Chapter 11. Time Series

Time series data is an important form of structured data in many different fields, such as finance, economics, ecology, neuroscience, and physics. Anything that is observed or measured at many points in time forms a time series. Many time series are fixed frequency, which is to say that data points occur at regular intervals according to some rule, such as every 15 seconds, every 5 minutes, or once per month. Time series can also be irregular without a fixed unit of time or offset between units. How you mark and refer to time series data depends on the application, and you may have one of the following:

Fixed periods, such as the month January 2007 or the full year 2010

Intervals of time, indicated by a start and end timestamp. Periods can be thought of as special cases of intervals

Experiment or elapsed time; each timestamp is a measure of time relative to a particular start time (e.g., the diameter of a cookie baking each second since being placed in the oven)

In this chapter, I am mainly concerned with time series in the first three categories, though many of the techniques can be applied to experimental time series where the index may be an integer or floating-point number indicating elapsed time from the start of the experiment. The simplest and most widely used kind of time series are those indexed by timestamp.

Tip

pandas also supports indexes based on timedeltas, which can be a useful way of representing experiment or elapsed time. We do not explore timedelta indexes in this book, but you can learn more in the pandas documentation.

pandas provides many built-in time series tools and data algorithms. You can efficiently work with very large time series and easily slice and dice, aggregate, and resample irregular- and fixed-frequency time series. Some of these tools are especially useful for financial and economics applications, but you could certainly use them to analyze server log data, too.

11.1 Date and Time Data Types and Tools

The Python standard library includes data types for date and time data, as well

as calendar-related functionality. The datetime, time, and calendar modules are the main places to start. The datetime.datetime type, or simply datetime, is widely used:

In[10]:fromdatetimeimportdatetimeIn[11]:now=datetime.now()In[12]:nowOut[12]:datetime.datetime(2017,10,17,13,34,33,597499)In[13]:now.year,now.month,now.dayOut[13]:(2017,10,17)

datetime stores both the

date and time down to the microsecond. timedelta represents the temporal difference

between two datetime objects:

In[14]:delta=datetime(2011,1,7)-datetime(2008,6,24,8,15)In[15]:deltaOut[15]:datetime.timedelta(926,56700)In[16]:delta.daysOut[16]:926In[17]:delta.secondsOut[17]:56700

You can add (or subtract) a timedelta or multiple thereof to a datetime object to yield a new shifted

object:

In[18]:fromdatetimeimporttimedeltaIn[19]:start=datetime(2011,1,7)In[20]:start+timedelta(12)Out[20]:datetime.datetime(2011,1,19,0,0)In[21]:start-2*timedelta(12)Out[21]:datetime.datetime(2010,12,14,0,0)

Table 11-1 summarizes the data types

in the datetime module. While this

chapter is mainly concerned with the data types in pandas and higher-level

time series manipulation, you may encounter the datetime-based types in many other places in

Python in the wild.

Converting Between String and Datetime

You can format datetime objects and pandas Timestamp

objects, which I’ll introduce later, as strings

using str or the

strftime method, passing a format

specification:

In[22]:stamp=datetime(2011,1,3)In[23]:str(stamp)Out[23]:'2011-01-03 00:00:00'In[24]:stamp.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')Out[24]:'2011-01-03'

See Table 11-2 for a complete list of the format codes (reproduced from Chapter 2).

You can use these same format codes to convert strings to dates

using datetime.strptime:

In[25]:value='2011-01-03'In[26]:datetime.strptime(value,'%Y-%m-%d')Out[26]:datetime.datetime(2011,1,3,0,0)In[27]:datestrs=['7/6/2011','8/6/2011']In[28]:[datetime.strptime(x,'%m/%d/%Y')forxindatestrs]Out[28]:[datetime.datetime(2011,7,6,0,0),datetime.datetime(2011,8,6,0,0)]

datetime.strptime is a good way

to parse a date with a known format. However, it can be a bit annoying

to have to write a format spec each time, especially for common date

formats. In this case, you can use the parser.parse method in the third-party dateutil

package (this is installed automatically when you install pandas):

In[29]:fromdateutil.parserimportparseIn[30]:parse('2011-01-03')Out[30]:datetime.datetime(2011,1,3,0,0)

dateutil is capable of parsing

most human-intelligible date representations:

In[31]:parse('Jan 31, 1997 10:45 PM')Out[31]:datetime.datetime(1997,1,31,22,45)

In international locales, day appearing before month is very

common, so you can pass dayfirst=True

to indicate this:

In[32]:parse('6/12/2011',dayfirst=True)Out[32]:datetime.datetime(2011,12,6,0,0)

pandas is generally oriented toward working with arrays of dates,

whether used as an axis index or a column in a DataFrame. The to_datetime method parses many different kinds of date representations.

Standard date formats like ISO 8601 can be parsed very quickly:

In[33]:datestrs=['2011-07-06 12:00:00','2011-08-06 00:00:00']In[34]:pd.to_datetime(datestrs)Out[34]:DatetimeIndex(['2011-07-06 12:00:00','2011-08-06 00:00:00'],dtype='datetime64[ns]', freq=None)

It also handles values that should be considered missing (None, empty string, etc.):

In[35]:idx=pd.to_datetime(datestrs+[None])In[36]:idxOut[36]:DatetimeIndex(['2011-07-06 12:00:00','2011-08-06 00:00:00','NaT'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq=None)In[37]:idx[2]Out[37]:NaTIn[38]:pd.isnull(idx)Out[38]:array([False,False,True],dtype=bool)

NaT (Not a Time) is pandas’s null value for timestamp data.

Caution

dateutil.parser is a useful

but imperfect tool. Notably, it will recognize some strings as dates

that you might prefer that it didn’t—for example, '42' will be parsed as the year 2042 with today’s calendar date.

datetime objects also have a

number of locale-specific formatting options for systems in other

countries or languages. For example, the abbreviated month names will be

different on German or French systems compared with English systems. See

Table 11-3 for a

listing.

11.2 Time Series Basics

A basic kind of time series object in pandas is a Series indexed by

timestamps, which is often represented external to pandas as

Python strings or datetime

objects:

In[39]:fromdatetimeimportdatetimeIn[40]:dates=[datetime(2011,1,2),datetime(2011,1,5),....:datetime(2011,1,7),datetime(2011,1,8),....:datetime(2011,1,10),datetime(2011,1,12)]In[41]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(6),index=dates)In[42]:tsOut[42]:2011-01-02-0.2047082011-01-050.4789432011-01-07-0.5194392011-01-08-0.5557302011-01-101.9657812011-01-121.393406dtype:float64

Under the hood, these datetime

objects have been put in a DatetimeIndex:

In[43]:ts.indexOut[43]:DatetimeIndex(['2011-01-02','2011-01-05','2011-01-07','2011-01-08','2011-01-10','2011-01-12'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq=None)

Like other Series, arithmetic operations between differently indexed time series automatically align on the dates:

In[44]:ts+ts[::2]Out[44]:2011-01-02-0.4094152011-01-05NaN2011-01-07-1.0388772011-01-08NaN2011-01-103.9315612011-01-12NaNdtype:float64

Recall that ts[::2] selects every second element

in ts.

pandas stores timestamps using NumPy’s datetime64 data

type at the nanosecond resolution:

In[45]:ts.index.dtypeOut[45]:dtype('<M8[ns]')

Scalar values from a DatetimeIndex are pandas Timestamp

objects:

In[46]:stamp=ts.index[0]In[47]:stampOut[47]:Timestamp('2011-01-02 00:00:00')

A Timestamp can be substituted

anywhere you would use a datetime

object. Additionally, it can store frequency information (if any) and

understands how to do time zone conversions and other kinds of

manipulations. More on both of these things later.

Indexing, Selection, Subsetting

Time series behaves like any other pandas.Series

when you are indexing and selecting data based on label:

In[48]:stamp=ts.index[2]In[49]:ts[stamp]Out[49]:-0.51943871505673811

As a convenience, you can also pass a string that is interpretable as a date:

In[50]:ts['1/10/2011']Out[50]:1.9657805725027142In[51]:ts['20110110']Out[51]:1.9657805725027142

For longer time series, a year or only a year and month can be passed to easily select slices of data:

In[52]:longer_ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(1000),....:index=pd.date_range('1/1/2000',periods=1000))In[53]:longer_tsOut[53]:2000-01-010.0929082000-01-020.2817462000-01-030.7690232000-01-041.2464352000-01-051.0071892000-01-06-1.2962212000-01-070.2749922000-01-080.2289132000-01-091.3529172000-01-100.886429...2002-09-17-0.1392982002-09-18-1.1599262002-09-190.6189652002-09-201.3738902002-09-21-0.9835052002-09-220.9309442002-09-23-0.8116762002-09-24-1.8301562002-09-25-0.1387302002-09-260.334088Freq:D,Length:1000,dtype:float64In[54]:longer_ts['2001']Out[54]:2001-01-011.5995342001-01-020.4740712001-01-030.1513262001-01-04-0.5421732001-01-05-0.4754962001-01-060.1064032001-01-07-1.3082282001-01-082.1731852001-01-090.5645612001-01-10-0.190481...2001-12-220.0003692001-12-230.9008852001-12-24-0.4548692001-12-25-0.8645472001-12-261.1291202001-12-270.0578742001-12-28-0.4337392001-12-290.0926982001-12-30-1.3978202001-12-311.457823Freq:D,Length:365,dtype:float64

Here, the string '2001' is interpreted as a

year and selects that time period. This also works if you specify the

month:

In[55]:longer_ts['2001-05']Out[55]:2001-05-01-0.6225472001-05-020.9362892001-05-030.7500182001-05-04-0.0567152001-05-052.3006752001-05-060.5694972001-05-071.4894102001-05-081.2642502001-05-09-0.7618372001-05-10-0.331617...2001-05-220.5036992001-05-23-1.3878742001-05-240.2048512001-05-250.6037052001-05-260.5456802001-05-270.2354772001-05-280.1118352001-05-29-1.2515042001-05-30-2.9493432001-05-310.634634Freq:D,Length:31,dtype:float64

Slicing with datetime objects works as

well:

In[56]:ts[datetime(2011,1,7):]Out[56]:2011-01-07-0.5194392011-01-08-0.5557302011-01-101.9657812011-01-121.393406dtype:float64

Because most time series data is ordered chronologically, you can slice with timestamps not contained in a time series to perform a range query:

In[57]:tsOut[57]:2011-01-02-0.2047082011-01-050.4789432011-01-07-0.5194392011-01-08-0.5557302011-01-101.9657812011-01-121.393406dtype:float64In[58]:ts['1/6/2011':'1/11/2011']Out[58]:2011-01-07-0.5194392011-01-08-0.5557302011-01-101.965781dtype:float64

As before, you can pass either a string date, datetime, or

timestamp. Remember that slicing in this manner produces views on the

source time series like slicing NumPy arrays. This means that no data is

copied and modifications on the slice will be reflected in the original

data.

