Chapter 10. Data Aggregation and Group Operations

Categorizing a dataset and applying a function to each group, whether an

aggregation or transformation, is often a critical component of a data

analysis workflow. After loading, merging, and preparing a dataset, you may

need to compute group statistics or possibly pivot tables for reporting or

visualization purposes. pandas provides a flexible groupby interface, enabling you to slice, dice,

and summarize datasets in a natural way.

One reason for the popularity of relational databases and SQL (which stands for “structured query language”) is the ease with which data can be joined, filtered, transformed, and aggregated. However, query languages like SQL are somewhat constrained in the kinds of group operations that can be performed. As you will see, with the expressiveness of Python and pandas, we can perform quite complex group operations by utilizing any function that accepts a pandas object or NumPy array. In this chapter, you will learn how to:

Split a pandas object into pieces using one or more keys (in the form of functions, arrays, or DataFrame column names)

Calculate group summary statistics, like count, mean, or standard deviation, or a user-defined function

Apply within-group transformations or other manipulations, like normalization, linear regression, rank, or subset selection

Compute pivot tables and cross-tabulations

Perform quantile analysis and other statistical group analyses

Note

Aggregation of time series data, a special use case of groupby, is referred to as

resampling in this book and will receive separate

treatment in Chapter 11.

10.1 GroupBy Mechanics

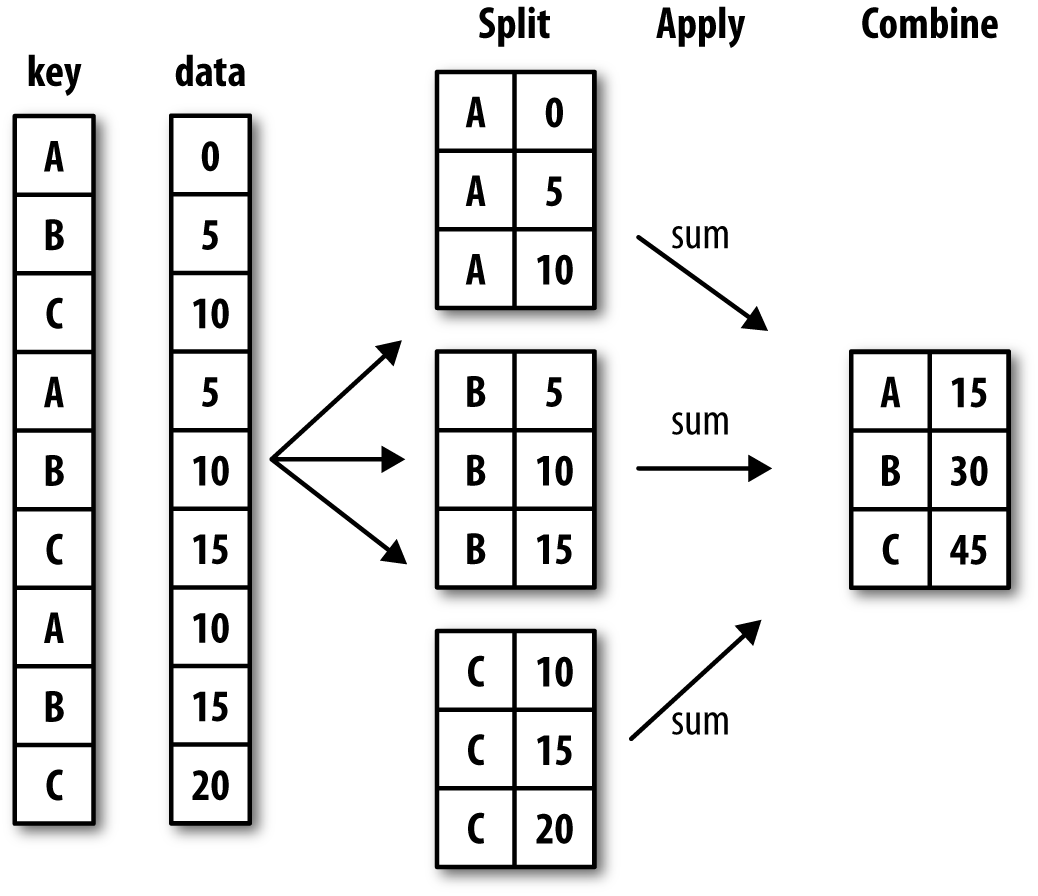

Hadley Wickham, an author of many popular packages for the R programming

language, coined the term split-apply-combine for

describing group operations. In the first stage of the

process, data contained in a pandas object, whether a Series, DataFrame,

or otherwise, is split into groups based on one or

more keys that you provide. The splitting is

performed on a particular axis of an object. For example, a DataFrame can

be grouped on its rows (axis=0) or its

columns (axis=1). Once this is done, a

function is applied to each group, producing a new

value. Finally, the results of all those function applications are

combined into a result object. The form of the

resulting object will usually depend on what’s being done to the data. See

Figure 10-1 for a mockup of a simple group

aggregation.

Figure 10-1. Illustration of a group aggregation

Each grouping key can take many forms, and the keys do not have to be all of the same type:

A list or array of values that is the same length as the axis being grouped

A value indicating a column name in a DataFrame

A dict or Series giving a correspondence between the values on the axis being grouped and the group names

A function to be invoked on the axis index or the individual labels in the index

Note that the latter three methods are shortcuts for producing an array of values to be used to split up the object. Don’t worry if this all seems abstract. Throughout this chapter, I will give many examples of all these methods. To get started, here is a small tabular dataset as a DataFrame:

In[10]:df=pd.DataFrame({'key1':['a','a','b','b','a'],....:'key2':['one','two','one','two','one'],....:'data1':np.random.randn(5),....:'data2':np.random.randn(5)})In[11]:dfOut[11]:data1data2key1key20-0.2047081.393406aone10.4789430.092908atwo2-0.5194390.281746bone3-0.5557300.769023btwo41.9657811.246435aone

Suppose you wanted to compute the mean of the data1 column using the labels from key1. There are a number of ways to do this. One

is to access data1 and call groupby with the column (a Series) at key1:

In[12]:grouped=df['data1'].groupby(df['key1'])In[13]:groupedOut[13]:<pandas.core.groupby.SeriesGroupByobjectat0x7f85008d0400>

This grouped variable is now a

GroupBy object. It has not actually computed anything

yet except for some intermediate data about the group key df['key1']. The idea is that this object has all

of the information needed to then apply some operation to each of the

groups. For example, to compute group means we can call the GroupBy’s mean

method:

In[14]:grouped.mean()Out[14]:key1a0.746672b-0.537585Name:data1,dtype:float64

Later, I’ll explain more about what happens when you call .mean(). The important thing here is that the

data (a Series) has been aggregated according to the group key, producing

a new Series that is now indexed by the unique values in the key1 column. The result index has the name

'key1' because the DataFrame column

df['key1'] did.

