Chapter 2. Opa Fundamentals

In Chapter 1, you wrote your first Opa program. That will always return the same value, Hello, world, as a main title.

The value itself is:

<h1>Hello, world</h1>This value is an HTML fragment, one of the primitive values of Opa. The second myapp application you saw in Chapter 1 also contains HTML values in src/view/page.opa:

content=<divclass="hero-unit">Page content goes here...</div>

Here, the HTML value is named content, so it can be reused later.

Tip

Opa also offers a universal closing tag, </>, that you can use to close any tag. In the previous case, you could have written:

content=<divclass="hero-unit">Page content goes here...</>

Let’s discover the Opa values right now.

Primitive Values

As with most programming languages, Opa supports strings, integers, and floats, but Opa also supports native web values such as HTML and CSS elements. As you can see, comments in Opa consist of text preceded by double slashes, //:

"hi"// a string12// an integer3.14159// a float<p>Paragraph</p>// an HTML fragment#id// a DOM identifiercss{color:black}// a CSS property

HTML values are fragments of HTML5. Each fragment has an opening tag such as <p> and a closing tag such as </p>. The <p> tag is the tag that defines a paragraph.

We will provide a more complete list of tags shortly, but for now here are the main ones (see Table 2-1):

| Tag | Definition |

| Video item |

| Paragraph |

| Level 1 title (header) |

| Level 2 to 6 title (header) |

| Generic container |

| Inline generic container |

| List of unnumbered items |

| List item |

| Link |

You can embed HTML fragments, as shown here:

<div>Content <span>button</span><ul><li>First item</li><li>Second item</li></ul></div>

Warning

Be careful to properly close tags when embedding them: the first one opened should be the last one closed. This is true for all except a handful of tags that don’t necessarily need to be closed, such as <meta>, <img>, <input>, and some others.

Tags can have attributes. For instance, the a tag has the href attribute, which specifies the HTML reference it points to.

So to insert a link to http://google.com, you can write:

<ahref="http://google.com">Google</a>

HTML fragments, when grouped together, create a document. We will discuss all the relevant properties of a document in Chapter 5. For now, it’s sufficient to know that tags can have a unique ID using the id attribute.

For instance, <div id="iamunique">...</div> creates an iamunique ID that can be accessed by the DOM identifier #iamunique.

All Opa values can be named, to be reused later in your program. Here is an example:

customer="John Doe"price=12.99tax=price*0.16total=price+tax

Note that you can play with these basic values by inserting them into the former Hello, World application. For instance, try:

Server.start(Server.http,{title:"Hello, world",page:function(){customer="John Doe";price=12.99;tax=price*0.16;total=price+tax;<p>Customer{customer}has to pay{total}</p>}})

Here are a few things to note regarding the preceding code:

- Traditionally, each line of computation ends with a semicolon. There is ongoing debate over whether this is a good thing or not. In Opa, you can omit the semicolons if you want to.

-

The end of the computation generates an HTML fragment and uses a mechanism known as string expansion to insert values (known as

customerandtotal) inside the text. As you can see, you use braces for string expansion in Opa.

Dynamic Content

Thus far, you have learned how to build static content. Each time you run your application by pointing your browser to http://localhost:8080, you get the same content.

The Web was born this way, although originally the mechanism was different, as developers used to write static HTML content within files and used a static server program, such as Apache, to serve the files to users’ browsers. The pages would use the HTML <a> tag to create links between pages or between different sites.

But we are here to build applications. An application consists primarily of web values that can do the following:

- React to the users’ actions.

- Store data (e.g., user accounts) permanently in a database.

The most basic user action is the mouse click. Modern applications do not use the link tag to react to users’ mouse clicks. So we will use an HTML attribute, onclick, which is present in many tags.

