Chapter 19. IDS and IPS

Intrusion detection systems (IDS) and intrusion prevention systems (IPS) provide insight into potential security events by observing activity on a network, as opposed to examining activity locally on a host as an antivirus would, for example.

By not relying on end devices and monitoring network traffic, you are able to remove the problem that a potentially compromised host is the one performing the checks, removing confidence in the integrity of the detection and alerting mechanisms.

The use of IDS and IPS also overcomes the issue that alerts may be something that is not deemed a security issue by endpoint security tools. For example, the use of legitimate file sharing technologies would most likely not be flagged by antivirus as unusual; however, if this was your financial database server, this sort of connection would certainly be worthy of investigation.

IDS and IPS are very similar technologies, with one key difference: an IDS will detect, log, and alert on traffic it deems worthy of attention, whereas an IPS will, in addition, attempt to block this traffic.

Types of IDS and IPS

IDS and IPS are terms that are sometimes used interchangeably. NIDS is often missed entirely and misclassified as some kind of antivirus, or grouped under the more general banner of IDS. Before we do anything else, let’s define what IDS, IPS, and NIDS actually are.

Network-Based IDS

Network-based IDS systems, or NIDS, typically use a network card in promiscuous mode to sniff traffic from a network and perform analysis on that traffic to determine if it is malicious or otherwise worthy of further investigation. Typically, a NIDS will sit on a span port of a switch, sometimes referred to as a mirror port, which outputs duplicate traffic to that which is passing through the switch. This allows for passive interception of all traffic without having to be inline or otherwise tamper with traffic in order to make it visible. This also allows the simultaneous monitoring of multiple ports via a single port.

Alternatively, an Ethernet Tap (also called an Ethertap) can be used. An Ethertap is a device placed inline on an Ethernet cable and provides “tap” ports. The device typically has four ports, two of which are used to place the device inline on the cable that is being tapped, and two of which are used for passive tapping, one for inbound traffic and one for outbound traffic.

Typically, a NIDS will have some form of signature or fingerprint that it uses to detect potentially malicious traffic. In many cases this will not be too dissimilar to a regular expression for network traffic. The bulk of most signatures are based on the contents of the packet payload, although other parameters such as IP and TCP header information are often used as well. For example, some IDS signatures may trigger based on a known bad IP address, such as a malware command and control node appearing in network traffic.

Commercial NIDS platforms can be expensive and are often based on open source NIDS solutions with the added benefit of commercial support, hardware warranties, and service-level agreements. However, if you are working on a tight budget, the open source versions can be made to serve your needs quite nicely. The three most popular open source NIDS tools are Snort, Suricata, and Bro, all of which run on standard hardware with open source operating systems such as Linux. Additionally, the Security Onion is a Linux distribution that contains all of these tools and more, in one convenient location.

Snort is probably the most widely known, most mature, and most well documented platform, and it has many signatures available for free online. However, Snort is also lacking some features of the other available options. Suricata supports Snort fingerprints and so can benefit from the wealth of data available for it, but also has better support for multithreaded operation. Multithreaded operation provides performance improvements for hardware platforms with multiple cores or processors, which in modern computing is most of them. Bro does not use a signature language; rather, it takes the approach of general network analysis with pluggable scripts. In many ways it is a more general-use network analysis tool than a strict NIDS; however, a network-based IDS is still the most popular use for Bro.

Host-Based IDS

A Host-Based IDS (HIDS) is a software-only solution that is deployed directly to the host it is monitoring. Typically, a HIDS will be deployed to many hosts rather than a few key monitoring points like a NIDS. This brings both advantages and disadvantages over NIDS. A compromised host can mask its activities from software running on that host, and so it is technically possible to blind a HIDS after compromise. However, a HIDS has an advantage over NIDS insofar as it has access to additional data, such as locally held logfiles and process information, which can be used to make determinations about activity and does not have to rely solely upon observed network traffic.

Two of the most popular open source HIDS systems are OSSEC and Samhain.

