Chapter 21. The Extra Mile

Congratulations! You’ve made it to the last chapter! Here’s a cookie:

document.cookie = "username=LastChapter; expires=OnReceipt 12:00:00 UTC";

After reading this book, you should be ready to provide the sound building blocks of an information security program. You should also be fully equipped to handle the common insecure practices that we’ve seen in so many environments. But the learning doesn’t stop here! Here in the extra mile we’ll give you some additional tidbits of information and some great resources for you to go check out that will make your defenses that much stronger.

Email Servers

Running and installing an email server is a large time and technology commitment. Modern spam filters block 99.99% of email, while more than 80% of daily email traffic is junk mail. Bulk spam and phishing issues will be concerns, as well as other commonly misconfigured server settings.

Many email servers currently on the internet are misconfigured, which contributes in part to the amount of spam being sent. These configurations not only contribute to spam, but they may delay or prevent the organization’s mail from being delivered. Certain configurations will land the IP or domain of the mail server on a blacklist, which organizations can subscribe to for enhancing filtering efforts. There are some common configuration checks should be performed on mail servers being hosted in your environment. MXToolbox provides a large list of different tests that can be performed to test these configurations.

There are several configurations that should be made to a mail server on the internet:

- Open mail relay

-

Having a mail server set up as an open relay allows anyone who can access it on port 25 to send mail through it as anyone she wants. Mail servers should be configured to only relay messages for the domains that they are associated with.

- Server hello

-

A mail server hello (aka HELO/EHLO) is the command an SMTP server sends to identify itself during a message exchange. While having an incorrect hello does not impact the server’s ability to send or receive mail, it should identify the sending server in such a way that it can be used to identify servers with problems, such as leaking spam or incorrectly formatted emails. An example of a correct mail server hello is

HELO mx.batsareawesome.com, while other settings such as localhost or 74.122.238.160 (the public mail server IP address) are against the RFC and best practice. - Mail reverse DNS

-

Another property that spam filtering uses is looking at reverse DNS (rDNS) or PTR (pointer) records on an IP address attempting to deliver mail. A generic reverse DNS record is common when the device sending mail has no control over changing it to a correct setting. For example, a residential IP address through a local DSL provider will have a record of something like “dsl-nor-65-88-244-120.ambtel.net” for the IP address 65.88.244.120. This is a generic rDNS that is autogenerated for the majority of public IP addresses dynamically given from internet service providers (ISPs). When operating a mail server, more than likely the IP address will be a static address that will need to be configured to have an rDNS record to match that of the server. Unless your organization owns and controls its own public IP addressing space, the ISP or other upstream provider will need to be contacted to make the change on their nameserver to match the hostname and corresponding A record of the sending server (instead of using an individual’s account, an alias of mail.batsareawesome.com).

- Email aliases and group nesting

-

While not necessarily a direct security issue, making use of email aliases and group nesting (groups within groups) is a good habit to get into. For example: Aaron is the lead security engineer. He has all licensing information and alerting sent to his mailbox and uses rules to disperse them throughout the different teams. When Aaron leaves, his account becomes corrupted somehow, or something else happens to it, and it becomes a large task to reset everything to go to a new person. Instead, an alias of high-ids-alerts@lintile.com could contain both the SOC group and SecEngineer group, which would automatically disperse the alerts to where they need to go regardless of whether Aaron stays with the company. Another example would be for licensing information. Many times management and engineers need to have working knowledge of license expiration and renewals. For example, the BHAFSEC company could use a specific alias account such as licensing@bhafsec.com. This could be used for SSL and software licensing, and contain the Exec and SecEngineer groups. These examples greatly reduce the amount of possible miscommunication.

- Outsourcing your email server is not a crime

-

Given all the effort involved to keep an email server running, filtering spam, not acting as an open relay, and any number of other issues, it may well suit your organization to simply outsource the day-to-day management of your email. Google Apps and Office 365, for example, both offer managed services whereby user administration is the only task left. Both organizations have large, capable security teams, which could free you up to pursue other more important tasks.

DNS Servers

Domain Name Servers/Service (DNS) is a main building block of the internet and technology in general. There are several main attacks to design a DNS infrastructure around preventing DNS spoofing, DNS ID hacking, and DNS cache poisoning. DNS spoofing is a term referring to the action of a malicious server answering a DNS request that was intended for another server. Spoofing can only be completed with the addition of ID hacking. DNS queries contain a specific ID that the attacker must have to successfully spoof the server. DNS cache poisoning is an attack consisting of making a DNS server cache false information. Usually this consists of a wrong record that will map a domain name to a “wrong” IP address. All of these are in an attempt to force connections to a malicious service or server.

