Chapter 3. Navigating the Software

Introduction

R is a big chunk of software, first and foremost. You will inevitably spend time doing what one does with any big piece of software: configuring it, customizing it, updating it, and fitting it into your computing environment. This chapter will help you perform those tasks. There is nothing here about numerics, statistics, or graphics. This is all about dealing with R as software.

Getting and Setting the Working Directory

Problem

You want to change your working directory. Or you just want to know what it is.

Solution

- R Studio

-

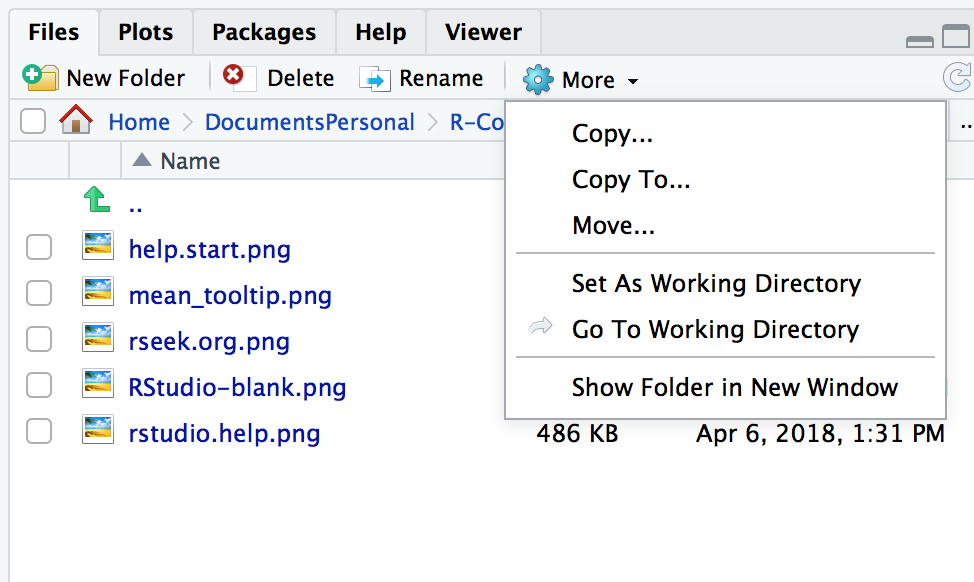

Navigate to a directory in the file pane. Then from the File Pane, select More → Set as Working Directory as shown in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. R Studio: Set Working Directory

- Console

-

Use

getwdto report the working directory, and usesetwdto change it:

getwd()#> [1] "/Users/jal/DocumentsPersonal/R-Cookbook"

setwd("~/Documents/MyDirectory")

Discussion

Your working directory is important because it is the default location for all file input and output—including reading and writing data files, opening and saving script files, and saving your workspace image. When you open a file and do not specify an absolute path, R will assume that the file is in your working directory.

If you’re using R Studio projects, your default working directory will be the home directory of the project. See “Creating a new R Studio Project” for more about creating R Studio Projects.

See Also

See “Dealing with “Cannot Open File” in Windows” for dealing with filenames in Windows.

Creating a new R Studio Project

Problem

You want to create a new R Studio Project to keep all your files related to a specific project.

Discussion

Projects are a powerful concept that’s specific to R Studio. Projects set your working directory to the project directory but they add considerable additional help to maintaining your project.

Projects help you by doing the following:

-

Sets your working directory to the project directory

-

Preserves window state in R Studio so when you return to a project your windows are all as you left them. This includes opening any files you had open when you last saved your project.

-

Preserves R Studio Project settings

To hold your project settings, R Studio will create a project file with an .Rproj extension in the project directory. The project file contains your project settings and if you open the project file in R Studio it works like a shortcut for opening the project. In addition, R Studio creates a hidden directory named .Rporj.user to house temporary files related to your project.

We recommend that any time you work in R that is non trivial you should create an R Studio Project. Projects help you keep organized and make workflow on your projects easier.

Saving Your Workspace

Problem

You want to save your workspace from the console or within a program.

Solution

Call the save.image function:

save.image()

Discussion

Your workspace holds your R variables and functions, and it is created

when R starts. The workspace is held in your computer’s main memory and

lasts until you exit from R, at which time you can save it. The contents

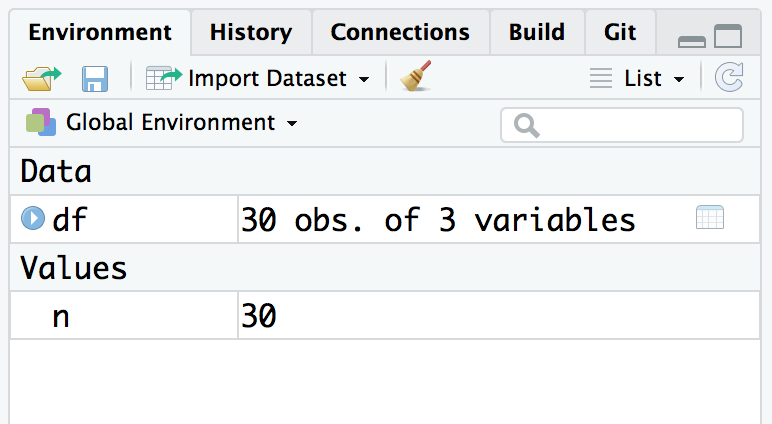

of your workspace can be easily seen in R Studio in the Environment

tab shown in Figure 2-1

However, you may want to save your workspace without exiting R. Becuase

you know bad things mysteriously happen when you close your laptop to

carry it home. Use the save.image function.

