Chapter 10. Data Storage and Querying: Storing and Fetching Relevant Messages

In this chapter you will learn more about data storage and retrieval (i.e., querying in Opa). We will start with some general concepts and then illustrate them by applying them to our Birdy app.

Collections in Opa: Lists, Sets, and Maps

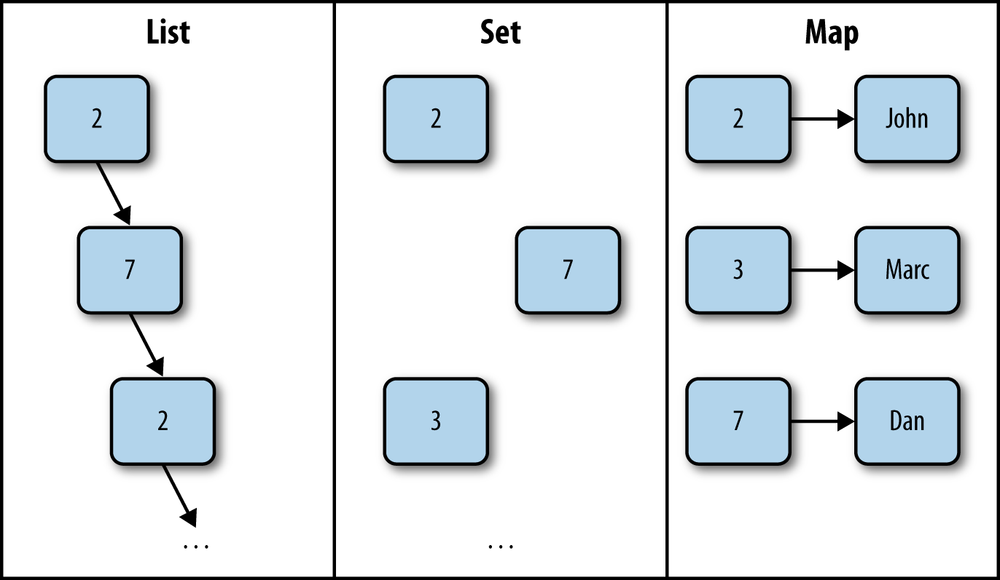

Collections are used to represent multiple instances of the same type of data. In Opa, there are three primary types of collections:

- Lists

- Sets

- Maps

Lists represent a sequence of items. The order of items is the order of insertion. There may be multiple occurrences of the same value in a list. We talked about lists in Recursive Types.

Sets represent a group of items, ordered by an

order, typically an alphanumerical sort. Sets cannot contain duplicates.

They correspond to the mathematical notion of a set.

Maps are mappings from keys to values. They are often known by alternative names, such as associative array or dictionary. All the keys in a map are distinct.

Figure 10-1 depicts these different types of collections.

In the following sections we will discuss how to:

- Declare data for storage

- Write new or update previously stored data

- Query and retrieve data from storage

In each section we will also discuss features specific to records, lists, sets, and maps.

Declaring Data

We briefly talked about using databases in Opa in Chapter 4, but now it it time to present a more complete picture. Imagine that we want to write a movie-related application. Let’s begin with a few relevant definitions.

Note

An abstract type is the directive that can be put on type definitions to hide the implementation of a type to the users of a library. Abstracting forces users to go through the interface of the library to build and manipulate values of that type.

Let’s take the following type declaration:

abstracttypeMovie.id=inttypeMovie.cert={G}/{PG}/{PG-13}/{R}/{NC-17}/{X}typeMovie.crew={Person.name director,list(Person.name)cast}

Movie.id is an abstract identifier of a movie; by keeping it abstract, we ensure

that only the package in which this declaration occurs can manipulate such identifiers

(e.g., create new values of that type). Movie.cert is an enumeration type for the U.S. motion

picture rating system. Finally, Movie.crew holds (simplified) information about the

people involved in the movie, with a single director and a list of the cast (in credits

order).

We can now define a data type for a movie:

typeMovie.t={Movie.id id,string title,Movie.crew crew,int no_fans,int release_year,Movie.cert cert}

This movie consists of an ID, title, and crew (id, title, and crew), the number of fans (no_fans) of the

movie, the year the movie was released (release_year), and the movie’s rating (cert).

Now we are ready to declare the database:

databasedata{Movie.t/movies[{id}];map(Movie.id,string)/synopsis;int access_counter=0;}

The /data/synopsis path should look familiar [we briefly discussed maps

in Maps (Dictionaries)]; it declares a mapping from a Movie.id to its string

synopsis.

As for /data/movies, it declares a set of values of

type Movie.t. Here the set is indicated by the square brackets

after the path. Within square brackets one needs to specify record fields

(comma-separated) that will be used as the primary key for the set. This means

the combination of those fields should be unique across all set values. In our

simple example, we use a dedicated id field for that, which is a common strategy.

