Chapter 10. Graphics

Introduction

Graphics is a great strength of R. The graphics package is part of the

standard distribution and contains many useful functions for creating a

variety of graphic displays. The base functionality has been expanded

and made easier with ggplot2, part of the tidyverse of packages. In

this chapter we will focus on examples using ggplot2, and we will

occasionally suggest other packages. In this chapter’s See Also sections

we mention functions in other packages that do the same job in a

different way. We suggest that you explore those alternatives if you are

dissatisfied with what’s offered by ggplot2 or base graphics.

Graphics is a vast subject, and we can only scratch the surface here.

Winston Chang’s R Graphics Cookbook, 2nd Edition is part of the

O’Reilly Cookbook series and walks through many useful recipes with a

focus on ggplot2. If you want to delve deeper, we recommend R

Graphics by Paul Murrell (Chapman & Hall, 2006). That book discusses

the paradigms behind R graphics, explains how to use the graphics

functions, and contains numerous examples—including the code to recreate

them. Some of the examples are pretty amazing.

The Illustrations

The graphs in this chapter are mostly plain and unadorned. We did that

intentionally. When you call the ggplot function, as in:

library(tidyverse)

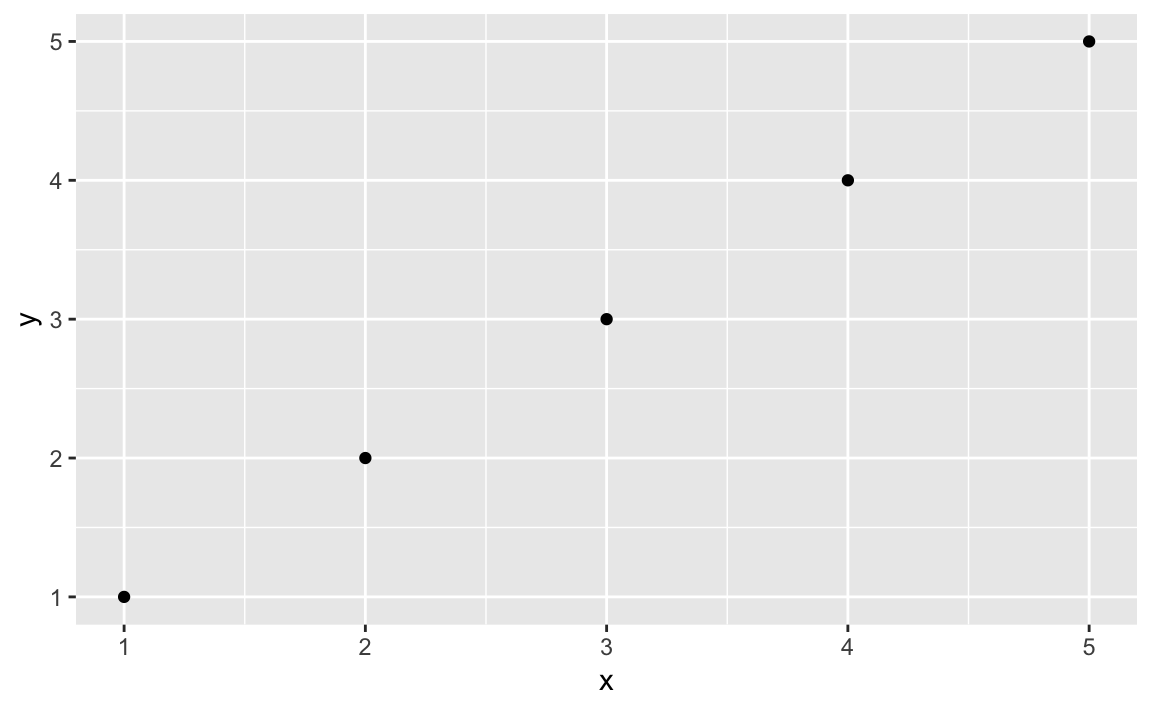

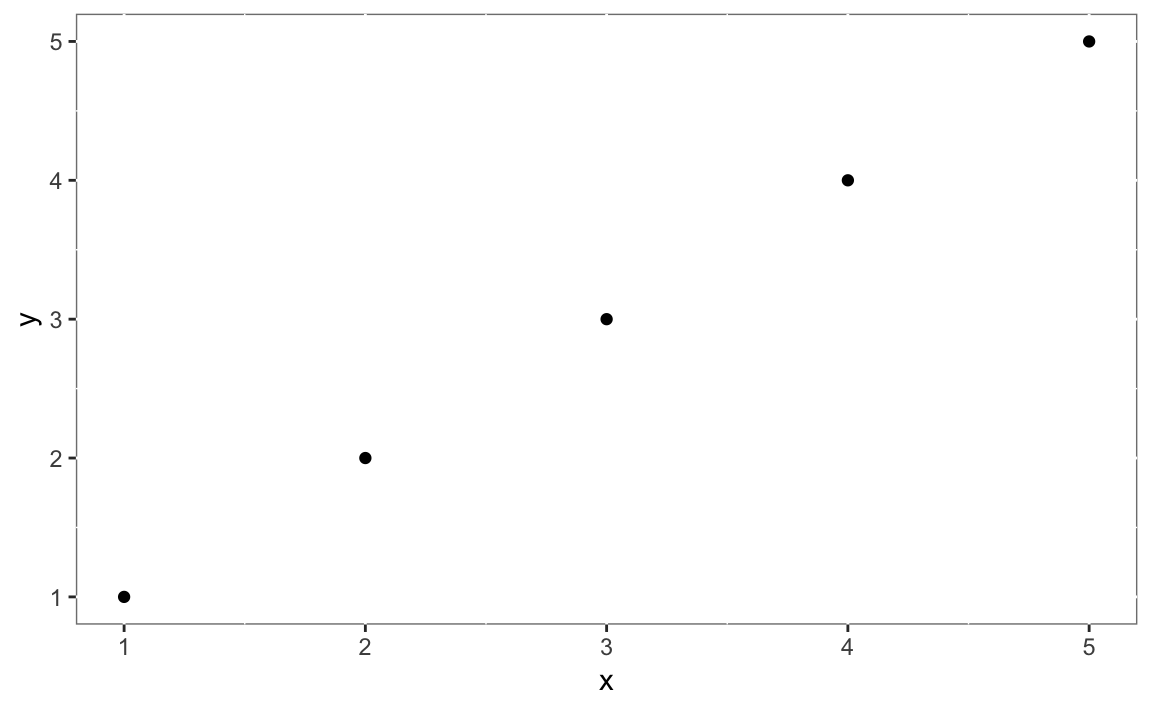

Figure 10-1. Simple Plot

df<-data.frame(x=1:5,y=1:5)ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()

you get a plain, graphical representation of x and y as shown in

Figure 10-1. You could adorn the graph with colors, a

title, labels, a legend, text, and so forth, but then the call to

ggplot becomes more and more crowded, obscuring the basic intention.

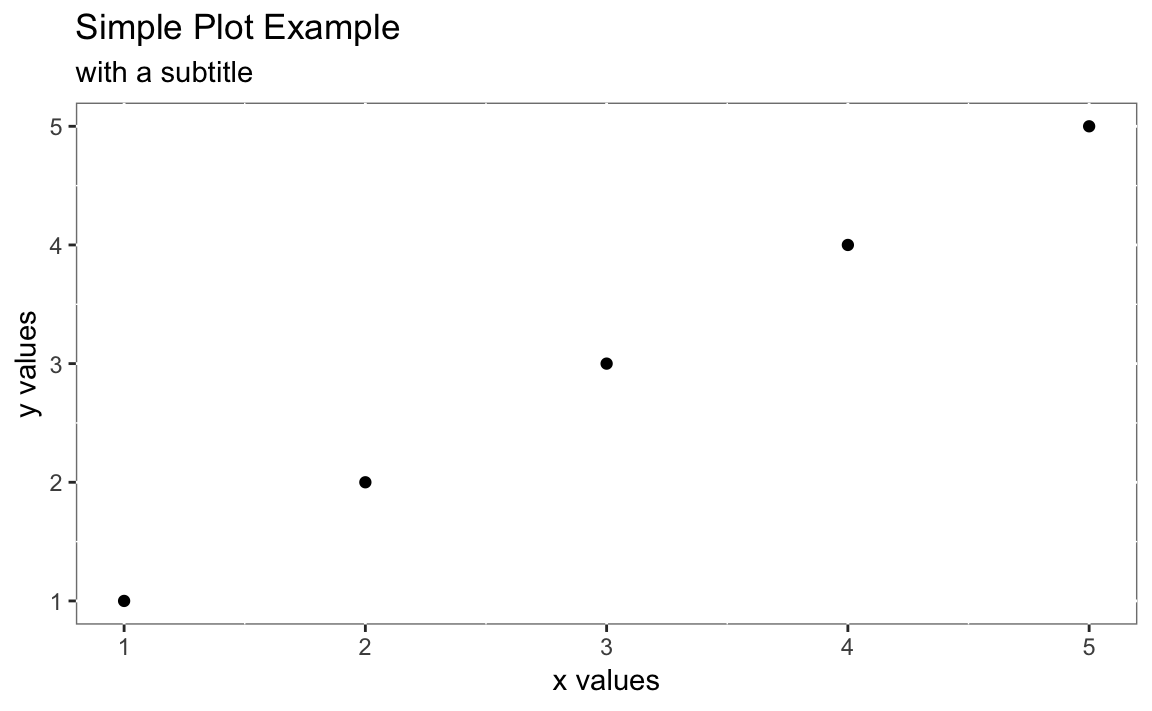

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()+labs(title="Simple Plot Example",subtitle="with a subtitle",x="x values",y="y values")+theme(panel.background=element_rect(fill="white",colour="grey50"))

Figure 10-2. Complicated Plot

The resulting plot is shown in Figure 10-2. We want to keep the recipes clean, so we emphasize the basic plot and then show later (as in “Adding a Title and Labels”) how to add adornments.

Notes on ggplot2 basics

While the package is called ggplot2 the primary plotting function in

the package is called ggplot. It is important to understand the basic

pieces of a ggplot2 graph. In the examples above you can see that we

pass data into ggplot then define how the graph is created by stacking

together small phrases that describe some aspect of the plot. This

stacking together of phrases is part of the “grammar of graphics” ethos

(that’s where the gg comes from). To learn more, you can read “The

Layered Grammar of Graphics” written by ggplot2 author, Hadley Wickham

(http://vita.had.co.nz/papers/layered-grammar.pdf). The “grammar of

graphics,” concept originating with Leland Wilkinson who articulated the

idea of building graphics up from a set of primitives (i.e. verbs and

nouns). With ggplot, the underlying data need not be fundamentally

reshaped for each type of graphical representation. In general, the data

stays the same and the user then changes syntax slightly to illustrate

the data differently. This is significantly more consistent than base

graphics which often require reshaping the data in order to change the

way the data is visualized.

As we talk about ggplot graphics it’s worth defining the things that

make up a ggplot graph:

geometric object functions-

These are geometric objects that describe the type of graph being created. These start with

geom_and examples includegeom_line,geom_boxplot, andgeom_pointalong with dozens more. aesthetics-

The aesthetics, or aesthetic mappings, communicate to

ggplotwhich fields in the source data get mapped to which visual elements in the graphic. This is theaes()line in aggplotcall. stats-

Stats are statistical transformations that are done before displaying the data. Not all graphs will have stats, but a few common stats are

stat_ecdf(the empirical cumulative distribution function) andstat_identitywhich tellsggplotto pass the data without doing any stats at all. facet functions-

Facets are subplots where each small plot represents a subgroup of the data. The faceting functions include

facet_wrapandfacet_grid. themes-

Themes are the visual elements of the plot that are not tied to data. These might include titles, margins, table of contents locations, or font choices.

layer-

A layer is a combination of data, aesthetics, a geometric object, a stat, and other options to produce a visual layer in the

ggplotgraphic.

“Long” vs. “Wide” data with ggplot

One of the first confusions new users to ggplot often face is that

they are inclined to reshape their data to be “wide” before plotting it.

Wide here meaning every variable they are plotting is its own column in

the underlying data frame.

ggplot works most easily with “long” data where additional variables

are added as rows in the data frame rather than columns. The great side

effect of adding additional measurements as rows is that any properly

constructed ggplot graphs will automatically update to reflect the new

data without changing the ggplot code. If each additional variable was

added as a column, then the plotting code would have to be changed to

introduce additional variables. This idea of “long” vs. “wide” data will

become more obvious in the examples in the rest of this chapter.

Graphics in Other Packages

R is highly programmable, and many people have extended its graphics

machinery with additional features. Quite often, packages include

specialized functions for plotting their results and objects. The zoo

package, for example, implements a time series object. If you create a

zoo object z and call plot(z), then the zoo package does the

plotting; it creates a graphic that is customized for displaying a time

series. Zoo uses base graphics so the resulting graph will not be a

ggplot graphic.

There are even entire packages devoted to extending R with new graphics

paradigms. The lattice package is an alternative to base graphics that

predates ggplot2. It uses a powerful graphics paradigm that enables

you to create informative graphics more easily. It was implemented by

Deepayan Sarkar, who also wrote Lattice: Multivariate Data

Visualization with R (Springer, 2008), which explains the package and

how to use it. The lattice package is also described in

R in a Nutshell (O’Reilly).

There are two chapters in Hadley Wickham’s excellent book R for Data

Science which deal with graphics. The first, “Exploratory Data

Analysis” focuses on exploring data with ggplot2 while “Graphics for

Communication” explores communicating to others with graphics. R for

Data Science is availiable in a printed version from O’Reilly Media or

online at http://r4ds.had.co.nz/graphics-for-communication.html.

Creating a Scatter Plot

Problem

You have paired observations: (x1, y1), (x2, y2), …, (xn, yn). You want to create a scatter plot of the pairs.

Solution

We can plot the data by calling ggplot, passing in the data frame, and

invoking a geometric point function:

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()

In this example, the data frame is called df and the x and y data

are in fields named x and y which we pass to the aesthetic in the

call aes(x, y).

Discussion

A scatter plot is a common first attack on a new dataset. It’s a quick way to see the relationship, if any, between x and y.

Plotting with ggplot requires telling ggplot what data frame to use,

then what type of graph to create, and which aesthetic mapping (aes) to

use . The aes in this case defines which field from df goes into

which axis on the plot. Then the command geom_point communicates that

you want a point graph, as opposed to a line or other type of graphic.

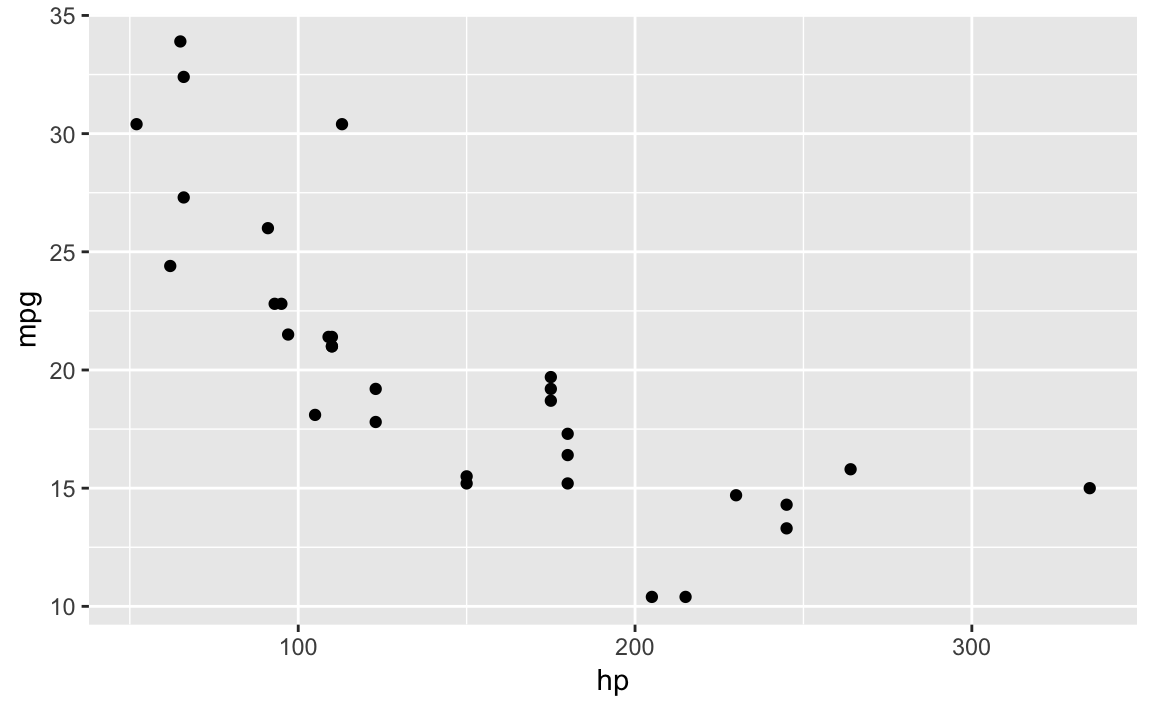

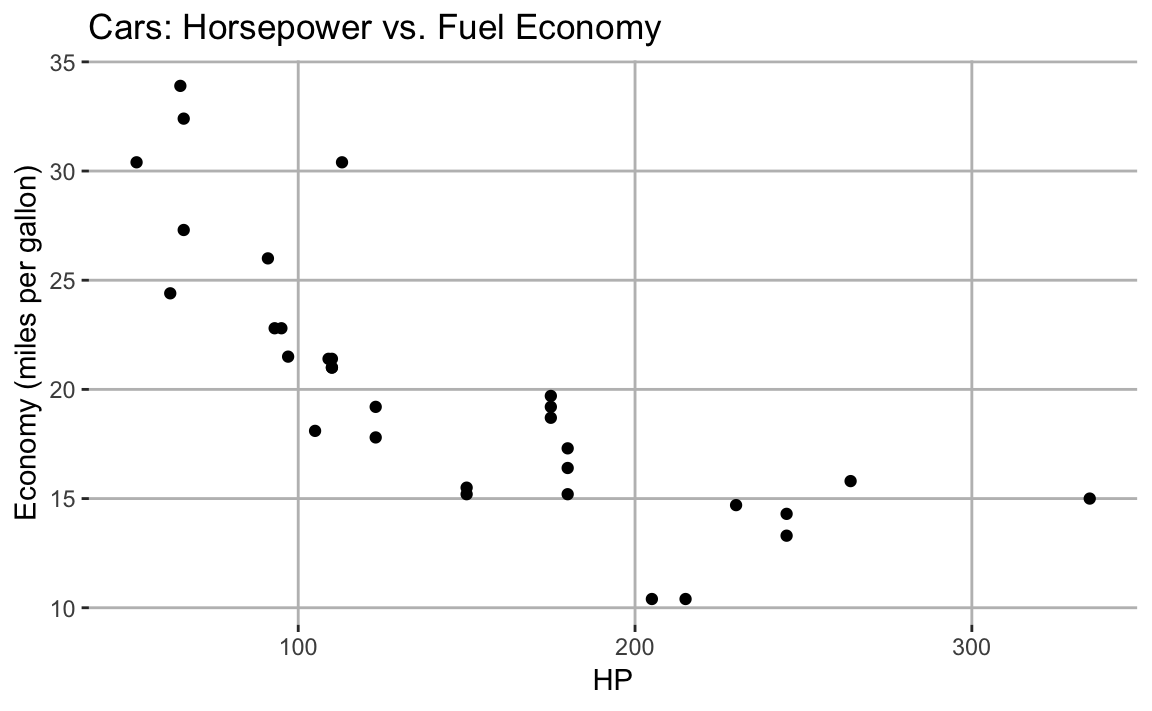

We can use the built in mtcars dataset to illustrate plotting

horsepower hp on the x axis and fuel economy mpg on the y:

ggplot(mtcars,aes(hp,mpg))+geom_point()

Figure 10-3. Scatter Plot Example

The resulting plot is shown in Figure 10-3.

See Also

See “Adding a Title and Labels” for adding a title and labels; see Recipes and for adding a grid and a legend (respectively). See “Plotting All Variables Against All Other Variables” for plotting multiple variables.

Adding a Title and Labels

Problem

You want to add a title to your plot or add labels for the axes.

Solution

With ggplot we add a labs element which controls the labels for the

title and axies.

When calling labs in ggplot:

: title The desired title text

: x x-axis label

: y: y-axis label

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()+labs(title="The Title",x="X-axis Label",y="Y-axis Label")

Discussion

The graph created in “Creating a Scatter Plot” is quite plain. A title and better labels will make it more interesting and easier to interpret.

Note that in ggplot you build up the elements of the graph by

connecting the parts with the plus sign +. So we add additional

graphical elements by stringing together phrases. You can see this in

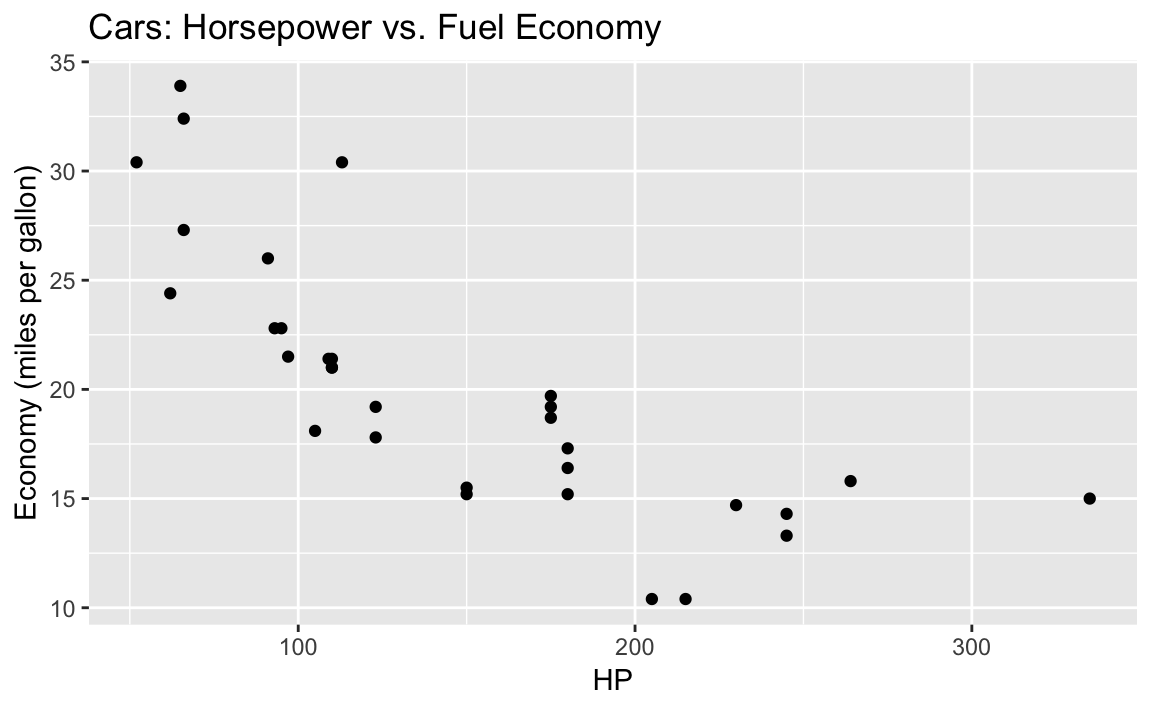

the following code that uses the built in cars dataset and plots speed

vs. stopping distance in a scatter plot, shown in Figure 10-4

ggplot(mtcars,aes(hp,mpg))+geom_point()+labs(title="Cars: Horsepower vs. Fuel Economy",x="HP",y="Economy (miles per gallon)")

Figure 10-4. Labeled Axis and Title

Adding (or Removing) a Grid

Problem

You want to change the background grid to your graphic.