The workspace is written to a file called .RData in the working

directory. When R starts, it looks for that file and, if found,

initializes the workspace from it.

A sad fact is that the workspace does not include your open graphs: that cool graph on your screen disappears when you exit R. The workspace also does not include saving the position of your windows or your R Studio settings. This is why we recommend using R Studio projects as a project includes your workspace and a whole lot more.

See Also

See “Installing R Studio” for how to save your workspace when exiting R and “Getting and Setting the Working Directory” for setting the working directory.

Viewing Your Command History

Problem

You want to see your recent sequence of commands.

Solution

Depending on what you are trying to accomplish, you can use a few different methods to access prior command history. If you are in the Console you can press the up arrow to interactively scroll through past commands.

If you want to see a listing of past commands, you can either execute

the history function, or the History window in R Studio to view your

most recent input:

history()

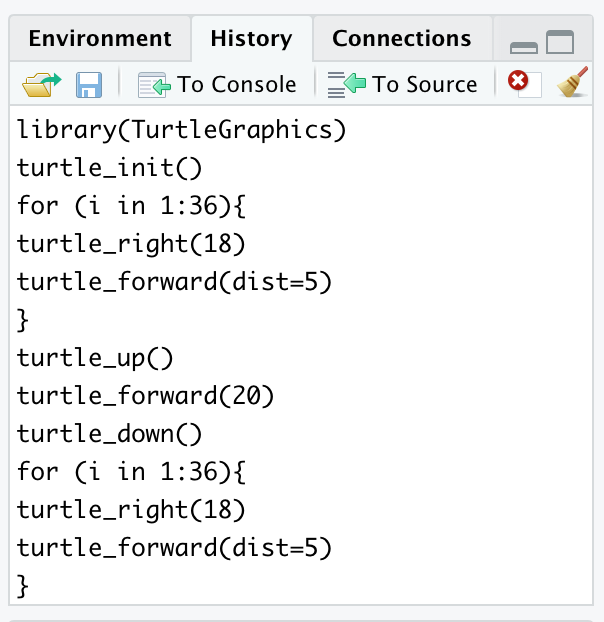

In R Studio typing history() into the Console simply activates the

History pane in R Studio (Figure 3-2). You could also make

that pane visable by clicking on it with your cursor.

Figure 3-2. R Studio History Pane

Discussion

The history function will display your most recent commands. In R

Studio the history command will activate the History window. If you

were running R outside of R Studio, history shows the most recent 25

lines, but you can request more:

history(100)# Show 100 most recent lines of historyhistory(Inf)# Show entire saved history

From within R Studio, the History tab shows an exhaustive list of past commands in chronological order with the most recent at the bottom of the list. In R Studio you can highlight past commands with your cursor then click on the “To Console” or “To Source” to copy past commands into the console or source editor, respectively. This can be terribly handy when you’ve done interactive data analysis and then decide you want to save some past steps to a source file for later use.

From the console you can see your history by simply scrolling backward through your input by pressing the up arrow causing your previous typing to reappear, one line at a time.

If you’ve exited from R or R Studio then you can still see your command

history. It saves the history in a file called .Rhistory in the

working directory. Open the file with a text editor and then scroll to

the bottom; you will see your most recent typing.

Saving the Result of the Previous Command

Problem

You typed an expression into R that calculated the value, but you forgot to save the result in a variable.

Solution

A special variable called .Last.value saves the value of the most

recently evaluated expression. Save it to a variable before you type

anything else.

Discussion

It is frustrating to type a long expression or call a long-running

function but then forget to save the result. Fortunately, you needn’t

retype the expression nor invoke the function again—the result was saved

in the .Last.value variable:

aVeryLongRunningFunction()# Oops! Forgot to save the result!x<-.Last.value# Capture the result now

A word of caution: the contents of .Last.value are overwritten every

time you type another expression, so capture the value immediately. If

you don’t remember until another expression has been evaluated, it’s too

late!

See Also

See “Viewing Your Command History” to recall your command history.

Displaying Loaded Packages via the Search Path

Problem

You want to see the list of packages currently loaded into R.

Solution

Use the search function with no arguments:

search()

Discussion

The search path is a list of packages that are currently loaded into memory and available for use. Although many packages may be installed on your computer, only a few of them are actually loaded into the R interpreter at any given moment. You might be wondering which packages are loaded right now.

