Chapter 16. Tracking Current Security Threats

Knowledge is an exceptionally powerful tool in the right hands. In order to stay on top of the security issues that could affect your application, you need to track the current security threats. However, if you pay any attention at all to the news media, you know that trying to track every potential security threat could become a full-time job. If you add in the stories from the trade press as well, then you really do have a full-time job and possibly a task that would require a team to manage the information flow. Clearly, you need some method of discerning which threats really do require your attention, or you could end up spending too much time tracking information and not enough time actually avoiding the threats.

Once you decide that the security threat is real, you need to decide what sort of action to take. Remember from Chapter 15 that the only report you really need is the one that provides for some type of action. You can say the same thing about security threat reports. The security threat discussion you need to investigate fully is the one that requires some sort of action on your part. Everything else is excess information that wastes your time. Of course, you need to decide between an update or an upgrade of your application when the situation requires. The point is that you need to be thinking about how to react to security threats and then take the required actions when necessary (or simply put the report in the circular file where it belongs).

This chapter isn’t solely about researching security threats—it’s about acting on information about security threats. In order to keep your application and its associated data safe, you need to know about the security threats and then act upon the information you receive. The worst thing you can do is arrive at a crisis situation unprepared, without a plan, and lacking the information you need to deal with the threat.

Developing Sources for Security Threat Information

Because there is so much security information so widely available, you need to cultivate sources of security threat information that provide the material in a form you need and proves succinct enough to discover threats without wasting a lot of time. You want input from security professionals because the professionals have the time and resources to research the information fully. However, you need information from sources managed by professionals with a perspective similar to your own and not subject to the usual amount of hype, hysteria, and helplessness. The following sections review the most commonly used sources of security threat information and help you understand the role that each source has to play in helping make your application secure.

Checking Security Sites

Security sites tend to provide you with detailed information for a wide range of security threats. The security site may not discuss every current threat, but you can be sure of finding most of the threats that are currently active (and probably a history of all of the threats that security professionals have destroyed in the past). In fact, the sheer weight of all that information makes security sites a bad choice for your first visit. What you really want to do is create a list of threats to research and then visit the security sites to look for those particular threats.

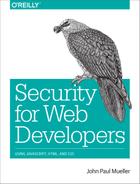

Not all security sites are created equal—a fact that is lost on many people who cruise the Internet looking for security information. In fact, security sites come in four different forms (summarized in Figure 16-1), each of which has its own advantages and disadvantages:

- Organization-based sites

- Organization-based sites often provide the most concentrated information in a particular area, but lack the breadth of information that other kinds of sites support. For example, the SANS Institute provides you with phenomenal research sources. It also sponsors various kinds of training events. This particular organization (like many others) is vendor supported, but at least you don’t get a single vendor’s perspective of how you should work through security issues.

- Government-supported sites

- These sites are obviously biased toward the needs of the government that sponsors them, but they’re mostly unbiased in the kinds of information they provide. These sites are good places to locate information about current threats of an international nature. Sites such as the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) and National Vulnerability Database provide you with an abundance of useful tips and publications that you can obtain without cost.

- Community-supported sites

- Of the security sites you can visit, community-supported sites can prove the most interesting. They often offer insights you won’t find anywhere else. Like every other site you visit, they do have an agenda of some sort and this agenda biases the information you receive, but the bias usually isn’t strong enough to affect the quality of the information you receive. Sites such as Vmyths can help you avoid the hysteria that normally comes with security incident disclosures.

- Vendor-based sites

- When you visit a vendor-based site, you often obtain a depth of information unparalleled by any other source, partially because the vendor wants to impress you. However, because the vendor is also actively engaged in trying to thwart various security threats, you can also gain better insights into what you need to do to prepare for a particular threat. Sites such as Symantec Security Response make it possible to ascertain things like the current threat level on the Internet quickly and determine which threats present the greatest potential for problems for most people.

Warning

Vendor-based security sites are there to sell you security products from that vendor. You need to realize this fact when you go on the site because the articles will contain biases that lean toward getting a product that will solve the security threat. Sometimes you really do need a third-party product to solve a problem, but careful research, attention to detail, proper system configuration, and an update or two often do more to solve the threat than buying a product ever will. Make sure you review and validate the facts you get from a vendor-based security site before you act on them. Think about the methods you already have at your disposal to solve a problem before you buy yet another product.

