Chapter 7. More Advanced Features of Opa

Before we dive into developing Birdy, you need to learn few more things about Opa. In this chapter, we will discuss more complex types, which will help you deal with more complex data that you will encounter in this part of the book.

Learning More About Types

You learned about primitive values (int, float, string) in

Primitive Values and about records in Records.

Now it is time to extend your type arsenal.

Variant Types

Variant types, as the name suggests, allow you to express values that can take several different variants. Probably the simplest such type is a boolean value, which is defined in Opa as follows:

typebool={false}or{true}

The variants are separated with the or keyword and the variants

themselves are just regular record types. Lack of a type for a given

field implies it is of type void (which we covered in Event Handlers), so the preceding code can also be written as follows:

typebool={void false}or{void true}

Such void-typed fields make little sense in regular records, as

the field value carries no information. However, in variant types

they make perfect sense, as their presence is important

and differentiates between variants.

In this simple form, with all variants having just one field of type

void, those types correspond to enumeration types, as you may

know from other programming languages. Here is another example

from the standard Opa library:

typeDate.weekday={monday}or{tuesday}or{wednesday}or{thursday}or{friday}or{saturday}or{sunday}

However, note that in Opa we are not restricted to such degenerated records.

For instance, say we need to keep track of the logged-in user, and

suppose we have a User.t type describing the user. We can keep track of the logged-in user with the following type:

typeUser.logged={guest}or{User.t user}

Example values of type User.logged are {guest} and {user: u}

if u is a value of type User.t. Of course, we are not restricted

to single-field records.

Pattern Matching

But how can we work with such values? How do we figure out which variant was used to construct the value; for instance, to check whether the user is logged in?

This is where pattern matching comes in handy. Pattern matching is a way

of analyzing and decomposing values. At first, it can seem deceptively

similar to switch statements, which you may know from languages

such as JavaScript, C, and Java, but as you will see later in this

chapter, pattern matching can do much more than that.

Let’s look at some examples. We’ll start with Boolean values:

functionint int_of_bool(bool b){match(b){case{true}:1case{false}:0}}

Here, the match is followed by an expression (it does not need to be

a simple variable) that we want to match against, put in parentheses. This is followed by a number of different matching cases

introduced with the case keyword, followed by the matched pattern,

a colon, and the expression with the result for that particular case.

Now let’s match a value of type User.logged:

functionstring greet(User.logged u){name=match(u){case{guest}:"guest"case{user:user}:User.get_name(user)}"Hello,{name}"}

In this second pattern-matching case, user will be matched against

the value of the user field in the record u and can be accessed

in the expression User.get_name(user). Just as with

regular records, you can abbreviate {user: user} to ~{user} in the

pattern.

With pattern matching, there are a few things to keep in mind. First, the pattern-matching part of the code is an expression,

not a statement (as switch is in many languages). This means it is

perfectly permissible to write the previous function as:

functionstring greet(User.logged u){"Hello, "+match(u){case{guest}:"guest"case{user:user}:User.get_name(user)}}

Second, the compiler makes sure that all possible cases are covered by the given patterns, and otherwise will fail with a nonexhaustive pattern-matching error. This means that if at some point you need to add to the program a new feature that requires extending some type with an additional variant, you can safely do so. The compiler will then point out all the places that need to be adjusted because of this change.

Note that in the vocabulary of languages such as Java and C#,

pattern-matching combines features of if, switch,

instanceof/is, and casting, but without the usual (type)

safety issues of the last two operations.

Polymorphic Types

In this section, we will examine at an important extension of variant types: polymorphism. We will start with a simple definition:

typenullable_int={null}or{int value}

Many programming languages allow a special null value as

a value for any type. Not so in Opa. The type in the preceding code describes

nullable integers by allowing two types of values: {null}

and {value: x} for any integer x.

Tip

Yes, you guessed right: Opa does not have the notorious problem

of null pointer exceptions. Using types like the one

in the preceding text for situations when you really need “nullability” has one

big advantage: while pattern-matching on such values, you will be prompted

to explicitly handle the null case.