With no arguments, the search function returns the list of loaded

packages. It produces an output like this:

search()#> [1] ".GlobalEnv" "package:knitr" "package:forcats"#> [4] "package:stringr" "package:dplyr" "package:purrr"#> [7] "package:readr" "package:tidyr" "package:tibble"#> [10] "package:ggplot2" "package:tidyverse" "package:stats"#> [13] "package:graphics" "package:grDevices" "package:utils"#> [16] "package:datasets" "package:methods" "Autoloads"#> [19] "package:base"

Your machine may return a different result, depending on what’s

installed there. The return value of search is a vector of strings.

The first string is ".GlobalEnv", which refers to your workspace. Most

strings have the form "package:packagename", which indicates that the

package called packagename is currently loaded into R. In the above

example, you can see many Tidyverse packages installed, including

purrr, ggplot2, tibble, etc.

R uses the search path to find functions. When you type a function name, R searches the path—in the order shown—until it finds the function in a loaded package. If the function is found, R executes it. Otherwise, it prints an error message and stops. (There is actually a bit more to it: the search path can contain environments, not just packages, and the search algorithm is different when initiated by an object within a package; see the R Language Definition for details.)

Since your workspace (.GlobalEnv) is first in the list, R looks for

functions in your workspace before searching any packages. If your

workspace and a package both contain a function with the same name, your

workspace will “mask” the function; this means that R stops searching

after it finds your function and so never sees the package function.

This is a blessing if you want to override the package function…and a

curse if you still want access to the package function. If you find

yourself feeling cursed because you (or some package you loaded)

overrode a function (or other object) from an existing loaded package,

you can use the full environment::name form to call an object from a

loaded package environment. For example, if you wanted to call the

dplyr function count you could do so using dplyr::count. Using the

full explicit name to call a function will work even if you have not

loaded the package. So if you have dplyr installed but not loaded, you

can still call dplyr::count. It is becoming increasingly common with

online examples to show the full packagename::function in examples.

While this removes ambiguity about where a function comes from, it makes

example code very wordy.

Note that R will only include loaded packages in the search path. So

if you have installed a package, but not loaded it by using

library(packagename) then R will not add that package to the search

path.

R also uses the search path to find R datasets (not files) or any other object via a similar procedure.

Unix & Mac users: don’t confuse the R search path with the Unix search

path (the PATH environment variable). They are conceptually similar

but two distinct things. The R search path is internal to R and is used

by R only to locate functions and datasets, whereas the Unix search path

is used by the OS to locate executable programs.

See Also

See “Accessing the Functions in a Package” for loading packages into R, “Viewing the List of Installed Packages” for the list of installed packages (not just loaded packages), and “Accessing Data Frame Contents More Easily” for inserting data frames into the search path.

Accessing the Functions in a Package

Problem

A package installed on your computer is either a standard package or a package downloaded by you. When you try using functions in the package, however, R cannot find them.

Solution

Use either the library function or the require function to load the

package into R:

library(packagename)

Discussion

R comes with several standard packages, but not all of them are

automatically loaded when you start R. Likewise, you can download and

install many useful packages from CRAN, or Github, but they are not

automatically loaded when you run R. The MASS package comes standard

with R, for example, but you could get this message when using the lda

function in that package:

lda(x)#> Error in lda(x): could not find function "lda"

R is complaining that it cannot find the lda function among the

packages currently loaded into memory.

When you use the library function or the require function, R loads

the package into memory and its contents become immediately available to

you:

my_model<-lda(cty~displ+year,data=mpg)#> Error in lda(cty ~ displ + year, data = mpg): could not find function "lda"library(MASS)# Load the MASS library into memory#>#> Attaching package: 'MASS'#> The following object is masked from 'package:dplyr':#>#> selectmy_model<-lda(cty~displ+year,data=mpg)# Now R can find the function

Before calling library, R does not recognize the function name.

Afterward, the package contents are available and calling the lda

function works.

Notice that you needn’t enclose the package name in quotes.

The require function is nearly identical to library. It has two

features that are useful for writing scripts. It returns TRUE if the

package was successfully loaded and FALSE otherwise. It also generates

a mere warning if the load fails—unlike library, which generates an

error.

Both functions have a key feature: they do not reload packages that are already loaded, so calling twice for the same package is harmless. This is especially nice for writing scripts. The script can load needed packages while knowing that loaded packages will not be reloaded.

The detach function will unload a package that is currently loaded:

detach(package:MASS)

Observe that the package name must be qualified, as in package:MASS.

One reason to unload a package is that it contains a function whose name conflicts with a same-named function lower on the search list. When such a conflict occurs, we say the higher function masks the lower function. You no longer “see” the lower function because R stops searching when it finds the higher function. Hence unloading the higher package unmasks the lower name.

See Also

Accessing Built-in Datasets

Problem

You want to use one of R’s built-in datasets. Or you want to access one of the datasets that comes with another package.

Solution

The standard datasets distributed with R are already available to you,

since the datasets package is in your search path. If you’ve loaded

any other packages, datasets that come with those loaded packages will

also be availiable in your search path.

