Copyright © 2016 John Mueller. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491928646 for release details.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-491-92864-6

[LSI]

This book is dedicated to the medical professionals who have helped restore my health—who have listened to all my woes and found ways to address them. Yes, I did need to follow the advice, but they were the ones who offered it. Good health is an exceptionally grand gift.

Ransomware, viruses, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, security breaches, and the like all bring to mind the one thing that anyone involved in managing applications hates—nightmares. It gets to the point where anyone who does anything to affect the security of an application or its associated data becomes gun shy—conservative to the point of absurdity. You don’t actually want the responsibility for securing the application—it just comes with the territory.

Adding to your burden, the disastrous results of any sort of mistake could haunt you for the rest of your life. Unlike most mistakes, you likely won’t sweep this one under the carpet either, because it’ll appear in the trade press where everyone can see it. Even if your name doesn’t become synonymous with security failure, there are always the ramifications of a security issue—legal woes, loss of job, and so on. So, how do you deal with this issue?

Hiding your head in the sand doesn’t appear to provide a solution—at least, not for very long. Security for Web Developers isn’t intended to tell you about every threat out there or resolve every security woe you’ll ever encounter. Instead, it provides you with guidelines and tools you need to resolve any security issue on your own—to be able to see a light at the end of the tunnel that doesn’t have something to do with a train. What this book is really about is being able to get a good night’s sleep knowing that you have what you need to get the job done right.

Security for Web Developers provides you with the resources you need to work through web application security problems. Yes, you also see some information about platforms, because browsers run on specific platforms. In addition, you might see some of these security issues when working with desktop applications simply because the security landscape occupies both application domains. However, this book focuses on security for web applications, no matter where those applications run. You can find information on everything from the latest smartphone to an older desktop, and everything in-between. The book breaks the information into the following parts, each of which takes you another step along the path to creating a better security plan for your organization:

The readers of this book could have any of a number of titles, such as web designer, frontend developer, UI designer, UX designer, interaction designer, art director, content strategist, dev ops, product manager, SEO specialist, data scientist, software engineer, or computer scientist. What you all have in common is a need to create web applications of some sort that are safe for users to interact with in a meaningful way. You’re all professionals who have created web applications before. What you may really need is to brush up on your security skills given the new climate of major application intrusions through nontraditional means, such as contaminating third-party APIs and libraries.

Security for Web Developers provides you with an end-to-end treatment of security, but it doesn’t provide a lot of handholding. This book assumes that you want the latest information on how to thwart security threats at several levels, including a reading of precisely which categories those threats occupy, and how hackers use them to thwart your security measures.

The book does include a few security programming examples. In order to use these examples, you need to have a good knowledge of CSS3, HTML5, and JavaScript programming techniques. However, if you don’t possess these skills, you can skip the programming examples and still obtain a considerable amount of information from the book. The programming examples provide details that only programmers will really care about.

Beyond the programming skills, it’s more important that you have some level of security training already. For example, if you don’t have any idea of what a man-in-the-middle attack is, you really need to read a more basic book first. This book obviously doesn’t assume you’re an expert who knows everything about man-in-the-middle attacks, but it does assume you’ve encountered the term before.

All you need to use the programming examples in this book is a text editor and browser. The text editor must output pure text, without any sort of formatting. It must also allow you to save the files using the correct file extensions for the example file (.html, .css, and .js). The various book editors, beta readers, and I tested the examples using the most popular browsers on the Linux, Mac, and Windows platforms. In fact, the examples were even tested using the Edge browser for Windows 10.

Icons provide emphasis of various sorts. This book uses a minimum of icons, but you need to know about each of them:

A note provides emphasis for important content that is slightly off-topic or perhaps of a nature where it would disrupt the normal flow of the text in the chapter. You need to read the notes because they usually provide pointers to additional information required to perform security tasks well. Notes also make it easier to find the important content you remember is in a certain location, but would have a hard time finding otherwise.

A warning contains information you must know about or you could suffer some dire fate. As with a note, the warning provides emphasis for special text, but this text tells you about potential issues that could cause you significant problems at some point. If you get nothing else out of a chapter, make sure you commit the meaning behind warnings to memory so that you can avoid costly errors later.

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant widthUsed for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width boldShows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italicShows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

Some of the text in this book receives special treatment. Here are a few of the conventions you need to know about:

Source code appears in special paragraphs in most cases to make it easier to read and use.

Sometimes, you see source code in a regular paragraph. The special formatting makes it easier to see.

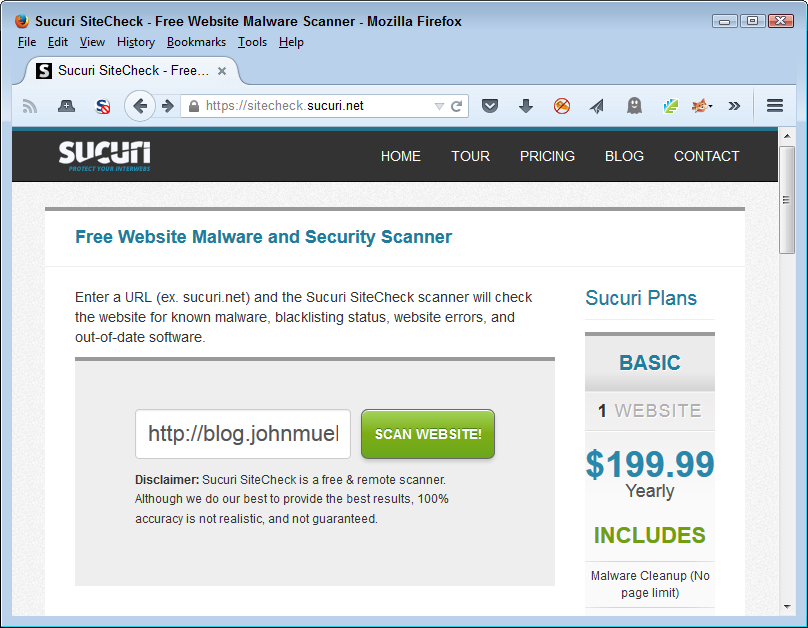

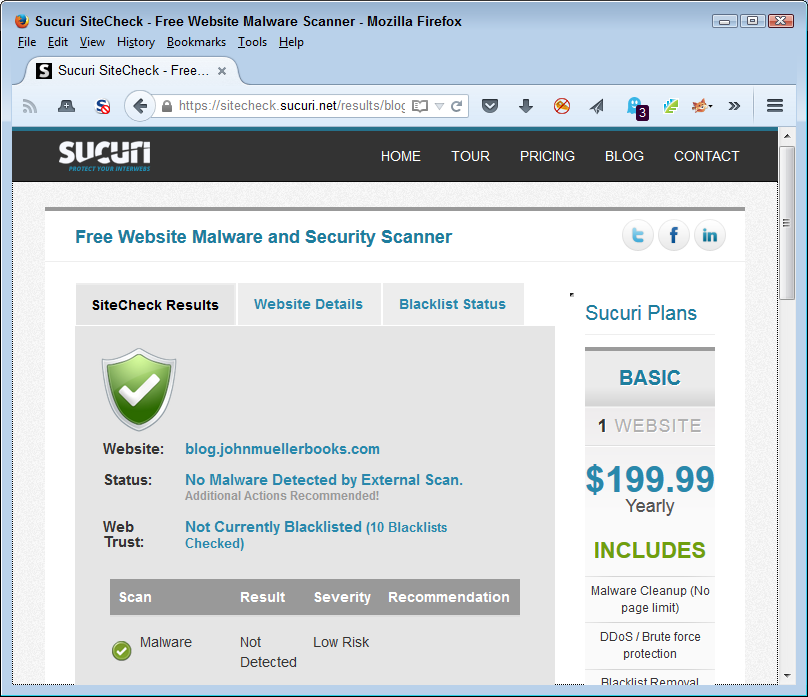

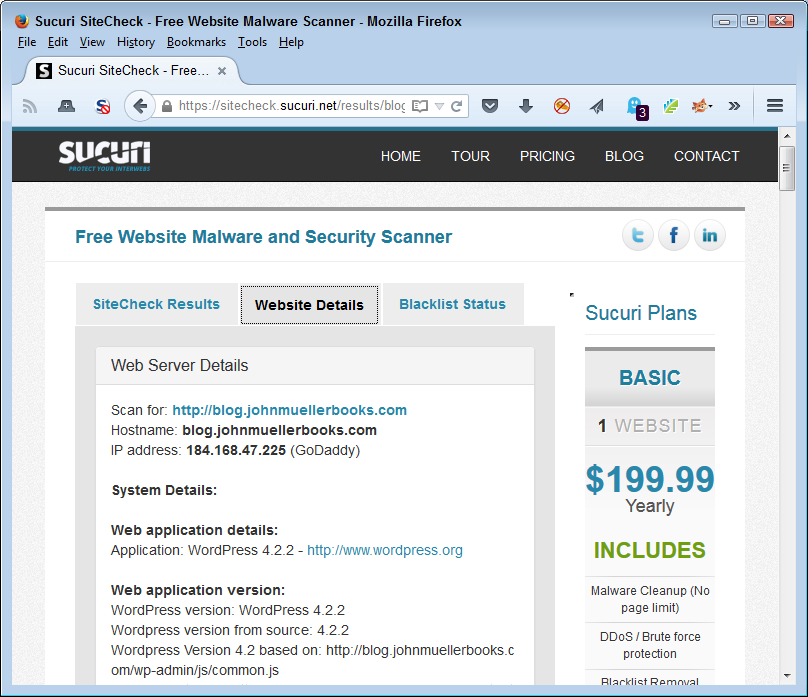

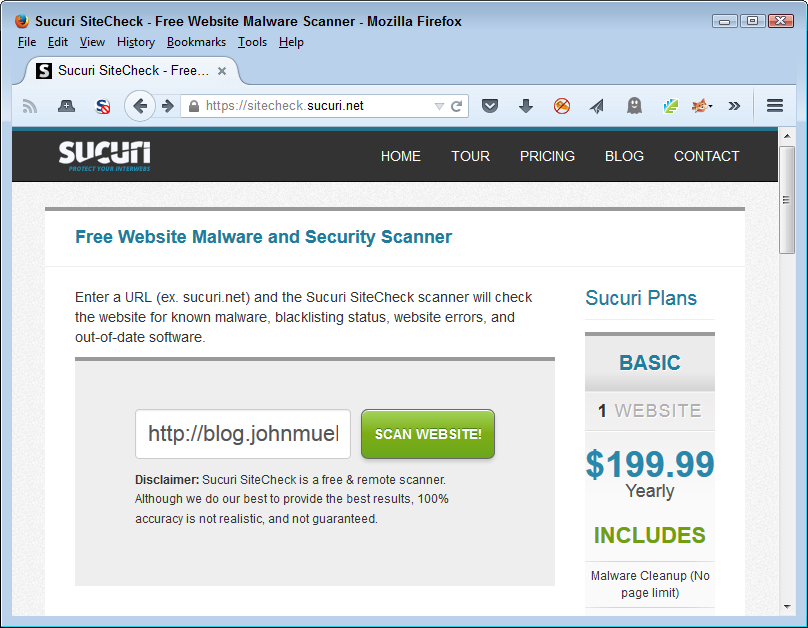

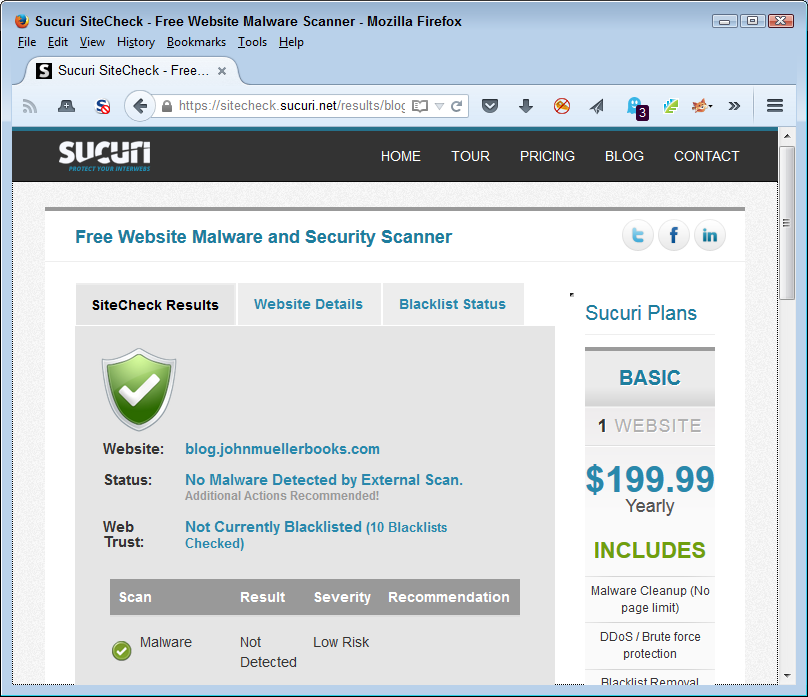

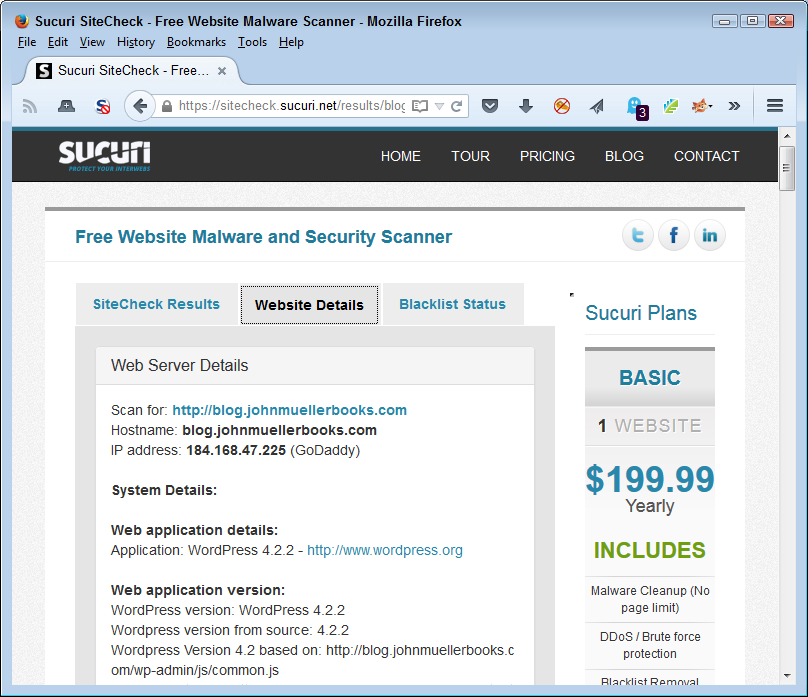

URLs, such as http://blog.johnmuellerbooks.com, appear in a special font to make them easier to find. This book uses many URLs so that you can find a lot of related information without having to search for it yourself.

I want to be sure you have the best reading experience possible. Please be sure to send any book-specific questions you might have to John@JohnMuellerBooks.com. You can also check out the blog posts for this book at http://blog.johnmuellerbooks.com/category/technical/security-for-web-developers/. The blog posts provide you with additional content and answer questions that readers commonly ask. If there are errata in the book, you can find the fixes on the blog as well.

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at https://github.com/oreillymedia/Security_for_Web_Developers.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Security for Web Developers by John Paul Mueller (O’Reilly). Copyright 2016 John Paul Mueller, 978-1-49192-864-6.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari Books Online is an on-demand digital library that delivers expert content in both book and video form from the world’s leading authors in technology and business.

Technology professionals, software developers, web designers, and business and creative professionals use Safari Books Online as their primary resource for research, problem solving, learning, and certification training.

Safari Books Online offers a range of plans and pricing for enterprise, government, education, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, and prepublication manuscripts in one fully searchable database from publishers like O’Reilly Media, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, Course Technology, and hundreds more. For more information about Safari Books Online, please visit us online.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://bit.ly/security-web-dev.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

Thanks to my wife, Rebecca. Although she is gone now, her spirit is in every book I write, in every word that appears on the page. She believed in me when no one else would.

Russ Mullen, Billy Rios, and Wade Woolwine deserve thanks for their technical edit of this book. All three technical editors greatly added to the accuracy and depth of the material you see here. In many cases, I was able to bounce ideas off them and ask for their help in researching essential book topics.

Matt Wagner, my agent, deserves credit for helping me get the contract in the first place and taking care of all the details that most authors don’t really consider. I always appreciate his assistance. It’s good to know that someone wants to help.

A number of people read all or part of this book to help me refine the approach, test scripts, and generally provide input that all readers wish they could have. These unpaid volunteers helped in ways too numerous to mention here. I especially appreciate the efforts of Eva Beattie, Glenn A. Russell, and Luca Massaron, who provided general input, read the entire book, and selflessly devoted themselves to this project.

Finally, I would like to thank Meg Foley, Nicole Shelby, Jasmine Kwityn, and the rest of the editorial and production staff.

In this part of the book, you discover how to create a security plan that you can use when writing applications. Having a good security plan ensures that your application actually meets specific goals and that others can discuss how to implement security with the development team. Without a good security plan in place, hackers often find easy access to the application and cause all kinds of problems for your organization. Chapter 1 gets you started by helping you understand the components of a good security plan.

It’s important to realize that the security plan doesn’t just focus on the application, but also on how users employ the application. Every successful application keeps the user in mind, as described in Chapter 2.

In addition, you need to understand that applications no longer exist in a vacuum—they interact with online data sources and rely on third-party coding. With this in mind, you must also consider how third-party solutions can affect your application, both positively and negatively. Using third-party solutions can also greatly decrease your coding time. Chapter 3 helps you achieve this goal.

Data is the most important resource that any business owns. It’s literally possible to replace any part of a business except the data. When the data is modified, corrupted, stolen, or deleted, a business can suffer serious loss. In fact, a business that has enough go wrong with its data can simply cease to exist. The focus of security, therefore, is not hackers, applications, networks, or anything else someone might have told you—it’s data. Therefore, this book is about data security, which encompasses a broad range of other topics, but it’s important to get right to the point of what you’re really looking to protect when you read about these other topics.

Unfortunately, data isn’t much use sitting alone in the dark. No matter how fancy your server is, no matter how capable the database that holds the data, the data isn’t worth much until you do something with it. The need to manage data brings applications into the picture and the use of applications to manage data is why this introductory chapter talks about the application environment.

However, before you go any further, it’s important to decide precisely how applications and data interact because the rest of the chapter isn’t very helpful without this insight. An application performs just four operations on data, no matter how incredibly complex the application might become. You can define these operations by the CRUD acronym:

Create

Read

Update

Delete

The sections that follow discuss data, applications, and CRUD as they relate to the web environment. You discover how security affects all three aspects of web development, keeping in mind that even though data is the focus, the application performs the required CRUD tasks. Keeping your data safe means understanding the application environment and therefore the threats to the data the application manages.

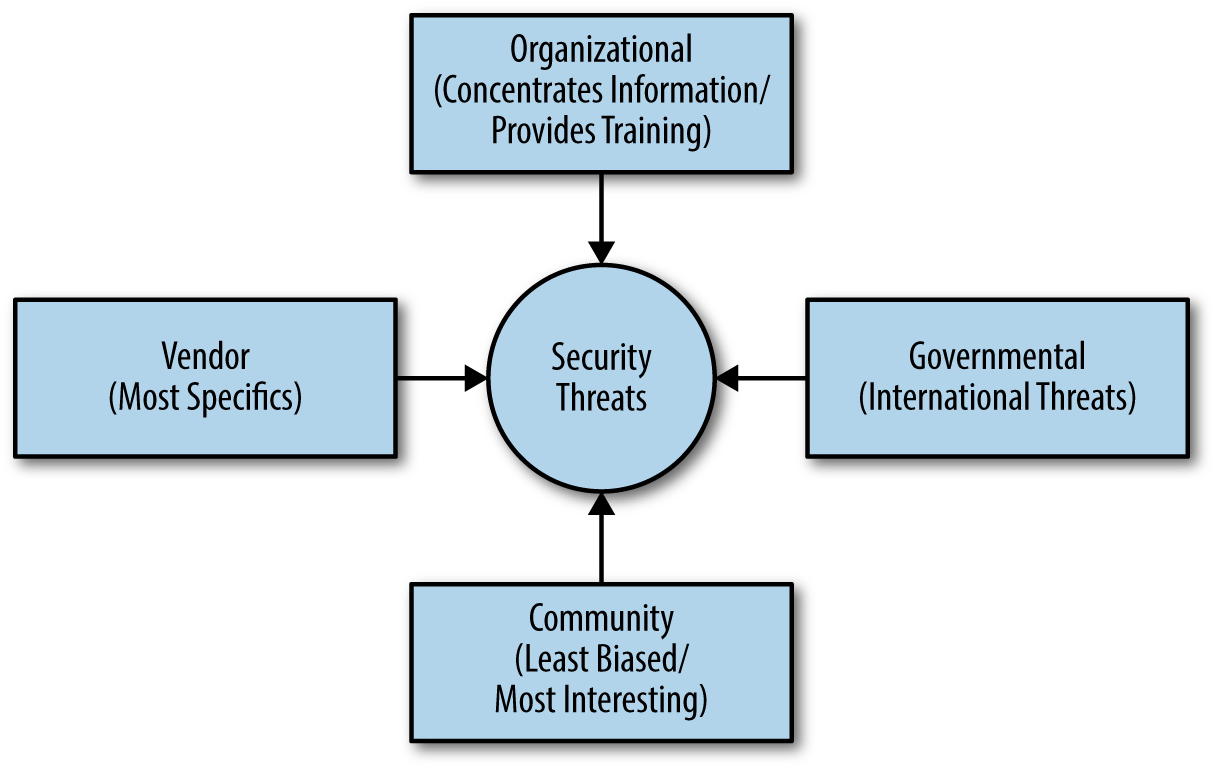

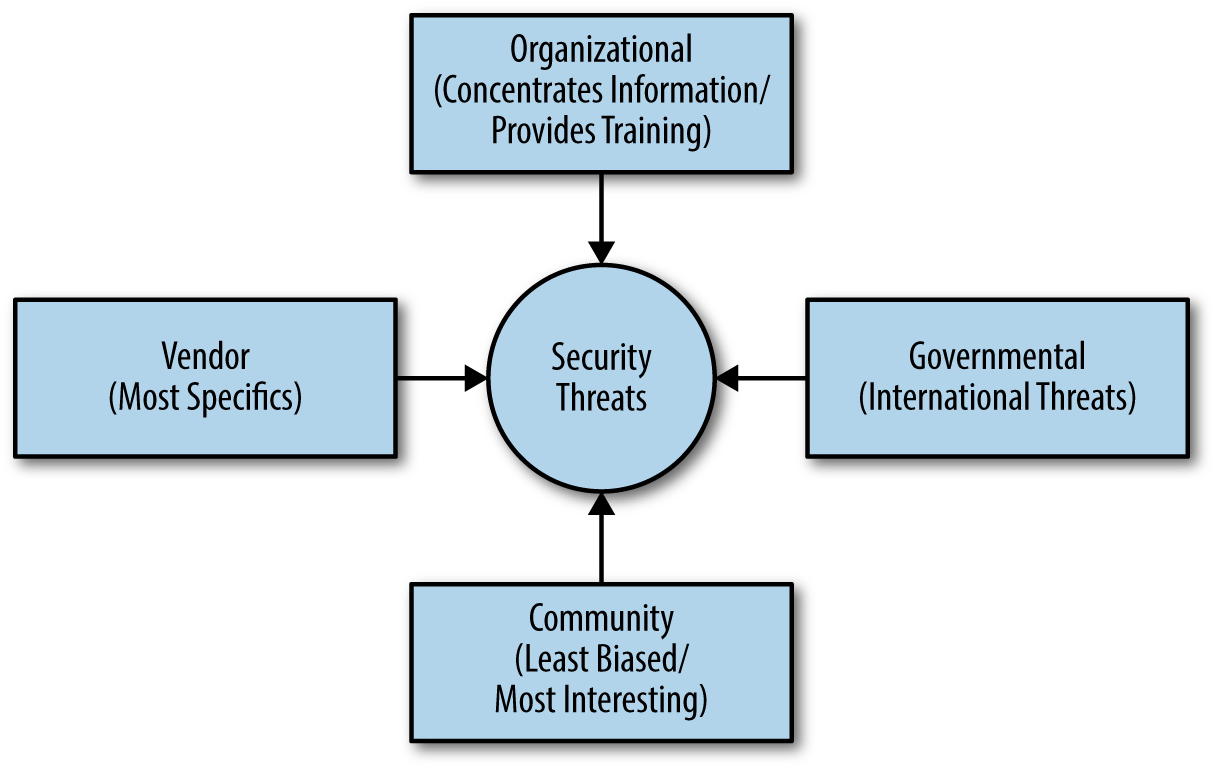

You can find lists of web application threats all over the Internet. Some of the lists are comprehensive and don’t necessarily have a bias, some address what the author feels are the most important threats, some tell you about the most commonly occurring threats, and you can find all sorts of other lists out there. The problem with all these lists is that the author doesn’t know your application. A SQL injection attack is only successful when your application uses SQL in some way—perhaps it doesn’t.

Obviously you need to get ideas on what to check from somewhere, and these lists do make a good starting place. However, you need to consider the list content in light of your application. In addition, don’t rely on just one list—use multiple lists so that you obtain better coverage of the threats that could possibly threaten your application. With this need in mind, here is a list of the most common threats you see with web applications today:

Code injection occurs more often than you might think. In some cases, the code injection isn’t even part of an attack, but it might as well be. A recent article discusses how Internet service providers (ISPs) are injecting JavaScript code into the data stream in order to overlay ads on top of a page. In order to determine what sort of ad to provide, the ISP also monitors the traffic.

Few experts remind you to check your output data. However, you don’t actually know that your own application is trustworthy. A hacker could modify it to allow tainted output data. Verification checks should include output data as well as input data.

Some experts will emphasize validating input data for some uses and leave the requirement off for other uses. Always validate any data you receive from anywhere. You have no way of knowing what vehicle a hacker will use to obtain access to your system or cause damage in other ways. Input data is always suspect, even when the data comes from your own server. Being paranoid is a good thing when you’re performing security-related tasks.

Hackers can still manipulate parameters with enough time and effort. It’s also important to define parameter value ranges and data types carefully to reduce the potential problems presented by this attack.

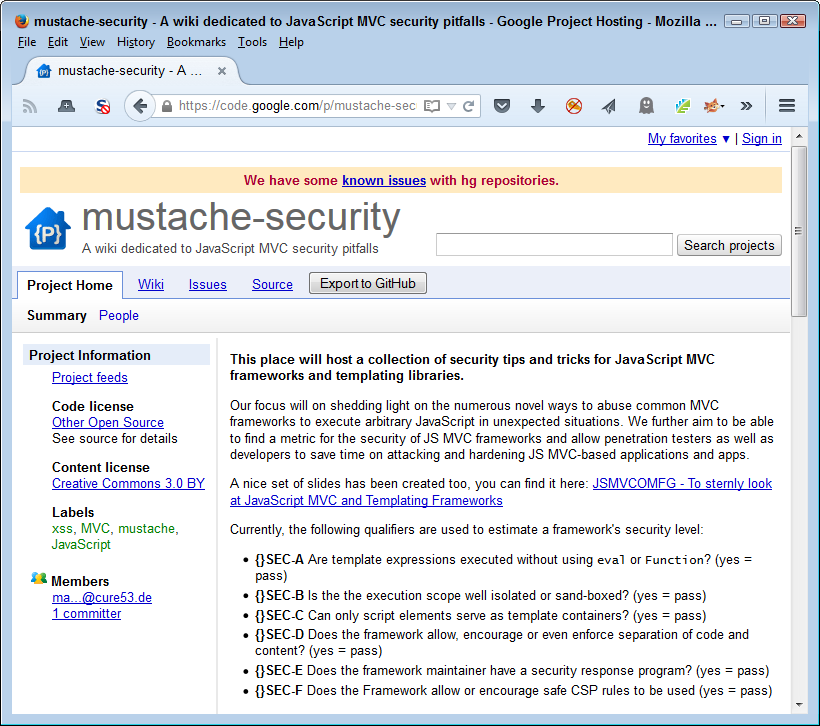

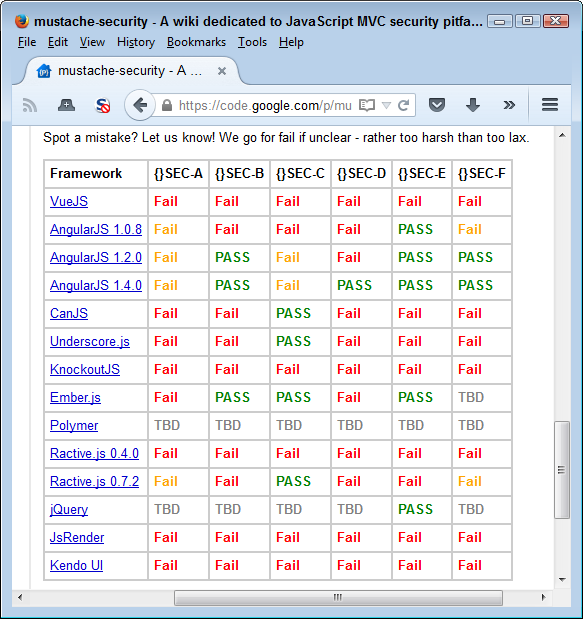

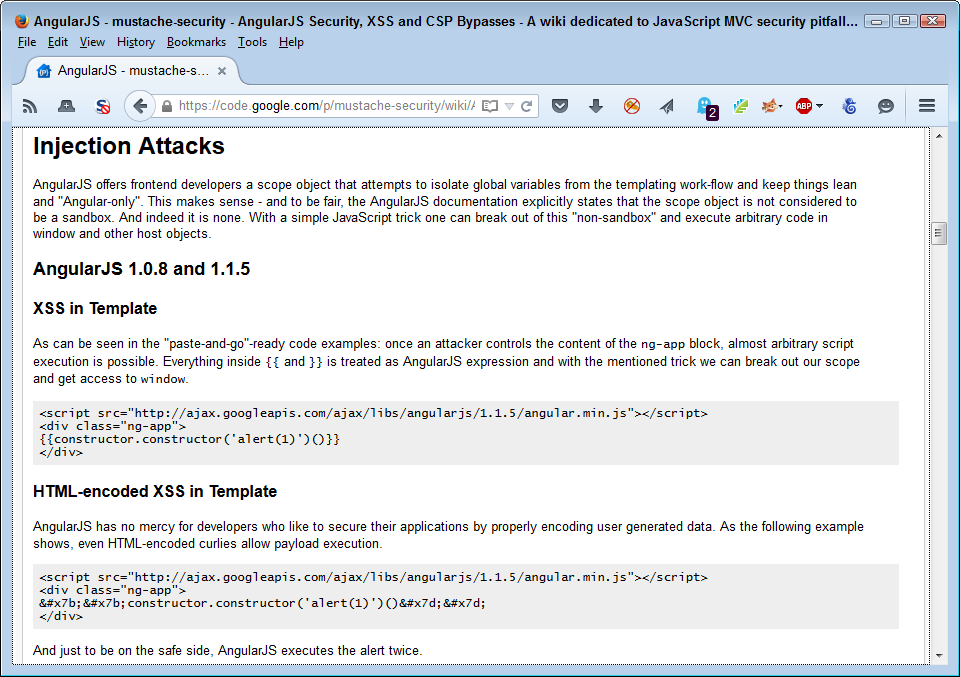

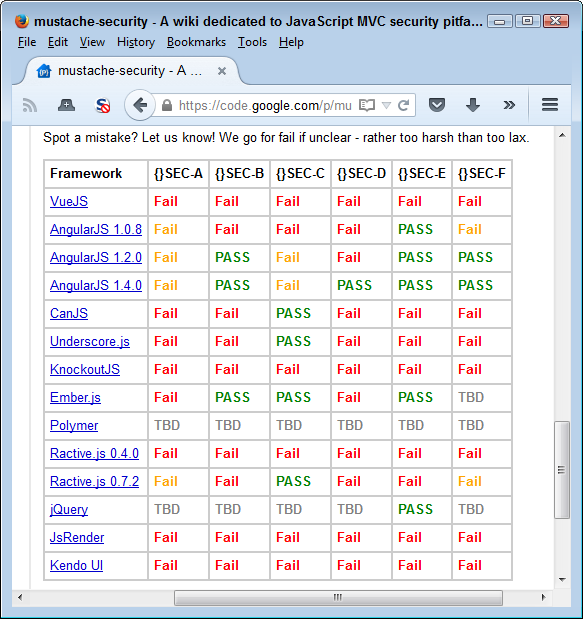

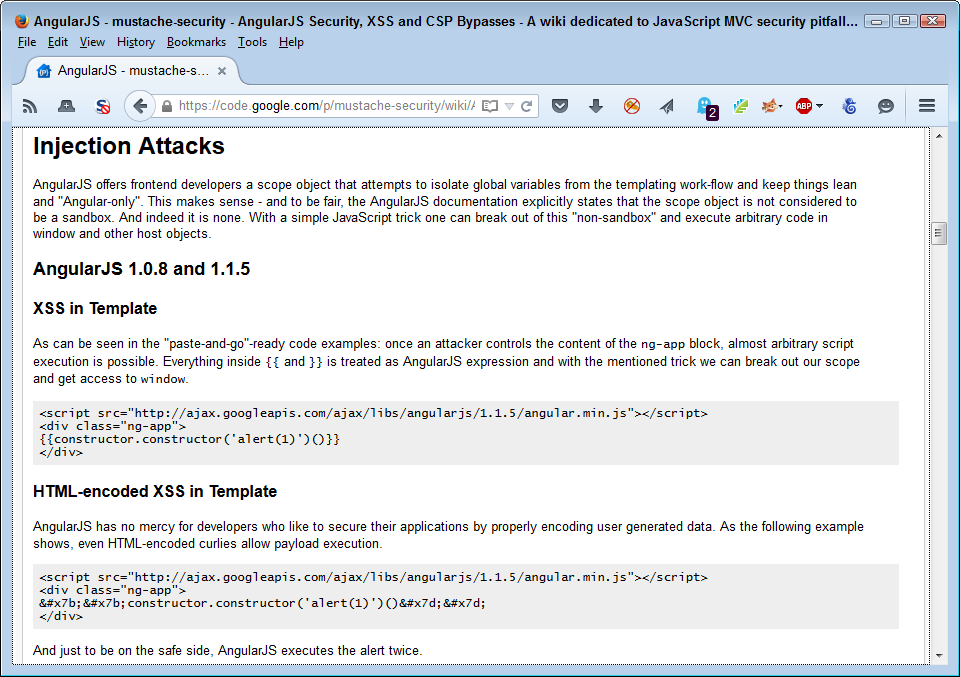

Many experts will recommend that you use vetted libraries and frameworks to perform dangerous tasks. However, these add-ons are simply more code. Hackers find methods for corrupting and circumventing library and framework code on a regular basis. You still have a need to ensure your application and any code it relies upon interacts with outside elements safely, which means performing extensive testing. Using libraries and frameworks does reduce your support costs and ensures that you get timely fixes for bugs, but the bugs still exist and you still need to be on guard. There is no security silver bullet. Chapter 6 contains more information about working with libraries and frameworks.

This may look like a lot of different threats, but if you search long enough online, you could easily triple the size of this list and not even begin to scratch the surface of the ways in which a hacker can make your life interesting. As this book progresses, you’ll encounter a much larger number of threat types and start to discover ways to overcome them. Don’t worry, in most cases the fixes end up being common sense and a single fix can resolve more than one problem. For example, look through the list again and you’ll find that simply using HTTPS solves a number of these problems.

The purpose of software is to interact with data. However, software itself is a kind of data. In fact, data comes in many forms that you might not otherwise consider, and the effect of data is wider ranging that you might normally think. With the Internet of Things (IoT), it’s now possible for data to have both abstract and physical effects in ways that no one could imagine even a few years ago. A hacker gaining access to the right application can do things like damage the electrical grid or poison the water system. On a more personal level, the same hacker could potentially raise the temperature of your home to some terrifying level, turn off all the lights, or spy on you through your webcam, to name just a few examples. The point of SSA is that software needs some type of regulation to ensure it doesn’t cause the loss, inaccuracy, alteration, unavailability, or misuse of the data and resources that it uses, controls, and protects. This requirement appears as part of SSA. The following sections discuss SSA in more detail.

SSA isn’t an actual standard at this time. It’s a concept that many organizations quantify and put into writing based on that organization’s needs. The same basic patterns appear in many of these documents and the term SSA refers to the practice of ensuring software remains secure. You can see how SSA affects many organizations, such as Oracle and Microsoft, by reviewing their online SSA documentation. In fact, many large organizations now have some form of SSA in place.

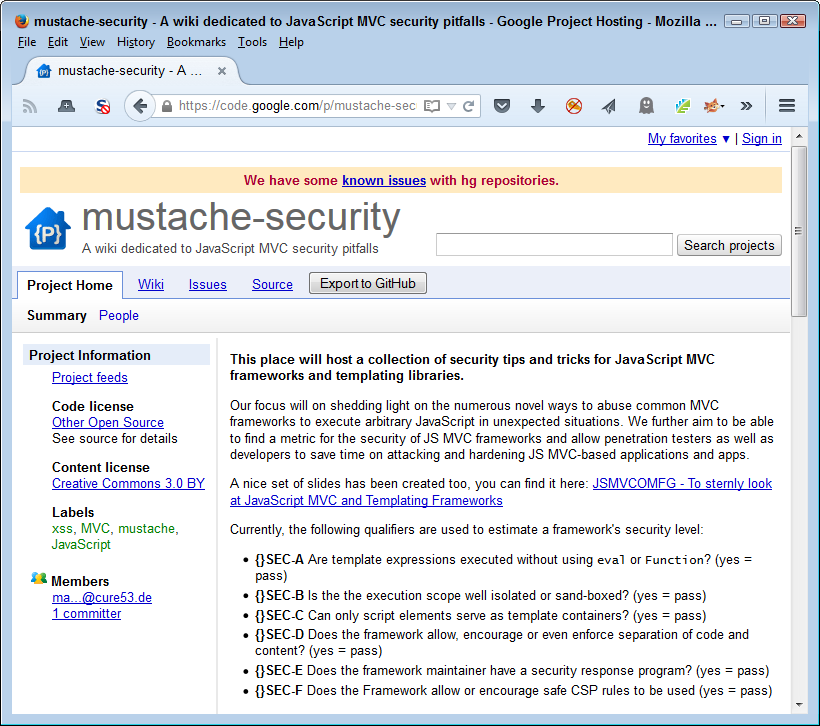

One of the main sites you need to know about in order to make SSA a reality in web applications is the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP); see Figure 1-1. The site breaks down the process required to make the OWASP Security Software Assurance Process (OSSAP) part of the Software Development Lifecycle (SDLC). Yes, that’s a whole bunch of alphabet soup, but you need to know about this group in order to create a process for your application that matches the work done by other organizations. In addition, the information on this site helps you develop a security process for your application that actually works, is part of the development process, and won’t cost you a lot of time in creating your own process.

Although OSSAP does provide a great framework for ensuring your application meets SSA requirements, there is no requirement that you interact with this group in any way. The group does license its approach to SSA. However, at this time, the group is just getting underway and you’ll find a lot of TBDs on the site which the group plans to fill in as time passes. Of course, you need a plan for today, so OWASP and its OSSAP present a place for you to research solutions for now and possibly get additional help later.

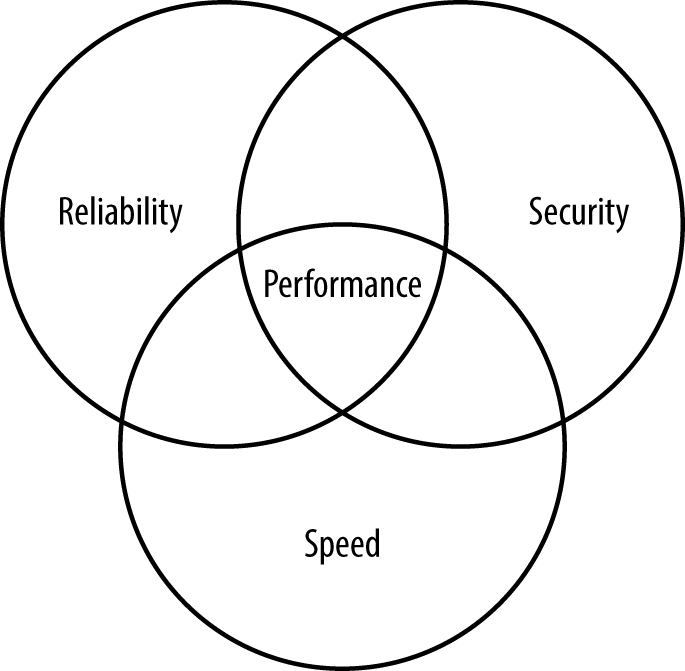

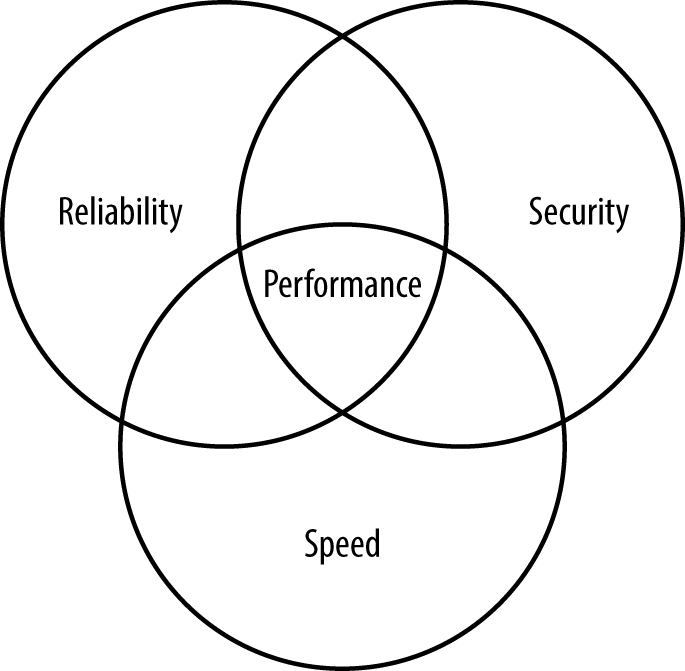

The whole reason to apply SSA to your application as part of the SDLC is to ensure that the software is as reliable and error free as you can make it. When talking with some people, the implication is that SSA will fix every potential security problem that you might encounter, but this simply isn’t the case. SSA will improve your software, but you can’t find any pieces of software anywhere that are error free. Assuming that you did manage to create a piece of error-free software, you still have user, environment, network, and all software of other security issues to consider. Consequently, SSA is simply one piece of a much larger security picture and implementing SSA will only fix so many security issues. The best thing to do is to continue seeing security as an ongoing process.

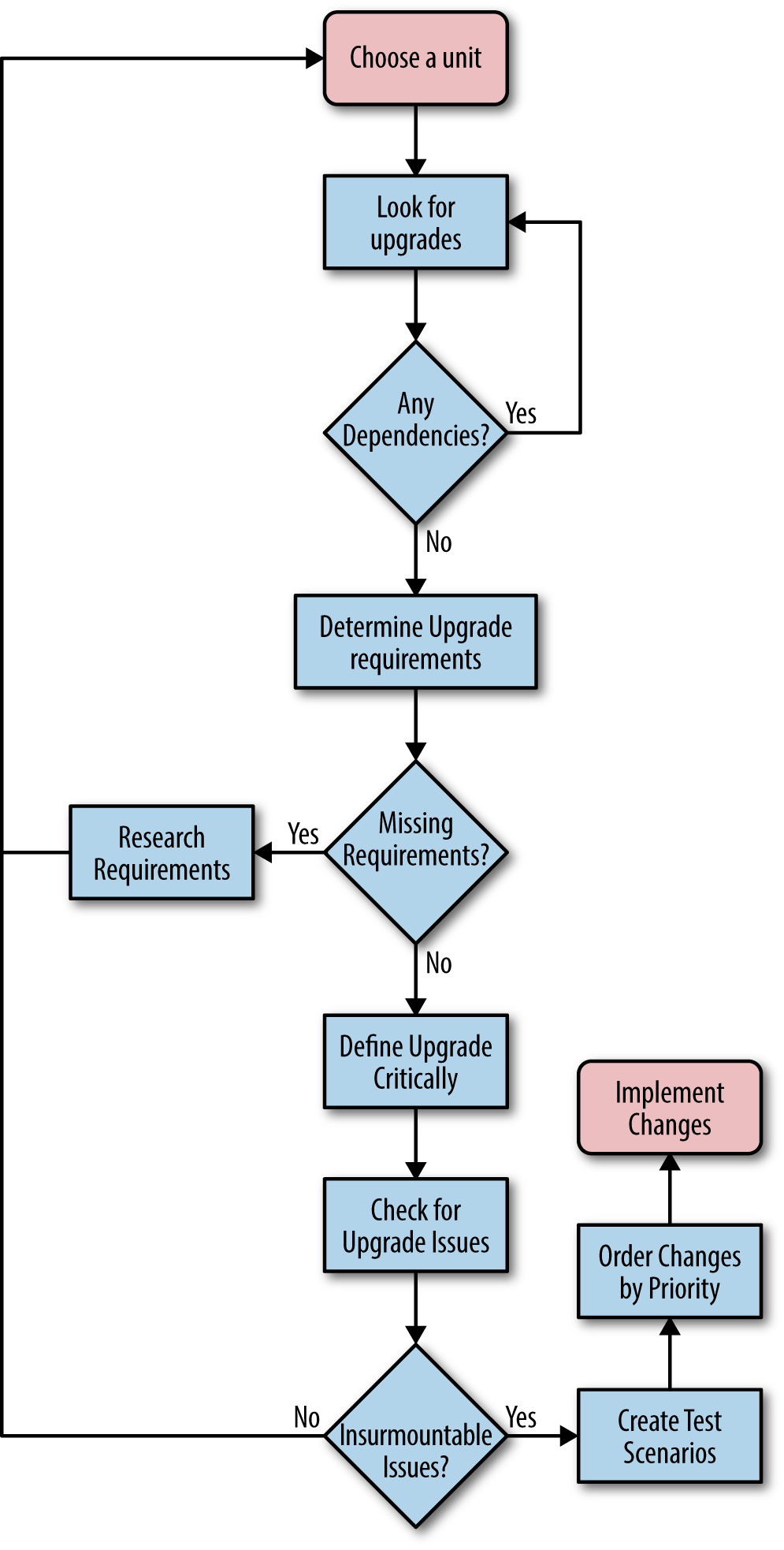

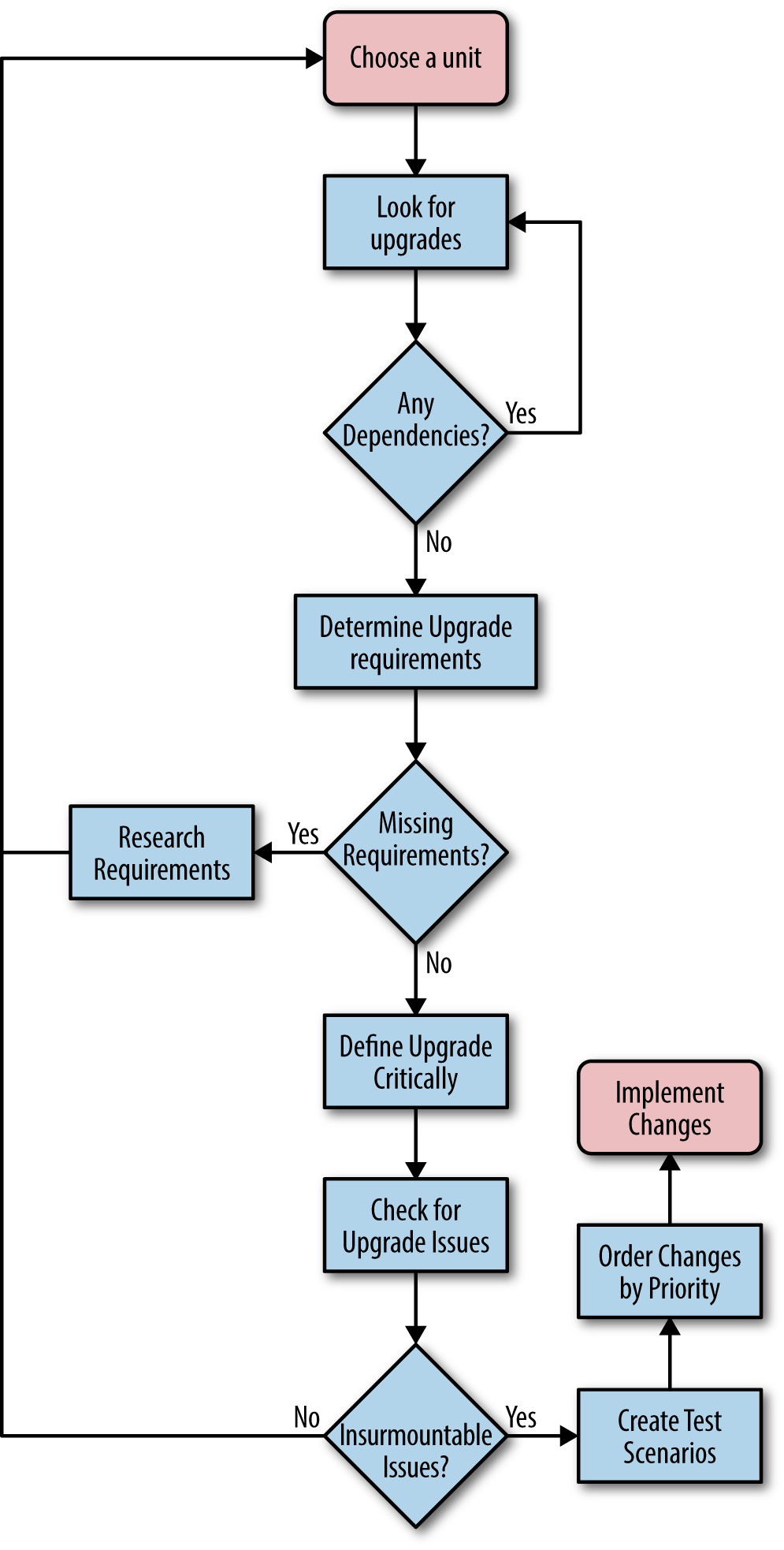

The initial step in implementing SSA as part of your application is to define the SSA requirements. These requirements help you determine the current state of your software, the issues that require resolution, and the severity of those issues. After the issues are defined, you can determine the remediation process and any other requirements needed to ensure that the software remains secure. In fact, you can break SSA down into eight steps:

Evaluate the software and develop a plan to remediate it.

Define the risks that the security issues represent to the data and categorize these risks to remediate the worst risks first.

Perform a complete code review.

Implement the required changes.

Test the fixes you create and verify that they actually do work on the production system.

Define a defense for protecting application access and therefore the data that the application manages.

Measure the effectiveness of the changes you have made.

Educate management, users, and developers in the proper methods to ensure good application security.

This process involves identifying the various pieces of data that your application touches in some way, including its own code and configuration information. Once you identify every piece of data, you categorize it to identify the level of security required to protect that data. Data can have many levels of categorization and the way in which you categorize the data depends on your organization’s needs and the orientation of the data. For example, some data may simply inconvenience the organization, while other data could potentially cause harm to humans. The definition of how data security breaches affects the security environment as a whole is essential.

After the data categorization process is complete, it’s possible to begin using the information to perform a variety of tasks. For example, you can consider how to reduce vulnerabilities by:

Creating coding standards

Implementing mandatory developer training

Hiring security leaders within development groups

Using automated testing procedures that specifically locate security issues

All of these methods point to resources that the organization interacts with and relies upon to ensure the application manages data correctly. Categorizing resources means determining how much emphasis to place on a particular resource. For example, denying developers training will have a bigger impact than denying individual application users training because the developers work with the application as a whole. Of course, training is essential for everyone. In this case, categorizing resources of all sorts helps you determine where and how to spend money in order to obtain the best return on investment (ROI), while still meeting application security goals.

As part of SSA, you need to perform an analysis on your application (including threat modeling, user interface flaws, and data presentation flaws). It’s important to know precisely what sorts of weaknesses your code could contain. The operative word here is could. Until you perform in-depth analysis, you have no way of knowing the actual security problems in your code. Web applications are especially adept at hiding issues because, unlike desktop applications, the code can appear in numerous places and scripts tend to hide problems that compiled applications don’t have because the code is interpreted at runtime, rather than compile time.

It’s important to understand that security isn’t just about the code—it’s also about the tools required to create the code and the skill of the developers employing those tools. When an organization chooses the wrong tools for the job, the risk of a security breach becomes much higher because the tools may not create code that performs precisely as expected. Likewise, when developers using the tool don’t have the required skills, it’s hardly surprising that the software has security holes that a more skilled developer would avoid.

Some experts claim that there are companies that actually allow substandard work. In most cases, the excuse for allowing such work is that the application development process is behind schedule or that the organization lacks required tools or expertise. The fact that an organization may employ software designed to help address security issues (such as a firewall), doesn’t relieve the developer of the responsibility to create secure code. Organizations need to maintain coding standards to ensure a good result.

Interacting with an application and the data it manages is a process. Although users might perform tasks in a seemingly random fashion, specific tasks follow patterns that occur because the user must follow a procedure in order to obtain a good result. By documenting and understanding these procedures, you can analyze application logic from a practical perspective. Users rely on a particular procedure because of the way in which developers design the application. Changing the design will necessarily change the procedure.

The point of the analysis is to look for security holes in the procedure. For example, the application may allow the user to remain logged in, even if it doesn’t detect activity for an extended period. The problem is that the user might not even be present—someone else could access the application using the user’s credentials and no one would be the wiser because everyone would think that the user is logged in using the same system as always.

However, data holes can take other forms. A part number might consist of various quantifiable elements. In order to obtain a good part number, the application could ask for the elements, rather than the part number as a whole, and build the part number from those elements. The idea is to make the procedure cleaner, clearer, and less error prone so that the database doesn’t end up containing a lot of bad information.

It may not seem like you can perform much analysis on data from a security perspective, but there really are a lot of issues to consider. In fact, data analysis is one of the areas where organizations fall down most because the emphasis is on how to manage and use the data, rather than on how to secure the data (it’s reasonable to assume you need to address all three issues). When analyzing the data, you must consider these issues:

Who can access the data

What format is used to store the data

When the data is accessible

Where the data is stored

Why each data item is made available as part of the application

How the data is broken into components and the result of combining the data for application use

For example, some applications fail to practice data hiding, which is an essential feature of any good application. Data hiding means giving the user only the amount of information actually needed to perform any given task.

Applications also format some data incorrectly. For example, storing passwords as text will almost certainly cause problems if someone manages to break in. A better route is to store the password hash using a secure algorithm (one that hasn’t been broken). The hash isn’t at all valuable to someone who has broken in because the application needs the password on which the hash is based.

Making all data accessible all the time is also a bad idea. Sensitive data should only appear on screen when someone is available to monitor its use and react immediately should the user do something unexpected.

Storing sensitive data in the cloud is a particularly bad idea. Yes, using cloud storage makes the data more readily available and faster to access as well, but it also makes the data vulnerable. Store sensitive data on local servers when you have direct access to all the security features used to keep the data safe.

Application developers also have a propensity for making too much information available. You use data hiding to keep manager-specific data hidden from other kinds of users. However, some data has no place in the application at all. If no one actually needs a piece of data to perform a task, then don’t add the data to the application.

Many data items today are an aggregation of other data elements. It’s possible for a hacker to learn a lot about your organization by detecting the form of aggregation used and taking the data item apart to discover the constituent parts. It’s important to consider how the data is put together and to add safeguards that make it harder to discover the source of that data.

A big problem with software today is the inclusion of gratuitous features. An application is supposed to meet a specific set of goals or perform a specific set of tasks. Invariably, someone gets the idea that the software might be somehow better if it had certain features that have nothing to do with the core goals the software is supposed to meet. The term feature bloat has been around for a long time. You normally see it discussed in a monetary sense—as the source of application speed problems, the elevator of user training costs, and the wrecker of development schedules. However, application interface issues, those that are often most affected by feature bloat, have a significant impact on security in the form of increased attack surface. Every time you increase the attack surface, you provide more opportunities for a hacker to obtain access to your organization. Getting rid of gratuitous features or moving them to an entirely different application will reduce the attack surface—making your application a lot more secure. Of course, you’ll save money too.

Another potential problem is the hint interface—one that actually gives the security features of the application away by providing a potential hacker with too much information or too many features. Although it’s necessary to offer a way for the user retrieve a lost password, some implementations actually make it possible for a hacker to retrieve the user’s password and become that user. The hacker might even lock the real user out of the account by changing the password (this action would, however, be counterproductive because an administrator could restore the user’s access quite easily). A better system is to ensure that the user actually made the request before doing anything and then ensuring that the administrator sends the login information in a secure manner.

A constraint is simply a method of ensuring that actions meet specific criteria before the action is allowed. For example, disallowing access to data elements unless the user has a right to access them is a kind of constraint. However, constraints have other forms that are more important. The most important constraint is determining how any given user can manage data. Most users only require read access to data, yet applications commonly provide read/write access, which opens a huge security hole.

Data has constraints to consider as well. When working with data, you must define precisely what makes the data unique and ensure the application doesn’t break any rules regarding that uniqueness. With this in mind, you generally need to consider these kinds of constraints:

The application environment is defined by the languages used to create the application. Just as every language has functionality that makes it perform certain tasks well, every language also has potential problems that make it a security risk. Even low-level languages, despite their flexibility, have problems induced by complexity. Of course, web-based applications commonly rely on three particular languages: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. The following sections describe some of the language-specific issues related to these particular languages.

HTML5 has become extremely popular because it supports an incredibly broad range of platforms. The same application can work well on a user’s desktop, tablet, and smartphone without any special coding on the part of the developer. Often, libraries, APIs, and microservices provide content in a form that matches the host system automatically, without any developer intervention. However, the flexibility that HTML5 provides can also be problematic. The following list describes some key security issues you experience when working with HTML5:

Applications rely heavily on CSS3 to create great-looking presentations without hardcoding the information for every device. Libraries of preexisting CSS3 code makes it easy to create professional-looking applications that a user can change to meet any need. For example, a user may need a different presentation for a particular device or require the presentation use a specific format to meet a special need. The following list describes some key security issues you experience when working with CSS3:

The combination of JavaScript with HTML5 has created the whole web application phenomenon. Without the combination of the two languages, it wouldn’t be possible to create applications that run well anywhere on any device. Users couldn’t even think about asking for that sort of application in the past because it just wasn’t possible to provide it. Today, a user can perform work anywhere using a device that’s appropriate for the location. However, JavaScript is a scripted language that can have some serious security holes. The following list describes some key security issues you experience when working with JavaScript:

An endpoint is a destination for network traffic, such as a service or a browser. When packets reach the endpoint, the data they contain is unpacked and provided to the application for further processing. Endpoint security is essential because endpoints represent a major point of entry for networks. Unless the endpoint is secure, the network will receive bad data transmissions. In addition, broken endpoint security can cause harm to other nodes on the network. The following sections discuss three phases of endpoint security: prevention, detection, and remediation.

It’s important not to underestimate the effect of endpoint security on applications and network infrastructure. Some endpoint scenarios become quite complex and their consequences hard to detect or even understand. For example, a recent article discusses a router attack that depends on the attacker directing an unsuspecting user to a special site. The attack focuses on the router that the user depends upon to make Domain Name System (DNS) requests. By obtaining full control over the router, the attacker can redirect the user to locations that the attacker controls.

The first step in avoiding a trap is to admit the trap exists in the first place. The problem is that most companies today don’t think that they’ll experience a data breach—it always happens to the other company—the one with lax security. However, according to the Ponemon Institute’s 2014 Global Report on the Cost of Cyber Crime, the cost of cybercrime was $12.7 million in 2014, which is up from the $6.5 million in 2010. Obviously, all those break-ins don’t just happen at someone else’s company—they could easily happen at yours, so it’s beneficial to assume that some hacker, somewhere, has targeted your organization. In fact, if you start out with the notion that a hacker will not only break into your organization, but also make off with the goods, you can actually start to prepare for the real-world scenario. Any application you build must be robust enough to:

Withstand common attacks

Report intrusions when your security fails to work as expected

Avoid making assumptions about where breaches will occur

Assume that, even with training, users will make mistakes causing a breach

Don’t assume that security breaches only happen on some platforms. A security breach can happen on any platform that runs anything other than custom software. The less prepared that the developers for a particular platform are, the more devastating the breach becomes. For example, many people would consider point-of-sale (POS) terminals safe from attack. However, hackers are currently attacking these devices vigorously in order to obtain credit card information access. The interesting thing about this particular exploit is that it wouldn’t work if employees weren’t using the POS terminals incorrectly. This is an instance where training and strong policies could help keep the system safe. Of course, the applications should still be robust enough to thwart attacks.

As the book progresses, you find some useful techniques for making a breach less likely. The essentials of preventing a breach, once you admit a breach can (and probably will) occur, are to:

Create applications that users understand and like to use (see Chapter 2)

Choose external data sources carefully (see “Accessing External Data” for details)

Build applications that provide natural intrusion barriers (see Chapter 4)

Test the reliability of the code you create, and carefully record both downtime and causes (see Chapter 5)

Choose libraries, APIs, and microservices with care (see “Using External Code and Resources” for details)

Implement a comprehensive testing strategy for all application elements, even those you don’t own (see Part III for details)

Manage your application components to ensure application defenses don’t languish after the application is released (see Part IV for details)

Keep up to date on current security threats and strategies for overcoming them (see Chapter 16)

Train your developers to think about security from beginning to end of every project (see Chapter 17)

The last thing that any company wants to happen is to hear about a security breach second or third hand. Reading about your organization’s inability to protect user data in the trade press is probably the most rotten way to start any day, yet this is how many organizations learn about security breaches. Companies that assume a data breach has already occurred are the least likely to suffer permanent damage from a data breach and most likely to save money in the end. Instead of wasting time and resources fixing a data breach after it has happened, your company can detect the data breach as it occurs and stop it before it becomes a problem. Detection means providing the required code as part of your application and then ensuring these detection methods are designed to work with the current security threats.

Your organization, as a whole, will need a breach response team. However, your development team also needs individuals in the right places to detect security breaches. Most development teams today will need experts in:

Networking

Database management

Application design and development

Mobile technology

Cyber forensics

Compliance

Each application needs such a team and the team should meet regularly to discuss application-specific security requirements and threats. In addition, it’s important to review various threat scenarios and determine what you might do when a breach does occur. By being prepared, you make it more likely that you’ll detect the breach early—possibly before someone in management comes thundering into your office asking for an explanation.

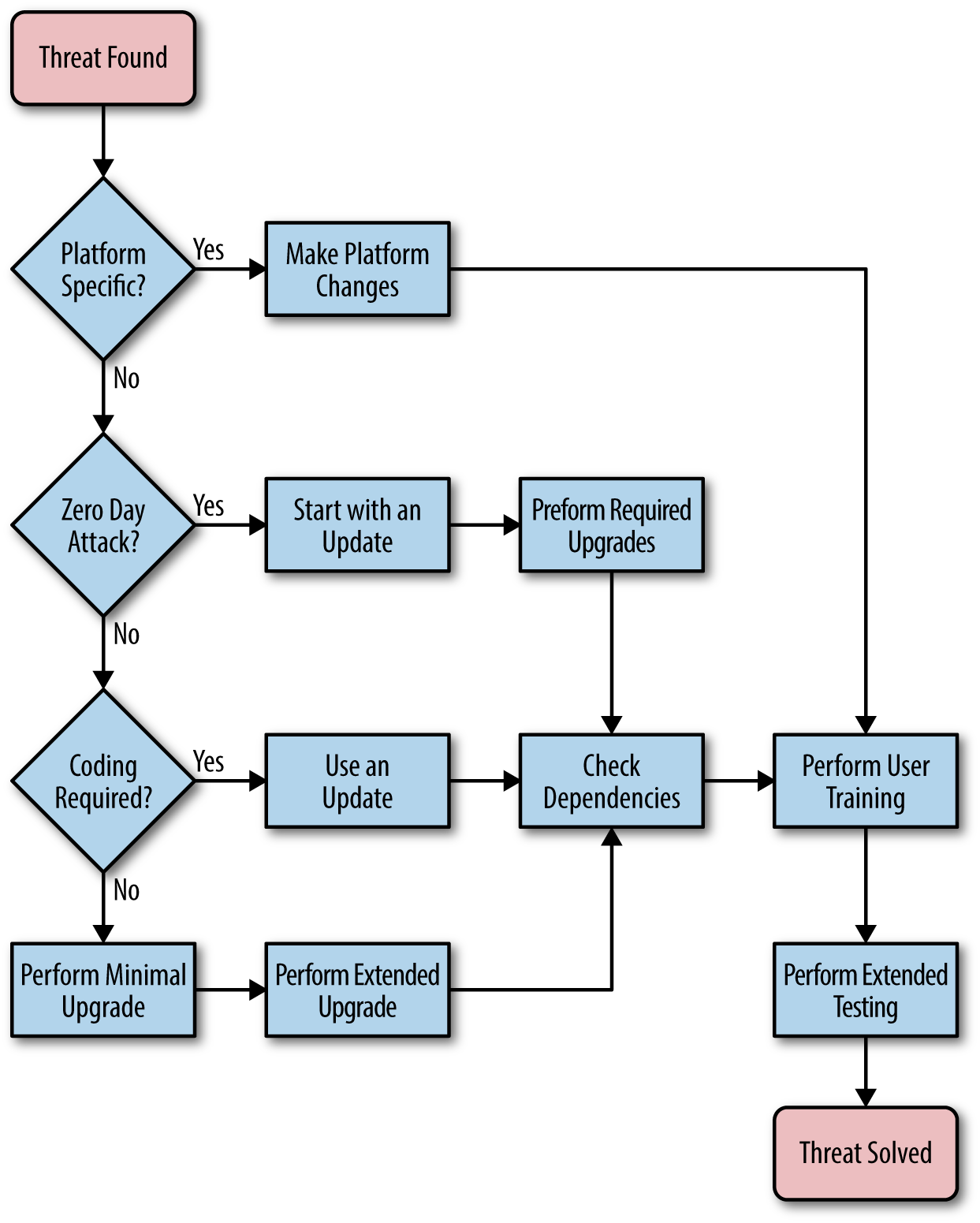

When a security breach does occur, whatever team your organization has in place must be ready to take charge and work through the remediation process. The organization, as a whole, needs to understand that not fixing the security breach and restoring the system as quickly as possible to its pre-breach state could cause the organization to fail. In other words, even if you’re a great employee, you may well be looking for a new job.

The person in charge of security may ask the development team to help locate the attacker. Security information and event management (SIEM) software can help review logs that point to the source of the problem. Of course, this assumes your application actually creates appropriate logs. Part of the remediation process is to build logging and tracking functionality into the application in the first place. Without this information, trying to find the culprit so that your organization can stop the attack is often a lost cause.

Your procedures should include a strategy for checking for updates or patches for each component used by your application. Maintaining good application documentation is a must if you want to achieve this goal. It’s too late to create a list of external resources at the time of a breach; you must have the list in hand before the breach occurs. Of course, the development team will need to test any updates that the application requires in order to ensure that the breach won’t occur again. Finally, you need to ensure that the data has remained safe throughout the process and perform any data restoration your application requires.

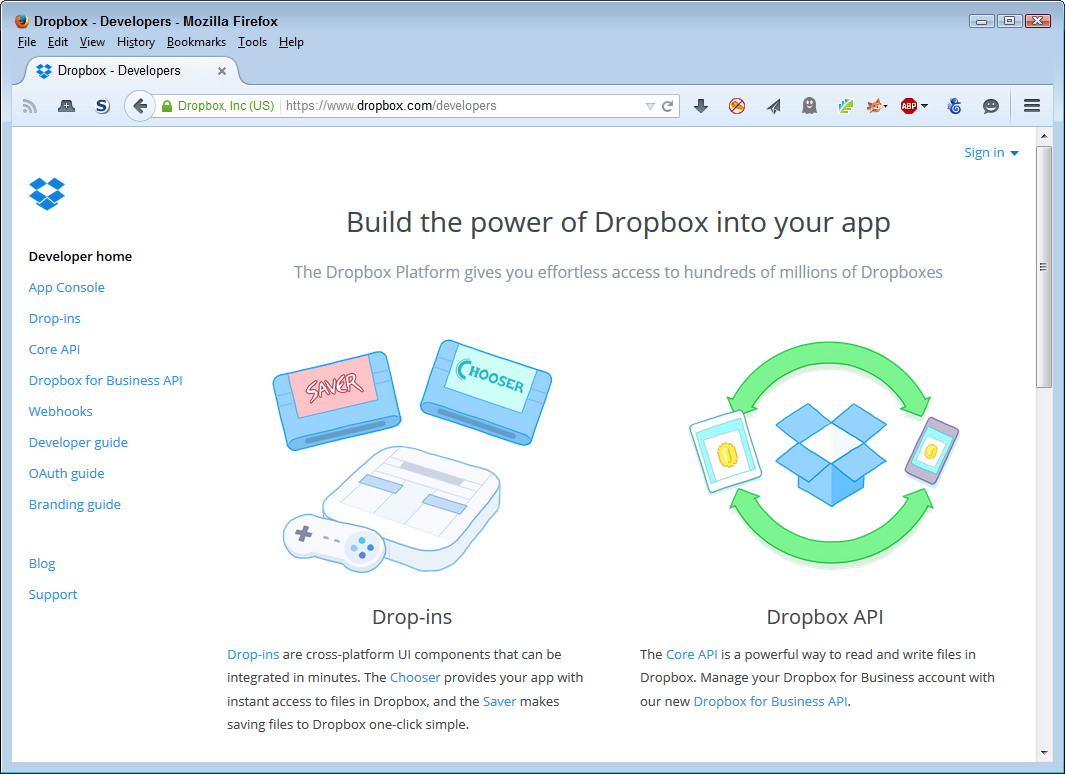

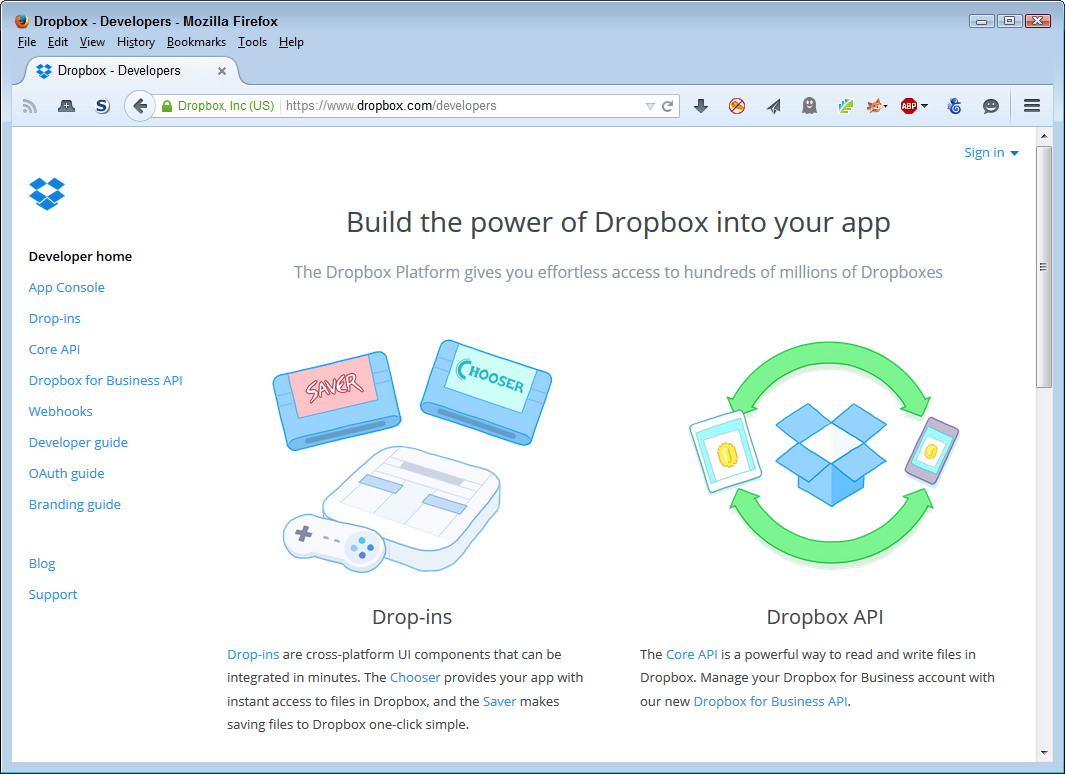

Cloud storage is a necessary evil in a world where employees demand access to data everywhere using any kind of device that happens to be handy. Users have all sorts of cloud storage solutions available, but one of the most popular now is Dropbox, which had amassed over 300 million users by the end of 2014. Dropbox (and most other cloud storage entities) have a checkered security history. For example, in 2011, Dropbox experienced a bug where anyone could access any account using any password for a period of four hours (see the article at InformationWeek). Of course, all these vendors will tell you that your application data is safe now that it has improved security. It isn’t a matter of if, but when, a hacker will find a way inside the cloud storage service or the service itself will drop the ball yet again.

A major problem with most cloud storage is that it’s public in nature. For example, Dropbox for Business sounds like a great idea and it does provide additional security features, but the service is still public. A business can’t host the service within its own private cloud.

In addition, most cloud services advertise that they encrypt the data on their servers, which is likely true. However, the service provider usually holds the encryption keys under the pretense of having to allow authorities with the proper warrants access to your data. Because you don’t hold the keys to your encrypted data, you can’t control access to it and the encryption is less useful than you might think.

Security of web applications is a big deal because most, if not all, applications will eventually have a web application basis. Users want their applications available everywhere and the browser is just about the only means of providing that sort of functionality on so many platforms in an efficient manner. In short, you have to think about the cloud storage issues from the outset. You have a number of options for dealing with cloud storage as part of your application strategy:

Most organizations today don’t have the time or resources needed to build applications completely from scratch. In addition, the costs of maintaining such an application would be enormous. In order to keep costs under control, organizations typically rely on third-party code in various forms. The code performs common tasks and developers use it to create applications in a Lego-like manner. However, third-party code doesn’t come without security challenges. Effectively you’re depending on someone else to write application code that not only works well and performs all the tasks you need, but does so securely. The following sections describe some of the issues surrounding the use of external code and resources.

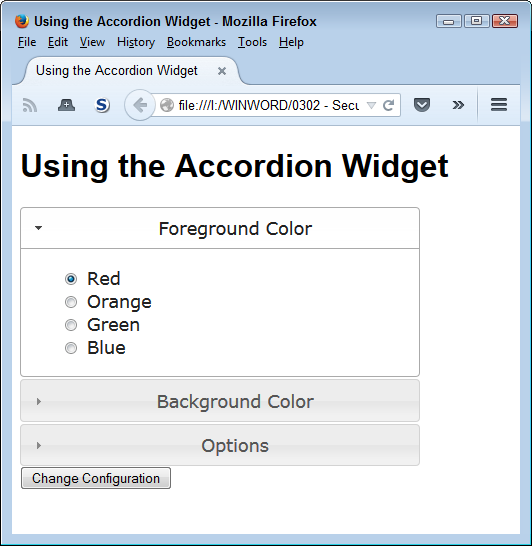

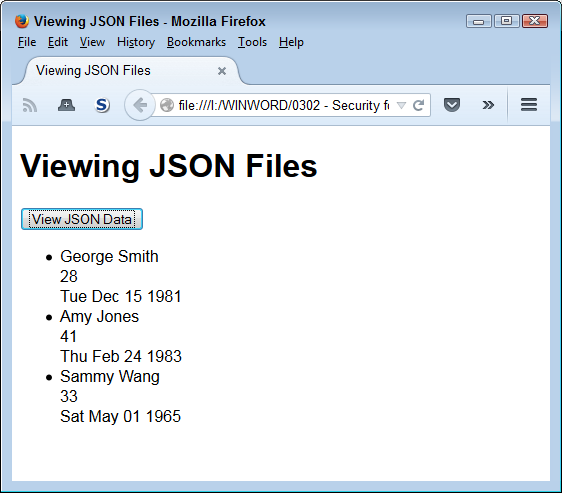

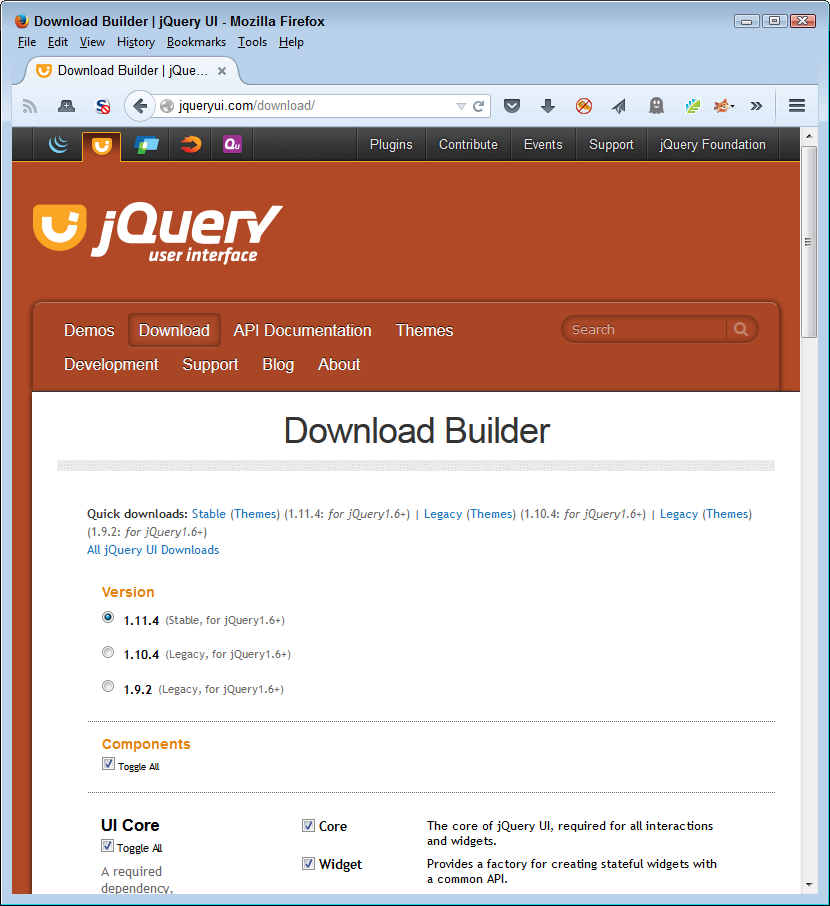

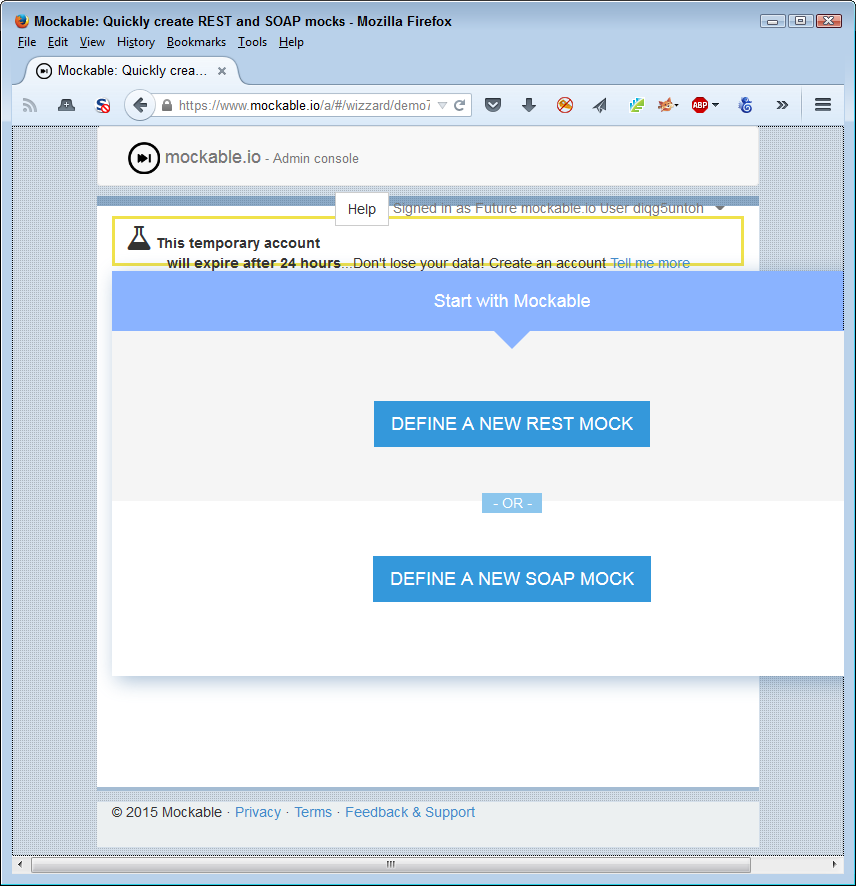

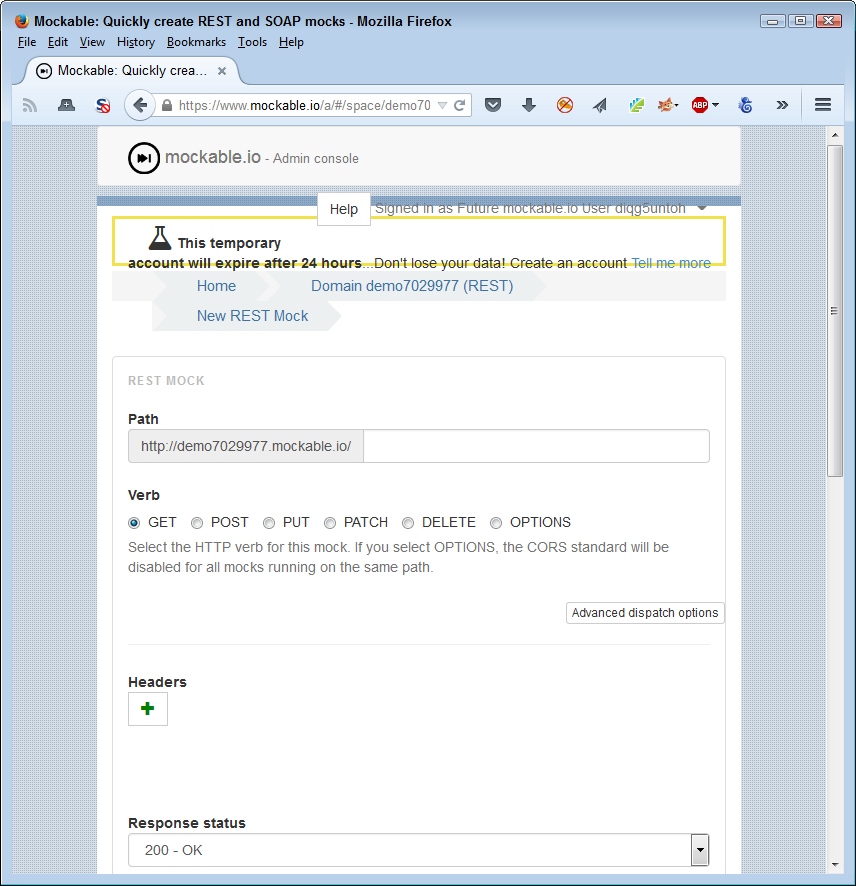

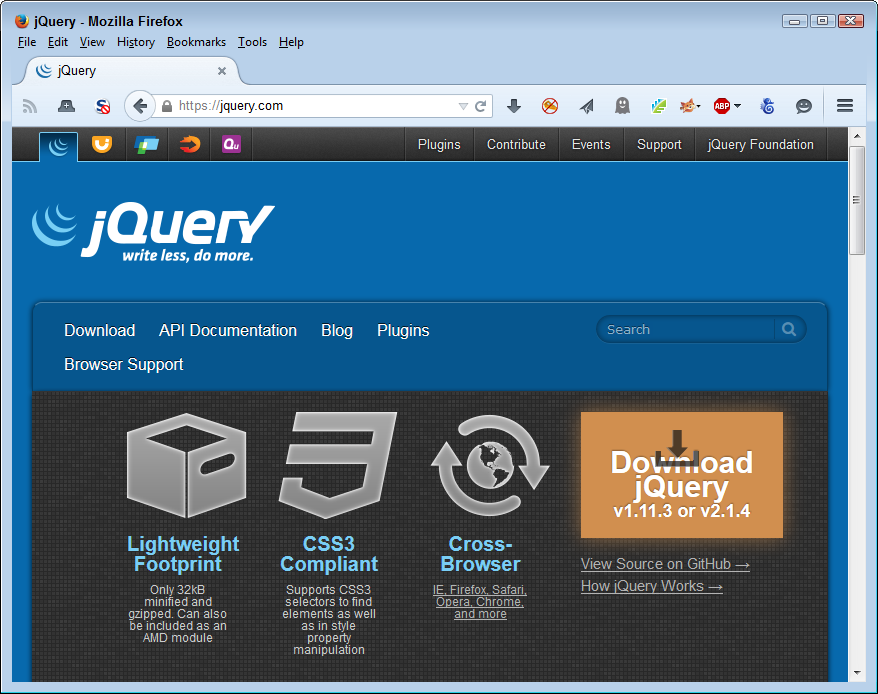

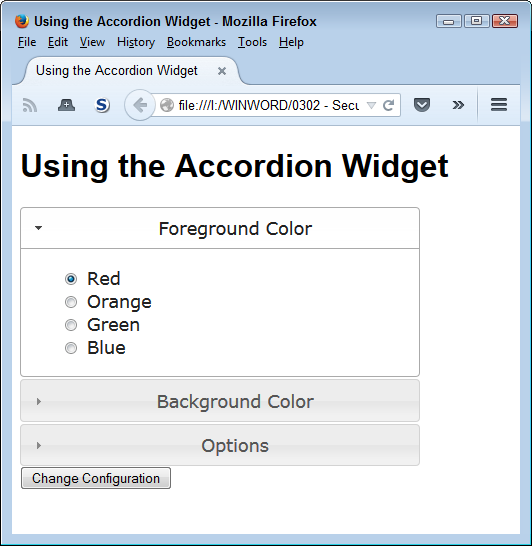

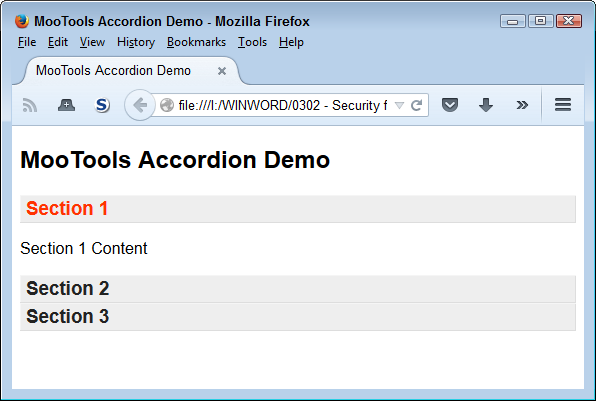

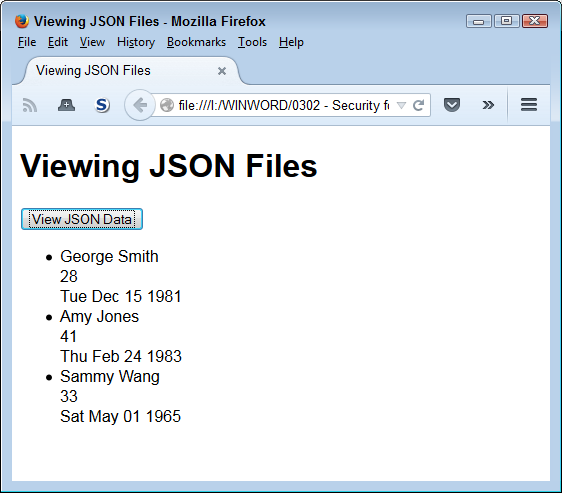

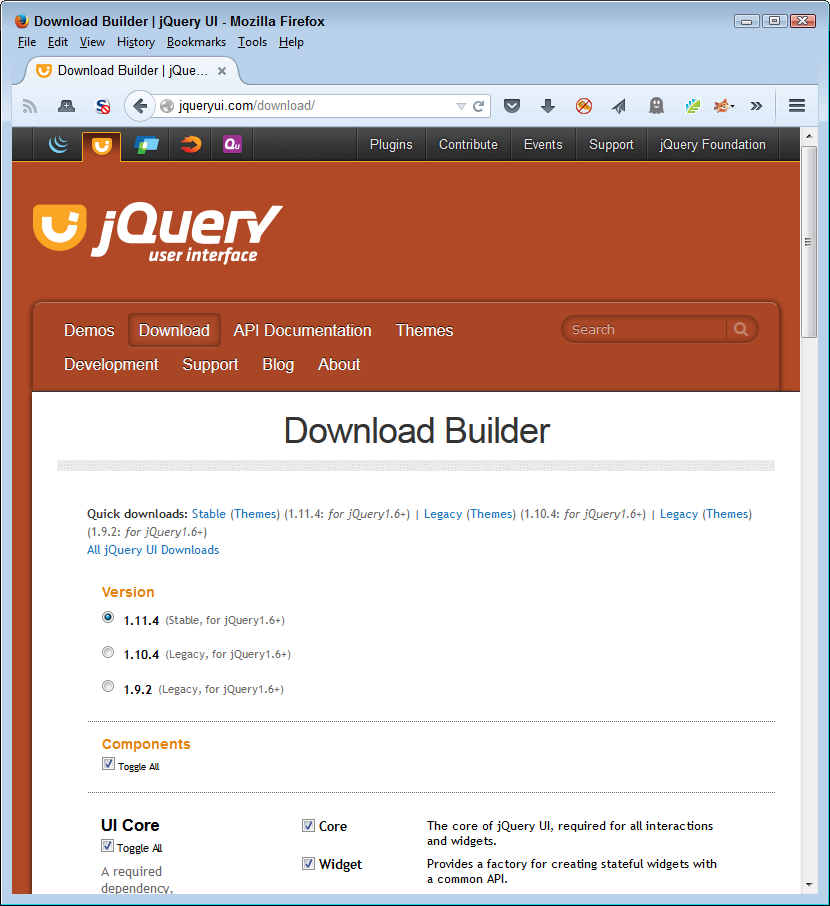

A library is any code that you add into your application. Many people define libraries more broadly, but for this book, the essentials are that libraries contain code and that they become part of your application as you put the application in use. One commonly used library is jQuery. It provides a wealth of functionality for performing common tasks in an application. The interesting thing about jQuery is that you find the terms library and API used interchangeably, as shown in Figure 1-2.

Looking at the jQuery site also tells you about optimal library configurations. In fact, the way in which jQuery presents itself is a good model for any library that you want to use. The library is fully documented and you can find multiple examples of each library call (to ensure you can find an example that is at least close to what you want to do). More importantly, the examples are live, so you can actually see the code in action using the same browsers that you plan to use for your own application.

Like any other piece of software, jQuery has its faults too. As the book progresses, you’re introduced to other libraries and to more details about each one so that you can start to see how features and security go hand in hand. Because jQuery is such a large, complex library, it has a lot to offer, but there is also more attack surface for hackers to exploit.

When working with libraries, the main focus of your security efforts is your application because you download the code used for the application from the host server. Library code is executed in-process, so you need to know that you can trust the source from which you get library code. Chapter 6 discusses the intricacies of using libraries as part of an application development strategy.

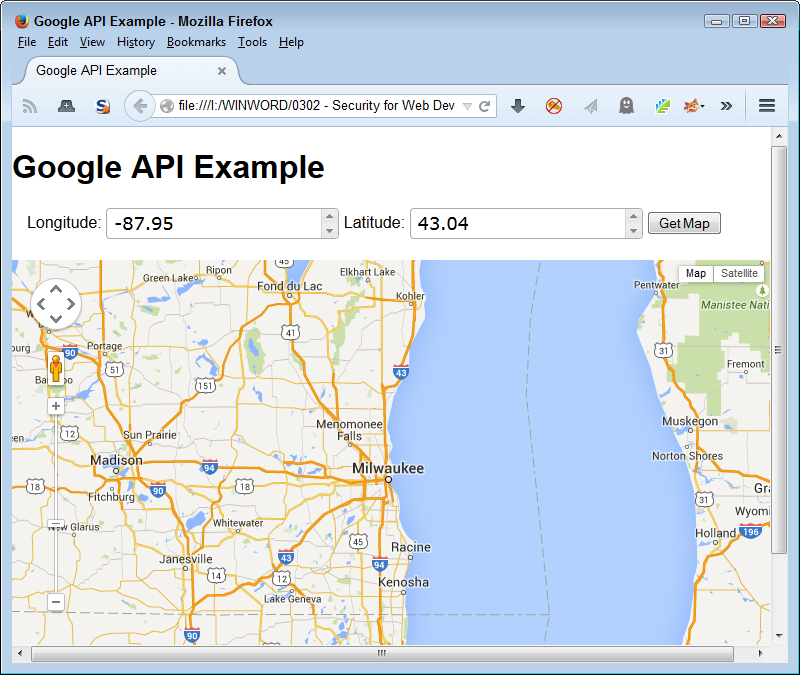

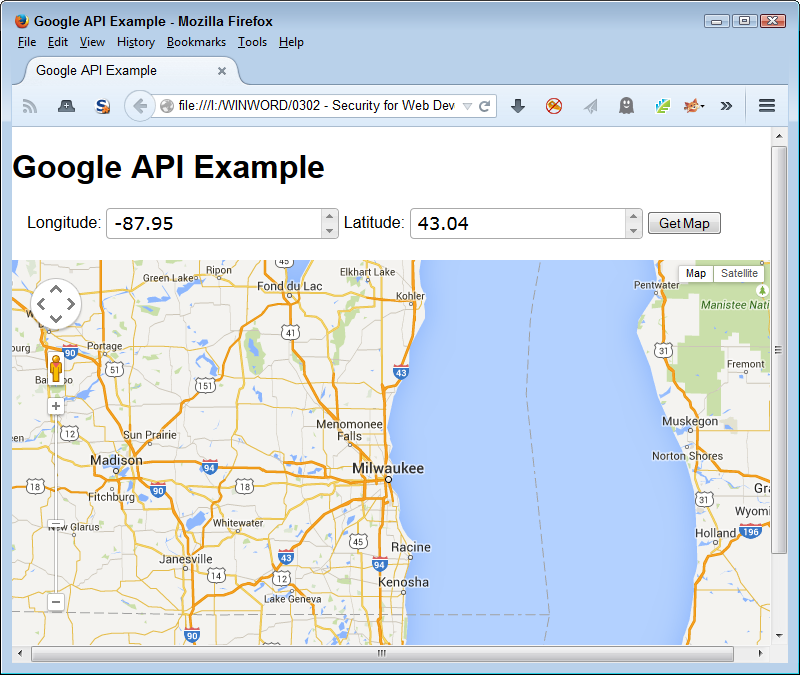

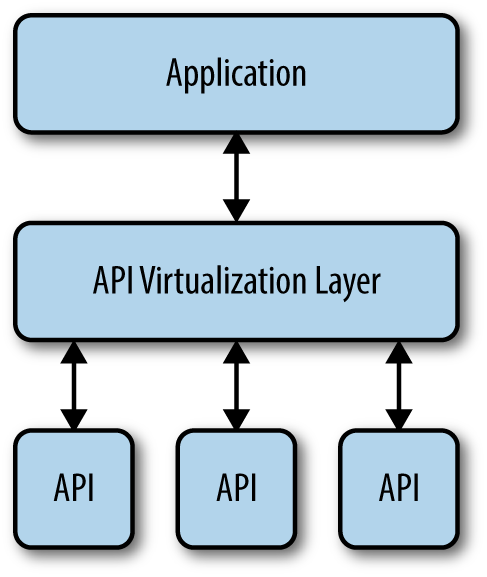

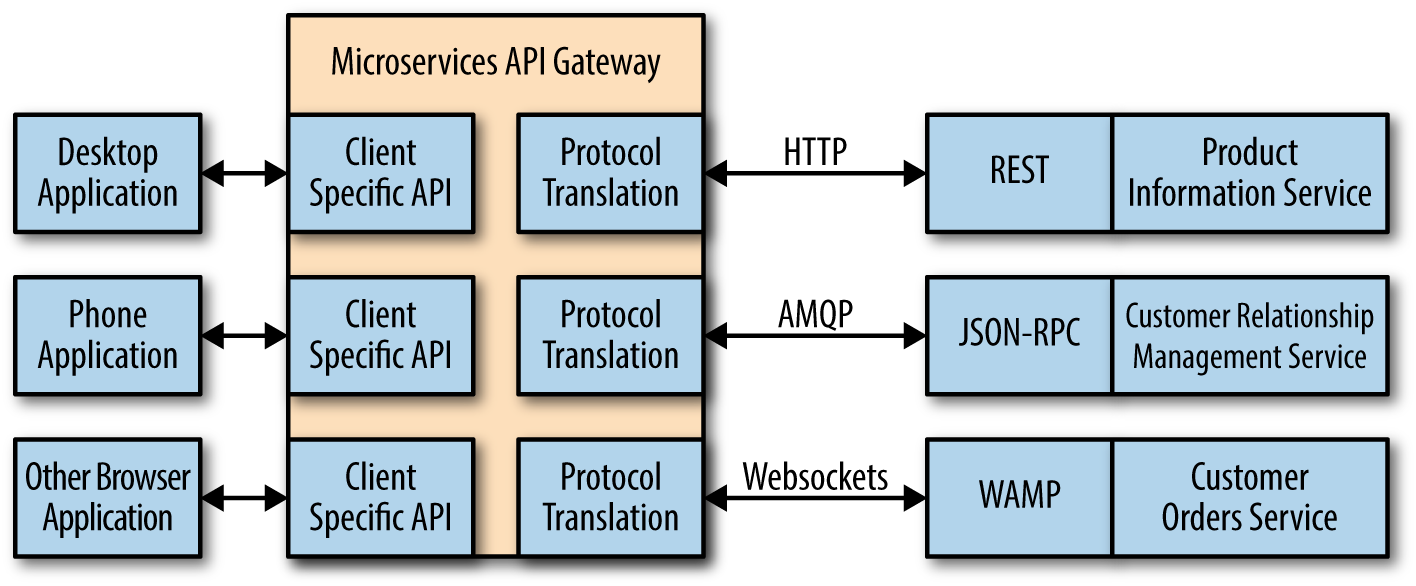

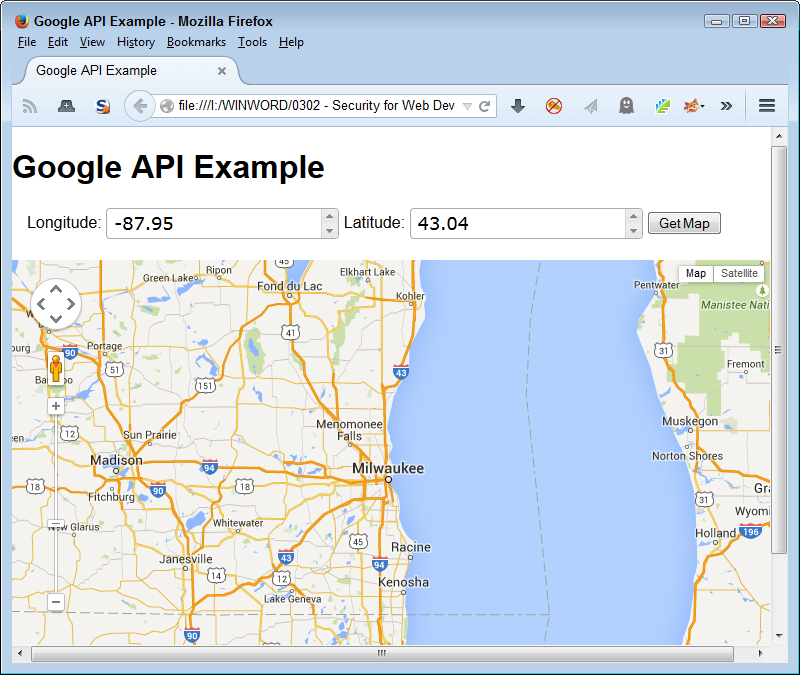

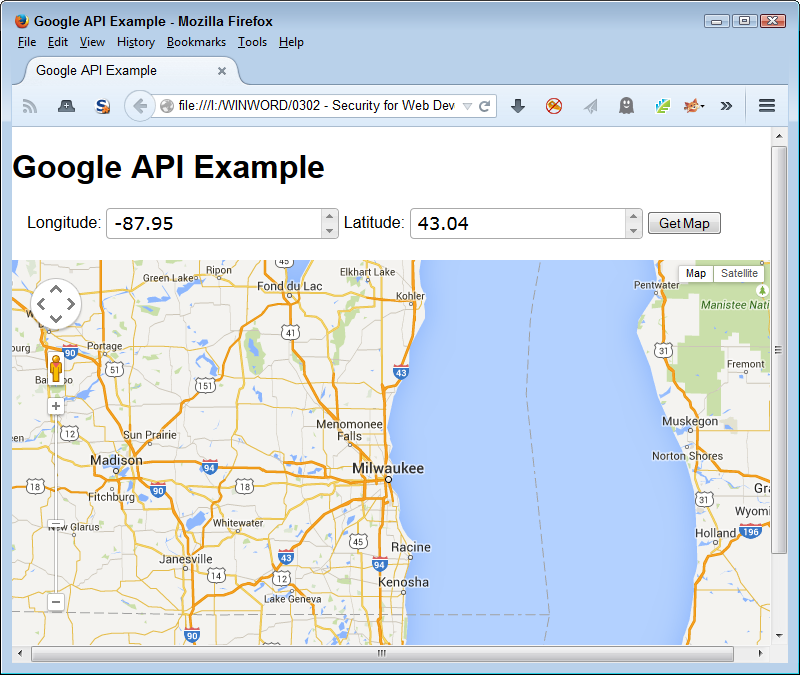

An application programming interface (API) is any code you can call as an out-of-process service. You send a request to the API and the API responds with some resource that you request. The resource is normally data of some type, but APIs perform other sorts of tasks too. The idea is that the code resides on another system and that it doesn’t become part of your application. Because APIs work with a request/response setup, they tend to offer broader platform support than libraries, but they also work slower than libraries do because the code isn’t local to the system using it.

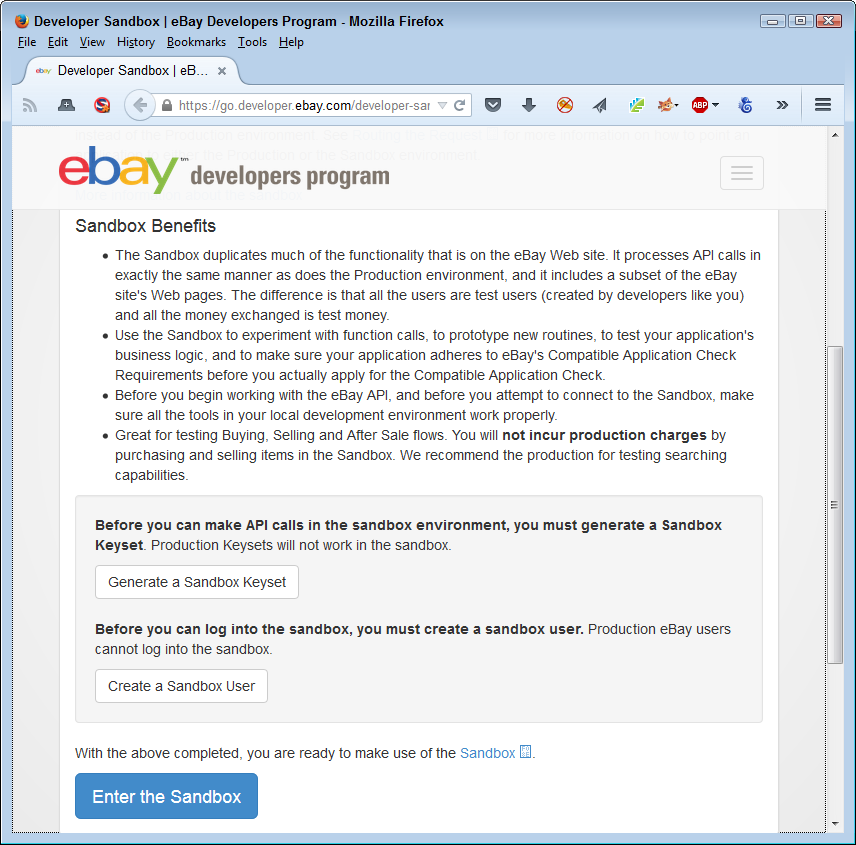

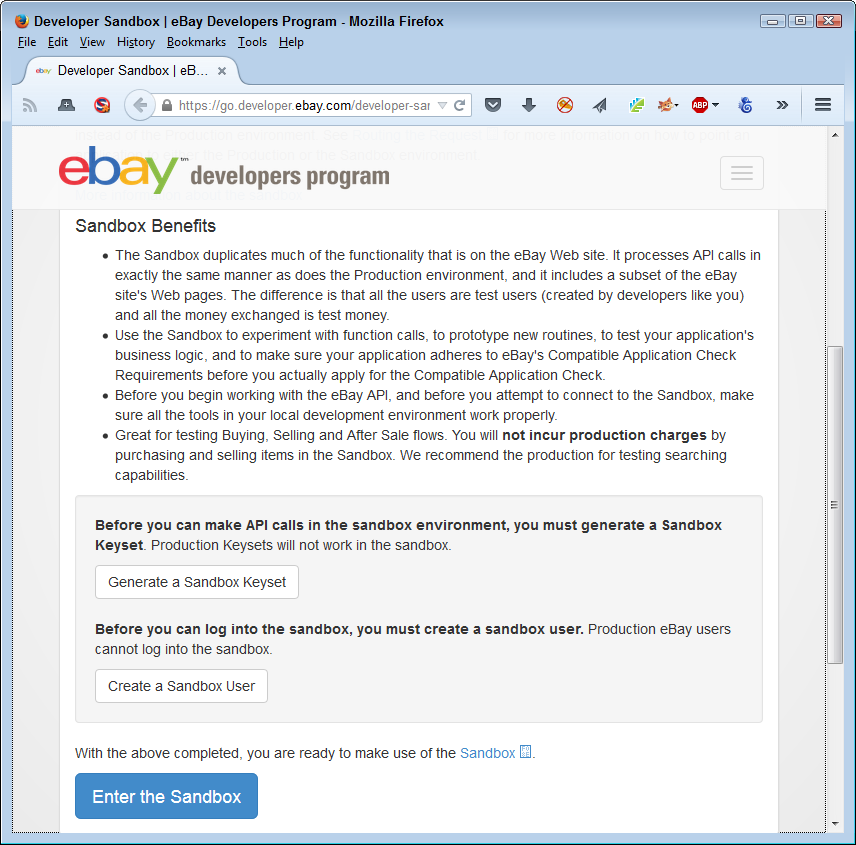

A good example of APIs is the services that Amazon offers for various developer needs. Figure 1-3 shows just a few of these services. You must sign up for each API you want to use and Amazon provides you with a special key to use in most cases. Because you’re interacting with Amazon’s servers and not simply downloading code to your own system, the security rules are different when using an API.

Each API tends to have a life of its own and relies on different approaches to issues such as managing data. Consequently, you can’t make any assumption as to the security of one API when compared to another, even when both APIs come from the same host.

APIs also rely on an exchange of information. Any information exchange requires additional security because part of your data invariably ends up on the host system. You need to know that the host provides the means for properly securing the data you transmit as part of a request. Chapter 7 discusses how to work with APIs safely when using them as part of an application development strategy.

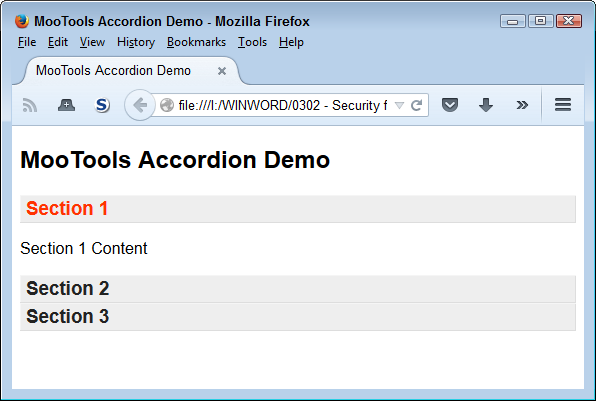

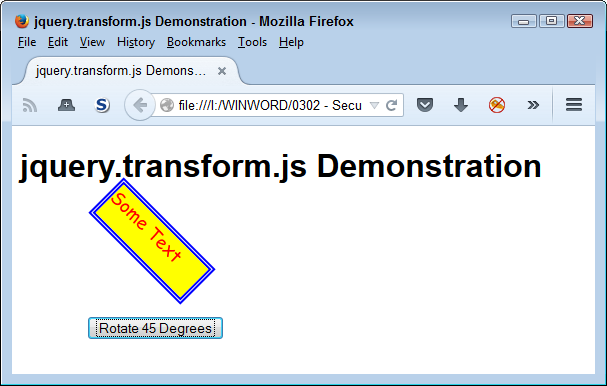

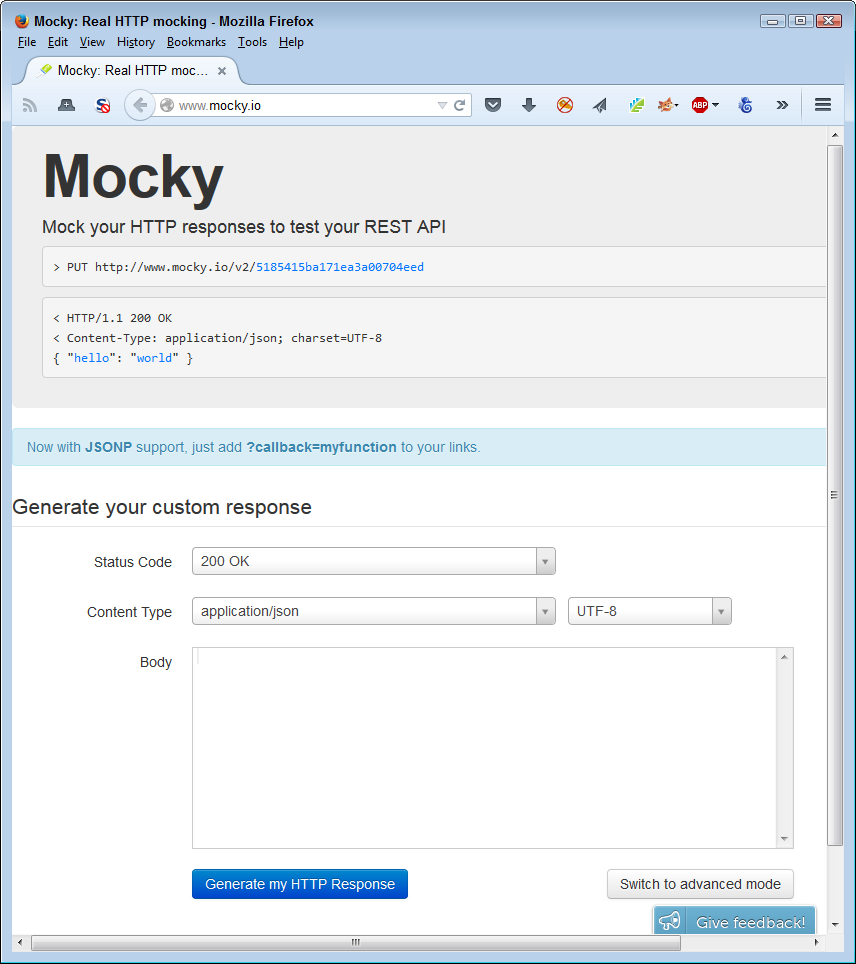

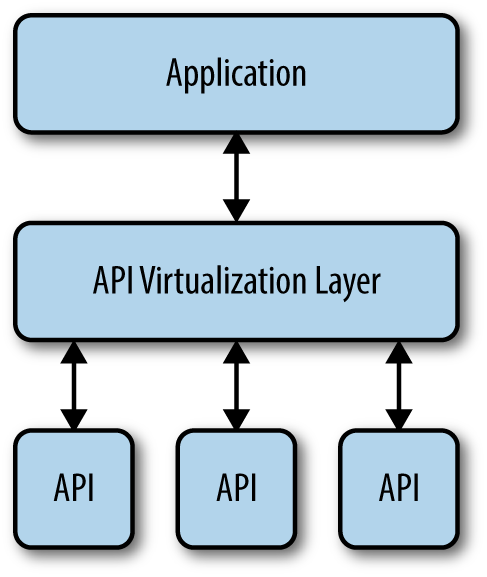

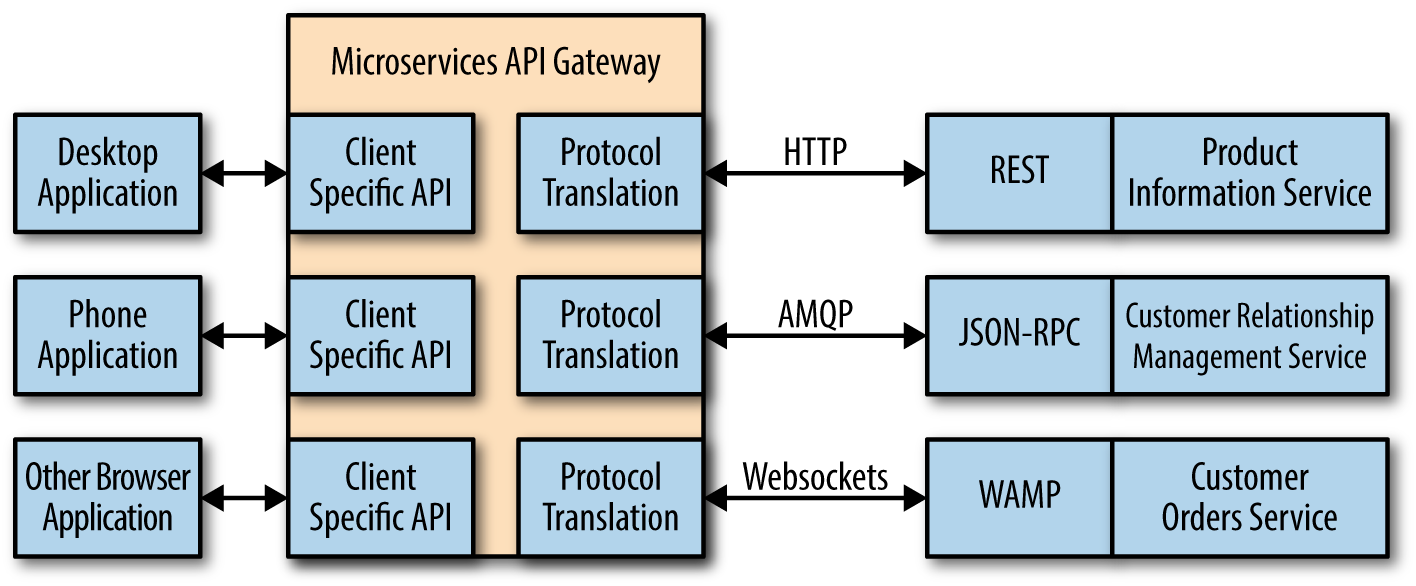

Like an API, microservices execute on a host system. You make a request and the microservice responds with some sort of resource (usually data). However, microservices differ a great deal from APIs. The emphasis is on small tasks with microservices—a typical microservice performs one task well. In addition, microservices tend to focus heavily on platform independence. The idea is to provide a service that can interact with any platform of any size and of any capability. The difference in emphasis between APIs and microservices greatly affects the security landscape. For example, APIs tend to be more security conscious because the host can make more assumptions about the requesting platform and there is more to lose should something go wrong.

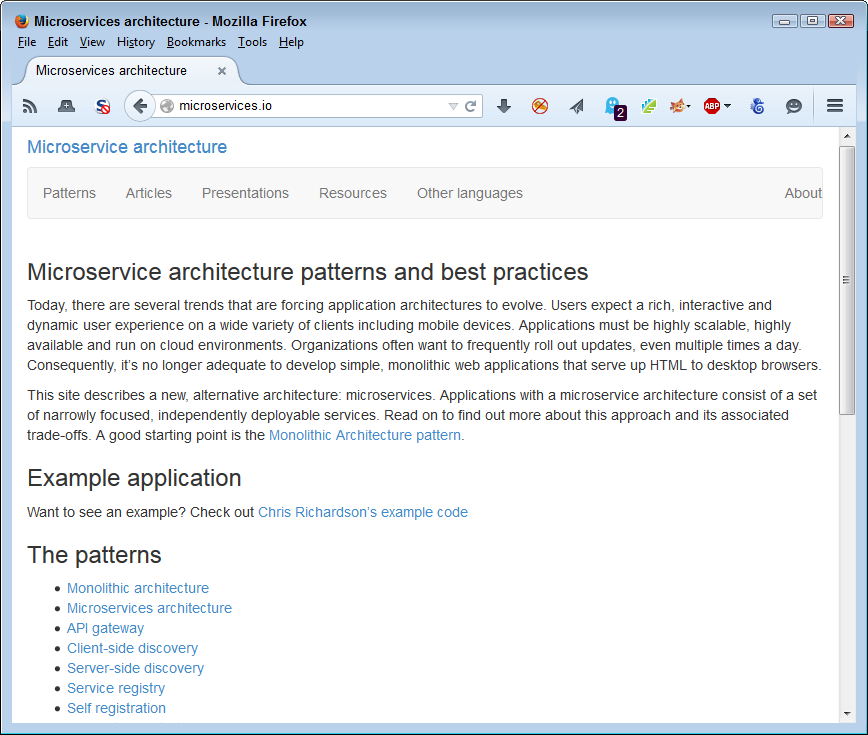

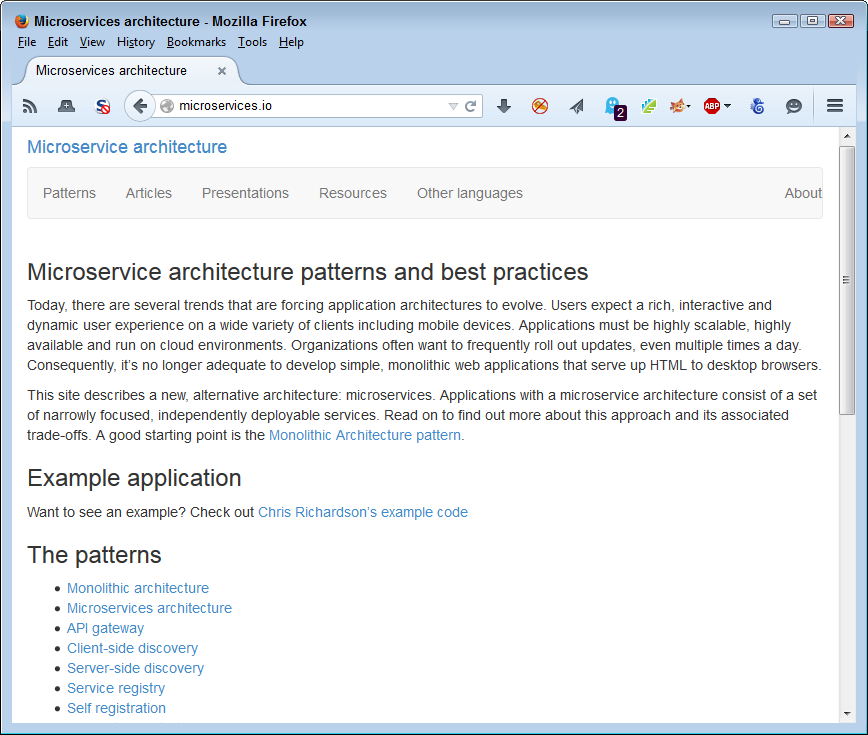

Current microservice offerings also tend to be homegrown because the technology is new. Look for some of the current API sites to begin offering microservices once the technology has grown. In the meantime, it pays to review precisely how microservices differ by looking at sites such as Microservice Architecture. The site provides example applications and a discussion of the various patterns in use for online code at the moment, as shown in Figure 1-4.

When working with microservices, you need to ensure that the host is reliable and that the single task the microservice performs is clearly defined. It’s also important to consider how the microservice interacts with any data you supply and not to assume that every microservice interacts with the data in the same fashion (even when the microservices exist on the same host). The use of microservices does mean efficiency and the ability to work with a broader range of platforms, but you also need to be aware of the requirement for additional security checks. Chapter 8 discusses how to use microservices safely as part of an application development strategy.

External data takes all sorts of forms. Any form of external data is suspect because someone could tamper with it in the mere act of accessing the data. However, it’s helpful to categorize data by its visibility when thinking about security requirements.

You can normally consider private data sources relatively secure. You still need to check the data for potential harmful elements (such as scripts encrypted within database fields). However, for the most part, the data source isn’t purposely trying to cause problems. Here are the most common sources of information storage as part of external private data sources:

Data on hosts in your own organization

Data on partner hosts

Calculated sources created by applications running on servers

Imported data from sensors or other sources supported by the organization

Paid data sources are also relatively secure. Anyone who provides access to paid data wants to maintain your relationship and reputation is everything in this area. As with local and private sources, you need to verify the data is free from corruption or potential threats, such as scripts. However, because the data also travels through a public network, you need to check for data manipulation and other potential problems from causes such as man-in-the-middle attacks.

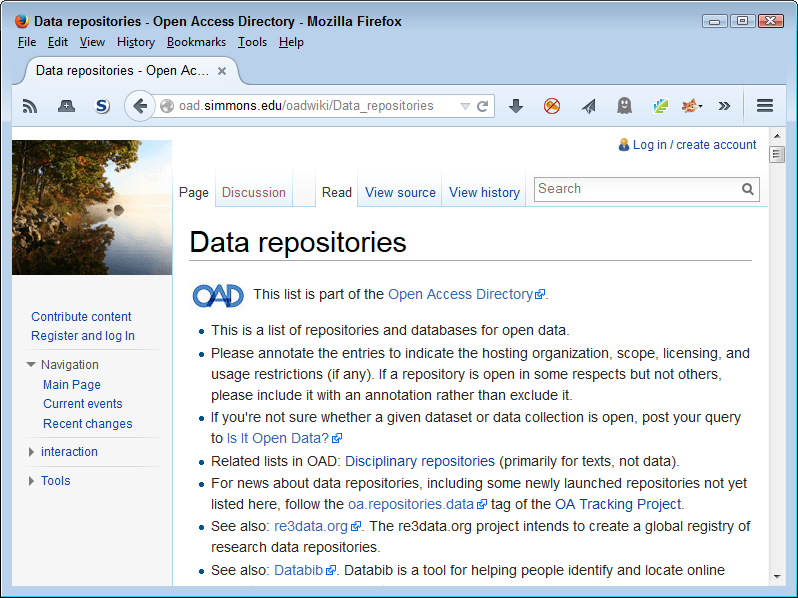

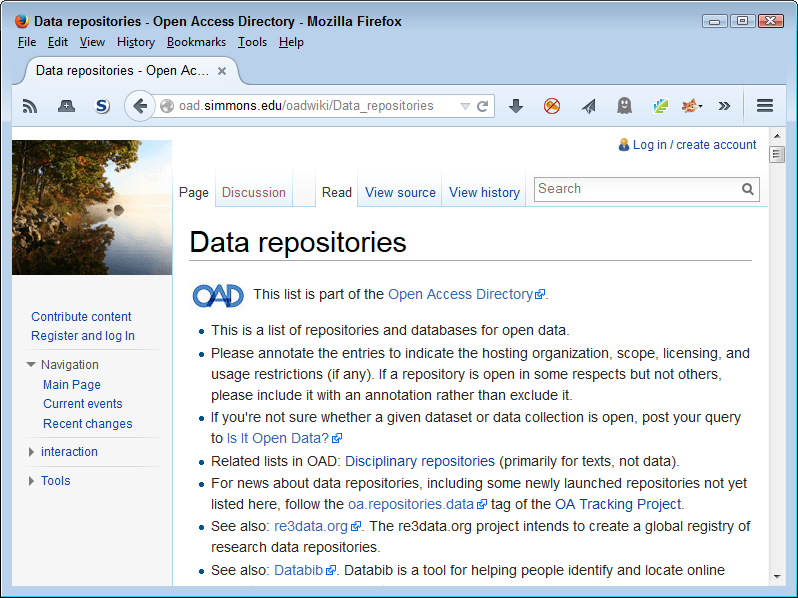

There are many interesting repositories online that you could find helpful when creating an application. Rather than generate the data yourself or rely on a paid source, you can often find a free source of the data. Sites such as the Registry of Research Data Repositories offer APIs now so that you can more accurately search for just the right data repository. In this case, you can find the API documentation at http://service.re3data.org/api/doc.

Data repositories can be problematic and the more public the repository, the more problematic it becomes. The use to which you put a data repository does make a difference, but ensuring you’re actually getting data and not something else in disguise is essential. In many cases, you can download the data and scan it before you use it. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) siteshown in Figure 1-5 provides the means to sift through its data repository to find precisely the data you require and then to download just that dataset, reducing the risk that you’ll get something you really didn’t want.

There are many kinds of data repositories and many ways to access the data they contain. The technique you use depends on the data repository interface and the requirements of your application. Make sure you read about data repositories in Chapter 3. Chapter 6, Chapter 7, and Chapter 8 all discuss the use of external data as it applies to libraries, APIs, and microservices. Each environment has different requirements, so it’s important to understand precisely how your code affects the access method and therefore the security needed to use the data without harm.

The vast majority of this chapter discusses protection of your resources or your use of data and resources provided by someone else. Enterprises don’t exist in a vacuum. When you create a data source, library, API, microservice, or other resource that someone else can use, the third party often requests access. As soon as you allow access to the resource by this third party, you open your network up to potential security threats that you might not ever imagine. The business partner or other entity is likely quite reliable and doesn’t intend to cause problems. However, their virus becomes your virus. Any security threat they face becomes a security threat you face as well. If you have enough third parties using your resources, the chances are high that at least one of them has a security issue that could end up causing you problems as well.

Of course, before you can do anything, you need to ensure that your outside offering is as good as you think it is. Ensuring the safety of applications you support is essential. As a supplier of resources, you suddenly become a single point of failure for multiple outside entities. Keeping the environment secure means:

Testing all resources regularly to ensure they remain viable

Providing useful resource documentation

Ensuring third-party developers abide by the rules (by doing things like building security requirements into the procurement language)

Performing security testing as needed

Keeping up with potential threats to your resource

Updating host resources to avoid known vulnerabilities

Developers who offer their resources for outside use have other issues to consider as well, but these issues are common enough that they’re a given for any outside access scenario. In addition, you must expect third parties to test the resources to ensure they act as advertised. For example, when offering a library, API, or microservice, you must expect that third parties will perform input and output testing and not simply take your word for it that the resource will behave as expected.

Once you get past the initial phase of offering a resource for third-party use, you must maintain the resource so applications continue to rely upon it. In addition, it’s important to assume you face certain threats in making a resource offering. Here are some of the things you must consider:

Security won’t work unless you are able to convince the user to embrace it. Any Draconian device developers contrive to enforce security without the user’s blessing will eventually fail because users are adept at finding ways around security. In situations where security truly is complete enough to thwart all but the hardiest user attempts, the user simply refuses to use the application. Long lists of failed applications attest to the fact that you can’t enforce security without some level of user assistance, so it’s best to ensure the user is on board with whatever decisions you make.

Users have two levels of requirements from an application, and security must address both of them. A user needs to have the freedom to perform work-required tasks. When an application fails to meet user needs, it simply fails as an application. User expectations are in addition to needs. Users expect that the application will work on their personal devices in addition to company-supplied devices. Depending on the application, ensuring the application and its security work on the broadest range of platforms creates goodwill, which makes it easier to sell security requirements to the user.

This chapter discusses both needs and expectations as they relate to security. For many developers, the goal of coding is to create an application that works well and meets all the requirements. However, the true goal of coding is to create an environment in which the user can interact with data successfully and securely. The data is the focus of the application, but the user is the means of making data-oriented modifications happen.

Users and developers are often at loggerheads about security because they view applications in significantly different ways. Developers see carefully crafted code that does all sorts of interesting things; users see a means to an end. In fact, the user may not really see the application at all. All the user is concerned about is getting a report or other product put together by a certain deadline. For users, the best applications are invisible. When security gets in the way of making the application invisible, the security becomes a problem that the user wants to circumvent. In short, making both the application and its attendant security as close to invisible as possible is always desirable, and the better you achieve this goal, the more the user will like the application.

Current events really can put developers and users at loggerheads. Events such as the Ashley Madison hack have developers especially worried and less likely to make accommodations. In some cases, a user interface or user experience specialist can mediate a solution between the two groups that works to everyone’s benefit. It pays to think outside the box when it comes to security issues where emotions might run high and good solutions might be less acceptable to one group or another.

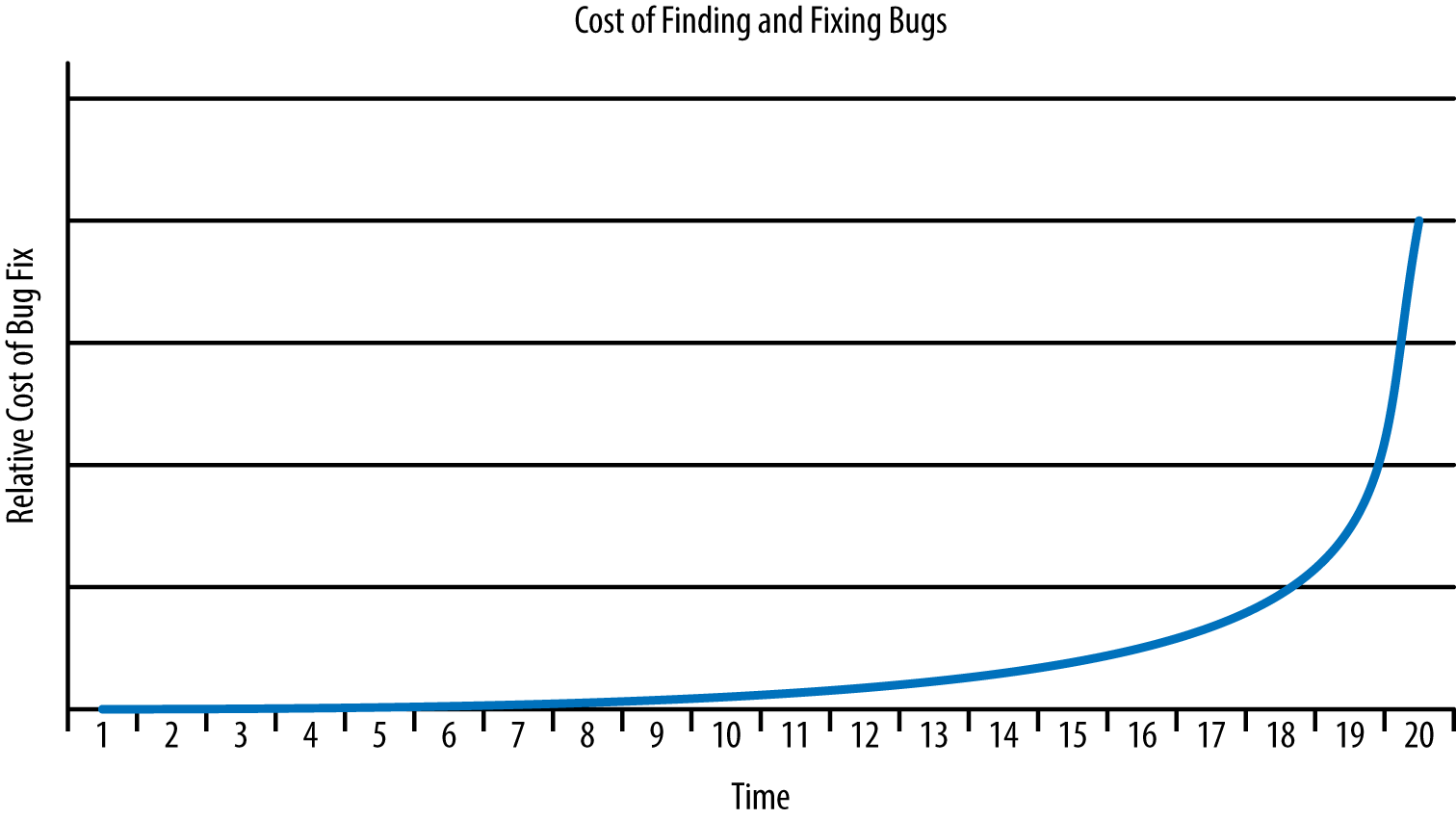

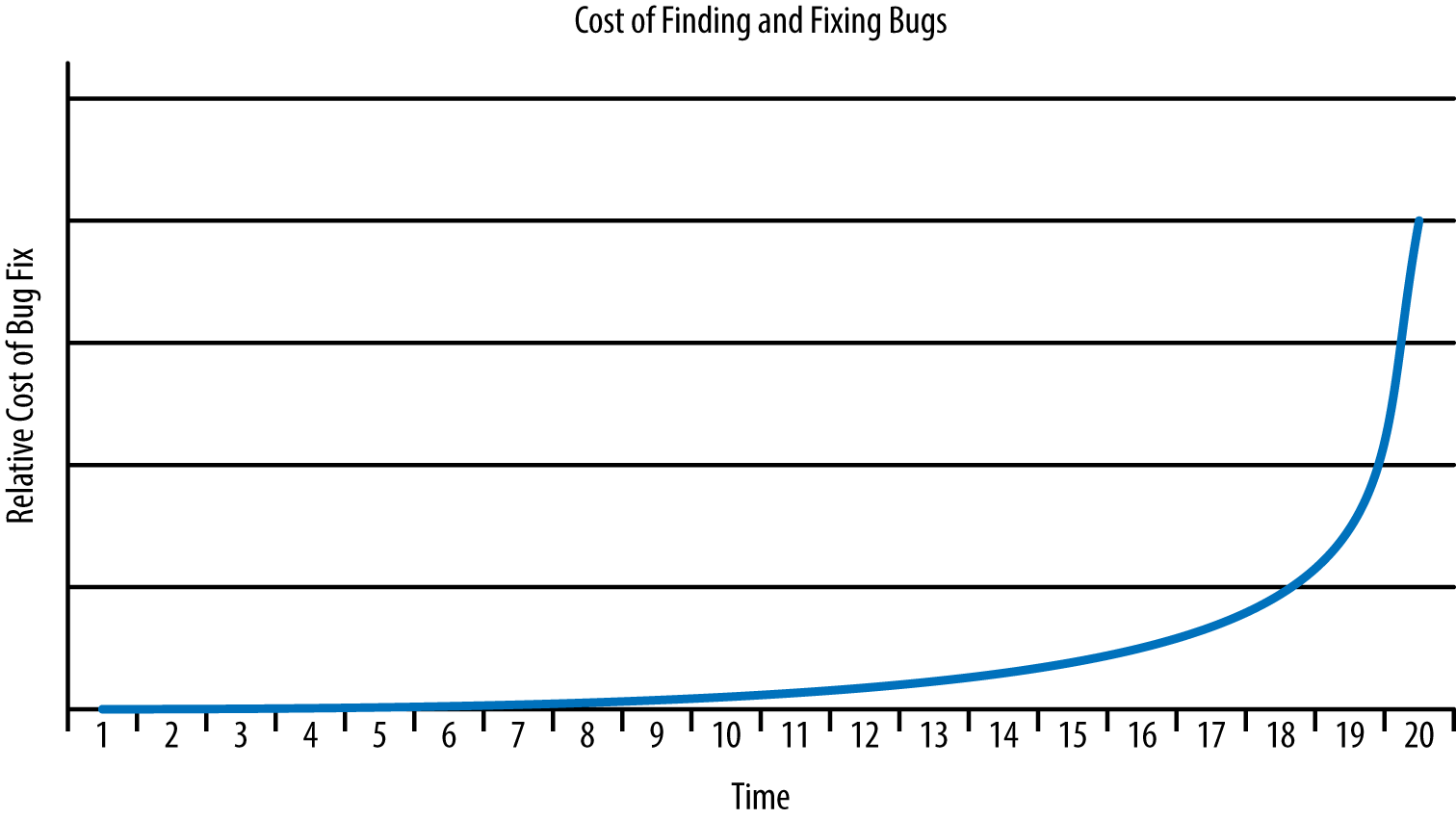

The problem with developers is that they truly don’t think like users. The cool factor of abstract technology just has too big of a pull for any developer to resist. A development team should include at least one user representative (one who truly is representative of typical users in your organization). In addition, you should include users as part of the testing process. Security that doesn’t work, like any other bug in your application, is easier to fix when you find it early in the development process. When security is cumbersome, burdensome, obvious, or just plain annoying, it’s broken, even if it really does protect application data.

Although this book doesn’t discuss the DevOps development method, you should consider employing it as part of your application design and development strategy. DevOps (a portmanteau of development and operations) emphasizes communication, collaboration, integration, automation, and cooperation between the stakeholders of any application development process. You can find a lot of DevOps resources at http://devops.com/. A number of people have attempted to describe DevOps, but one of the clearer dissertations appears in the article at Patrick Debois’ blog. The article is a little old, but it still provides a great overview of what DevOps is, what problems it solves, and how you can employ it at your own organization.

Security is actually a problem that an entire organization has to solve. If you, as a developer, are the only one trying to create a solution, then the solution will almost certainly fail. The user view of the application is essential for bringing users on board with the security strategy you define for an application. However, you must also include:

Management (to ensure organizational goals are met)

Legal (to ensure data protection meets government requirements)

Human resources (to ensure you aren’t stepping on anyone’s toes)

Support (to ensure that any required training takes place)

Every other stakeholder involved in defining business policies that control the management of data

After all, enforcing the data management rules is what security is all about. It’s not just about ensuring that a hacker can’t somehow find the hidden directory used to store the data. Security is the informed protection of data such that users can make responsible changes, but damaging changes are avoided.

Users will bring their own devices from home and they’ll use them to access your application—get used to it. Theoretically, you could create methods of detecting which devices are accessing your application, but the fact is that users will find ways around the detection in many cases. Creating applications that work well in a BYOD environment is harder than working with a precise hardware configuration, but you can achieve good results. The main point is to assume users will rely on their own devices and to create application security with this goal in mind. The following sections describe the issues that you face when working with BYOD and provide you with potential solutions to these issues.

Some organizations have actually embraced BYOD as a means to save money, which means that developers in these organizations have no standardized device to use for testing purposes. The organization simply assumes that the user will have a suitable device to use for both work and pleasure. If your organization is part of this trend, then you not only need to deal with BYOD devices as an alternative to company products, you need to deal with BYOD devices as the only option. It pays to know what sorts of devices your users have so that you have some basis on which to decide the kinds of devices to use for application testing and how to set device criteria for using the application.

The solution that is most likely to make BYOD possible is to create web-based applications for every need. A user could then rely on a smartphone, tablet, notebook, PC, or any other device that has an appropriate browser to access the application. However, web-based applications are also notoriously difficult to secure. Think about the requirements for providing anything other than password security for all of the devices out there. In fact, the password might not even be a password in the true sense of the word—you might find yourself limited to a personal identification number (PIN). The weakest security link for web-based applications in most cases is the mobile device. In order to make mobile devices more secure, you need to consider performing these steps:

Involve all the stakeholders for an application (including users, CIO, CISO, human resources, and other people outside the development team) in the decision-making process for application features. You need to make this the first step because these individuals will help you create a strategy that focuses on both user and business needs, yet lets you point out the issues surrounding unmet expectations (rather than needs).

Develop a mobile security strategy and put it in writing. The problem with creating agreements during meetings and not formalizing those agreements is that people tend to forget what was agreed upon and it becomes an issue later in the process. Once you do have a formalized strategy, make sure everyone is aware of it and has read it. This is especially important for the developers who are creating the application design.

Ensure that management understands the need to fund the security measures. Most companies today suffer from a lack of resources when it comes to security. If a development team lacks resources to create secure applications, then the applications will have openings that hackers will exploit. The finances for supporting the development effort must come before the development process begins.

Obtain the correct tools for creating secure applications. Your development team requires the proper tools from the outset or it’s not possible to obtain the desired result. In many cases, developers fall short on security goals because they lack the proper tools to implement the security strategy. The tools you commonly require affect these solution areas:

User or system authentication

Data encryption

Mobile device management

Common antivirus protection

Virtual private network (VPN) support (when needed)

Data loss prevention

Host intrusion prevention

Create a partnership with an organization that has strong security expertise (if necessary). In many cases, your organization will lack development staff with the proper skills. Obtaining those skills from another organization that has already successfully deployed a number of web-based applications will save your organization time and effort.

Begin the development effort. Only after you have created a robust support system for your application should you start the development effort. When you follow these steps, you create an environment where security is part of the web application from the beginning, rather than being bolted on later.

A 2014 IDG Research Services report based on surveys of IT and security professionals describes a number of issues surrounding mobile device usage. The top concern (voiced by 75% of the respondents) is data leakage—something the organization tasks developers with preventing through application constraints. Lost or stolen devices comes in at 71%, followed by unsecure network access (56%), malware (53%), and unsecure WiFi (41%).

The knee-jerk reaction to the issues surrounding web-based applications is to use native applications instead. After all, developers understand the technology well and it’s possible to make use of operating system security features to ensure applications protect data as originally anticipated. However, the days of the native application are becoming numbered. Supporting native applications is becoming harder as code becomes more complex. In addition, providing access to your application from a plethora of platforms means that you gain these important benefits:

Improved collaboration among workers

Enhanced customer service

Access to corporation information from any location

Increased productivity

Of course, there are many other benefits to supporting multiple platforms, but this list points out the issue of using native applications. If you really want to use native applications to ensure better security, then you need to create a native application for each platform you want to support, which can become quite an undertaking. For most organizations, it simply isn’t worth the time to create the required applications when viewed from the perspective of enhanced security and improved application control.

Some organizations try to get around the native/web-based application issue using kludges that don’t work well in many cases. For example, using an iOS, Android, or web-based interface for your native application tends to be error prone, and introduces potential security issues. Using a pure web-based application is actually better.

In creating your web-based application, you can go the custom browser route. In some cases, that means writing a native application that actually includes browser functionality. The native application would provide additional features because it’s possible to secure it better, yet having the web-based application available to smartphones with access to less sensitive features keeps users happy. Some languages, such as C#, provide relatively functional custom browser capability right out of the box. However, it’s possible to create a custom browser using just about any application language.

It’s a good idea to discuss the use of smartphone and tablet kill switches with your organization as part of the application development strategy. A kill switch makes it possible to turn a stolen smartphone into a useless piece of junk. According to a USA Today article, the use of kill switches has dramatically reduced smartphone theft in several major cities. A recent PC World article arms you with the information needed to help management understand how kill switches work. In many cases, you must install software to make the kill switch available. Using a kill switch may sound drastic, but it’s better than allowing hackers access to sensitive corporate data.

Besides direct security, the custom browser solution also makes indirect security options easier. Although the control used within an application to create the custom browser likely provides full functionality, the application developer can choose not to implement certain features. For example, you may choose not to allow a user to type URLs or to rely on the history feature to move between pages. The application would still display pages just like any other browser, but the user won’t have the ability to control the session in the same way that a standard browser allows. Having this additional level of control makes it possible to allow access to more sensitive information because the user will be unable to do some of the things that normally result in virus downloads, information disclosure, or contamination of the application environment. Of course, there are exceptions to every rule. If a virus that hooks the browser libraries and functions to steal information is already on the system, it’s possible that the virus will still be able to read the content managed by a custom browser that uses that library.

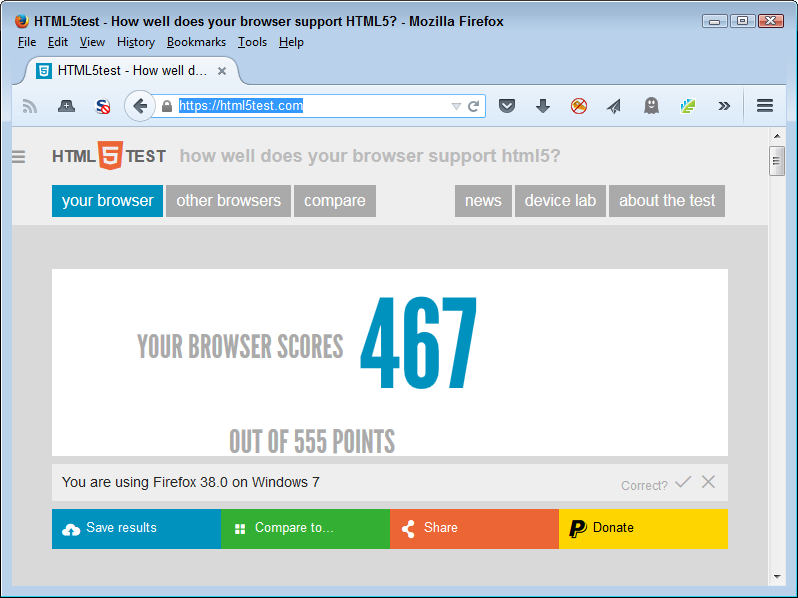

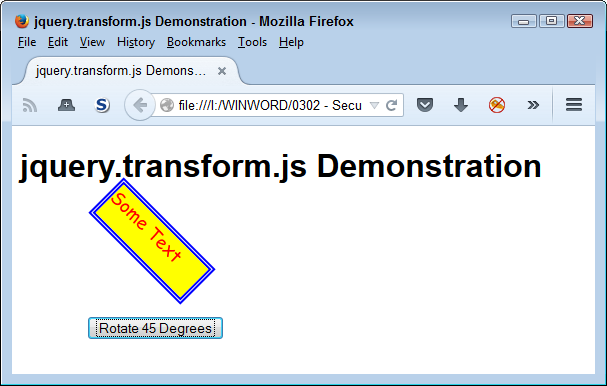

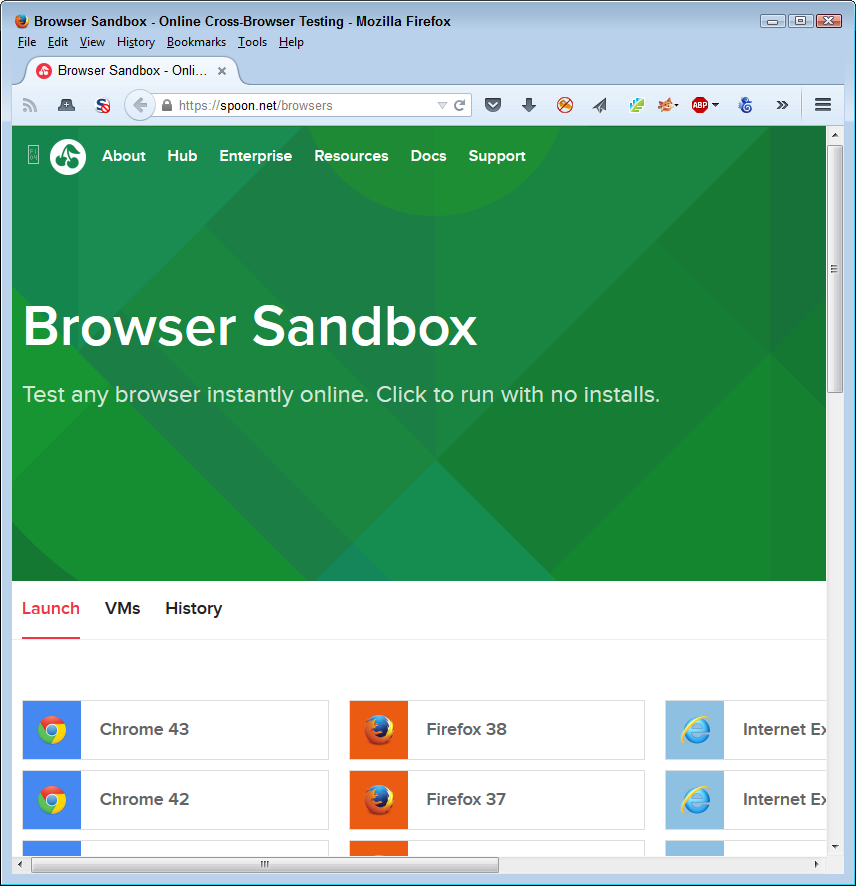

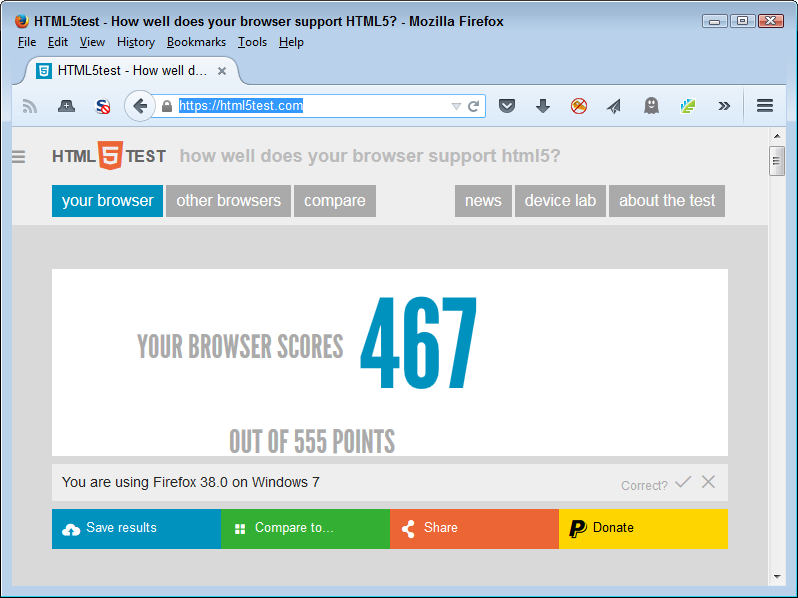

A custom browser environment also affords the developer an opportunity to rely on programming techniques that might not ordinarily work. Developers experience constant problems making third-party libraries, frameworks, APIs, and microservices work properly because not every browser provides the requisite support. For example, in order to determine whether a particular browser actually supports the HTML5 features you want to use, you need to check it using a site such as HTML5test to obtain a listing of potential problem areas like the one shown in Figure 2-1.

The problem with the customer browser solution is that it introduces disparities in user support depending on the device the user chooses to rely upon. When these sorts of disparities exist, the developer normally hears about it. Users will want to access the organization’s most sensitive data on the least secure device available in the most public place. Imagine working on patient records in a Starbucks using a smartphone. The data could end up anywhere, and a data breach will almost certainly occur. In some situations, the developer simply needs to work with everyone from managers on down to come up with a reasonable list of data-handling precautions, which may mean that using the custom browser solution won’t be popular, but it will tend to enforce prudent data management policies.

The BYOD phenomenon means that users will have all sorts of devices to use. Of course, that’s a problem. However, a more significant problem is the fact that users will also have decrepit software on those devices because the older software is simply more comfortable to use. As a result of using this ancient software, your application may appear to have problems, but the issue isn’t the application—it’s a code compatibility problem caused by the really old software. With this in mind, you need to rely on solutions such as HTML5test (introduced in the previous section) to perform checks of a user’s software to ensure it meets the minimum requirements.

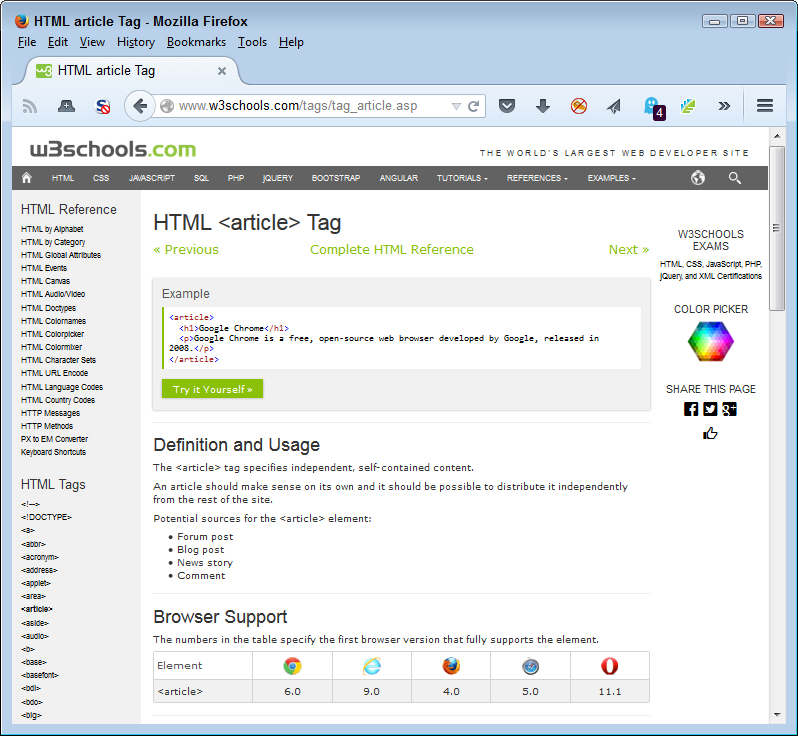

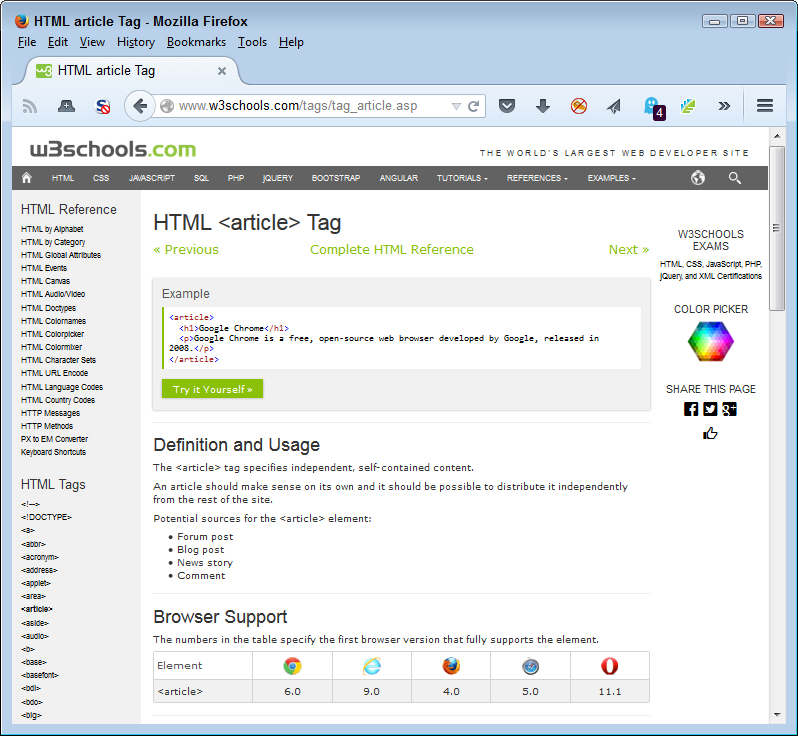

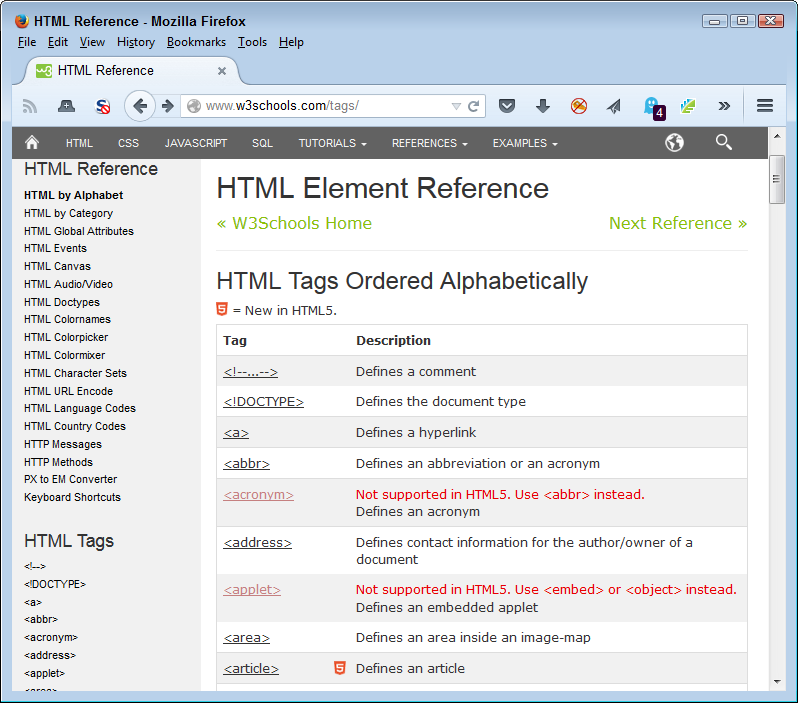

Another method around the problem is to discover potential code compatibility issues as you write the application. For example, Figure 2-2 shows the W3Schools.com site that provides HTML 5 documentation. At the bottom of the page, you see a listing of the browsers that support a particular feature and the version required to support it. By tracking this information as you write your application, you can potentially reduce the code compatibility issues. At the very least, you can tell users which version of a piece of software they must have in order to work with your application when using their own device.

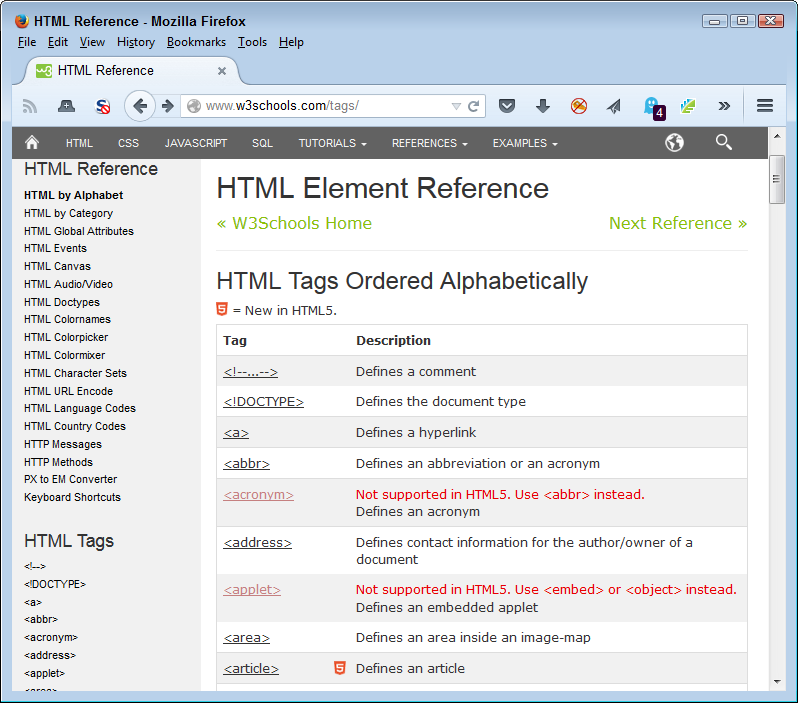

It’s also important to note that some sites also tell you about compatibility issues in a succinct manner. The W3Schools.com site also provides this feature. Notice that the list of HTML tags shown in Figure 2-3 tells you which tags HTML5 supports, and which it doesn’t. Having this information in hand can save considerable time during the coding process because you don’t waste time trying to figure out why a particular feature doesn’t work as it should on a user system.

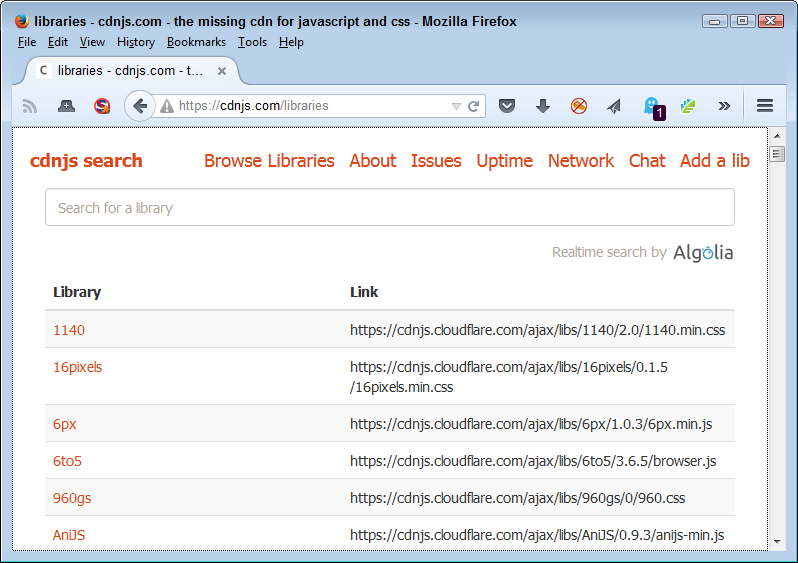

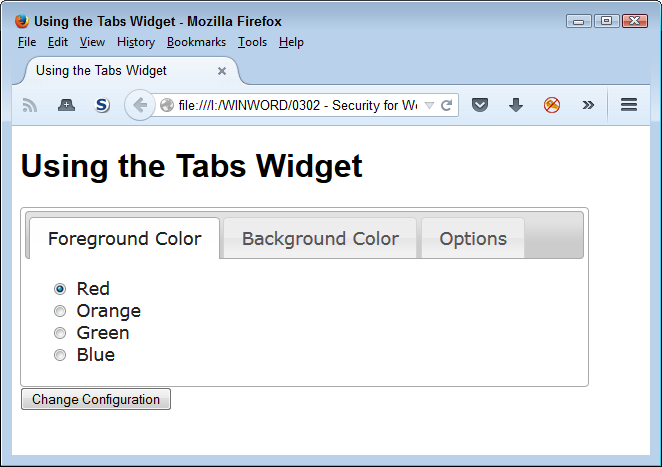

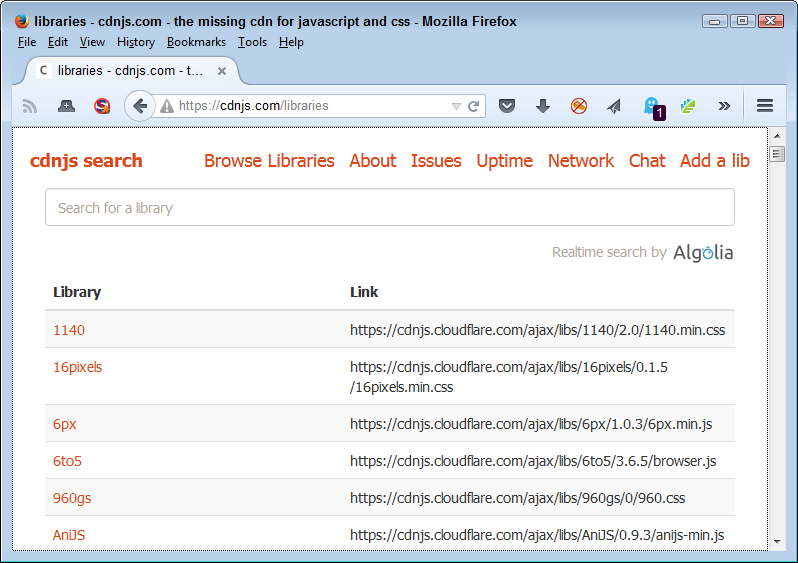

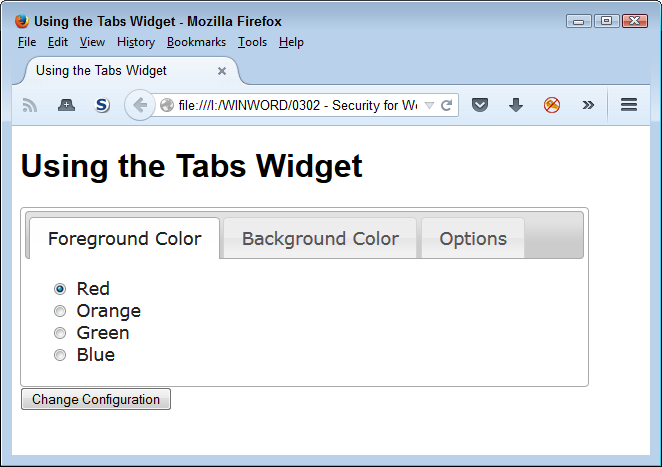

A serious problem that most developers will experience with code compatibility is making HTML5 render properly with older browsers in the first place. Sites such as http://www.w3schools.com/html/html5_browsers.asp provide some answers you can use. For example, it shows how to use html5shiv to make Internet Explorer support HTML5 elements. The cdnjs site contains a large assortment of these helpful JavaScript add-ins. You can find them at https://cdnjs.com/libraries. Figure 2-4 shows just a small listing of the available libraries. Unfortunately, you need to find examples for all of these libraries because the site doesn’t provide much in the way of helpful information. The majority of the library documentation appears on GitHub. For example, you can find the html5shiv.js documentation at https://github.com/afarkas/html5shiv.

You see the abbreviation CDN used all over the place online. A content delivery network is a series of services that provides web content of various sorts. The main purpose of a CDN is to provide high availability and high-speed delivery. It also provides region-appropriate content when needed. Consequently, cdnjs is simply a CDN specifically designed to provide access to JavaScript code and make it available to a large number of developers, similar to the way that the Google CDN performs the task.

Your application will need to be flexible enough to handle all sorts of odd scenarios. One of the more common scenarios today is dealing with nearly continuous device updates. In this case, a user is perfectly happy using your application on a smartphone one day, but can’t get anything to work the next. Common practice is for support to blame the user, but in many situations the user isn’t at fault. At the bottom of the whole problem is that updates often take place without user permission or knowledge. Unfortunately, an update can introduce these sorts of issues:

Code compatibility

Security holes

Lost settings

Unbootable device

Data damage

One of the ways around this issue is to make turning automatic updates off as part of the security policy for an application. Making the updates manually after you have tested the update as part of a rollout process is the best way to ensure that your application will continue to run. Unfortunately, this solution won’t work. Users won’t bring in their devices for testing unless something has already gone wrong. Even if users were willing to part with their devices, you likely won’t have the resources needed to perform the required testing.

An alternative solution is to design applications such that they automatically check for updates during startup. If the version number of a product that the user relies on to work with the application changes, the application can send this information to an administrator as part of a potential solution reminder.

Creating flexible designs is also part of the methodology for handling constant updates. Although a fancy programming trick to aid in keeping data secure looks like a good idea, it probably isn’t. Keep to best practices development strategies, use standard libraries when possible, and keep security at a reasonable level to help ensure the application continues to work after the mystery update occurs on the user’s device. Otherwise, you may find yourself spending considerable time trying to fix the security issue that’s preventing your application from working during those precious weekend hours.

Passwords seem like the straightforward way to identify users. You can change them with relative ease, make them complex enough to reduce the potential for someone else guessing them, and they’re completely portable. However, users see passwords as difficult to use, even harder to remember, and as a painful reminder about the security you have put in place. (Support personnel who have to continually reset forgotten passwords would tend to agree with the users in this particular situation.) Passwords make security obvious and bothersome. Users would rather not have to enter a password to access or to make specific application features available. Unfortunately, you still need some method of determining the user’s identity. The following sections present you with some mature ideas (those you can implement today) that you might find helpful in searching for your perfect solution.