Both focus on data from local artifacts such as logfiles and file integrity monitoring, as well as various techniques for rootkit detection and other indicators of malicious activity locally. Neither attempt to monitor network traffic—that task is assumed to be handled by a NIDS or IPS.

IPS

An intrusion prevention system (IPS) typically works very much like a NIDS, except that instead of passively monitoring traffic it is itself a routing device with multiple interfaces. It is placed inline to allow the blocking of connections it deems malicious or against policy. It can be considered very much like a firewall, except that the decision to block or not is based upon matching signatures, as opposed to the IP addresses and ports commonly used by a firewall. There are some IPS solutions that are not inline and function like an IDS, except they inject reset packets into TCP streams in order to attempt to reset and close the connection. This avoids having to insert an inline device; however, it is not a hard block and can be circumvented in certain circumstances by someone who knows of this technique.

The most popular open source IPS system is probably Snort with “active response” mode enabled, which sends TCP RST packets to connections that trigger on a signature and thus attempt to cause the connection to reset and drop.

Cutting Out the Noise

Running an IDS or IPS with its default configuration typically generates an excess of alerts, far more than anyone would want to manage. Unless you are already used to dealing with telemetry data with any kind of volume, it is entirely likely that you will soon suffer from alert fatigue and cease to act on, or even notice, alerts. This is far from ideal.

The essence of being able to keep the number of alerts low enough to manage is to determine your purpose in deploying an IDS or IPS to start with. Is it to catch exploits coming from the internet toward your web server, to catch members of staff using unauthorized messaging clients, or to discover malware activity? By keeping your goals in mind you can quickly make decisions about which alerts you can remove until you have a manageable set.

The source of the volume comes from two main sources: false positives, and alerts on events that naturally occur frequently. By cutting down on these two groups of alerts, you will be able to keep the number of incidents that require investigation to a minimum and make better use of the data.

What to Log

Logs and alerts with no one looking at them may as well not exist for any reason other than historic record. It is better to alert on a few key items and actually act on them, than to alert on everything and ignore most of them.

False positives can be dealt with using a few different approaches. The simplest one is to simply remove the signature in question. This brings the obvious benefit of instantly stopping all those false positives. This approach should be tempered with losing visibility of whatever the alert was meant to highlight in the first place. This may be unacceptable to you, or it could be merely collateral damage.

If your IDS/IPS permits you to create your own rules or edit existing rules, it may be possible to refine the rule to remove the false positive without stopping the original event from being missed. Of course, this is very specific to the rule in question. Prime examples of where a rule can be improved are setting a specific offset for the pattern-matching portion of the rule (see the following writing signatures example), setting specific ports or IP addresses for the signature, and adding additional “not"-type parameters to filter the false positives.

Finally, if there is ample time to write some scripts, it may be possible to filter false positive–prone alerts into a separate log, as opposed to the main log. They can then be retained for historic use and to create an aggregated and summarized daily report. This way those tasked with responding to alerts will not be swamped, but the alerts will not be completely removed. Of course we should remember that the summary report will not be real time and so there could be several hours between a signature being triggered and someone investigating it.

Frequently occurring alerts that are not false positives can also clutter up logfiles and contribute to alert fatigue. It is worth remembering that just because a signature is being correctly triggered, you do not necessarily need to know about it. For example, alerting that someone is attempting a Solaris-specific exploit against your entirely FreeBSD estate may be triggering correctly, but in reality, do you care? It’s not going to do anything. Determining the answer to “do I care?” will allow you to simply trim a certain number of signatures from your configuration.

As mentioned before, if there is time to write some scripts, it may be possible to filter frequently occurring alerts into a separate log, which can be retained for historic use and be used to create an aggregated and summarized daily report. Again, those tasked with responding to alerts will not be swamped and the alerts will not be removed.

Writing Your Own Signatures

Many people opt to use the readily available repositories of signatures alone, and that is a perfectly valid strategy to use. However, the more in-depth knowledge that is gained over time about the network may lend awareness to the need of writing customized rulesets, or simply require rules that do not exist.

Let’s use an example that we encountered in real life.

