Chapter 13. Password Management and Multifactor Authentication

The use of passwords in regards to technology has been around since the early 1960s, when the first shared environment was born. MIT’s Compatible Time-Sharing System was the first multiuser computer. At this early stage there was little-to-no password security, as previously only physical security was used to limit access. The CTSS passwords in theory were only accessible by the administrators, but an admin error in the late ’60s caused widespread display of all users’ plain text passwords during login after the message-of-the-day file was swapped with the password file. Oops!

Passwords have come a long way since then and some professionals even have the opinion that they are useless. While we do agree that some password implementations can be incredibly insecure, they can also add another layer of security. Passwords can be the keys to the kingdom and they aren’t going anywhere any time soon. There are many ways to ensure that the transmission and storage of passwords are securely implemented. In this chapter, you’ll learn how best to manage passwords and go a little bit behind the scenes on how they work.

Basic Password Practices

Simple password hashes can be cracked in less than a second with some trivial knowledge. Password cracking software such as John the Ripper support the cracking of hundreds of types of hashes using brute force or rainbow tables. Brute force attacks often use dictionary files, which are large text files containing thousands upon thousands of plain text passwords that are commonly used and have been stripped from data breaches and other sources. Both the tool and the dictionaries are readily available on the internet.

Let’s start with some basic math surrounding the length and complexity of passwords. The times listed are approximate and wouldn’t take into consideration if a service doesn’t allow certain characters:

-

8 characters at only lowercase equals 26^8. Extremely easy, will crack in < 2 minutes.

-

8 characters at upper- and lowercase equals 52^8. Still not the best, will crack in < 6 hours.

-

8 characters at uppercase, lowercase, and numbers equals 62^8. A little better, will crack in < 24 hours.

-

10-character passphrase with uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols 94^10. Approximately 600 years.1

Rainbow tables are a relatively modern twist on the brute-force attack as the cost of storage has become cheaper, allowing for a processing time/storage trade-off. A rainbow table contains a list of precomputed and stored hashes and their associated cleartext. A rainbow table attack against a password hash does not rely on computation, but on being able to look up the password hash in the precomputed table.

While long and complex passwords won’t matter if the backend encryption is weak or there has been a breach involving them, it will protect against brute-force attacks.

Teaching users and requiring administrators to create complex passwords is an overall win for everyone. One way of making secure passwords easier to remember is using phrases from books, songs, expressions, etc., and substituting characters. They then become a passphrase instead and are inherently more secure. For example:

Amanda and Lee really love their password security = A&LeeR<3TPS

Another learning opportunity for end users, and possibly even an enterprise-wide shift in process, would be to not trust others with passwords. Helpdesk staff should not be asking for passwords, ever, period. Users should be educated to the fact that no one in the organization would ask for their password, and to do the right thing and report anyone who does. The idea of keeping passwords to yourself doesn’t only apply to humans. Internet browsers store passwords encoded in a way that is publicly known, and thus easy to decode. Password recovery tools, which are easily available online, enable anyone to see all the passwords stored in the browser and open user profiles.

Password Management Software

In this day and age we have passwords for everything. Some of us have systems that make remembering passwords easier, but for the majority of users it isn’t feasible to expect them to remember a different password for each piece of software or website. Don’t make the mistake of reusing passwords for accounts. In the increasingly likely event that a website with stored password hashes gets hacked, attackers will inevitably start cracking passwords. If passwords are successfully cracked, particularly those associated with an email address, attackers will probably attempt to reuse those credentials on other sites. By never reusing passwords, or permutations on passwords, this attack can be thwarted. Whether it is a personal account or an enterprise account, passwords should not be reused. Sites and services with confidential or powerful access should always have unique complex passwords.

Password reuse is a common problem that can be solved by using a password manager. There are many different options from free to paid versions of password management software. Password management implementations vary, from the rudimentary password-storing features in most browsers to specialized products that synchronize the saved passwords across different devices and automatically fill login forms as needed. Perform significant research to come up with the best fit for your organization. Some questions that should be asked when looking into the software include:

-

Are there certain passwords that need to be shared among admins such as for a root or sa account?