There is an equivalent instance method, truncate, that slices a Series between two dates:

In[59]:ts.truncate(after='1/9/2011')Out[59]:2011-01-02-0.2047082011-01-050.4789432011-01-07-0.5194392011-01-08-0.555730dtype:float64

All of this holds true for DataFrame as well, indexing on its rows:

In[60]:dates=pd.date_range('1/1/2000',periods=100,freq='W-WED')In[61]:long_df=pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(100,4),....:index=dates,....:columns=['Colorado','Texas',....:'New York','Ohio'])In[62]:long_df.loc['5-2001']Out[62]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2001-05-02-0.0060450.490094-0.277186-0.7072132001-05-09-0.5601072.7355270.9273351.5139062001-05-160.5386001.2737680.667876-0.9692062001-05-231.676091-0.8176490.0501881.9513122001-05-303.2603830.9633011.201206-1.852001

Time Series with Duplicate Indices

In some applications, there may be multiple data observations falling on a particular timestamp. Here is an example:

In[63]:dates=pd.DatetimeIndex(['1/1/2000','1/2/2000','1/2/2000',....:'1/2/2000','1/3/2000'])In[64]:dup_ts=pd.Series(np.arange(5),index=dates)In[65]:dup_tsOut[65]:2000-01-0102000-01-0212000-01-0222000-01-0232000-01-034dtype:int64

We can tell that the index is not unique by checking its is_unique

property:

In[66]:dup_ts.index.is_uniqueOut[66]:False

Indexing into this time series will now either produce scalar values or slices depending on whether a timestamp is duplicated:

In[67]:dup_ts['1/3/2000']# not duplicatedOut[67]:4In[68]:dup_ts['1/2/2000']# duplicatedOut[68]:2000-01-0212000-01-0222000-01-023dtype:int64

Suppose you wanted to aggregate the data having non-unique

timestamps. One way to do this is to use groupby and pass level=0:

In[69]:grouped=dup_ts.groupby(level=0)In[70]:grouped.mean()Out[70]:2000-01-0102000-01-0222000-01-034dtype:int64In[71]:grouped.count()Out[71]:2000-01-0112000-01-0232000-01-031dtype:int64

11.3 Date Ranges, Frequencies, and Shifting

Generic time series in pandas are assumed to be irregular; that is,

they have no fixed frequency. For many applications this is sufficient.

However, it’s often desirable to work relative to a fixed frequency, such

as daily, monthly, or every 15 minutes, even if that means introducing

missing values into a time series. Fortunately pandas has a full suite of

standard time series frequencies and tools for resampling, inferring

frequencies, and generating fixed-frequency date ranges. For example, you can convert the sample time series to be fixed daily frequency by calling resample:

In[72]:tsOut[72]:2011-01-02-0.2047082011-01-050.4789432011-01-07-0.5194392011-01-08-0.5557302011-01-101.9657812011-01-121.393406dtype:float64In[73]:resampler=ts.resample('D')

The string 'D' is interpreted as daily

frequency.

Conversion between frequencies or resampling is a big enough topic to have its own section later ( Section 11.6, “Resampling and Frequency Conversion,”). Here I’ll show you how to use the base frequencies and multiples thereof.

Generating Date Ranges

While I used it previously without explanation, pandas.date_range is responsible for generating a DatetimeIndex with an

indicated length according to a particular frequency:

In[74]:index=pd.date_range('2012-04-01','2012-06-01')In[75]:indexOut[75]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-04-01','2012-04-02','2012-04-03','2012-04-04','2012-04-05','2012-04-06','2012-04-07','2012-04-08','2012-04-09','2012-04-10','2012-04-11','2012-04-12','2012-04-13','2012-04-14','2012-04-15','2012-04-16','2012-04-17','2012-04-18','2012-04-19','2012-04-20','2012-04-21','2012-04-22','2012-04-23','2012-04-24','2012-04-25','2012-04-26','2012-04-27','2012-04-28','2012-04-29','2012-04-30','2012-05-01','2012-05-02','2012-05-03','2012-05-04','2012-05-05','2012-05-06','2012-05-07','2012-05-08','2012-05-09','2012-05-10','2012-05-11','2012-05-12','2012-05-13','2012-05-14','2012-05-15','2012-05-16','2012-05-17','2012-05-18','2012-05-19','2012-05-20','2012-05-21','2012-05-22','2012-05-23','2012-05-24','2012-05-25','2012-05-26','2012-05-27','2012-05-28','2012-05-29','2012-05-30','2012-05-31','2012-06-01'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='D')

By default, date_range

generates daily timestamps. If you pass only a start or end date, you

must pass a number of periods to generate:

In[76]:pd.date_range(start='2012-04-01',periods=20)Out[76]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-04-01','2012-04-02','2012-04-03','2012-04-04','2012-04-05','2012-04-06','2012-04-07','2012-04-08','2012-04-09','2012-04-10','2012-04-11','2012-04-12','2012-04-13','2012-04-14','2012-04-15','2012-04-16','2012-04-17','2012-04-18','2012-04-19','2012-04-20'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='D')In[77]:pd.date_range(end='2012-06-01',periods=20)Out[77]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-05-13','2012-05-14','2012-05-15','2012-05-16','2012-05-17','2012-05-18','2012-05-19','2012-05-20','2012-05-21','2012-05-22','2012-05-23','2012-05-24','2012-05-25','2012-05-26','2012-05-27','2012-05-28','2012-05-29','2012-05-30','2012-05-31','2012-06-01'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='D')

The start and end dates define strict boundaries for the generated

date index. For example, if you wanted a date index containing the last

business day of each month, you would pass the 'BM' frequency (business end of month; see

more complete listing of frequencies in Table 11-4) and only dates falling on or inside

the date interval will be included:

In[78]:pd.date_range('2000-01-01','2000-12-01',freq='BM')Out[78]:DatetimeIndex(['2000-01-31','2000-02-29','2000-03-31','2000-04-28','2000-05-31','2000-06-30','2000-07-31','2000-08-31','2000-09-29','2000-10-31','2000-11-30'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='BM')

date_range by default preserves

the time (if any) of the start or end timestamp:

In[79]:pd.date_range('2012-05-02 12:56:31',periods=5)Out[79]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-05-02 12:56:31','2012-05-03 12:56:31','2012-05-04 12:56:31','2012-05-05 12:56:31','2012-05-06 12:56:31'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='D')

Sometimes you will have start or end dates with time information

but want to generate a set of timestamps normalized

to midnight as a convention. To do this, there is a normalize

option:

In[80]:pd.date_range('2012-05-02 12:56:31',periods=5,normalize=True)Out[80]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-05-02','2012-05-03','2012-05-04','2012-05-05','2012-05-06'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='D')

Frequencies and Date Offsets

Frequencies in pandas are composed of a base frequency and a multiplier.

Base frequencies are typically referred to by a string alias, like

'M' for monthly or 'H' for hourly. For each base frequency, there

is an object defined generally referred to as a date offset. For example, hourly

frequency can be represented with the Hour class:

In[81]:frompandas.tseries.offsetsimportHour,MinuteIn[82]:hour=Hour()In[83]:hourOut[83]:<Hour>

You can define a multiple of an offset by passing an integer:

In[84]:four_hours=Hour(4)In[85]:four_hoursOut[85]:<4*Hours>

In most applications, you would never need to explicitly create

one of these objects, instead using a string alias like 'H' or '4H'. Putting an integer before the base

frequency creates a multiple:

In[86]:pd.date_range('2000-01-01','2000-01-03 23:59',freq='4h')Out[86]:DatetimeIndex(['2000-01-01 00:00:00','2000-01-01 04:00:00','2000-01-01 08:00:00','2000-01-01 12:00:00','2000-01-01 16:00:00','2000-01-01 20:00:00','2000-01-02 00:00:00','2000-01-02 04:00:00','2000-01-02 08:00:00','2000-01-02 12:00:00','2000-01-02 16:00:00','2000-01-02 20:00:00','2000-01-03 00:00:00','2000-01-03 04:00:00','2000-01-03 08:00:00','2000-01-03 12:00:00','2000-01-03 16:00:00','2000-01-03 20:00:00'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='4H')

Many offsets can be combined together by addition:

In[87]:Hour(2)+Minute(30)Out[87]:<150*Minutes>

Similarly, you can pass frequency strings, like '1h30min', that will effectively be parsed to

the same expression:

In[88]:pd.date_range('2000-01-01',periods=10,freq='1h30min')Out[88]:DatetimeIndex(['2000-01-01 00:00:00','2000-01-01 01:30:00','2000-01-01 03:00:00','2000-01-01 04:30:00','2000-01-01 06:00:00','2000-01-01 07:30:00','2000-01-01 09:00:00','2000-01-01 10:30:00','2000-01-01 12:00:00','2000-01-01 13:30:00'],dtype='datetime64[ns]',freq='90T')

Some frequencies describe points in time that are not evenly

spaced. For example, 'M' (calendar

month end) and 'BM' (last

business/weekday of month) depend on the number of days in a month and,

in the latter case, whether the month ends on a weekend or not. We refer

to these as anchored offsets.

Refer back to Table 11-4 for a listing of frequency codes and date offset classes available in pandas.

Note

Users can define their own custom frequency classes to provide date logic not available in pandas, though the full details of that are outside the scope of this book.

Week of month dates

One useful frequency class is “week of month,” starting with

WOM. This enables you to get dates

like the third Friday of each month:

In[89]:rng=pd.date_range('2012-01-01','2012-09-01',freq='WOM-3FRI')In[90]:list(rng)Out[90]:[Timestamp('2012-01-20 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI'),Timestamp('2012-02-17 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI'),Timestamp('2012-03-16 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI'),Timestamp('2012-04-20 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI'),Timestamp('2012-05-18 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI'),Timestamp('2012-06-15 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI'),Timestamp('2012-07-20 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI'),Timestamp('2012-08-17 00:00:00',freq='WOM-3FRI')]

Shifting (Leading and Lagging) Data

“Shifting” refers to moving data backward and forward through time. Both Series

and DataFrame have a shift method

for doing naive shifts forward or backward, leaving the

index unmodified:

In[91]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(4),....:index=pd.date_range('1/1/2000',periods=4,freq='M'))In[92]:tsOut[92]:2000-01-31-0.0667482000-02-290.8386392000-03-31-0.1173882000-04-30-0.517795Freq:M,dtype:float64In[93]:ts.shift(2)Out[93]:2000-01-31NaN2000-02-29NaN2000-03-31-0.0667482000-04-300.838639Freq:M,dtype:float64In[94]:ts.shift(-2)Out[94]:2000-01-31-0.1173882000-02-29-0.5177952000-03-31NaN2000-04-30NaNFreq:M,dtype:float64

When we shift like this, missing data is introduced either at the start or the end of the time series.

