Second Edition

Proven Recipes for Data Analysis, Statistics, and Graphics

Copyright © 2019 J.D. Long and Paul Teetor. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492040682 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. R Cookbook, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-04068-2

This chapter sets the groundwork for the other chapters. It explains how to download, install, and run R.

More importantly, it also explains how to get answers to your questions. The R community provides a wealth of documentation and help. You are not alone. Here are some common sources of help:

When you install R on your computer, a mass of documentation is also installed. You can browse the local documentation (“Viewing the Supplied Documentation”) and search it (“Searching the Supplied Documentation”). We are amazed how often we search the Web for an answer only to discover it was already available in the installed documentation.

A task view describes packages that are specific to one area of statistical work, such as econometrics, medical imaging, psychometrics, or spatial statistics. Each task view is written and maintained by an expert in the field. There are more than 35 such task views, so there is likely to be one or more for your areas of interest. We recommend that every beginner find and read at least one task view in order to gain a sense of R’s possibilities (“Finding Relevant Functions and Packages”).

Most packages include useful documentation. Many also include overviews and tutorials, called “vignettes” in the R community. The documentation is kept with the packages in package repositories, such as CRAN (http://cran.r-project.org/), and it is automatically installed on your machine when you install a package.

On a Q&A site, anyone can post a question, and knowledgeable people can respond. Readers vote on the answers, so the best answers tend to emerge over time. All this information is tagged and archived for searching. These sites are a cross between a mailing list and a social network; “Stack Overflow” (http://stackoverflow.com/) is the canonical example.

The Web is loaded with information about R, and there are R-specific tools for searching it (“Searching the Web for Help”). The Web is a moving target, so be on the lookout for new, improved ways to organize and search information regarding R.

Volunteers have generously donated many hours of time to answer beginners’ questions that are posted to the R mailing lists. The lists are archived, so you can search the archives for answers to your questions (“Searching the Mailing Lists”).

You want to install R on your computer.

Windows and OS X users can download R from CRAN, the Comprehensive R Archive Network. Linux and Unix users can install R packages using their package management tool:

Windows

Open http://www.r-project.org/ in your browser.

Click on “CRAN”. You’ll see a list of mirror sites, organized by country.

Select a site near you or the top one listed as “0-Cloud” which tends to work well for most locations (https://cloud.r-project.org/)

Click on “Download R for Windows” under “Download and Install R”.

Click on “base”.

Click on the link for downloading the latest version of R (an .exe

file).

When the download completes, double-click on the .exe file and

answer the usual questions.

OS X

Open http://www.r-project.org/ in your browser.

Click on “CRAN”. You’ll see a list of mirror sites, organized by country.

Select a site near you or the top one listed as “0-Cloud” which tends to work well for most locations.

Click on “Download R for (Mac) OS X”.

Click on the .pkg file for the latest version of R, under “Latest

release:”, to download it.

When the download completes, double-click on the .pkg file and

answer the usual questions.

Linux or Unix

The major Linux distributions have packages for installing R. Here are some examples:

| Distribution | Package name |

|---|---|

Ubuntu or Debian |

r-base |

Red Hat or Fedora |

R.i386 |

Suse |

R-base |

Use the system’s package manager to download and install the package.

Normally, you will need the root password or sudo privileges;

otherwise, ask a system administrator to perform the installation.

Installing R on Windows or OS X is straightforward because there are prebuilt binaries (compiled programs) for those platforms. You need only follow the preceding instructions. The CRAN Web pages also contain links to installation-related resources, such as frequently asked questions (FAQs) and tips for special situations (“Does R run under Windows Vista/7/8/Server 2008?”) that you may find useful.

The best way to install R on Linux or Unix is by using your Linux distribution package manager to install R as a package. The distribution packages greatly streamline both the initial installation and subsequent updates.

On Ubuntu or Debian, use apt-get to download and install R. Run under

sudo to have the necessary privileges:

$sudoapt-getinstallr-base

On Red Hat or Fedora, use yum:

$sudoyuminstallR.i386

Most Linux platforms also have graphical package managers, which you might find more convenient.

Beyond the base packages, we recommend installing the documentation

packages, too. We like to install r-base-html (because we like

browsing the hyperlinked documentation) as well as r-doc-html, which

installs the important R manuals locally:

$sudoapt-getinstallr-base-htmlr-doc-html

Some Linux repositories also include prebuilt copies of R packages available on CRAN. We don’t use them because we’d rather get software directly from CRAN itself, which usually has the freshest versions.

In rare cases, you may need to build R from scratch. You might have an

obscure, unsupported version of Unix; or you might have special

considerations regarding performance or configuration. The build

procedure on Linux or Unix is quite standard. Download the tarball from

the home page of your CRAN mirror; it’s called something like

R-3.5.1.tar.gz, except the “3.5.1” will be replaced by the latest

version. Unpack the tarball, look for a file called INSTALL, and

follow the directions.

R in a Nutshell (http://oreilly.com/catalog/9780596801717) (O’Reilly) contains more details of downloading and installing R, including instructions for building the Windows and OS X versions. Perhaps the ultimate guide is the one entitled “R Installation and Administration” (http://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/R-admin.html), available on CRAN, which describes building and installing R on a variety of platforms.

This recipe is about installing the base package. See “Installing Packages from CRAN” for installing add-on packages from CRAN.

You want a more comprehensive Integrated Development Environment (IDE) than the R default. In other words, you want to install R Studio Desktop.

Over the past few years R Studio has become the most widly used IDE for

R. We are of the opinion that most all R work should be done in the R

Studio Desktop IDE unless there is a compelling reason to do otherwise.

R Studio makes multiple products including R Studio Desktop, R Studio

Server, R Studio Shiny Server, just to name a few. For this book we will

use the term R Studio to mean R Studio Desktop though most concepts

apply to R Studio Server as well.

To install R Studio, download the latest installer for your platform from the R Studio website: https://www.rstudio.com/products/rstudio/download/

The R Studio Desktop Open Source License version is free to download and use.

This book was written and built using R Studio version 1.2.x and R versions 3.5.x. New versions of R Studio are released every few months, so be sure and update regularly. Note that R Studio works with whichever version of R you have installed. So updating to the latest version of R Studio does not upgrade your version of R. R must be upgraded seperatly.

Interacting with R is slightly different in R Studio than in the built in R user interface. For this book, we’ve elected to use R Studio for all examples.

You want to run R Studio on your computer.

A common point of confusion for new users of R and R Studio is to

accidentally start R when they intended to start R Studio. The easiest

way to ensure you’re actually starting R Studio is to search for

RStudio on your desktop OS. Then use whatever method your OS provides

for pinning the icon somewhere easy to find later.

Click on the Start Screen menue in the lower left corner of the

screen. In the search box, type RStudio.

Look in your launchpad for the R Studio app or press command

space and type Rstudio to search using Spotlight Search.

Press Alt + F1 and type RStudio to search for R Studio.

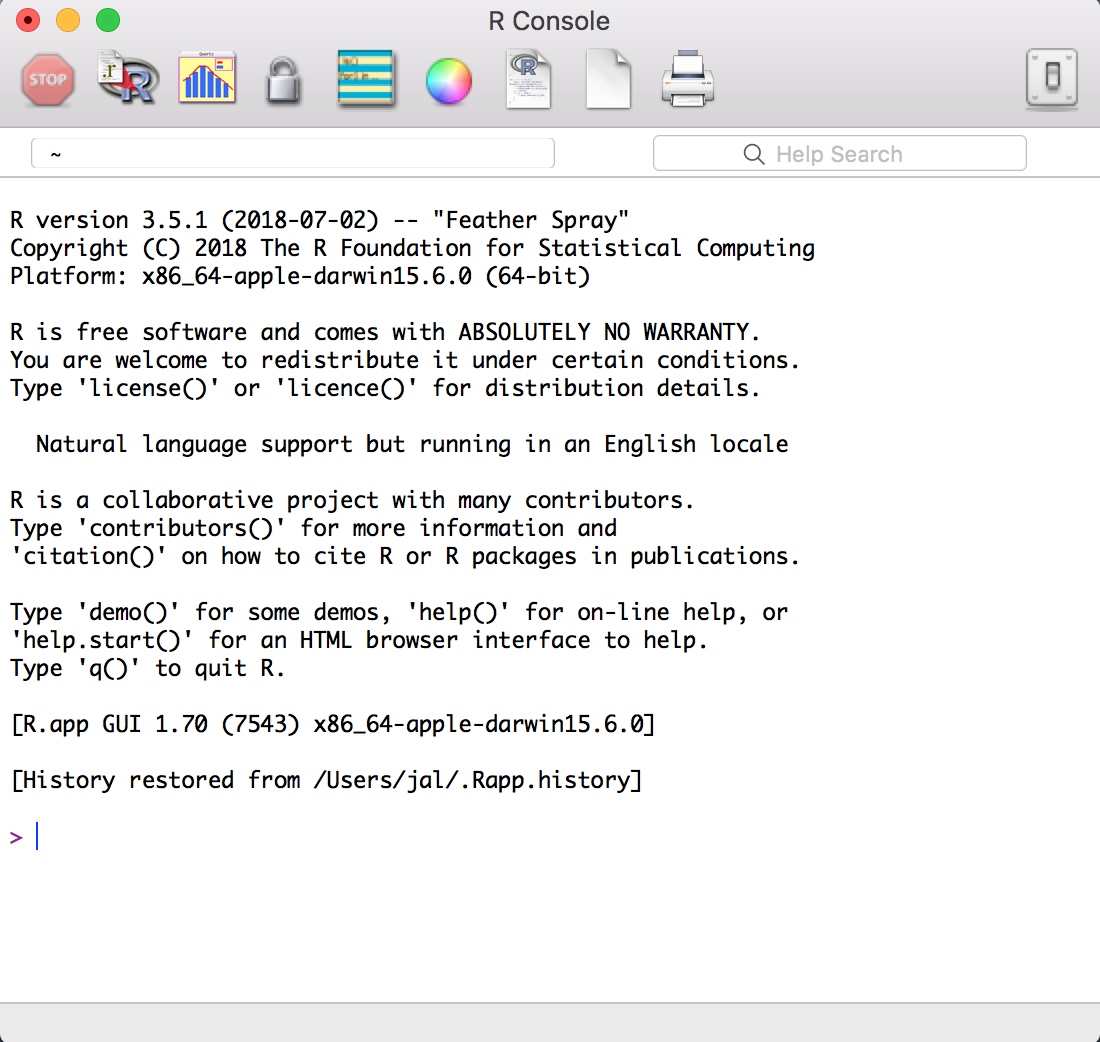

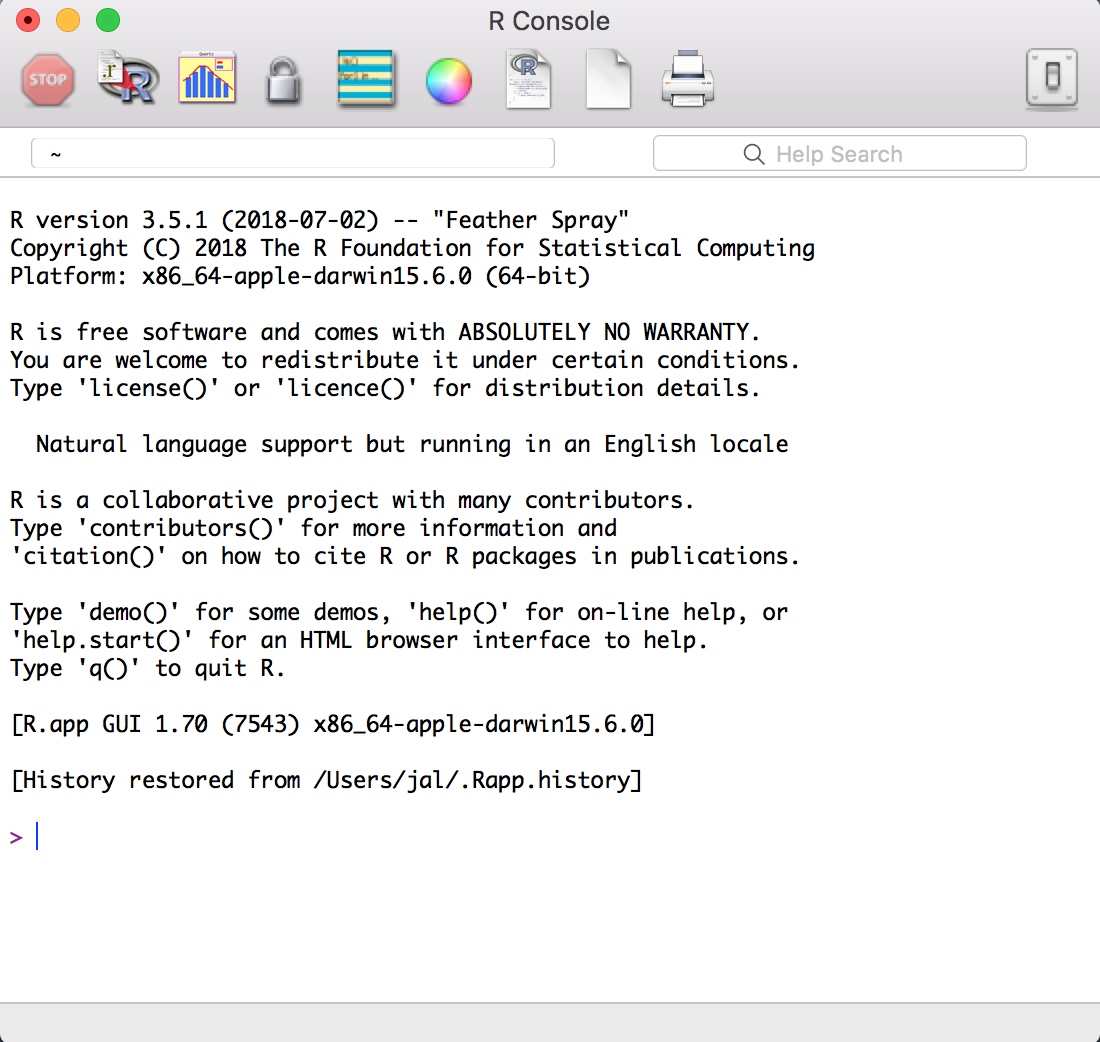

Confusion between R and R Studio can easily happen becuase as you can see in Figure 1-1, the icons look similiar.

If you click on the R icon you’ll be greeted by something like Figure

Figure 1-2 which is the Base R interface on a Mac, but certainly

not R Studio.

When you start R Studio, the default behavior is that R Studio will reopen the last project you were working on in R Studio.

You’ve started R Studio. Now what?

When you start R Studio, the main window on the left is an R session. From there you can enter commands interactivly directly to R.

R prompts you with “>”. To get started, just treat R like a big

calculator: enter an expression, and R will evaluate the expression and

print the result:

1+1#> [1] 2

The computer adds one and one, giving two, and displays the result.

The [1] before the 2 might be confusing. To R, the result is a

vector, even though it has only one element. R labels the value with

[1] to signify that this is the first element of the vector… which

is not surprising, since it’s the only element of the vector.

R will prompt you for input until you type a complete expression. The

expression max(1,3,5) is a complete expression, so R stops reading

input and evaluates what it’s got:

max(1,3,5)#> [1] 5

In contrast, “max(1,3,” is an incomplete expression, so R prompts you

for more input. The prompt changes from greater-than (>) to plus

(+), letting you know that R expects more:

max(1,3,+5)#> [1] 5

It’s easy to mistype commands, and retyping them is tedious and frustrating. So R includes command-line editing to make life easier. It defines single keystrokes that let you easily recall, correct, and reexecute your commands. My own typical command-line interaction goes like this:

I enter an R expression with a typo.

R complains about my mistake.

I press the up-arrow key to recall my mistaken line.

I use the left and right arrow keys to move the cursor back to the error.

I use the Delete key to delete the offending characters.

I type the corrected characters, which inserts them into the command line.

I press Enter to reexecute the corrected command.

That’s just the basics. R supports the usual keystrokes for recalling and editing command lines, as listed in table @ref(tab:keystrokes).

| Labeled key | Ctrl-key combination | Effect |

|---|---|---|

Up arrow |

Ctrl-P |

Recall previous command by moving backward through the history of commands. |

Down arrow |

Ctrl-N |

Move forward through the history of commands. |

Backspace |

Ctrl-H |

Delete the character to the left of cursor. |

Delete (Del) |

Ctrl-D |

Delete the character to the right of cursor. |

Home |

Ctrl-A |

Move cursor to the start of the line. |

End |

Ctrl-E |

Move cursor to the end of the line. |

Right arrow |

Ctrl-F |

Move cursor right (forward) one character. |

Left arrow |

Ctrl-B |

Move cursor left (back) one character. |

Ctrl-K |

Delete everything from the cursor position to the end of the line. |

|

Ctrl-U |

Clear the whole darn line and start over. |

|

Tab |

Name completion (on some platforms). |

: Keystrokes for command-line editing

On Windows and OS X, you can also use the mouse to highlight commands and then use the usual copy and paste commands to paste text into a new command line.

See “Typing Less and Accomplishing More”. From the Windows main menu, follow Help →

Console for a complete list of keystrokes useful for command-line

editing.

You want to exit from R Studio.

Select File → Quit Session from the main menu; or click on the X

in the upper-right corner of the window frame.

Press CMD-q (apple-q); or click on the red X in the upper-left corner of the window frame.

At the command prompt, press Ctrl-D.