Figure 16-1. Choosing the correct security threat source is important

Some sites specialize in consolidating information from other sources. For example, Security Focus, Open Source Vulnerability Database (OSVDB), and Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) provide indexes of information also found on other sites. Using a consolidated site can save you time, but also makes it possible that you’ll miss an important security notice because the site owner has a bias that is different from the needs of your organization.

An important thing to consider is that you really only need to visit a security site when you feel there is a security threat you need to research. Otherwise, your time is better spent looking for overviews of security threats you might need to deal with. Make sure you visit the kind of site that will best serve your needs for a particular threat. For example, an international threat perpetrated by one country against another will likely receive the best coverage on a government-supported site. Hackers who are trying to extort funds from you after encrypting your hard drive data are often detailed better at vendor-based sites. If you feel that a threat is likely pure hoax, make sure you visit a community-supported site first to verify it.

Getting Input from Consultants

All of the sources discussed so far in the chapter have one thing in common—they provide general information supported by an outside source. However, your business isn’t a general entity and has specific security needs based on the kinds of applications you run, the environment in which you run them, and the level of training your users have. In some cases, the general sources don’t provide enough information because they simply can’t provide it—the authors of those bits of information know nothing about your organization. In this case, you usually need to employ the services of a consultant to consider the security threats.

Warning

It’s important to remember that consultants are a paid resource, which means that they could (and probably will) provide a stronger level of bias than other sources you use. After all, the consultant is in business to make money. Some consultants are quite ethical and would never overcharge you on purpose; however, the fact that money is exchanging hands and the consultant has a more personal relationship with you than other sources do, will likely make the consultant a cautious source of information. You need to balance the deeper understanding that a consultant has about your particular setup with the fact that the level of bias is stronger as well.

A consultant can provide specific information about the specific threats faced by your organization in particular. The advice will make it possible to deal with the threats a lot faster than if you had to create a strategy of your own. Of course, the quality of the information comes with a price. Using a consultant is also the most expensive way to deal with security threats. For the most part, the majority of the sources provided in this chapter offer some level of free support. It’s best to use consultants when:

-

You already know that the threats are serious

-

You can’t create a strategy to handle them quickly

-

The methods required for handling the threats are outside the realm of skills your organization has to offer

-

Handling the threats requires coordination between several groups or contact with other companies

-

There is some other mitigating circumstance that makes handling the security threat yourself untenable

Avoiding Information Overload

So many hackers are doing so many things to make your life interesting that it would be exceptionally easy to go into overload on the issues that affect security today. Most people are facing a terrible case of information overload anyway. It’s possible to have an entire inbox filled with links to articles you really should read, but never get to due to scheduling concerns (such as those endless meetings that most organizations have). Even so, you need to spend some time trying to figure out which threats are terrifying enough to require action on your part, which is why you need to keep from getting overloaded in the first place. The following steps summarize techniques you can use to avoid information overload and potentially avoid the security threats you read about completely:

-

Choose security sources carefully. Make sure the security information sources you choose relate to your organization’s needs, present the information you need in a succinct manner, and provide just the details you need without becoming overwhelming.

-

Locate potential security fixes that don’t depend on changing your application. In some cases, the best security sources can provide you with a quick fix to your problem, such as installing a browser or other update.

-

Create a task-based approach to handling threats. If you can’t summarize a security threat in a single sentence, you don’t really understand it well enough to know whether you need to do anything. Developing the habit of summarizing the threat quickly as a single sentence description will save your time and effort in the long run.

-

Discard information sources that tend toward sensationalizing security threats. What you need is just the facts and nothing but the facts. When a source starts to peddle hype, you can’t depend on it to tell you about the real security threats that you really do need to fix.

-

Develop critical-thinking skills. Some of the smartest people around base their actions on the worst that could happen if they didn’t act. Thinking about threats in the form of a worst-case scenario helps you figure out which threats present the greatest risk so you can devote your time thwarting them.

-

Avoid the flash in the pan threat. Some threats only appear in a headline once and then you never read about them again. Even when the predictions about such threats are dire, you have to wonder just how dire they are when they don’t stick around long enough to make a second headline.