If instead we had passed multiple arrays as a list, we’d get something different:

In[15]:means=df['data1'].groupby([df['key1'],df['key2']]).mean()In[16]:meansOut[16]:key1key2aone0.880536two0.478943bone-0.519439two-0.555730Name:data1,dtype:float64

Here we grouped the data using two keys, and the resulting Series now has a hierarchical index consisting of the unique pairs of keys observed:

In[17]:means.unstack()Out[17]:key2onetwokey1a0.8805360.478943b-0.519439-0.555730

In this example, the group keys are all Series, though they could be any arrays of the right length:

In[18]:states=np.array(['Ohio','California','California','Ohio','Ohio'])In[19]:years=np.array([2005,2005,2006,2005,2006])In[20]:df['data1'].groupby([states,years]).mean()Out[20]:California20050.4789432006-0.519439Ohio2005-0.38021920061.965781Name:data1,dtype:float64

Frequently the grouping information is found in the same DataFrame as the data you want to work on. In that case, you can pass column names (whether those are strings, numbers, or other Python objects) as the group keys:

In[21]:df.groupby('key1').mean()Out[21]:data1data2key1a0.7466720.910916b-0.5375850.525384In[22]:df.groupby(['key1','key2']).mean()Out[22]:data1data2key1key2aone0.8805361.319920two0.4789430.092908bone-0.5194390.281746two-0.5557300.769023

You may have noticed in the first case df.groupby('key1').mean() that there is no

key2 column in the result. Because

df['key2'] is not numeric data, it is

said to be a nuisance column, which is therefore

excluded from the result. By default, all of the numeric columns are aggregated, though it is

possible to filter down to a subset, as you’ll see soon.

Regardless of the objective in using groupby, a generally useful GroupBy method is size,

which returns a Series containing group sizes:

In[23]:df.groupby(['key1','key2']).size()Out[23]:key1key2aone2two1bone1two1dtype:int64

Take note that any missing values in a group key will be excluded from the result.

Iterating Over Groups

The GroupBy object supports iteration, generating a sequence of 2-tuples containing the group name along with the chunk of data. Consider the following:

In[24]:forname,groupindf.groupby('key1'):....:(name)....:(group)....:adata1data2key1key20-0.2047081.393406aone10.4789430.092908atwo41.9657811.246435aonebdata1data2key1key22-0.5194390.281746bone3-0.5557300.769023btwo

In the case of multiple keys, the first element in the tuple will be a tuple of key values:

In[25]:for(k1,k2),groupindf.groupby(['key1','key2']):....:((k1,k2))....:(group)....:('a','one')data1data2key1key20-0.2047081.393406aone41.9657811.246435aone('a','two')data1data2key1key210.4789430.092908atwo('b','one')data1data2key1key22-0.5194390.281746bone('b','two')data1data2key1key23-0.555730.769023btwo

Of course, you can choose to do whatever you want with the pieces of data. A recipe you may find useful is computing a dict of the data pieces as a one-liner:

In[26]:pieces=dict(list(df.groupby('key1')))In[27]:pieces['b']Out[27]:data1data2key1key22-0.5194390.281746bone3-0.5557300.769023btwo

By default groupby groups on

axis=0, but you can group on any of

the other axes. For example, we could group the columns of our example

df here by dtype like so:

In[28]:df.dtypesOut[28]:data1float64data2float64key1objectkey2objectdtype:objectIn[29]:grouped=df.groupby(df.dtypes,axis=1)

We can print out the groups like so:

In[30]:fordtype,groupingrouped:....:(dtype)....:(group)....:float64data1data20-0.2047081.39340610.4789430.0929082-0.5194390.2817463-0.5557300.76902341.9657811.246435objectkey1key20aone1atwo2bone3btwo4aone

Selecting a Column or Subset of Columns

Indexing a GroupBy object created from a DataFrame with a column name or array of column names has the effect of column subsetting for aggregation. This means that:

df.groupby('key1')['data1']df.groupby('key1')[['data2']]

are syntactic sugar for:

df['data1'].groupby(df['key1'])df[['data2']].groupby(df['key1'])

Especially for large datasets, it may be desirable to aggregate

only a few columns. For example, in the preceding dataset, to compute

means for just the data2 column and

get the result as a DataFrame, we could write:

In[31]:df.groupby(['key1','key2'])[['data2']].mean()Out[31]:data2key1key2aone1.319920two0.092908bone0.281746two0.769023

The object returned by this indexing operation is a grouped DataFrame if a list or array is passed or a grouped Series if only a single column name is passed as a scalar:

In[32]:s_grouped=df.groupby(['key1','key2'])['data2']In[33]:s_groupedOut[33]:<pandas.core.groupby.SeriesGroupByobjectat0x7f85008983c8>In[34]:s_grouped.mean()Out[34]:key1key2aone1.319920two0.092908bone0.281746two0.769023Name:data2,dtype:float64

Grouping with Dicts and Series

Grouping information may exist in a form other than an array. Let’s consider another example DataFrame:

In[35]:people=pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(5,5),....:columns=['a','b','c','d','e'],....:index=['Joe','Steve','Wes','Jim','Travis'])In[36]:people.iloc[2:3,[1,2]]=np.nan# Add a few NA valuesIn[37]:peopleOut[37]:abcdeJoe1.007189-1.2962210.2749920.2289131.352917Steve0.886429-2.001637-0.3718431.669025-0.438570Wes-0.539741NaNNaN-1.021228-0.577087Jim0.1241210.3026140.5237720.0009401.343810Travis-0.713544-0.831154-2.370232-1.860761-0.860757

