Chapter 5. Designing APIs in RoR

In this chapter we will design a hypermedia API in RoR. We will first explore the principles of adaptable hypermedia interfaces and then see how to make resources explorable.

We will discuss the application flow that services should have, and we will talk about APIs in terms of actual interfaces instead of just sets of commands that you can learn by visiting a man page (or developer portal, in the case of web services).

Finally, we will make our Wikipedia categories API fully explorable.

Hypermedia and Adaptable APIs

In the API community, hypermedia is a hot topic capable of generating heated discussions. How should a hypermedia API be designed? What functionality should be implemented? What media types should be supported? Should new media types be defined? These are some of the questions that arise when talking about hypermedia APIs, and almost everyone seems to have different answers to them.

The whole concept of hypermedia is about making clients interact better with services, and making resources easily accessible and explorable.

Designing resources can be especially confusing, because the first question you need to answer is what exactly is a resource anyway?

Is a resource some table in a database? Is it something else? In reality a resource can be a bit of both. It can be a record in a database, but it can also contain information from other records, or from other databases or applications. A resource is essentially a gateway to some dataset.

Once we overcome the restriction of thinking about resources as records in a database, we can start thinking about resources as sets, or flows, or even better, streams of information.

If we think for a moment about the evolution of the Internet and the Web, we are witnessing the transformation of a complex system from a platform of interconnected computers to a platform of interconnected documents to a platform of interconnected data streams. This is what is intended by the “Web of Data”: a platform built on the decisions that we have made in the past, mostly with the same or similar design objectives, that will provide new services with familiar paradigms.

When designing a hypermedia API we have to consider that users need to be able to act on these streams of information in a way that is both intuitive and permits them to freely use this flow of data to build other tools, applications, or services.

Making this possible—enabling developers to consume your stream of information and create new streams—needs to be your ultimate design goal when developing hypermedia services. So, hypermedia goes beyond making resources link to other resources; it is about making information available for consumption and explorable in an adaptable way that will still be valid a year from now, that will scale organically with demand, and that will evolve as the Web does, as new protocols and media types are introduced.

We have said that REST is essentially an abstraction of the Web, and building hypermedia applications or APIs isn’t completely different from building web applications. The design processes and the underlying reasoning are essentially the same.

So what exactly is a RESTful API? And how do we make an API adaptable? To answer these questions we have to concentrate on two main aspects of REST and hypermedia. The first aspect is the uniformity of REST interfaces, and the second concerns hyperlinks between resources.

The uniformity of REST interfaces allows the usage of different types of identifiers in the same context, providing uniform semantics even when the access mechanism used may be different. As a matter of fact, we don’t even have to be concerned with the access mechanism; we just need to ensure that our API replies consistently. The same principles permit us to introduce new types of resource identifiers without having to change the way existing identifiers work, while also allowing reuse of identifiers in a different context.

The uniformity principle enables us to develop and design different parts of a service independently from each other, while also providing a consistent way for these parts to communicate and exchange information.

The linked data model provides a way to interconnect data from various sources. Links provide the possibility to perform reasoning about resources, find contextual information, discover relationships, and associate data with real-world concepts.

Sometimes the semantic value of links is overlooked. One could argue that metadata and simple keywords could provide the same information, but while this may be true for some simple applications, links can certainly be used to provide more semantically accurate results.

Just imagine you’re looking for a certain image using any image searching service (Google Images, Flickr, Instagram). If you just type a single keyword, the search results returned would reflect that keyword based on certain criteria, depending on the service: color, quality, popularity, number of views.

Now suppose you have an API application that returns you an image of a specific mountain with some JSON describing the image and its context:

"image":{"title":"Matterhorn covered in snow","timestamp":"Thu Oct 2 19:42:23 CEST 2014","location":{"point":{"latitude":45.97638888888889,"longitude":7.65833333333333},"country":"Switzerland","city":"Zermatt","region":""Valais",},"links":{"self":{"href":"service.com/api/v1/users/user1794/albums/mountains/images/matterhorn_covered_in_snow.png","method":"GET","rel":"self"},"next":{"href":"service.com/api/v1/users/user1794/albums/mountains/images/matterhorn_from_the_slopes.png","method":"GET","rel":"next"},"wiki":{"href":"http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matterhorn%20","method":"GET","rel":"wiki"}},"tags": ["mountain","snow","switzerland","skiing"],"data":"data:image/png;base64,<Databitstream>"}

Metadata containing only the tags used to describe the photo simply would not have been able to provide the same information. We would probably have known that it was a picture of the Matterhorn, but the semantic information provided by this simple API permits us to discover much more about the picture and its context.

