Appendix A. Advanced NumPy

In this appendix, I will go deeper into the NumPy library for array computing. This will include more internal detail about the ndarray type and more advanced array manipulations and algorithms.

This appendix contains miscellaneous topics and does not necessarily need to be read linearly.

A.1 ndarray Object Internals

The NumPy ndarray provides a means to interpret a block of homogeneous data (either contiguous or strided) as a multidimensional array object. The data type, or dtype, determines how the data is interpreted as being floating point, integer, boolean, or any of the other types we’ve been looking at.

Part of what makes ndarray flexible is that every array object is a

strided view on a block of data. You might wonder,

for example, how the array view arr[::2,

::-1] does not copy any data. The reason is that the ndarray is

more than just a chunk of memory and a dtype; it also has “striding”

information that enables the array to move through memory with varying

step sizes. More precisely, the ndarray internally consists of the

following:

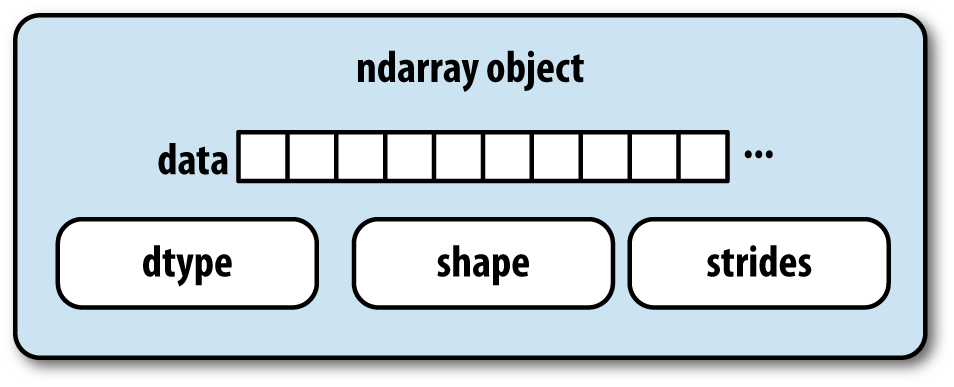

A pointer to data—that is, a block of data in RAM or in a memory-mapped file

The data type or dtype, describing fixed-size value cells in the array

A tuple indicating the array’s shape

A tuple of strides, integers indicating the number of bytes to “step” in order to advance one element along a dimension

See Figure A-1 for a simple mockup of the ndarray innards.

For example, a 10 × 5 array would have shape (10, 5):

In[10]:np.ones((10,5)).shapeOut[10]:(10,5)

A typical (C order) 3 × 4 × 5 array of float64 (8-byte) values has strides (160, 40, 8) (knowing about the strides can be

useful because, in general, the larger the strides on a particular axis,

the more costly it is to perform computation along that axis):

In[11]:np.ones((3,4,5),dtype=np.float64).stridesOut[11]:(160,40,8)

While it is rare that a typical NumPy user would be interested in

the array strides, they are the critical ingredient in

constructing “zero-copy” array views. Strides can even be negative,

which enables an array to move “backward” through memory (this would be

the case, for example, in a slice like obj[::-1] or obj[:,

::-1]).

Figure A-1. The NumPy ndarray object

NumPy dtype Hierarchy

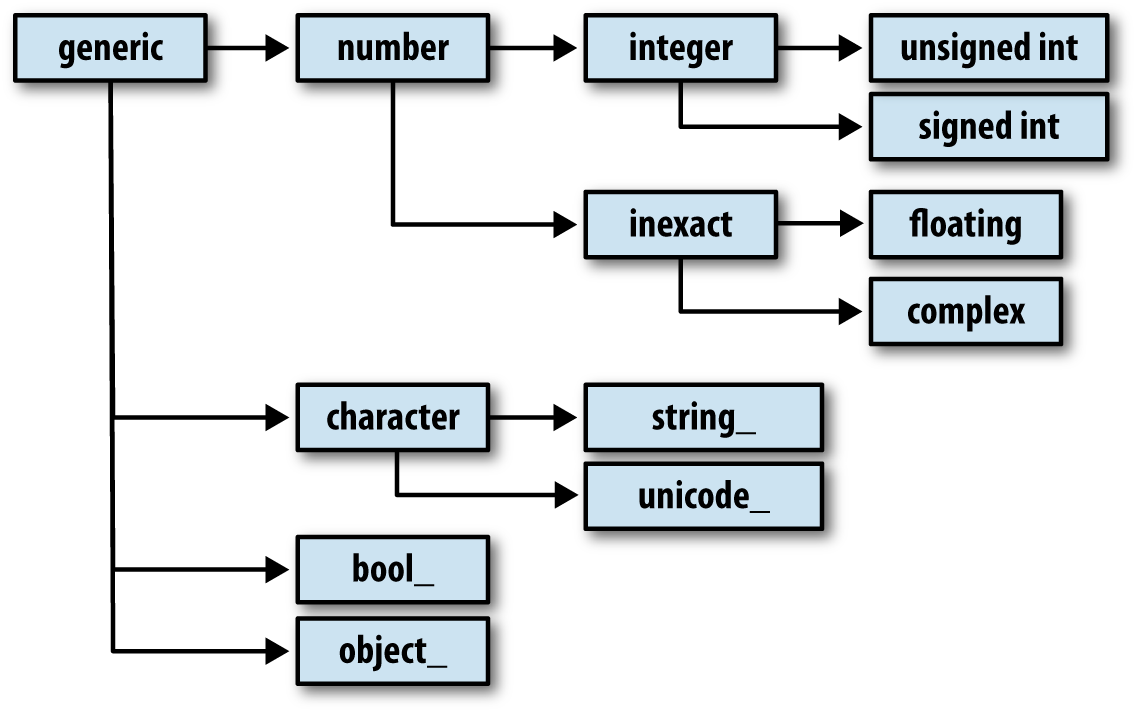

You may occasionally have code that needs to check whether an array contains

integers, floating-point numbers, strings, or Python objects. Because

there are multiple types of floating-point numbers (float16 through float128), checking that the dtype is among a

list of types would be very verbose. Fortunately, the dtypes have

superclasses such as np.integer and

np.floating, which can be used in

conjunction with the np.issubdtype

function:

In[12]:ints=np.ones(10,dtype=np.uint16)In[13]:floats=np.ones(10,dtype=np.float32)In[14]:np.issubdtype(ints.dtype,np.integer)Out[14]:TrueIn[15]:np.issubdtype(floats.dtype,np.floating)Out[15]:True

You can see all of the parent classes of a specific dtype by

calling the type’s mro

method:

In[16]:np.float64.mro()Out[16]:[numpy.float64,numpy.floating,numpy.inexact,numpy.number,numpy.generic,float,object]

Therefore, we also have:

In[17]:np.issubdtype(ints.dtype,np.number)Out[17]:True

Most NumPy users will never have to know about this, but it occasionally comes in handy. See Figure A-2 for a graph of the dtype hierarchy and parent–subclass relationships.1

Figure A-2. The NumPy dtype class hierarchy

A.2 Advanced Array Manipulation

There are many ways to work with arrays beyond fancy indexing, slicing, and boolean subsetting. While much of the heavy lifting for data analysis applications is handled by higher-level functions in pandas, you may at some point need to write a data algorithm that is not found in one of the existing libraries.

Reshaping Arrays

In many cases, you can convert an array from one shape to another without

copying any data. To do this, pass a tuple indicating the new shape to

the reshape array instance method.