To access datasets in other packages, use the data function while

giving the dataset name and package name:

data(dsname,package="pkgname")

Discussion

R comes with many built-in datasets. Other packages, such as dplyr and

ggplot2 also come with example data that’s used in the examples found

in their help files. These datasets are useful when you are learning

about R, since they provide data with which to experiment.

Many datasets are kept in a package called (naturally enough)

datasets, which is distributed with R. That package is in your search

path, so you have instant access to its contents. For example, you can

use the built-in dataset called pressure:

head(pressure)#> temperature pressure#> 1 0 0.0002#> 2 20 0.0012#> 3 40 0.0060#> 4 60 0.0300#> 5 80 0.0900#> 6 100 0.2700

If you want to know more about pressure, use the help function to

learn about it and other datasets:

help(pressure)# Bring up help page for pressure dataset

You can see a table of contents for datasets by calling the data

function with no arguments:

data()# Bring up a list of datasets

Any R package can elect to include datasets that supplement those

supplied in datasets. The MASS package, for example, includes many

interesting datasets. Use the data function to load a dataset from a

specific package by using the package argument. MASS includes a

dataset called Cars93, which you can load into memeory in this way:

data(Cars93,package="MASS")

After this call to data, the Cars93 dataset is available to you;

then you can execute summary(Cars93), head(Cars93), and so forth.

When attaching a package to your search list (e.g., via

library(MASS)), you don’t need to call data. Its datasets become

available automatically when you attach it.

You can see a list of available datasets in MASS, or any other

package, by using the data function with a package argument and no

dataset name:

data(package="pkgname")

See Also

See “Displaying Loaded Packages via the Search Path” for more about the search path and “Accessing the Functions in a Package” for more

about packages and the library function.

Viewing the List of Installed Packages

Problem

You want to know what packages are installed on your machine.

Solution

Use the library function with no arguments for a basic list. Use

installed.packages to see more detailed information about the

packages.

Discussion

The library function with no arguments prints a list of installed

packages. The list can be quite long.

library()

In R Studio, the list is displayed in a new tab in the editor window.

You can get more details via the installed.packages function, which

returns a matrix of information regarding the packages on your machine.

Each row corresponds to one installed package. The columns contain the

information such as package name, library path, and version. The

information is taken from R’s internal database of installed packages.

To extract useful information from this matrix, use normal indexing

methods. The following snippet calls installed.packages and extracts

both the Package and Version columns for the first 5 packages,

letting you see what version of each package is installed:

installed.packages()[1:5,c("Package","Version")]#> Package Version#> abind "abind" "1.4-5"#> ade4 "ade4" "1.7-13"#> adegenet "adegenet" "2.1.1"#> ape "ape" "5.2"#> assertthat "assertthat" "0.2.0"

See Also

See “Accessing the Functions in a Package” for loading a package into memory.

Installing Packages from CRAN

Problem

You found a package on CRAN, and now you want to install it on your computer.

Solution

- R Console

-

Use the

install.packagesfunction, putting the name of the package in quotes:

install.packages("packagename")

- R Studio

-

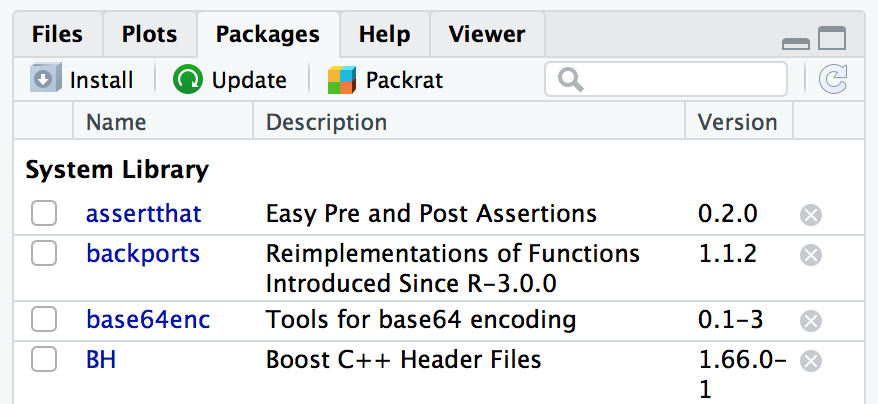

The Packages window in R Studio helps make installing new R packages straghforward. All packages that are installed on your machine are listed in the packages window, along with description and version information. To load a new package from CRAN, click on the install button near the top of the Packages window shown in Figure 3-3

Figure 3-3. R Studio Packages Window

Discussion

Installing a package locally is the first step toward using it. If you are installing packages outside of R Studio, the installer may prompt you for a mirror site from which it can download the package files. It will then display a list of CRAN mirror sites. Select one close to you.

The official CRAN server is a relatively modest machine generously hosted by the Department of Statistics and Mathematics at WU Wien, Vienna, Austria. If every R user downloaded from the official server, it would buckle under the load, so there are numerous mirror sites around the globe. In R Studio the default CRAN server is set to be the R Studio CRAN mirror. This is an excellent choice if you are in the USA. The R Studio CRAN mirror is accessable to all R users, not just those running the R Studio IDE.

