Chapter 6. Asynchronous REST

Asynchronous operations might be one of the most complex aspects of RESTful architecture. Imagine performing a certain action on a resource that will take a considerable amount of time to finish. Should you leave the client to wait until the action has finished and you are able to return a meaningful HTTP code? In this chapter we will see what the best strategy is in situations like this one, and what codes your API should return when you want to tell the client that you will perform the operation at later time.

Asynchronous RESTful Operations

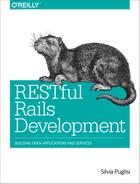

The HTTP protocol is synchronous. When an HTTP request is made to a server, the client expects an answer, whether it indicates success or failure (see Figure 6-1).

Figure 6-1. A simple REST request and response—the client has performed a POST request to a resource and the server has returned the 201 (Created) status code

Yet the fact that the server has returned an answer does not mean, per se, that the action or actions initiated by the request have to finish immediately. For example, you might request an operation that requires some time or resources to complete, and these might not be available at the moment the request is made.

This could very well be the case for a service that processes images or videos or audio files. In such a situation, the server usually accepts the request made by the client and agrees to perform the operation at a later stage.

This behavior differs slightly from creating or modifying a resource and returning a 201 code with a Created message or simply a 200. Therefore, we might be left asking ourselves the question: what code should the server return when agreeing to perform an action at a later time?

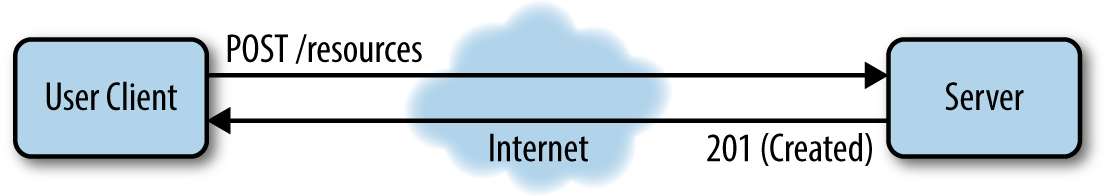

A common practice is to simply return a 202 HTTP code with an Accepted message (Figure 6-2). This tells the client that the request has been received and the server has accepted it, meaning there were no errors on the way when the request was passed. The server will also return a location that the client can retrieve to get the status of its request, among other things.

Figure 6-2. When a REST request is accepted to be performed later, the server sends a 202 (Accepted) status code and adds a location field so that the client can check the queue of processing resources

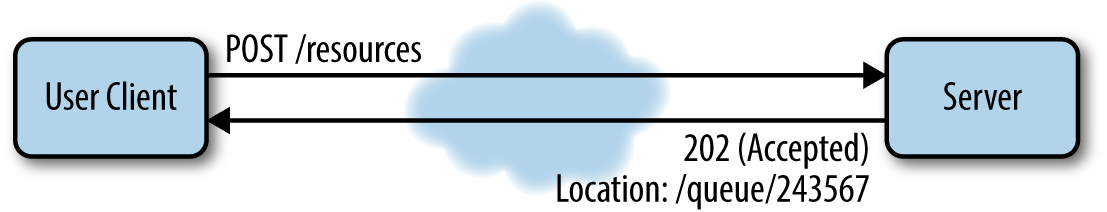

If the client retrieves the location returned to it, it might be able to perform different operations on the temporary resource, such as requesting that the operation be aborted (see Figure 6-3).

Figure 6-3. When the client retrieves the resource in the queue it will get its status and the list of actions that can be performed on the resource

