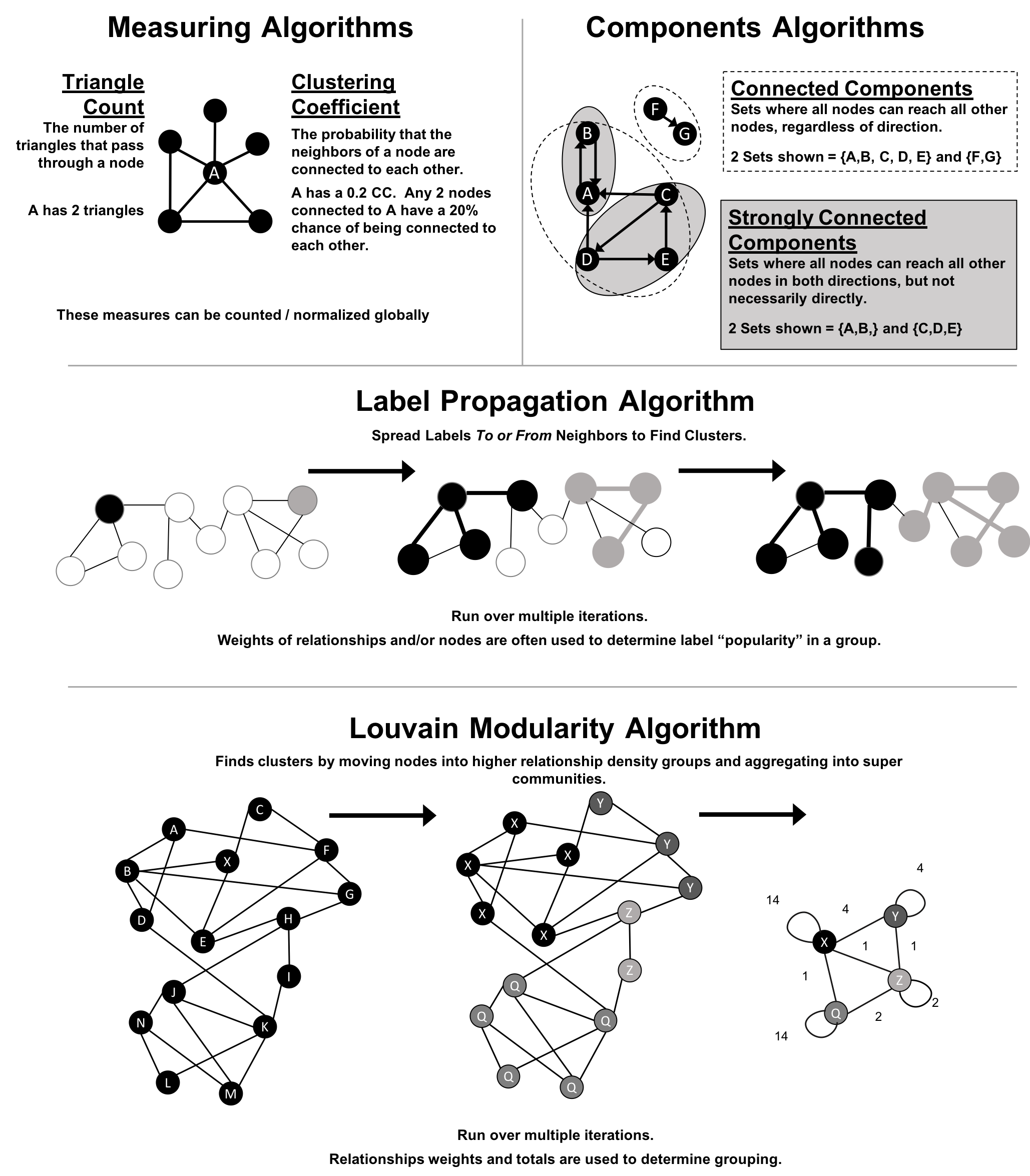

Let’s look into the three areas of analysis that are at the heart of graph algorithms. These categories correspond to the chapters on algorithms for pathfinding and search, centrality computation and community detection.

Paths are fundamental to graph analytics and algorithms. Finding shortest paths is probably the most frequent task performed with graph algorithms and is a precursor for several different types of analysis. The shortest path is the traversal route with the fewest hops or lowest weight. If the graph is directed, then it’s the shortest path between two nodes as allowed by the relationship directions.

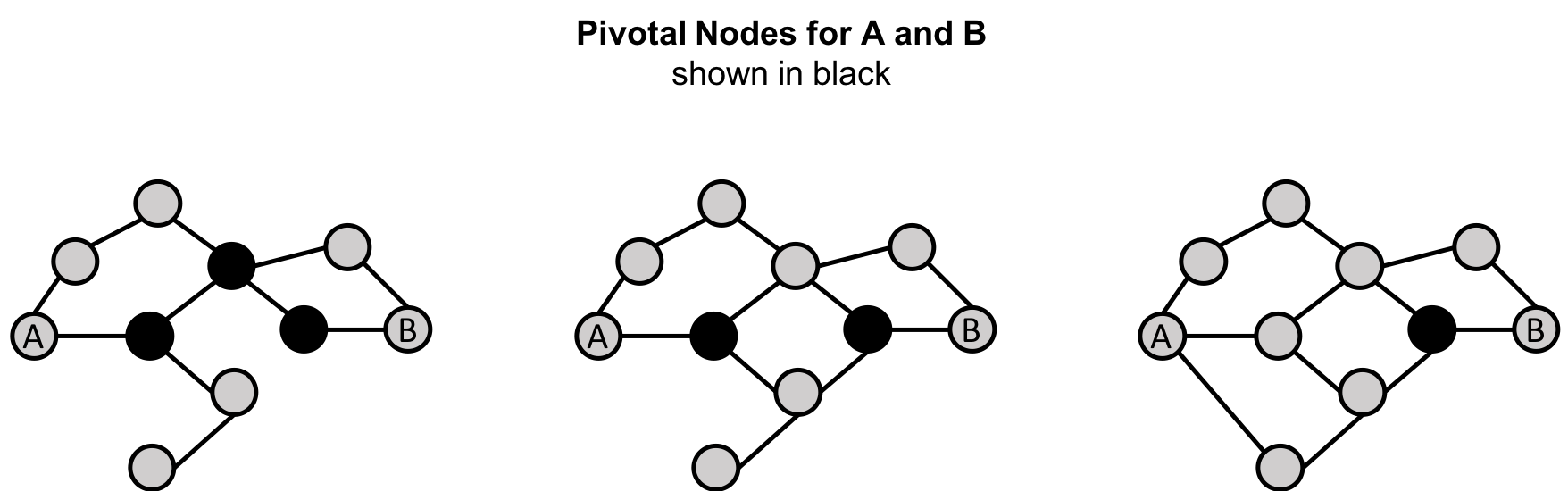

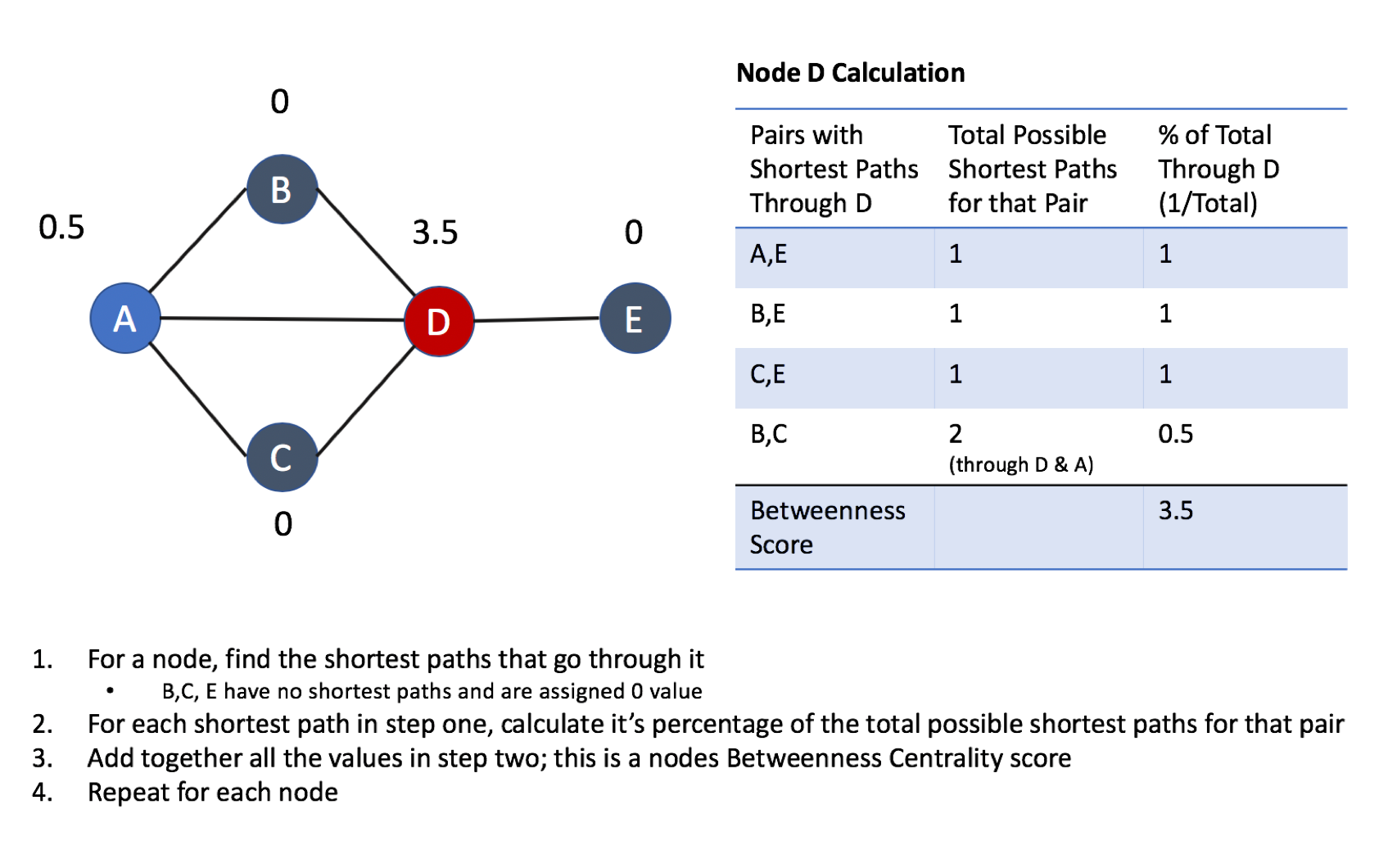

Centrality is all about understanding which nodes are more important in a network. But what do we mean by importance? There are different types of centrality algorithms created to measure different things such as the ability to quickly spread information versus bridge between distinct groups. In this book, we are mostly focused on topological analysis: looking at how nodes and relationships are structured.

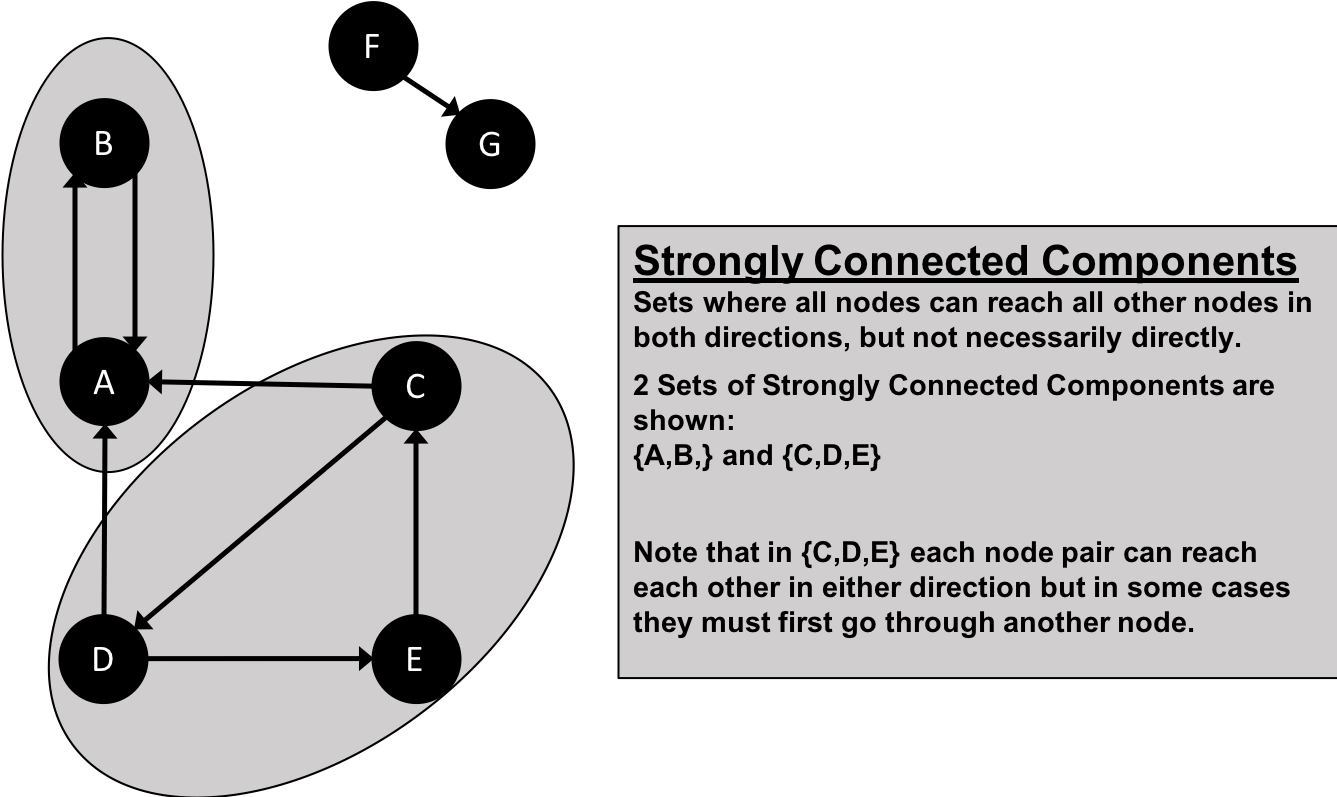

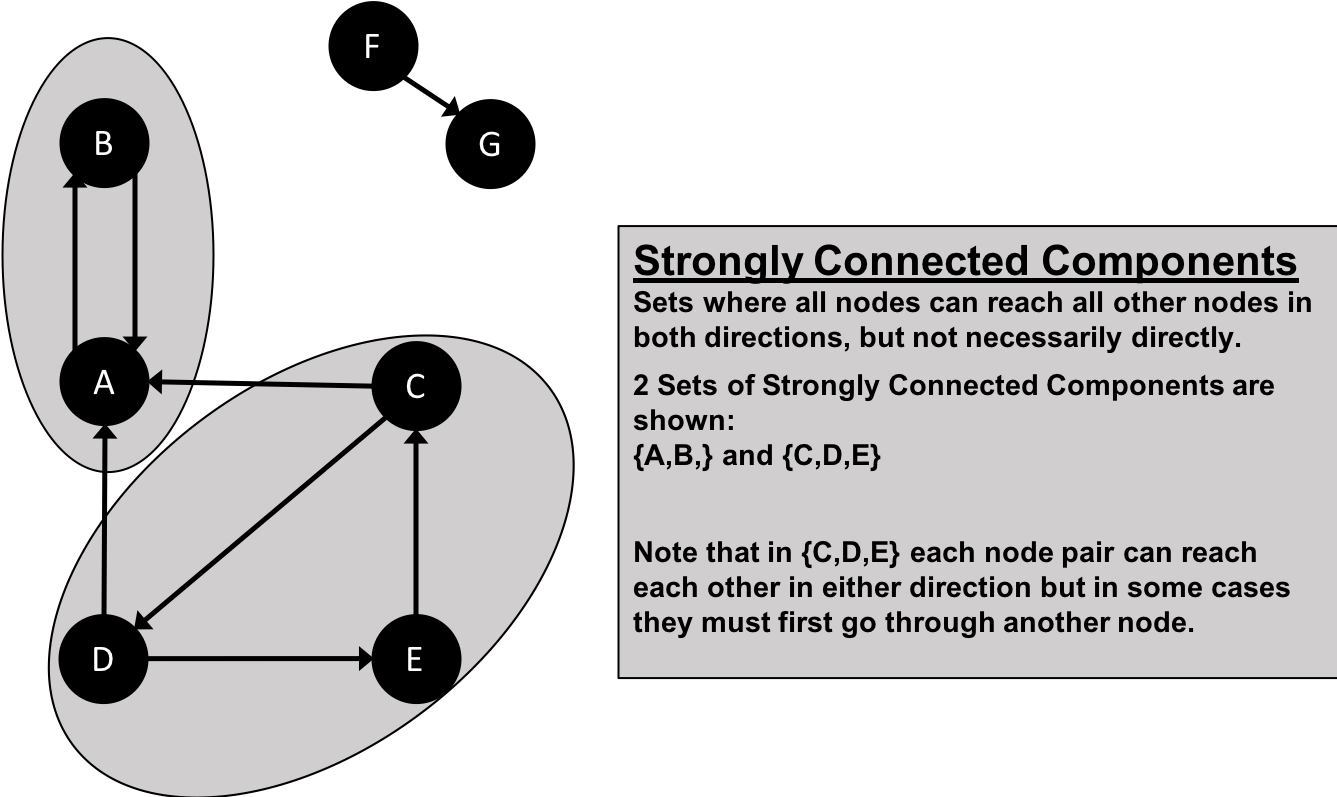

Connectedness is a core concept of graph theory that enables a sophisticated network analysis such as finding communities. Most real-world networks exhibit sub-structures (often quasi-fractal) of more or less independent subgraphs.

Connectivity is used to find communities and quantify the quality of groupings. Evaluating different types of communities within a graph can uncover structures, like hubs and hierarchies, and tendencies of groups to attract or repel others. These techniques are used to study the phenomenon in modern social networks that lead to echo chambers and filter-bubble effects, which are prevalent in modern political science.

Graphs are intuitive. They align with how we think about and draw systems. The primary tenets of working with graphs can be quickly assimilated once we’ve unraveled some of the terminology and layers. In this chapter we’ve explained the ideas and expressions used later in this book and described flavors of graphs you’ll come across.

Next, we’ll look at graph processing and types of analysis before diving into how to use graph algorithms in Apache Spark and Neo4j.

In this chapter, we’ll quickly cover different methods for graph processing and the most common platform approaches. We’ll look closer at the two platforms, Apache Spark and Neo4j, used in this book and when they may be appropriate for different requirements. Platform installation guidelines are included to prepare us for the next several chapters.