If the new package depends upon other packages that are not already installed locally, then the R installer will automatically download and install those required packages. This is a huge benefit that frees you from the tedious task of identifying and resolving those dependencies.

There is a special consideration when installing on Linux or Unix. You can install the package either in the system-wide library or in your personal library. Packages in the system-wide library are available to everyone; packages in your personal library are (normally) used only by you. So a popular, well-tested package would likely go in the system-wide library whereas an obscure or untested package would go into your personal library.

By default, install.packages assumes you are performing a system-wide

install. If you do not have sufficient user permissions to install in

the system wide library location, R will ask if you would like to

install the package in a user library. The default that R suggests is

typically a good choice. However, if you would like to control the path

for your library location, you can use the lib= argument of the

install.packages function:

install.packages("packagename",lib="~/lib/R")

See Also

See “Finding Relevant Functions and Packages” for ways to find relevant packages and “Accessing the Functions in a Package” for using a package after installing it.

Installing a Package from Github

Problem

You’ve found an interesting package which you’d like to try. However, the author has not yet published the package on CRAN, but has published it on Github. You’d like to install the package directly from Github.

Solution

Ensure you have the devtools package installed and loaded:

Then use install_github and the name of the Github repository to

install directly from Github. For example, to install Thomas Lin

Pederson’s tidygraph package, you could execute the following:

install_github("thomasp85/tidygraph")

Discussion

The devtools package is a package that contains helper functions for

installing R packages from remote (non-ss) repositories, like Github. If

a package has been built as an R package and then hosted on Github you

can install the package using the install_github function by passing

the Github username and repository name as a string parameter. You can

determine the Github username and repo name from the github URL, or from

the top of the Github page like in the example shown in ???.

. image::images_v2/github.shot.png[]

Setting or Changing a Default CRAN Mirror

Problem

You are downloading packages. You want to set or change your default CRAN mirror.

Solution

In R Studio, you can change your default CRAN mirror from the R Studio Preferences menu shown in ???:

. image::images_v2/rstudio.package.pref.png[]

If you are running R without R Studio you can change your CRAN mirror

using the following solution. This solution assumes you have an

.Rprofile, as described in “Customizing R Startup”:

-

Call the

choosessmirrorfunction:

choosessmirror()

R will present a list of CRAN mirrors.

-

Select a CRAN mirror from the list and press OK.

-

To get the URL of the mirror, look at the first element of the

reposoption:

options("repos")[[1]][1]

-

Add this line to your

.Rprofilefile. If you want the R Studio CRAN mirror, you would do the following:

options(repos=c(CRAN="http://cran.rstudio.com"))

where URL is the URL of the mirror.

Discussion

When you install packages, you probably use the same CRAN mirror each time (namely, the mirror closest to you or the R Studio mirror). You may want to change that mirror to use a different mirror that’s closer to you or controlled by your employer. Use this solution to change your repo so that every time you start R or R Studio you will be using your desired repo.

The repos option is the name of your default mirror. The

choosessmirror function has the important side effect of setting the

repos option according to your selection. The problem is that R

forgets the setting when it exits, leaving no permanent default. By

setting repos in your .Rprofile, you restore the setting every time

R starts.

See Also

See “Customizing R Startup” for

more about the .Rprofile file and the options function.

Running a Script

Problem

You captured a series of R commands in a text file. Now you want to execute them.

Solution

The source function instructs R to read the text file and execute its

contents:

source("myScript.R")

Discussion

When you have a long or frequently used piece of R code, capture it

inside a text file. That lets you easily rerun the code without having

to retype it. Use the source function to read and execute the code,

just as if you had typed it into the R console.

Suppose the file hello.R contains this one, familiar greeting:

("Hello, World!")

Then sourcing the file will execute the file contents:

source("hello.R")#> [1] "Hello, World!"

Setting echo=TRUE will echo the script lines before they are executed,

with the R prompt shown before each line:

source("hello.R",echo=TRUE)#>#> > print("Hello, World!")#> [1] "Hello, World!"

See Also

See “Typing Less and Accomplishing More” for running blocks of R code inside the GUI.

Running a Batch Script

Problem

You are writing a command script, such as a shell script in Unix or OS X or a BAT script in Windows. Inside your script, you want to execute an R script.

Solution

Run the R program with the CMD BATCH subcommand, giving the script

name and the output file name:

R CMD BATCH scriptfile outputfile

If you want the output sent to stdout or if you need to pass

command-line arguments to the script, consider the Rscript command

instead:

Rscript scriptfile arg1 arg2 arg3

Discussion

R is normally an interactive program, one that prompts the user for input and then displays the results. Sometimes you want to run R in batch mode, reading commands from a script. This is especially useful inside shell scripts, such as scripts that include a statistical analysis.

The CMD BATCH subcommand puts R into batch mode, reading from

scriptfile and writing to outputfile. It does not interact with a user.