Solution

With ggplot background grids come as a default, as you have seen in

other recipes. However we can alter the background grid using the

theme function or by applying a prepackaed theme to our graph.

We can use theme to alter the backgorund panel of our graphic:

ggplot(df)+geom_point(aes(x,y))+theme(panel.background=element_rect(fill="white",colour="grey50"))

Figure 10-5. White background

Discussion

ggplot fills in the background with a grey grid by default. So you may

find yourself wanting to remove that grid completely or change it to

something else. Let’s create a ggplot graphic and then incrementally

change the background style.

We can add or change aspects of our graphic by creating a ggplot

object then calling the object and using the + to add to it. The

background shading in a ggplot graphic is actually 3 different graph

elements:

panel.grid.major:

These are white by default and heavy

panel.grid.minor:

These are white by default and light

panel.background:

This is the background that is grey by default

You can see these elements if you look carefully at the background of Figure 10-4:

If we set the background as element_blank() then the major and minor

grids are there but they are white on white so we can’t see them in

???:

g1<-ggplot(mtcars,aes(hp,mpg))+geom_point()+labs(title="Cars: Horsepower vs. Fuel Economy",x="HP",y="Economy (miles per gallon)")+theme(panel.background=element_blank())g1

. image::images/10_Graphics_files/figure-html/examplebackground-1.png[]

Notice in the code above we put the ggplot graph into a variable

called g1. Then we printed the graphic by just calling g1. By having

the graph inside of g1 we can then add additional graphical components

without rebuilding the graph again.

But if we wanted to show the background grid in some bright colors for illustration, it’s as easy as setting them to a color and setting a line type which is shown in ???.

g2<-g1+theme(panel.grid.major=element_line(color="red",linetype=3))+# linetype = 3 is dashtheme(panel.grid.minor=element_line(color="blue",linetype=4))# linetype = 4 is dot dashg2

. image::images/10_Graphics_files/figure-html/majorgrid-1.png[]

??? lacks visual appeal, but you can cleary see that the red lines make up the major grid and the blue lines are the minor grid.

Or we could do something less garash and take the ggplot object g1

from above and add grey gridlines to the white background, shown in

Figure 10-6.

g1+theme(panel.grid.major=element_line(colour="grey"))

Figure 10-6. Grey Major Gridlines

Creating a Scatter Plot of Multiple Groups

Problem

You have data in a data frame with three observations per record: x, y, and a factor f that indicates the group. You want to create a scatter plot of x and y that distinguishes among the groups.

Solution

With ggplot we control the mapping of shapes to the factor f by

passing shape = f to the aes.

ggplot(df,aes(x,y,shape=f))+geom_point()

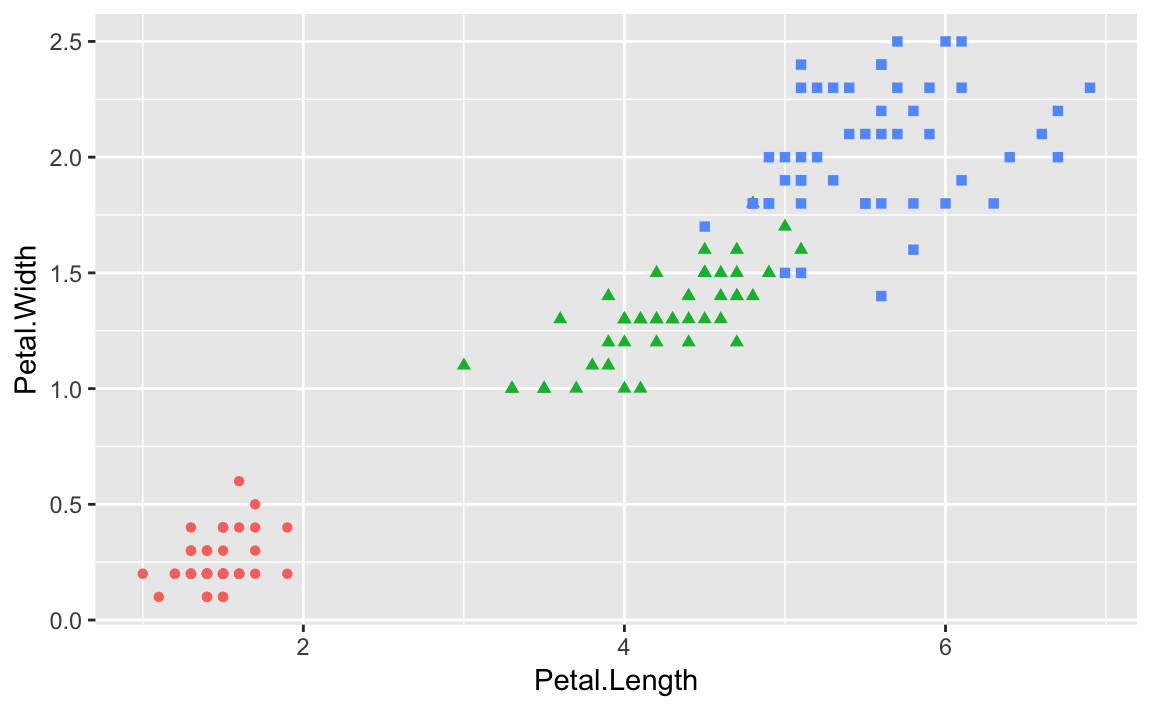

Discussion

Plotting multiple groups in one scatter plot creates an uninformative

mess unless we distinguish one group from another. This distinction is

done in ggplot by setting the shape parameter of the aes function.

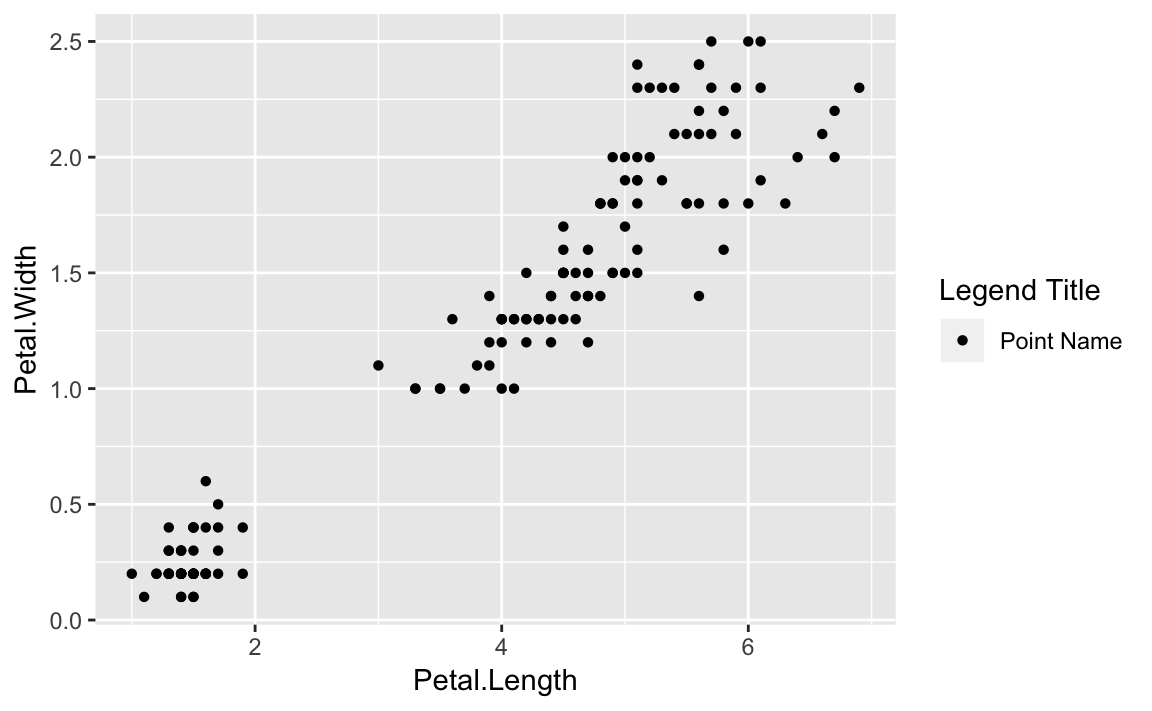

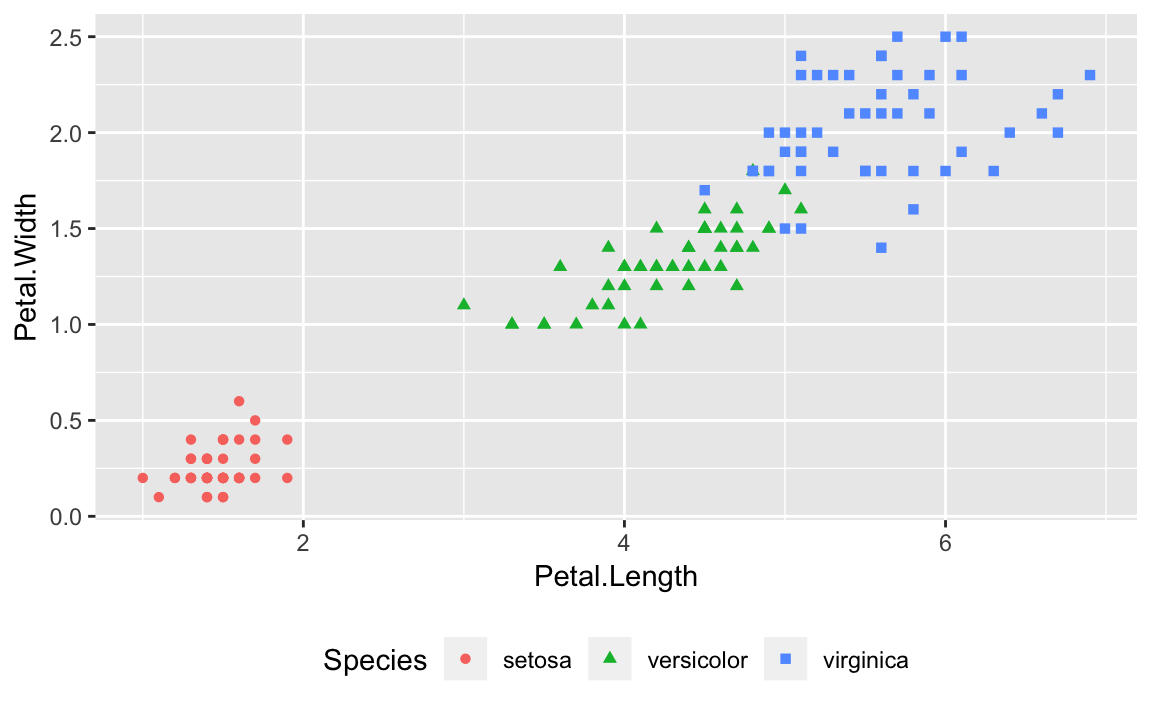

The built in iris dataset contains paired measures of Petal.Length

and Petal.Width. Each measurement also has a Species property

indicating the species of the flower that was measured. If we plot all

the data at once, we just get the scatter plot shown in ???:

ggplot(data=iris,aes(x=Petal.Length,y=Petal.Width))+geom_point()

. image::images/10_Graphics_files/figure-html/irisnoshape-1.png[]

The graphic would be far more informative if we distinguished the points

by species. In addition to distinguising species by shape, we could also

differentiate by color. We can add shape = Species and

color = Species to our aes call, to get each species with a

different shape and color, shown in ???.

ggplot(data=iris,aes(x=Petal.Length,y=Petal.Width,shape=Species,color=Species))+geom_point()

. image::images/10_Graphics_files/figure-html/irisshape-1.png[]

ggplot conveniently sets up a legend for you as well, which is handy.

See Also

See “Adding (or Removing) a Legend” to add a legend.

Adding (or Removing) a Legend

Problem

You want your plot to include a legend, the little box that decodes the graphic for the viewer.

Solution

In most cases ggplot will add the legends automatically, as you can

see in the previous recipe. If you do not have explicit grouping in the

aes then ggplot will not show a legend by default. If we want to

force ggplot to show a legend we can set the shape or linetype of our

graph to a constant. ggplot will then show a legend with one group. We

then use guides to guide ggplot in how to label the legend.

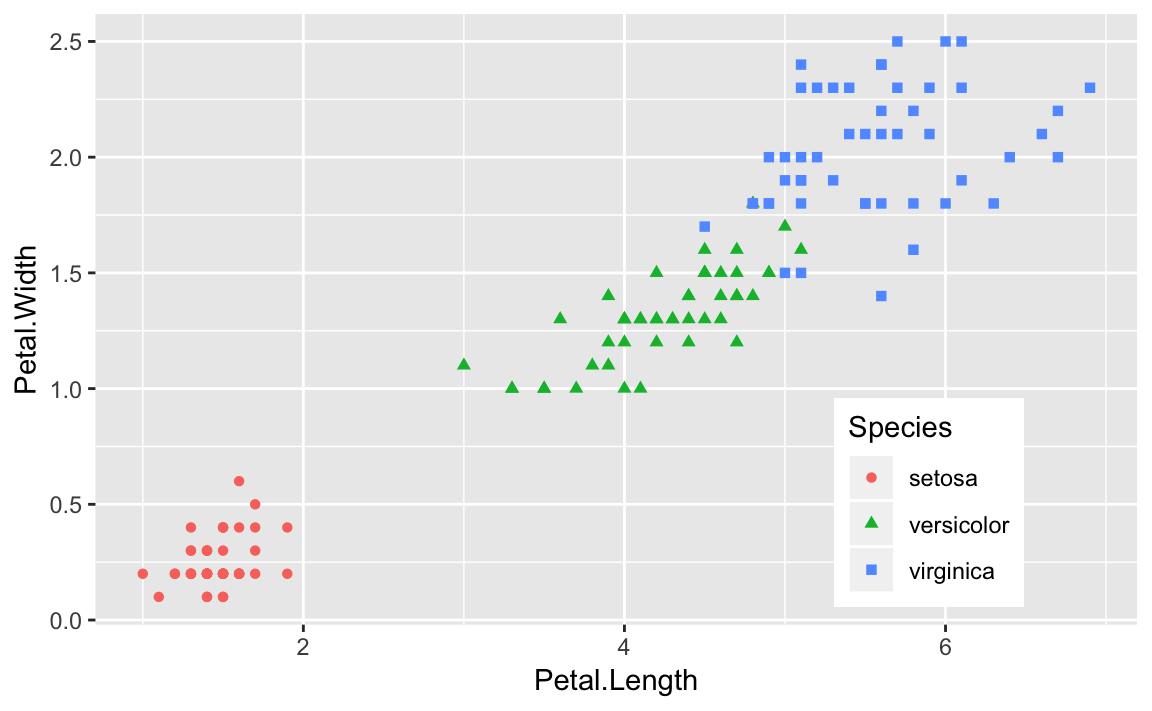

This can be illustrated with our iris scatterplot:

g<-ggplot(data=iris,aes(x=Petal.Length,y=Petal.Width,shape="Point Name"))+geom_point()+guides(shape=guide_legend(title="Legend Title"))g

Figure 10-7. Legend Added

Figure 10-7 illustrates the result of setting the shape

to a string value then relabeling the legend using guides.

More commonly, you may want to turn legends off which can be done by

setting the legend.position = "none" in the theme. We can use the

iris plot from the prior recipe and add the theme call as shown in

Figure 10-8:

g<-ggplot(data=iris,aes(x=Petal.Length,y=Petal.Width,shape=Species,color=Species))+geom_point()+theme(legend.position="none")g

Figure 10-8. Legend Removed

Discussion

Adding legends to ggplot when there is no grouping is an excercise in

tricking ggplot into showing the legend by passing a string to a

grouping parameter in aes. This will not change the grouping as there

is only one group, but will result in a legend being shown with a name.

Then we can use guides to alter the legend title. It’s worth noting

that we are not changing anything about the data, just exploiting

settings in order to coerce ggplot into showing a legend when it

typically would not.

One of the huge benefits of ggplot is its very good defaults. Getting

positions and correspondence between labels and their point types is

done automatically, but can be overridden if needed. To remove a legend

totally, we set theme parameters with

theme(legend.position = "none"). In addition to “none” you can set the

legend.position to be "left", "right", "bottom", "top", or a

two-element numeric vector. Use a two-element numeric vector in order to

pass ggplot specific coordinates of where you want the legend. If

using the coordinate positions the values passed are between 0 and 1 for

x and y position, respectivly.

An example of a legend positioned at the bottom is in Figure 10-9 created with this adjustment to the

legend.poisition:

g+theme(legend.position="bottom")

Figure 10-9. Legend on the Bottom

Or we could use the two-element numeric vector to put the legend in a specific location as in Figure 10-10. The example puts the center of the legend at 80% to the right and 20% up from the bottom.

g+theme(legend.position=c(.8,.2))

Figure 10-10. Legend at a Point

In many aspects beyond legends, ggplot uses sane defaults with

flexibility to override those and tweak the details. More detail of

ggplot options related to legends can be found in the help for theme

by typing ?theme or looking in the ggplot online reference material:

Plotting the Regression Line of a Scatter Plot

Problem

You are plotting pairs of data points, and you want to add a line that illustrates their linear regression.

Solution

Using ggplot there is no need to calculate the linear model first

using the R lm function. We can instead use the geom_smooth function

to calculate the linear regression inside of our ggplot call.

If our data is in a data frame df and the x and y data are in

columns x and y we plot the regression line like this:

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()+geom_smooth(method="lm",formula=y~x,se=FALSE)

The se = FALSE parameter tells ggplot not to plot the standard error

bands around our regression line.

Discussion

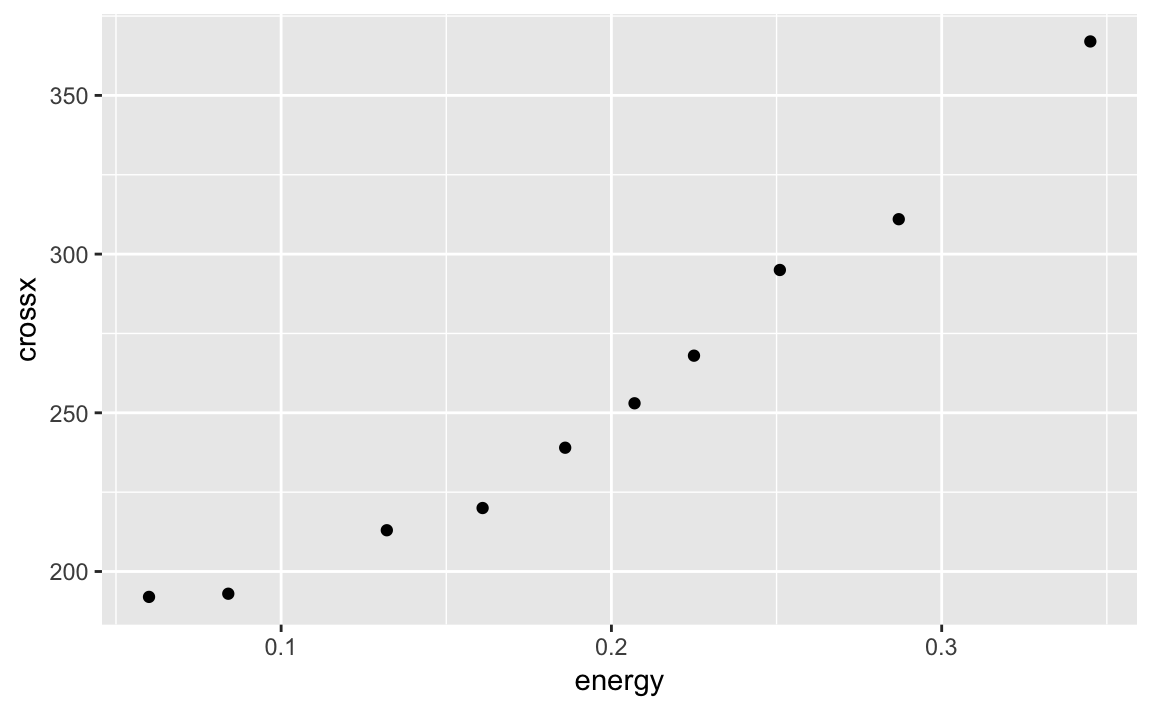

Suppose we are modeling the strongx dataset found in the faraway

package. We can create a linear model using the built in lm function

in R. We can predict the variable crossx as a linear function of

energy. First, lets look at a simple scatter plot of our data:

library(faraway)data(strongx)ggplot(strongx,aes(energy,crossx))+geom_point()

Figure 10-11. Strongx Scatter Plot

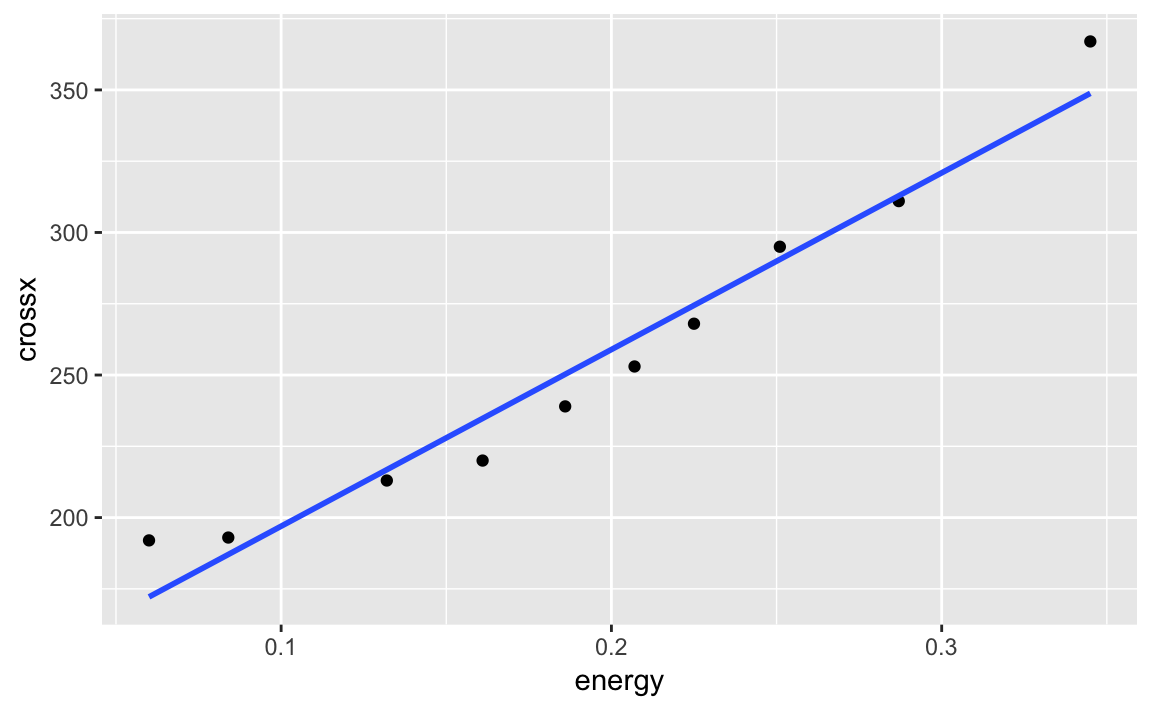

ggplot can calculate a linear model on the fly and then plot the

regression line along with our data:

g<-ggplot(strongx,aes(energy,crossx))+geom_point()g+geom_smooth(method="lm",formula=y~x,se=FALSE)

We can turn the confidence bands on by omitting the se = FALSE option

as as shown in ???:

g+geom_smooth(method="lm",formula=y~x)

. image::images/10_Graphics_files/figure-html/one-step-nose-1.png[]

Notice that in the geom_smooth we use x and y rather than the

variable names. ggplot has set the x and y inside the plot based

on the aesthetic. Multiple smoothing methods are supported by

geom_smooth. You can explore those, and other options in the help by

typing ?geom_smooth.