Graph analytical processing has unique qualities such as computation that is structure-driven, globally focused, and difficult to parse. In this section we’ll look at the general considerations for graph platforms and processing.

There’s a debate as to whether it’s better to scale up or scale out graph processing. Should you use powerful multicore, large-memory machines and focus on efficient data-structures and multithreaded algorithms? Or are investments in distributed processing frameworks and related algorithms worthwhile?

A useful approach is the Configuration that Outperforms a Single Thread (COST) as described in the research paper, “Scalability! But at what COST?”1. The concept is that a well configured system using an optimized algorithm and data-structure can outperform current general-purpose scale-out solutions. COST provides us with a way to compare a system’s scalability with the overhead the system introduces. It’s a method for measuring performance gains without rewarding systems that mask inefficiencies through parallelization. Separating the ideas of scalability and efficient use of resources will help build a platform configured explicitly for our needs.

Some approaches to graph platforms include highly integrated solutions that optimize algorithms, processing, and memory retrieval to work in tighter coordination.

There are different approaches for expressing data processing; for example, stream or batch processing or the map-reduce paradigm for records-based data. However, for graph data, there also exist approaches which incorporate the data-dependencies inherent in graph structures into their processing.

A node-centric approach uses nodes as processing units having them accumulate and compute state and communicate state changes via messages to their neighbors. This model uses the provided transformation functions for more straightforward implementations of each algorithm.

A relationship-centric approach has similiarities with the node-centric model but may perform better for subgraph and sequential analysis.

Graph-centric models process nodes within a subgraph independently of other subgraphs while (mimimal) communication to other subgraphs happens via messaging.

Traversal-centric models use the accumulation of data by the traverser while navigating the graph as their means of computation.

Algorithm-centric approaches use various methods to optimize implementations per algorithm. This is a hybrid of previous models.

Most of these graph specific approaches require the presence of the entire graph for efficient cross-topological operations. This is because separating and distributing the graph data leads to extensive data transfers and reshuffling between worker instances. This can be difficult for the many algorithms that need to iteratively process the global graph structure.

To address the requirements of graph processing several platforms have emerged. Traditionally there was a separation between graph compute engines and graph databases, that required users to move their data depending on their process needs.

Graph compute engines are read-only, non-transactional engines that focus on efficient execution of iterative graph analytics and queries of the whole graph. Graph compute engines support different definition and processing paradigms for graph algorithms, like vertex-centric (Pregel, Gather-Apply-Scatter) or map-reduce based approaches (PACT). Examples of such engines are Giraph, GraphLab, Graph-Engine, and Apache Spark.

Graph databases come from a transactional background focussing on fast writes and reads using smaller queries that generally touch only a small fraction of a graph. Their strengths are in operational robustness and high concurrent scalability for many users.

Choosing a production platform has many considersations such as the type of analysis to be run, performance needs, the existing environment, and team preferences. We use Apache Spark and Neo4j to showcase graph algorithms in this book because they both offer unique advantages.

Spark is an example of scale-out and node-centric graph compute engine. Its popular computing framework and libraries suppport a variety of data science workflows. Spark may be the right platform when our:

Algorithms are fundamentally parallelizable or partitionable.

Algorithm workflows needs “multi-lingual” operations in multiple tools and languages.

Analysis can be run off-line in batch mode.

Graph analysis is on data not transformed into a graph format.

Team has the expertise to code and implement new algorithms.

Team uses graph algorithms infrequently.

Team prefers to keep all data and analysis within the Hadoop ecosystem.

The Neo4j Graph Platform is an example of a tightly integrated graph database and algorithm-centric processing, optimized for graphs. Its popular for building graph-based applications and includes a graph algorithms library tuned for the native graph database. Neo4j may be the right platform when our:

Algorithms are more iterative and require good memory locality.

Algorithms and results are performance sensitive.

Graph analysis is on complex graph data and / or requires deep path traversal.

Analysis / Results are tightly integrated with transactional workloads.

Results are used to enrich an existing graph.

Team needs to integrate with graph-based visualization tools.

Team prefers prepackaged and supported algorithms.

Finally, some organizations select both Neo4j and Spark for graph processing. Using Spark for the high-level filtering and pre-processing of massive datasets and data integration and then the leveraging Neo4j for more specific processing and integration with graph-based applications.

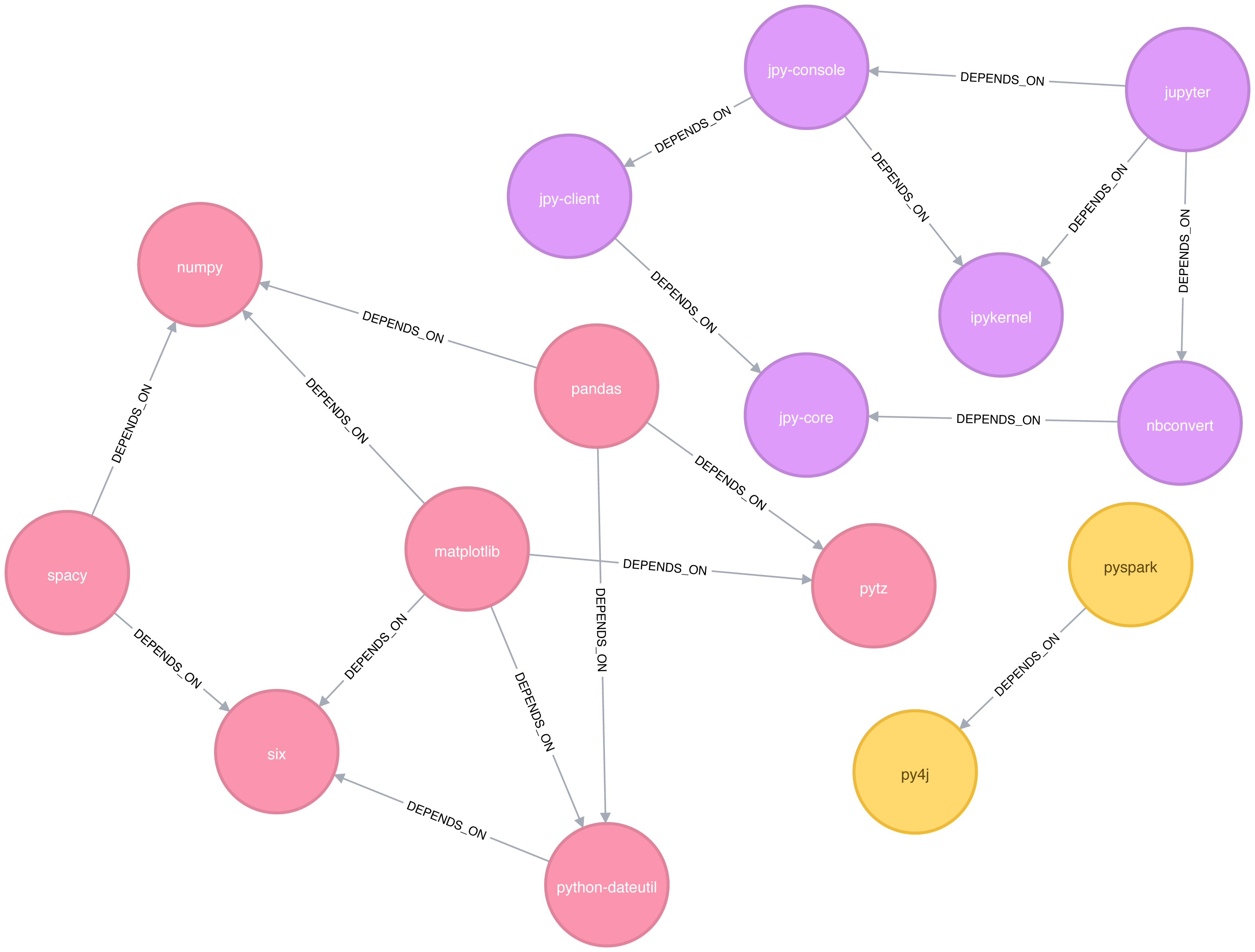

Apache Spark (henceforth just Spark) is a analytics engine for large-scale data processing. It uses a table abstraction called a DataFrame to represent and process data in rows of named and typed columns. The platform integrates diverse data sources and supports several languages such as Scala, Python, and R.

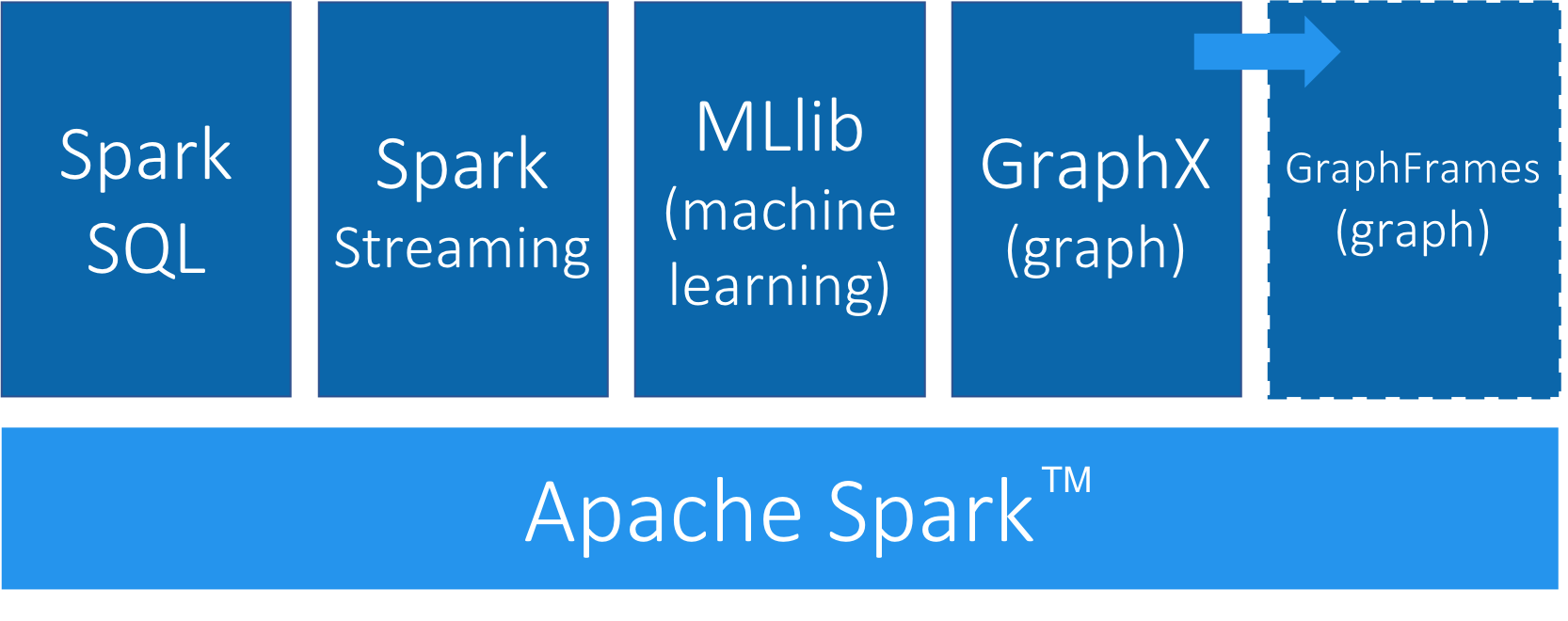

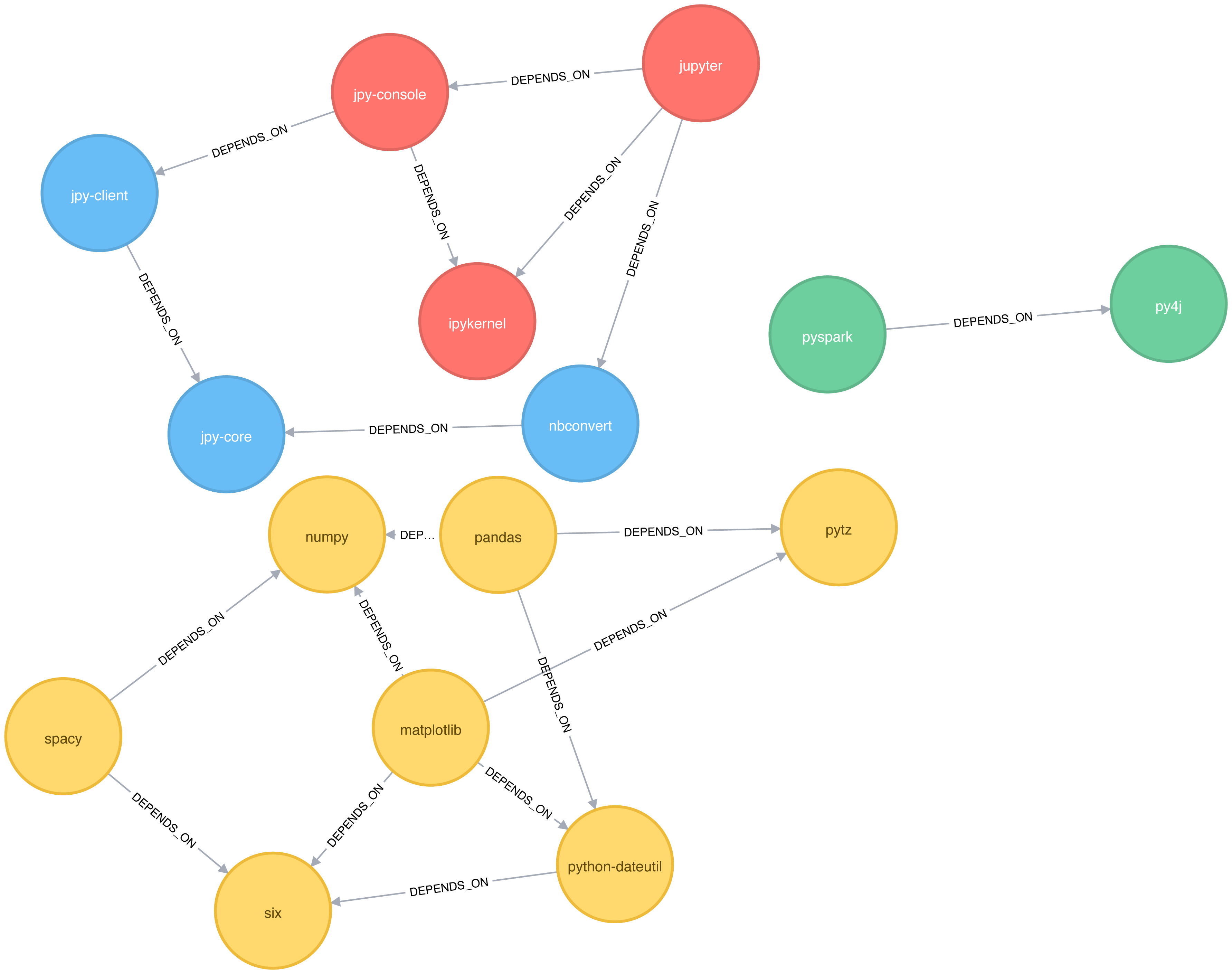

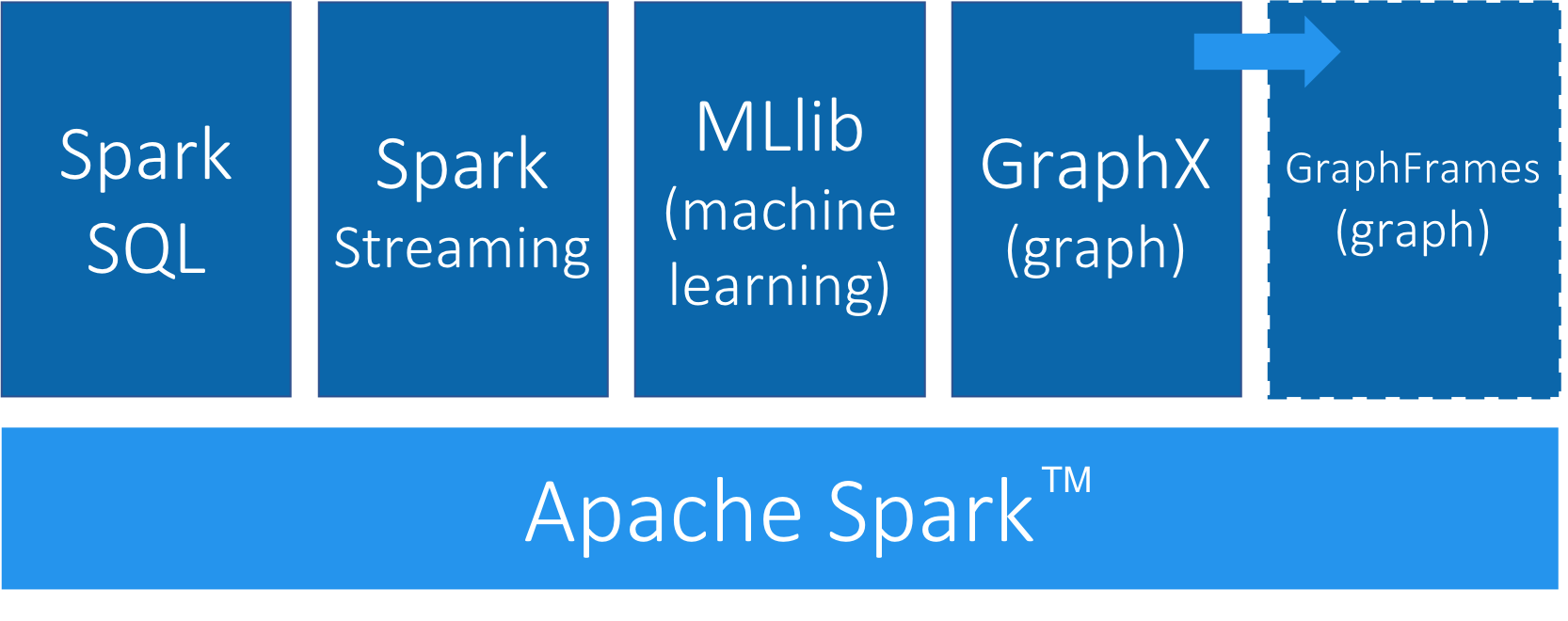

Spark supports a variety of analytics libraries as shown in Figure 3-1. It’s memory-based system uses efficiently distributed compute graphs for it’s operations.

GraphFrames is a graph processing library for Spark that succeeded GraphX in 2016, although it is still separate from the core Apache Spark. GraphFrames is based on GraphX, but uses DataFrames as its underlying data structure. GraphFrames has support for the Java, Scala, and Python programming languages. In this book our examples will be based on the Python API (PySpark).

Nodes and relationships are represented as DataFrames with a unique ID for each node and a source and destination node for each relationship.