Finally, we have a single int field, access_counter, which is initialized to

0.

Inserting/Updating Data

We already discussed some ways of adding/updating data in Maps (Dictionaries).

For example, adding a synopsis for the movie with ID 1 can be done

with:[3]

/data/synopsis[1]<-"The aging patriarch of an organized crime dynastytransfers\control of his clandestine empire to his reluctant son."

Can you guess which movie this synopsis belongs to?

Manipulating sets is done in a similar way:

/data/movies[{id:1}]<-{id:1,title:"The Godfather",crew:{director: "Francis Ford Coppola",cast: ["Marlon Brando", "Al Pacino", "James Caan"]},release_year:1972,no_fans:0,cert:{R}}

By providing only a subset of fields, we can do partial updates. The

following examples also illustrate special features for updating

int and list values:

// update a single field only/data/movies[{id:1}]<-{no_fans:100}// increase no_fans by 1/data/movies[{id:1}]<-{no_fans++}// increase no_fans by 10/data/movies[{id:1}]<-{no_fans+=10}// add one element at the end of a list/data/movies[{id:1}]/crew/cast<+"Richard S. Castellano"// add several elements at the end of a list/data/movies[{id:1}]/crew/cast<++["Robert Duvall","Sterling Hayden"]// remove the first element of a list/data/movies[{id:1}]/crew/castpop// remove the last element of a list/data/movies[{id:1}]/crew/castshift

Can you figure out what data about The Godfather is stored after all those operations? At the end of the complete program of this section, add the following:

println("{/data/movies[{id:1}]}")

Then execute it and you will see something along the lines of this:

{crew:{cast: [Al Pacino, Marlon Brando, Richard S. Castellano, SterlingHayden],director: Francis Ford Coppola},id:1,no_fans:111,release_year:1972,title:TheGodfather}

Reading (and Querying) Data

Now that you know how to declare and insert/update data, it’s time to learn how to query the database to obtain required information. For simple structures, such as single values or records, all we can do is read the data; we discussed that many times already:

int n=/data/access_counter

However, things get more interesting with collections; that is, sets and maps. You already saw how to obtain single elements of collections, by indexing them:

movie_id=1string movie_synopsis=/data/synopsis[movie_id]Movie.t movie_data=/data/movies[{id:movie_id}]

By indexing with a single value, which corresponds to the primary key for the set, we are certain to get no more than one value as a result. If the value does not exist, we will get a default result; if this is not what we need, we can always use the optional read operator:

option(string)opt_synopsis=?/data/synopsis[movie_id]option(Movie.t)opt_data=?/data/movies[{id:movie_id}]

In this case, the result of the operation is none if the data does not exist,

and some(...) if it does.

However, it is possible to use less precise indexing, in which case we may get more than one value as a result. The general scheme of such operations is the following:

/path/to/data[query;options]

Comparison operators represent an important building block of queries:

-

== exprmeans the value equals that ofexpr. -

!= exprmeans value does not equal that ofexpr. -

< expr,<= expr,> expr, and>= exprmeans the value is, respectively, less than, less than or equal to, greater than, or greater than or equal to that ofexpr. -

in exprmeans the value belongs to that ofexpr, whereexpris a list.

Now a query can be any of the following:

-

op - This is just a comparison operator; this query works for maps and means that we will be comparing keys of map entries.

-

field op -

This is the field’s name followed by a comparison operator, meaning we filter entries based on comparisons of the record

field. -

field/subfield op - This means we are using some field located deeper in the record structure for comparison.

-

f1 op1, f2 op2, ... -

This means we are using the comparison operator

op1for fieldf1,op2forf2, and so on. -

field[_] op - The given field should contain a list, and this query means any element of the list passes the comparison.

There are also few binary operators to combine queries into more complex ones:

-

q1 or q2 -

All values satisfying either query

q1or queryq2 -

q1 and q2 -

All values satisfying both queries

q1andq2 -

not q -

Values not satisfying the query

q

Finally, the query options consist of a list of zero or more of the following entries, separated by semicolons:

-

skip n -

Skips the first

nresults (nshould be an expression of typeint). -

limit n -

Limits the result to the maximum of

nresults (nshould be an expression of type int). -

order fld1, fld2, ... -

Specifies that the results should be ordered first by

fld1, thenfld2, and so on. Everyfldvalue should be an identifier preceded by a plus sign (+) or a minus sign (-), with+fieldindicating ascending sorting byfieldand-fieldindicating descending sorting byfield. It is also possible to use a version offield=exprto choose the order dynamically, whereexprshould be an expression evaluating to either{up}or{down}, indicating, respectively, ascending and descending order.

As mentioned earlier, such queries may result in more than one matching result; hence, the natural question is: what is the type of the result of such queries?