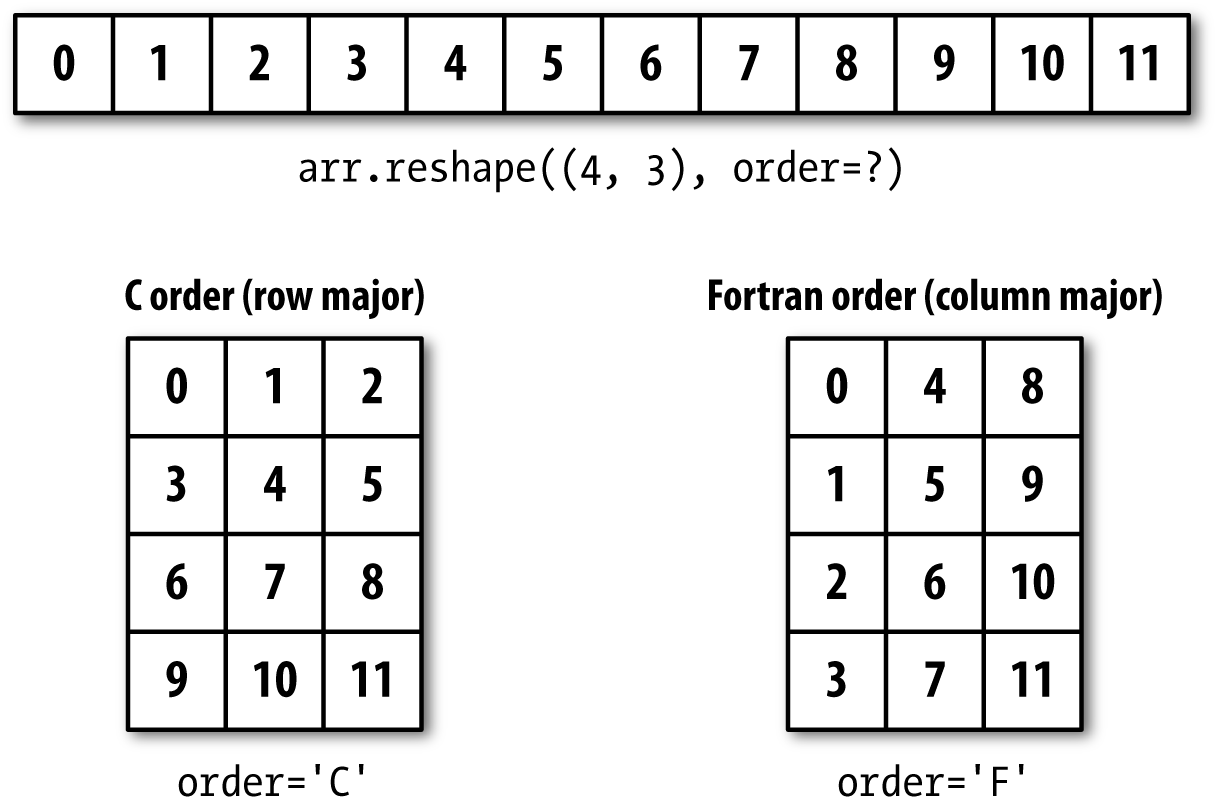

For example, suppose we had a one-dimensional array of values that we

wished to rearrange into a matrix (the result is shown in Figure A-3):

In[18]:arr=np.arange(8)In[19]:arrOut[19]:array([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7])In[20]:arr.reshape((4,2))Out[20]:array([[0,1],[2,3],[4,5],[6,7]])

Figure A-3. Reshaping in C (row major) or Fortran (column major) order

A multidimensional array can also be reshaped:

In[21]:arr.reshape((4,2)).reshape((2,4))Out[21]:array([[0,1,2,3],[4,5,6,7]])

One of the passed shape dimensions can be –1, in which case the value used for that dimension will be inferred from the data:

In[22]:arr=np.arange(15)In[23]:arr.reshape((5,-1))Out[23]:array([[0,1,2],[3,4,5],[6,7,8],[9,10,11],[12,13,14]])

Since an array’s shape

attribute is a tuple, it can be passed to reshape, too:

In[24]:other_arr=np.ones((3,5))In[25]:other_arr.shapeOut[25]:(3,5)In[26]:arr.reshape(other_arr.shape)Out[26]:array([[0,1,2,3,4],[5,6,7,8,9],[10,11,12,13,14]])

The opposite operation of reshape from one-dimensional to a higher

dimension is typically known as flattening or

raveling:

In[27]:arr=np.arange(15).reshape((5,3))In[28]:arrOut[28]:array([[0,1,2],[3,4,5],[6,7,8],[9,10,11],[12,13,14]])In[29]:arr.ravel()Out[29]:array([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14])

ravel does not produce a copy

of the underlying values if the values in the result were contiguous in the original array.

The flatten method behaves like ravel

except it always returns a copy of the data:

In[30]:arr.flatten()Out[30]:array([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14])

The data can be reshaped or raveled in different orders. This is a slightly nuanced topic for new NumPy users and is therefore the next subtopic.

C Versus Fortran Order

NumPy gives you control and flexibility over the layout of your data in memory. By default, NumPy arrays are created in row major order. Spatially this means that if you have a two-dimensional array of data, the items in each row of the array are stored in adjacent memory locations. The alternative to row major ordering is column major order, which means that values within each column of data are stored in adjacent memory locations.

For historical reasons, row and column major order are also know as C and Fortran order, respectively. In the FORTRAN 77 language, matrices are all column major.

Functions like reshape and

ravel accept an order argument indicating the order to use the

data in the array. This is usually set to 'C' or 'F'

in most cases (there are also less commonly used options 'A' and 'K'; see the NumPy documentation, and refer

back to Figure A-3 for an illustration of

these options):

In[31]:arr=np.arange(12).reshape((3,4))In[32]:arrOut[32]:array([[0,1,2,3],[4,5,6,7],[8,9,10,11]])In[33]:arr.ravel()Out[33]:array([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11])In[34]:arr.ravel('F')Out[34]:array([0,4,8,1,5,9,2,6,10,3,7,11])

Reshaping arrays with more than two dimensions can be a bit mind-bending (see Figure A-3). The key difference between C and Fortran order is the way in which the dimensions are walked:

- C/row major order

Traverse higher dimensions first (e.g., axis 1 before advancing on axis 0).

- Fortran/column major order

Traverse higher dimensions last (e.g., axis 0 before advancing on axis 1).

Concatenating and Splitting Arrays

numpy.concatenate takes a

sequence (tuple, list, etc.) of arrays and joins them

together in order along the input axis:

In[35]:arr1=np.array([[1,2,3],[4,5,6]])In[36]:arr2=np.array([[7,8,9],[10,11,12]])In[37]:np.concatenate([arr1,arr2],axis=0)Out[37]:array([[1,2,3],[4,5,6],[7,8,9],[10,11,12]])In[38]:np.concatenate([arr1,arr2],axis=1)Out[38]:array([[1,2,3,7,8,9],[4,5,6,10,11,12]])

There are some convenience functions, like vstack and

hstack, for common kinds of

concatenation. The preceding operations could have been expressed

as:

In[39]:np.vstack((arr1,arr2))Out[39]:array([[1,2,3],[4,5,6],[7,8,9],[10,11,12]])In[40]:np.hstack((arr1,arr2))Out[40]:array([[1,2,3,7,8,9],[4,5,6,10,11,12]])

split, on the other hand, slices apart an array into multiple arrays along an

axis:

In[41]:arr=np.random.randn(5,2)In[42]:arrOut[42]:array([[-0.2047,0.4789],[-0.5194,-0.5557],[1.9658,1.3934],[0.0929,0.2817],[0.769,1.2464]])In[43]:first,second,third=np.split(arr,[1,3])In[44]:firstOut[44]:array([[-0.2047,0.4789]])In[45]:secondOut[45]:array([[-0.5194,-0.5557],[1.9658,1.3934]])In[46]:thirdOut[46]:array([[0.0929,0.2817],[0.769,1.2464]])

The value [1, 3] passed to

np.split indicate the indices at which to split the

array into pieces.

See Table A-1 for a list of all

relevant concatenation and splitting functions, some of which are

provided only as a convenience of the very general-purpose concatenate.