We can see an example of a nodes DataFrame in Table 3-1 and a relationships DataFrame in Table 3-2.

A GraphFrame based on these DataFrames would have two nodes: JFK and SEA, and one relationship from JFK to SEA.

| id | city | state |

|---|---|---|

JFK |

New York |

NY |

SEA |

Seattle |

WA |

| src | dst | delay | tripId |

|---|---|---|---|

JFK |

SEA |

45 |

1058923 |

The nodes DataFrame must have an id column-the value in this column is used to uniquely identify that node.

The relationships DataFrame must have src and dst columns-the values in these columns describe which nodes are connected and should refer to entries that appear in the id column of the nodes DataFrame.

The nodes and relationships DataFrames can be loaded using any of the DataFrame data sources3, including Parquet, JSON, and CSV. Queries are described using a combination of the PySpark API and Spark SQL.

GraphFrames also provides users with an extension point4 to implement algorithms that aren’t available out of the box.

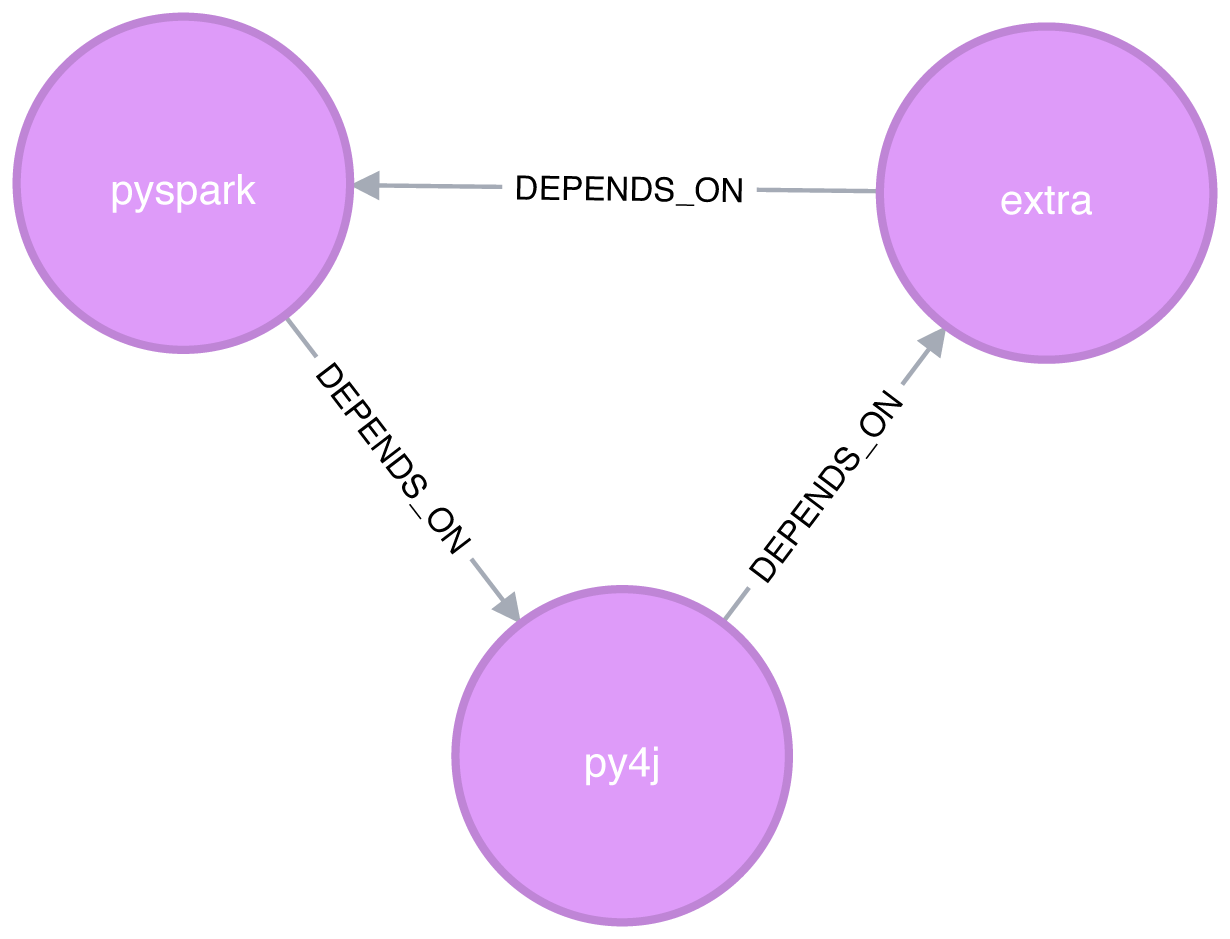

We can download Spark from the Apache Spark website5. Once we’ve downloaded Spark we need to install the following libraries to execute Spark jobs from Python:

pip install pyspark

pip install git+https://github.com/munro/graphframes.git@release-0.5.0#egg=graphframes

Once we’ve done that we can launch the pyspark REPL by executing the following command:

exportSPARK_VERSION="spark-2.4.0-bin-hadoop2.7"./${SPARK_VERSION}/bin/pyspark\--driver-memory 2g\--executor-memory 6g\--packages graphframes:graphframes:0.5.0-spark2.1-s_2.11

At the time of writing the latest released version of Spark is spark-2.4.0-bin-hadoop2.7 but that may have changed by the time you read this so be sure to change the SPARK_VERSION environment variable appropriately.

We’re now ready to learn how to run graph algorithms on Spark.

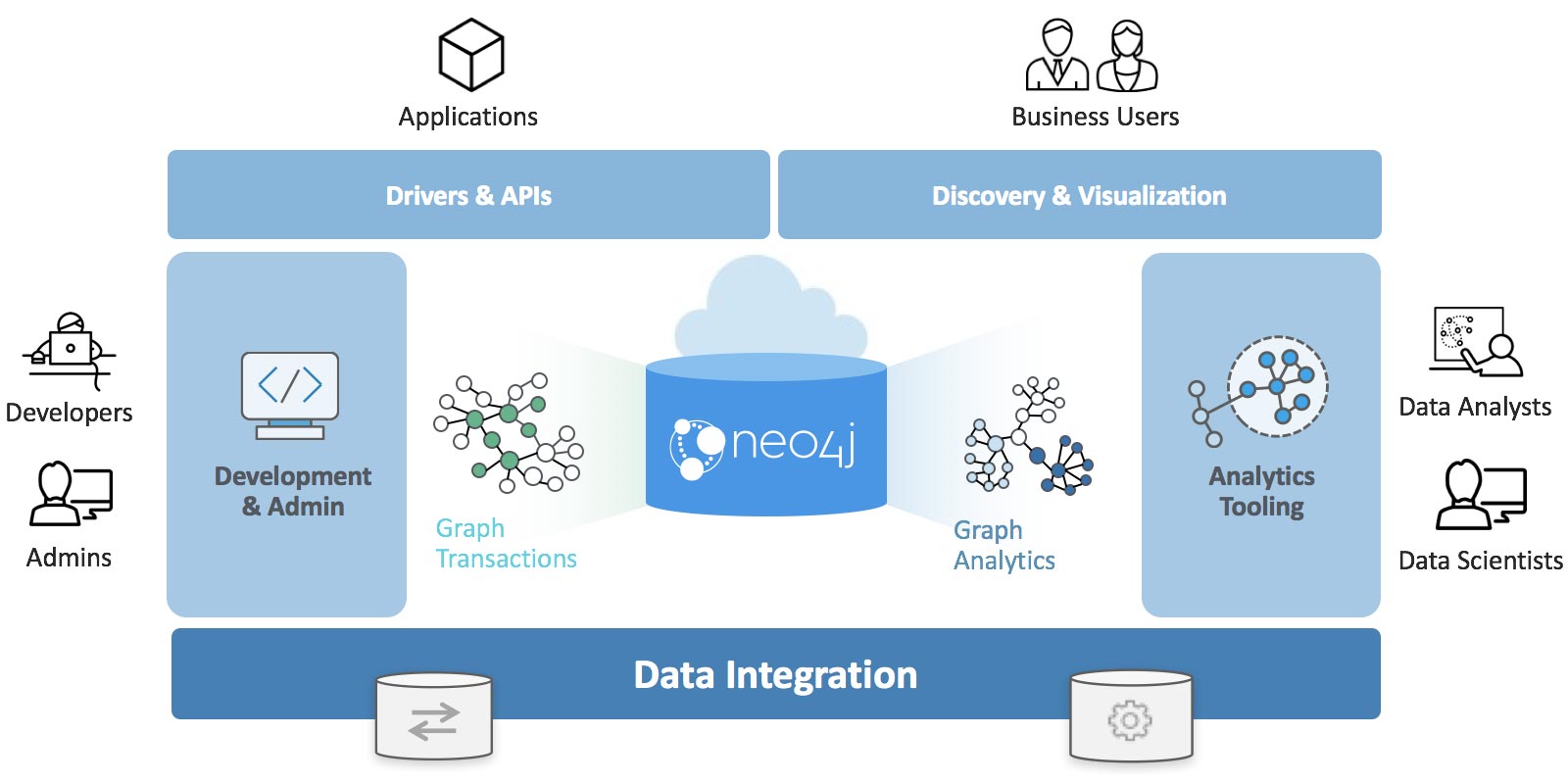

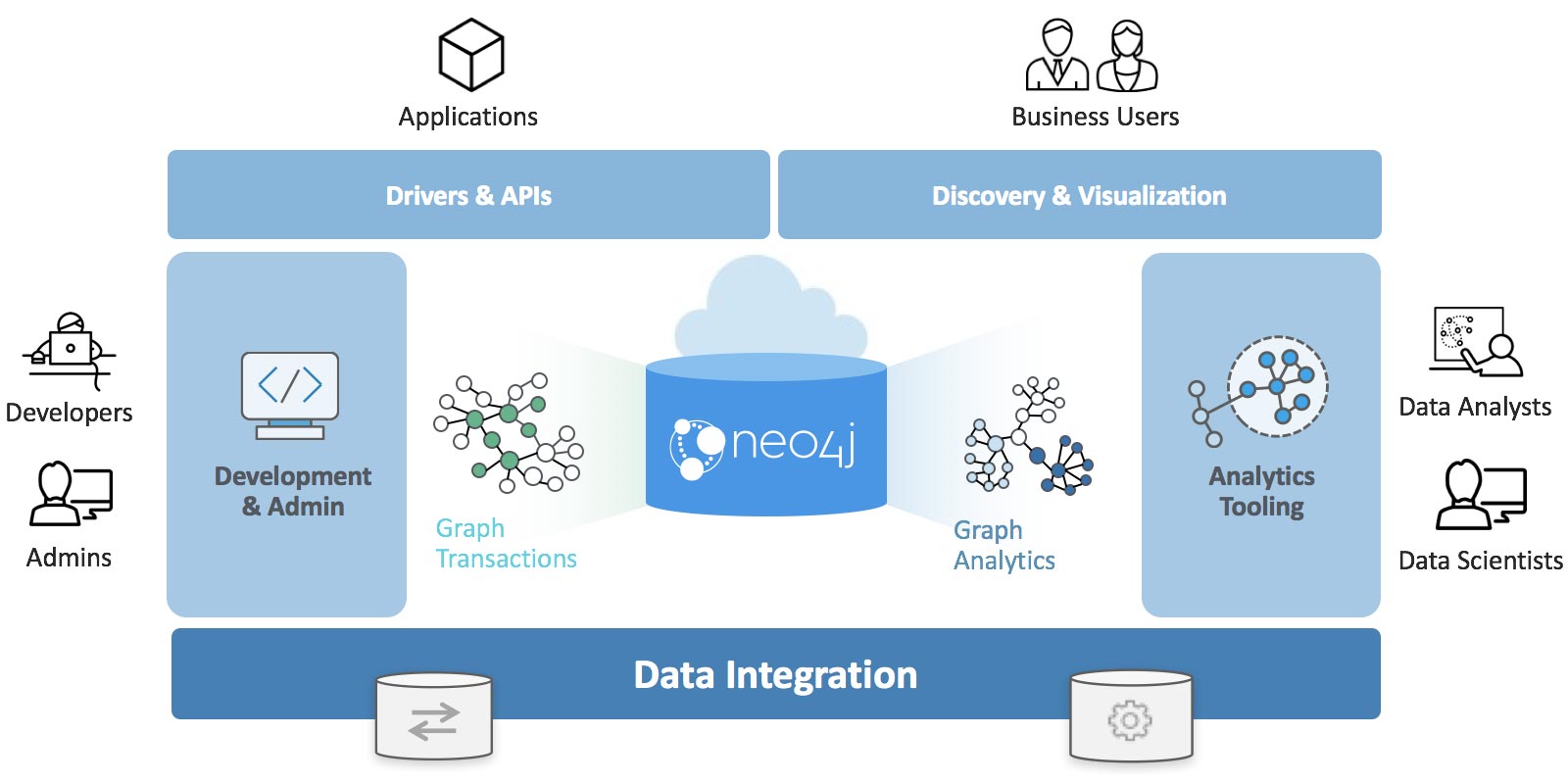

The Neo4j Graph Platform provides transactional processing and analytical processing of graph data. It includes graph storage and compute with data management and analytics tooling. The set of integrated tools sits on top of a common protocol, API, and query language (Cypher) to provide effective access for different uses as shown in Figure 3-2.

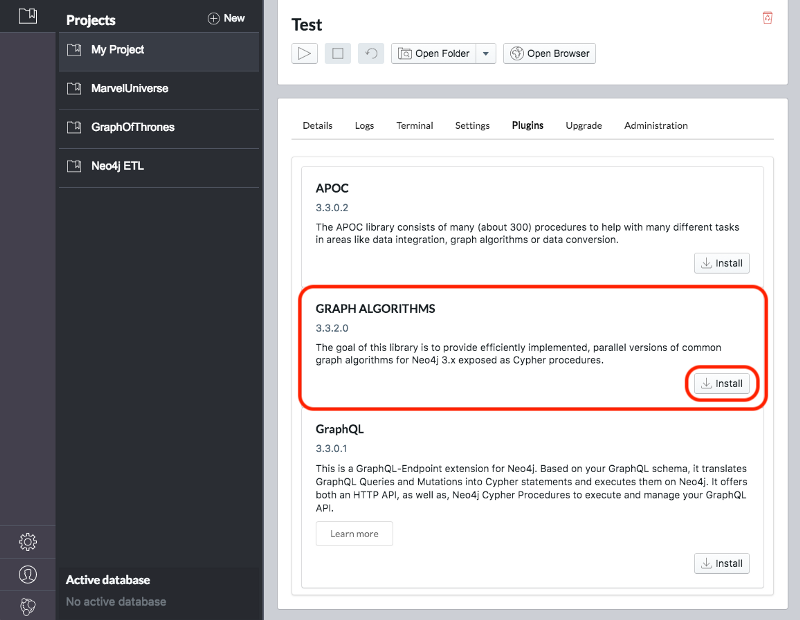

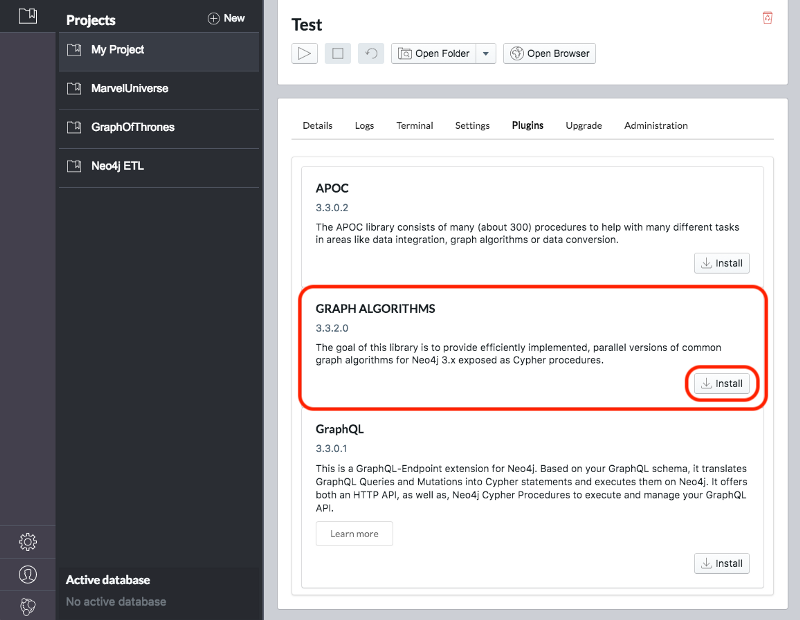

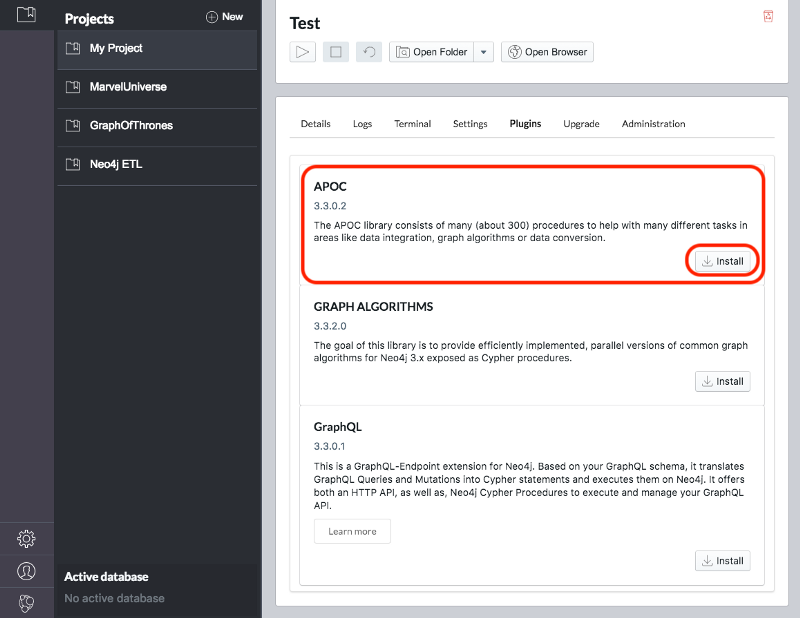

In this book we’ll be using the Neo4j Graph Algorithms library7, which was released in July 2017. The library can be installed as a plugin alongside the database, and provides a set of user defined procedures8 that can be executed via the Cypher query language.

The graph algorithm library includes parallel versions of algorithms supporting graph-analytics and machine-learning workflows. The algorithms are executed on top of a task based parallel computation framework and are optimized for the Neo4j platform. For different graph sizes there are internal implementations that scale up to tens of billions of nodes and relationships.

Results can be streamed to the client as a tuples stream and tabular results can be used as a driving table for further processing. Results can also be optionally written back to the database efficiently as node-properties or relationship types.