Now, suppose I have a group correspondence for the columns and want to sum together the columns by group:

In[38]:mapping={'a':'red','b':'red','c':'blue',....:'d':'blue','e':'red','f':'orange'}

Now, you could construct an array from this dict to pass to

groupby, but instead we can just pass

the dict (I included the key 'f' to highlight that

unused grouping keys are OK):

In[39]:by_column=people.groupby(mapping,axis=1)In[40]:by_column.sum()Out[40]:blueredJoe0.5039051.063885Steve1.297183-1.553778Wes-1.021228-1.116829Jim0.5247121.770545Travis-4.230992-2.405455

The same functionality holds for Series, which can be viewed as a fixed-size mapping:

In[41]:map_series=pd.Series(mapping)In[42]:map_seriesOut[42]:aredbredcbluedblueeredforangedtype:objectIn[43]:people.groupby(map_series,axis=1).count()Out[43]:blueredJoe23Steve23Wes12Jim23Travis23

Grouping with Functions

Using Python functions is a more generic way of defining a group

mapping compared with a dict or Series. Any function passed as a group

key will be called once per index value, with the return values being

used as the group names. More concretely, consider the example DataFrame

from the previous section, which has people’s first names as index

values. Suppose you wanted to group by the length of the names; while

you could compute an array of string lengths, it’s simpler to just pass

the len

function:

In[44]:people.groupby(len).sum()Out[44]:abcde30.591569-0.9936080.798764-0.7913742.11963950.886429-2.001637-0.3718431.669025-0.4385706-0.713544-0.831154-2.370232-1.860761-0.860757

Mixing functions with arrays, dicts, or Series is not a problem as everything gets converted to arrays internally:

In[45]:key_list=['one','one','one','two','two']In[46]:people.groupby([len,key_list]).min()Out[46]:abcde3one-0.539741-1.2962210.274992-1.021228-0.577087two0.1241210.3026140.5237720.0009401.3438105one0.886429-2.001637-0.3718431.669025-0.4385706two-0.713544-0.831154-2.370232-1.860761-0.860757

Grouping by Index Levels

A final convenience for hierarchically indexed datasets is the ability to aggregate using one of the levels of an axis index. Let’s look at an example:

In[47]:columns=pd.MultiIndex.from_arrays([['US','US','US','JP','JP'],....:[1,3,5,1,3]],....:names=['cty','tenor'])In[48]:hier_df=pd.DataFrame(np.random.randn(4,5),columns=columns)In[49]:hier_dfOut[49]:ctyUSJPtenor1351300.560145-1.2659340.119827-1.0635120.3328831-2.359419-0.199543-1.541996-0.970736-1.30703020.2863500.377984-0.7538870.3312861.34974230.0698770.246674-0.0118621.0048121.327195

To group by level, pass the level number or name using the level

keyword:

In[50]:hier_df.groupby(level='cty',axis=1).count()Out[50]:ctyJPUS023123223323

10.2 Data Aggregation

Aggregations refer to any data transformation that produces scalar values from arrays.

The preceding examples have used several of them, including mean, count, min, and sum. You may wonder what is going on when you

invoke mean() on a GroupBy object. Many

common aggregations, such as those found in Table 10-1, have optimized implementations. However, you are not limited to

only this set of methods.

You can use aggregations of your own devising and additionally call

any method that is also defined on the grouped object. For example, you

might recall that quantile computes

sample quantiles of a Series or a DataFrame’s columns.

While quantile is not explicitly

implemented for GroupBy, it is a Series method and thus available for use.

Internally, GroupBy efficiently slices up the Series, calls piece.quantile(0.9) for each piece, and then

assembles those results together into the result object:

In[51]:dfOut[51]:data1data2key1key20-0.2047081.393406aone10.4789430.092908atwo2-0.5194390.281746bone3-0.5557300.769023btwo41.9657811.246435aoneIn[52]:grouped=df.groupby('key1')In[53]:grouped['data1'].quantile(0.9)Out[53]:key1a1.668413b-0.523068Name:data1,dtype:float64

To use your own aggregation functions, pass any function that

aggregates an array to the aggregate or

agg method:

In[54]:defpeak_to_peak(arr):....:returnarr.max()-arr.min()In[55]:grouped.agg(peak_to_peak)Out[55]:data1data2key1a2.1704881.300498b0.0362920.487276

You may notice that some methods like describe also work,

even though they are not aggregations, strictly speaking:

In[56]:grouped.describe()Out[56]:data1\countmeanstdmin25%50%75%key1a3.00.7466721.109736-0.2047080.1371180.4789431.222362b2.0-0.5375850.025662-0.555730-0.546657-0.537585-0.528512data2\maxcountmeanstdmin25%50%key1a1.9657813.00.9109160.7122170.0929080.6696711.246435b-0.5194392.00.5253840.3445560.2817460.4035650.52538475%maxkey1a1.3199201.393406b0.6472030.769023

I will explain in more detail what has happened here in Section 10.3, “Apply: General split-apply-combine,”.

Note

Custom aggregation functions are generally much slower than the optimized functions found in Table 10-1. This is because there is some extra overhead (function calls, data rearrangement) in constructing the intermediate group data chunks.