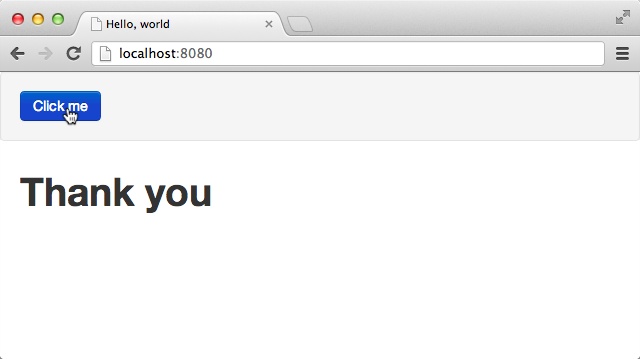

Let’s create a small application that displays “Thank you” once the user clicks on “Click me”:

Server.start(Server.http,{title:"Hello, world",page:function(){<divonclick={function(_){#thankyou="Thank you"}}>Click me</div><divid="thankyou"/>}})

Run the application now! You should see something similar to Figure 2-1. You can restart your application by refreshing the page in your browser.

The most important new line in this program is:

<divonclick={function(_){#thankyou="Thank you"}}>Click me</div>

which combines two things:

-

The HTML value

<div onclick={...}>Click me</div> -

The resultant action,

function(_) { #thankyou = "Thank you"}

We won’t explain every bit of code in that line right now (you will know everything by the end of this chapter), but it is important to note the following:

-

You bind Opa code to the

onclickevent with the opening braces. -

You recognize that

#thankyouis a DOM identifier value, and you can assign content to the DOM identifier like you do for other values.

To continue our quest, you need to understand two powerful programming mechanisms:

- Records, which allow you to structure data

- Functions, which help you to organize your application code

It turns out that you are already using both! The record lies behind the following:

{title:...,page:...}

The function was already used twice:

- For the page that displays by default

- Again, when you click on “Click me”

Records

One of the main features in terms of Opa structuring values is records. As you will see throughout this book, Opa records are extremely powerful and you will use them a lot. Their nickname is “Power Rows.”

Records are a set of values, each defined by its field name. Values for each field can be of any type, including records or even more complex types:

// this is a record with 3 fields{first_name:"John",last_name:"Doe",age:18}// this is a record with 2 fields, one of them being a record itself{product:"book",price:{base: 29.99, tax: 4.80 }}

Naturally, it’s useful to name values so that you can construct more complex ones step by step:

level1_pricing={base:29.99,tax:4.80}book={product:"book",price:level1_pricing}

As we said earlier, all programs, including the very first one you wrote, use records:

{title:"Hello, world",page:function(){<h1>Hello, world</h1>}}

The code includes a record that has two fields: title, which is a string, and page, which is another value that we will discuss next.

Records in Opa can be extended, that is, you can add new fields later in your program:

level1_pricing={level1_pricingwithtotal:29.99+4.80}

Introduction to Types, and More About Records

Now that you know about basic values and records, it’s time to learn more about types. You should be familiar with types. You have seen strings and integers, and as a developer, you know they represent different types of values. So does Opa!

"Hey"// this has type string10// this has type int

You can enforce types by writing them if you want, but in most cases, Opa infers them for you and you can safely omit them:

string text="Hey"

Opa uses the type information to help you. For instance, Opa won’t let you mix different types as doing so is either a bug or a bad coding practice. Try writing:

1+"Hello"

and see how Opa reacts.

Often, the mistake is not straightforward and involves two different parts of the code. Opa handles this particularly well. If you write:

a=1;b="Hello";a+b

Opa will tell you what the error is and why it occurred. Try it!

You will get the following error message:

Error:File"typeerror.opa",line3,characters1-5,(3:1-3:5|21-25)Type Conflict(1:5-1:5)int(2:5-2:11)string The types of the first argumentandthe second argument offunction+of stdlib.core should be the same

The preceding error message says that:

-

1 is of type

int(this was inferred). -

“Hello” is of type

string(this was inferred as well). -

The type error exists in expression

a + b. - Both arguments of function + should have the same type.

To make it easier to read type error messages, you can name types:

typemytype=string mytype text="Hey"

This becomes useful with records. Each record (as with all other values in Opa) has its corresponding type, even though you will not have to spell it out. For instance:

{title:"The Firm",author:{first_name: "John", last_name: "Grisham" }}

has type:

typebook={string title,{string first_name,string last_name}author}

which you should read as: “Type book is a record with two fields:

title and author. Field title has type string, whereas

author is a field whose type is a record with two string fields:

first_name and last_name.”

After such type declaration, you could as well write:

book some_book={title:"The Firm",author:{first_name: "John", last_name: "Grisham"}}

In the preceding code, you gave a name (some_book) and an explicit type (book) to the

value shown previously.

