Chapter 10. Creating an API Safety Zone

Any API you create or use as part of your application has the potential for creating a large array of problems. However, unlike libraries, you can actually make using an API much safer because an API executes in its own address space and in its own process. Placing the API in a sandbox or virtual environment (essentially a protected environment) makes it possible to:

-

Control precisely what actions the API can take, the resources it can access, and the ways in which it interacts with your application. Of course, you can also starve the API for resources or make it impossible for the API to complete a task by making the sandbox or virtual environment too inclusive. There is a balance you must maintain between risk (security) and being able to perform useful work.

-

Control how the application interacts with the API. For example, you make it less likely that errant or malicious input will cause any sort of disastrous effect. The application inputs are strictly controlled and unexpected inputs tend to have a reduced effect or no effect at all. Of course, this kind of protection can also make it hard to experiment with the API or perform certain types of testing.

This chapter helps you understand the concept of an API sandbox/virtual environment and determine precisely how you can use one with your next programming project to keep things safe. As part of working with API sandboxes, this chapter also discusses some sandboxing and virtual environment solutions. Not every solution works in every situation, so it’s a good idea to know about a number of potential solutions.

Warning

Like any other security solution, using an API sandbox isn’t a silver bullet. It won’t keep every hacker at bay and it won’t keep every API from damaging your application or its associated data. Using an API sandbox reduces risk. You need to determine whether the API sandbox reduces the risk enough or whether you need additional measures to keep your application safe. Security isn’t about just one technique or one measure. A secure system relies on a number of security layers to get the job done.

The final section of the chapter discusses a sandboxing alternative, virtualization. Even though it might seem that a virtual environment and a sandbox are essentially the same thing because they achieve largely the same goals, they really are different technologies; therefore, this last section helps you understand the differences in detail. A virtualized environment tends to make it appear to the API that it executes in a completely open environment. However, a virtualized environment is completely cut off from everything else and the API works through a strict access scheme.

The point of this chapter is to help you create an environment where an API can execute without truly connecting with other parts of the application. The environment is strictly controlled. It shows two methods to achieve this goal and helps you understand when to choose one technology over the other. Choosing the right kind of safety zone is essential if you want to obtain usable results from your application testing and ultimately application usage.

Note

This book uses the term safety zone to refer to the goals achieved by both sandboxes and virtual environments. It’s essential to remember that the goals of the two technologies are basically the same, but how the technologies achieve these goals is significantly different. Because of the differences, you may find that choosing one technology over the other gives you advantages with certain application development needs.

Understanding the Concept of an API Safety Zone

An API safety zone provides a secure and flexible method of testing or using any API you create. It’s always a good idea to use an API safety zone during testing to ensure you can recover from mistakes quickly. You may decide to continue using an API safety zone after moving the API to the production environment for the security features that it provides.

Using a sandbox does provide additional security. However, many organizations aren’t concerned about security when they implement a sandbox environment. In addition to security, a sandbox can provide you with these benefits:

-

Reduced costs by controlling resource usage

-

Controlled access of third-party APIs

-

Improved testing and development environment in the form of better control

-

Decreased time to market

-

Simulated error scenarios for testing

-

Monitored API performance

Organizations also use virtual environments for purposes other than simply securing the API. As with a sandbox, a virtual environment reduces costs by controlling resource usage, controls access to third-party APIs, and improves the testing and development environment. A virtual environment has many advantages from the organizational perspective including:

-

Reduced recovery time after an API crash

-

Enhanced speed and network bandwidth control

-

Improved energy usage

-

Diminished hardware footprint

-

Faster provisioning

-

Reduced vendor lock-in

-

Increased uptime (even when security and reliability events are rare)

-

Extended application life

The choice between using a sandbox or virtual environment may come down to the additional features that each provides if the API will work equally well with either option. It’s essential to consider the security aspects of each option first, however, if you want to maintain the kind of security required by today’s applications.

Defining the Need for an API Safety Zone

Security is about risk management. Making requests of any API incurs risk because you don’t know that the API hasn’t been compromised, assuming that the API was free of potential problems in the first place. The need for policing any API that you use becomes apparent when you read about the damage done by APIs online. Any API you use could send data that turns out to be a virus, script, or other malware in disguise. Because of the way in which APIs are used, you’d only find out about the issue when everyone started to complain that the application was down or you found confidential information in a place you didn’t expect to find it (assuming someone else doesn’t find it first).

The reverse issues occur when you own the code for an API. Your API may provide a valuable service for your customers. It may offer access to all sorts of confidential data, some of which the customer should access, and some that should remain hidden. The wrong sort of input could cause your API to react in unexpected ways—causing damage to the API, its data, and the server in general. Consequently, you need to find ways to sanitize the input data, but also to provide protection when it turns out that the sanitation process didn’t work as well as anticipated.

Whether your API sends or receives data as the result of a request, using the API in a sandbox or virtual environment only makes sense because doing so will reduce your risk. Keeping the bad guys out completely may not work, but you can minimize your risk and the effects of any breach you experience. The following sections build a case for working with APIs in a sandbox or virtual environment.

Ensuring Your API Works

Security is about risk management. Ensuring your API works as anticipated reduces risk by reducing the potential for someone making the API work in a manner you hadn’t considered. Hackers often do their dirty work by looking for ways to make code misbehave—to do something the owner doesn’t want it to do. Using an API safety zone lets you test your code in ways that you normally couldn’t test it without creating problems on the test server. You can perform these sorts of tests to ensure your API works as intended:

-

Verify that the correct inputs provide the correct responses

-

Use range checks to ensure that the API responds correctly to out-of-bounds data

-

Input data of the wrong type to ensure the API sanitizes data by type

-

Check data length by using data inputs that are both too long and too short

-

Purposely input invalid data that hackers might use, such as scripts, tags, or binary data

-

Leave required data out

-

Add extra inputs

-

Create null data inputs

-

Overload the API

Enabling Rapid Development

Placing your API directly on the server means that you have one copy of the API for everyone to use. Naturally, the second that any of the developers decides to try something radical that causes the API or the server to crash, everyone else has to stop work as well. You want your developers to feel free to experiment because you can be sure the hacker will certainly feel free to do so. Creating a constrained environment where everyone has to play by the rules is almost certain to hide security holes that a hacker will use to breach your server.

Sandboxing helps enable rapid development by making it less likely that the server will crash. If the API experiences problems, you can usually recover quite quickly. The sandboxed environment will also make it quite easy to simulate all sorts of conditions that could occur in the real world, such as a lack of resources or resources that are completely missing. However, you still typically have one copy of the API running, so it’s not quite as free as you can make the development environment.

Using a virtual environment makes it possible for each developer (or group of developers) to have an individual copy of the API. Of course, you use more server resources to make this scenario happen, but the point is that you end up with an environment where no one developer can intrude on any other developer’s programming efforts. Everyone is isolated from everyone else. If one developer thinks it might be a good idea to attack the API in a certain way and the attack is successful (bringing the API or the virtual environment down), those efforts won’t affect anyone else. The point is to have an environment in which developers feel free to do anything that comes to mind in search of the perfect application solutions.

The trade-off to consider in this case is one of resources versus flexibility. The sandboxing approach is more resource friendly and probably a better choice for small organizations that might not have many hardware resources to spare. The virtual environment is a better approach for organizations that are working on larger APIs that require the attention of a number of developers. Keeping the developers from getting in each other’s way becomes a prime consideration in this case and the use of additional hardware probably isn’t much of a problem.

Note

Think outside the box when it comes to acquiring hardware for development and testing purposes. The system that no longer functions well for general use might still have enough life in it for development use, especially if your goal is to test in constrained environments. In short, don’t always think about new hardware when it comes to setting up a test environment—sometimes older hardware works just as well and you may have plenty of it on hand as a result of equipment upgrades.

Certifying the Best Possible Integration

A problem with integration testing in many cases is that the testing looks for positive, rather than negative results. Developers want to verify that the:

-

API works according to specification

-

Functionality of the API matches the expectations for any business logic the API must enforce

It turns out that there are a number of solutions that you can use for integration testing that will also help you find potential security issues. The following sections describe the most popular techniques: sandboxing, creating a virtual environment, using mocking, and relying on API virtualization.

Sandboxing integration testing

Using a sandboxed environment makes it possible to perform true-to-life testing. In some cases, you can get false positives when the sandboxed environment doesn’t match the real-world environment in some way. In addition, using the sandboxed environment typically doesn’t show the true speed characteristics of the API because there is another layer of software between the API and the application. Speed issues become exaggerated when multiple developers begin hitting the API with requests in an environment that doesn’t match the production environment.

Warning

If you find that the tests you create produce unreliable or inconsistent results, then you need to create a better test environment. When it’s not possible to input specific values and obtain specific outputs, then the testing process produces false positives that could take you days to resolve. False positives are especially problematic when working with security issues. You can’t have a particular set of conditions produce a security issue one time and not the next.

Virtualizing integration testing

The alternative of a virtual environment provides the same true-to-life testing. Because of the way in which a virtual environment works, it’s possible to mimic the production environment with greater ease, so you don’t get as many false positives. Actual testing speed usually isn’t an issue because each developer has a private virtual environment to use. However, unless you have the right kind of setup, you can’t reliably perform either application speed or load testing because the virtual environment tends to skew the results. Recovery after a failed integration test is definitely faster when using a virtual environment.

Mocking for integration testing

Some developers use mocking for API integration testing. A mocked API accepts inputs and provides outputs in a scripted way. In other words, the API isn’t real. The purpose of the mocked API is to test the application portion separately from the API. Using a mocked API makes it possible to start building and testing the application before the team codes the API.

The advantage of mocking is that any tests run quite quickly. In addition, the response the application receives is precise and unchangeable, unlike a real API where responses could potentially vary. (A mock doesn’t perform any real-world processing, so there is no basis for varied responses.) However, mistakes in the mock can create false positives when testing the application.

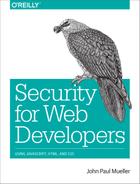

Examples of mocked APIs exist online. For example, if you want to test your REST-based application, you can use Mocky to perform the task. You use Mocky to create a canned anticipated response that an application can query, as shown in Figure 10-1. Mocky makes it possible to create various response types as well. Not only do you control the HTTP response, but you also control the content response type and value.

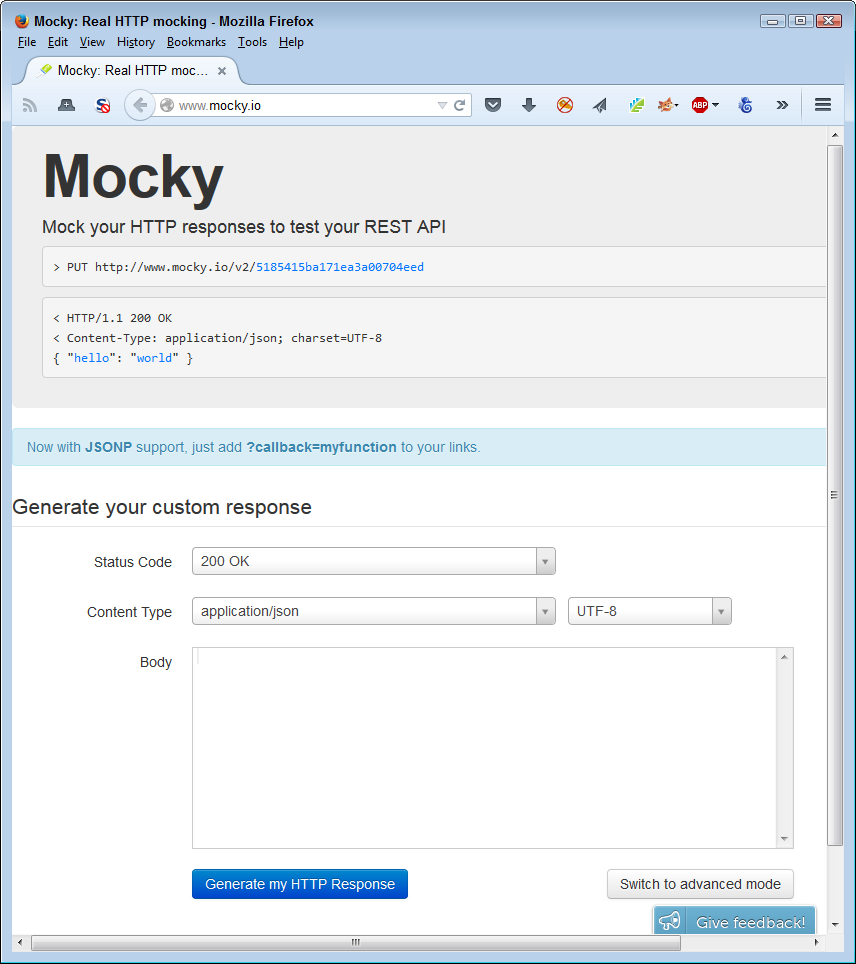

A number of mocks provide both SOAP and REST support. For example, mockable.io/ supports both SOAP and REST, as shown in Figure 10-2. In order to use this service, you must sign up for an account. A trial account lets you perform testing, but any data you generate isn’t private. In order to create a private setup, you must obtain a paid account.

Figure 10-1. Mocky provides a simple form you fill in to configure testing

Figure 10-2. Use mocks such as mockable.io when you need SOAP support

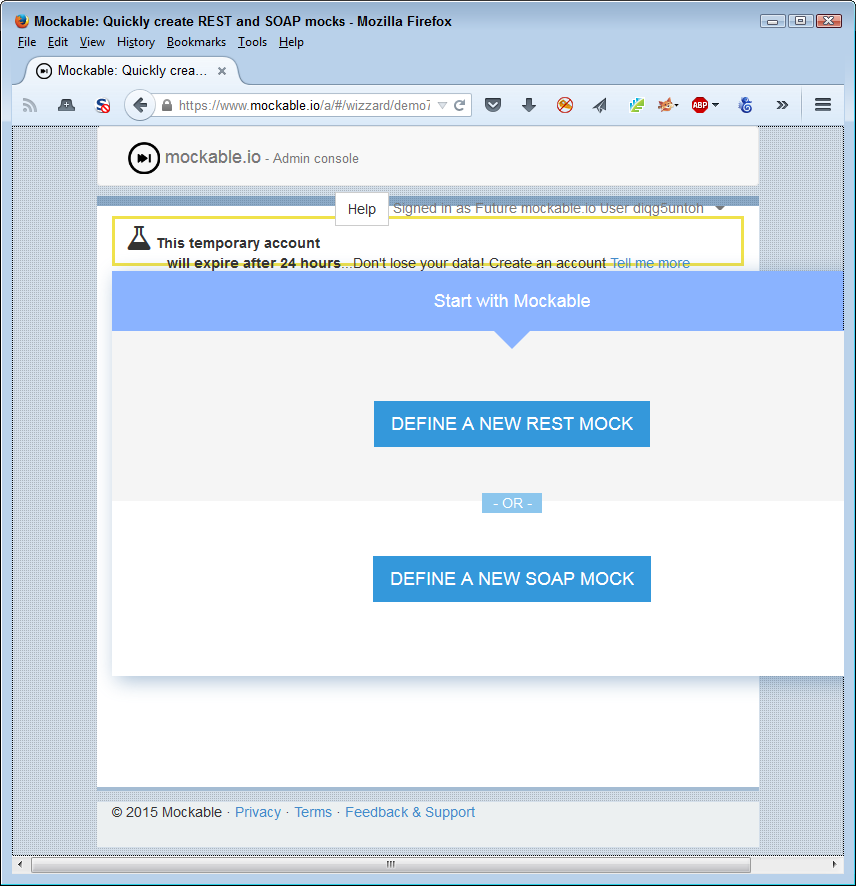

In this case, once you select the kind of mock you want to create, you fill out a form to perform the actual testing process. As shown in Figure 10-3, the list of settings you can change for the mock is extensive. In this case, you also select items such as the verb used to create the call. The point is that a mock provides an environment where you provide a specific input in a specific way and get a specific result back.

Figure 10-3. Some mocks provide a significant amount of control over the testing interface

The more advanced mocks, such as Apiary, offer a range of services to make the mocking process easier. You can use this service to generate documentation, integrate coding samples, perform debugging tasks, and automate testing. Naturally, as the complexity of the mock increases, so does the price.

Integrating using API virtualization

A sandbox environment makes it possible to do something that you normally couldn’t do easily—virtualize a missing API. It’s entirely possible that your development schedule won’t match the schedules of some of the third parties you depend upon for services. When this problem occurs, companies are often left twiddling their thumbs while waiting for the dependent API. Of course, you could always reinvent the wheel and create your own version of the API, but most organizations don’t have that option and it really isn’t a good option even when you do have the resources.

Note

Never confuse API virtualization with server virtualization or the use of virtual machines. In the latter two cases, you create an entire system that mimics every part of a standard platform as a virtual entity. API virtualization only mimics the API. You couldn’t use it to perform tasks such as running an application directly.

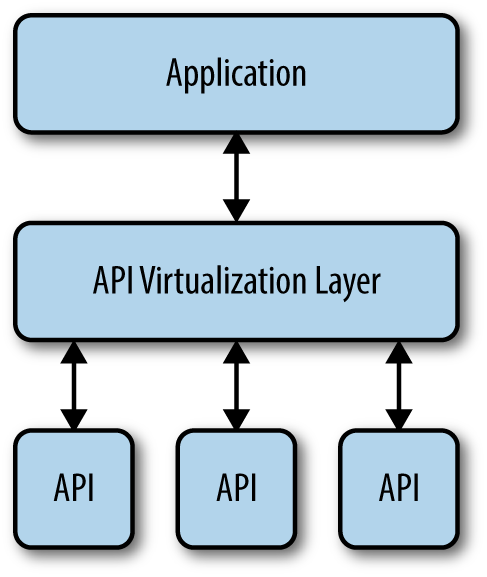

Virtualization is the process of creating a representation of an API that you can use for testing and other purposes. The representation acts as a sort of black box that you can use in lieu of having the actual API to rely on. This black box ultimately provides access to the actual APIs, but it could also provide access to a mock instead. The point is that the API virtualization layer provides a consistent means of interacting with the API and integrating an application with it, even if the API isn’t completely finished. Figure 10-4 shows how the API virtualization layer looks.

Figure 10-4. The API virtualization layer separates the application from the APIs

Using API virtualization hardens your application against the sorts of failures that hackers love. The virtualization layer makes it possible for the application to continue running even when the API itself isn’t functioning correctly. For example, you could create a mock to stand in for the API when a failure occurs and the application will simply continue running. The user might not even notice any difference. Later, when the API is back online, you can perform any required recovery in the background. The point is that a hacker won’t be able to get the application to fail simply by overloading the API.

In some cases, you can create an even better environment by combining a sandbox product with API virtualization. For example, SmartBear provides two products: VirtServer and Ready API!, that make it possible to create a two-layer approach to working with APIs (read more at http://smartbear.com/product/ready-api/servicev/features/share-virtual-services/). The idea is to gain additional flexibility in working through complex API interactions.

Verifying the API Behaves Under Load

Load testing is important for security reasons because hackers often overload an API or an application in order to cause it to fail in a specific way. After the API or application fails, the hacker uses various tricks to use the disabled software as an entry point to the network. Consequently, knowing how your API will degrade when loaded is essential because you want it to fail gracefully and in a manner that doesn’t open huge holes for the hacker to enter. It’s essential to keep in mind that every API is going to fail at some point if you put enough of a load on it. Despite promises you might have read in the past, there isn’t any way to make software scale to the point it can accept an infinite load (assuming that it’s even possible to test for such a thing).

In order to perform load testing, you must be able to simulate a load, which usually means adding software to the system that will make the required calls, reduce resources as needed, and perform any required logging. Most developers use a sandboxed environment for load testing because it provides the most realistic testing environment. Look for tools that work with all the platforms you need to support. Some products, such as LoadUI, provide versions for Windows, Mac, and Linux testing. Before you get any tool, try to download a trial version to see if it works as promised.

A starting point for any API load testing is determining how to test it. You need to obtain statistics that tell you how to load the API to simulate a real-world environment. To ensure the API works as advertised, you need to determine:

-

Average number of requests the API receives per second

-

Peak number of requests the API receives per second

-

Throughput distribution by endpoint (the locations that make calls to the API)

-

Throughput distribution by user or workgroup

It’s also important to decide how to generate traffic to test the API. You may decide to start simply. However, it’s important to test the API using various kinds of traffic to ensure it behaves well in all circumstances:

-

Repetitive load generation (where the testing software uses the same request sequence)

-

Simulated traffic patterns (a randomized version of the repetitive load generation or a replay of API access log data)

-

Real traffic (where you have a test group hit the API with real requests)

After you establish that the API works under standard conditions, you need to vary those conditions to simulate a hacker attack. For example, a hacker could decide to flood the API with a specific request, hoping to get it to fail in a specific manner. The hacker could also decide to keep adding more and more zombies in a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack that simply loads the API down to the breaking point. Get creative. It’s important to determine what will break your API and cause it to fail, and then see how the API fails. Knowing how the API will fail will help you determine the level of risk that each kind of hack poses so that you can better prepare for the consequences.

Keeping the API Safe from Hackers

After you have performed all of the other testing described in this chapter, you might think that your API is safe. The problem is that you haven’t thought about all the ways in which the hacker will attack it. If someone is truly determined to break your API, they’ll find a way to do it. Chapter 9 discusses the need to think like a hacker. Of course, that’s a good start, but once you have ideas on how someone could break your API, you need to test them. The only way you can do that safely is to try creating an API safety zone.

In this one case, testing with both a sandboxed and a virtualized environment will help you get the best results. Each environment provides specific advantages to the tester that will help ensure the API will behave itself in the production environment.

Warning

It’s never a good idea to test your application and its associated APIs in a production environment unless absolutely necessary. Many developers have tried it and found that the testing procedures actually damage the data the application was supposed to protect. In addition, you generally won’t be able to schedule time for testing that’s convenient to users. Because users add variations to the testing environment, you need to test at a time when users aren’t actively engaged in performing tasks. Otherwise, you can’t be sure that a failed test is the result of testing or of user input.

Developing with an API Sandbox

Visualizing an API sandbox is relatively simple. It’s the same idea as a sandbox for children. The API has access to everything contained within the sandbox, but nothing outside of it. Keeping an API in a sandbox has important security implications because it becomes less likely that an API, even one that is under attack by a hacker, could potentially do anything to harm the application or its data. By keeping the API sequestered, it can only damage resources that are already set aside for it. This means that the API is effectively unable to do damage in an unmanaged way unless the designer implements the sandbox incorrectly or ineffectively.

Nothing comes free. By placing an API in a sandbox, it’s also quite possible that the API will no longer function as expected or will work slowly in the resource-starved environment. It’s essential to create the API sandbox such that the API functionality remains robust. Creating a balanced API sandbox can be difficult and it requires an in-depth knowledge of precisely how the API works with the application to perform specific tasks. (It’s not necessary to understand every detail of the API because it’s unlikely that the application uses the entire API.)

Many articles make a big deal out of sandboxes, but really, it isn’t anything all that much different than working with any modern operating system. At one time, the application had full access to the entire machine. Today, an application has controlled access to system resources that include memory and processing time. The application must share with other applications running on the system, so the operating system controls access to resources. What you have with a sandbox is an additional layer of control, but the control is similar in functionality and effect to any other sort of application control.

Once you establish good reasons for developing an API sandbox, it’s time to develop one for use with your application. Actually, you need an individual sandbox for each API you use in your application. Some applications use quite a few of them and it doesn’t help to contaminate one API’s environment with problems generated by another API. Keeping everything separated and unable to destroy anything else is always a good idea. In some cases, you might have to become creative in the way that you build an application so the APIs continue to work as they should, but the idea of keeping APIs in completely separate and controlled environments is a great idea.

Using an Off-the-Shelf Solution

Building your own sandbox could be a lot of fun, but it’s more likely a waste of time. You want to focus on your application, rather than build an environment in which to use it safely. That’s why you need a good off-the-shelf solution that you can trust. The following list describes a few of the available sandbox solutions:

- AirGap

- This is an interesting idea. Instead of allowing the browser to run on the client system, it runs on a server in the cloud. The user relies on a viewer application that provides isolation from the browser. You see the browser window and interact with it as you normally would, but the only thing that is running on the client system is the viewer. The vendor promises physical, connection, session, and malware isolation using this approach. You’d need to try it with your application to see if the viewer approach would actually do the job.

-

Warning

A solution such as AirGap works fine for many users. However, you must consider where the browser is running. If you are in a regulated industry or your application deals with sensitive information, then AirGap won’t work for you. The browser really does need to run on the host system to work correctly and to maintain the confidentiality that the legal system (or common sense) requires.

- Sandboxie

- You can use Sandboxie to run any application on the host system, not just browsers. This means that you can use Sandboxie to perform all sorts of tasks that other solutions might not support. Because it runs on the client system, all your sensitive data remains fully protected from view. The vendor provides a trial version you can test. When you choose to buy a license, you have a choice between a home and small business version or an enterprise version. Only the enterprise version comes with a support package. Sandboxie only works with the Windows operating system.

- Spoon.net

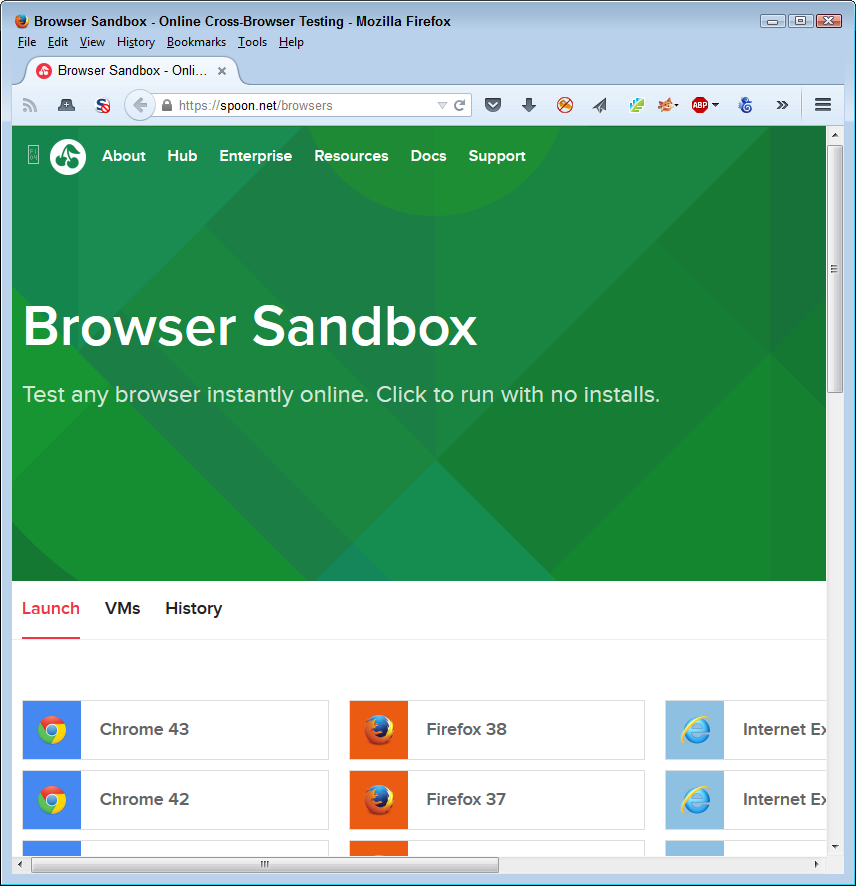

- Sometimes you need to test a lot of different browsers, but downloading and installing them all on your system is difficult. Configuring all these browsers as you need them configured adds additional steps. You can avoid all this pain by accessing the browser through the environment provided by Spoon.net. To use this product, you install a plug-in for your browser and then choose the browser you want to use, as shown in Figure 10-5. The browser selections aren’t limited to those that your platform would normally support. For example, even if you’re using a Windows system, you can load Safari or Firefox Mobile to perform required testing.

Figure 10-5. Spoon.net makes it possible to use any of the most common browsers

Using Other Vendors’ Sandboxes

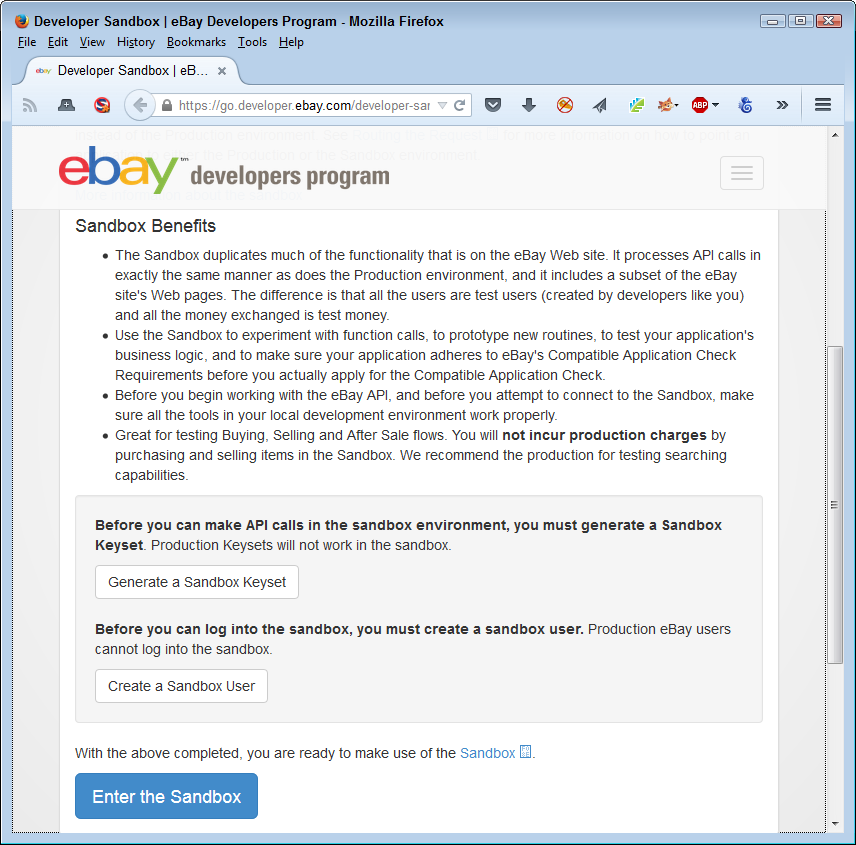

There are situations where you use a sandbox whether you want to or not. For example, when writing an application that uses the eBay API, you must first use the sandbox to write your application code and then test it. Only after eBay certifies the application can you run it in the production environment. Because of the high risks involved in the API environment, you will likely find that you spend considerably more time using third-party sandboxes to test your code.

Access to most of these sandboxes relies on specialized keys. Vendors, such as eBay, want to know who is using their sandbox and for what purpose. The key uniquely identifies you and you must have it in order to make a sandbox call. When working with eBay, it’s easy to get the key, create a user account, and then enter the sandbox to begin performing application testing, as shown in Figure 10-6.

Figure 10-6. Most vendors will require some sort of access control to use their sandbox

A problem can occur when you need to use multiple APIs in your application and each of these APIs has its own sandbox environment. Trying to get the application certified means getting each of the vendors to sign off on it. Make sure you create a plan for getting your application signed off by each of the vendors before you begin coding. In some cases, you may have to break your application into separately testable pieces in order to gain the approval you need.

Note

The use of multiple APIs in a single application has become so common and so complex that many developers now turn to API aggregation for help. Using API aggregation makes it possible to reduce complexity by creating an API mashup. Working with API aggregation is well outside the scope of this book, but you can find some excellent information about it in “Api Aggregation: Why It Matters and Eight Different Models” and “Extending REST APIs with API Aggregator”. Of course, there are many other resources you can consult for information about aggregation, but these articles are good places to start.

Considering Virtual Environments

Sometimes your API requires a virtual environment in which to work. A virtual environment gives the feeling of being the real thing without letting the API do things that would cause problems. Throughout the chapter, you’ve seen comparisons between sandboxing and virtual environments. From a security perspective, both provide protection against hacker activity, but do it in a significantly different manner. However, the bottom line is always to separate the API, application, application components, or any other software item that you might want to isolate from the operating system. The isolation allows you to intercept and cleanse data, as well as keep the software under control so hackers do less damage. The following sections discuss virtual environments in more detail.

Defining the Virtual Environment

A virtual environment can refer to any software that provides the means to isolate other software. Think about it as you do a container, because that’s what it is. Previous sections of the chapter have described various kinds of virtual environments. However, this part of the chapter describes the kind of virtual environment you use for development purposes, rather than running an application as a user.

The basic reason to use virtualization is to isolate all or part of the development environment so that you can play with the application. Finding security issues truly does mean experimenting with the software in ways that you would never use in a standard operating system (especially not one connected to the network where your mistake could take down everyone).

Note

Some languages come with their own virtual environment tools. For example, Python users have a number of tools for creating virtual environments at their disposal. These tools make it easier to set up and configure specific environments for specific languages. You can read about the Python offerings at http://docs.python-guide.org/en/latest/dev/virtualenvs/. The point is to look for language-specific tools whenever possible to create virtual environments designed to work with that language.

Virtual environments can also include so much more than a sandbox does. It’s possible to create virtual environments with specific operating systems, development tools, application setups, and browsers. The virtual environment emulates every part of the development experience so that you can create an Apache server setup using one virtual environment and an IIS server setup using another. Both virtual environments can exist on the same machine without any problems with conflicts.

Differentiating Virtual Environments and Sandboxing

Virtual environments and sandboxes have many similarities. The rest of the chapter has described the most common similarities, such as keeping your API safe. The basic differences between most virtual environments and sandboxing are that virtual environments are:

- Repeatable

- When you move the virtual environment file to another system, that system runs the virtual environment precisely as it would run on the original system. What this means is that every developer sees the application in the same way, using a prescribed development environment, so the results seen on one system are repeatable on another system. Differences between setups make it hard (sometimes impossible) to verify the presence of security issues.

- Movable

- Depending on the virtualization software you use, you could move the virtual environment just about anywhere. As long as the developer receiving the virtual environment file has the correct software, it’s possible to re-create the precise virtual environment needed to work with the project.

- Recoverable

- Virtual development environments rely on a special kind of file that defines how to create the required emulation. If your experiments cause the virtual environment to crash, all you need to do is close that copy of the virtual environment and start another. Recovery takes only as long as needed for the software to load, which may be just a few seconds.

- Re-creatable

- There are times when you need multiple copies of the same project running on your system. You can create as many copies of a virtual environment as needed for your purposes. The special nature of virtual environments means that every copy you create will begin with precisely the same resources, software loaded, environment, and so on. Consequently, every copy is a clone of every other copy on your system.

Implementing Virtualization

One of the more interesting virtual development environments is Vagrant. This particular product runs on any Windows, OS X, or common Linux system (there are versions of Linux that don’t work with Vagrant, so be sure to check the list to be sure Vagrant supports your Linux distribution). To use this product, you install it on your system, configure the kind of environment you want to use for development purposes, and place the resulting file with your project code. Any time you want to start up the development environment you need for a particular project, you simply issue the vagrant up command and it configures the correct environment for you. The product will create the same environment no matter where you move the project files, so you can create a single environment for everyone on your development team to use. Vagrant is a better choice for the individual developer or a small company—it’s inexpensive and easy to use.

Another useful virtual environment product is Puppet. This product relies on VMware, with Puppet performing the management tasks. The combination of Puppet and VMware is better suited toward the enterprise environment because VMware comes with such a huge list of tools you can use with it and it also provides support for larger setups.

Relying on Application Virtualization

All sorts of virtual environments exist to meet just about any need you can think of. For example, Cameo makes it possible to shrink any application down into a single executable (.exe file) that you can copy to any Windows machine and simply run without any installation. If you need to support other platforms, you can copy the application to the Cameo cloud servers and execute it from there.

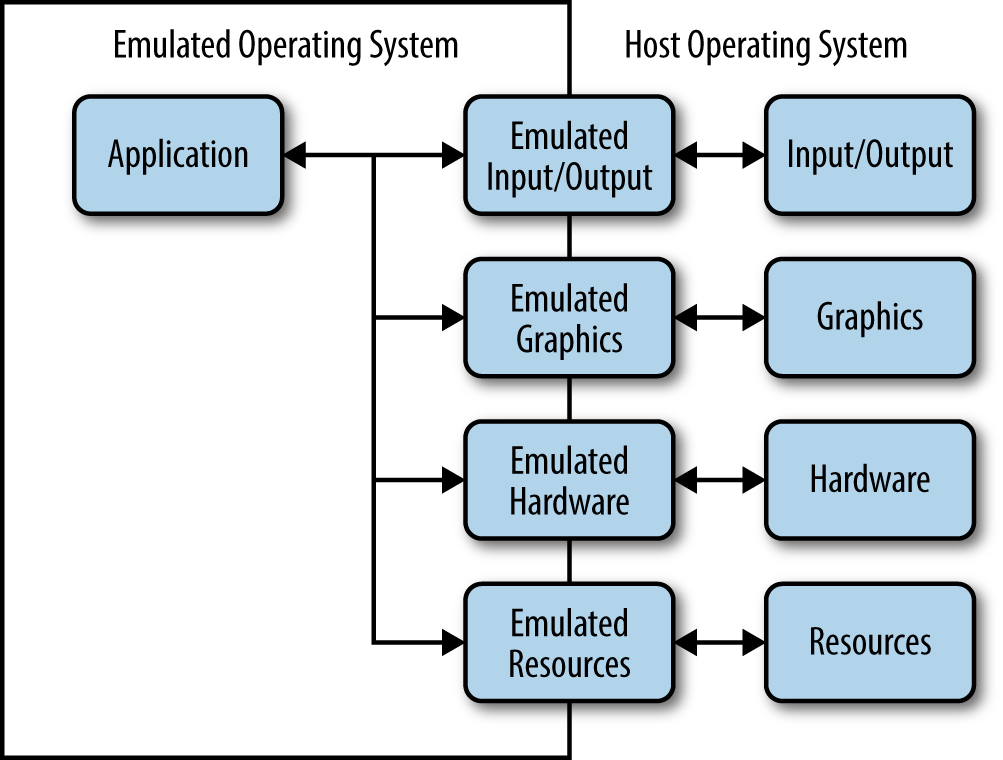

Application virtualization is a packaging solution. You create a virtual environment that specifically meets the need of just that application. Figure 10-7 shows how the virtual application environment might appear. As far as the application is concerned, it’s operating in its native environment, even though it’s using a completely different operating system to perform tasks.

Figure 10-7. Application virtualization is a kind of packaging technology

Another product that provides an application virtual environment is Evalaze. This product emphasizes the sandbox environment it provides along with the application virtualization. You can use it to run an application from all sorts of places, including memory sticks. This is a great solution to use if your application requires a specific browser and you want to be sure that the user’s environment is configured correctly.

Researching an appropriate kind of virtualization will take time and you need to pursue your research with an open mind. Some of those odd-looking solutions out there may be precisely what you need to create a secure environment for your application.