Column-Wise and Multiple Function Application

Let’s return to the tipping dataset from earlier examples. After loading it

with read_csv, we add a

tipping percentage column tip_pct:

In[57]:tips=pd.read_csv('examples/tips.csv')# Add tip percentage of total billIn[58]:tips['tip_pct']=tips['tip']/tips['total_bill']In[59]:tips[:6]Out[59]:total_billtipsmokerdaytimesizetip_pct016.991.01NoSunDinner20.059447110.341.66NoSunDinner30.160542221.013.50NoSunDinner30.166587323.683.31NoSunDinner20.139780424.593.61NoSunDinner40.146808525.294.71NoSunDinner40.186240

As you’ve already seen, aggregating a Series or all of the columns

of a DataFrame is a matter of using aggregate with the desired function or calling

a method like mean or std. However, you may want to aggregate using

a different function depending on the column, or multiple functions at

once. Fortunately, this is possible to do, which I’ll illustrate through

a number of examples. First, I’ll group the tips by day

and smoker:

In[60]:grouped=tips.groupby(['day','smoker'])

Note that for descriptive statistics like those in Table 10-1, you can pass the name of the function as a string:

In[61]:grouped_pct=grouped['tip_pct']In[62]:grouped_pct.agg('mean')Out[62]:daysmokerFriNo0.151650Yes0.174783SatNo0.158048Yes0.147906SunNo0.160113Yes0.187250ThurNo0.160298Yes0.163863Name:tip_pct,dtype:float64

If you pass a list of functions or function names instead, you get back a DataFrame with column names taken from the functions:

In[63]:grouped_pct.agg(['mean','std',peak_to_peak])Out[63]:meanstdpeak_to_peakdaysmokerFriNo0.1516500.0281230.067349Yes0.1747830.0512930.159925SatNo0.1580480.0397670.235193Yes0.1479060.0613750.290095SunNo0.1601130.0423470.193226Yes0.1872500.1541340.644685ThurNo0.1602980.0387740.193350Yes0.1638630.0393890.151240

Here we passed a list of aggregation functions to

agg to evaluate indepedently on the data

groups.

You don’t need to accept the names that GroupBy gives to the

columns; notably, lambda functions

have the name '<lambda>', which

makes them hard to identify (you can see for yourself by looking at a

function’s __name__ attribute). Thus, if you pass a list of (name,

function) tuples, the first element of each tuple will be used

as the DataFrame column names (you can think of a list of 2-tuples as an

ordered mapping):

In[64]:grouped_pct.agg([('foo','mean'),('bar',np.std)])Out[64]:foobardaysmokerFriNo0.1516500.028123Yes0.1747830.051293SatNo0.1580480.039767Yes0.1479060.061375SunNo0.1601130.042347Yes0.1872500.154134ThurNo0.1602980.038774Yes0.1638630.039389

With a DataFrame you have more options, as you can specify a list

of functions to apply to all of the columns or different functions per

column. To start, suppose we wanted to compute the same three statistics

for the tip_pct and total_bill columns:

In[65]:functions=['count','mean','max']In[66]:result=grouped['tip_pct','total_bill'].agg(functions)In[67]:resultOut[67]:tip_pcttotal_billcountmeanmaxcountmeanmaxdaysmokerFriNo40.1516500.187735418.42000022.75Yes150.1747830.2634801516.81333340.17SatNo450.1580480.2919904519.66177848.33Yes420.1479060.3257334221.27666750.81SunNo570.1601130.2526725720.50666748.17Yes190.1872500.7103451924.12000045.35ThurNo450.1602980.2663124517.11311141.19Yes170.1638630.2412551719.19058843.11

As you can see, the resulting DataFrame has hierarchical columns,

the same as you would get aggregating each column separately and

using concat to glue

the results together using the column names as the keys argument:

In[68]:result['tip_pct']Out[68]:countmeanmaxdaysmokerFriNo40.1516500.187735Yes150.1747830.263480SatNo450.1580480.291990Yes420.1479060.325733SunNo570.1601130.252672Yes190.1872500.710345ThurNo450.1602980.266312Yes170.1638630.241255

As before, a list of tuples with custom names can be passed:

In[69]:ftuples=[('Durchschnitt','mean'),('Abweichung',np.var)]In[70]:grouped['tip_pct','total_bill'].agg(ftuples)Out[70]:tip_pcttotal_billDurchschnittAbweichungDurchschnittAbweichungdaysmokerFriNo0.1516500.00079118.42000025.596333Yes0.1747830.00263116.81333382.562438SatNo0.1580480.00158119.66177879.908965Yes0.1479060.00376721.276667101.387535SunNo0.1601130.00179320.50666766.099980Yes0.1872500.02375724.120000109.046044ThurNo0.1602980.00150317.11311159.625081Yes0.1638630.00155119.19058869.808518

Now, suppose you wanted to apply potentially different functions

to one or more of the columns. To do this, pass a dict to agg that contains a mapping of column names to

any of the function specifications listed so far:

In[71]:grouped.agg({'tip':np.max,'size':'sum'})Out[71]:tipsizedaysmokerFriNo3.509Yes4.7331SatNo9.00115Yes10.00104SunNo6.00167Yes6.5049ThurNo6.70112Yes5.0040In[72]:grouped.agg({'tip_pct':['min','max','mean','std'],....:'size':'sum'})Out[72]:tip_pctsizeminmaxmeanstdsumdaysmokerFriNo0.1203850.1877350.1516500.0281239Yes0.1035550.2634800.1747830.05129331SatNo0.0567970.2919900.1580480.039767115Yes0.0356380.3257330.1479060.061375104SunNo0.0594470.2526720.1601130.042347167Yes0.0656600.7103450.1872500.15413449ThurNo0.0729610.2663120.1602980.038774112Yes0.0900140.2412550.1638630.03938940

A DataFrame will have hierarchical columns only if multiple functions are applied to at least one column.

Returning Aggregated Data Without Row Indexes

In all of the examples up until now, the aggregated data comes back with

an index, potentially hierarchical, composed from the unique group key

combinations. Since this isn’t always desirable, you can disable this

behavior in most cases by passing as_index=False to groupby:

In[73]:tips.groupby(['day','smoker'],as_index=False).mean()Out[73]:daysmokertotal_billtipsizetip_pct0FriNo18.4200002.8125002.2500000.1516501FriYes16.8133332.7140002.0666670.1747832SatNo19.6617783.1028892.5555560.1580483SatYes21.2766672.8754762.4761900.1479064SunNo20.5066673.1678952.9298250.1601135SunYes24.1200003.5168422.5789470.1872506ThurNo17.1131112.6737782.4888890.1602987ThurYes19.1905883.0300002.3529410.163863

Of course, it’s always possible to obtain the result in this

format by calling reset_index on

the result. Using the as_index=False method avoids

some unnecessary computations.