A common use of shift is

computing percent changes in a time series or multiple time series as

DataFrame columns. This is expressed as:

ts/ts.shift(1)-1

Because naive shifts leave the index unmodified, some data is

discarded. Thus if the frequency is known, it can be passed to shift to advance the timestamps instead of

simply the data:

In[95]:ts.shift(2,freq='M')Out[95]:2000-03-31-0.0667482000-04-300.8386392000-05-31-0.1173882000-06-30-0.517795Freq:M,dtype:float64

Other frequencies can be passed, too, giving you some flexibility in how to lead and lag the data:

In[96]:ts.shift(3,freq='D')Out[96]:2000-02-03-0.0667482000-03-030.8386392000-04-03-0.1173882000-05-03-0.517795dtype:float64In[97]:ts.shift(1,freq='90T')Out[97]:2000-01-3101:30:00-0.0667482000-02-2901:30:000.8386392000-03-3101:30:00-0.1173882000-04-3001:30:00-0.517795Freq:M,dtype:float64

The T here stands for minutes.

Shifting dates with offsets

The pandas date offsets can also be used with datetime or

Timestamp objects:

In[98]:frompandas.tseries.offsetsimportDay,MonthEndIn[99]:now=datetime(2011,11,17)In[100]:now+3*Day()Out[100]:Timestamp('2011-11-20 00:00:00')

If you add an anchored offset like MonthEnd, the first increment will “roll

forward” a date to the next date according to the frequency

rule:

In[101]:now+MonthEnd()Out[101]:Timestamp('2011-11-30 00:00:00')In[102]:now+MonthEnd(2)Out[102]:Timestamp('2011-12-31 00:00:00')

Anchored offsets can explicitly “roll” dates forward or backward

by simply using their rollforward and rollback methods, respectively:

In[103]:offset=MonthEnd()In[104]:offset.rollforward(now)Out[104]:Timestamp('2011-11-30 00:00:00')In[105]:offset.rollback(now)Out[105]:Timestamp('2011-10-31 00:00:00')

A creative use of date offsets is to use these methods with

groupby:

In[106]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(20),.....:index=pd.date_range('1/15/2000',periods=20,freq='4d'))In[107]:tsOut[107]:2000-01-15-0.1166962000-01-192.3896452000-01-23-0.9324542000-01-27-0.2293312000-01-31-1.1403302000-02-040.4399202000-02-08-0.8237582000-02-12-0.5209302000-02-160.3502822000-02-200.2043952000-02-240.1334452000-02-280.3279052000-03-030.0721532000-03-070.1316782000-03-11-1.2974592000-03-150.9977472000-03-190.8709552000-03-23-0.9912532000-03-270.1516992000-03-311.266151Freq:4D,dtype:float64In[108]:ts.groupby(offset.rollforward).mean()Out[108]:2000-01-31-0.0058332000-02-290.0158942000-03-310.150209dtype:float64

Of course, an easier and faster way to do this is using resample (we’ll discuss this in much more

depth in Section 11.6, “Resampling and Frequency Conversion,”):

In[109]:ts.resample('M').mean()Out[109]:2000-01-31-0.0058332000-02-290.0158942000-03-310.150209Freq:M,dtype:float64

11.4 Time Zone Handling

Working with time zones is generally considered one of the most unpleasant parts of time series manipulation. As a result, many time series users choose to work with time series in coordinated universal time or UTC, which is the successor to Greenwich Mean Time and is the current international standard. Time zones are expressed as offsets from UTC; for example, New York is four hours behind UTC during daylight saving time and five hours behind the rest of the year.

In Python, time zone information comes from the third-party pytz library (installable with pip or conda), which exposes the Olson database, a compilation of

world time zone information. This is especially important for historical

data because the daylight saving time (DST) transition dates (and even UTC offsets) have been changed

numerous times depending on the whims of local governments. In the United

States, the DST transition times have been changed many times since

1900!

For detailed information about the pytz library, you’ll need to look at that

library’s documentation. As far as this book is concerned, pandas wraps

pytz’s functionality so you can ignore

its API outside of the time zone names. Time zone names can be found

interactively and in the docs:

In[110]:importpytzIn[111]:pytz.common_timezones[-5:]Out[111]:['US/Eastern','US/Hawaii','US/Mountain','US/Pacific','UTC']

To get a time zone object from pytz, use pytz.timezone:

In[112]:tz=pytz.timezone('America/New_York')In[113]:tzOut[113]:<DstTzInfo'America/New_York'LMT-1day,19:04:00STD>

Methods in pandas will accept either time zone names or these objects.

Time Zone Localization and Conversion

By default, time series in pandas are time zone naive. For example, consider the following time series:

In[114]:rng=pd.date_range('3/9/2012 9:30',periods=6,freq='D')In[115]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(len(rng)),index=rng)In[116]:tsOut[116]:2012-03-0909:30:00-0.2024692012-03-1009:30:000.0507182012-03-1109:30:000.6398692012-03-1209:30:000.5975942012-03-1309:30:00-0.7972462012-03-1409:30:000.472879Freq:D,dtype:float64

The index’s tz field is

None:

In[117]:(ts.index.tz)None

Date ranges can be generated with a time zone set:

In[118]:pd.date_range('3/9/2012 9:30',periods=10,freq='D',tz='UTC')Out[118]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-03-09 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-10 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-11 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-12 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-13 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-14 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-15 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-16 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-17 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-18 09:30:00+00:00'],dtype='datetime64[ns, UTC]',freq='D')

Conversion from naive to localized is handled by

the tz_localize method:

In[119]:tsOut[119]:2012-03-0909:30:00-0.2024692012-03-1009:30:000.0507182012-03-1109:30:000.6398692012-03-1209:30:000.5975942012-03-1309:30:00-0.7972462012-03-1409:30:000.472879Freq:D,dtype:float64In[120]:ts_utc=ts.tz_localize('UTC')In[121]:ts_utcOut[121]:2012-03-0909:30:00+00:00-0.2024692012-03-1009:30:00+00:000.0507182012-03-1109:30:00+00:000.6398692012-03-1209:30:00+00:000.5975942012-03-1309:30:00+00:00-0.7972462012-03-1409:30:00+00:000.472879Freq:D,dtype:float64In[122]:ts_utc.indexOut[122]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-03-09 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-10 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-11 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-12 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-13 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-14 09:30:00+00:00'],dtype='datetime64[ns, UTC]',freq='D')

Once a time series has been localized to a particular time zone,

it can be converted to another time zone with tz_convert:

In[123]:ts_utc.tz_convert('America/New_York')Out[123]:2012-03-0904:30:00-05:00-0.2024692012-03-1004:30:00-05:000.0507182012-03-1105:30:00-04:000.6398692012-03-1205:30:00-04:000.5975942012-03-1305:30:00-04:00-0.7972462012-03-1405:30:00-04:000.472879Freq:D,dtype:float64

In the case of the preceding time series, which straddles a DST

transition in the America/New_York time zone, we could localize to EST

and convert to, say, UTC or Berlin time:

In[124]:ts_eastern=ts.tz_localize('America/New_York')In[125]:ts_eastern.tz_convert('UTC')Out[125]:2012-03-0914:30:00+00:00-0.2024692012-03-1014:30:00+00:000.0507182012-03-1113:30:00+00:000.6398692012-03-1213:30:00+00:000.5975942012-03-1313:30:00+00:00-0.7972462012-03-1413:30:00+00:000.472879Freq:D,dtype:float64In[126]:ts_eastern.tz_convert('Europe/Berlin')Out[126]:2012-03-0915:30:00+01:00-0.2024692012-03-1015:30:00+01:000.0507182012-03-1114:30:00+01:000.6398692012-03-1214:30:00+01:000.5975942012-03-1314:30:00+01:00-0.7972462012-03-1414:30:00+01:000.472879Freq:D,dtype:float64

tz_localize and tz_convert are also instance methods

on DatetimeIndex:

In[127]:ts.index.tz_localize('Asia/Shanghai')Out[127]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-03-09 09:30:00+08:00','2012-03-10 09:30:00+08:00','2012-03-11 09:30:00+08:00','2012-03-12 09:30:00+08:00','2012-03-13 09:30:00+08:00','2012-03-14 09:30:00+08:00'],dtype='datetime64[ns, Asia/Shanghai]',freq='D')

Caution

Localizing naive timestamps also checks for ambiguous or non-existent times around daylight saving time transitions.

Operations with Time Zone−Aware Timestamp Objects

Similar to time series and date ranges, individual Timestamp

objects similarly can be localized from naive to time zone–aware and

converted from one time zone to another:

In[128]:stamp=pd.Timestamp('2011-03-12 04:00')In[129]:stamp_utc=stamp.tz_localize('utc')In[130]:stamp_utc.tz_convert('America/New_York')Out[130]:Timestamp('2011-03-11 23:00:00-0500',tz='America/New_York')

You can also pass a time zone when creating the

Timestamp:

In[131]:stamp_moscow=pd.Timestamp('2011-03-12 04:00',tz='Europe/Moscow')In[132]:stamp_moscowOut[132]:Timestamp('2011-03-12 04:00:00+0300',tz='Europe/Moscow')

Time zone–aware Timestamp objects internally

store a UTC timestamp value as nanoseconds since the Unix epoch (January

1, 1970); this UTC value is invariant between time zone

conversions:

In[133]:stamp_utc.valueOut[133]:1299902400000000000In[134]:stamp_utc.tz_convert('America/New_York').valueOut[134]:1299902400000000000

When performing time arithmetic using pandas’s DateOffset objects, pandas respects daylight saving time transitions where

possible. Here we construct timestamps that occur right before DST

transitions (forward and backward). First, 30 minutes before

transitioning to DST:

In[135]:frompandas.tseries.offsetsimportHourIn[136]:stamp=pd.Timestamp('2012-03-12 01:30',tz='US/Eastern')In[137]:stampOut[137]:Timestamp('2012-03-12 01:30:00-0400',tz='US/Eastern')In[138]:stamp+Hour()Out[138]:Timestamp('2012-03-12 02:30:00-0400',tz='US/Eastern')

Then, 90 minutes before transitioning out of DST:

In[139]:stamp=pd.Timestamp('2012-11-04 00:30',tz='US/Eastern')In[140]:stampOut[140]:Timestamp('2012-11-04 00:30:00-0400',tz='US/Eastern')In[141]:stamp+2*Hour()Out[141]:Timestamp('2012-11-04 01:30:00-0500',tz='US/Eastern')

Operations Between Different Time Zones

If two time series with different time zones are combined, the result will be UTC. Since the timestamps are stored under the hood in UTC, this is a straightforward operation and requires no conversion to happen:

In[142]:rng=pd.date_range('3/7/2012 9:30',periods=10,freq='B')In[143]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(len(rng)),index=rng)In[144]:tsOut[144]:2012-03-0709:30:000.5223562012-03-0809:30:00-0.5463482012-03-0909:30:00-0.7335372012-03-1209:30:001.3027362012-03-1309:30:000.0221992012-03-1409:30:000.3642872012-03-1509:30:00-0.9228392012-03-1609:30:000.3126562012-03-1909:30:00-1.1284972012-03-2009:30:00-0.333488Freq:B,dtype:float64In[145]:ts1=ts[:7].tz_localize('Europe/London')In[146]:ts2=ts1[2:].tz_convert('Europe/Moscow')In[147]:result=ts1+ts2In[148]:result.indexOut[148]:DatetimeIndex(['2012-03-07 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-08 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-09 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-12 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-13 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-14 09:30:00+00:00','2012-03-15 09:30:00+00:00'],dtype='datetime64[ns, UTC]',freq='B')

11.5 Periods and Period Arithmetic

Periods represent timespans, like days, months, quarters, or years. The

Period class represents this data type, requiring a string or integer and

a frequency from Table 11-4:

In[149]:p=pd.Period(2007,freq='A-DEC')In[150]:pOut[150]:Period('2007','A-DEC')

In this case, the Period object

represents the full timespan from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2007,

inclusive. Conveniently, adding and subtracting integers from periods has

the effect of shifting by their frequency:

In[151]:p+5Out[151]:Period('2012','A-DEC')In[152]:p-2Out[152]:Period('2005','A-DEC')

If two periods have the same frequency, their difference is the number of units between them:

In[153]:pd.Period('2014',freq='A-DEC')-pOut[153]:7

Regular ranges of periods can be constructed with the period_range

function:

In[154]:rng=pd.period_range('2000-01-01','2000-06-30',freq='M')In[155]:rngOut[155]:PeriodIndex(['2000-01','2000-02','2000-03','2000-04','2000-05','2000-06'], dtype='period[M]', freq='M')

The PeriodIndex class stores a

sequence of periods and can serve as an axis index in any pandas data

structure:

In[156]:pd.Series(np.random.randn(6),index=rng)Out[156]:2000-01-0.5145512000-02-0.5597822000-03-0.7834082000-04-1.7976852000-05-0.1726702000-060.680215Freq:M,dtype:float64

If you have an array of strings, you can also use the PeriodIndex

class:

In[157]:values=['2001Q3','2002Q2','2003Q1']In[158]:index=pd.PeriodIndex(values,freq='Q-DEC')In[159]:indexOut[159]:PeriodIndex(['2001Q3','2002Q2','2003Q1'],dtype='period[Q-DEC]',freq='Q-DEC')

Period Frequency Conversion

Periods and PeriodIndex objects

can be converted to another frequency with their asfreq method. As an example, suppose we had an annual period and wanted

to convert it into a monthly period either at the start or end of the

year. This is fairly straightforward:

In[160]:p=pd.Period('2007',freq='A-DEC')In[161]:pOut[161]:Period('2007','A-DEC')In[162]:p.asfreq('M',how='start')Out[162]:Period('2007-01','M')In[163]:p.asfreq('M',how='end')Out[163]:Period('2007-12','M')

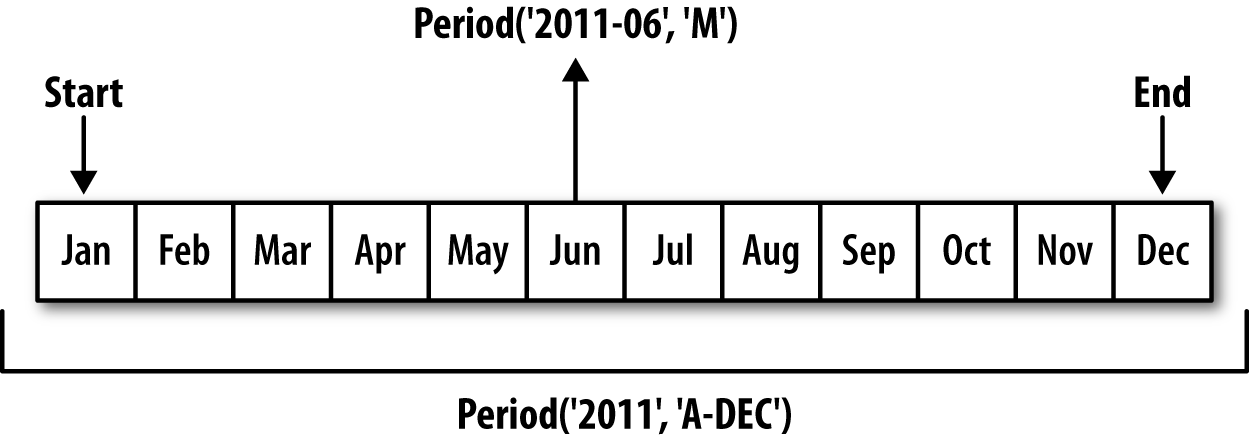

You can think of Period('2007',

'A-DEC') as being a sort of cursor pointing to a span of time,

subdivided by monthly periods. See Figure 11-1 for an illustration of this. For a

fiscal year ending on a month other than December,

the corresponding monthly subperiods are different:

In[164]:p=pd.Period('2007',freq='A-JUN')In[165]:pOut[165]:Period('2007','A-JUN')In[166]:p.asfreq('M','start')Out[166]:Period('2006-07','M')In[167]:p.asfreq('M','end')Out[167]:Period('2007-06','M')

Figure 11-1. Period frequency conversion illustration

When you are converting from high to low frequency, pandas determines the superperiod depending on where the subperiod “belongs.” For example,

in A-JUN frequency, the month

Aug-2007 is actually part of the

2008 period:

In[168]:p=pd.Period('Aug-2007','M')In[169]:p.asfreq('A-JUN')Out[169]:Period('2008','A-JUN')

Whole PeriodIndex objects or

time series can be similarly converted with the same semantics:

In[170]:rng=pd.period_range('2006','2009',freq='A-DEC')In[171]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(len(rng)),index=rng)In[172]:tsOut[172]:20061.60757820070.2003812008-0.8340682009-0.302988Freq:A-DEC,dtype:float64In[173]:ts.asfreq('M',how='start')Out[173]:2006-011.6075782007-010.2003812008-01-0.8340682009-01-0.302988Freq:M,dtype:float64

Here, the annual periods are replaced with monthly periods

corresponding to the first month falling within each annual period. If

we instead wanted the last business day of each year, we can use the

'B' frequency and indicate that we want the end of

the period:

In[174]:ts.asfreq('B',how='end')Out[174]:2006-12-291.6075782007-12-310.2003812008-12-31-0.8340682009-12-31-0.302988Freq:B,dtype:float64

Quarterly Period Frequencies

Quarterly data is standard in accounting, finance, and other fields. Much

quarterly data is reported relative to a fiscal year

end, typically the last calendar or business day of one of

the 12 months of the year. Thus, the period 2012Q4 has a different meaning depending on

fiscal year end. pandas supports all 12 possible quarterly frequencies

as Q-JAN through Q-DEC:

In[175]:p=pd.Period('2012Q4',freq='Q-JAN')In[176]:pOut[176]:Period('2012Q4','Q-JAN')

In the case of fiscal year ending in January, 2012Q4 runs from November through January,

which you can check by converting to daily frequency. See Figure 11-2 for an illustration.

Figure 11-2. Different quarterly frequency conventions

In[177]:p.asfreq('D','start')Out[177]:Period('2011-11-01','D')In[178]:p.asfreq('D','end')Out[178]:Period('2012-01-31','D')

Thus, it’s possible to do easy period arithmetic; for example, to get the timestamp at 4 PM on the second-to-last business day of the quarter, you could do:

In[179]:p4pm=(p.asfreq('B','e')-1).asfreq('T','s')+16*60In[180]:p4pmOut[180]:Period('2012-01-30 16:00','T')In[181]:p4pm.to_timestamp()Out[181]:Timestamp('2012-01-30 16:00:00')

You can generate quarterly ranges using period_range.

Arithmetic is identical, too:

In[182]:rng=pd.period_range('2011Q3','2012Q4',freq='Q-JAN')In[183]:ts=pd.Series(np.arange(len(rng)),index=rng)In[184]:tsOut[184]:2011Q302011Q412012Q122012Q232012Q342012Q45Freq:Q-JAN,dtype:int64In[185]:new_rng=(rng.asfreq('B','e')-1).asfreq('T','s')+16*60In[186]:ts.index=new_rng.to_timestamp()In[187]:tsOut[187]:2010-10-2816:00:0002011-01-2816:00:0012011-04-2816:00:0022011-07-2816:00:0032011-10-2816:00:0042012-01-3016:00:005dtype:int64

Converting Timestamps to Periods (and Back)

Series and DataFrame objects indexed by timestamps can be converted to periods with

the to_period

method:

In[188]:rng=pd.date_range('2000-01-01',periods=3,freq='M')In[189]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(3),index=rng)In[190]:tsOut[190]:2000-01-311.6632612000-02-29-0.9962062000-03-311.521760Freq:M,dtype:float64In[191]:pts=ts.to_period()In[192]:ptsOut[192]:2000-011.6632612000-02-0.9962062000-031.521760Freq:M,dtype:float64

Since periods refer to non-overlapping timespans, a timestamp can

only belong to a single period for a given frequency. While the

frequency of the new PeriodIndex is

inferred from the timestamps by default, you can specify any frequency

you want. There is also no problem with having duplicate periods in the

result:

In[193]:rng=pd.date_range('1/29/2000',periods=6,freq='D')In[194]:ts2=pd.Series(np.random.randn(6),index=rng)In[195]:ts2Out[195]:2000-01-290.2441752000-01-300.4233312000-01-31-0.6540402000-02-012.0891542000-02-02-0.0602202000-02-03-0.167933Freq:D,dtype:float64In[196]:ts2.to_period('M')Out[196]:2000-010.2441752000-010.4233312000-01-0.6540402000-022.0891542000-02-0.0602202000-02-0.167933Freq:M,dtype:float64

To convert back to timestamps, use to_timestamp:

In[197]:pts=ts2.to_period()In[198]:ptsOut[198]:2000-01-290.2441752000-01-300.4233312000-01-31-0.6540402000-02-012.0891542000-02-02-0.0602202000-02-03-0.167933Freq:D,dtype:float64In[199]:pts.to_timestamp(how='end')Out[199]:2000-01-290.2441752000-01-300.4233312000-01-31-0.6540402000-02-012.0891542000-02-02-0.0602202000-02-03-0.167933Freq:D,dtype:float64