Stacking helpers: r_ and c_

There are two special objects in the NumPy namespace, r_

and c_, that make stacking arrays

more concise:

In[47]:arr=np.arange(6)In[48]:arr1=arr.reshape((3,2))In[49]:arr2=np.random.randn(3,2)In[50]:np.r_[arr1,arr2]Out[50]:array([[0.,1.],[2.,3.],[4.,5.],[1.0072,-1.2962],[0.275,0.2289],[1.3529,0.8864]])In[51]:np.c_[np.r_[arr1,arr2],arr]Out[51]:array([[0.,1.,0.],[2.,3.,1.],[4.,5.,2.],[1.0072,-1.2962,3.],[0.275,0.2289,4.],[1.3529,0.8864,5.]])

These additionally can translate slices to arrays:

In[52]:np.c_[1:6,-10:-5]Out[52]:array([[1,-10],[2,-9],[3,-8],[4,-7],[5,-6]])

See the docstring for more on what you can do with c_ and r_.

Repeating Elements: tile and repeat

Two useful tools for repeating or replicating arrays to produce

larger arrays are the repeat and tile functions. repeat replicates each element in an array

some number of times, producing a larger array:

In[53]:arr=np.arange(3)In[54]:arrOut[54]:array([0,1,2])In[55]:arr.repeat(3)Out[55]:array([0,0,0,1,1,1,2,2,2])

Note

The need to replicate or repeat arrays can be less common with NumPy than it is with other array programming frameworks like MATLAB. One reason for this is that broadcasting often fills this need better, which is the subject of the next section.

By default, if you pass an integer, each element will be repeated that number of times. If you pass an array of integers, each element can be repeated a different number of times:

In[56]:arr.repeat([2,3,4])Out[56]:array([0,0,1,1,1,2,2,2,2])

Multidimensional arrays can have their elements repeated along a particular axis.

In[57]:arr=np.random.randn(2,2)In[58]:arrOut[58]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386]])In[59]:arr.repeat(2,axis=0)Out[59]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718],[-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386],[1.669,-0.4386]])

Note that if no axis is passed, the array will be flattened first, which is likely not what you want. Similarly, you can pass an array of integers when repeating a multidimensional array to repeat a given slice a different number of times:

In[60]:arr.repeat([2,3],axis=0)Out[60]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718],[-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386],[1.669,-0.4386],[1.669,-0.4386]])In[61]:arr.repeat([2,3],axis=1)Out[61]:array([[-2.0016,-2.0016,-0.3718,-0.3718,-0.3718],[1.669,1.669,-0.4386,-0.4386,-0.4386]])

tile, on the other hand, is a

shortcut for stacking copies of an array along an axis. Visually you can

think of it as being akin to “laying down tiles”:

In[62]:arrOut[62]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386]])In[63]:np.tile(arr,2)Out[63]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718,-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386,1.669,-0.4386]])

The second argument is the number of tiles; with a scalar, the

tiling is made row by row, rather than column by column. The second

argument to tile can be a tuple

indicating the layout of the “tiling”:

In[64]:arrOut[64]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386]])In[65]:np.tile(arr,(2,1))Out[65]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386],[-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386]])In[66]:np.tile(arr,(3,2))Out[66]:array([[-2.0016,-0.3718,-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386,1.669,-0.4386],[-2.0016,-0.3718,-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386,1.669,-0.4386],[-2.0016,-0.3718,-2.0016,-0.3718],[1.669,-0.4386,1.669,-0.4386]])

Fancy Indexing Equivalents: take and put

As you may recall from Chapter 4, one way to get and set subsets of arrays is by fancy indexing using integer arrays:

In[67]:arr=np.arange(10)*100In[68]:inds=[7,1,2,6]In[69]:arr[inds]Out[69]:array([700,100,200,600])

There are alternative ndarray methods that are useful in the special case of only making a selection on a single axis:

In[70]:arr.take(inds)Out[70]:array([700,100,200,600])In[71]:arr.put(inds,42)In[72]:arrOut[72]:array([0,42,42,300,400,500,42,42,800,900])In[73]:arr.put(inds,[40,41,42,43])In[74]:arrOut[74]:array([0,41,42,300,400,500,43,40,800,900])

To use take along other axes,

you can pass the axis keyword:

In[75]:inds=[2,0,2,1]In[76]:arr=np.random.randn(2,4)In[77]:arrOut[77]:array([[-0.5397,0.477,3.2489,-1.0212],[-0.5771,0.1241,0.3026,0.5238]])In[78]:arr.take(inds,axis=1)Out[78]:array([[3.2489,-0.5397,3.2489,0.477],[0.3026,-0.5771,0.3026,0.1241]])

put does not accept an axis argument but rather indexes into the

flattened (one-dimensional, C order) version of the array. Thus, when

you need to set elements using an index array on other axes, it is often

easiest to use fancy indexing.

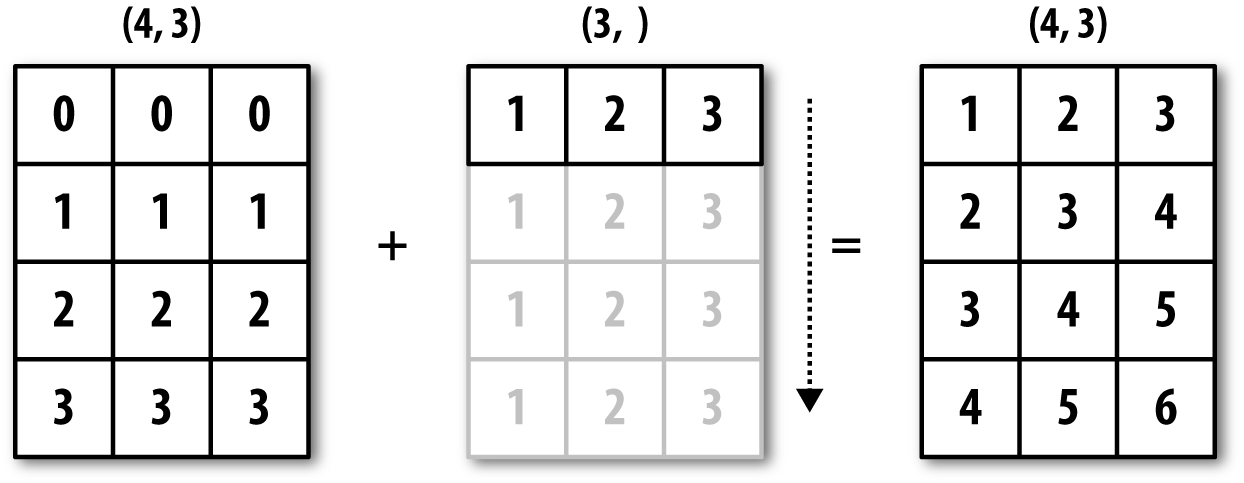

A.3 Broadcasting

Broadcasting describes how arithmetic works between arrays of different shapes. It can be a powerful feature, but one that can cause confusion, even for experienced users. The simplest example of broadcasting occurs when combining a scalar value with an array:

In[79]:arr=np.arange(5)In[80]:arrOut[80]:array([0,1,2,3,4])In[81]:arr*4Out[81]:array([0,4,8,12,16])

Here we say that the scalar value 4 has been broadcast to all of the other elements in the multiplication operation.

For example, we can demean each column of an array by subtracting the column means. In this case, it is very simple:

In[82]:arr=np.random.randn(4,3)In[83]:arr.mean(0)Out[83]:array([-0.3928,-0.3824,-0.8768])In[84]:demeaned=arr-arr.mean(0)In[85]:demeanedOut[85]:array([[0.3937,1.7263,0.1633],[-0.4384,-1.9878,-0.9839],[-0.468,0.9426,-0.3891],[0.5126,-0.6811,1.2097]])In[86]:demeaned.mean(0)Out[86]:array([-0.,0.,-0.])