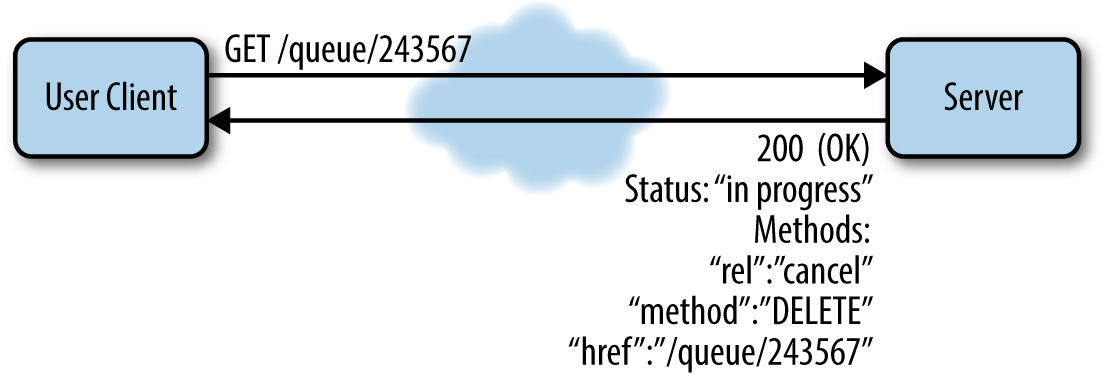

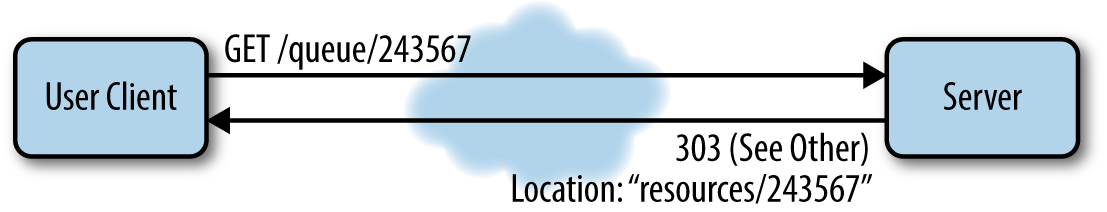

When the server has finished processing, it will update the queue and let the client know the resource has moved to a different location. It will also return a 303 HTTP code with the message “See Other” and the location of the processed resource (see Figure 6-4).

Figure 6-4. When the server has finished processing , it sends a 303 (See Other) status code with a location field specifying the permanent location of the resource

Asynchronous REST in Rails

Asynchronous REST is not difficult to understand in theory. We have seen what status code to return when a certain operation needs more time. But what happens in a Rails app when an operation needs to be performed later?

Rails Workers and Background Jobs

Operations that need to be completed later or in the background are usually performed by workers. Workers run processes that live outside of the application request/response cycle. These processes are usually called background jobs.

There are different solutions in Rails to manage background jobs. Here we will get started with Sidekiq, a multithreading library that lets us handle background jobs at the same time and in the same process.

We will create a service that receives an image and performs certain operations on it. The image is uploaded through an API call and stored on S3. We can generate our application as follows:

$rails-apinewlocalpic

Creating an Application Skeleton in Three Easy Steps

Let’s start by editing the Gemfile:

source'https://rubygems.org'gem'rails','4.1.8'gem'rails-api'gem'spring',:group=>:developmentgem'pg'gem'activerecord-postgis-adapter'# Serializer for JSONgem'active_model_serializers'gem'refile',require:['refile/rails','refile/image_processing']# To upload images to S3 with refile we need:gem'aws-sdk'gem'aws-sdk-v1'# Can be used together with v2# because of different namespaces.gem'mini_magick','~> 3.7.0'gem'sidekiq'gem'ohm'gem'ohm-contrib'

And let’s bundle:

$bundleinstall

Now we will start sketching the Picture model and the pictures controller.

In the first step we create the model through the Rails generator:

$rails-apigmodelpicturetitle:string

In the second step we create the controller:

$rails-apigcontrollerapi/v1/picturesindexshowcreateupdatedelete

In the third step we will just edit the routes to reflect the actions that we have just defined by adding the pictures resource:

namespace:apidonamespace:v1doresource:picturesdoget'index'endendend

This sets up the skeleton for our RESTful resource, pictures.

Uploading Images Through an API Call

In order to be able to process images in the background, we will have to be able to upload these images first.

We’ll now sketch an image uploader API by using Refile and storing our files on S3.

To begin, we need an S3 account. Please refer to http://aws.amazon.com/s3/ for detailed instructions on how to create an account.

Then we will configure the Refile gem to upload files to S3. Refile is a file upload library for Ruby (and Ruby on Rails) applications, designed to be simple and at the same time very powerful.

To upload any files to S3 we need to provide to our Rails app information regarding our Amazon AWS keys. We can add this information to our secrets.yml file in /config:

development:secret_key_base:<app_secret_key>s3_access_key_id:<s3_access_key_id>s3_secret:<s3_secret>s3_bucket:localpics3_region:eu-west-1test:secret_key_base:<app_secret_key>s3_access_key_id:aws-key-ids3_secret:aws-secrets3_bucket:localpics3_region:eu-west-1# Do not keep production secrets in the repository,# instead read values from the environment.production:secret_key_base:<%=ENV["SECRET_KEY_BASE"]%>s3_access_key_id:aws-key-ids3_secret:aws-secrets3_bucket:localpics3_region:eu-west-1

Remember not to upload your secrets.yml file to GitHub or any public repository. This is where you are storing your application secrets!

How to Exclude a File from a Git Repository

You can edit the .gitignore file to specify files and directories that Git needs to ignore.

For example, if you want to untrack secrets.yml, you just add it to .gitignore:

$echoconfig/secrets.yml>>.gitignore

The Git documentation contains many more examples.

The .gitignore file is uploaded to your repository though, and sometimes you may want to exclude some files without adding them to your global .gitignore.

Imagine for example that you have a very personalized .gitignore that you do not want to track in the Git repository. In that case, it is better to add .gitignore to .git/info/exclude. This is a special local file that works just like .gitignore but is not tracked by Git.