On all platforms, you can also use the q function (as in _q_uit) to

terminate the program.

q()

Note the empty parentheses, which are necessary to call the function.

Whenever you exit, R typically asks if you want to save your workspace. You have three choices:

Save your workspace and exit.

Don’t save your workspace, but exit anyway.

Cancel, returning to the command prompt rather than exiting.

If you save your workspace, then R writes it to a file called .RData

in the current working directory. Savign the workspace saves any R

objects which you have created. Next time you start R in the same

directory the workspace will automatically load. Saving your workspace

will overwrite the previously saved workspace, if any, so don’t save if

you don’t like the changes to your workspace (e.g., if you have

accidentally erased critical data).

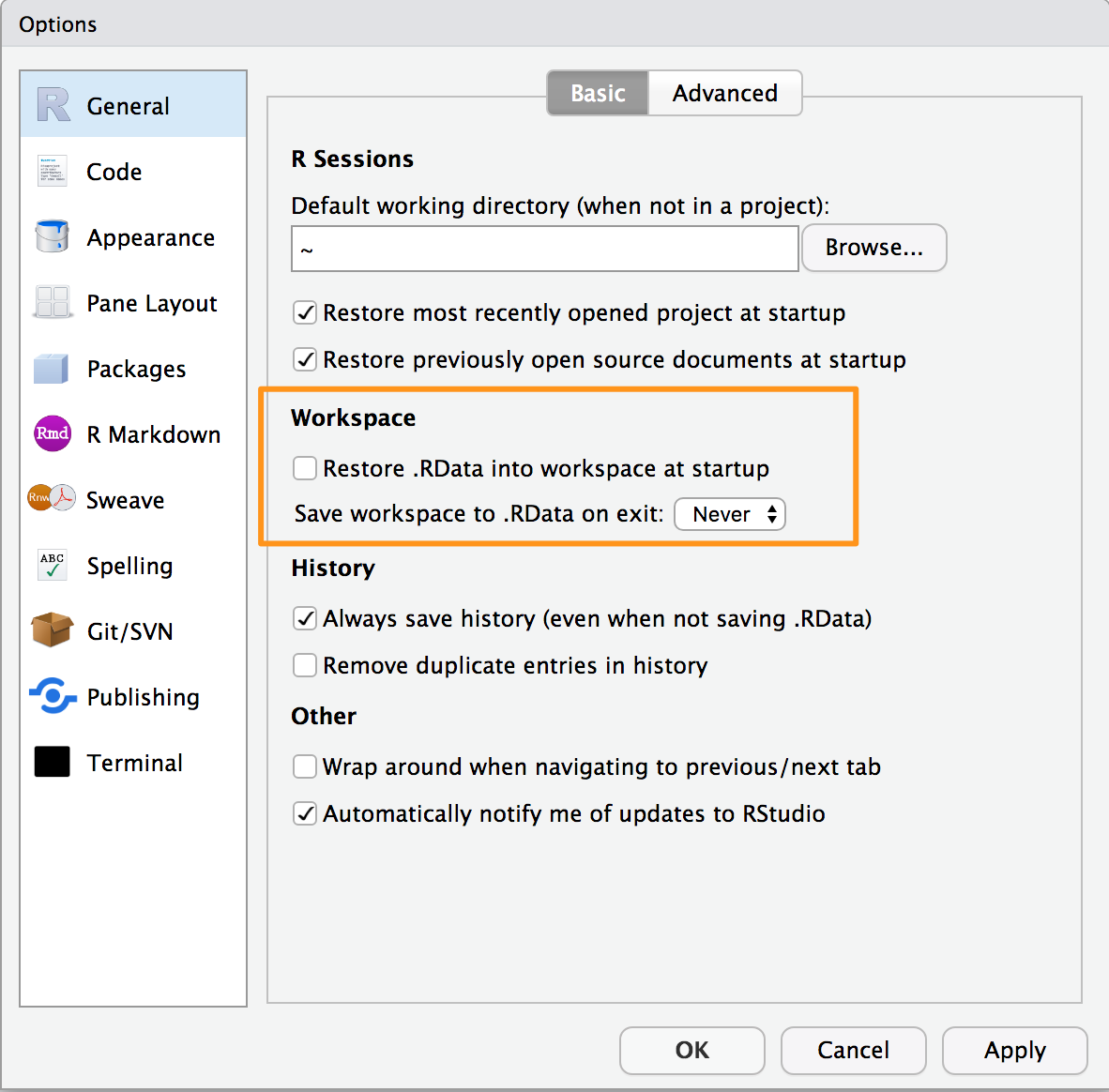

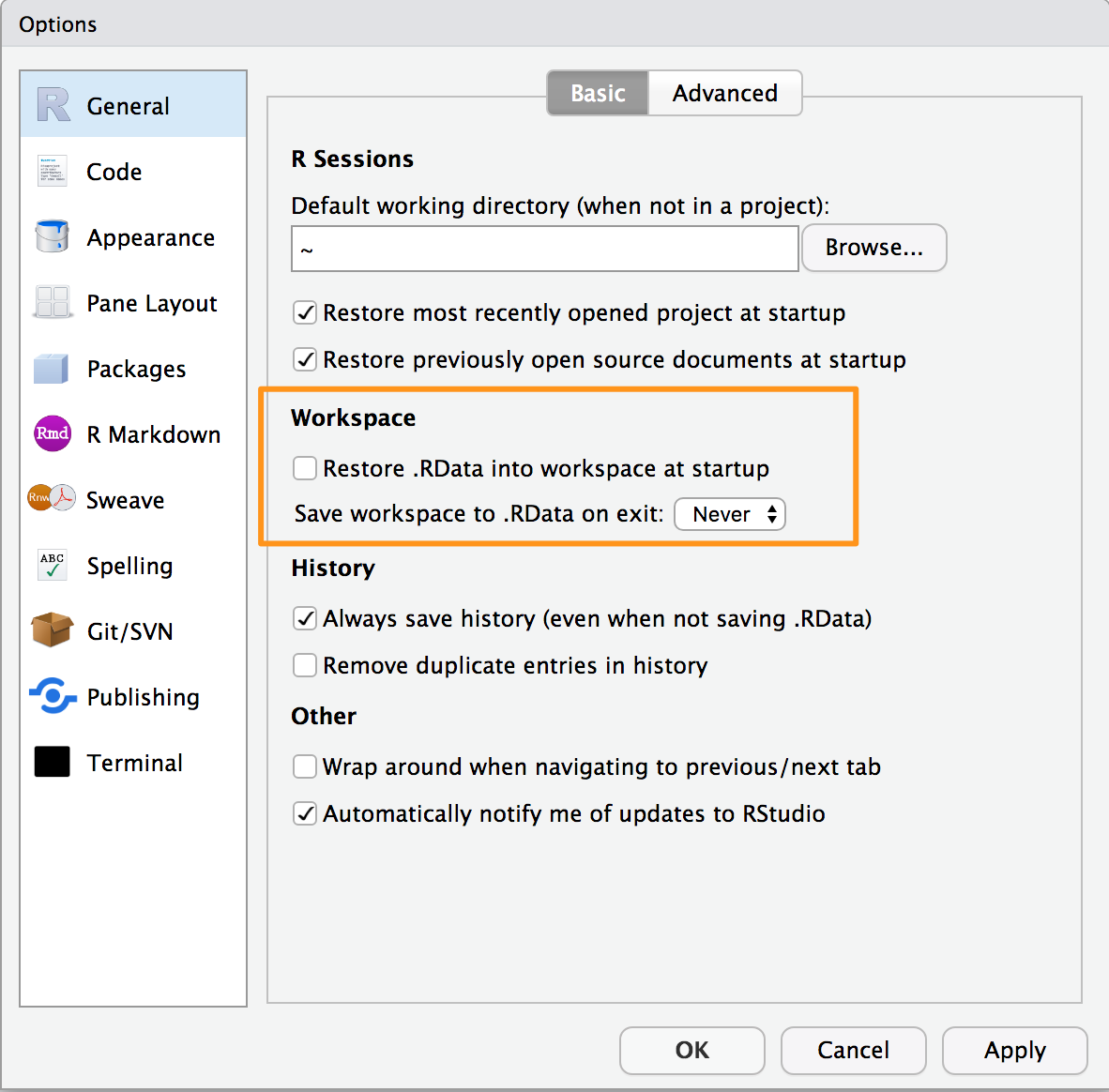

We recommend never saving your workspace when you exit, and instead

always explicitly saving your project, scripts, and data. We also

recommend that you turn off the prompt to save and auto restore of

workspace in R Studio using the Global Options found in the menu Tools

→ Global Options and shown in Figure 1-3. This way

when you exit R and R Studio you will not be prompted to save your

workspace. But keep in mind that any objects created but not saved to

disk will be lost.

See “Getting and Setting the Working Directory” for more about the current working directory and “Saving Your Workspace” for more about saving your workspace. See Chapter 2 of R in a Nutshell (http://oreilly.com/catalog/9780596801717).

You want to interrupt a long-running computation and return to the command prompt without exiting R Studio.

Press the Esc key on your keyboard, or click on the Session Menu in

R Studio and select Interrupt R

Interrupting R means telling R to stop running the current command but without deleting variables from memory or completly closing R Studio. Although, interrupting R can leave your variables in an indeterminate state, depending upon how far the computation had progressed. Check your workspace after interrupting.

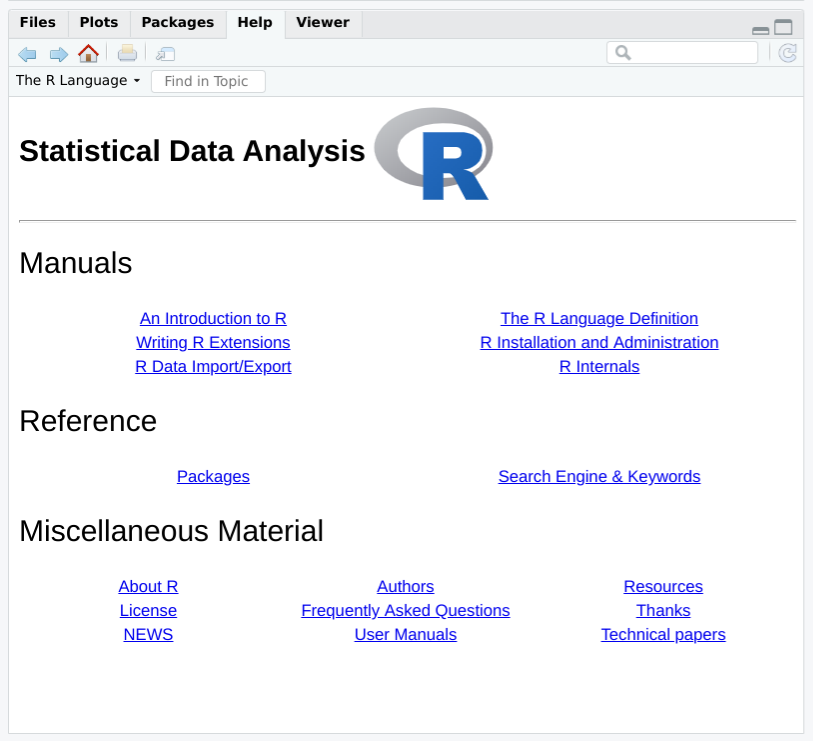

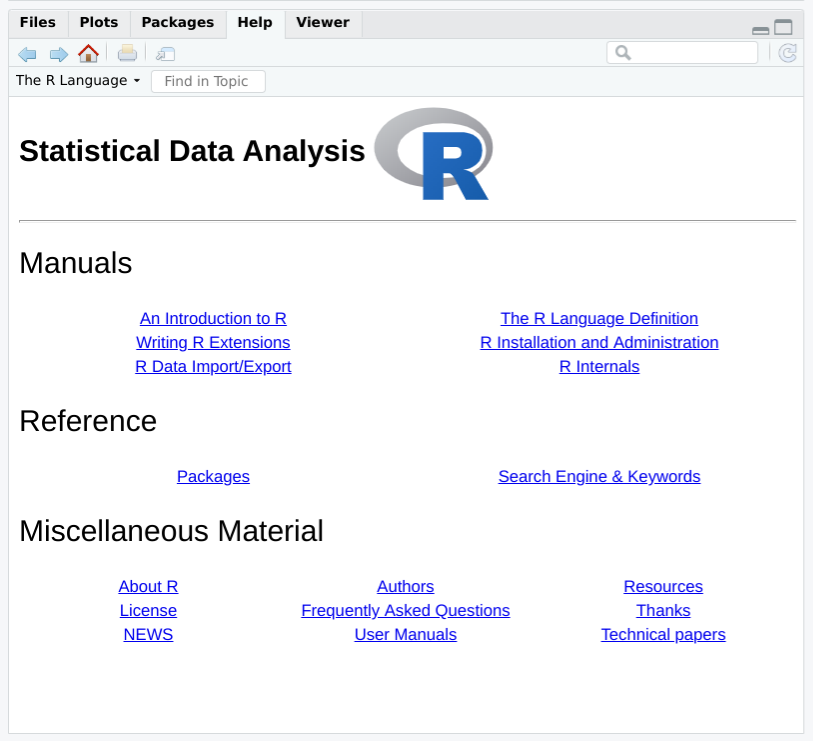

You want to read the documentation supplied with R.

Use the help.start function to see the documentation’s table of

contents:

help.start()

From there, links are available to all the installed documentation. In R Studio the help will show up in the help pane which by default is on the right hand side of the screen.

In R Studio you can also click help → R Help to get a listng with

help options for both R and R Studio.

The base distribution of R includes a wealth of documentation—literally thousands of pages. When you install additional packages, those packages contain documentation that is also installed on your machine.

It is easy to browse this documentation via the help.start function,

which opens on the top-level table of contents. Figure

Figure 1-4 shows how help.start() appears inside the help

pane in R Studio.

The two links in the Base R Reference section are especially useful:

Click here to see a list of all the installed packages, both in the base packages and the additional, installed packages. Click on a package name to see a list of its functions and datasets.

Click here to access a simple search engine, which allows you to search the documentation by keyword or phrase. There is also a list of common keywords, organized by topic; click one to see the associated pages.

The Base R documentation shown by typing help.start() is loaded on

your computer when you install R. The R Studio help which you get by

using the menu option help → R Help presents a page with links to R

Studio’s web site. So you will need Internet access to access the R

Studio help links.

The local documentation is copied from the R Project website, which may have updated documents.

You want to know more about a function that is installed on your machine.

Use help to display the documentation for the function:

help(functionname)

Use args for a quick reminder of the function arguments:

args(functionname)

Use example to see examples of using the function:

example(functionname)

We present many R functions in this book. Every R function has more bells and whistles than we can possibly describe. If a function catches your interest, we strongly suggest reading the help page for that function. One of its bells or whistles might be very useful to you.

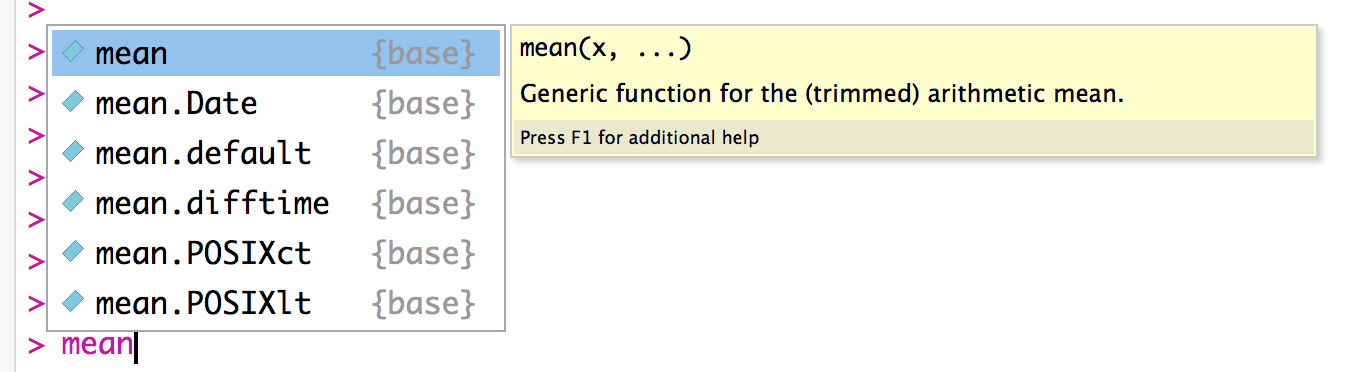

Suppose you want to know more about the mean function. Use the help

function like this:

help(mean)

This will open the help page for the mean function in the help pane in R

Studio. A shortcut for the help command is to simply type ? followed

by the function name:

?mean

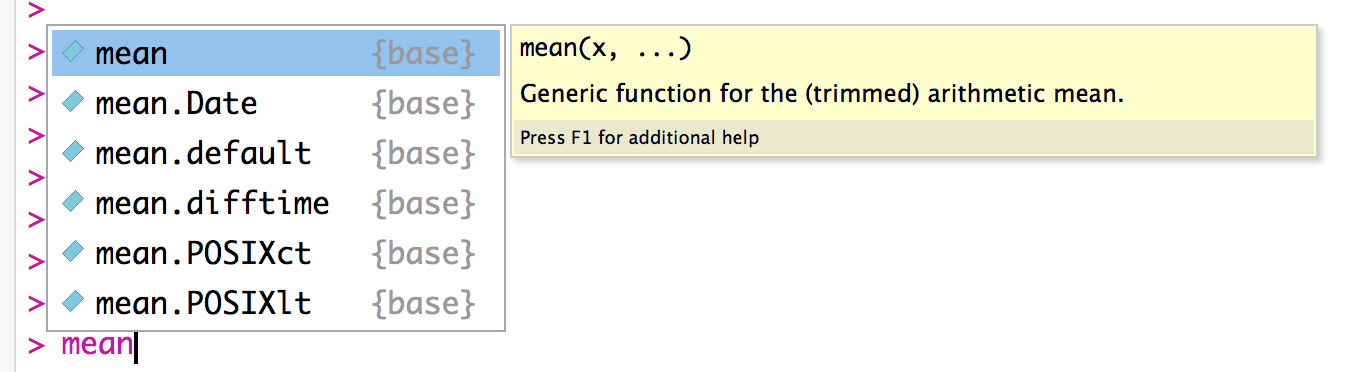

Sometimes you just want a quick reminder of the arguments to a function:

What are they, and in what order do they occur? Use the args function:

args(mean)#> function (x, ...)#> NULL

args(sd)#> function (x, na.rm = FALSE)#> NULL

The first line of output from args is a synopsis of the function call.