For maps, the type is the same as that of the queried map and the result of a query is a sub-map, that is, a map containing only part of the bindings of the original one.

For sets, the resultant value is of a special type, dbset(t, _), where t is the

type of queried values and the second argument to the dbset type depends on what database

backend is used; it can be safely ignored and replaced with an underscore in most

cases.

The first step in dealing with such results will usually be to convert them

to iterators with the DbSet.iterator function, and then to use standard functions

from the Iter module.

As is often the case, an example is worth a thousand words, so let’s look at a few examples of queries in action.

dbset(Movie.t, _) movies2000 = /data/movies[release_year == 2000]Iter.t(Movie.t) it = DbSet.iterator(movies2000)

xhtml movies = <>{Iter.map(Movie.render, it)}</>

dbset(Movie.t, _) popular_movies = /data/movies[no_fans >= 1000]

dbset(Movie.t, _) children_movies = /data/movies[cert in [{G}, {PG}]]

dbset(Movie.t, _) new_popular = /data/movies[release_year >= 2000 and no_fans >= 1000]

dbset(Movie.t, _) non_x_rated = /data/movies[not cert == {X}]

dbset(Movie.t, _) some_popular = /data/movies[no_fans >= 10000;

skip 100; limit 50; order -release_year, -no_fans] dbset(Movie.t, _) by_coppola = /data/movies[ crew/director == "Francis Ford Coppola"]

dbset(Movie.t, _) with_pacino = /data/movies[ crew/cast[_] == "Al Pacino"]

map(Movie.id, string) synops = /data/synopsis[>=1000 and <=1500]

Fetch all the movies that were released in the year 2000.

Convert the results to an iterator.

Use the

Iter.mapfunction to render all fetched movies with theMovie.renderfunction and obtain thexhtmlvalue.

Fetch all movies with at least 1,000 fans.

Fetch all movies with a G (General Audiences) or PG (Parental Guidance Suggested) age certificate.

Fetch all movies released after 2000, that have at least 1,000 fans.

Fetch all non-X-rated movies.

Fetch the positions 101-150 (skip the first 100 and limit the results to 50) of movies with at least 10,000 fans, sorted by decreasing release year and, within the same release year, by the number of fans.

Filter based on the subfield

directorof thecrewrecord, effectively fetching all movies directed by Francis Ford Coppola.

This is somewhat similar to the preceding query, but this time we filter based on a

castlist of thecrewrecord, fetching records where any elements of this list satisfy the given condition; this effectively fetches all movies starring Al Pacino.

Fetch a submap of the

/data/synopsismap, for movies with an ID above 1,000 and below 1,500.

From these instructions and examples it is worth noting that sets and maps are very powerful for data storage. They essentially allow you to store collections of data, and then query them in fairly arbitrary ways. We will now discuss a powerful extension to the query mechanism: projections.

Projections

Imagine that we did not need all the information about some particular movie, but only the title of the movie with a particular ID. We could do that with the following query:

string title=/data/movies[{id:1}]/title

The query /data/movies[{id: 1}] returns a single movie (with ID 1), and the

remaining path, /title, means to project the resultant record to its single

title field, which is of type string. Hence, that is the final type of such

a query. It also works for queries with multiple results; for instance, to

get the titles of all movies released in the year 2000, we could use the

following query:

dbset(string,_)titles=/data/movies[release_year==2000]/title

It is also possible to project into more than one field, although then, the syntax is slightly different. For example, imagine that we just wanted to fetch the title and the name of the director of a movie with a given ID; this query would do the job:

{string title,string director}m=/data/movies[{id:1}].{title,crew.director}

Of course, it is also possible to do this kind of projection for multiple-result queries.

The main reason for using projections is performance. Most of the time it would be fine to fetch all the data from the database and only use the portions that we need. However, this may be an expensive operation, and we may be fetching a lot of information that we won’t use anyway. Projections allow us to fine-tune the information transfered from the database to our program.

Data Manipulations in Birdy

You will now apply the knowledge you’ve gained from this chapter to Birdy. You will learn how to:

- Declare appropriate data storage

- Store new messages

- Retrieve messages based on some filtering criterion

Database Declaration

You’ve already manipulated Birdy messages and introduced a type representing

them, Msg.t. Now it is time to save them in the database for persistent storage.

First, we will recapitulate the definition of the Msg.t type introduced in

Modeling Messages:

abstracttypeMsg.t={string content,User.t author,Date.date created_at}

Since this is a self-contained type with all the information about the message, including its author, content, and creation date, one possibility is to store all the Birdy messages as a set of values of that type. This can be accomplished with the following database declaration:

databasemsgs{Msg.t/all[{author,created_at}]}

Here, we declare a primary key consisting of two fields: the author and the creation date of the message. Since dates work with millisecond precision, we assume that no author will publish two different messages in the same millisecond, and hence, this is a unique primary key.