10.3 Apply: General split-apply-combine

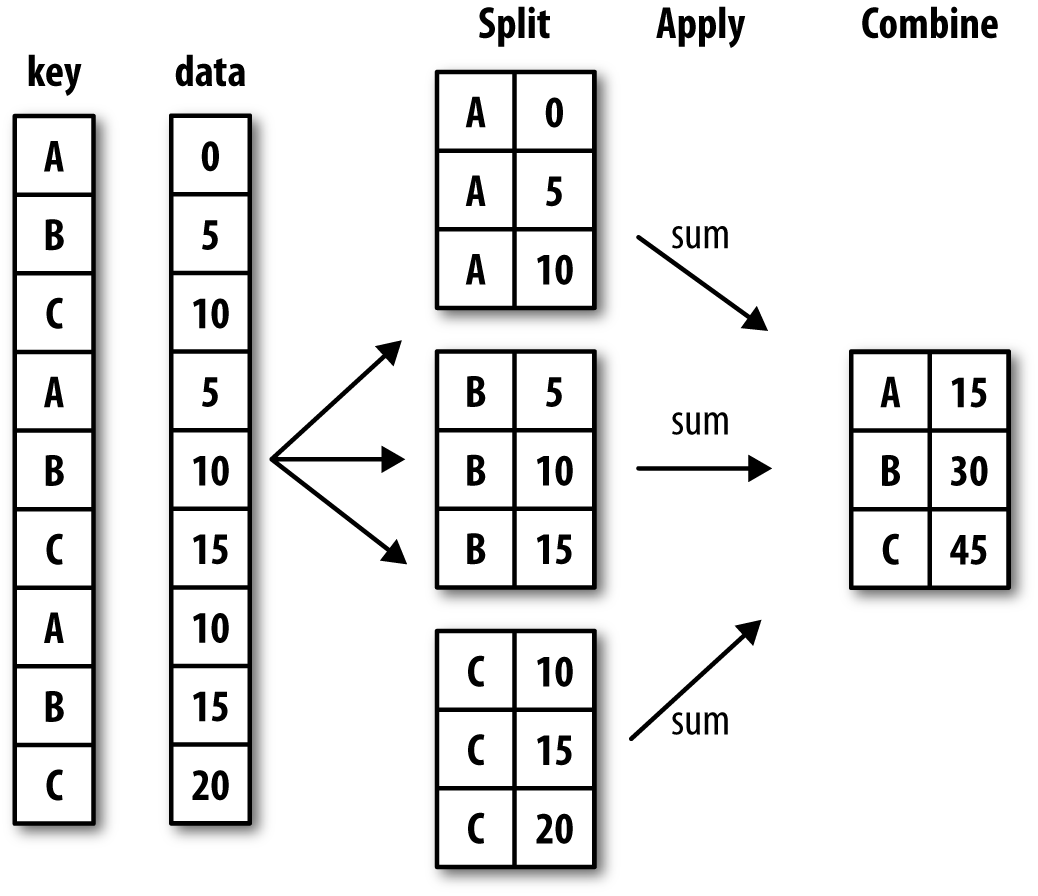

The most general-purpose GroupBy method is apply,

which is the subject of the rest of this section. As

illustrated in Figure 10-2, apply splits the object being manipulated into

pieces, invokes the passed function on each piece, and then attempts to

concatenate the pieces together.

Figure 10-2. Illustration of a group aggregation

Returning to the tipping dataset from before, suppose you wanted to

select the top five tip_pct values by

group. First, write a function that selects the rows with the largest

values in a particular column:

In[74]:deftop(df,n=5,column='tip_pct'):....:returndf.sort_values(by=column)[-n:]In[75]:top(tips,n=6)Out[75]:total_billtipsmokerdaytimesizetip_pct10914.314.00YesSatDinner20.27952518323.176.50YesSunDinner40.28053523211.613.39NoSatDinner20.291990673.071.00YesSatDinner10.3257331789.604.00YesSunDinner20.4166671727.255.15YesSunDinner20.710345

Now, if we group by smoker, say,

and call apply with this function, we

get the following:

In[76]:tips.groupby('smoker').apply(top)Out[76]:total_billtipsmokerdaytimesizetip_pctsmokerNo8824.715.85NoThurLunch20.23674618520.695.00NoSunDinner50.2416635110.292.60NoSunDinner20.2526721497.512.00NoThurLunch20.26631223211.613.39NoSatDinner20.291990Yes10914.314.00YesSatDinner20.27952518323.176.50YesSunDinner40.280535673.071.00YesSatDinner10.3257331789.604.00YesSunDinner20.4166671727.255.15YesSunDinner20.710345

What has happened here? The top

function is called on each row group from the DataFrame, and then the

results are glued together using pandas.concat, labeling the pieces with the

group names. The result therefore has a hierarchical index whose inner

level contains index values from the original DataFrame.

If you pass a function to apply

that takes other arguments or keywords, you can pass these after the

function:

In[77]:tips.groupby(['smoker','day']).apply(top,n=1,column='total_bill')Out[77]:total_billtipsmokerdaytimesizetip_pctsmokerdayNoFri9422.753.25NoFriDinner20.142857Sat21248.339.00NoSatDinner40.186220Sun15648.175.00NoSunDinner60.103799Thur14241.195.00NoThurLunch50.121389YesFri9540.174.73YesFriDinner40.117750Sat17050.8110.00YesSatDinner30.196812Sun18245.353.50YesSunDinner30.077178Thur19743.115.00YesThurLunch40.115982

Note

Beyond these basic usage mechanics, getting the most out of

apply may require some creativity.

What occurs inside the function passed is up to you; it only needs to

return a pandas object or a scalar value. The rest of this chapter will

mainly consist of examples showing you how to solve various problems

using groupby.

