Chapter 14. Considering Update Options

Updating means bringing new information, features, or interface elements into the application. Improving application accuracy also falls into the realm of an update. An update may not even affect application code in a significant manner, but can still affect security in a number of ways. For example, you can update a database to include a field that shows who last edited a record, which can improve security by making it possible to track the source of an error or infection that has occurred on the system. Changing prompts so the information you want from a user becomes clearer is a security fix that doesn’t necessarily require any recoding, especially when the prompts exist in an external file. The idea behind an update is to make the application better in some way so that a coding fix may become unnecessary. It’s important to know when to differentiate between an upgrade and an update, so the first part of this chapter spends time comparing the two processes and how they affect your application.

An update won’t always fix a security issue, just as an upgrade is sometimes overkill. In order to use organization resources effectively, you need to know when to use an update and when you really do need to perform an upgrade. The upgrade process appears in Chapter 13 and provides you with details on how this process works. This chapter compares updates with upgrades and helps you understand how the update process works.

Updates can fall into a number of categories. For example, you could choose to update your programming language suite. The new suite could provide better debugging, optimized code output, and faster executables. None of these features directly affect your application code, but they do affect how your application works. The simple act of recompiling your application modules produces effects that everyone can see.

In some cases, you need to perform emergency updates. Selling management on an update can be hard because updates often don’t affect the application code at all. It’s hard to tell a manager that you need time, resources, and personnel to make an update that won’t change a single line of code in the application. Trying to demonstrate the benefits of the change can also be hard until you actually make the changes and can quantify their effect to management in a way that demonstrates a return on investment.

As with upgrades, you need to test your updates. However, some update testing is significantly different from upgrade testing because, again, you don’t necessarily deal with code when working through an update. In summary, this chapter provides you with a complete primer on performing updates of various sorts so that you can better gauge when to use an upgrade versus an update.

Differentiating Between Upgrades and Updates

Both upgrades and updates affect the security of your application. However, an upgrade differs significantly in scope and purpose from an update, so it’s important to know the difference between the two. Most upgrades create significant new functionality and affect the code base at a deeper level than an update will. In fact, many updates don’t touch the code base at all. An update performs tasks such as:

-

Changing the database managed by the application. For example, a database that supplies catalog information may have an update to descriptions that help a user make better decisions.

-

Modifying existing features to make them friendlier or less prone to producing errors. For example, menu entries may now include speed keys so that users don’t have to guess about which key combinations to use.

-

Reconfiguring user interface features to make them better suited to user needs. An update may include support for more languages so that a user can see the user interface in a preferred language, rather than as a secondary or tertiary language that’s less clear.

-

Including more specific user interface options, such as changing a textbox entry to a radio button selection so that the user can make specific choices. Every element of chance removed from an application inherently improves application accuracy and enhances security.

In most cases, updates are more subtle from the developer’s perspective. It’s quite likely the developer may not even make the changes in some situations. For example, you need the services of a DBA to update the database, rather than rely on the developer to do it. A DBA can perform the task faster and more accurately in most cases. Designers can make many user interface changes using the coding techniques available today, making it unnecessary for the developer to change the code base at all. However, developers do become involved in the process when it comes time to test the update to ensure it performs as expected. Sometimes an update also requires a few code tweaks to make it work as expected.

Warning

Even if a developer isn’t involved in an update in a significant way, the team should always include developers in the discussion. In fact, updates, like upgrades, should have the full support of all stakeholders in the development team. This process includes user testers who verify that an update actually performs as requested and determine the update won’t cause significant new user errors or other potential problems (such as slowing users down or causing a huge spike in training costs).