-

Will you be using two-factor authentication to log in to the password manager? (Hint: you should.)

-

Do you want to start with a free solution that has fewer features, or with a paid version that will allow more room to grow, and better ease of use? You may want to start with the free version and then decide later if it makes sense to move to something more robust. Take note that many free versions of software are for personal use only.

-

Is there a one-time cost or a recurring fee?

-

Should the system have a built-in password generator and strength meter?

-

Is there a need for it to auto-fill application or website fields?

-

Does the password manager use strong encryption?

-

Does it have a lockout feature?

-

Does it include protection from malicious activity, such as keystroke logging—and if so, which kinds of activity?

In all cases, the master password should be well protected; it’s best to memorize it rather than write it down, although writing it down and keeping it in a secure location is also an option. It’s never a bad idea to have a physical copy of major user accounts and passwords written down or printed out in a vault in case of emergency. Before deciding on a password manager, read reviews of the various products in order to understand how they work and what they are capable of doing. Some reviews include both strengths and weakness. Perform analysis as well by reading background information on vendors’ websites. When a password manager has been chosen, get it directly from the vendor and verify that the installer is not installing a maliciously modified version by checking an MD5 hash of the installer. If a hash is not available, request one from the vendor; if the vendor cannot provide a verification method, be skeptical. Although moving to a password manager may take a little effort, in the long run it is a safe and convenient method of keeping track of the organization’s passwords and guarding specific online information.

Password Resets

Password reset questions when not using 2FA (or when using it when poorly implemented) can be a surefire way for an attacker to get into an account and cut the user off from accessing it. Answers to the questions “What is your mother’s maiden name?” “What city were you born in?” or “Where did you graduate high school?” are added onto an account for “security” purposes. The majority of answers to these questions are easily found on the internet, guessed, or even socially engineered out of the user.

When designing a system that allows password resets, try to not use standard everyday questions that are easily guessed. A method of ensuring the security questions are not brute forced would be to supply false information. The answer to “What is the name of your elementary school?” could be “Never gonna give you up” or “Never gonna let you down.” The answers can then be stored away in a password manager as it would be incredibly hard to remember the answer that has been supplied.

Password Breaches

According to the 2016 Verizon Data Breach Incident Report, 63% of confirmed data breaches involved weak, default, or stolen passwords and 76% of network intrusions were carried out by compromised user accounts. Looking at some numbers of overall breaches in 2015, the numbers of unique accounts are staggering (see Table 13-1).

| Totals for Category | # of Breaches | # of Records | % of Breaches | % of Records |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Banking/Credit/Financial |

71 |

5,063,044 |

9.1% |

2.8% |

|

Business |

312 |

16,191,017 |

40.0% |

9.1 |

|

Educational |

58 |

759,600 |

7.4% |

0.4% |

|

Government/Military |

63 |

34,222,763 |

8.1% |

19.2% |

|

Medical/Healthcare |

276 |

121,629,812 |

35.4 % |

68.4% |

Good password security will allow you to minimize the impact of the consistent breaches on personal accounts, as well as making it less likely that the enterprise will have a breach.

Encryption, Hashing, and Salting

There is a common misunderstanding of these three terms. It will be extremely helpful to understand what encryption, hashing, and salting mean and the difference between them. All three can be involved with password implementations and it’s best to know a little about them and how they work.

Encryption

Encryption has been around for an awfully long time. The Egyptians used it to create mystery and amusement, and the Romans used it to send secret messages. Encrypting a password consists of applying an algorithm that scrambles the data, and then a key can be used that returns the scrambled data to it’s original state. ROT13 is one of the simplest examples of a substitution cipher. It basically replaces each letter with one 13 places away in the alphabet:

Amanda and Lee are awesome = Nznaqn naq Yrr ner njrfbzr

ROT13 is obviously a weak cipher, but it is useful to illustrate the key point here: encrypted data is reversible to anyone who knows the key; in this case it is that the shift size is 13. It is like that by design. There is no point encrypting a secret message if the person at the other end is unable to decipher it. Therefore, it is useful in situations such as VPNs, HTTPS traffic, and many other forms of communication. Other common encryption algorithms include Triple DES, AES, RSA, and Blowfish.