As part of your strategy for avoiding becoming overwhelmed, make sure you spend the time required to understand how threats really work. For example, you might have heard about some threats like rowhammer that can wreak havoc with a system. However, when you start reading further, you begin to understand that it’s an interesting hack, but requires the sort of system access that hackers normally lack when dealing with web applications. Consequently, you can probably ignore rowhammer for now. Of course, a great security resource would have told you that fact from the outset, but sometimes you need to perform the research on your own in order to avoid being inundated with information you really can’t use.

Note

Be sure to employ data filtering when you can. Performing quick searches on your accumulated information sources for particular keywords can help you determine whether a threat really is something you should consider overcoming. Many of the tools available on the market today make it possible to filter and reorganize information in various ways. Knowing how to use these tools effectively will save you time in the long run for a little extra effort learning the tool today.

Creating a Plan for Upgrades Based on Threats

When you receive information about a potential threat soon enough and the amount of code required to fix the problem is large enough, you may need to perform an upgrade of your application. Of course, you must first figure out whether you need to do anything at all. Some threats do merit attention, but are of a sort that won’t affect your application because they require some sort of special access or affect the use of software you don’t even have. The following sections help you determine whether an upgrade is needed based on security threat information and how to approach the upgrade once you know one is needed.

Anticipating Situations that Require No Action at All

Whenever you read about a security threat and research its implications, you need to keep in mind that the documentation you read will make the threat sound dire. And the threat is, in fact, dire for someone. However, the threat may not matter at all to you. Organizations often spend time and money reacting to threats that don’t pose any sort of problem for them. In short, they buy into the hysteria that surrounds security threats when there isn’t any need to do so. One of the things you need to consider as you review current security threats is whether they actually do apply to you. In many cases, they don’t apply and you don’t need to do anything about them. You can blithely slough them off without another thought.

Of course, the problem is in getting to the point where you know the threat doesn’t affect you. A missed threat represents a serious problem because it can open you to attack and the things that follow (such as a downed site or breached data). Assessing the potential risk of a particular security threat involves:

-

Determining whether you use the technology described as the entry point for the security threat

-

Considering whether the kind of access required to invoke the threat actually applies to your organization

-

Defining the circumstances under which your organization could be attacked and when the attack might occur

-

Reviewing the safeguards you currently have in place to determine whether they’re sufficient to thwart the attack

-

Ensuring that you have a strategy in place should the attack occur and you’re wrong about the hacker’s ability to invoke it on your organization

Deciding Between an Upgrade or an Update

Chapter 13 and Chapter 14 discuss naturally occurring upgrades and updates. However, in this case, you’re thinking about an upgrade or an update due to a security threat. Many of the same rules apply. An upgrade always indicates some type of significant code change, while an update may not require a code change at all, but may instead reflect a change in user interface or some other element that you can change quickly without modifying the underlying code. Consequently, the first demarcation between upgrades and updates are those that you normally apply when making any other change.

A security threat can change the intention and urgency of an upgrade or an update. In some cases, you need to tackle the problem in several parts:

-

Address the specific issue that the security threat focuses upon as an update.

-

Upgrade or update any supporting software (such as firewalls or the operating system) to ensure the security threat can’t attack the application from another direction.

-

Train users to avoid performing tasks in such a manner that they provide hackers with valuable information or access that the hacker can use to initiate the attack.

-

Modify any code surrounding the target code to ensure the application continues to work precisely as designed as an upgrade after you’ve deployed the update.

-

Perform an upgrade of any dependencies to ensure the entire application is stable.

-

Verify that the upgraded application continues to thwart the security threat by performing extensive testing targeted in the same manner that a hacker would use.

Not every security threat requires this extensive list of steps to overcome, but it’s important to consider each step when deciding how to proceed. You may find that just an update will suffice to thwart the attack or that an operating system upgrade is really all you need. The point is to consider every possible aspect of the security threat in relation to your application and its supporting data.

Warning

When faced with a zero-day attack, it’s always best to start with an update that you create and test using the shortest timeline possible. The hackers won’t wait for you to deploy the update before attacking your system. In fact, hackers are hoping that you’ll become embroiled in procedure and organizational politics—giving them more time to attack your application. Speed is an essential element of keeping hackers at bay, but make sure you always test any software before you deploy it to ensure you aren’t actually making things worse. Mitigating the security threat requires an accurate strategy delivered as quickly as possible.