You may recall that I earlier called describe on a GroupBy object:

In[78]:result=tips.groupby('smoker')['tip_pct'].describe()In[79]:resultOut[79]:countmeanstdmin25%50%75%\smokerNo151.00.1593280.0399100.0567970.1369060.1556250.185014Yes93.00.1631960.0851190.0356380.1067710.1538460.195059maxsmokerNo0.291990Yes0.710345In[80]:result.unstack('smoker')Out[80]:smokercountNo151.000000Yes93.000000meanNo0.159328Yes0.163196stdNo0.039910Yes0.085119minNo0.056797Yes0.03563825%No0.136906Yes0.10677150%No0.155625Yes0.15384675%No0.185014Yes0.195059maxNo0.291990Yes0.710345dtype:float64

Inside GroupBy, when you invoke a method like describe, it is actually just a shortcut

for:

f=lambdax:x.describe()grouped.apply(f)

Suppressing the Group Keys

In the preceding examples, you see that the resulting object has a hierarchical index

formed from the group keys along with the indexes of each piece of the

original object. You can disable this by passing group_keys=False to groupby:

In[81]:tips.groupby('smoker',group_keys=False).apply(top)Out[81]:total_billtipsmokerdaytimesizetip_pct8824.715.85NoThurLunch20.23674618520.695.00NoSunDinner50.2416635110.292.60NoSunDinner20.2526721497.512.00NoThurLunch20.26631223211.613.39NoSatDinner20.29199010914.314.00YesSatDinner20.27952518323.176.50YesSunDinner40.280535673.071.00YesSatDinner10.3257331789.604.00YesSunDinner20.4166671727.255.15YesSunDinner20.710345

Quantile and Bucket Analysis

As you may recall from Chapter 8, pandas has some tools,

in particular cut and qcut, for slicing data up into buckets with bins of your choosing or

by sample quantiles. Combining these functions with groupby makes it convenient to perform

bucket or quantile analysis on a dataset. Consider a simple random

dataset and an equal-length bucket categorization using cut:

In[82]:frame=pd.DataFrame({'data1':np.random.randn(1000),....:'data2':np.random.randn(1000)})In[83]:quartiles=pd.cut(frame.data1,4)In[84]:quartiles[:10]Out[84]:0(-1.23,0.489]1(-2.956,-1.23]2(-1.23,0.489]3(0.489,2.208]4(-1.23,0.489]5(0.489,2.208]6(-1.23,0.489]7(-1.23,0.489]8(0.489,2.208]9(0.489,2.208]Name:data1,dtype:categoryCategories(4,interval[float64]):[(-2.956,-1.23]<(-1.23,0.489]<(0.489,2.208]<(2.208,3.928]]

The Categorical object

returned by cut can be

passed directly to groupby. So we

could compute a set of statistics for the data2 column like so:

In[85]:defget_stats(group):....:return{'min':group.min(),'max':group.max(),....:'count':group.count(),'mean':group.mean()}In[86]:grouped=frame.data2.groupby(quartiles)In[87]:grouped.apply(get_stats).unstack()Out[87]:countmaxmeanmindata1(-2.956,-1.23]95.01.670835-0.039521-3.399312(-1.23,0.489]598.03.260383-0.002051-2.989741(0.489,2.208]297.02.9544390.081822-3.745356(2.208,3.928]10.01.7656400.024750-1.929776

These were equal-length buckets; to compute equal-size buckets

based on sample quantiles, use qcut.

I’ll pass labels=False to just get

quantile numbers:

# Return quantile numbersIn[88]:grouping=pd.qcut(frame.data1,10,labels=False)In[89]:grouped=frame.data2.groupby(grouping)In[90]:grouped.apply(get_stats).unstack()Out[90]:countmaxmeanmindata10100.01.670835-0.049902-3.3993121100.02.6284410.030989-1.9500982100.02.527939-0.067179-2.9251133100.03.2603830.065713-2.3155554100.02.074345-0.111653-2.0479395100.02.1848100.052130-2.9897416100.02.458842-0.021489-2.2235067100.02.954439-0.026459-3.0569908100.02.7355270.103406-3.7453569100.02.3770200.220122-2.064111

We will take a closer look at pandas’s

Categorical type in Chapter 12.

Example: Filling Missing Values with Group-Specific Values

When cleaning up missing data, in some cases you will replace data

observations using dropna, but in

others you may want to impute (fill in) the null (NA) values using a

fixed value or some value derived from the data. fillna is the right tool to use; for example, here I fill in NA values

with the mean:

In[91]:s=pd.Series(np.random.randn(6))In[92]:s[::2]=np.nanIn[93]:sOut[93]:0NaN1-0.1259212NaN3-0.8844754NaN50.227290dtype:float64In[94]:s.fillna(s.mean())Out[94]:0-0.2610351-0.1259212-0.2610353-0.8844754-0.26103550.227290dtype:float64

Suppose you need the fill value to vary by group. One way to do

this is to group the data and use apply with a function that calls fillna on each data chunk. Here is some sample

data on US states divided into eastern and western regions:

In[95]:states=['Ohio','New York','Vermont','Florida',....:'Oregon','Nevada','California','Idaho']In[96]:group_key=['East']*4+['West']*4In[97]:data=pd.Series(np.random.randn(8),index=states)In[98]:dataOut[98]:Ohio0.922264NewYork-2.153545Vermont-0.365757Florida-0.375842Oregon0.329939Nevada0.981994California1.105913Idaho-1.613716dtype:float64

Note that the syntax ['East'] * 4 produces a

list containing four copies of the elements in

['East']. Adding lists together concatenates

them.

Let’s set some values in the data to be missing:

In[99]:data[['Vermont','Nevada','Idaho']]=np.nanIn[100]:dataOut[100]:Ohio0.922264NewYork-2.153545VermontNaNFlorida-0.375842Oregon0.329939NevadaNaNCalifornia1.105913IdahoNaNdtype:float64In[101]:data.groupby(group_key).mean()Out[101]:East-0.535707West0.717926dtype:float64

We can fill the NA values using the group means like so:

In[102]:fill_mean=lambdag:g.fillna(g.mean())In[103]:data.groupby(group_key).apply(fill_mean)Out[103]:Ohio0.922264NewYork-2.153545Vermont-0.535707Florida-0.375842Oregon0.329939Nevada0.717926California1.105913Idaho0.717926dtype:float64

In another case, you might have predefined fill values in your

code that vary by group. Since the groups have a name attribute set internally, we can use

that:

In[104]:fill_values={'East':0.5,'West':-1}In[105]:fill_func=lambdag:g.fillna(fill_values[g.name])In[106]:data.groupby(group_key).apply(fill_func)Out[106]:Ohio0.922264NewYork-2.153545Vermont0.500000Florida-0.375842Oregon0.329939Nevada-1.000000California1.105913Idaho-1.000000dtype:float64

Example: Random Sampling and Permutation

Suppose you wanted to draw a random sample (with or without replacement) from a

large dataset for Monte Carlo simulation purposes or some other

application. There are a number of ways to perform the “draws”; here we

use the sample method for

Series.