If we had a line we wanted to plot that was stored in another R object,

we could use geom_abline to plot the line on our graph. In the

following example we pull the intercept term and the slope from the

regression model m and add those to our graph:

m<-lm(crossx~energy,data=strongx)ggplot(strongx,aes(energy,crossx))+geom_point()+geom_abline(intercept=m$coefficients[1],slope=m$coefficients[2])

This produces a very similar plot to ???. The

geom_abline method can be handy if you are plotting a line from a

source other than a simple linear model.

See Also

See the chapter on Linear Regression and

ANOVA for more about linear regression and the lm function.

Plotting All Variables Against All Other Variables

Problem

Your dataset contains multiple numeric variables. You want to see scatter plots for all pairs of variables.

Solution

ggplot does not have any built in method to create pairs plots,

however, the package GGally provides the functionality with the

ggpairs function:

library(GGally)ggpairs(df)

Discussion

When you have a large number of variables, finding interrelationships

between them is difficult. One useful technique is looking at scatter

plots of all pairs of variables. This would be quite tedious if coded

pair-by-pair, but the ggpairs function from the package GGally

provides an easy way to produce all those scatter plots at once.

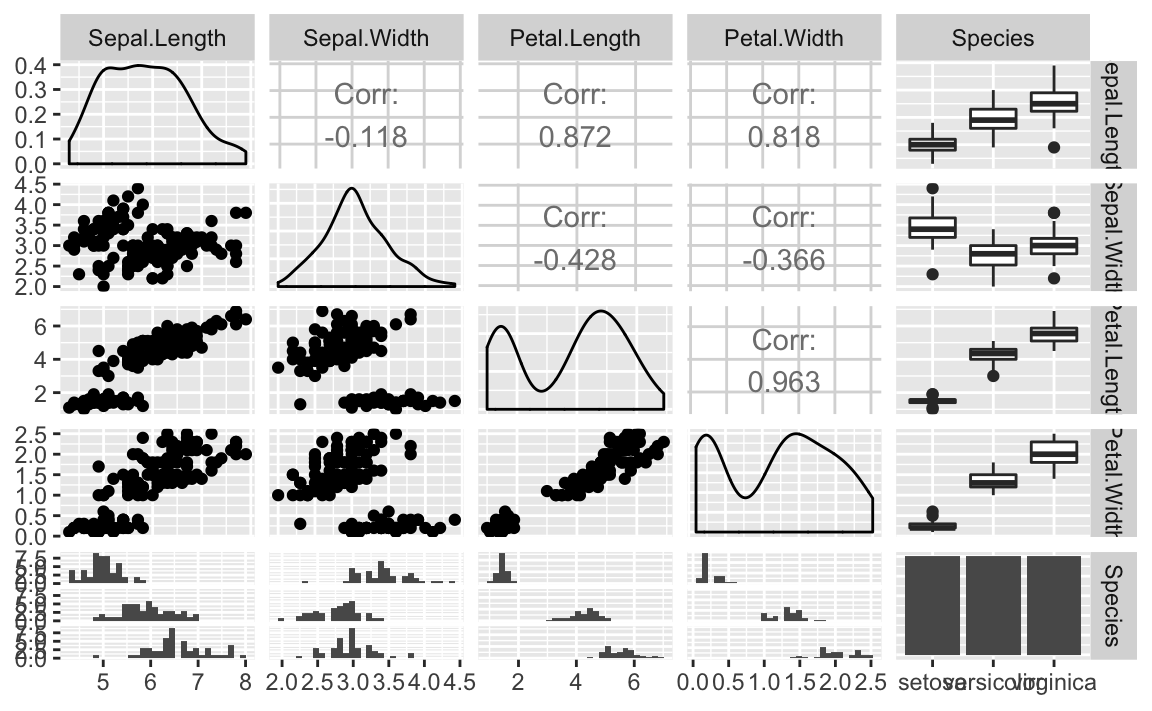

The iris dataset contains four numeric variables and one categorical

variable:

head(iris)#> Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species#> 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa#> 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa#> 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa#> 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa#> 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa#> 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa

What is the relationship, if any, between the columns? Plotting the

columns with ggpairs produces multiple scatter plots.

library(GGally)ggpairs(iris)

Figure 10-12. ggpairs Plot of Iris Data

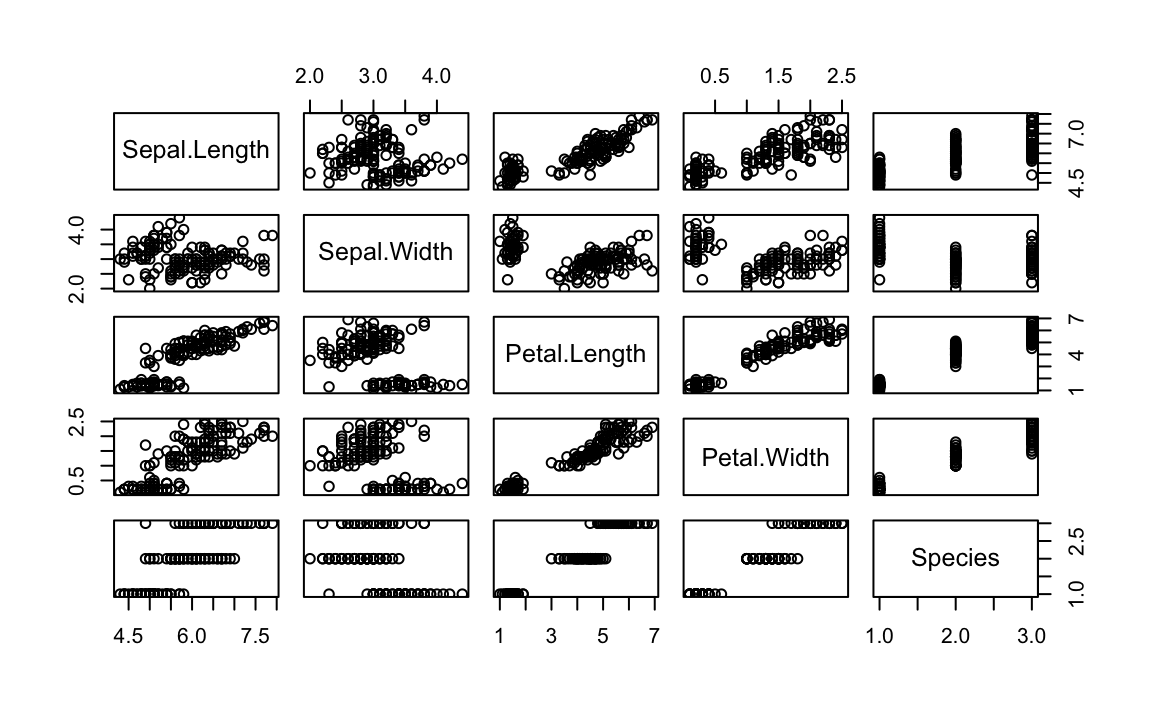

The ggpairs function is pretty, but not particularly fast. If you’re

just doing interactive work and want a quick peak at the data, the base

R plot function provides faster output and is shown in Figure 10-13.

plot(iris)

Figure 10-13. Base plot() Pairs Plot

While the ggpairs function is not as fast to plot as the Base R plot

function, it produces density graphs on the diagonal and reports

correlation in the upper triangle of the graph. When factors or

character columns are present, ggpairs produces histograms on the

lower triangle of the graph and boxplots on the upper triangle. These

are nice additions to understanding relationships in your data.

Creating One Scatter Plot for Each Factor Level

Problem

Your dataset contains (at least) two numeric variables and a factor. You want to create several scatter plots for the numeric variables, with one scatter plot for each level of the factor.

Solution

This kind of plot is called a conditioning plot, which is produced in

ggplot by adding facet_wrap to our plot. In this example we use the

data frame df which contains three columns: x, y, and f with f

being a factor (or a character).

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()+facet_wrap(~f)

Discussion

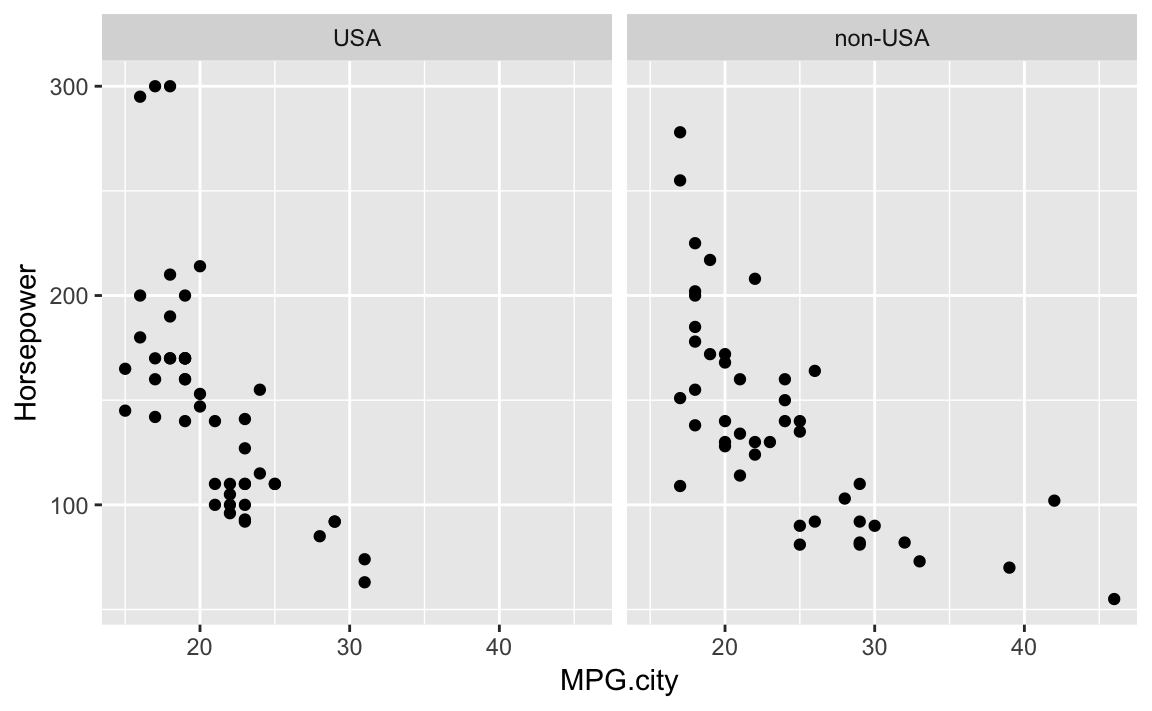

Conditioning plots (coplots) are another way to explore and illustrate the effect of a factor or to compare different groups to each other.

The Cars93 dataset contains 27 variables describing 93 car models as

of 1993. Two numeric variables are MPG.city, the miles per gallon in

the city, and Horsepower, the engine horsepower. One categorical

variable is Origin, which can be USA or non-USA according to where the

model was built.

Exploring the relationship between MPG and horsepower, we might ask: Is there a different relationship for USA models and non-USA models?

Let’s examine this as a facet plot:

data(Cars93,package="MASS")ggplot(data=Cars93,aes(MPG.city,Horsepower))+geom_point()+facet_wrap(~Origin)

Figure 10-14. Cars Data with Facet

The resulting plot in Figure 10-13 reveals a few insights. If we really crave that 300-horsepower monster then we’ll have to buy a car built in the USA; but if we want high MPG, we have more choices among non-USA models. These insights could be teased out of a statistical analysis, but the visual presentation reveals them much more quickly.

Note that using facet results in subplots with the same x and y

axis ranges. This helps insure that visual inspection of the data is not

misleading because of differeing axis ranges.

See Also

The Base R Graphics function coplot can accomplish very similar plots

using only Base Graphics.

Creating a Bar Chart

Problem

You want to create a bar chart.

Solution

A common situation is to have a column of data that represents a group and then another column that represents a measure about that group. This format is “long” data because the data runs vertically instead of having a column for each group.

Using the geom_bar function in ggplot we can plot the heights as

bars. If the data is already aggregated, we add stat = "identity" so

that ggplot knows it needs to do no aggregation on the groups of

values before plotting.

ggplot(data=df,aes(x,y))+geom_bar(stat="identity")

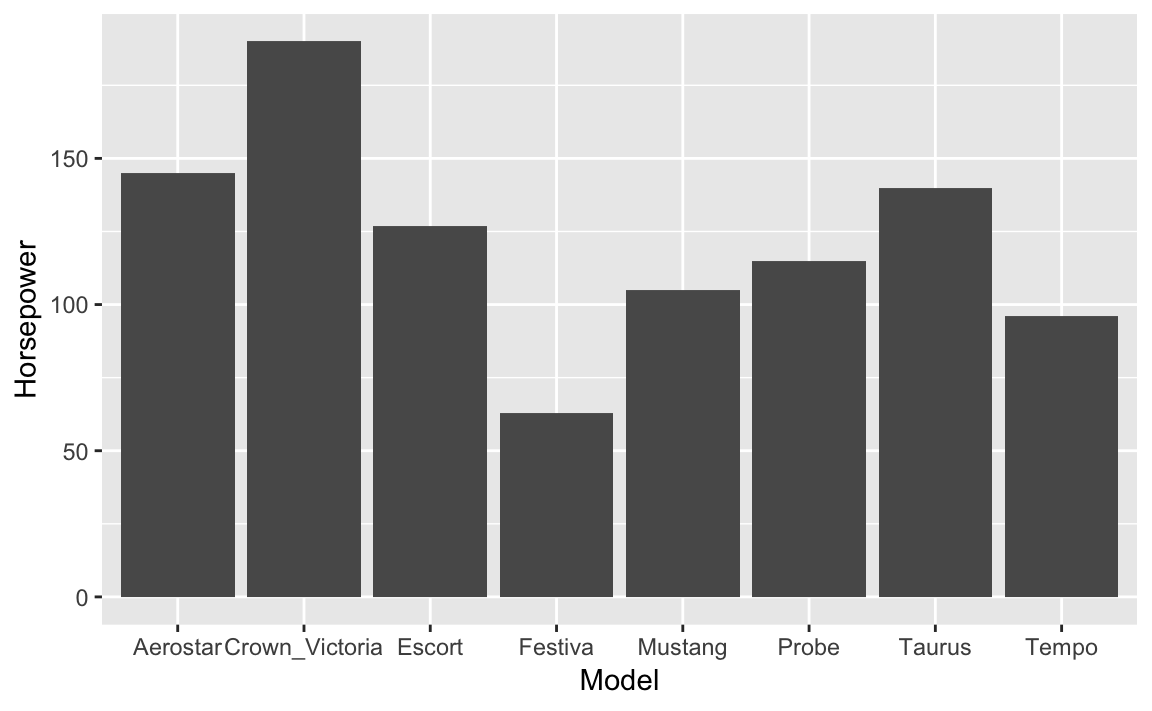

Discussion

Let’s use the cars made by Ford in the Cars93 data in an example:

ford_cars<-Cars93%>%filter(Manufacturer=="Ford")ggplot(ford_cars,aes(Model,Horsepower))+geom_bar(stat="identity")

Figure 10-15. Ford Cars Bar Chart

The resulting graph in Figure 10-15 shows the resuting bar chart.

This example above uses stat = "identity" which assumes that the

heights of your bars are conveniently stored as a value in one field

with only one record per column. That is not always the case, however.

Often you have a vector of numeric data and a parallel factor or

character field that groups the data, and you want to produce a bar

chart of the group means or the group totals.

Let’s work up an example using the built-in airquality dataset which

contains daily temperature data for a single location for five months.

The data frame has a numeric Temp column and Month and Day

columns. If we want to plot the mean temp by month using ggplot we

don’t need to precompute the mean, instead we can have ggplot do that

in the plot command logic. To tell ggplot to calculate the mean we

pass stat = "summary", fun.y = "mean" to the geom_bar command. We

can also turn the month numbers into dates using the built in constant

month.abb which contains the abbreviations for the months.

ggplot(airquality,aes(month.abb[Month],Temp))+geom_bar(stat="summary",fun.y="mean")+labs(title="Mean Temp by Month",x="",y="Temp (deg. F)")

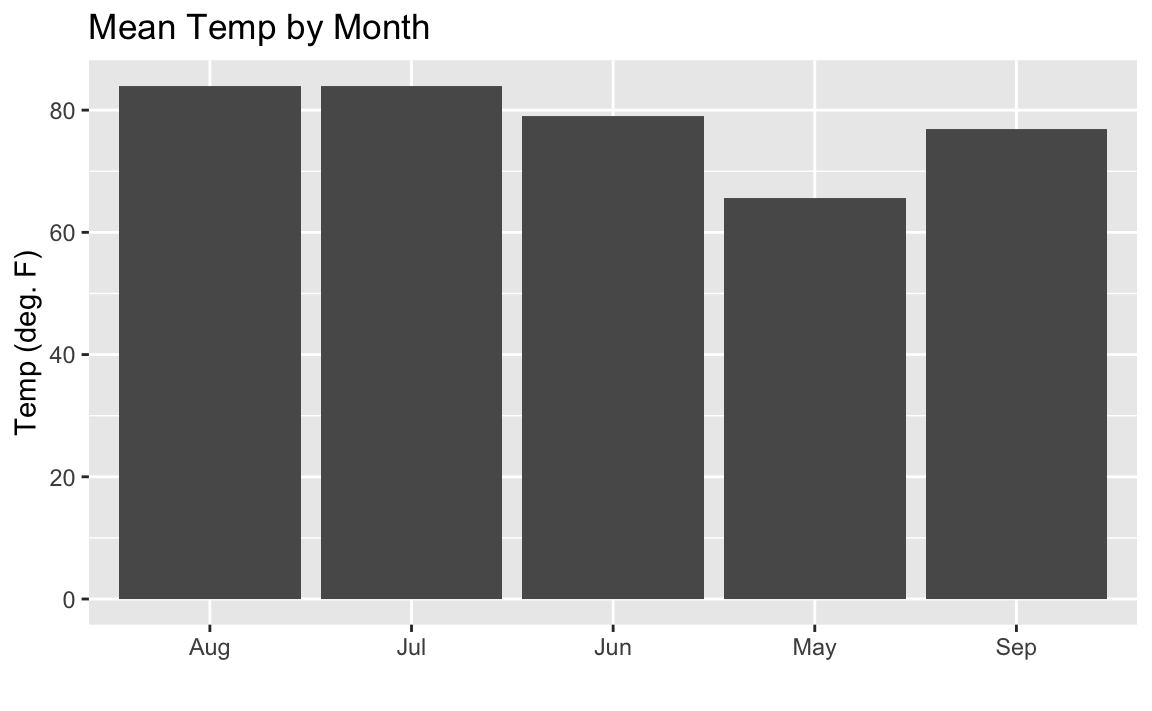

Figure 10-16. Bar Chart: Temp by Month

Figure 10-16 shows the resulting plot. But you might notice the sort order on the months is alphabetical, which is not how we typically like to see months sorted.