The API also can be extended to include more information, like related searches or pictures by country or by city. And if designed properly the service can be developed organically by adding other interesting data and links that can be used by other services consuming our API.

You could for example decide to add an album field under links to point to the parent album. This can be easily done by simply adding a field in your JSON object:

"parent":{"href":"service.com/api/v1/users/user1794/albums/mountains/","method":"GET","rel":"album"}

What’s more, developers wouldn’t have to modify their applications. They could just continue using your API as before, and if they wanted they could integrate this new feature into their code.

REST Patterns

REST principles are extremely simple. So, a common question that comes up when talking about how to design APIs concerns the service and architecture complexity and where this can be hidden.

In reality the neat part of REST is that by combining relatively simple architectural elements is it possible to build entire systems with complex functions.

To begin with, in REST there are no objects or methods. We have resources instead. Of course, behind REST your system will contain objects, database records, and methods to modify and access these objects, but this doesn’t concern REST.

REST is about resources and how their representations can be consumed. Although the resource is probably the most central element of REST, REST APIs do not define strict resource names or hierarchies of resources; neither do they strictly decouple client and server functionality.

REST APIs instead define a way to access resources and act on their representations. They require minimal knowledge about the actual implementation, impose minimum client-side dependencies, and make minimal assumptions about how they are going to be used, leaving a great deal of freedom in the user’s hands. REST APIs are simple and permit developers to prototype simple or common use cases very quickly. They are self-describing and require only minimal documentation.

Creating Hypermedia Interfaces

Hypermedia is a fundamental component in the uniformity principle of REST interfaces. It allows clients to explore REST APIs by requesting a stream of data and following the hyperlinks included in this stream to retrieve other resources.

While REST is totally stateless, using hypermedia resource representations allows the client to manage state transitions. In fact, if an API defines a next field in the JSON response, the client could navigate to the next resource. This results in a navigation flow that could be considered similar to a user interface and which is the product of the interaction between the client and the server.

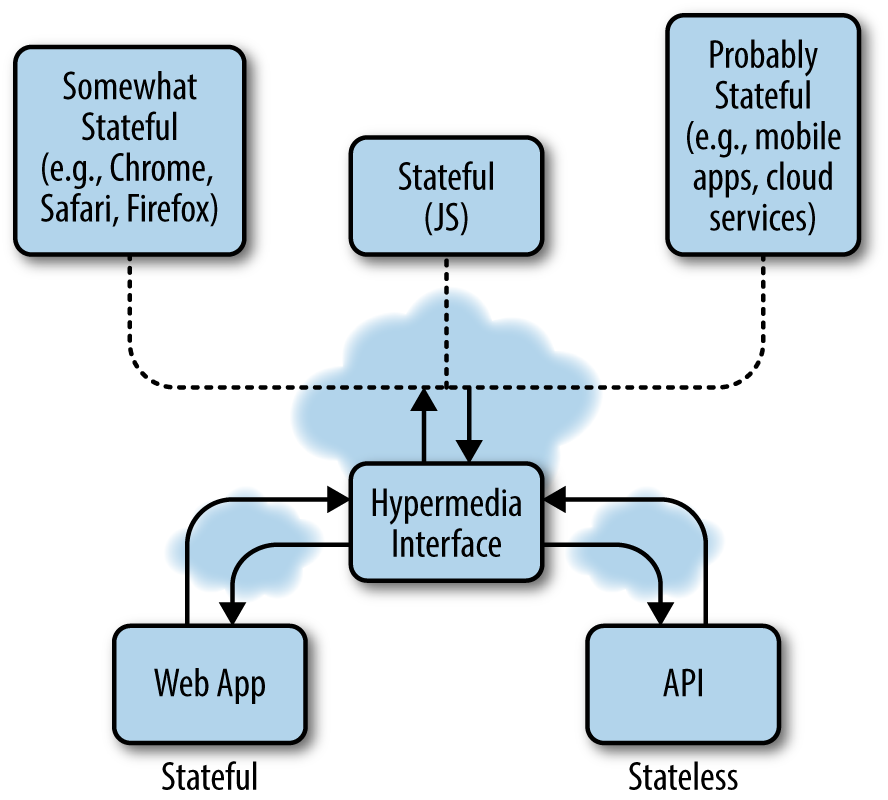

Hypermedia interfaces allow clients to maintain control over the application status and move state information away from the server while also allowing for more complex interactions (Figure 5-1). A hypermedia interface could be anything from a web app allowing a client to communicate with different devices to an application framework incorporating various idioms, data types, object models, and state information.