Sometimes the expressions describing record fields can get long and complex:

author={first_name:long_expression_to_compute_first_name,last_name:long_expression_to_compute_last_name}

In this case, to improve readability we will often compute and bind them first:

author=first_name=long_expression_to_compute_first_name last_name=long_expression_to_compute_last_name{first_name:first_name,last_name:last_name}

For this frequent case where fields are initialized from variables with the same name, Opa provides an abbreviation and allows you to replace the last line in the preceding code with:

{~first_name,~last_name}

Here {~field, ...} stands for {field: field, ...}. If all fields

are constructed in this way, you can even put the tilde in front of the

record and write:

~{first_name,last_name}

You will often construct one record from another, as in:

grisham={first_name:"John",last_name:"Grisham"}steinbeck={first_name:grisham.first_name,last_name:"Steinbeck"}

Opa facilitates this frequent-use case with the following construction:

{recordwithfield1:value1,...fieldN:valueN}

The value of this expression is the same as that of record except

for fields field1 to fieldN, which are given values value1 to

valueN. For instance, the steinbeck value in the previous code can be replaced

with:

steinbeck={grishamwithlast_name:"Steinbeck"}

Records are ever-present in Opa. Their power comes from the fact that all record manipulations are typechecked:

- You cannot try to access a field that does not exist.

- You cannot misspell a field’s name (or rather, you can, but the compiler will point out your mistake).

-

You cannot try to access a field in a type-incompatible way (i.e., as a

stringwhen it is anint).

This power does not cost you anything, as you can just use records as you would in a dynamic language without ever explicitly declaring their types.

A Brief Introduction to Variants

One last aspect of the mighty record is variants.

Variants are the way to properly represent multiple-choice lists.

Imagine that you want to define a currency type for an online store that handles payments in US dollars (USD), Canadian dollars (CAN), and British pounds (GBP).

You could use the string type to define that value.

But what if you write the following at some point?:

price1={amount:4.99,currency:"USF"}

The typo will remain unnoticed, the compiler won’t complain, and the related bugs will have to be hunted down during the app testing. As a result, depending on the code structure, the item might not be billed.

Instead, you can write:

typecurrency={USD}or{CAN}or{GBP}// here price is a previously defined book valueprice={amount:29.99,currency:{USD }}

The or keyword states that the type currency will be one of the three options: USD, CAN, or GBP.

Opa provides very useful typechecking for variants. For instance, it checks that values are only allowed variants or that you always take all variants into account.

You should use them instead of strings as much as possible.

We will discuss variants in more detail in Chapter 7.

Functions: Building Blocks

Before we move on to the main example of this part of the book, let’s take a look at some building blocks of the language that you will need to understand.

Structuring programs is very important. You never want to write your program as a single piece of code; rather, you want to break it down into blocks. The two main block levels are:

- The modules (for bigger applications, which we will take a look at later)

- The functions (inside modules and for any application)

Using functions, you make your program more readable and your code reusable.

Functions are written and called very easily:

// the following function computes the tax of a given pricefunctioncompute_tax(price){price*0.16;}// we now can call (or invoke) the compute_tax function as much as we wanttax1=compute_tax(4.99);tax2=compute_tax(29.99);

Here we have the function keyword, then the name of the function, compute_tax, and a list of its arguments in between parentheses. In this case, there’s only one argument: price, followed by the function body inside curly braces. Opa does not have an explicit return keyword and instead adopts the convention that the last expression in the function is its return value. Here, it means the function returns the value of price times 0.16.

Warning

The open parenthesis in function invocation must immediately follow the function’s name, with no spaces in between.

The use of functions in this example means that when the tax level changes, you only have to modify one line of your program, instead of chasing down all the places where the tax is computed in your application. For this reason, you should always use functions whenever you can, and never copy and paste code. Each time you are tempted to copy and paste your code, you should use a function instead.

Note

You may have noticed that we introduced a semicolon at the end of line. This is because we are getting into real programs, which involve several computations. Therefore, we use a semicolon to indicate that a given computation is finished, and that we can proceed to the next one. In many cases, semicolons can be omitted and there is still no consensus on whether it’s a good or a bad design decision. You have to find your own coding style!