That seems like a useful definition, but we may need null

for values of types other than just int. Repeating it for every

single type where we need this feature would be terribly inefficient.

Fortunately, we can do better. Here is a definition from the standard Opa library:

typeoption('a)={none}or{'asome}

Here, 'a is a type variable (type variables always begin with a single

apostrophe) and the definition of option is parameterized by

this type variable. It has two variants: {none}, meaning no value,

and {some: x}, representing an existing value x of the parameterized

type 'a.

We call such a type a polymorphic type as we can substitute the type

variable, 'a, with an arbitrary type to obtain a concrete type.

For instance, you can get optional integers by instantiating 'a with

int to obtain option(int).

Also note that, thanks to Opa’s type inference, you

will not need to spell out the type names in many cases. If you just write {some: 5}, the

compiler will be able to figure out that this is a value of type

option(int).

It’s important to realize that you can also write polymorphic functions like this one:

functionbool is_some(option('a)v){match(v){case{some:_}:truedefault:false}}

The underscore in the second pattern means we do not care about

this value. It allows us to avoid the unused variable warning

that would be generated if we used a {some: value} pattern with

an unused variable value. It also clearly shows that the value

itself is irrelevant. Note that we do not inspect the value, which is why

the function can retain a fully generic option('a) type for

its v argument and allows us to write:

b1=is_some({some:5})// b1 == trueb2=is_some({some:"Text"})// b2 == trueb3=is_some({none})// b3 == false

Another new feature that we used in the previous example is the catchall default

pattern, which always needs to be specified as the last pattern

and handles all the remaining cases.

Note that many functions that handle options are already defined in the standard library; one of these is Option.default, which gets the some case and returns the default value of none:

Option.default(default_value,option_value)

Warning

Use default sparingly. It is important to use

it only when you really want to handle “all remaining cases”:

a typical use is when you want to distinguish between one particular

variant and “everything else.”

When not using default, the Opa typechecker always ensures that

pattern-matching cases are complete. For instance, the following program:

option(void)v=nonematch(v){case{none}:1;}

defines an option but does not check for the {some: ...} case.

If you try to compile it, the Opa compiler tells only this:

Warning pattern File"match1.opa",line2,characters1-30,(2:1-4:1|23-52)Incomplete pattern matching:case{some}is missing Error:Fatalwarning:'pattern'

The option type above has only one type variable, but types with several of them are possible. For instance, here is another

type from the standard Opa library:

typeoutcome('ok,'ko)={'oksuccess}or{'kofailure}

This represents an outcome of some operation, which can be either success, with the resultant value, or failure, with

an indication of the problem that occurred. The types of the

values returned in case of success and in case of failure can

be different. For example, an arithmetic operation could produce

an int if successful or a string indicating the type of

problem that occurred. Such an instance would have type

outcome(int, string).

Recursive Types

The types you’ve learned about so far allow you to only express values with a fixed, finite structure. But what about things like lists and trees? This is where recursive types come to the rescue.

A list is a finite sequence of values of a given type. In Opa, it is

defined as:

typelist('a)={nil}or{'ahd,list('a)tl}

This is a polymorphic type, with list('a) being either an empty list,

{nil}, or an element hd of type 'a followed by tl of type

list('a). This definition of a type expressed in terms of itself

is what gives it the name recursive type.

Traditionally, the first element of a list is called the head

and the remainder is called the tail, hence the field names hd

and tl, respectively.

Tip

Opa does not have a type of fixed-size array, and lists are used instead. In fact, lists are used very extensively in Opa, so it is important that you become comfortable with using them.