Hashing

Hashing is different from encryption in that once the data is encoded, it cannot be decoded. The lossy nature of the algorithms makes reversal mathematically impossible; however, brute forcing all possible variants of the source material and hashing it until a match is found is a technique that can yield results, as is the case with password brute forcing. Unlike encryption, for most algorithms, the output is always of a fixed length.

Using our phrase from before and the MD5 algorithm, we get:

Amanda and Lee are awesome = 2180c081189a03be77d7626a2cf0b1b5

If we try a longer phrase we get:

Amanda and Lee are awesome at creating examples = 51eba84dc16afa016077103c1b05d84a

The results are both the same length. This means that multiple inputs could result in the same output, which is called a collision. Collisions are unavoidable when using the same hashing algorithm on a large data set, but can be useful for comparing the validity of other types of data. MD5 is also a hashing algorithm that can easily be cracked.

Hashing is useful when storing things that do not need to be read back, but would like to have the capability of checking validity. Passwords are the primary example. Instead of storing the cleartext, the hashed version is stored. Then, when someone types in their password, the same hashing algorithm is applied and compared with what is located in the database, which looks for a match. Hash functions can also be used to test whether information, programs, or other data has been tampered with.

The important factor for hashing algorithms is that they only work one way. The only way to work out the original value is to use brute force by trying multiple values to see if they produce the same hash.

This is particularly problematic with passwords, which are generally short and use commonly found words. It would not take a modern computer extensive time to run through a large dictionary (or use existing rainbow tables) and figure out the hashed result of every common password. This is where salting comes in.

Salting

Salting works by adding an extra secret value to the input, extending the length of the original password.

In this example the password is Defensive and the salt value is Security.Handbook. The hash value would be made up from the combination of the two: DefensiveSecurity.Handbook. This provides some protection for those people who use common words as their password. However, if someone learns the salt value that is used, then they just add it to the end (or start) of each dictionary word they try in their attack. To make brute forcing attacks more difficult, random salts can be used, one for each password. Salts can also be created from multiple parts, such as the current date-time, the username, a secret phrase, a random value, or a combination of these. Bcrypt, for example, is a hashing algorithm that includes the use of unique salts per-hash by default.

There are many insecure encryption and hashing algorithms currently in use that should be upgraded to stronger methods. NIST recommends the following upgrades:

Depreciated encryption/hashing includes:

SHA-1

1024-bit RSA or DSA

160-bit ECDSA (elliptic curves)

80/112-bit 2TDEA (two key triple DES)

MD5 (never was an acceptable algorithm)

For security through the year 2030, NIST recommends at least SHA-224, 2048 bits for RSA or DSA, 224-bit EDCSA, and AES-128 or 3-key triple-DES be used.

Password Storage Locations and Methods

Many locations and methods of password storage are typically insecure by default. The following lists some higher profile and more common insecure methods of password storage. Ensure the vulnerabilities are patched, are not using the processes, and are alerting on the possible implementation of the items listed.

-

A high-profile Linux vulnerability in 2015 with the Grand Unified Bootloader (grub2) allowed physical password bypass by pressing the backspace button 28 times in a row. Grub2, which is used by most Linux systems to boot the operating system when the PC starts, would then display a rescue shell allowing unauthenticated access to the computer and the ability to load another environment.

-

Set proper authentication settings in MS Group Policy. The default GPO settings have the LM hash enabled, which is easily cracked:

-

Navigate to Computer Configuration→Policies→Windows Settings→Local Policies→Security Options.