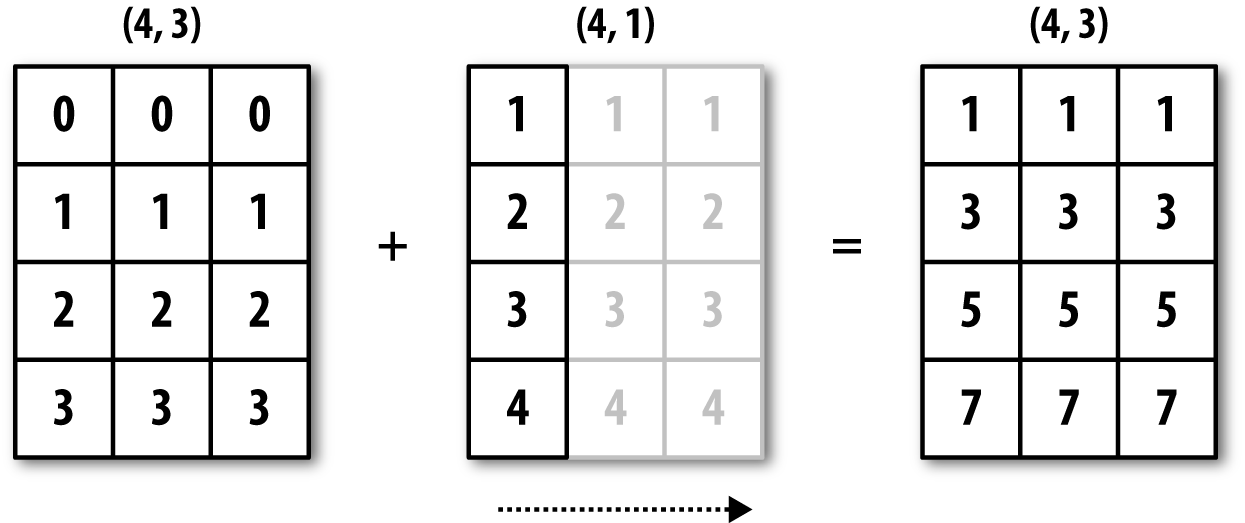

See Figure A-4 for an illustration of this operation. Demeaning the rows as a broadcast operation requires a bit more care. Fortunately, broadcasting potentially lower dimensional values across any dimension of an array (like subtracting the row means from each column of a two-dimensional array) is possible as long as you follow the rules.

This brings us to:

Figure A-4. Broadcasting over axis 0 with a 1D array

Even as an experienced NumPy user, I often find myself having to

pause and draw a diagram as I think about the broadcasting rule. Consider

the last example and suppose we wished instead to subtract the mean value

from each row. Since arr.mean(0) has

length 3, it is compatible for broadcasting across axis 0 because the

trailing dimension in arr is 3 and

therefore matches. According to the rules, to subtract over axis 1 (i.e.,

subtract the row mean from each row), the smaller array must have shape

(4, 1):

In[87]:arrOut[87]:array([[0.0009,1.3438,-0.7135],[-0.8312,-2.3702,-1.8608],[-0.8608,0.5601,-1.2659],[0.1198,-1.0635,0.3329]])In[88]:row_means=arr.mean(1)In[89]:row_means.shapeOut[89]:(4,)In[90]:row_means.reshape((4,1))Out[90]:array([[0.2104],[-1.6874],[-0.5222],[-0.2036]])In[91]:demeaned=arr-row_means.reshape((4,1))In[92]:demeaned.mean(1)Out[92]:array([0.,-0.,0.,0.])

See Figure A-5 for an illustration of this operation.

Figure A-5. Broadcasting over axis 1 of a 2D array

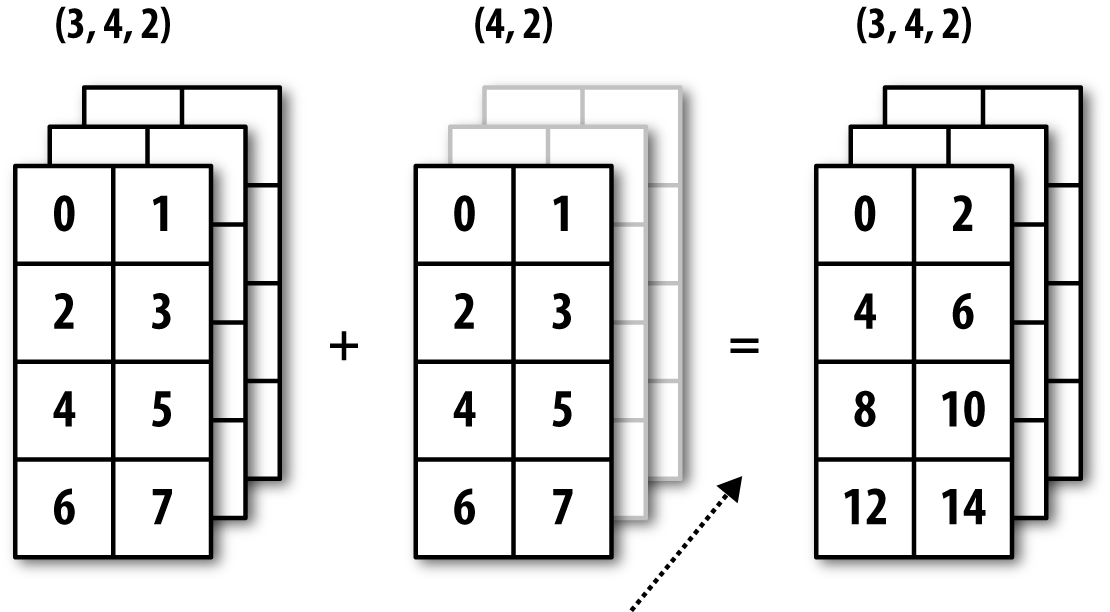

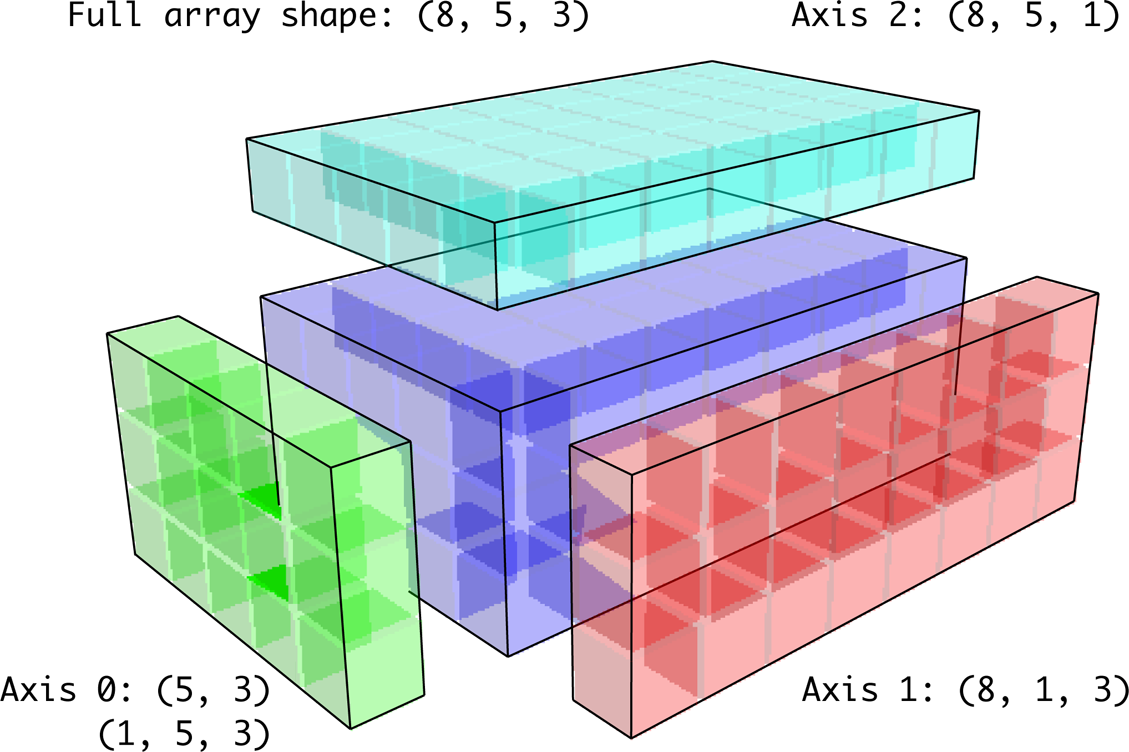

See Figure A-6 for another illustration, this time adding a two-dimensional array to a three-dimensional one across axis 0.