Tip

If there is no natural primary key for the stored data, it is a frequent practice

to introduce a dummy id field in the record, whose sole purpose is to identify

the accompanying data and to serve as its primary key.

The previous database declaration relates to messages, so we could just add it to the /src/model/msg.opa file. But as our strategy is to use a dedicated source file collecting all database declarations, we will slightly modify our declaration and add it to src/model/data.opa:

databasebirdy{User.info/users[{username}]Msg.t/msgs[{author,created_at}]}

Storing New Messages

With the database declaration in place, we can now replace the dummy store function

with a real one:

functionvoid store(Msg.t msg){/birdy/msgs[{author:msg.author,created_at:msg.created_at}]<-msg;}

This function just adds a new entry to the /birdy/msgs set, indexed by the

author and creation date of the given message.

Tip

Running this program and monitoring message creation activity with a network profiler, which is an integral part of most modern browsers, reveals that creating a new message results in nine network requests.

This is because the store function uses the database, and hence resides on the server

and needs to be accessed from the client when creating a new message. We can optimize

this behavior by declaring this function as exposed:

exposedfunctionvoid store(Msg.t msg){/birdy/msgs[{author:msg.author,created_at:msg.created_at}]<-msg;}

After this change, the number of network requests drops to two: the expected single round-trip communication with the server.

Fetching Relevant Messages

While developing code to render messages in Rendering Messages we

introduced internal links of the shape /user/[USERNAME] and /topic/[TOPICNAME].

Those URLs will serve pages showing messages for a given user and topic,

respectively. In order to develop such pages, we first need to fetch

relevant messages that will be displayed on those pages; we will address this topic

in this section and you will learn how to create those pages

in User and Topic Pages.

What messages should be displayed on those pages? It is quite clear for the topics: every topic page should display all messages containing references to that topic. For the user pages, it is more complicated, as we want them to display:

- All messages posted by the page owner (i.e., the given user)

- Messages of all the users followed by the given user

- Messages concerning all the topics followed by the given user

- Messages mentioning the given user

First we’ll turn our attention to a function that returns all the messages for a given topic. How do we write it? Recall that our type for a message looks as follows:

abstracttypeMsg.t={string content,User.t author,Date.date created_at}

The content contains the content of the message as an unstructured string

and we were using the analyze function to decompose it into segments,

with user and topic references. However, with this data organization we have

no chance of performing our task effectively, as we would need to fetch

all the messages, analyze them one by one, and filter those that mention the

topic we are interested in, an approach that would quickly become unacceptable

in terms of performance.

How can we improve it? By employing the classic technique of enriching the

data with redundant information that will enable us to perform the data

querying we need effectively. In our case, we need to know which users and

which topics every message refers to, so the solution is to add two new fields

containing this information to our Msg.t type:

abstracttypeMsg.t={string content,User.t author,Date.date created_at,list(Topic.t)topic_refs,list(User.name)user_refs}

We now need to initialize those two fields in the create function that

creates a new message. We would like to reuse the analyze function to

get the list of topics and users referenced in the message, but the problem is

that this function takes a Msg.t argument and we cannot supply it yet,

as at this point we are in the process of creating a new message value. The

solution is to change the type of this function to operate on the string

containing the raw content of the message, so this:

functionlist(Msg.segment)analyze(Msg.t msg){...Parser.parse(msg_parser,msg.content)}

becomes this:

privatefunctionlist(Msg.segment)analyze_content(string msg){[...]Parser.parse(msg_parser,msg)}functionlist(Msg.segment)analyze(Msg.t msg){analyze_content(msg.content)}

As you can see, we still make available the analyze function with the

same type signature as before, which ensures that all the code outside

of this module will work just as before. However, internally we develop

a more low-level analyze_content function. We make it private to

ensure that it is not visible from outside of the Msg module. We can

now use it in the create function to initialize the topic_refs

and user_refs fields:

functionMsg.t create(User.t author,string content){msg_segs=analyze_content(content){~content,~author,created_at:Date.now(),topic_refs:get_all_topics(msg_segs),user_refs:get_all_users(msg_segs)}}

We use two private functions, get_all_topics and get_all_users, that

(given the list of segments of the message) return, respectively, the list

of topics and users referenced in this message. A possible implementation

of those functions could look as follows:

privatefunctionlist(Topic.t)get_all_topics(list(Msg.segment)msg){functionfilter_topics(seg){match(seg){case~{topic}:some(topic)default:none}}List.filter_map(filter_topics,msg)}privatefunctionlist(User.name)get_all_users(list(Msg.segment)msg){functionfilter_users(seg){match(seg){case~{user}:some(user)default:none}}List.filter_map(filter_users,msg)}

Now we are done with user pages and topic fetching.