-

Enable the setting “Network Security: Do not store LAN Manager hash value on next password change.”

-

Navigate to Computer Configuration→Policies→Windows Settings→Local Policies→Security Options.

-

Enable the setting “Network Security: LAN Manager Authentication Level” and set it to “Send NTLM response only.”

-

Navigate to Computer Configuration→Policies→Windows Settings→Local Policies→Security Options.

-

Enable the setting “Network Security: LAN Manager Authentication Level” and set it to “Send NTLMv2 response only\refuse LM.”

-

-

A well-known vulnerability within Windows is the ability to map an anonymous connection (null session) to a hidden share called IPC$. The IPC$ share is designed to be used by processes only; however, an attacker is able to gather Windows host configuration information, such as user IDs and share names, and edit parts of the remote computer’s registry.

-

For Windows NT and Windows 2000 systems navigate to HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE → SYSTEM → CurrentControlSet → Control → LSA → RestrictAnonymous.

-

Set to “No Access without Explicit Anonymous Permissions.” This high-security setting prevents null session connections and system enumeration.

-

Baseboard Management Controllers (BMCs), also known as Integrated Lights Out (ILO) cards, are a type of embedded computer used to provide out-of-band monitoring for desktops and servers. They are used for remote access to servers for controlling the hardware settings and status without having physical access to the device itself. The card provides system administrators the ability to connect through a web browser as long as the unit has power running to it. The ILO allows the powering on of the device, changing settings, and remote connection into the desktop of the OS. Often, the default password on the cards are not changed.

The protocol that BMC/ILOs use is also extremely insecure. Intelligent Platform Management Interface (IPMI) by default has often used v1 of the protocol and has cipher suite zero enabled, which permits logon as an administrator without requiring a password. So not only should default passwords be of concern, so should taking steps to protect against this critical vulnerability by upgrading the ILOs to v2 or greater and changing default passwords. There are specific modules in Metasploit that will allow scanning of the network for ILO cards with vulnerabilities (the Metasploit scanner in this case is auxiliary/scanner/ipmi/).

As covered in Chapter 14 using centralized authentication when possible, such as Active Directory, TACACS+, or Radius, will allow you to have less overall instances of password storage to keep track of.

Password Security Objects

In Windows Server 2008, Microsoft introduced the capability to implement fine-grained password policies (FGPP). Using FGPP can be extremely beneficial to control more advanced and detailed password strength options. There are some cases when certain users or groups will require different password restrictions and options, which can be accomplished by employing them.

Setting a Fine-Grained Password Policy

Warning

Fine-grained password policies can be difficult to set up and manage, so it is important that a long-term plan is created for deploying them.

Some important prerequisites and restrictions to setting a fine-grained password policy include the following:

- The domain must be Windows Server 2008 Native Mode. This means all domain controllers must be running Windows Server 2008 or later.

- Fine-grained password policies can only be applied to user objects and global security groups (not computers).2

Note

If an Automatic Shadow Group is set up, password policies can be applied automatically to any users located in an OU.

To create a password security object (PSO), follow these steps:

-

Under Administrator Tools, open ADSI Edit and connect it to a domain and domain controller where the new password policy will be set up.

Note

If this option does not appear, go to “Turn Windows Features On or Off” and make sure the “AD DS and AD LDS Tools” are installed.

Note

PSOs can also be created with LDIFDE as well as ADSI Edit. However, these instructions are for ADSI Edit.

-

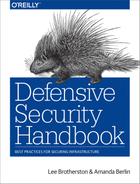

Double-click the “CN=DomainName”, then double-click “CN=Password Settings Container”, as shown in Figure 13-1.