We can fix the sorting issue using a few functions from dplyr combined

with fct_inorder from the forcats Tidyverse package. To get the

months in the correct order we can sort the data frame by Month which

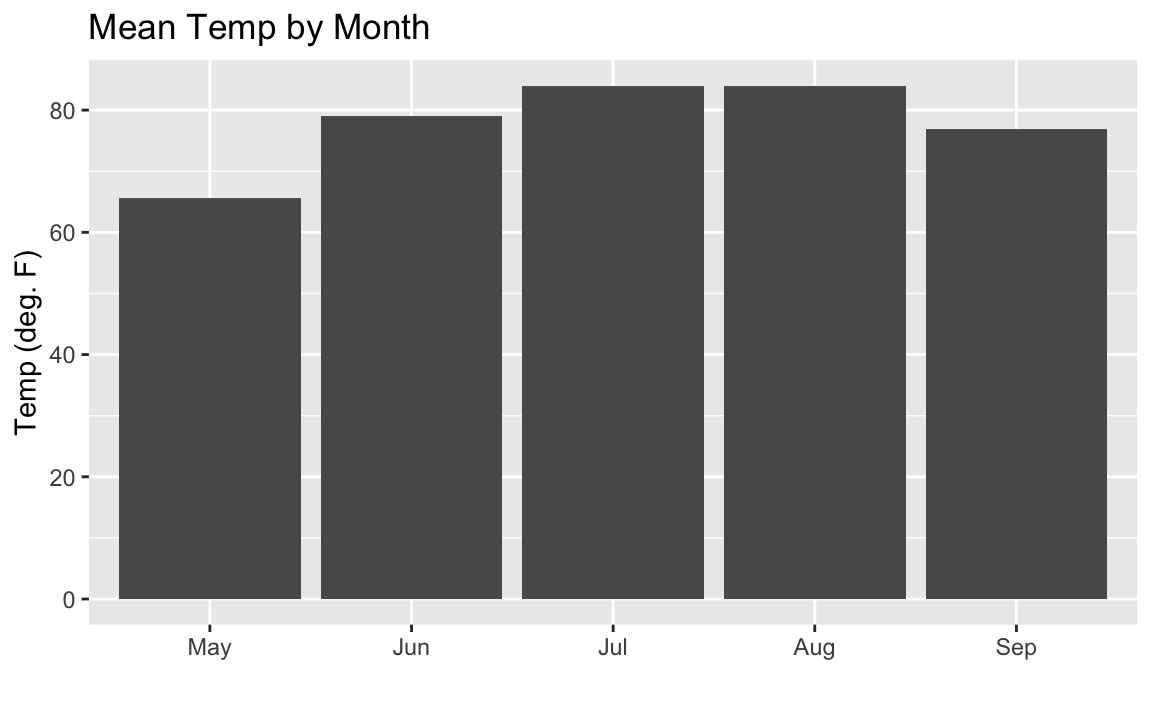

is the month number, then we can apply fct_inorder which will arrange

our factors in the order they appear in the data. You can see in Figure 10-17 that the bars are now sorted properly.

aq_data<-airquality%>%arrange(Month)%>%mutate(month_abb=fct_inorder(month.abb[Month]))ggplot(aq_data,aes(month_abb,Temp))+geom_bar(stat="summary",fun.y="mean")+labs(title="Mean Temp by Month",x="",y="Temp (deg. F)")

Figure 10-17. Bar Chart Properly Sorted

See Also

See “Adding Confidence Intervals to a Bar Chart” for adding confidence intervals and “Coloring a Bar Chart” for adding color

?geom_bar for help with bar charts in ggplot

barplot for Base R bar charts or the barchart function in the

lattice package.

Adding Confidence Intervals to a Bar Chart

Problem

You want to augment a bar chart with confidence intervals.

Solution

Suppose you have a data frame df with columns group which are group

names, stat which is a column of statistics, and lower and upper

which represent the corresponding limits for the confidence intervals.

We can display a bar chart of stat for each group and its confidence

intervals using the geom_bar combined with geom_errorbar.

ggplot(df,aes(group,stat))+geom_bar(stat="identity")+geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=lower,ymax=upper),width=.2)

. image::images/10_Graphics_files/figure-html/confbars-1.png[]

??? shows the resulting bar chart with confidence intervals.

Discussion

Most bar charts display point estimates, which are shown by the heights of the bars, but rarely do they include confidence intervals. Our inner statisticians dislike this intensely. The point estimate is only half of the story; the confidence interval gives the full story.

Fortunately, we can plot the error bars using ggplot. The hard part is

calculating the intervals. In the examples above our data had a simple

-15% and +20% interval. However, in “Creating a Bar Chart”, we calculated group means before plotting them. If we let

ggplot do the calculations for us we can use the build in mean_se

along with the stat_summary function to get the standard errors of the

mean measures.

Let’s use the airquality data we used previously. First we’ll do the

sorted factor procedure (from the prior recipe) to get the month names

in the desired order:

aq_data<-airquality%>%arrange(Month)%>%mutate(month_abb=fct_inorder(month.abb[Month]))

Now we can plot the bars along with the associated standard errors as in the following:

ggplot(aq_data,aes(month_abb,Temp))+geom_bar(stat="summary",fun.y="mean",fill="cornflowerblue")+stat_summary(fun.data=mean_se,geom="errorbar")+labs(title="Mean Temp by Month",x="",y="Temp (deg. F)")

Sometimes you’ll want to sort your columns in your bar chart in

descending order based on their height. This can be a little bit

confusing when using summary stats in ggplot but the secret is to use

mean in the reorder statement to sort the factor by the mean of the

temp. Note that the reference to mean in reorder is not quoted,

while the reference to mean in geom_bar is quoted:

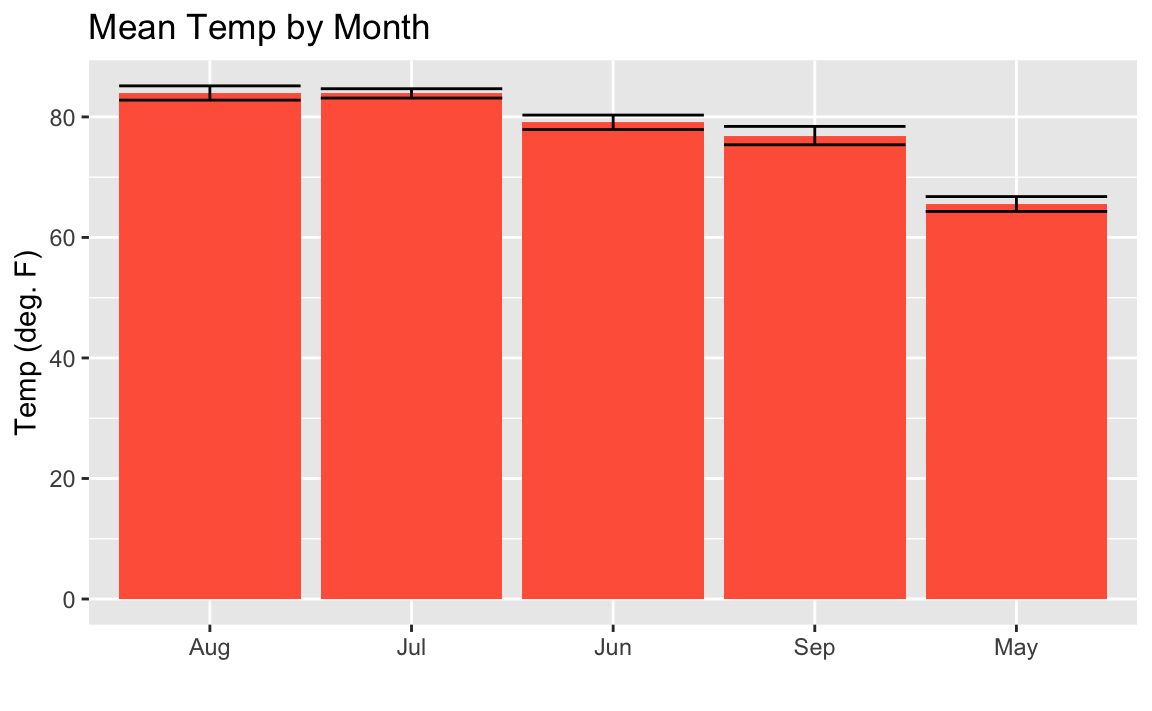

ggplot(aq_data,aes(reorder(month_abb,-Temp,mean),Temp))+geom_bar(stat="summary",fun.y="mean",fill="tomato")+stat_summary(fun.data=mean_se,geom="errorbar")+labs(title="Mean Temp by Month",x="",y="Temp (deg. F)")

Figure 10-18. Mean Temp By Month Descending Order

You may look at this example and the result in Figure 10-18

and wonder, “Why didn’t they just use reorder(month_abb, Month) in the

first example instead of that sorting business with

forcats::fct_inorder to get the months in the right order?” Well, we

could have. But sorting using fct_inorder is a design pattern that

provides flexibility for more complicated things. Plus it’s quite easy

to read in a script. Using reorder inside the aes is a bit more

dense and hard to read later. But either approach is reasonable.

See Also

See “Forming a Confidence Interval for a Mean” for

more about t.test.

Coloring a Bar Chart

Problem

You want to color or shade the bars of a bar chart.

Solution

With gplot we add the fill= call to our aes and let ggplot pick

the colors for us:

ggplot(df,aes(x,y,fill=group))

Discussion

In ggplot we can use the fill parameter in aes to tell ggplot

what field to base the colors on. If we pass a numeric field to ggplot

we will get a continuous gradient of colors and if we pass a factor or

character field to fill we will get contrasting colors for each group.

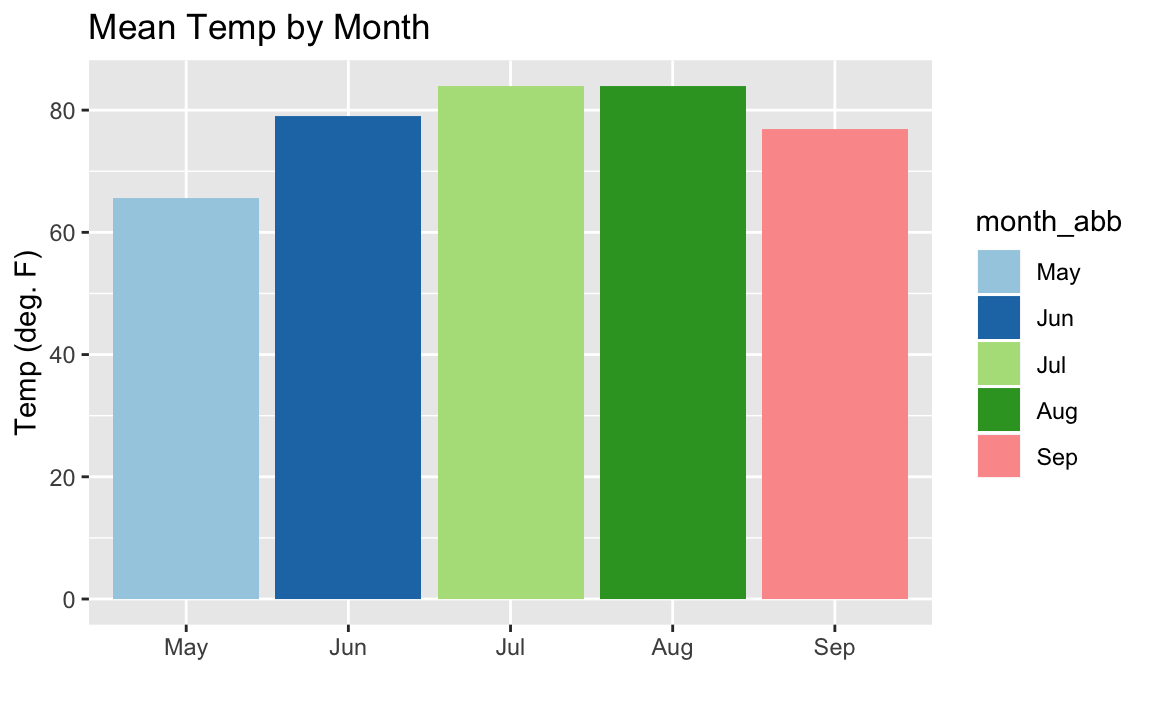

Below we pass the character name of each month to the fill parameter:

aq_data<-airquality%>%arrange(Month)%>%mutate(month_abb=fct_inorder(month.abb[Month]))ggplot(data=aq_data,aes(month_abb,Temp,fill=month_abb))+geom_bar(stat="summary",fun.y="mean")+labs(title="Mean Temp by Month",x="",y="Temp (deg. F)")+scale_fill_brewer(palette="Paired")

Figure 10-19. Colored Monthly Temp Bar Chart

The colors in the resulting Figure 10-19 are defined by

calling scale_fill_brewer(palette="Paired"). The "Paired" color

palette comes, along with many other color pallets, in the package

RColorBrewer.

If we wanted to change the color of each bar based on the temperature,

we can’t just set fill=Temp as might seem intuitive because ggplot

would not understand we want the mean temperature after the grouping by

month. So the way we get around this is to access a special field inside

of our graph called ..y.. which is the calculated value on the Y axis.

But we don’t want the legend labeled ..y.. so we add fill="Temp" to

our labs call in order to change the name of the legend. The result is

???

ggplot(airquality,aes(month.abb[Month],Temp,fill=..y..))+geom_bar(stat="summary",fun.y="mean")+labs(title="Mean Temp by Month",x="",y="Temp (deg. F)",fill="Temp")

images::images/10_Graphics_files/figure-latex/barsshaded-1.png[]

If we want to reverse the color scale, we can just add a negative - in

front of the field we are filling by. Like fill= -..y.., for example.

See Also

See “Creating a Bar Chart” for creating a bar chart.

Plotting a Line from x and y Points

Problem

You have paired observations in a data frame: (x1, y1), (x2, y2), …, (xn, yn). You want to plot a series of line segments that connect the data points.

Solution

With ggplot we can use geom_point to plot the points:.

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()

Since ggplot graphics are built up, element by element, we can have

both a point and a line in the same graphic very easily by having two

geoms:

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_point()+geom_line()

Discussion

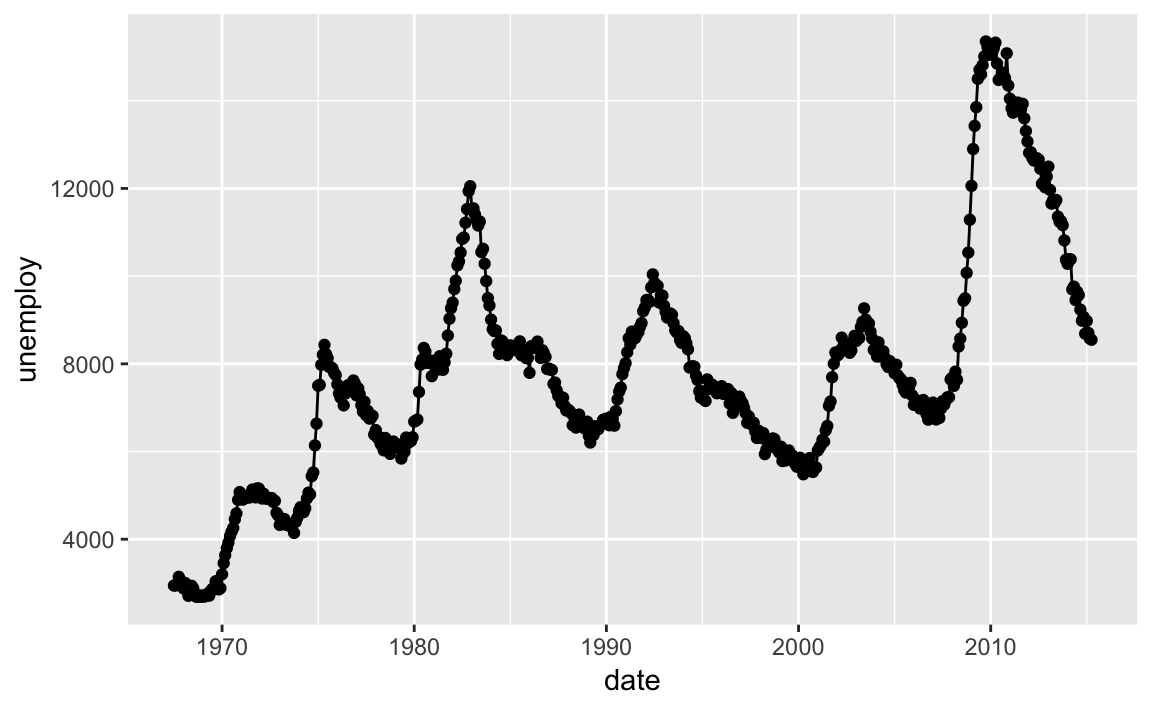

To illustrate, let’s look at some example US economic data that comes

with ggplot2. This example data frame has a column called date which

we’ll plot on the x axis and a field unemploy which is the number of

unemployed people.

ggplot(economics,aes(date,unemploy))+geom_point()+geom_line()

Figure 10-20. Line Chart Example

Figure 10-20 shows the resulting chart which contains both lines and points because we used both geoms.

See Also

Changing the Type, Width, or Color of a Line

Problem

You are plotting a line. You want to change the type, width, or color of the line.

Solution

ggplot uses the linetype parameter for controlling the appearance of

lines:

-

linetype="solid"orlinetype=1(default) -

linetype="dashed"orlinetype=2 -

linetype="dotted"orlinetype=3 -

linetype="dotdash"orlinetype=4 -

linetype="longdash"orlinetype=5 -

linetype="twodash"orlinetype=6 -

linetype="blank"orlinetype=0(inhibits drawing)

You can change the line characteristics by passing linetype, col

and/or size as parameters to the geom_line. So if we want to change

the linetype to dashed, red, and heavy we could pass the linetype,

col and size params to geom_line:

ggplot(df,aes(x,y))+geom_line(linetype=2,size=2,col="red")

Discussion

The example syntax above shows how to draw one line and specify its style, width, or color. A common scenario involves drawing multiple lines, each with its own style, width, or color.

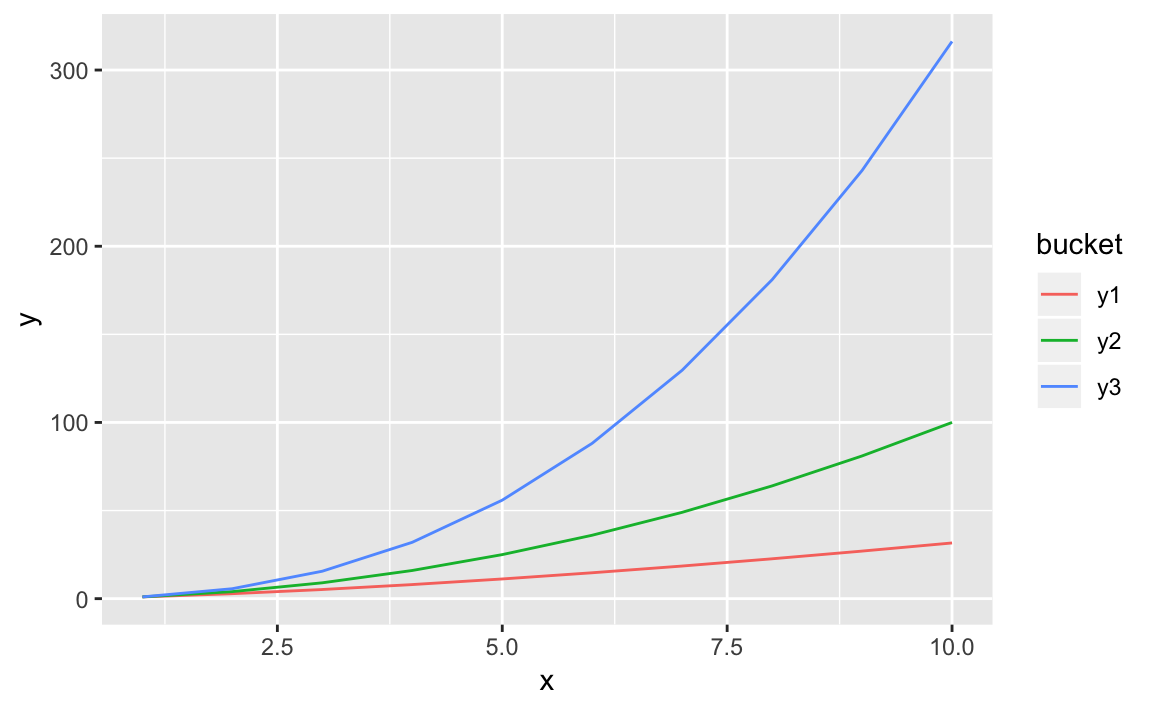

Let’s set up some example data:

x<-1:10y1<-x**1.5y2<-x**2y3<-x**2.5df<-data.frame(x,y1,y2,y3)

In ggplot this can be a conundrum for many users. The challenge is

that ggplot works best with “long” data instead of “wide” data as was

mentioned in the introduction to this chapter. Our example data frame

has 4 columns of wide data:

head(df,3)#> x y1 y2 y3#> 1 1 1.00 1 1.00#> 2 2 2.83 4 5.66#> 3 3 5.20 9 15.59

We can make our wide data long by using the gather function from the

core tidyverse pacakge tidyr. In the example below, we use gather to

create a new column named bucket and put our column names in there

while keeping our x and y variables.

df_long<-gather(df,bucket,y,-x)head(df_long,3)#> x bucket y#> 1 1 y1 1.00#> 2 2 y1 2.83#> 3 3 y1 5.20tail(df_long,3)#> x bucket y#> 28 8 y3 181#> 29 9 y3 243#> 30 10 y3 316

Now we can pass bucket to the col parameter and get multiple lines,

each a different color:

ggplot(df_long,aes(x,y,col=bucket))+geom_line()

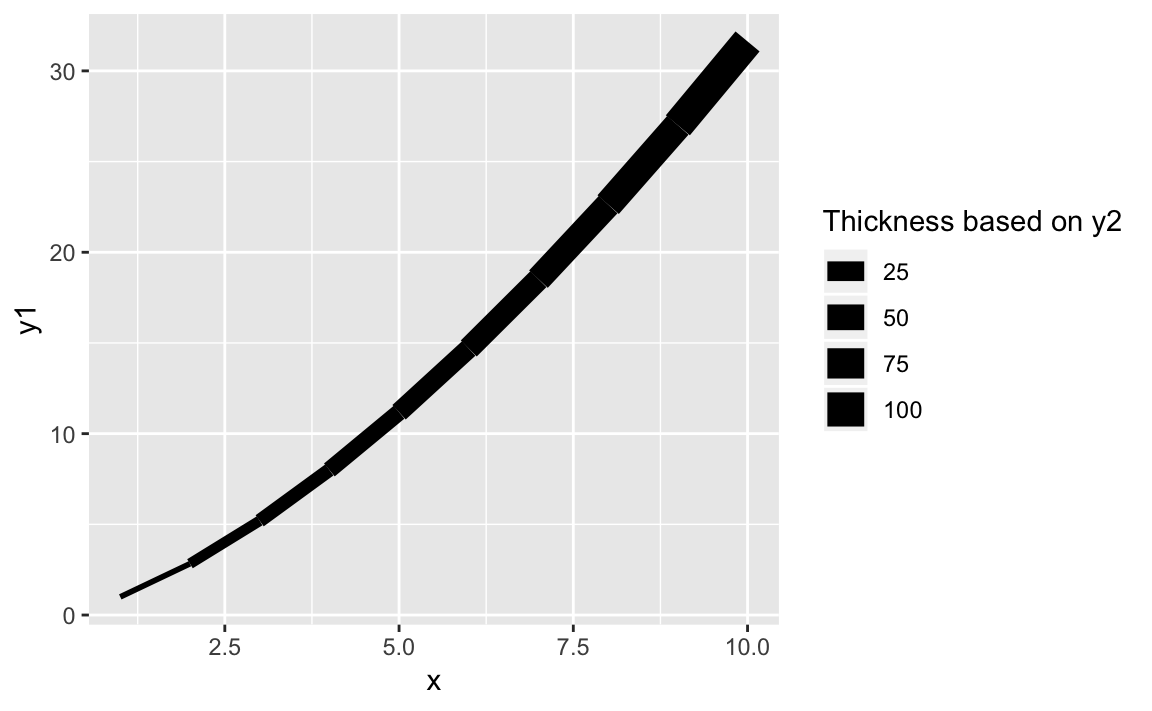

It’s straight forward to vary the line weight by a variable by passing a

numerical variable to size:

ggplot(df,aes(x,y1,size=y2))+geom_line()+scale_size(name="Thickness based on y2")

Figure 10-21. Thickness as a Function of x

The result of varying the thickness with x is shown in Figure 10-21.