Steps can be taken to prevent and safeguard against attacks on DNS servers and infrastructures:

- Restrict recursive queries

-

Recursion is the process a DNS server uses to resolve names for which it is not authoritative. If the DNS server doesn’t contain a zone file that is authoritative for the domain in the query, the DNS server will forward the connection to other DNS servers using the process of recursion. The problem is that DNS servers that perform recursion are more vulnerable to denial of service (DoS) attacks. Because of this, you should disable recursion on the DNS servers in your organization that will only answer queries for which they are authoritative—typically, this means queries for your internal resources.

- Segregate internal and external DNS servers

-

Restrict the possible queries and the possible hosts who are allowed to query to the minimum. Not every network device needs to be able to resolve addresses on the internet. In most cases, the only machines that need to be able to resolve external addresses are gateway devices, such as a web proxy server. The majority of devices will be configured to use internal DNS servers that do not perform recursion for public names.

- Restrict DNS zone transfers to only trusted name servers

-

By issuing a specific request (AXFR), the entirety of the DNS server database can be obtained. While this isn’t a significant security threat, it does give an attacker an upper hand by having internal information and a list of subdomains and settings.

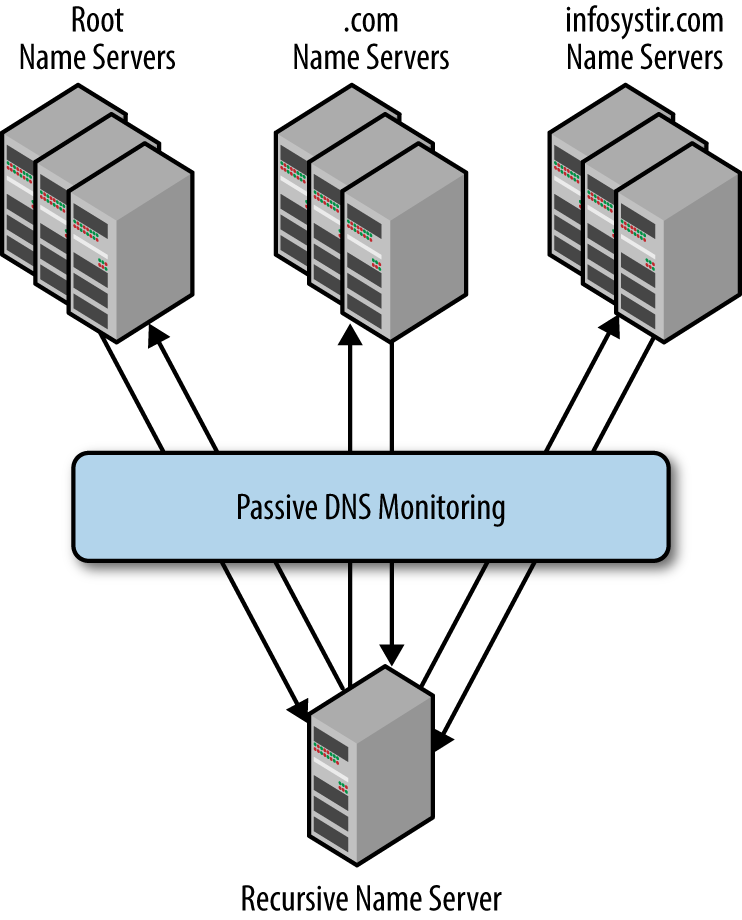

- Implement passive DNS

-

A passive DNS server (shown in Figure 21-1) will cache DNS information, queries, and errors from the server-to-server communication between your main DNS server and other DNS servers on the internet. The passive DNS server can take this information, and compress it into a centralized database for analysis. This database can be used for security measures such as new domain alerting. A good percentage of brand new domains are spun up solely for the purpose of distributing malware.