Please refer to this article on ignoring Git files for more insight on the topic.

When the app is started, Rails runs an initialize method. All the class ancestors are traversed, looking for those responding to an initializers method. The ancestors are then sorted by name and run.

We are going to define initializers for the AWS gem and the Refile gem. Here we will include the configuration and credentials needed to interact with AWS, and the basic configuration needed to save our pictures on S3:

# config/initializers/aws.rbrequire'aws-sdk'Aws.config[:stub_responses]=trueifRails.env.test?Aws.config[:credentials]=Aws::Credentials.new(Rails.application.secrets.s3_access_key_id,Rails.application.secrets.s3_secret)Aws.config[:region]=Rails.application.secrets.s3_regionAws.config[:log_level]=Rails.logger.levelAws.config[:logger]=Rails.logger

# config/initializers/refile.rbrequire'aws-sdk-v1'require"refile/backend/s3"# Here we read the secrets from secrets.ymlaws={access_key_id:Rails.application.secrets.s3_access_key_id,secret_access_key:Rails.application.secrets.s3_secret,bucket:Rails.application.secrets.s3_bucket,}Refile.cache=Refile::Backend::S3.new(prefix:"cache",**aws)Refile.store=Refile::Backend::S3.new(prefix:"store",**aws)

Now we can prepare our Picture model to have an image attachment. We create a migration as follows:

$railsgeneratemigrationadd_image_to_picturesimage_id:string

This will create a migration in db/migrate:

classAddImageToPictures<ActiveRecord::Migrationdefchangeadd_column:pictures,:image_id,:stringendend

We also have to specify in our Picture model that it has an attachment:

classPicture<ActiveRecord::Baseattachment:imageend

The last step is defining our pictures controller and all the actions that we need for our pictures resource.

We start by sketching an index, where we want the app API to return all the pictures created in the app. We use the same serializer mechanism we used earlier:

# GET /pictures.jsondefindex@pictures=Picture.allif@picturesrenderjson:@pictures,each_serializer:PictureSerializer,root:"pictures"else@error=Error.new(text:"404 Not found",status:404,url:request.url,method:request.method)renderjson:@error.serializerendend

We continue with a show and a create action:

# GET /pictures/1.jsondefshowif@picturerenderjson:@picture,serializer:PictureSerializer,root:"picture"else@error=Error.new(text:"404 Not found",status:404,url:request.url,method:request.method)renderjson:@error.serializerendend# POST /pictures.jsondefcreate@picture=Picture.new(picture_params)if@picture.saverenderjson:@picture,serializer:PictureSerializer,meta:{status:201,message:"201 Created",location:@picture},root:"picture"else@error=Error.new(text:"500 Server Error",status:500,url:request.url,method:request.method)render:json=>@error.serializerendend

As you see, I have used an error serializer and a picture serializer. The idea is the same as described in the previous repository. I will not sketch all the serializers and error classes here. I encourage you to try yourself and then have a look at the full repository on GitHub.

Note

The full app repository for all the code in this chapter can be found on GitHub. You are encouraged to check the code there and see all the functionality in more detail.

If you want to try to upload a picture through an API call you can use the following curl command:

$curl-F"picture[title]=unnamed"\-F"picture[image]=@./unnamed.jpg;type=image/jpeg"\http://0.0.0.0:3000/api/v1/pictures

Then you can check if the file has actually been uploaded to S3.

Creating Workers and a Jobs Queue

We are going to use Sidekiq to create and schedule our workers. Sidekiq worker classes are placed in app/workers. For our app, we are going to structure our workers in two distinct classes. We’ll create a ServiceWorker, where we keep the general methods that we are going to use, and an ImageFilter worker to perform the actual filtering operations on the images.

We will start by sketching our ServiceWorker:

require'rubygems'require'celluloid'classServiceWorkerincludeSidekiq::WorkerclassRequestError<StandardError;endclassBadRequestError<RequestError;endclassUnknownRequestError<RequestError;endprotected# This method will be responsible for downloading# images to process from S3defdownload(path)end# This method will be responsible for uploading# processed images to S3defupload(file,content_type,relative_path)endprivatedefsetup_options_as_instance_variables(options)options.eachdo|k,v|instance_variable_set("@#{k}",v)unlessv.nil?endendend

instance_variable_set is a method provided by the Ruby language. It is used to set the instance variable names by symbol to object. A symbol in Ruby is similar to a string, except strings are mutable, symbols are not. The variable did not have to exist prior to this call. This means that you will be able to call the variable as:

puts @variable # 'bar'

I have also defined a FileOperations module in /lib containing all the methods responsible for uploading and downloading files on S3. I am not going to sketch all the functionality here, but you can look at it in the repository for this chapter.