See Also

See “Plotting a Line from x and y Points” for plotting a basic line.

Plotting Multiple Datasets

Problem

You want to show multiple datasets in one plot.

Solution

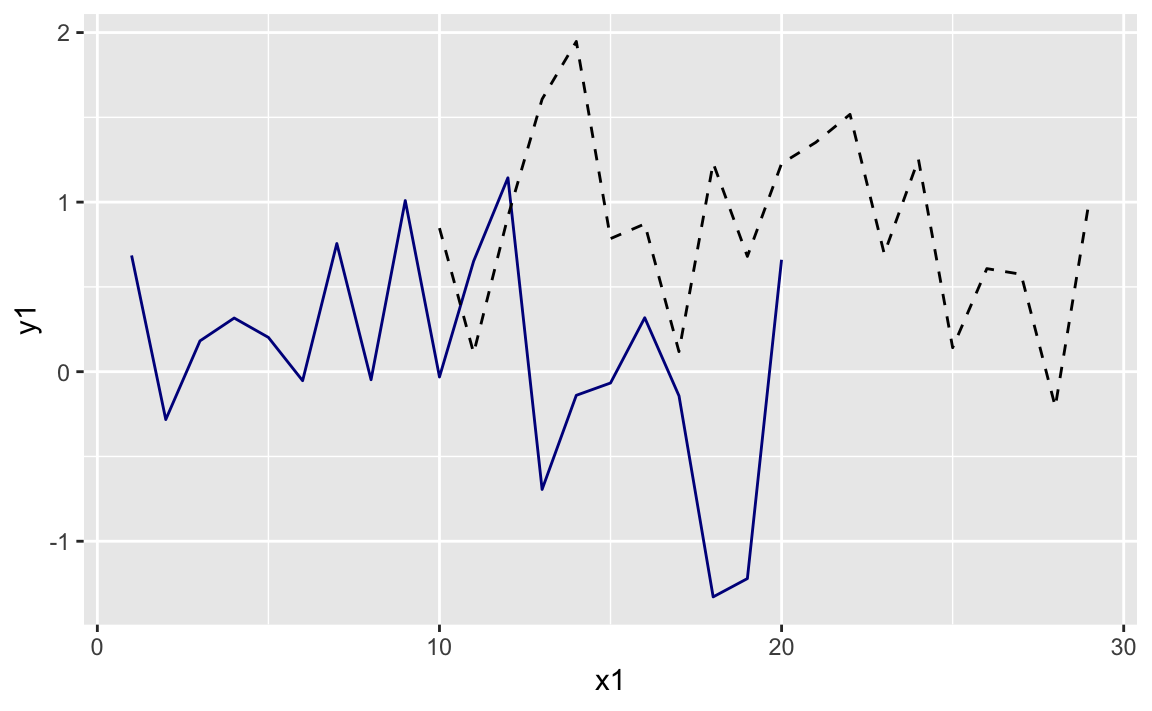

We could combine the data into one data frame before plotting using one

of the join functions from dplyr. However below we will create two

seperate data frames then add them each to a ggplot graph.

First let’s set up our example data frames, df1 and df2:

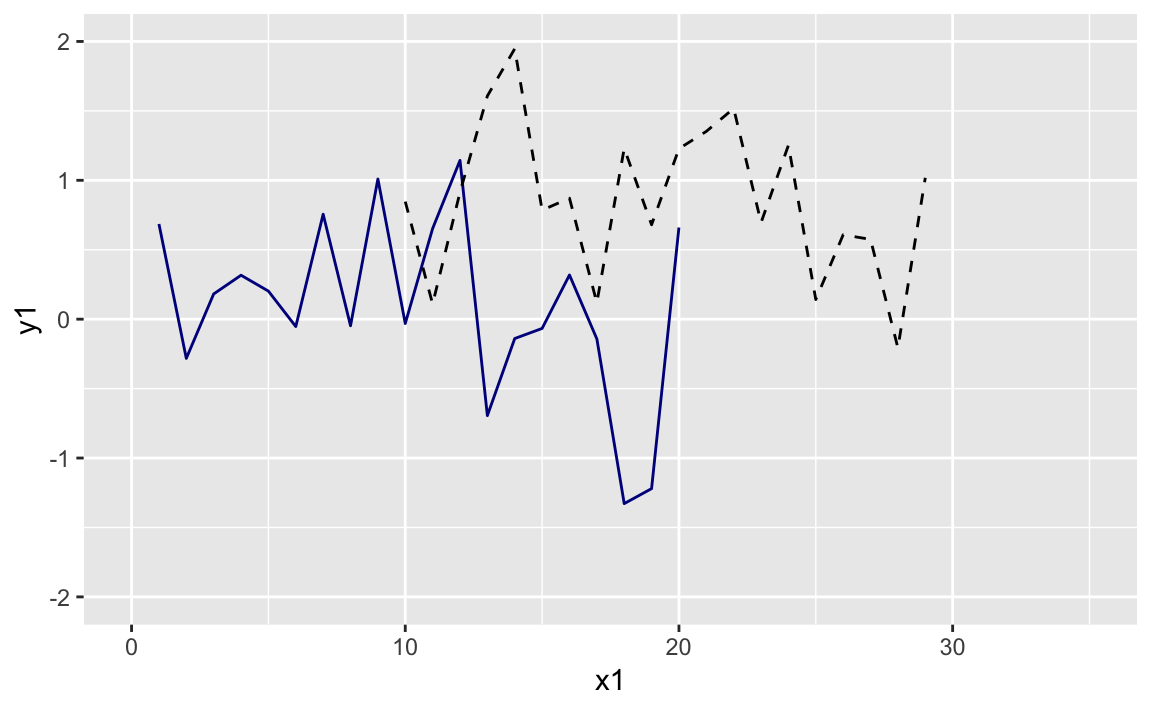

# example datan<-20x1<-1:ny1<-rnorm(n,0,.5)df1<-data.frame(x1,y1)x2<-(.5*n):((1.5*n)-1)y2<-rnorm(n,1,.5)df2<-data.frame(x2,y2)

Typically we would pass the data frame directly into the ggplot

function call. Since we want two geoms with two different data sources,

we will initiate a plot with ggplot() and then add in two calls to

geom_line each with its own data source.

ggplot()+geom_line(data=df1,aes(x=x1,y=y1),color="darkblue")+geom_line(data=df2,aes(x=x2,y=y2),linetype="dashed")

Figure 10-22. Two Lines One Plot

Discussion

ggplot allows us to make multiple calls to different geom_ functions

each with its own data source, if desired. Then ggplot will look at

all the data we are plotting and adjust the ranges to accomodate all the

data.

Even with good defaults, sometimes we want our plot range to show a

different range. We can do that by setting the xlim and ylim in our

ggplot.

ggplot()+geom_line(data=df1,aes(x=x1,y=y1),color="darkblue")+geom_line(data=df2,aes(x=x2,y=y2),linetype="dashed")+xlim(0,35)+ylim(-2,2)

Figure 10-23. Two Lines Larger Limits

The graph with expanded limits is in Figure 10-23.

Adding Vertical or Horizontal Lines

Problem

You want to add a vertical or horizontal line to your plot, such as an axis through the origin or pointing out a threshold.

Solution

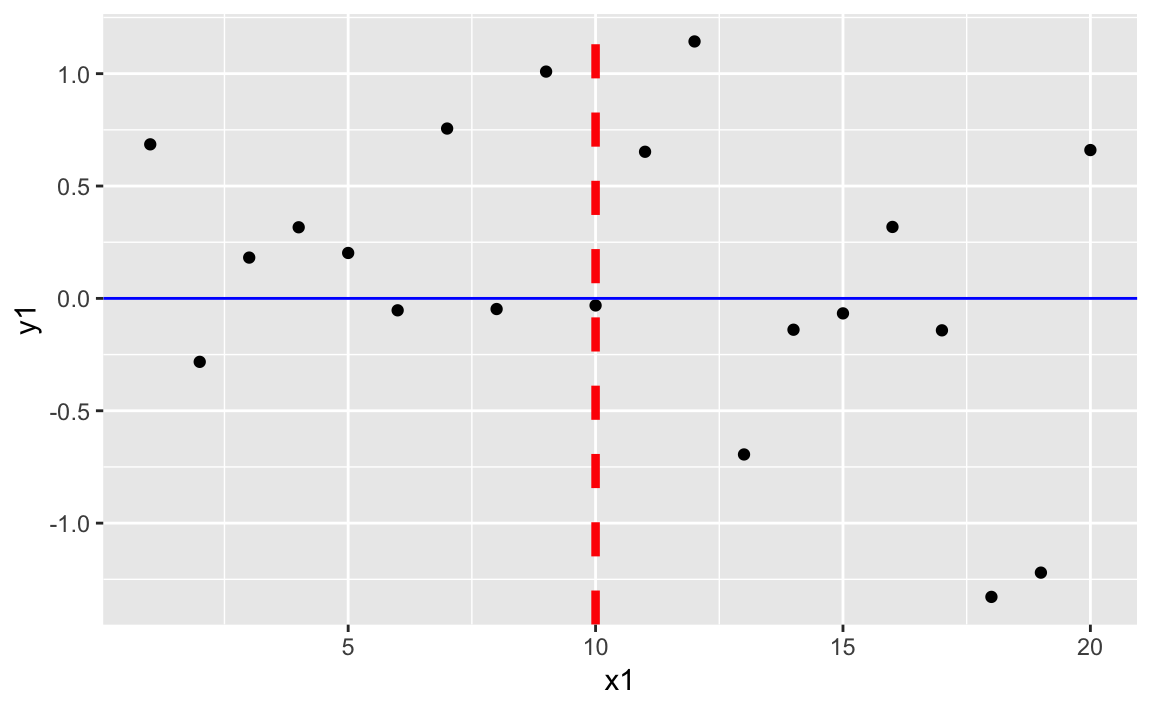

The ggplot functions geom_vline and geom_hline allow vertical and

horizontal lines, respectivly. The functions can also take color,

linetype, and size parameters to set the line style:

# using the data.frame df1 from the prior recipeggplot(df1)+aes(x=x1,y=y1)+geom_point()+geom_vline(xintercept=10,color="red",linetype="dashed",size=1.5)+geom_hline(yintercept=0,color="blue")

Figure 10-24. Vertical and Horizontal Lines

Figure 10-24 shows the resulting plot with added horizontal and vertical lines.

Discussion

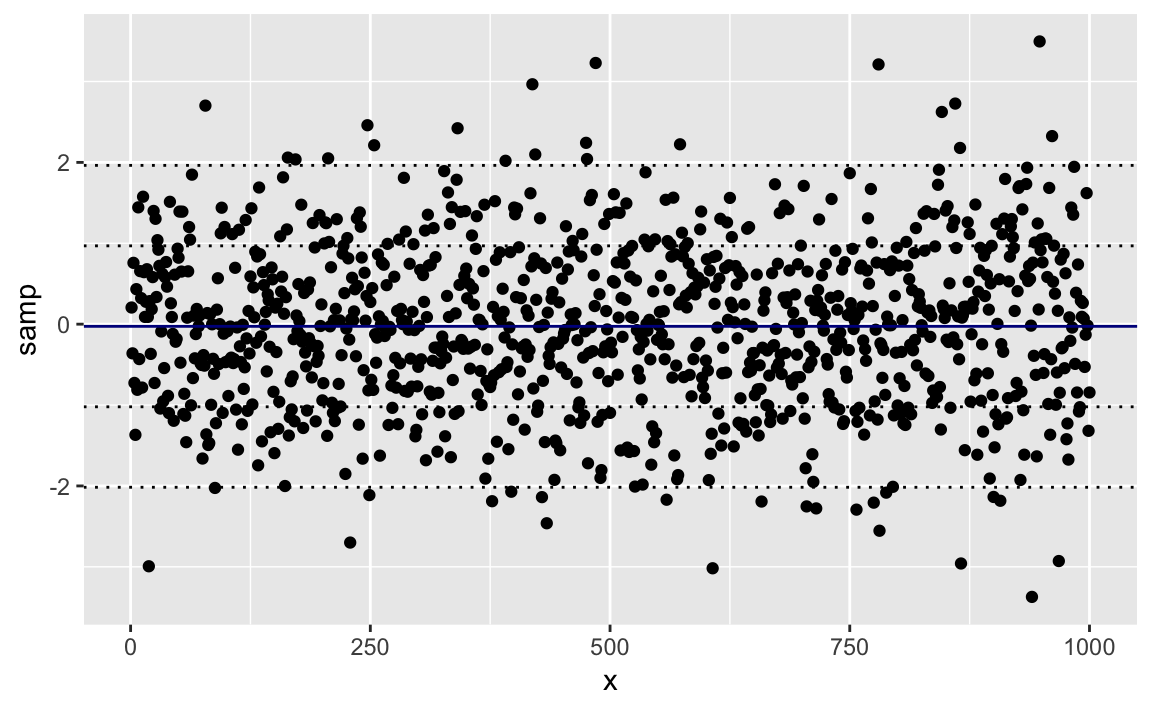

A typical use of lines would be drawing regularly spaced lines. Suppose

we have a sample of points, samp. First, we plot them with a solid

line through the mean. Then we calculate and draw dotted lines at ±1 and

±2 standard deviations away from the mean. We can add the lines into our

plot with geom_hline:

samp<-rnorm(1000)samp_df<-data.frame(samp,x=1:length(samp))mean_line<-mean(samp_df$samp)sd_lines<-mean_line+c(-2,-1,+1,+2)*sd(samp_df$samp)ggplot(samp_df)+aes(x=x,y=samp)+geom_point()+geom_hline(yintercept=mean_line,color="darkblue")+geom_hline(yintercept=sd_lines,linetype="dotted")

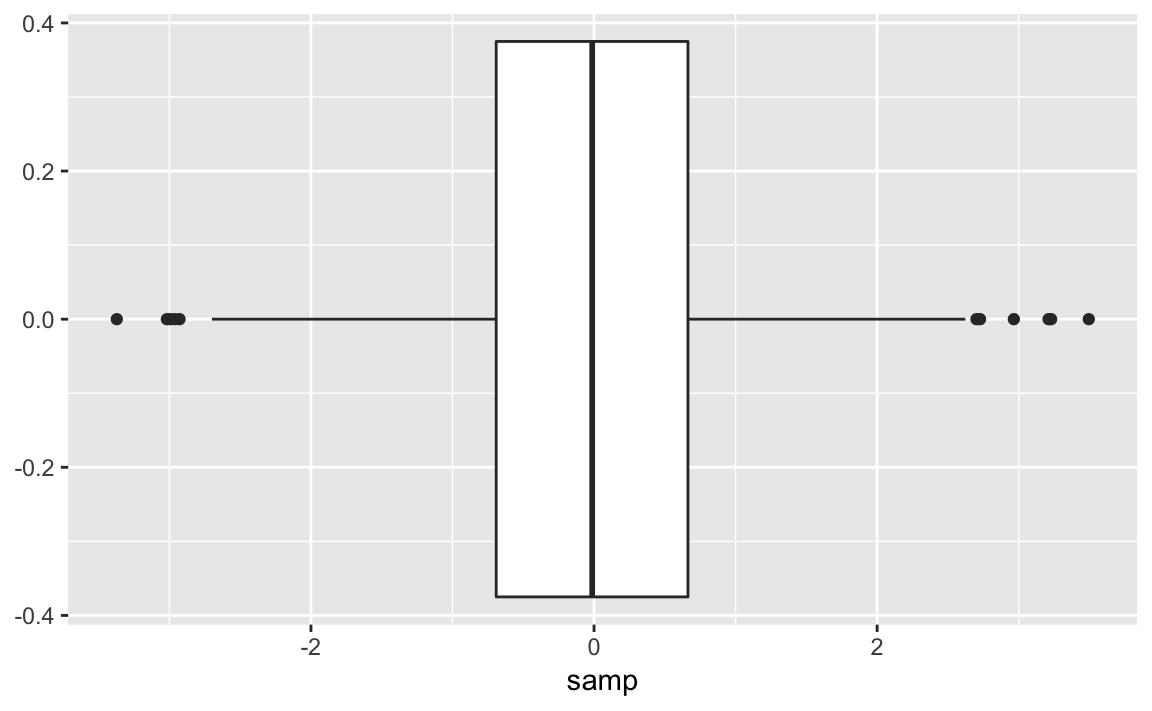

Figure 10-25. Mean and SD Bands in a Plot

Figure 10-25 shows the sampled data along with the mean and standard deviation lines.

See Also

See “Changing the Type, Width, or Color of a Line” for more about changing line types.

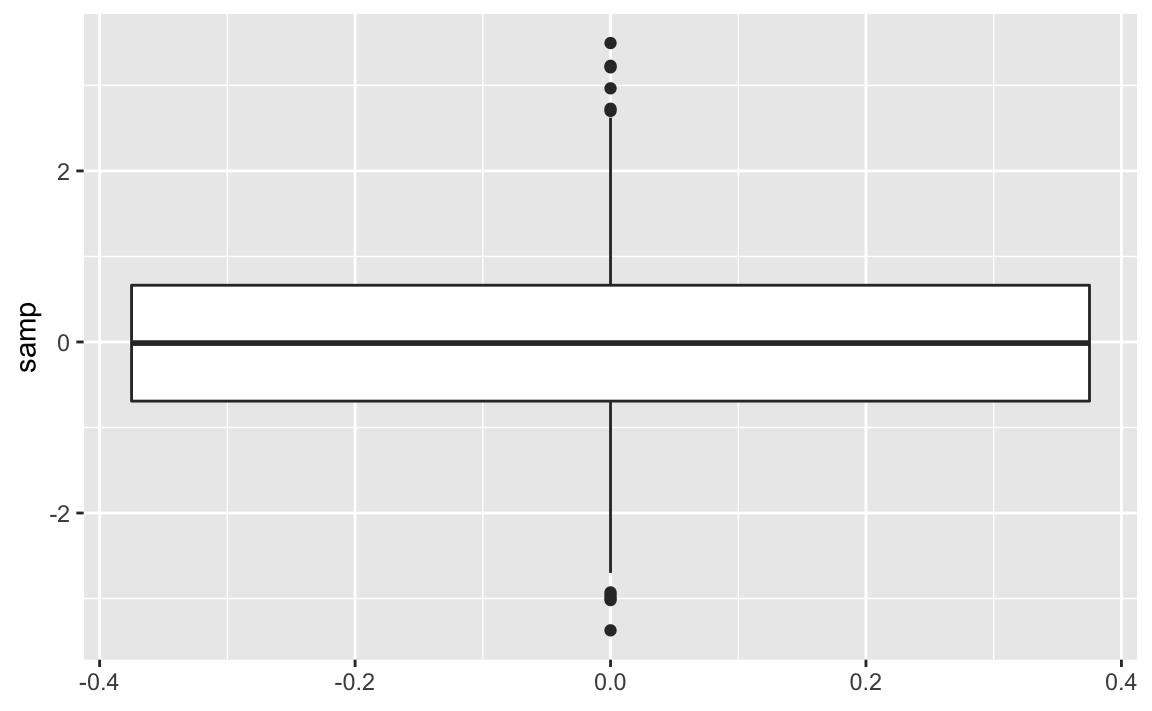

Creating a Box Plot

Problem

You want to create a box plot of your data.

Solution

Use geom_boxplot from ggplot to add a boxplot geom to a ggplot

graphic. Using the samp_df data frame from the prior recipe, we can

create a box plot of the values in the x column. The resulting graph

is in Figure 10-26.

ggplot(samp_df)+aes(y=samp)+geom_boxplot()

Figure 10-26. Single Boxplot

Discussion

A box plot provides a quick and easy visual summary of a dataset.

-

The thick line in the middle is the median.

-

The box surrounding the median identifies the first and third quartiles; the bottom of the box is Q1, and the top is Q3.

-

The “whiskers” above and below the box show the range of the data, excluding outliers.

-

The circles identify outliers. By default, an outlier is defined as any value that is farther than 1.5 × IQR away from the box. (IQR is the interquartile range, or Q3 − Q1.) In this example, there are a few outliers on the high side.