Upon discovering Superfish installed on devices on our network, we wanted to ensure that there were no other devices present on the network running the application. The environment included user-owned devices—not just corporate devices—so endpoint management tools did not offer adequate coverage. After taking multiple packet dumps of communication from Superfish to the internet, we noticed that although the connection was encrypted, the TLS handshake was unique to this application and remained constant. These two criteria are the hallmarks of a good signature.

Let’s start with a very minimal signature.

We will use the Snort signature language in this section, as it is supported by both Snort and Suricata and is therefore the most likely format that you will encounter:

alert tcp any any -> any 443 (msg:"SuperFish Test Rule"; sid:1000004; rev:1;)

This rule will match packets that are TCP with a destination port of 443, with any source or destination IP address. The msg parameter is what will be logged in the logfiles, the sid is the unique ID of the rule, and the rev is the revision, which is used to track changes to the rule in subsequent versions of the signature files.

The first order of business is to capture the unique portion of the data—the larger, the better—to reduce the risk of accidentally triggering on other partially matching traffic. To illustrate, when searching a dictionary for the word “thesaurus,” we could find matches with the search “t”, “the”, or “thesaurus”. However, “thesaurus” is the better search as it is less subject to finding false positive results than the other two search options. In this situation, the list of ciphersuites is the object of the search. In hex, this list is:

c0 14 c0 0a c0 22 c0 21 00 39 00 38 00 88 00 87 c0 0f c0 05 00 35 00 84 c0 12 c0 08 c0 1c c0 1b 00 16 00 13 c0 0d c0 03 00 0a c0 13 c0 09 c0 1f c0 1e 00 33 00 32 00 9a 00 99 00 45 00 44 c0 0e c0 04 00 2f 00 96 00 41 00 07 c0 11 c0 07 c0 0c c0 02 00 05 00 04 00 15 00 12 00 09 00 14 00 11 00 08 00 06 00 03 00 ff

Luckily the Snort rules format supports being able to search for both hex and ASCII in documents, and to do this we use the content argument. To search in hex, as opposed to ASCII, we merely wrap the hex representation in pipes. So “00” would match an ASCII 00, whereas “|00|” would match a hex 00. And so the rule becomes:

alert tcp any any -> any 443 (msg:"SuperFish Test Rule"; content:"|c0 14 c0 0a c0 22 c0 21 00 39 00 38 00 88 00 87 c0 0f c0 05 00 35 00 84 c0 12 c0 08 c0 1c c0 1b 00 16 00 13 c0 0d c0 03 00 0a c0 13 c0 09 c0 1f c0 1e 00 33 00 32 00 9a 00 99 00 45 00 44 c0 0e c0 04 00 2f 00 96 00 41 00 07 c0 11 c0 07 c0 0c c0 02 00 05 00 04 00 15 00 12 00 09 00 14 00 11 00 08 00 06 00 03 00 ff|"; sid:1000004; rev:2;)

In many cases this could be enough. Indeed, many rules that you find online will be complete at this point. However, IDS and IPS systems can generate false positives, and being able to reduce these as much as possible will make the system more effective. Other features in the language can be leveraged to improve upon this rule. First of all, we know that the list of ciphersuites occurs at a set offset from the start of the packet, in this case 44 bytes. By specifying this we can match this data only at the specified offset and so if it coincidentally appears elsewhere in a packet, a false positive will not be created. To set the offset, we use the offset parameter:

alert tcp any any -> any 443 (msg:"SuperFish Test Rule"; content:"|c0 14 c0 0a c0 22 c0 21 00 39 00 38 00 88 00 87 c0 0f c0 05 00 35 00 84 c0 12 c0 08 c0 1c c0 1b 00 16 00 13 c0 0d c0 03 00 0a c0 13 c0 09 c0 1f c0 1e 00 33 00 32 00 9a 00 99 00 45 00 44 c0 0e c0 04 00 2f 00 96 00 41 00 07 c0 11 c0 07 c0 0c c0 02 00 05 00 04 00 15 00 12 00 09 00 14 00 11 00 08 00 06 00 03 00 ff|"; offset: 44; sid:1000004; rev:3;)