Figure A-6. Broadcasting over axis 0 of a 3D array

Broadcasting Over Other Axes

Broadcasting with higher dimensional arrays can seem even more mind-bending, but it is really a matter of following the rules. If you don’t, you’ll get an error like this:

In[93]:arr-arr.mean(1)---------------------------------------------------------------------------ValueErrorTraceback(mostrecentcalllast)<ipython-input-93-8b8ada26fac0>in<module>()---->1arr-arr.mean(1)ValueError:operandscouldnotbebroadcasttogetherwithshapes(4,3)(4,)

It’s quite common to want to perform an arithmetic operation with

a lower dimensional array across axes other than axis 0. According to

the broadcasting rule, the “broadcast dimensions” must be 1 in the

smaller array. In the example of row demeaning shown here, this meant

reshaping the row means to be shape (4,

1) instead of (4,):

In[94]:arr-arr.mean(1).reshape((4,1))Out[94]:array([[-0.2095,1.1334,-0.9239],[0.8562,-0.6828,-0.1734],[-0.3386,1.0823,-0.7438],[0.3234,-0.8599,0.5365]])

In the three-dimensional case, broadcasting over any of the three dimensions is only a matter of reshaping the data to be shape-compatible. Figure A-7 nicely visualizes the shapes required to broadcast over each axis of a three-dimensional array.

A common problem, therefore, is needing to add a new axis with

length 1 specifically for broadcasting purposes. Using reshape is one option, but inserting an axis

requires constructing a tuple indicating the new shape. This can often

be a tedious exercise. Thus, NumPy arrays offer a special syntax for

inserting new axes by indexing. We use the special np.newaxis

attribute along with “full” slices to insert the new axis:

In[95]:arr=np.zeros((4,4))In[96]:arr_3d=arr[:,np.newaxis,:]In[97]:arr_3d.shapeOut[97]:(4,1,4)In[98]:arr_1d=np.random.normal(size=3)In[99]:arr_1d[:,np.newaxis]Out[99]:array([[-2.3594],[-0.1995],[-1.542]])In[100]:arr_1d[np.newaxis,:]Out[100]:array([[-2.3594,-0.1995,-1.542]])

Figure A-7. Compatible 2D array shapes for broadcasting over a 3D array

Thus, if we had a three-dimensional array and wanted to demean axis 2, say, we would need to write:

In[101]:arr=np.random.randn(3,4,5)In[102]:depth_means=arr.mean(2)In[103]:depth_meansOut[103]:array([[-0.4735,0.3971,-0.0228,0.2001],[-0.3521,-0.281,-0.071,-0.1586],[0.6245,0.6047,0.4396,-0.2846]])In[104]:depth_means.shapeOut[104]:(3,4)In[105]:demeaned=arr-depth_means[:,:,np.newaxis]In[106]:demeaned.mean(2)Out[106]:array([[0.,0.,-0.,-0.],[0.,0.,-0.,0.],[0.,0.,-0.,-0.]])

You might be wondering if there’s a way to generalize demeaning over an axis without sacrificing performance. There is, but it requires some indexing gymnastics:

defdemean_axis(arr,axis=0):means=arr.mean(axis)# This generalizes things like [:, :, np.newaxis] to N dimensionsindexer=[slice(None)]*arr.ndimindexer[axis]=np.newaxisreturnarr-means[indexer]

Setting Array Values by Broadcasting

The same broadcasting rule governing arithmetic operations also applies to setting values via array indexing. In a simple case, we can do things like:

In[107]:arr=np.zeros((4,3))In[108]:arr[:]=5In[109]:arrOut[109]:array([[5.,5.,5.],[5.,5.,5.],[5.,5.,5.],[5.,5.,5.]])

However, if we had a one-dimensional array of values we wanted to set into the columns of the array, we can do that as long as the shape is compatible:

In[110]:col=np.array([1.28,-0.42,0.44,1.6])In[111]:arr[:]=col[:,np.newaxis]In[112]:arrOut[112]:array([[1.28,1.28,1.28],[-0.42,-0.42,-0.42],[0.44,0.44,0.44],[1.6,1.6,1.6]])In[113]:arr[:2]=[[-1.37],[0.509]]In[114]:arrOut[114]:array([[-1.37,-1.37,-1.37],[0.509,0.509,0.509],[0.44,0.44,0.44],[1.6,1.6,1.6]])

A.4 Advanced ufunc Usage

While many NumPy users will only make use of the fast element-wise operations provided by the universal functions, there are a number of additional features that occasionally can help you write more concise code without loops.

ufunc Instance Methods

Each of NumPy’s binary ufuncs has special methods for performing certain kinds of special vectorized operations. These are summarized in Table A-2, but I’ll give a few concrete examples to illustrate how they work.

reduce takes a single array and aggregates its values, optionally along

an axis, by performing a sequence of binary operations. For example, an

alternative way to sum elements in an array is to use np.add.reduce:

In[115]:arr=np.arange(10)In[116]:np.add.reduce(arr)Out[116]:45In[117]:arr.sum()Out[117]:45

The starting value (0 for add)

depends on the ufunc. If an axis is passed, the reduction is performed

along that axis. This allows you to answer certain kinds of questions in

a concise way. As a less trivial example, we can use np.logical_and to check whether the values in each row of an array are

sorted:

In[118]:np.random.seed(12346)# for reproducibilityIn[119]:arr=np.random.randn(5,5)In[120]:arr[::2].sort(1)# sort a few rowsIn[121]:arr[:,:-1]<arr[:,1:]Out[121]:array([[True,True,True,True],[False,True,False,False],[True,True,True,True],[True,False,True,True],[True,True,True,True]],dtype=bool)In[122]:np.logical_and.reduce(arr[:,:-1]<arr[:,1:],axis=1)Out[122]:array([True,False,True,False,True],dtype=bool)

Note that logical_and.reduce is

equivalent to the all

method.

accumulate is related to reduce like

cumsum is related to sum. It produces an array of the same size

with the intermediate “accumulated” values:

In[123]:arr=np.arange(15).reshape((3,5))In[124]:np.add.accumulate(arr,axis=1)Out[124]:array([[0,1,3,6,10],[5,11,18,26,35],[10,21,33,46,60]])

outer performs a pairwise

cross-product between two arrays:

In[125]:arr=np.arange(3).repeat([1,2,2])In[126]:arrOut[126]:array([0,1,1,2,2])In[127]:np.multiply.outer(arr,np.arange(5))Out[127]:array([[0,0,0,0,0],[0,1,2,3,4],[0,1,2,3,4],[0,2,4,6,8],[0,2,4,6,8]])

The output of outer will have a

dimension that is the sum of the dimensions of the inputs:

In[128]:x,y=np.random.randn(3,4),np.random.randn(5)In[129]:result=np.subtract.outer(x,y)In[130]:result.shapeOut[130]:(3,4,5)

The last method, reduceat,

performs a “local reduce,” in essence an array

groupby operation in which slices of the array are

aggregated together. It accepts a sequence of “bin edges” that indicate

how to split and aggregate the values:

In[131]:arr=np.arange(10)In[132]:np.add.reduceat(arr,[0,5,8])Out[132]:array([10,18,17])

The results are the reductions (here, sums) performed over

arr[0:5], arr[5:8], and arr[8:]. As with the other methods, you can pass

an axis argument:

In[133]:arr=np.multiply.outer(np.arange(4),np.arange(5))In[134]:arrOut[134]:array([[0,0,0,0,0],[0,1,2,3,4],[0,2,4,6,8],[0,3,6,9,12]])In[135]:np.add.reduceat(arr,[0,2,4],axis=1)Out[135]:array([[0,0,0],[1,5,4],[2,10,8],[3,15,12]])

See Table A-2 for a partial listing of ufunc methods.