One thing that upgrades and updates do have in common is a need for testing. Some organizations make the mistake of assuming that updates require lighter testing, or possibly no testing at all. The problem with this viewpoint is that putting an update on the production server will likely reveal issues that testing would show earlier and would make easier to fix. It’s important to remember that testing doesn’t just check the code base; it also checks for issues such as a user’s inability to interact with the application properly at some level. An update could actually open a security hole by making it possible for a hacker to interact with the application in a new way (especially when the update involves new user interface functionality). However, the emphasis of update testing is on the areas that are changed. For example, you still test every aspect of the application, but if the user interface has changed, then the focus of the testing is on the user interface and you make more checks in that area.

Note

Some update decisions fall outside the purview of the direct oversight of the development team. For example, a third-party update to a library, API, or microservice might occur automatically. In this case, you still have to test the update, but the testing actually occurs after the production system receives the update in many cases. Reversing the update may also prove impossible, so that breaking changes could cause an organization to look for a new third-party product or create an upgrade that fixes the problem. As a result, it’s essential to keep track of updates of all sorts and to be ready to test them at any time.

Determining When to Update

Third-party software could present a problem when it comes to updates. More than a few third-party vendors have tried to slip unannounced updates past development teams when the nature of a fix could prove embarrassing to the vendor. Security updates sometimes fall into this category—they just magically appear one day and no one is really sure when the third-party vendor released them. These updates can snowball and cause your application to stop working, or worse still, start acting in an unpredictable manner. One day you simply find that support starts receiving lots of irate calls from users who can’t quite seem to get the application to work.

Updates you make to your software or the updates made for you by third-party vendors, do require some level of planning, even when the third-party vendor forgets to mention the update or why it was made. You need to know that the change actually falls within the realm of an update and isn’t actually an upgrade in disguise. With this in mind, the following sections discuss some of the issues you should consider when determining an application requires an update.

Working Through Library Updates

- Library updates can be the hardest to make because a library becomes part of the application code. Because you import it directly into the application, some changes are hard to hide from view. In addition, some changes can cause odd problems to surface—bugs that have always been in the library, but never showed up because the application allocated memory or other resources in a different manner. The update may not even appear in the application after including the new library because the calls may have a slightly different name. These issues are all common to any sort of library update you wish to make. The following sections divide libraries into those that you incorporate from a third-party source and those that you develop on your own.

Dealing with third-party library updates

When working through a third-party update, the first step is to obtain a list of the changes—assuming the vendor provides one. Work through this list to determine which changes actually affect your application. Use a unit test to help determine whether the documented change reflects the actual change in the function before you begin making plans for the update.

Unfortunately, the list won’t tell you about some issues, such as name changes, in a way that appears as a change. In many cases, the vendor lists a name change as a new feature. Consequently, you must also review the list of new features looking for features implemented as a change to a function that you already use. For example, the new feature might have the name MySpecialFunction2() when it replaces MySpecialFunction(). The change could reflect new features, which means you have to review the update carefully to ensure you understand the ramifications to your code.

If you can obtain a copy of the code, use static testing techniques to better understand the changes the vendor made to the library. Running the code through a debugger to see the code in action can be helpful as well. You may not have these options available in most cases, but it doesn’t hurt to consider them.

Developing in-house library updates

Performing in-house library updates provides you with more control over the update process. You can perform all levels of required testing because you own the code. The most important issue is to document every change the update creates fully so that you don’t find reliability and security issues later. Many security issues occur when an update changes how a function works and the code continues to use the old approach to working with the function. The mismatch can cause security holes.

A worse situation occurs when an update appears as a renamed function, but the lack of documentation causes people who work with the library to continue using an older, buggy function. The result is that the team working with the library knows that the library contains a security fix, but the team working on the application has no idea that the security fix exists. Hackers actually review such library changes when possible and use the mismatch to discover security issues. Exploiting the mismatch is easier than looking for actual coding errors because the renamed function acts as a beacon advertising the fix for the hacker.

Employ static testing to ensure that the documented change actually matches the coded change in the library. After performing a static test, use unit testing to verify that the fix works as advertised. “Creating an Update Testing Schedule” provides you with additional information about the testing process.