It is easy to miss the importance of what happened here, though.

Note that we changed the internal representation of messages in the system

(by enriching it with some information) without making any changes outside of

the message module. This was possible thanks to the fact that:

-

Msg.ttype wasabstract, meaning the type could only be directly manipulated in the package in which it was declared and from the outside had to be accessed via the function provided in the package. -

We did not change the API (i.e., the signatures of the nonprivate functions) of the

Msgmodule.

Tip

This is an extremely important lesson in data encapsulation. Lessons that should be learned from this exercise are:

- Whenever possible, make types abstract so that irrelevant implementation details are hidden in the given module.

- Be careful when designing the public API of the module, which should only expose relevant features. Ideally, changing the internal representation of the type should be possible without making any changes to the public API, in which case such a change will only be local to the relevant package, just as was the case in our example.

The bigger the team, the larger the project, and the more important it is to use abstract data types. For large projects, abstract data types might be one of the most powerful features of Opa.

Having our message type enriched with data, we can now easily write functions to return messages related (in the aforementioned sense) to a given topic or user:

functionmsgs_for_topic(Topic.t topic){/birdy/msgs[topic_refs[_]==topic;order-created_at;limit50]}

To understand this better, let’s take a look at all the components of this query and their meanings, step by step:

/msgs/all[topic_refs[_] == topic;

order -created_at;

limit 50

]

The function returning messages for a given user is only slightly more complicated:

function msgs_for_user(User.t user) {

userdata = /birdy/users[{username: user.username}]  /birdy/msgs[author.username in userdata.follows_users or

/birdy/msgs[author.username in userdata.follows_users or  topic_refs[_] in userdata.follows_topics or

topic_refs[_] in userdata.follows_topics or  user_refs[_] == user.username or

user_refs[_] == user.username or  author.username == user.username;

author.username == user.username;  order -created_at;

order -created_at;  limit 50]

limit 50]  }

}

Fetch the data of the user with username

user.usernameand bind it touserdata.

Return all messages whose author belongs to the list

userdata.follows_users, that is, to the list of those followed by the given user...

...or which refers to the topic that is on the list of topics followed by the given user (

userdata.follows_topics)...

...or which refers to the given user...

...or whose author is the given user.

Order the results in descending order by creation date.

Limit the result to the first 50 entries (at most).

Warning

In our example application we will always show, at most, the 50 most recent results.

Usually, in a real application one would want to allow users to get access

to older messages as well. This is typically achieved by pagination of

results. To implement this, we would need to extend the preceding queries with a

skip X; limit Y clause that would ensure that we obtain a window of, at most,

Y results starting from position X.

User and Topic Pages

Now that we have functions to retrieve relevant messages, let’s construct

user and topic pages. First, we need to take care of the navigation, or URL

dispatching. This is the role of the controller, so we will add two more cases to

the Controller.dispatcher function in /src/controller/main.opa:

functiondispatcher(Uri.relative url){match(url){case{path:["activation",activation_code]...}:Signup.activate_user(activation_code)case{path:["user",user|_]...}:Page.user_page(user)case{path:["topic",topic|_]...}:Page.topic_page(topic)default:match(User.get_logged_user()){case{~user}:Page.user_page(User.get_name(user))default:Page.main_page()}}}

Note that we also modify default, adding a new case for the logged-in user that will

display the user’s page upon signing in when the URL doesn’t change. This new dispatcher

function needs to be connected to the Birdy User module, so we need to import

birdy.model to the controller in the /src/opa.conf file:

birdy.controller:importbirdy.{model,view}[...]

We’ll now turn our attention to the view in /src/view/page.opa,

as we need to add two functions used—Page.topic_page and `Page.user_page`—that will construct pages for a given topic and user, respectively.

Those two pages are similar in the sense that they display a list of messages,

so let’s enclose this common feature in a function:

privatefunctionmsgs_page(msgs,title,header){msgs_iter=DbSet.iterator(msgs)msgs_html=Iter.map(MsgUI.render,msgs_iter)content=<divclass=container><divclass=user-info>{header}</div><divid=#msgs>{msgs_html}</div></div>page_template(title,content,<></>)}

Here, we’ve taken a list of database results as msgs and converted

them to an iterator with DbSet.iterator. Then we converted those results

to rendered messages using Iter.map with the MsgUI.render function.

Finally, we built the HTML structure of our messages page to display messages.