We can rotate the boxplot by flipping the coordinates. There are some situations where this makes a more appealing graphic. This is shown in Figure 10-27.

ggplot(samp_df)+aes(y=samp)+geom_boxplot()+coord_flip()

Figure 10-27. Single Boxplot

See Also

One box plot alone is pretty boring. See “Creating One Box Plot for Each Factor Level” for creating multiple box plots.

Creating One Box Plot for Each Factor Level

Problem

Your dataset contains a numeric variable and a factor (or other catagorical text). You want to create several box plots of the numeric variable broken out by levels.

Solution

With ggplot we pass the name of the categorical variable to the x

parameter in the aes call. The resulting boxplot will then be grouped

by the values in the categorical variable:

ggplot(df)+aes(x=factor,y=values)+geom_boxplot()

Discussion

This recipe is another great way to explore and illustrate the relationship between two variables. In this case, we want to know whether the numeric variable changes according to the level of a category.

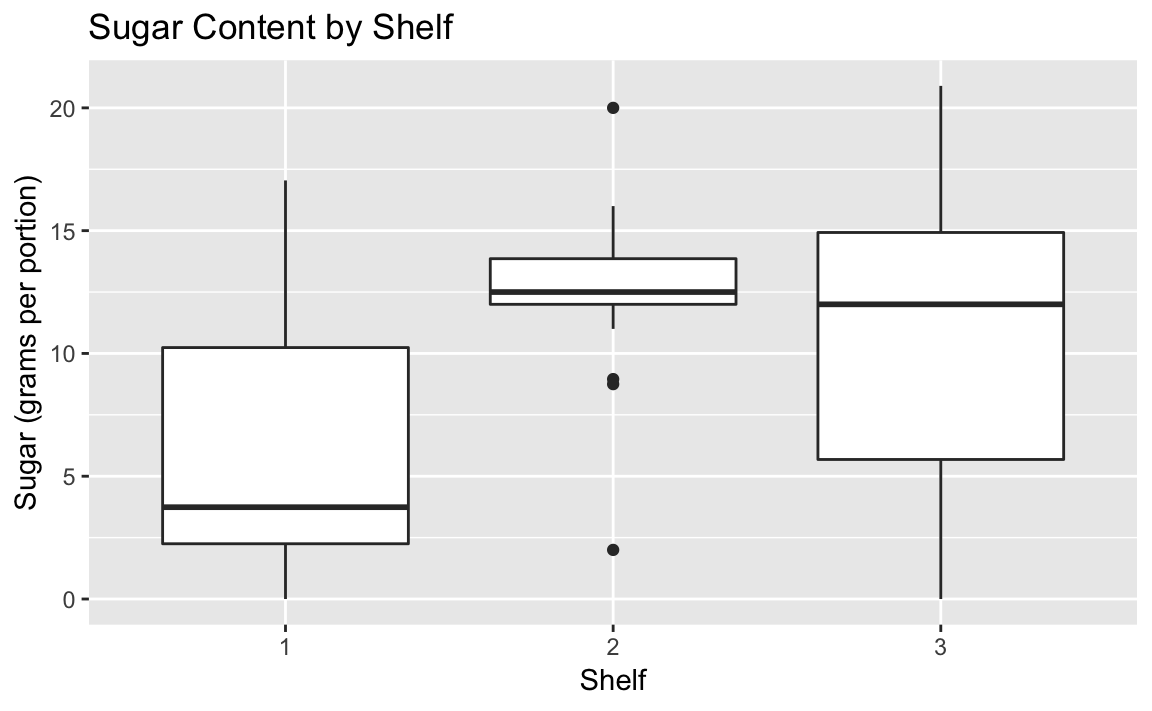

The UScereal dataset from the MASS package contains many variables

regarding breakfast cereals. One variable is the amount of sugar per

portion and another is the shelf position (counting from the floor).

Cereal manufacturers can negotiate for shelf position, placing their

product for the best sales potential. We wonder: Where do they put the

high-sugar cereals? We can produce Figure 10-28 and

explore that question by creating one box plot per shelf:

data(UScereal,package="MASS")ggplot(UScereal)+aes(x=as.factor(shelf),y=sugars)+geom_boxplot()+labs(title="Sugar Content by Shelf",x="Shelf",y="Sugar (grams per portion)")

Figure 10-28. Boxplot by Shelf Number

The box plots suggest that shelf #2 has the most high-sugar cereals. Could it be that this shelf is at eye level for young children who can influence their parent’s choice of cereals?

Note that in the aes call we had to tell ggplot to treat the shelf

number as a factor. Otherwise ggplot would not react to the shelf as a

grouping and only print a single boxplot.

See Also

See “Creating a Box Plot” for creating a basic box plot.

Creating a Histogram

Problem

You want to create a histogram of your data.

Solution

Use geom_histogram, and set x to a vector of numeric values.

Discussion

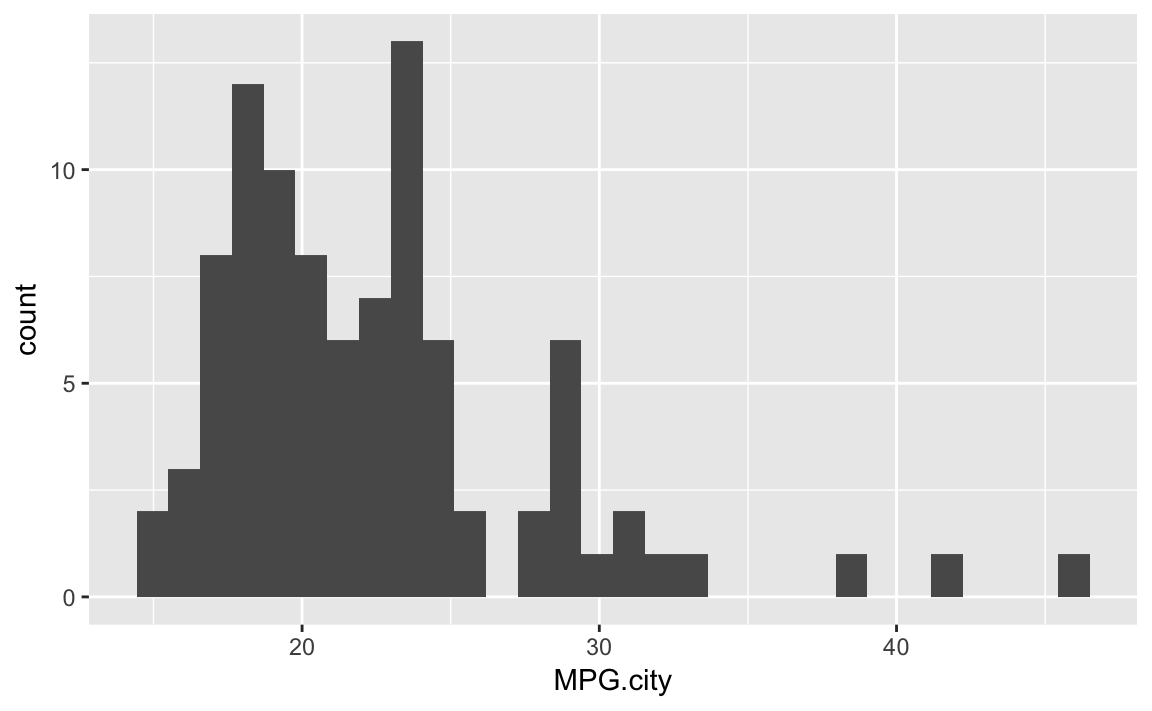

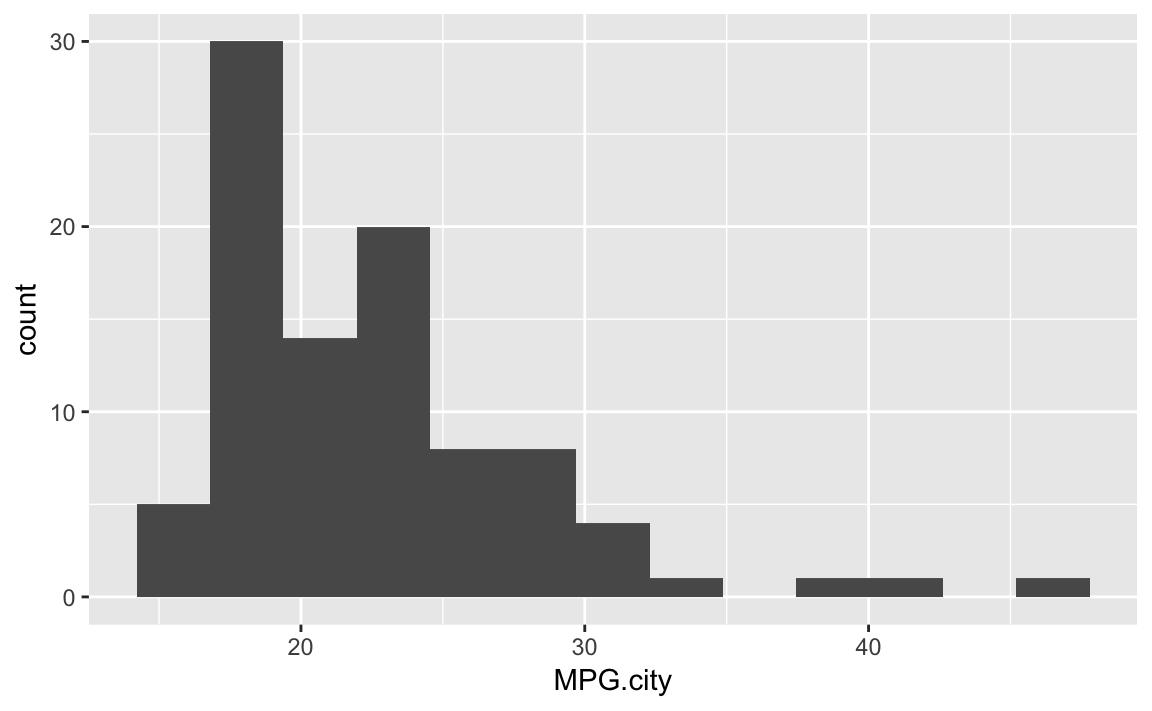

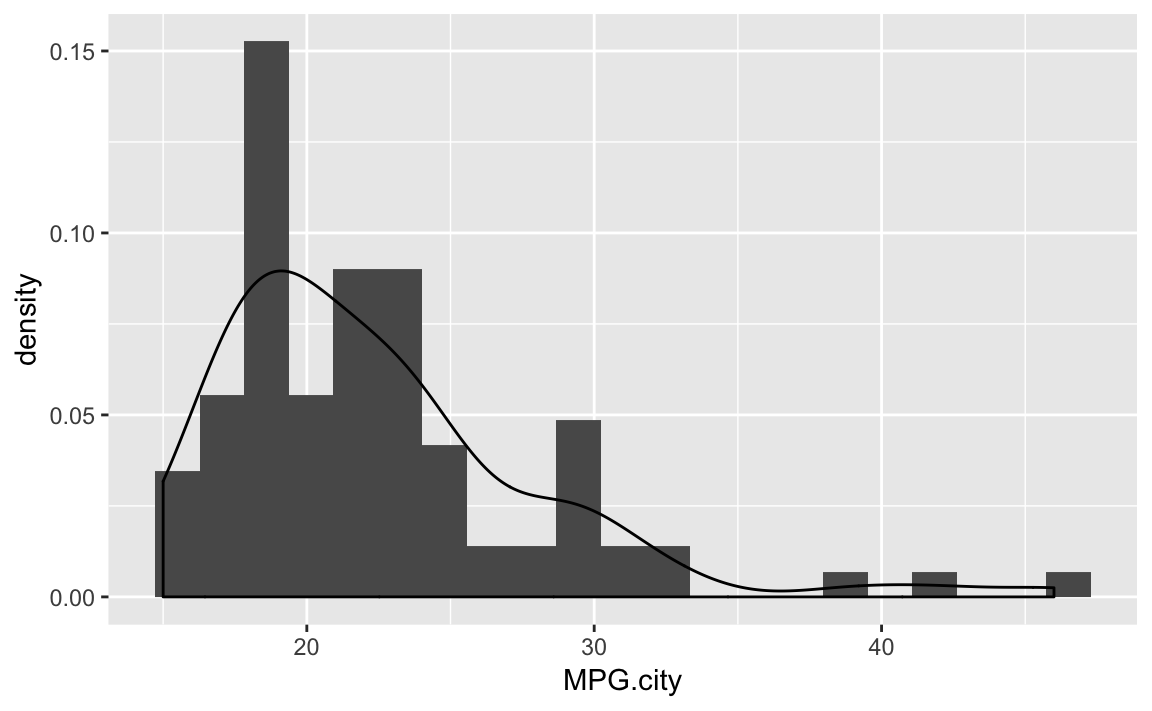

Figure 10-29 is a histogram of the MPG.city column taken

from the Cars93 dataset:

data(Cars93,package="MASS")ggplot(Cars93)+geom_histogram(aes(x=MPG.city))#> `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

Figure 10-29. Histogram of Counts by MPG

The geom_histogram function must decide how many cells (bins) to

create for binning the data. In this example, the default algorithm

chose 30 bins. If we wanted fewer bins, we wo would include the bins

parameter to tell geom_histogram how many bins we want:

ggplot(Cars93)+geom_histogram(aes(x=MPG.city),bins=13)

Figure 10-30. Histogram of Counts by MPG with Fewer Bins

Figure 10-30 shows the histogram with 13 bins.

See Also

The Base R function hist provides much of the same functionality as

does the histogram function of the lattice package.

Adding a Density Estimate to a Histogram

Problem

You have a histogram of your data sample, and you want to add a curve to illustrate the apparent density.

Solution

Use the geom_density function to approximate the sample density as

shown in Figure 10-31:

ggplot(Cars93)+aes(x=MPG.city)+geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..),bins=21)+geom_density()

Figure 10-31. Histogram with Density Plot

Discussion

A histogram suggests the density function of your data, but it is rough. A smoother estimate could help you better visualize the underlying distribution. A Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) is a smoother representation of univariate data.

In ggplot we tell the geom_histogram function to use the density

function by passing it aes(y = ..density..).

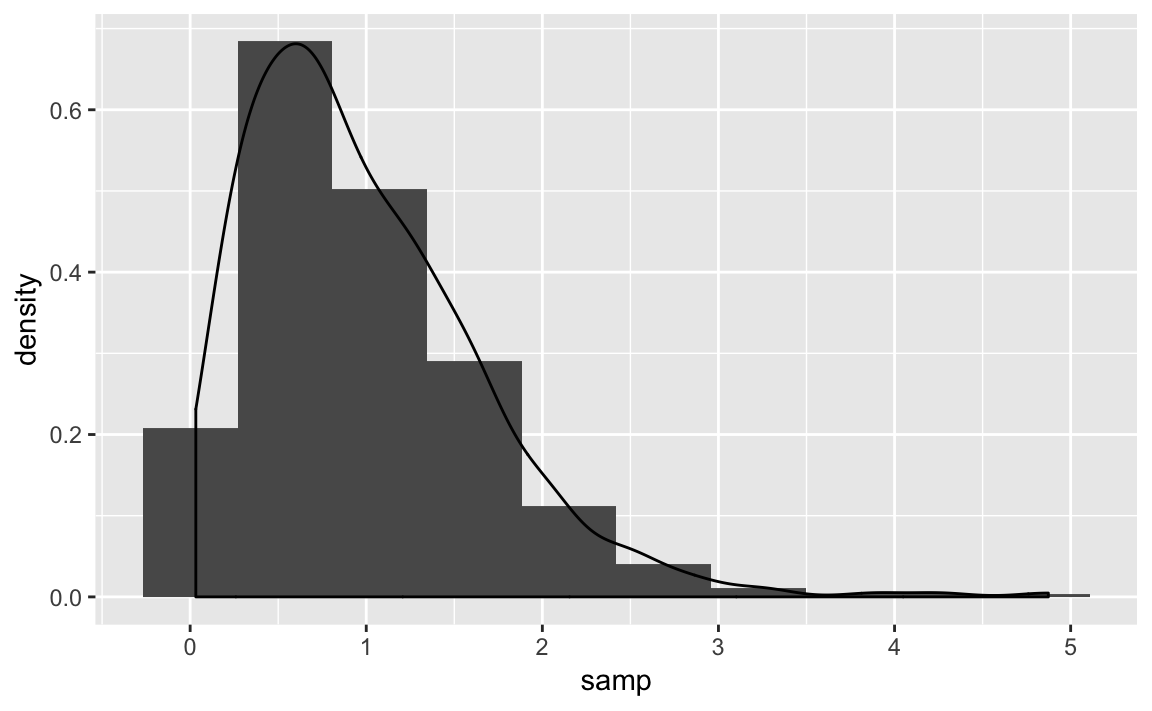

The following example takes a sample from a gamma distribution and then plots the histogram and the estimated density as shown in Figure 10-32.

samp<-rgamma(500,2,2)ggplot()+aes(x=samp)+geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..),bins=10)+geom_density()

Figure 10-32. Histogram and Density: Gamma Distribution

See Also

The density function approximates the shape of the density nonparametrically. If you know the actual underlying distribution, use instead “Plotting a Density Function” to plot the density function.

Creating a Normal Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) Plot

Problem

You want to create a quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot of your data, typically because you want to know how the data differs from a normal distribution.

Solution

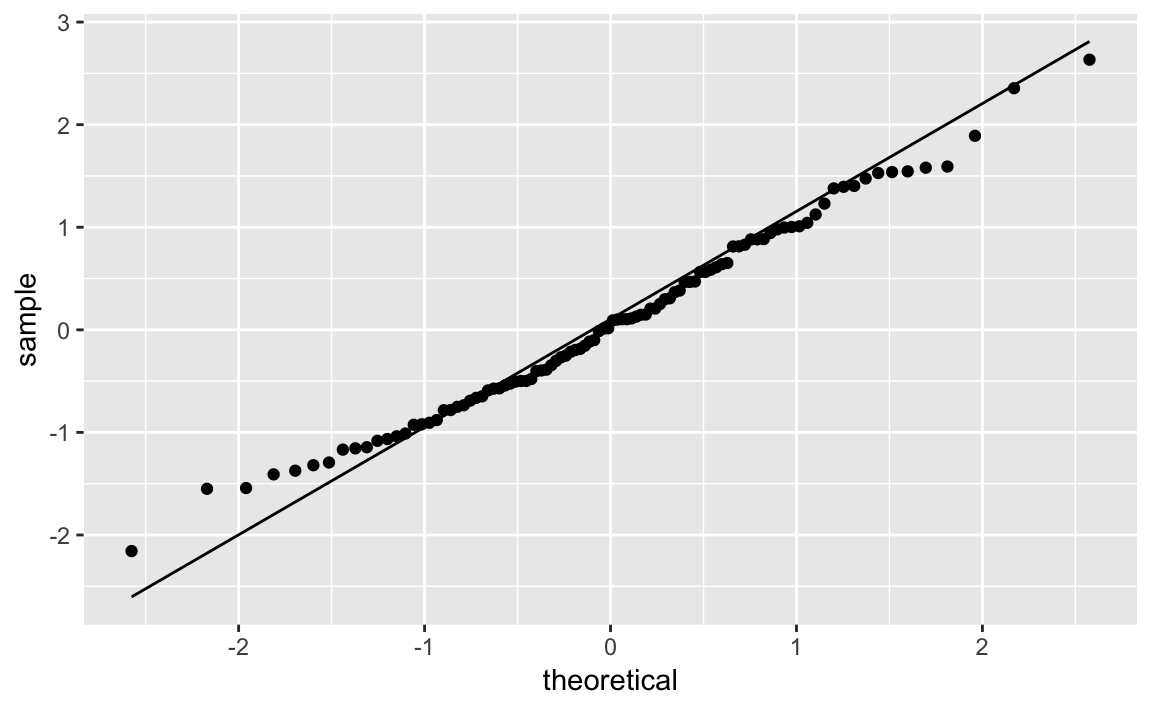

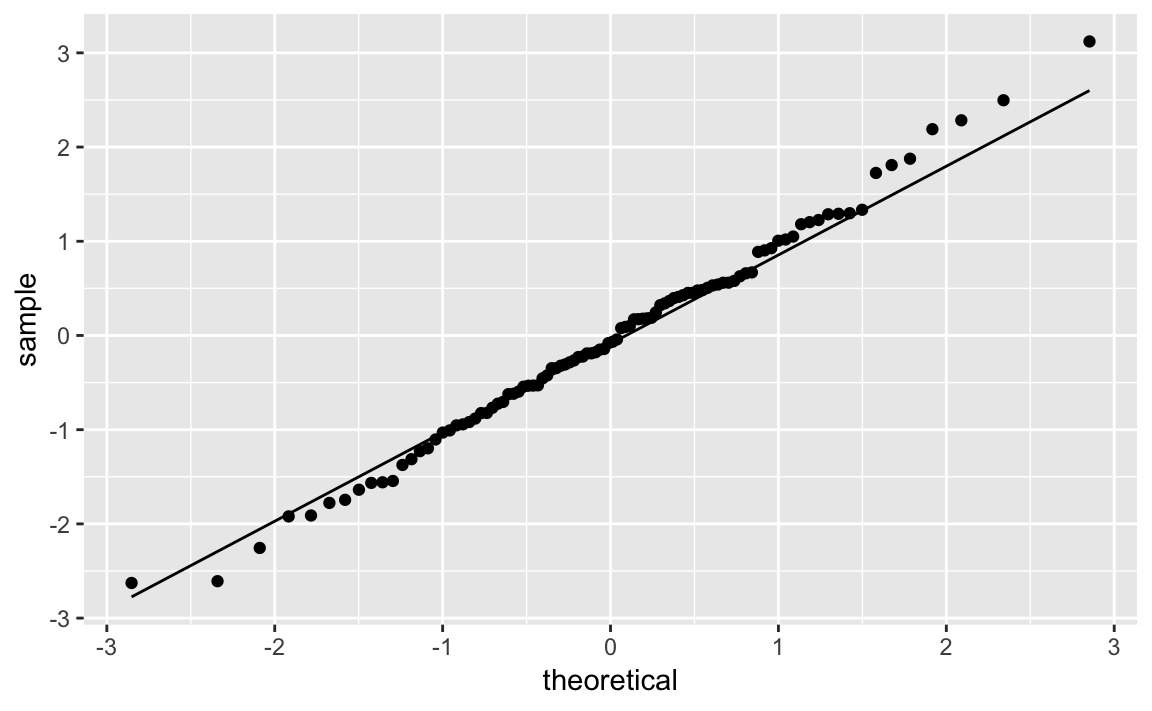

With ggplot we can use the stat_qq and stat_qq_line functions to

create a Q-Q plot that shows both the observed points as well as the Q-Q

Line. Figure 10-33 shows the resulting plot.

df<-data.frame(x=rnorm(100))ggplot(df,aes(sample=x))+stat_qq()+stat_qq_line()

Figure 10-33. Q-Q Plot

Discussion

Sometimes it’s important to know if your data is normally distributed. A quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot is a good first check.