So how do we represent a list with three elements: 1, 2, and 7?

l1={hd:1,tl:{hd: 2, tl: {hd: 7, tl: nil}}}

This is not very readable, so Opa supports special syntax for lists that enables us to write the preceding code equivalently as:

l2=[1,2,7]

Opa also offers [head | tail] syntax for a list with a given head

and given tail, so we can write:

l3=[0|l2]// == [0, 1, 2, 7]

or even:

l4=[0,3|l2]// == [0, 3, 1, 2, 7]

Recursive types are very useful, so we will conclude this section with an illustration of how to use them to express binary trees (of arbitrary type):

typebin_tree('a)={leaf}or{'avalue,tree('a)left,tree('b)right}

When writing functions that do pattern matching on recursive types, the functions themselves will often use recursion. Since this is a new and very important concept, we will take a closer look at them in the next section.

Recursive Functions

To pattern-match on recursive types, such as the list introduced in the preceding section, we just follow the same rules we used for records:

match(l){case{nil}:...case~{hd,tl}:...}

Here, Opa also offers syntactic sugar, allowing us to replace the preceding code with:

match(l){case[]:...case[hd|tl]:...}

The interesting point here is that the tl binding in the second case

will be of the same type as the whole list l. To make this

more concrete, let’s try to write a function that computes the length

of a list:

functionint length(list('a)l){match(l){case[]:0case[hd|tl]:?}

The case when the list is empty is easy, as we just return 0 (since

that is the length of an empty list). However, how do we handle

the second case? What is the length of a list with an element

hd followed by a list tl? Well, it is the length of tl

plus one (for hd). This is exactly what we can write in Opa,

too (we replace hd with an underscore, as we do not need to inspect

the head of the list and hence do not need this binding):

functionint length(list('a)l){match(l){case[]:0case[_|tl]:1+length(tl)}

Note how the length function is called in the definition

of the length function. This is what makes it a recursive

function. While writing such functions, we need to be

careful, though. What would happen if we just wrote the following?:

functionf(){f()}

Invocation of such a function would cause an infinite loop,

just as if we wrote while (true) { } in a

language like Java.

One final remark: all top-level functions (i.e., functions

that are defined in a file or in a module, but not local

functions that are defined within other functions)

can use recursion directly. However, if you

want to use recursion in a local function, you will need

to precede function with the recursive keyword.

For instance, we can write the following sample functions:

functionf(x){if(x==1){1;}elseg(x)}functiong(x){f(x-1)}functionf(x){recursivefunctionaux(x){if(x==1){1;}elseaux(x-1)}aux(x)}

What About Loops?

If you’re familiar with some programming languages, you may have been wondering why we have not talked about loops yet. The reason is simple: there aren’t any in Opa.

If you have no prior experience with functional programming, the notion of a lack of loops can be truly confounding; how can you write programs without loops? It turns out that just as you can do without variables [see Bindings Versus Variables], you can also do without loops.

In Chapter 6, you wrote a function to compute the length of a list using recursion instead of iteration (i.e., loops). It turns out that recursion is a very powerful notion and it can replace loops altogether.

Opa has an even more powerful weapon in its arsenal: iterators. Iterators in Opa have a slightly different meaning than in imperative languages; they are functions that capture some important schema for manipulating collections.

To make this discussion more concrete, let’s discuss three important iterators on lists: List.filter,

List.map, and List.iter:

-

List.filtertakes a functionfand a listland produces a new list containing only those elements oflfor whichfreturnstrue. In other words, it filters elements of a list based on a given predicate. -

List.maptakes a functionfand a listland produces a new list by applyingfto all elements ofl. So, ifl = [x1, x2 ,... xN],List.map(f, l) == [f(x1), f(x2), ... f(xN)]. -

List.itertakes a functionfand a listl. It does not produce any result, but it invokesfon all elements ofl. It is equivalent to aforeachloop in other languages.

Here is a summary of those iterators:

List.map(_*3,[1,2,3,4])=[3,6,9,12]List.filter(_<3,[1,2,3,4])=[1,2]List.iter(f,[1,2,3,4])=f(1);f(2);f(3);f(4)

Now that you’ve learned about pattern matching, polymorphic types, iterators, recursive types, and functions, it’s time to apply this knowledge to a real project.