With the messages page in place, we can easily build a page for a topic:

functiontopic_page(topic_name){topic=Topic.create(topic_name)msgs=Msg.msgs_for_topic(topic)title="#{topic}"header=<h3>{title}</h3>msgs_page(msgs,title,header)}

Now we need a function to convert a string into a Topic.t type, which we place

in the Topic module in /src/model/topic.opa:

functionTopic.t create(string topic){topic}

We create a page for a user in a similar way, but if the requested user does not exist, we will display an error page:

functionuser_page(username){match(User.with_username(username)){case{some:user}:msgs=Msg.msgs_for_user(user)title="@{username}"header=<h3>{title}</h3>msgs_page(msgs,title,header)case{none}:page_template("Unknown user: {username}", <></>,alert("User {username} does not exist", "error"))}}

We need to add a function to get a user with a given username to the User

module:

functionoption(User.t)with_username(string name){?/birdy/users[{username:name}]|>Option.map(mk_view,_)}

And that’s it! By creating some messages and then clicking on the links contained in published messages or entering appropriate URLs by hand, you can verify that the pages work and display relevant messages.

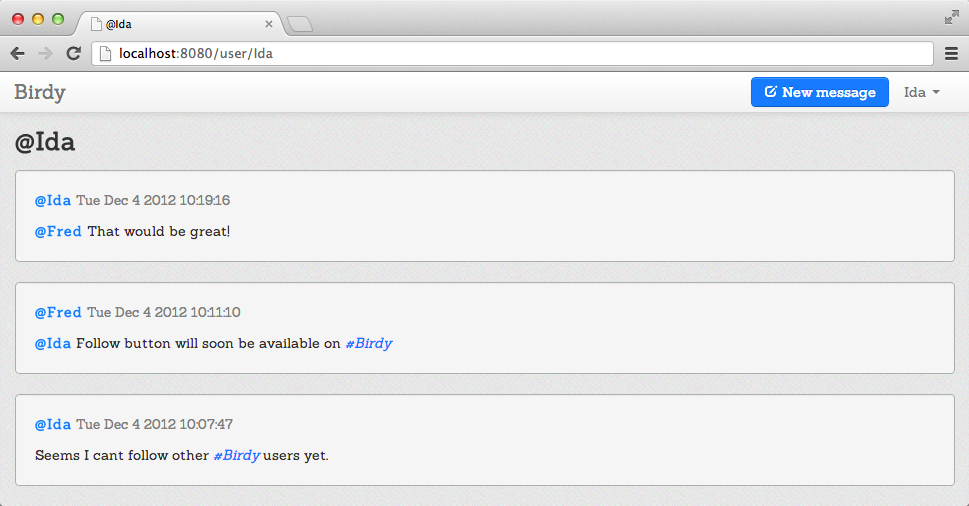

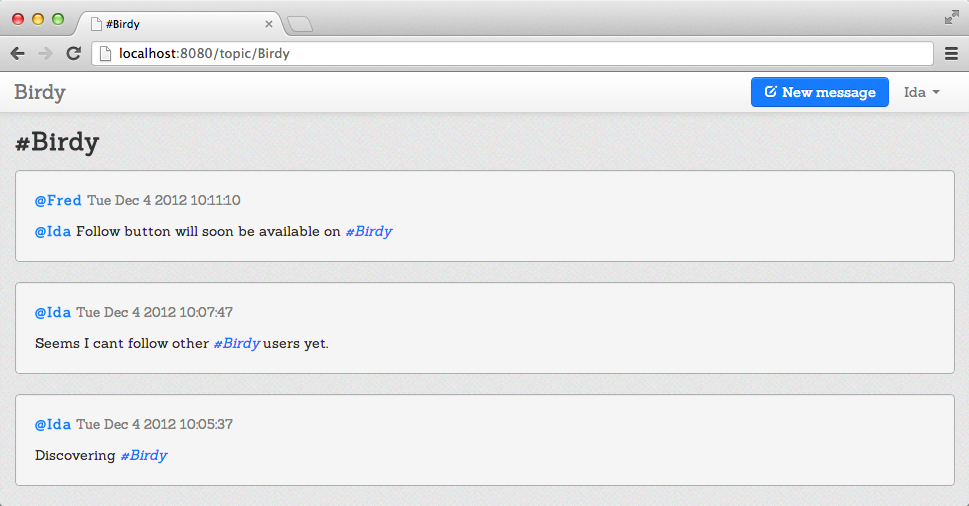

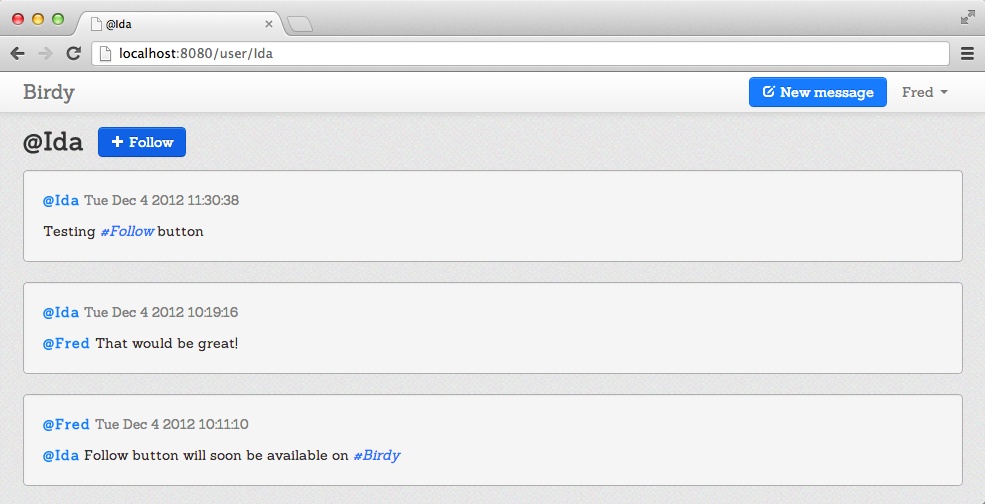

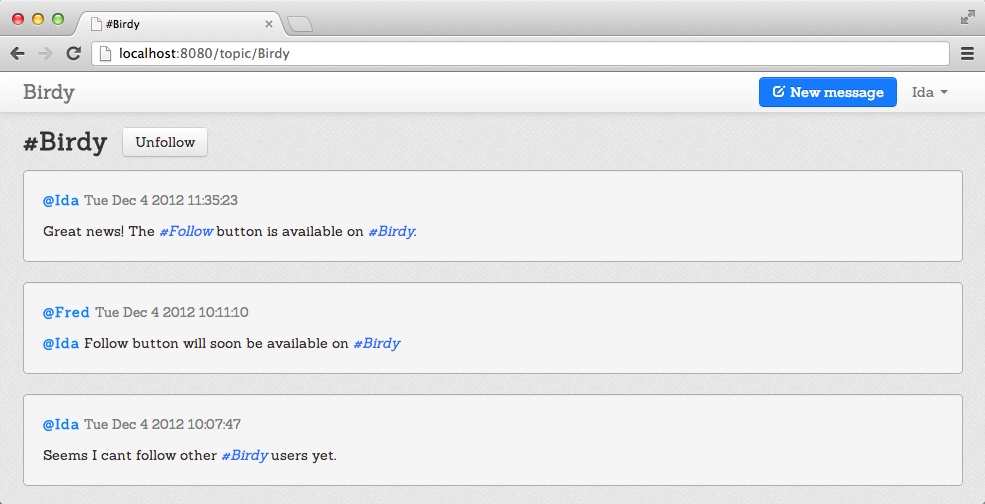

Figure 10-2 is an example of a user page and Figure 10-3 is an example of a topic page.

Following Users and Topics

Now we would like to add one more micro-blogging feature to our Birdy app: the ability to follow other users and topics. Our plan is to:

- Write functions to follow users.

- Write functions to follow topics.

- Build a Follow button and add it to the user interface.

The ability to follow will apply to logged-in users only, so first