Writing New ufuncs in Python

There are a number of facilities for creating your own NumPy ufuncs. The most general is to use the NumPy C API, but that is beyond the scope of this book. In this section, we will look at pure Python ufuncs.

numpy.frompyfunc accepts

a Python function along with a specification for the

number of inputs and outputs. For example, a simple function that adds

element-wise would be specified as:

In[136]:defadd_elements(x,y):.....:returnx+yIn[137]:add_them=np.frompyfunc(add_elements,2,1)In[138]:add_them(np.arange(8),np.arange(8))Out[138]:array([0,2,4,6,8,10,12,14],dtype=object)

Functions created using frompyfunc always return arrays of Python

objects, which can be inconvenient. Fortunately, there is an alternative

(but slightly less featureful) function, numpy.vectorize, that allows you to specify the output type:

In[139]:add_them=np.vectorize(add_elements,otypes=[np.float64])In[140]:add_them(np.arange(8),np.arange(8))Out[140]:array([0.,2.,4.,6.,8.,10.,12.,14.])

These functions provide a way to create ufunc-like functions, but they are very slow because they require a Python function call to compute each element, which is a lot slower than NumPy’s C-based ufunc loops:

In[141]:arr=np.random.randn(10000)In[142]:%timeitadd_them(arr,arr)3.54ms+-178usperloop(mean+-std.dev.of7runs,100loopseach)In[143]:%timeitnp.add(arr,arr)6.76us+-370nsperloop(mean+-std.dev.of7runs,100000loopseach)

Later in this chapter we’ll show how to create fast ufuncs in Python using the Numba project.

A.5 Structured and Record Arrays

You may have noticed up until now that ndarray is a homogeneous data container; that is, it represents a block of memory in which each element takes up the same number of bytes, determined by the dtype. On the surface, this would appear to not allow you to represent heterogeneous or tabular-like data. A structured array is an ndarray in which each element can be thought of as representing a struct in C (hence the “structured” name) or a row in a SQL table with multiple named fields:

In[144]:dtype=[('x',np.float64),('y',np.int32)]In[145]:sarr=np.array([(1.5,6),(np.pi,-2)],dtype=dtype)In[146]:sarrOut[146]:array([(1.5,6),(3.1416,-2)],dtype=[('x','<f8'),('y','<i4')])

There are several ways to specify a structured dtype (see the online

NumPy documentation). One typical way is as a list of tuples with (field_name, field_data_type). Now, the elements

of the array are tuple-like objects whose elements can be accessed like a

dictionary:

In[147]:sarr[0]Out[147]:(1.5,6)In[148]:sarr[0]['y']Out[148]:6

The field names are stored in the dtype.names

attribute. When you access a field on the structured array, a strided view

on the data is returned, thus copying nothing:

In[149]:sarr['x']Out[149]:array([1.5,3.1416])

Nested dtypes and Multidimensional Fields

When specifying a structured dtype, you can additionally pass a shape (as an int or tuple):

In[150]:dtype=[('x',np.int64,3),('y',np.int32)]In[151]:arr=np.zeros(4,dtype=dtype)In[152]:arrOut[152]:array([([0,0,0],0),([0,0,0],0),([0,0,0],0),([0,0,0],0)],dtype=[('x','<i8',(3,)),('y','<i4')])

In this case, the x field now

refers to an array of length 3 for each record:

In[153]:arr[0]['x']Out[153]:array([0,0,0])

Conveniently, accessing arr['x'] then returns a two-dimensional array

instead of a one-dimensional array as in prior examples:

In[154]:arr['x']Out[154]:array([[0,0,0],[0,0,0],[0,0,0],[0,0,0]])

This enables you to express more complicated, nested structures as a single block of memory in an array. You can also nest dtypes to make more complex structures. Here is an example:

In[155]:dtype=[('x',[('a','f8'),('b','f4')]),('y',np.int32)]In[156]:data=np.array([((1,2),5),((3,4),6)],dtype=dtype)In[157]:data['x']Out[157]:array([(1.,2.),(3.,4.)],dtype=[('a','<f8'),('b','<f4')])In[158]:data['y']Out[158]:array([5,6],dtype=int32)In[159]:data['x']['a']Out[159]:array([1.,3.])

pandas DataFrame does not support this feature directly, though it is similar to hierarchical indexing.

Why Use Structured Arrays?

Compared with, say, a pandas DataFrame, NumPy structured arrays are a comparatively low-level tool. They provide a means to interpreting a block of memory as a tabular structure with arbitrarily complex nested columns. Since each element in the array is represented in memory as a fixed number of bytes, structured arrays provide a very fast and efficient way of writing data to and from disk (including memory maps), transporting it over the network, and other such uses.

As another common use for structured arrays, writing data files as

fixed-length record byte streams is a common way to serialize data in C

and C++ code, which is commonly found in legacy systems in industry. As

long as the format of the file is known (the size of each record and the

order, byte size, and data type of each element), the data can be read

into memory with np.fromfile.

Specialized uses like this are beyond the scope of this book, but it’s

worth knowing that such things are possible.

A.6 More About Sorting

Like Python’s built-in list, the ndarray sort instance

method is an in-place sort, meaning that the

array contents are rearranged without producing a new array:

In[160]:arr=np.random.randn(6)In[161]:arr.sort()In[162]:arrOut[162]:array([-1.082,0.3759,0.8014,1.1397,1.2888,1.8413])

When sorting arrays in-place, remember that if the array is a view on a different ndarray, the original array will be modified:

In[163]:arr=np.random.randn(3,5)In[164]:arrOut[164]:array([[-0.3318,-1.4711,0.8705,-0.0847,-1.1329],[-1.0111,-0.3436,2.1714,0.1234,-0.0189],[0.1773,0.7424,0.8548,1.038,-0.329]])In[165]:arr[:,0].sort()# Sort first column values in-placeIn[166]:arrOut[166]:array([[-1.0111,-1.4711,0.8705,-0.0847,-1.1329],[-0.3318,-0.3436,2.1714,0.1234,-0.0189],[0.1773,0.7424,0.8548,1.038,-0.329]])

On the other hand, numpy.sort

creates a new, sorted copy of an array. Otherwise, it accepts the same

arguments (such as kind) as ndarray.sort:

In[167]:arr=np.random.randn(5)In[168]:arrOut[168]:array([-1.1181,-0.2415,-2.0051,0.7379,-1.0614])In[169]:np.sort(arr)Out[169]:array([-2.0051,-1.1181,-1.0614,-0.2415,0.7379])In[170]:arrOut[170]:array([-1.1181,-0.2415,-2.0051,0.7379,-1.0614])

All of these sort methods take an axis argument for sorting the sections of data along the passed axis independently:

In[171]:arr=np.random.randn(3,5)In[172]:arrOut[172]:array([[0.5955,-0.2682,1.3389,-0.1872,0.9111],[-0.3215,1.0054,-0.5168,1.1925,-0.1989],[0.3969,-1.7638,0.6071,-0.2222,-0.2171]])In[173]:arr.sort(axis=1)In[174]:arrOut[174]:array([[-0.2682,-0.1872,0.5955,0.9111,1.3389],[-0.5168,-0.3215,-0.1989,1.0054,1.1925],[-1.7638,-0.2222,-0.2171,0.3969,0.6071]])

You may notice that none of the sort methods have an option to sort

in descending order. This is a problem in practice because array slicing

produces views, thus not producing a copy or requiring any computational

work. Many Python users are familiar with the “trick” that for a list

values, values[::-1] returns a list in reverse order.