Bigger Projects

In Coding a Mini Wikipedia of this book, all the applications we developed, except for the chat app, consisted of a single source file. This is fine for very simple projects, but it’s unlikely to work very well for more elaborate ones. It is time to learn how to create such projects.

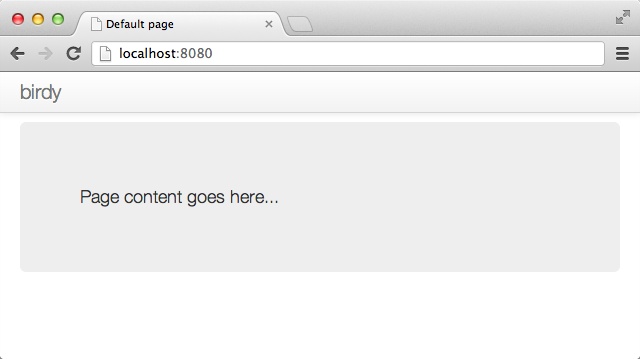

The overhead of creating such projects is minimal, but Opa features a tool that helps in setting up new projects. To get started, change to a root directory in which you can create the new project, and enter the following:

Tokyo:opa henri$ opa create birdy --template mvcThis will create a new birdy directory containing a complete scaffolding for it. The resultant directory is similar to the one in Chapter 6 and has the following structure:

+- birdy | +- Makefile | +- Makefile.common | +- opa.conf | +- resources | | +- css | | | +- style.css | +- src | | +- model | | | +- data.opa | | +- view | | | +- page.opa | | +- controller | | | +- main.opa

This newly created project includes the following:

- A Makefile file for the project (which can be customized)

- A generic Makefile.common file (which usually will not be modified)

- A configuration file, opa.conf (which lists all the source files of the project and their dependencies; more about this in a moment)

- An example style file, style.css

- The source files, following the classic MVC pattern, divided into three sub-directories: model, view, and controller, for the standard three application layers

The opa-create tool allows for some customization; for instance, it supports multiple

templates that can be set with the --template TEMPLATE_NAME argument. Version 1.1 of Opa

supports three templates:

- mvc-small (default)

- A template for a small project following the MVC pattern, where the src directory contains no subdirectories but only three files: model.opa, view.opa, and controller.opa

- mvc

- An MVC template for bigger projects, where the src directory contains three folders: model, view, and controller, containing respectively data.opa, page.opa, and data.opa

- mvc-wiki

- Which is based on mvc-small but contains an example wiki application, ready to be modified/extended

Every template provides a Makefile that eases the compilation of the project with:

make

and compilation followed by execution with:

make run

Your application should look like Figure 7-1.

Let’s take a quick look at the opa.conf file. In our newly created project, it will look as follows:

birdy.controller:importbirdy.view src/controller.opa birdy.view:importbirdy.modelimportstdlib.themes.bootstrap src/view.opa birdy.model:src/model.opa

Usage of such a configuration file is optional, but it can be quite convenient as it creates a central point listing all project files and packages, as well as dependencies between them. You can consider this as a way to sanitize your project further.

Packages

Packages are the main unit of abstraction in Opa. For Birdy, there are three packages: birdy.controller, birdy.view, and birdy.model. Each section starts with optional import statements, followed by the list of paths to files constituting the given package (one file per project in this example).

Packaging is very important in Opa, as typechecking and compilation are done separately at the package level. Packages are therefore highly reusable bits of code and a major addition to JavaScript, which even lacks modules.

Packaging is also very powerful when combined with abstract data types, which hide types from other packages. We will introduce the latter feature in the next chapter.

Summary

In this chapter you learned more about Opa types; in particular, you learned how to use:

- Variant types

- Pattern matching

- Polymorphic types

- Recursive types

- Recursive functions

- Iterators

Using Opa, you generated an MVC template for your first big project, Birdy, looked inside the opa.conf file, and learned about packages. In the next chapter you will learn how to manage user accounts in Birdy.