let’s write a function in the User module that will allow us to perform some action with logged-in users:

privatefunctiondo_if_logged_in(action){match(get_logged_user()){case{guest}:voidcase{user:me}:action(me)}}

Following Users

Now let’s use the preceding function to write a function to follow a user:

functionfollow_user(user){functionmk_follow(me){/birdy/users[{username:me.username}]/follows_users<+user.username}do_if_logged_in(mk_follow)}

The function mk_follow allows us to update the list. As you saw in Inserting/Updating Data, <+ is used to add an element at the end of the list. We then

use the do_if_logged_in function to apply it only to logged-in users.

Using the same method, let’s write a function that allows us to unfollow a followed user:

functionunfollow_user(user){functionmk_unfollow(me){/birdy/users[username==me.username]/follows_users<--[user.username]}do_if_logged_in(mk_unfollow)}

Here we use <-- to remove the element from the list.

The next function we would like to write is a function that allows us to check if one given user A is followed by one logged-in user B:

functionisFollowing_user(user){match(get_logged_user()){case{guest}:{unapplicable}case{user:me}:if(user.username==me.username){{unapplicable}}else{if(/birdy/users[username==me.usernameandfollows_users[_]==user.username]|>DbSet.iterator|>Iter.is_empty){{not_following}}else{{following}}}}}

This function applies to logged-in users and returns unapplicable for non-logged-in users as well as

for the logged-in user B. The function looks for users who have the same username as logged-in user B and who follow given user A, and returns a DbSet that we transform to an iterator to check if the result is empty or not. If the result is empty, the function returns not_following; otherwise, it returns following.