In this book, we’ll also be using the Neo4j APOC (Awesome Procedures On Cypher) library 9. APOC consists of more than 450 procedures and functions to help with common tasks such as data integration, data conversion, and model refactoring.

We can download the Neo4j desktop from the Neo4j website10. The Graph Algorithms and APOC libraries can be installed as plugins once we’ve installed and launched the Neo4j desktop.

Once we’ve created a project we need to select it on the left menu and click Manage on the database where we want to install the plugins.

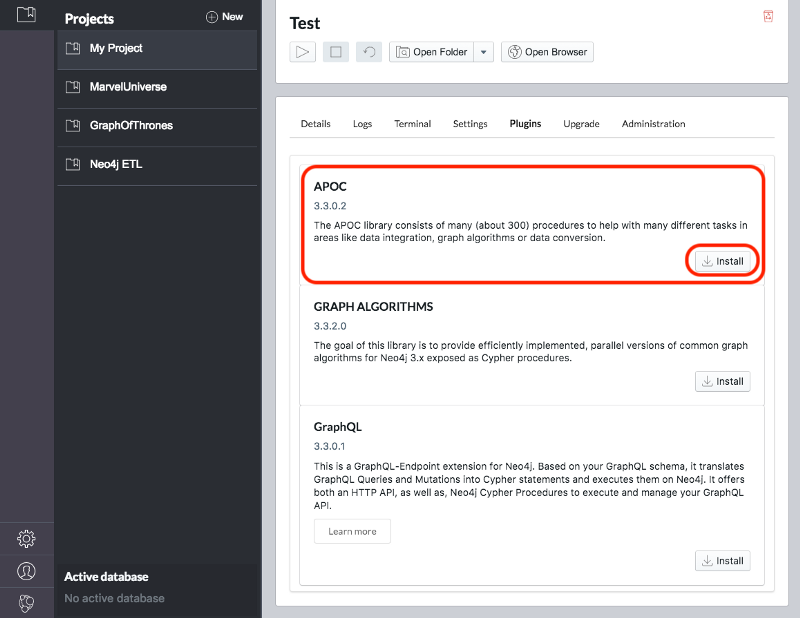

Under the Plugins tab we’ll see options for several plugins and we need to click the Install button for Graph Algorithms and APOC.

See Figure 3-3 and Figure 3-4.

Jennifer Reif explains the installation process in more detail in her blog post “Explore New Worlds—Adding Plugins to Neo4j” 11. We’re now ready to learn how to run graph algorithms on Neo4j.

The last few chapters we’ve described why graph analytics is important to studying real-work networks and looked at fundamental graph concepts, processing, and analysis. This puts us on solid footing for understanding how to apply graph algorithms. In the next chapters we’ll discover how to run graph algorithms with examples in Apache Spark and Neo4j.

1 https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/hotos15/hotos15-paper-mcsherry.pdf

2 https://kowshik.github.io/JPregel/pregel_paper.pdf

3 http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/sql-programming-guide.html#data-sources

4 https://graphframes.github.io/user-guide.html#message-passing-via-aggregatemessages

5 http://spark.apache.org/downloads.html

6 http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920034957.do

7 https://neo4j.com/docs/graph-algorithms/current/

8 https://neo4j.com/docs/developer-manual/current/extending-neo4j/procedures/

9 https://github.com/neo4j-contrib/neo4j-apoc-procedures

10 https://neo4j.com/download/

11 https://medium.com/neo4j/explore-new-worlds-adding-plugins-to-neo4j-26e6a8e5d37e

Pathfinding and Graph Search algorithms are used to identify optimal routes through a graph, and are often a required first step for many other types of analysis. In this chapter we’ll explain how these algorithms work and show examples in Spark and Neo4j. In cases where an algorithm is only available in one platform, we’ll provide just that one example or illustrate how you can customize your implementation.

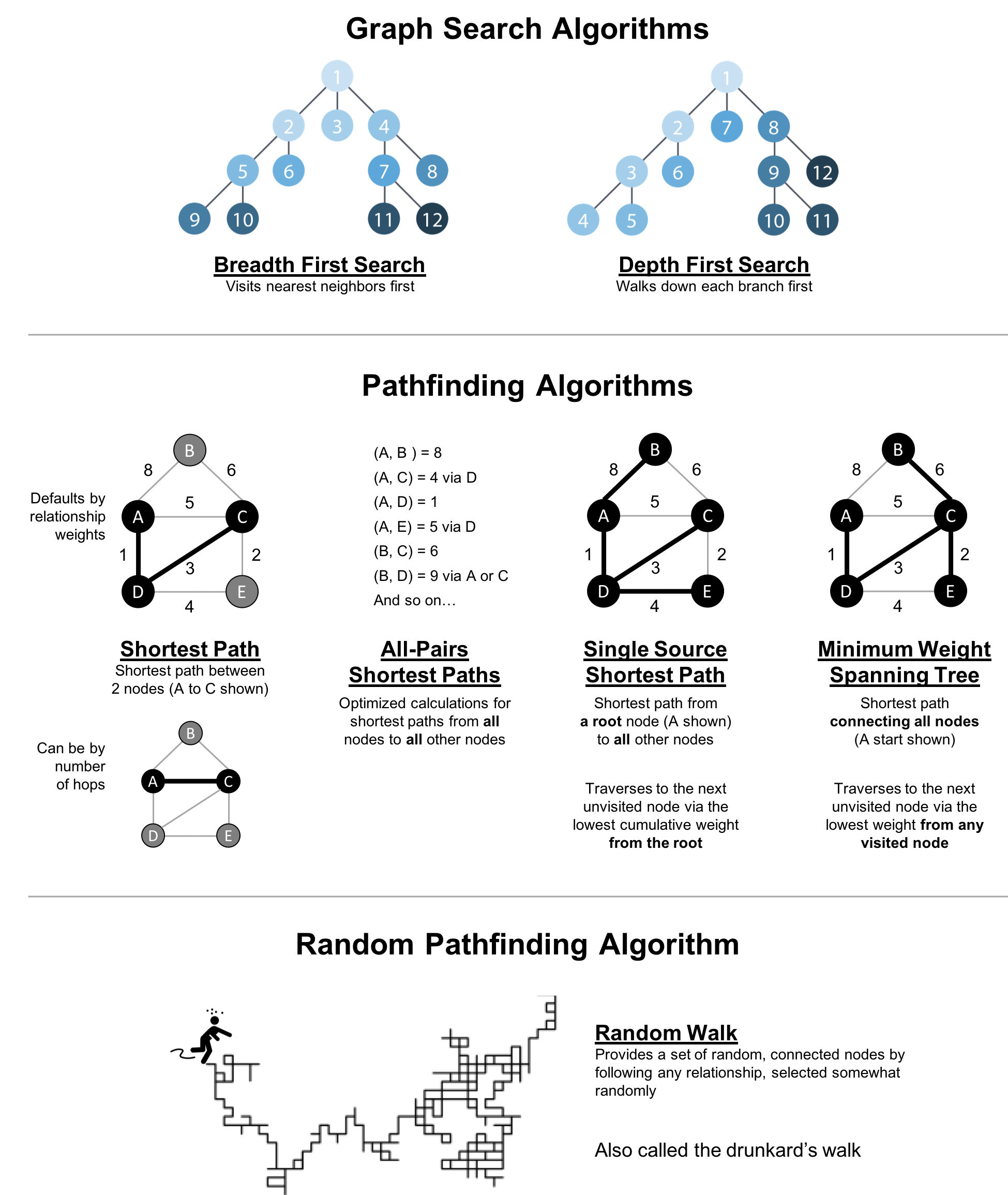

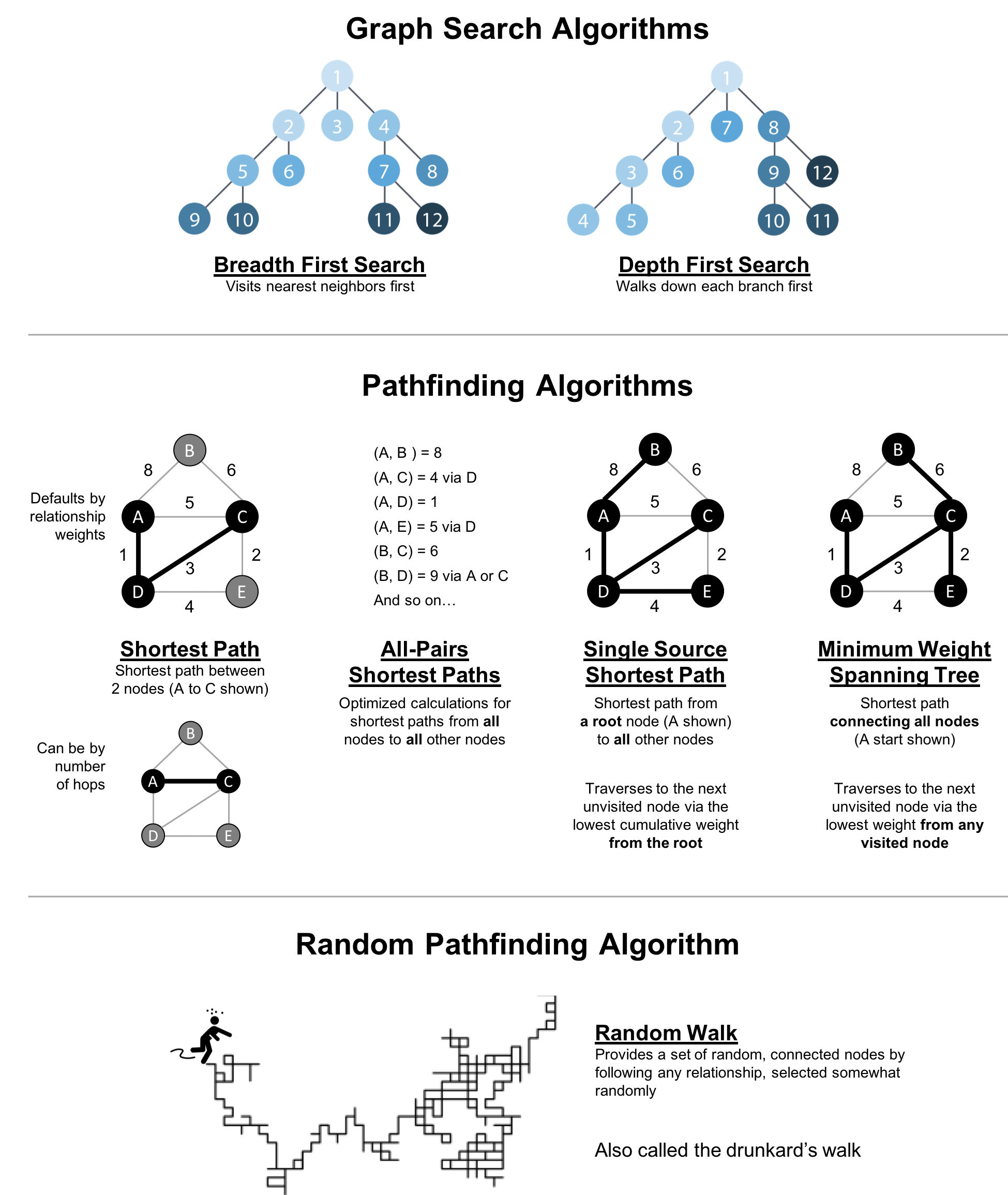

Graph search algorithms explore a graph either for general discovery or explicit search. These algorithms carve paths through the graph, but there is no expectation that those paths are computationally optimal. In this chapter we will go into detail on the two types of of graph search algorithms, Breadth First Search and Depth First Search because they are so fundamental for traversing and searching a graph.

Pathfinding algorithms build on top of graph search algorithms and explore routes between nodes, starting at one node and traversing through relationships until the destination has been reached. These algorithms find the cheapest path in terms of the number of hops or weight. Weights can be anything measured, such as time, distance, capacity, or cost.

Specifically the algorithms we’ll cover are:

Shortest Path with 2 useful variations (A* and Yen’s) for finding the shortest path or paths between two chosen nodes

Single Source Shortest Path for finding the shortest path from a chosen node to all others

Minimum Spanning Tree for finding a connected tree structure with the smallest cost for visiting all nodes from a chosen node

Random Walk because it’s a useful pre-processing/sampling step for machine learning workflows and other graph algorithms

Figure 4-1 shows the key differences between these types of algorithms and Table 4-1 is a quick reference to what each algorithm computes with an example use.

| Algorithm Type | What It Does | Example Uses | Spark Example | Neo4j Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Traverses a tree structure by fanning out to explore the nearest neighbors and then their sub-level neighbors. |

Locate neighbor nodes in GPS systems to identify nearby places of interest. |

Yes |

No |

|

Traverses a tree structure by exploring as far as possible down each branch before backtracking. |

Discover an optimal solution path in gaming simulations with hierarchical choices. |

No |

No |

|

Calculates the shortest path between a pair of nodes. |

Find driving directions between two locations. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Calculates the shortest path between all pairs of nodes in the graph. |

Evaluate alternate routes around a traffic jam. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Calculates the shorest path between a single root node and all other nodes. |

Least cost routing of phone calls. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Calculates the path in a connected tree structure with the smallest cost for visiting all nodes. |

Optimize connected routing such as laying cable or garbage collection. |

No |

Yes |

|

Returns a list of nodes along a path of specified size by randomly choosing relationships to traverse. |

Augment training for machine learning or data for graph algorithms. |

No |

Yes |

First we’ll take a look at the dataset for our examples and walk through how to import the data into Apache Spark and Neo4j. For each algorithm, we’ll start with a short description of the algorithm and any pertinent information on how it operates. Most sections also include guidance on when to use any related algorithms. Finally we provide working sample code using a sample dataset at the end of each section.

Let’s get started!