Figure 13-1. ADSI Edit

-

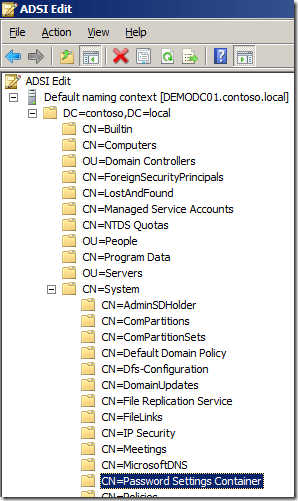

As shown in Figure 13-2, right-click “CN=Password Settings Container”. Click “New” and then “Object…”

Figure 13-2. Creating a new object

-

Click Next.

-

Type the name of the PSO in the Value field and then click Next.

-

Set ms.DS-PasswordSettingsPrecedence to 10. This is used if users have multiple Password Settings Object (PSO) applied to them.

-

Set msDS-PasswordReversibleEncryptionEnabled to FALSE.

Note

You should almost never use TRUE for this setting.

-

Set msDS-PasswordHistoryLength to 24, This will be the number of passwords that are remembered and not able to be reused.

-

Set msDS-PasswordComplexityEnabled to TRUE.

-

Set msDS-MinimumPasswordLength to 8.

-

Set msDS-MinimumPasswordAge to 1:00:00:00. This dictates the earliest a password can be modified with a format of DD:HH:MM:SS.

-

Set msDS-MaxiumumPasswordAge to 30:00:00:00. This dictates the oldest a password can be. This will be the password reset age.

-

Set msDS-LockoutThreshold to 3 to specify how many failed logins will lock an account.

-

Set msDS-LockoutObservationWindow to 0:00:30:00. This value specifies how long the invalid login attempts are tracked. In this example, if four attempts are made over 30 minutes, the counter will reset 30 minutes after the last failed attempt and the counter of failed attempts returns to 0.

-

Set msDS-LockoutDuration to 0:02:00:00. This identifies how long a user remains locked out once the msDS-LockoutThreshold is met.

-

Click Finish.

-

The Password Settings Object (PSO) has now been created and the ADSIEdit tool can be closed. Now to apply the PSO to a users or group:

- Open Active Directory Users and Computers and navigate to System→Password Settings Container.

Note

Advanced Mode needs to be enabled.

-

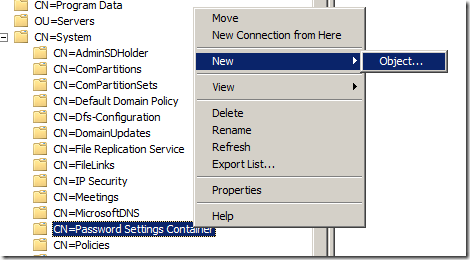

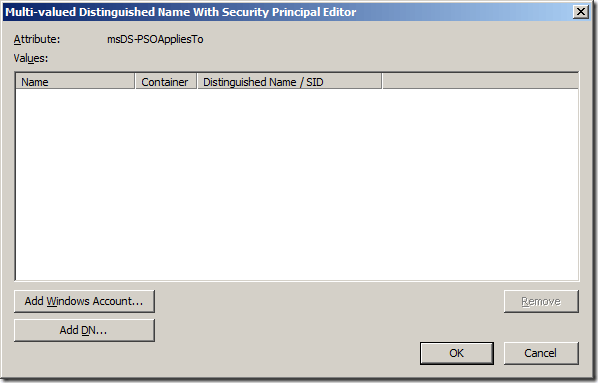

Double-click the PSO that has been created, then click the Attribute Editor tab. Select the msDS-PSOAppliedTo attribute and click Edit, as shown in Figure 13-3.

Figure 13-3. msDS-PSOAppliedTo attribute

-

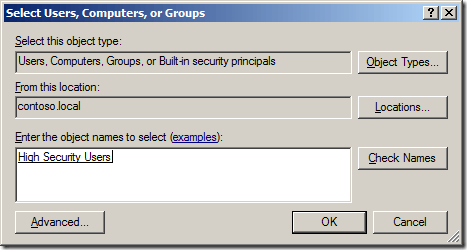

Click the Add Windows Account button (Figure 13-4).