Warning

The worst-case security hole is one where everyone thinks that a fix is in place, but the fix is missing, doesn’t work as advertised, or developers don’t implement the fix in the application. Always verify that developers actually implement updates in a consistent manner. Even if a fix fails to work as advertised, consistent implementation makes a follow-on update much easier to implement because everyone is using the function in the same manner.

Working Through API and Microservice Updates

APIs and microservices both suffer from the same problem—they work as black boxes for the most part. It’s possible to sneak an update in without anyone knowing. Some vendors have actually done this in the past, and it isn’t unheard of when working with in-house code either. The black box issue can cause all sorts of problems when the API or microservice fails to work as expected. Tracking down the culprit can be difficult. With this in mind, it’s essential to ensure that the development team fully documents every change to the internal workings of an API or microservice call and that the outputs remain the same for a given input. The following sections discuss the differences between third-party and in-house updates.

Warning

Application developers base their ability to trust an API or microservice on the assurance that for a given input, the output remains the same. An update can make the calls more secure, faster, or reliable, but it can’t change the outcome. If any element of an interface is changed by an update, then you need to create new calls to access that element. This approach ensures that developers will need to use the new calls in order to obtain the benefits provided by the update.

Dealing with third-party API and microservice updates

When working with third-party API and microservice code, you won’t have any access to the update code and won’t be able to perform any type of static testing. What you can do is perform intensive unit testing to ensure that the following considerations are true:

-

Each of the calls still produces the advertised outputs for given inputs with the range originally specified for the call.

-

The call doesn’t accept inputs outside the range originally specified.

-

Any tests involving exploit code (to ensure security enhancements actually work) fail.

-

Speed testing shows that the call successfully completes tasks within the time tolerance of the original call or faster.

-

Reliability testing shows that the call doesn’t fail under load.

-

Any documented changes to the code actually work as anticipated.

Developing in-house API and microservice updates

Always perform static testing as a first measure of in-house updates. During the process, you want to verify that the documentation and the code changes match completely. A significant problem with updates is that the API or microservice development team thinks that an update works one way when it actually works another. It’s also a good idea to match documented updates against trouble tickets to ensure that the fixes address the issues described in the trouble tickets. This visual checking process might seem time consuming, but performing it usually makes subsequent testing far easier and reduces the probability of a security issue sneaking into the code accidentally significantly less. The black box nature of API and microservice code makes the static check even more important than it is for libraries.

Your in-house code will also benefit from the same sorts of checks you perform on third-party code (see “Dealing with third-party API and microservice updates” for details). However, you can now perform these checks with the code in hand to better understand why certain checks fail.