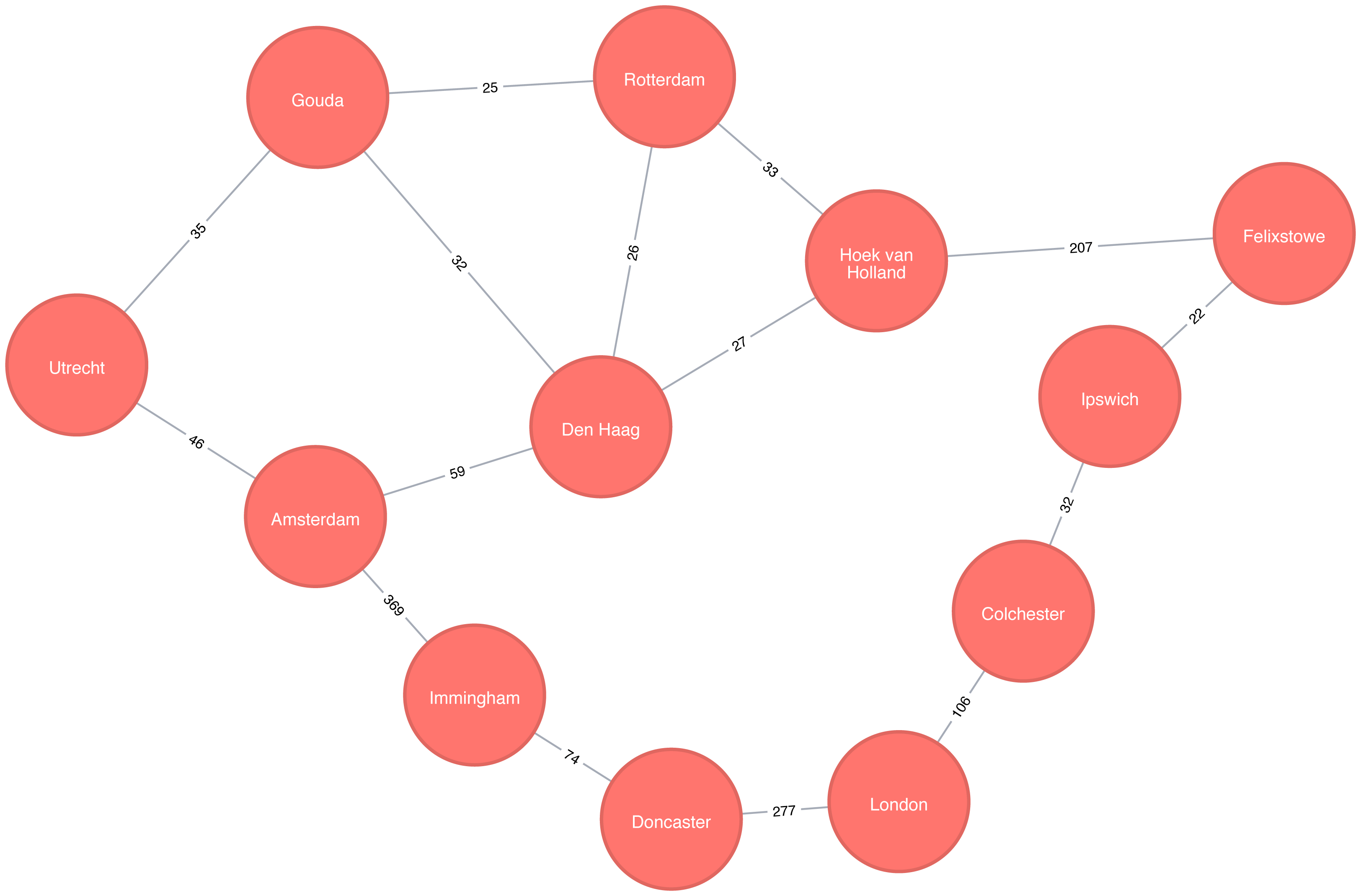

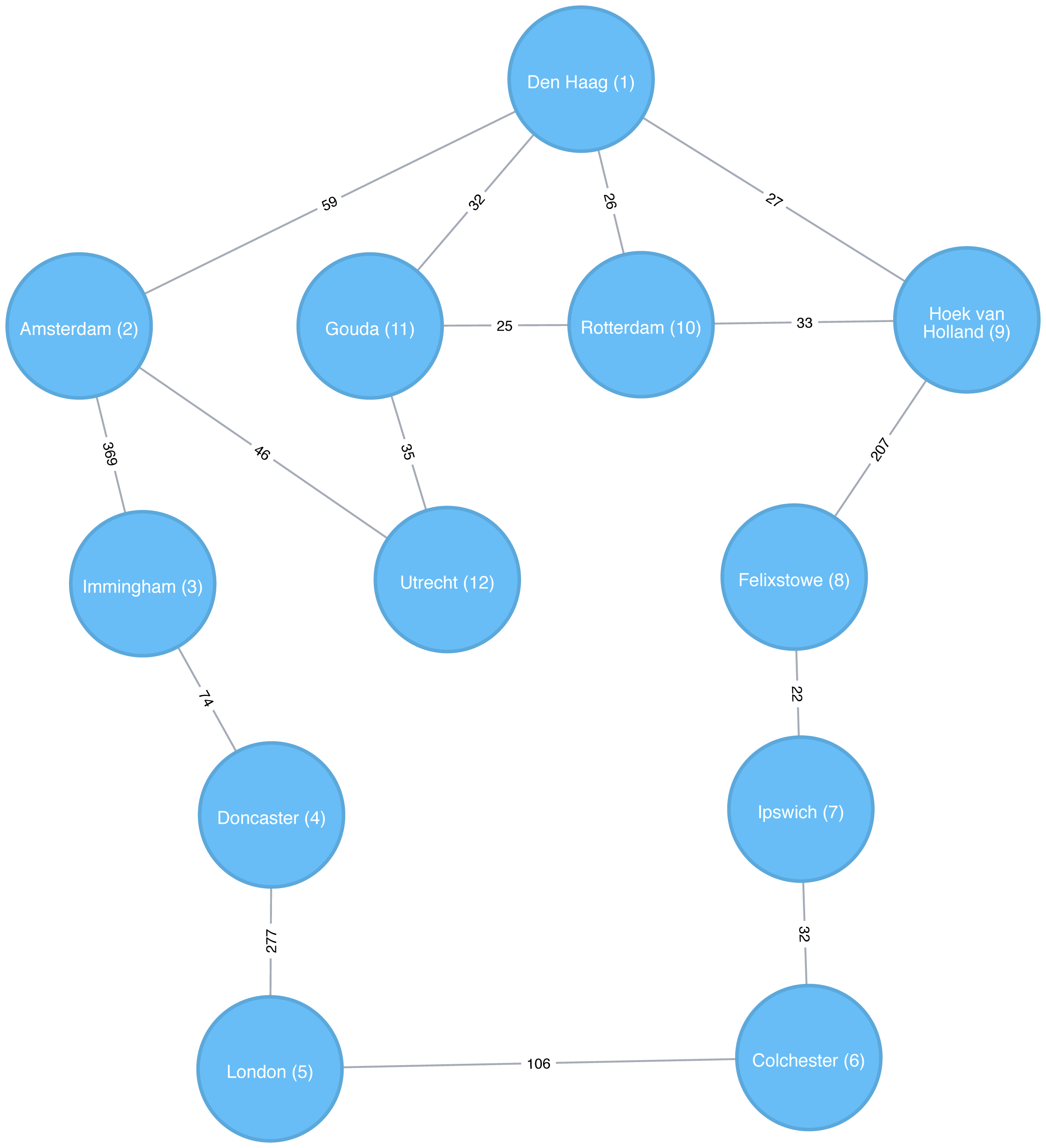

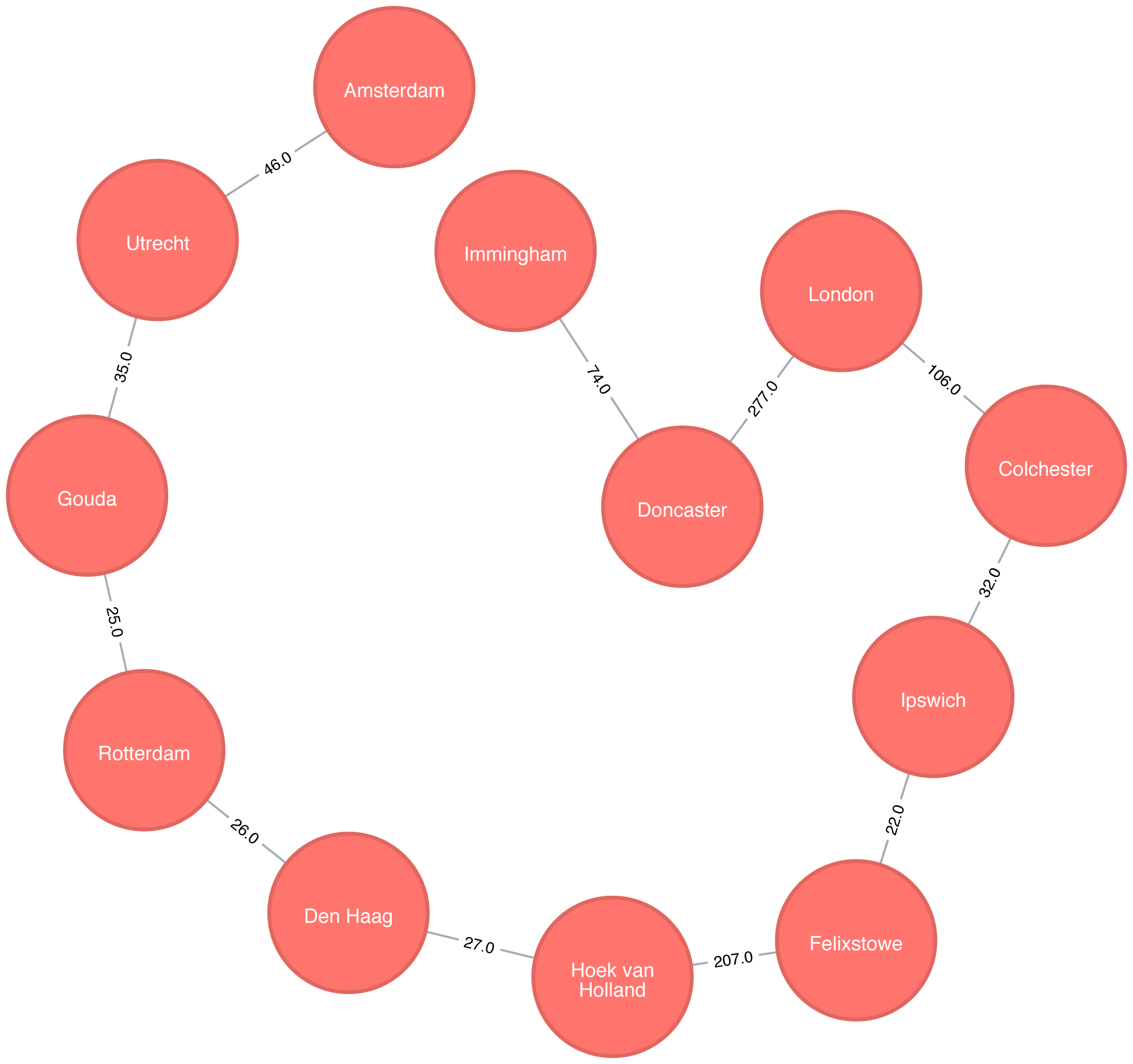

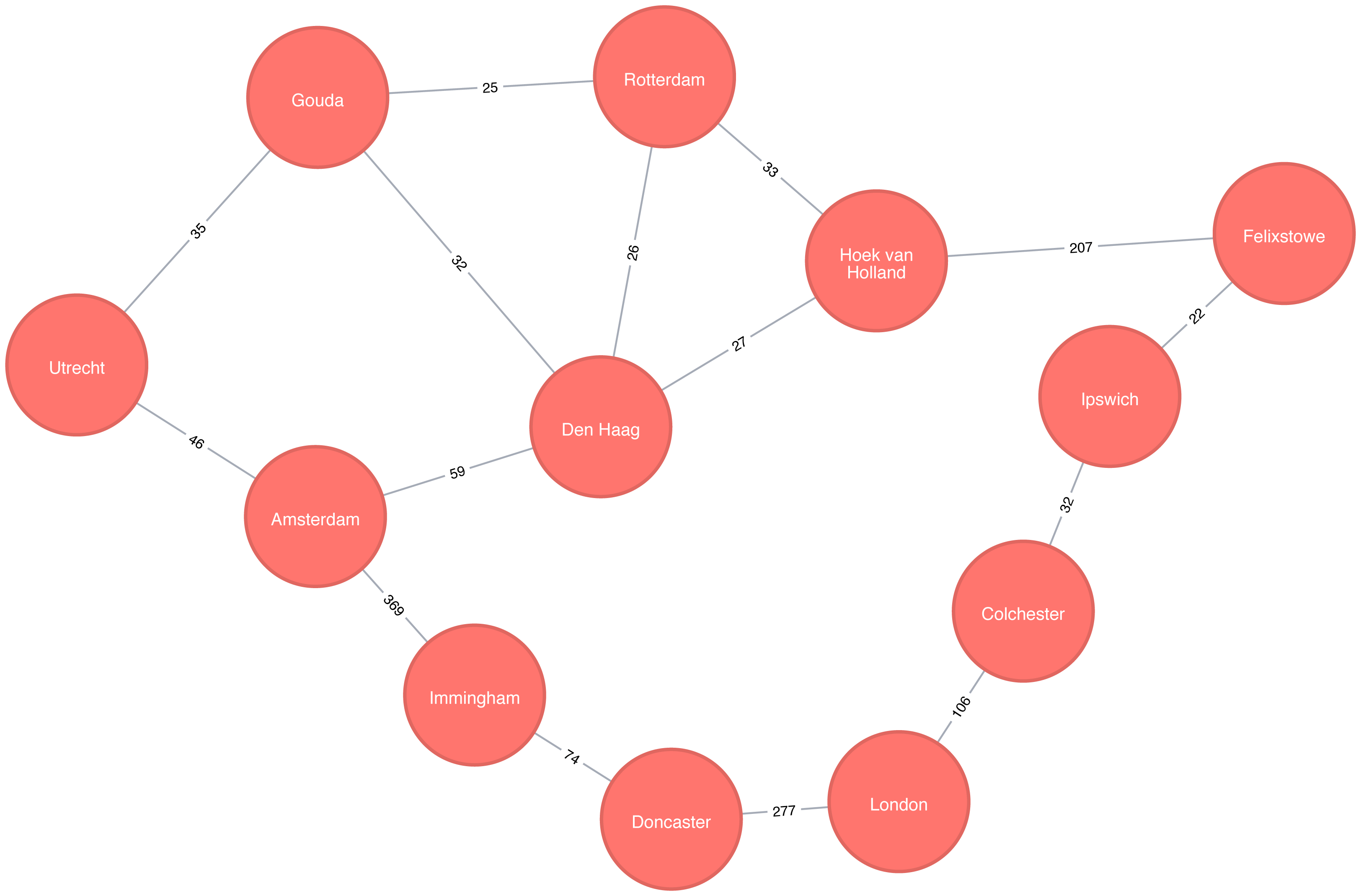

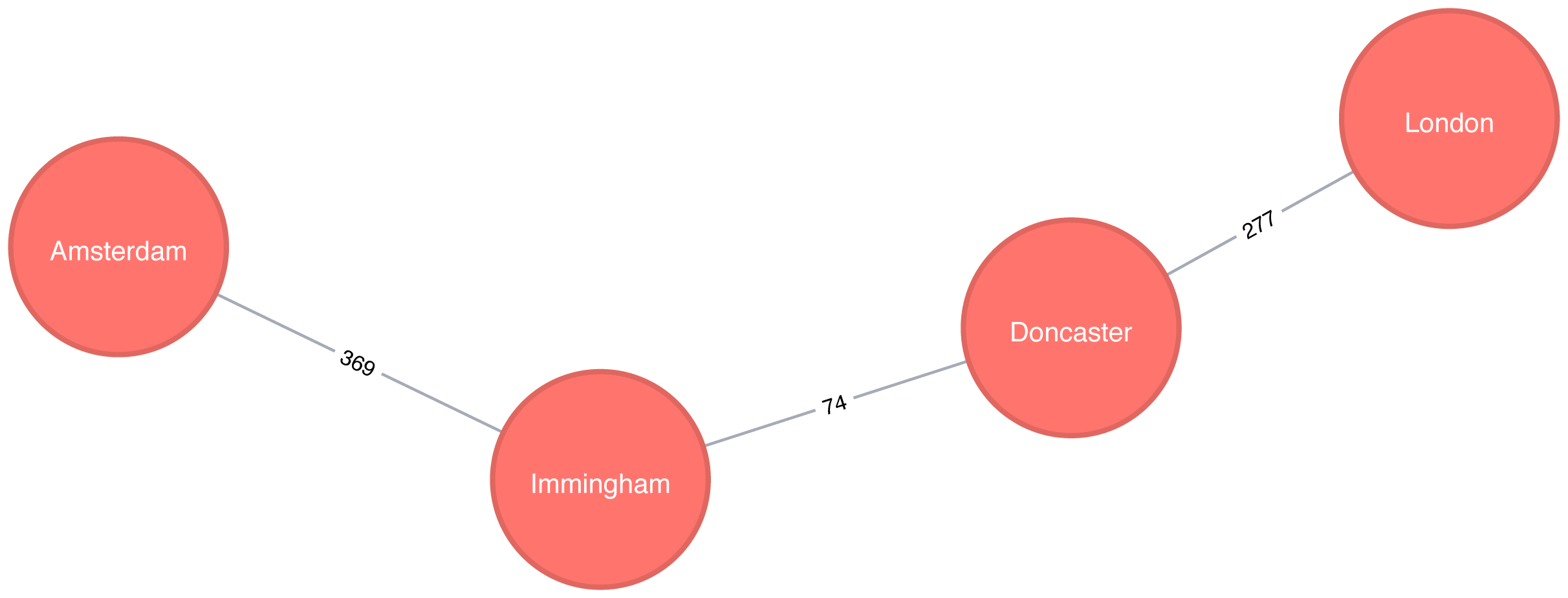

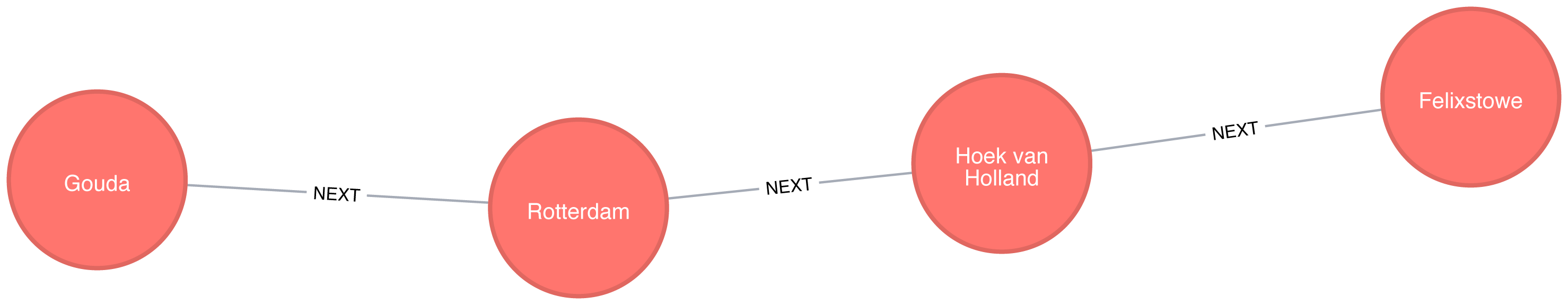

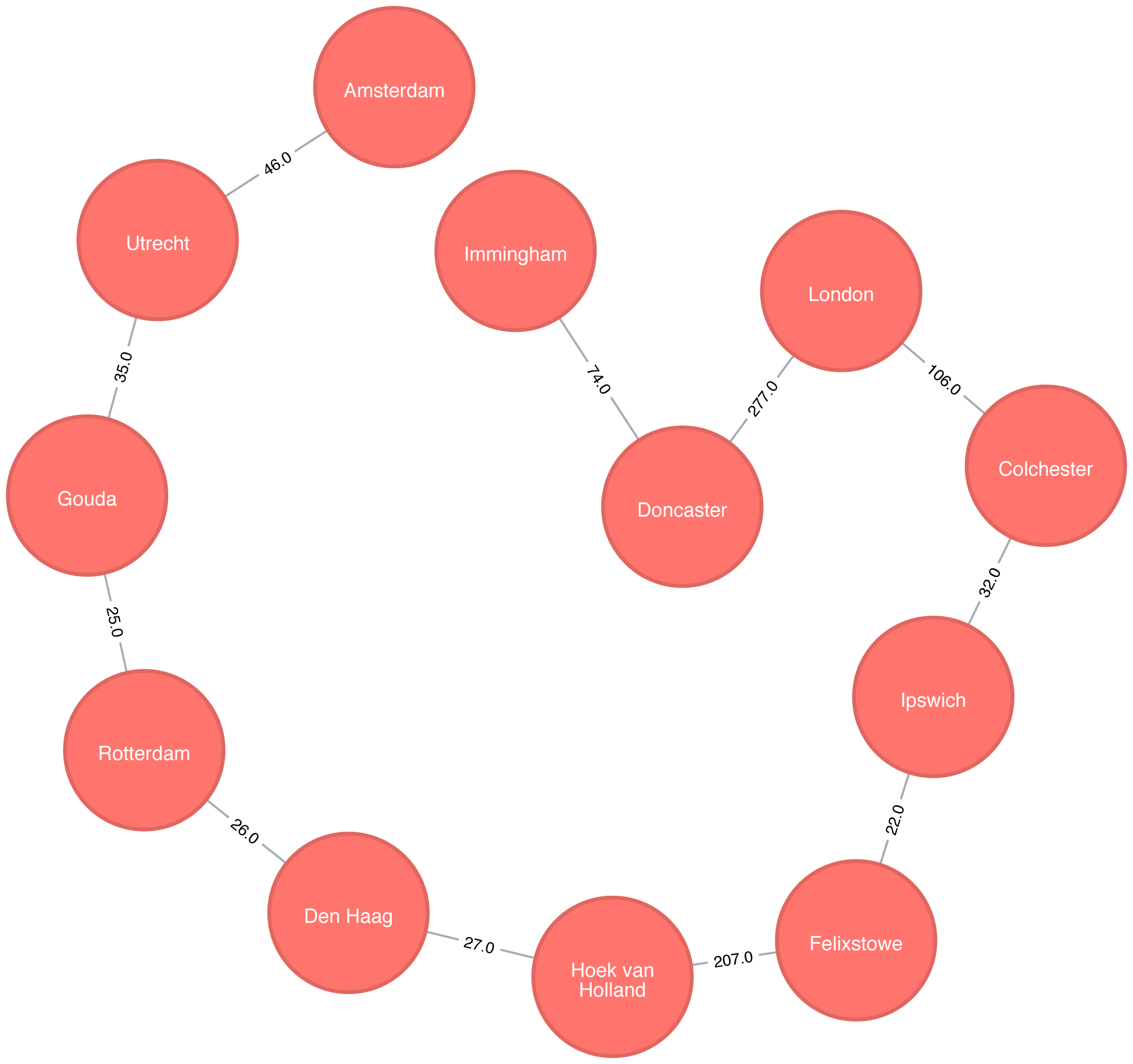

All connected data contains paths between nodes and transportation datasets show this in an intuitive and accessible way. The examples in this chapter run against a graph containing a subset of the European road network 1. You can download the nodes 2 and relationships 3 files from the book’s GitHub repository 4.

transport-nodes.csv

| id | latitude | longitude | population |

|---|---|---|---|

Amsterdam |

52.379189 |

4.899431 |

821752 |

Utrecht |

52.092876 |

5.104480 |

334176 |

Den Haag |

52.078663 |

4.288788 |

514861 |

Immingham |

53.61239 |

-0.22219 |

9642 |

Doncaster |

53.52285 |

-1.13116 |

302400 |

Hoek van Holland |

51.9775 |

4.13333 |

9382 |

Felixstowe |

51.96375 |

1.3511 |

23689 |

Ipswich |

52.05917 |

1.15545 |

133384 |

Colchester |

51.88921 |

0.90421 |

104390 |

London |

51.509865 |

-0.118092 |

8787892 |

Rotterdam |

51.9225 |

4.47917 |

623652 |

Gouda |

52.01667 |

4.70833 |

70939 |

transport-relationships.csv

| src | dst | relationship | cost |

|---|---|---|---|

Amsterdam |

Utrecht |

EROAD |

46 |

Amsterdam |

Den Haag |

EROAD |

59 |

Den Haag |

Rotterdam |

EROAD |

26 |

Amsterdam |

Immingham |

EROAD |

369 |

Immingham |

Doncaster |

EROAD |

74 |

Doncaster |

London |

EROAD |

277 |

Hoek van Holland |

Den Haag |

EROAD |

27 |

Felixstowe |

Hoek van Holland |

EROAD |

207 |

Ipswich |

Felixstowe |

EROAD |

22 |

Colchester |

Ipswich |

EROAD |

32 |

London |

Colchester |

EROAD |

106 |

Gouda |

Rotterdam |

EROAD |

25 |

Gouda |

Utrecht |

EROAD |

35 |

Den Haag |

Gouda |

EROAD |

32 |

Hoek van Holland |

Rotterdam |

EROAD |

33 |

Figure 4-2 shows the target graph that we want to construct:

For simplicity we consider the graph in Figure 4-2 to be undirected because most roads between cities are bidirectional. We’d get slightly different results if we evaluated the graph as directed because of the small number of one-way streets, but the overall approach remains similar. Conversely, both Apache Spark and Neo4j operate on directed graphs. In cases like this where we want to work with undirected graphs (bidirectional roads) there is an easy workaround:

For Apache Spark we’ll create two relationships for each row in transport-relationships.csv - one going from dst to src and one from src to dst.