For mean, the synopsis shows one argument, x, which is a vector of

numbers. For sd, the synopsis shows the same vector, x, and an

optional argument called na.rm. (You can ignore the second line of

output, which is often just NULL.) In R Studio you will see the args

output as a floating tool tip over your cursor when you type a function

name as shown in figure Figure 1-5.

Most documentation for functions includes example code near the end of

the document. A cool feature of R is that you can request that it

execute the examples, giving you a little demonstration of the

function’s capabilities. The documentation for the mean function, for

instance, contains examples, but you don’t need to type them yourself.

Just use the example function to watch them run:

example(mean)#>#> mean> x <- c(0:10, 50)#>#> mean> xm <- mean(x)#>#> mean> c(xm, mean(x, trim = 0.10))#> [1] 8.75 5.50

The user typed example(mean). Everything else was produced by R, which

executed the examples from the help page and displayed the results.

See “Searching the Supplied Documentation” for searching for functions and “Displaying Loaded Packages via the Search Path” for more about the search path.

You want to know more about a function that is installed on your

machine, but the help function reports that it cannot find

documentation for any such function.

Alternatively, you want to search the installed documentation for a keyword.

Use help.search to search the R documentation on your computer:

help.search("pattern")

A typical pattern is a function name or keyword. Notice that it must be enclosed in quotation marks.

For your convenience, you can also invoke a search by using two question marks (in which case the quotes are not required). Note that searching for a function by name uses one question mark while searching for a text pattern uses two:

>??pattern

You may occasionally request help on a function only to be told R knows nothing about it:

help(adf.test)#> No documentation for 'adf.test' in specified packages and libraries:#> you could try '??adf.test'

This can be frustrating if you know the function is installed on your machine. Here the problem is that the function’s package is not currently loaded, and you don’t know which package contains the function. It’s a kind of catch-22 (the error message indicates the package is not currently in your search path, so R cannot find the help file; see “Displaying Loaded Packages via the Search Path” for more details).

The solution is to search all your installed packages for the function.

Just use the help.search function, as suggested in the error message:

help.search("adf.test")

The search will produce a listing of all packages that contain the function:

Helpfileswithaliasorconceptortitlematching'adf.test'usingregularexpressionmatching:tseries::adf.testAugmentedDickey-FullerTestType'?PKG::FOO'toinspectentry'PKG::FOO TITLE'.

The output above indicates that the tseries package contains the

adf.test function. You can see its documentation by explicitly telling

help which package contains the function:

help(adf.test,package="tseries")

or you can use the double colon operator to tell R to look in a specific package:

?tseries::adf.test

You can broaden your search by using keywords. R will then find any installed documentation that contains the keywords. Suppose you want to find all functions that mention the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. You could search on a likely pattern:

help.search("dickey-fuller")

On my machine, the result looks like this because I’ve installed two

additional packages (fUnitRoots and urca) that implement the ADF

test:

Helpfileswithaliasorconceptortitlematching'dickey-fuller'usingfuzzymatching:fUnitRoots::DickeyFullerPValuesDickey-FullerpValuestseries::adf.testAugmentedDickey-FullerTesturca::ur.dfAugmented-Dickey-FullerUnitRootTestType'?PKG::FOO'toinspectentry'PKG::FOO TITLE'.

You can also access the local search engine through the documentation browser; see “Viewing the Supplied Documentation” for how this is done. See “Displaying Loaded Packages via the Search Path” for more about the search path and “Listing Files” for getting help on functions.

You want to learn more about a package installed on your computer.

Use the help function and specify a package name (without a function

name):

help(package="packagename")

Sometimes you want to know the contents of a package (the functions and datasets). This is especially true after you download and install a new package, for example. The help function can provide the contents plus other information once you specify the package name.

This call to help will display the information for the tseries

package, a standard package in the base distribution:

help(package="tseries")

The information begins with a description and continues with an index of functions and datasets. In R Studio, the HTML formatted help page will open in the help window of the IDE.

Some packages also include vignettes, which are additional documents such as introductions, tutorials, or reference cards. They are installed on your computer as part of the package documentation when you install the package. The help page for a package includes a list of its vignettes near the bottom.

You can see a list of all vignettes on your computer by using the

vignette function:

vignette()

In R Studio this will open a new tab and list every package installed on your computer which includes vignettes and a list of vignette names and descriptions.

You can see the vignettes for a particular package by including its name:

vignette(package="packagename")

Each vignette has a name, which you use to view the vignette:

vignette("vignettename")

See “Getting Help on a Function” for getting help on a particular function in a package.

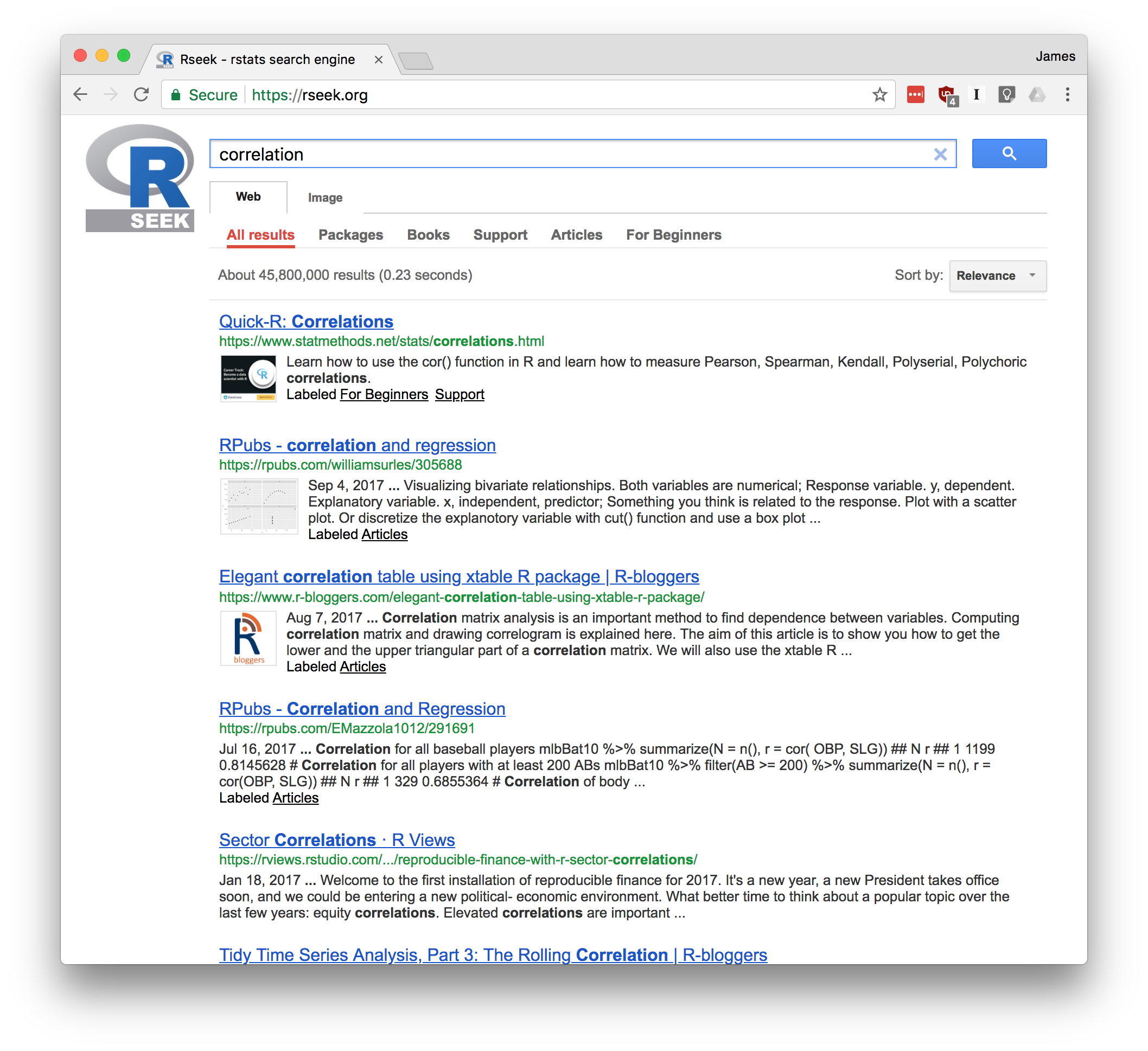

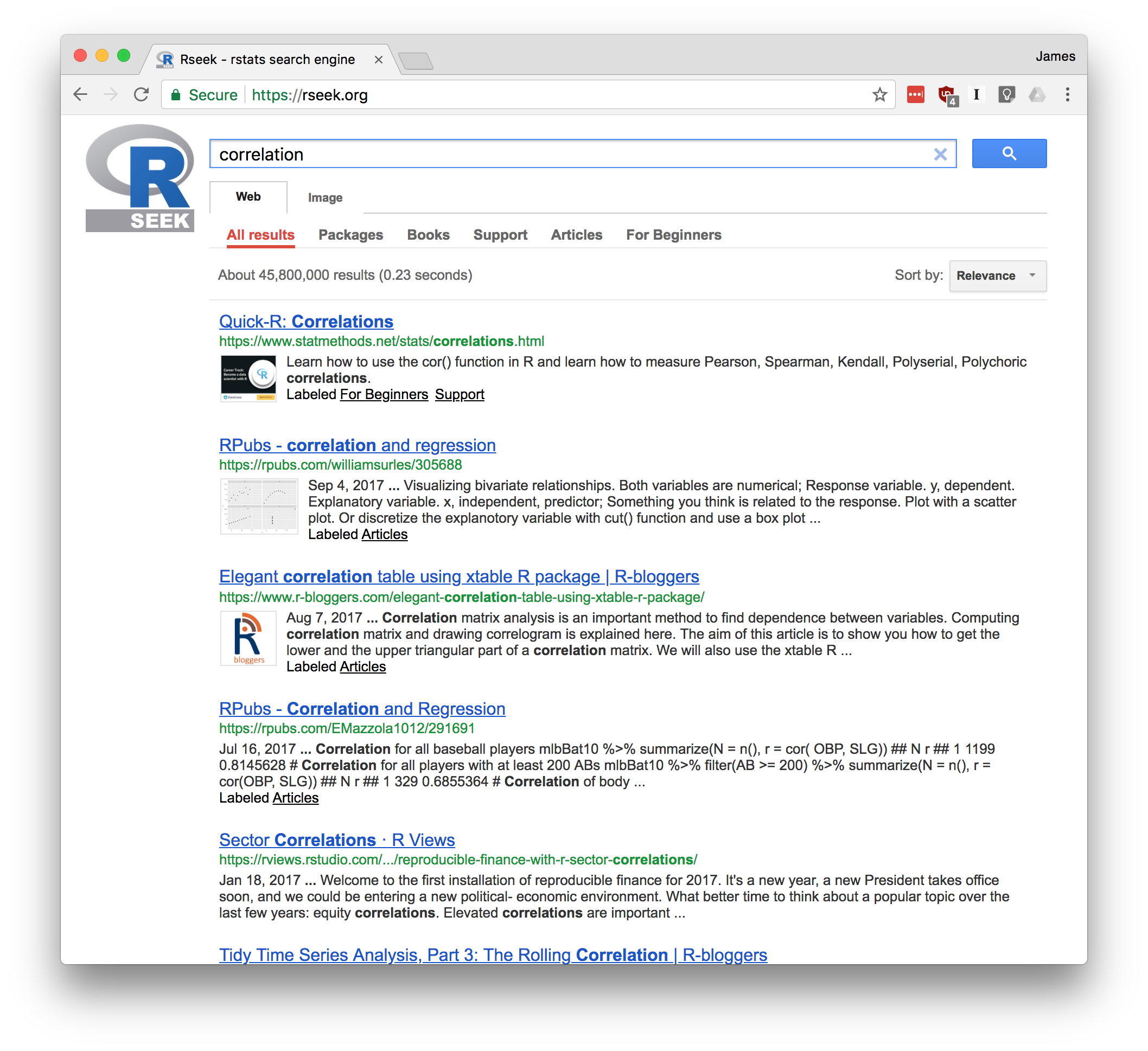

You want to search the Web for information and answers regarding R.

Inside R, use the RSiteSearch function to search by keyword or phrase:

RSiteSearch("key phrase")

Inside your browser, try using these sites for searching:

This is a Google custom search that is focused on R-specific websites.

Stack Overflow is a searchable Q&A site from Stack Exchange oriented toward programming issues such as data structures, coding, and graphics. http://stats.stackexchange.com/[Cross Validated:

Cross Validated is a Stack Exchange site focused on statistics, machine learning, and data analysis rather than programming. Cross Validated is a good place for questions about what statistical method to use.

The RSiteSearch function will open a browser window and direct it to

the search engine on the R Project website

(http://search.r-project.org/). There you will see an initial search

that you can refine. For example, this call would start a search for

“canonical correlation”:

RSiteSearch("canonical correlation")

This is quite handy for doing quick web searches without leaving R. However, the search scope is limited to R documentation and the mailing-list archives.

The rseek.org site provides a wider search. Its virtue is that it harnesses the power of the Google search engine while focusing on sites relevant to R. That eliminates the extraneous results of a generic Google search. The beauty of rseek.org is that it organizes the results in a useful way.

Figure Figure 1-6 shows the results of visiting rseek.org and searching for “canonical correlation”. The left side of the page shows general results for search R sites. The right side is a tabbed display that organizes the search results into several categories:

Introductions

Task Views

Support Lists

Functions

Books

Blogs

Related Tools

If you click on the Introductions tab, for example, you’ll find tutorial material. The Task Views tab will show any Task View that mentions your search term. Likewise, clicking on Functions will show links to relevant R functions. This is a good way to zero in on search results.

Stack Overflow (http://stackoverflow.com/) is a Q&A site, which means that anyone can submit a question and experienced users will supply answers—often there are multiple answers to each question. Readers vote on the answers, so good answers tend to rise to the top. This creates a rich database of Q&A dialogs, which you can search. Stack Overflow is strongly problem oriented, and the topics lean toward the programming side of R.

Stack Overflow hosts questions for many programming languages;

therefore, when entering a term into their search box, prefix it with

[r] to focus the search on questions tagged for R. For example,

searching via [r] standard error will select only the questions tagged

for R and will avoid the Python and C++ questions.

Stack Overflow also includes a wiki about the R language that is an excellent community curreated list of online R resources: https://stackoverflow.com/tags/r/info

Stack Exchange (parent company of Stack Overflow) has a Q&A area for statistical analysis called Cross Validated: https://stats.stackexchange.com/. This area is more focused on statistics than programming, so use this site when seeking answers that are more concerned with statistics in general and less with R in particular.

If your search reveals a useful package, use “Installing Packages from CRAN” to install it on your machine.

Of the 10,000+ packages for R, you have no idea which ones would be useful to you.

Visit the list of task views at http://cran.r-project.org/web/views/ Find and read the task view for your area, which will give you links to and descriptions of relevant packages. Or visit http://rseek.org, search by keyword, click on the Task Views tab, and select an applicable task view.

Visit crantastic (http://crantastic.org/) and search for packages by keyword.

To find relevant functions, visit http://rseek.org, search by name or keyword, and click on the Functions tab.

To discover packages related to a certain field, explore CRAN Task Views (https://cran.r-project.org/web/views/).

This problem is especially vexing for beginners. You think R can solve your problems, but you have no idea which packages and functions would be useful. A common question on the mailing lists is: “Is there a package to solve problem X?” That is the silent scream of someone drowning in R.

As of this writing, there are more than 10,000 packages available for free download from CRAN. Each package has a summary page with a short description and links to the package documentation. Once you’ve located a potentially interesting package, you would typically click on the “Reference manual” link to view the PDF documentation with full details. (The summary page also contains download links for installing the package, but you’ll rarely install the package that way; see “Installing Packages from CRAN”.)

Sometimes you simply have a generic interest—such as Bayesian analysis, econometrics, optimization, or graphics. CRAN contains a set of task view pages describing packages that may be useful. A task view is a great place to start since you get an overview of what’s available. You can see the list of task view pages at CRAN Task Views (http://cran.r-project.org/web/views/) or search for them as described in the Solution. Task Views on CRAN list a number of broad fields and show packages that are used in each field. For example, there are Task Views for high performance computing, genetics, time series, and social science, just to name a few.

Suppose you happen to know the name of a useful package—say, by seeing it mentioned online. A complete, alphabetical list of packages is available at CRAN (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/) with links to the package summary pages.