Both Snort and Suricata maintain state in that they are aware of the direction that data is flowing, and so we can use the flow parameter to analyze only packets flowing from client to server. Finally, we can use reference to add a URL to be logged with further information, such as an internal wiki. We have completed our rule:

alert tcp any any -> any 443 (msg:"SuperFish Test Rule"; flow:to_server; reference:url,https://MyReferenceUrlGoesHere; content:"|c0 14 c0 0a c0 22 c0 21 00 39 00 38 00 88 00 87 c0 0f c0 05 00 35 00 84 c0 12 c0 08 c0 1c c0 1b 00 16 00 13 c0 0d c0 03 00 0a c0 13 c0 09 c0 1f c0 1e 00 33 00 32 00 9a 00 99 00 45 00 44 c0 0e c0 04 00 2f 00 96 00 41 00 07 c0 11 c0 07 c0 0c c0 02 00 05 00 04 00 15 00 12 00 09 00 14 00 11 00 08 00 06 00 03 00 ff|"; offset: 44; sid:1000004; rev:4;)

This example is not comprehensive with regards to options within the signature language. It is worth consulting the online documentation to obtain more details. The preceding process can be repeated with other options in order to create very specific rulesets for many types of traffic you may encounter on your network.

NIDS and IPS Locations

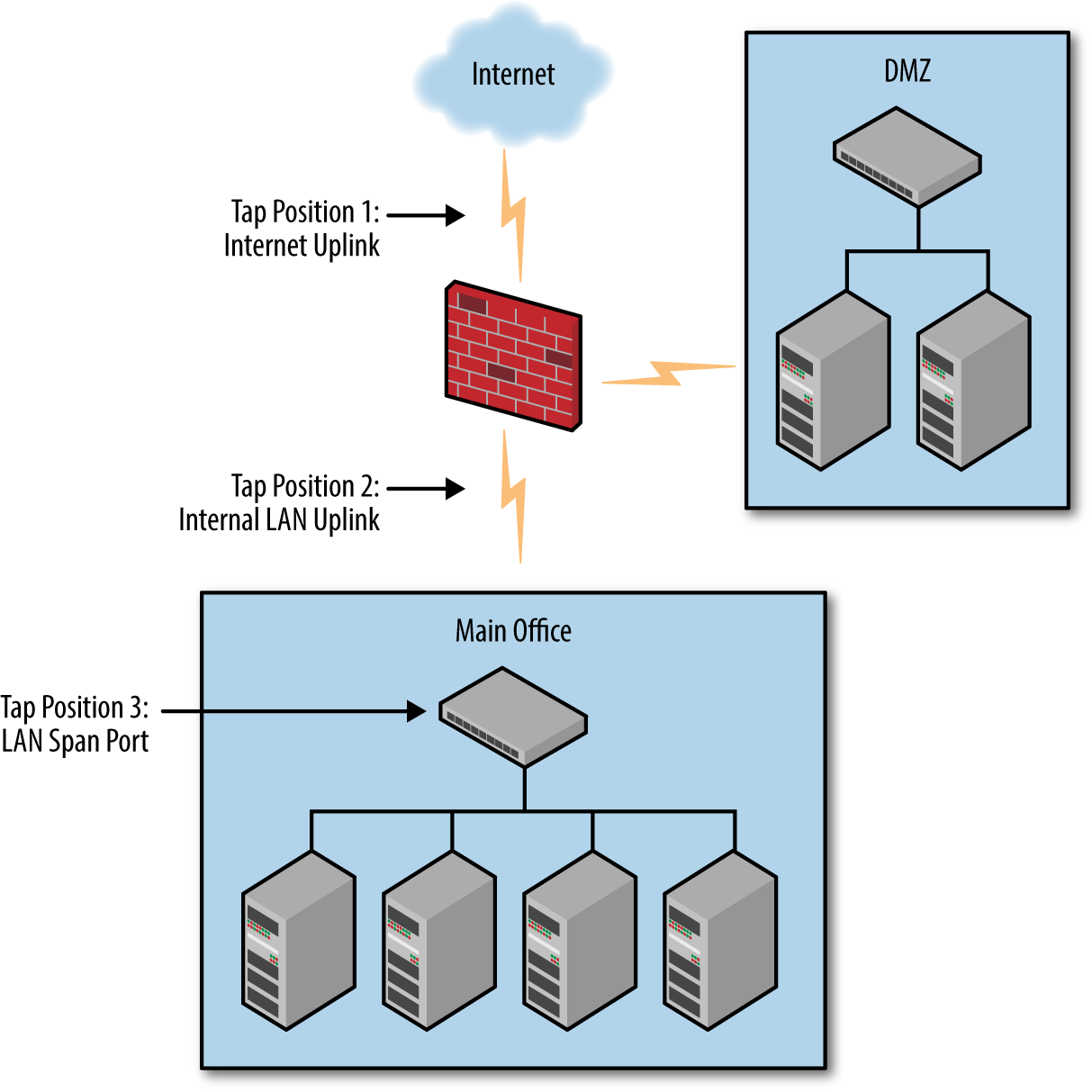

For devices that are network based, placement of the device will alter which traffic it is able to inspect and the types of attack it will block.

The typical approach to this is to place devices at key choke points in a network, typically the internet connection along with any other WAN links, such as those that may connect offices and datacenters. This way traffic that traverses those links will be analyzed and will capture the events that the majority of people are concerned about. It is worth noting that this will miss traffic that does not flow over these links. How relevant this is to you will depend on the context of your network topology and the sort of traffic that you would like to receive alerts on.

In the example shown in Figure 19-1, Tap Position 1 will capture all traffic between a corporate network and the internet, in theory capturing attacks that are incoming from the internet and unwanted connections leaving the environment. However, it will be blind to any traffic within the networks. In Tap Position 2, all traffic between the internal LAN and the internet, and the internal LAN and the DMZ will be analyzed, providing some insight to internal traffic as well as some internet traffic; but it is blind to traffic between the DMZ and the internet. Tap 3 is completely blind to traffic other than that which starts or ends on the internal LAN, but will have visibility of all internal traffic between workstations and internal servers, for example.