Creating a PeriodIndex from Arrays

Fixed frequency datasets are sometimes stored with timespan information spread across multiple columns. For example, in this macroeconomic dataset, the year and quarter are in different columns:

In[200]:data=pd.read_csv('examples/macrodata.csv')In[201]:data.head(5)Out[201]:yearquarterrealgdprealconsrealinvrealgovtrealdpicpi\01959.01.02710.3491707.4286.898470.0451886.928.9811959.02.02778.8011733.7310.859481.3011919.729.1521959.03.02775.4881751.8289.226491.2601916.429.3531959.04.02785.2041753.7299.356484.0521931.329.3741960.01.02847.6991770.5331.722462.1991955.529.54m1tbilrateunemppopinflrealint0139.72.825.8177.1460.000.001141.73.085.1177.8302.340.742140.53.825.3178.6572.741.093140.04.335.6179.3860.274.064139.63.505.2180.0072.311.19In[202]:data.yearOut[202]:01959.011959.021959.031959.041960.051960.061960.071960.081961.091961.0...1932007.01942007.01952007.01962008.01972008.01982008.01992008.02002009.02012009.02022009.0Name:year,Length:203,dtype:float64In[203]:data.quarterOut[203]:01.012.023.034.041.052.063.074.081.092.0...1932.01943.01954.01961.01972.01983.01994.02001.02012.02023.0Name:quarter,Length:203,dtype:float64

By passing these arrays to PeriodIndex with a frequency, you can combine them to form an index for the DataFrame:

In[204]:index=pd.PeriodIndex(year=data.year,quarter=data.quarter,.....:freq='Q-DEC')In[205]:indexOut[205]:PeriodIndex(['1959Q1','1959Q2','1959Q3','1959Q4','1960Q1','1960Q2','1960Q3','1960Q4','1961Q1','1961Q2',...'2007Q2','2007Q3','2007Q4','2008Q1','2008Q2','2008Q3','2008Q4','2009Q1','2009Q2','2009Q3'],dtype='period[Q-DEC]',length=203,freq='Q-DEC')In[206]:data.index=indexIn[207]:data.inflOut[207]:1959Q10.001959Q22.341959Q32.741959Q40.271960Q12.311960Q20.141960Q32.701960Q41.211961Q1-0.401961Q21.47...2007Q22.752007Q33.452007Q46.382008Q12.822008Q28.532008Q3-3.162008Q4-8.792009Q10.942009Q23.372009Q33.56Freq:Q-DEC,Name:infl,Length:203,dtype:float64

11.6 Resampling and Frequency Conversion

Resampling refers to the process of converting a time series from one frequency to

another. Aggregating higher frequency data to lower frequency is

called downsampling, while converting

lower frequency to higher frequency is called upsampling. Not all resampling

falls into either of these categories; for example, converting W-WED (weekly on Wednesday) to W-FRI is neither upsampling nor

downsampling.

pandas objects are equipped with a resample method, which

is the workhorse function for all frequency conversion.

resample has a similar API to

groupby; you call resample to group

the data, then call an aggregation function:

In[208]:rng=pd.date_range('2000-01-01',periods=100,freq='D')In[209]:ts=pd.Series(np.random.randn(len(rng)),index=rng)In[210]:tsOut[210]:2000-01-010.6316342000-01-02-1.5943132000-01-03-1.5199372000-01-041.1087522000-01-051.2558532000-01-06-0.0243302000-01-07-2.0479392000-01-08-0.2726572000-01-09-1.6926152000-01-101.423830...2000-03-31-0.0078522000-04-01-1.6388062000-04-021.4012272000-04-031.7585392000-04-040.6289322000-04-05-0.4237762000-04-060.7897402000-04-070.9375682000-04-08-2.2532942000-04-09-1.772919Freq:D,Length:100,dtype:float64In[211]:ts.resample('M').mean()Out[211]:2000-01-31-0.1658932000-02-290.0786062000-03-310.2238112000-04-30-0.063643Freq:M,dtype:float64In[212]:ts.resample('M',kind='period').mean()Out[212]:2000-01-0.1658932000-020.0786062000-030.2238112000-04-0.063643Freq:M,dtype:float64

resample is a flexible and

high-performance method that can be used to process very large time

series. The examples in the following sections illustrate its semantics

and use. Table 11-5 summarizes some of its

options.

| Argument | Description |

|---|---|

freq | String or DateOffset indicating desired resampled frequency

(e.g., ‘M', ’5min', or Second(15)) |

axis | Axis to resample on; default axis=0 |

fill_method | How to interpolate when upsampling, as in 'ffill' or 'bfill'; by default does no

interpolation |

closed | In downsampling, which end of each interval is closed

(inclusive), 'right' or

'left' |

label | In downsampling, how to label the aggregated result, with

the 'right' or 'left' bin edge (e.g., the 9:30 to 9:35

five-minute interval could be labeled 9:30 or 9:35) |

loffset | Time adjustment to the bin labels, such as '-1s' / Second(-1) to shift the aggregate labels

one second earlier |

limit | When forward or backward filling, the maximum number of periods to fill |

kind | Aggregate to periods ('period') or timestamps ('timestamp'); defaults to the type of

index the time series has |

convention | When resampling periods, the convention ('start' or 'end') for converting the low-frequency

period to high frequency; defaults to 'end' |

Downsampling

Aggregating data to a regular, lower frequency is a pretty normal time series task. The

data you’re aggregating doesn’t need to be fixed frequently; the desired

frequency defines bin edges that are used to slice

the time series into pieces to aggregate. For example, to convert to

monthly, 'M' or 'BM', you need to chop up the data into one-month intervals. Each interval is said to be

half-open; a data point can only belong to one

interval, and the union of the intervals must make up the whole time

frame. There are a couple things to think about when using resample to downsample data:

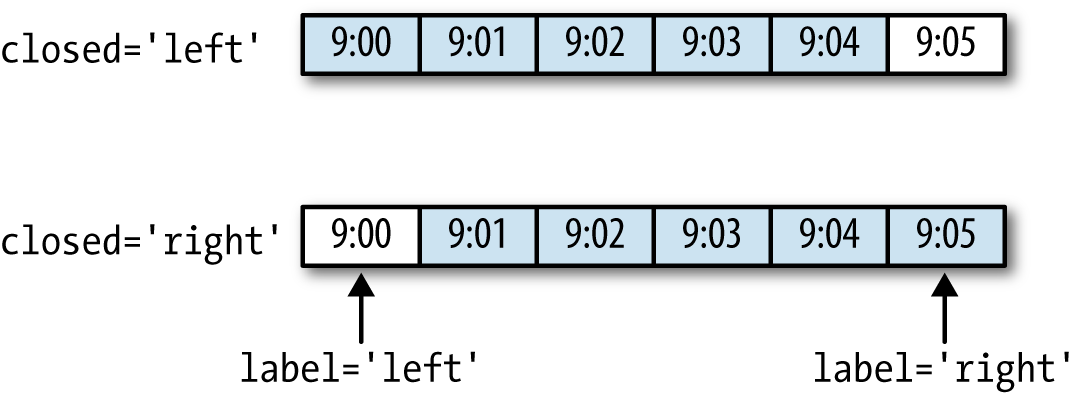

Which side of each interval is closed

How to label each aggregated bin, either with the start of the interval or the end

To illustrate, let’s look at some one-minute data:

In[213]:rng=pd.date_range('2000-01-01',periods=12,freq='T')In[214]:ts=pd.Series(np.arange(12),index=rng)In[215]:tsOut[215]:2000-01-0100:00:0002000-01-0100:01:0012000-01-0100:02:0022000-01-0100:03:0032000-01-0100:04:0042000-01-0100:05:0052000-01-0100:06:0062000-01-0100:07:0072000-01-0100:08:0082000-01-0100:09:0092000-01-0100:10:00102000-01-0100:11:0011Freq:T,dtype:int64

Suppose you wanted to aggregate this data into five-minute chunks or bars by taking the sum of each group:

In[216]:ts.resample('5min',closed='right').sum()Out[216]:1999-12-3123:55:0002000-01-0100:00:00152000-01-0100:05:00402000-01-0100:10:0011Freq:5T,dtype:int64

The frequency you pass defines bin edges in five-minute

increments. By default, the

left bin edge is inclusive, so the

00:00 value is included in the

00:00 to 00:05 interval.1 Passing closed='right'

changes the interval to be closed on the right:

In[217]:ts.resample('5min',closed='right').sum()Out[217]:1999-12-3123:55:0002000-01-0100:00:00152000-01-0100:05:00402000-01-0100:10:0011Freq:5T,dtype:int64

The resulting time series is labeled by the timestamps from the

left side of each bin. By passing label='right' you can label them with the

right bin edge:

In[218]:ts.resample('5min',closed='right',label='right').sum()Out[218]:2000-01-0100:00:0002000-01-0100:05:00152000-01-0100:10:00402000-01-0100:15:0011Freq:5T,dtype:int64

See Figure 11-3 for an illustration of minute frequency data being resampled to five-minute frequency.

Figure 11-3. Five-minute resampling illustration of closed, label conventions

Lastly, you might want to shift the result index by some amount,

say subtracting one second from the right edge to make it more clear

which interval the timestamp refers to. To do this, pass a string or

date offset to loffset:

In[219]:ts.resample('5min',closed='right',.....:label='right',loffset='-1s').sum()Out[219]:1999-12-3123:59:5902000-01-0100:04:59152000-01-0100:09:59402000-01-0100:14:5911Freq:5T,dtype:int64

You also could have accomplished the effect of loffset by calling the shift method on the

result without the loffset.