To demonstrate, here’s a way to construct a deck of English-style playing cards:

# Hearts, Spades, Clubs, Diamondssuits=['H','S','C','D']card_val=(list(range(1,11))+[10]*3)*4base_names=['A']+list(range(2,11))+['J','K','Q']cards=[]forsuitin['H','S','C','D']:cards.extend(str(num)+suitfornuminbase_names)deck=pd.Series(card_val,index=cards)

So now we have a Series of length 52 whose index contains card

names and values are the ones used in Blackjack and other games (to keep

things simple, I just let the ace 'A' be 1):

In[108]:deck[:13]Out[108]:AH12H23H34H45H56H67H78H89H910H10JH10KH10QH10dtype:int64

Now, based on what I said before, drawing a hand of five cards from the deck could be written as:

In[109]:defdraw(deck,n=5):.....:returndeck.sample(n)In[110]:draw(deck)Out[110]:AD18C85H5KC102C2dtype:int64

Suppose you wanted two random cards from each suit. Because the

suit is the last character of each card name, we can group based on this

and use apply:

In[111]:get_suit=lambdacard:card[-1]# last letter is suitIn[112]:deck.groupby(get_suit).apply(draw,n=2)Out[112]:C2C23C3DKD108D8HKH103H3S2S24S4dtype:int64

Alternatively, we could write:

In[113]:deck.groupby(get_suit,group_keys=False).apply(draw,n=2)Out[113]:KC10JC10AD15D55H56H67S7KS10dtype:int64

Example: Group Weighted Average and Correlation

Under the split-apply-combine paradigm of groupby,

operations between columns in a DataFrame or two Series, such as a group

weighted average, are possible. As an example, take this dataset

containing group keys, values, and some weights:

In[114]:df=pd.DataFrame({'category':['a','a','a','a',.....:'b','b','b','b'],.....:'data':np.random.randn(8),.....:'weights':np.random.rand(8)})In[115]:dfOut[115]:categorydataweights0a1.5615870.9575151a1.2199840.3472672a-0.4822390.5813623a0.3156670.2170914b-0.0478520.8944065b-0.4541450.9185646b-0.5567740.2778257b0.2533210.955905

The group weighted average by category would then be:

In[116]:grouped=df.groupby('category')In[117]:get_wavg=lambdag:np.average(g['data'],weights=g['weights'])In[118]:grouped.apply(get_wavg)Out[118]:categorya0.811643b-0.122262dtype:float64

As another example, consider a financial dataset originally

obtained from Yahoo! Finance containing end-of-day prices for a few

stocks and the S&P 500 index (the SPX symbol):

In[119]:close_px=pd.read_csv('examples/stock_px_2.csv',parse_dates=True,.....:index_col=0)In[120]:close_px.info()<class'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>DatetimeIndex:2214entries,2003-01-02to2011-10-14Datacolumns(total4columns):AAPL2214non-nullfloat64MSFT2214non-nullfloat64XOM2214non-nullfloat64SPX2214non-nullfloat64dtypes:float64(4)memoryusage:86.5KBIn[121]:close_px[-4:]Out[121]:AAPLMSFTXOMSPX2011-10-11400.2927.0076.271195.542011-10-12402.1926.9677.161207.252011-10-13408.4327.1876.371203.662011-10-14422.0027.2778.111224.58

One task of interest might be to compute a DataFrame consisting of

the yearly correlations of daily returns (computed from percent changes)

with SPX. As one way to do this, we

first create a function that computes the pairwise correlation of each

column with the 'SPX' column:

In[122]:spx_corr=lambdax:x.corrwith(x['SPX'])

Next, we compute percent change on close_px

using pct_change:

In[123]:rets=close_px.pct_change().dropna()

Lastly, we group these percent changes by year, which can be

extracted from each row label with a one-line function that returns the

year attribute of each datetime

label:

In[124]:get_year=lambdax:x.yearIn[125]:by_year=rets.groupby(get_year)In[126]:by_year.apply(spx_corr)Out[126]:AAPLMSFTXOMSPX20030.5411240.7451740.6612651.020040.3742830.5885310.5577421.020050.4675400.5623740.6310101.020060.4282670.4061260.5185141.020070.5081180.6587700.7862641.020080.6814340.8046260.8283031.020090.7071030.6549020.7979211.020100.7101050.7301180.8390571.020110.6919310.8009960.8599751.0

You could also compute inter-column correlations. Here we compute the annual correlation between Apple and Microsoft:

In[127]:by_year.apply(lambdag:g['AAPL'].corr(g['MSFT']))Out[127]:20030.48086820040.25902420050.30009320060.16173520070.41773820080.61190120090.43273820100.57194620110.581987dtype:float64

Example: Group-Wise Linear Regression

In the same theme as the previous example, you can use groupby to perform more complex group-wise

statistical analysis, as long as the function returns a pandas object or

scalar value. For example, I can define the following regress function (using the statsmodels

econometrics library), which executes an ordinary least squares (OLS)

regression on each chunk of data:

importstatsmodels.apiassmdefregress(data,yvar,xvars):Y=data[yvar]X=data[xvars]X['intercept']=1.result=sm.OLS(Y,X).fit()returnresult.params

Now, to run a yearly linear regression of AAPL on SPX

returns, execute:

In[129]:by_year.apply(regress,'AAPL',['SPX'])Out[129]:SPXintercept20031.1954060.00071020041.3634630.00420120051.7664150.00324620061.6454960.00008020071.1987610.00343820080.968016-0.00111020090.8791030.00295420101.0526080.00126120110.8066050.001514

10.4 Pivot Tables and Cross-Tabulation

A pivot table is a data summarization tool

frequently found in spreadsheet programs and other data

analysis software. It aggregates a table of data by one or more keys,

arranging the data in a rectangle with some of the group keys along the

rows and some along the columns. Pivot tables in Python with pandas are

made possible through the groupby

facility described in this chapter combined with reshape operations

utilizing hierarchical indexing. DataFrame has a pivot_table method, and there is also a top-level pandas.pivot_table function. In addition to

providing a convenience interface to groupby, pivot_table can add partial totals, also known

as margins.