Figure 19-1. Proper IDS/IPS network positioning

Of course, which is most relevant to any environment will depend on the specific configuration, the areas considered to be most valuable, and the areas that are more likely to be attacked. In a perfect IDS/IPS world, network taps would be deployed throughout; however, in reality cost is likely to mean that a decision should be made as to which are the most useful links to monitor.

Encrypted Protocols

Network-based IDS and IPS technologies analyze data as it is transmitted across the network and do not have access to the data on either endpoint. This means that unless provided with the keying material to decrypt an encrypted session, they are effectively blinded to the payload content of encrypted communications.

Many classes of attack will be missed due to this lack of visibility. An exploit against a vulnerable script in some widely available blogging software, for example, would be missed as the exploit is hidden within an encrypted connection. The IDS and IPS are only able to detect attacks that can be found based on the unencrypted portions of the communications—for example, HeartBleed.

This vulnerability was present in the unencrypted handshake of TLS connections, not the encrypted payload. Additionally, signatures that are based on other data, such as IP addresses and port numbers, will continue to work. There are some emerging tools and techniques that can be used to lessen this effect, but they are not in as widespread use as standard IDS and IPS technologies.

FingerprinTLS, for example, can be used to determine which client has initiated an encrypted connection. This can provide an additional level of understanding of encrypted traffic by offering the indicator of knowing if traffic originated from a browser, script, or penetration testing tool.

Conclusion

Both IDS and IPS solutions are a useful part of the information security arsenal. Vendor selection, device placement, and configuration are all important technology decisions, but ensuring that logs are collected and a process is in place to handle any alerts is critical. Collecting data that no one looks at achieves very little.

IDS and IPS are not a panacea. Detection is limited to traffic with a defined signature and they are blind to encrypted protocols, for the most part. They should be used as part of your larger security strategy.