For Neo4j we’ll create a single relationship and then ignore the relationship direction when we run the algorithms.

Having understood those little modeling workarounds, we can now get on with loading graphs into Apache Spark and Neo4j from the example CSV files.

Starting with Apache Spark, we’ll first import the packages we need from Spark and the GraphFrames package.

frompyspark.sql.typesimport*fromgraphframesimport*

The following function creates a GraphFrame from the example CSV files:

defcreate_transport_graph():node_fields=[StructField("id",StringType(),True),StructField("latitude",FloatType(),True),StructField("longitude",FloatType(),True),StructField("population",IntegerType(),True)]nodes=spark.read.csv("data/transport-nodes.csv",header=True,schema=StructType(node_fields))rels=spark.read.csv("data/transport-relationships.csv",header=True)reversed_rels=rels.withColumn("newSrc",rels.dst)\.withColumn("newDst",rels.src)\.drop("dst","src")\.withColumnRenamed("newSrc","src")\.withColumnRenamed("newDst","dst")\.select("src","dst","relationship","cost")relationships=rels.union(reversed_rels)returnGraphFrame(nodes,relationships)

Loading the nodes is easy, but for the relationships we need to do a little preprocessing so that we can create each relationship twice.

Now let’s call that function:

g=create_transport_graph()

Now for Neo4j. We’ll start by loading the nodes:

WITH"https://github.com/neo4j-graph-analytics/book/raw/master/data/transport-nodes.csv"ASuriLOAD CSVWITHHEADERS FROM uriASrowMERGE (place:Place {id:row.id})SETplace.latitude = toFloat(row.latitude),place.longitude = toFloat(row.latitude),place.population = toInteger(row.population)

And now the relationships:

WITH"https://github.com/neo4j-graph-analytics/book/raw/master/data/transport-relationships.csv"ASuriLOAD CSVWITHHEADERS FROM uriASrowMATCH(origin:Place {id: row.src})MATCH(destination:Place {id: row.dst})MERGE (origin)-[:EROAD {distance: toInteger(row.cost)}]->(destination)

Although we’re storing a directed relationship we’ll ignore the direction when we execute algorithms later in the chapter.

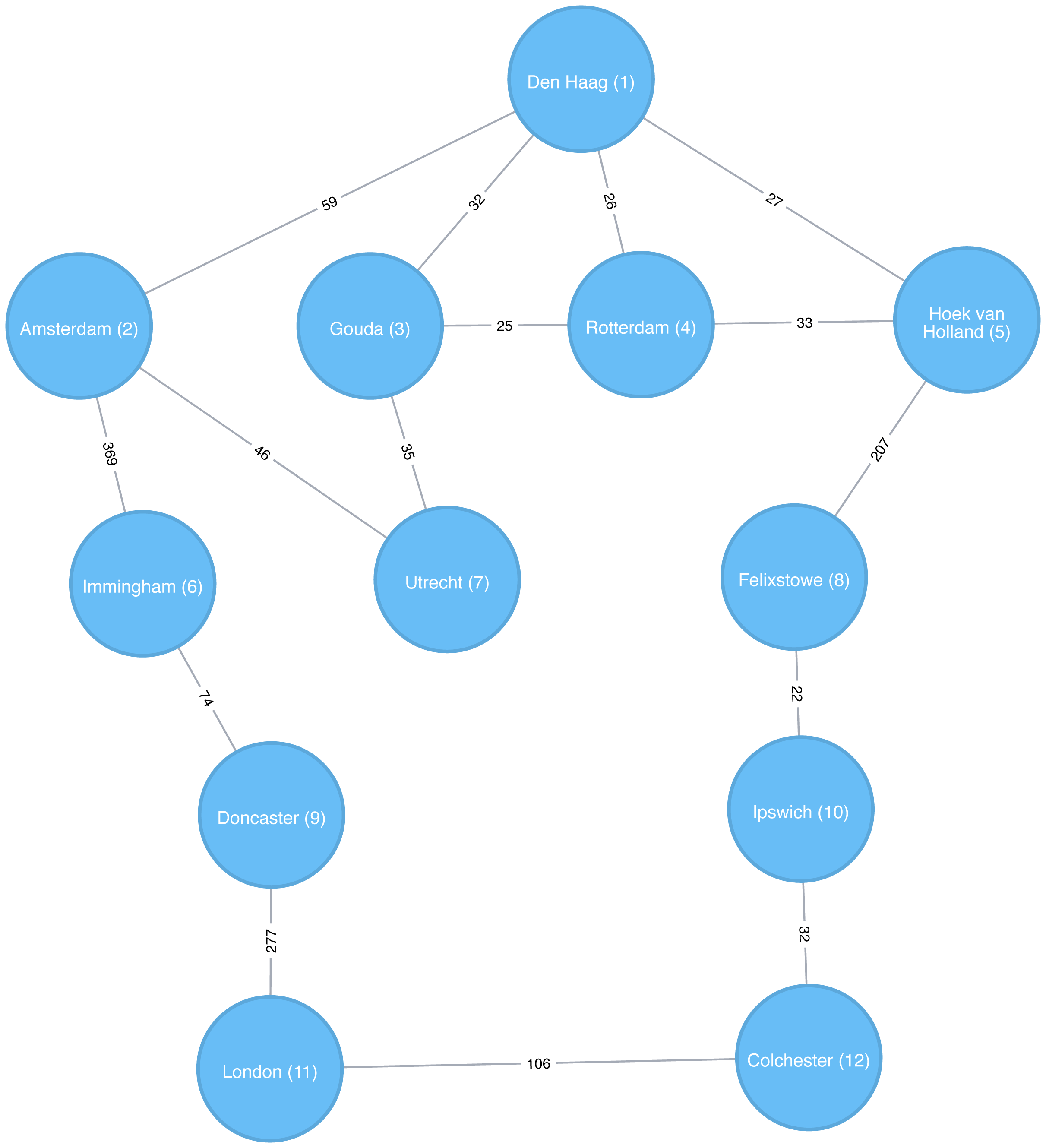

Breadth First Search (BFS) is one of the fundamental graph traversal algorithms. It starts from a chosen node and explores all of its neighbors at one hop away before visiting all neighbors at two hops away and so on.

The algorithm was first published in 1959 by Edward F. Moore who used it to find the shortest path out of a maze. It was later developed into a wire routing algorithm by C. Y. Lee in 1961 as described in “An Algorithm for Path Connections and Its Applications” 5

It is most commonly used as the basis for other more goal-oriented algorithms. For example Shortest Path, Connected Components, and Closeness Centrality all use the BFS algorithm. It can also be used to find the shortest path between nodes.

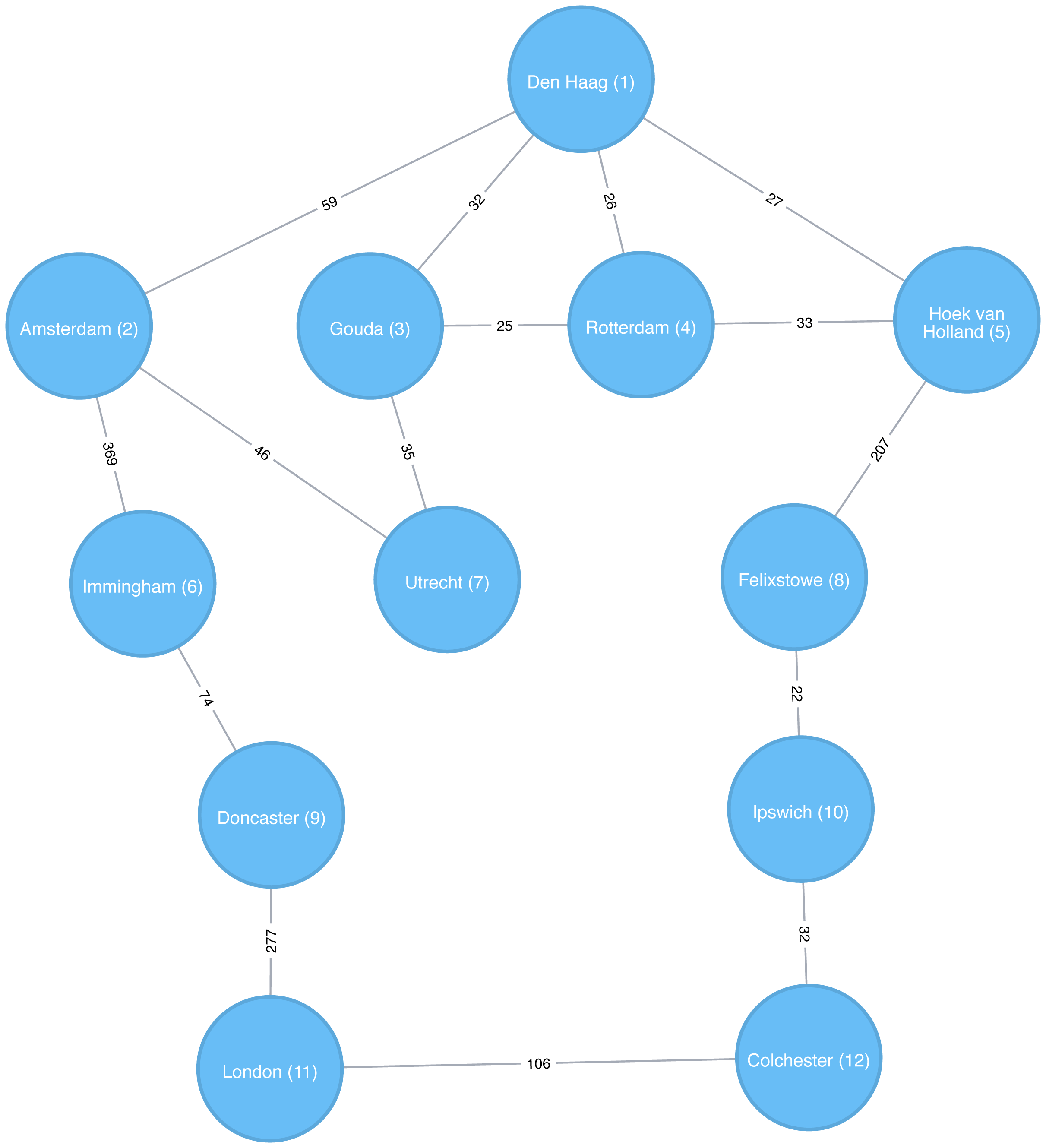

Figure 4-3 shows the order that we would visit the nodes of our transport graph if we were performing a breadth first search that started from Den Haag (in English, the Dutch city of The Hague). We first visit all of Den Haag’s direct neighbors, before visiting their neighbors, and their neighbors neighbors, until we’ve run out of relationships to traverse.

Apache Spark’s implementation of the Breadth First Search algorithm finds the shortest path between two nodes by the number of relationships (i.e. hops) between them. You can explicitly name your target node or add a criteria to be met.

For example, we can use the bfs function to find the first medium sized (by European standards) city that has a population of between 100,000 and 300,000 people.

Let’s first check which places have a population matching that criteria:

g.vertices\.filter("population > 100000 and population < 300000")\.sort("population")\.show()

This is the output we’ll see:

| id | latitude | longitude | population |

|---|---|---|---|

Colchester |

51.88921 |

0.90421 |

104390 |

Ipswich |

52.05917 |

1.15545 |

133384 |

There are only two places matching our criteria and we’d expect to reach Ipswich first based on a breadth first search.

The following code finds the shortest path from Den Haag to a medium-sized city:

from_expr="id='Den Haag'"to_expr="population > 100000 and population < 300000 and id <> 'Den Haag'"result=g.bfs(from_expr,to_expr)

result contains columns that describe the nodes and relationships between the two cities.

We can run the following code to see the list of columns returned:

(result.columns)

This is the output we’ll see:

['from', 'e0', 'v1', 'e1', 'v2', 'e2', 'to']

Columns beginning with e represent relationships (edges) and columns beginning with v represent nodes (vertices).

We’re only interested in the nodes so let’s filter out any columns that begin with e from the resulting DataFrame.

columns=[columnforcolumninresult.columnsifnotcolumn.startswith("e")]result.select(columns).show()

If we run the code in pyspark we’ll see this output:

| from | v1 | v2 | to |

|---|---|---|---|

[Den Haag, 52.078… |

[Hoek van Holland… |

[Felixstowe, 51.9… |

[Ipswich, 52.0591… |

As expected the bfs algorithm returns Ipswich!

Remember that this function is satisfied when it finds the first matching criteria and as you can see in Figure 4-3, Ipswich is evaluated before Colchester.

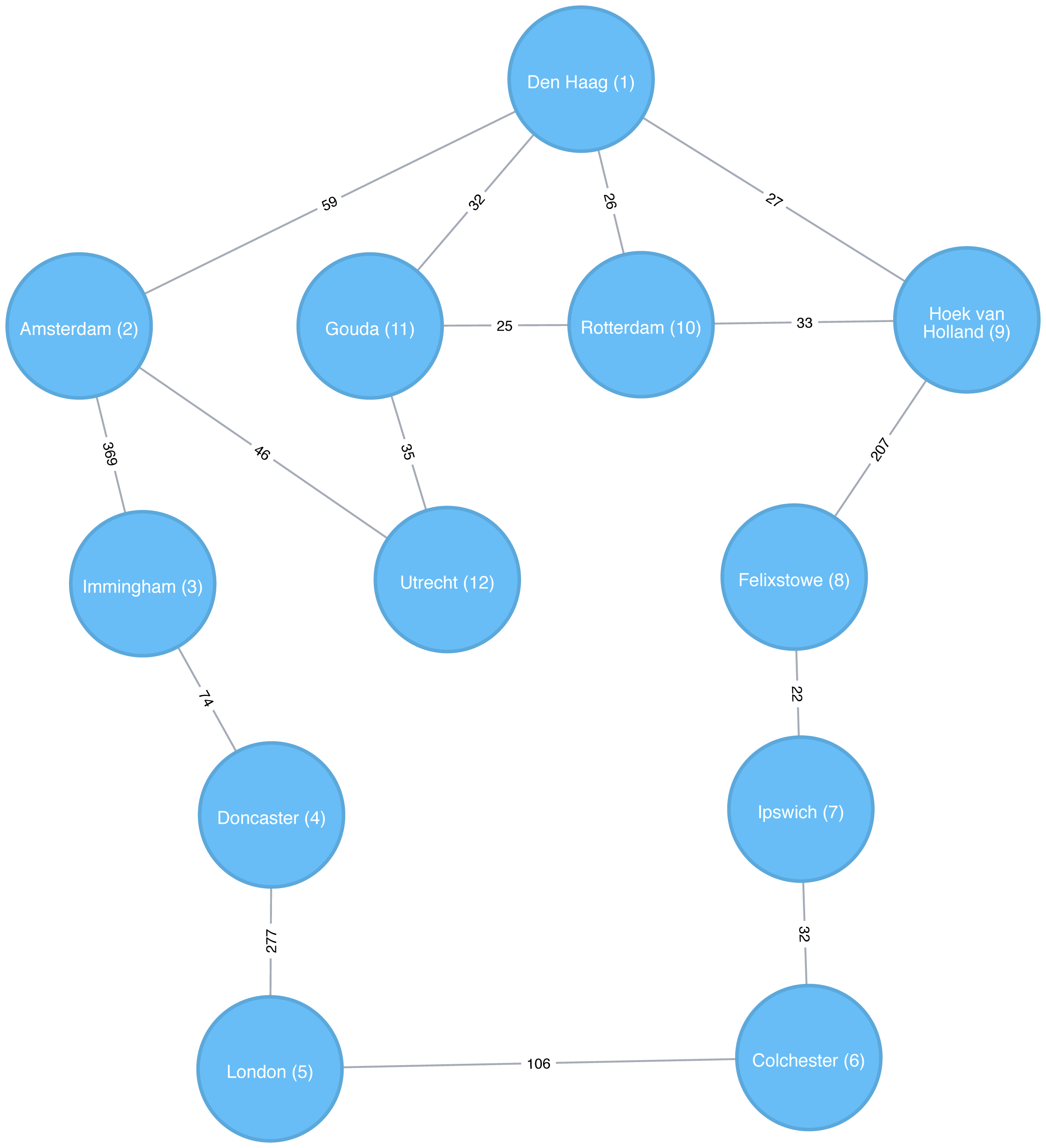

Depth First Search (DFS) is the other fundamental graph traversal algorithm. It was originally invented by French mathematician Charles Pierre Trémaux as a strategy for solving mazes. It starts from a chosen node, picks one of its neighbors and then traverses as far as it can along that path before backtracking.