Figure 13-4. Adding a Windows account

-

Select the user or group this PSO will be applied to and click OK, as in Figure 13-5.

Figure 13-5. Selecting user or group for the PSO

Multifactor Authentication

Multifactor Authentication (MFA) or two-factor authentication (2FA) uses two separate methods to identify individuals. 2FA is not a new concept. It is a technology patented in 1984 that provides identification of users by means of the combination of two different components. It was patented by Kenneth P. Weiss and has been slowly gaining popularity throughout the years. Some of the first widely adopted methods of 2FA were the card and PIN at ATMs. Now that the need to protect so many digital assets has grown, we are struggling to implement it in environments and with software that may or may not be backward compatible.

Why 2FA?

Basically, password strength doesn’t matter in the long run. Passwords are no longer enough when it comes to the sheer volume and sensitive nature of the data we have now in cyberspace. With the computing power of today, extensive botnets that are dedicated to password cracking, and constant breaches, you can no longer rely on only a password to protect the access you have. So why compromise when it comes to the security of data, access to systems, or the possibility of giving an attacker a foothold into corporate infrastructure? On top of doing your best to increase password complexity, 2FA is an essential part of a complete defense strategy—not just a bandaid for a compliance checkmark.

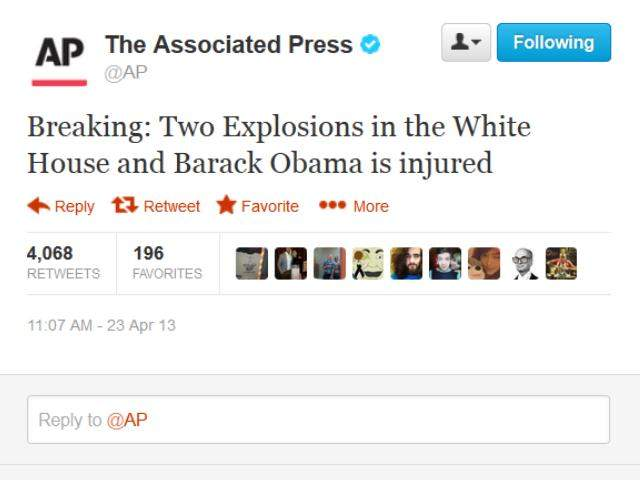

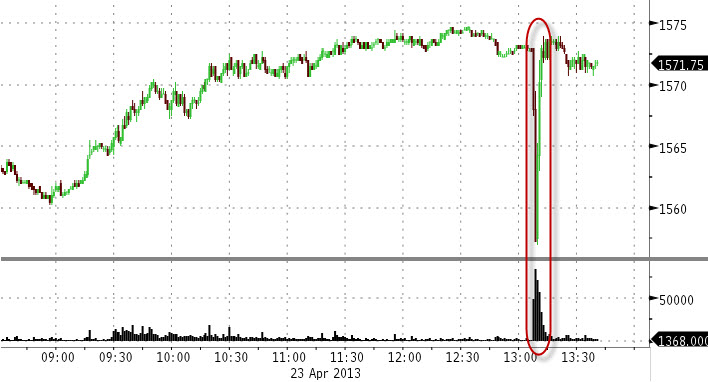

While the number of services and websites that provide 2FA is increasing, we rarely think about it in our own enterprise environments. A surprising number of companies and services decide to implement 2FA only after a large-scale or high-visibility breach. Figure 13-6 shows the widely known AP Twitter hack that brought the stock market down in April 2013 (Figure 13-7). Twitter started offering 2FA in August of that same year, less than four months later. While it can be argued that this specific hack, being a phishing attack, may have occurred regardless, it is still likely that 2FA could have lended a hand in preventing it. In the J.P. Morgan breach, the names, addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses of 83 million account holders were exposed in one one of the biggest data security breaches in history. J.P. Morgan’s major mistake? The attackers had gotten a foothold on an overlooked server that didn’t have two-factor authentication enabled.