You will likely use command-line options to adjust R’s batch behavior to

your circumstances. For example, using --quiet silences the startup

messages that would otherwise clutter the output:

R CMD BATCH --quiet myScript.R results.out

Other useful options in batch mode include the following:

--slave-

Like

--quiet, but it makes R even more silent by inhibiting echo of the input. --no-restore-

At startup, do not restore the R workspace. This is important if your script expects R to begin with an empty workspace.

--no-save-

At exit, do not save the R workspace. Otherwise, R will save its workspace and overwrite the

.RDatafile in the working directory. --no-init-file-

Do not read either the

.Rprofileor~/.Rprofilefiles.

The CMD BATCH subcommand normally calls proc.time when your script

completes, showing the execution time. If this annoys you then end your

script by calling the q function with runLast=FALSE, which will

prevent the call to proc.time.

The CMD BATCH subcommand has two limitations: the output always goes

to a file, and you cannot easily pass command-line arguments to your

script. If either limitation is a problem, consider using the Rscript

program that comes with R. The first command-line argument is the script

name, and the remaining arguments are given to the script:

Rscript myScript.R arg1 arg2 arg3

Inside the script, the command-line arguments can be accessed by calling

commandArgs, which returns the arguments as a vector of strings:

argv<-commandArgs(TRUE)

The Rscript program takes the same command-line options as

CMD BATCH, which were just described.

Output is written to stdout, which R inherits from the calling shell script, of course. You can redirect the output to a file by using the normal redirection:

Rscript --slave myScript.R arg1 arg2 arg3 >results.out

Here is a small R script, arith.R, that takes two command-line

arguments and performs four arithmetic operations on them:

argv<-commandArgs(TRUE)x<-as.numeric(argv[1])y<-as.numeric(argv[2])cat("x =",x,"\n")cat("y =",y,"\n")cat("x + y = ",x+y,"\n")cat("x - y = ",x-y,"\n")cat("x * y = ",x*y,"\n")cat("x / y = ",x/y,"\n")

The script is invoked like this:

Rscript arith.R 2 3.1415

which produces the following output:

x=2y=3.1415x+y=5.1415x-y=-1.1415x*y=6.283x/y=0.6366385

On Linux, Unix, or Mac, you can make the script fully self-contained by

placing a #! line at the head with the path to the Rscript program.

Suppose that Rscript is installed in /usr/bin/Rscript on your

system. Then adding this line to arith.R makes it a self-contained

script:

#!/usr/bin/Rscript --slaveargv <- commandArgs(TRUE)x <- as.numeric(argv[1]). .(etc.).

At the shell prompt, we mark the script as executable:

chmod +x arith.R

Now we can invoke the script directly without the Rscript prefix:

arith.R 2 3.1415

See Also

See “Running a Script” for running a script from within R.

Locating the R Home Directory

Problem

You need to know the R home directory, which is where the configuration and installation files are kept.

Solution

R creates an environment variable called R_HOME that you can access by

using the Sys.getenv function:

Sys.getenv("R_HOME")#> [1] "/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Resources"

Discussion

Most users will never need to know the R home directory. But system administrators or sophisticated users must know in order to check or change the R installation files.

When R starts, it defines an environment variable (not an R variable)

called R_HOME, which is the path to the R home directory. The

Sys.getenv function can retrieve its value. Here are examples by

platform. The exact value reported will almost certainly be different on

your own computer:

On Windows

> Sys.getenv("R_HOME") [1] "C:/PROGRA~1/R/R-34~1.4"

On OS X

> Sys.getenv("R_HOME")

[1] "/Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Resources"

On Linux or Unix

> Sys.getenv("R_HOME")

[1] "/usr/lib/R"

The Windows result looks funky because R reports the old, DOS-style

compressed path name. The full, user-friendly path would be

C:\Program Files\R\R-3.4.4 in this case.

On Unix and OS X, you can also run the R program from the shell and use

the RHOME subcommand to display the home directory:

R RHOME

# /usr/lib/R

Note that the R home directory on Unix and OS X contains the

installation files but not necessarily the R executable file. The

executable could be in /usr/bin while the R home directory is, for

example, /usr/lib/R.

Customizing R Startup

Problem

You want to customize your R sessions by, for instance, changing configuration options or preloading packages.

Solution

Create a script called .Rprofile that customizes your R session. R

will execute the .Rprofile script when it starts. The placement of

.Rprofile depends upon your platform:

- OS X, Linux, or Unix

-

Save the file in your home directory (

~/.Rprofile). - Windows

-

Save the file in your

Documentsdirectory.

Discussion

R executes profile scripts when it starts, freeing you from repeatedly loading often-used packages or tweaking the R configuration options.

You can create a profile script called .Rprofile and place it in your

home directory (OS X, Linux, Unix) or your Documents directory

(Windows). The script can call functions to customize your sessions,

such as this simple script that sets two environment variables and sets

the console prompt to R>:

Sys.setenv(DB_USERID="my_id")Sys.setenv(DB_PASSWORD="My_Password!")options(prompt="R> ")

The profile script executes in a bare-bones environment, so there are limits on what it can do. Trying to open a graphics window will fail, for example, because the graphics package is not yet loaded. Also, you should not attempt long-running computations.