You can download and install an R package called sos that provides

powerful other ways to search for packages; see the vignette at

SOS

(http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sos/vignettes/sos.pdf).

You have a question, and you want to search the archives of the mailing lists to see whether your question was answered previously.

Open Nabble (http://r.789695.n4.nabble.com/) in your browser. Search for a keyword or other search term from your question. This will show results from the support mailing lists.

This recipe is really just an application of “Searching the Web for Help”. But it’s an important application because you should search the mailing list archives before submitting a new question to the list. Your question has probably been answered before.

CRAN has a list of additional resources for searching the Web; see CRAN Search (http://cran.r-project.org/search.html).

You have a question you can’t find the answer to online. So you want to submit a question to the R community.

The first step to asking a question online is to create a reproducable example. Having example code that someone can run and see exactly your problem is to most critical part of asking for help online. A question with a good reproducable example has three componenets:

Example Data - This can be simulated data or some real data that you provide

Example Code - This code shows what you have tried or an error you are having

Written Description - This is where you explain what you have, what you’d like to have and what you have tried that didn’t work.

The details of writing a reproducable example are below in the

discussion. Once you have a reproducable example, you can post your

quesion on Stack Overflow via https://stackoverflow.com/questions/ask.

Be sure and include the r tag in the Tags section of the ask page.

Or if your discussion is more general or related to concepts instead of specific syntax, R Studio runs an R Studio Community discussion forum at https://community.rstudio.com/. Note that the site is broken into multiple topics, so pick the topic category that best fits your question.

Or you may submit your question to the R Mailing lists (but don’t submit to multiple sites, the mailing lists, and Stack Overflow as that’s considered rude cross posting):

The Mailing Lists (http://www.r-project.org/mail.html) page contains general information and instructions for using the R-help mailing list. Here is the general process:

Subscribe to the R-help list at the “Main R Mailing List” (https://stat.ethz.ch/mailman/listinfo/r-help).

Write your question carefully and correctly and include your reproducable example.

Mail your question to r-help@r-project.org.

The R mailing list, Stack Overflow, and the R Studio Community site are great resources, but please treat them as a last resort. Read the help pages, read the documentation, search the help list archives, and search the Web. It is most likely that your question has already been answered. Don’t kid yourself: very few questions are unique. If you’ve exhausted all other options, maybe it’s time to create a good question.

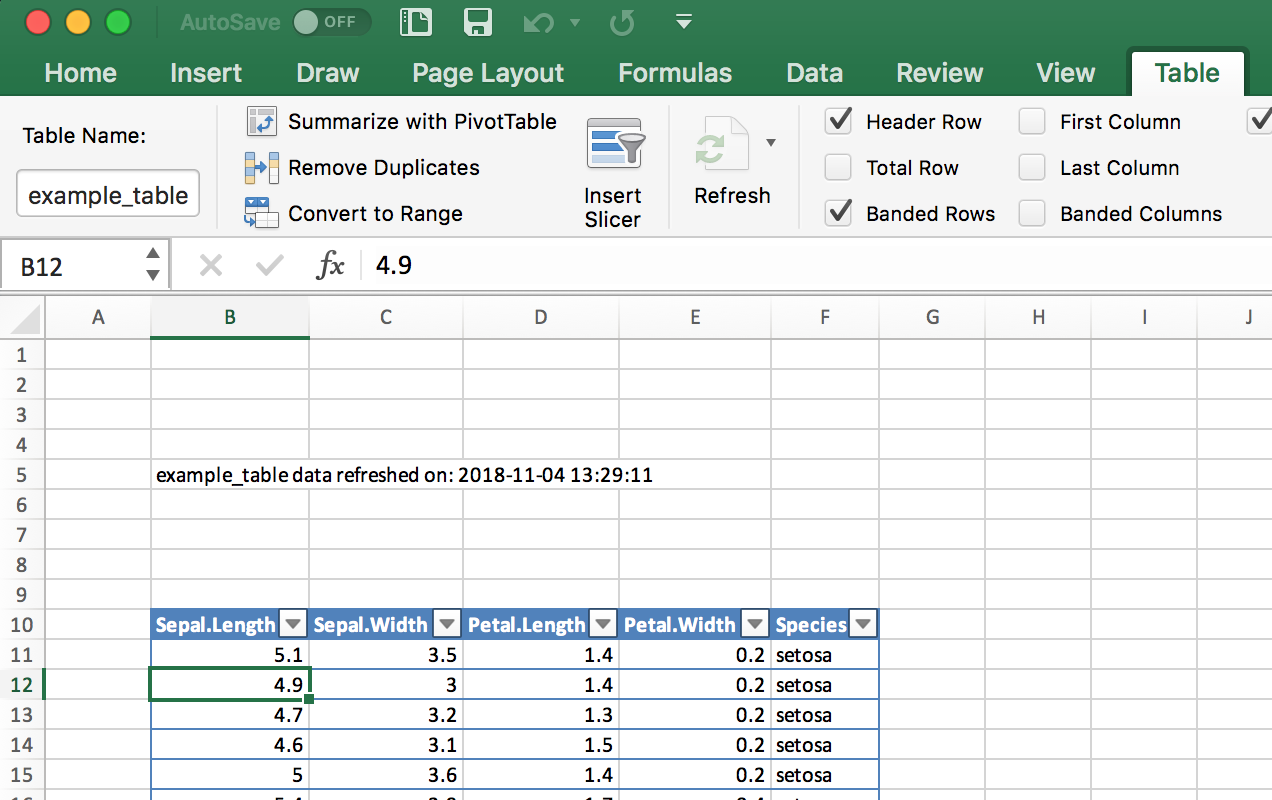

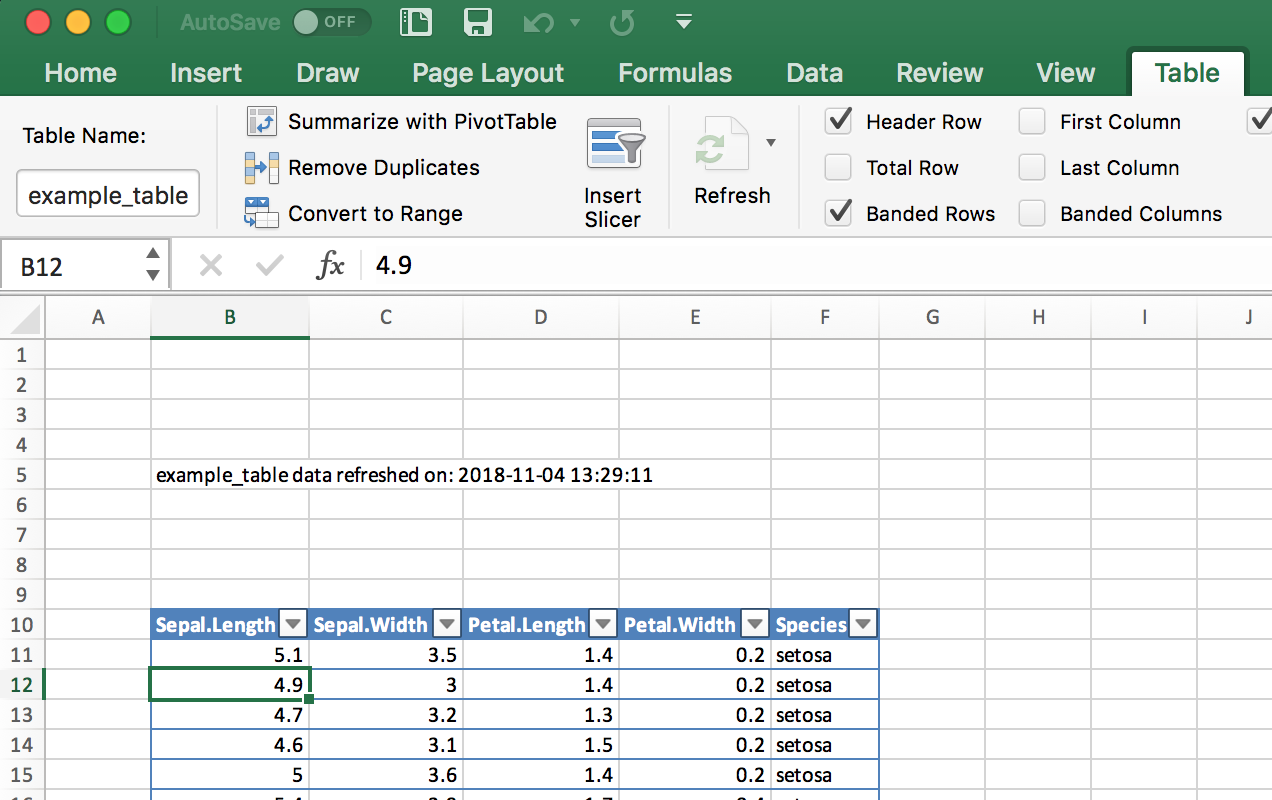

The reproducable example is the crux of a good help reqeust. The first

step is example data. A good way to get example data is to simulate the

data using a few R functions. The following example creates a data frame

called example_df that has three columns, each of a different data

type:

set.seed(42)n<-4example_df<-data.frame(some_reals=rnorm(n),some_letters=sample(LETTERS,n,replace=TRUE),some_ints=sample(1:10,n,replace=TRUE))example_df#> some_reals some_letters some_ints#> 1 1.371 R 10#> 2 -0.565 S 3#> 3 0.363 L 5#> 4 0.633 S 10

Note that this example uses the command set.seed() at the beginning.

This ensures that every time this code is run the answers will be the

same. The n value is the number of rows of example data you would like

to create. Make your example data as simple as possible to illustrate

your question.