Open-High-Low-Close (OHLC) resampling

In finance, a popular way to aggregate a time series is to compute

four values for each bucket: the first (open), last (close), maximum

(high), and minimal (low) values. By using the ohlc

aggregate function you will obtain a DataFrame having columns

containing these four aggregates, which are efficiently computed in a

single sweep of the data:

In[220]:ts.resample('5min').ohlc()Out[220]:openhighlowclose2000-01-0100:00:0004042000-01-0100:05:0059592000-01-0100:10:0010111011

Upsampling and Interpolation

When converting from a low frequency to a higher frequency, no aggregation is needed. Let’s consider a DataFrame with some weekly data:

In[221]:frame=pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(2,4),.....:index=pd.date_range('1/1/2000',periods=2,.....:freq='W-WED'),.....:columns=['Colorado','Texas','New York','Ohio'])In[222]:frameOut[222]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000-01-05-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-12-0.0466620.9272380.482284-0.867130

When you are using an aggregation function with this data, there is only

one value per group, and missing values result in the gaps. We use the

asfreq method to convert to the higher frequency without any

aggregation:

In[223]:df_daily=frame.resample('D').asfreq()In[224]:df_dailyOut[224]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000-01-05-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-06NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-07NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-08NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-09NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-10NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-11NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-12-0.0466620.9272380.482284-0.867130

Suppose you wanted to fill forward each weekly value on the

non-Wednesdays. The same filling or interpolation methods available in the fillna

and reindex methods are available for

resampling:

In[225]:frame.resample('D').ffill()Out[225]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000-01-05-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-06-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-07-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-08-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-09-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-10-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-11-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-12-0.0466620.9272380.482284-0.867130

You can similarly choose to only fill a certain number of periods forward to limit how far to continue using an observed value:

In[226]:frame.resample('D').ffill(limit=2)Out[226]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000-01-05-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-06-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-07-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-08NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-09NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-10NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-11NaNNaNNaNNaN2000-01-12-0.0466620.9272380.482284-0.867130

Notably, the new date index need not overlap with the old one at all:

In[227]:frame.resample('W-THU').ffill()Out[227]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000-01-06-0.8964310.6772630.0365030.0871022000-01-13-0.0466620.9272380.482284-0.867130

Resampling with Periods

Resampling data indexed by periods is similar to timestamps:

In[228]:frame=pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(24,4),.....:index=pd.period_range('1-2000','12-2001',.....:freq='M'),.....:columns=['Colorado','Texas','New York','Ohio'])In[229]:frame[:5]Out[229]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000-010.493841-0.1554341.3972861.5070552000-02-1.1794420.4431711.395676-0.5296582000-030.7873580.2488450.7432391.2677462000-041.302395-0.272154-0.051532-0.4677402000-05-1.0408160.4264190.312945-1.115689In[230]:annual_frame=frame.resample('A-DEC').mean()In[231]:annual_frameOut[231]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio20000.5567030.0166310.111873-0.02744520010.0463030.1633440.251503-0.157276

Upsampling is more nuanced, as you must make a decision about which

end of the timespan in the new frequency to place the values before

resampling, just like the asfreq

method. The convention argument

defaults to 'start' but can also be

'end':

# Q-DEC: Quarterly, year ending in DecemberIn[232]:annual_frame.resample('Q-DEC').ffill()Out[232]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000Q10.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452000Q20.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452000Q30.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452000Q40.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q10.0463030.1633440.251503-0.1572762001Q20.0463030.1633440.251503-0.1572762001Q30.0463030.1633440.251503-0.1572762001Q40.0463030.1633440.251503-0.157276In[233]:annual_frame.resample('Q-DEC',convention='end').ffill()Out[233]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000Q40.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q10.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q20.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q30.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q40.0463030.1633440.251503-0.157276

Since periods refer to timespans, the rules about upsampling and downsampling are more rigid:

In downsampling, the target frequency must be a subperiod of the source frequency.

In upsampling, the target frequency must be a superperiod of the source frequency.

If these rules are not satisfied, an exception will be raised.

This mainly affects the quarterly, annual, and weekly frequencies; for

example, the timespans defined by Q-MAR only line up with A-MAR, A-JUN, A-SEP, and A-DEC:

In[234]:annual_frame.resample('Q-MAR').ffill()Out[234]:ColoradoTexasNewYorkOhio2000Q40.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q10.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q20.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q30.5567030.0166310.111873-0.0274452001Q40.0463030.1633440.251503-0.1572762002Q10.0463030.1633440.251503-0.1572762002Q20.0463030.1633440.251503-0.1572762002Q30.0463030.1633440.251503-0.157276

11.7 Moving Window Functions

An important class of array transformations used for time series operations are statistics and other functions evaluated over a sliding window or with exponentially decaying weights. This can be useful for smoothing noisy or gappy data. I call these moving window functions, even though it includes functions without a fixed-length window like exponentially weighted moving average. Like other statistical functions, these also automatically exclude missing data.

Before digging in, we can load up some time series data and resample it to business day frequency:

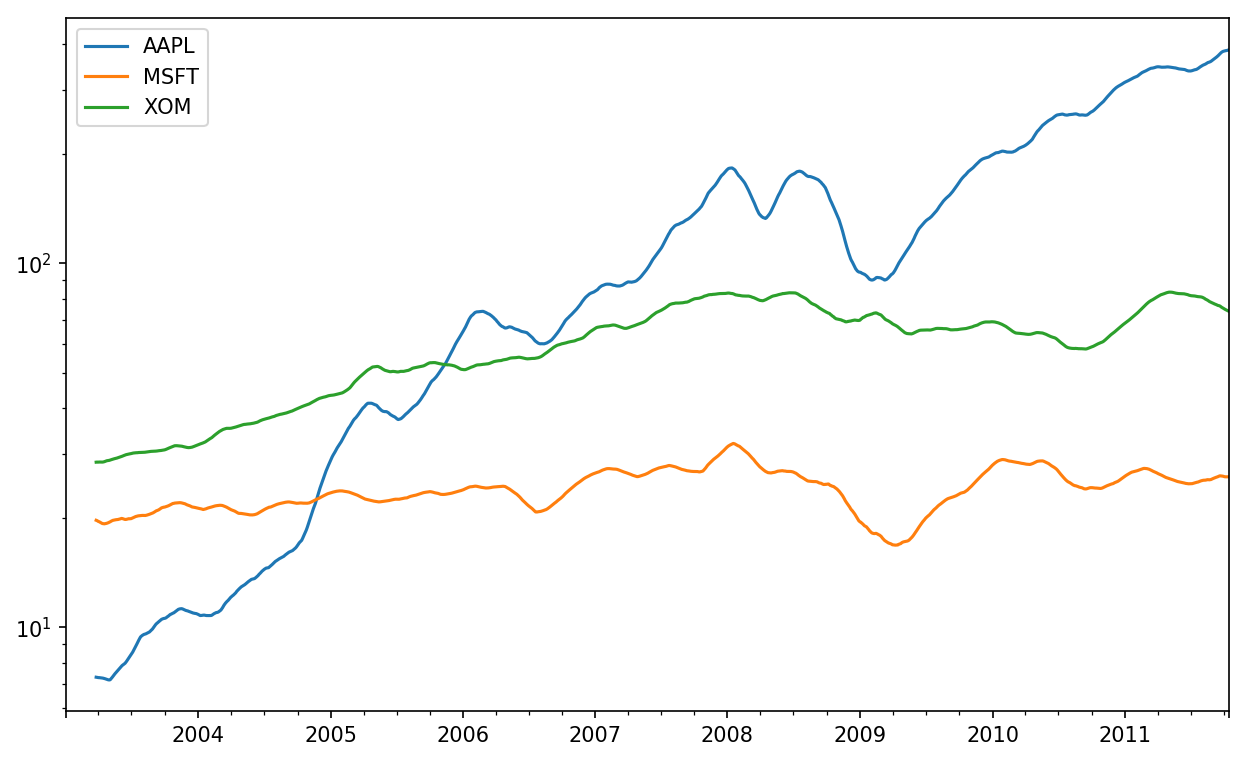

In[235]:close_px_all=pd.read_csv('examples/stock_px_2.csv',.....:parse_dates=True,index_col=0)In[236]:close_px=close_px_all[['AAPL','MSFT','XOM']]In[237]:close_px=close_px.resample('B').ffill()