Figure 4-4 shows the order that we would visit the nodes of our transport graph if we were performing a DFS that started from Den Haag. We start by traversing from Den Haag to Amsterdam, and are then able to get to every other node in the graph without needing to backtrack at all!

The Shortest Path algorithm calculates the shortest (weighted) path between a pair of nodes. It’s useful for user interactions and dynamic workflows because it works in real-time.

Pathfinding has a history dating back to the 19th century and is considered to be a classic graph problem. It gained prominence in the early 1950s in the context of alternate routing, that is, finding the second shortest route if the shortest route is blocked. In 1956, Edsger Dijkstra created the most well known of the shortest path algorithms.

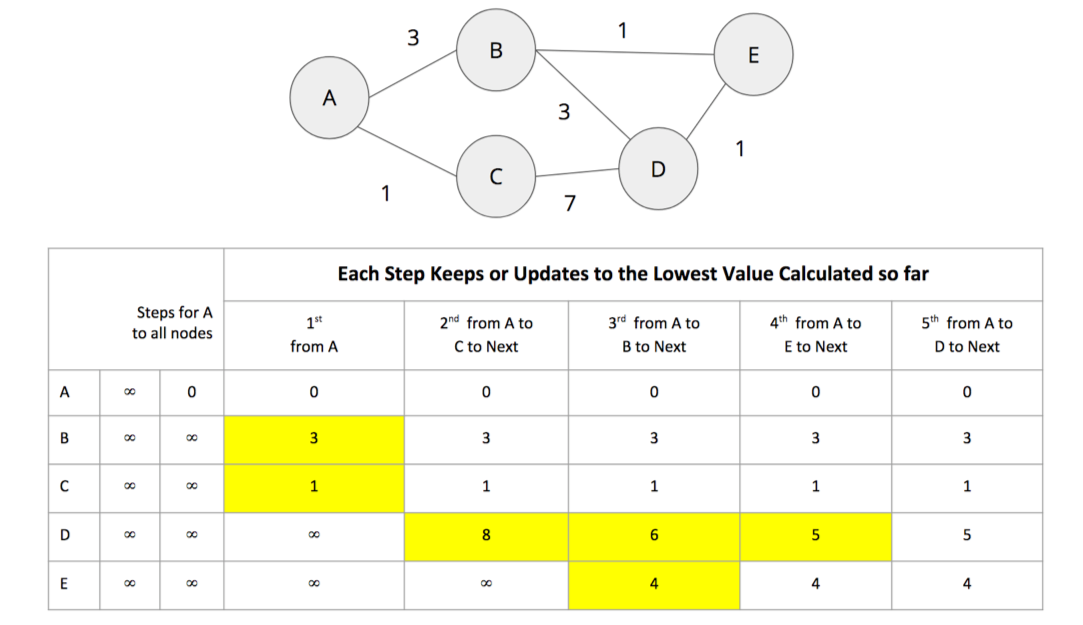

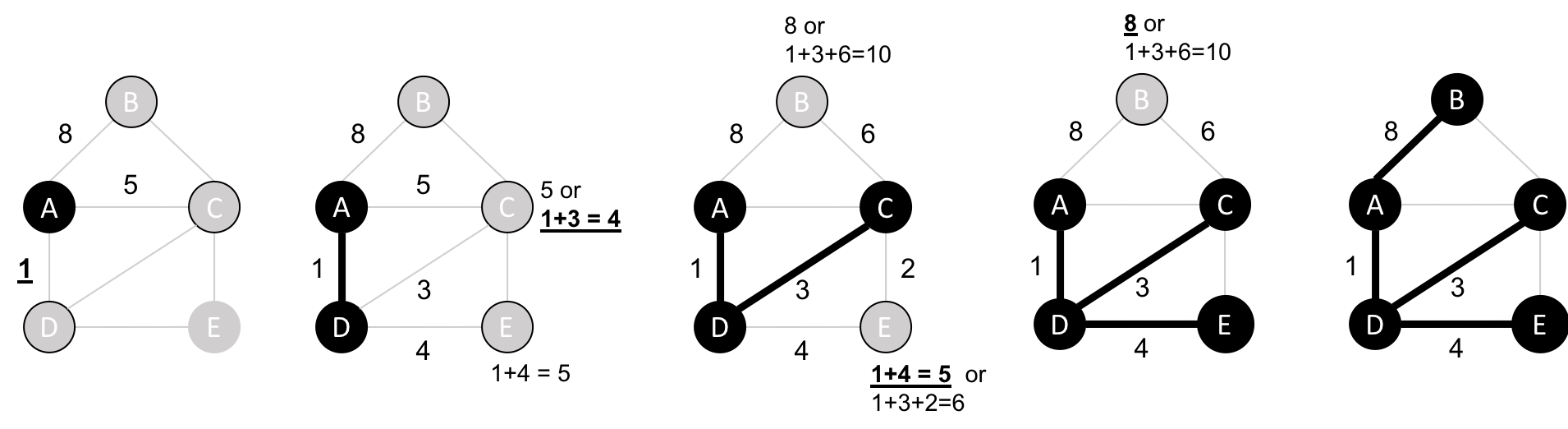

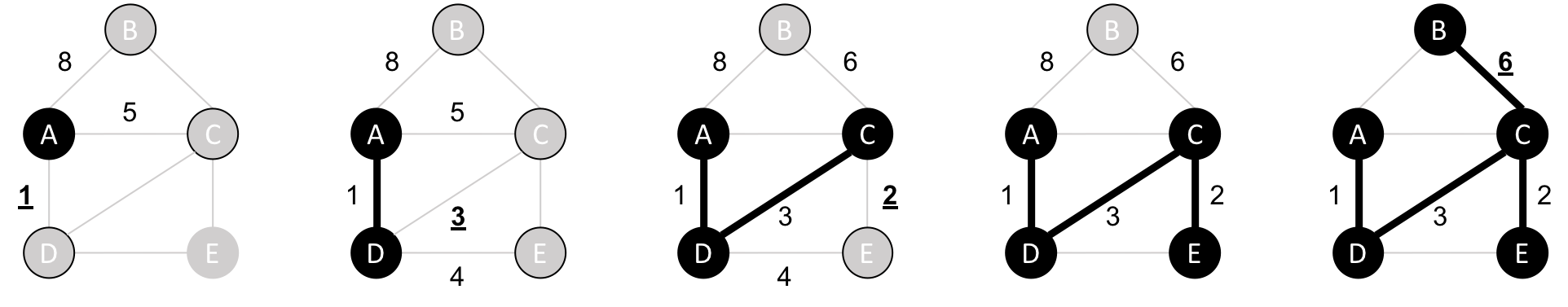

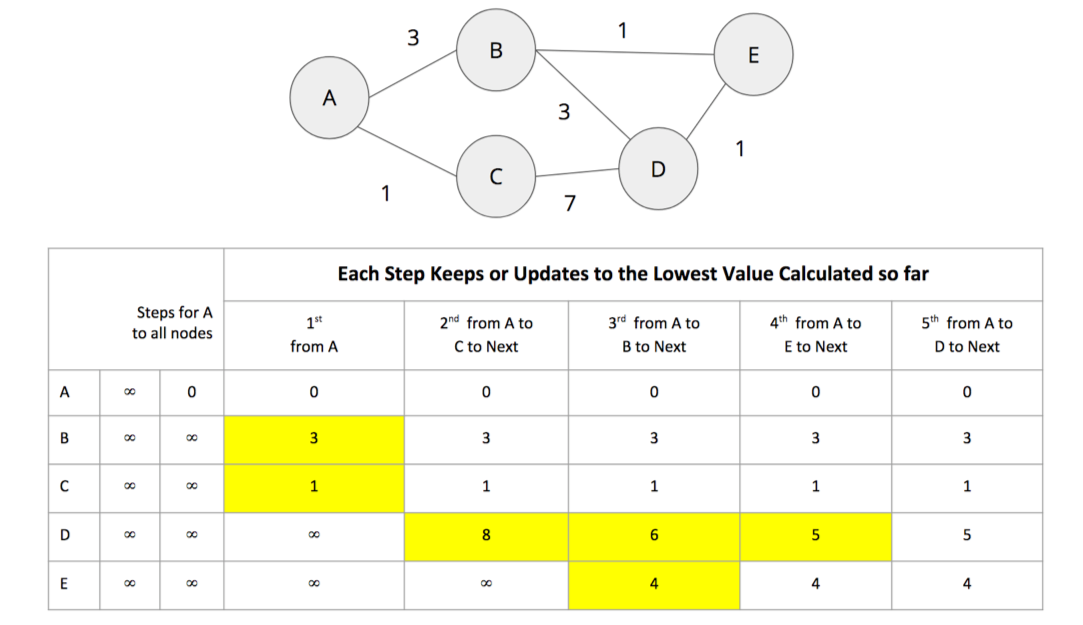

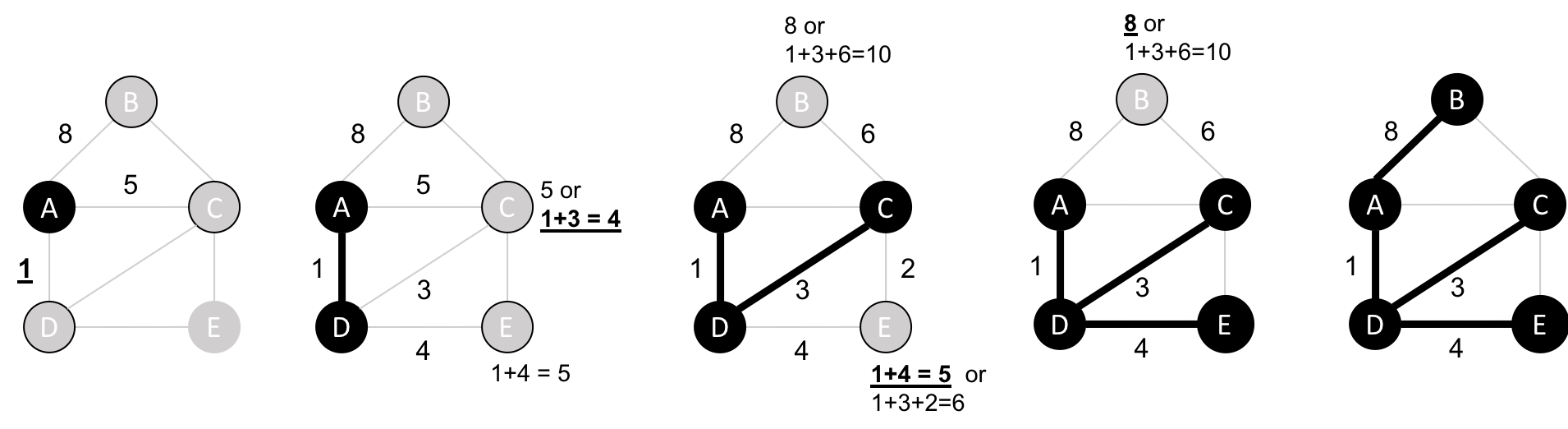

Dijkstra’s Shortest Path operates by first finding the lowest weight relationship from the start node to directly connected nodes. It keeps track of those weights and moves to the “closest” node. It then performs the same calculation but now as a cumulative total from the start node. The algorithm continues to do this, evaluating a “wave” of cumulative weights and always choosing the lowest cumulative path to advance along. It reaches the destination node.

You’ll notice in graph analytics the use of the terms weight, cost, distance, and hop when describing relationships and paths. “Weight” is the numeric value of a particular property of a relationship. “Cost” is similarly used but is more often when considering the total weight of a path.

“Distance” is often used within an algorithm as the name of the relationship property that indicates the cost of traversing between a pair of nodes. It’s not required that this be an actual physical measure of distance. “Hop” is commonly used to express the number of relationships between two nodes. You may see some of these terms combined such as, “it’s a 5-hop distance to London,” or, “that’s the lowest cost for the distance.”

Use Shortest Path to find optimal routes between a pair of nodes, based on either the number of hops or any weighted relationship value. For example, it can provide real-time answers about degrees of separation, the shortest distance between points, or the least expensive route. You can also use this algorithm to simply explore the connections between particular nodes.

Example use cases include:

Finding directions between locations: Web mapping tools such as Google Maps use the Shortest Path algorithm, or a close variant, to provide driving directions.

Social networks to find the degrees of separation between people. For example, when you view someone’s profile on LinkedIn, it will indicate how many people separate you in the graph, as well as listing your mutual connections.

The Bacon Number to find the number of degrees of separation between an actor and Kevin Bacon based on the movies they’ve appeared in. An example of this can be seen on the Oracle of Bacon 6 website. The Erdős Number Project 7 provides a similar graph analysis based on collaboration with Paul Erdős, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 20th century.

Dijkstra does not support negative weights. The algorithm assumes that adding a relationship to a path can never make a path shorter—an invariant that would be violated with negative weights.

In the Breadth First Search with Apache Spark section we learned how to find the shortest path between two nodes. That shortest path was based on hops and therefore isn’t the same as the shortest weighted path, which would tell us the shortest total distance between cities.

If we want to find the shortest weighted path (i.e. distance) we need to use the cost property, which is used for various types of weighting.

This option is not available out of the box with GraphFrames, so we need to write our own version of weighted shortest path using its aggregateMessages framework 8.

More information on aggregateMessages can be found in the Message passing via AggregateMessages 9 section of the GraphFrames user guide.

When available, we recommend you leverage pre-existing and tested libraries. Writing your own functions, especially for more complicated algorithms, require a deeper understanding of your data and calculations.

Before we create our function, we’ll import some libraries that we’ll use:

fromscripts.aggregate_messagesimportAggregateMessagesasAMfrompyspark.sqlimportfunctionsasF

The aggregate_messages module contains some useful helper functions.

It’s part of the GraphFrames library but isn’t available in a published artefact at the time of writing.

We’ve copied the module 10 into the book’s GitHub repository so that we can use it in our examples.

Now let’s write our function. We first create a User Defined Function that we’ll use to build the paths between our source and destination:

add_path_udf=F.udf(lambdapath,id:path+[id],ArrayType(StringType()))

And now for the main function which calculates the shortest path starting from an origin and returns as soon as the destination has been visited:

defshortest_path(g,origin,destination,column_name="cost"):ifg.vertices.filter(g.vertices.id==destination).count()==0:return(spark.createDataFrame(sc.emptyRDD(),g.vertices.schema).withColumn("path",F.array()))vertices=(g.vertices.withColumn("visited",F.lit(False)).withColumn("distance",F.when(g.vertices["id"]==origin,0).otherwise(float("inf"))).withColumn("path",F.array()))cached_vertices=AM.getCachedDataFrame(vertices)g2=GraphFrame(cached_vertices,g.edges)whileg2.vertices.filter('visited == False').first():current_node_id=g2.vertices.filter('visited == False').sort("distance").first().idmsg_distance=AM.edge[column_name]+AM.src['distance']msg_path=add_path_udf(AM.src["path"],AM.src["id"])msg_for_dst=F.when(AM.src['id']==current_node_id,F.struct(msg_distance,msg_path))new_distances=g2.aggregateMessages(F.min(AM.msg).alias("aggMess"),sendToDst=msg_for_dst)new_visited_col=F.when(g2.vertices.visited|(g2.vertices.id==current_node_id),True).otherwise(False)new_distance_col=F.when(new_distances["aggMess"].isNotNull()&(new_distances.aggMess["col1"]<g2.vertices.distance),new_distances.aggMess["col1"])\.otherwise(g2.vertices.distance)new_path_col=F.when(new_distances["aggMess"].isNotNull()&(new_distances.aggMess["col1"]<g2.vertices.distance),new_distances.aggMess["col2"].cast("array<string>"))\.otherwise(g2.vertices.path)new_vertices=(g2.vertices.join(new_distances,on="id",how="left_outer").drop(new_distances["id"]).withColumn("visited",new_visited_col).withColumn("newDistance",new_distance_col).withColumn("newPath",new_path_col).drop("aggMess","distance","path").withColumnRenamed('newDistance','distance').withColumnRenamed('newPath','path'))cached_new_vertices=AM.getCachedDataFrame(new_vertices)g2=GraphFrame(cached_new_vertices,g2.edges)ifg2.vertices.filter(g2.vertices.id==destination).first().visited:return(g2.vertices.filter(g2.vertices.id==destination).withColumn("newPath",add_path_udf("path","id")).drop("visited","path").withColumnRenamed("newPath","path"))return(spark.createDataFrame(sc.emptyRDD(),g.vertices.schema).withColumn("path",F.array()))

If we store references to any DataFrames in our functions we need to cache them using the AM.getCachedDataFrame function or we’ll encounter a memory leak when we execute the function.

In the shortest_path function we use this function to cache the vertices and new_vertices DataFrames.