An alternative to creating simulated data is to use example data that

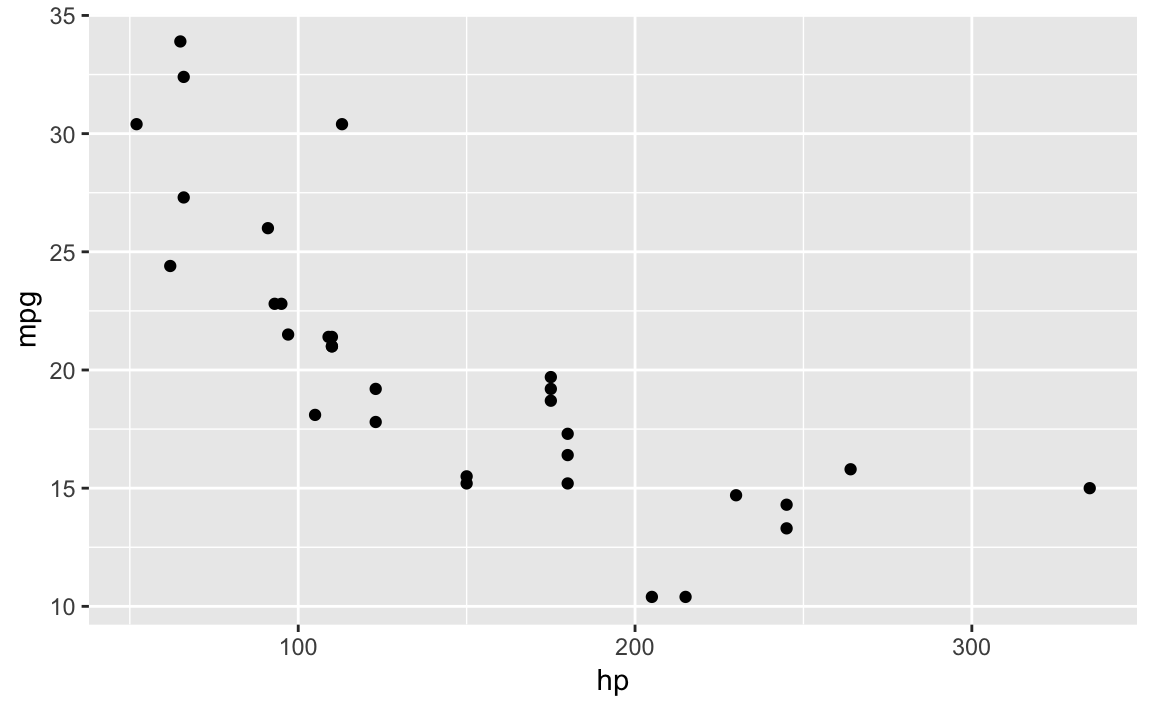

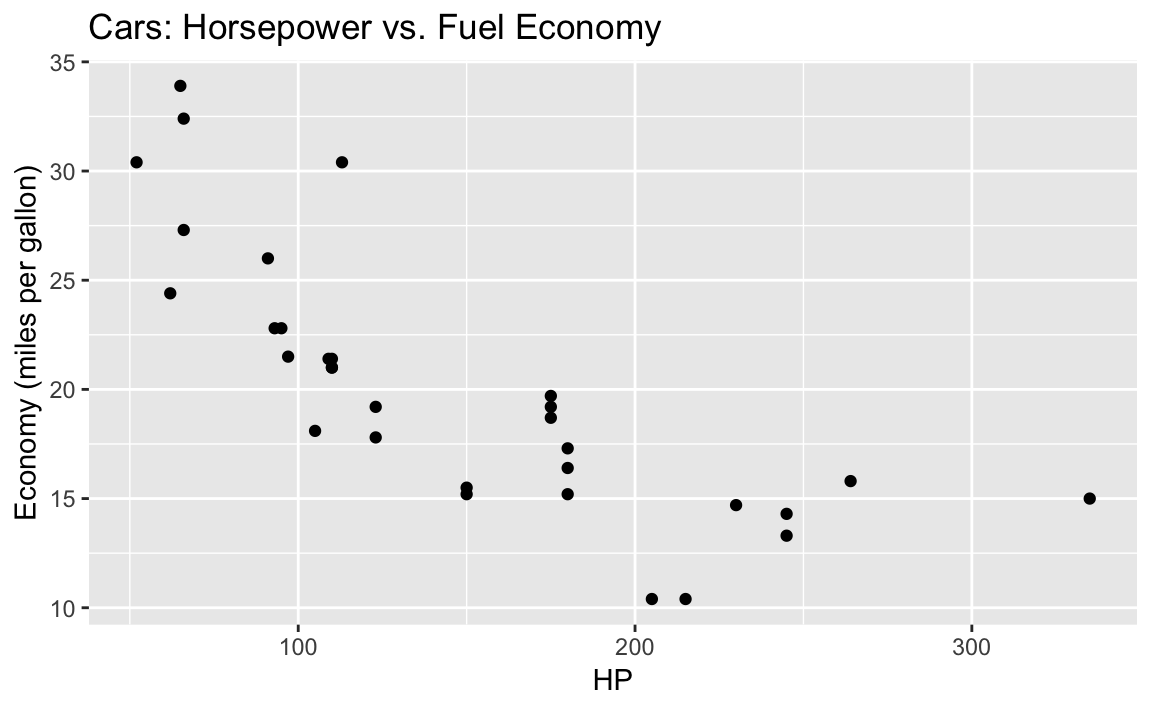

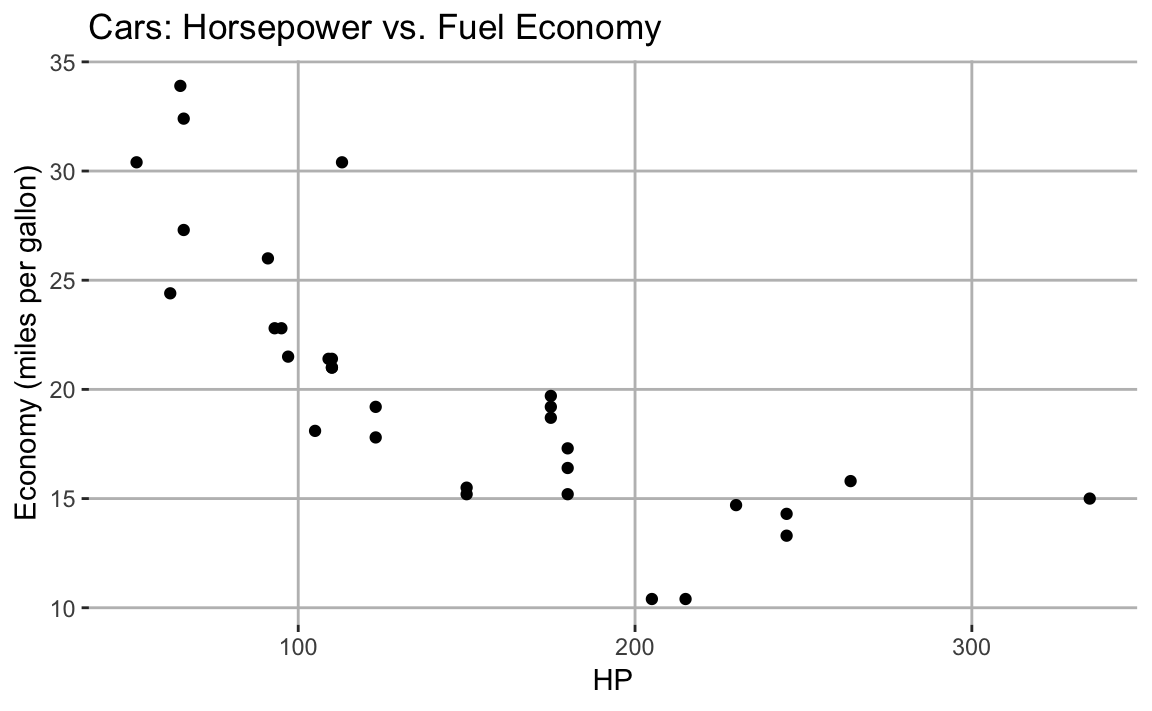

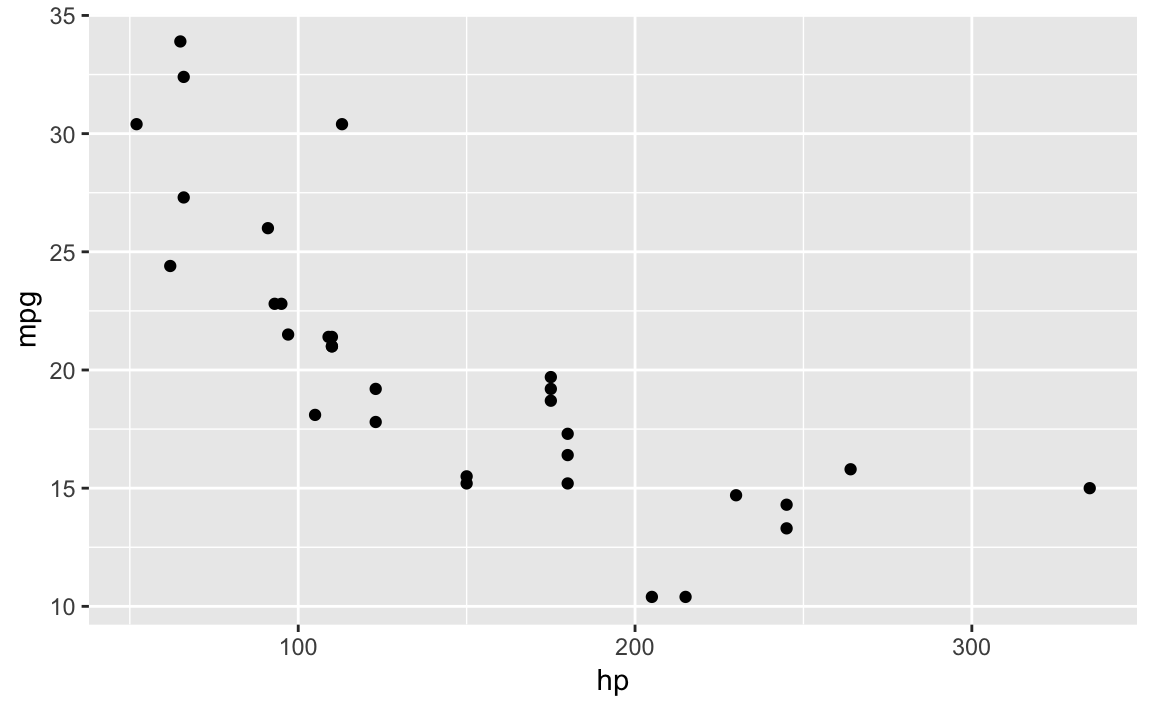

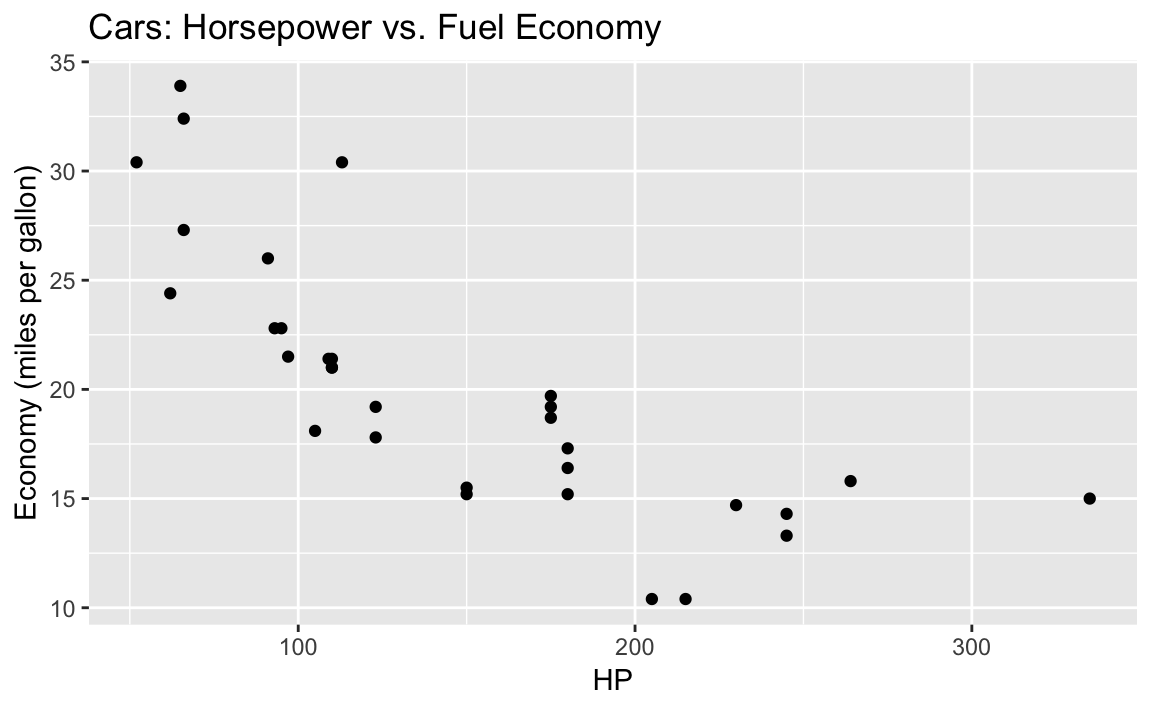

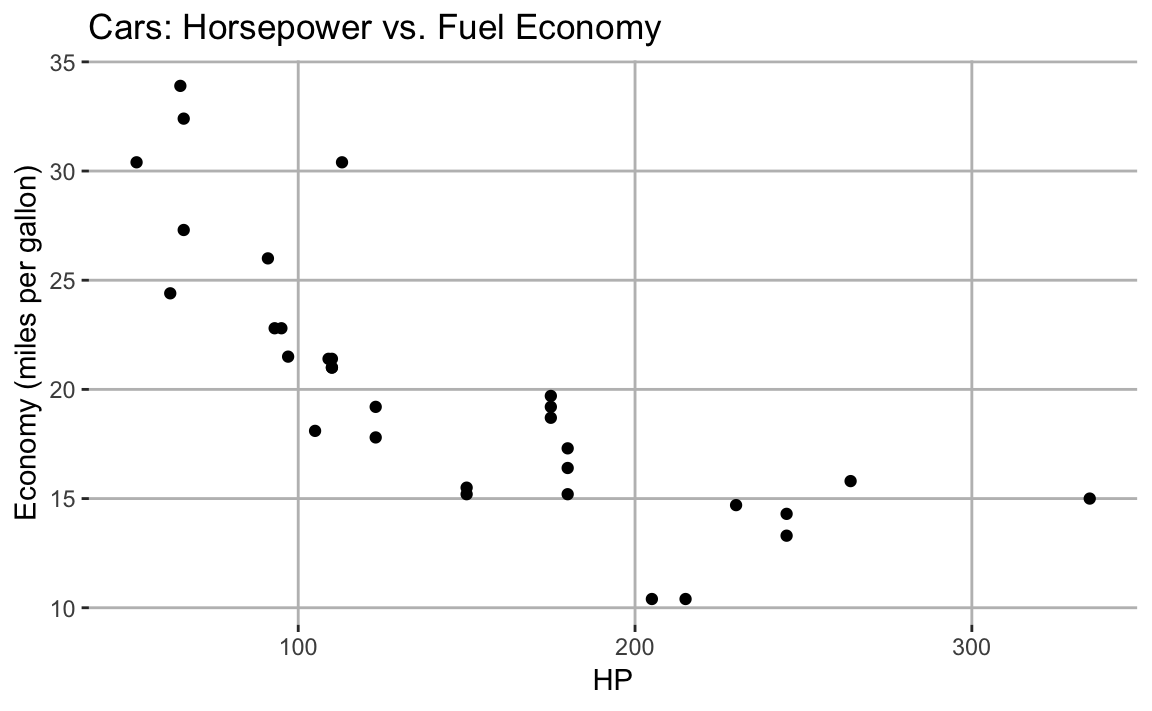

comes with R. For example, the dataset mtcars contains a data frame

with 32 records about different car models:

data(mtcars)head(mtcars)#> mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb#> Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.62 16.5 0 1 4 4#> Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.88 17.0 0 1 4 4#> Datsun 710 22.8 4 108 93 3.85 2.32 18.6 1 1 4 1#> Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258 110 3.08 3.21 19.4 1 0 3 1#> Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360 175 3.15 3.44 17.0 0 0 3 2#> Valiant 18.1 6 225 105 2.76 3.46 20.2 1 0 3 1

If your example is only reproducable with a bit of your own data, you

can use dput() to put a small bit of your own data in a string which

you can put in your example. We’ll illustrate that using two rows from

the mtcars data:

dput(head(mtcars,2))#> structure(list(mpg = c(21, 21), cyl = c(6, 6), disp = c(160,#> 160), hp = c(110, 110), drat = c(3.9, 3.9), wt = c(2.62, 2.875#> ), qsec = c(16.46, 17.02), vs = c(0, 0), am = c(1, 1), gear = c(4,#> 4), carb = c(4, 4)), row.names = c("Mazda RX4", "Mazda RX4 Wag"#> ), class = "data.frame")

You can put the resulting structure() directly in your question:

example_df<-structure(list(mpg=c(21,21),cyl=c(6,6),disp=c(160,160),hp=c(110,110),drat=c(3.9,3.9),wt=c(2.62,2.875),qsec=c(16.46,17.02),vs=c(0,0),am=c(1,1),gear=c(4,4),carb=c(4,4)),row.names=c("Mazda RX4","Mazda RX4 Wag"),class="data.frame")example_df#> mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb#> Mazda RX4 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.5 0 1 4 4#> Mazda RX4 Wag 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.88 17.0 0 1 4 4

The second part of a good reproducable example is the example minimal

code. The code example should be as simple as possible and illustrate

what you are trying to do or have already tried. This should not be a

big block of code with many different things going on. Boil your example

down to only the minimal amount of code needed. If you use any packages

be sure and include the library() call at the beginning of your code.

Also, don’t include anything in your question that will harm the state

of someone running your question code, such as rm(list=ls()) which

would delete all R objects in memory. Have empathy for the person trying

to help you and realize that they are volunteering their time to help

you out and may run your code on the same machine they do their own

work.

To test your example, open a new R session and try running your example.

Once you have edited your code, it’s time to give just a bit more

information to your potential question answerer. In the plain text of

the question, describe what you were trying to do, what you’ve tried,

and your question. Be as conscise as possible. Much like with the

example code, your objective is to communicate as efficiently as

possible with the person reading your question. You may find it helpful

to include in your description which version of R you are running as

well as which platform (Windows, Mac, Linux). You can get that

information easily with the sessionInfo() command.

If you are going to submit your question to the R mailing lists, you should know there are actually several mailing lists. R-help is the main list for general questions. There are also many special interest group (SIG) mailing lists dedicated to particular domains such as genetics, finance, R development, and even R jobs. You can see the full list at https://stat.ethz.ch/mailman/listinfo. If your question is specific to one such domain, you’ll get a better answer by selecting the appropriate list. As with R-help, however, carefully search the SIG list archives before submitting your question.

An excellent essay by Eric Raymond and Rick Moen is entitled “How to Ask Questions the Smart Way” (http://www.catb.org/~esr/faqs/smart-questions.html). We suggest that you read it before submitting any question. Seriously. Read it.

Stack Overflow has an excellent question that includes details about producing a reproducable example. You can find that here: https://stackoverflow.com/q/5963269/37751

Jenny Bryan has a great R package called reprex that helps in the

creation of a good reproduable example and the package has helper

functions that will help you write the markdown text for sites like

Stack Overflow. You can find that package on her Github page:

https://github.com/tidyverse/reprex

The recipes in this chapter lie somewhere between problem-solving ideas and tutorials. Yes, they solve common problems, but the Solutions showcase common techniques and idioms used in most R code, including the code in this Cookbook. If you are new to R, we suggest skimming this chapter to acquaint yourself with these idioms.

You want to display the value of a variable or expression.

If you simply enter the variable name or expression at the command

prompt, R will print its value. Use the print function for generic

printing of any object. Use the cat function for producing custom

formatted output.

It’s very easy to ask R to print something: just enter it at the command prompt:

pi#> [1] 3.14sqrt(2)#> [1] 1.41

When you enter expressions like that, R evaluates the expression and

then implicitly calls the print function. So the previous example is

identical to this:

(pi)#> [1] 3.14(sqrt(2))#> [1] 1.41

The beauty of print is that it knows how to format any R value for

printing, including structured values such as matrices and lists:

(matrix(c(1,2,3,4),2,2))#> [,1] [,2]#> [1,] 1 3#> [2,] 2 4(list("a","b","c"))#> [[1]]#> [1] "a"#>#> [[2]]#> [1] "b"#>#> [[3]]#> [1] "c"

This is useful because you can always view your data: just print it.

You need not write special printing logic, even for complicated data

structures.

The print function has a significant limitation, however: it prints

only one object at a time. Trying to print multiple items gives this

mind-numbing error message:

("The zero occurs at",2*pi,"radians.")#> Error in print.default("The zero occurs at", 2 * pi, "radians."): invalid 'quote' argument

The only way to print multiple items is to print them one at a time,

which probably isn’t what you want:

("The zero occurs at")#> [1] "The zero occurs at"(2*pi)#> [1] 6.28("radians")#> [1] "radians"

The cat function is an alternative to print that lets you

concatenate multiple items into a continuous output:

cat("The zero occurs at",2*pi,"radians.","\n")#> The zero occurs at 6.28 radians.

Notice that cat puts a space between each item by default. You must

provide a newline character (\n) to terminate the line.

The cat function can print simple vectors, too:

fib<-c(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34)cat("The first few Fibonacci numbers are:",fib,"...\n")#> The first few Fibonacci numbers are: 0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 ...

Using cat gives you more control over your output, which makes it

especially useful in R scripts that generate output consumed by others.

A serious limitation, however, is that it cannot print compound data

structures such as matrices and lists. Trying to cat them only

produces another mind-numbing message:

cat(list("a","b","c"))#> Error in cat(list("a", "b", "c")): argument 1 (type 'list') cannot be handled by 'cat'

See “Printing Fewer Digits (or More Digits)” for controlling output format.

You want to save a value in a variable.

Use the assignment operator (<-). There is no need to declare your

variable first:

x<-3

Using R in “calculator mode” gets old pretty fast. Soon you will want to define variables and save values in them. This reduces typing, saves time, and clarifies your work.

There is no need to declare or explicitly create variables in R. Just assign a value to the name and R will create the variable:

x<-3y<-4z<-sqrt(x^2+y^2)(z)#> [1] 5

Notice that the assignment operator is formed from a less-than character

(<) and a hyphen (-) with no space between them.

When you define a variable at the command prompt like this, the variable is held in your workspace. The workspace is held in the computer’s main memory but can be saved to disk. The variable definition remains in the workspace until you remove it.

R is a dynamically typed language, which means that we can change a

variable’s data type at will. We could set x to be numeric, as just

shown, and then turn around and immediately overwrite that with (say) a

vector of character strings. R will not complain:

x<-3(x)#> [1] 3x<-c("fee","fie","foe","fum")(x)#> [1] "fee" "fie" "foe" "fum"

In some R functions you will see assignment statements that use the

strange-looking assignment operator <<-:

x<<-3

That forces the assignment to a global variable rather than a local variable. Scoping is a bit, well, out of scope for this discussion, however.

In the spirit of full disclosure, we will reveal that R also supports

two other forms of assignment statements. A single equal sign (=) can

be used as an assignment operator. A rightward assignment operator

(->) can be used anywhere the leftward assignment operator (<-) can

be used (but with the arguments reversed):

foo<-3(foo)#> [1] 3

5->fum(fum)#> [1] 5

We recommend that you avoid these as well. The equals-sign assignment is easily confused with the test for equality. The rightward assignment can be useful in certain contexts, but it can be confusing to those not used to seeing it.

You’re getting tired of creating temporary, intermediate variables when doing analysis. The alternative, nesting R functions, seems nearly unreadable.

You can use the pipe operator (%>%) to make your data flow easier to

read and understand. It passes data from one step to another function

without having to name an intermediate variable.

library(tidyverse)mpg%>%head%>%#> # A tibble: 6 x 11#> manufacturer model displ year cyl trans drv cty hwy fl class#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <int> <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <chr> <chr>#> 1 audi a4 1.8 1999 4 auto~ f 18 29 p comp~#> 2 audi a4 1.8 1999 4 manu~ f 21 29 p comp~#> 3 audi a4 2 2008 4 manu~ f 20 31 p comp~#> 4 audi a4 2 2008 4 auto~ f 21 30 p comp~#> 5 audi a4 2.8 1999 6 auto~ f 16 26 p comp~#> 6 audi a4 2.8 1999 6 manu~ f 18 26 p comp~

It is identical to

(head(mpg))#> # A tibble: 6 x 11#> manufacturer model displ year cyl trans drv cty hwy fl class#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <int> <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <chr> <chr>#> 1 audi a4 1.8 1999 4 auto~ f 18 29 p comp~#> 2 audi a4 1.8 1999 4 manu~ f 21 29 p comp~#> 3 audi a4 2 2008 4 manu~ f 20 31 p comp~#> 4 audi a4 2 2008 4 auto~ f 21 30 p comp~#> 5 audi a4 2.8 1999 6 auto~ f 16 26 p comp~#> 6 audi a4 2.8 1999 6 manu~ f 18 26 p comp~

Both code fragments start with the mpg dataset, select the head of the

dataset, and print it.