Returning to the tipping dataset, suppose you wanted to compute a

table of group means (the default pivot_table aggregation type) arranged by

day and smoker on the rows:

In[130]:tips.pivot_table(index=['day','smoker'])Out[130]:sizetiptip_pcttotal_billdaysmokerFriNo2.2500002.8125000.15165018.420000Yes2.0666672.7140000.17478316.813333SatNo2.5555563.1028890.15804819.661778Yes2.4761902.8754760.14790621.276667SunNo2.9298253.1678950.16011320.506667Yes2.5789473.5168420.18725024.120000ThurNo2.4888892.6737780.16029817.113111Yes2.3529413.0300000.16386319.190588

This could have been produced with groupby directly. Now, suppose we want to

aggregate only tip_pct and size, and additionally group by time. I’ll put smoker in the table columns and day in the rows:

In[131]:tips.pivot_table(['tip_pct','size'],index=['time','day'],.....:columns='smoker')Out[131]:sizetip_pctsmokerNoYesNoYestimedayDinnerFri2.0000002.2222220.1396220.165347Sat2.5555562.4761900.1580480.147906Sun2.9298252.5789470.1601130.187250Thur2.000000NaN0.159744NaNLunchFri3.0000001.8333330.1877350.188937Thur2.5000002.3529410.1603110.163863

We could augment this table to include partial totals by passing

margins=True. This has the effect of

adding All row and column labels, with

corresponding values being the group statistics for all the data within a

single tier:

In[132]:tips.pivot_table(['tip_pct','size'],index=['time','day'],.....:columns='smoker',margins=True)Out[132]:sizetip_pctsmokerNoYesAllNoYesAlltimedayDinnerFri2.0000002.2222222.1666670.1396220.1653470.158916Sat2.5555562.4761902.5172410.1580480.1479060.153152Sun2.9298252.5789472.8421050.1601130.1872500.166897Thur2.000000NaN2.0000000.159744NaN0.159744LunchFri3.0000001.8333332.0000000.1877350.1889370.188765Thur2.5000002.3529412.4590160.1603110.1638630.161301All2.6688742.4086022.5696720.1593280.1631960.160803

Here, the All values are means

without taking into account smoker versus non-smoker (the All columns) or any of the two levels of

grouping on the rows (the All

row).

To use a different aggregation function, pass it to aggfunc. For example, 'count' or len will give you a cross-tabulation (count or

frequency) of group sizes:

In[133]:tips.pivot_table('tip_pct',index=['time','smoker'],columns='day',.....:aggfunc=len,margins=True)Out[133]:dayFriSatSunThurAlltimesmokerDinnerNo3.045.057.01.0106.0Yes9.042.019.0NaN70.0LunchNo1.0NaNNaN44.045.0Yes6.0NaNNaN17.023.0All19.087.076.062.0244.0

If some combinations are empty (or otherwise NA), you may wish to

pass a fill_value:

In[134]:tips.pivot_table('tip_pct',index=['time','size','smoker'],.....:columns='day',aggfunc='mean',fill_value=0)Out[134]:dayFriSatSunThurtimesizesmokerDinner1No0.0000000.1379310.0000000.000000Yes0.0000000.3257330.0000000.0000002No0.1396220.1627050.1688590.159744Yes0.1712970.1486680.2078930.0000003No0.0000000.1546610.1526630.000000Yes0.0000000.1449950.1526600.0000004No0.0000000.1500960.1481430.000000Yes0.1177500.1245150.1933700.0000005No0.0000000.0000000.2069280.000000Yes0.0000000.1065720.0656600.000000...............Lunch1No0.0000000.0000000.0000000.181728Yes0.2237760.0000000.0000000.0000002No0.0000000.0000000.0000000.166005Yes0.1819690.0000000.0000000.1588433No0.1877350.0000000.0000000.084246Yes0.0000000.0000000.0000000.2049524No0.0000000.0000000.0000000.138919Yes0.0000000.0000000.0000000.1554105No0.0000000.0000000.0000000.1213896No0.0000000.0000000.0000000.173706[21rowsx4columns]

See Table 10-2 for a summary of pivot_table methods.

Cross-Tabulations: Crosstab

A cross-tabulation (or crosstab for short) is a special case of a pivot table that computes group frequencies. Here is an example:

In[138]:dataOut[138]:SampleNationalityHandedness01USARight-handed12JapanLeft-handed23USARight-handed34JapanRight-handed45JapanLeft-handed56JapanRight-handed67USARight-handed78USALeft-handed89JapanRight-handed910USARight-handed

As part of some survey analysis, we might want to summarize this

data by nationality and handedness. You could use pivot_table to do this, but the pandas.crosstab function can be more convenient:

In[139]:pd.crosstab(data.Nationality,data.Handedness,margins=True)Out[139]:HandednessLeft-handedRight-handedAllNationalityJapan235USA145All3710

The first two arguments to crosstab can each either be an array or Series

or a list of arrays. As in the tips data:

In[140]:pd.crosstab([tips.time,tips.day],tips.smoker,margins=True)Out[140]:smokerNoYesAlltimedayDinnerFri3912Sat454287Sun571976Thur101LunchFri167Thur441761All15193244

10.5 Conclusion

Mastering pandas’s data grouping tools can help both with data

cleaning as well as modeling or statistical analysis work. In Chapter 14 we will look at several more example

use cases for groupby on real data.

In the next chapter, we turn our attention to time series data.