Now we are going to define the ImageFilter worker. This will be a simple worker class responsible for applying a sepia filter to an image:

classImageFilter<ServiceWorkerincludeImageOperationssidekiq_optionsqueue::lowsidekiq_optionsretry:5sidekiq_retry_in{3.minutes}sidekiq_retries_exhausteddo|msg|logger.error"[worker][filter] Failed#{msg['class']}with#{msg['args']}:#{msg['error_message']}"enddefperform(options)setup_options_as_instance_variables(options)logger.info"[id=#{@id}] FilterImages work started."process_filterperform_callbacks("filters/#{@id}")endprivate# Method responsible for applying a filter to an image.defprocess_filterendend

Mocks and Stubs

Something that might not be completely clear when working with workers and asynchronous operations in general is how you go about testing them. In the next chapter you will find out all about testing, mocking, and stubbing.

Creating a Resource Queue

Now that we have defined the workers, we are going to create a temporary resource queue that we can call to see the status of a certain operation.

We will define a Filter model and controller to do this, and we will use the Ohm gem to persist the queue in Redis.

Let’s start by defining the Filter model:

require'ohm'require'ohm/contrib'classFilter<Ohm::ModelincludeOhm::DataTypesincludeOhm::VersionedincludeOhm::Timestamps# Here the class attributes are defined:attribute:filter_idattribute:messageattribute:locationattribute:statusattribute:code# We use the filter_id as index on the class:index:filter_id# We define a simple serializer method:defserialize{filter:{id:filter_id,location:location},response:{message:message,code:code.to_i},status:status.to_i}endend

Then we’ll continue with the filter controller. The idea is to sketch actions that will allow a client to know the status of a filter operation and eventually cancel it. So, we will start with an index action:

defindex@filters=Filter.all.to_aif@filtersrenderjson:@filters,status:200elserenderjson:filter_not_found,status:404endend

This is a simple action fetching all the filter operations in the queue, both finished and in processing.

We continue with a show action:

defshow@filter=Filter.find(filter_id:params[:id]).firstif@filterrenderjson:@filter.serialize,status:@filter.serialize[:status]elserenderjson:filter_not_found,status:404endend

The filter show action follows the same logic that we used with the Picture model and controller. The concern filter_operations.rb contains all the logic that has been extrapolated out of the controller (for more on concerns, see “Defining the models” on page 116).

The filter_not_found method is defined in the concern following this logic:

deffilter_not_found{response:{message:'Not Found',code:404},status:404}end

The next action that is defined in the filter controller is create:

defcreateifImageFilter.perform_async(build_filter_params(params))@filter=create_filter(params)renderjson:@filter,status:@filter[:status]elserenderjson:filter_error,status:500endend

The create_filter and filter_error methods are also designed in the concern:

defcreate_filter(params)filter=Filter.create(filter_id:params[:id],message:'Accepted',location:"filters/#{params[:id]}",code:202,status:202)iffilterfilter.serializeelsefilter_errorendenddeffilter_error{response:{message:'Internal Server Error',code:500},status:500}end

The complete application can be found in the repository for this chapter. I have decided not to sketch all the methods because I believe you might want to play with the code a little bit yourself before looking at the repository for the complete solution. I actually encourage you to do so. Hacking around a sample app is a great way to start applying new concepts and to try out what you have just learned.

Callbacks

A callback in the HTTP world is a GET or POST request that passes some argument to a certain web server, which returns a result or response.

Callbacks are used in asynchronous REST operations, like some of the tasks performed by the sample app that we have built in this chapter.

There is a difference between using callbacks and implementing a status queue. When you implement a status queue, it is the client’s responsibility to check the queue periodically; the server will just expose the status of the operation or resource requested.

When callbacks are implemented instead, the client can request a certain operations that the server will execute at a later time. Then the client will expect the server to perform a request to a certain endpoint. That is a callback, and its effect will be to notify the client that the operation has finished with a certain result.

WebSockets

WebSockets is sometimes used instead of asynchronous RESTful requests; it is not a REST method. The WebSocket protocol is specifically used to provide a full-duplex communication channel over a single TCP connection. It does not use the HTTP protocol apart from the initial handshake, which is interpreted by the parties involved as an UPGRADE request.

An UPGRADE HTTP request uses the Upgrade header field: it is specifically used in the WebSocket domain to let the server know that the connection has switched to a different protocol.

The connection upgrade request must be made by the client. On the other side, if the server wants to enforce the upgrade to a newer or different protocol it may send a 426 (Upgrade Required) response.

The WebSocket protocol facilitates live content and the creation of real-time interaction between a browser client and a server. With the WebSocket protocol, the server can in fact send content to the browser without the client requesting it, in a standardized way. Messages between client and server can therefore be passed back and forth while the connection is kept open. This way the communication between server and client is really bidirectional (two-way).