The pipe operator (%>%), created by Stefan Bache and found in the

magrittr package, is used extensivly in the tidyverse and works

analogously to the Unix pipe operator (|). It doesn’t provide any new

functionality to R, but it can greatly improve readability of code.

The pipe operator takes the value on the left side of the operator and passes it as the first argument of the function on the right. These two lines of code are identical.

x%>%headhead(x)

For example, the Solution code

mpg%>%head%>%hasthesameeffectasthiscodewhichuseanintermediatevariable.

x<-head(mpg)(x)

This approach is fairly readable but creates intermediate data frames and requires the reader to keep track of them, putting a cognitive load on the reader.

This following code also has the same effect as the Solution by using nested function calls:

(head(mpg))

While this is very conscise since it’s only one line, this code requires much more attention to read and understand what’s going on. Code that is difficult for the user to parse mentally can introduce potential for error, and also make maintenance of the code harder in the future.

The function on the right-hand side of the %>% can include additional

arguments, and they will be included after the piped-in value. These two

lines of code are identical, for example.

iris%>%head(10)head(iris,10)

Sometimes, don’t want the piped value to be the first argument. In

those cases, use the dot expression (.) to indicate the desired

position. These two lines of code, for example, are identical.

10%>%head(x,.)head(x,10)

This is handy for functions where the first argument is not the principal input.

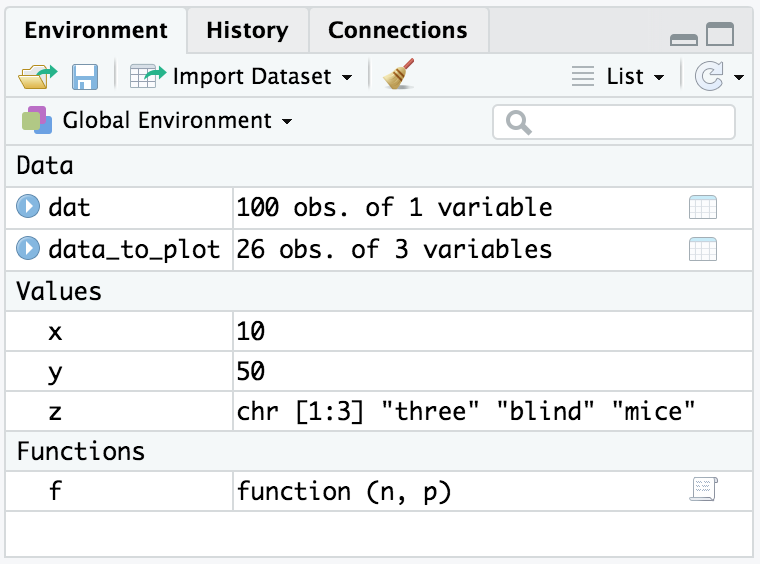

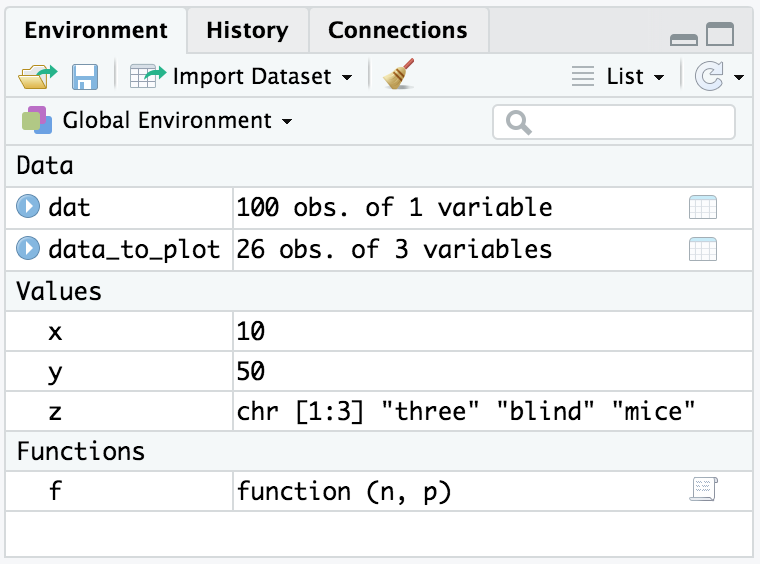

You want to know what variables and functions are defined in your workspace.

Use the ls function. Use ls.str for more details about each

variable.

The ls function displays the names of objects in your workspace:

x<-10y<-50z<-c("three","blind","mice")f<-function(n,p)sqrt(p*(1-p)/n)ls()#> [1] "f" "x" "y" "z"

Notice that ls returns a vector of character strings in which each

string is the name of one variable or function. When your workspace is

empty, ls returns an empty vector, which produces this puzzling

output:

ls()#> character(0)

That is R’s quaint way of saying that ls returned a zero-length vector

of strings; that is, it returned an empty vector because nothing is

defined in your workspace.

If you want more than just a list of names, try ls.str; this will also

tell you something about each variable:

x<-10y<-50z<-c("three","blind","mice")f<-function(n,p)sqrt(p*(1-p)/n)ls.str()#> f : function (n, p)#> x : num 10#> y : num 50#> z : chr [1:3] "three" "blind" "mice"

The function is called ls.str because it is both listing your

variables and applying the str function to them, showing their

structure (Revealing the Structure of an Object).

Ordinarily, ls does not return any name that begins with a dot (.).

Such names are considered hidden and are not normally of interest to

users. (This mirrors the Unix convention of not listing files whose

names begin with dot.) You can force ls to list everything by setting

the all.names argument to TRUE:

ls()#> [1] "f" "x" "y" "z"ls(all.names=TRUE)#> [1] ".Random.seed" "f" "x" "y"#> [5] "z"

See “Deleting Variables” for deleting variables and Recipe X-X for inspecting your variables.

You want to remove unneeded variables or functions from your workspace or to erase its contents completely.

Use the rm function.

Your workspace can get cluttered quickly. The rm function removes,

permanently, one or more objects from the workspace:

x<-2*pix#> [1] 6.28rm(x)x#> Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'x' not found

There is no “undo”; once the variable is gone, it’s gone.

You can remove several variables at once:

rm(x,y,z)

You can even erase your entire workspace at once. The rm function has

a list argument consisting of a vector of names of variables to

remove. Recall that the ls function returns a vector of variables

names; hence you can combine rm and ls to erase everything:

ls()#> [1] "f" "x" "y" "z"rm(list=ls())ls()#> character(0)

Alternativly you could click the broom icon in the top of the Environment pane in R Studio, shown in Figure 2-1.

Never put rm(list=ls()) into code you share with others, such as a

library function or sample code sent to a mailing list or Stack

Overflow. Deleting all the variables in someone else’s workspace is

worse than rude and will make you extremely unpopular.

See “Listing Variables”.

You want to create a vector.

Use the c(...) operator to construct a vector from given values.

Vectors are a central component of R, not just another data structure. A vector can contain either numbers, strings, or logical values but not a mixture.

The c(...) operator can construct a vector from simple elements:

c(1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21)#> [1] 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21c(1*pi,2*pi,3*pi,4*pi)#> [1] 3.14 6.28 9.42 12.57c("My","twitter","handle","is","@cmastication")#> [1] "My" "twitter" "handle" "is"#> [5] "@cmastication"c(TRUE,TRUE,FALSE,TRUE)#> [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE

If the arguments to c(...) are themselves vectors, it flattens them

and combines them into one single vector:

v1<-c(1,2,3)v2<-c(4,5,6)c(v1,v2)#> [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6

Vectors cannot contain a mix of data types, such as numbers and strings. If you create a vector from mixed elements, R will try to accommodate you by converting one of them:

v1<-c(1,2,3)v3<-c("A","B","C")c(v1,v3)#> [1] "1" "2" "3" "A" "B" "C"

Here, the user tried to create a vector from both numbers and strings. R converted all the numbers to strings before creating the vector, thereby making the data elements compatible. Note that R does this without warning or complaint.

Technically speaking, two data elements can coexist in a vector only if

they have the same mode. The modes of 3.1415 and "foo" are numeric

and character, respectively:

mode(3.1415)#> [1] "numeric"mode("foo")#> [1] "character"

Those modes are incompatible. To make a vector from them, R converts

3.1415 to character mode so it will be compatible with "foo":

c(3.1415,"foo")#> [1] "3.1415" "foo"mode(c(3.1415,"foo"))#> [1] "character"

c is a generic operator, which means that it works with many datatypes

and not just vectors. However, it might not do exactly what you expect,

so check its behavior before applying it to other datatypes and objects.

See the “Introduction” to the Chapter 5 chapter for more about vectors and other data structures.

You want to calculate basic statistics: mean, median, standard deviation, variance, correlation, or covariance.

Use one of these functions as applies, assuming that x and y are

vectors:

mean(x)

median(x)

sd(x)

var(x)

cor(x, y)

cov(x, y)

When you first use R you might open the docuentation and begin searching for material entitled “Procedures for Calculating Standard Deviation.” It seems that such an important topic would likely require a whole chapter.

It’s not that complicated.

Standard deviation and other basic statistics are calculated by simple functions. Ordinarily, the function argument is a vector of numbers and the function returns the calculated statistic:

x<-c(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34)mean(x)#> [1] 8.8median(x)#> [1] 4sd(x)#> [1] 11var(x)#> [1] 122

The sd function calculates the sample standard deviation, and var

calculates the sample variance.

The cor and cov functions can calculate the correlation and

covariance, respectively, between two vectors:

x<-c(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34)y<-log(x+1)cor(x,y)#> [1] 0.907cov(x,y)#> [1] 11.5

All these functions are picky about values that are not available (NA). Even one NA value in the vector argument causes any of these functions to return NA or even halt altogether with a cryptic error:

x<-c(0,1,1,2,3,NA)mean(x)#> [1] NAsd(x)#> [1] NA

It’s annoying when R is that cautious, but it is the right thing to do.

You must think carefully about your situation. Does an NA in your data

invalidate the statistic? If yes, then R is doing the right thing. If

not, you can override this behavior by setting na.rm=TRUE, which tells

R to ignore the NA values:

x<-c(0,1,1,2,3,NA)sd(x,na.rm=TRUE)#> [1] 1.14

In older versions of R, mean and sd were smart about data frames.

They understood that each column of the data frame is a different

variable, so they calculated their statistic for each column

individually. This is no longer the case and, as a result, you may read

confusing comments online or in older books (like version 1 of this

book). In order to apply the functions to each column of a dataframe we

now need to use a helper function. The Tidyverse family of helper

functions for this sort of thing are in the purrr package. As with

other Tidyverse packages, this gets loaded when you run

library(tidyverse). The function we’ll use to apply a function to each

column of a data frame is map_dbl:

data(cars)map_dbl(cars,mean)#> speed dist#> 15.4 43.0map_dbl(cars,sd)#> speed dist#> 5.29 25.77map_dbl(cars,median)#> speed dist#> 15 36

Notice that using map_dbl to apply mean or sd each return two

values, one for each column defined by the data frame. (Technically,

they return a two-element vector whose names attribute is taken from

the columns of the data frame.)

The var function understands data frames without the help of a mapping

function. It calculates the covariance between the columns of the data

frame and returns the covariance matrix:

var(cars)#> speed dist#> speed 28 110#> dist 110 664

Likewise, if x is either a data frame or a matrix, then cor(x)

returns the correlation matrix and cov(x) returns the covariance

matrix:

cor(cars)#> speed dist#> speed 1.000 0.807#> dist 0.807 1.000cov(cars)#> speed dist#> speed 28 110#> dist 110 664

See Recipes:

“Avoiding Some Common Mistakes”

“Merging Data Frames by Common Column”

Recipe X-X

You want to create a sequence of numbers.

Use an n:m expression to create the simple sequence n, n+1, n+2,

…, m:

1:5#> [1] 1 2 3 4 5

Use the seq function for sequences with an increment other than 1:

seq(from=1,to=5,by=2)#> [1] 1 3 5

Use the rep function to create a series of repeated values:

rep(1,times=5)#> [1] 1 1 1 1 1

The colon operator (n:m) creates a vector containing the sequence n,

n+1, n+2, …, m:

0:9#> [1] 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910:19#> [1] 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 199:0#> [1] 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Observe that R was clever with the last expression (9:0). Because 9 is

larger than 0, it counts backward from the starting to ending value. You

can also use the colon operator directly with the pipe to pass data to

another function:

10:20%>%mean()

The colon operator works for sequences that grow by 1 only. The seq

function also builds sequences but supports an optional third argument,

which is the increment:

seq(from=0,to=20)#> [1] 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20seq(from=0,to=20,by=2)#> [1] 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20seq(from=0,to=20,by=5)#> [1] 0 5 10 15 20

Alternatively, you can specify a length for the output sequence and then R will calculate the necessary increment:

seq(from=0,to=20,length.out=5)#> [1] 0 5 10 15 20seq(from=0,to=100,length.out=5)#> [1] 0 25 50 75 100

The increment need not be an integer. R can create sequences with fractional increments, too:

seq(from=1.0,to=2.0,length.out=5)#> [1] 1.00 1.25 1.50 1.75 2.00

For the special case of a “sequence” that is simply a repeated value you

should use the rep function, which repeats its first argument:

rep(pi,times=5)#> [1] 3.14 3.14 3.14 3.14 3.14

See “Creating a Sequence of Dates” for creating a sequence of Date objects.

You want to compare two vectors or you want to compare an entire vector against a scalar.

The comparison operators (==, !=, <, >, <=, >=) can perform

an element-by-element comparison of two vectors. They can also compare a

vector’s element against a scalar. The result is a vector of logical

values in which each value is the result of one element-wise comparison.

R has two logical values, TRUE and FALSE. These are often called

Boolean values in other programming languages.

The comparison operators compare two values and return TRUE or

FALSE, depending upon the result of the comparison:

a<-3a==pi# Test for equality#> [1] FALSEa!=pi# Test for inequality#> [1] TRUEa<pi#> [1] TRUEa>pi#> [1] FALSEa<=pi#> [1] TRUEa>=pi#> [1] FALSE

You can experience the power of R by comparing entire vectors at once. R will perform an element-by-element comparison and return a vector of logical values, one for each comparison:

v<-c(3,pi,4)w<-c(pi,pi,pi)v==w# Compare two 3-element vectors#> [1] FALSE TRUE FALSEv!=w#> [1] TRUE FALSE TRUEv<w#> [1] TRUE FALSE FALSEv<=w#> [1] TRUE TRUE FALSEv>w#> [1] FALSE FALSE TRUEv>=w#> [1] FALSE TRUE TRUE

You can also compare a vector against a single scalar, in which case R will expand the scalar to the vector’s length and then perform the element-wise comparison. The previous example can be simplified in this way:

v<-c(3,pi,4)v==pi# Compare a 3-element vector against one number#> [1] FALSE TRUE FALSEv!=pi#> [1] TRUE FALSE TRUE

(This is an application of the Recycling Rule, “Understanding the Recycling Rule”.)

After comparing two vectors, you often want to know whether any of the

comparisons were true or whether all the comparisons were true. The

any and all functions handle those tests. They both test a logical

vector. The any function returns TRUE if any element of the vector

is TRUE. The all function returns TRUE if all elements of the

vector are TRUE:

v<-c(3,pi,4)any(v==pi)# Return TRUE if any element of v equals pi#> [1] TRUEall(v==0)# Return TRUE if all elements of v are zero#> [1] FALSE

You want to extract one or more elements from a vector.

Select the indexing technique appropriate for your problem:

Use square brackets to select vector elements by their position, such

as v[3] for the third element of v.

Use negative indexes to exclude elements.

Use a vector of indexes to select multiple values.

Use a logical vector to select elements based on a condition.

Use names to access named elements.

Selecting elements from vectors is another powerful feature of R. Basic selection is handled just as in many other programming languages—use square brackets and a simple index:

fib<-c(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34)fib#> [1] 0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34fib[1]#> [1] 0fib[2]#> [1] 1fib[3]#> [1] 1fib[4]#> [1] 2fib[5]#> [1] 3

Notice that the first element has an index of 1, not 0 as in some other programming languages.

A cool feature of vector indexing is that you can select multiple elements at once. The index itself can be a vector, and each element of that indexing vector selects an element from the data vector:

fib[1:3]# Select elements 1 through 3#> [1] 0 1 1fib[4:9]# Select elements 4 through 9#> [1] 2 3 5 8 13 21

An index of 1:3 means select elements 1, 2, and 3, as just shown. The indexing vector needn’t be a simple sequence, however. You can select elements anywhere within the data vector—as in this example, which selects elements 1, 2, 4, and 8:

fib[c(1,2,4,8)]#> [1] 0 1 2 13

R interprets negative indexes to mean exclude a value. An index of −1, for instance, means exclude the first value and return all other values:

fib[-1]# Ignore first element#> [1] 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34

This method can be extended to exclude whole slices by using an indexing vector of negative indexes:

fib[1:3]# As before#> [1] 0 1 1fib[-(1:3)]# Invert sign of index to exclude instead of select#> [1] 2 3 5 8 13 21 34

Another indexing technique uses a logical vector to select elements from

the data vector. Everywhere that the logical vector is TRUE, an

element is selected:

fib<10# This vector is TRUE wherever fib is less than 10#> [1] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSEfib[fib<10]# Use that vector to select elements less than 10#> [1] 0 1 1 2 3 5 8fib%%2==0# This vector is TRUE wherever fib is even#> [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUEfib[fib%%2==0]# Use that vector to select the even elements#> [1] 0 2 8 34

Ordinarily, the logical vector should be the same length as the data vector so you are clearly either including or excluding each element. (If the lengths differ then you need to understand the Recycling Rule, “Understanding the Recycling Rule”.)