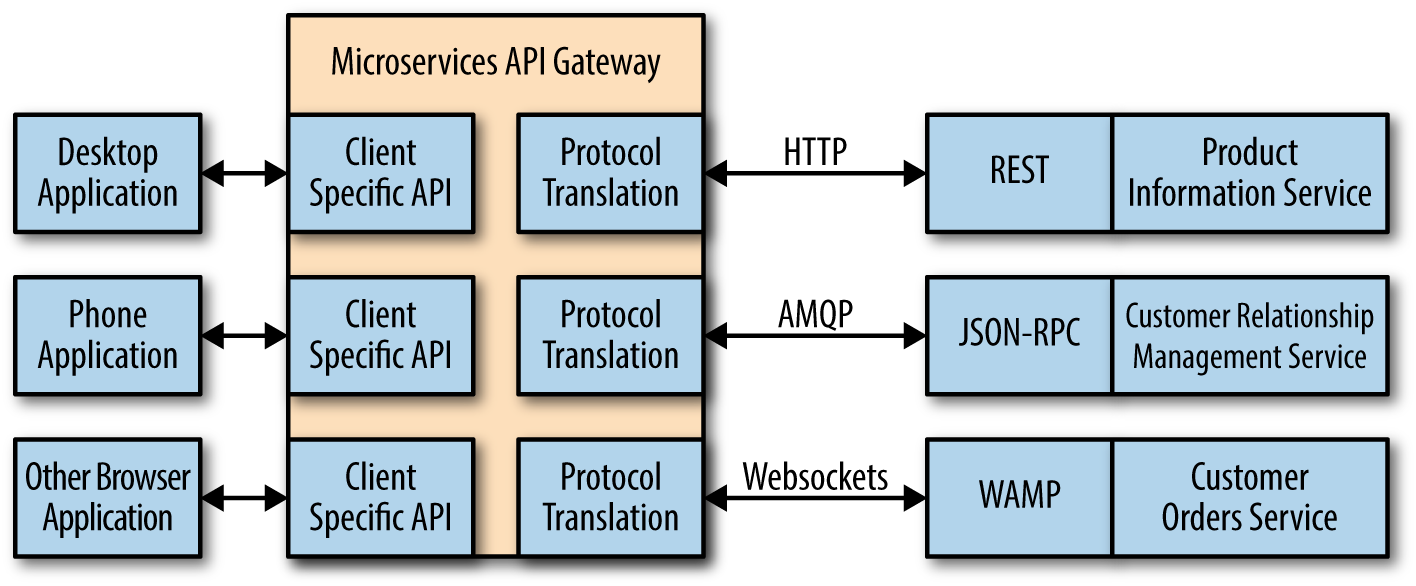

A particularly tricky issue when working with microservice updates is that many organizations now rely on a microservices API to make the various microservices look like a custom API. The use of a microservices API reduces the programming burden on developers and ensures that every platform has the required resources using protocols available to that platform. Figure 14-1 shows a typical microservices API setup.

Figure 14-1. When using a microservices API, test the API as well

It’s essential to test the various microservices directly to ensure the update hasn’t changed the way in which the microservice works natively. However, you must also test the microservice API to ensure that the API still responds correctly to all the platform types that the application supports. Otherwise, you can’t be certain that the microservice API will continue to provide correct results in a secure and reliable manner.

Accepting Automatic Updates

Some vendors now make it as hard as possible to ignore automatic updates. An automatic update is one that a vendor pushes to a client in some way. In some cases, the vendor simply changes the software at the server so you end up using the update automatically. These are the main reasons vendors like automatic updates:

-

Fewer security or reliability issues due to using an outdated version

-

Reduced support costs

-

Smaller staffing requirements

-

Improved ROI

Of course, the question isn’t one of whether automatic updates are good for the vendor, but whether they’re good for your organization. In many cases, using automatic updates proves problematic because the organization isn’t prepared for the update and breaking changes usually create support issues. The most severe cases result in data loss or security breaches, which run counter to making an update in the first place.

Most organizations try to avoid automatic updates when possible in order to reduce the potential for unexpected side effects. When a third-party vendor insists on automatic updates and you have no alternative for third-party software, then you really do need to have someone tracking the third-party software to determine when an automatic update will appear. Testing the update immediately can help you avoid problems with breaking updates and potentially improve the ability of your organization to react to sudden changes as well.

Updating Language Suites

Web applications fall into a somewhat special category in that users who speak any of a number of languages could simply find them while searching for something else. Any public application you create, even if you only mean for one group to use it, does sit on the world stage of the Internet where anyone from anywhere can access it. Theoretically, you can try to block access, but that’s a counterproductive strategy. If you suddenly find that your application is receiving accolades from places you never imagined, you may need an application update that addresses language-specific issues. The following sections discuss some of the issues you need to consider, especially when it comes to maintaining a secure application environment.

