Chapter 11. Checking Libraries and APIs for Holes

Before you can know that a particular piece of software will behave in a particular way, you need to test it. Yes, you do have a specification and you created the code in accordance with that specification. You even debugged the code to ensure that there aren’t any obvious errors in it. However, you still don’t know that the code will function as originally intended until you perform some level of testing on it. Testing ensures that software behaves as you expect it should.

This chapter does discuss testing in the traditional sense, but it also views nontraditional sorts of testing. A standard testing suite will provide specific inputs and then validate the expected outputs. However, the real world doesn’t always provide the kind of input that libraries and APIs expect, so it’s important to test that sort of input as well. Of course, when you test in this manner, you don’t know what to expect as output. The library or API design must contain functionality that helps with recovery from errant input so that the system doesn’t crash, but you don’t know whether this functionality is even present until you perform the required level of testing.

Testing can and should happen at multiple levels. Unit testing, the testing of individual pieces of code, comes first. A developer begins performing this sort of testing shortly after writing the first bits of code. Next comes integration testing as the application components are put together. Finally, the application is tested as a whole with all of the completed software in place. All these levels of testing (and more) require security testing as well—checking for unexpected inputs and determining whether the code acts in an acceptable manner. During this time, the developers also create a testing harness—test routines that automate the process of testing so that it becomes more reliable and consistent.

Each programming language can also have particular issues that developers must check. The final part of this chapter discusses how to check for specific programming language issues as you perform your security testing. Unlike other areas of testing, language-specific issues tend to revolve around security because hackers often look for these differences as the means for causing the application to crash in a specific manner or for logic errors that the hacker can employ to gain access. Tracking potential language flaws is just as important as tracking flaws in third-party libraries and APIs. You need to test every part of an application from every possible angle to ensure your application will behave in a predictable manner.

Creating a Testing Plan

Every testing scenario requires a testing plan. Although you want to test outside the box, you do need to have some sort of structured method to perform the testing. Otherwise, testing becomes inconsistent and incomplete. In order to perform a useful purpose, testing needs to be methodical, yet flexible enough to provide a capacity for additional tests as it becomes obvious you need them. With this in mind, the following sections help you define a testing plan from a development perspective.

Note

It’s important to note that testing plans often have a number of phases and orientations. Every stakeholder in an application development effort will want to perform some level of testing to ensure the application meets specific goals and objectives. These points of view could conflict, but in most cases, they merely augment each other. For example, a DBA may want to verify that the application interacts with the database in a manner that’s consistent with company guidelines.

Considering Goals and Objectives

Application testing can’t succeed unless the development team defines both goals and objectives for the testing. A goal is as simple as determining whether the application meets the technical and business requirements that an organization requires of it. An objective is to determine that the application can successfully perform a set of tasks within the business environment provided for it. For example, an objective might be to add new users to a database without causing errors, duplicating users, or leaving out essential information. The following sections discuss goals and objectives that testing must meet in order to provide a useful result.

Defining the goals

Goals define a condition that a person or entity intends to meet. You can set all sorts of goals for application testing, such as computing the precise value of pi within 42 picoseconds. Of course, the goal isn’t achievable because it isn’t possible to calculate a precise value for pi. Some organizations set the same sorts of goals for applications and are disenchanted when it becomes obvious that the testing process hasn’t achieved the goal. Real goals are accomplishable using the resources available within the time allotted.

In addition, a goal must define a measurement for success. It isn’t just a matter of knowing whether testing succeeded—it’s a matter of knowing how well testing succeeded. In order to obtain an answer to how well the testing proceeded, the goals you set must provide a measure that defines a range of expected outcomes, such as the application calculated the correct result within the given timeframe 99% of the time.

The precise goals you set for your application depends on what you expect from it and the time you have in which to implement the goals. However, it’s possible to generalize the goals under the following categories:

- Verification and validation

- The verification and validation process does bring faults to light. However, it also ensures the application provides the designed output given specific inputs. The software must work as defined by the specification. From a security perspective, you must test the software for both expected and unexpected inputs and verify that it responds correctly in each case.

- Priority coverage

- The most secure application in the world would have every function tested in every possible way. However, in the real world, time and budgetary constraints make it impossible to test an application fully. In order to test the software as fully as possible, you must perform profiling to determine where the software spends most of its time and focus your efforts there. However, other factors do come into play. Even if a feature isn’t used regularly, you may still have to give it higher coverage when it can’t fail (a failure would cause a catastrophic result). The prioritization of coverage must include factors that only your application possesses.

- Balanced

- The testing process must balance the written requirements, real-world limitations, and user expectations. When performing a test, you must verify that the results are repeatable and independent of the tester. Avoiding bias in the testing process is essential. It’s also possible that what the specification contains and what the users expect won’t match completely. Miscommunication (or sometimes no communication at all) prevents the specification from fully embracing the user’s view of what the application should do. As a result, you may also need to consider unwritten expectations as part of the testing process.

- Traceable

- Documenting the testing process fully is critical in repeating the testing process later. The documentation must describe both successes and failures. In addition, it must specify what was tested and how the testing team tested it. The documentation also includes testing harnesses and other tools that the team used to perform software testing. Without a complete set of everything the testing team used, it’s impossible to re-create the testing environment later.

- Deterministic

- The testing you perform shouldn’t be random. Any testing should test specific features of the software and you should know what those features are. In addition, the testing should show specific outcomes given specific inputs. The testing team should always know in advance precisely how the tests should work and define the outcomes they should provide so that errors are obvious.

Testing performance

Many people equate performance with speed, but performance encompasses more than simply speed. An application that is fast, but performs the task incorrectly, is useless. Likewise, an application that performs a task well, but makes the information it processes available to the wrong parties, is also useless. In order to perform well, an application must perform tasks reliably, securely, and quickly.

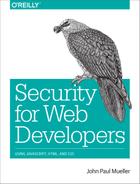

Each of these performance elements weighs against the others. Increasing security will necessarily make the application slower because the developer adds more code to perform security checks. Adding code makes the application run more slowly. Likewise, reliability will cause an application to slow because more checks are added in this case as well. Security checks can decrease application reliability by reducing risk at the expense of functionality—a reliable application is one that provides all the expected functionality in every given circumstance (it doesn’t fail). In short, all elements of performance work against each other, as shown in Figure 11-1.

Figure 11-1. Performance encompasses speed, reliability, and security

In order to test the performance of an application, you must verify the balance between speed, reliability, and security. Balanced applications perform well and don’t place a burden on the user, but still handle data reliably and efficiently.

Testing usability

Many testing scenarios fail to test usability. Determining how well the user can interact with the software is essential because the goal of software is to help users become more productive (whether those users are human or machine is immaterial). A confusing or otherwise unhelpful interface causes security issues by keeping the user from interacting with the software correctly. The testing process needs to consider the physical and emotional needs of the user in addition to the steps required to accomplish a task. For example, asking a colorblind user to click the red button may not obtain the desired result. Failing to differentiate the button in a manner other than color is almost certainly going to cause input problems that will eventually lead to security issues.

Warning

It’s easy to become complacent when performing testing steps. A user can typically rely on keyboard and mouse input as a minimum, so you need to test both. However, users may have a broader range of access options. For example, pressing a Control key combination may perform tasks in a manner different from just using standard keyboard keys, so you need to test this type of input as well. It’s not essential to test every kind of input in every possible situation, but you should know that the application is able to handle the various input types correctly.

Testing platform type

Software behaves differently depending on the platform used. Throughout the book, you’ve seen that users can and will use various kinds of devices to interact with any application you create. It isn’t possible to test your application on every conceivable platform because some platforms aren’t even available at the time of testing. Consequently, you must create platform types—devices that fall into specific categories depending on capabilities and features. For example, you may be able to group smartphones into two or three categories depending on the functionality that your application provides.

Note

An organization is unlikely to know every type of device that users rely upon to perform work-related tasks. It’s important to perform a survey during the application design process to obtain a list of potential user devices. You can use this list when creating testing scenarios for specific device types.

When working through platform-type issues, it’s especially important to look at how devices differ both physically and in the way in which the interface works. Differences in the level of standardization for the browser can make a big difference as well. Any issue that would tend to cause your application to work differently on the alternative platform is a test topic. You need to ensure that these differences don’t cause the application to behave in a manner that you hadn’t expected.

Implementing testing principles

A testing principle is a guideline that you can apply to all forms of testing. Principles affect every aspect of application testing and are found at every level. When you perform API unit testing, you apply the same principles as when you test the application as a whole during integration testing. The following principles are common to testing of all sorts:

- Making the software fail

- The objective of testing is to cause the application to fail. If you test the application to see it succeed, then you’ll never find the errors within the application. The testing process should expose as many errors as possible, because hackers will most definitely look for errors to exploit. The errors you don’t find are the errors that the hacker will use against you.

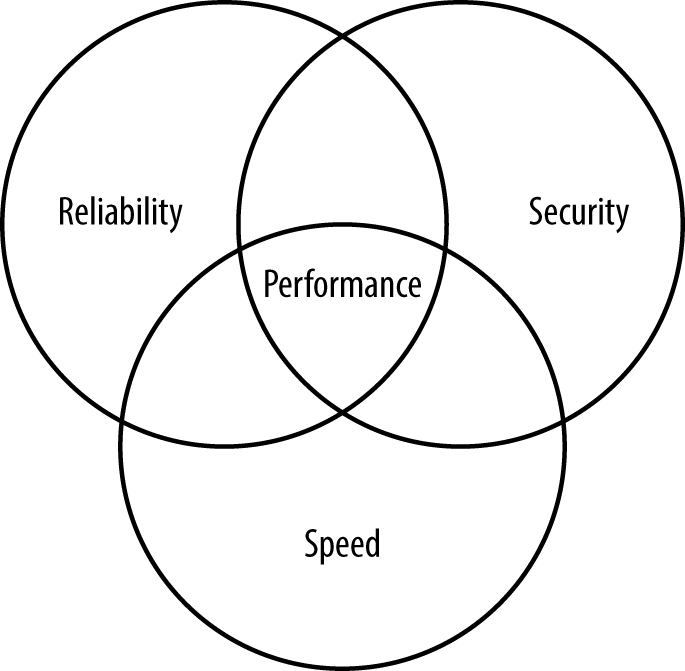

- Testing early

- The sooner you find an error, the lower the cost of fixing it. The cost of fixing a bug increases with time, as shown in Figure 11-2. The more each bug costs to fix and the later you find each bug, the fewer bugs you can fix due to cost and time considerations and the less secure the application becomes.

-

Figure 11-2. Finding bugs early leaves more time and money to find additional bugs

- Making testing context dependent

- The context of an application helps determine how you test it. For example, an application used for a safety-critical need requires different testing than an application used for an ecommerce site. The development approach also affects the testing context. An application developed using the waterfall approach requires different testing than an application that relies on the agile approach. Using the correct testing context helps improve application security by making it more likely that you’ll find the bugs most likely to cause problems.

- Creating effective test cases

- The more complete and precise you can make the test cases, the more effective the testing becomes and the better the potential security becomes. The test cases must include both user and application architecture requirements. Each test case consists of the precise input to the application code and a description of the exact output expected because of the input. It’s essential that inputs and outputs use measurable quantities to avoid ambiguity.

- Reviewing test cases regularly

- Using the same test cases repeatedly creates a test harness that eventually fails to find errors. It’s essential to review test cases as potential application issues become known so that the tests continue to push the application harder and find more bugs. As part of the review process, you should also perform exploratory testing to locate potential bugs that no one has thought about yet, no user has stumbled upon, and no hacker has exploited.

- Using a variety of testers

- Some organizations rely on different testers during test phases, such as release, acceptance, integration, and unit testing. Using level testing does work, but employing a variety of testers throughout the development process will yield better results. For example, relying on users to help test during the early application stages could help locate security issues in interface design at a time when they’re easy and inexpensive to fix.

- Performing both static and dynamic testing

- Using static testing probes application depth and demonstrates the developer’s understanding of the problem domain and data structure. Using dynamic testing probes application breadth and reveals the application’s ability to handle extremes of input. Using both static and dynamic testing helps ensure that the testing process yields as many bugs as possible within the allotted timeframe.

- Looking for defect clusters

- Errors tend to occur in clusters. The probability of finding errors in a particular code segment is directly proportional to the number of errors already found in that code segment.

- Performing test evaluation

- Each test case requires evaluation on completion to determine its success or failure. When the number of test cases are low or of a critical nature, you rely on human inspectors. When the number of test cases is high, you must include automated inspection in addition to the human inspector.

- Avoiding the error absence myth

- Just because an application runs with no detectible errors doesn’t mean that it’s error free. Applications can have all sorts of nontestable errors, such as an inability to meet user needs. In addition, tests can only check what the developer created them to check. A test may not find an error simply because it doesn’t test for it. Applications generally have errors, many of which are undetectable.

- Ending the testing process

- Theoretically you can continuously test an application looking for errors (and continue to find them). However, testing normally comes to an end at some point that is based on the combination of money, time, and software quality. When the risk of using an application becomes low enough and users agree that the application is usable enough, the testing process normally stops even though there are still issues to consider. As a consequence, any piece of software you employ for any purpose likely contains errors that will pose security risks.

Understanding testing limitations

Testing can’t provide you with an absolute picture of software performance. It can help you ascertain specific facts about the software, but not guarantee that the software won’t break. It’s essential to set realistic expectations about the testing process and to perform that process understanding that the result is incomplete. Here are some limitations you need to consider:

- Testers aren’t clairvoyant

- Testing can only demonstrate the presence of errors, but never their absence. The testing process determines the presence of known issues. A tester can’t test for unknown or undiscovered issues.

- Testing isn’t a decision-making tool

- Testing can only help you determine the state of the software. It can’t help you determine whether the software is safe to use or whether you should release it with some bugs in place.

- Users will find an environment that doesn’t work

- Testing only makes it possible to determine that the software will work reasonably well in a specific environment. If a user installs the software in an environment with different conditions, the software could fail. In fact, any change to the environment you create for the software could cause failures that you couldn’t find during testing.

- Root causes are invisible to testing

- Testing is about determining the effect of a failure given a specific input—it doesn’t tell you the original source that caused the failure in the first place. All you know after the testing process is that a failure exists; you must determine where it came from.

Testing Internal Libraries

When testing internal libraries—those that you control and own—you have access to the source code and can perform unit testing on each of the elements before you even put the library together. This approach gives you additional control over the testing process, lets you test and fix bugs when the costs are lower, and ensures you can perform both static and dynamic testing in order to locate potential problems with greater efficiency.

Of course, the fact that you own the code also means that you’re writing the library at the same time as the rest of the application. Other developers will want to perform testing as well. What this means is that you must employ mocking, as described in Chapter 10, to ensure that development can progress as anticipated. As you perform individual unit testing and are certain that the library elements work as anticipated, you can replace the mocked elements with real elements.

As part of the testing process, you can also create a testing harness for the library as described in “Creating a Test Harness for Libraries”. However, instead of creating the whole test harness at once, you create it a piece at a time as the real library elements become available. Creating the test harness in this manner will help you keep track of how library elements are interacting with the application and make changes as needed (when the cost of doing so is low).

Testing Internal APIs

As with internal libraries, you own the code for an internal API. Because an API isn’t part of the application—it runs in a different process—you need to create a server setup for interacting with the API. However, you won’t want to use a production server for the task because the code you create will have all sorts of issues. It pays to configure the application such that you can change just one configuration item to point the application to the production API once you release the API.

Any API you create will also need to rely on mocking so that application developers can begin writing the application code while you continue to work on the API. As the real code becomes available, you need to replace the mocked elements with real elements. It pays to develop the whole set of test scripts for an API at the outset using the techniques found in “Creating Testing Scripts for APIs”, realizing that the mocked elements will provide canned responses. In fact, the canned responses will clue you in as to which elements are still mocked.

It’s essential to test your internal APIs using the same criteria as the external APIs and to configure the testing and development environments to match your production environment. Otherwise, you could end up with a situation where an internal API actually becomes a pathway for a hacker to gain access to your network. Even disconnected software is subject to various kinds of hacks (as described in previous chapters).

Testing External Libraries

An external library (including frameworks and all sorts of other library-like coding structures) is one that someone else owns. The library is complete before you even begin writing your application and theoretically, the third party tests and maintains the library code. However, the library is simply a black box in most respects. Your ability to perform a full static test is limited to the public-facing modules that the third party makes available. Due to the complexities of working with most third-party libraries, a full static test is out of the question, which leaves dynamic testing.

Before you begin writing your application, during the proposal and design stages, you need to ensure any third-party library you choose is safe and fully meets the criteria for your application. The most popular libraries provide you with a test harness or you can find a third-party test harness for them. However, when working with a smaller, less known library, you need to set up testing yourself.

Warning

It would be easy to assume that just because a library, framework, API, or microservice is popular that it’s automatically safe to use. Even with such well-known products as jQuery, you can find security issues on sites such as http://www.cvedetails.com/vulnerability-list/vendor_id-6538/Jquery.html. In addition, even if the product is supposedly safe, using it incorrectly can cause all sorts of security issues. You need to review articles such as “How to Safely and Wisely use jQuery: Several Key Issues” to discover the issues that could cause you problems later. Every piece of code has vulnerabilities, every piece of code has usage issues, every piece of code is unsafe—just keep repeating these three phrases to yourself and you’ll be all right.

Testing External APIs

External APIs are popular precisely because someone else owns the code and it doesn’t even run on the local system. You won’t download the code or do anything with it except to make calls. The siren call of external APIs lulls even the careful developer into a false sense of security. Previous chapters have told you all about the terrifying potential for APIs to cause you woe. If anything, you need to script tests for external APIs with even greater care than any other code you use because unlike external libraries (and by extension, frameworks) you won’t ever see the code. There is no possibility whatsoever of performing a static test so your dynamic tests had better run the API through its courses before you make a decision about using it.

Unlike libraries, it’s unlikely that you’ll find a ready-made scripting suite for an API. In order to verify that the API works as anticipated, you really do need to create a scripting setup and send inputs of all sorts to the API. It’s essential to track the responses you receive, especially to errant inputs. You don’t know how an API will respond to errant inputs. Consequently, you don’t know how to code your application to react to errant input feedback. In other words, you need to know how the API will react when it receives data that is out of range or potentially of the wrong type.

The assumption of most developers is that the errant input will come from application users. However, errant input to the API can come from a botched man-in-the-middle attack or from other sorts of hacks. The errant input could also come from other sources on your system that reflects some type of infection or other problem. By being aware of how an API reacts to errant input, you can create a sort of security indicator that tells you something is wrong. Consider it a canary in the mine strategy. Errant inputs don’t just happen in most cases—there is a cause and knowing the kind of errant input that provides an unexpected response can provide clues as to the source of an issue.

Extending Testing to Microservices

You test microservices using the same techniques as you do APIs. As with APIs, you only have the ability to perform dynamic testing unless you happen to own the microservice code. In addition, it’s essential to track responses to unexpected data inputs, especially when you plan to use multiple microservices to perform the same task (with the alternatives providing backup to a main microservice that you select). The responses you receive may vary between microservices, which will mean your error handling code becomes trickier.

The biggest issue to consider with microservices, however, is that the developer purposely keeps microservices small. You can’t test the most commonly used features because every feature is commonly used. In short, your testing scripts must now test every microservice fully, which could add a burden to the testing group.

Testing Libraries and APIs Individually

The first level of testing generally works with libraries and APIs individually. The testing process for microservices is similar to APIs, except you don’t need a complex test harness because microservices are decidedly simpler than APIs. The following sections describe strategies you can use when unit testing both libraries and APIs (and, by extension, microservices). It’s important to note that you can test APIs and microservices either directly or as part of an API virtualization layer.

Creating a Test Harness for Libraries

A test harness is a set of instructions within the application code or as part of a special addition to the code that performs various tests. Because libraries exist as part of the application, the instructions for testing the library also appear as part of the application.

Test instructions normally appear in debug code as some sort of assert() function, or by making use of logging or screen outputs. JavaScript lacks an assert() function (there is talk of adding one). However, you can use the error object to create an assert-like function that provides the same sort of information. In using an assert() setup, you create assertions in the code that look something like this:

assert(typeof myArg === "string");

The assert() function would look something like this:

function assert(condition, message)

{

if (!condition)

{

message = message || "Assertion failed";

if (typeof Error !== "undefined")

{

throw new Error(message);

}

else

{

throw message;

}

}

}

In this case, when the value of an argument or some other code condition fails, the test ends with an error. You can choose to log the error or work with it in other ways, but you know the test failed. Testing the condition isn’t a problem with any browser. However, you may find different browsers support the error object in different ways, so simply throwing the message (rather than re-throwing the error object) is a good fallback position.

The in-code element does perform tests, but you still need input for those tests. To obtain this part of the puzzle, you normally need to employ scripted manual testing, which is always error prone, or a third-party product to script the required inputs. The tests you run against the library will tell you precisely how well the library meets the requirements of your application.

Creating Testing Scripts for APIs

API support consists of making calls. It’s possible to test an API without even using the application. All you need is a script that makes calls and checks responses. A number of third-party products perform this task or you can create a simple application to perform the testing manually. Using a script ensures you get the same testing results each time, so using a scripting product is usually the best choice. Any test you create should check for these conditions as a minimum:

- Range

- Responds correctly within its range and provides a correct error response when values are either too high or low.

- Type

- Verifies that the user supplies the right data type as input and provides a correct error response when the input is of the wrong type.

- Size

- Validates the length of the data so that it’s not possible for someone to send a script instead of the expected string.

- Characters

- Tests for invalid characters within the input to ensure the user can’t send control or other incorrect characters as part of the input.

After you start using the API from the application, you need to perform integration testing, which consists of providing inputs to the application and then requiring the application to make the required calls. Again, you can use a scripting product to make this task easier.

Extending Testing Strategies to Microservices

As with APIs, you want to use some type of scripting product to make calls and check responses when working with a microservice. However, you need to ensure that the microservice is checked thoroughly because each one represents a separate piece of code. It’s not possible to make assumptions about a microservice in the same way that you can with an API.

When you do perform integration testing, you need to determine the performance profile of the application. Every microservice should receive at least one test. However, microservices you plan to use more often should receive more testing. The purpose of this strategy is to verify code that has a higher probability of causing problems and to keep testing costs lower.

Developing Response Strategies

The focus of all testing is on the response provided by the library, API, or microservice to a given input. Unless the code reacts in the proper manner, the application won’t work as originally envisioned. More importantly, hackers look for discrepancies in behavior to exploit. When defining responses, you must consider two response types: direct and mocked. The following sections discuss each response type.

Relying on direct results

A direct response comes from the active library, API, or microservice. In this case, you obtain an actual response to the input provided. If the code under test is working correctly, the response you receive should precisely match the specifications defining the test cases. The direct results actually test the code you plan to use with your application.

Relying on mocked results

Mocked results come from mocking software that simulates the library, API, or microservice. Using mocked results lets you start working on the application and testing it before the library, API, or microservice code is ready to use. Using this approach saves time and allows development to progress much faster.

However, there is another consideration. You can use mocking to test the viability of your testing harness for a library or testing scripts for an API. Because you already know that the mocking software will provide a precise response for a given input, you can validate that the testing software is working as anticipated. It doesn’t pay to perform a test unless you can count on the testing software to perform the task correctly.

Performing Integration Testing

Once you have tested the individual elements of an application for issues, you begin integrating the actual libraries, APIs, and microservices into the application. The easiest, most complete, and least complex method of integration testing is to use a phased approach where libraries, APIs, and microservices are added to the application in small groups in an orderly manner. The use of phased integration testing helps you locate and fix problems quickly. Transitioning an application from mocked data to real data one piece at a time may seem time consuming at first, but the process does make it possible to locate errors quickly, ultimately saving a lot of time. The goal of integration testing is to create a completed application that works as anticipated and doesn’t contain any security holes.

Note

It’s never possible to create a bulletproof application. Every application will contain flaws and potential security holes. Testing does eliminate the most obvious issues and you need to test (and retest) every change made to any part of the application because security holes appear in the oddest places. However, never become complacent in thinking that you’ve found every possible problem in the application—a hacker will almost certainly come along and show you differently.

Developers have come to rely on a number of integration testing models. Some of these models are designed to get the application up and running as quickly as possible, but really only accomplish their task when nothing goes wrong. Anyone who writes software knows that something always goes wrong, so the big bang model of integration testing will only cause problems and not allow you to check for security concerns completely. With this in mind, here are three testing models that use a phased approach and allow a better chance of locating security issues:

- Bottom up

- In this case, the development team adds and tests the lower-level features first. The advantage of this approach is that you can verify that you have a firm basis for applications that perform tasks such as monitoring. The raw source data becomes available earlier in the testing process, which makes the entire testing process more realistic.

- Top down

- Using top down means testing all of the high-level features first, checking first-level branches next, and working your way down to the lowest-level features. The advantage of this approach is that you can verify user interface features work as intended and that the application will meet user needs from the outset. This sort of testing works best with presentation applications, where user interactivity has a high precedence.

- Sandwich

- This is a combination of both bottom up and top down. It works best with applications that require some use of data sources to perform most tasks, but user interactivity is also of prime consideration. For example, you might use this approach with a CRM application to ensure the user interface presents data from a database correctly before moving on to other features.

Testing for Language-Specific Issues

A huge hole in some testing suites is the lack of tests for language-specific issues. These tests actually look for flaws in the way in which a language handles specific requests. The language may work precisely as designed, but a combination of factors works together to produce an incorrect or unexpected result. In some cases, the attack that occurs based on language deficiencies actually uses the language in a manner not originally anticipated by the language designers.

Every language has deficiencies. For example, with many languages, the issue of thread safety comes into place. When used without multithreading, the language works without error. However, when used with multithreading and only in some circumstances, the language suddenly falls short. It may produce an incorrect result or simply act in an unexpected manner. Far more insidious are deficiencies where the language apparently works correctly, but manages to provide hackers with information needed to infiltrate the system (such as transferring data between threads).

The following sections describe the most common language-specific issues that you need to consider testing for your application. In this case, you find deficiencies for HTML5, CSS3, and JavaScript—languages commonly used for web applications. However, if you use other languages for your application, then you need to check for deficiencies in those languages as well.

Note

Many testing suites check for correct outputs given a specific input. In addition, they might perform range checks to ensure the application behaves correctly within the range of values it should accept and provides proper error feedback when values are out of range. The reason that most test suites don’t check for language deficiencies is that this issue is more security-related than just about anything else you test. When testing for language-specific issues, what you really look for is the effect of deficiencies on the security of your application.

Devising Tests for HTML Issues

When working with HTML, you need to consider that the language provides the basic user interface and that it also provides the avenue where many user-specific security issues will take place. With this in mind, you need to ensure that the HTML used to present information your application manages is tested to ensure it will work with a wide variety of browsers. With this in mind, here are some language-specific issues to consider:

-

The HTML is well formed and doesn’t rely on tags or attributes that aren’t supported by most browsers.

-

The document is encoded correctly.

-

Any code within the document performs required error handling and checks for correct input.

-

The document output looks as expected when provided with specific inputs.

-

Selection of user interface elements reduces the potential for confusion and errant input.

Note

There are many tools available for HTML testing. Two of the better products are Rational Functional Tester and Selenium. Both products automate HTML testing and both provide the record/playback method of script creation for performing tests. Rational Functional Tester, a product from IBM, also features specialized testing strategies, such as storyboarding. If you need to perform a manual check of a new technique, try the W3C Markup Validation Service at https://validator.w3.org/dev/tests/. The site provides HTML-version-specific tests you can use.

Part of HTML testing is to ensure all your links work as intended and that your HTML is well formed. Products such as WebLight automate the task of checking your links. A similar product is LinkTiger. The two products both check for broken links, but each provides additional capabilities that you may need in your testing, so it’s a good idea to view the specifications for both.

Devising Tests for CSS Issues

The original intent for CSS was to create a means for formatting content that didn’t involve the use of tables and other tricks. The problem with these tricks is that no one used a standard approach, and the tricks tended to make the page unusable for people with special needs. However, CSS has moved on from simple formatting. People have found ways to create special effects with CSS. In addition, CSS now almost provides a certain level of coding functionality. As a result, it has become important to test CSS just as fully as you do any other part of the application. CSS has the potential for hiding security issues from view. With this in mind, you need to perform CSS-specific tests as part of the security testing for your application—it should meet the following criteria:

-

The CSS is well formed.

-

There aren’t any nonstandard elements in the code.

-

Special effects don’t cause accessibility problems.

-

The choice of colors, fonts, and other visual elements reflect best practice for people with special needs.

-

It’s possible to use an alternative CSS format when the user has special needs to address.

-

Given an event or particular user input, the CSS provides a consistent and repeatable output effect.

Note

As the uses for CSS increase, so does the need for good testing tools. If you’re a Node.js user, one of the better testing tools you can get is CSS Lint. You use CSS Lint for checking code. When you want to check appearance, you need another product that does screenshot comparisons, such as PhantomCSS. When the screenshot of your site changes in an unpredictable manner, PhantomCSS can help you identify the change and ferret out the cause. If you need a manual validator for checking a technique you want to use, rely on the W3C CSS Validation Service at https://jigsaw.w3.org/css-validator/.

Devising Tests for JavaScript Issues

JavaScript will provide most of the functional code for your application. With this in mind, you test JavaScript code using the same approach as you would other programming languages. You need to verify that for a given input, you get a specific output. Here are some issues you need to consider as part of your testing suite:

-

Ensure the code follows the standards.

-

Test the code using a full range of input types to ensure it can handle errant input without crashing.

-

Perform asynchronous testing to ensure that your application can handle responses that arrive after a nondeterministic interval.

-

Create test groups so that you can validate a number of assertions using the sample assertion code found in “Creating a Test Harness for Libraries” (or an

assert()provided as part of a test library). Test groups magnify the effect of using assertions for testing. -

Verify that the code is responsive.

-

Check application behavior to ensure that a sequence of steps produces a desired result.

-

Simulate failure conditions (such as the loss of a resource) to ensure the application degrades gracefully.

-

Perform any testing required to ensure the code isn’t susceptible to recent hacks that may not be fixed on the client system. Using a security-specific analyzer, such as VeraCode, can help you locate and fix bugs that might provide entry to hackers based on recently found security issues.

Note

The tool you use for testing JavaScript depends, in part, on the tools used for other sorts of testing the organization and the organization’s experience with other tools. In addition, you need to choose a tool that works well with other products you use with your application. Some organizations rely on QUnit for testing JavaScript because of the other suites (such as JQuery and JQuery UI) that the vendor produces. In some cases, an organization will use RhinoUnit to obtain Ant-based JavaScript Framework testing. Many professional developers like Jasmine coupled with Jasmine-species because the test suite works with behaviors quite well. If you’re working a lot with Node.js, you might also like to investigate the pairing of Vows.js and kyuri. Another Node.js developer favorite is Cucumis, which provides asynchronous testing functionality.

One of the issues you need to research as part of your specification and design stages is the availability of existing test suites. For example, the ECMAScript Language test262 site can provide you with some great insights into your application.