By combining vector comparisons, logical operators, and vector indexing, you can perform powerful selections with very little R code:

Select all elements greater than the median

v<-c(3,6,1,9,11,16,0,3,1,45,2,8,9,6,-4)v[v>median(v)]#> [1] 9 11 16 45 8 9

Select all elements in the lower and upper 5%

v[(v<quantile(v,0.05))|(v>quantile(v,0.95))]#> [1] 45 -4

The above example uses the | operator which means “or” when indexing.

If you wanted “and” you use the & operator.

Select all elements that exceed ±1 standard deviations from the mean

v[abs(v-mean(v))>sd(v)]#> [1] 45 -4

Select all elements that are neither NA nor NULL

v<-c(1,2,3,NA,5)v[!is.na(v)&!is.null(v)]#> [1] 1 2 3 5

One final indexing feature lets you select elements by name. It assumes

that the vector has a names attribute, defining a name for each

element. This can be done by assigning a vector of character strings to

the attribute:

years<-c(1960,1964,1976,1994)names(years)<-c("Kennedy","Johnson","Carter","Clinton")years#> Kennedy Johnson Carter Clinton#> 1960 1964 1976 1994

Once the names are defined, you can refer to individual elements by name:

years["Carter"]#> Carter#> 1976years["Clinton"]#> Clinton#> 1994

This generalizes to allow indexing by vectors of names: R returns every element named in the index:

years[c("Carter","Clinton")]#> Carter Clinton#> 1976 1994

See “Understanding the Recycling Rule” for more about the Recycling Rule.

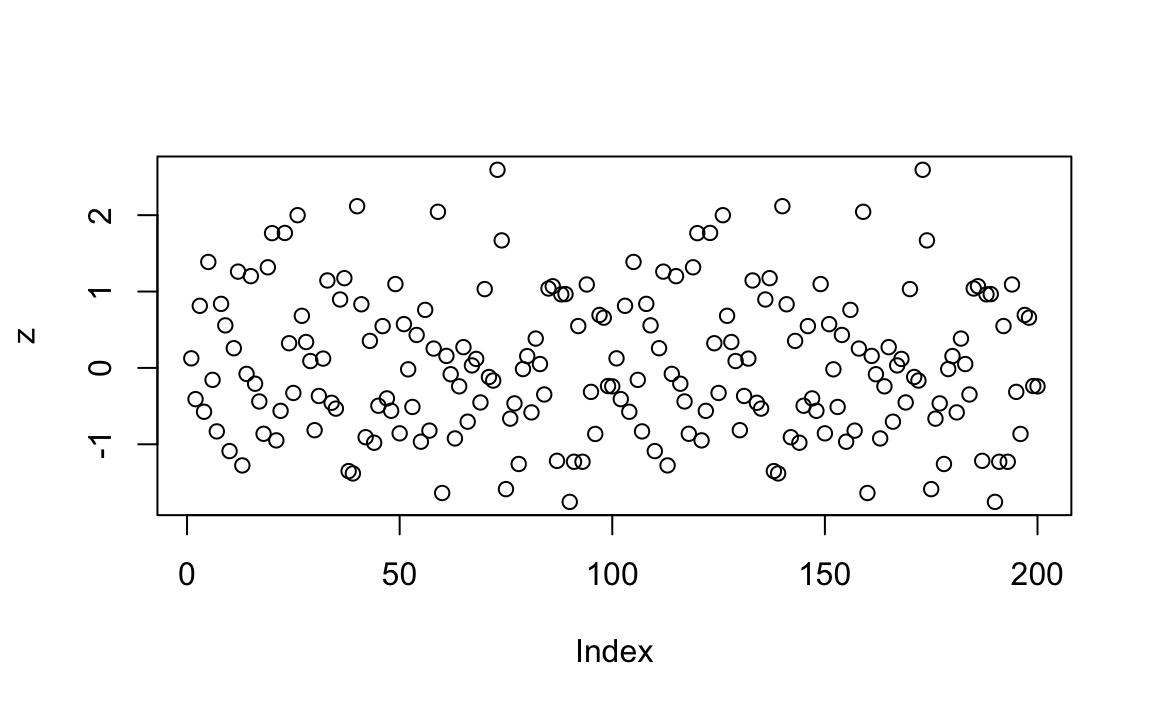

You want to operate on an entire vector at once.

The usual arithmetic operators can perform element-wise operations on entire vectors. Many functions operate on entire vectors, too, and return a vector result.

Vector operations are one of R’s great strengths. All the basic arithmetic operators can be applied to pairs of vectors. They operate in an element-wise manner; that is, the operator is applied to corresponding elements from both vectors:

v<-c(11,12,13,14,15)w<-c(1,2,3,4,5)v+w#> [1] 12 14 16 18 20v-w#> [1] 10 10 10 10 10v*w#> [1] 11 24 39 56 75v/w#> [1] 11.00 6.00 4.33 3.50 3.00w^v#> [1] 1.00e+00 4.10e+03 1.59e+06 2.68e+08 3.05e+10

Observe that the length of the result here is equal to the length of the original vectors. The reason is that each element comes from a pair of corresponding values in the input vectors.

If one operand is a vector and the other is a scalar, then the operation is performed between every vector element and the scalar:

w#> [1] 1 2 3 4 5w+2#> [1] 3 4 5 6 7w-2#> [1] -1 0 1 2 3w*2#> [1] 2 4 6 8 10w/2#> [1] 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.52^w#> [1] 2 4 8 16 32

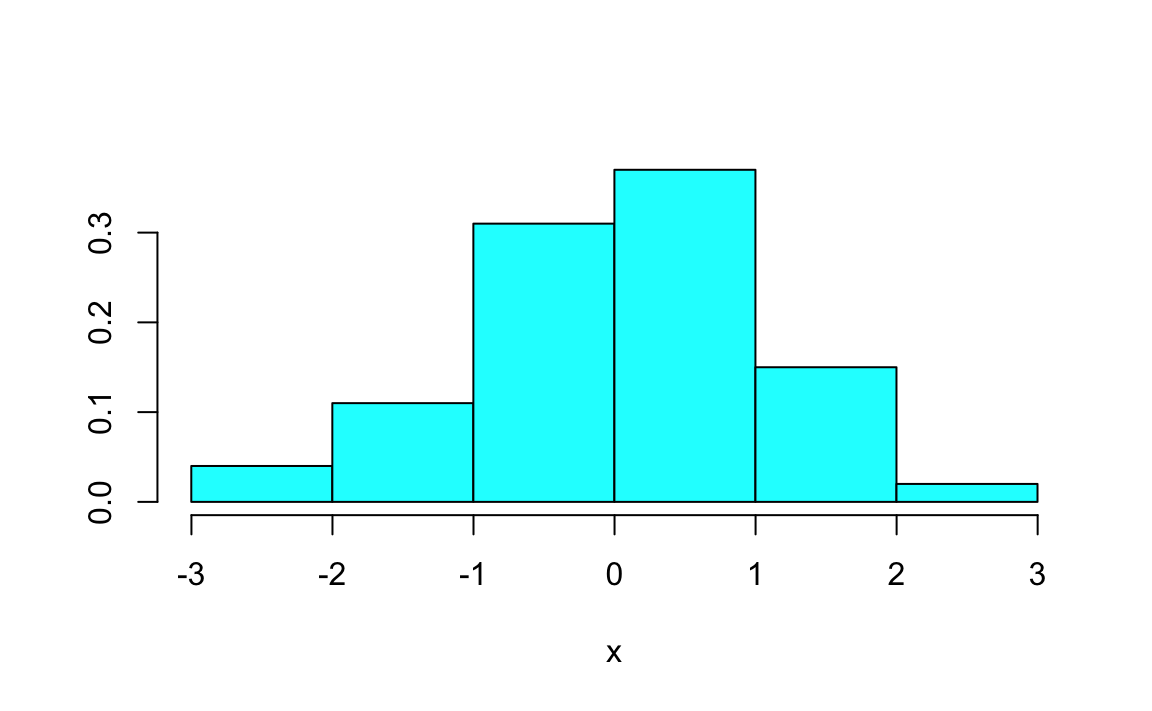

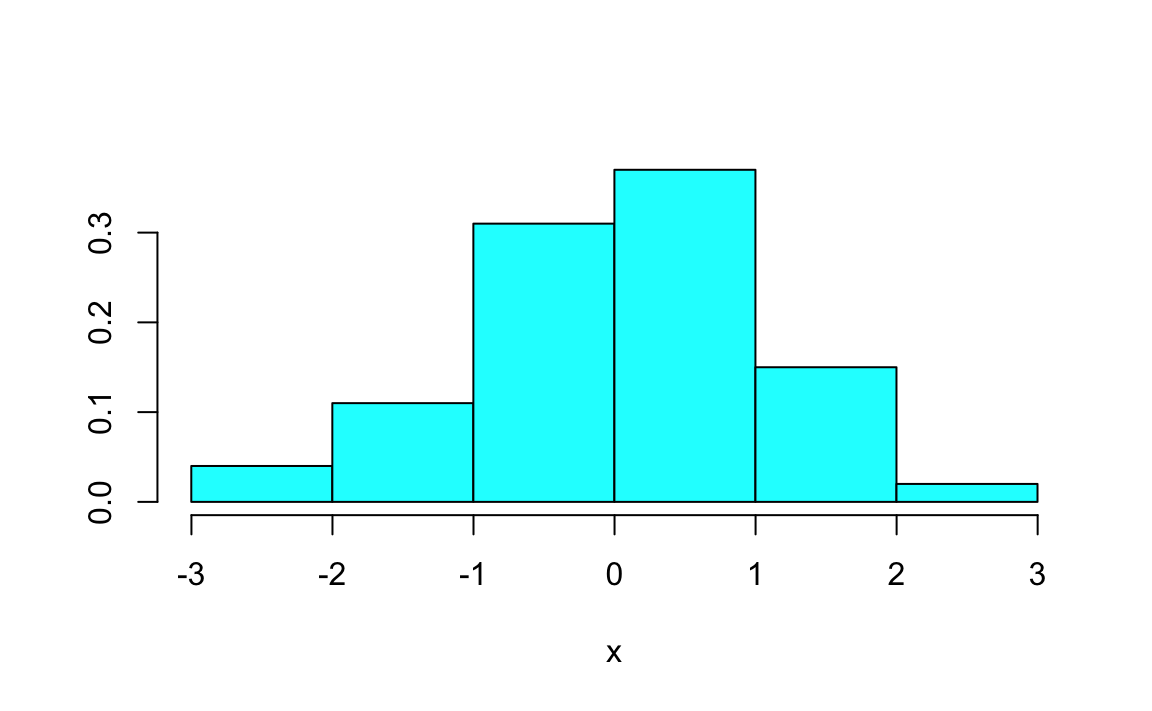

For example, you can recenter an entire vector in one expression simply by subtracting the mean of its contents:

w#> [1] 1 2 3 4 5mean(w)#> [1] 3w-mean(w)#> [1] -2 -1 0 1 2

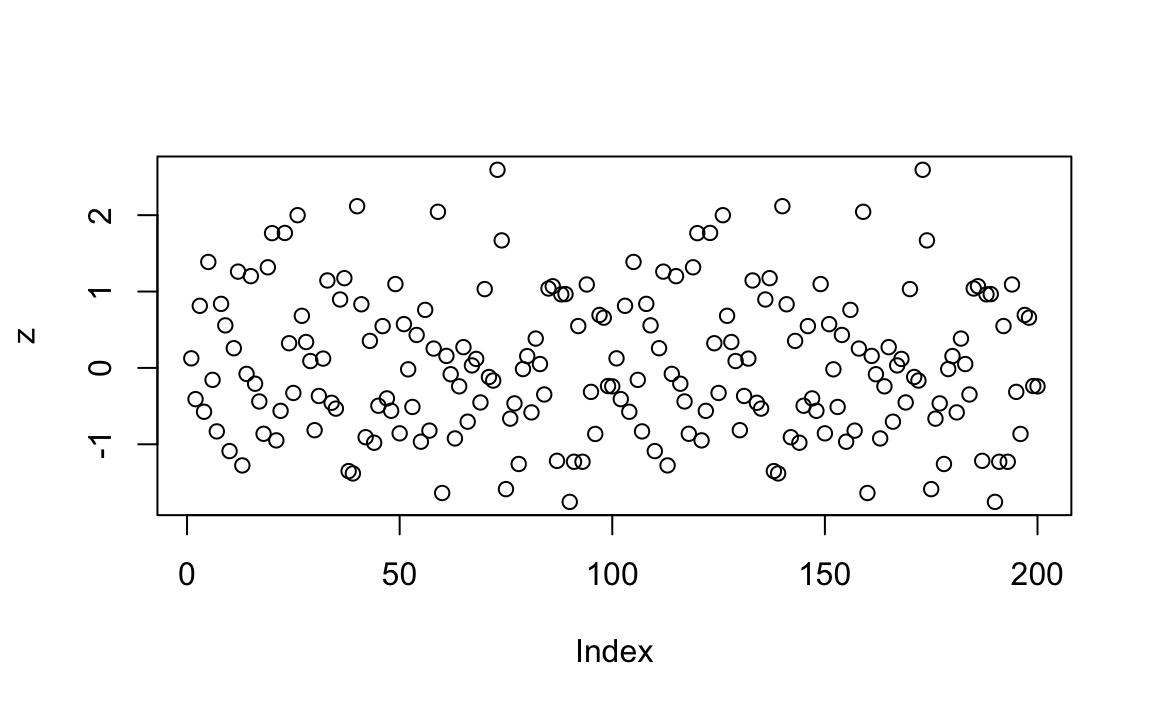

Likewise, you can calculate the z-score of a vector in one expression: subtract the mean and divide by the standard deviation:

w#> [1] 1 2 3 4 5sd(w)#> [1] 1.58(w-mean(w))/sd(w)#> [1] -1.265 -0.632 0.000 0.632 1.265

Yet the implementation of vector-level operations goes far beyond

elementary arithmetic. It pervades the language, and many functions

operate on entire vectors. The functions sqrt and log, for example,

apply themselves to every element of a vector and return a vector of

results:

w<-1:5w#> [1] 1 2 3 4 5sqrt(w)#> [1] 1.00 1.41 1.73 2.00 2.24log(w)#> [1] 0.000 0.693 1.099 1.386 1.609sin(w)#> [1] 0.841 0.909 0.141 -0.757 -0.959

There are two great advantages to vector operations. The first and most obvious is convenience. Operations that require looping in other languages are one-liners in R. The second is speed. Most vectorized operations are implemented directly in C code, so they are substantially faster than the equivalent R code you could write.

Performing an operation between a vector and a scalar is actually a special case of the Recycling Rule; see “Understanding the Recycling Rule”.

Your R expression is producing a curious result, and you wonder if operator precedence is causing problems.

The full list of operators is shown in table @ref(tab:precedence), listed in order of precedence from highest to lowest. Operators of equal precedence are evaluated from left to right except where indicated.

| Operator | Meaning | See also |

|---|---|---|

|

Indexing |

|

|

Access variables in a name space (environment) |

|

|

Component extraction, slot extraction |

|

|

Exponentiation (right to left) |

|

|

Unary minus and plus |

|

|

Sequence creation |

Recipes pass:[<a data-type="xref” data-xrefstyle="select:labelnumber” href="#recipe-id021">#recipe-id021</a>, <a data-type="xref” data-xrefstyle="select:labelnumber” href="#recipe-id047">#recipe-id047</a> |

|

g |

Discussion |

|

Multiplication, division |

Discussion |

|

Addition, subtraction |

|

|

Comparison |

|

|

Logical negation |

|

|

Logical “and”, short-circuit “and” |

|

` |

||

` |

Logical “or”, short-circuit “or” |

|

|

Formula |

|

|

Rightward assignment |

|

|

Assignment (right to left) |

|

|

Assignment (right to left) |

|

|

Help |

It’s not important that you know what every one of these operators do, or what they mean. The list here is to expose you to the idea that different operators have different precedence.

Getting your operator precedence wrong in R is a common problem. It

certainly happens to the authors a lot. We unthinkingly expect that the

expression 0:n−1 will create a sequence of integers from 0 to n − 1

but it does not:

n<-100:n-1#> [1] -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

It creates the sequence from −1 to n − 1 because R interprets it as

(0:n)−1.

You might not recognize the notation %`_any_%` in the table. R

interprets any text between percent signs (%…%) as a binary

operator. Several such operators have predefined meanings:

%%Modulo operator

%/%Integer division

%*%Matrix multiplication

%in%Returns TRUE if the left operand occurs in its right operand;

FALSE otherwise

%>%Pipe that passes results from the left to a function on the right

You can also define new binary operators using the %…% notation;

see Defining Your Own Binary Operators. The point

here is that all such operators have the same precedence.

See “Performing Vector Arithmetic” for more about vector operations, “Performing Matrix Operations” for more about matrix operations, and Recipe X-X to define your own operators. See the Arithmetic and Syntax topics in the R help pages as well as Chapters 5 and 6 of R in a Nutshell (O’Reilly).

You are getting tired of typing long sequences of commands and especially tired of typing the same ones over and over.