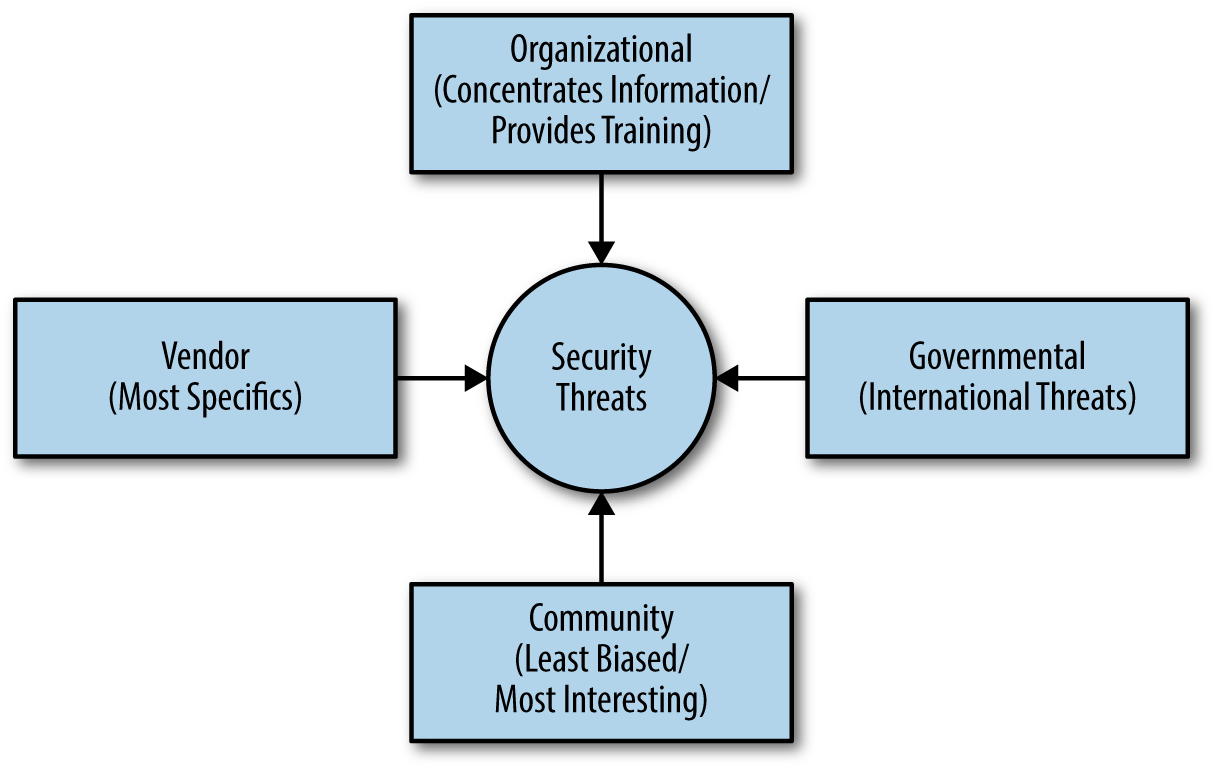

Sometimes you really do need to make quick decisions regarding the use of an upgrade or an update to fix a security threat. The steps in this section are certainly helpful, but the flowchart in Figure 16-2 provides an even faster method of making the determination.

Figure 16-2. Making the decision between upgrade and update quickly is sometimes necessary

Defining an Upgrade Plan

Chapter 13 describes the process for a standard upgrade for your application. It details a process that could require months to complete. Of course, you have time when you’re performing an upgrade of your application to perform every task carefully and completely. Security threats seldom wait long enough to provide you with months of waiting time to create an upgrade and deploy it. The only way that you obtain the level of advance warning to perform a long-term upgrade is to have someone in the right place to obtain information when it first becomes available (many ethical hackers give vendors three months to a year to fix problems before making them public knowledge).

Note

Constant testing of your application by an organization that specializes in security testing can provide you with longer lead times for upgrades. A security testing firm can make you aware of potential deficiencies in your application long before they become public knowledge. Of course, in order to get this level of advance knowledge, you must be willing to pay for the service, which can become quite expensive.