Creating a Supported Language List

Not every application supports every world language. Trying to make this happen would be a logistics nightmare and it isn’t necessary because not everyone will actually want to use your application. However, you may find that you need to support more than just one language as the application becomes more popular. Modern server software generally makes it possible to track the locations that access your application. The location itself may not provide everything needed. For example, it may surprise you to know that Romania has a number of official languages:

-

Romanian

-

Croatian

-

German

-

Hungarian

-

Romani

-

Russian

-

Serbian

-

Slovak

-

Ukrainian

However, these are just the official languages. Your application user might actually speak a different language, such as Italian. It isn’t possible to know precisely which language to support based solely on location. The point is that if you suddenly find that your application is receiving lots of requests from Romania, you already know that the user is not likely to speak English natively (or perhaps at all). If your application only supports English, then you might find the user is confused, makes mistakes, and potentially causes both security and reliability problems.

Note

In some cases, you can make assumptions about language support based on the application environment. An application running in a private environment in the United States, for example, might only need to support English and Spanish as options. When the application runs in Romania, you might want to support all of the official languages to ensure that everyone can access your application. Considering application environment is an important part of working through the language support list.

Using location does provide you with a good starting point, but you need to obtain language statistics in some other way. About the only effective means to ensure you get good data is to provide feedback forms or conduct user surveys. As you accumulate statistics about application use, you see patterns emerge and can start deciding which languages to support. Creating a list of supported languages is important because you need to know which languages you can actually afford as part of an update and you want to be sure you target the most popular languages first.

Warning

When creating an update to support multiple languages, you typically want to provide different URLs for each language. Otherwise, it becomes nearly impossible for someone to find the language they need. In addition, using different URLs makes it possible to detect information the browser provides and make a reasonable language selection for the user. The two common methods for creating unique URLs for each language are:

- Language-specific URL

- The same domain hosts multiple languages. An URL such as http://www.mysite.com/en/stuff.html would support the English language, while http://www.mysite.com/de/stuff.html would support the German language. The benefit to this approach is that you save money by not having to buy multiple top-level domains (TLDs). This approach focuses on language.

- Multiple TLDs

- Each language has its own domain. An URL such as http://www.mysite.us/stuff.html supports users in the United States, while http://www.mysite.ro/stuff.html would support users in Romania. The benefit of this approach is that search engines, such as Google, will offer a separate link for each language you support, rather than treat all of the languages as duplicated content and display only one link. This approach focuses on country. You can find a list of the TLDs on Wikipedia.

Obtaining Reliable Language Specialists

If you choose to perform a language-specific update of your application, you can only ensure that it works reliably and securely when the update looks as if you originally wrote it in the target language. Everyone has worked with instructions or other written communication that someone originally wrote in another language and then translated to whatever language you speak. When the translator exercises less than the usual skill, the results are often hilarious. The actual meaning behind the various bits of information becomes lost and no one can take the information seriously. However, the security issues that this kind of miscommunication causes are no laughing matter.

However, even a great translator will do a less than perfect job if you don’t provide the right environment in which to perform the translation. The following steps provide insights into the techniques you can use to create a better application translation and ensure users can actually follow your prompts as a result:

-

Place all hardcoded strings in the application in a database of some type. Identify each string by its location within the application.

-

Replace each hardcoded string with a placeholder control that you fill with the correct language string when the page loads.

-

Create a separate database file for each language and ensure the database name reflects the language content.

-

Fill each language database with the translated strings provided by the translator. Use precisely the same identifiers for each of the strings so that the identifier always matches the screen prompt.

-

Add code to the application to perform the task of filling the controls with the correct prompts from the database.

-

Test the application initially with the original language to ensure that the prompts work as intended.

Note

It’s always a good idea to obtain a second check on language updates, especially when no one in the organization speaks the language natively. There is always a potential for errors when making a translation. In addition, you need to consider social mores of the people who speak the language. The most problematic issue is that some languages won’t have a direct translation for some words. As a result, you must choose the correct approximation and then ensure there is little room for misinterpretation of the approximate translation. Having an independent check of the translation will save embarrassment later, in addition to making the application more secure by reducing the potential for input errors.