Open an editor window and accumulate your reusable blocks of R commands there. Then, execute those blocks directly from that window. Reserve the command line for typing brief or one-off commands.

When you are done, you can save the accumulated code blocks in a script file for later use.

The typical beginner to R types an expression in the console window and sees what happens. As he gets more comfortable, he types increasingly complicated expressions. Then he begins typing multiline expressions. Soon, he is typing the same multiline expressions over and over, perhaps with small variations, in order to perform his increasingly complicated calculations.

The experienced user does not often retype a complex expression. She may type the same expression once or twice, but when she realizes it is useful and reusable she will cut-and-paste it into an editor window. To execute the snippet thereafter, she selects the snippet in the editor window and tells R to execute it, rather than retyping it. This technique is especially powerful as her snippets evolve into long blocks of code.

In R Studio, a few features of the IDE facilitate this workstyle. Windows and Linux machines have slightly different keys than Mac machines: Windows/Linux uses the Ctrl and Alt modifiers, whereas the Mac uses Cmd and Opt.

From the main menu, select File → New File then select the type of file you want to create, in this case, an R Script.

Position the cursor on the line and then press Ctrl+Enter (Windows) or Cmd+Enter (Mac) to execute it.

Highlight the lines using your mouse; then press Ctrl+Enter (Windows) or Cmd+Enter (Mac) to execute them.

Press Ctrl+Alt+R (Windows) or Cmd+Opt+R (Mac) to execute the whole

editor window. Or from the menu click Code → Run Region →

Run All

These keyboard shortcuts and dozens more can be found within R Studio by

clicking the menu: Tools → Keyboard Shortcuts Help

Copying lines from the console window to the editor window is simply a matter of copy and paste. When you exit R Studio, it will ask if you want to save the new script. You can either save it for future reuse or discard it.

Creating many intermediate variables in your code is tedious and overly verbose, while nesting R functions seems nearly unreadable.

Use the pipe operator (%>%) to make your expression easier to read and

write. The pipe operator (%>%), created by Stefan Bache and found in

the magrittr package and used extensivly in many tidyverse functions

as well.

Us the pipe operator to combine multiple functions together into a “pipeline” of functions without intermediate variables:

library(tidyverse)data(mpg)mpg%>%filter(cty>21)%>%head(3)%>%()#> # A tibble: 3 x 11#> manufacturer model displ year cyl trans drv cty hwy fl class#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <int> <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <chr> <chr>#> 1 chevrolet mali~ 2.4 2008 4 auto~ f 22 30 r mids~#> 2 honda civic 1.6 1999 4 manu~ f 28 33 r subc~#> 3 honda civic 1.6 1999 4 auto~ f 24 32 r subc~

The pipe is much cleaner and easier to read than using intermediate temporary variables:

temp1<-filter(mpg,cty>21)temp2<-head(temp1,3)(temp2)#> # A tibble: 3 x 11#> manufacturer model displ year cyl trans drv cty hwy fl class#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <int> <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <chr> <chr>#> 1 chevrolet mali~ 2.4 2008 4 auto~ f 22 30 r mids~#> 2 honda civic 1.6 1999 4 manu~ f 28 33 r subc~#> 3 honda civic 1.6 1999 4 auto~ f 24 32 r subc~

The pipe operator does not provide any new functionality to R, but it can greatly improve readability of code. The pipe operator takes the output of the function or object on the left of the operator and passes it as the first argument of the function on the right.

Writing this:

x%>%head()

is functionally the same as writing this:

head(x)

In both cases x is the argument to head. We can supply additional

arguments, but x is always the first argument. These two lines are

functionally identical:

x%>%head(n=10)head(x,n=10)

This difference may seem small, but with a more complicated example, the

benefits begin to accumulate. If we had a workflow where we wanted to

use filter to limit our data to values, then select to keep only

certain variables, followed by ggplot to create a simple plot, we

could use intermediate variables.

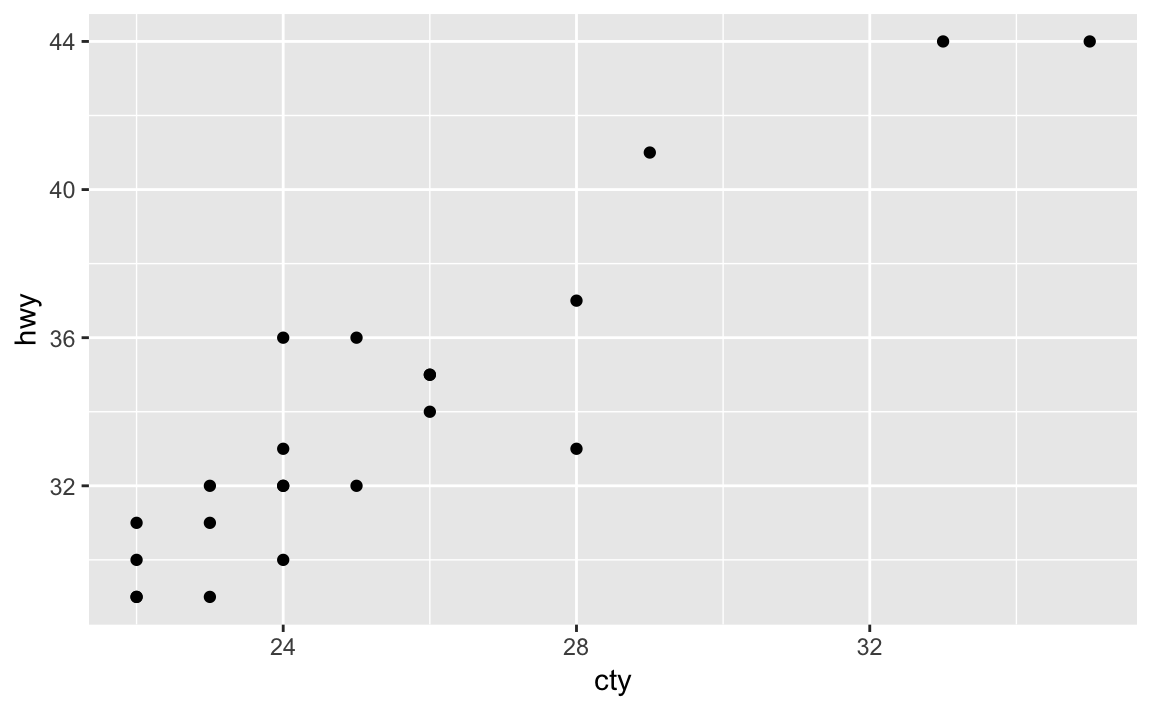

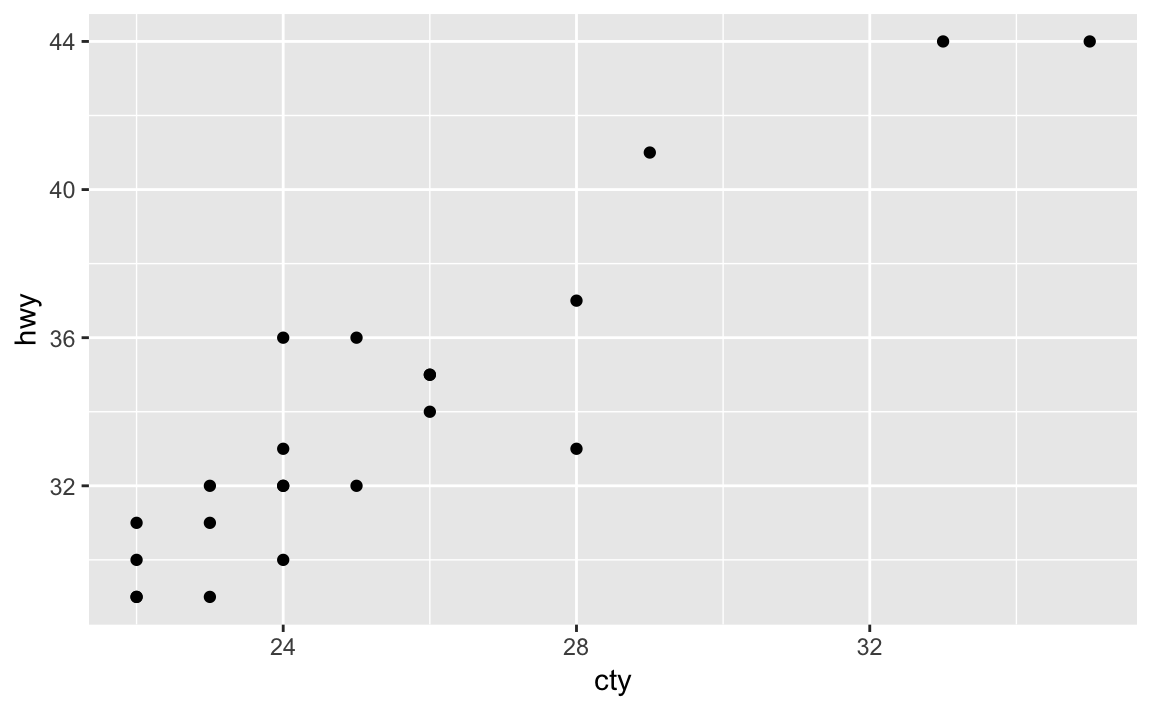

library(tidyverse)filtered_mpg<-filter(mpg,cty>21)selected_mpg<-select(filtered_mpg,cty,hwy)ggplot(selected_mpg,aes(cty,hwy))+geom_point()

This incremental approach is fairly readable but creates a number of intermediate data frames and requires the user to keep track of the state of many objects which can generate a cognitive load on the user.

Another alternative is to nest the functions together:

ggplot(select(filter(mpg,cty>21),cty,hwy),aes(cty,hwy))+geom_point()

While this is very concise since it’s only one line, this code requires much more attention to read and understand what’s going on. Code that is difficult for the user to parse mentally can introduce potential for error, and also make maintenance of the code harder in the future.

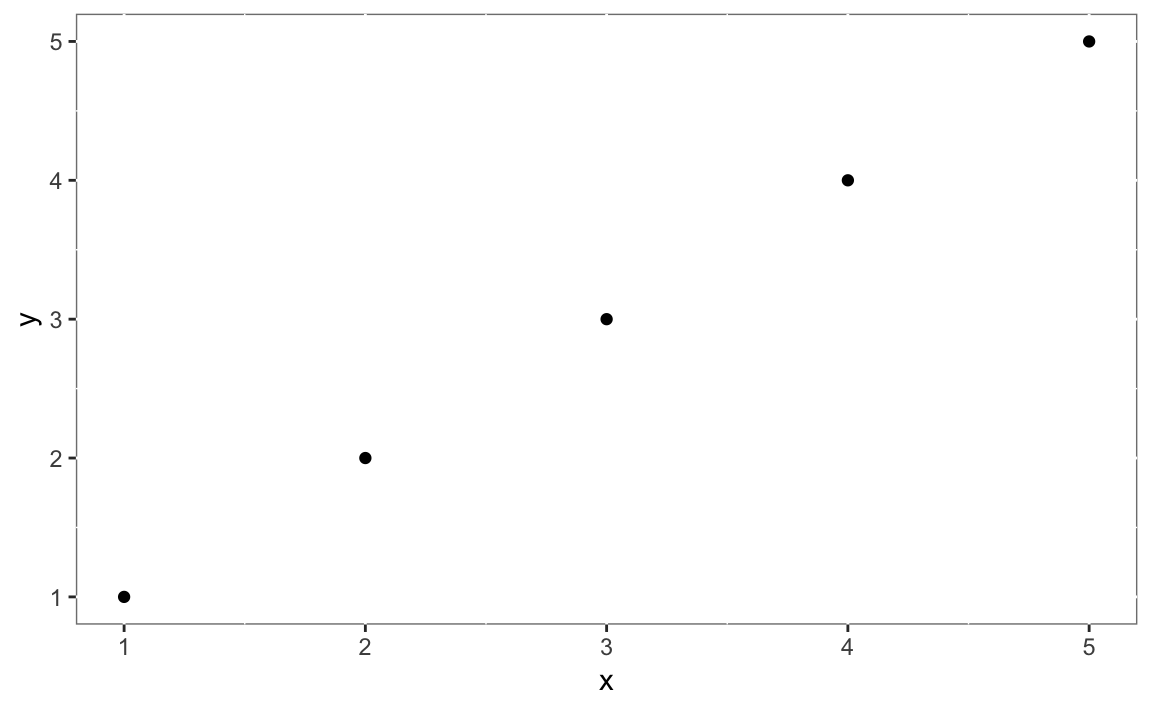

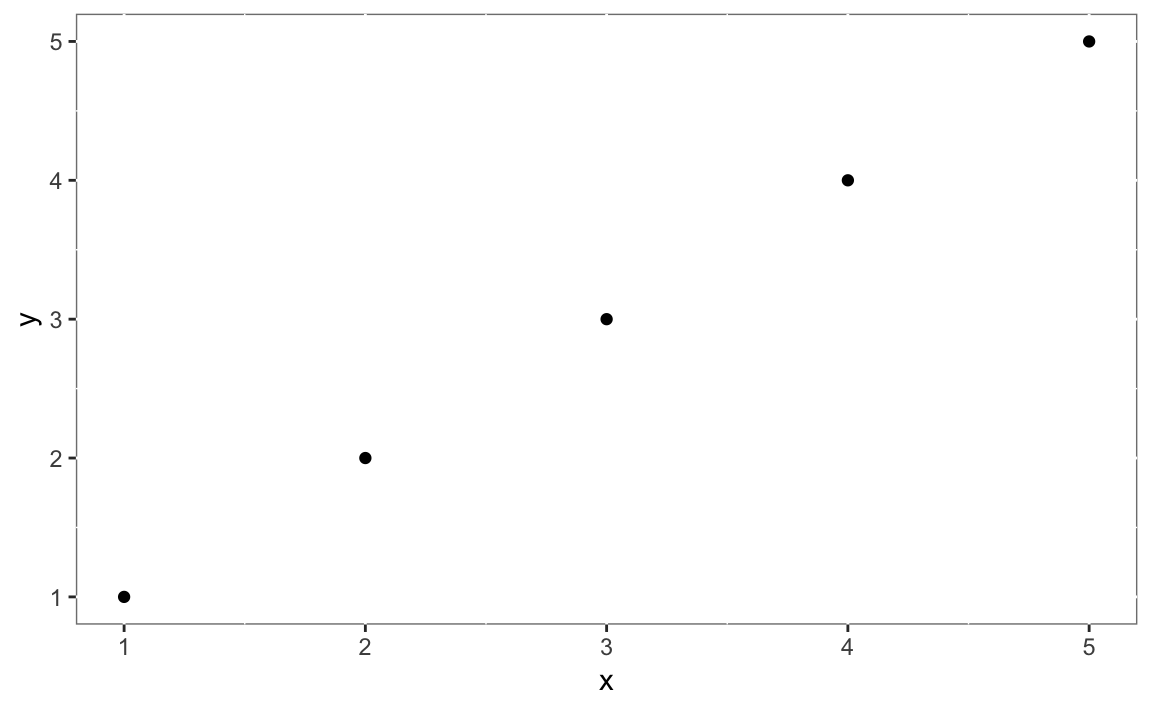

mpg%>%filter(cty>21)%>%select(cty,hwy)%>%ggplot(aes(cty,hwy))+geom_point()

The above code starts with the mpg dataset, pipes it to the filter

function which keeps only records where the city mpg (cty) is greater

than 21. Those results are piped into the select command that keeps

only the listed variables cty and hwy and those are piped into the

ggplot command where an point plot is produced in Figure 2-2

If you want the argument going into your target (right hand side)

function to be somewhere other than the first argument, use the dot

(.) operator:

iris%>%head(3)

is the same as:

iris%>%head(3,x=.)

However in the second example we passed the iris data frame into the second named argument using the dot operator. This can be handy for functions where the input data frame goes in a position other than the first argument.

Through this book we use pipes to hold together data transformations with multiple steps. We typically format the code with a line break after each pipe and then we indent the code on the following lines. This makes the code easily identifiable as parts of the same data pipeline.

You want to avoid some of the common mistakes made by beginning users—and also by experienced users, for that matter.

Here are some easy ways to make trouble for yourself:

Forgetting the parentheses after a function invocation:

You call an R function by putting parentheses after the name. For

instance, this line invokes the ls function:

ls()

However, if you omit the parentheses then R does not execute the function. Instead, it shows the function definition, which is almost never what you want:

ls# > function (name, pos = -1L, envir = as.environment(pos), all.names = FALSE,# > pattern, sorted = TRUE)# > {# > if (!missing(name)) {# > pos <- tryCatch(name, error = function(e) e)# > if (inherits(pos, "error")) {# > name <- substitute(name)# > if (!is.character(name))# > name <- deparse(name)# > etc...

Forgetting to double up backslashes in Windows file paths

This function call appears to read a Windows file called

F:\research\bio\assay.csv, but it does not:

tbl<-read.csv("F:\research\bio\assay.csv")

Backslashes (\) inside character strings have a special meaning and

therefore need to be doubled up. R will interpret this file name as

F:researchbioassay.csv, for example, which is not what the user

wanted. See “Dealing with “Cannot Open File” in Windows” for possible solutions.

Mistyping “<-” as “< (blank) -”

The assignment operator is <-, with no space between the < and the

-:

x<-pi# Set x to 3.1415926...

If you accidentally insert a space between < and -, the meaning

changes completely:

x<-pi# Oops! We are comparing x instead of setting it!#> [1] FALSE

This is now a comparison (<) between x and negative π (-pi). It