Figure 21-1. Passive DNS

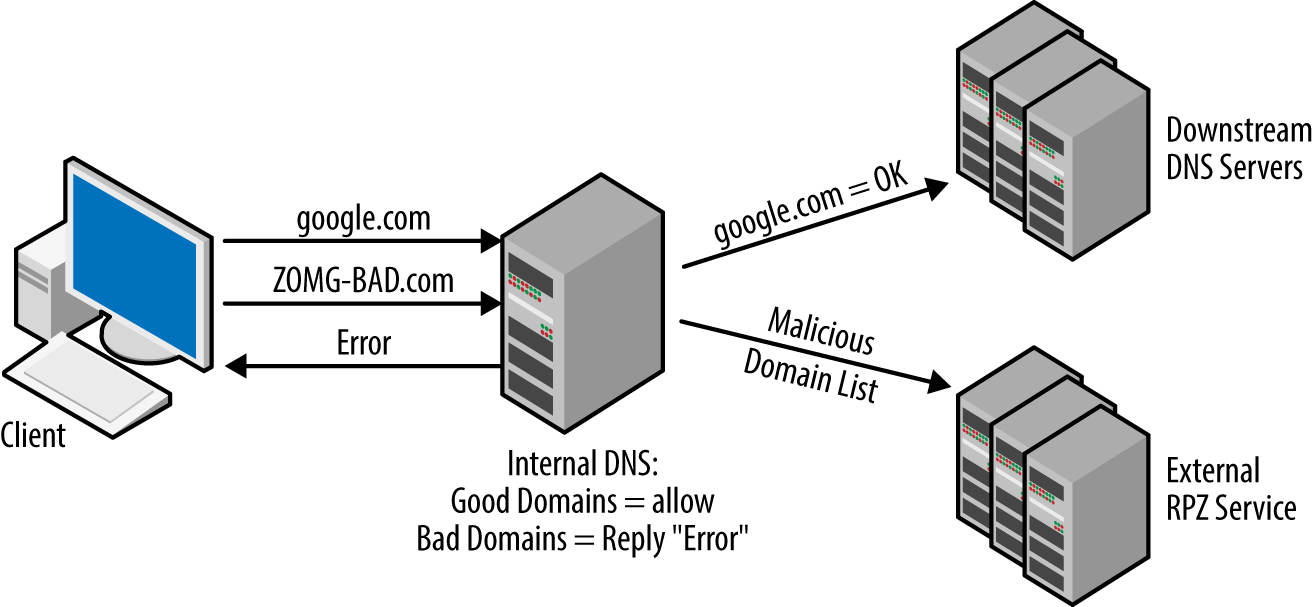

- Implement a DNS sinkhole or BlackholeDNS

-

A DNS sinkhole server works by spoofing the authoritative DNS server for known bad domains to combat malware and viruses, as shown in Figure 21-2. It then returns a false address that is nonroutable, ensuring the client is not able to connect to the malicious site. Malicious domains can be gathered from already known C&C servers through the malware analysis process, open source sites that are providing malicious IP details, and phishing emails. They make use of Response Policy Zone (RPZ) DNS records.

Figure 21-2. Sinkhole DNS

- DNSSEC

-

DNS Security Extensions is a set of extensions to DNS that provide the resolvers origin authentication of DNS data. We recommend that you do not implement this. It has extremely high risks for the small amount that may be gained. Not only is there risk of taking down all of the DNS infrastructure, but it can provide attackers with a reliable source of dDoS amplification using the large secure DNS packets.

Security through Obscurity

Security through obscurity is the term used for “hiding” assets, services, or procedures in nonstandard ways. When used as the basis of a security program it is useless, but there are some methods than can be used just as an added measure.

Do:

-

Set up services on nonstandard ports. Instead of a web administrative logon listening on port 443, change it to 4043 or set the ftp server to listen on port 2222.

-

Rename the local Administrator account to something else that makes sense for your organization.

-

Reconfigure service banners not to report the server OS type and version.

Don’t:

-

Block Shodan’s scanners/crawlers or other internet scanners from accessing public IP addresses. Just because a single service won’t be indexing the data doesn’t mean malicious people aren’t going to find it. As we’ve demonstrated, you can use Shodan’s services to assist in finding security gaps.

-

Label datacenters and equipment closets “Network Data Center” or something super obvious.

-

Put any device or service on an internet-facing connection without having it tested for vulnerabilities.

Useful Resources

Finally, we finish with a list of books, blogs, podcasts, and websites that we find useful.

Books

-

Blueteam Handbook: Incident Response Edition by Don Murdoch

-

Building an Information Security Awareness Program: Defending Against Social Engineering and Technical Threats by Bill Gardner and Valerie Thomas

-

Complete Guide to Shodan by John Matherly

-

Designing and Building Security Operations Center by David Nathans

-

Hacking Exposed Industrial Control Systems: ICS and SCADA Security Secrets & Solutions by Clint Bodungen, Bryan Singer, Aaron Shbeeb, Kyle Wilhoit, and Stephen Hilt

-

How to Develop and Implement a Security Master Plan by Timothy Giles

Tools

Lynis: Linux/Unix/MacOS security auditing tool

Microsoft Sysinternals: Suite of helpful Microsoft troubleshooting tools

Netdisco: Network mapping tool