Functional Programming

The coding style that Opa promotes is called the functional programming style. Among other things, this means that functions play a central role and are very powerful. The functional programming style is often described as elegant, and we will show you why. But for now, it helps to know that the main difference between functional programming and classic programming is that in the former, values are not mutable by default.

For instance, in Opa, the main definition of values such as the following is the binding of a value:

name = expressionHowever, this does not create a variable in the classic programming style. The previous expression just means we give name

to the expression and can subsequently use name to refer to the

value denoted by expression.

The main reason for this is that immutable code is easier to reason about. In the absence of variables, the result of a function depends only on its arguments. Contrast this with a function whose behavior depends on a bunch of global variables. This is one of the main reasons why in the excellent book Effective Java (Addison-Wesley), where mutability is the norm, the author advises that you use immutability whenever possible, explaining:

There are many good reasons for this: immutable classes are easier to design, implement, and use than mutable classes. They are less prone to error and are more secure.

Our argument for immutability also concerns scaling web applications and services. The architecture prevalent today for scaling up is to use stateless servers that can be multiplied without limits. Should a server fail, a new one pops in, and traffic is directed to random servers. But this implies that no application has unsaved data or state. The problem here is that mutable variables often contain such information, and this information will not be synchronized with these other servers unless the synchronization has been done manually (which is a painful process). Therefore, not using state (and variables) is a good programming practice, today more than ever.

Bindings and functions are deeply linked. Let’s play with them a bit by writing a function that computes the Euclidean distance between two points:

functiondistance(x1,y1,x2,y2){dx=x1-x2 dy=y1-y2Math.sqrt_f(dx*dx+dy*dy)}

In the preceding code, the function distance first binds the value x1-x2 to dx, and similarly binds y1-y2 for dy, and then uses

dx and dy in the final expression. Math.sqrt_f is a function from the Math

module (more about modules later) of the standard library for computing the square root

of a given floating-point number.

In fact, the bindings inside functions can include local functions, so the previous

could be rewritten as follows, introducing the intermediate sqr function:

functiondistance(x1,y1,x2,y2){dx=x1-x2 dy=y1-y2functionsqr(x){x*x}Math.sqrt_f(sqr(dx)+sqr(dy))}

Finally, functions can be anonymous, in which case they do not have a name

but they can be used inside any expression. The anonymous variant of the incr

function in the preceding code would be:

function(x){x+1}

This variant can be stored in a named value:

incr=function(x){x+1}

Anonymous functions are particularly useful for passing arguments to other functions; for instance, to specify how the app should react to a user’s actions.

As you can see, functional programming allows much better control of programming scope. In pure JavaScript, you would write:

var foo;if(x==10){foo=20;}else{foo=30;}

This would introduce a variable, and then set its value, even if foo is unmodified in the rest of the program. In Opa, you simply write:

foo=if(x==10){20;}else{30;}

The preceding code will have the guarantee that foo is not further modified.

Functional + Typed

At the beginning of this chapter, we played with types. Opa is indeed a statically typed language. This means that every value has a type assigned to it, and this assignment takes place at compilation time. Being typed is orthogonal to being a functional language. This is important, as the compiler uses this information to detect and report all kinds of flaws in the program.

So why were there no types in the code snippets shown in the preceding section? In Opa, explicitly writing

types is often not required as the types are inferred in the absence of explicit type annotations. This means you could write the distance function with explicit types as follows (the additions are in bold):

functionfloatdistance(floatx1,floaty1,floatx2,floaty2) {floatdx = x1 - x2floatdy = y1 - y2 Math.sqrt_f(dx*dx + dy*dy) }

Arithmetic operators work both for int and for float types, so the only reason

all values are given the float type is because of the Math.sqrt_f function

(its int counter-part is called Math.sqrt_i).

The type inference that the compiler performs may not seem too impressive on this trivial example, but in later chapters, when we deal with more complex types, its benefits will become more pronounced. The type checker algorithm that performs type inference and verification is a very complex and sophisticated algorithm—especially the one in Opa, which required tremendous effort on the part of Opa developers to specify and implement.

Summary

In this chapter, we learned the fundamental concepts of Opa, in particular:

- How to use records to structure data

- How to write Opa functions

- Why Opa is functional and why this is important

- What types str and why they are important

In the next chapter we will talk about servers: how to handle resources and different URLs of an application.