Figure 5-1. REST APIs and web apps can communicate via a hypermedia interface that can stream data in different formats to different devices

Resource-Oriented Thinking

Resource-oriented thinking represents a shift from entity–relationship and object-oriented design. The problem with resource-oriented thinking is that resources can be records in a database or models in our code, or a combination of the two.

Also, an important aspect of resource-oriented thinking is that the stream of data resulting from requesting a particular resource at a certain URI can be the product of the interactions of different services.

Let’s think again of our image object in JSON. We might have obtained it by requesting a specific photo resource from a certain album on our favorite image sharing service. The information attached to the photo could have been obtained by that service making requests to a number of other services and applications that we might not even know about.

How do we start thinking about our applications in terms of resources, then? We have said that resources are in reality streams of data. So, we need to start designing our applications in terms of data and actions on data streams rather than on objects or entities.

Designing Explorable Resources

Designing explorable resources implies thinking about what data you want to serve and what actions on that data you want to provide.

If we go back again to the photo object example, you can see we have included a next and a parent link. We also have provided an external link, to the Wikipedia page for the object described in the picture.

We have specified a link field only for the photo object, and not, for example, for its keywords or its location information. Deciding what other resources or streams we want to link to a given resource is entirely a design choice. We could have decided to list pictures taken nearby, or external information regarding the country or the city fields. It all depends on what services we want our API to provide.

HATEOAS

HATEOAS (Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State) is a constraint of REST that distinguishes it from almost any other architectures. The core principle is that the client can interact with an application through hypermedia calls. The REST client does not need any prior knowledge of the particular implementation of the server. The server dynamically provides links for the client to explore the set of available resources.

Traditionally, web APIs have been designed as a simple way to get some data out of some service. By using hypermedia for their representation, APIs are instead transformed into application interfaces, used by software agents to discover and create information. If APIs are designed with this paradigm in mind, once the client hits the application entry point, it should be able to find its way around the application, in a similar manner to a human reader browsing the content of a website.

The application flow defines the way resource representations are accessed and acted upon. Therefore, thinking in terms of explorable resources is easier if we concentrate on the application flow we want our users to follow.

Each time the API is called, it will return an array of links that the user or software agent can follow to request more information about a call or to further interact with the application. The logic necessary to use the API doesn’t need to be hardcoded in the client; it only needs to adhere to REST principles.

More importantly, the application can be designed to return only contextual links, so the client will only receive the information relating to a certain request.

The WikiCat Hypermedia API

We are now ready to extend our Wikipedia categories API into a fully hypermedia API.

Our objective is that a client visiting the API entry point will not need any information about the API itself to navigate it.

Our starting point is defining the application flow: i.e., once a client hits the entry point of our application, what information would we like to present?

The API we have built up to this point returns categories and their subcategories. It makes sense to show our top categories once we hit the API entry point. From there the client might navigate the category graph if it wishes, or just send some requests once it has learned how to use the API.

Wikipedia recognizes a list of major classification topics, used to organize the presentation of links to articles. This list of topics is included under the top category: Main_topic_classifications.

Another list of top-level categories is included under Fundamental_categories. This is based on a smaller number of initial thematic classifications.

You are free to experiment with the two top categories, and I have prepared the seeds.rb file to include both.

I believe, though, that it is more interesting to use the Main_topic_classifications category, simply because it contains a richer list of subcategories to be explored. Two of these, Sports and Science, have been included in the seeds.rb file so that you can explore the graph two levels deep.

We start by modifying the graph controller under controllers/api/v1/graph_controller. We want to make sure that the default category is Main_topic_classifications. Therefore, we change the following line in the index action:

category=params[:category]?params[:category]:"Main_topic_classifications"

This says if a category parameter is provided, use it, and otherwise, use Main_topic_classifications.

Let’s start the database and the server and verify it is working:

$mysqld&$railsserver

If everything is working correctly, we will see the JSON string describing the graph for the top category:

{"main_topic_classifications":[{"sub_category":"arts",...}]}

Once we have made sure that our gateway is working correctly, we can continue defining the other actions in the controller.