You can customize a particular project by putting an .Rprofile file in

the directory that contains the project files. When R starts in that

directory, it reads the local .Rprofile file; this allows you to do

project-specific customizations (e.g., setting your console prompt to a

specific project name). However, if R finds a local profile then it does

not read the global profile. That can be annoying, but it’s easily

fixed: simply source the global profile from the local profile. On

Unix, for instance, this local profile would execute the global profile

first and then execute its local material:

source("~/.Rprofile")## ... remainder of local .Rprofile...#

Setting Options

Some customizations are handled via calls to the options function,

which sets the R configuration options. There are many such options, and

the R help page for options lists them all:

help(options)

Here are some examples:

browser="path"-

Path of default HTML browser

digits=n-

Suggested number of digits to print when printing numeric values

editor="path"-

Default text editor

prompt="string"-

Input prompt

repos="url"-

URL for default repository for packages

warn=n-

Controls display of warning messages

Reproducibility

Many of us use certain packages over and over in all of our script. For

example, we use the tidyverse packages in almost all our scripts. It

is tempting to load these packages in your .Rprofile so that they are

always available without typing anything. As a matter of fact, this

advice was given in the first edition of this book. However, the

downside of loading packages in your .Rprofile is reproducibility. If

someone else (or you, on another machine) tries to run your script, they

may not realize that you had loaded packages in your .Rprofile. Your

script might not work for them, depending on which packages they load.

So while it might be convenient to load packages in .Rprofile you will

play better with collaborators (and your future self) if you explicitly

call library(packagename) in your R scripts.

Another issue with reproducability and the .Rprofile is when users

change calculation default behaviors of R inside their .Rprofile. An

example of this would be setting options(stringsAsFactors = FALSE).

This is appealing as many users would prefer this default. However, if

someone runs the script without this option being set, they will get

different results or not be able to run the script at all. This can lead

to considerable frustration.

As a guideline, you should primarly put things in the .Rprofile that:

-

Change the look and feel of R (e.g.

digits) -

Are specific to your local environment (e.g.

browser) -

Specifically need to be outside of your scripts (i.e. database passwords)

-

Do not change the results of your analysis.

Startup Sequence

Here is a simplified overview of what happens when R starts (type

help(Startup) to see the full details):

-

R executes the

Rprofile.sitescript. This is the site-level script that enables system administrators to override default options with localizations. The script’s full path isR_HOME\\/etc/Rprofile.site. (R_HOMEis the R home directory; see “Locating the R Home Directory”.)The R distribution does not include an

Rprofile.sitefile. Rather, the system administrator creates one if it is needed. -

R executes the

.Rprofilescript in the working directory; or, if that file does not exist, executes the.Rprofilescript in your home directory. This is the user’s opportunity to customize R for his or her purposes. The.Rprofilescript in the home directory is used for global customizations. The.Rprofilescript in a lower-level directory can perform specific customizations when R is started there; for instance, customizing R when started in a project-specific directory. -

R loads the workspace saved in

.RData, if that file exists in the working directory. R saves your workspace in the file called.RDatawhen it exits. It reloads your workspace from that file, restoring access to your local variables and functions. This can be disabled in R Studio throughTools→Global Options. We recommend you disable this and always explicitly save and load your work. -

R executes the`.First`function, if you defined one. The

.Firstfunction is a useful place for users or projects to define startup initialization code. You can define it in your.Rprofileor in your workspace. -

R executes the`.First.sys`function. This step loads the default packages. The function is internal to R and not normally changed by either users or administrators.

Observe that R does not load the default packages until the final step,

when it executes the .First.sys function. Before that, only the base

package has been loaded. This is a key fact because it means the

previous steps cannot assume that packages other than the base are

available. It also explains why trying to open a graphical window in

your .Rprofile script fails: the graphics packages aren’t loaded yet.

See Also

See “Accessing the Functions in a Package” for more about loading packages. See the R help

page for Startup (help(Startup)) and the R help page for options

(help(options)).

Installing R and R Studio in the Cloud

Problem

You want to run R and R Studio in a cloud environment.

Solution

The most straightforward way to use R in the cloud is to use the RStudio.cloud web service. To use the service, point your web browser to http://rstudio.cloud and set up an account, or log in with your Google or Github credentials.