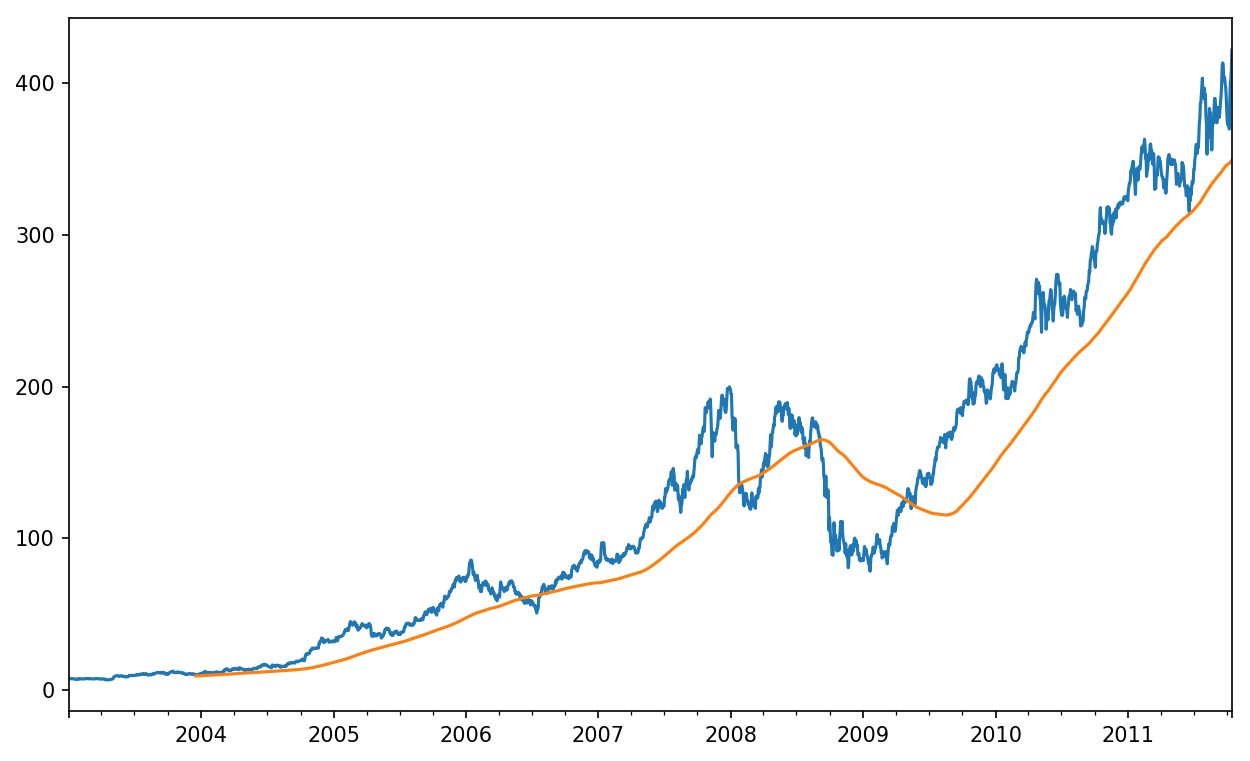

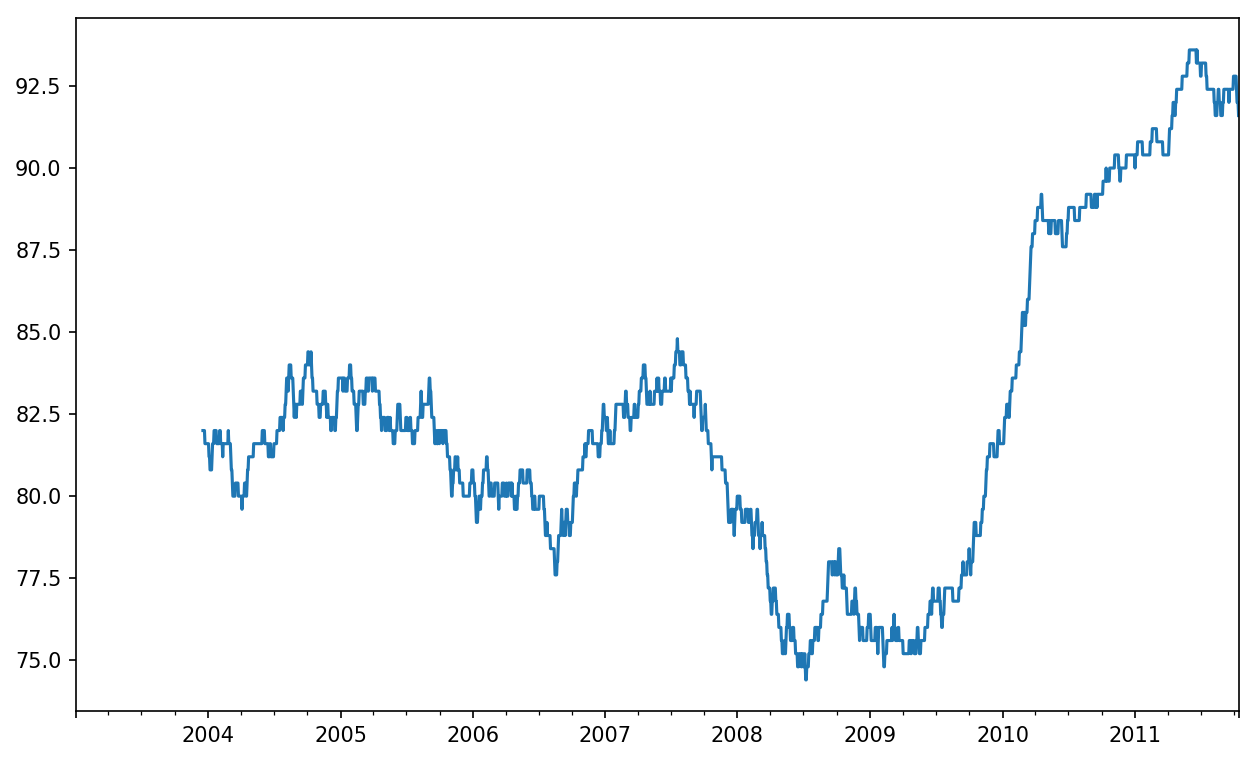

I now introduce the rolling operator, which behaves similarly to resample and

groupby. It can be called on a Series or DataFrame

along with a window (expressed as a

number of periods; see Figure 11-4 for the plot

created):

In[238]:close_px.AAPL.plot()Out[238]:<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplotat0x7fa59eaf0b00>In[239]:close_px.AAPL.rolling(250).mean().plot()

Figure 11-4. Apple Price with 250-day MA

The expression rolling(250) is similar in

behavior to groupby, but instead of grouping it creates

an object that enables grouping over a 250-day sliding window. So here we

have the 250-day moving window average of Apple’s stock price.

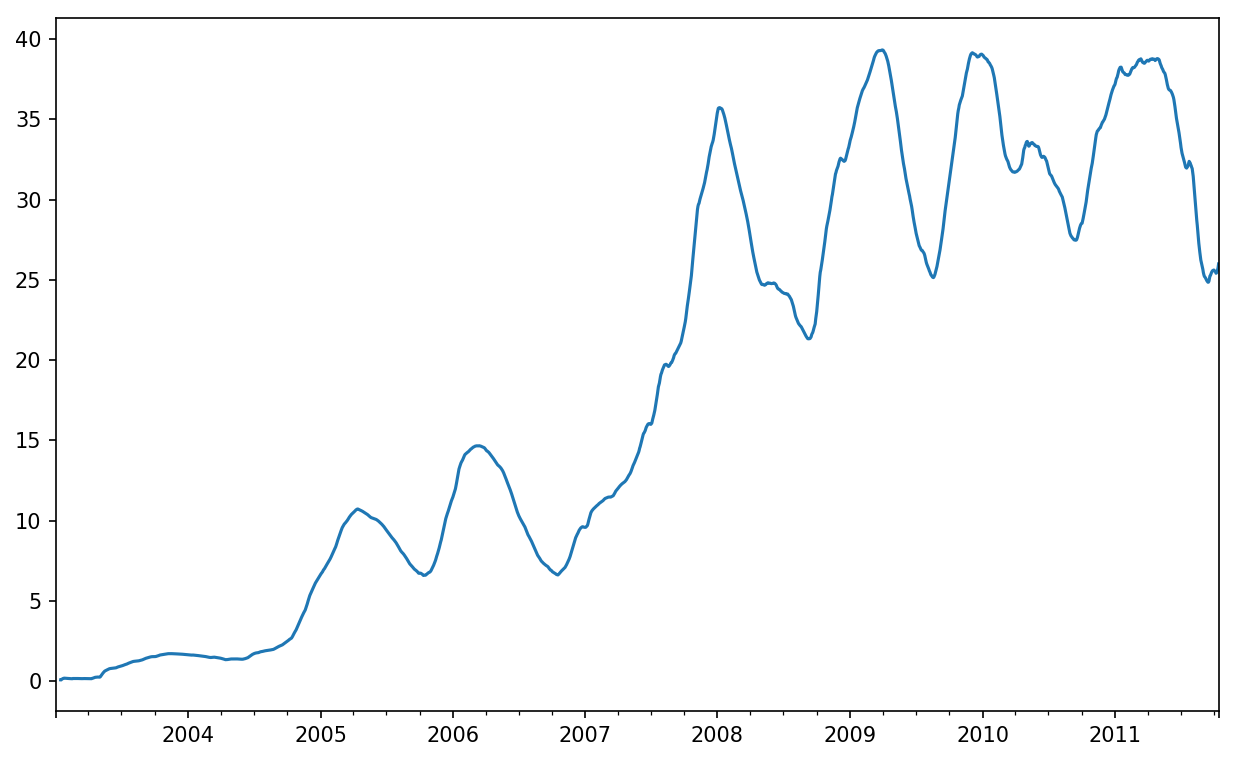

By default rolling functions require all of the values in the window

to be non-NA. This behavior can be changed to account for missing data

and, in particular, the fact that you will have fewer than window periods of data at the beginning of the

time series (see Figure 11-5):

In[241]:appl_std250=close_px.AAPL.rolling(250,min_periods=10).std()In[242]:appl_std250[5:12]Out[242]:2003-01-09NaN2003-01-10NaN2003-01-13NaN2003-01-14NaN2003-01-150.0774962003-01-160.0747602003-01-170.112368Freq:B,Name:AAPL,dtype:float64In[243]:appl_std250.plot()

Figure 11-5. Apple 250-day daily return standard deviation

In order to compute an expanding window mean,

use the expanding operator instead of

rolling. The expanding mean starts the time window from

the beginning of the time series and increases the size of the window

until it encompasses the whole series. An expanding window mean on the

apple_std250 time series looks like this:

In[244]:expanding_mean=appl_std250.expanding().mean()

Calling a moving window function on a DataFrame applies the transformation to each column (see Figure 11-6):

In[246]:close_px.rolling(60).mean().plot(logy=True)

Figure 11-6. Stocks prices 60-day MA (log Y-axis)

The rolling function also accepts a string indicating a fixed-size time offset

rather than a set number of periods. Using this notation can be useful for

irregular time series. These are the same strings that you can pass to

resample. For example, we could compute a 20-day

rolling mean like so:

In[247]:close_px.rolling('20D').mean()Out[247]:AAPLMSFTXOM2003-01-027.40000021.11000029.2200002003-01-037.42500021.12500029.2300002003-01-067.43333321.25666729.4733332003-01-077.43250021.42500029.3425002003-01-087.40200021.40200029.2400002003-01-097.39166721.49000029.2733332003-01-107.38714321.55857129.2385712003-01-137.37875021.63375029.1975002003-01-147.37000021.71777829.1944442003-01-157.35500021.75700029.152000............2011-10-03398.00214325.89071472.4135712011-10-04396.80214325.80785772.4271432011-10-05395.75142925.72928672.4228572011-10-06394.09928625.67357172.3757142011-10-07392.47933325.71200072.4546672011-10-10389.35142925.60214372.5278572011-10-11388.50500025.67428672.8350002011-10-12388.53142925.81000073.4007142011-10-13388.82642925.96142973.9050002011-10-14391.03800026.04866774.185333[2292rowsx3columns]

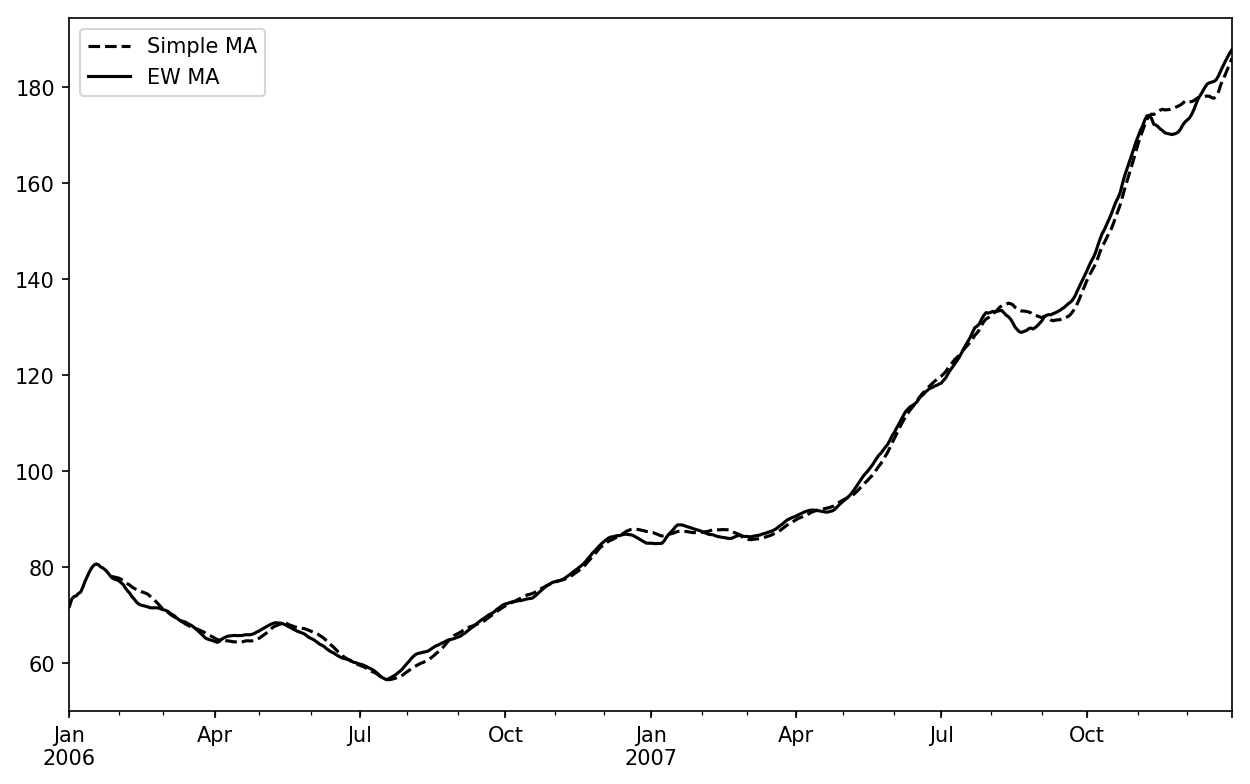

Exponentially Weighted Functions

An alternative to using a static window size with equally weighted observations is to specify a constant decay factor to give more weight to more recent observations. There are a couple of ways to specify the decay factor. A popular one is using a span, which makes the result comparable to a simple moving window function with window size equal to the span.