The same is true for ndarrays:

In[175]:arr[:,::-1]Out[175]:array([[1.3389,0.9111,0.5955,-0.1872,-0.2682],[1.1925,1.0054,-0.1989,-0.3215,-0.5168],[0.6071,0.3969,-0.2171,-0.2222,-1.7638]])

Indirect Sorts: argsort and lexsort

In data analysis you may need to reorder datasets by one or more keys. For example, a table

of data about some students might need to be sorted by last name, then by

first name. This is an example of an indirect sort,

and if you’ve read the pandas-related chapters you have already seen

many higher-level examples. Given a key or keys (an array of values or

multiple arrays of values), you wish to obtain an array of integer

indices (I refer to them colloquially as

indexers) that tells you how to reorder the data to

be in sorted order. Two methods for this are argsort and numpy.lexsort. As an example:

In[176]:values=np.array([5,0,1,3,2])In[177]:indexer=values.argsort()In[178]:indexerOut[178]:array([1,2,4,3,0])In[179]:values[indexer]Out[179]:array([0,1,2,3,5])

As a more complicated example, this code reorders a two-dimensional array by its first row:

In[180]:arr=np.random.randn(3,5)In[181]:arr[0]=valuesIn[182]:arrOut[182]:array([[5.,0.,1.,3.,2.],[-0.3636,-0.1378,2.1777,-0.4728,0.8356],[-0.2089,0.2316,0.728,-1.3918,1.9956]])In[183]:arr[:,arr[0].argsort()]Out[183]:array([[0.,1.,2.,3.,5.],[-0.1378,2.1777,0.8356,-0.4728,-0.3636],[0.2316,0.728,1.9956,-1.3918,-0.2089]])

lexsort is similar to argsort, but it performs an indirect

lexicographical sort on multiple key arrays.

Suppose we wanted to sort some data identified by first and last

names:

In[184]:first_name=np.array(['Bob','Jane','Steve','Bill','Barbara'])In[185]:last_name=np.array(['Jones','Arnold','Arnold','Jones','Walters'])In[186]:sorter=np.lexsort((first_name,last_name))In[187]:sorterOut[187]:array([1,2,3,0,4])In[188]:zip(last_name[sorter],first_name[sorter])Out[188]:<zipat0x7efeec8e38c8>

lexsort can be a bit confusing

the first time you use it because the order in which the keys are used

to order the data starts with the last array

passed. Here, last_name was used

before first_name.

Alternative Sort Algorithms

A stable sorting algorithm preserves the relative position of equal elements. This can be especially important in indirect sorts where the relative ordering is meaningful:

In[189]:values=np.array(['2:first','2:second','1:first','1:second',.....:'1:third'])In[190]:key=np.array([2,2,1,1,1])In[191]:indexer=key.argsort(kind='mergesort')In[192]:indexerOut[192]:array([2,3,4,0,1])In[193]:values.take(indexer)Out[193]:array(['1:first','1:second','1:third','2:first','2:second'],dtype='<U8')

The only stable sort available is mergesort, which has guaranteed

O(n log n) performance (for complexity buffs), but

its performance is on average worse than the default quicksort method. See Table A-3 for a summary of available methods

and their relative performance (and performance guarantees). This is not

something that most users will ever have to think about, but it’s useful to know that it’s there.

| Kind | Speed | Stable | Work space | Worst case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

'quicksort' | 1 | No | 0 | O(n^2) |

'mergesort' | 2 | Yes | n / 2 | O(n log n) |

'heapsort' | 3 | No | 0 | O(n log n) |

Partially Sorting Arrays

One of the goals of sorting can be to determine the largest or smallest elements in an

array. NumPy has optimized methods, numpy.partition

and np.argpartition, for partitioning an array around the k-th

smallest element:

In[194]:np.random.seed(12345)In[195]:arr=np.random.randn(20)In[196]:arrOut[196]:array([-0.2047,0.4789,-0.5194,-0.5557,1.9658,1.3934,0.0929,0.2817,0.769,1.2464,1.0072,-1.2962,0.275,0.2289,1.3529,0.8864,-2.0016,-0.3718,1.669,-0.4386])In[197]:np.partition(arr,3)Out[197]:array([-2.0016,-1.2962,-0.5557,-0.5194,-0.3718,-0.4386,-0.2047,0.2817,0.769,0.4789,1.0072,0.0929,0.275,0.2289,1.3529,0.8864,1.3934,1.9658,1.669,1.2464])

After you call partition(arr, 3), the first

three elements in the result are the smallest three values in no

particular order. numpy.argpartition, similar

to numpy.argsort, returns the indices

that rearrange the data into the equivalent order:

In[198]:indices=np.argpartition(arr,3)In[199]:indicesOut[199]:array([16,11,3,2,17,19,0,7,8,1,10,6,12,13,14,15,5,4,18,9])In[200]:arr.take(indices)Out[200]:array([-2.0016,-1.2962,-0.5557,-0.5194,-0.3718,-0.4386,-0.2047,0.2817,0.769,0.4789,1.0072,0.0929,0.275,0.2289,1.3529,0.8864,1.3934,1.9658,1.669,1.2464])

numpy.searchsorted: Finding Elements in a Sorted Array

searchsorted is an array

method that performs a binary search on a sorted array,

returning the location in the array where the value would need to be

inserted to maintain sortedness:

In[201]:arr=np.array([0,1,7,12,15])In[202]:arr.searchsorted(9)Out[202]:3

You can also pass an array of values to get an array of indices back:

In[203]:arr.searchsorted([0,8,11,16])Out[203]:array([0,3,3,5])

You might have noticed that searchsorted returned 0 for the 0

element. This is because the default behavior is to return the index at

the left side of a group of equal values:

In[204]:arr=np.array([0,0,0,1,1,1,1])In[205]:arr.searchsorted([0,1])Out[205]:array([0,3])In[206]:arr.searchsorted([0,1],side='right')Out[206]:array([3,7])

As another application of searchsorted, suppose we had an array of

values between 0 and 10,000, and a separate array of “bucket edges” that

we wanted to use to bin the data:

In[207]:data=np.floor(np.random.uniform(0,10000,size=50))In[208]:bins=np.array([0,100,1000,5000,10000])In[209]:dataOut[209]:array([9940.,6768.,7908.,1709.,268.,8003.,9037.,246.,4917.,5262.,5963.,519.,8950.,7282.,8183.,5002.,8101.,959.,2189.,2587.,4681.,4593.,7095.,1780.,5314.,1677.,7688.,9281.,6094.,1501.,4896.,3773.,8486.,9110.,3838.,3154.,5683.,1878.,1258.,6875.,7996.,5735.,9732.,6340.,8884.,4954.,3516.,7142.,5039.,2256.])

To then get a labeling of which interval each data point belongs

to (where 1 would mean the bucket [0,

100)), we can simply use searchsorted:

In[210]:labels=bins.searchsorted(data)In[211]:labelsOut[211]:array([4,4,4,3,2,4,4,2,3,4,4,2,4,4,4,4,4,2,3,3,3,3,4,3,4,3,4,4,4,3,3,3,4,4,3,3,4,3,3,4,4,4,4,4,4,3,3,4,4,3])

This, combined with pandas’s groupby, can be used to bin data:

In[212]:pd.Series(data).groupby(labels).mean()Out[212]:2498.00000033064.27777847389.035714dtype:float64

A.7 Writing Fast NumPy Functions with Numba

Numba is an open source project that creates fast functions for NumPy-like data using CPUs, GPUs, or other hardware. It uses the LLVM Project to translate Python code into compiled machine code.

To introduce Numba, let’s consider a pure Python function that

computes the expression (x - y).mean() using a

for loop:

importnumpyasnpdefmean_distance(x,y):nx=len(x)result=0.0count=0foriinrange(nx):result+=x[i]-y[i]count+=1returnresult/count

This function is very slow:

In[209]:x=np.random.randn(10000000)In[210]:y=np.random.randn(10000000)In[211]:%timeitmean_distance(x,y)1loop,bestof3:2sperloopIn[212]:%timeit(x-y).mean()100loops,bestof3:14.7msperloop

The NumPy version is over 100 times faster. We can turn this

function into a compiled Numba function using the numba.jit function:

In[213]:importnumbaasnbIn[214]:numba_mean_distance=nb.jit(mean_distance)

We could also have written this as a decorator:

@nb.jitdefmean_distance(x,y):nx=len(x)result=0.0count=0foriinrange(nx):result+=x[i]-y[i]count+=1returnresult/count

The resulting function is actually faster than the vectorized NumPy version:

In[215]:%timeitnumba_mean_distance(x,y)100loops,bestof3:10.3msperloop

Numba cannot compile arbitrary Python code, but it supports a significant subset of pure Python that is most useful for writing numerical algorithms.