Discussion

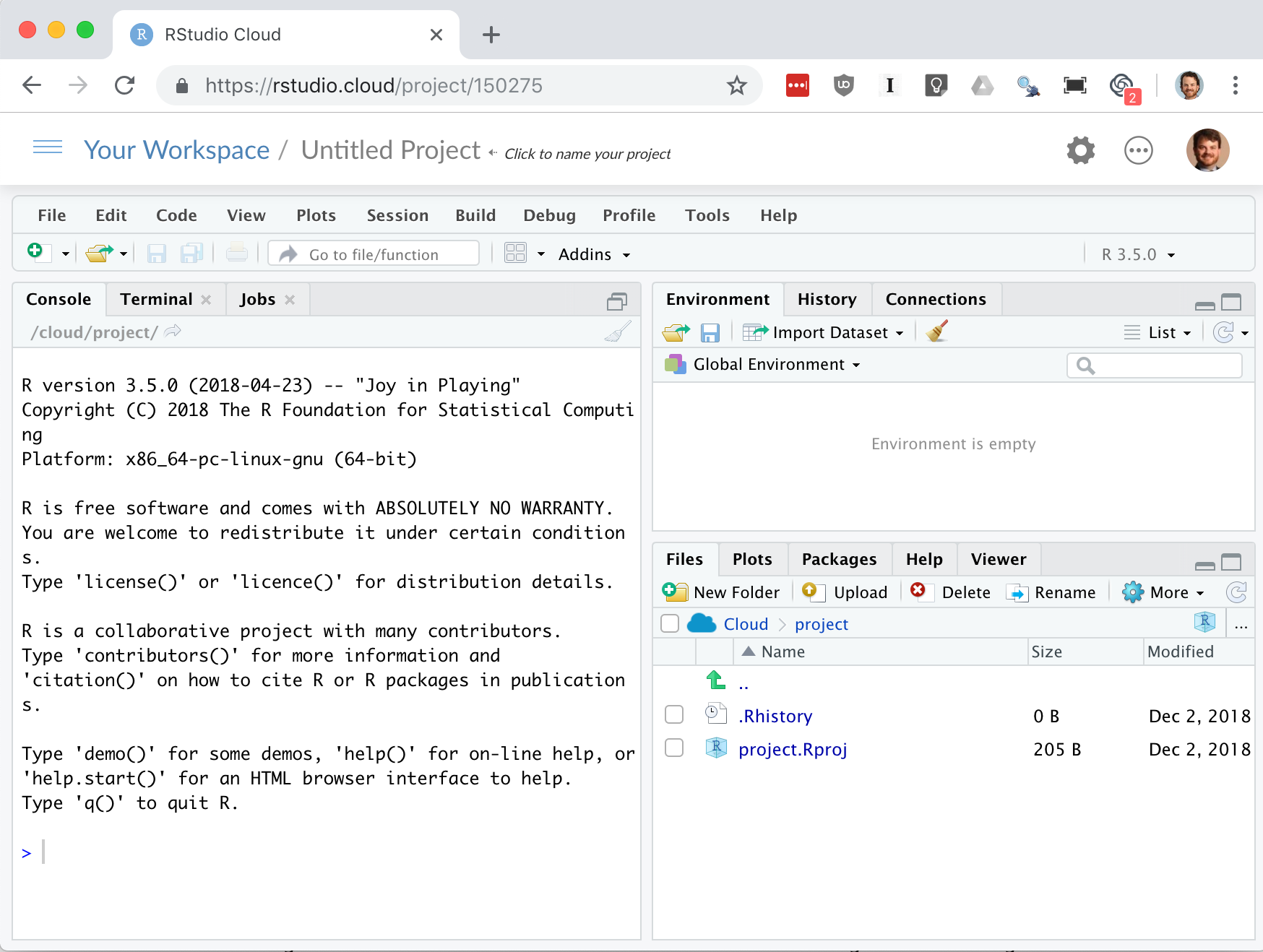

After you log in, click New Project to begin a new R Studio session in

a new workspace. You’ll be greeted by the familiar R Studio interface

shown in Figure 3-4.

Figure 3-4. rstudio.cloud

It’s worth keeping in mind that as of the writing of this book the RStudio.cloud service is in alpha testing and may not be 100% stable. Your work will persist after you log off. However, as with any system, it is a good idea to ensure you have backups of all the work you do. A common work pattern is to connect your project in RStudio.cloud to a GitHub.com repository and push your changes frequently from Rstudio.cloud to GitHub. This workflow has been used significantly in the writing of this book.

Use of git and GitHub are beyond the scope of this book, but if you

are interested in learning more, we highly recommend Jenny Bryan’s web

book Happy Git and GitHub for the useR http://happygitwithr.com/

In its current Alpha state, each RStudio.cloud session is limited to 1 GB of RAM and 3 GB of drive space. So it’s a great platform for learning and teaching but might not (yet) be the platform on which you want to build a commercial data science laboratory. R Studio has expressed intent to offer greater processing power and storage as part of a paid tier of service as the platform matures.

If you are needing more computing power than offered by RStudio.cloud and you are willing to pay for the services, both Amazon AWS and Google Cloud Platform offer cloud based R Studio offerings. Other cloud platforms that support Docker, such as Digital Ocean, are also reasonable options for cloud hosted R Studio.

See Also

Running R Studio Pro on Google Cloud Platform: https://console.cloud.google.com/marketplace/details/rstudio-launcher-public/rstudio-server-pro-for-gcp

Running R Studio Pro on Amazon Web Services: https://aws.amazon.com/marketplace/pp/B06W2G9PRY

How To Set Up RStudio On Digital Ocean: https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-set-up-rstudio-on-an-ubuntu-cloud-server