Verifying the Language-Specific Prompts Work with the Application

Simply translating the prompts isn’t enough in many cases. You need to rely on your language specialist to ensure that every prompt on every screen reflects how people who speak the language natively expect to see the prompts. For example, some languages read from left to right, while others read right to left. The orientation of the prompts is important, as is the formatting. You may need to provide application hints and formatting to ensure that people using the application can actually interpret the prompts correctly.

Ensuring Data Appears in the Correct Format

Different areas of the world format data in different ways. Some countries use a comma, instead of a period, for the decimal place. These same countries might use a period, in place of a comma, for the thousands place indicator. Imagine what would happen if a user changed values based on the wrong formatting in this situation. A user could enter values that could cause the application to misbehave, crash, or simply do something odd. The result could be a security breach or an opening that a hacker needs to create a security breach. Many security issues come out of seemingly silly errors that a hacker exploits to gain the small advantage that leads to a big payoff.

The presentation of data in the right form ensures there are no misunderstandings. Creating a potential security issue simply because of a mix-up between commas and periods seems like a problem that you can easily solve, but sometimes proves absurdly difficult. You can find examples of thousands indicators and decimals points by language at http://docs.oracle.com/cd/E19455-01/806-0169/overview-9/index.html. The graphic guide at http://www.statisticalconsultants.co.nz/blog/how-the-world-separates-its-decimals.html is also interesting.

Defining the Special Requirements for Language Support Testing

Testing your application becomes a lot harder when you start adding multiple languages. Unless you plan to keep those language specialists around for the life of the application, you need some other means to verify that updates aren’t causing language support problems. Proper planning, change documentation, and verification in the original language are your best starting points. Whenever you create a change to the application that affects a prompt in the original language, you must consider changing the prompts in all of the other supported languages as well. To make this process as easy as possible, use these suggestions:

- Plan

- Make sure you check each change carefully. Sometimes a designer will try to tweak prompts when they don’t really require any change. Keeping the number of changes small will reduce costs, ensure the application remains reliable, and help improve security by reducing the potential for miscues.

- Document

- Every change to every prompt in the original language must also appear in every other language your application supports. A security and reliability issue starts when the language editions get out of sync. It’s essential that this part of the update process runs smoothly and without error or you’ll find yourself hiring that language specialist again to clean up the mess.

- Verify

- Ensuring that every change occurs in every location is hard because you probably don’t have staff that speaks the language you support. A good way to verify the language update is to use screenshots. Compare the original screen to the updated screen to verify that the prompt changes really did take place. The only problem with this approach is that you can’t be sure that prompt change is completely correct.

Note

Because of the manner in which the application uses prompts, you don’t need to test the underlying code for each language. What you change for each language is the interface and that’s where the focus of your testing takes place for language-specific issues. Ensuring you get good prompts and that those prompts appear in the correct places is the basis of language support testing.

Performing Emergency Updates

Upgrades are always well planned and timed carefully. Most upgrades receive the proper planning and timing too. However, when a hacker has just exposed some terrifying hole in your application that you need to act on immediately, sometimes an update can’t wait—you must create an interim fix and deploy it immediately or suffer the consequences. No one likes emergencies. The more critical the application and the more sensitive the data affected, the less anyone likes emergencies. The following sections help with the emergencies that come in the middle of the night, lurking, waiting for your guard to go down.

Avoiding Emergencies When Possible

Everyone experiences an emergency at some point in the application support process. It just goes with the territory. However, you can avoid most emergencies by planning for them before they happen. Here are some issues you need to consider as part of avoiding emergencies:

-

Perform full testing of each update and upgrade before deployment.

-

Deploy updates and upgrades only when system load and availability supports it.

-

Avoid deploying updates and upgrades when staffing levels are low or key personnel are absent.

-

Ensure the application has access to all required resources from multiple sources if possible.

-

Plan for overcapacity situations and ensure you have adequate additional capacity available to meet surge requirements.