When working through an upgrade in response to a security threat, you need to consider methodologies that allow you to create the upgrade and test it incrementally as you work in order to deliver the upgrade in a shorter timeframe. Agile programming techniques can help you accomplish this task. Of course, if your organization doesn’t normally use agile programming techniques, the time lost in learning them won’t help much. Even so, part of your upgrade plan should include some methodology for creating the code and testing it on a much shorter schedule than is normal. After the threat has passed, you need to go back through the code and ensure you didn’t introduce yet more security holes in fixing the hole presented by the security threat.

In Chapter 14, “Performing Emergency Updates” discusses the need for a fast response team. In many cases, using this team to put the upgrade together will save time and possibly expense. The team is already used to working together to create updates quickly. Using it to create an upgrade in response to a security threat makes sense. However, you need to ensure that the team has the proper staffing to handle an upgrade. It may become necessary to add team members to provide services beyond those normally required for an update.

Warning

A deadly problem faced in many organizations is managers who have become hysterical and require constant updates. The “are we there yet?” problem slows progress on the upgrade considerably. The development team responsible for the upgrade should make regular reports to management, but management should also realize the need to let the development team work in peace. Otherwise, while an important team member is delivering yet another unnecessary report, hackers will invade your system and make your worst nightmares come true.

Creating a Plan for Updates Based on Threats

In some cases, you receive security threat information with such short lead time that you need to perform an update now and an upgrade later. Updates make fewer changes to application code and sometimes don’t affect the code at all. As part of planning for an update based on threat information, you need to consider whether the update is an emergency or not. In addition, you need to create a plan that considers the effect on any third-party software you may rely on to make your application work.

Verifying Updates Address Threats

The focus of this chapter is on speed of execution. When you identify a security threat, you need to act upon the information as quickly as possible. Consequently, an update is the preferred method of attacking the problem because updates require less time, fewer resources, and potentially cause fewer issues during testing. In this case, updates mean more than simply your application. Updates can include:

-

Adjustments to the security software already in place

-

Alterations of the host platform

-

Modifications of the host browser

-

Changes in procedure based on user training or other means

-

Updates to the underlying application through noncoded or lightly coded means

-

Modification of dependent software such as libraries, APIs, and microservices

Unfortunately, updates don’t always fix the problem. If the goal is to thwart a security threat, then finding the correct course of action first is the best way to proceed because time you waste trying other measures will simply delay the approach that works. The hackers aren’t waiting. Sometimes speed of execution comes down to performing more detailed fixes and simply admitting that you need more time than is probably convenient to effect a repair.

The crux of the matter is to look at the kind of attack that the hacker uses. For example, a man-in-the-middle attack may simply require that you encrypt incoming and outgoing data correctly and with greater care. In addition, it would require additional authentication and authorization measures. A hack of this sort isn’t easily fixed using an update because you’re looking at the way in which data is prepared, sent, and processed, which are three tasks that the underlying code must perform.

On the other hand, a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack does lend itself to the update model because you can change the security software settings, provide additional system resources, and reconfigure the platform to make such an attack harder. You can also fix social engineering hacks through user training, modification of the user interface, and changes to the application’s security settings. The kind of attack determines whether an update is a good choice. In many cases, you find that you can at least reduce the likelihood of an attack through an update, but may not be able to fix it completely.

Determining Whether the Threat Is an Emergency

When talking about security threats, it’s important to make a determination of whether the threat presents an emergency. Chapter 14 discussed the criteria for an emergency from a general update perspective. Here are some things to consider in addition to the general considerations when working through security threat issues:

Defining an Update Plan

Chapter 14 defines the requirements for an update plan. When working through an update that addresses a security threat, you want to use the fast response team to ensure the update is completed and tested in a timely manner (see “Creating a Fast Response Team” in Chapter 14). It’s also important to ensure that you consider the same sorts of issues discussed in “Defining an Upgrade Plan”. For example, using agile programming techniques will only make things go faster and reduce the time required to obtain a good update.

Asking for Updates from Third Parties

Something that many development teams forget in the rush to get a security update out the door is the need to address dependencies. If the dependent code is rock solid and you’re using the latest release, you might not have to check into an update immediately, but you do need to make the third party aware of potential security issues with their product and ask that these problems be addressed. Otherwise, any fixes you create might not continue to work—the hacker will simply choose another avenue of attack.