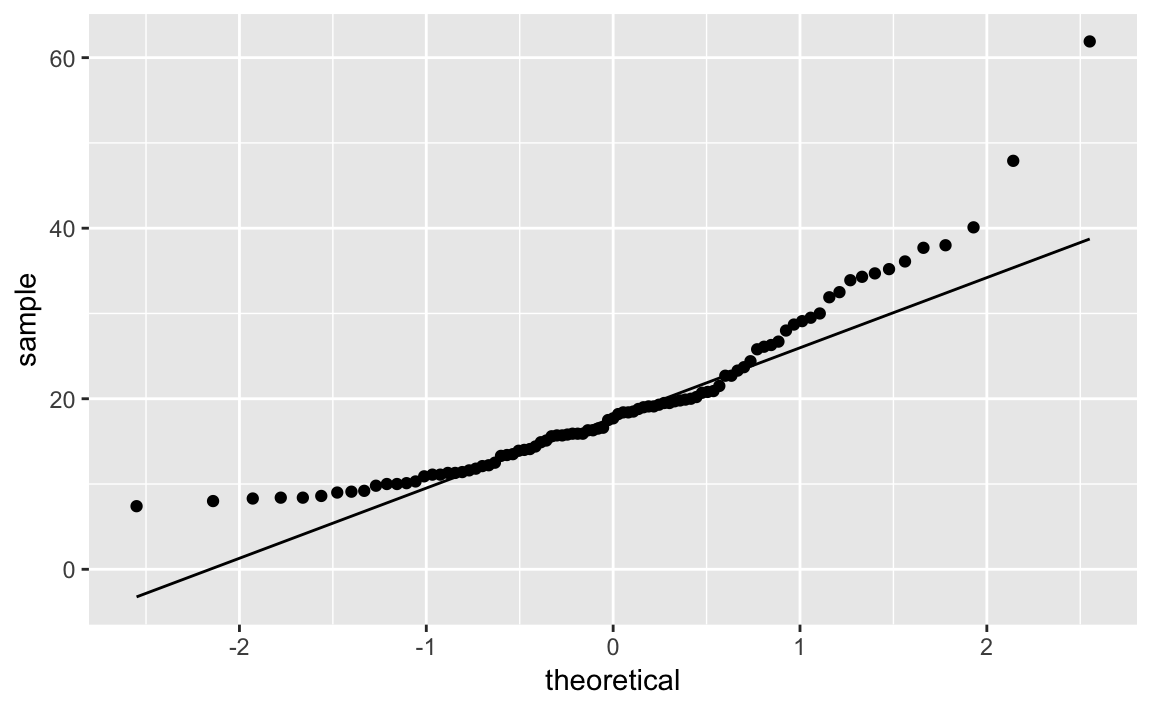

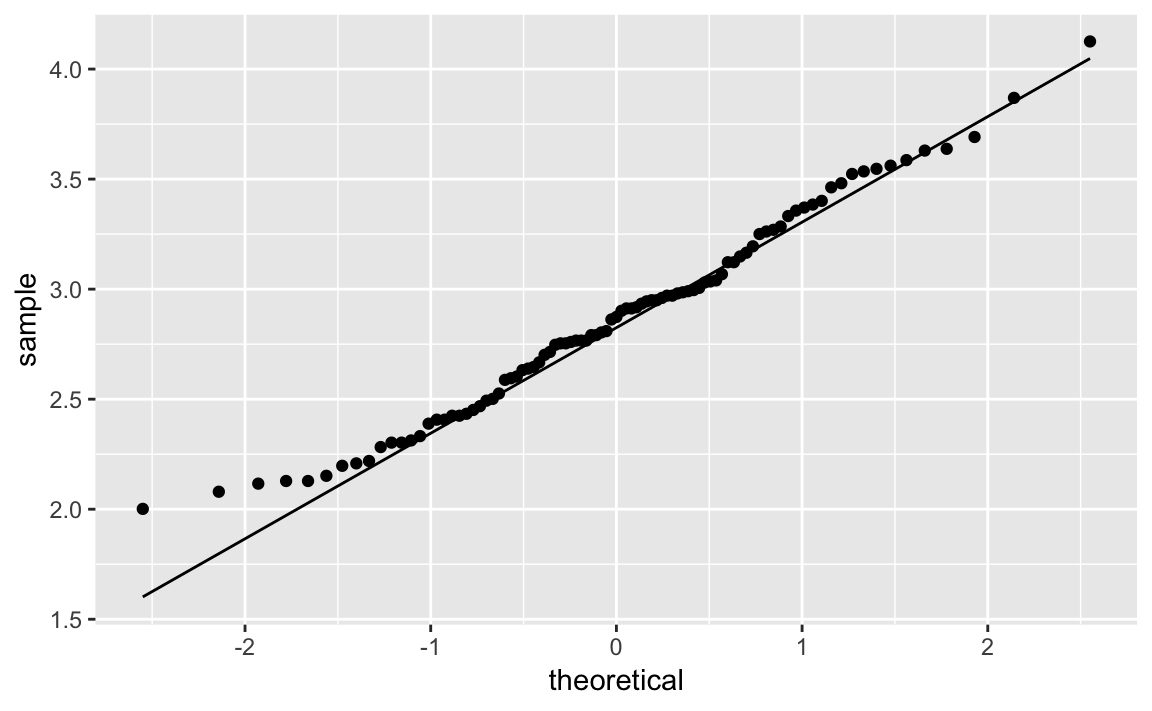

The Cars93 dataset contains a Price column. Is it normally

distributed? This code snippet creates a Q-Q plot of Price shown in

Figure 10-34:

ggplot(Cars93,aes(sample=Price))+stat_qq()+stat_qq_line()

Figure 10-34. Q-Q Plot of Car Prices

If the data had a perfect normal distribution, then the points would fall exactly on the diagonal line. Many points are close, especially in the middle section, but the points in the tails are pretty far off. Too many points are above the line, indicating a general skew to the left.

The leftward skew might be cured by a logarithmic transformation. We can plot log(Price), which yields Figure 10-35:

ggplot(Cars93,aes(sample=log(Price)))+stat_qq()+stat_qq_line()

Figure 10-35. Q-Q Plot of Log Car Prices

Notice that the points in the new plot are much better behaved, staying close to the line except in the extreme left tail. It appears that log(Price) is approximately Normal.

See Also

See “Creating Other Quantile-Quantile Plots” for creating Q-Q plots for other distributions. See Recipe X-X for an application of Normal Q-Q plots to diagnosing linear regression.

Creating Other Quantile-Quantile Plots

Problem

You want to view a quantile-quantile plot for your data, but the data is not normally distributed.

Solution

For this recipe, you must have some idea of the underlying distribution, of course. The solution is built from the following steps:

-

Use the

ppointsfunction to generate a sequence of points between 0 and 1. -

Transform those points into quantiles, using the quantile function for the assumed distribution.

-

Sort your sample data.

-

Plot the sorted data against the computed quantiles.

-

Use

ablineto plot the diagonal line.

This can all be done in two lines of R code. Here is an example that

assumes your data, y, has a Student’s t distribution with 5 degrees

of freedom. Recall that the quantile function for Student’s t is qt

and that its second argument is the degrees of freedom. To create draws

from

First let’s make some example data:

df_t<-data.frame(y=rt(100,5))

In order to plot the Q-Q plot we need to estimate the parameters of the

distribution we’re wanting to plot. Since this is a Student’s t

distribution, we only need to estimate one parameter, the degrees of

freedom. Of course we know the actual degrees of freedom is 5, but in

most situations we’ll need to calcuate value. So we’ll use the

MASS::fitdistr function to estimate the degrees of freedom:

est_df<-as.list(MASS::fitdistr(df_t$y,"t")$estimate)[["df"]]#> Warning in log(s): NaNs produced#> Warning in log(s): NaNs produced#> Warning in log(s): NaNs producedest_df#> [1] 19.5

As expected, that’s pretty close to what was used to generate the simulated data. So let’s pass the estimaged degrees of freedom to the Q-Q functions and create Figure 10-36:

ggplot(df_t)+aes(sample=y)+geom_qq(distribution=qt,dparams=est_df)+stat_qq_line(distribution=qt,dparams=est_df)

Figure 10-36. Student’s t Distribution Q-Q Plot

Discussion

The solution looks complicated, but the gist of it is picking a

distribution, fitting the parameters, and then passing those parameters

to the Q-Q functions in ggplot.

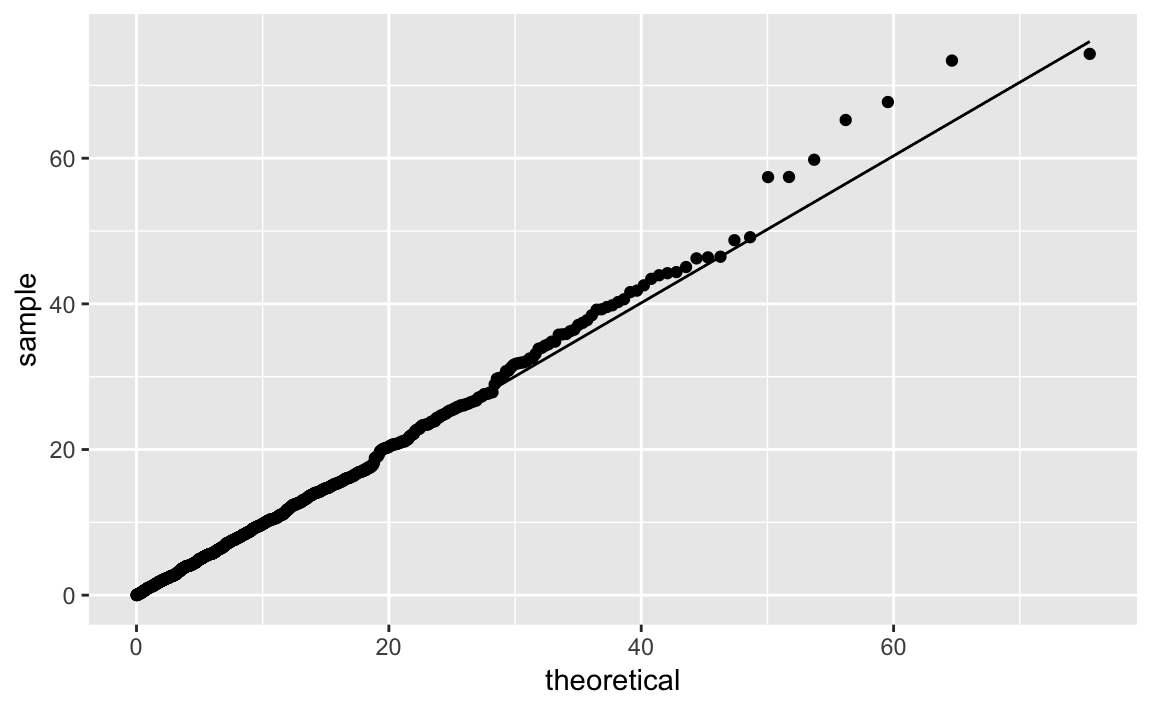

We can illustrate this recipe by taking a random sample from an exponential distribution with a mean of 10 (or, equivalently, a rate of 1/10):

rate<-1/10n<-1000df_exp<-data.frame(y=rexp(n,rate=rate))

est_exp<-as.list(MASS::fitdistr(df_exp$y,"exponential")$estimate)[["rate"]]est_exp#> [1] 0.101

Notice that for an exponential distribution the parameter we estimate is

called rate as opposed to df which was the parameter in the t

distribution.

ggplot(df_exp)+aes(sample=y)+geom_qq(distribution=qexp,dparams=est_exp)+stat_qq_line(distribution=qexp,dparams=est_exp)

Figure 10-37. Exponential Distribution Q-Q Plot

The quantile function for the exponential distribution is qexp, which

takes the rate argument. Figure 10-37 shows the resulting

Q-Q plot using a theoretical exponential distribution.

Plotting a Variable in Multiple Colors

Problem

You want to plot your data in multiple colors, typically to make the plot more informative, readable, or interesting.

Solution

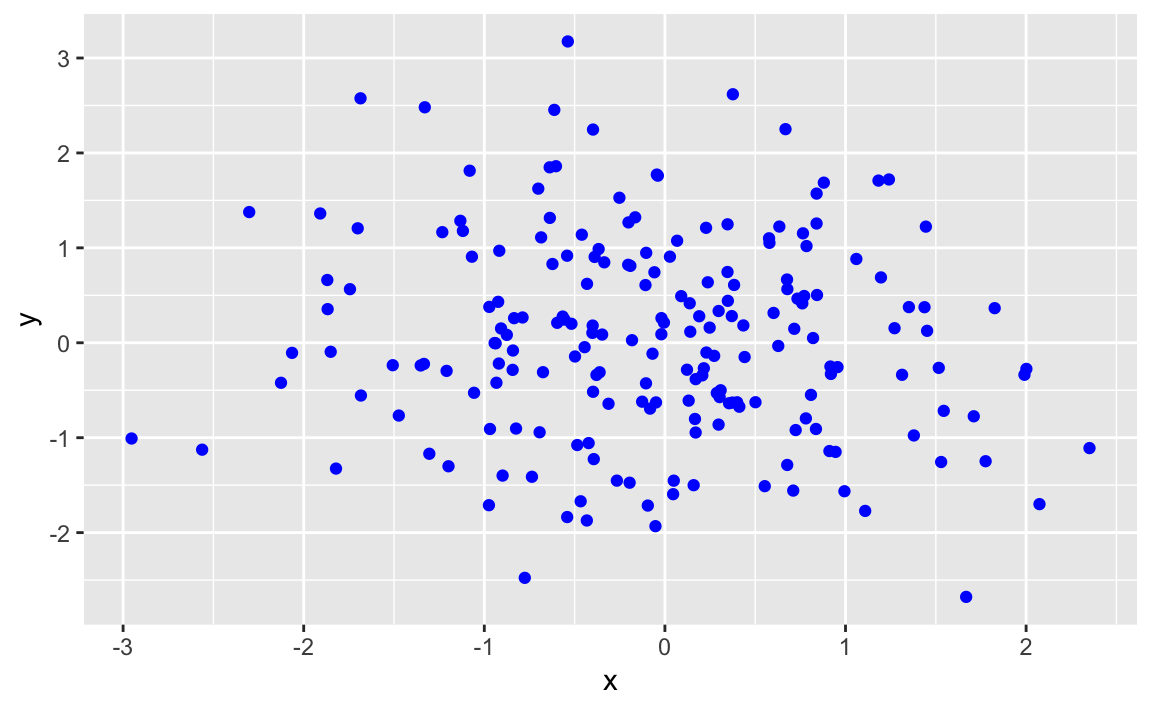

We can pass a color to a geom_ function in order to produced colored

output:

df<-data.frame(x=rnorm(200),y=rnorm(200))ggplot(df)+aes(x=x,y=y)+geom_point(color="blue")

Figure 10-38. Point Data in Color

The value of color can be:

-

One color, in which case all data points are that color.

-

A vector of colors, the same length as

x, in which case each value ofxis colored with its corresponding color. -

A short vector, in which case the vector of colors is recycled.

Discussion

The default color in ggplot is black. While it’s not very exciting,

black is high contrast and easy for most anyone to see.

However, it is much more useful (and interesting) to vary the color in a way that illuminates the data. Let’s illustrate this by plotting a graphic two ways, once in black and white and once with simple shading.

This produces the basic black-and-white graphic in Figure 10-39:

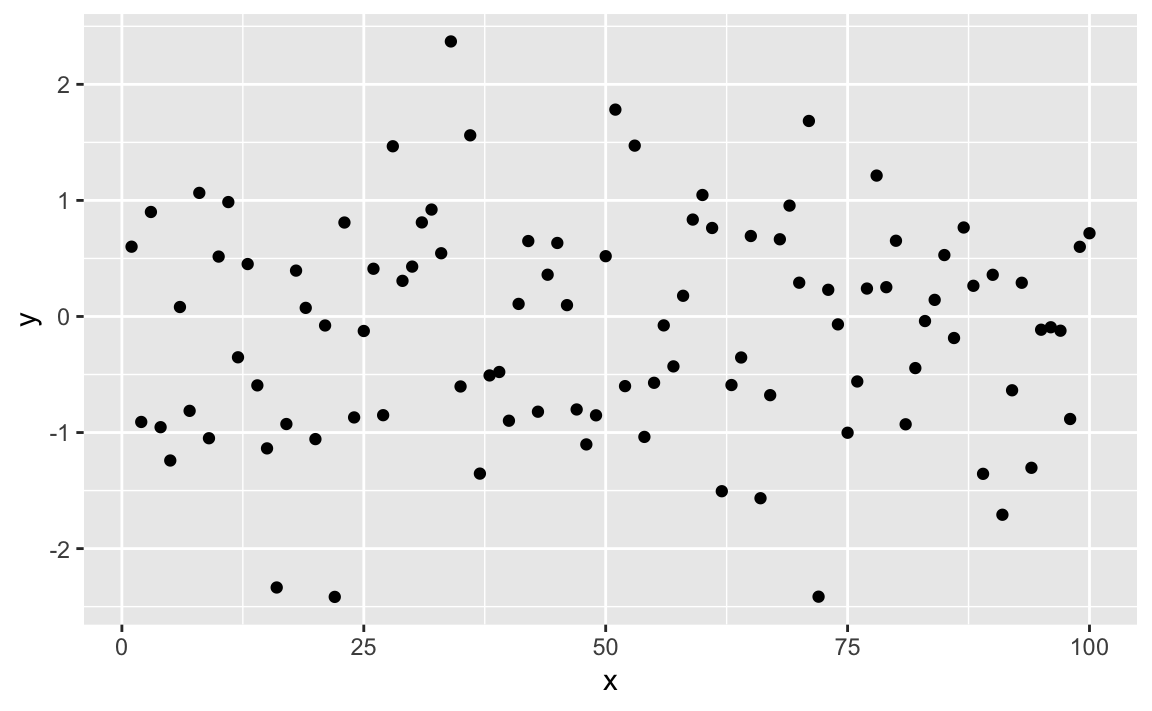

df<-data.frame(x=1:100,y=rnorm(100))ggplot(df)+aes(x,y)+geom_point()

Figure 10-39. Simple Point Plot

Now we can make it more interesting by creating a vector of "gray" and

"black" values, according to the sign of x and then plotting x

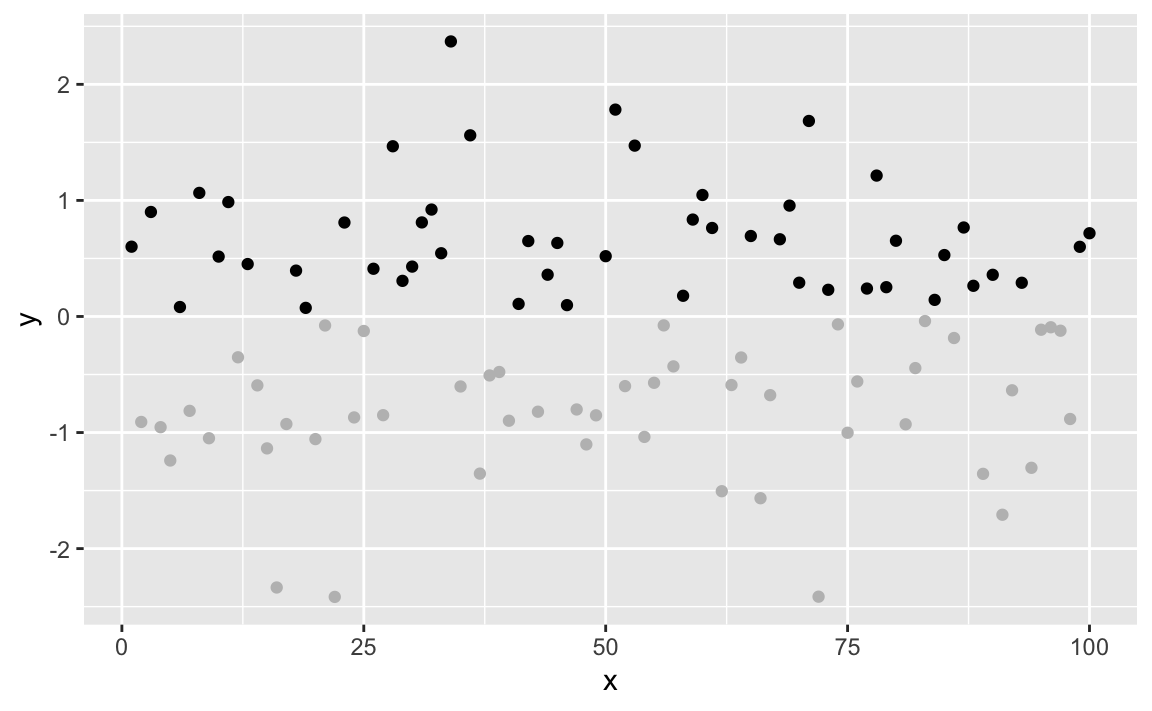

using those colors as shown in Figure 10-40:

shade<-if_else(df$y>=0,"black","gray")ggplot(df)+aes(x,y)+geom_point(color=shade)

Figure 10-40. Color Shaded Point Plot

The negative values are now plotted in gray because the corresponding

element of colors is "gray".

See Also

See “Understanding the Recycling Rule” regarding the Recycling Rule. Execute colors() to see

a list of available colors, and use geom_segment in ggplot to plot

line segments in multiple colors.