-

Assume a hacker is going to attack at the worst possible time and plan for the attack (as much as possible) in advance.

-

Test system security and reliability regularly.

Creating a Fast Response Team

Your organization needs a fast response team—a group of individuals that are on call to handle emergencies. It doesn’t have to be the same group of individuals all the time—everyone needs a break—but you should have an emergency response team available at all times, especially those times when hackers love to attack (such as weekends). An emergency response team must contain all of the individuals that an application requires for any sort of update. If you require a DBA to make an update normally, then you need a DBA on your emergency response team. The team should train together specifically on handling emergencies to ensure they’re ready to go when the emergency occurs.

Warning

Never perform an upgrade as an emergency measure. Upgrades deeply affect the code and you can’t properly test the code with the short response time that an emergency requires. When you release an upgrade without proper testing, you likely include some interesting bugs that a hacker would love to exploit. Always play things safe and keep emergency measures limited to those items you can handle as an update.

Performing Simplified Testing

Depending on the nature of the emergency, you may have to release the update with a minimum of testing. As a minimum, you must test the code that the update directly affects and possibly the surrounding code as well. When a hacker is breaking down your door, you might not have time to test every part of the code as normally required. It’s important to remember that the update you didn’t release might have kept the hacker at bay. The issue comes down to one of balancing risk—the emergency on one side and the potential for creating a considerably worse problem on the other.

Creating a Permanent Update Schedule

Always treat emergency updates as temporary. You have no way of knowing how rushed the fast response team became while trying to get the update out. The team could have made all sorts of errors during the process. Even if the update works, you can’t leave the emergency update in place without further scrutiny. Leaving the emergency update in place opens security and reliability holes that you might not know are there and could cause considerable problems for you in the future.

Note

It’s a good idea to perform a walkthrough of the emergency after the fact, determine what caused it, and consider how the fast response team responded to it. By performing a walkthrough, you can create a lessons-learned approach to handling emergencies in the future. You can bet that hackers constantly work to improve their skills, so you must improve your skills as well. Taking time to understand the emergency and looking for ways to handle it better in the future are valuable ways to create a better fast response team.

As part of the permanent update process, make sure you perform static testing of the update to verify that the fast response team reacted properly and provided a good fix for the problem. Make sure you schedule the permanent update as quickly as possible to ensure you fix any additional problems before someone takes advantage of them. The new update should rely on all the usual testing procedures and follow whatever plan you have adopted for permanent updates.

Creating an Update Testing Schedule

No matter how you create the update or the timing involved, it never pays to rush an update into deployment without some testing time in place. Rushing an update out the door almost always causes problems in the end. In fact, the problems created by rushing are usually worse than if you had left the update out entirely. Testing provides a sanity check that forces you to slow down and recheck your thought processes in putting the update together. Used correctly, testing ensures that your fellow team members are as certain as you are that the update is solid and won’t cause issues that end up being a security nightmare.

Update testing doesn’t quite follow the same pattern as upgrade testing because you change less of the application during an update and can focus most of your energy on the features that changed. In addition, you may perform updates during an emergency and need to field the update as quickly as possible to prevent a major security breach. With this in mind, you must perform these levels of testing to ensure the update doesn’t do more harm than good:

-

Unit

-

Integration

-

Security

When the update serves to address an emergency, these three levels will usually keep the update from doing more harm than good. However, you must perform these additional levels of testing as soon as possible:

-

Usability

-

Compatibility

-

Accessibility

-

Performance

Once the dust has settled and you have additional time for testing, you need to ensure that the update is fully functional. The best way to ensure functionality is to perform these additional levels of testing:

-

Regression

-

Internationalization and localization

-

Conformance

Note

You could perform other sorts of testing, but only as needed. For example, web applications seldom require any sort of installation, so you don’t need to perform any sort of installation testing in most cases. The exception is when a web application requires installation of a browser extension, browser add-on, browser service, system agent, or some other required software.