If we want to find the shortest path between Amsterdam and Colchester we could call that function like so:

result=shortest_path(g,"Amsterdam","Colchester","cost")result.select("id","distance","path").show(truncate=False)

which would return the following results:

| id | distance | path |

|---|---|---|

Colchester |

347.0 |

[Amsterdam, Den Haag, Hoek van Holland, Felixstowe, Ipswich, Colchester] |

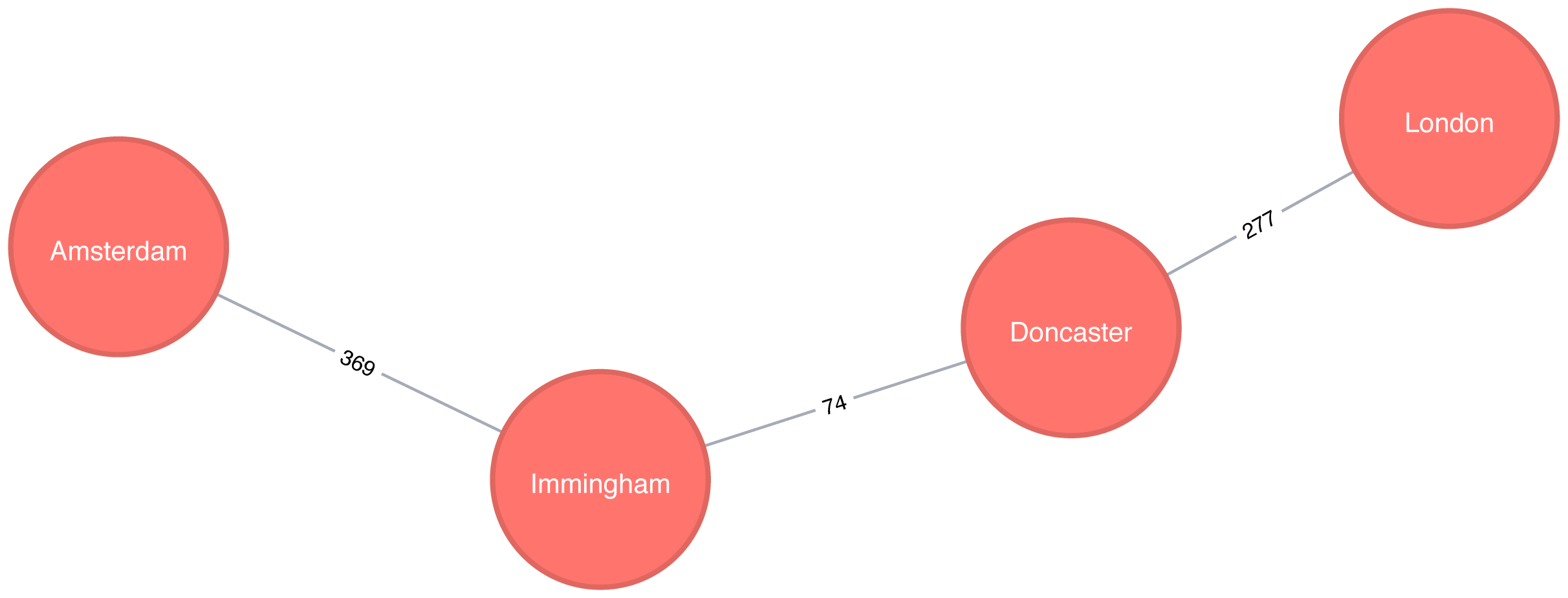

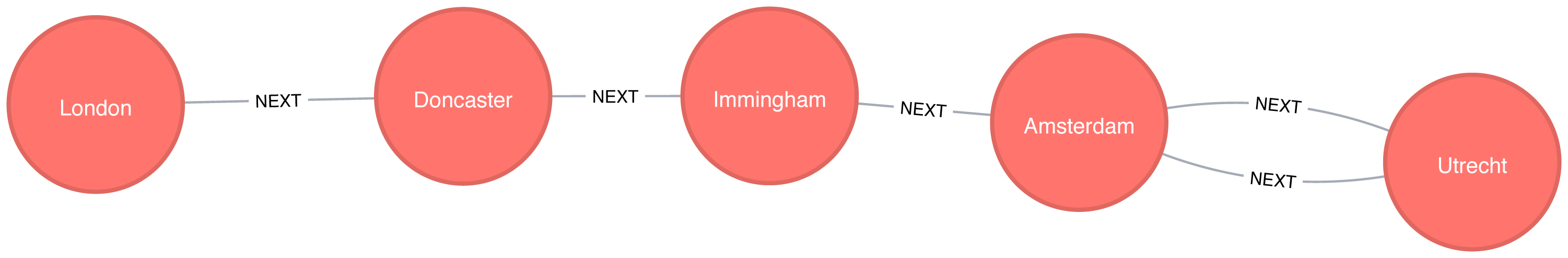

The total distance of the shortest path between Amsterdam and Colchester is 347 km and takes us via Den Haag, Hoek van Holland, Felixstowe, and Ipswich. By contrast the shortest path in terms of number of relationships between the locations, which we worked out with the Breadth First Search algorithm (refer back to Figure 4-4), would take us via Immingham, Doncaster, and London.

The Neo4j Graph Algorithms library also has a built-in shortest weighted path procedure that we can use.

All of Neo4j’s shortest path algorithms assume that the underlying graph is undirected.

You can override this by passing in the parameter direction: "OUTGOING" or direction: "INCOMING".

We can execute the weighted shortest path algorithm to find the shortest path between Amsterdam and London like this:

MATCH(source:Place {id:"Amsterdam"}),(destination:Place {id:"London"})CALL algo.shortestPath.stream(source, destination,"distance")YIELD nodeId, costRETURNalgo.getNodeById(nodeId).idASplace, cost

The parameters passed to this algorithm are:

source–the node where our shortest path search begins

destination–the node where our shortest path ends

distance–the name of the relationship property that indicates the cost of traversing between a pair of nodes.

The cost is the number of kilometers between two locations.

The query returns the following result:

| place | cost |

|---|---|

Amsterdam |

0.0 |

Den Haag |

59.0 |

Hoek van Holland |

86.0 |

Felixstowe |

293.0 |

Ipswich |

315.0 |

Colchester |

347.0 |

London |

453.0 |

The quickest route takes us via Den Haag, Hoek van Holland, Felixstowe, Ipswich, and Colchester! The cost shown is the cumulative total as we progress through cities. First, we go from Amsterdam to Den Haag, at a cost of 59. Then, we go from Den Haag to Hoek van Holland, at a cumulative cost of 86–and so on. Finally, we arrive from Colchester to London, for a total cost of 45 km.

We can also run an unweighted shortest path in Neo4j.

To have Neo4j’s shortest path algorithm do this we can pass null as the 3rd parameter to the procedure.

The algorithm will then assume a default weight of 1.0 for each relationship.

MATCH(source:Place {id:"Amsterdam"}),(destination:Place {id:"London"})CALL algo.shortestPath.stream(source, destination,null)YIELD nodeId, costRETURNalgo.getNodeById(nodeId).idASplace, cost

This query returns the following output:

| place | cost |

|---|---|

Amsterdam |

0.0 |

Immingham |

1.0 |

Doncaster |

2.0 |

London |

3.0 |

Here the cost is the cumulative total for relationships (or hops.) This is the same path as we would see using Breadth First Search in Spark.

We could even work out the total distance of following this path by writing a bit of post processing Cypher. The following procedure calculates the shortest unweighted path and then works out what the actual cost of that path would be:

MATCH(source:Place {id:"Amsterdam"}),(destination:Place {id:"London"})CALL algo.shortestPath.stream(source, destination,null)YIELD nodeId, costWITHcollect(algo.getNodeById(nodeId))ASpathUNWINDrange(0, size(path)-1)ASindexWITHpath[index]AScurrent, path[index+1]ASnextWITHcurrent, next, [(current)-[r:EROAD]-(next) | r.distance][0]ASdistanceWITHcollect({current: current, next:next, distance: distance})ASstopsUNWINDrange(0, size(stops)-1)ASindexWITHstops[index]ASlocation, stops, indexRETURNlocation.current.idASplace,reduce(acc=0.0,distancein[stopinstops[0..index] | stop.distance] |acc + distance)AScost

It’s a bit unwieldy-the tricky part is figuring out how to massage the data in such a way that we can see the cumulative cost over the whole journey. The query returns the following result:

| place | cost |

|---|---|

Amsterdam |

0.0 |

Immingham |

369.0 |

Doncaster |

443.0 |

London |

720.0 |

Figure 4-6 shows the unweighted shortest path from Amsterdam to London. It has a total cost of 720 km, routing us through the fewest number of cities. The weighted shortest path, however, had a total cost of 453 km even though we visited more towns.

The A* algorithm improves on Dijkstra’s algorithm, by finding shortest paths more quickly. It does this by allowing the inclusion of extra information that the algorithm can use, as part of a heuristic function, when determining which paths to explore next.

The algorithm was invented by Peter Hart, Nils Nilsson, and Bertram Raphael and described in their 1968 paper “A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths” 11.

The A* algorithm operates by determining which of its partial paths to expand at each iteration of its main loop. It does so based on an estimate of the cost still to go to the goal node.

A* selects the path that minimizes the following function:

f(n) = g(n) + h(n)

where :

g(n) - the cost of the path from the starting point to node n.

h(n) - the estimated cost of the path from node n to the destination node, as computed by a heuristic.

In Neo4j’s implementation, geospatial distance is used as the heuristic. In our example transportation dataset we use the latitude and longitude of each location as part of the heuristic function.

The following query executes the A* algorithm to find the shortest path between Den Haag and London:

MATCH(source:Place {id:"Den Haag"}),(destination:Place {id:"London"})CALL algo.shortestPath.astar.stream(source, destination,"distance","latitude","longitude")YIELD nodeId, costRETURNalgo.getNodeById(nodeId).idASplace, cost

The parameters passed to this algorithm are:

source-the node where our shortest path search begins

destination-the node where our shortest path search ends

distance-the name of the relationship property that indicates the cost of traversing between a pair of nodes. The cost is the number of kilometers between two locations.

latitude-the name of the node property used to represent the latitude of each node as part of the geospatial heuristic calculation

longitude-the name of the node property used to represent the longitude of each node as part of the geospatial heuristic calculation

Running this procedure gives the following result:

| place | cost |

|---|---|

Den Haag |

0.0 |

Hoek van Holland |

27.0 |

Felixstowe |

234.0 |

Ipswich |

256.0 |

Colchester |

288.0 |

London |

394.0 |

We’d get the same result using the Shortest Path algorithm, but on more complex datasets the A* algorithm will be faster as it evaluates fewer paths.

Yen’s algorithm is similar to the shortest path algorithm, but rather than finding just the shortest path between two pairs of nodes, it also calculates the 2nd shortest path, 3rd shortest path, up to k-1 deviations of shortest paths.

Jin Y. Yen invented the algorithm in 1971 and described it in “Finding the K Shortest Loopless Paths in a Network” 12. This algorithm is useful for getting alternative paths when finding the absolute shortest path isn’t our only goal.

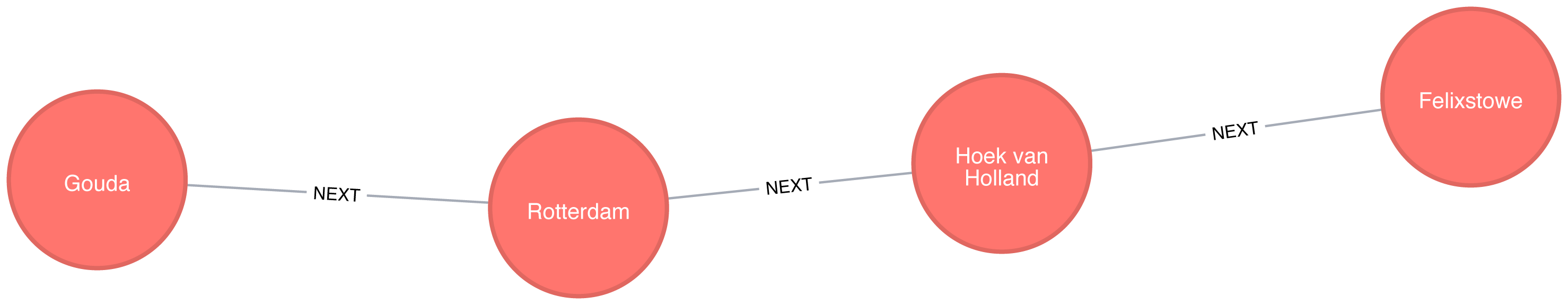

The following query executes the Yen’s algorithm to find the shortest paths between Gouda and Felixstowe.

MATCH(start:Place {id:"Gouda"}),(end:Place {id:"Felixstowe"})CALL algo.kShortestPaths.stream(start, end, 5,'distance')YIELD index, nodeIds, path, costsRETURNindex,[node inalgo.getNodesById(nodeIds[1..-1]) |node.id]ASvia,reduce(acc=0.0, costincosts | acc + cost)AStotalCost

The parameters passed to this algorithm are:

start-the node where our shortest path search begins

end-the node where our shortest path search ends

5-the maximum number of shortest paths to find

distance-the name of the relationship property that indicates the cost of traversing between a pair of nodes. The cost is the number of kilometers between two locations.

After we get back the shortest paths we look up the associated node for each node id and then we filter out the start and end nodes from the collection.

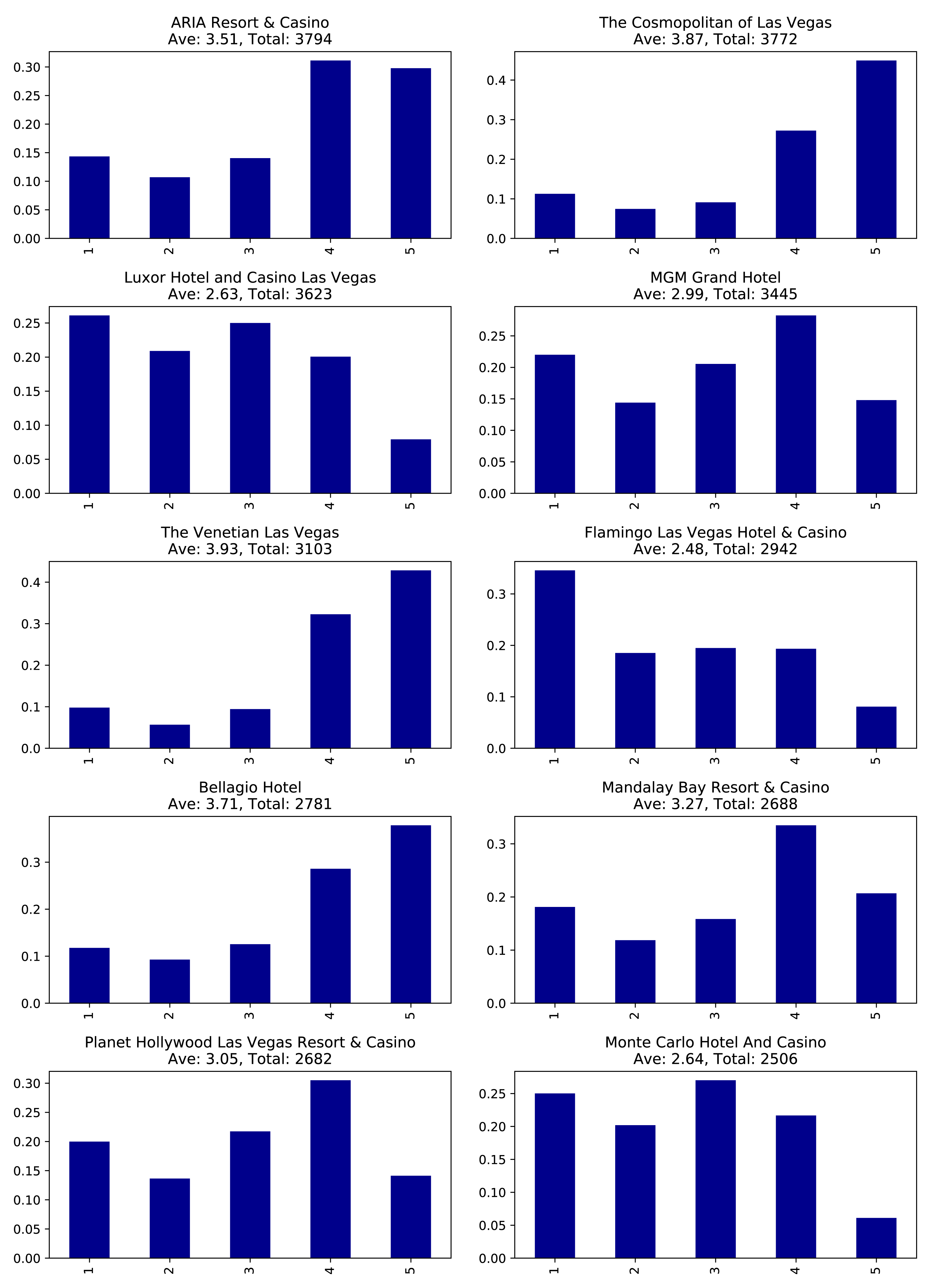

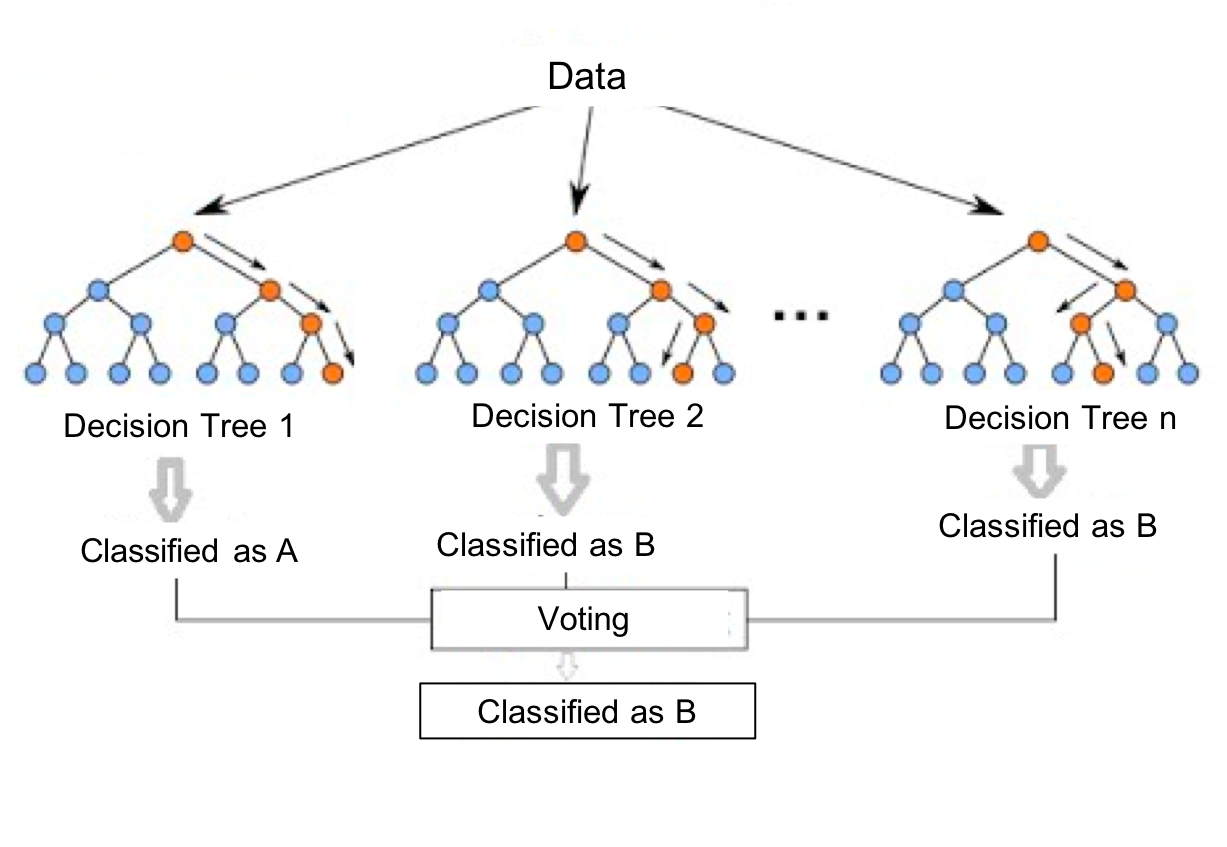

Running this procedure gives the following result: