Chapter 13. Clearly Defining Upgrade Cycles

Your application is constantly exposed to threats online, and so is every other piece of code that your application relies on. In order to reduce the risk incurred by known threats, you need to perform upgrades to your application regularly. These upgrades help improve your application in several ways, all of which affect security:

-

Usability to reduce user mistakes

-

Outright coding errors

-

Speed enhancements that keep users from doing the unexpected

-

Fixes to functional code that reduce the potential for breaches

-

Fixes required to upgrade third-party libraries, APIs, and microservices

This chapter views the upgrade process from several levels. You can’t just make fixes willy-nilly and not expect to incur problems from various sources, most especially angry users. Upgrades require a certain amount of planning, testing, and then implementation. The following sections discuss all three levels of upgrades and help you create a plan that makes sense for your own applications.

Developing a Detailed Upgrade Cycle Plan

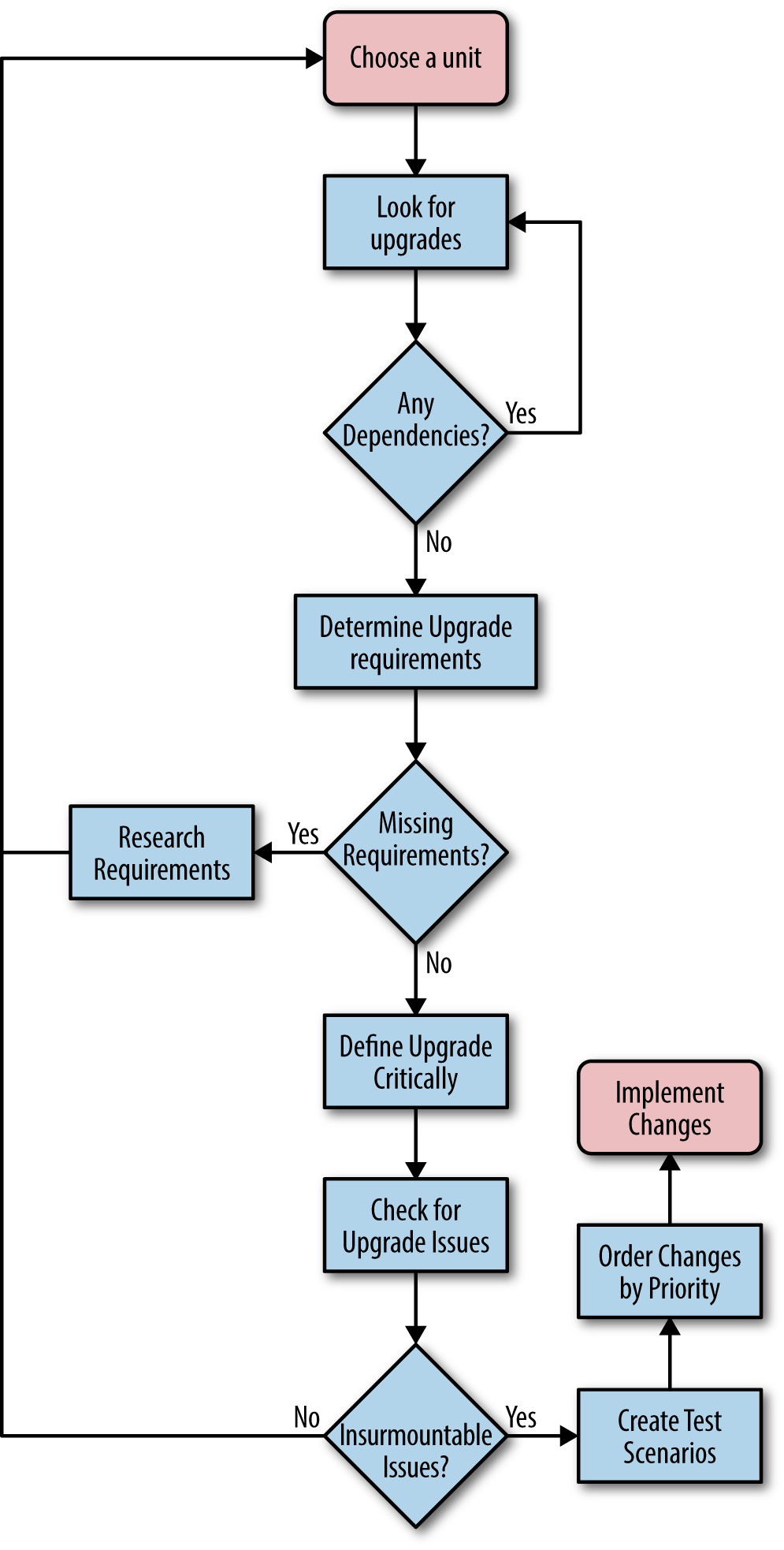

Part of the process for introducing upgrades to your application is creating a plan for implementing the changes. The problem is that you often don’t know about the upgrades needed for third-party software, don’t understand the requirements for creating the upgrade, can’t put the upgrades in any particular order, and then encounter problems with upgrade implementation plans. It’s essential to create an orderly way to evaluate updates, which is why you want to create an upgrade cycle plan. Figure 13-1 shows a process you can follow in performing this task.

Figure 13-1. Following an orderly process when creating an upgrade cycle plan saves time and money

The idea is to work through one unit at a time and ensure that you test everything associated with that unit. Even if you test a particular dependency as part of another unit test, you must also test it with the unit under observation because the observed unit might use the dependency in a different way or affect it in a different manner.

Now that you have an idea of what sort of process you can follow, you need details on how to perform the task. The following sections discuss the issues surrounding an upgrade cycle plan. After reading this section, you should have a better idea of how to create a plan that specifically meets the needs of your application.

Looking for Upgrades

The trouble tickets collected by support as the result of user complaints and system outages usually tell you what you need to know about upgrades for your own application code. If the trouble tickets don’t tell you everything needed, they at least provide enough information for you to perform the research required to discover precisely what upgrades you need to create. However, third-party application software is a different matter. Unless a developer or other interested party locates a fix for a problem as the result of debugging in-house code, an upgrade can remain invisible. It’s important to look for upgrades to third-party software and ensure you have a complete listing of them. Otherwise, you can’t maintain your application’s security state and the unknown risk potential for a security breach increases. Many organizations end up blindsided by the upgrade it didn’t realize it needed to make.

Warning

Some third parties offer automatic update notifications. The use of automatic notifications is one way to ensure you know about them, but you can’t depend on them. A notification tells you that an update is definitely available, but you must also be proactive in checking for the updates you didn’t hear about. Even if a vendor is studious about providing notifications, the notifications can still get lost or end up in a junk folder.

Checking the vendor site can tell you about upgrades you need to incorporate into your application when working with public libraries, APIs, and microservices. In many cases, vendors offer beta versions of upgrades so that you can begin working with them early. It pays to spend time reviewing precisely what the upgrade affects so that you know how much importance to attach to it with regard to your application. An upgrade that doesn’t affect any of the features your application uses is less important than an upgrade that affects all of the features your application uses. However, you should still incorporate the upgrade at some point, even if you’re sure your application is unaffected because upgrades often have dependency interactions that even the vendor doesn’t know about (or hasn’t fully tested).

Trade press articles and vendor press releases can also tell you about upcoming upgrades. In addition, you can keep your eyes peeled for articles that talk about any deficiencies in the product you’re using and the vendor plans for fixing them. All this information feeds into your upgrade plans. You get advance notice of what will likely happen so you can start thinking about it long before you have to do the work.

Don’t downplay the effects of personal communication when it comes time to upgrade. A vendor insider can often let you know about an upgrade before anyone else knows about it. Knowing about an upgrade in advance gives you a competitive advantage because you can prepare for the upgrade sooner than anyone else does. Time is a critical resource in the computer industry, and the company that frequently releases upgrades as soon as they’re needed is the company that keeps customers and attracts new ones. The ability to plan also reduces the stress on staff and makes it possible for everyone to create better upgrades (rushed upgrades can sometimes create more work than the problems they fix).

As you hear about needed upgrades (either for your own code or for code provided by a third party), you need to place the information about it on a list. Everyone in your development group should have access to the list and remain apprised of future upgrade requirements. Encourage your team to communicate about potential upgrades and the effect the upgrades will have on your application. Anything you can do to keep people thinking about upgrades and how to perform them will reduce the work you need to do later when time is critical.

Determining Upgrade Requirements

Knowing the specifics about an upgrade is a good first step. However, it isn’t good enough to start doing anything concrete about the upgrade. You must determine the requirements for making the upgrade. In some cases, an upgrade can pose the same problems in logistics that creating a new application can. Predicting how long a complex upgrade will take and how many resources it requires can become nearly impossible. The following list provides you with some idea of what to consider as part of an upgrade requirement specification:

- Determine the resource requirements

- Not all upgrades require additional resources—the surprising fact is that most do. Resources can include all sorts of things: memory, processing cycles, hard drive space, data sources, screen real estate, input types (such as sensors), network bandwidth, and so on. The list can become quite large and you need to consider it carefully because resource changes can have nasty side effects, such as the inability to run the application on a device that the user has relied upon in the past.

- Obtain any required platform changes

- Keeping an eye out for deprecated features is always a good idea. Deprecated features cause all sorts of problems because sometimes they exclude older platforms from consideration. You need to consider precisely how a platform change will affect users. Perhaps an upgrade excludes an older, but popular, operating system that the user loves. Rather than hearing endless complaints about the platform change, you need to learn about it and consider its effect on your organization, the application, and the users before starting the process of implementing it.

- Consider the time required to create, test, and deploy the upgrade

- The hardest upgrade requirement to consider is the time required to create, test, and deploy the upgrade. No matter how carefully you try to compute this requirement, it often falls short. Most people predict that they can accomplish the task in far less time than it will actually require. When determining this upgrade requirement, make sure you use realistic numbers and add time and resources for those unplanned emergencies that always occur in a software project.

-

Note

There are many causes of issues when trying to calculate a time requirement. One of the issues that you don’t see covered in books very often is the need to consider the human element. The humans on your team will have many tasks tugging at them as they work on the project. If they feel they can put your project off for a while to complete a more critical task, they’ll definitely do so. This is the procrastination factor and you need to deal with it in some positive way as part of your planning process. Unless the members of your team feel there is a criticality about your project, the procrastination factor will step in every time to cause you problems. The project you could complete on time suddenly becomes the project that is late, due entirely to the human factor you didn’t account for in your planning.

- Create a list of personnel and skills required to create the upgrade

- A common problem with upgrade projects is that the original planning didn’t include a list of personnel and skills required to accomplish it. The tendency is to think that a small subset of people or perhaps just one person can accomplish the upgrade without any problem. Unfortunately, this isn’t the case. An upgrade requires every bit of careful planning that a new project does. You need access to the same experts that the original project had in order to ensure the upgrade meets the same high standards.

-

Note

Upgrades often forget to include users as part of the team. As a result, the upgrade breaks user interfaces and causes other problems that a user would see quite quickly, but a developer will miss completely. Make sure you include all the required personnel as part of your upgrade process to ensure you end up with an upgrade that actually works and remains secure.

- Define the potential effect of the upgrade on data sources

- Upgrades can affect data sources in all sorts of ways. For example, you may find that you need to add additional fields to databases or you need access to an entirely new data source. The data source might be an input from a sensor or some other nontraditional information that your application now requires in order to function properly. Think about all of the inputs that the application could require as you consider the ramifications of an upgrade.

Unlike applications of old, you can no longer simply consider your application as part of the requirements list or the needs of your organization as the operating environment. Your upgrade requirements list will need to consider the use of third-party libraries, APIs, and microservices as part of the picture. In addition, you now need to consider the environments in which those pieces of your application run as part of the overall requirements list.

It’s also important not to forget your user in all this. When users relied on desktop systems, it was easy to create a controlled environment in which the user’s needs were easy to consider. Today, a user might try to use your application on a smartphone in the local restaurant. The application could see use while the user is the passenger (and hopefully not the driver) in a car or when the user is taking alternative transportation, such as a local train or bus. The upgrade requirements need to consider all sorts of devices used in all sorts of environments.

Defining Upgrade Criticality

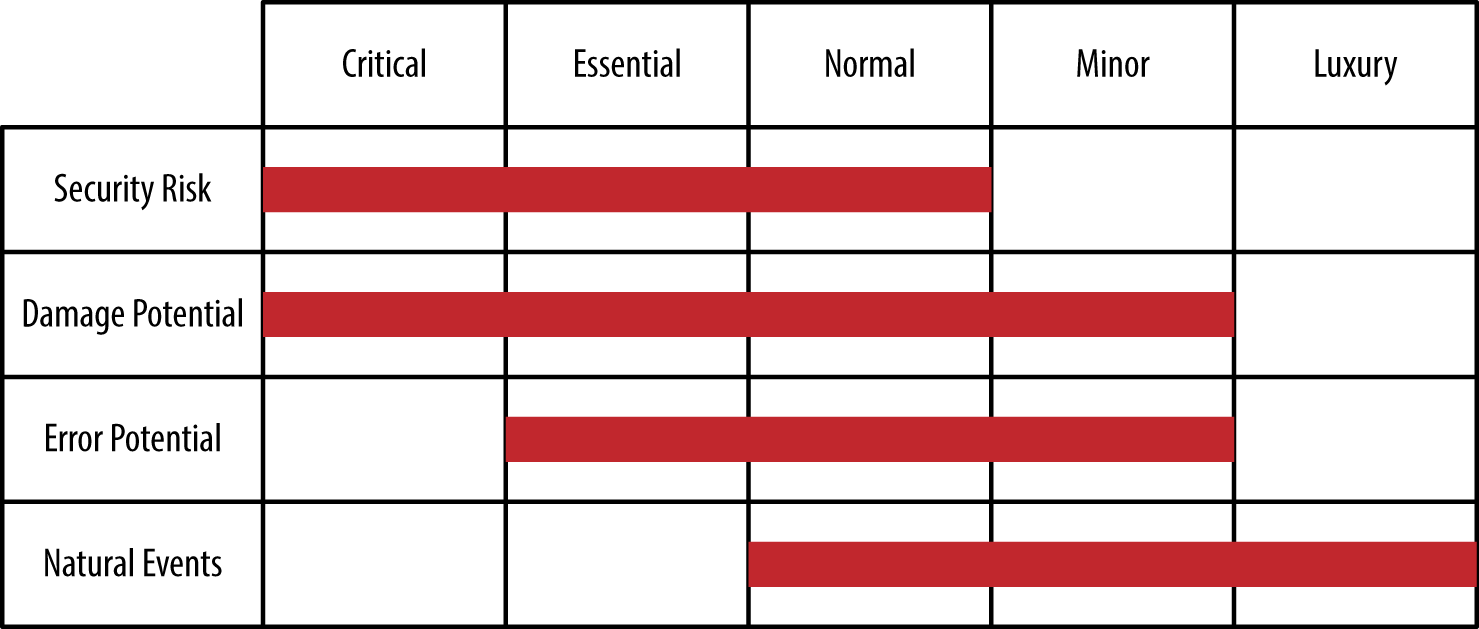

Upgrades affect applications in many ways and the risk of not providing an upgrade varies by application, platform, and need. The criticality of an upgrade is directly proportional to the risk not applying the upgrade presents. As an upgrade becomes more critical, its priority on your upgrade list increases. Part of the planning cycle involves the assignment of priorities to upgrades so that your organization applies the highest priority upgrades first. Otherwise, you can’t be sure that the upgrade process will truly represent a reduction in risk to your organization. When working through priorities, consider these criteria:

- Security risk

- Security upgrades always have a high priority because someone has already proven they provide some method of damaging your system. However, not all security upgrades represent an immediate risk because no known hacker uses the vulnerability for an attack or the attack requires a special condition, such as physical machine access. When prioritizing by security upgrade need, consider the amount of risk that the security issue imposes on your application.

- Damage potential

- Upgrades that fix a problem that could result in some sort of application or data damage usually rank high on the list of upgrades. Depending on the risk that a problem poses, upgrades that fix problems can supersede security upgrades in many cases. In this case, you must ascertain the probability that such damage will occur and the result of that damage.

- Error potential

- Errors created by user input or other problems can pose a significant risk, but you can also overcome many of these errors with additional user training or by implementing new company policies. Even so, you must assign a priority based on the probability of the error occurring, the damage that the error could cause, and the ability of the organization to overcome, catch, and correct the error.

- Natural events

- Some upgrades address the potential for natural events to cause application errors. The presence of line noise can cause single bit errors in a data stream, so one solution is to include error-correcting code (ECC) routines to root out and fix the single bit errors. In most cases, with the emergence of technology that automatically fixes the most egregious of these errors, you can give these issues a lower priority. You must still create upgrades to fix them, but the security issues that will definitely cause problems have to come first.

It’s essential to assign values to your priority list. These values make it easier to determine whether a change is critical (because it fixes a security hole) or is simply convenient (because it makes an interface change that a user requested that is more fit and finish than usability). Figure 13-2 shows the potential interplay between the various priority criteria when using a five-level priority system (your system may contain a different number of levels).

Figure 13-2. Balancing priorities is an essential part of the testing process

It’s important to update the priorities of upgrades that you need to create for your application constantly. As you create new change requirements, it’s important to increase the priorities of existing upgrades accordingly. Likewise, the addition of new change requirements may reduce the priority of some existing upgrades. In order for a listing of required upgrades to perform its designed purpose, you must keep it updated.

Checking Upgrades for Issues

Any time you make an upgrade of an existing product, there is a potential for compatibility or other issues to creep in unnoticed until the upgrade moves to the production environment. By that time, it’s really too late to do much about the issues except react to them and hope for the best. A better solution is to look for potential upgrade issues during testing, which means having a substantial testing group or relying on a third-party tester (see Chapter 12 for details). However, even before you get to the testing stage—even before the upgrade is implemented in any way—you can use various techniques to discover whether the upgrade will create issues. The following list describes a few of the more common techniques:

- Check the vendor site

- Vendors will often provide detailed write-ups of known issues with their products, including compatibility issues. In fact, in order to move a product forward sometimes, a vendor may purposely introduce a breaking change that will definitely cause problems for your application. Once you become aware of such issues, you need to consider whether the security and reliability implications of the upgrade are worth the new features obtained.

- Look through forums dedicated to the product or vendor

- In some cases, a vendor is either unaware of a breaking change or unwilling to admit it. Other users will tell you about potential breaking changes. Those odd error messages that keep popping up are telling you about a potential problem with the software. When you start seeing patterns in forum messages, you need to investigate the upgrade further before using it in your own application and suffering the same fate as others have.

- Read the trade press

- The worst possible breaking changes usually appear in the trade press somewhere. Expert developers who also have a writing career to support are always looking for product changes that make it nearly impossible to use the product correctly. In some cases, you even find workarounds for issues. When a breaking change appears in the trade press, you can be sure that most vendors are already working on a fix for the problem and it may be better to wait for the fix to appear, rather than implement the upgrade immediately.

- Perform testing directly on the new third-party code

- The use of testing harnesses and testing scripts (see Chapter 11) is an essential part of looking for potential issues. The tests may not turn up every problem, but when an issue is big enough, you can bet that testing will give you an indicator of the problem.

- Develop a test scenario for a subset of the functionality

- If you suspect a breaking change is in the code, but can’t find a definitive source of information about it, try creating a small test application that focuses on that particular feature. Creating a test application that runs just a part of the library, API, or microservice through its paces won’t take much time and will help considerably if you do find a problem. The test application can serve as a means for developing a workaround or detecting when the vendor fixes the issue.

- Obtain third-party expert input

- Some testing companies and many consultants can offer expert input on libraries, APIs, and microservices because they work with the code all day in a manner designed to break it. Spending all your work time hammering away at code definitely provides advantages that merely working with the code to build an application doesn’t provide.

Warning

Many organizations make the decision to introduce many changes as part of a single, consolidated upgrade package in the belief that a single upgrade is far better than multiple upgrades. It’s true that a single upgrade can be less disruptive when absolutely everything goes as planned. The fact of the matter is that things seldom go as planned and the use of multiple upgrades in a single package complicates the process of finding what has gone wrong. Using a phased approach to introducing change is always better. The production environment is usually going to present some issues that you didn’t see in the test environment, so phasing in changes helps you locate these new problems quickly so that you can squash them before they become a major problem.

It’s unlikely that you’ll find any third-party code update that is completely without issues. Any change to the code is likely to introduce bugs, breaking code changes, interface changes, design strategy changes, and all sorts of other issues that are simply unavoidable because change really does represent a two-sided coin containing the good changes on one side and the bad on the other. Flipping the coin often determines whether you end on the good side or the bad side of the changes. (Of course, coins also have an edge and some changes truly are neutral.)

At some point, you need to decide whether the issues you find are going to cause so many problems that the upgrade isn’t worth your time. When you decide that the upgrade isn’t worth the implementation time, you must also consider dependency issues. The code you rejected may affect some other upgraded code or your application in some manner that you can’t foresee without analysis. It pays to take your time and determine whether breaking issues really will cause enough pain to make the upgrade untenable. Calling off an application upgrade and waiting for fixes is preferable to releasing flawed software that will upset users and potentially cause security issues.

Creating Test Scenarios

Testing an upgrade does follow many of the same processes found in Chapter 11 and Chapter 12. However, the upgrade process demands that you perform some mandatory tests to ensure the upgrade works as expected. The use of test cases can help ensure that you test an upgrade fully before releasing it. The following list provides you with ideas on the sorts of test scenarios that you must include as part of the testing process for an upgrade:

- Trouble ticket content

- Every trouble ticket that your upgrade addresses should include enough information to create a test case. When this isn’t the case, you need to work with the developer responsible for researching a fix for the problem. Every bug you fix in an application (whether a coding error or some other noncoded problem) requires a test case to ensure you test the changed code completely.

- Action items

- Sometimes a problem doesn’t generate a trouble ticket because you can’t replicate the problem or you can’t fix the issue for other reasons (such as lack of code access). Even when you only suspect an issue, it’s important to try to create a test case to look for it. A coding change often makes an intermittent error become more visible, creating the potential for fixing it. However, you only find these opportunities through testing.

- Third-party code changes

- Every third-party code change should generate a specific test case for your application. You need to know that the third-party code change hasn’t affected your application in a negative way. Unfortunately, you often find these sorts of problems during integration testing unless you have a great test harness or set of test scripts for checking the third-party code.

- Environment and configuration changes

- All sorts of environment and configuration changes can cause problems. For example, a company policy may change how IT grants user access to resources. The change is a positive one because it keeps the resource more secure and reduces the access to the resource so the application runs faster. However, a lack of access can also spell trouble with users, so you need to ensure users can still access the resources they need. Other types of environment and configuration changes can have similar effects on the application, and you won’t know about it until after you perform the required testing.

Implementing the Changes

At this point, you’ve considered every element of an upgrade. The point of all this work is to ensure the upgrade:

-

Works as intended

-

Remains stable

-

Provides proper security

-

Improves reliability

-

Creates a great user interface

-

Seals any security breaches

The implementation process should begin with the highest-priority items on your list first, rather than trying to implement everything at once. A problem that many organizations face is that an upgrade becomes overwhelming. The changes often do take place, but at the expense of testing and ensuring the changes meet the specifications set for them. As a result, the upgrade ends up needing an upgrade. At some point, the code becomes so much spaghetti that no one understands fully and certainly that no one can secure. What you get is the kind of software that hackers love because it’s easy to overcome any defenses built into the software and easier still to hide the hack.

Creating an Upgrade Testing Schedule

At some point, you’ll have the coding for your upgrade started. You don’t want to wait until the process is too far along to start testing. It’s important to begin testing as soon as possible, especially when working with a third-party tester. The sooner you can find potential issues, the less costly and time consuming they are to fix. Consider using mocking so that you can perform upgrade testing as the features become available, rather than waiting for the upgrade as a whole due to dependencies. With this in mind, the following sections get you started with creating and implementing a testing schedule for your upgrade.

Performing the Required Pre-Testing

Once the upgrade process begins, you need to begin the testing process immediately. A lot of people wonder what the rush is, but most organizations run out of money before they run out of things to fix. In order to ensure testing takes its proper place, you need to start testing immediately. You must perform the following levels of testing during the upgrade coding process:

- Unit

- Make sure you test each change as you complete the coding. Otherwise, you can’t be sure that the code will even work. Using mocking helps make the testing process possible at this level.

- Dependency

- The changes you make will affect other code. Within reason, test dependencies in related code so that you can ease the way into integration testing with a reasonable chance of success.

- Configuration

- It’s important to ensure that configuration settings still provide the effect and level of flexibility that the various IT specialists expect. Otherwise, the application will fail during integration testing when you begin to configure it in various ways.

- Security

- You can’t simply assume that the repairs you made to your code will actually work as expected. Sometimes a security fix doesn’t actually fix the problem. You need to perform testing on the code that failed to determine whether the fix sealed the breach. In addition, you must make sure that the fix doesn’t actually open new holes.

-

Warning

Some developers take security testing to mean looking for holes in the code. Yes, that’s one sort of security testing. However, you must test all aspects of security. For example, a commonly missed level of security testing is to ensure that users end up in the proper roles and that they have the required levels of access. A manager performing a user-level task should be in a user role, rather than in a managerial role. A hacker can use role issues to gain access to the system at a higher privilege level than should be possible.