Figure 13-6. False tweet from the hacked @AP Twitter account

Figure 13-7. The stock market crash after the tweet

2FA Methods

There are three different methods of authentication to consider when implementing a type of 2FA:

-

Something you know, such as a password, passphrase, pattern, or PIN. This is current the standard when it comes to single authentication.

-

Something you have, which would be a physical device that you would carry on you, in your wallet, or even on a keychain. These physical devices can come in the form of a token, a card with a magnetic strip, an RFID card, or your phone, which could use SMS, push notifications through an application, or even a phone call. Some popular options are the RSA tokens, yubikeys, Duo Security, or Google Authenticator.

-

Something you are. A biometric reading of a unique part of your body, such as your fingerprint or retina, or even your voice signature.

These are all methods of authentication that you and only you should be in possession of.

How It Works

2FA is based on several standards. The Initiative for Open Authentication (OAUTH) was created in 2004 to facilitate collaboration among strong authentication technology providers. It has identified HOTP (hash-based one-time passwords), TOTP (time-based one-time passwords), and U2F (Universal 2nd factor) as the appropriate standards. They are used as out-of-band authentication (OOBA) wher, for example, the first factor would traverse the local network and the secondary factor would then be performed over the internet or a cellphone connection. Providing different channels for the authentication methods significantly increases the difficulty for attackers to gain authenticated access to the network or devices.

Threats

There are various ways that 2FA may fail to be the necessary security blanket, especially when it comes to poor implementation.

Company A decides that it wants to implement 2FA by using the push notification or phone call method. A criminal or pentester comes along to break in by either phishing, using passwords from a recent breach, or a password brute-forcing technique. Somehow they end up with a legitimate username/password combo, but they should be stopped from authenticating because of the 2FA, right? Well in this case, the user gets the phone call or application alert that they have gotten so many times in the past. This notification doesn’t tell the user what they are supposedly logging in to, so as a force of habit they acknowledge the alert or answer the phone call and press the # key. Boom, the bad guy or pentester is in. There have also been case studies where attackers have used password reset options to bypass 2FA. It all boils down to how the implementation has been designed.

So the principle idea behind “something you have” can take on different forms. In this situation it’s technically 2FA, and allows Company A to be compliant but it is still not leveraging the security potential of the software. If Company A were to have that second form of authentication include a code as opposed to a single click or button, it would have been both secure and compliant.

There are many other threats that we won’t get into right now. The bottom line is that passwords alone are weak, and adding 2FA strengthens that authentication method to be more secure. In the words of Bruce Schneier:

Two-factor authentication isn’t our savior. It won’t defend against phishing. It’s not going to prevent identity theft. It’s not going to secure online accounts from fraudulent transactions. It solves the security problems we had ten years ago, not the security problems we have today.

Two-Factor Authentication is just another piece of the security puzzle. It’s not our savior for sure, but it is an essential part of defense in depth.

Where It Should Be Implemented

2FA is here to stay and can significantly increase network security. We recommend that it be implemented wherever possible. If there is any type of remote access in your organization, such as VPNs, portals, or email access, 2FA should be used as part of the authentication. And not just for administrators, but vendors, employees, consultants—everyone. By implementing a solution in an organization, remote and local access to firewalls, servers, applications, and critical infrastructure can be secured. Your data is worth protecting. We also suggest that you use it on a personal level for your home accounts such as email, social media, banking, and other services, where offered.

Conclusion

As much as we hear that passwords are dead, password management will be a necessary evil for a long time to come, so securing them as much as possible will be in your best interest. Many security topics can lead you down a never-ending rabbit hole, and password security and cryptology are no different. Here are some great references if you would like to know more about the inner workings of password storage and cryptography:

-

Password Storage Cheat Sheet, Cryptographic Storage Cheat Sheet

-

Kevin Wall’s Signs of broken auth (& related posts)

-

John Steven’s Securing password digests

-

Open Wall’s Password security: past, present, future

These should provide some additional insight for anyone interested in more in-depth cryptography.