Numba is a deep library, supporting different kinds of hardware,

modes of compilation, and user extensions. It is also able to compile a

substantial subset of the NumPy Python API without explicit

for loops. Numba is able to recognize constructs that

can be compiled to machine code, while substituting calls to the CPython

API for functions that it does not know how to compile. Numba’s

jit function has an option, nopython=True, which

restricts allowed code to Python code that can be compiled to LLVM without

any Python C API calls. jit(nopython=True) has a

shorter alias numba.njit.

In the previous example, we could have written:

fromnumbaimportfloat64,njit@njit(float64(float64[:],float64[:]))defmean_distance(x,y):return(x-y).mean()

I encourage you to learn more by reading the online documentation for Numba. The next section shows an example of creating custom NumPy ufunc objects.

Creating Custom numpy.ufunc Objects with Numba

The numba.vectorize function creates compiled NumPy ufuncs, which behave like built-in

ufuncs. Let’s consider a Python implementation of

numpy.add:

fromnumbaimportvectorize@vectorizedefnb_add(x,y):returnx+y

In[13]:x=np.arange(10)In[14]:nb_add(x,x)Out[14]:array([0.,2.,4.,6.,8.,10.,12.,14.,16.,18.])In[15]:nb_add.accumulate(x,0)Out[15]:array([0.,1.,3.,6.,10.,15.,21.,28.,36.,45.])

A.8 Advanced Array Input and Output

In Chapter 4, we became acquainted with np.save and np.load for storing arrays in binary format on

disk. There are a number of additional options to consider for more

sophisticated use. In particular, memory maps have the additional benefit

of enabling you to work with datasets that do not fit into RAM.

Memory-Mapped Files

A memory-mapped file is a method for interacting with binary data on disk as

though it is stored in an in-memory array. NumPy implements a memmap object that is ndarray-like, enabling small segments of a large

file to be read and written without reading the whole array into memory.

Additionally, a memmap has the same methods as an

in-memory array and thus can be substituted into many algorithms where

an ndarray would be expected.

To create a new memory map, use the function np.memmap and pass a file path, dtype, shape,

and file mode:

In[214]:mmap=np.memmap('mymmap',dtype='float64',mode='w+',.....:shape=(10000,10000))In[215]:mmapOut[215]:memmap([[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],...,[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.]])

Slicing a memmap returns views on the data on

disk:

In[216]:section=mmap[:5]

If you assign data to these, it will be buffered in memory (like a

Python file object), but you can write it to disk by calling flush:

In[217]:section[:]=np.random.randn(5,10000)In[218]:mmap.flush()In[219]:mmapOut[219]:memmap([[0.7584,-0.6605,0.8626,...,0.6046,-0.6212,2.0542],[-1.2113,-1.0375,0.7093,...,-1.4117,-0.1719,-0.8957],[-0.1419,-0.3375,0.4329,...,1.2914,-0.752,-0.44],...,[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.]])In[220]:delmmap

Whenever a memory map falls out of scope and is garbage-collected, any changes will be flushed to disk also. When opening an existing memory map, you still have to specify the dtype and shape, as the file is only a block of binary data with no metadata on disk:

In[221]:mmap=np.memmap('mymmap',dtype='float64',shape=(10000,10000))In[222]:mmapOut[222]:memmap([[0.7584,-0.6605,0.8626,...,0.6046,-0.6212,2.0542],[-1.2113,-1.0375,0.7093,...,-1.4117,-0.1719,-0.8957],[-0.1419,-0.3375,0.4329,...,1.2914,-0.752,-0.44],...,[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.],[0.,0.,0.,...,0.,0.,0.]])

Memory maps also work with structured or nested dtypes as described in a previous section.

HDF5 and Other Array Storage Options

PyTables and h5py are two Python projects providing NumPy-friendly interfaces for storing array data in the efficient and compressible HDF5 format (HDF stands for hierarchical data format). You can safely store hundreds of gigabytes or even terabytes of data in HDF5 format. To learn more about using HDF5 with Python, I recommend reading the pandas online documentation.

A.9 Performance Tips

Getting good performance out of code utilizing NumPy is often straightforward, as array operations typically replace otherwise comparatively extremely slow pure Python loops. The following list briefly summarizes some things to keep in mind:

Convert Python loops and conditional logic to array operations and boolean array operations

Use broadcasting whenever possible

Use arrays views (slicing) to avoid copying data

Utilize ufuncs and ufunc methods

If you can’t get the performance you require after exhausting the capabilities provided by NumPy alone, consider writing code in C, Fortran, or Cython. I use Cython frequently in my own work as an easy way to get C-like performance with minimal development.

The Importance of Contiguous Memory

While the full extent of this topic is a bit outside the scope of this book, in some applications the memory layout of an array can significantly affect the speed of computations. This is based partly on performance differences having to do with the cache hierarchy of the CPU; operations accessing contiguous blocks of memory (e.g., summing the rows of a C order array) will generally be the fastest because the memory subsystem will buffer the appropriate blocks of memory into the ultrafast L1 or L2 CPU cache. Also, certain code paths inside NumPy’s C codebase have been optimized for the contiguous case in which generic strided memory access can be avoided.

To say that an array’s memory layout is

contiguous means that the elements are stored in

memory in the order that they appear in the array with respect to

Fortran (column major) or C (row major) ordering. By

default, NumPy arrays are created as C-contiguous

or just simply contiguous. A column major array, such as the transpose

of a C-contiguous array, is thus said to be Fortran-contiguous. These

properties can be explicitly checked via the flags attribute on the ndarray:

In[225]:arr_c=np.ones((1000,1000),order='C')In[226]:arr_f=np.ones((1000,1000),order='F')In[227]:arr_c.flagsOut[227]:C_CONTIGUOUS:TrueF_CONTIGUOUS:FalseOWNDATA:TrueWRITEABLE:TrueALIGNED:TrueUPDATEIFCOPY:FalseIn[228]:arr_f.flagsOut[228]:C_CONTIGUOUS:FalseF_CONTIGUOUS:TrueOWNDATA:TrueWRITEABLE:TrueALIGNED:TrueUPDATEIFCOPY:FalseIn[229]:arr_f.flags.f_contiguousOut[229]:True

In this example, summing the rows of these arrays should, in

theory, be faster for arr_c than

arr_f since the rows are contiguous

in memory. Here I check for sure using %timeit in

IPython:

In[230]:%timeitarr_c.sum(1)842us+-40.3usperloop(mean+-std.dev.of7runs,1000loopseach)In[231]:%timeitarr_f.sum(1)879us+-23.6usperloop(mean+-std.dev.of7runs,1000loopseach)

When you’re looking to squeeze more performance out of NumPy, this is

often a place to invest some effort. If you have an array that does not

have the desired memory order, you can use copy and pass either 'C' or 'F':

In[232]:arr_f.copy('C').flagsOut[232]:C_CONTIGUOUS:TrueF_CONTIGUOUS:FalseOWNDATA:TrueWRITEABLE:TrueALIGNED:TrueUPDATEIFCOPY:False

When constructing a view on an array, keep in mind that the result is not guaranteed to be contiguous:

In[233]:arr_c[:50].flags.contiguousOut[233]:TrueIn[234]:arr_c[:,:50].flagsOut[234]:C_CONTIGUOUS:FalseF_CONTIGUOUS:FalseOWNDATA:FalseWRITEABLE:TrueALIGNED:TrueUPDATEIFCOPY:False

1 Some of the dtypes have trailing underscores in their names. These are there to avoid variable name conflicts between the NumPy-specific types and the Python built-in ones.