Since an exponentially weighted statistic places more weight on more recent observations, it “adapts” faster to changes compared with the equal-weighted version.

pandas has the ewm operator to go along with rolling and

expanding. Here’s an example comparing a 60-day

moving average of Apple’s stock price with an EW moving average with

span=60 (see Figure 11-7):

In[249]:aapl_px=close_px.AAPL['2006':'2007']In[250]:ma60=aapl_px.rolling(30,min_periods=20).mean()In[251]:ewma60=aapl_px.ewm(span=30).mean()In[252]:ma60.plot(style='k--',label='Simple MA')Out[252]:<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplotat0x7fa59e5df908>In[253]:ewma60.plot(style='k-',label='EW MA')Out[253]:<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplotat0x7fa59e5df908>In[254]:plt.legend()

Figure 11-7. Simple moving average versus exponentially weighted

Binary Moving Window Functions

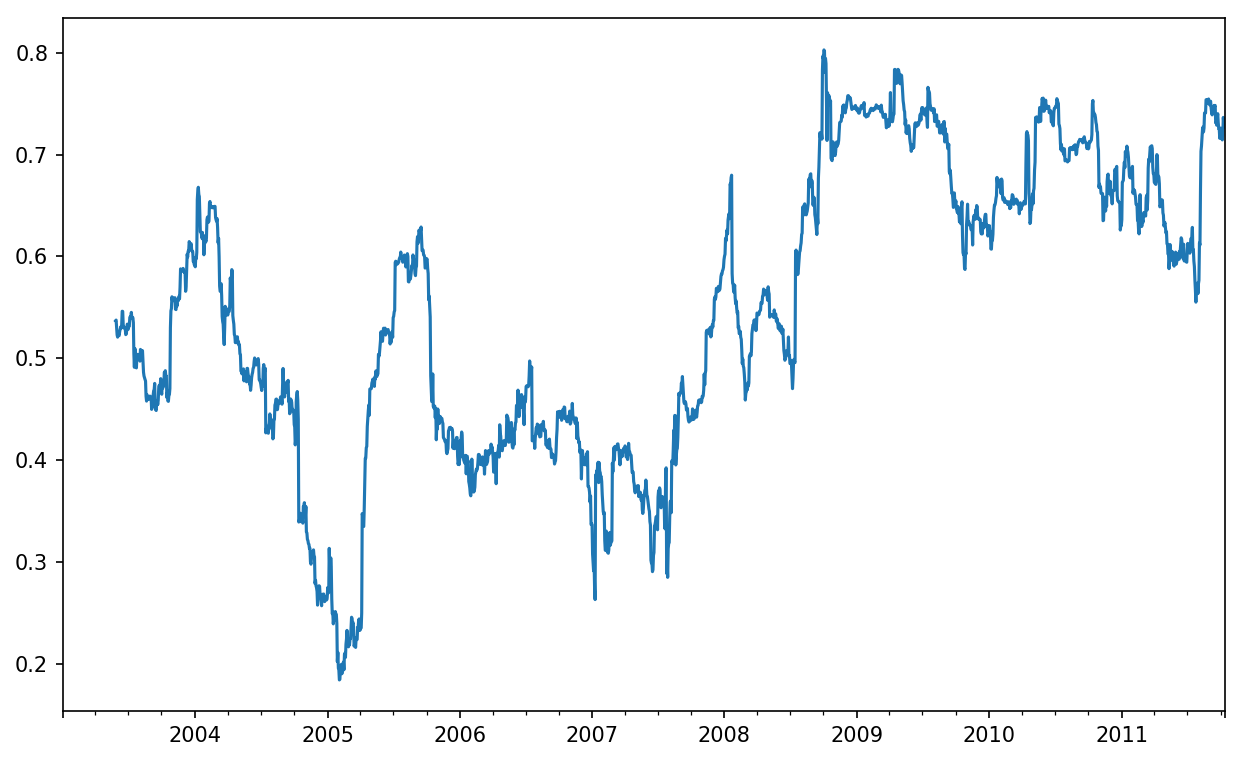

Some statistical operators, like correlation and covariance, need to operate on two time series. As an example, financial analysts are often interested in a stock’s correlation to a benchmark index like the S&P 500. To have a look at this, we first compute the percent change for all of our time series of interest:

In[256]:spx_px=close_px_all['SPX']In[257]:spx_rets=spx_px.pct_change()In[258]:returns=close_px.pct_change()

The corr aggregation function after we call rolling can then compute

the rolling correlation with spx_rets (see Figure 11-8 for the resulting plot):

In[259]:corr=returns.AAPL.rolling(125,min_periods=100).corr(spx_rets)In[260]:corr.plot()

Figure 11-8. Six-month AAPL return correlation to S&P 500

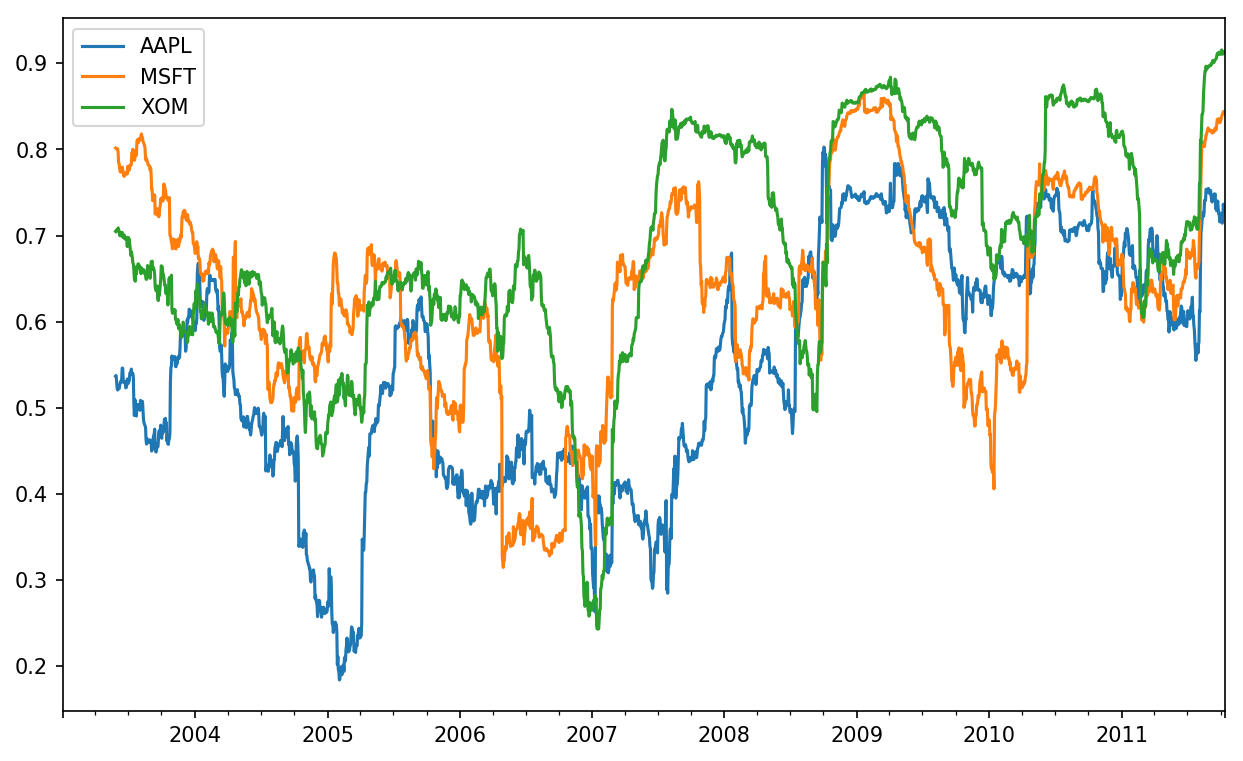

Suppose you wanted to compute the correlation of the S&P 500

index with many stocks at once. Writing a loop and creating a new

DataFrame would be easy but might get repetitive, so if you pass a

Series and a DataFrame, a function like rolling_corr will

compute the correlation of the Series (spx_rets, in this case) with each column in

the DataFrame (see Figure 11-9 for the plot of

the result):

In[262]:corr=returns.rolling(125,min_periods=100).corr(spx_rets)In[263]:corr.plot()

Figure 11-9. Six-month return correlations to S&P 500

User-Defined Moving Window Functions

The apply method on

rolling and related methods provides a means to apply an array

function of your own devising over a moving window. The only requirement

is that the function produce a single value (a reduction) from each

piece of the array. For example, while we can compute sample quantiles

using rolling(...).quantile(q), we

might be interested in the percentile rank of a particular value over

the sample. The scipy.stats.percentileofscore function

does just this (see Figure 11-10 for

the resulting plot):

In[265]:fromscipy.statsimportpercentileofscoreIn[266]:score_at_2percent=lambdax:percentileofscore(x,0.02)In[267]:result=returns.AAPL.rolling(250).apply(score_at_2percent)In[268]:result.plot()

Figure 11-10. Percentile rank of 2% AAPL return over one-year window

If you don’t have SciPy installed already, you can install it with conda or pip.

11.8 Conclusion

Time series data calls for different types of analysis and data transformation tools than the other types of data we have explored in previous chapters.

In the following chapters, we will move on to some advanced pandas methods and show how to start using modeling libraries like statsmodels and scikit-learn.

1 The choice of the default values for closed and label might seem a bit odd to some users.

In practice the choice is somewhat arbitrary; for some target

frequencies, closed='left' is

preferable, while for others closed='right' makes more sense. The

important thing is that you keep in mind exactly how you are

segmenting the data.