Graphing a Function

Problem

You want to graph the value of a function.

Solution

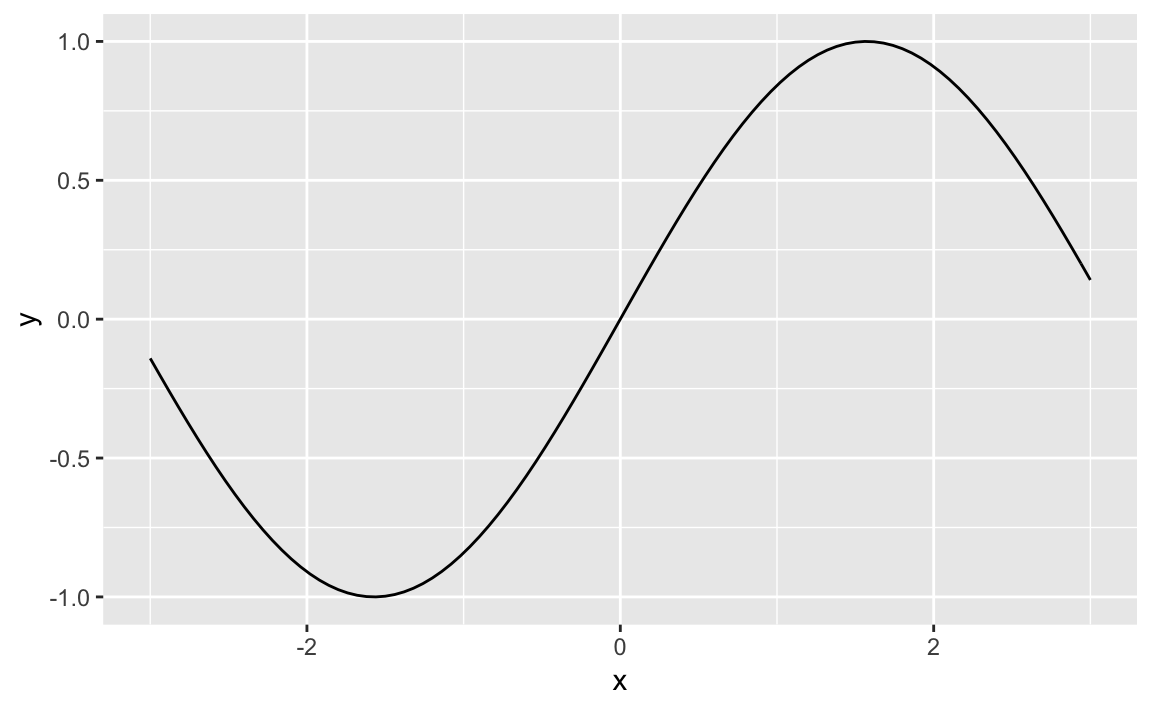

The ggplot function stat_function will graph a function across a

range. In Figure 10-41 we plot a sin wave across the

range -3 to 3.

ggplot(data.frame(x=c(-3,3)))+aes(x)+stat_function(fun=sin)

Figure 10-41. Sin Wave Plot

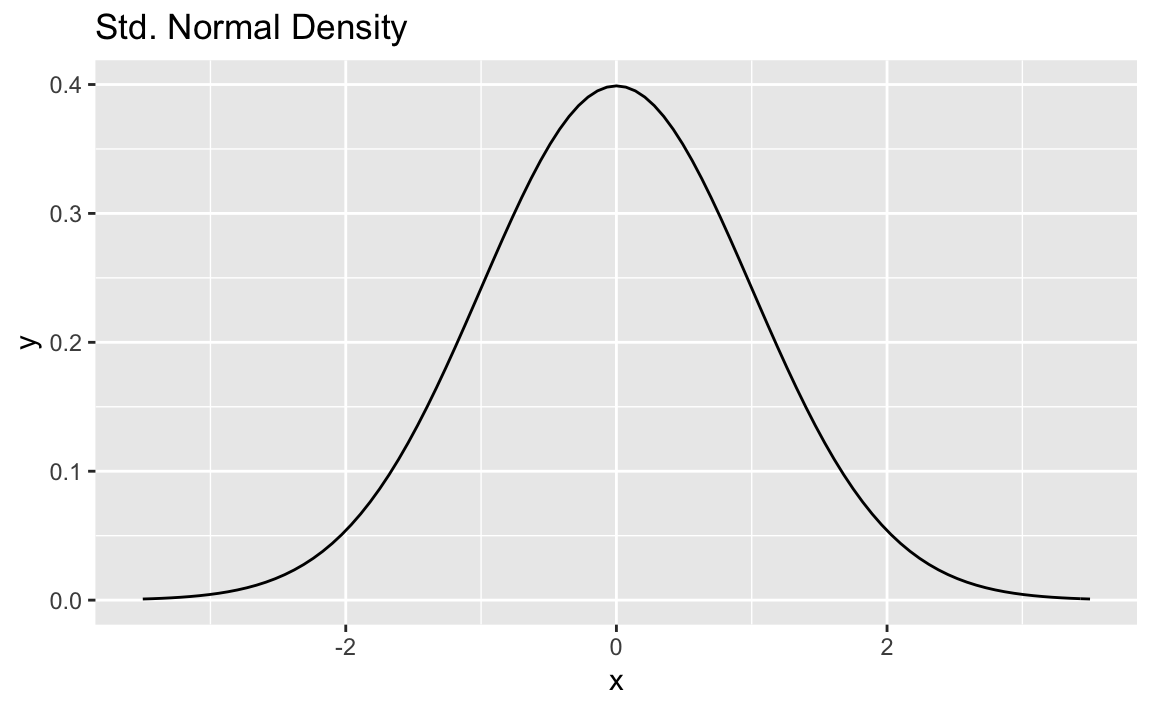

Discussion

It’s pretty common to want to plot a statistical function, such as a

normal distribution across a given range. The stat_function in

ggplot allows us to do thise. We need only supply a data frame with

x value limits and stat_function will calculate the y values, and

plot the results:

ggplot(data.frame(x=c(-3.5,3.5)))+aes(x)+stat_function(fun=dnorm)+ggtitle("Std. Normal Density")

Notice in the chart above we use ggtitle to set the title. If setting

multiple text elements in a ggplot we use labs but when just adding

a title, ggtitle is more concise than

labs(title='Std. Normal Density') although they accomplish the same

thing. See ?labs for more discussion of labels with ggplot

stat_function can graph any function that takes one argument and

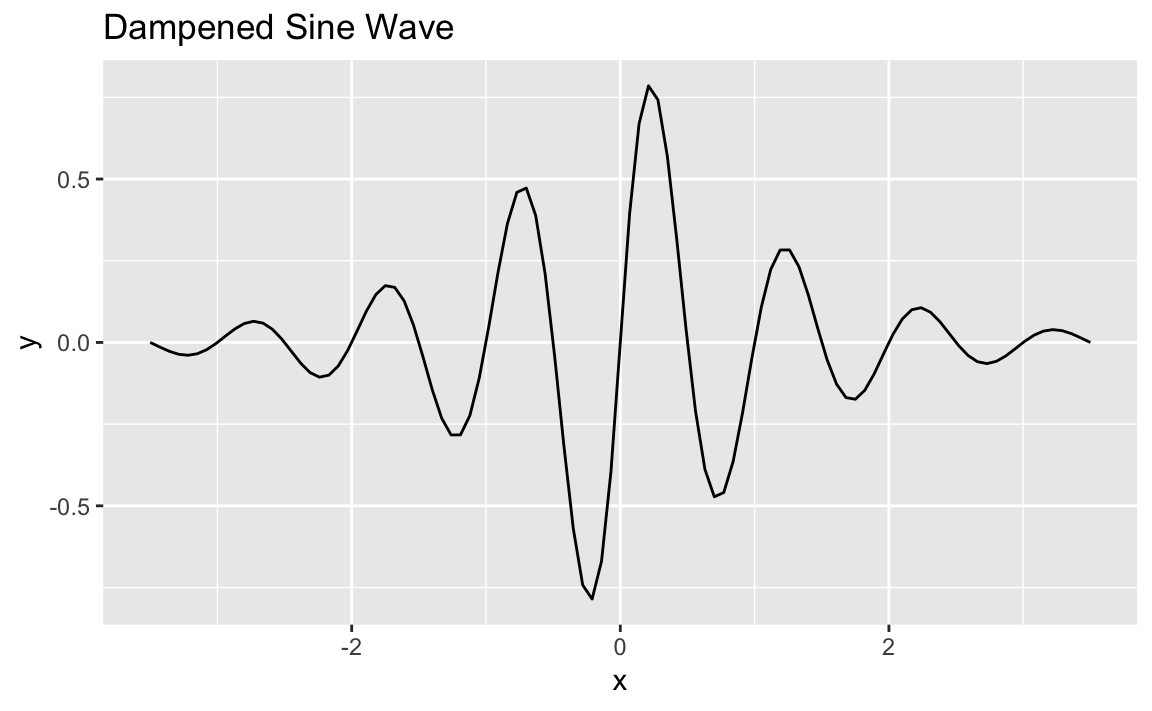

returns one value. Let’s create a function and then plot it. Our

function is a dampened sin wave that is a sin wave that loses amplitude

as it moves away from 0:

f<-function(x)exp(-abs(x))*sin(2*pi*x)

ggplot(data.frame(x=c(-3.5,3.5)))+aes(x)+stat_function(fun=f)+ggtitle("Dampened Sine Wave")

See Also

See Recipe X-X for how to define a function.

Pausing Between Plots

Problem

You are creating several plots, and each plot is overwriting the previous one. You want R to pause between plots so you can view each one before it’s overwritten.

Solution

There is a global graphics option called ask. Set it to TRUE, and R

will pause before each new plot. We turn on this option by passing it to

the par function which sets parameters:

par(ask=TRUE)

When you are tired of R pausing between plots, set it to FALSE:

par(ask=FALSE)

Discussion

When ask is TRUE, R will print this message immediately before

starting a new plot:

Hit <Return> to see next plot:

When you are ready, hit the return or enter key and R will begin the next plot.

This is a Base R Graphics function but you can use it in ggplot if you

wrap your plot function in a print statement in order to get prompted.

Below is an example of a loop that prints a random set of points 5

times. If you run this loop in RStudio, you will be prompted between

each graphic. Notice how we wrap g inside a print call:

par(ask=TRUE)for(iin(11:15)){g<-ggplot(data.frame(x=rnorm(i),y=1:i))+aes(x,y)+geom_point()(g)}# don't forget to turn ask off after you're donepar(ask=FALSE)

See Also

If one graph is overwriting another, consider using “Displaying Several Figures on One Page” to plot multiple graphs in one frame. See Recipe X-X for more about changing graphical parameters.

JDL EDIT MARK

Displaying Several Figures on One Page

Problem

You want to display several plots side by side on one page.

Solution

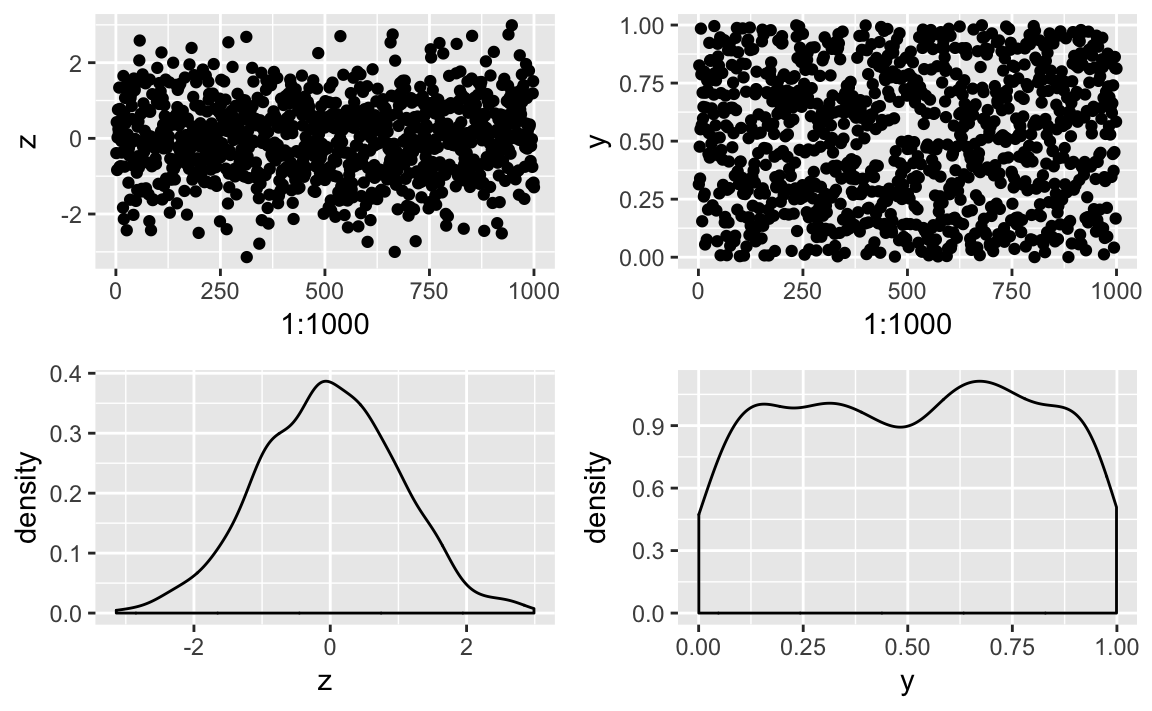

# example dataz<-rnorm(1000)y<-runif(1000)# plot elementsp1<-ggplot()+geom_point(aes(x=1:1000,y=z))p2<-ggplot()+geom_point(aes(x=1:1000,y=y))p3<-ggplot()+geom_density(aes(z))p4<-ggplot()+geom_density(aes(y))

There are a number of ways to put ggplot graphics into a grid, but one

of the easiest to use and understand is patchwork by Thomas Lin

Pedersen. When this book was written, patchwork was not availiable on

CRAN, but can be installed using devtools:

devtools::install_github("thomasp85/patchwork")

After installing the package we can use it to plot mulitple ggplot

objects using a + between the objects then a call to plot_layout to

arrange the images into a grid as shown in Figure 10-42:

library(patchwork)p1+p2+p3+p4

Figure 10-42. A Patchwork Plot

patchwork supports grouping with parenthesis and using / to put

groupings under other elements as illustrated in Figure 10-43.

p3/(p1+p2+p4)

Figure 10-43. A Patchwork 1 / 2 Plot

Discussion

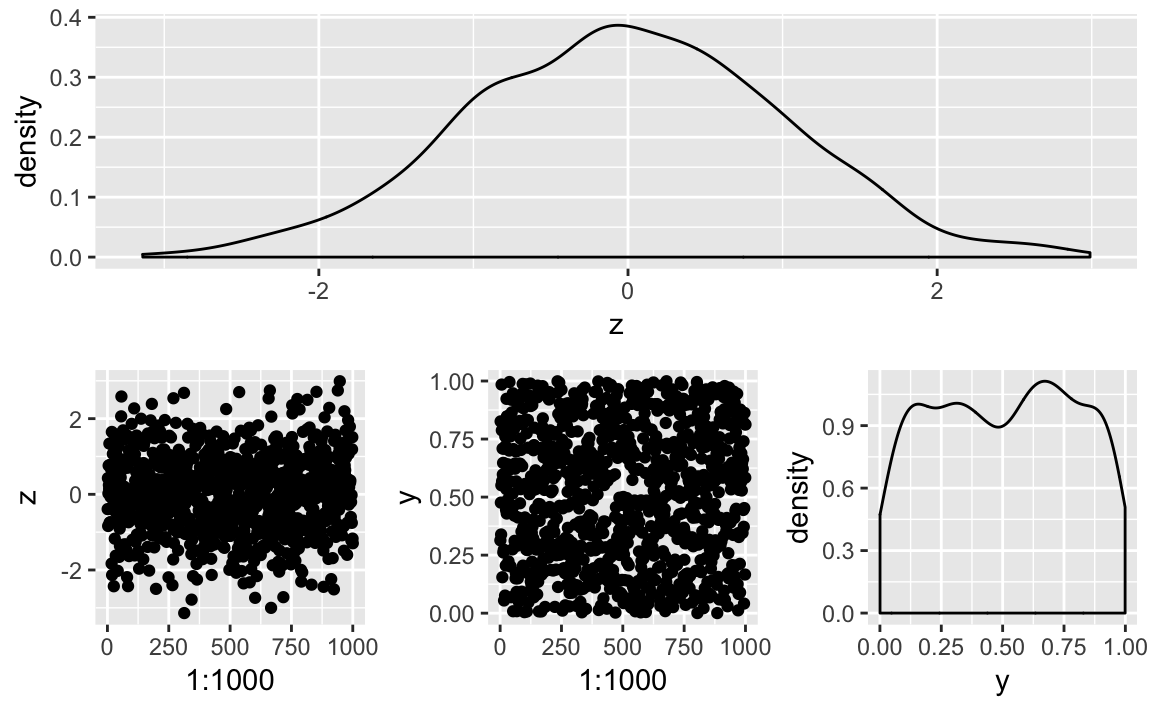

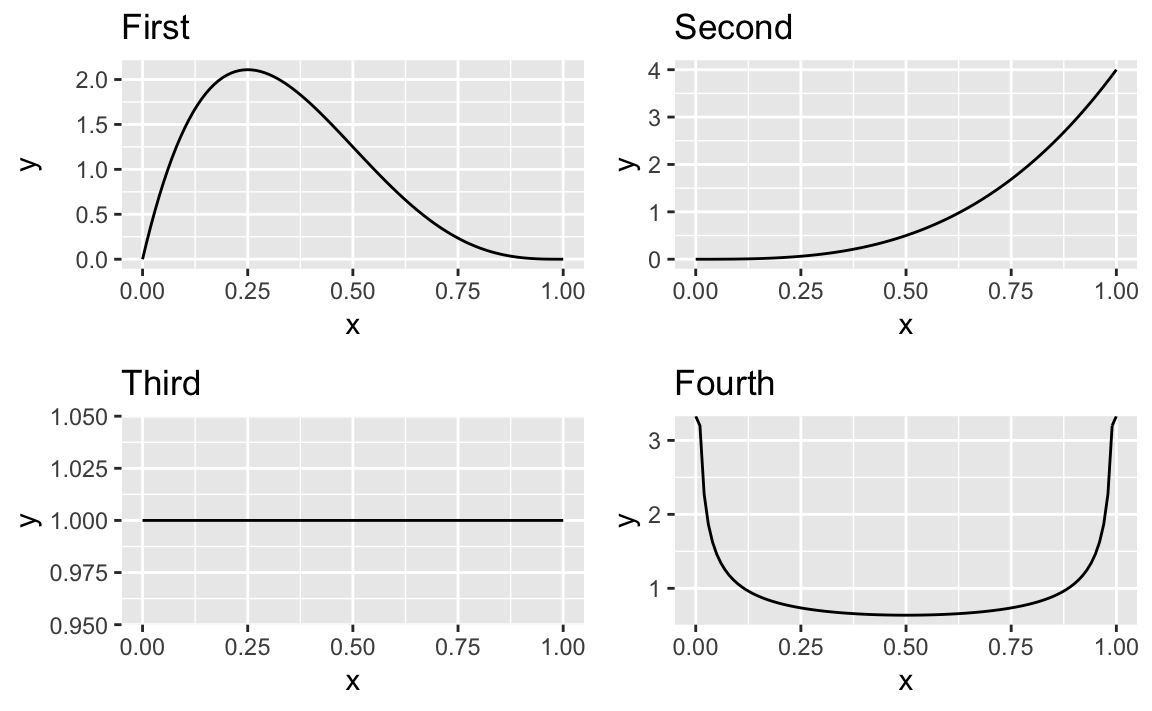

Let’s use a multifigure plot to display four different beta

distributions. Using ggplot and the patchwork package, we can create

a 2 x 2 layout effect by greating four graphics objects then print them

using the + notation from Patchwork:

library(patchwork)df<-data.frame(x=c(0,1))g1<-ggplot(df)+aes(x)+stat_function(fun=function(x)dbeta(x,2,4))+ggtitle("First")g2<-ggplot(df)+aes(x)+stat_function(fun=function(x)dbeta(x,4,1))+ggtitle("Second")g3<-ggplot(df)+aes(x)+stat_function(fun=function(x)dbeta(x,1,1))+ggtitle("Third")g4<-ggplot(df)+aes(x)+stat_function(fun=function(x)dbeta(x,.5,.5))+ggtitle("Fourth")g1+g2+g3+g4+plot_layout(ncol=2,byrow=TRUE)

To lay the images out in columns order we could pass the byrow=FALSE

to plot_layout:

g1+g2+g3+g4+plot_layout(ncol=2,byrow=FALSE)

See Also

“Plotting a Density Function” discusses plotting of density functions as we do above.

The grid package and the lattice package contain additional tools

for multifigure layouts with Base Graphics.

Writing Your Plot to a File

Problem

You want to save your graphics in a file, such as a PNG, JPEG, or PostScript file.

Solution

With ggplot figures we can use ggsave to save a displayed image to a

file. ggsave will make some default assumptions about size and file

type for you, allowing you to only specify a filename:

ggsave("filename.jpg")

The file type is derived from the extension you use in the filename you

pass to ggsave. You can control details of size, filetype, and scale

by passing parameters to ggsave. See ?ggsave for specific details.

Discussion

In RStudio, a shortcut is to click on Export in the Plots window and

then click on Save as Image, Save as PDF, or Copy to Clipboard.

The save options will prompt you for a file type and a file name before

writing the file. The Copy to Clipboard option can be handy if you are

manually copying and pasting your graphics into a presentation or word

processor.

Remember that the file will be written to your current working directory

(unless you use an absolute file path), so be certain you know which

directory is your working directory before calling savePlot.

In a non-interactive script using ggplot you can pass plot objects

directly to ggsave so they need not be displayed before saving. In the

prior recipe we created a plot object called g1. We can save it to a

file like this:

ggsave("g1.png",plot=g1,units="in",width=5,height=4)

Note that the units for height and width in ggsave are specified

with the units parameter. In this case we used in for inches, but

ggsave also supports mm and cm for the more metricly inclined.

See Also

See “Getting and Setting the Working Directory” for more about the current working directory.