Following Topics

Now we’ll use the same methods we just used to write the follow_topic, unfollow_topic, and

isFollowing_topic functions:

functionfollow_topic(topic){functionmk_follow(me){/birdy/users[{username:me.username}]/follows_topics<+topic}do_if_logged_in(mk_follow)}functionunfollow_topic(topic){functionmk_unfollow(me){/birdy/users[username==me.username]/follows_topics<--[topic]}do_if_logged_in(mk_unfollow)}functionisFollowing_topic(topic){match(get_logged_user()){case{guest}:{unapplicable}case{user:me}:if(/birdy/users[username==me.usernameandfollows_topics[_]==topic]|>DbSet.iterator|>Iter.is_empty){{not_following}}else{{following}}}}

Follow Button

The last thing we need to address is the Follow button. Let’s return to

/src/view/page.opa and modify our msgs_page function as follows:

privatefunctionmsgs_page(msgs,title,header,follow,unfollow,isFollowing){recursivefunctiondo_follow(_){_=follow();#follow_btn=follow_btn();}andfunctiondo_unfollow(_){_=unfollow();#follow_btn=follow_btn();}andfunctionfollow_btn(){match(isFollowing()){case{unapplicable}:<></>case{following}:<aclass="btn"onclick={do_unfollow}>Unfollow</a>case{not_following}:<aclass="btn btn-primary"onclick={do_follow}><iclass="icon icon-white icon-plus"/> Follow</a>}}msgs_iter=DbSet.iterator(msgs)msgs_html=Iter.map(MsgUI.render,msgs_iter)content=<divclass=container><divclass=user-info>{header}<divid=#follow_btn>{follow_btn()}</div></div>{if(isFollowing()=={unapplicable}&&Iter.is_empty(msgs_iter)){<divclass="well"><p>You don't have any messages yet. <adata-toggle=modal href="#{MsgUI.window_id}">Compose a new message</a>.</p></div>}else<></>}<divid=#msgs>{msgs_html}</div></div>page_template(title,content,<></>)}

We add the do_follow and do_unfollow functions that take the user or topic and reconstruct

the Follow button, and then we write the follow_btn function that takes the state returned by

isFollowing and returns the corresponding HTML. We use Bootstrap classes to distinguish the Follow and Unfollow buttons by color. We create a <div> element with a #follow_btn identifier and call the follow_btn function. For a better user experience, we create a special page for the user

(first-time) who doesn’t have any messages. We display a short notification about it and suggest

that he create a new message. If the user has messages, they are displayed on the page.

Now let’s call the follow, unfollow, and isFollowing functions in the topic_page

and user_page functions:

functiontopic_page(topic_name){topic=Topic.create(topic_name)msgs=Msg.msgs_for_topic(topic)title="#{topic}"header=<h3>{title}</h3>functionfollow(){User.follow_topic(topic)}functionunfollow(){User.unfollow_topic(topic)}functionisFollowing(){User.isFollowing_topic(topic)}msgs_page(msgs,title,header,follow,unfollow,isFollowing)}functionuser_page(username){match(User.with_username(username)){case{some:user}:msgs=Msg.msgs_for_user(user)title="@{username}"header=<h3>{title}</h3>functionfollow(){User.follow_user(user)}functionunfollow(){User.unfollow_user(user)}functionisFollowing(){User.isFollowing_user(user)}msgs_page(msgs,title,header,follow,unfollow,isFollowing)case{none}:page_template("Unknown user: {username}", <></>,alert("User {username} does not exist", "error"))}}

Compile and run your Birdy application to check the Follow button. Figure 10-4 shows a user’s page viewed by another logged-in user who doesn’t follow him. Figure 10-5 shows the topic page that is followed by the logged-in user: the Follow button has turned into an Unfollow button.

This concludes our detailed tour of the functions we have implemented in Birdy. Now it’s time to play.

Exercise

Remember when we talked about enforcing page refresh to display a user’s new messages in Rendering Messages? We solved half of the problem. However, what if some other user entered a message that should be displayed on the current page? In such a case, Twitter displays a window saying that there are N new messages and by clicking on it one can see them.

Apply what you learned when writing the chat application in Chapter 6 to display all relevant messages in real time in Birdy.

Summary

In this chapter you learned about data storage and querying. Specifically, you learned how to:

- Declare, insert, update, read, and acquire data

- Store and fetch relevant messages

- Handle navigation

- Build functions to follow and unfollow users

We hope that by reading this book you have learned many things about Opa and web programming. Programming is a never-ending subject, and our goal was to give you enough knowledge to fly on your own and build great applications or even companies.

As a last reminder, there are many online resources to help you in your quest to build great applications in Opa, including the following:

- The Opa forum, available at http://forum.opalang.org, is a great start.

- The online documentation at http://doc.opalang.org is the best way to browse the standard library.

- The GitHub repository at http://github.com/MLstate/opalang hosts a wiki and provides a way to report issues.

That’s all, folks!