- Data connectivity

- Applications manage data. Otherwise, there isn’t much of a reason to create the application. Part of your testing must ensure that the unit under test can still connect to the required data sources and manage them successfully. It’s sometimes surprising to find that a fix to repair a security or other issue actually ends up making data inaccessible or damages the application’s ability to manage the data safely.

Performing the Required Integration Testing

As you put the upgrade together, you need to look for integration issues. Because you aren’t creating the code from scratch, integration issues can be trickier to find. You’re mixing new code that everyone has worked with recently with old code that no one has seen for a long time. The ability of the development staff to understand integration issues is less than when working exclusively with new code. As a result, you need to perform the kind of integration testing described in Chapter 11, but with an eye toward those interfaces between new and old code.

Note

It helps to have someone available who has actually worked with the old code and understands it fully. Given that people change jobs regularly, you might actually have to find a good candidate and hire them on as a consultant to help with issues that turn up in the older code. Hiring someone who is familiar with the old code will save a lot of time and effort trying to figure the old code out. In addition, someone who worked on the previous development team can fill in gaps as to why some code works as it does and why the team did things in a certain way. Documentation is supposed to provide this kind of information, but documentation is usually inadequate and poorly composed, so that sometimes it presents more questions than answers.

Be sure you test using your existing testing harness and scripts to ensure that the application still meets baseline requirements. You may have to perform updates on the testing harness and scripts to ensure they provide testing functionality for new features and remove testing for deprecated features. Maintain a change log for the changes you make to the testing harness and scripts. Otherwise, you might find it difficult to reverse changes later should one of your upgrades prove incorrect.

Moving an Upgrade to Production

Once the testing is finished and you’re certain that the upgrade will work as advertised, you need to move it to a production environment. If your organization is large, try moving the upgrade to just one group of users first so that if the users find an error, you can fix it without taking the entire organization offline. The important thing to remember is that the application must remain reliable and secure with the upgrade in place, yet provide the speed and interface experience the user requires. Otherwise, the upgrade will fail because users will refuse to use it. They’ll attempt to use the version that feels more comfortable to them, even if that version is likely to cause data breaches and other security issues.

Note

Part of the reason you want to employ users as testers is to ensure that they tell others about the new upgrade. When users get excited about an upgrade, you get a better response and it takes less time to get everyone started with the new product. Of course, you want to make sure that the tester experience is a good one.

From a security perspective, it’s often helpful to intrusion test an upgrade using a third-party tester. Yes, most people would say that you’re supposed to complete all of the required testing on the test server, and they’re right for the most part. However, intrusion testing doesn’t just check the application for errors. It also provides a sanity check on these items:

-

Network connectivity

-

Intrusion detection software

-

Intrusion prevention software

-

DMZ reliability

-

Required firmware updates for all hardware

-

Server setup

-

Required updates for all software

-

Application environment

-

Third-party libraries, APIs, and microservices

-

Application

-

User processes

-

Database connectivity

It simply isn’t possible to check all of these items using the test setup. For example, you can check the production server’s vulnerability to attack by using the test setup. Although it might seem as if some of these test issues are well outside the purview of moving an upgrade to production, any change to the server setup, including the application software, really does require such a test. The interactions between the various components make it impossible for you to know whether the server is still reliable and secure after the change. Unfortunately, many organizations fall down on the job in this area because no one seems to understand what has happened to the server setup. The bottom line is that the server could now be vulnerable and you wouldn’t even know it.

Testing the software isn’t the only thing you need to consider. It’s also important to get user feedback on interface changes. The user works with the application at a detailed level for many hours each day. It’s likely that the user will encounter potential security issues brought on by interface changes before the development staff does. In fact, experience shows that the development staff is often clueless that a particular change causes an issue that is completely obvious to application users. It isn’t that the development staff is insensitive or doesn’t do the job correctly—simply that the user has a completely different viewpoint on how the application should work.

Checking with administrators, DevOps, DBAs, and other skilled individuals is also a priority for an upgrade. You need to discover whether changes affect these specialized users in any negative way. For example, configuration changes that take too long to propagate through the system represent a potential security issue. If it takes 24 hours for a user deletion to take effect, a disgruntled user can cause all sorts of problems that would be hard to track. All it takes is one issue of this kind to cause an organization all sorts of woe, so ensuring the IT professionals in your organization can perform their job is an essential part of the upgrade.