First, we’ll modify the show action. This time we will also make sure to render errors properly:

defshowcat=params[:category]||'sports':"Main_topic_classifications"@category=Category.where(:cat_title=>cat.capitalize).firstif@category@links=Link.where(:cl_to=>@category.cat_title,:cl_type=>"subcat")render:json=>@links,each_serializer:LinkSerializer,root:@category.cat_title.downcaseelserender:json=>{:error=>{:text=>"404 Not found",:status=>404}}endend

Now we’ll modify the link serializer to display some more information. What we would like to achieve is displaying a category link pointing to the subcategory information with self, a next link pointing to the next linked category, and a graph link pointing to the same subcategory graph:

classLinkSerializer<ActiveModel::Serializerattributes:sub_category,:linksdefsub_categoryURI::encode(object.cl_sortkey.force_encoding("ISO-8859-1").encode("utf-8",replace:nil).downcase.tr(" ","_"))enddeflinks{:self=>_self,:next=>_next,:graph=>graph}enddefgraphhref=URI::encode("/api/v1/graph/#{self.sub_category[/([^0A]*(.)$)/]}"){:href=>href,:method=>"GET",:rel=>"graph"}enddef_selfhref=URI::encode("/api/v1/category/#{self.sub_category[/([^0A]*(.)$)/]}"){:href=>href,:method=>"GET",:rel=>"self"}enddef_nexthref=URI::encode("/api/v1/category/#{object.cl_to}"){:href=>href,:method=>"GET",:rel=>"_next"}endend

Note

Note the difference between self and object in the serializer. Self refers to the serializer itself, while object refers to the link model.

You will notice that the link graph is a bit slow to load. To speed it up we would need to add an index on the cl_sortkey attribute in our links table. In order to create a new index we will generate a migration:

$railsgeneratemigrationAddIndexToLinkscl_sortkey:indexinvokeactive_recordcreatedb/migrate/20140908145510_add_index_to_links.rb

A file has just been created in the db/migrate folder. We can modify it in order to add another index field and speed up our queries to the links table:

classAddIndexToLinks<ActiveRecord::Migrationdefchangeadd_index:links,:cl_sortkeyendend

We can now test our graph API again and see if it works as expected:

http://0.0.0.0:3000/api/v1/graph/science.json{"science":[{"sub_category":"scientific_disciplines","links":{"self":{"href":"/api/v1/category/scientific_disciplines","method":"GET","rel":"_self"},"next":{"href":"/api/v1/category/Science","method":"GET","rel":"_next"},"graph":{"href":"/api/v1/graph/scientific_disciplines","method":"GET","rel":"graph"}}},{...},]}

Note

If you want, you can also create the up action in the graph controller to display the upstream graph from a category. We will use this in later chapters.

You can compare your solution with the one proposed in the next chapter, or check out the GitHub repository for the WikiCat API.

Now that we have obtained the explorable graph, we can make our categories explorable. Let’s go ahead and modify the show method in the category controller. Our objective is displaying the Main_topic_classifications when no category param is provided:

defshowcategory=params[:category]?params[:category]:"Main_topic_classifications"@category=Category.where(:cat_title=>category.capitalize).firstif@categoryrender:json=>@category,serializer:CategorySerializer,root:"category"elserender:json=>{:error=>{:text=>"404 Not found",:status=>404}}endend

Once we have modified the controller we can go ahead and modify the serializer. Our objective is to make the category resource explorable by linking to its graph:

classCategorySerializer<ActiveModel::Serializerattributes:title,:sub_categories,:_linksdeftitleURI::encode(object.cat_title.force_encoding("ISO-8859-1").encode("utf-8",replace:nil).downcase.tr(" ","_"))enddefsub_categoriesobject.cat_subcatsenddef_links{:self=>_self,:graph=>_graph}enddef_graphhref=URI::encode("/api/v1/graph/#{self.title}"){:href=>href,:method=>"GET",:rel=>"graph"}enddef_selfhref=URI::encode("/api/v1/category/#{self.title}"){:href=>href,:method=>"GET",:rel=>"self"}endend

If everything is working as expected we can test our category resource and receive the JSON object string:

http://0.0.0.0:3000/api/v1/category/science{"category":{"title":"science","sub_categories":34,"_links":{"self":{"href":"/api/v1/category/science","method":"GET","rel":"self"},"graph":{"href":"/api/v1/graph/science","method":"GET","rel":"graph"}}}}

Perfect—our WikiCat API is now fully explorable! You can continue testing all the methods if you want, or you can read the other test cases that have been created for this app in the GitHub repository.

Wrapping Up

In this chapter we have sketched our first hypermedia API with Ruby on Rails. In the next chapter we will learn about asynchronous REST and what mechanisms we can use when the application server needs to perform some actions at a later time.